Fuente: Autoría propia

Tourism and creative destruction in Mazatlan, Mexico.

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

Turismo y destrucción creativa en Mazatlán, México.

La zona de Playa Norte (2009-2024)

Tourism and creative destruction in Mazatlan, Mexico.

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

Turismo e destruição criativa em Mazatlan, México.

A zona da Praia Norte (2009-2024)

Jesús Bojórquez Luque

Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, México

bojorquez@uabcs.mx

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1745-4979

Julio Ernesto Osuna Covarrubias

Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa, México

julio.osuna@uas.edu.mx

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1133-4511

How to cite this article:

Bojórquez, J. y Osuna, J.E. (2025). (2025). Tourism and creative destruction in Mazatlan, Mexico. The Playa Norte area (2009-2024). BITÁCORA URBANO TERRITORIAL, 35(I): 167-181.

https://doi.org/10.15446/bitacora.v35n1.117255

Recibido: 28/10/2024

Aprobado: 16/12/2024

ISSN electrónico 2027-145X. ISSN impreso 0124-7913. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá

(1) 2025: 167-181

Autors

02_117255- E

Abstract

Mazatlán, a tourist city in the Mexican state of Sinaloa, has undergone a process of creative destruction since the opening of the Mazatlán-Durango highway, which facilitated connectivity with the northern states of the country, increasing the arrival of national tourism. One of the areas impacted by this phenomenon is the traditional residential and recreational area of Playa Norte. With the objective of analyzing the phenomenon of creative destruction in the Playa Norte area from the perspective of critical geography, a mixed methodology is used based on the consultation of INEGI’s DENUE data, georeferencing of constructions in GIS, current and historical photographic records from Street View in Google Maps, and field observation. It is concluded that the dynamization of tourist activity in Mazatlan has resulted in the regeneration of some buildings and the demolition of others, with the consequent construction of new ones, to be used for second homes and lodging, or for consumer businesses, such as restaurants and convenience stores, which shows that the processes of creative destruction of urban spaces that did not fit into the logic of profit maximization have taken a new direction.

Keywords: creative destruction, spatial neoliberalization, tourism, urban development, urban space

Resumen

Mazatlán, ciudad turística del estado mexicano de Sinaloa, ha experimentado un proceso de destrucción creativa a partir de la apertura de la carretera Mazatlán-Durango, lo que facilitó la conectividad con estados del norte del país, aumentando la llegada de turismo nacional. Una de las zonas impactadas por dicho fenómeno es la zona habitacional tradicional y de recreo de Playa Norte. Teniendo como objetivo analizar desde la geografía crítica el fenómeno de destrucción creativa en la zona de Playa Norte, se utiliza una metodología mixta con base en la consulta de datos del DENUE del INEGI, georreferenciación de construcciones en SIG, registros fotográficos actuales e históricos de Street View en Google Maps, y observación de campo. Se concluye que la dinamización de la actividad turística en Mazatlán ha traído como consecuencia la regeneración de algunos edificios y la demolición de otros, con la consecuente construcción de nuevos, para destinarlos al segmento de segundas residencias y hospedaje, o para negocios de consumo, como restaurantes y tiendas de conveniencia, lo que evidencia el encaminamiento de los procesos de destrucción creativa propia de los espacios urbanos que no entraban en la lógica de la maximización de la ganancia.

Palabras clave: destrucción creativa, neoliberalización espacial,, turismo, desarrollo urbano, espacio urbano

Resumo

Mazatlán, uma cidade turística no estado mexicano de Sinaloa, passou por um processo de destruição criativa desde a abertura da rodovia Mazatlán-Durango, que facilitou a conectividade com os estados do norte do país, aumentando a chegada do turismo nacional. Uma das áreas afetadas por esse fenômeno é a tradicional área residencial e recreativa de Playa Norte. Para analisar o fenômeno da destruição criativa na área de Playa Norte a partir da perspectiva da geografia crítica, foi utilizada uma metodologia mista baseada na consulta de dados do DENUE do INEGI, no georreferenciamento de construções no GIS, em registros fotográficos atuais e históricos do Street View no Google Maps e na observação de campo. Conclui-se que a dinamização da atividade turística em Mazatlán resultou na regeneração de alguns edifícios e na demolição de outros, com a consequente construção de novos, para serem usados como segundas residências e acomodações, ou para negócios de consumo, como restaurantes e lojas de conveniência, o que mostra que os processos de destruição criativa de espaços urbanos que não se encaixavam na lógica da maximização do lucro tomaram uma nova direção.

