DOSSIER:AMÉRICA LATINA: RETOS Y DINÁMICAS

INSTITUTIONAL CHALLENGES AND OBSTACLES FOR THE ECONOMIC INTEGRATION: SOUTH KOREA - LATIN AMERICA

RETOS INSTITUCIONALES Y OBSTÁCULOS PARA LA INTEGRACIÓN ECONÓMICA: COREA DEL SUR - AMÉRICA LATINA

Sebastián Acosta Zapata1; Luciana Manfredi2

1Sociologist and Political Scientist at Icesi University in Cali, Colombia. E-mail: saz0913@hotmail.com

2Assistant Professor at Icesi University in Cali, Colombia. PhD. in Management at Tulane University, New Orleans, Luisiana, United States. E-mail: lcmanfredi@icesi.edu.co, lmanfre@tulane.edu

SUMMARY

This study aims to analyze institutionalization from the perspective of negotiation processes that foster the economic integration agreement that have served Colombia, South Korea and Mercosur as they integrate economically with other regions, considering bilateral negotiations or bloc negotiations. The present research is based in two main theories: new-institutionalism and constructivism, that serve as foundation to explain the main research question: How does the level of institutionalization impact the strategies of negotiation and design of agreements? Finally, is it better to negotiate bilaterally or as a bloc? Therefore, this paper accounts with two kinds of studies- a qualitative and a quantitative one-.

Key words: institutions, bilateral negotiations, bloc negotiations, Free Trade Agreement, interests, identities.

RESUMEN

Este estudio tiene como objetivo analizar la institucionalización, desde la perspectiva de los procesos de negociación, que fomentaron el acuerdo de integración económica entre Colombia, Corea del Sur y Mercosur, teniendo en cuenta las negociaciones bilaterales o negociaciones de bloque. La presente investigación se basa en dos teorías principales: el neoinstitucionalismo y el constructivismo, las cuales sirven para explicar la cuestión principal de la investigación: ¿Cómo el nivel de institucionalización impacta en las estrategias de negociación y diseño de los acuerdos? y ¿es mejor negociar de forma bilateral o en bloque? En ese sentido, este trabajo presenta dos tipos de estudios -uno cualitativo y otro cuantitativo-.

Palabras clave: instituciones, negociaciones bilaterales, negociaciones en bloque, Tratado de Libre Comercio, intereses, identidades.

INTRODUCTION

The relations between South Korea and Latin America go back to the ‘60s. Signed by geogra- phic distance and mutual ignorance, those were limited to the socio-cultural field. Nevertheless, in the last decades, the Latin American region seems to have acquired a high-priority role in South Korea’s foreign policies: signature of the FTA with Chile (2004), with Perú (2010), with Colombia (2012) and FTA negotiations with México.The achievement of the South Korea government in terms of bilateral negotiations in the re- gion is quite significant (with three States and one bloc out of twenty-four processes of negotiation begun). However, if we compare those goals with the accomplishment with MERCOSUR, the gap is obvious because the negotiations processes are different between State-State or economic bloc-State.

The present research aims to solve an interesting question in the Latin American context, whe- re political and economic blocs and agreements have developed since the last mid-century. Even though these agreements among countries in Latin America, such as CAN (Andean Community of Nations) and MERCOSUR (Common Market of the South), appear to be very well consolida- ted, and have been very beneficial for countries, giving each of them more power in terms of bloc negotiations. On the other hand, most countries in these blocs are not necessarily complementary, and more important, each of them have different individual interests and goals, in terms of their position in the geopolitical arena, in most of the cases, when negotiating in bloc, negotiations are very slow, and hampered by individual national interests.

According the previous stated ideas, the research questions appear to be related to the influence of institutionalization on economic integration and trade development. And to seek the new eco- nomic perspective and identities that have recently been built. Specifically, how does the level of institutionalization impact in the strategies of negotiation and design of agreements? Finally, is it better to negotiate individually or as a bloc? Related to the last question, the aim of this paper is to understand how a bloc can be both beneficial and harmful when negotiating with a third country. Thus, is it better to develop a bilateral negotiation process or to negotiate through an institutio- nalized regional bloc?

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The role of institutions from the New Institutionalist perspective

New-institutional theorists emphasize the importance of normative frameworks and rules in guiding, constraining and empowering behavior (Lynall et al., 2003). Furthermore, from the new- institutional perspective, institutions are defined as “the rules of the game in a society or, more formally, are the human devised constraints that shape human interaction. In consequence, they structure incentives in human exchange, whether political, social or economic. Institutional change shapes the way societies involve through time and hence is the key to understanding historical change.”(North, 1990). In the present research the focus is put on political rules of the game. In addition, institutions contribute to preserve roles, rights and obligations over time. Institutions serve to constrain and guide human behavior. Besides, North (1990) contends that any theory on institutions must be based in human behaviors since all institutions are created and changed by humans. Institutional enforcement and institutionalizations requires formal rules, and North elucidates on the small percentage of human interaction that is governed by formal rules. This means, values and norms, and everything that constitutes informal institutions over time become institutionalized and they appeared to be legitimated.

