Fuente: Autoría propia

Housing, Labor, and Social Reproduction in Popular Urbanization.

City-Making and Sustaining Life[1]

Vivienda, trabajo y reproducción social en la urbanización popular.

Hacer ciudad y sostener la vida

Habitação, trabalho e reprodução social na urbanização popular.

Fazer cidade, sustentar a vida

Logement, travail et reproduction sociale dans l’urbanisation populaire.

Produire la ville, soutenir la vie

María del Pilar Isla

FAUD (UNMdP) – CONICET

mariadelpilarisla@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-2197-9145

How to cite this article:

Isla, M. P. (2025). Housing, Labor, and Social Reproduction in Popular Urbanization. City-Making and Sustaining Life. Bitácora Urbano Territorial, 35(III): 299-311.

https://doi.org/10.15446/bitacora.v35n3.122529

Recibido: 01/09/2025

Aprobado: 11/12/2025

ISSN electrónico 2027-145X. ISSN impreso 0124-7913. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá

[1] This work is part of ongoing doctoral research funded by CONICET.

(3) 2025: 299-311

E_22_122529

Autor

Abstract

This article argues that the housing question in Latin America cannot be reduced to a housing deficit or technical parameters, but must instead be understood in its relationship to work and social reproduction. The theoretical approach draws on three fields: the Marxist tradition on housing and the urban question, feminist contributions on social reproduction and popular economies, and Latin American debates on popular urbanization. The analysis is organized around the central category of housing improvement strategies, addressing three analytical dimensions: the integration of productive and reproductive activities within the home; community networks and territorial disputes, and the relationship with public policies aimed at improving habitat conditions. The methodological strategy is qualitative and combines conceptual and empirical tools through the study of three housing trajectories in two low-income neighborhoods of Mar del Plata (Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina). The findings allow us to move beyond the notion of informality and provide evidence that processes of popular urbanization are practices of space–time production in which the reproduction of life requires the everyday restoration of the material conditions of habitat.

Keywords: housing, labour, city, popular urbanization, social reproduction

Resumen

En este artículo se argumenta que la cuestión habitacional en América Latina no puede reducirse al déficit de vivienda ni a parámetros técnicos, sino que debe comprenderse en su vínculo con el trabajo y la reproducción social. El enfoque teórico se apoya en tres campos: la tradición marxista sobre vivienda y cuestión urbana, los aportes feministas sobre reproducción social y economías populares y los debates latinoamericanos en torno a la urbanización popular. El análisis se organiza en torno a la categoría central de estrategias de mejora habitacional, abordando tres dimensiones analíticas: la integración entre actividades productivas y reproductivas en la vivienda; las redes comunitarias y disputas territoriales; y el vínculo con políticas públicas de mejoramiento del hábitat. La estrategia metodológica es cualitativa y consiste en combinar herramientas conceptuales y empíricas a través del estudio de tres trayectorias habitacionales en dos barrios populares de Mar del Plata (Provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina). Los resultados obtenidos permiten avanzar más allá de la noción de informalidad y aportan evidencia para sostener que los procesos de urbanización popular son prácticas de producción del espacio-tiempo donde la reproducción de la vida demanda una reposición cotidiana de las condiciones materiales del hábitat.

Palabras clave: vivienda, trabajo, ciudad, urbanización popular, reproducción social

Resumo

Este artigo sustenta que a questão habitacional na América Latina não pode ser reduzida ao déficit de moradia nem a parâmetros técnicos, mas deve ser compreendida em sua relação com o trabalho e a reprodução social. A abordagem teórica apoia-se em três campos: a tradição marxista sobre moradia e questão urbana, as contribuições feministas sobre reprodução social e economias populares, e os debates latino-americanos em torno da urbanização popular. A análise organiza-se em torno da categoria central de estratégias de melhoria habitacional, abordando três dimensões analíticas: a integração entre atividades produtivas e reprodutivas na moradia; as redes comunitárias e disputas territoriais, e a relação com políticas públicas de melhoria do habitat. A estratégia metodológica é qualitativa e consiste em combinar ferramentas conceituais e empíricas por meio do estudo de três trajetórias habitacionais em dois bairros populares de Mar del Plata (Província de Buenos Aires, Argentina). Os resultados obtidos permitem avançar para além da noção de informalidade e oferecem evidências de que os processos de urbanização popular são práticas de produção do espaço-tempo nas quais a reprodução da vida demanda uma reposição cotidiana das condições materiais do habitat.

