DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/innovar.v26n62.59385

The Relationship between Managerial Skills and Managerial Effectiveness in a Managerial Simulation Game1

RELACIÓN ENTRE LAS HABILIDADES GERENCIALES Y LA EFICACIA EN LA GESTIÓN EN UN JUEGO DE SIMULACIÓN GERENCIAL

RELAÇÃO ENTRE AS HABILIDADES GERENCIAIS E A EFICÁCIA NA GESTÃO NUM JOGO DE SIMULAÇÃO GERENCIAL

LES RAPPORTS ENTRE LES COMPÉTENCES MANAGÉRIALES ET L'EFFICACITÉ DANS LA GESTION DANS UN JEU DE SIMULATION DE GESTION

Petr SmutnyI, Jakub ProchazkaII, Martin VaculikIII

1 This paper is part of the research "Effective leadership: An integrative approach". The research has been funded by Czech Science Foundation (P403/12/0249).

I Ph.D. in Corporate Economy and Management, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

e-mail: petr.smutny@econ.muni.cz

ORCID link: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2758-067X

II Ph.D. in Social Psychology, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

e-mail: jak.prochazka@mail.muni.cz

ORCID link: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6386-1401

III Ph.D. in Social Psychology; Habilitation in Social and Work Psychology, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

e-mail: vaculik@fss.muni.cz

ORCID link: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8901-5855

Citación: Smutny, P., Prochazka, J., & Vaculik, M. (2016). The Relationship between Managerial Skills and Managerial Effectiveness in a Managerial Simulation Game. Innovar, 26(62), 11-22. doi: 10.15446/innovar.v26n62.59385.

Clasificación JEL: M12, M50, O15.

Recibido: Enero 2014, Aprobado: Julio 2015.

Abstract:

The study explores the relationship between managerial skills and managerial effectiveness, measuring managerial effectiveness by four different methods. Evaluation of 96 top managers of fictitious companies by a group of 1,746 subordinates took place after three months of intensive cooperation during a managerial simulation game. All respondents were college students. Results show that different managerial effectiveness indicators have different sets of managerial skills predictors: Group performance (profit of company) is predicted by motivational skills; perceived effectiveness (evaluation by subordinates) is predicted by organizational skills and by motivational skills; organizational skills, communicational skills, and cooperativeness predict leadership emergence (assessed by subordinates); and evaluation and supervisory skills are the only predictor for leadership self-efficacy (self-evaluation of the manager). According to the results it is possible to recommend focusing especially on manager's motivational skills in order to enhance team performance and on organizational skills for reinforcing manager's position.

Keywords: Managerial skills, managerial effectiveness, leadership emergence, group performance, managerial simulation game.

Resumen:

Este estudio explora la relación entre las capacidades gerenciales y la eficacia en la gestión, siendo esta última evaluada a través de cuatro métodos diferentes. Con este fin, se realizó la evaluación de 96 altos directivos de empresas ficticias por parte de un grupo de 1.746 subordinados involucrados durante un periodo de tres meses en un juego de simulación gerencial. Todos los participantes eran estudiantes universitarios. Los resultados muestran que los diferentes indicadores de eficacia dan cuenta de distintos conjuntos de predictores de habilidades gerenciales: el desempeño del grupo (ganancias para la organización) puede ser analizado a partir de las habilidades motivacionales; la efectividad percibida (evaluación por parte de los subordinados) se encuentra relacionada con las capacidades organizacionales y motivacionales; a su vez, las capacidades organizacionales, las habilidades de comunicación y de cooperación, conducen al surgimiento de liderazgo (evaluada por los subordinados); por su parte, las capacidades de evaluación y supervisión son el único indicador de la auto-eficacia del liderazgo (autoevaluación del gerente). De acuerdo con los resultados, se puede llegar a recomendar dar mayor importancia a las habilidades motivacionales del gerente para efectos de mejorar el desempeño del equipo, así como a las capacidades de la organización para reforzar el rol de gerente.

Palabras-clave: capacidades gerenciales, eficacia en la gestión, surgimiento del liderazgo, desempeño de grupo, juego de simulación gerencial.

Resumo:

Este estudo explora a relação entre as capacidades gerenciais e a eficácia na gestão, sendo esta última avaliada por meio de quatro métodos diferentes. Com esse objetivo, realizou-se a avaliação de 96 altos diretores de empresas fictícias por parte de um grupo de 1.746 subordinados envolvidos durante um período de três meses num jogo de simulação gerencial. Todos os participantes eram estudantes universitários. Os resultados mostram que os diferentes indicadores de eficácia dão conta de diferentes conjuntos de preditores de habilidades gerenciais: o desempenho do grupo (lucro para a organização) pode ser analisado a partir das habilidades motivacionais; a efetividade percebida (avaliação por parte dos subordinados) se encontra relacionada com as capacidades organizacionais e motivacionais; as capacidades organizacionais, as habilidades de comunicação e de cooperação, por sua vez, conduzem ao surgimento de liderança (avaliada pelos subordinados); as capacidades de avaliação e supervisão são o único indicador de autoeficácia da liderança (autoavaliação do gerente). De acordo com os resultados, pode-se recomendar dar maior importância às habilidades motivacionais do gerente para efeitos de melhoria do desempenho da equipe, bem como às capacidades da organização para reforçar o papel do gerente.

Palavras-chave: capacidades gerenciais, eficácia na gestão, surgimento da liderança, desempenho de grupo, jogo de simulação gerencial.