North (1990) further states that the combination of formal and informal rules that define the institution and provide the basis for continual changes occurring within every institution. This theoretical perspective is presented by North (1990) in terms of institutional change. When defi- ning institutions as constraints, he states that “informal constraints that are culturally derived will not change immediately in reaction to changes in the formal rules” which creates a situation of tension between altered formal rules and persisting informal constraints (North, 1990).

The importance of the States relations in Constructivism

Alexander Wendt (1992) proposes constructivism as a social theory of International Relations, and takes Sociology´s mains concepts to analyze cases of relations between politics agents which are actors that impact and influence the international arena, but are not States, namely, Intergovern- mental Organization as Mercosur and Non-Governmental Organization as Greenpeace. Wendt’s aims was to “make an encompassing study of international structure, and how these is formed by “intersub- jective knowledge”, that gives as result a set of constitutive rules from system from which, actors relate them.”

Constructivism makes a significant wager for concepts such as identity, intersubjective knowled- ge and perceptions, all of them on international scenario. These ideas take shape in accentuating relations between States from practice and political trends in a specific moment. It is necessary that States –or political units- make practices to build an image that is accepted by other political entities. Once these relations are established, structured and institutionalized constructed create a set of rules and ideas that can change relatively frequently, but not representative of uncertainty in the international system.

To have more consistency in this theory presentation, Wendt (1992) proposes that identities and interests are established for a time conform a structure called Institution. This structure builds rules and norms that acquire value in intersubjective knowledge and actors´ acceptation. The cognitive process that constitutes institutions cannot surge away ideas and perceptions that actors have on their environment. The whole of this process knowledge is shared by actors that frame a reliable reality.

This theory aims also to build of intersubjetive knowledge of social actors´ identities; likewise as constitutive element from collective awareness institutions emerge and acquire an independent existence that sometimes goes against the interests of the actors themselves.

Constructivism also proposes a methodology for taking into account when analyzing the rela- tionships that starts from intersubjective knowledge. Thus, it “may give us a clue on how Sovereign States´ institutions reproduce through social interactions, but not before it reveals to us why in this structure identity and interest emerge. There two conditions that would seem necessaries for this occur: (1) interaction´s density and regularity should be sufficiently high and (2) actors may be unsatisfied with previously existing forms of identity and interaction” (Wendt, 1992).

New-institutionalism as constructivism prioritizes concepts of “institutionalization” and “institution” inside of their theoretical components. Thus, North (1990) stated that institutions are a set of rules of the game in a society; and Wendt (1992), on the other hand, says that institutions are a set of identities and interests relatively stables that are constructed from of internalization process of these rules that going solids in knowledge actors share.

CASE STUDY: CHALLENGES AND OBSTACLES TO THE ECONOMIC INTEGRATION

An analysis of the propositions from the quantitative data

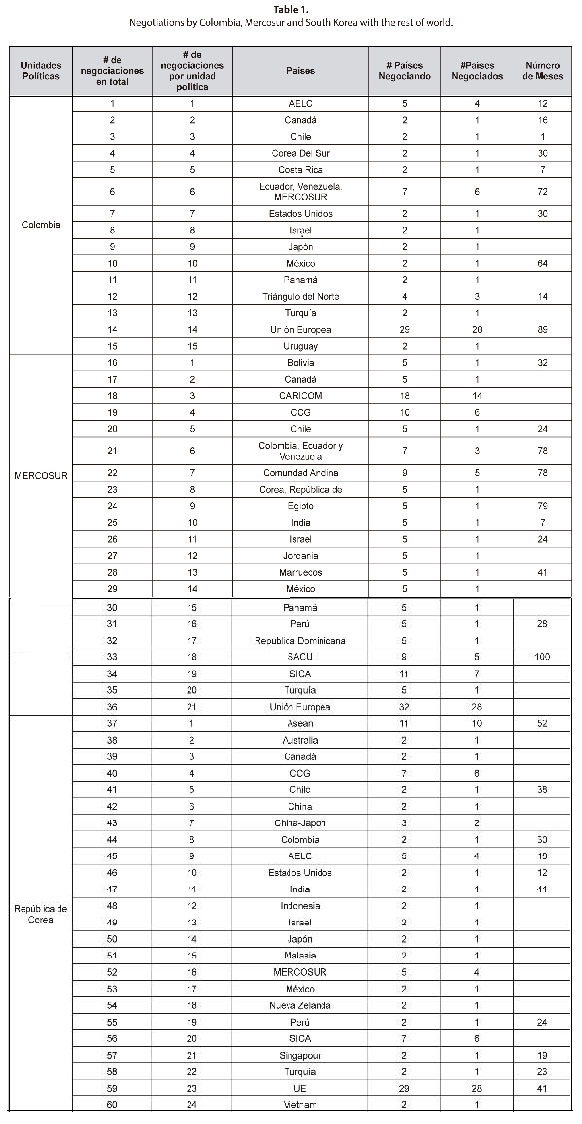

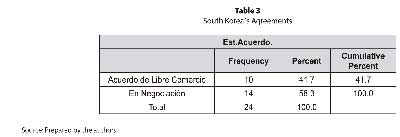

The quantitative study was conducted with data from the Foreign Trade Information System of Organization of American States, the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economy of the studied States, and the World Development Indicators 2013 of the World Bank. Consistently, a database is offered, complete and intergovernmental, that makes possible the consolidation of a research in a mixed method that involves the descriptive conception of the qualitative issue and the numerical indicators of the quantitative issue to do an integral investigation. The data is distributed in this way: 15 negotiation processes for Colombia, 21 for Mercosur, and 24 for South Korea.

