Fuente: Autoría propia

Housing as a socio-material artifact in Manizales:

aspirations, appropriation, and the market[1]

La vivienda como artefacto socio-material en Manizales:

aspiraciones, apropiación y mercado

A habitação como artefacto sociomaterial em Manizales:

aspirações, apropriação e mercado

Le logement comme artefact socio-matériel à Manizales :

aspirations, appropriation et marché

Gregorio Hernández-Pulgarín

Universidad de Caldas

gregorio.hernandez@ucaldas.edu.co

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9659-4063

Geraldine Buitrago Rodas

Universidad de Caldas

geraldinbuitragorodas@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-4534-5823

How to cite this article:

Hernández-Pulgarín, G.; Buitrago, G. (2025). Housing as a socio-material artifact in Manizales: aspirations, appropriation, and market. Bitácora Urbano Territorial, 35(III): 273-284.

https://doi.org/10.15446/bitacora.v35n3.122534

Recibido: 1/9/2025

Aprobado: 20/11/2025

ISSN electrónico 2027-145X. ISSN impreso 0124-7913. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá

[1] This text is derived from a one-year research internship in the Anthropology program, through training and research processes within the framework of the Territorialities research group and the Terranova research seedbed at the University of Caldas (Colombia).

(3) 2025: 273-284

E_20_122534

Autor

Abstract

This article presents an integrative perspective that analyzes the symbolic, use, and exchange values of housing in Manizales, Colombia. It seeks to understand how middle- and lower-income aspiring homeowners and homeowners negotiate the tensions between meaningful and aspirational horizons, practices of appropriation of domestic space, and the constraints of the financialized market. A qualitative and documentary methodology was used, including a review of trade union and institutional sources and semi-structured interviews with people with housing aspirations and homeowners. The results reveal that housing transcends its economic and material role to become a fundamental element of well-being, identity, and sense of belonging. Restrictions on access to housing shape its exchange value; despite this, it retains its status as an artifact that represents status, inheritance, moral debt, and triumph, while also being an asset that offers security, comfort, and privacy.

Keywords: housing, urban planning, debt, market economy, aspirations

Resumen

Este artículo presenta una perspectiva integradora que analiza los valores simbólicos, de uso y de cambio de la vivienda en Manizales, Colombia. Busca comprender cómo los aspirantes y propietarios de sectores medios y populares negocian las tensiones entre los horizontes significativos y aspiracionales, las prácticas de apropiación del espacio doméstico y las restricciones del mercado financiarizado. Se utilizó una metodología cualitativa y documental que incluyó la revisión de fuentes gremiales e institucionales y entrevistas semiestructuradas a personas con aspiraciones de vivienda y a propietarios. Los resultados revelan que la vivienda trasciende su papel económico y material para convertirse en un elemento fundamental para el bienestar, la identidad y el sentido de pertenencia. Las restricciones al acceso a la vivienda configuran su valor de cambio; a pesar de esto, ella preserva su condición de un artefacto que representa estatus, herencia, deuda moral y triunfo, al tiempo que es un bien que ofrece seguridad, comodidad y privacidad.

Palabras clave: vivienda, planificación urbana, deuda, economía de mercado, aspiraciones

Resumo

Este artigo apresenta uma perspetiva integradora que analisa os valores simbólicos, de uso e de mudança da habitação em Manizales, Colômbia. Procura compreender como os aspirantes e proprietários dos setores médios e populares negociam as tensões entre os horizontes significativos e aspiracionais, as práticas de apropriação do espaço doméstico e as restrições do mercado financeirizado. Foi utilizada uma metodologia qualitativa e documental que incluiu a revisão de fontes sindicais e institucionais e entrevistas semiestruturadas com pessoas com aspirações de habitação e proprietários. Os resultados revelam que a habitação transcende o seu papel económico e material para se tornar um elemento fundamental para o bem-estar, a identidade e o sentimento de pertença. As restrições ao acesso à habitação configuram o valor de troca da habitação; apesar disso, esta preserva a sua condição de artefacto que representa estatuto, herança, dívida moral e triunfo, ao mesmo tempo que é um bem que oferece segurança, conforto e privacidade.

Palavras-chave: habitação, planeamento urbano, dívida, economia de mercado, aspirações

Résumé

Cet article présente une perspective intégratrice qui analyse les valeurs symboliques, d’usage et d’échange du logement à Manizales, en Colombie. Il cherche à comprendre comment les candidats à l’accession à la propriété et les propriétaires issus des classes moyennes et populaires gèrent les tensions entre les horizons significatifs et aspirationnels, les pratiques d’appropriation de l’espace domestique et les contraintes du marché financiarisé. Une méthodologie qualitative et documentaire a été utilisée, comprenant l’examen de sources syndicales et institutionnelles et des entretiens semi-structurés avec des personnes ayant des aspirations en matière de logement et des propriétaires. Les résultats révèlent que le logement transcende son rôle économique et matériel pour devenir un élément fondamental du bien-être, de l’identité et du sentiment d’appartenance. Les restrictions d’accès au logement déterminent sa valeur d’échange ; malgré cela, il conserve son statut d’artefact représentant le statut social, l’héritage, la dette morale et la réussite, tout en étant un bien offrant sécurité, confort et intimité.