Palavras-chave: destruição criativa, neoliberalização espacial, turismo, desenvolvimento urbano, espaço urbano

Résumé

Mazatlán, ville touristique de l’État mexicain de Sinaloa, a connu un processus de destruction créative depuis l’ouverture de l’autoroute Mazatlán-Durango, qui a facilité la connectivité avec les États du nord du pays, augmentant ainsi l’arrivée du tourisme national. L’une des zones touchées par ce phénomène est la zone résidentielle et récréative traditionnelle de Playa Norte. Afin d’analyser le phénomène de destruction créatrice dans la zone de Playa Norte du point de vue de la géographie critique, une méthodologie mixte est utilisée, basée sur la consultation des données du DENUE de l’INEGI, le géoréférencement des constructions dans le SIG, les documents photographiques actuels et historiques de Street View dans Google Maps, et l’observation sur le terrain. La conclusion est que la dynamisation de l’activité touristique à Mazatlán a entraîné la régénération de certains bâtiments et la démolition d’autres, avec pour conséquence la construction de nouveaux bâtiments destinés à des résidences secondaires et à des logements, ou à des entreprises de consommation, telles que des restaurants et des magasins de proximité, ce qui montre que les processus de destruction créative des espaces urbains qui ne s’inscrivaient pas dans la logique de maximisation du profit ont pris une nouvelle direction.

Mots-clés : destruction créative, néolibéralisation spatiale, tourisme, développement urbain, espace urbain.

Introduction

The French thinker Henri Lefebvre (2013), in his seminal work The Production of Space, argues that space should not be seen as a neutral element, but rather as one with a significant political-ideological charge, since it is produced by human beings, thereby revealing relations of power. In this sense, capitalism is not only based on companies, industries, and the market of goods and services, but it also makes use of space, which becomes fundamental for the reproduction of capital, especially for an emerging activity known as the leisure industry. This industry tends to appropriate not only vacant spaces such as mountains, beaches, the sea, and landscapes, but also tangible and intangible cultural heritage, resulting in phenomena of urban regeneration and gentrification.

Consequently, the construction of new infrastructures for tourism, such as hotels and restaurants, plays a key role in mechanisms of capital reproduction. These processes drive innovation and market re-foundation, responding to the growing demand of the tourism sector and consolidating dynamic processes of creative destruction.

Since the opening of the Mazatlán-Durango highway in 2013, Mazatlán has achieved smoother access to markets in northern states such as Durango, Coahuila, Chihuahua, Nuevo León, and Zacatecas, among others. This has fueled a boom both in tourism and the real estate market, especially in the development of vertical constructions along the coastal boardwalk area (Bojórquez et al., 2023). In this zone, apartments have been built functioning as second homes or rented through platforms such as Airbnb, thereby consolidating the process of residential segregation. This phenomenon has promoted the densification of consolidated urban sectors, while in the periphery—where tourism workers reside—significant lag persists in infrastructure and services.

The present research aims to analyze the processes of creative destruction from the perspective of critical geography in the coastal tourist city of Mazatlán during the period 2009 to 2024, specifically in the Playa Norte area, which exhibits gradual renewal of some buildings and replacement of others by new constructions destined for commerce, second homes, and the restaurant sector.

This work is structured in three sections. The first develops the theoretical-conceptual framework centered on critical geography and, specifically, on the concept of creative destruction as applied to the urban and tourism context. The second outlines the methodology, which is mixed-methods, utilizing data from the National Statistical Directory of Economic Units (DENUE) of the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), georeferencing of constructions via Geographic Information Systems (GIS), current and historical photographic records from Google Maps Street View, and field observation. The third section develops the case study, beginning with a characterization of Mazatlán city, then examining manifestations of creative destruction observed in the remodeling or replacement of old buildings by new economic units, many of which are allocated to commercial, restaurant, housing, and second home sectors. These transformations have significantly impacted the Playa Norte zone within the context of touristification and spatial neoliberalization. Cartographic and photographic evidence illustrating the current situation of the phenomenon is provided. Finally, conclusions are presented as an integrative reflection on the problem stated.

Theoretical Framework

This section builds upon the urban critical theory proposed by geographer David Harvey, who adapted Joseph Schumpeter’s concept of creative destruction to urban issues, referring to modifications of the built and unbuilt environments of cities or tourist localities.

Creative Destruction, City, and Tourism

Originally used by Schumpeter (2010), the concept of creative

destruction referred to the vitality of the capitalist system to

reconfigure itself through innovation in its products and processes,

leaving behind elements of the past that were surpassed in efficiency,

productivity, and quality by the new ones.

In this way, capitalism finds a spatial solution to its recurrent crises (Harvey, 2001), focusing on the opening of new spaces for business development, among which tourism stands out. This translates into the creation of new infrastructure, such as hotels, or the regeneration of old historic centers and industrial areas to promote cultural tourism, equipping them with facilities such as bars, restaurants, boutique hotels, and art galleries, among others. These urban centers are regenerated and gentrified through real estate speculation in housing, since their advantages in location and centrality force the original population to move to the peripheries, turning working-class or lower-middle-class neighborhoods into consumption centers (Harvey, 2008), in line with the development of the so-called leisure industry.