Résumé:

Cette étude explore la relation entre les compétences de gestion et l'efficacité de la gestion. Celle-ci a été évaluée en utilisant quatre méthodes différentes. À cette fin, un groupe de 1.746 subordonnés, impliqués sur une période de trois mois dans un jeu de simulation de gestion, a mené l'évaluation de 96 cadres supérieurs de sociétés fictives. Tous les participants étaient des étudiants. Les résultats montrent que les différents indicateurs de performance réalisent différents ensembles de facteurs prédictifs de compétences managériales : la performance du groupe (des bénéfices pour l'organisation) peut être analysée à partir des compétences de motivation ; l'efficacité perçue (évaluation par des subordonnés) est liée aux compétences organisationnelles et de motivation ; à leur tour, les compétences organisationnelles, les compétences de communication et de coopération conduisent à l'émergence d'un leadership (évalué par les subordonnés) ; d'autre part, les compétences d'évaluation et de surveillance sont le seul indicateur de l'auto-efficacité du leadership (auto-évaluation du manager). Selon les résultats, on peut recommander d'accorder une importance plus grande aux compétences de motivation du manager dans le but d'améliorer la performance et les capacités de l'organisation de l'équipe, pour renforcer le rôle du manager.

Mots-Clé: compétences en gestion, gestion efficace, émergence du leadership, performance du groupe, jeu de simulation managériale.

Introduction

Companies invest heavily in searching for the right people to fill managerial positions and in subsequent development of managers since they influence business results (Vaculík, 2010). For example, Joyce, Nohria and Roberson (2003), reported that CEOs account for about 14% of the variance in firm performance. Individual characteristics of a manager such as gender, skills and abilities and personality traits, predict future firm, team or leader effectiveness (DeRue, Nahrgang, Wellman & Humphrey, 2011). Prospective employers try to hire new effective managers and develop their current managers to be more effective. Competence models used in recruitment contain sets of these possible predictors determining managerial success/effectiveness (Brownell, 2008). Many studies describe the relation between managerial competencies or managerial skills and managerial/leader effectiveness. These studies usually focus on a set of skills and one type of managerial/leader effectiveness indicator (Analoui, 1999; Analoui, Ahmed & Kakabadse, 2010; Nwokah & Ahiauzu, 2008). Feng-Jing and Avery (2008) consider the use of only one type of effectiveness indicator as inadequate and insufficient, they recommend the use of both financial (e.g. profits) and non-financial measurements (e.g. assessment by employees) of effectiveness to enhance the validity of research. A complex model, which includes a full set of managerial skills and various indicators of effectiveness, can completely describe the connection between these skills and managerial effectiveness. Therefore, the present study uses a model of five managerial skills and four frequently used managerial effectiveness indicators in a standardized environment of a managerial simulation game and searches for connections between them. The goal of this research is to identify important skills for the meaningful selection and development of an effective future manager.

Some studies about managerial skills and managerial effectiveness use different terms than managerial skills and managerial effectiveness. Managerial skills are sometimes included as a part of managerial competencies (Abraham, Karns, Shaw, & Mena, 2001; Bradford, 1983; Heffner & Flood, 2000; Levenson, Van der Stede & Cohen, 2006; Pickett, 1998; Tett, Guterman, Bleier & Murphy, 2000; Zhong-Ming, 2003) or are considered as a part of leader or leadership competencies (Botha & Claassens, 2010; Emiliani, 2003; Hollenbeck, McCall & Silzer, 2006). Some authors use the specific terms managerial effectiveness or managerial performance (Abraham et al., 2001; Analoui, 1999; Analoui et al., 2010; Cavazotte, Moreno & Hickmann, 2012; Tsui & Ohlott, 1988). Others use the less specific terms leader or leadership effectiveness even if they have managers as the participants in their studies (Anderson, Krajewski, Goffin & Jackson, 2008; Bruno & Lay, 2008). For this study we use uniform terms managerial skills and managerial effectiveness because of comprehensibility of the text. Our study is about leaders who hold a formal managerial position and we focus on their skills and not on the other parts of managerial/leader competencies (i.e. knowledge, attitudes and other characteristics; see below).

Managerial Effectiveness Indicators

Managerial effectiveness can be described from various perspectives. A manager is effective if (a) the group he/she manages is effective (Elenkov, 2002; Rice & Chemers, 1973; Riggio, Riggio, Salinas & Cole, 2003; called group performance or managerial performance); (b) other people consider the manager to be effective (Anderson et al., 2008; Foti & Hauenstein, 2007; Ng, Ang & Chan, 2008; Riggio et al., 2003 —often called perceived effectiveness or perceived managerial/leader effectiveness); (c) the manager assess him/herself as effective manager/leader (Ng et al., 2008 —called leadership self-efficacy); and if (d) the manager sets a good example of behavior and can convince people that he/she is a competent leader (referred to as leadership emergence).

Feng-Jing and Avery (2008) differentiate between financial (e.g. group performance) and nonfinancial measurement of effectiveness (e.g. perceived effectiveness). Additionally, Eagly, Karau and Mighijany (1995) state that the most common methods for evaluating leader effectiveness are subjective evaluation of leader's performance (by superiors, subordinates, peers or him/herself), subordinates' subjective evaluation of their satisfaction with a leader, and measuring group and corporate productivity.

Productivity or group performance is an objective criterion. A manager in charge of a more productive group typically appears more effective because his/her group is more effective. However, evaluating managerial effectiveness by group performance is risky since multiple variables affect group performance, not only the leader (Eagly et al., 1995). Even groups with ineffective managers can achieve excellent group performance, for example, thanks to the unique knowledge or skills of one of its members or the legacy of a previous manager.

In comparison with group performance, subjective evaluation of a manager by subordinates, superiors, or independent assessors puts more emphasis on manager's personality. Subjective evaluation also takes into account behavior, which affects both present and future group performance. However, biased observation by the assessor, for example, due to previous experience, prejudice or affection/antipathy to manager's personality, may distort the perception of his/her effectiveness (Eagly et al., 1995). Halo effect, central tendency and social desirability may influence perceived effectiveness (Bass & Avolio, 1989).

