The Portrayal of EFL Teachers in Official Discourse: The Perpetuation of Disdain

Keywords:

Teach er education, EFL teach ers, critical discourse analysis, symbolic power, meaning as representation. (en)The Perpetuation of Disdain

La imagen de los profesores de inglés como lengua extranjera

en el discurso oficial: la perpetuación del desdén

Carmen Helena Guerrero

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Colombia

helenaguerreron@gmail.com

This article was received on February 27, 2010, and accepted on July 5, 2010.

The purpose of this article is to offer an interpretation of the images of Colombian English teachers constructed in official discourse, particularly (but not exclusively) in the document "Estándares básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras: inglés. Formar en lenguas extranjeras, el reto". This is part of a larger critical discourse analysis research study whose main data source is the aforementioned document. The analysis was conducted following a Hallidayan "clause as representation" approach combined with Fairclough's methodology for a critical discourse analysis. Three main images were found: teachers are invisible; teachers as clerks; and teachers as technicians/marketers. The conclusions show that official discourse plays into folk concepts of Colombian teachers and feeds into them to validate official unilateral decisions.

Key words: Teacher education, EFL teachers, critical discourse analysis, symbolic power, meaning as representation.

El propósito de este artículo es ofrecer una interpretación sobre las imágenes, que se han construido en el discurso oficial, de los maestros colombianos de inglés. Se examinará particularmente (pero no exclusivamente) el documento "Estándares básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras: inglés. Formar en lenguas extranjeras, el reto". El presente análisis es parte de un estudio de investigación más amplio que usa la metodología de análisis crítico del discurso y cuyos datos primarios son los textos del citado documento. Se realizó el análisis siguiendo el enfoque propuesto por Halliday de "la cláusula como representación" en combinación con la metodología propuesta por Fairclough para hacer análisis crítico del discurso. Se identificaron tres imágenes: los profesores invisibles, los profesores como empleados y los profesores como técnicos/comercializadores. Las conclusiones muestran que los discursos oficiales no solo aprovechan, sino que además alimentan la imagen desfavorable que se tiene en Colombia sobre los maestros, para validar decisiones oficiales unilaterales.

Palabras clave: formación docente, profesores de inglés como lengua extranjera, análisis crítico del discurso, poder simbólico, significado como representación.

Introduction

The main data for this analysis come from the handbook aforementioned and henceforth called "Estándares". The document is part of a series of handbooks published by the Ministry of Education of Colombia within their program Revolución Educativa, one of the leading projects of Álvaro Uribe Vélez, current president of the country. The main objective of this series is to set standards for the core areas of the curriculum which are Spanish, mathematics, and social and natural sciences. Although English is not a core area, it became part of the series because of the implementation of the national bilingualism program (PNB for its initials in Spanish = Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo). The data in "Estándares" were based on the "Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment", a document produced in Europe to establish a set of standards for the diverse languages spoken on that continent, and in order to facilitate student mobility across Europe 1.

As a researcher I share the idea that no text is neutral (Canagarajah, 1999; Fairclough, 1992, 1995, 2001; Heller, 1992; Kress, 1989a; 1989b; Pennycook, 1998; Van Dijk, 1997, 2005; Wodak, 2005); that institutions play a crucial role in the distribution, control, and circulation of discourse (Foucault, 2005; Macdonell, 1986; Mills, 2004), and that textbooks (in this case a handbook) are vehicles used by institutions to direct people's behavior (Kress, 1989a; Stubbs, 1996). This set of beliefs, the fact that the main audience for the "Estándares" is comprised of Colombian English teachers, plus anecdotal data2 about how people perceive EFL. Colombian teachers guided my interest in exploring how official discourses contribute or contest the images held about EFL Colombian teachers.

Texts are dialogic in nature (Mills, 2004); the writer constructs his/her reader, and based on that idea, selects the language to be used in the text (Kress, 1989a). This procedure makes it possible to reconstruct information about the addressee even when he/she is not overtly present in the interaction or in the text. If we hear only one of the interlocutors in a conversation, the linguistic choices made by him/her allow us to construct an idea of who the other interlocutor(s) is/are: age range: children, adolescents, adults; sex: men, women; type of relationship with the speaker: family, friend, stranger, lover; power relation: symmetric, asymmetric, and so on and so forth (Eggins, 1994; Halliday & Hasan, 1985). The "Estándares" has been constructed as a dialogue between the Ministry of Education and Colombian EFL teachers.

Halliday (1994) and Halliday & Matthiessen (2004) consider that three different meanings are present in a clause: message, exchange, and representation. The first one refers to the topic or thematic structure of the clause, what it is about. The second one establishes who is voicing the message; and the third one is how human experience is constructed. To each one of these meanings, Halliday (1994) associates three functions respectively: theme, subject, and actor.

Clause as representation will guide the analysis in this article (although the three meanings occur simultaneously). Halliday (1994) states that reality is made up of processes, and processes consist of three components -the process itself, the participants in the process, and the circumstances associated with the process- saying, "[t]hese components are semantic categories which explain in the most general way how phenomena of the real world are represented as linguistic structures" (p. 109). Here I concentrated on the participants in the process since my interest -as stated above- is to see how teachers, as participants in the National Bilingualism Program (PNB), are represented or constructed in the "Estándares"3.