Proposition 1: Bilateral negotiations contribute to achieve a successful agreement

Institutionalization of the negotiation processes changes in accordance to the number of coun- tries that are immersed in this process. Therefore, the analyzed data are shown below.

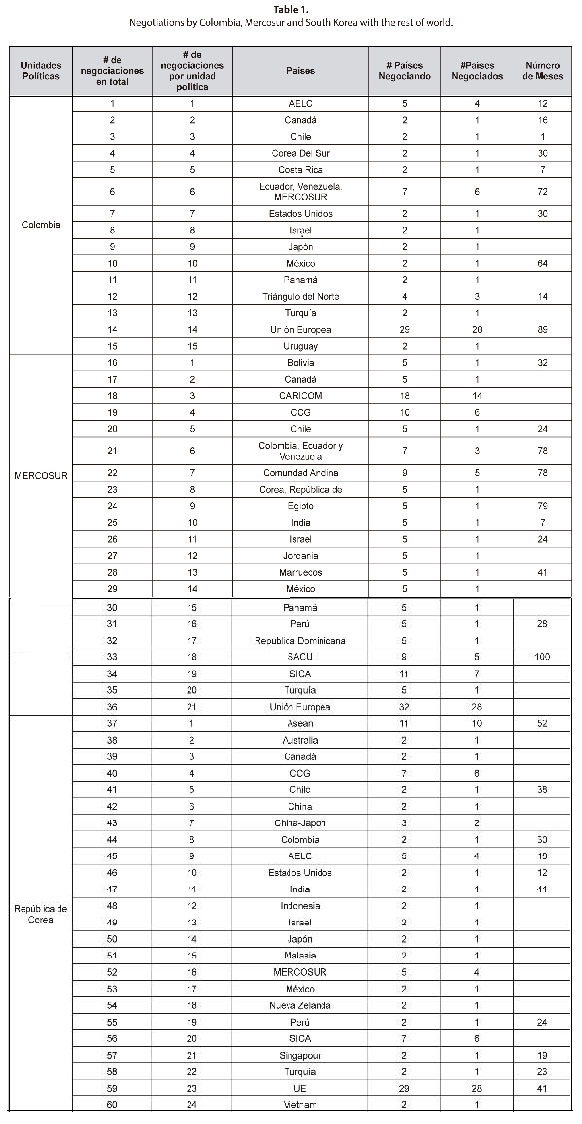

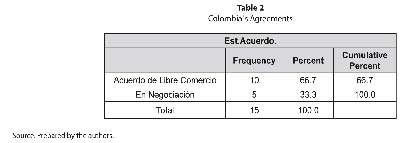

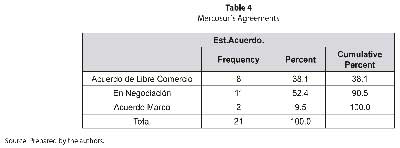

According to the data, Colombia achieved 66,3% of the negotiation processes where it was present, that is to say, 10. Of these latter, 6, namely, 40% got them to another country in a bila- teral negotiation. Meanwhile South Korea, of the 24 negotiation processes that have transpired, has managed to complete successfully 10. This means, 41,7%; of these percentage the 29,1%, has finished satisfactorily within a bilateral process.

For Colombia and South Korea, the bilateral negotiation processes that finished in an agreement, represent more than half of their successful agreements, with 6 of 10 for Colombia, and 7 of 10 for South Korea. This shows that institutionalization of the negotiation process between two States is more susceptible to get a successful agreement because Colombia only has signed 4 agreement with economic bloc and South Korea, 3.

South Korea´s Agreements

Mercosur´s Agreements

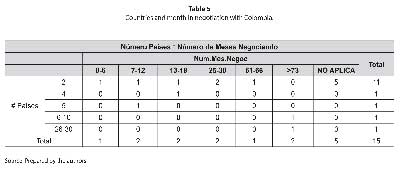

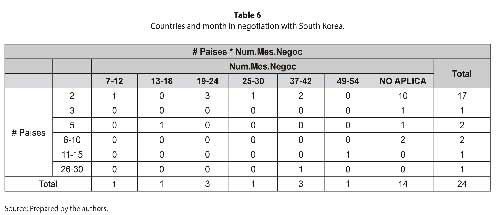

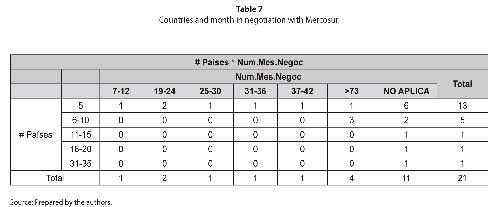

Proposition 2: Bloc negotiations impact the negotiation process and the time required to achieve an agreement

Mercosur had achieved 10 successful agreements of the 21 negotiation processes that have star- ted, and of those, 7 had signed with a third country, the other three with economic blocs. However, institutionalization of agreement is achieved in more time, wearing processes and expands the institution- free trade agreement- that it wishes to build. In the other two studies cases, Colombia has managed to complete its negotiation processes successfully in 34 month average, and South Korea, in 30. Meanwhile MERCOSUR has been delayed 49 months as an average of all successful agreements.