Palavras-chave: moradia, trabalho, cidade, urbanização popular, reprodução social

Résumé

Cet article soutient que la question du logement en Amérique latine ne peut être réduite ni au déficit de logement ni à des paramètres techniques, mais qu’elle doit être comprise dans son lien avec le travail et la reproduction sociale. L’approche théorique s’appuie sur trois champs : la tradition marxiste portant sur le logement et la question urbaine, les apports féministes sur la reproduction sociale et les économies populaires, ainsi que les débats latino-américains autour de l’urbanisation populaire. L’analyse s’organise autour de la catégorie centrale des stratégies d’amélioration de l’habitat, en abordant trois dimensions analytiques : l’intégration entre activités productives et reproductives au sein du logement ; les réseaux communautaires et les conflits territoriaux, et le lien avec les politiques publiques de transformation de l’habitat. La stratégie méthodologique est qualitative et consiste à combiner des outils conceptuels et empiriques à partir de l’étude de trois trajectoires résidentielles dans deux quartiers populaires de Mar del Plata (Province de Buenos Aires, Argentine). Les résultats obtenus permettent d’aller au-delà de la notion d’informalité et montrent que les processus d’urbanisation populaire sont des pratiques de production de l’espace-temps dans lesquelles la reproduction de la vie exige une reconstitution quotidienne des conditions matérielles de l’habitat.

Mots-clés : logement, travail, ville, urbanisation populaire, reproduction sociale

Introduction

The housing issue, historically linked to the so-called 'social question', became an 'urban question' in a process of disciplinary specialization which, as Topalov (1990a) warns, tended to separate the analysis of urban space from the social structures that produce it. This shift towards a more technical and sectoral approach, reinforced by the institutionalization of urban planning and policy, has contributed to a fragmented approach to complex phenomena such as access to housing and the social production of habitat, diluting their political dimension and their links to the world of work and social reproduction. The dominant views of the urban planning discipline tend towards statist, technocratic, and mercantilist conceptions of space (Brenner, 2009), becoming trapped in dualistic views of the city (formal/informal, legal/illegal).

In Latin America, this dualism is particularly problematic, since the difficulty in accessing urbanized land, far from being an anomaly, is a widespread and persistent phenomenon in our cities (Jaramillo, 2021). The regulations that govern and restrict private property consider both those who cannot access property titles and those who, in the urbanization process, fail to comply with building regulations to be illegal/informal (Clichevsky, 2000). At the same time, however, it is the lack of state regulation that allows for the increase in speculative practices that make access to serviced land increasingly difficult and increase levels of informality. According to Smolka (as cited in Del Río, Gonzalez, 2019), Latin American cities are characterized by a high proportion of land with little or no coverage of services, facilities, and infrastructure, and high land prices in relation to their levels of income and development. This allows landowners to appropriate a differential rent resulting from the relative scarcity of urban land. It is insufficient to reduce the ways of living of urban majorities to the dominant conceptualizations that label them as ‘illegal’ or ‘informal’ because, on the one hand, there are numerous exceptions and transgressions of urban regulatory codes by real estate developments in collusion with local governments and, on the other hand, circumventing certain ambiguities is part of implicit social pacts that enable the existence of these sectors (The Urban Popular Economy Collective, 2022). Consequently, the notion of popular urbanization is adopted, understood as the practices carried out by the inhabitants of impoverished neighborhoods themselves in order to remedy, replace, and question the dispossession of public infrastructure (Gago, 2019). The premise guiding the analysis argues that the persistent housing problem in Latin America cannot be fully understood without considering its articulation with forms of work and processes of social reproduction. This allows us to shift the analysis from a focus exclusively on the housing deficit or the physical conditions of housing to an interpretation that understands it as part of a network of domestic, productive, and community strategies that sustain life. Thus, investigating this connection is key to revealing how families combine resources, spaces, and time devoted to both income generation and caregiving tasks and how these practices are intertwined with disputes over popular urbanization. From this perspective, the article argues that the housing improvement strategies developed in popular neighborhoods are based on productive-reproductive practices, and their analysis allows for a more complete understanding of popular urbanization, going beyond the deficit view and the formal/informal dualism.

In this sense, the theoretical coordinates that guide the analysis are constructed from the dialogue between three perspectives, which offer complementary conceptual tools for understanding the interweaving of housing, work, and social reproduction in popular urbanization. First, we return to the pioneering contributions of urban Marxism, which allow us to situate housing in relation to the processes of capital accumulation and the reproduction of the workforce. Next, the contributions of feminism and popular economies are incorporated, which have highlighted domestic and care work as a structural component for the reproduction of capital and have questioned the division between the productive and the reproductive by highlighting their interdependence, while emphasizing the diversity and centrality of productive strategies not exclusively subordinate to formal employment. Finally, Latin American debates on popular urbanization are revisited, particularly those related to strategies of self-production and self-management of housing and their relationship to public housing policies.

