Opportunity to Teach and Learn Standards: Colombian Teachers’

Perspectives1

Estándares

de oportunidad para la enseñanza y el aprendizaje: perspectivas de

profesores colombianos

Rosalba

Cárdenas Ramos*

Fanny

Hernández Gaviria**

Universidad del

Valle, Colombia

**fanny.hernandez@correounivalle.edu.co

This article was received on January 13, 2012, and

accepted on June 12, 2012.

The aim of this article is to present the outcomes of

an exploration of in-service teachers’ perspectives in relation to an

opportunity to teach and learn standards in English. A workshop for English

teachers from Cali (Colombia) and the neighboring rural sectors was designed

and carried out in order to collect the information. Teachers’

perspectives about the topic were explored in terms of three aspects: general

considerations that underlie opportunities to learn; standards and conditions

in educational institutions (work aspects) and other institutional factors such

as human and material resources.

Key words: Equity,

opportunities to learn and teach, standards.

Este

artículo tiene por objetivo presentar los resultados de una

exploración acerca de las reflexiones de un grupo de docentes en

ejercicio, respecto a estándares de oportunidad para la enseñanza y aprendizaje

del inglés como lengua extranjera. Con este propósito se

diseñó y ofreció un taller a profesores de Cali (Colombia)

y de la zona rural aledaña. Allí se estudiaron las perspectivas

de los docentes en cuanto a tres aspectos: consideraciones generales que

subyacen la oportunidad de

aprender, estándares y condiciones en las instituciones educativas y

otros factores tales como recursos materiales y humanos.

Palabras clave: aprender,

enseñar, equidad, estándares de oportunidad.

Introduction

Historical trends towards social and economic

integration have consolidated the English language as a lingua franca in

international communications. English has evolved as a required tool for

communicative purposes in different economic, commercial, political, cultural

and academic contexts. In Colombia, the effects of this historical trend have

also materialized in our educational policies; the international use of English

has generated requirements in terms of standards, which should help to

determine levels of language proficiency. In the formulation of the standards,

the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of

Europe, 2001) was adopted as the principal source and the basic standards for

foreign languages—English—were designed and published in Colombia.

The Basic Standards for Foreign Languages, English (Ministerio de Educación Nacional—MEN, 2006), was issued as the most visible

part of the National Bilingual Program (NBP) 2004-2019. This program states

that, by 2019, all students and teachers at the different educational levels

should reach a predetermined level of English, according to the CEFR scale,

which should be as follows: C1 for professionals of foreign languages; B2 for

professionals of any area; B2 for English teachers at the elementary level, B1

for students who finish the secondary level, and A2 for teachers of other areas

at the elementary level. However, reaching these goals within the expected time

is not an easy task. The achievement of these goals could be hindered by

different aspects, such as the status of English as a foreign language in our

country, the current level of English proficiency among students and English

teachers, and the lack of appropriate conditions for improving the foreign

language learning process in public and private educational institutions of low

socioeconomic strata.

Having in mind the language proficiency goals to be

reached and the presumed difficulties to attain them, we thought of the

importance of investigating the real opportunities students and teachers are

being offered by their institutions in order to reach these standards. Based on

Navarro’s study (2004) on schools and their learning and teaching

conditions, in which he argues that there are some baseline factors

(‘Primary goods’) that people require to be free and equal citizens

in a society, and on everyday knowledge, it is not difficult to understand that

many countries fail to offer the basic opportunities to learn a foreign language

and that many factors need to be developed in order to build firm bases for

Opportunity to Learn (OTL) Standards. One might reasonably suppose that a study

which shows crucial aspects of work in schools as well as teachers’

experiences could help to provide information leading to the identification of

elements in order to create opportunities to learn in a specific context. At

the same time, such a study would make interventions designed to improve the

learning process of the foreign language possible.