Mots-clés : logement, urbanisme, dette, économie de marché, aspirations.

Introduction

In Colombia, owning your own home is becoming decreasingly common, yet it remains a vital goal. In cities such as Manizales, aspiring to 'own a home' is not only a challenge marked by market logic, but also a project that shapes individual biographies, family commitments, and expectations about the future (Appadurai, 2004; Núñez, 2020; Lombana Useche & Ruiz Gómez, 2024). This aspiration is confronted on the one hand by housing prices, mortgage credit, and restrictions on available land, and on the other hand by personal and family finances dependent on increasingly flexible or informal jobs, as is often the case in countries in the Southern Cone of America.

Access to housing, as in other countries on the subcontinent, is marked by the gap between income and prices, which particularly limits households in the VIS and VIP segments. According to the 2024 Quality of Life Survey by the National Statistics Department (DANE), only 39.6% of households live in their own homes, which shows persistent deprivation and a high dependence on subsidies and credit, making housing a scarce and highly valued social good.

In the first three months of 2025, according to the Colombian Chamber of Construction (Camacol, 2025), pre-sales of new homes fell by 4.5% compared to the same period last year, and construction starts decreased by 52.7%. This reveals the structural instability of a sector vulnerable to economic indicators such as cooling demand, unemployment rates, rising credit costs, and limited or reduced subsidies.

Similarly, the absence of a long-term housing policy creates uncertainty regarding the distribution of subsidies and threatens the accessibility of new housing for the middle and lower-middle classes. The interruption or changes in subsidy programs impact families that depend on both subsidies and mortgage loans, especially since used homes do not receive state support. Without the subsidy, equivalent to about 20% of the value of VIS and up to 30% of VIP, in addition to interest rate coverage, the aspiration of owning one's own home becomes distant and uncertain.

In addition to the above, we can add some conditions of the credit system, such as high interest rates on loans, which create further restrictions on access to housing for population groups with unstable incomes: stable employees with low salaries, young people in precarious jobs, and self-employed workers. According to Lombana and Ruiz (2024), the credit system in Colombia presents obstacles for many applicants due to its rigidity, strict requirements, and the exclusion of those with income from unconventional sources. The credit supply tends to make access more expensive and perpetuate a pattern of exclusion that exacerbates the housing crisis for low-income families and the middle class.

These national dynamics are evident in an intermediate Andean city in Colombia such as Manizales, where the physical and environmental setting structurally determines the supply of developable land for its nearly 450,000 inhabitants. The 2015–2027 POT and associated technical documents describe a territory of hillsides with large areas at risk of landslides, runoff corridors, and preservation areas that limit expansion and make urbanization and construction more expensive, limiting the final supply. In terms of the urban economy, this rigidity of supply puts pressure on land values and, consequently, on the exchange value of housing, with more acute effects on the social segment when subsidies slow down (Manizales City Hall, 2017).

Placing this case in a Latin American context allows us to understand that the problems concerning exchange value for applicants are not limited to housing in Colombian cities such as Manizales. Various authors who address the problem of the financialization of housing in Latin America, with special emphasis on cases in Chile, Mexico, and Brazil, report on the conversion of housing into a financial asset and the expansion of market mechanisms (mortgage credit, securitization, funds, and platforms) that have been controlling the production of and access to housing (Abeles, Pérez Caldentey, and Valdecantos 2018; Daher, 2013; Rolnik, 2018; Monkkonen, 2011). The work coordinated by Delgadillo (2021) shows that financialization, by shifting the focus from the right to decent housing to the logic of economic return, has transformed cities. Authors such as Marín-Toro, Guerreiro, and Rolnik (2021) point out that renting, whether formal or informal, has become the new frontier of this process; families have taken on risks and uncertainties that used to fall on the market or the state. In response to this situation, various international assessments (UN-Habitat, 2020; Rolnik, 2018) call for a rethinking of housing policies in Latin America, where housing prices are rising faster than incomes.

A qualitative approach that seeks to understand the universes of meaning that revolve around housing can complement the economic and regulatory perspectives that tend to predominate in housing analysis. From this perspective, housing can be considered a vital place, a symbol of achievement, or an aspirational horizon; it can become an event culturally shaped by capitalist aspirational pressure, a principle of existential rootedness, and a means of recognition (Núñez, 2020). More than a market object or a container, it is a complex artifact that combines structures, practices, affections, and symbolic logics associated with the experience of inhabiting. It can also be understood as a fundamental element in the construction of status and social distinction. Housing mobilizes life trajectories, family decisions, and even commitments or ‘moral debts’ that go beyond the financial and are fundamental to the maintenance of social relationships.