The rules of the game that pretended to construct and institutionalization to be achieved dilate by nature of the negotiation in bloc. The binding normative of the South- American bloc make accurate four countries collectively to negotiate treaties that are accepted. Additionally inside a bloc there must be respect for the individuals interests, for example the act “MERCOSUR/CCM/No 04/07” in which Uruguay expressed intentions to postpone the meeting in Montevideo just because they were presenting, at the time, an internal debate on the situation around customs and trade.

Countries and month in negotiation with Colombia.

Countries and month in negotiation with South Korea.

Countries and month in negotiation with Mercosur.

Proposition 3: When negotiating with a third part, institutionalization of a bloc is the main obstacle to achieve the agreement

Mercosur is constituted with the Treatment of Asunción in 1991. In 1994 it consolidated the Protocol of Ouro Preto in which it defined institutional structure of the bloc and created six mains organs for its operation. Also in 1994 negotiated Free Trade Agreement with third countries (Chile and Bolivia). And four year later agreed the Ushuaia Protocol.

The 9 institutive Protocols make the institutional framework of the bloc and demonstrate formal and juridical behavior that search to establish rules of the game, in present case for consolidation and integration of a countries group. In formals terms the bloc is institutionalized and protocols as a solution of disputes to Mercosur´ s, compromise with Democracy and creation of the Mercosur´s Parliament give an example of this.

Institutional framework of bloc in these cases does not represent an obstacle when negotiated with a third country. Because Mercosur has established negotiation processes with 14 countries of individuals way, of the 7 has been successful agreement. Its means that 70% of the treatment achieved has made with a third country. At least in this specific case, bloc´s institutional framework does not seem so obstruct or impede a successful culmination of the negotiation process.

Proposition 4: The projection of a State in the international arena has positively correlated with the number of agreements achieved

Colombia, South Korea, and Mercosur have the same number of agreement achieved; never- theless their difference resides in negotiation processes that have started. Therefore, not with the same relative weight these 10 agreements achieved for each one. This is because Colombia has successfully concluded 10 of out 15; South Korea 10 of out 24; and Mercosur 10 of out 21.

To measure the international projection of the States studied in this case is taken “The Global Competitiveness Report. 2012-2013” that is a study of sustainable competitiveness of 144 States. This report to pose that sustainable competitiveness “reflects the search of a development model that balances the economic prosperity, environmental stewardship and social sustainability” (GCR, 2013).

According to the data, it cannot so clearly establish a correlation between sustainable and in- ternationally competitive, and the number of agreements reached, because the cases studied did not show a correlation that was indisputable.

For the case of South Korea, yes there a correlation, because is the country that has more negotia- tion processes begun and is which better positioned between States studied. Nonetheless, it is not so clear to Colombia and Mercosur. Colombia has the least negotiation processes having started -15- and is third among studied countries; meanwhile that bloc that has begun 21 is located of 5 among units studied. If the proportion was correlated, Colombia would be down to Mercosur because it just has had 15 negotiation processes, and this last one 21. Therefore, this proposition is not, in part, true.

Proposition 5: The generation of a bloc identity is difficult when the interests of each State differ

Mercosur is positioned like fifth global economy that is attractive for holding commercial rela- tions. However, inside of the Customs Union each State gets his own interest. In this first phase, particulars interests of each State to safeguard the main economy internal sector are make present. Thus, meanwhile agrarian sector for Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay not represents larger shares

to national GDP, to Paraguay represents 50% of his economy, and counted except agricultural products like sugar to Brazil and the bovines meat to Argentina and Uruguay, this country have more agricultural compromises when signing a trade agreement is about.

Regarding the participation of each Member States of Mercosur GDP, Brazil provides 77% of global participation, and given the laws binding that infers a Customs Union, is manifested by Bra- zilian industrial sectors this country’s position within Mercosur and the global economy, represent a “tether” for Brazilian economic growth1. Moreover, Uruguay and Paraguay have a low participation on bloc´s GDP, leading to high economic deficiencies for the two largest economies in Mercosur, and in opposition to the economic, political and expresses equality raises the four Member States.

Politically, institutional framework raises the question that each Member State would be president for a determinate period and the process that there are carried to make decisions must be fully democratic2, therefore, political issues, all formally presented as equal.

This dissonance between the economic and political, causes that bloc´s identity as set is not achieved because each state has them own interests. Wendt (1992) poses that the “identity is the set of expectative and interpretation relatively stable and accord with his paper”, therefore, Mercosur has not achieved a construct as a solid and stable identity that projects to the international arena, despite attempts to consolidate a coherent and harmonious Customs Union, there remain differences between each of the Member States because their unique importance sectors in the domestic economies.