The Focus of the Study

As stated above, this article is part of a larger research study conducted to analyze how the document "Estándares" constructed three concepts: bilingualism, English, and Colombian English teachers. The "Estándares" themselves constituted the main data source and the research methodology followed Fairclough's model for critical discourse analysis. In this methodology the fine grained linguistic analysis is combined with the intertextual analysis drawn from the macro structures that make up the context in order to offer a sound interpretation of data. In this particular article, I focus on reporting the third part of the larger study, which has to do with the images of Colombian EFL teachers in official discourses.

Findings

The analysis of data shows three main images: The first one is that teachers are invisible because despite the fact that the "Estándares" is addressed to them and they are the ones to carry out the actions to achieve the standards, they are scarcely mentioned in the handbook, their opinions little considered and their knowledge not valued. The second image is teachers as clerks in the sense that they are expected to just follow the orders of a remote authority without questioning, resisting, or contributing; and a third image constructs teachers as technicians who are there to create a marketable product.

Teachers are Invisible

González, Montoya and Sierra (2002) in their seminal article on teacher education in Colombia state that although teacher educators might think they know what teachers need and want as professionals, their voices are very rarely taken into account when designing teacher education programs. The same is true when it comes to educational policies (Smith, 2004); teachers are not consulted about the feasibility, necessity, or content of a new policy, nor are their knowledge and expertise taken into account (Ayala & Álvarez, 2005; Cárdenas, 2009; González, 2007; Sánchez & Obando, 2008; Vargas, Tejada & Colmenares, 2008).

One possible explanation for the exclusion of teachers' voices might have to do with whose knowledge is valued and whose is not, which at the same time might be related to the following three aspects:

1) The influence of positivism in the sense that something is sanctioned as "valid knowledge" if it responds to the characteristics of the scientific method; that is, if it is observable and measurable and comes from a recognized author (Foucault, 2005; Macdonell, 1986). Teaching is a humanistic activity that does not always fit in the scientific method. Sometimes teachers make decisions based on their intuition because they are the ones who have a holistic picture of who the students are and what they need.

2) The value given only to institutionalized forms of capital. Bourdieu (1986) identifies three forms of cultural capital -embodied, objectified, and institutionalized- but it is the latter that enjoys more prestige in our society. It is necessary to have a certification of knowledge given by an institution (which at the same time is a double-edged sword because the knowledge sanctioned as such by an institution responds to what the mainstream or dominant groups regard as "valid knowledge"). As a consequence, teachers' knowledge is not certified (in a lot of cases) because a great deal of their knowledge is constructed in and from their classroom through experience. Fortunately, some Colombian universities, through their masters programs and teachers' development programs have contributed greatly to spread teachers' intellectual production by means of local, regional, and national conferences, and publications as the ones mentioned further below.

3) The widespread concept in Colombia that teachers are less intelligent or less capable than the rest of the professionals in Colombia; two probable reasons for this concept might be first, that to enroll in any teaching program students are required to have merely the minimum score on the ICFES (a state exam) while for many other programs the highest score is required. The second possible reason is that to obtain a bachelor's degree in teaching, students in the past had to attend college for only four years while all other programs required five years (this was modified some years ago and now all programs take five years to complete).

As a consequence of this poor conception of who teachers are and what they are able to do, in most educational planning, teachers are expected to just follow instructions and successfully achieve the goals set by others. The National Bilingualism Program is no exception, and school teachers' voices were not considered when designing it (Cárdenas, 2006; Sánchez & Obando, 2008). Besides their invisibility during the process, school teachers have also been invisible in the document "Estándares" regardless of the crucial role they will play as future implementers of the project.

In order to explain the invisibility of teachers in the "Estándares", I drew from Halliday's (1994) clause as representation and Fairclough's (2003) representations of social events. As stated above, for Halliday, a clause is made up of process, participants and circumstances; also, depending on its grammatical configuration, the semantic interpretation varies. In the same line of thought, Fairclough considers that social events include various elements like forms of activity, persons, social relations, objects, means, times and places, and language. This framework allows the researcher to identify not only what elements are included or excluded but, of those included, which ones get prominence and which ones do not. The following excerpt, which is the opening paragraph in the "Estándares", illustrates one of the instances in which teachers are made invisible in the handbook:

Ser bilingüe es esencial en el mundo globalizado. Por ello, el Ministerio de Educación Nacional, a través del Programa Na cional de Bilingüismo, impulsa políticas educativas para favore cer, no solo el desarrollo de la lengua materna y de las diversas lenguas indígenas, sino también para fomentar el aprendiza je de lenguas extranjeras como es el caso del idioma inglés. ("Estándares", p. 5)

Being bilingual is essential in the globalized world. There fore, the Ministry of Education, through the National Bilin gualism Program, promotes educational policies to favor not only the development of the mother tongue and the various indigenous languages, but also to promote the learning of for eign languages as is the case of the English language4.

