Fuente: Autoría propia

Our homes in their investment portfolios.

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín

Nuestras viviendas en sus carteras de inversión.

Centralización socioespacial del stock de Airbnb en Medellín

Nossas casas em seus portfólios de investimento.

Centralização socioespacial das ações do Airbnb em Medellín

Nos logements dans vos portefeuilles d'investissement.

Centralisation sociospatiale du parc Airbnb à Medellín

Luis Daniel Santana Rivas

Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Sede Medellín

ldsantanar@unal.edu.co

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4855-5710

Alejandro Aristizábal Silva

Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Sede Medellín

aaristizabalsr@unal.edu.co

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5484-6106

How to cite this article:

Santana Rivas, L. D., Aristizábal Silva, A. (2025). Our homes in their investment portfolios. Socio-spatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín. Bitácora Urbano Territorial, 35(III): 285-298.

https://doi.org/10.15446/bitacora.v35n3.122521

Recibido: 01/09/2025

Aprobado: 25/11/2025

ISSN electrónico 2027-145X. ISSN impreso 0124-7913. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá

(3) 2025: 285-298

E-21_122521

Autor

Abstract

One of the constituent elements of the current touristification process in Medellín is an active short-term rental property market, which has expanded the spheres of reproduction of financial and real estate capital. This emergence, rapid in time and extensive in space, has occurred in two forms: the conversion of existing housing stock into tourist residences and the development of new ad hoc real estate products. Thus, the objective of this article is to investigate how centralized the ownership or management of homes transformed into assets traded on the Airbnb platform is—particularly the former—and how they are spatially distributed throughout Medellín. By identifying the number and type of properties associated with hosts, different agents, their market positions, and the spatial arrangement of their assets were identified. It is evident that, contrary to the imaginary of a decentralized market, monopolistic tendencies are present, suggesting that a large part of Airbnb’s stock corresponds to investment portfolios with selective spatial planning in the location of its assets, with a significant concrete and potential impact on the city’s social geography.

Keywords: real estate market, housing, tourism, speculation

Resumen

Uno de los elementos constitutivos del actual proceso turistificador que se da en Medellín es un activo mercado de inmuebles de rentas cortas, que ha ampliado las esferas de la reproducción de capitales financiero-inmobiliarios. Esa irrupción, rápida en términos temporales y extensiva espacialmente, se ha dado bajo dos modalidades: la conversión de inmuebles del parque habitacional en residencias turísticas y el desarrollo de nuevos productos inmobiliarios ah hoc. Así, el objetivo del artículo es indagar qué tan centralizada está la propiedad o gestión de viviendas transformadas en activos transados en la plataforma Airbnb —sobre todo del primer tipo— y cómo se distribuyen espacialmente en el territorio medellinense. A partir de la identificación de la cantidad y tipo de inmuebles asociados a los ‘hosts’ se identificaron diferentes agentes, sus posiciones en el mercado y la disposición espacial de sus activos. Se evidencia que, a diferencia del imaginario de un mercado descentralizado, se presentan tendencias monopólicas que sugieren que buena parte del stock de Airbnb corresponde a carteras de inversión con una planificación espacial selectiva en la localización de sus activos, con un gran impacto concreto y potencial en la geografía social de la ciudad.

Palabras clave: vivienda de alquiler, vivienda, turismo, mercado financiero.

Resumo

Um dos elementos constitutivos do atual processo de turistificação em Medellín é um ativo mercado imobiliário de aluguel de curta temporada, que expandiu as esferas de reprodução do capital financeiro e imobiliário. Essa emergência, rápida no tempo e extensa no espaço, ocorreu de duas formas: a conversão do parque habitacional existente em residências turísticas e o desenvolvimento de novos produtos imobiliários ad hoc. Assim, o objetivo deste artigo é investigar o quão centralizada é a propriedade ou a gestão de imóveis transformados em ativos negociados na plataforma Airbnb — em particular a primeira — e como eles se distribuem espacialmente por Medellín. Ao identificar o número e o tipo de imóveis associados aos anfitriões, foram identificados diferentes agentes, suas posições de mercado e a disposição espacial de seus ativos. É evidente que, ao contrário do imaginário de um mercado descentralizado, tendências monopolistas estão presentes, sugerindo que grande parte do estoque do Airbnb corresponde a carteiras de investimentos com planejamento espacial seletivo na localização de seus ativos, com significativo impacto concreto e potencial na geografia social da cidade.