An exploratory approach to economic integration obstacles: MERCOSUR – South Korea

On 26 of March of 1991, the Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay signed the Treaty of Asuncion in order to create the MERCOSUR (Common Market of the South). The fundamental objective of the Treaty was the integration of those four States through the free circulation of goods, productive services and factors, establishing a common external tariff and the adoption of a common commercial policy, the coordination of macroeconomic and sectorial policies and the harmonization of legislations in the pertinent areas. Moreover, in the Presidents’ Summit of Ouro Preto, Decem- ber 1994, was approved an Additional Protocol to the Treaty of Asuncion, the Protocol of Ouro Preto, with the aim of establishing the institutional structure of the MERCOSUR and providing an international legal personality. This Protocol put end to a period of transition and, as a result, were adopted instruments to common commercial policies typical to the Customs Union. To the date, the efforts and profits reached in the matter of integration have been numerous, having obtained the adhesion of five countries like Associate States: Bolivia, Chile, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia.

On another hand, in South Korea, Kim Won Ho point out that previous experiences of negotiation between MERCOSU-USA and MERCOSUR-UE reflects the potential difficulties for South Korea due to its inter-industrial trade relation North-South based on South Korea exportation of electronic, electrical goods of manufacture, machineries and chemical products in exchange of primary goods such as mining products, agricultural, steel and minerals3. Which are the main obstacles that truncate the negotiations of FTA?

First, the main problem is the incompatible duties system. South Korea like MERCOSUR imposes high tariffs to certain items making difficult possible trade agreements. South Korea burdens with high tariffs the agricultural goods whereas MERCOSUR does on automobiles and textile industry. Further- more, in case of carrying out the FTA would be necessary to consider previously the sensitive areas. That study is also corroborated by the Korean Agency of Trade Promotion and Investment (KOTRA) survey.

Finally, we can conclude that to manage to conciliate commercial interests in the framework of a FTA will require arduous negotiations. At the time of finalizing the present research, there have been not clear commitments to reach the signature of an FTA. Although Uruguay and Paraguay are the countries that have expressed more interest in consolidating the FTA with South Korea, the governments of Argentina and Brazil have been cautious: Brazil worries about the possible negative impact on its domestic economy and Argentina vacillates on its international trade strategy with the region. Thus, there are several sceneries that we can project. Nevertheless, it is difficult to state that without Brazilian initiatives the FTA’s negotiations would get priority on MERCOSUR agenda. In this sense, we attempt to assert that it is in the hands of MERCOSUR’s great powers to reactivate this project. For Uruguay and Paraguay clearly depends on them.

COLOMBIA-SOUTH KOREA

The Andean Community of Nations -CAN- is the association of four countries in South America

-Colombia, Bolivia, Perú and Ecuador- that decided to associate in order to achieve an accelerated, equilibrated and autonomous developmental process. The main goal is to achieve full integration, to contribute to human sustainability and equity, respect for diversity and asymmetries. It has been functioning since 1969, but not in a perfect way. Since 2006, Venezuela, one of the state members, decided to leave the community due to ideological and political divergences between Venezuela´s President, Hugo Chaves and Colombia´s ex -President, Álvaro Uribe.

Since Venezuela´s departure, the CAN has faced several difficulties. The bloc appears to be in an unavoidable process of disintegration and one of its main consequences is the individual strategy of each one of the states conforms the community to negotiate with thirds actors other economic and integration agreements.

Since South Korea and Chile signed their commerce agreement, other Latin American countries, saw in South Korea a possibility of increasing their economic integration through international commerce, taking the advantage of having Pacific Coast. This is the case of both Andean countries: Peru and Colombia. Specifically, in the case of Colombia there were several reasons for looking to South Korea. First of all, Colombia has been facing a need to broad its commercial relationships, deepen the external relationships with the Pacific and Asian countries, which are projected for the year 2040 to represent the 66% world GNP, by reducing commerce barriers.

Second, Colombia has been facing a need of diversification of its exports destinations. At the moment, only 5% of Colombia´s exports head to Pacific Asia (while for Chile they represent a 34% and for Peru a 22%). After Venezuela (second destination of Colombian exports) left the CAN, due to divergences between Venezuela´s President, Hugo Chavez and Colombia´s ex-President, Álvaro Uribe, Colombia began to look forward to diversify its exports destinations. Third, Colombia has been searching for an increase of the direct foreign investment (DFI), given that the DFI received from the region represents 0.7%, while for Chile it represents 8% and for Brazil 5.6%. Fourth, Colombia has been facing the need of product diversification, as its exports of other products di- fferent from commodities represent a very low income for the country.

Fifth, Colombia has been facing a need of improving the productive conditions and infras- tructure of the country, through having more access to raw materials, technologies, and capital goods. Finally, it has been mandatory for Colombia to reduce the barriers to services commerce.4 For these reasons, among other (such as their cooperation history, being Colombia the only Latin America country that contributed with troops to South Korea during the Korean War), Colom- bia decided to look toward the Pacific, specifically, South Korea. Therefore, in November 2008 Colombia and South Korea agreed on the importance of a free trade agreement. In 2009 each country began with the feasibility studies, which led to the first negotiation round in Seoul. Se- veral rounds were accomplished (a total of 4 negotiation rounds and 3 negotiation mini rounds), where the main issues discussed have been: access to markets, inversion, services, and origin rules.