The text mentions various forms of activities like "impulsa políticas educativas" (thrust forward educational policies), "favorece el desarrollo de la lengua maternal y de las lenguas indígenas" (favor the development of the mother tongue and indigenous languages), and "fomenta el aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras" (foment the learning of foreign languages); there is also information about objectives: the languages to be learned and developed. The means is also present in the "Plan Nacional de Bilingüismo" (National Bilingualism Program). In relation to the persons involved, only the MEN plays a very prominent role, which is indexed by the grammar of the main sentence because it is in active voice. The selection of vocabulary enhances the role of the MEN since words like "impulsa", "fortalece", and "fomenta" have positive connotations.

Excluded from this particular paragraph are students and teachers. The former are mentioned in some other parts of the "Estándares" while the teachers are hardly ever mentioned in the document, which makes sense in their portrayal of teachers because as stated by Bourdieu (2003), "the minimum of communication ...is the precondition for economic production and even for symbolic domination" (p. 45). Making sure teachers are the least mentioned in the document diminishes their opportunities to criticize, opine, question and, all and all, interact with the MEN.

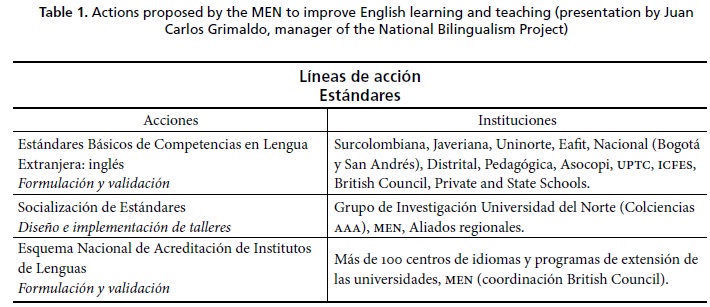

In this excerpt and many others, there is no reference to the role they play in the whole project, which shows MEN's lack of understanding in this sense because teachers are directly responsible for the success or failure of any educational policy (Giroux, 1988; Kumaravadivelu, 2003). By excluding teachers, the social relationship between them and the MEN is obscured in relation to teacher preparation programs. The actions included (mentioned above) do not signal how the government is promoting the development of the mother tongue and indigenous languages; the actions are taken for granted, as if they were actualized in every single context in the country and for every single teacher. Furthermore, the text suggests that Spanish, indigenous languages, and English all receive the same budget and investment, but the reality is that the majority of the resources are being used for the spread of English (De Mejía, 2006; Vélez-Rendón, 2003; see Table 1). The actions of the MEN are focused on supporting only teachers' preparation in English, using models like the TKT developed by the British Council; furthermore, teachers are tested with the Quick Placement Test designed by Oxford University Press (Cely, 2007; González, 2007). Table 1 shows the main actions proposed by the MEN to improve English learning and teaching.

The agency of the MEN is apparent throughout the whole "Estándares" in the sense that it presents itself as the one who possesses knowledge and, as a consequence, it can make decisions. By assuming the whole agency in the decision making, the MEN not only does not acknowledge the voice and opinions of Colombian schoolteachers / scholars / academics / experts, but also gives a high value to the knowledge produced in Europe.

Table 2 serves as an illustration of the disparity of the value given to local knowledge (that produced by Colombian school and university teachers) and foreign knowledge (European). The first excerpt is part of a letter sent by the MEN to invite various university teachers to participate in the project to formulate and validate the standards. While in the letter the MEN praises the achievements produced by local knowledge and acknowledges the important role it plays in the project, later on it decides to choose the Common European Framework in a clear disregard for the work of Colombian academics. In fact, in 1990 a group of Colombian scholars participated in the COFE (Colombian Framework for English) project (Rubiano, Frodden, & Cardona, 2000), and later, in 1999, another group of academics from several public and private Colombian universities wrote the "Lineamientos curriculares para idiomas extranjeros" (Curricular Guidelines for Foreign Languages) (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 1999). Although both projects were sponsored by the MEN, none was considered for adoption in their PNB. The second excerpt (see Table 3) is a paragraph of a letter that was signed by more than thirty Colombian academics sent to the MEN asking why they had adopted the First Certificate to evaluate proficiency while there was a group of Colombian scholars working on the development of a local test.

The practice of devaluing local knowledge is common in Colombia, and a possible interpretation has to do with our condition as a former colony of Spain. After independence, Latin American leaders were strongly influenced by the Enlightenment, which ranked societies from barbaric to civilized (Hall, 1997 as cited in Ruiseco & Slunecko, 2006) so that the new republics could imitate European culture if they wanted to become civilized. During the 1920s, a nationalist movement emerged in Latin America that addressed the fact that although Latin American countries had achieved their independence, it was only political because culturally and ideologically we continued to behave as colonies (Gamio, 1916; Vasconcelos, 1961).

The colonial ideology in which Europe was constructed as the paradigm of what the world should be like (Pennycook, 1998; Ruiseco & Slunecko, 2006) was so pervasive that even today in some fields like education we adopt their models guided by the idea that they know better (Ayala & Álvarez, 2005). The adoption, not only of the CEF but also of the teaching methodologies, the teaching training programs, the materials and the test perpetuates the inequity between local knowledge and the knowledge of the former colonial powers (González, 2007).