The term leadership efficacy or leadership self-efficacy relates to self-evaluation by a person in the role of leader. Managers are expected to fulfill the leadership role and to lead their teams. Murphy (1992) and Hoyt, Murphy, Halverson and Watson (2003) describe leadership self-efficacy as trust in one's ability to lead. Ng et al. (2008) see self-efficacy as one's own perceived capabilities to effectively accomplish the role of leader. Such self-evaluation may become distorted due to insufficient detachment, attributed mistakes or a limited facility to observe the influence of one's behavior towards subordinates. Another drawback of leadership self-efficacy compared to perceived effectiveness is that the manager is the only assessor of him/herself. Despite these limitations, leadership (self)-efficacy positively correlates with perceived effectiveness (Hoyt et al., 2003). The research of Ng et al., (2008) looked into effectiveness of military leaders based on leader evaluation by superiors, and revealed a weak positive correlation between leadership (self-)efficacy and perceived effectiveness (r = 0.27, p < 0.01). The correlation between leadership (self-)efficacy and group performance remains unconfirmed (Hoyt et al., 2003).

The effectiveness of managers also depends on whether their subordinates/colleagues consider them to be leaders. If the position of manager is only formal, then subordinates have to obey, but their manager is not a leader for them, only a person with formal authority. If subordinates perceive their manager as a leader with genuine authority, then they tend to follow him/her. In this way, the evaluation of managers is in fact the evaluation of their ability to fulfill the leadership role. Perceiving a person as a leader relates to the concept of leadership emergence. Hogan, Curphy and Hogan (1994) describe emergent leadership in situations where a group perceives an individual as a leader, even though the group has limited information about that individual's performance. Other studies link leadership emergence with evaluating the influence of a group member on the group (Foti & Hauenstein, 2007) or with choosing somebody as a leader (Garland & Beard, 1979; Rice & Chemers, 1973; Riggio et al., 2003).

Of these four managerial effectiveness indicators, group performance is the most objective, perceived effectiveness focuses primarily on external behavior, while leadership self-efficacy also takes into account implicit intentions and consequences of manager's behavior, which are not easily observable. In comparison with the other indicators, the use of leadership emergence as an indicator of managerial effectiveness poses the greatest number of problems. However, we contend that this specific indicator offers an important view of leadership and enriches the view of effectiveness, not just in terms of economic performance but in other dimensions as well.

The four managerial effectiveness indicators described here are not independent. Positive changes in employee evaluations lead to positive changes in group performance (Feng-Jing & Avery, 2008). However, each of these indicators offers a specific view of effectiveness (DeRue et al., 2011; Yukl, 2008). Combining a variety of perspectives may be an ideal way to evaluate managerial effectiveness as the combination of indicators helps to avoid erroneous generalizations (Lord, Devader & Alliger, 1986).

Relationship between Managerial Skills and Managerial Effectiveness

Managerial skills are a subset of managerial competencies. The structure and level of individual competencies influence activities in a company and its overall corporate culture. Competencies on an individual level also influence the effectiveness of the entire organization (Cardy & Selvarajan, 2006). For example, Hogan and Kaiser (2005) list managerial competencies as one of five components influencing organizational effectiveness.

Competence models usually encompass the total of what people can do and what they know (Antonacopoulou & Fitzgerald, 1996). Individual models include various abilities, skills, knowledge, personality features, attitudes and other characteristics individually tailored or necessary for a specific position (Abraham et al., 2001; Agut, Grau & Peiro, 2003; Chong, 2008; Cizel, Anafarta & Sarvan, 2007; Drucker, 2005; Goleman, 2000; Hamlin, 2004; Harison & Boonstra, 2009; Hogan & Kaiser, 2005; Man, Lau & Chan, 2002; Mumford et al., 2000; Patanakul & Milosevic, 2008; Riggio & Lee, 2007). While some positions or factors require their own exclusive models, there is another group of generic models, which are transferable between individual work positions and organizations. In the 1980s (Dulewicz, 1989), as well more recently, a prevalence of generic models has arisen, which, apart from better adaptability, bring further advantages (Hollenbeck et al., 2006; Mansfield, 1996). Conducting comparative research of studies into the criteria of managerial effectiveness, Hamlin (2004) supported the view that universalistic models are more consistent with the facts than contingent models.

Managerial skills, a part of managerial competency models, are only sometimes linked with the managerial, leader or group effectiveness (Analoui, 1999; Waters, 1980). There is still a lack of studies, which confirm the relation between specific skills and several different effectiveness indicators. Avolio and Waldman (1989) showed a correlation between the perceived importance of four managerial skills (planning/controlling, human relations, subsystem representation, and communication) and the level of the manager in the organizational hierarchy. However, the level in the organizational hierarchy is not an ideal indicator of managerial effectiveness because it can be a consequence of various situational factors. Analoui, Labbaf and Noorbakhsh (2000) reveal three sets of skills which are related to managerial effectiveness, including people-related skills (i.e. motivation, counseling subordinates), task-related skills (i.e. planning, analysis of the organization) and analytical and self-related skills (i.e. managing change, developing own potential). However, they did not link their set of skills to concrete managerial effectiveness indicators. The relation between particular skill and an effectiveness indicator can be different if we use different indicator. For example, Riggio et al. (2003) confirmed that people with a higher level of communication skills are assessed as better leaders yet the same communication skills do not predict group productivity. Even though these authors studied two different indicators of effectiveness, they focused on just one managerial skill.

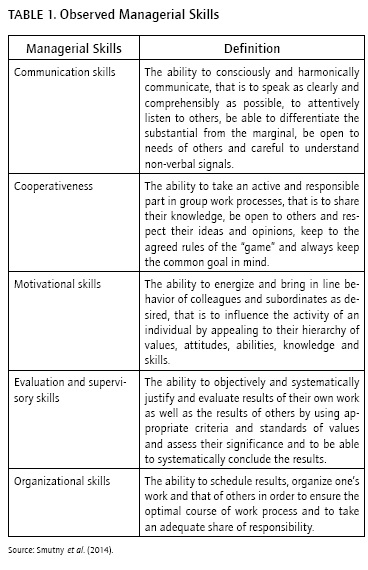

This study involves verifying the predictive ability of the set of typical managerial skills from a generic competence model (Table 1). Smutny, Prochazka and Vaculik (2014) derived the model used in this study from Mintzberg's (1975) managerial roles by a "job focus" method (Russ-Eft, 1995). They verified the model validity using a comparison with employer requirements for managerial candidates. The model covers a similar range of managerial skills as does the model used by Analoui et al. (2000). It is used for managerial skill development of business students during a managerial simulation game (Smutny et al. 2013). We use a managerial simulation game in this study as a standardized research environment that is why we use this model as well.