Within this framework of planetary urbanization affirmed by Brenner (2013), there is an articulation so that spaces become pillars of accumulation and generate large infrastructure projects as part of the primacy of the urban, where investments are territorialized with the purpose of energizing the capitalist model in its neoliberal stage. One way to concretize the dynamization of capitalism as a form of accumulation is through so-called creative destruction (Dlongolo et al., 2024), where various infrastructures, buildings, and natural areas are transformed or refurbished for profit.

Particularly in heritage cities, processes of regeneration, conservation, and removal are part of this creative destruction phenomenon, as is the demolition of old structures and the reorientation of the use of buildings of great historical value towards new forms of consumption (Dlongolo et al., 2024). Ultimately, all of this aims to extend the useful life and profitability of these spaces oriented towards tourism activities.

This process of neighborhood renewal, through the remodeling or demolition of deteriorated buildings or those without significant economic value, is known as creative destruction. It involves modifying or eliminating what is considered obsolete or unprofitable to revitalize it materially and spatially, contributing to strengthening capital accumulation circuits. In this context, Fernández (2024) argues that creative destruction seeks to energize profit margins by reinventing urban materiality through demolitions, renovations, and the creation of attractive architectural environments that generate atmospheres conducive to consumption.

The capitalist logic drives a tendency towards creative destruction in the urban sphere when buildings cease to respond to the logic of profit maximization. In these cases, buildings are restored or demolished to make way for new constructions (Charney, 2024) that meet current demand, taking advantage of their strategic location in the urban fabric and existing service infrastructure. This process, favored by an institutional framework that encourages real estate speculation, fosters gentrification environments, attracting sectors with greater purchasing power and displacing precarious populations due to the neoliberal model.

According to Richard (2024), creative destruction occurs as the old tends to disappear for new structures, not only materially but also through market trends, where the innovative prevails. This process is normalized in urban development plans that preemptively propose creativity and modernization of the city. Thus, past structures are continuously destroyed, except when the community recognizes certain spaces and buildings as cultural heritage to be rescued, remodeled, and commodified to attract visitors. All of this happens within a normative framework that facilitates spatial changes (Brenner et al., 2015), integrating these processes into the capitalist accumulation machinery.

As Gutiérrez (2020) points out, creative destruction implies the physical disappearance of socially constructed built environments produced on urban land through spatial solutions aimed at increasing their value and accumulation potential. This process materializes in large real estate projects that become attractive in a competitive market, in which cities compete for foreign investments to attract visitors (Minhui and Jigang, 2015).

Tourism, therefore, is based on creative destruction, adapting spaces according to consumer demand. This drives constant spatial changes and destination renewal, as well as the creation of new ones (Ying, 2022), based on the commodification of both natural and cultural heritage (Yang et al., 2021). This process continuously evolves to replace inefficient strategies and infrastructures (Asgari et al., 2022), strengthening the viability of leisure activities and transforming low-profit tourism systems into dynamic and innovative ones.

Tourism revitalization is thus carried out through creative destruction, which includes remodeling old urban cores and selling themed environments, as well as the construction of hotel infrastructure (Espino et al., 2023). This process involves both the transformation of natural areas and the demolition of obsolete infrastructure that has ceased to be profitable.

In this vein, the city of Mazatlán, which long languished as a traditional beach tourism destination, has, through investment in road connectivity, triggered a renewal process to reinforce accumulation mechanisms, generating large investments that impact space and social relations that once incubated there. Many of these investments are materializing in the coastal zone, along the boardwalk, in vertical constructions for higher-income classes, which, as Lefebvre (2013) states, are an expression of power, contrary to the underground that represents death and horizontality, which alludes to submission.

Thus, the Mazatlán boardwalk area has entered a dizzying spiral of spatial neoliberalization, with a process of creative destruction, where apartment towers emerge (Bojórquez et al., 2023), a process that does not exclude the Playa Norte area, altering the past ways of life of fishermen (Bojórquez and Osuna, 2024), neighbors, and old businesses, which are transformed based on tourist demand and new space owners.

Methodology

This research is based on critical geography to analyze the spatial changes experienced in the city of Mazatlán, specifically in the Playa Norte area. This area is characterized as a traditional residential zone where the working-class population has historically lived. It is also home to the city’s only cooperatives dedicated to artisanal fishing.