Table 4 below shows an excerpt of the letter sent by the MEN at the beginning of the process of the PNB in which they state why they signed an agreement with the BC. As stated by González (2007) "[t]he imposed leading role of the British Council, or of any other foreign academic institution that might have been chosen to guide the policy of bilingual

Colombia, holds back the development of a local teachers are excluded, the relationship between community with enough validity to construct a lan-them and the MEN is apparent. Their categoriguage policy" (p. 313). cal statements signal a vertical and asymmetrical

Teachers, who know their students better than power relationship where teachers are positioned anyone else, do not get a voice to express their opin-as followers whose role is to obey the rules without ions, concerns, and solutions. Despite the fact that questioning them.

Using words in this way paves the road towards the naturalization of discourse (Fairclough, 1995) and with it the road to symbolic power (Bourdieu, 2003). In this case, an institution like the Ministry of Education, given its very nature (official institution), is entitled to exert power explicitly on the education community by means of decrees, laws, agreements, and other regulatory means; nevertheless, it reinforces its actions by the use of symbolic power through the use of discourse because, as stated by Bourdieu (2003), symbolic power leads people to behave according to the interest of the dominant groups without the use of violence. Through its discourse, in which it circulates the message that this is how things should be, the MEN wants to block any type of resistance from teachers; its goal is to create a hegemonic situation in which teachers accept and become part of their own silencing.

Teachers as Clerks

In the few instances in which teachers are included in the "Estándares", they are constructed as "clerks". I borrowed this denomination from Giroux (1988) and the meaning is that teachers are viewed as employees who follow diligently the directions of a distant authority. Teachers are portrayed as passive followers whose willingness to cooperate is taken for granted.

The perception of teachers as clerks has been constructed through time and has been strongly influenced by the ideology that guides teacher development programs. Within the terminology of teacher education, there are two prevailing concepts which are "pre-service teacher education" to refer to the preparation of students who want become teachers; and "in-service teacher education" to refer to the courses taken by teachers to update their knowledge, to learn new techniques, strategies, and the like. González (2003) explains the existence of the second type according to the common belief (by teachers and non teachers alike) that pre-service teaching preparation is insufficient and more preparation is needed in order to become a good teacher. Part of the reason for this belief could be that teacher preparation has been influenced heavily by behavioral and cognitive psychology and that educational theory has been constructed around a discourse and a set of practices that emphasize immediate measurable methodological aspects of learning and, furthermore, that when teachers face their reality and do not comply with these ideals they need they need more "training" (Giroux, 1988).

According to Woodward (1990), teacher education programs could fall into two main attitudes: "teacher training" and "teacher development", which she defines as being fundamentally opposed to each. There are profound ideological differences between these two attitudes in relation to how teachers and teaching are perceived in each one. Although both models focus on the instructional part of teaching, in the former, teachers are seen as mere "deliverers" who need to learn certain skills and recipes to be "efficient". In the latter, teachers are viewed as professionals who are in charge of their own actions and are capable of making their own decisions (González, 2003; Richards, 1996; Woodward, 1990).

González (2008) states that in Colombia, ELT education follows two tendencies which she categorizes as top-down and bottom-up, but which are strongly related to Woodward's taxonomy. The former tendency includes the courses proposed by the British Council like the IELTS and the TKT while the latter tendency includes regional conferences, publisher's sessions, university-schools collaboration, and university-based programs. Within the latter one, González, Cárdenas, Álvarez, Quintero and Viáfara (2009) document the teacher education models developed in Colombia by Colombian academics; these models are characterized by a holistic perspective that combines elements of previous models, but that also looks at the particularities and complexities of the participants in these teacher education programs.

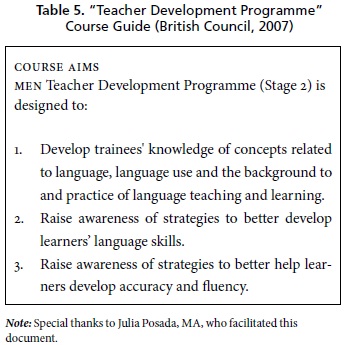

Considering that for this particular project the MEN has designated the British Council (BC) as the coordinating organism for the whole project, it is a natural consequence that the BC models of teacher education, which fall into the characteristics of teacher training, prevail at this moment in Colombia. As a result, teachers in the "Estándares" are constructed as "trainees"; that is, people in need of learning from the experts and not as professionals capable of making sound contributions to the PNB. Consequently, given that they receive limited training useful to perform only certain tasks, they are positioned at the same level as clerks. Table 5 shows the aims of the latest teacher development program proposed by the MEN in which it is clear that the goals are to train teachers from a mere instructional point of view with no interest in promoting teachers' reflection or their exploration of critical issues in teaching. In a course like this one, teachers are equipped with all the necessary recipes to perform their task efficiently with the underlying belief that, in that way, they will be good English teachers.

These teacher training models are not innocent because, as stated by Pennycook (1994), teaching practices are cultural practices linked to the promotion of certain forms of culture and knowledge. As a consequence, a discourse that emphasizes "skills, strategies, trainees, systematic, accuracy, techniques" and the like (as seen in Table 5) is bound to be spread in the same way. This type of course does not encourage or promote the problematization of linguistic practices and the power relationships that exist within them (Bourdieu, 2003; Hornberger & Skilton-Sylvester, 2000) and, therefore, the possibility of an agency to transform unequal social practices enacted through language is denied from the beginning.