Among the literature produced in Latin America along these lines, there is a clear commitment to approaches that allow housing to be understood from an aspirational perspective (Lombana Useche & Ruiz Gómez, 2024; Stillerman, 2017) or as the result of material and symbolic work, which mediates daily between the home as a refuge and housing as a financial asset (Hurtado Tarazona, 2018). Other approaches emphasize the forms of subjectivation associated with neoliberal rationality, such as that of Quentin (2023), which shows that demand subsidy programs in Latin America deploy mechanisms of individual accountability that transform the right to housing into a practice of self-management and indebtedness; or that of Besoain and Cornejo (2015), which shows how the transition from informal settlements to social housing promotes a privatization of living, in which collective action retreats into domestic intimacy. These studies therefore support the premise that the experience of having or not having housing and the decision to seek access to it, despite structural difficulties, has symbolic, subjective, and social dimensions that can be understood through approaches that privilege the voices and experiences of the actors themselves.

From this perspective, the purpose of this article is to reflect, with a theoretical and empirical basis, on the question: How do middle —and low— income housing seekers in Manizales negotiate the tensions between their aspirational horizons, their practices of appropriation of domestic space, and the constraints of the financialized housing market? This purpose is developed from three perspectives related to the issue of housing. The first (anthropological) perspective examines housing as a life project and territory of intimacy (use value) and as a symbol of achievement and intra-family ‘moral debt’ (symbolic value). The second (urban planning, with an emphasis on economy) analyzes the determinants of exchange value: prices and costs (materials, land, and urbanization), rates and credit, subsidies and regulation, as well as the geomorphological rigidities that restrict land use. The hypothesis we propose as the basis for this article is that these three dimensions of value coexist and are interdependent.

Conceptualizing the Dimensions of Value Addressed

We start from a broad notion of value that distinguishes, without separating, three analytical dimensions: use value, symbolic value, and exchange value. Use value refers to the capacity of housing to support everyday practices, rest, care, privacy, sociality, and the material configuration that makes them possible (layouts, light, ventilation, accessibility). This axis dialogues with anthropology, which understands the home as a 'territory of intimacy' and as a socio-material assembly that organizes belongings, memories, and routines: Giglia (2012) proposes thinking of inhabiting as a cultural operator rather than as a simple occupation of space; Di Masso, Vidal & Pol (2008) emphasize person-place links and their processual nature; Zamorano (2007) avoids the reductive 'container/content' metaphor and shows the co-production of housing and family. These contributions allow for a conception of housing, or rather 'the house' or 'the home', as an artifact of social life that anchors domestic identities and temporalities, articulating materials, affections, and norms, rather than as an infrastructure of needs.

The 'symbolic value', inspired by the works of J. Baudrillard (2009) on the transcendence of goods, their use value and exchange value, indicates that housing concentrates signs and recognitions, is a marker of status and belonging, and a privileged object of aspiration. The literature on aspirations suggests that the desire to 'own a home' is not merely an individual impulse, but a culturally shaped capacity influenced by social repertoires and references (Appadurai, 2004), with performative effects on life trajectories. Development economics has also conceptualized 'aspiration thresholds' and their relationship to economic behavior related to saving, borrowing, investing, etc. (Ray, 2006; Genicot & Ray, 2017). From a sociological perspective, housing, its location, materials, and domestic 'staging' convey distinction and capital (in the manner of Bourdieu), something empirically documented in studies on residential 'display' and its grammar of achievement; the home operates as a symbol of status, achievement, and belonging, and as a horizon of mobility (or recognition) that structures family and biographical projects.

The 'exchange value' refers to housing as a commodity and as an asset in urban and financial markets. In recent decades, the home has been integrated into credit, securitization, and portfolio circuits, with the growing prominence of financial actors and metrics (Aalbers, 2016). In Latin America, waves of financialization are reorganizing the production of space, shifting risks to the home, and reconfiguring access (Delgadillo, 2021). This perspective allows us to articulate the determinants of affordability: income, interest rates, credit rationing, with institutional arrangements and production regimes, pre-sales, trusts, and subsidies. This helps to understand why rising rates and unstable subsidies, combined with restrictions on available land, sustain high prices and make access more fragile and difficult, particularly for households in the VIS and VIP segments. In this context, the experience of acquiring housing as a market commodity becomes a process fraught with challenges, uncertainties, and sacrifices, in the face of which applicants nevertheless deploy various strategies to achieve their goal.

A useful bridge between the symbolic and the economic is offered by the notion of 'moral debt' (Graeber, 2011): beyond mortgage credit as a contractual obligation, there persists a moral economy where 'providing a home for one's mother', 'ensuring a roof over one's children's heads' or 'fulfilling one's family obligations' burdens housing with obligations and legitimacies that exceed financial accounting. This moral dimension helps to understand why the desire for housing persists even when market conditions become adverse: it is not only a good for use and an investment that is sought, but also the fulfillment of duties and promises that organize kinship and reputation.

On this basis, we propose a relational framework for housing: as a space that is lived in and materially supported (use value); as a symbol of achievement, status, and moral debt, driven by aspirational tendencies and grammars of distinction (symbolic value); and as an asset whose price formation depends on institutions, finance, and land structure (exchange value). Theoretically, the key is not to hierarchize these levels, but to show their co-determination.