Palavras-chave: mercado imobiliário, habitação, turismo, especulação

Résumé

L’un des éléments constitutifs du processus actuel de touristification à Medellín est un marché immobilier locatif actif à court terme, qui a élargi les sphères de reproduction du capital financier et immobilier. Cette émergence, rapide dans le temps et étendue dans l’espace, s’est manifestée sous deux formes : la conversion du parc immobilier existant en résidences touristiques et le développement de nouveaux produits immobiliers ad hoc. Cet article vise donc à analyser le degré de centralisation de la propriété ou de la gestion des logements transformés en actifs négociés sur la plateforme Airbnb, en particulier dans le premier cas, et leur répartition spatiale à Medellín. En identifiant le nombre et le type de biens immobiliers associés aux hôtes, les différents agents, leur positionnement sur le marché et la répartition spatiale de leurs actifs ont été identifiés. Il apparaît clairement que, contrairement à l’imaginaire d’un marché décentralisé, des tendances monopolistiques sont présentes, suggérant qu’une grande partie du parc immobilier d’Airbnb correspond à des portefeuilles d’investissement avec une planification spatiale sélective de la localisation de ses actifs, avec un impact concret et potentiel significatif sur la géographie sociale de la ville.

Mots-clés : marché immobilier, logement, tourisme, spéculation

Introduction

In less than a decade, Medellín has transformed and established itself as a touristic city. After being a destination predominantly visited by domestic tourists until the first decade of the 21st century, it is now visited mainly by foreigners, who represent 72% of visitors, with an estimated 1.8 million (Secretariat of Tourism, 2025) in 2025. In terms of accommodation, these growing numbers of tourists stay in hotels and hostels or in what the district administration calls tourist housing, making it difficult to establish the absolute number of guests, especially in the latter category.

Since 2021, the Mayor's Office of Medellín has reported data on accommodation in 'tourist housing', which went from 4,219 units in that year to 17,138, 33,973, 39,533, and 36,417 in 2022, 2023, 2024, and 2025, respectively (Secretariat of Tourism, 2025). Although occupancy in July 2025 was 49% compared to 70% for hotels and hostels, the owners of these homes, who are registered as tourism service providers alongside shops, restaurants, and other activities in the sector, accounted for 70% of the total in 2025 (Ministry of Tourism, 2025).

Although the figures are by no means definitive in terms of reflecting the real importance of this new real estate market, they do confirm the growing importance of what will be referred to here as 'short-term rental housing', given that what prevails in its social circulation is not its use value associated with living in it, but rather its exchange value in recurrent movement, which produces short-term income and financial liquidity. This importance is not only defined by the dynamics inherent in tourism but is also key to understanding the current urban housing crisis.

It is therefore essential to understand the configuration, development, and changes in the production, circulation, and consumption of short-term rental housing involved in both tourism activities and new ways of living, such as digital nomadism and international retirement migration. Although the public debate on Airbnb in Medellín has focused on gentrification, rising rental prices for residents, and conflicts between tourists and locals, little is known about the social agents involved in this debate, as well as their strategies for social and spatial impact on the city.

For this reason, regulatory proposals such as those put forward by the current administration, which simply involve registering properties and running advertising campaigns —in conjunction with Airbnb— to limit the use of these homes for sex tourism, or those that will surely result from making an inventory of them for the new revision of the land use plan, are aimed at facilitating the development of this new financial-real estate market (Brossat, 2019), viewing them essentially as just another phenomenon of 'land occupation'.

A first step toward generating a deep understanding of the configuration and development of short-term rental properties in Medellín involves scrutinizing the few and nebulous data that exist to identify the urban agents involved. Consequently, the objective of this article is to investigate how centralized the ownership or management of housing transformed into assets traded on the Airbnb platform is —especially the former—, and how they are spatially distributed in the Medellín area.