The following excerpt is another example of the construction of teachers as clerks. Here the MEN positions itself as the authority that determines what teachers have to do to fulfill the tasks assigned:

108) La tarea de todas las instituciones educativas es velar por que sus planes de estudio y las estrategias que se empleen contemplen, como mínimo, el logro de estos estándares en dichos grupos de grados y ojalá los superen, conforme a las particularidades de sus proyectos educativos institucionales y a sus orientaciones pedagógicas. ("Estándares", p. 11)

The task of all educational institutions is to ensure that their curricula and strategies used include, at the very least, the achievement of these standards in those groups, and hopefully to be exceeded, being in conformity to the particularities of their institutions and their teaching guidelines.

The MEN demands from schools the commitment to "watch over" (velar) their study plans and the strategies used so the standards are achieved. It clarifies, though, that schools should take into account their "Proyectos Educativos Institucionales" (Institutional Educative Project = PEI)5 and their own pedagogical orientation when working towards the achievement of the standards.

The two clauses that give structure to this paragraph are contradictory because the first one is stating a command that schools (teachers included) need to obey and which is based on the standards previously adopted by the MEN. Regardless of schools PEI, they must at least ("como mínimo") achieve those particular standards. This means that the autonomy schools have in the PEI exists only on paper and not in reality.

Another way in which teachers are constructed as clerks but which cannot be identified in independent instances or paragraphs has to do with the tenor (Halliday & Hassan, 1985) of the whole document. As stated above, it is addressed to teachers because they are the people who teach English in the classrooms, but they are hardly mentioned in the "Estándares". Nevertheless, the tenor in which the whole document is written hints at the image that the MEN holds of Colombian teachers. Cárdenas (2009) confirms this when she voices teachers' concerns about the haste with which decisions are made by the MEN.

The concept of "tenor" was developed by Halliday (in Halliday & Hassan, 1985) in relation to the "context of situation" and along with other two concepts: field and mode, as defined by the personal relationships involved. In this particular case, the tenor of the whole text allows the researcher to interpret the type of relationship that exists between the author (MEN) and the addressees (schoolteachers).

From the linguistic choices made by the authors coupled with the topics and the structures in which the text is written, the asymmetrical positioning of the MEN is apparent, where the latter are poorly valued and are not recognized as legitimate contributors in the design and implementation of an educational project. The language used by the authors of the document is, in a way, patronizing and condescending.

The text that more evidently resembles the construction of teachers as clerks is the first part of Chapter 5 of the "Estándares" where the authors explain the structure of the standards. It comprises a set of instructions teachers have to follow; the style in which they are written do not leave room for autonomy, creativity or questioning by the teachers, as can be seen in the following excerpt which is the first paragraph of Chapter 5:

109) En las páginas siguientes se encuentran los cuadros de estándares para la educación básica y Media. Estos están orga nizados en cinco grupos de grados que corresponden, además, al desarrollo progresivo de los niveles de desempeño en inglés. ("Estándares", p. 14)

109) On the following pages are tables of standards for basic and secondary education. These are organized in five groups of grades that match the progressive development of standards of performance in English.

The tenor of this text shows an unequal power relationship between the writer and the audience. Following a Hallidayan analysis, it could be said that the participants in the text are the MEN (as the writer) and teachers (as audience). In the excerpt above we can see that the MEN, by using two indirect statements ("on the following pages..." and "These are organized..."), performs an illocutionary act (Austin, 1962/2004) that underscores teachers' tacit agreement or cooperation principle (Grice, 1975/2004) in doing the task, and also on the asymmetrical power relationship that exists between the two (MEN/teachers) given by their roles in society. By announcing that the standards are to be found on the following pages, the MEN is saying more than that; it is stating that the MEN has established certain standards and teachers have to implement them.

Once again the role of the teachers is relegated to that of fulfilling a clerical job; they are not valued as intellectuals, and their autonomy is not considered. They are conceived of as instruments in the spread of a policy (and with it, of particular Anglo-American ideologies), and servants of a corporate system (the school system) (Canagarajah, 1999; Cárdenas, 2006; Pennycook, 1990; Ricento & Hornberger, 1996). The conclusion is that "the experts do the thinking and teachers are reduced to do the implementing" (Giroux, 1988, p. 124).

For this reason, the adoption of a marketing discourse intends to produce the efficiency of cost-benefit in public schools. As such, schools whose teachers are seen as employees of an economic industry are at the service of productivity; a teachers' task is to "equip" students (who are seen as human capital) with the skills to compete efficiently and competitively outside the school (Apple, 2006). Thinking of teachers as "makers" of marketable products gives rise to the next category: teachers as technicians/marketers.