A mixed-methods approach structured in five stages was used for this research. First, a theoretical and conceptual framework was constructed based on critical geography, focusing on the concept of creative destruction initially proposed by Joseph Schumpeter for business innovation and later adapted to critical geography by David Harvey. Second, field observations were conducted in July, September, and October 2024 to understand the dynamics of spatial neoliberalization and creative destruction in the area. Third, using the DENUE database from INEGI, the economic units located in the Playa Norte area were identified within the 2009–2024 timeframe. Fourth, georeferencing of new constructions was carried out as part of the creative destruction phenomenon consolidating spatial neoliberalization processes through Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Fifth, historical photographic analyses were performed using Google Maps Street View and photographs taken by the authors, documenting changes from 2009 until October 2024, during the last field observation, in terms of remodeling, demolition, and construction of new buildings.

Results and Discussion

The case study addresses the phenomenon of creative destruction occurring in the Playa Norte area of the city of Mazatlán. This city is located in the Mexican state of Sinaloa, specifically 21 kilometers from the Tropic of Cancer, between the meridians 105° 56’55” and 106° 37’10” west of the Greenwich meridian, and between parallels 23° 04’25” and 23° 50’22” north latitude (see Figure 1).

The city of Mazatlán, known in the tourism marketing sphere as The Pearl of the Pacific, is famous for its extensive beaches and richness in marine and fishing species, which have resulted in a culinary diversity based on fish and seafood—some of its main attractions. Alongside this, Mazatlán is one of the deep-water ports of the Pacific, a status it has held since 1820, consolidating as a commercial port from the mid-19th century where mercantile and industrial activities coexisted, without tourism being prominent (Santamaría, 2002). Although tourism was not developed at that time, like any port, it had a cosmopolitan atmosphere due to the arrival of foreigners who extended their stays in the city for commercial purposes and took advantage of the opportunity to engage in leisure activities.

By the late 19th century, leisure activities began to consolidate with the origin of the carnival festivities, marking the beginning of tourism by attracting visitors for this reason. The year 1922 is significant for tourism activity as the Belmar Hotel was inaugurated—the first hotel located on the seafront, taking advantage of the environment and landscape. This event made Mazatlán attractive to visitors from the United States, particularly from border states like Arizona and California.

In recent years, as a result of the housing construction boom, the real estate sector has become the largest contributor to the municipal GDP (Gross Domestic Product), influenced by improved connectivity with other states in the country, which has led to an increase in tourist flow to the port, along with a corresponding demand for lodging and food services.

Currently, Mazatlán stands out as one of Mexico’s main traditional sun-and-beach tourist destinations. Although it experienced stagnation in the consolidation of its tourism infrastructure during the 1980s, as noted by Bojórquez et al. (2023), it has recently undergone a notable resurgence. This revival coincides with the opening of the Mazatlán-Durango highway, which triggered a significant surge in investments aimed at building new hotels and second-home buildings, especially in the coastal zone and its surroundings.

This process has brought about spatial neoliberalization and consolidated processes of segregation and spatial polarization. The current panorama reflects a changing dynamic in the urban configuration of Mazatlán, where investment and tourism development have significantly redefined the appearance and function of these areas, generating both opportunities and challenges for the local community.

Playa Norte, Tourism, and Fishing

Located next to Punta Tiburón, specifically at coordinates 23° 10’ N latitude and 106° 30’ W longitude, Playa Norte was initially named Bahía Ensenada Puerto Viejo or Bahía San Félix, which served as a docking and shelter point for vessels. The beach in this area is sandy, with some rocky points visible during low tide. This part of the Mazatlán coastline is located along the coastal boardwalk, adjacent to an old residential area, extending for about one kilometer (see Figure 2). This zone, with its privileged location, stands out for the beauty of its beaches and sunsets, and is home to fishing cooperatives that contribute significant identity value to the city.

In the last decade, the Playa Norte sector has undergone renovations aimed at enhancing its image and services toward tourism, benefiting especially the entrepreneurs in this sector. Its strategic location within the city and along the coastal promenade, one of Mazatlán’s main tourist icons (Valdez, 2006), makes it a potential site of conflict and territorial dispute. Over the past two decades, the area has been urbanistically intervened, consolidating processes of spatial neoliberalization, with the opening of restaurants targeted at tourists and the construction of luxury apartment towers for upper-middle and upper classes, which disrupt the landscape with steel and concrete structures.

Since the 1960s, Playa Norte has been one of the most frequented beaches by local, national, and foreign bathers, including areas such as Olas Altas, Las Gaviotas, El Sábalo, El Camarón, Isla de la Piedra, and Isla de Soto (Espinoza, 2018). A notable feature of this area is the historic presence of artisanal coastal fishing cooperatives. This activity began when residents obtained concessions for the exploitation of marine products, the first of its kind in Mazatlán. From there, other fishing collectives were formed, such as the one at the Isla de la Piedra Gabriel Leyva pier (Sánchez Buelna, 2022).