The starting point is the hypothesis that the development and conversion of housing into short-term rental properties, which circulate mainly on the Airbnb digital platform, is a cutting-edge field of real estate and housing financialization in the Medellín context and that, although it is far from the monopolistic tendencies exercised by large global real estate asset management companies, in tourist metropolises, it shows clear signs of moving towards that horizon. Therefore, both citizen and social responses and the formulation of housing policies as a fundamental social right must be supported by a broad understanding of the characteristics of this market in Medellín.

Methodologically, the challenge of financial and real estate opacity in this market emerges, which is common in other tourist contexts but more serious in Medellín due to the structural existence of illicit capital accumulation. In response to this, the unique identification number assigned by Airbnb on the AllTheRooms website was explored. This type of input is generated for consultation by investors in the sector, including platforms, and therefore it is not possible to explore the legal nature of each one in detail. Based on the number of assets associated with the same identifier, they were classified quantitatively and qualitatively into several categories of agents. Subsequently, the spatial distribution of these different types was identified based on their importance in the market, which ultimately allows profiles to be identified according to their impact on the social geography of the city.

Our Homes and Cities in Their Investment Portfolios

Much of the theoretical reflection on the capitalist financialization of housing has emphasized first understanding how a spatially fixed asset is transformed into a tradable security in capital markets, with consequences in terms of cheaper credit, mortgage debt securitization, and the impact of financial crises in terms of housing expropriation. Subsequently, authors and authors have delved into the implications of real estate production and circulation, highlighting the role of development and income investment funds, which implies the imposition of strictly financial and capital market logic on this branch of accumulation (Carroza Athens, 2022; Vergara-Perucich, 2025).

Recently, the emergence of platforms for the circulation of short-term rental housing has pointed to a new area of this financialization of housing. However, what happens to housing prices because of the dynamics of short-term rentals has structural elements that are constitutive of real estate markets in general. Understanding the configuration of a short-term rental housing market and its urban implications therefore involves establishing the structural elements of capitalist real estate development and the contingencies that derive from financialization in a new niche for the reproduction of financial and real estate capital.

In this sense, it is possible to point out that the existence of this new market has an impact on what Jaramillo (2009) calls general and cyclical movements in housing prices; that is, on the trend patterns of land price increases that subsequently imply increases in the prices of built space and medium- and short-term fluctuations, respectively. In the first case, the short-term rental market accelerates the monopolization of land and real estate assets, while in the second, tourism cycles impact the dynamics of housing prices.

It also means that the institution in different urban and rural areas, like any new capitalist market, involves processes of primitive accumulation that can be internal or external (Harvey, 2018; Rolnik, 2017), within which gentrification is nothing more than a process limited to certain areas of cities. The modalities of enclosure of the housing market can affect areas such as the rental segment, the production of social housing, and even self-construction.

Finally, a third structural impact will result from the transformation of the traditional roles of certain types of urban speculators, also described by Jaramillo (2009). The development of a niche market for housing speculation in conjunction with the financialization of capitalism implies new forms of social agency in the dynamics of housing price movements.

One of the main developments introduced by the production and circulation of short-term rental housing in a context of financial capitalism is described by Christophers (2025) in Our Lives in Their Investment Portfolios: How Asset Managers Rule the World. The circulation of non-residential real estate, housing, and territorial infrastructure currently depends on asset management companies that administer these assets under a logic of maximizing returns and financial liquidity, which are owned by private and institutional investors. This management involves minimizing maintenance costs, amplifying the difference between the acquisition and sale costs of the assets, and facilitating their rapid sale if necessary (Christophers, 2025).

Currently, both global asset management companies and others with a national, regional, or metropolitan scope are often behind part of the stock circulating on platforms such as Airbnb. Of course, the levels of opacity are notable, and it is not always feasible to establish the weight of large management companies in the world's major tourist metropolises. They act in metropolitan contexts as 'inductive macro-speculators', a category adapted from that originally proposed by Jaramillo (2009) insofar as their transactions and housing asset management patterns affect price movements in different cities, and within them in large or highly valued areas; also in that they manage not only housing but also infrastructure, enabling them to capture different forms of differential rents.