Method

Research Question and Hypothesis

The objective of this study is to find which individual managerial skills (defined in Table 1) are predictors of managerial effectiveness. This study explores the following question: Does the level of managerial skills relate to managerial effectiveness indicators?

Our assumption is that a managerial skill is a skill which managers use in their work and that allows them to do their job more effectively (Cardy & Selvarajan, 2006). Studies by Analoui et al. (2000), Riggio et al. (2003), and Avolio and Waldman (1989) provide a partial support for the existence of relationships between the most commonly used managerial skills and some indicator of effectivity. We test the hypothesis that the levels of communication skills, motivational skills, organizational skills, evaluation and supervisory skills and cooperativeness of a manager relate to group performance, perceived effectiveness, leadership emergence and leadership self-efficacy.

Design

We used a managerial simulation game (see below) to collect data about 96 managers (CEOs) of fictitious companies. In a survey to 1,746 subordinates (on average 18 subordinates per manager) they evaluated skills of their managers following three months of intensive cooperation. We compared the survey results with data on performance of 96 fictitious companies run by those evaluated managers. Data were collected as part of university courses. All respondents were undergraduates at two Czech universities specializing in Business and Economics.

Subordinates anonymously filled in an electronically administrated questionnaire containing 66 items describing behavior of a manager during the game and 5 items relating to the respondent's role in the game. The questionnaires were administered prior to announcing the game's outcome. For completing the questionnaire, all respondents were rewarded with fictitious money, which could have increased the student's chances of successful evaluation in respective university courses.

Managerial Simulation Game

The managerial simulation game used was created at Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic, as a part of a Management course used for the development of managerial skills (Smutny et al., 2013). A group of approximately 20 students manages a fictitious car manufacturer, aiming to maximize the company's accumulated profit during seven gaming rounds. Students learn the rules of the game in introductory seminars and, in a selection procedure, choose the CEO (manager, the subject of the research). Then, the group chooses the manager from 3-5 candidates – volunteers who take part in the selection procedure, which takes a week to prepare. The manager appoints top management, makes decisions dividing the company into departments, and assigns other management members to them. During the game managers can, respecting the game's rules, release any member of their team and at the same time headhunt employees from another company and recruit them. For their work, players receive remuneration in form of fictitious money and the sum they receive determines their final mark at the semester's end. The manager has the final say when classifying employee pay scales and assigning financial evaluations and bonuses to individuals. A successful company on the market can generate larger funds and its employees have a better chance of getting a better mark. The manager's executive powers are extensive, though he/she can also delegate them.

Several fictitious carmakers are always operating on a single separate market. Each market has its own fictitious clients who are uninfluenced by the situation in other markets. At the beginning of the game the position of all car-making companies is identical. The market computer simulation model takes individual decisions of the carmaker's management into account and then determines the overall demand for cars and the market share of individual carmakers accordingly. During the game, students have a number of options for enhancing their company's performance. They decide how many cars to produce in each round, set production costs, invest in research, add accessories to the standard equipment of a car, run advertising campaigns, and negotiate credit with banks. In every round, each carmaker must complete financial statements, analyze the results of other companies, and pay out salaries. The entire workload is insurmountable for one person, or even for a small group. A successful company will involve all, or virtually all of the students in its tasks and functions. However, with respect to the manager's executive power and the need to coordinate a medium-sized company, the manager plays a key role in a company's success.

Fripp (1997) points out the potential of simulation games for research and Dorfman (2007) reports on their application. In comparison with reality, simulation games produce a standardized environment. At the beginning of the managerial simulation game all companies' external and internal conditions for running their businesses are equal. They have the same market share, use the same production technologies, and have production factors at the same price, as well as equal access to information. The number of employees and their qualifications are more or less the same. The influence of potential intervening variables is weak, due to the standardized conditions that make the environment suitable for research into effectiveness in the area of management. This weak level of influence enables quantitative comparison of the objective performances of a large number of companies provided that all the companies under scrutiny have the same goal and equal potential to achieve this goal. The managerial game faithfully simulates the environment of the real economy (Smutny, 2007). This fact will allow the results of the research to be transferrable into a real economic environment. However, the results of the research in the environment of simulation game should be interpreted with the awareness of the specific sample (i.e. students) and artificial conditions (i.e. the simulation). Even though the internal validity of the research is high, the external validity is a topic for discussion.

Sample

All 1,746 subordinates were undergraduates (Mage = 21.16; SDage = 1.39) at the Faculty of Economics and Administration of Masaryk University in Brno (700 respondents) and the University of Economics in Prague (1,046 respondents). Their participation in the managerial simulation game was part of their curriculum. In the managerial simulation game students are the employees of 96 fictitious companies. A total of 1,937 students had the chance to evaluate their manager. The return rate of questionnaires was 91.12%. The results of a pretest show that students need more than four minutes just to read the questions without considering the answers. We rejected 17 out of 1,765 completed questionnaires as the students filled them in less than four minutes. We assume that the 17 eliminated students completed the questionnaire at random with only the aim of getting financial reward for its submission. We rejected two questionnaires as these students indicated that they did not attend the classes so they could not assess their manager accurately.

All managers (Mage = 21.74; SDage = 2.3) evaluated in the game were also undergraduates at the above universities (38 managers in Brno, 58 managers in Prague). In the managerial simulation game they became CEOs of 96 fictitious companies. Most of the managers were men (79%).