Theoretical Perspective

Housing and Urban Issues in the Classics

This section recovers the contributions of authors considered classics in urban studies, whose works —linked to the Marxist critical tradition— laid the foundations for understanding housing and the city as inseparable dimensions of social relations of production and the contradictions inherent in capitalism.

First, Friedrich Engels' Contribution to the Housing Question (2006 [1873]) is undoubtedly one of the first theoretical works to explicitly link material living conditions —and housing in particular— with the social organization of labor. It emerged from a series of articles in which he discussed with some of his contemporaries how to solve the housing problem of the proletarian sectors of the time. Engels did not approach the housing issue as a sectoral or merely technical problem, but as a structural manifestation of the contradictions of capitalism, inseparable from the logic of exploitation that organizes the production and reproduction of the workforce. In this sense, the text offers early conceptual tools, critiques of artifactual views of housing, and links the working conditions of what we would today call the working classes with specific urban dynamics.

Some of these concerns were taken up a century later by the French philosopher Henri Lefebvre, who advanced a Marxist theory of (social) space—and of the social relations that are produced in and by it. Thus, in The Production of Space, Lefebvre (2013 [1974]) raises the need for a unified theory of social practice space, which we could understand at some point as the radicalization of Engels' gesture in raising the impossibility of dissociating the issue of housing from working conditions and the capitalist mode of production. Although he does not explicitly address the problem of housing, his critique of the fragmentation and dissociation of time and space allows us to consider how the strategies of social reproduction that sustain everyday life are a constitutive part of the production of urban space and are a relevant analytical dimension.

Unlike Lefebvre, whose formulations are rooted in a philosophy of space, Manuel Castells approaches these problems from an urban sociology anchored in political economy. In The Urban Question (1999 [1972]), he presents housing as a condition for the reproduction of the workforce and as a collective consumer good whose provision requires state intervention, while also introducing a critique of planning as exclusively technical, revealing its political nature and placing housing at the intersection of social reproduction and state intervention.

Christian Topalov revisits these discussions by reviewing Marxist-inspired urban research in a work entitled Writing the History of Urban Research: The French Experience since 1965 (1990b). According to this author, research in the 1970s focused on urbanization, public policy, and social movements, but "as effects of structural dynamics, as processes without a subject" (Topalov, 1990b, p. 16), and "practices result from an interaction between the characteristics derived from the position of groups in the social structure and the external conditions that result from the logic of accumulation and state policies" (Topalov, 1990b, p. 16). He identifies that, as a critique of this, a series of studies have emerged that focus on the mediation between practices and conditions and the specificity of the individual, without losing sight of their class position.

Workers are no longer seen as a simple labor force, that is, from the point of view of their function for capital, but also as subjects who develop practices. These class practices do not necessarily take the form of collective action, because popular responses to situations are in principle every day and silent (Topalov, 1990b, p. 17).

Topalov points out that, although this new moment is based on overcoming the gaps left by previous structuralist theories, it does not achieve the theoretical density of its predecessors. In his words, rather than consolidating a robust explanatory framework, what we see is a "rehabilitation of empiricism in the form of an infinite description of singularities" (Topalov, 1990b, p. 17), which fragments the analysis and deprives it of critical generalization capacity. This raises an analytical problem of how to identify differential patterns that structure urban practices without reducing them to abstract determinisms or scattered singularities.

Contributions from the Feminist and Popular Economies Perspective

Marxist-oriented feminist literature offers key tools for identifying differential patterns —particularly gender patterns— that are not diluted into singularities or reduced to structural determinisms. These authors make relevant contributions to the conceptualization of social reproduction in its historical composition and in various reinterpretations of Marx, showing that the growth of the capitalist regime required institutionalizing the separation between production and reproduction on a specific gender basis. Nancy Fraser, in her article The Contradictions of Capital and Care (2020), explains that, on the one hand, social reproduction is one of the necessary conditions for the sustained accumulation of capital, but that, on the other hand, capitalism's orientation toward unlimited accumulation tends to destabilize the very processes of reproduction on which it is based, in what she calls the socio-reproductive contradiction of capitalism (Fraser, 2020). In addition, there are numerous studies documenting how the restructuring of global production relations under neoliberalism negatively affected the conditions of reproduction of the large social majorities, what many authors have called the "crisis of care" (Fraser, 2020). In Argentina in particular, the 2001 crisis was a turning point, when social movements, especially the unemployed workers' movement, took to the streets, raising "questions about work and the demand for a dignified life decoupled from the wage system" (Gago, 2021, p. 960), highlighted the undeniable role of women in the organization of collective spaces dedicated to the reproduction of life (Gago, 2019). Reproductive tasks were no longer relegated exclusively to the home, but were organized into a multiplicity of practices in public spaces such as neighborhoods, picket lines, marches, fairs, etc. Simultaneously, the growing lack of employment led large sectors of the population to devise new forms of self-management of the workforce, in what we now call popular economies. These economies do not simply represent a transitional landscape towards the restoration of traditional wage employment; rather, they have demonstrated persistence and consolidation over time and have exercised a "structuring power of the social in moments of decomposition of state authority" (Gago, 2016, p. 184). This raises the question of the scope of these intelligences and strategies deployed by urban popular sectors —in their domestic and community composition— and how they intersect with processes of popular urbanization.

