CALVIN & HOBBES CHASE THE MURDERER: ATYPICAL SOLUTION TO A CASE OF TRACE EVIDENCE IN A LABORATORY. CASE REPORT

National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences, Special Edition

Jairo Peláez Rincón

National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences.

Evidence Group Traza.

- Bogotá Office -

- Bogotá, D.C. - Colombia.

Correspondence to:

Jairo Peláez Rincón.

Evidence Group Traza,

National Institue of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences.

Bogotá, D.C. Colombia.

Email: jpelaez@medicinalegal.gov.co

SUMMARY

This is the case of a typical request for a chemical laboratory analysis to conduct a comparison of materials or trace evidence with completely unexpected results from those obtained if established protocols had been followed.

This request involved the collation of black gunpowder, a material which is generally associated with firearms. In this case, however, the prosecutor’s request was to compare the powder from two groups of paper used in tejo (a popular Colombian sport) in order to ascertain the identity of a homicide suspect at the scene of the crime.

Keywords: Trace evidence; Scientific method; Class characteristic; Individual characteristic.

INTRODUCTION

Trace evidence laboratories specialize in the analysis and comparison of transferred material according to the principle of Lockard, which includes paints, textile fibers, soil, glass fragments and fire accelerants, among others. One of the most important features of this type of work is that it is not routine, since analysts in this area of forensic sciences know that at any moment they will have to handle atypical requests or approach a case in unorthodox ways. These cases often conflict with the scientific method, but can also provide solutions to forensic problems that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to solve.

A procedure like the one presented here is a big departure from what we can consider the rigorous scientific method. However, it maintains a certain research logic that must be acknowledged when evaluating the practical results of the case.

Knowledge is a collection of information compiled and stored using a process — such as learning or experience — to fix it in the mind. The scientific method is a set of rules, organized and coherent, which allow the systematized acquisition of this knowledge, regardless of whether the truth is obtained or not; however, it is not the only way to arrive at the same objective.

There is a common “urban myth” in the judicial system that any conclusion that was formed without rigorously following the scientific method is not serious, and therefore lacks validity. In an article published in 1999, Max Houck proposed the impossibility of applying the powerful statistical tools used in the field of genetics to the world of trace evidence (1); an impossibility that doesn’t invalidate the results obtained by the discipline’s own methods. While science searches for methods that are increasingly more reliable, humankind cannot deny the fact that we live in a universe with uncertainty at its core, which is therefore a constancy we must live with.

BACKGROUND

Tejo is a traditional sport in Colombia that dates back to pre-Colombian times. It has origins in the current regions of Boyocá and Cundinamarca, where it later extended to other corners of the country and neighboring countries such as Panama, Venezuela, Ecuador and Peru.

In very general terms, the game consists of throwing a metal disc at a board made from clay on which various pieces of paper folded into triangle shapes and filled with black gun powder (known in Spanish as mechas and referred to as such in this article) are placed; the goal is to hit and burst the largest number of these mechas to win the game.

It is rare to have this particular material sent to criminal laboratories for comparison, which is what makes the nature of this request highly atypical and interesting.

SCENARIO

In a field used to play tejo in Bogota, D.C., in 2006, an argument between two players occurred, one of whom was subsequently the victim of a homicide. The murderer fled the scene, but police located a suspect who denied having been at the scene. During this phase of the police investigation, 14 pink-colored mechas used to play tejo were found in the house of the suspect; the prosecutor assigned to the case thought that a link could be found between the detainee and the crime scene if the powders from these mechas were compared with those found in the playing field. Thus, two packages arrived at the laboratory: one containing the 14 mechas found at the suspect’s home and the other with 10 mechas from the playing field.

APPROACH TO THE CASE

Powder comparison is not a service provided by the Evidence Trace Laboratory of Legal Medicine, and in fact, in all its history, this has been the only time such a request has been made. In light of this unprecedented request, the analytical focus went beyond established procedures, but the attempt was made nonetheless to conduct a comparison without any guarantee of providing useful results to the prosecutor.