Variables

Managerial Skills

Five managerial skills were measured in the current study: organizational skills, motivational skills, communication skills, evaluation and supervisory skills and cooperativeness. Out of the total of 66 items on the questionnaire 24 relate to these skills. The items' wording reflects partial components of the described skills (see Table 1). For each of the items, a respondent can choose whether the item completely characterizes, partially characterizes or does not characterize the manager's behavior during the game (responses are encoded 2; 1; 0). We chose the 3-point scale since respondents were assessing past observed behavior. By using a longer scale the results could be more biased by the feelings of respondents. A cognitive interview with two people provided verification of the comprehensibility of the items and sufficiency of the three provided items. To ensure content validity, the items were derived from the competence model that underpins this study. Correspondence of the items with the model was assessed and verified by two specialists in the area of management and managerial skills.

The number of items varies for different skills as every single skill requires a specific description. All items relating to one skill form one subscale of the questionnaire. Based on a reliability analysis we removed one item that did not contribute to the quality of individual subscales (item from Communication skills subscale).

We averaged the skills' evaluation by many subordinates as an evaluation by less than 6 subordinates has a low reliability (Conway & Huffcutt, 1997). For example, the interaction of subordinate's personality characteristics with manager's personality characteristics may influence the individual perception of managerial skills (Spillane & Spillane, 1998). Each managerial skill tallies with one interval variable equal to the average of the subordinates' evaluation in items describing a particular managerial skill. The value of each variable can range from 0 to 2. Table 2 shows the number of items in individual subscales as well as Cronbach's α and descriptive statistics for all variables. The authors are ready to send the full version of the questionnaire upon request.

Leadership Emergence and Perceived Effectiveness

Five items, split into two subscales, examine the perceived effectiveness of managers and their leadership qualities. The first subscale (Leadership emergence, 3 items) includes items concerning how subordinates perceive their manager as an emergent leader. We formulated the items in the subscale of leadership emergence so that they reflected the transition of a schoolmate into a leader from three different perspectives: i) the way he/she holds his/her role in the game, which is by definition the role of a leader; ii) whether his/her subordinates perceive him/her as a leader in the course of the game; iii) whether his/her subordinates perceive him/her as a person who could be a leader elsewhere and under different circumstances (mainly according to their experience from the game).

The second subscale (Perceived effectiveness, 2 items) includes items evaluating the manager's influence on the fictitious company's effectiveness in the course of the managerial simulation game. The subscale assesses effectiveness from two perspectives: i) whether the scheduled activity of the unit under manager's guidance is effective; ii) whether the result of the activity is effective.

Each of the items in the leadership emergence and perceived effectiveness subscales are formulated to reflect one of the seven mentioned perspectives. A three-member expert group verified that the items tap into the presented aspects of both leadership emergence and perceived effectiveness (content validity). Evidence of construct validity of these subscales is presented below in the results section. Positive relationships with group performance and leadership self-efficacy supports convergent validity of the subscales. For each of the above items the respondent can choose whether the item completely characterizes, partially characterizes or does not characterize their perception of a manager during the managerial simulation game (responses are encoded 2; 1; 0). Cronbach's alpha, expressing the internal consistency of the scale, exceeds the minimum value required = 0.7 for both subscales (Table 2). Each subscale tallies with one interval variable. Its value for each manager corresponds with the average evaluation by all his/her subordinates in items falling into the appropriate subscale. Each variable may range from 0 to 2.

Leadership Self-efficacy

Managers themselves used the same items for their self-evaluation that subordinates used for their managers. The creation of the leadership self-efficacy variable is similar to that of the perceived effectiveness and leadership emergence variable and is based on a manager's self-evaluation. Using the five above mentioned items (used for measuring of perceived effectiveness and leadership emergence), the managers evaluate the effectiveness of the unit under their management, the resulting effectiveness of the unit and their emergence as the leaders. Leadership self-efficacy scale tallies with an interval variable of the same name, calculated as the average value of the manager's responses. The variable can range from 0 to 2.

Group Performance

The company's profitability under the CEO's management throughout the managerial simulation game determines group performance. All fictitious companies have equal conditions at the beginning of the game. Their profitability during the seven rounds is an effective indicator of performance. During the game, the companies operate on different markets, with conditions evolving differently due to the interaction and competition among the companies. Thus, evaluating the company's profitability relatively with respect to the average profitability in that particular market is essential. The interval variable of group performance thus reflects the cumulated profit of a company during the game divided by the average cumulative profit on a particular market. Of the 96 fictitious companies 24 operated on a market formed by six companies and 72 on a market formed by eight companies.

Results

Individual variables describing managerial effectiveness are not independent and exhibit a statistically significant positive correlation. For correlations between variables see Table 2, which also presents descriptive statistics of all variables.

Considering the number of managers and only five potential predictors, we chose the regression analysis as the best statistical method to verify the hypothesis. This study was looking separately for predictors of all four mentioned managerial effectiveness indicators. Tables 3-6 present results of linear regression analyses (OLS estimation) with 5 independent variables (managerial skills) and one dependent variable (one of the effectiveness indicators).

The only significant predictor for group performance is motivational skills (Table 3). It is a moderately strong predictor but the whole model is relatively weak because it explains only 15% of group performance variance.

The perceived effectiveness model is stronger (explains 57% of perceived effectiveness variance) than the model with group performance. It consists of two moderately strong managerial skills predictors –organizational skills and motivational skills (Table 4).

Among managerial effectiveness indicators, leadership emergence has most managerial skills predictors –two moderately strong (communication skills, organizational skills) and one weak (cooperativeness). The model explains 88% of leadership emergence variance (Table 5).

Among managerial effectiveness indicators, leadership emergence has most managerial skills predictors –two moderately strong (communication skills, organizational skills) and one weak (cooperativeness). The model explains 88% of leadership emergence variance (Table 5).

Evaluation and supervisory skills are the only significant predictor for leadership self-efficacy. The model explains 19% of leadership self-efficacy variance (Table 6).

We found only a partial support for our hypothesis that the levels of communication skills, motivational skills, organizational skills, evaluation and supervisory skills and cooperativeness of a manager relate to group performance, perceived effectiveness, leadership emergence and leadership self-efficacy. Each of the five managerial skills predicts at least one of the managerial effectiveness indicators. However, various indicators of managerial effectiveness have various managerial skills predictors.