The fishermen of Playa Norte have become an icon of the coastal landscape, with their small boats anchored on the sand and setting out at dawn to catch species such as sierra, dorado, pajarito, botete, mojarra, and cochito blanco (Valdez, 2006), which are essential for their families’ livelihood. It is common for these fishermen to sell fresh seafood to neighbors, Mazatlán residents, and even tourists, who often prepare them in vacation rental homes. The Playa Norte area is characterized by restaurants that offer direct views of the beach, which is attractive to customers. These establishments specialize in preparing seafood, many of which come from the region’s fishing cooperatives.

In recent years, due to the decline in the catch of traditionally exploited species, the fishermen of Playa Norte have sought to diversify their activities by offering tourist services such as boat tours around the Rocas Blancas area, sea lion watching, and visits to Isla Venados (Díaz et al., 2021). Within the framework of neoliberalization and touristification, a floating water park was installed in 2019. However, this project was rejected by the fishermen, who expressed concern about the potential negative impact on their activity, fearing it would affect the spawning areas of the pajarito and other species, as well as having repercussions on the ecological environment.

Processes of Creative Destruction in Playa Norte

In recent years, the boardwalk and the Playa Norte area have undergone a series of urban transformations that, according to Harvey (2008), reflect the creative destruction of space to adapt it to the new needs of capital. These interventions involve a redefinition of contiguous buildings within the logic of gentrification, tending toward the commodification of leisure, materialized in the establishment of restaurants, bars, and the construction of vertical buildings aimed at the second-home sector. However, these changes have not been free from neighborhood conflicts due to the collapse of potable water, sewage, and electricity systems. This is because the infrastructures are subjected to a demand greater than anticipated.

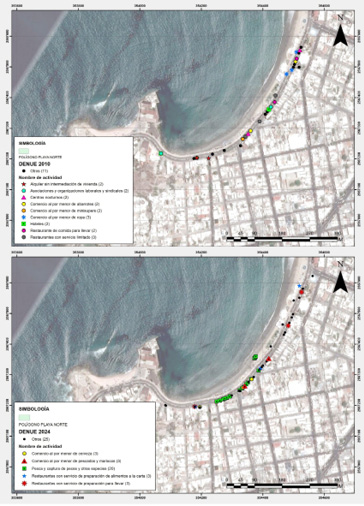

Prior to the real estate and tourism boom in Mazatlán, driven by the opening of the Mazatlán-Durango highway and the increase in tourist flow and investments in the region (Bojórquez et al., 2023), in 2010 there were 31 economic units registered in the Playa Norte area, according to DENUE data. Among these units stood out two housing rental businesses without intermediaries, two union organizations, two nightclubs, two retail stores, three clothing shops, two hotels, two take-out restaurants, and three sit-down restaurants (see Figure 3).

The figures provided by DENUE for 2010 contrast with the registry results for 2024, where the area increased from 31 economic units to 57, demonstrating greater economic dynamism. Notably, there are three retail beer businesses supplying both the local population and tourists who consume them along the boardwalk and the beach; three retail businesses selling fish and seafood, which reflects the intermediation of marine products at the expense of the production by fishermen in the established cooperatives. What has grown dramatically is the presence of 20 economic units involved in fishing and capture of fish and other species, affecting the fishing cooperatives that traditionally held concessions for the exclusive development of the activity, revealing a tendency toward the liberalization of this sector.

Thus, over the last 15 years, a series of changes have been observed that consolidate the governmental and business vision that real estate tourism development is beneficial not only for the companies in the sector but also for the broader social fabric of Mazatlán. However, this vision is actually part of discursive forms of accumulation through legitimation (Da Costa, 2022). In this way, residential and spatial segregation is reinforced, giving preeminence to the coastal zone, to the detriment of the back areas of the city, where most tourism sector workers reside (Osuna and Calonge, 2022). These areas show major deficiencies in urban infrastructure, resulting in high economic and ecological costs associated with commuting to workplaces.

Within the context of spatial neoliberalization, gentrification, and creative destruction, the Playa Norte area is already experiencing verticalization of the tourist space, as is the rest of the city’s boardwalk (Bojórquez et al., 2023). This process generates not only economic impacts but also social and cultural effects, impacting local residents who face problems such as drainage system failures, potable water shortages, garbage collection issues, and traffic congestion due to increased vehicular flow.

Based on analysis of historical photographs and field visits, four vertical buildings were identified prior to 2010; however, in recent years their number has drastically increased with the construction of seven new towers as part of the touristification process. Asgari et al. (2022) describe these as new ways to meet demand in the tourism and residential sectors, but which only satisfy the demands of the upper classes (see Figure 4). These buildings promote the sale of apartments, highlighting environmental services related to the landscape and proximity to the sea. Prices range between three and five million pesos per unit, from lofts to one-, two-, and three-bedroom apartments. Such market values are unattainable for most local residents, so these units are primarily intended for national or foreign buyers who use them as second homes and, in some cases, for vacation rentals.