The laboratory infrastructure at that time did not have adequate technology such as scanning electron microscope, so only an infrared spectrum and elemental analysis could be obtained, which is why little can be said of the morphology of powder particles. The analysis focused instead on the possible exclusion of samples so that the laboratory could establish with certainty if the mechas were different, rather than establishing a relationship between them that could place them at the scene.

For ease in data recording, the mechas found in the home were marked with the letter H and those taken at the playing field were marked with the letter C.

Initially, a description was made of each mecha in the laboratory. These products are manufactured by hand, so the measurements of the dimensions of each mecha along with the powder content were of little use, although one of them, marked as H14, presented a pink tonality that was different than the others.

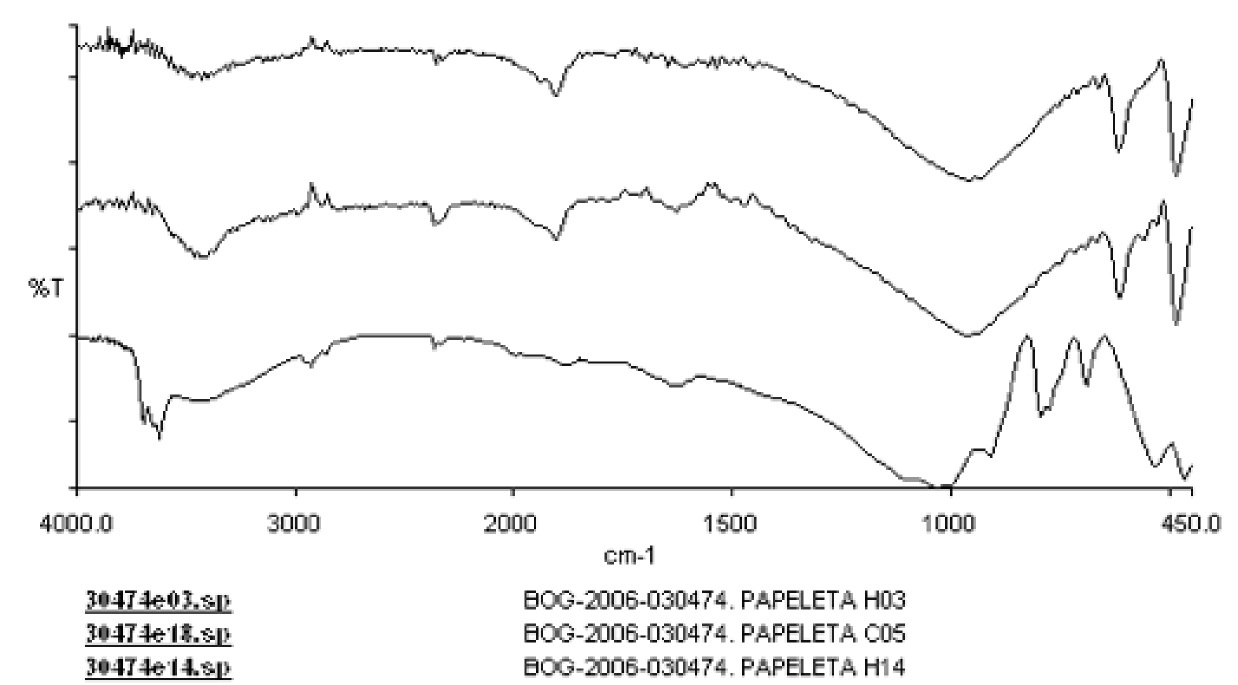

Subsequently, the infrared spectrum of the powder contained in each paper was measured using the FTIR Perkin-Elmer System 2000 spectrophotometer with a resolution of 4cm-1. The spectrum obtained was similar in all samples except, once again, H14.

Fig 1. Infrared spectrum of material taken from mechas H-03, C-05 and H-14.

Source: I. Author.

The lack of any available databases or previous studies regarding the composition of powder used in tejo increases the difficulty in evaluating the evidential weight of this result; however, the analytical technique led to the exclusion of one of the mechas found in the suspect’s home.