Latin American Debates on Popular Urbanization

The perspective developed in this paper is based on a well-established tradition within Latin American urban studies, which for decades has questioned the focus on housing deficits and the formal/informal dichotomy. In Latin America, popular urbanization, understood as the set of practices of city-building carried out by the inhabitants themselves, has been the subject of much debate. A first line of analysis links the phenomenon of urban poverty with the dynamics of economic dependence on central countries, which structure the socio-spatial patterns of Latin American cities (Schteingart, 1973). Another major line of debate —widely developed by authors such as Turner and Pradilla— focused on the role of popular participation through self-construction, assuming the contradictions inherent in the model of capitalist production. However, there is broad consensus that this form of city production has reached a level of extension that has become a general characteristic of our cities. The concept of Social Production of Habitat has been widely disseminated in recent decades thanks to civil associations and international conferences linked to the theme of habitat. These are planned modalities whose promotion, management, and supervision come from actors outside the domestic units (Rodríguez et al., 2007). On the other hand, when the initiative, control, and construction remain in the hands of the inhabitants themselves, we are faced with processes of self-production and self-construction of habitat (Rodríguez et al., 2007). In this vein, the contributions of Pírez (2019) help us understand how the issue of housing and infrastructure is resolved in low-income sectors through practices of what he calls reverse urbanization, where the land is first inhabited —devoid of infrastructure, in precarious conditions and sometimes at environmental or water risk— is first occupied and then consolidated through successive processes of popular urbanization, where the stages of production and consumption coexist (Del Río et al., 2011).

Among these practices, Di Virgilio, Mejica, and Guevara (2012) identify four key dimensions in strategies for accessing land and housing: access to land, through direct occupation, informal purchase or sale, or transfer; access to housing, through self-construction, purchase or sale, or informal rentals of rooms; the ownership situation, marked by the absence of state regulation, the lack of titles or contracts, and the exhausting regularization processes faced by residents; and the evolution of the lot, based on the progressive modifications made to the plot —central to the analysis in this work. In turn, Di Virgilio (2011) characterizes family relationships and networks as a fundamental element on which the conditions of the habitat are structured, where strategies are developed to solve housing problems and resources from both social programs and access to public services are linked. In short, for the author, these networks operate as managers of social demands and the resolution of everyday problems, giving rise to collective and individual forms of everyday management (Di Virgilio, 2011).

The articulation of these three theoretical fields allows us to situate housing improvement strategies within a framework that combines productive, reproductive, community, and political-state dimensions. Figure 1 summarizes how these contributions are organized, distinguishing —for analytical purposes and without claiming to be exhaustive—the aspects on which each approach mainly focuses in order to construct the dimensions of analysis.

Methodological Strategy

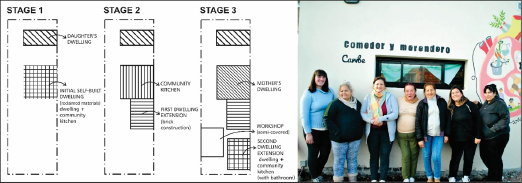

The research develops a methodological strategy situated in the field of urban studies, which articulates conceptual and empirical tools to analyze the interrelationships between housing, work, and the reproduction of life. Housing improvement strategies are proposed as a central category and, based on the theoretical coordinates outlined in the previous section, three dimensions of analysis are constructed: integration of productive and reproductive activities in housing, community networks and territorial disputes, and articulation with public policies for habitat improvement. This work seeks to understand the role of productive, reproductive, and community activities in habitat improvement strategies within popular urbanization processes. These strategies are analyzed based on the housing trajectories of three women from two popular neighborhoods in the city of Mar del Plata (Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina) (see Figure 2). To this end, a qualitative approach is adopted in line with that proposed by Sautu (2005), for whom this type of methodological strategy is appropriate for describing processes, considering the interaction between practices and context, while at the same time allowing the meanings in dispute to be captured. Semi-structured interviews, informal conversations within the framework of participant research, and photographic records were used. Based on this material, housing improvement strategies were graphically reconstructed by observing intralot transformations.