Conclusions

This study looks into how five managerial skills predict four different indicators of managerial effectiveness. Data analysis does not confirm the hypothesis that all mentioned managerial skills are predictors for all effectiveness indicators. These indicators relate to managerial skills though every indicator is predicted by a different set of managerial skills. It is possible to predict group performance by knowing the level of manager's motivational skills. This means that motivational skills are the only ones (among five skills investigated in this study) that significantly predict profitability of a particular company. By using their motivational skills, managers give a reason to their subordinates to work hard for the company.

Managerial skills are what subordinates could notice when assessing their manager besides the profits, market share or manager personality characteristics. The skills form an image through which the team perceives the manager, and if the image is positive the manager is also perceived positively as an effective manager or as a leader. The skills that predict perceived managerial effectiveness are organizational skills and motivation skills. A manager who is perceived as an effective leader is able to organize work well, take responsibility and energize people. The skills related directly to treatment of people (i.e. cooperation and communication) play more important part in assessing a manager as a good leader (leadership emergence). Unlike perceived effectiveness and group performance, leadership emergence is not predicted by motivational skills. It is predicted by organizational skills, communication skills and cooperativeness. A communicative manager who cooperates with and organizes the group is probably seen as somebody who fulfills the role of good leader. The interesting fact is that communication skills are a strong predictor for the leadership emergence but not for the other indicators. Such a finding is in accordance with the research of Riggio et al. (2003) about the assessment of people with a higher level of communication skills as being better leaders. Using good communication skills to persuade people that a person is a good leader may be possible initially; nevertheless, this persuasion alone does not help to make management really effective according to measurement by less subjective criteria.

The only predictor of leadership self-efficacy is evaluation and supervisory skills. These skills are related to a clear set of expectations and standards and to systematic assessment. Managers in their leading position might see supervision and evaluation as a key component of their work and therefore they evaluate themselves based on how well they manage this part of the work. On the contrary, evaluation and supervisory skills do not have influence on the evaluation by subordinates or group performance.

Motivational skills and organizational skills predict two indicators and are the key predictors in the estimation of future managerial effectiveness. The least important predictor seems to be cooperativeness, which barely influences leadership emergence. For management development, we recommend focusing especially on motivational skills in order to enhance team performance and organizational skills for reinforcing manager's position. Development, evaluation and supervisory skills can further help increase a manager's self-efficacy.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

The presence of a different significant predictor for leadership self-efficacy than for the other indicators can be caused by the influence of erroneous self-evaluation. While the perceived effectiveness and leadership emergence variables are the product of the assessment of roughly 18 people, the leadership self-efficacy variable is the result of the self-evaluation by one person only. While one erroneous evaluation may remain unnoticed among the 18, a similarly erroneous self-evaluation can distort the results significantly (Hogan et al., 1994). The lower value of Cronbach's α in the questionnaire for leadership self-efficacy supports this fact.

In models with leadership emergence and perceived effectiveness, assessment of dependent and independent variables come from the same source. A portion of common variance could be a result of a common-method bias. The common-method bias could cause the strong relationship between managerial skills and managerial effectiveness indicators that are assessed by subordinates. However, the relationship of managerial skills with group performance and leadership self-efficacy cannot be influenced by common-method bias yet it is still significant. Using four different indicator of managerial effectiveness coming from three different sources might be one of the strengths of this study.

In the environment of a managerial simulation game, the structure of teams may play a significant role. In this case, the teams are very similar with respect to age, education, and other characteristics common to the students of Czech universities of economics. Several differences between individuals are still possible, and a strong and able subordinate can compensate for some of his/her manager's weaknesses.

In comparison with research in a real business environment, the managerial simulation game method has lower external validity. The duration of the game company is limited to three months. It is possible that the influence of some managerial skills on the effectiveness indicators is different in the short and long term and could not be observed in a three-month long simulation. The employees in managerial simulation game do not earn real salary and their motives for expending effort may differ in game conditions from the real life. It is also possible that the influence of some managerial skills (e.g. motivation skills) on the effectiveness indicators is different during the game and in the real business. However, the simulation game method brings one big advantage in comparison with studies in real commercial sphere: A large number of independent and very similar business units with the possibility to compare them, thus providing a large amount of unbiased data and not burdening the research with differences between the groups. On the other hand, in comparison with other research involving student respondents, this managerial simulation game offers more complex tasks resembling those of real practice, longer duration of the team as well as larger teams which enables more precise evaluation of a manager.

The results may be influenced by the multicollinearity of the predictors used in our study (Table 2). The reasons for high correlations across managerial skills are most likely three: i) managers do not utilize their managerial skills in isolation, most tasks require using different skills, thus, if a manager lacks any one of them, he/she can fail in fulfilling a particular task and the remaining skills can seem to be less developed than they really are; ii) some managers are more experienced or talented, which enables them to stand out in various skills simultaneously; and iii) all skills were evaluated by the same individuals (subordinates), thus, the evaluation could have been tainted by positive or negative perception of their own manager. Statistical indicators showed that regression analyses were not devaluated by multicollinearity (the highest VIF score is 4.69, the lowest tolerance score is 0.21). However, it should be taken into account in the interpretation of our results.

The scales used for measurement of managerial skills and managerial effectiveness were developed directly for the purposes of the managerial simulation game. Individual items were therefore relevant to how managers could manifest individual skills and what could have been perceived by their subordinates as effective. On the other hand, using originally developed questionnaires is related to the absence of some evidence of their validity and reliability.

In this study, we presented evidence of internal consistency and convergent validity of the questionnaire and explained how content validity was ensured. Current evidence is missing of whether the measured skills are stable characteristics (test-retest reliability) as well as the evidence of convergent and discriminant validity from other variables. Given the sample size, factorial structure of the questionnaire is also lacking. We see the field of effectiveness of individual managerial skills as still underexplored; for this reason, conducting similar research in a different environment or using different methods is needed. Research conducted with different research sample and in a real corporate environment could potentially enhance the external validity of our findings. Furthermore, the level of managerial skills could be measured using special tasks examining those skills. The tasks would lead to isolated evaluations of the skills and would therefore not depict the mutual interaction of the skills or long-term skills usage. Followers' perception of the manager would not have such an impact on the skills assessment and the individual skills would correlate with each other into much lesser extent.