Teachers as Technicians/Marketers

Within his identification of postmodern culture, Fairclough (1995) includes its characterization as a "promotional" or "consumer" culture. He defines it as the "reconstruction of social life on a market basis" (p. 138) where language serves the purpose of "selling" services, products, ideas, people, and so on. Education has fallen into this category and schools have started to operate as businesses where students are the products, teachers the employees whose task is to make a good product, and the corporations are the customers. To keep the customers happy is the ultimate goal of any business; in the school setting, teachers need to make sure the product (students) fulfills the needs of their customers.

The MEN and the BC have painted the picture quite differently; although they keep the argument of the economic benefit, the difference lies in who will receive the returns from investing in the right sort of linguistic capital (English). The overt argument is that students will receive or enjoy economic benefits in the form of social mobility, better jobs, access to scholarships, and access to knowledge, science, technology and entertainment. But what will most likely happen, particularly with the international economic crisis, is -as projected by Apple (2006)- that in both the contexts of the United States and Colombia, most new jobs will be found in the service sector where high levels of education are not needed and will be characterized by being low-paid, part time, or temporary.

To fulfill the goal of producing students for the labor market, the role of teachers takes a slightly different shade from the previous one (teachers as clerks). They still have to follow orders but there is an emphasis on the quality of the final product as stated by the Minister of Education, Cecilia María Vélez White, on the first page of the "Estándares":

114) El ideal de tener colombianos capaces de comunicarse en inglés con estándares internacionalmente comparables ya no es un sueño, es una realidad y solo podremos llegar a cumplir los propósitos establecidos si contamos con maestras y maestros convencidos y capaces de llevar a los niños y niñas a comunicarse en este idioma. ("Estándares", p. 3)

The ideal of having Colombians able to communicate in English with comparable international standards is no longer a dreambut a reality, and we can only arrive at meeting the stated purposes if we believe teachers are able to teach the children to communicate in this language.

The role of teachers is to "produce" students who can compete in a linguistic market that is highly influenced by the corporate world where an ideal variety (so called "standard") is used and that that will determine the feasibility of employment (see Table 6). The official voice (Ministry) expects total compliance from teachers to achieve this endeavor by saying that the objective of speaking English will be possible if teachers are "convinced and capable".

In this paragraph teachers get prominence that comes with a hint of a negative connotation because it implies submission on the teachers' part. Being "convinced" means that teachers believe and approve the decisions made by the Ministry and will not challenge or resist them; doing the opposite could be seen as sabotage. The underlying thought is that when things go wrong, it is exclusively the teachers' fault because they were not "convinced" or "capable". This is a recurring practice in our societies, to blame teachers for social failure instead of bringing a multilayered analysis to interpret reality. While the outcomes are good, everything else is acknowledged but teachers (Apple, 2006; Wink, 2000).

The case of English teachers is particularly interesting because they are not usually seen as educators responsible for the holistic development of their students who can transform their lives (Kumaravadivelu, 2003) but rather as technicians limited to perform a specific task without much involvement in the broader context of their classroom, school, or community. This perception is strengthened by the assumptions (still in effect in many contexts in Colombia) that (1) teaching English is "neutral" and that (2) the only requirement to teach English is to speak the language.

Therefore, English teachers have no responsibility in the education of their students; that is the task for other teachers; theirs is to teach children to speak the variety of English sanctioned by the MEN and the BC as the legitimate (standard) one, as seen in the following excerpt:

Para ilustrar esta interrelación basta ver como en el caso del aprendizaje del inglés o de cualquier lengua extranjera, el desarrollo de la competencia comunicativa solo es posible cuando se desarrollan, en forma paralela, otros saberes que el estudiante adquiere en las distintas áreas del currículo y que le dan contenido a sus intervenciones... ("Estándares", p. 13)

To illustrate this inter-relationship, it is enough to see, as in thecase of learning English or any foreign language, that the development of communicative competence is only possible when other contents of the curriculum are developed (by the student) in parallel, which give substance to their speaking...

According to this excerpt, the English teacher teaches only the language; that is, the "structures" to be used which get "content" from the other areas of the curriculum. The "neutrality" of the language -discussed in the previous chapter- permeates its teaching so that if language is a collection of rules, teaching it means practicing those rules -the vocabulary, the combinations, the pronunciation and so on and so forth. Since mastering the structural part of the language is the only one that has validity and relevance for the MEN in its PNB and some teachers lack such mastery (due to historical reasons and not because they are ignorant), the MEN conceives teachers from a deficit perspective who need training in basic skills and privileges the British Council models for teacher education.

From this perspective, the English teachers' role is very mechanical (Guerrero & Quintero, 2005), and they are not at all thought of as intellectuals (Giroux, 1988) who can tackle critical issues within their classes and challenge the status quo. Colombian English teachers have proved them wrong and have started to see their profession as much more than teaching empty structures (González, 2007; Vargas et al., 2008), and the evidence can be found in the amount of scholarly presentations and research articles school and university teachers of English alike have published during the last ten or more years in the three main teachers' journals: Íkala, PROFILE, Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, HOW, and Lenguaje. Their intellectual production shows that their understanding of the profession goes beyond grammar; and their application of theories serves not only to inform their teaching practices but also to explore who Colombian students are and what they need.