Although these asset management companies are at the top of the tourism market hierarchy, in contexts such as Colombia, many managers are traditional 'inductive speculators', generally operating as developers of new short-term rental real estate developments, as well as in the financial management of these same properties on platforms such as Airbnb. The capture and appropriation of land rents are combined with the financial surpluses from the management of assets owned by various types of institutional or individual investors.

In the realm of passive speculators, conceived by Jaramillo (2009) as agents who simply participate in the circulation of housing in the market —sales, rentals— a new urban agent emerges: ‘passive short-term rental speculators' who manage short-term rental housing on a medium scale in terms of volume, but who, in addition to facilitating management within the real estate platform of different owners, sometimes act as rental managers providing cleaning, refurbishment, and maintenance services for the properties. As Santana (2024) also points out, the existence of Airbnb has led to the proliferation of a new type of housing speculator who does not benefit from increases in the value of the housing they normally use —Jaramillo (2009) calls this proto-speculation— nor from specialized real estate brokerage companies —passive speculation—. It is a 'micro-property speculator' who benefits from rents and, in this case, from increases in the contract rent for short-term rentals of their second or third home —income that supplements their regular income.

Each of these types of agents could have different impacts on urban geography. Macro-speculators and inductive speculators would tend to concentrate on assets that generate monopoly rents —those that have unique location conditions or socially valued attributes that are likely to fetch a monopoly price because of those very conditions— as these are the ones that make it easier to guarantee greater profitability and liquidity. Passive speculators tend to develop strategies to focus or diversify their areas of operation based on their knowledge of the market, while micro-speculators capture differential rents in different, less attractive locations.

In this sense, the consolidation of these trends generates pressure on almost all segments of the housing market, whether new, rental, or across different social classes. Although less consolidated working-class neighborhoods are unattractive, informal areas with better accessibility to tourist circuits are also entering the Airbnb housing circulation process. It could be said that the ‘Airbnbification’ of housing is a process that affects speculative movements in structural and cyclical prices.

Methodological Strategy

Based on a selection of data by commune and district and anonymized information from the AllTheRooms website, a database was created with variables such as location, host (with a unique identifier), type of accommodation, and capacity (see Table 1). Three processes were carried out using this spatial database.

First, more than 7,000 real estate assets circulating on Airbnb in July 2024 were georeferenced, identifying how they are distributed in relative terms, i.e., based on their density in Medellín's urban and rural geography. The spatial distributions of different types of accommodation were also identified in five categories that group together more than fifteen strictly building-related designations and where they are located according to the land use assigned in the land use plan.

Secondly, the identification and classification of Airbnb hosts based on the number of assets they manage or own within the jurisdiction of the district of Medellín; the following ranges were identified: 1, 2, 3 and 4, 5 to 9, 10 to 19, 20 to 49, and more than 50. As mentioned, it is not possible to establish whether the host is the owner or simply the manager or administrator, nor is it possible to obtain detailed information on whether they are a natural or legal person. For this reason, reference will be made to owner-managers, especially those associated with two or more assets.

Thirdly, depending on whether they are small, medium, or large owner-managers of assets, asset distribution maps were drawn up to identify whether there are differential location patterns depending on the type of urban and financial-real estate agent. This makes it easier to explore the socio-spatial implications of the centralization of assets on Airbnb in Medellín.

Airbnb, a new financial-real estate monopoly? Evidence in Medellín

Although the first widely circulated map showing the distribution of Airbnb accommodations in Medellín appeared in an article in the newspaper El Colombiano (2023) with data extracted from the AllTheRooms website, exploratory analyses of and their spatiotemporal variation are still necessary. Although the data presented is from July 2024, the consolidation of touristification means that it is still valid in terms of trends as of September 2025. Before identifying the types of agents involved in Airbnb, some exploratory elements on the spatial distribution of real estate assets at that time are provided.