The fieldwork was carried out between 2021 and 2024, within the framework of the implementation of policies promoted by the National Secretariat for Socio-Urban Integration (hereinafter SISU–N) to guarantee access to basic infrastructure and community facilities for the more than 6,647 low-income neighborhoods in Argentina, where, according to ReNaBaP , nearly 1.2 million families live.

In the city of Mar del Plata, the group Science and Technology for Popular Housing (hereinafter CyTHaP) —in which this research is registered— provided social and technical support, coordinating with various institutional and neighborhood actors to implement these policies. The Caribe neighborhood, located in the northwestern part of the city, is newly formed and has a strong network of organized women who have pushed for access to water, electricity, waste collection, and security. The San Jacinto neighborhood, in the southern part of the city, is not a recent development, but the area has undergone a marked growth process in recent years, in which a community space linked to the Movement of Excluded Workers has gained relevance.

The selection of the three housing improvement trajectories was based on specific analytical criteria: that they be located in neighborhoods undergoing active urbanization and popular housing development, that they participate in neighborhood and community networks, and that they present different combinations of self-construction, use of housing space for productive activities, and coordination with public policies.

Results

In low-income neighborhoods, housing represents the life project in which the most effort and money is invested and whose specific temporality often involves long periods of incompleteness, subject to constant transformations and alterations (Caldeira, 2017). The limited economic resources available to many families in low-income neighborhoods are often mobilized to improve their housing as a search for stability and future progress.

The trajectories analyzed below allow us to observe how these dynamics of successive improvement unfold and intertwine different dimensions of everyday life, articulating processes of production and reproduction, the construction of community networks, the organization of territorial struggles, and the implementation of public policies.

Integration of Productive-Reproductive Activities in Housing

As feminist literature has pointed out, the reproductive role historically assigned to women has led them, in many cases, to reconcile productive, reproductive, and community responsibilities in the domestic sphere.

Laura, from the Caribe neighborhood, decided to start a community kitchen in her home, which at the time was still a wooden shack, after the pandemic began. In addition to providing food to many families in the neighborhood (more than 30 families, according to Laura's estimate), the kitchens play a central role in the organization of the daily reproduction of those who support them. Around 20 people work in her soup kitchen, with seven women being the most active, including her mother and daughter (see Figure 3), as well as some neighbors who are also related to each other. These dynamics show a strong female presence and forms of intergenerational cooperation around the organization of care. In parallel with this activity, and within the framework of a public policy for neighborhood improvement, Laura's partner allocated a portion of their land to set up a production center for wooden trash bins, which were then placed at the entrance of all the homes in the neighborhood.

In the case of Julia, from the San Jacinto neighborhood, her sister's political involvement as a leader in the MTE enabled her and her partner to join a worker cooperative and participate in a housing improvement program financed by the Inter-American Development Bank. She started as an assistant, but since she had no one to take care of her children, the organization agreed that she could work as a storekeeper —a person in charge of controlling the tools and machinery used for the work— in a workshop built on her own lot. This transformed her home into a space where productive and reproductive activities are coordinated, creating what Gago describes as a space “where production and reproduction merge” (Gago, 2014, p. 52).

Community Networks and Territorial Struggles

In the cases analyzed, the first step in their housing strategies was residential mobility to cities or neighborhoods with better conditions for access to land. The working-class neighborhoods of Mar del Plata tend to have populations from other provinces or from the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires. Such is the case of Julia, who decided to move with her family from a slum in the City of Buenos Aires to the San Jacinto neighborhood, motivated by overcrowding and supported by previously established social and family networks (Hinojosa Gordonava, 2019). These networks reduce travel costs, improve job opportunities, and facilitate settlement (Sassen, 1993, 2007, as cited in Hinojosa Gordonava, 2019).

Similarly, internal mobility between neighborhoods also responds to the availability of vacant land and family situations. Laura, for example, moved from a neighborhood in the northern part of the city to Caribe, where her eldest daughter and mother also settled, forming a network of co-residence and care.

I had lost my home and was living with my brother, and well, there were a lot of us. I was separated with my two daughters, and this land came up. My brother was going to live here too, but then he didn't like it because there was no electricity, no water, nothing. So, I moved here alone because I had no other choice. So, I bought it as best I could, I paid for it [...] I already had the shed to come and put it up here. (Interview with Laura, 2023)

In addition to Laura's partner and younger daughters, her eldest daughter and her family also settled on the same plot of land: "And behind it, I gave a piece of land to my daughter, who was renting and spending a lot on rent. She came with her husband and my grandson more than two years ago" (Interview with Laura, 2023).