Based on the above, the effects of urban renewal and creative destruction experienced from 2010 to 2024 in the study area can be observed, aimed at making the zone more attractive, similar to the rest of the city’s coastal strip. Evidence of this is the modernization of the park adjacent to the Fisherman’s Monument, which was equipped with amenities such as playground equipment and a basketball court for use by locals and visitors. Likewise, as part of tourism marketing strategies to further consolidate the city brand, giant letters spelling “Mazatlán” were installed so visitors can take photos and document their visit to the port—a trend of high commodification, as Yang et al. (2017) observe in the case of China’s industrial heritage. Additionally, the boardwalk, as a product of its latest remodeling, includes a bike lane for the enjoyment of tourists and locals.

Changes in the Playa

Norte Zone as a Result of Creative Destruction

The Playa Norte area has undergone changes aimed at the elitization of the coastal space, with substantial changes and modifications to the urban image that alter the identity and original social dynamics (Charney, 2024), typical of traditional working-class neighborhoods. Based on the repository of historical photographs from 2009 and current ones from 2024, seven major projects that have transformed the appearance of the area are confirmed (see Table 1).Source: Own elaboration based on historical photographs from Google Maps Street View and authors’ archive (10/26/24).

One of the most notable interventions in the area is the case of the restaurant El Muchacho Alegre (1), which replaced the iconic Puerto Azul, a restaurant that had been in operation since 1946. El Muchacho Alegre offers a gastronomic proposal focused on seafood, accompanied by Sinaloan banda music, typical of the region, which is highly attractive to tourists. However, the restaurant has occupied a large part of the beach, specifically the so-called maritime-terrestrial zone, legally considered public under Mexican law, limiting access and enjoyment for both local residents and visitors. This elitization within the contexts of creative destruction not only affects Mazatlecos but also manifests in other places, as exposed by Dlongolo et al. (2024) in cases such as Makhanda, South Africa.

This privatization of the coastline has also impacted fishermen from cooperatives settled in the area, who have lost necessary space for their work and storage of fishing gear. According to Dlongolo et al. (2024), this affects cultural landscapes as part of creative destruction processes. These situations reflect the privatization of spaces of representation and spatial practices (Lefebvre, 2013), key elements for social coexistence and the cultural symbols that have historically characterized this place as an identity landmark for its inhabitants and frequent visitors.

Opposite El Muchacho Alegre is the restaurant Agustito Sunset (2), located in the space formerly occupied by the bar Rincón Bohemio, a site frequented by cooperative fishermen and local residents. The transformation of the area towards a tourist profile has caused growing vehicular congestion and alterations in public roads, largely due to the behavior of some intoxicated tourists and the constant flow of collective tourist transport units known as ‘aurigas,’ which include loud music as part of their attraction.

These changes are also particularly evident in the disappearance of emblematic buildings such as the Club Nauty bar (3), which featured a conceptual boat architecture and was replaced by a convenience store of the Kiosko chain. Similarly, the boardwalk was remodeled as part of this creative destruction promoted by public infrastructure supported by state and municipal governments.

In line with the representation of the phenomenon, iconic seafood restaurants such as Camichín (4) and the nightclub Bum Bum (5) were demolished to make way for condominium towers aimed at the vacation rental and second home market. Among the main implications, the volume of these buildings blocks wind circulation and creates large shaded areas that harm surrounding businesses and homes.

Another documented case is the remodeling of the Playa Norte restaurant (6), which was part of the boardwalk’s transformations in 2017. Although the restaurant has been preserved, its reconstruction has impacted the attraction of a larger number of tourists, with a decreasing presence of locals. This is part of new consumption dynamics triggered by the processes of creative destruction (Dlongolo et al., 2024) and gentrification of the area. Specifically, all these changes in buildings are related to what Ying (2022, p. 827) calls “managerial implications,” since they are managed with the logic of profit and gain as part of capital accumulation mechanisms.

Finally, the case of the emblematic restaurant El Pollo Loco (7) stands out, which closed its doors in 2011 to make way for the Oasis spa, a space that has since been heavily frequented by locals and tourists. The demolition of the restaurant generated controversy among Mazatlecos, as it had operated for approximately 30 years, becoming a city and Playa Norte landmark. The construction of the spa, linked to the expansion of Parque Martiniano Carvajal, was also criticized by residents due to its proximity to the sea.

Conclusions

In times of neoliberal entrepreneurship, Lefebvre’s thesis on the production of space becomes increasingly relevant, as it establishes that the capitalist system transforms space into an opportunity to dynamize mechanisms of capital accumulation, although it tends to elitize zones that were formerly spaces of citizen convergence and lived experiences (Baringo, 2013). These areas, disrupted by modernization and removal, are devoted to tourism activities and real estate speculation, resulting in processes of socio-spatial segregation that favor these zones to the detriment of popular residential areas where the working class resides.