Methodological considerations

We use a qualitative perspective with a triangulation of statistical and documentary data to advance the research. Our goal is to understand the connection between experiences and meanings with market conditions, credit, subsidies, and territorial limitations surrounding the phenomenon of housing.

We conducted 20 semi-structured interviews with housing applicants (VIS/VIP and Non-VIS) who are residents or intend to purchase in Manizales. The selection was intentional/theoretical to maximize variation: gender and age; type of employment (formal/independent); previous experience (pre-approval, withdrawal, purchase in progress), and price range/segment (VIS, VIP, Non-VIS). The interviews (30–60 min) were conducted in person in spaces agreed upon with the participants. The script addressed: residential trajectories; motives and horizons for ‘owning a home’; desired configurations (architectural and location); ‘moral debts and family expectations; experiences with credit/subsidies; and perceptions of prices, supply, and delivery times. All participants gave informed consent, we pseudonymized identities, and we suppressed sensitive data. We supplemented this with online observation (consulting social media and local housing portals) to capture aspirational repertoires, supply language, and public discussions about subsidies and prices, as well as reviewing national and local press coverage on the subject.

At the same time, a documentary corpus was constructed with statistical and regulatory series that allowed us to place individual experiences in the sectoral and territorial context: prices and market dynamics; credit and rates; housing policy, and land use planning in Manizales.

For the analysis, thematic coding of fundamental categories (use value, symbolic value, and exchange value) and emerging subcategories was used, creating case-category matrices and analytical memos that brought the narratives into dialogue with sectoral evidence. Among the limitations are the sample size of interviews, which cannot be generalized, and the dependence on official and trade association statistics for the economic component. However, these restrictions were mitigated by contrasting local narratives, ethnographic observation, conversations with experts, and critical review of secondary sources, which enriched the interpretation of the phenomenon in a contextual key.

Results: The Dimensions of Housing Value

Exchange value

The exchange value of housing is presented as an area that brings together the macroeconomic dynamics of financialization with the everyday experiences of owners and aspiring owners, who seek to realize a life project in a market that is often adverse to them. National data confirm a structural change in ownership: in Colombia, the number of rented homes (7.3 million) exceeds the number owned by homeowners (7.1 million), making the country the one with the highest rental rate in Latin America (El Espectador, 2025).

In the first three months of 2025, the New Housing Price Index grew by 3.46% compared to the previous quarter, which is more than the 2.64% recorded a year earlier, according to DANE. This shows that prices are holding steady despite weakened demand (DANE, 2025). Camacol (2025a) asserts that market adjustment occurs mainly in terms of quantity: new construction starts fell by 52.7% during the same period, while launches increased by 12.7%, anticipating deliveries after 2026. This tactic of postponing supply prevents prices from falling nominally and artificially sustains exchange value, which limits the arrival of new customers and accentuates market exclusion (see Image 1).

For households and individuals, access is limited and expensive due to the loans they must take out to purchase a home. Effective rates for mortgage loans have been above 10% in recent years and require stable and formal employment profiles. Interviews show that bank debt is both a material and emotional burden. Several participants agree that they must deprive themselves of numerous expenses to save the necessary down payment. This is not only the case for mortgage loans, but also for consumer loans, which in many cases are used to cover the down payment or finishing touches on the home. In this context, housing, especially mortgages, represents a sacrifice and a form of discipline that determines daily life, producing individuals who define their lives according to the economic circumstances imposed by the neoliberal context of financialization (Sánchez Uriarte & Salinas Arreortua, 2023).

Subsidies, which are supposed to reduce the burden, end up creating uncertainty and exclusion. The end of the Mi Casa Ya program in December 2024 had an impact on VIS/VIP pre-sales and on the financial completion of projects that were underway, making access even more difficult for applicants (Ministry of Housing, 2024) (see Image 1). The accounts of the participants in this research coincide in highlighting the bias towards those with economic capacity and the rigidity of the bureaucracy. For example, Lisa was not eligible for a subsidy, but she was one of the lucky few who received help from a high-income relative to make the purchase. Sol, for her part, had to deal with the requirements and delays involved in proving her right to receive the subsidy. In this context, housing subsidies are not instruments of inclusion, but rather market mechanisms that perpetuate inequality and create uncertainty. In practice, they reinforce selectivity toward families with greater economic capacity and regulate low-income sectors in terms of debt, bureaucracy, and waiting times. This confirms that subsidy policy does not neutralize financialization but rather deepens it by shifting the burden of risk and the moral legitimacy of ‘deserving’ housing to households.

In the case of Manizales, the rugged topography acts as a multiplier of exchange value. The scarcity of developable land raises the price per square meter to $4.4 million on average, above cities such as Cali and Armenia (LaHaus, 2025), with the aggravating factor that much of the supply is concentrated in non-VIS projects (61%). Despite a partial recovery in the first half of 2025, social housing sales continue to lag (Camacol Caldas, 2025). In addition, units are delivered as ‘gray construction’, which means that households must assume the cost of finishing touches, and it takes longer to be able to fully inhabit the property. A recurring sentiment among buyers and prospective buyers is their frustration at the impossibility of accessing housing that requires new debts or costly repairs to be truly habitable, which makes the dream of owning their own home a journey fraught with difficulties.