GENERAL CONCLUSIONS

The first one conclusion indicates how the Intergovernmental Organization affects to the ne- gotiation processes. The second one, resulting from this research shows a brief overview of the analyses of the propositions. And the last one, we analyze the level of institutionalization of relations between political units making a complex analyzes involving the mix method.

The present research contributes to the study of comparative politics when includes the role of relevant institutions in Latin America, and their regional integration negotiation processes with third countries.

The intergovernmental institutions are the prism through which international relations can be analyzed. With the present analysis it can be concluded that intergovernmental institutions are changing the way the states relate among them and with third states in the international system.

Another consideration, is in terms of the process of negotiation that are changed and its ins- titutionalization do not always depend on the type of negotiation established; that is to say, if it is bilateral o between a bloc with a third State. Therefore, the studied cases helped us to achieve important information on the time of the processes of negotiation, the number of countries which there has been established economic integration, and the number of successful agreements that Colombia, South Korea and Mercosur that have concluded.

Another one consideration indicates that the level of institutionalization of relation can be analy- zed qualitatively and quantitatively. The first one by means of descriptive exercises of the relations among the actors, in this case between South Korea - Mercosur and South Korea- Colombia. And the second one by means of the compilation of information that realize in the negotiation processes that have had Colombia, South Korea and Mercosur with the rest of world.

An important element that the present research shows was a dual development of the negotia- tion processes with a bloc. While, negotiating with a bloc is more attractive because it condenses a large market and major negotiation´s capacity; on the other hand, it is more complex and needs more time to consolidate an institution like FTA due to the fact that more political units are present with diverse interests and different national identities.

Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism: www.mincomercio.gov.co

Other relevant aspect that concludes this paper is the differences of impact that bilateral nego- tiation has in relation with one between a bloc and a third country. The bilateral negotiation, since the strategies applied in the process and the result that it throws as such are focused on only two States. On the other hands, the negotiation with a bloc is submitted to the individual interests of every State and involves several political units. In this case, Mercosur it includes four member States, and also there become present the bloc´s own interests that differ, in occasions, from its members.

Finally, is it better to negotiate bilaterally or as a bloc? In relation at the time that the negotia- tion processes are late, it is better to negotiate bilaterally because the agreements achieve a faster conclusion on average, that is to say, the commercial relations it become institutionalized in minor number of months. As for the commercial attraction, given the importance and magnitude of the market, it is better to negotiate in bloc though the rules of the game are delayed in constructing it.

REFERENCES

Ainsworth, S. (2002) Analyzing Interest Groups, Group Influence on People and Policies, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., ISBN 0-393-97708-0.

Alchian, A. [ 2007] Uncertainty, Evolution, and Economic Theory , the Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 58, No. 3. [ Jun., 1950 ], pp. 211-221.

Axelrod, R. (1986) An Evolutionary Approach to Norms, The American Political Science Review, Vol. 80, No. 4, pp. 1095-1111 Bates, S., Faulkner, W., Parry, S. & Cunningham-Burley, S. (2010) “How do we know it’s not been done yet?!’ Trust, trust building and regulation in stem cell research, Science and Public Policy

Behn, R., (1988) Management by Groping Along, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp. 643-663

Brinks, D. (2003) Informal Institutions and the Rule of Law: The Judicial Response to State Killings in Buenos Aires and Sao Paulo in the 1990s, Comparative Politics, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 1-19, American Sociological Review, Vol. 44, 553-572

Carroll, G. & Delacroix, J. (1982) Organizational Mortality in the Newspaper Industries of Argentina and Ireland: An Ecological Approach, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp.169-198

Cardona, P. & Wilkinson, H. (2009) Building the Virtuous Circle of Trust, Fourth Quarter Issue 3

Chavance, B. [2008] Formal and informal institutional change: the experience of postsocialist transformation, The European Journal of Comparative Economics, Vol. 5, n. 1, pp. 57-71

Chávez, R. (2004) The Rule of Law in Nascent Democracies: Judicial Politics in Argentina, Stanford University Press, 288 pp.

Elsbach, K.D. & Sutton, R.I. (1992). Acquiring organizational legitimacy through illegitimate actions: A marriage of institutional and impression management theories. Academy of Management Journal, 35: 699-738.

Edelman, L. (1992) Legal Ambiguity and Symbolic Structures: Organizational Mediation of Civil Rights Law, University of Chicago, Vol. 97, No. 6, pp. 1531-76

Darden, K. (2003), Graft and Governance: Corruption as an Informal Mechanism of State Control, Department of Political Science Yale University

Deephouse, D.L., & Suchman, M.C. (2008). Legitimacy in organizational institutionalism. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism. pp. 49-77.

Deininger, K. (1999) Making Negotiated Land Reform Work: Initial Experience from Colombia, Brazil and South Africa. World Development Vol. 27, No. 4, pp. 651±672.