The Airbnb Phenomenon in Medellín

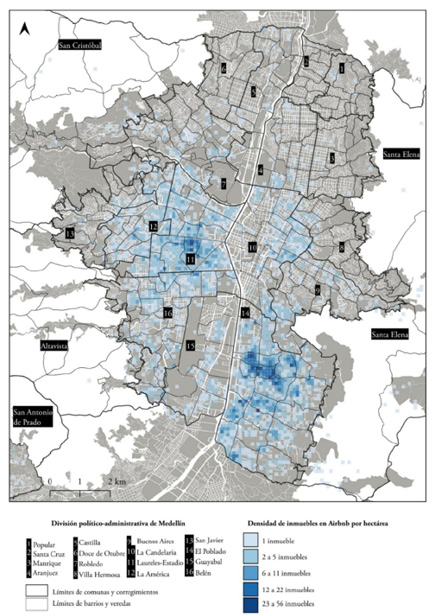

The Airbnb map for the district of Medellín alone in 2024 showed more than 7,000 housing units of various types. Although the platform has been operating since the early 2010s and it was initially thought that the properties included in its database were located in the city's traditional tourist and hotel sectors, by 2024 there is a considerable dispersion of units in both rural areas —mainly in the township of Santa Elena— and urban areas —in the west, eastern pericenter, and southeast— with only the density of properties varying, which is of course higher in neighborhoods close to tourist attractions (see Figure 1).

There are therefore two distribution patterns: in the communes of Laureles-Estadio and El Poblado, there is the highest density of units, ranging from 11 to 56 properties per hectare, in the form of corridors such as the one comprising Carrera 70 in the west of the city at Laureles-Estadio, Calle 10 in El Poblado, and east of Avenida Oriental in the central area; the second consists of less dense but very scattered clusters in middle-class districts such as Belén and Robledo, but also in working-class districts such as Villa Hermosa, Manrique, and Aranjuez, and even Popular on the northeastern outskirts (see Figure 1).

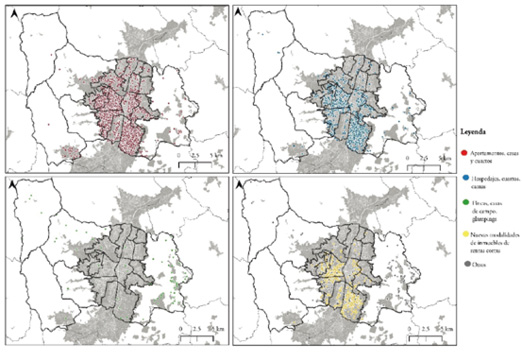

The platform distinguishes between more than 15 types of urban and rural accommodation, based on the type of building, size, etc., which are grouped into four broad categories. The most prevalent and present in all neighborhoods of Medellín are those with the greatest impact on urban housing: houses, apartments, and rooms (see Figure 2). Accommodations associated with hostels and new short-term rental buildings represent a significant percentage but are more concentrated in tourist districts (see Figure 2). Finally, units in rural villages have an impact on three of Medellín's five districts: Santa Elena, San Cristóbal, and Palmitas, but mainly the former (see Figure 2).

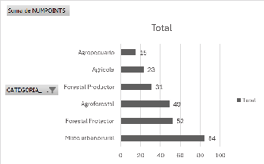

Sixty-seven percent of accommodations are concentrated in urban areas with high and low functional mix, while in rural areas, 33% are located in mixed urban-rural areas —in the suburban category— and 20% in protected forest areas (see Figure 3). This shows that in urban areas, accommodations impact areas that are well served by services and businesses, while in rural areas they jeopardize environmental conservation and agricultural production, mainly of the peasant type.

A First Approach to Urban Agents in Medellín's Airbnb

At first glance, the extremely high socio-spatial dispersion of Airbnb properties would suggest, as in the rhetoric of platform companies, that various social agents from different classes benefit from these rents. However, when filtering the unique identifiers in more than 7,000 units in Medellín, the evidence suggests otherwise.

Seventy-two percent of owners or managers have only one property, controlling only 30.7% of the total units listed on Airbnb. If we add those who manage two properties, the cumulative total rises to 40.4% of all units, even though they represent 83% of owners (see Table 2). Units with 3 to 9 units account for 26% of the accommodation property stock and only 13.6% of owners or managers (see Table 2).

Finally, it should be noted that large owners or managers have 10 or more units, corresponding to 1,858 units or 47% of the total (see Table 2). In other words, this last group accounts for the largest proportion of units listed on Airbnb in the district of Medellín. Not only is there no more uniform distribution, but a small number of owners/managers (8%) own most units rented on the platform.