In general, in Manizales there is a tension between what is desired and the limitations in terms of the exchange value of housing. Demanding credit, rigid prices, unstable subsidies, and a lack of land create a market that rewards solvency and punishes vulnerability. At the same time, the stories show how families implement tactics of saving, borrowing, family support, or investment in rentals to circumvent a system they consider rigid and unfair. Therefore, exchange value is not only manifested in market figures: it is also present in deprivation, sacrifice, and the reframing of debt as an investment. More than just a commodity, housing is an essential arena of conflict between financial logic and families' hopes for stability and security.

The value of use

The analysis shows that the candidates and homeowners consulted in Manizales do not consider housing solely as a physical space that satisfies material needs, but also as a fundamental element of daily life, closely related to autonomy, well-being, and identity. In this dimension, according to A. Giglia (2012), the home is an artifact of social life, a territory of intimacy that is domesticated, that is, appropriated in everyday life through culture. The home involves emotions, routines, and relationships by connecting the tangible aspects of space with the meanings and practices inherent to them.

In the stories collected, the home is mentioned numerous times as a space of refuge and well-being, beyond its physical aspect. It is a place that combines freedom, security, and purpose. For Alex, it is his ‘favorite place in the world’, while for Tulio it has a connotation of refuge, of ‘being everything’, which links it to security and fulfillment. The home of Armando, who is blind, has become a refuge of tranquility and quality of life, which contrasts with the conditions in which he lived before. Applicants who do not have housing do not feel that the place they rent or the family home is their own, nor can they transform or use them according to their aspirations, so these spaces do not acquire the meaning of those they bought, much less that of the home they still dream of.

The functionality, characteristics, and size of the home are presented as essential elements of its use value. The participants in the research agree that spacious and well-distributed spaces improve personal and family life, which significantly influences how well-being is perceived (see Table 1). While some highlight the possibility of modifying the house according to their taste, to eliminate barriers and ensure comfort, others appreciate light and windows as a guarantee of quality of life. There is also a discrepancy between the ideal, especially among those who are not yet homeowners, of having a ‘spacious house with a green area’, and what the market offers for their limited budgets: apartments of 30 to 40 m². This difference between the desired home and reality negatively affects the quality of life of the inhabitants.

Another aspect of use value is represented by the aesthetic and experiential appropriation of the space of the dream home, or one acquired through a loan. Actions such as painting, decorating, or choosing the materials for the final touches are often cited as expressions of appropriation and the manifestation of identity, giving it the character of a home. Alex recalls that when he acquired the keys to his first apartment, the first thing he did to make it his own was to paint the rooms. Luisa appreciates the freedom she has ‘with regard to space and color’, while Alexandra opts for a minimalist style to distinguish herself from the family aesthetic and express her individuality. Sol recounted her enthusiasm for the process of finishing her apartment, which was delivered in gray work, choosing the woods and colors and the design of her new home, which she describes as ‘very cozy’, in keeping with her style and taste. These experiences show the relevance of the link between people and spaces in the construction of senses of identity and belonging (Di Masso, Vidal, and Pol 2008). In this sense, aesthetically personalizing one's home is not limited to a decorative action; it is rather a symbolic act of appropriation that transforms the space into an extension of identity and a 'refuge for the soul' (Bachelard, 2000), which shows that the value of use is determined at the material, emotional, and cultural levels.

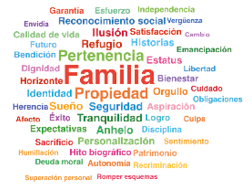

Symbolic value

In Manizales' analysis, housing, rather than a financial asset or physical support, represents a social and biographical mark that encapsulates aspirations, family histories, and forms of recognition. Its symbolic value is based on the pride of overcoming hardship, on the notion of success so widespread in global modes of producing subjects under individualistic, developmentalist, and economistic criteria, and on the moral obligation that unites generations through inheritance and protection. The compiled stories show that housing is a place where the meanings of identity, security, and autonomy are concentrated; at the same time, it serves as a private refuge and an indicator of status.

A common theme is the pride experienced in overcoming precarious situations and achieving a long-awaited goal. This is illustrated by the story of Luisa, who burst into tears when she received her home because, years earlier, people had mocked her determination to save money; or by Sol, for whom buying a home on her own, without inheritance or substantial support, was proof of an effort that dignified her; or by Tulio, who described his purchase as a break with a ‘legacy of poverty’. The perception of housing as an indicator of status and an expression of identity reinforces this sense of achievement. Housing is presented as a place to reinterpret individual experience, establish a personal aesthetic, and strengthen self-esteem, often in contrast to inherited styles. Simultaneously, there is a biographical dimension: while some try to break with family traditions, others appreciate that the house expresses their stories and personality. This demonstrates how the space where one lives becomes a support for identity and symbolic expression.