Sometime later, her mother also moved there because she had health problems and needed care, and later, her other daughter moved in with her family. In this way, we can see how family networks generate dynamics that reconfigure the use of the plot and the organization of the dwelling (see Figure 3).

As Hinojosa Gordonava (2019) points out, social networks have an impact on all areas of social reproduction in communities, promoting social, cultural, economic, and political activities. In the cases analyzed, these networks take the form of community spaces located within or next to the homes mentioned above, which play a key role in neighborhood organization, the circulation of information, and coordination with public policies.

In this context, Laura's participation in the MTE, associated with her community kitchen, leads her to attend regular meetings with workers from other kitchens in what they call the 'terri', expanding her networks and organizational links beyond her own neighborhood.

In Julia's case, the MTE community space is located next to her home, where she has participated in the development of an experimental vegetable garden and nursery for the entire neighborhood with the support of a research group.

In Sandra's case —from the Caribe neighborhood— her home serves as a neighborhood dining room and community space where educational activities, celebrations, and health workshops are held. From there, she has spearheaded multiple territorial struggles: collective demands for access to water, electricity, street improvements, among others. Her home is also a meeting and coordination hub where collective strategies are developed to address neighborhood problems (see Figure 4), such as the conflict with the natural gas distribution company Camuzzi, when it imposed a measure that halted the works financed by SISU-N due to their proximity to one of its gas branches.

Finally, in both Laura's and Julia's cases, one can see that, in a short time, these women managed to build strong social networks which, through individual, family, and community strategies, enabled them to promote improvements in their homes and in the neighborhood.

Coordination with Public Policies for Habitat Improvement

During the fieldwork (2021-2024), various projects were carried out in both neighborhoods, financed by SISU-N, which introduced infrastructural improvements to the neighborhood. In the Caribe neighborhood, residential water tanks, indoor electrical connections, sidewalks, public trees, waste collection bins, a playground with children's equipment, and 20 wet units (bathroom and kitchen units integrated into existing homes) were built. Since the community role they played in the neighborhood was considered in the selection of beneficiaries, both Sandra and Laura benefited from a wet unit. This made it possible to separate the spaces linked to housing from community activities. In turn, both were selected in the program Mi Pieza ; Sandra used that money to build a new room and Laura to complete an unfinished room.

In San Jacinto, a housing improvement program financed by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) through SISU-N was implemented. With this improvement program, Julia ‘wrapped’ the wooden shack where she lived with bricks (see Figure 5). She was also selected in the Mi Pieza Program, which enabled her to start an expansion project and, by combining both policies, aspire to a more complete improvement of her home.

It should be noted that the withdrawal of these policies leads families to deploy other types of strategies, among which it is common to take on debt to complete and improve their homes, and in times of greater crisis, this shifts to non-durable goods such as food. In the case of Sandra, whose home is shared by 11 people, she has resorted to this on several occasions.

In the end, I took out a loan. Now I've taken out another one to renovate. I want to do the floor in my room. Always loans to build. I must have taken out between five and six, some from ANSES and others from Efectivo sí . (Interview with Sandra, 2023)

Loans from private companies tend to have high interest rates and, even so, are very low amounts in relation to the actual costs of construction materials. Sheet metal, for example, is a particularly expensive input and, at the same time, indispensable for preventing water leaks in roofs. Limited financial resources often lead to inadequate construction solutions —such as installing sheet metal without a proper wooden or metal support structure— which perpetuates precarious housing conditions. These solutions are not only insufficient to improve housing, but can also pose additional risks, from possible collapses to exposure to strong winds that can tear off roofs. Thus, we see how housing, as a node of productive-reproductive and community articulation, is also subject to interference from financial devices that find potential opportunities for capture there (Cavallero and Gago, 2022).

Conclusions

Popular Urbanization as a Productive-Reproductive Technology

After analyzing some experiences of housing and public infrastructure improvement in two popular neighborhoods in the city of Mar del Plata, we can affirm that the different strategies carried out to improve individual/family reproduction conditions find points of feedback with collective community processes. In the course of this work, we have seen how the boundaries between the productive and the reproductive are blurred in both housing and the neighborhood. The replacement of common public infrastructure and progressive housing processes are interlinked and unfold over long periods of inconclusiveness. But the capacity to develop these processes, as proposed by the Urban Popular Economy Collective, "lies in the fact that they are produced through forms of collectivity based on shared opportunity and ingenuity, rather than on organized forms of collective action" (The Urban Popular Economy Collective, 2022, p. 1).