The existence of both micro-property speculators, who may have between one and two registered properties, and companies that play a role similar to that of passive speculators, with between three and 19 properties, is confirmed. From 20 properties onwards, the complexity of simultaneously managing houses, apartments, rooms, farms, etc., is such that the agents involved may be inductive speculators—agents with multiple real estate investments— or macro financial-real estate speculators with the capacity to facilitate the continuous operation of rent extraction.

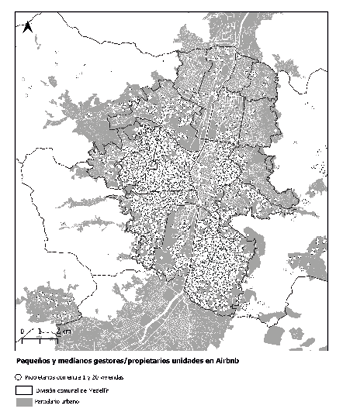

This dual division between small and large speculators has at least two impacts on the urban geography of Medellín. The former, potentially considered micro-property speculators and small and medium-sized passive speculators, have facilitated the conversion of properties into tourist rooms in all the communes and districts of Medellín, although with a significant difference between the north and south. Neighborhoods that originated from social housing policies, popular self-construction, and middle- and upper-class policies have properties available to domestic and foreign tourists (see Figure 4).

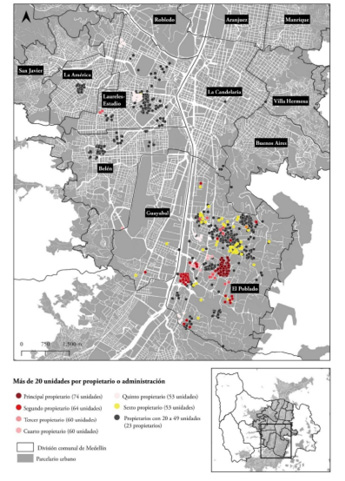

Large-scale speculators may include inductive and macro financial-real estate speculators, since the spatial distribution of their units reveals a high degree of selectivity. The units owned and managed by large property owners reveal that they tend to cluster in the most socially prestigious areas: the sector known as the "golden mile," the corridor of 10th Street and the upper transversal in El Poblado; in the west of the city, the Carrera 70 corridor stands out, but there are also concentrations in neighborhoods in the Belén and La América districts, near district 13, San Javier (see Figure 5).

This selectivity implies a powerful monopolization of real estate assets in these areas, which share common characteristics: they are upper-class neighborhoods and, to a lesser extent, middle-class neighborhoods; they are highly centralized in terms of tourist activities, commerce, restaurants, bars, and nightclubs; they are undergoing significant building verticalization processes as a result of property-by-property urban renewal processes; they are contiguous to what, in terms of local land use policy, are called high-mix corridors, which include motels in addition to commerce and restaurants.

In these areas valued by tourism, which have become tourist destinations, a high volume of buildings for short-term rentals in different modalities —coliving, themed hostels (influencers and YouTubers, for example), studio apartments, etc.— have been concentrated for less than five years. These buildings tend to have recurring architectural features: tall buildings, green facades, use of bright colors, and even murals as decorative elements. It is difficult to identify how many units in the database are already part of this type of building and whether this explains the spatial concentrations, in addition to the fact that other platforms such as Vrbo and Booking are not being considered, knowing that a developer can be simultaneously on one or two of these applications.

It is possible that the same development companies manage investor quotas and the circulation of properties on platforms such as Airbnb, functioning as asset management companies, in this case for real estate. However, the name registered in the database does not allow for the identification of specific information about these companies.

Final reflections

The analytical exercise reveals a pressing centralization of properties listed on the Airbnb platform, with small owners or managers (those with one or at most two associated units) accounting for only 40.4% of the total assets. Medium and large specialized agents control 47%, almost half of the accommodation market. This is consistent with other research on the monopolistic tendencies of agents participating in Airbnb in other tourist cities around the world (Brossat, 2019; García-Lopez et al., 2021; González, 2023; Lerena-Rongvaux and Orozco, 2025).