During the process of obtaining the content of the powder of every mecha in the laboratory, it was noted that all of them had the following architecture: an external wrapping consisting of thick printed paper with pink, red and yellow colors; some of them had incomplete words and graphics alluding to soccer as they were taken from an album of a soccer world championship. A second wrapping, containted in the previous one, which, in turn, containts the powder. in all the cases, this second wrapping consisted of newsprint. At this point the analysis experienced a surprising turn of events.

If the seized mechas had in fact come from the playing field, was it possible that all or some of them had come from the same production batch, and had therefore used the same newspaper and sports album in their production?

At this moment, the case deviated from the chemical approach and focused instead on verifying or rejecting a hypothesis that did not require any technical or scientific study.

The next step was then to completely disassemble the papers, taking care to conserve the nomenclature assigned to each of them. Then, each paper was cleaned individually and the typographic content was registered, both on the external wrapping and the pieces of newsprint.

All of the external wrappings in both H and C groups, with the exception of H14, alluded to topics of soccer (balls and players).

As for the internal wrappings, most corresponded to the section of classified ads and judicial decrees of a Bogotá newspaper. However, some select pieces of newsprint provided more promising information:

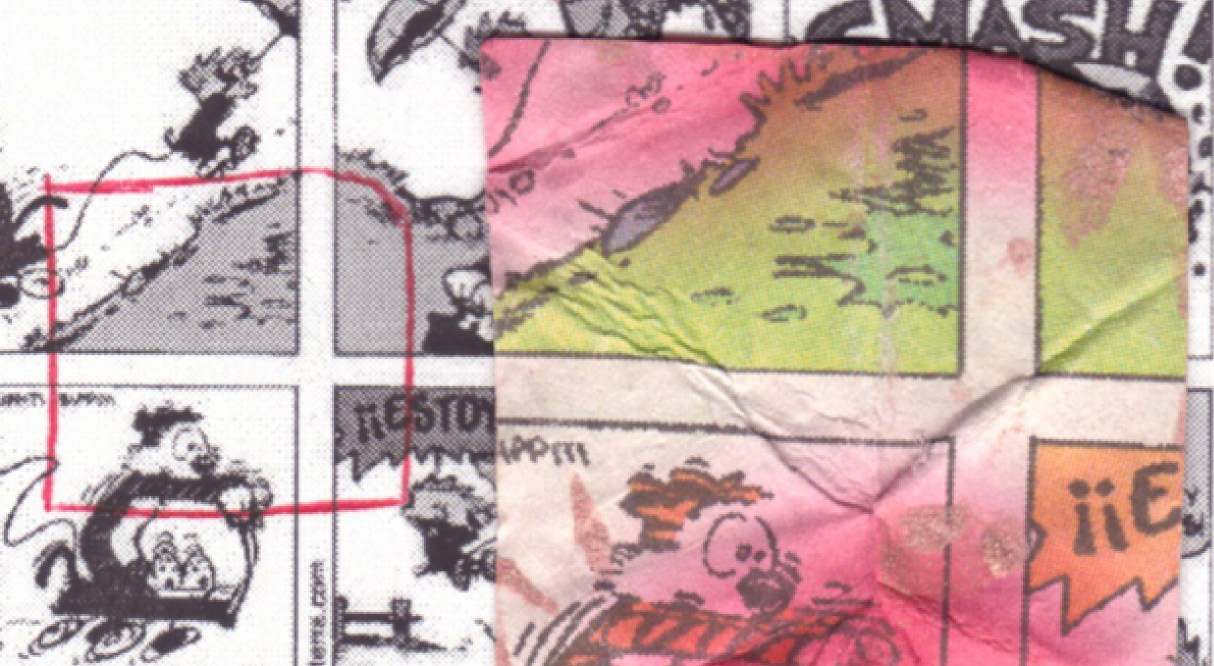

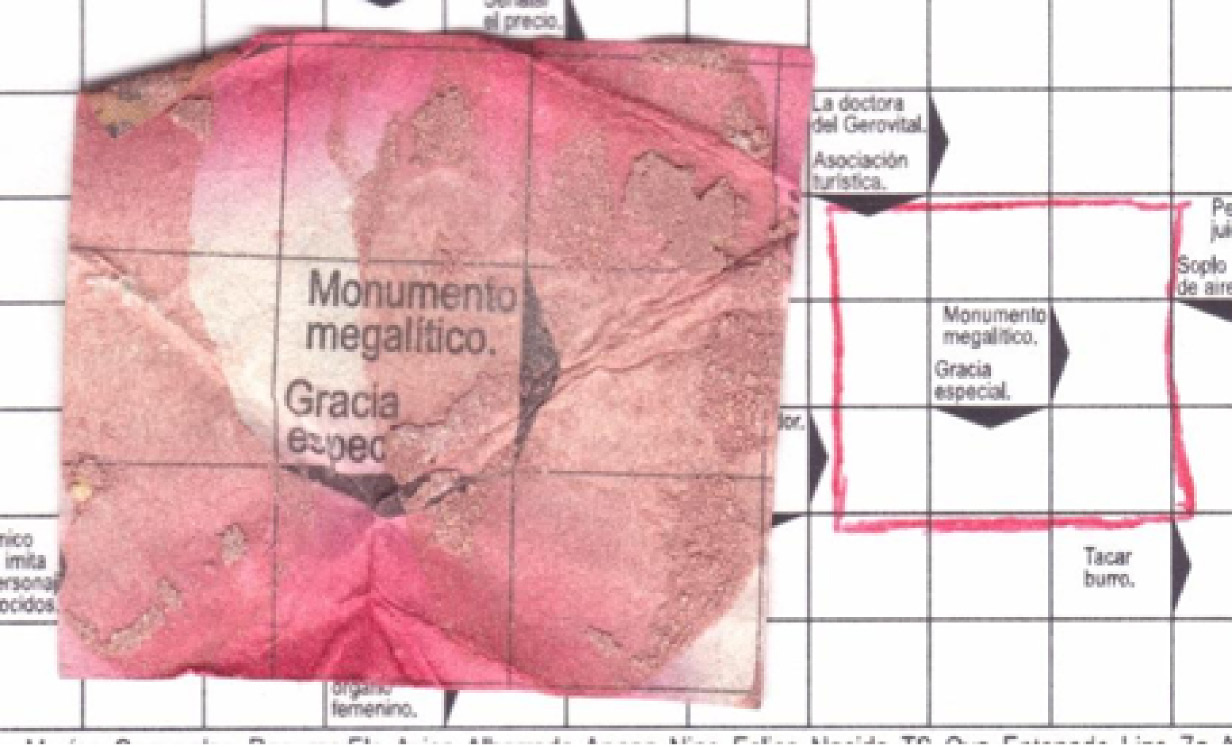

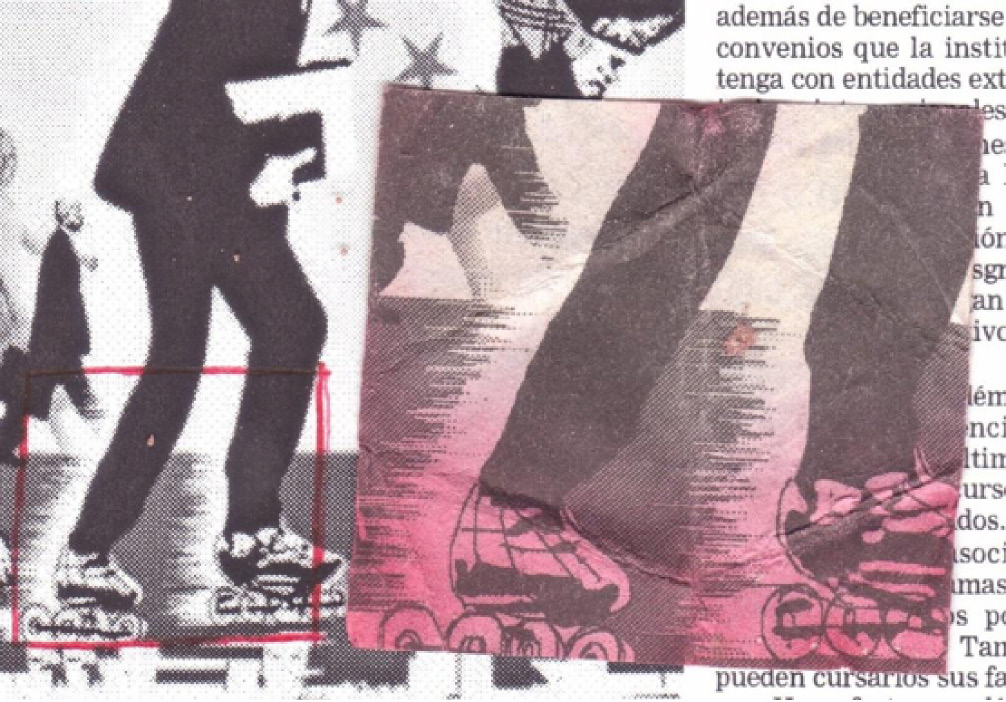

• H-03: On one side, the color print of comic character Hobbes of the comic strip Calvin and Hobbes by American cartoonist Bill Watterson. On the other side was part of a crossword with the following inscription in the central square: “Megalithic monument. Special grace” (Spanish original: Monumento megalítico. Gracia especial).

• H-10: Inscription “El Tiempo”

• H-11: Inscription “The New York Times”