The Playa Norte area constitutes a tangible expression of processes of neoliberalization and creative destruction (Fernández, 2024; Harvey, 2001; Schumpeter, 2010), evidenced essentially by the emergence of new economic units oriented towards tourism, while consumption spaces for the local population become increasingly limited. Furthermore, there is a growing configuration of high-rise buildings whose apartments are inaccessible to local residents due to their high prices, so they are promoted mainly as commodities for foreigners and outsiders who hoard them for real estate speculation or as second homes (Gutiérrez, 2020).

What has been exposed testifies that the area in question has not yet reached a consolidated process of neoliberalization and creative destruction but is in an initial stage of development seeking to establish an image of aesthetic appeal, as Minhui and Jigang (2015) propose in the case of the village of Xidi, a UNESCO World Heritage site in Anhui, China. It is worth noting that the ongoing changes suggest that these processes are far from stabilizing and that in the coming years, the area will likely face an intensification of these dynamics. As this progresses, the social and cultural fabric of Playa Norte may continue to change drastically, displacing local inhabitants and further limiting access to these traditional spaces for Mazatlán’s residents, contributing to an exclusionary city model with profound socio-spatial repercussions observable in the immediate environment and the city at large.

The implications of this phenomenon of creative destruction are part of a broader process along the Mazatlán coastline. However, unlike other zones, traditional ways of life still survive in Playa Norte, practiced by residents living near the study area, composed mainly of fishermen and workers in the tourism sector, creating a unique atmosphere in the city. Nevertheless, this nascent process of spatial neoliberalization and creative destruction of buildings is altering these traditional ways of life.

While this work focused on the transformation of the built materiality in the Playa Norte area and, peripherally, on its impacts on various elements, it opens a window of opportunity to further deepen the study of other creative destruction processes occurring in the zone, including changes in community organization, urban atmosphere, and cultural landscapes.

Bibliographic references

ASGARI, A; REZAEI, M. Y SARAEI, M. (2022). Identifying the advantage factors in Tourism of the historical texture of Yazd City with the approach of creative destruction. Geography and Development, 20(66), 283-306. https://doi.org/10.22111/J10.22111.2022.6727

BARINGO, D. (2013). La tesis de la producción del espacio en Henri Lefebvre y sus críticos: un enfoque a tomar en consideración. Quid 16, 3, 119-135. https://publicaciones.sociales.uba.ar/index.php/quid16/article/view/1133/1021

BOJÓRQUEZ, J. Y OSUNA, J. (2024). Neoliberalización y producción del espacio turístico: Alteraciones en la vida de los pescadores de Playa Norte, Mazatlán (México). Notas Históricas y Geográficas, (33), 410–439. https://doi.org/10.58210/nhyg567

BOJÓRQUEZ, J., OLIVARRÍA, C. Y SÁNCHEZ, E. (2023). Producción del espacio turístico vertical y tensiones sociales en Mazatlán (México). Ateliê Geográfico, 17(3), 45-64. https://doi.org/10.5216/ag.v17i3.75540

BRENNER, N. (2013). Tesis sobre la urbanización planetaria. Nueva Sociedad, 243, 38-66. https://static.nuso.org/media/articles/downloads/3915_1.pdf

BRENNER, N., PECK, J. Y THEODORE, N. (2015). Urbanismo neoliberal. La ciudad y el imperio de los mercados. En Observatorio Metropolitano de Madrid (ed.), El mercado contra la ciudad Sobre globalización, gentrificación y políticas urbanas (pp. 111-144). Traficantes de Sueños.

CHARNEY, I. (2024). Rezoning a top-notch CBD: The choreography of land-use regulation and creative destruction in Manhattan’s East Midtown. Urban Studies, 61(8), 1451-1467. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231208623

DA COSTA, T. (2023). ‘In time, every worker a capitalist’: Accumulation by legitimation and authoritarian neoliberalism in Thatcher’s Britain. Competition & Change, 27(5), 729-747. https://doi.org/10.1177/10245294231153028

DÍAZ, B., GUZON, O., POMPA, S., GRANO, M. Y ROLDÁN, B. (2021). Características de la actividad turística que utiliza al lobo marino de California como recurso no extractivo en la bahía de Mazatlán, Sinaloa, México. Revista Geográfica del Sur, 10(1), 31-51. https://doi.org/10.29393/GS10-2CABB50002

DLONGOLO, Z., IRVINE, P. Y MEMELA, S. (2024). Creative destruction and built environment heritage in Makhanda, South Africa. Modern Geográfia, 19(2), 47-70. https://doi.org/10.15170/MG.2024.19.02.04

ESPINO, L., SOTO, D. Y CALVARIO, A. (2023). Categorías teóricas de análisis espacial para comprender la dinámica del turismo en México. En Vilchis, A., Cruz Coria, E. y Marín, A. (coords.), Turismos del sur. Claves para reflexionar el turismo desde el pensamiento crítico (pp. 85-113). Universidad Autónoma de Quintana Roo - Universidad Autónoma de Occidente.