Conclusions

In Colombia there is a generalized poor conception of teachers. In everyday conversations teachers are portrayed from lazy and unintelligent to problematic and mediocre. Some parents would stand against their children's desire to become teachers because teaching is not a profitable and distinguished profession. This conception has a direct relationship to the level of education chosen by the teacher: being a preschool teacher receives the lowest value while being a university teacher gets a little bit more respect.

Few Colombians acknowledge the real value of teachers: the constant devotion most teachers give to their students; the sacrifices teachers who work in rural or underprivileged areas make every day to keep their students at school; the skills teachers develop to make the most of the few resources they have; the effort they make to advance in their education; and the magic they perform to make a decent living out of the low salary they get.

Unfortunately, these teachers, the ones who go to work every day and help to build the nation, are invisible for the Ministry of Education. So invisible that their voices were not heard when deciding this educational policy or other educational policies. Although there is a list of schools and teachers' names included in the last pages of the "Estándares" as contributors, reviewers, and evaluators of the handbook, it is apparent, as shown in the analysis of the data, that the discourse presented there is not polyphonic; rather, it is a uniform discourse associated with the ideologies of the British Council and its policy of the spread of English worldwide based on the idea that English is the key to success and privilege.

Teachers are valued only because of their language skills in English, so it is not surprising that the very essence of teachers is undervalued. The mark of their suitability is their command of the four language skills; whether or not they are suitable teachers does not matter because with a "training course" they will be ready to follow instructions and be efficient instructors.

The MEN assumes teachers as just instructors (a concept inherited from British teaching models); that is, trainees with limited, superficial and technical knowledge while the MEN sees itself as a body of "specialists" coached by the British Council "experts". Teachers are detached from all the complexities of the profession which is not limited to technical tips or content knowledge, but includes a wide range of aptitudes learned only by teaching. By seeing teachers as technicians the MEN has no reason to accept them as valid interlocutors whose knowledge can contribute to enrich the teaching-learning process.

Summing up, the conjugation of the already generalized poor concept of teachers plus the ideology of the colonized produces, as a result, an asymmetrical power/knowledge relationship. As such, teachers do not have much to offer because their discourse goes in one direction and the MEN's in a different one. Although there might be points in which both (teachers and MEN) coincide, as long as the MEN insists on undervaluing Colombian teachers and academics to acknowledge and hear only what foreigners have to say about how to educate our students, and in the long run, what direction the country should take, this project is bound to fail.

1 See Ayala & Álvarez (2005), Cárdenas (2006), Sánchez & Obando (2008), Vargas, Tejada, & Colmenares (2008), for more information about the mismatches between the "Estándares" and the cefr.

2 These data were gathered from introspection, informal talks with community members, people's participation in blogs, online newspapers, etc.

3 As stated above, the "Estándares" were produced by the Ministry of Education within their National Bilingualism Program, whose objective is to make the teaching of English mandatory at the national level- in all public schools from elementary to secondary.

4 All translations were done by the author.

5 The pei was created by the men as a way to actualize the autonomy of Colombian schools particularly in relation to establishing educational goals that responded to the situated needs of each school community (Decreto 1860 de 1994).

References

Apple, M. (2006). Educating the "right" way. New York: Routledge.

Austin, J. L. (1962/2004). How to do things with words. In A. Jaworsky & N. Coupland (Eds.), The discourse reader (pp. 61-75). New York: Routledge.

Ayala, J., & Álvarez, J. A. (2005). A perspective of the implications of the common European framework implementation in the Colombian socio-cultural context. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 7, 7-26.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241-258). New York: Greenwood Press.

Bourdieu, P. (2003). Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Canagarajah, S. (1999). Resisting linguistic imperialism in English teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cárdenas, M. L. (2006). Bilingual Colombia: Are we ready for it? What is needed? Paper presented at the 19th Annual EA Education Conference. Retrieved August 20, 2010, from: http://www.elicos.edu.au/index.cgi?E=hcatfuncs&PT=sl&X=getdoc&Lev1=pub_c07_07&Lev2=c06_carde.

Cárdenas, M. L. (2009). A propósito de la autonomía y las políticas de Colombia bilingüe. In M. L. Cárdenas (Ed.), Investigación en el aula en L1 y L2. Estudios, experiencias y reflexiones (pp. 23- 30). Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Cely, R. M. (2007). Programa nacional de bilingüismo: En búsqueda de la calidad en educación. Revista Internacional Magisterio, 25, 20-23.

Concejo de Bogotá. (2006). Proyecto de Acuerdo número 232 de 2006. Retrieved August 20, 2010, from: http://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=20445.

De Mejía, A. M. (2006). Bilingual education in Colombia: Towards a recognition of languages, cultures, and identities. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 8, 152-168.

Eggins, S. (1994). An introduction to systemic functional linguistics. London: Pinter Publishers London.

Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis. The critical study of language. Essex: Longman.

Fairclough, N. (2001). Language and power (2nd ed.). London: Longman.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse. Textual analysis for social research. New York: Routledge.

Foucault, M. (2005). El orden del discurso. (3.era ed.). (Alberto González Troyano, Trad.). Barcelona: Fábula Tusquets Editores.

Gamio, M. (1916). Forjando patria. México, D.F.: Porrúa Hermanos.