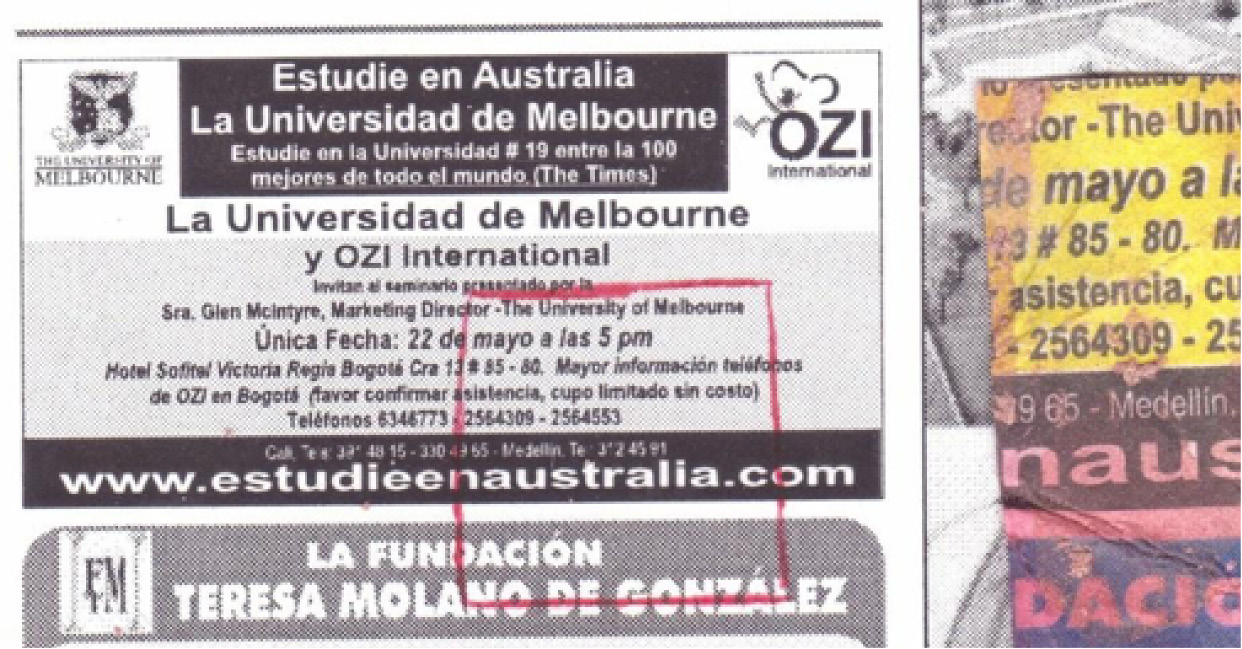

• C-05: On one side, part of an illustration corresponding to a pair of feet in skates with a world map design. On the other side, with a yellow, black and blue background, the inscription “[...] The University of Melbourne [...] of May at 5pm [...] 13 nº 85-80 [...] For more information phone [...] attendance, limited availability free of charge [...] -2564309-2564552- 9 65 […] Medellín. Tel 3124 […] naustralia. co […] dación […] no de Gonzál […]” (Spanish original: “[…] The University of Melbourne […] de mayo a las 5 pm […] 13 nº 85-80 […] Mayor información telefon […] asistencia, cupo limitado sin costo […]-2564309-2564552-9 65 […] Medellín. Tel 3124 […] naustralia.co […] dación […] no de Gonzál […]”)

• Paper C-06: Inscription “valid until [...] June 30, 2006.” (Spanish original: […] erta válida hasta […] nio 30 de 2006”)

All the previous mechas were photocopied and brought to the headquarters of the newspaper El Tiempo in Bogotá, where access to the editorial archives was requested.

H-03, containing The Calvin and Hobbes strip, was printed in color and matched a Sunday edition of the newspaper, which restricted the search to Sunday editions, within a timeframe of six months before the crime.