DiMaggio, Paul J. and Walter W. Powell. (1991) The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, Chicago: University of Chi- cago Press.

Di Maggio, P.J. & Powell, W.W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48: 147-160.

Di Masi, J. (2006) Relaciones preferenciales MERCOSUR-Corea: Perspectivas de una idea en construcción. Revista HMiC, número IV, http://seneca.uab.es/hmic.

Farrell, H. & Héritier, A. ( 2002) Formal and Informal Institutions under Codecision: Continuous Constitution Building in Europe, European Integration on line Papers (EIoP) Vol. 6, No.3

Florini, A. (1996) The Evolution of International Norms, International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 40, No. 3, Special Issue: Evolutionary Paradigms in the Social Sciences, pp. 363-389

Gelman, V. (2004) The Unrule of Law in the Making: the Politics of Informal Institution Building in Russia, Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 56, No. 7, pp. 1021-1040

Giddens, A. (1984) La constitución de la sociedad: bases para la teoría de la estructuración. Amorrortu editores.

Goodrick, E. & Salancik, G. (1996). Organizational discretion in responding to institutional practices: Hospitals and Cesearean births. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41: 1-28.

Helmke, G. & Levitsky, S. (2004) Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics: A research Agenda. Perspectives on Politics, Vol. 2, N°4 pp. 725-740

Helmke, G. & Levitsky, S (2006) Informal Institutions and Democracy: Lessons from Latin America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. 351 pp. ISBN 978-0-8018-8352-1

Hernández Umaña, I. & Rosado Salgado, L. (2009) Las Instituciones del Estado y los Grandes Conglomerados Industriales como Determinantes del Cambio Estructural en Corea del Sur y Colombia. Revista de Economía del Caribe, 2009

Hodgson, G. ( 2006) What Are Institutions?, Journal of Economic Issues, Vol. XL, No. 1

Kim, Won Ho (2010). “Perspectivas de las Negociaciones por TLC Corea-MERCOSUR: Implicancia de la estructura y negociacio- nes previas del MERCOSUR” en Mera y Nessim compiladoras Desafíos de la contemporaneidad Corea-América Latina. Buenos Aires: Editorial Antropofagia

Kraatz, M.S. & Zajac, E.J. (1996), “Exploring the limits of the new institutionalism: The causes and consequences of illegitimate organizational change”, American Sociological Review, 61(5): 812-836.

Lauth, H., (2004) Formal And Informal Institutions: On Structuring Their Co-Existence, Romanian Journal of Political Science Vol 4 - No 1.

Leblebici, H., Salancik, G., Copay, A., & King T. (1991). Institutional change and the transformation of inter-organizational fields: An organizational history of the U.S. radio

Luna, C (2009) El Constructivismo Social ¿Una teoría para el estudio de la Política o un esquema para el análisis de la Política Ex- terior de los Estados?. Ponencia presentada en las Jornadas del Área de Relaciones Internacionales de FLACSO Argentina Las Relaciones Internacionales: Una disciplina en constante movimiento.

Lynall, M., Golden, B. & Hillman, A. (2003) Board Composition from Adolescence to Maturity: A Multitheoretic View, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 416-431

Malamud, Carlos (2012). UE y Mercosur: negociaciones sin futuro. http://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/wps/portal/rielcano/ contenido?WCM_GLOBAL_CONTEXT=/elcano/elcano_es/zonas_es/america+latina/ari61-2012_malamud_ue_mercosur

Mazzucato, V. & Niemeijer, D. (2002) Population Growth and the Environment in Africa: Local Informal Institutions, the Missing Link, Economic Geography, Vol. 78, No. 2, pp. 171-193

McGillivray, F. & Smith, A. (2000) Trust and Cooperation Through Agent-specific Punishments, International Organization 54, 4, pp.809-824

Meyer, J. & Rowan, B. (2008) Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony, The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 83, No. 2, pp. 340-363

Meyer, J., Scott, W., & Deal, T., (1980) Institutional and Technical Sources of Organizational Structure Explaining the Structure of Educational Organizations, Institute for Research on Educational Finance and Governance.

Milanese, J. (2007). Colombia & Venezuela: Interpresidencialism and regional integration. Colección El árbol de las garzas, Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias Sociales, Universidad Icesi. ISBN: 978-958-9279-92-2

Moisio, S. (2008) From Enmity to Rivalry? Notes on National Identity Politics in Competition States, Scottish Geographical Journal, Vol. 124, No. 1, 78-95

North, D. (1990) Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, Cambridge University Press North, D. (1992) The New Institutional Economics and Development, Washington University Press

O’Donnell, G. (1998) Horizontal Accountability in New Democracies, Journal of Democracy - Volume 9, Number 3, pp. 112-126 Ping Li, P. (2008) Toward a Geocentric Framework of Trust: An Application to Organizational Trust, Journal compilation Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Prantl, J. (2005) Informal Groups of States and the UN Security Council, International Organization, Vol. 59, No. 3, pp.559-592 Powell, W. & DiMaggio, P. ed. (1991) The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, The University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-67709-5

Redmond, W. (2005) A Framework for the Analysis of Stability and Change in Formal Institutions, Journal of Economic Issues, Vol. XXXIX, No. 3