The 'dream of home ownership' is framed within a neoliberal logic that transforms aspiration into an imperative of self-improvement and discipline, where success may depend on the ability to take on debt and endure prolonged sacrifices. 'The little house of one's own' continues to be the great dream, even though it often seems impossible to achieve. This desire is related to the values of sacrifice and discipline, as it involves depriving oneself of things, taking on long-term debt, and striving relentlessly to reach what is understood as a horizon of success and security. The narratives indicate that families use a significant portion of their income to pay off loans, save for years for the down payment, or take on the burden of extra debt to finish and adapt their homes. Sometimes, the financial pressure can mean spending more than 80% of household income to pay the installments, seeking support from relatives to avoid defaulting, or considering other desperate measures in times of unemployment or reduced income, something that is often interpreted by debtors as a great achievement rather than the creation of a precarious situation. The motivation to own a home, despite economic difficulties, Kafkaesque paperwork, and even a lack of support, which sometimes manifests itself as envy or resistance on the part of loved ones, remains stronger than the emotional and material costs.

This dream of owning a home transcends the need for a roof over one's head: it is experienced as a 'refuge' and a space of autonomy, laden with meanings of social recognition and 'moral debt' towards the family. The emotions associated with receiving a home —tears of satisfaction, the excitement of offering security to one's children, or the pride of having a space of one's own— reveal that the home is also a biographical milestone and a commitment to the family. Even those who wish to buy outside the banking system maintain the aspiration to build or acquire a home, seeing it as family heritage and legacy. In this sense, the dream of homeownership becomes a vital organizer of individual and collective projects that, despite market adversities, drives critical, creative, or even clandestine strategies, such as lending a name to access credit or keeping the purchase secret, confirming that homeownership is at once a desire, a sacrifice, and a life horizon (see Image 1).

In Manizales, the symbolic value of housing manifests itself as a vital horizon that structures life projects, links family expectations, supports stories of recognition and independence, and reaffirms the contemporary subjectivity of individual or family success through possessions. It represents a dimension that strengthens self-esteem, communicates security, and organizes the sense of the future, despite being affected by conflicts with the market, fragmented policies, and family mandates. Housing is, in short, a sociocultural object loaded with meanings, synthesizing achievements and debts, freedoms and obligations, aspirations and frustrations, and sustaining itself as a central element of social and biographical life in a context of structural inequality.

Discussion and Conclusions

Housing cannot be considered solely as a consumer good that is regulated by prices, credit, and subsidies, like any other market product. The findings support the idea that housing includes social, material, and symbolic elements that are intertwined in the daily life of households. In terms of its use value, it is a place for privacy, a space for comfort, and a support for family life. In terms of its symbolic value, it becomes a goal to achieve, a source of social recognition, and a moral responsibility toward the family. And its exchange value makes it a property exposed to financialization with rigid prices, scarce credit, and varying incentives that determine the possibilities of access.

This multidimensional perspective makes it possible to understand that the three levels of value coexist, affect each other, and come into tension. The desire to own one's own home (symbol) is based on the possibility of personalizing and inhabiting a space (use), but this aspiration is limited by the barriers of financing and market laws (change). On the other hand, the discontinuity of subsidies (change) and the rigidity of credit modify paths to residence and delay ambitions, while the social reputation of ‘owning one's own home’ (symbol) promotes sacrifices and extended debts that are passed on from one generation to the next.

In Manizales, access to new housing is determined by spatial and market factors, with particularities such as rugged topography and the concentration of non-VIS projects, which can exacerbate the marginalization of those who depend on subsidies and credit. However, this exclusion coexists with the desire and need for housing among representatives of the middle and lower-middle classes, which shows that access is not determined solely by market logic, but also by social and emotional aspirations. In this context, the local experience reflects a broader reality: housing cannot be considered simply an isolated economic fact or, as Zamorano (2007) would say, a container space, but must be seen as a socio-material artifact in which individual and family trajectories, public policies, urban structures, affections, and moral mandates are intertwined.

On the other hand, the experiences analyzed dialogue with Latin American research that shows how housing, especially subsidized housing, as in a case in Soacha (Colombia), creates tension between affective appropriation and market demands, where economic valuation regulates living (Hurtado Tarazona, 2018). They also reveal the tension that appears in cities such as Santiago de Chile, between the privatization of domestic space in its experience and the process of acquisition versus the collective sense of the right to the city (Besoain and Cornejo, 2015); or that between housing as a social responsibility and an individual one subject to neoliberal governmentality (Quentin, 2023).

Finally, recognizing housing as a right implies considering its materiality, social value, and meanings at the same time. This suggests that public policies should no longer be considered solely as a transferable asset but should begin to be viewed as an essential support for citizenship. This perspective also opens fertile ground for future comparative research in Latin America, where the tension between financialization and the right to housing arises in a variety of urban situations.

References

Aalbers, M. B. (2016). The financialization of housing: A political economy approach. Routledge.

ABELES, M., PÉREZ CALDENTEY, E., & VALDECANTOS, S. (EDS.). (2018). Estudios sobre financiarización en América Latina. CEPAL.