Ensuring the conditions for reproduction places an exponential burden on working-class neighborhoods, ranging from maintaining the functioning of the household to the condition of housing and the improvement of basic service infrastructure. This enormous unpaid workload often forces women to resort to loans with highly unfavorable interest rates.

Finally, it should be noted that the cases studied show that these women are highly recognized at the neighborhood level and in the networks in which they participate locally. They are listened to by officials and the media and demonstrate strong leadership in carrying out struggles. This confirms that, although the work they do in terms of reproduction is unpaid, it has significant symbolic weight in the neighborhood and in society in general. It is in the popular economies where they find the right place to combine the enormous burden of social reproduction tasks with other forms of work.

The experience of these three women living in the Caribe and San Jacinto neighborhoods shows that housing is not only a physical object subject to progressive improvements, but also a hub that articulates productive and reproductive activities and is linked to community networks and territorial struggles. In these neighborhoods, women transform the domestic space into a workshop, dining room, workroom, or community center, creating a fabric that transcends the conventional categories of "work" and "home."

Returning to Topalov (1990b), although the analysis is based on empirical evidence, an attempt has been made to avoid a mere fragmentary description, seeking to articulate the cases with conceptual frameworks that contribute to a critical understanding of popular urbanization and its disputes with hegemonic models of the city.

The cases analyzed allow us to return to the initial question and provide insights into understanding that the housing problem in Latin America cannot be understood in isolation from working conditions and social reproduction. The fragmented view that predominates in policies and in much of urban studies —anchored in technocratic and dualistic visions of space— leaves out the everyday processes through which families produce and reproduce their habitat. Furthermore, it is evident that the reproduction of life in contexts of public infrastructure deprivation and critical housing conditions assumes a practical indistinction between everyday household tasks and the constant and gradual improvement of the habitat.

In this way, popular urbanization is not only a form of informal access to land, but also a complex practice that challenges the meaning of the city and the right to habitat. Recognizing this articulation implies, on the one hand, restoring the political dimension of the housing issue and, on the other, questioning the disciplinary boundaries that have contributed to its invisibility.

In this sense, the notion of popular urbanization as a productive-reproductive technology is taken up again to refer to a process that is not limited to access to land, but integrates domestic, community, and paid work into the same socio-spatial fabric. This category allows us to understand that the production of the city by popular sectors is not only a response to the lack of formal housing, but also a complex form of social organization that articulates the reproduction of life with the material production of habitat.

This challenges the disciplinary boundaries that reduce housing to its physical dimension and brings to the fore its role as a social and economic infrastructure, produced collectively and sustained through practices that go beyond the classic categories of the urban and the domestic.

References

BRENNER, N. (2009). What is critical urban theory? City 13(2-3), 198-207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810902996466

CALDEIRA, T.P. (2017). Peripheral urbanization: autoconstruction, transversal logics, and politics in cities of the global south. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 35(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816658479

CASTELLS, M. (1999 [1972]). La cuestión urbana (3era ed.). Siglo XXI

CAVALLERO, L. Y GAGO, V. (2022). La casa como laboratorio: finanza, vivienda y trabajo esencial. Fundación Rosa de Luxemburgo.

CLICHEVSKY, N. (2000). Informalidad y segregación urbana en América Latina: una aproximación. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/5712-informalidad-segregacion-urbana-america-latina-aproximacion

DEL RÍO, J. P., RELLI, M., LANGARD, F., CORREA, A., MARICHELAR, G., PEDERSOLI, F. (2011) Apuntes sobre la apropiación y el derecho a la ciudad. Revista Herramienta, 48, 119-136. http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/88327

DEL RÍO, J.P. Y GONZÁLEZ, P. (2019). Implementación del programa “Lotes con Servicios” en el marco de la ley de acceso justo al hábitat, provincia de Buenos Aires. Derecho y Ciencias Sociales, 21, 37-59. https://doi.org/10.24215/18522971e055

DI VIRGILIO, M. M., MEJICA, M. S. A., Y GUEVARA, T. (2012). Estrategias de acceso al suelo y a la vivienda en barrios populares del Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires. Revista Brasileira De Estudos Urbanos E Regionais, 14(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.22296/2317-1529.2012v14n1p29

DI VIRGILIO, M.M. (2011). Producción de la pobreza y políticas públicas: encuentros y desencuentros en urbanizaciones populares del Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires en J. Arzate Salgado, A. Gutiérrez y J. Huamán (coords.), Reproducción de la pobreza en América Latina Relaciones sociales, poder y estructuras económicas (pp. 171-206). CLACSO-CROP.

ENGELS, FRIEDRICH (2006 [1873]). Contribución al problema de la vivienda. Fundación de Estudios Socialistas Federico Engels

FRASER, N. (2020). Los talleres ocultos del capital: un mapa para la izquierda. Traficantes de Sueños.