Guerrero, C. H., & Quintero, A. (2005). Teachers as mediators in undergraduate students' literacy practices: Two pedagogical experiences. How Journal, 11, 45-54.

Giroux, H. (1988). Teachers as intellectuals. Massachussets: Bergin and Garving Publishers.

González, A. (2003). Who is educating EFL teachers: A qualitative study of in-service in Colombia. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 7(13), 29-50.

González, A. (2007). Professional development of EFL teachers in Colombia: Between colonial and local practices. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 12(18), 309-332.

González, A. (2008). Tendencies in professional development for EFL teachers in Colombia: A critical appraisal. Paper presented at the 5.º Encuentro de Universidades Formadoras de Licenciados en Idiomas.

González, A., Cárdenas, M. L., Álvarez, J., Quintero, A., & Viáfara, J. (2009). Estudio diagnóstico. Oferta de programas de desarrollo profesional para los docentes de inglés en ejercicio en Colombia. Bogotá: Asocopi / MEN.

González, A., Montoya, C., & Sierra, N. (2002). What do EFL teachers seek in professional development programs? Voices from teachers. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 8(14), 153-172.

Grice, H. P. (1975/2004). Logic and conversation. In A. Jaworsky & N. Coupland (Eds.), The discourse reader (pp. 76-88). New York: Routledge.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1994). An introduction to functional grammar (2nd ed.). New York: Edward Arnold.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Hasan, R. (1985). Language, context, and text: Aspects of language in a social-semiotic perspective. Victoria: Deakin University.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar (3rd ed.). New York: Edward Arnold.

Heller, M. (1992). The politics of codeswitching and language choice. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 13, 123-142.

Hornberger, N., & Skilton-Sylvester, E. (2000). Revisiting the continua of biliteracy: International and critical perspectives. Language and Education: An international Journal, 14(2), 96-122.

Kress, G. (1989a). Linguistic processes in sociocultural practices. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kress, G. (1989b). History and language: Towards a social account of linguistic change. Journal of Pragmatics, 13, 445-466.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2003). Beyond methods. Macrostrategies for language teaching. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

Macdonell, D. (1986). Theories of discourse. An introduction. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Mills, S. (2004). Discourse. The new critical idiom. New York: Routledge.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN]. 1994. Decreto 1860 de 1994. Retrieved August 20, 2010, from:http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/articles172061_archivo_pdf_decreto1860_94.pdf

Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN]. (1999). Lineamientos curriculares para idiomas extranjeros. Lineamientos curriculares. Áreas obligatorias y fundamentales. Bogotá: MEN.

Pennycook, A. (1990). Critical pedagogy and second language education. System, 18(3), 301-314.

Pennycook, A. (1994). The cultural politics of English as an international language. London: Longman.

Pennycook, A. (1998). English and the discourses of colonialism. New York: Routledge.

Ricento, T., & Hornberger, N. (1996). Unpeeling the onion: Language planning and policy and the ELT professional. TESOL Quarterly, 30(3), 410-427.

Richards, J. (1996). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rubiano, C., Frodden, C., & Cardona, G. (2000). The impact of the Colombian framework for English (COFE) project: An insider's perspective. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 5(9-10), 38-43.

Ruiseco, G., & Slunecko, T. (2006). The role of mythical European heritage in the construction of Colombian national identity. Journal of Language and Politics, 5(3), 359-384.

Sánchez Solarte, A., & Obando Guerrero, G. (2008). Is Colombia ready for bilingualism? PROFILE, Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 9, 181-195.

Smith, M. L. (2004). Political spectacle. And the fate of American schools. New York: Routledge-Falmer.

Stubbs, M. (1996). Text and corpus analysis. Oxford: Black-well Publishers.

Van Dijk, T. (1997). The study of discourse. In T. van Dijk (Ed.), Discourse as structure and process (pp. 1-34). London, Thousand Oaks, & New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Van Dijk, T. (2005). Critical Discourse Analysis. In D. Schiffrin, D. Tannen & H. Hamilton (Eds.), The Handbook of Discourse Analysis (pp. 352-371). Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Vargas, A., Tejada, H., & Colmenares, S. (2008). Estándares básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras (inglés): una mirada crítica. Lenguaje, 36(1), 241-275.

Vasconcelos, J. (1961). La raza cósmica. Misión de la raza iberoamericana. México: Aguilar.

Vélez-Rendón, G. (2003). English in Colombia: A sociolinguistic profile. World Englishes, 22(2), 185-198.

Wink, J. (2000). Critical pedagogy: Notes from the real world. Second edition. New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Wodak, R. (2005). What CDA is about-a summary of its history, important concepts and its developments. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis (pp. 1-13). London: SAGE Publications.

Woodward, T. (1990). Models and metaphors in language teacher training. Loop input and other strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

About the Author

Carmen Helena Guerrero Nieto, Ph.D and MA in Second Language Acquisition and Teaching, The University of Arizona. She also holds an MA in Applied Linguistics to the Teaching of English as a Foreign Language, Universidad Distrital. She is an associate professor at Universidad Distrital. Her research interests are critical discourse analysis, critical pedagogy, teacher education, and educational policies.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions during the process of publishing this article. Any mistakes are exclusively my own.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.