APPADURAI, A. (2004). The capacity to aspire: Culture and the terms of recognition. En V. Rao & M. Walton (Eds.), Culture and public action (pp. 59–84). Stanford University Press.

BACHELARD, G. (2000). La poética del espacio. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

BAUDRILLARD, J. (2009). La sociedad de consumo: Sus mitos, sus estructuras. Siglo XXI.

BESOAIN, C., & CORNEJO, M. (2015). Vivienda social y subjetivación urbana en Santiago de Chile: Espacio privado, repliegue presentista y añoranza. Psicoperspectivas. Individuo y Sociedad, 14(2), 16–27. https://www.psicoperspectivas.cl/index.php/psicoperspectivas/article/view/369/427

BOURDIEU, P. (1979). La distinción: Criterios y bases sociales del gusto. Taurus.

CAMACOL. (2025). Coordenada Urbana: Informe trimestral de vivienda. Bogotá, Colombia: Camacol. https://camacol.co/productividad-sectorial/modernizacion-empresarial/coordenada-urbana

CAMACOL. (2025A). Tablas de coyuntura — Coordenada Urbana (corte 2025). https://www.cccuc.co/coyuntura/tablas

CAMACOL CALDAS. (2025). Informe de mercado inmobiliario Manizales-Caldas. Manizales, Colombia. https://camacolcaldas.com/noticias/uncategorized/primer-semestre-2025-senales-de-recuperacion-con-comportamientos-desiguales-en-el-mercado-inmobiliario/

DAHER, A. (2013). Territorios de la financiarización urbana y de las crisis inmobiliarias. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, (56), 7–30. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-34022013000300002

DANE. (2024). Encuesta Nacional de Calidad de Vida (ECV) 2024 – Tenencia de la vivienda. https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/condiciones_vida/calidad_vida/boletines/2024/ECV-2024-tenencia.pdf

DANE. (2025). Índice de Precios de la Vivienda Nueva (IPVN) – Boletín técnico, I trimestre 2025. https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/precios/ipvn/boletines/boletin-ipvn-2025-01.pdf

DELGADILLO, V. (2021). Financiarización de la vivienda y de la (re)producción del espacio urbano. Revista INVI, 36(103), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-83582021000300001

DI MASSO, A., VIDAL, T., & POL, E. (2008). La construcción desplazada de los vínculos persona-lugar: Una revisión teórica. Anuario de Psicología, 39(3), 371–385. https://revistes.ub.edu/index.php/Anuario-psicologia/article/view/8418

EL ESPECTADOR. (2025, ABRIL 29). Colombia ya no compra: el arriendo supera por primera vez a la vivienda propia. https://www.elespectador.com/economia/colombia-ya-no-compra-el-arriendo-supera-por-primera-vez-a-la-vivienda-propia/

HURTADO TARAZONA, A. (2018). Habitar como labor material y simbólica: La construcción de un mundo social en Ciudad Verde [Tesis de doctorado, Universidad de los Andes]. Repositorio Universidad de los Andes. https://repositorio.uniandes.edu.co/server/api/core/bitstreams/4230d485-bb8d-4d7c-8730-7fea76f4c6ff/content

GENICOT, G., & RAY, D. (2017). Aspirations and inequality. Econometrica, 85(2), 489–519. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA13865

GIGLIA, A. (2012). El habitar y la cultura: Perspectivas teóricas y de investigación. Anthropos/UAM-Iztapalapa.

GRAEBER, D. (2011). Debt: The first 5,000 years. Melville House.

LAHAUS. (2025). Informe de precios de vivienda nueva en Colombia 2025. https://www.lahaus.com/

LA REPÚBLICA. (2024, 19 DE FEBRERO). El déficit habitacional se cerraría con construcción de cerca de 520.000 casas anuales. https://www.larepublica.co/economia/el-deficit-habitacional-se-cerraria-con-construccion-de-cerca-de-520-000-casas-anuales-3803291

LOMBANA USECHE, Z. V., & RUIZ GÓMEZ, M. P. (2024). El desafío de la vivienda propia, el sueño de las familias colombianas: Avances y retos en la política de vivienda [Trabajo de grado de maestría, Universidad del Rosario]. https://repository.urosario.edu.co/items/54676885-8a3e-4536-b4c9-c708a56e4057

MANIZALES, ALCALDÍA DE. (2017). Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial 2015–2027. Componente urbano: Documento técnico de soporte. https://www.manizales.gov.co/pot-urbano-2015-2027-documento-tecnico

MINISTERIO DE VIVIENDA. (2024). Circular 0012 del 16 de diciembre de 2024. https://minvivienda.gov.co/sites/default/files/normativa/circular-0012-16-12-2024.pdf

MONKKONEN, P. (2011). The housing transition in Mexico: Expanding access to housing. Urban Affairs Review, 47(5), 672–695. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087411400381

NÚÑEZ, M. (2020). La construcción social del habitar: La reproducción del statu quo. Artificio, 26–37. https://revistas.uaa.mx/artificio/article/view/2526

QUENTIN, A. (2023). Vivienda social y gubernamentalidad en América Latina: El acceso a la propiedad privada como proceso de subjetivación política. Heterotopías, 6(12), 1–23. https://revistas.unc.edu.ar/index.php/heterotopias/article/view/43599/43635

RAY, D. (2006). Aspirations, poverty, and economic change. En A. V. Banerjee, R. Bénabou, & D. Mookherjee (Eds.), Understanding poverty (pp. 409–422). Oxford University Press.