Ritti, R. & Silver, J. (1986) Early Processes of Institutionalization: The Dramaturgy of Exchange in Interorganizational Relations, Administrative Science Quarterly, 31: 25-42

Rimoldi de Ladmann, E. (2000) El Este asiático y las relaciones exteriores del Mercosur. Una nueva frontera, en Análisis De La Di- námica Política, Económica Y Social De Asia-Pacífico En Sus Relaciones Con La Argentina. Cuadernos de Estudio de las Relaciones Internacionales Asia-Pacífico-Argentina, Nº 1

Russell, R. & Tokatlian J.G. (2000) Neutralidad y Política Mundial: una mirada desde las relaciones internacionales, Análisis Político, N° 40 1vol, 25 pp-40 pp

Sartori, G. (2001), Ingeniería constitucional comparada. Una investigación de estructuras, incentivos y resultados, 2a. ed., trad. de Roberto Reyes Mazzoni, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 247 pp.

Selznick, P. (1948). Foundations of the theory of organization. American Sociological Review, 13: 25-35.

Sivakumar K. & Nakata, C. (2001). The Stampede Toward Hofstede´s Framework: Avoiding the Sample Design Pit in Cross-Cultural Research. Journal of International Business Studies, 32, 3.

Stinchcombe, A. (1965). Social structure and organizations, in James G. March (ed.) Handbook of Organizations. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally. 142-193.

Startsev, Y. (2005) “Informal” Institutions and Practices: Objects to Explore and Methods to Use for Comparative Research, Pers- pectives on European Politics and Society, 6:2

Suchman, M.C. (1995) Managing legitimacy: strategic and institutional approaches, Academy of Management Review. 20:571-610. Scott H. Ainsworth (2002) Analyzing Interest Groups: Group Influence on People and Politics (New Institutionalism in American Politics), W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0393977080

Tak Wing Yiu & Wai Ying Lai (2009) Efficacy of Trust-Building Tactics in Construction Mediation, Journal of Construction Engi- neering and Management

Taylor, M. ( 1992) Formal versus Informal Incentive Structures and Legislator Behavior: Evidence from Costa Rica, The Journal of Politics, Vol. 54, No. 4, pp. 1055-1073

Tolbert, P. & Zucker, L. ( 1983) Institutional Sources of Change in the Formal Structure of Organizations: The Diffusion of Civil Service Reform, 1880-1935, Administrative Science Quarterly, 28: 22-39

Useem, M. (1979) The Social Organization of the American Business Elite and Participation of Corporation Directors in the Go- vernance of American Institutions, American Sociological Review, Vol. 44, 553-572

Urán, C. (1986) Colombia y los Estados Unidos en la Guerra de Corea. Working Paper #69, Colombia´s Council of State.

Walt, S. (1998). International Relations: One World, many theories. Foreign Policy, No. 110, Special Edition: Frontiers of Knowled- ge, pp. 29-32+34-46

Wendt, A. (1992). Anarchy is what states make of it: the social construction of power politics in International Organization, vol. 46, no. 2.

Wendt A. (1987). The agent-structure problem in international relations theory in International Organization, vol. 41, no. 3. Williamson, C. (2009) Informal institutions rule: institutional arrangements and economic performance, Public Choice 139: 371-387. Zald, M, & Denton, P. (1963). From evangelism to general service: The transformation of the YMCA. Administrative Science Quarterly, pp. 214-234.

Fecha de recepción: 24/08/2014 Fecha de aprobación: 01/11/2014

Web Sites

Foreign Trade Information System- Organization of American States: http://www.sice.oas.org/tpd_s.asp Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism: www.mincomercio.gov.co

Mercosur: http://www.mercosur.int

Ministry of Economy of Argentina: http://www.mecon.gov.ar/comercioexterior/. Ministry of Development of Brazil: http://www.desenvolvimento.gov.br/sitio/.

Ministry of Economy and Finance of Uruguay: http://www.mef.gub.uy/portada.php. Ministry of commerce of Paraguay: http://www.mic.gov.py/

World Bank, (2013). “World Development Indicators”: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/WDI-2013-ebook.pdf

Press: “Para empresarios brasileños el Mercosur “está muerto””. (24 de septiembre de 2013) en www.losandes.com.ar

Notas

1 Artículo de prensa: “Para empresarios brasileños el Mercosur “está muerto””. (24 de septiembre de 2013) en www.losandes.com.ar

2 Mercosur´s website: http://www.mercosur.int/t_generic.jsp?contentid=3862&site=1&channel=secretaria&seccion=3

3 In this sense, the author advises a revision of the most advanced agreement signed by Mercosur and an extraregional partner: APC MERCOSUR-India. Due to both economies are complementary, typically North-South exchange, it could contribute as a suitable example. See Won Ho Kim (2010). “Perspectivas de las Negociaciones por TLC Corea-MERCOSUR: Implicancia de la estructura y negociaciones previas del MERCOSUR” en Mera y Nessim compiladoras Desafíos de la contemporaneidad Corea- América Latina. Buenos Aires: Editorial Antropofagia, p. 18