References

Abraham, S. E., Karns, L. A., Shaw, K., & Mena, M. A. (2001). Managerial competencies and the managerial performance appraisal process. Journal of Management Development, 20(10), 842-852.

Agut, S., Grau, R., & Peiro, M. J. (2003). Competency needs among ma-nagers from Spanish hotels and restaurants and their training de-mands. Hospitality Management, 22(3), 281-295. doi: 10.1016/ s0278-4319(03)00045-8.

Analoui, F. (1999). Eight parameters of managerial effectiveness: A study of senior managers in Ghana. Journal of Management Development, 18(4), 362-390. doi: 10.1108/02621719910265568.

Analoui, F., Ahmed, A. A., & Kakabadse, N. (2010). Parameters of ma-nagerial effectiveness: The case of senior managers in the Muscat Municipality, Oman. Journal of Management Development, 29(1), 56-78. doi: 10.1108/02621711011009072.

Analoui, F., Labbaf, H., & Noorbakhsh, F. (2000). Identification of clus-ters of managerial skills for increased effectiveness: The case of the steel industry in Iran. International Journal of Training & Development, 4(3), 217-234.

Anderson, D. W., Krajewski, H. T., Goffin, R. D., & Jackson, D. N. (2008). A leadership self-efficacy taxonomy and its relation to effective leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 19(5), 595-608. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.07.003.

Antonacopoulou, E. P., & Fitzgerald, L. (1996). Reframing competency in management development. Human Resource Management Journal, 6(1), 27-48. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-8583.1996.tb00395.x.

Avolio, B. J., & Waldman, D. A. (1989). Ratings of managerial skill requi-rements: comparison of age- and job-related factors. Psychology and Aging, 4(4), 464-470.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1989). Potential biases in leadership mea-sures: How prototypes, leniency, and general satisfaction relate to ratings and rankings of transformational and transactional lea-dership constructs. Educational & Psychological Measurement, 49, 509-527.

Botha, S., & Claassens, M. (2010). Leadership competencies: The contribution of the bachelor in management and leadership (BML) to the development of leaders at first national bank, South Africa. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 9(10), 77-87.

Bradford, D. L. (1983). Some potential problems with the teaching of managerial competencies. Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal, 8(2), 45-49.

Brownell, J. (2008). Leading on land and sea: Competencies and context. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27(2), 137-150. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2007.11.003.

Bruno, L. F. C., & Lay, E. G. E. (2008). Personal values and leadership effectiveness. Journal of Business Research, 67(6), 678-683. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.06.044.

Cardy, R. L., & Selvarajan, T. T. (2006). Competencies: Alternative fra-meworks for competitive advantage. Business Horizons, 49(3). doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2005.09.004.

Cavazotte, F., Moreno, V., & Hickmann, M. (2012). Effects of leader in-telligence, personality and emotional intelligence on transformational leadership and managerial performance. Leadership Quarterly, 23(3), 443-455. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.10.003.

Chong, E. (2008). Managerial competency appraisal: A cross-cultural study of American and East Asian managers. Journal of Business Research, 67(3), 191-200. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.06.007.

Cizel, B., Anafarta, N., & Sarvan, F. (2007). An analysis of managerial competency needs in the tourism sector: The case of Turkey. Tou-rism Review, 62(2). doi: 10.1108/16605370780000310.

Conway, J. M., & Huffcutt, A. I. (1997). Psychometric properties of mul-tisource performance ratings: A meta-analysis of subordinate, su-pervisor, peer and self-rating. Human Performance, 70(4), 331-360. doi: 10.1207/s15327043hup1004_2.

DeRue, D. S., Nahrgang, J. D., Wellman, N., & Humphrey, S. E. (2011). Trait and behavioral theories of leadership: An integration and meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 7-52. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01201.x.

Dorfman, P. W. (2007). International and cross-cultural leadership. In: Punitt, B. J., & Shenkar, O. (Eds.). Handbook for international ma-nagement research (pp. 267-349). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Drucker, P. F. (2005). The essential Drucker: The best of sixty years of Peter Drucker's essential writings on management. New York: Collins Business.

Dulewicz, V. (1989). Assessment centres as the route to competence. Personnel Management, 27 (11), 56-59.

Eagly, A. H., Karau, S. J., & Makhijani, M. G. (1995). Gender and the effectiveness of leaders: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 777(1), 125-145. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.125.

Elenkov, D. S. (2002). Effects of leadership on organizational performance in Russian companies. Journal of Business Research, 55(6), 467-480. doi: 10.1016/s0148-2963(00)00174-0.

Emiliani, M. L. (2003). Linking leaders' beliefs to their behaviors and competencies. Management Decision, 47(9), 893-910. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740310497430.

Feng-Jing, F., & Avery, G. C. (2008). Missing links in understanding the relationship between leadership and organizational performance. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 7, 67-78.

Foti, R. J., & Hauenstein, N. M. A. (2007). Pattern and variable ap-proaches in leadership emergence and effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 347-355.

Fripp, J. (1997). A future for business simulations? Journal of European Industrial Training, 27 (4), 138-142.

Garland, H., & Beard, J. F. (1979). Relationship between self-monito-ring and leader emergence across two task situations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64(1), 72-76. doi: 10.1037/h0078045.

Goleman, D. (2000). Leadership that gets results. Harvard Business Re-view, 78(2), 78-90.

Hamlin, R. G. (2004). In support of universalistic models of managerial and leadership effectiveness: Implications for HRD research and practice. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 75(2). doi: 10.1002/hrdq.1098.

Harison, E., & Boonstra, A. (2009). Essential competencies for techno-change management. International Journal of Information Mana-gement, 29(4). doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2008.11.003.