ROLNIK, R. (2018). La guerra de los lugares: La colonización de la tierra y la vivienda en la era de las finanzas. Descontrol Editorial.

ROLNIK, R., GUERREIRO, I. DE A., & MARÍN-TORO, A. (2021). El arriendo —formal e informal— como nueva frontera de la financiarización de la vivienda en América Latina. Revista INVI, 36(103), 19–53. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-83582021000300019

SÁNCHEZ URIARTE, P. M., & SALINAS ARREORTUA, L. A. (2023). Deuda hipotecaria y vida cotidiana en Nicaragua y México. Revista geográfica venezolana, 64(2), 301–319. http://erevistas.saber.ula.ve/index.php/regeoven/article/view/19708

STILLERMAN, J. (2017). Housing pathways, elective belonging, and family ties in middle-class Chileans’ housing choices. Poetics, 61, 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2017.01.005

UN-HABITAT. (2020, 31 OCTUBRE). Addressing the housing affordability challenge: A shared responsibility. https://unhabitat.org/news/31-oct-2020/addressing-the-housing-affordability-challenge-a-shared-responsibility

ZAMORANO, C. (2007). Vivienda y familia en medios urbanos: ¿Un contenedor y su contenido? Sociológica, 22(65), 159–187. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3050/305024744007.pdf

Gregorio Hernández-Pulgarín

PhD in Urban Planning and Land Use (École d'Urbanisme de Paris); Master's in Anthropology (Université de Bordeaux); Anthropologist (University of Caldas) and Business Administrator (National University of Colombia). Full professor, Department of Anthropology and Sociology, and leader of the Territorialities Research Group at the University of Caldas. His research focus on narratives on the crisis and rebirth of cities, housing, and urban mobility, as well as on different topics in urban anthropology and city management.

Geraldine Buitrago Rodas

Thesis student in Anthropology at the University of Caldas. Member of the Terranova research group. She has worked as a fellow in academic and research processes, strengthening her research training. Her interests include urban anthropology, territorial and urban studies, as well as reflection on housing, space, and community life in urban contexts.

Autor

aspirations, appropriation, and the market

Housing as a socio-material artifact in Manizales:

aspirations, appropriation, and the market

aspirations, appropriation, and the market

This purpose is developed from three perspectives related to the issue of housing. The first (anthropological) perspective examines housing as a life project and territory of intimacy (use value) and as a symbol of achievement and intra-family "moral debt" (symbolic value). The second (urban planning, with an emphasis on economic ) analyzes the determinants of exchange value: prices and costs (materials, land, and urbanization), rates and credit, subsidies and regulation, as well as the geomorphological rigidities that restrict land use. The hypothesis we propose as the basis for this article is that these three dimensions of value coexist and are interdependent.

aspirations, appropriation, and the market

aspirations, appropriation, and the market

aspirations, appropriation, and the market

aspirations, appropriation, and the market

Image 1. Overview of new and rental housing 2023 and 2024

Source: La República (2024).

aspirations, appropriation, and the market

Table 1. Expressions related to exchange value

Source: Own elaboration based on interviews.

|

Subcategory |

Illustrative citations |

|

Refuge, intimacy and security |

“My house is my favorite place in the world”; “My house is my HQ, it’s everything to me”; “It’s sort of a sacred place where one can arrive, where one rests”; “Houses are human being’s refugee”. |

|

Wellbeing, autonomy and identity |

“You’ve got freedom for the space, for the color”; The house was made accordingly to my taste because my disability was always considered”, “Emancipation has to do with space”, “As a symbolic matter, this is mine and I want it to have my traces”. |

|

Spaciousness and functionality |

“I dream about a big house, a big house with a big green space”; “Spaces don’t need to be gigantic to be appreciated, but they mustn’t be 30m2 for four people”; “A spacious kitchen is something you don’t see anymore. Apartments the size of a match box”. |

|

Personalization and appropriation |

“The first thing we did was painting the rooms; I wanted it to have my mark”; “When something belongs to one, one appreciates every space”; “Choosing the colors, the wood… designing it accordingly to your own taste”. |

|

Environment’s quality and location |

“The zone, the location is very good, very strategic”; “I want to live in a place where I can go out buy bread and walk calmly”; “The dishwasher had a nice view of the mountains, that is very relaxing”. |

|

Overcoming habitational scarcity |

“In a room with very scarce conditions that had not toilet”; “I dreamt of having a better house than the one I had because the one I lived in was very scarce”; “Feeling safe in a place, that’s what finding a house means”. |

aspirations, appropriation, and the market

Image 1. Words associated with symbolic value

Source: Own elaboration based on interviews.

aspirations, appropriation, and the market

aspirations, appropriation, and the market

aspirations, appropriation, and the market