GAGO, M. V. (2014). La razón neoliberal: economías barrocas y pragmática popular. Tinta Limón.

GAGO, M. V. (2016). Diez hipótesis sobre las economías populares. Desde la crítica a la economía política. Nombres, 30, 177-196 https://revistas.unc.edu.ar/index.php/NOMBRES/article/view/21240

GAGO, M. V. (2019). La potencia feminista: o el deseo de cambiarlo todo. Tinta Limón.

GAGO, M. V. (2021). Neoliberalismo y después: empresarialidad, autogestión y luchas por la reproducción social. Contemporânea, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.4322/2316-1329.2021022

HINOJOSA GORDONAVA, A. (2019). Trayectorias poblacionales en y desde La Paz: de la migración interna a la construcción del sujeto político transnacional. Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, Carrera de Trabajo Social, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales.

JARAMILLO, S. (2021). Heterogeneidad estructural en la ciudad latinoamericana: más allá del dualismo. Ediciones Uniandes.

LEFEBVRE, H. (2013 [1974]). La producción del espacio. Capitán Swing.

PÍREZ, P. (2019). Hacia una perspectiva estructural de la urbanización popular en América Latina. Pensum 5(5), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.59047/2469.0724.v5.n5.26297

RODRÍGUEZ, M. C., DI VIRGILIO, M. M., PROCUPEZ, V., VIO, M., OSTUNI, F., MENDOZA, M. Y MORALES, B. (2007). Producción social del hábitat y políticas en el Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires: historia con desencuentros. Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires. https://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Argentina/iigg-uba/20100720101204/dt49.pdf

SAUTU, R. (2005). Todo es teoría: objetivos y métodos de investigación. Lumiere.

SCHTEINGART, M. (COMP.) (1973). Urbanización y dependencia en América Latina. Ediciones Siap.

THE URBAN POPULAR ECONOMY COLLECTIVE, BENJAMIN, S., CATRONOVO, A., CAVALLERO, L., CIELO, C., GAGO, V., GUMA, P., GUPTE, R., HABERMEHL, V., SALMAN, L., SHETTY, P., SIMONE, A., SMITH, C., TONUCCI, J. (2022) Urban popular economies: territories of operation for lives deemed worth living. Public Culture, 34(98), 333–357. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-9937241

TOPALOV, C. (1990A). De la “cuestión social” a los “problemas urbanos”: los reformadores y la población de las metrópolis a principios del siglo XX. Historia de ciudades: cultura y economía política de los espacios urbanos 125, 337-354. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000087076_spa

TOPALOV, C. (1990B). Hacer la historia de la investigación urbana: la experiencia francesa desde 1965. Sociológica 12(5), https://sociologicamexico.azc.uam.mx/index.php/Sociologica/article/view/947

María del Pilar Isla

Architect from the Faculty of Architecture, Urbanism, and Design at the National University of Mar del Plata (FAUD-UNMdP). PhD candidate in the Urban Studies Program at the National University of General Sarmiento (UNGS). Doctoral fellow at the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), working at the Institute for Research in Urban Development, Technology, and Housing (FAUD-UNMdP).

Autor

City-Making and Sustaining Life

Housing, Labor, and Social Reproduction in Popular Urbanization.

City-Making and Sustaining Life

City-Making and Sustaining Life

The premise guiding the analysis argues that the persistent housing problem in Latin America cannot be fully understood without considering its articulation with forms of work and processes of social reproduction. This allows us to shift the analysis from a focus exclusively on the housing deficit or the physical conditions of housing to an interpretation that understands it as part of a network of domestic, productive, and community strategies that sustain life.

City-Making and Sustaining Life

City-Making and Sustaining Life

City-Making and Sustaining Life

Figure 1. Theoretical-analytical articulation diagram

Source: Own elaboration.

City-Making and Sustaining Life

Figure 2. Caribe and San Jacinto neighborhoods

Source: Prepared by the authors based on MGP and RENABAP.

City-Making and Sustaining Life

Figure 3. Laura's intralot trajectory - Photograph of the dining room and its workers

Source: Own elaboration. CyTHaP archive photograph.

City-Making and Sustaining Life

Figure 4. Sandra's intralot trajectory. Neighborhood meeting on access to water

Source: Own elaboration. CyTHaP archive photograph.

City-Making and Sustaining Life

Figure 5. Julia's intralot trajectory - Image of the envelope improvement process

Source: Own elaboration. Personal archive.

City-Making and Sustaining Life

City-Making and Sustaining Life

City-Making and Sustaining Life