Heffner, M. M., & Flood, P. C. (2000). An exploration of the relations-hips between the adoption of managerial competencies, organisational characteristics, human resource sophistication and performance in Irish organisations. Journal of European Industrial Training, 24(2-4), 128-136.

Hogan, R., Curphy, G. J., & Hogan, J. (1994). What we know about lea-dership: Effectiveness and personality. American Psychologist, 49(6), 493-504. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.6.493.

Hogan, R., & Kaiser, R. B. (2005). What we know about leadership. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 169-180. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.169.

Hollenbeck, G. P., McCall, M. W., & Silzer, R. F. (2006). Leadership competency models. Leadership Quarterly, 77(4), 398-413. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.04.003.

Hoyt, C. L., Murphy, S. E., Halverson, S. K., & Watson, C. B. (2003). Group leadership: Efficacy and effectiveness. Group Dynamics-Theory Re-search and Practice, 7(4), 259-274. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.7.4.259.

Joyce, W. F., Nohria, N., & Roberson, B. (2003). What Really Works: The 4+2 Formula for Sustained Business Success. New York: Harper Business.

Levenson, A. R., Van der Stede, W. A., & Cohen, S. G. (2006). Mea-suring the relationship between managerial competencies and performance. Journal of Management, 32(3), 360-380. doi: 10.1177/0149206305280789.

Lord, R. G., Devader, C. L., & Alliger, G. M. (1986). A meta-analysis of the relation between personality traits and leadership perceptions: An application of validity generalization procedures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 402-410. doi: 10.1037//0021-9010.71.3.402.

Man, T. W. Y., Lau, T., & Chan, K. F. (2002). The competitiveness of small and medium enterprises: A conceptualization with focus on en-trepreneurial competencies. Journal of Business Venturing, 77(2), 123-142. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9026(00)00058-6.

Mansfield, R. S. (1996). Building competency models: Approaches for HR professionals. Human Resource Management, 35(1), 7-18. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-050x(199621)35:1<7::aid-hrm1>3.0.co;2-2.

Mintzberg, H. (1975). Managers job-folklore and fact. Harvard Business Review, 53(4), 49-61.

Mumford, M. D., Zaccaro, S. J., Harding, F. D., Jacobs, T. O., & Fleis-hman, E. A. (2000). Leadership skills for a changing world: Solving complex social problems. Leadership Quarterly, 77(1), 11-35. doi: 10.1016/s1048-9843(99)00041-7.

Murphy, S. E. (1992). The Contribution of Leadership Experience and Self-efficacy to Group Performance Under Evaluation Apprehen-sion. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Washington, Seattle.

Ng, K. Y., Ang, S., & Chan, K. Y. (2008). Personality and leader effectiveness: A moderated mediation model of leadership self-efficacy, job demands, and job autonomy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(4), 733-743. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.4.733.

Nwokah, G. N., & Ahiauzu, A. I. (2008). Managerial competen-cies and marketing effectiveness in corporate organizations in Nigeria. Journal of Management Development, 27(8). doi: 10.1108/02621710810895677.

Patanakul, P., & Milosevic, D. (2008). A competency model for effecti-veness in managing multiple projects. The Journal of High Tech-nology Management Research, 78(2), 118-131.

Pickett, L. (1998). Competencies and managerial effectiveness: Put-ting competencies to work. Public Personnel Management, 27(1), 103-115.

Rice, R. W., & Chemers, M. M. (1973). Predicting the emergence of lea-ders using Fiedler's contingency model of leadership effective-ness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 57(3), 281-287. doi: 10.1037/ h0034722.

Riggio, R. E., & Lee, J. (2007). Emotional and interpersonal competencies and leader development. Human Resource Management Review, 77(4). doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2007.08.008.

Riggio, R. E., Riggio, H. R., Salinas, C., & Cole, E. J. (2003). The role of social and emotional communication skills in leader emergence and effectiveness. Group Dynamics-Theory Research and Practice, 7(2), 83-103. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.7.2.83.

Russ-Eft, D. (1995). Defining competencies: A critique. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 6(4), 329-335.

Smutny, P. (2007). Simulation games as means of development of human capital of companies (Doctoral dissertation). Masaryk University, Brno. Retrieved from: http://is.muni.cz/th/20527/esf_d/.

Smutny, P., Prochazka, J., & Vaculik, M. (2013). Learning effectiveness of management simulation game manahra. In: de Carvalho, C. V., & Escudeiro, P. (Eds.). The Proceedings of The 7th European Conference on Games Based Learning (pp. 512-520). Porto: Academic conference and publishing international limited.

Smutny, P., Prochazka, J., & Vaculik, M. (2014). Developing managerial competency model. In The Proceedings of The Hradec Economic Days. Hradec Kralove: Faculty of informatics and management.

Spillane, L., & Spillane, R. (1998). Locus of control and the assessment of managerial skills. Journal of Management & Organization, 4(2), 37-41. doi: 10.5172/jmo.1998.4.2.37.

Tett, R. P., Guterman, H. A., Bleier, A., & Murphy, P. J. (2000). Develop-ment and content validation of a "hyperdimensional" taxonomy of managerial competence. Human Performance, 73(3), 205-251. doi: 10.1207/s15327043hup1303_1.

Tsui, A. S., & Ohlott, P. (1988). Multiple assessment of managerial effectiveness: Interrater agreement and consensus in effectiveness models. Personnel Psychology 47(4), 779-803. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1988.tb00654.x.

Vaculik, M. (2010). Assessment Centrum: Psychologie ve vyberu a rozvoji lidi [Assessment center: The psychology of selection and personal development]. Brno: NC Publishing.

Waters, J. A. (1980). Managerial skill development. Educational & Psychological Measurement, 5, 449-453.

Yukl, G. A. (2008). Leadership in Organizations. Upper saddle river, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Zhong-Ming, W. (2003). Managerial competency modelling and the development of organizational psychology: A Chinese approach. International Journal of Psychology, 38(5), 323-334.