Although there is no detailed information on the type of owner-managers, they operate, at least from the point of view of their location and accommodation concentration strategies, as asset management companies. Although there is no evidence of the presence of major global companies, it is possible that local, national, or even transnational firms of this type exist. This is a point that should be explored further as outcroppings, visible spaces within a hidden structure, emerge.

One way is to track the companies and investors that are venturing into the active market for short-term rental properties in Medellín, which could be the main management companies for this type of asset on platforms such as Airbnb. For now, what the analysis suggests is that they play a fundamental role in capturing tourist monopoly rents by concentrating the largest amount of assets in socially highly valued areas, close to tourist circuits and with high functional centrality.

The impact of this type of short-term rental property on future real estate or tourism crises still needs to be studied. Devaluation processes could be mitigated by using these properties as primary residences, with a decline in housing standards for those who must resort to the rental market.

However, a less centralized market would not be ideal either. With 40% of units belonging to micro-speculators, all segments of the urban housing market are impacted, even more so than those assets managed by medium and large managers-owners. This is one of the structural elements associated with the general price movements currently affecting Medellín (Santana, 2024).

Whether it is our homes in their investment portfolios or a growing layer of micro-property speculators seeking to increase their income or secure a more generous pension, there are different types of fuels feeding the current housing crisis in Medellín. And they are outside the agenda of social movements, urban policies —now focused on building an artificial sea— the process of reviewing the land use plan, and the limited role of local and national government in realizing the right to decent housing.

References

BROSSAT, I. (2019). Airbnb: la ciudad uberizada. (S. Ruiz Elizalde, Trad.; 1.a ed.). Katakrak. (Trabajo original publicado en 2018). https://katakrak.net/sites/default/files/airbnb._la_ciudad_uberizada_web.pdf

CARROZA ATHENS, N. (2022). Variedades de financiarización de la vivienda en América Latina: un análisis comparado entre Chile y Venezuela (2000-2015). Revista INVI, 37(105), 98–123. https://doi.org/10.5354/0718-8358.2022.63800

CHRISTOPHERS, B. (2025). Nuestras vidas en sus carteras de inversión. Cómo los gestores de activos dominan el mundo. (P. Martín Ponz, Trad.; 1.a ed.). Traficantes de Sueños. (Trabajo original publicado en 2023). https://traficantes.net/sites/default/files/pdfs/PC_33_Nuestras%20vidas_web_1.pdf

GARCIA-LÓPEZ, M. À., JOFRE-MONSENY, J., MARTÍNEZ-MAZZA, R., & SEGÚ, M. (2020). Do short-term rental platforms affect housing markets? Evidence from Airbnb in Barcelona. Journal of Urban Economics, 119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2020.103278

GONZÁLEZ, R. (2023). Los oferentes de Airbnb en la financiarización de la vivienda en las áreas centrales de la Ciudad de México, URBS. Revista de Estudios Urbanos y Ciencias Sociales, 13(1): 101-107. https://urbs.xoc.uam.mx/index.php/urbs/article/view/41/39

JARAMILLO, S. (2009). Hacia una teoría de la renta del suelo urbano (2.ª ed.). Universidad de los Andes.

HARVEY, D. (2018). Los senderos del mundo. (J. Madariaga. Trad.; 1.a ed.). Akal. (Trabajo original publicado en 2016).

LERENA-RONGVAUX, N. Y OROZCO, H. (2025). Alquileres a corto plazo como nuevos patrones de acumulación territorial. Airbnb en Buenos Aires y Santiago de Chile. Scripta Nova. Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales, 29(2), 141-176. https://doi.org/10.1344/sn2025.29.46737

ROLNIK, R. (2017). La guerra de los lugares. La colonización de la tierra y la vivienda en la era de las finanzas (1.ª ed.).. LOM Ediciones.