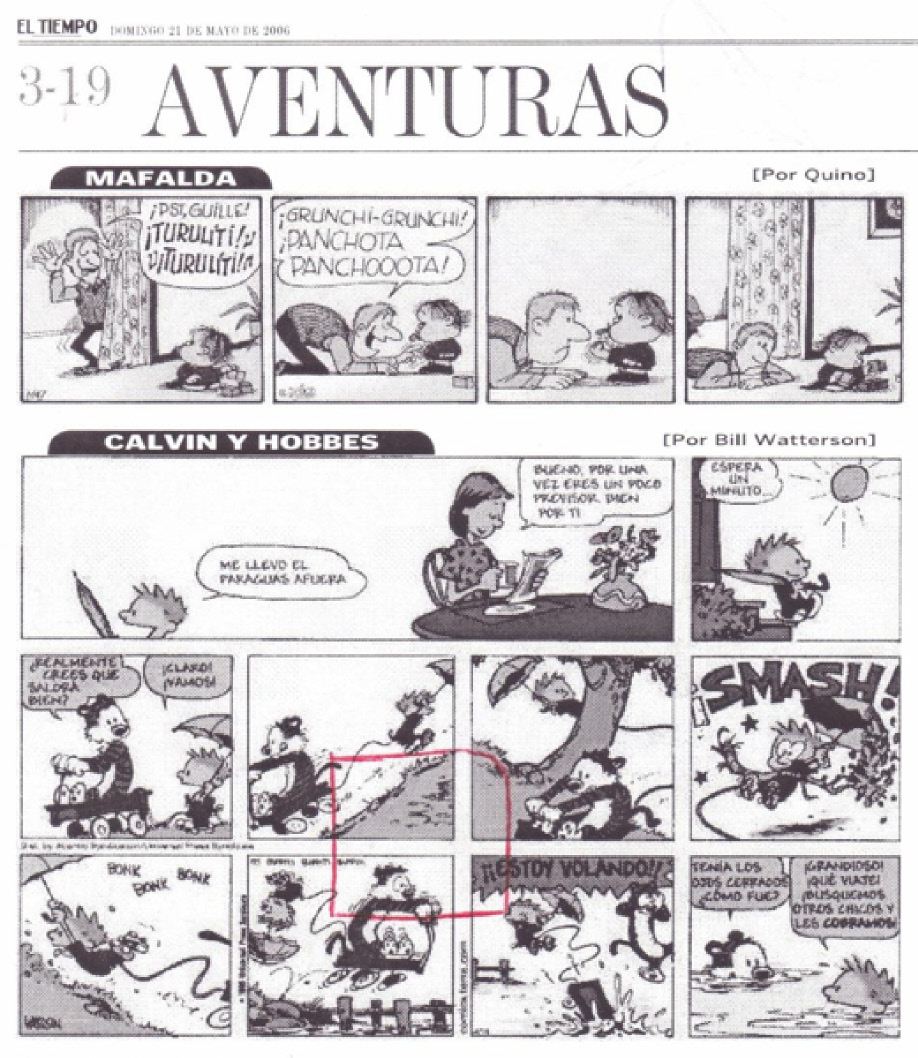

The search uncovered the Calvin and Hobbes strip matching H-03, published on May 21st, 2006, page 3-19 (2).

Fig 2. Newspaper fragment taken from the interior of H-03, found in the bedroom of the suspect, superimposed on a black and white copy of page 3-19 of the newspaper El Tiempo, matching the May 21st, 2006 edition.

Fig 3. Fragment of page 3-19 of El Tiempo, matching the May 21st, 2006 edition.

Fig 4. Newspaper fragment taken from the interior of H-03, found in the suspect’s bedroom, superimposed on a copy of page 3-20 of the newspaper El Tiempo, matching the May 21st, 2006 edition.

Page 3-20, as was expected, contained the crossword evidenced on the other side of the newspaper fragment of H-03.

Fig 5. Fragment of page 3-15 of the May 21st, 2006 edition of El Tiempo.

Fig 6. Newspaper fragment taken from the interior of C-05, found in the tejo playing field, superimposed on a copy of page 3-15 of the newspaper El Tiempo of the May 21st, 2006 edition.

Fig 7. Newspaper fragment taken from the interior of C-05, found in the playing field, imposed on a copy of page 3-16 of the newspaper El Tiempo of the May 21st, 2006 edition.

Searches were also conducted for the information contained on C-05 and C-09: C-05 was found in pages 3-15 and 3-16, while C-09 was not found. See details of the date in Figure 6. Undoubtedly, the results obtained in this case show a link between both groups of papers studied. The suspect’s story in which he was not present at the scene of the crime loses validity faced with the fact that mechas made with the same edition of the newspapers and soccer album were found in his home and on the playing field. The mere result of the chemical analyses of the two groups of black gunpowder involved in the case would not have had the same evidential weight since the production of black gunpowder is mass manufactured by relatively few providers.