ESPINOZA, Y. (2018). Las vías de comunicación en la configuración del turismo como actividad económica en Mazatlán, Sinaloa, 1945-1970. En Frías, E., Román, A. y Chávez, J. (coords.), Sinaloa en el siglo XX. Aportes para su historia económica y social. Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa - Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur.

FERNÁNDEZ, J. (2024). Olvidos de Nueva York. Temporalidad y memoria en los espacios heterotópicos del tejido urbano. ZARCH, (22), 160-173. https://doi.org/10.26754/ojs_zarch/zarch.2024229898

GUTIÉRREZ, G. (2020). Producción del espacio urbano como destrucción creativa. Políticas, normativas e instrumentos de planificación urbana en la zona de Las Granadas de la alcaldía Miguel Hidalgo, Ciudad de México (2000-2018). [Tesis de maestría]. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. http://132.248.9.195/ptd2019/diciembre/0798932/Index.html

HARVEY, D. (2008). El neoliberalismo como destrucción creativa. Apuntes del CENES, 27(45), 1-24. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4795/479548752002.pdf

LEFEBVRE, H. (2013). La producción del espacio. Capitán Swing.

MINHUI, L. Y JIGANG, B. (2015). Tourism commodification in China’s Historic Towns and Villages: re-examining the creative destruction model. Tourism Tribune, 30(4), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-006.2015.04.002

OSUNA, J. Y CALONGE, F. (2022). Segregación socioespacial en el acceso a equipamientos de salud en Mazatlán, México. Cuaderno Urbano, 33(33), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.30972/crn.33336227

SÁNCHEZ BUELNA, J. (2022). La cultura de la pesca ribereña en el embarcadero Isla de la Piedra Gabriel Leyva, Mazatlán, Sinaloa. [Tesis de maestría]. El Colegio de San Luis. http://colsan.repositorioinstitucional.mx/jspui/handle/1013/1471

SANTAMARÍA, A. (2002). El nacimiento del turismo en Mazatlán (1923-1971). Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa.

SCHUMPETER, J. (2010). Capitalismo, socialismo y democracia. Página Indómita.

VALDEZ, M. (2006). Estrategia de educación ambiental para los pescadores ribereños de Playa Norte, municipio de Mazatlán, Sinaloa, México. [Tesis de Maestría]. Universidad de Guadalajara. http://repositorio.cucba.udg.mx:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/4694

YANG, X., XU, H. Y WALL, G. (2021). Creative destruction: the commodification of industrial heritage in Nanfeng Kiln District, China. En Lew, A. (ed.), Tourism Places in Asia: Destinations, Stakeholders and Consumption (pp. 54-77). Routledge

YING, E. (2022). Tourism as creative destruction: place making and resilience in rural areas. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 20(6), 827-841. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2022.2114359

ABBREVIATIONS, ACRONYMS, AND INITIALISMS

DENUE: Directorio Estadístico Nacional de Unidades Económicas.

INEGI: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía.

PIB: Producto Interno Bruto.

SIG: Sistema de Info

Jesús Bojórquez Luque

Sociologist from the Autonomous University of Sinaloa, Mexico (UABCS); Master's degree in Environmental and Natural Resources Economics from the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur, Mexico (UABCS), and PhD in History from the UAS. Professor and researcher at UABCS. Member of the National System of Researchers of the National Council for Humanities, Science and Technology, Mexico, level 1. His research interests include urban-territorial phenomena associated with tourism, public space, and social movements.

Julio Ernesto Osuna Covarrubias

Corresponding author. He holds a PhD in City, Territory, and Sustainability from the University of Guadalajara. He holds a Bachelor's degree in Architecture and a Master's degree in Architecture and Urban Planning from the Autonomous University of Sinaloa (UAS). He is Professor of the Bachelor's Degree in Architecture and Coordinator of the Master's Degree in Architecture and Territorial Development at the Faculty of Architecture and Design, UAS.

Autors

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

Tourism and creative destruction in Mazatlan, Mexico.

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

Figure 1. Location of Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico

Source: Own elaboration.

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

Figure 2. Location of Playa Norte

Source: Own elaboration.

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

Figure 3. Economic units in the Playa Norte area, 2010 and 2024

Source: Own elaboration, with data from DENUE.

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

Figure 4. Residential verticalization (2010-2024)

Source: Own elaboration based on field observation..

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

Project

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

Table 1. Transformation of the urban environment (2009-2024)

Fuente: Elaboración propia con base en fotografías históricas de Street View de Google Maps y archivo de los autores (26/10/24).

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)

The Playa Norte area (2009-2024)