SANTANA RIVAS, L. D. (2024). Los precios de la vivienda en Medellín: ¿crisis urbana coyuntural o estructural?. Bitácora Urbano Territorial, 34(2), 228–242. https://doi.org/10.15446/bitacora.v34n2.109348

SECRETARIA DE TURISMO. (2025). Sistema de Inteligencia Turística (SIT). https://www.turismomde.gov.co/

ZAPATA, A. (2023, SEPTIEMBRE 19). Avanza el proyecto de ley que permitirá que cualquier vivienda residencial sea de uso turístico: así lo puede afectar. El Colombiano, https://www.elcolombiano.com/negocios/proyecto-de-ley-205-de-2022-busca-reformar-regimen-de-propiedad-horizontal-en-colombia-para-que-turismo-sea-permitido-en-cualquier-inmueble-residenci-GH22432602

VERGARA-PERUCICH, F. (2025). ¿Financiarización o financierización? Precisiones etimológicas para un concepto crítico en la literatura de estudios urbanos en Hispanoamérica. Revista EURE - Revista De Estudios Urbano Regionales, 51(154), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.7764/EURE.51.154.11

Luis Daniel Santana Rivas

Associate Professor at the School of Habitat. Geographer and Master in Geography from the National University of Colombia, Bogotá, and Doctor in Geography from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.

Alejandro Aristizábal Silva

Political scientist from the National University of Colombia, master’s degree in Socio-Spatial Studies from the University of Antioquia. Member of the Center for Critical Political Thought and the GET Territorial Studies Research Group.

Autors

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín

Our homes in their investment portfolios.

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín

The objective of this article is to investigate how centralized the ownership or management of housing transformed into assets traded on the Airbnb platform is —especially the former—, and how they are spatially distributed in the Medellín area.

The starting point is the hypothesis that the development and conversion of housing into short-term rental properties, which circulate mainly on the Airbnb digital platform, is a cutting-edge field of real estate and housing financialization in the Medellín context

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín

Table 1. Variables and search method

Source: Own elaboration.

|

Variables |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Name |

This is the name used to identify the accommodation, property, or unit offered |

|

Host |

Person or manager responsible for the accommodation, in charge of its administration, contact, and guest services |

|

Longitude |

Geographic coordinate indicating the position of the accommodation in an east-west direction on the map |

|

Latitude |

Geographic coordinate indicating the position of the accommodation in a north-south direction |

|

Maximum capacity |

Total number of people that the accommodation can accommodate according to its characteristics and occupancy rules |

|

Sleeps |

Number of rooms in the accommodation |

|

Arrangement type |

The way in which the spaces are organized to accommodate guests (e.g., private room, shared room, entire apartment, studio, etc.) |

|

Property type |

Classification of the property according to its physical nature or use: house, apartment, cabin, farm, loft, among others |

|

Host link |

URL or web address that directs to the host's profile. |

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín

Figure 1. Density of short-term rentals on Airbnb in 2024

Source: Own elaboration.

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín

Figure 2. Main types of accommodation on Airbnb in 2024

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 3. Number of Airbnbs by urban and rural land use POT 2014

Source: Own elaboration.

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín

Table 2. Distribution of units and owner-managers on Airbnb in Medellín, 2024

Source: Own elaboration.

|

Range |

Owners |

Units |

Percentage of owners (%) |

Percentage of units (%) |

Cumulative percentage of units |

|

1 |

2188 |

2188 |

72,0 |

30,7 |

30,7 |

|

2 |

347 |

694 |

11,4 |

9,7 |

40,4 |

|

3 to 4 |

245 |

831 |

8,1 |

11,7 |

52,1 |

|

5 to 9 |

167 |

1063 |

5,5 |

14,9 |

67,0 |

|

10 to 19 |

61 |

803 |

2,0 |

11,3 |

78,2 |

|

20 to 49 |

23 |

640 |

0,8 |

9,0 |

87,2 |

|

Over 50 |

7 |

415 |

0,2 |

5,8 |

93,0 |

|

No data |

496 |

7,0 |

100,0 |

||

|

Total |

3038 |

7130 |

100 |

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín

Figure 4. Small and medium-sized owners-managers of units on Airbnb in Medellín, 2024

Source: Own elaboration.

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín

Figure 5. Large owners-managers of units on Airbnb in Medellín, 2024

Source: Own elaboration.

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín

Sociospatial centralization of Airbnb stock in Medellín