In technical terms, the information obtained through infrared spectroscopy in the present case is considered a class characteristic. This is a characteristic that does not reference a particular individual (3), while information contained in the wrappings of the mechas can be considered individual characteristics because, most likely, only a small fraction of the mechas made in the city used the same two editions out of a multitude of publications circulating in the city as wrapping.

CONCLUSION

This report illustrates the fact that many forensic cases, including those of trace evidence, can be solved using a logical framework. Sometimes the framework that is chosen by the laboratory, accepted by the scientific community and submitted to quality control systems, do not yield the best results nor are they the most time-efficient. In cases such as this one, the immediacy of proof and common sense prevent the laboratory from undertaking complex, prolonged and costly verification processes in a request that could quite possibly be unique.

FINAL COMMENT

Quality management systems in forensic institutions and the legal community that benefits from these institutions need to take into account the complex nature of pieces of evidence and their relationships with a scene and / or their actors. This can determine solutions to questions generated by facts that often deviate from the officially approved and established frameworks. There should be a logic behind these alternate paths that establishes a coherence between the results obtained and the initial problem. This is a logic that guarantees that, when such a request occurs again, this analytical framework can be employed and added to the rigorous systems of laboratory quality control.

REFERENCES

1. Houck M. Statistics and Trace Evidence: The Tyranny of the Numbers. Forensic Science Communications. 1999 [cited 2014 May 24];1(3). Available from: https://goo.gl/VHXCAS.

2. El Tiempo. 2006 May 21.

3. Kiely TF. Forensic Evidence: Science and the Criminal Law. Boca Ratón: CRC Taylor & Francis Group. 2006