The University of California, Los Angeles’

(UCLA) Institute for Democracy, Education and Access (2003, p. 1) defines

Opportunity to Learn (OTL) as “a way of measuring and reporting whether

students and teachers have access to the different ingredients that make up

quality schools.” The OTL standards movement has balanced the last

educational reforms in the USA, which dealt mainly with performance and content

standards without providing the conditions to reach them; the movement has

lately expanded to other countries. The implementation of the NBP in Colombia

has raised questions and concern regarding the conditions of education, equity,

opportunity and social imbalance. Cárdenas and Hernández (2011,

p. 252) argue that there is a need to construct the framework for the

improvement of English Language Teaching (ELT) in Colombia: “…it is

urgent to demand the betterment of conditions for the achievement of goals in

the NBP, that is, the assurance of Opportunity to Learn (and teach) Standards,

from Colombian educational authorities.”

The previous thoughts and what we have witnessed in a

two-year research project about the conditions of implementing the NBP, which

involved 58 schools from strata 1 to 4 from the public and private sectors,

gave rise to the idea of designing and offering a workshop for English teachers

from Cali and the neighboring rural sectors, with the intention of exploring

in-service teachers’ thoughts in relation to the opportunities for

teaching and learning. The workshop session started by building a basic

theoretical foundation for the OTL concept in order to ensure a common

conceptual ground and, after that, focused on the exploration of

teachers’ perspectives about OTL. Outcomes of the workshop carried out

with teachers provided the following information:

·

General aspects

that underlie opportunities to learn: worth and personal competence, healthy

choices, decision-making, the teacher as an agent that transforms society.

• Standards

and conditions in the institutions teachers represented: work-related aspects

(teachers’ attitudes, interests and reasons for them; difficulties of

different kinds; foreign language teaching methodologies; content clarity;

evaluation, etc.) and institutional factors (infrastructure; human and material

resources, support, etc.)

• Human

development. Personal aspects: dependability, productivity, career choices,

attitude, resistance to change and responsibility.

This paper discusses the results obtained after exploring

the views about OTL standards among the group of teachers who participated in

the workshop. The teachers’ perspectives in relation to OTL standards

gathered in the workshop are valuable contributions in the process of building

opportunities to teach and learn standards in English in Cali and, hopefully,

in the wider national context.

Building up

OTL Standards

The initial workshop was attended by 62 English

teachers, mainly from the public sector, from Cali and Jamundí.

They represented approximately 17 schools. The workshop lasted four (4) hours

and was held on a Saturday.

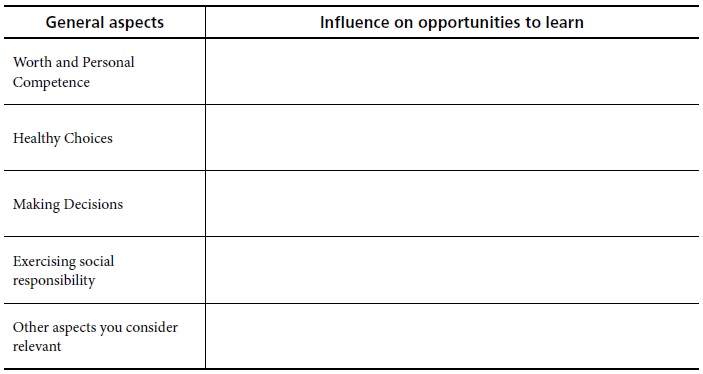

The content of the workshop was organized in four

sections that dealt with: 1. definitions (standards, opportunity, development,

Opportunity to Learn standards); 2. general aspects

that underlie Opportunity to Learn standards and conditions in the institution

teachers work for (worth and personal competence; healthy choices; decision-

making; exercising social responsibility, plus other aspects the participants

consider relevant); 3. human development issues

(Dependability, productivity, career choices, attitude, resistance to change,

responsibility and other aspects); and 4. the impact

of the implementation of standards on teachers, students, school

administrators, parents and the school community.

In dealing with parts two to four of the workshop, we

used a questionnaire organized in sections which teachers could answer

individually or in groups; theoretical support was provided when needed (see Appendix). The questionnaire was made up of four group

discussions and two plenary discussions. Both group discussions and plenary

discussions had guiding questions. Other explanatory elements were also

included in the questionnaires.

Group discussion one enquired about teachers’

opinions on the role of aspects such as worth, personal competence, healthy

choices, decision-making and social responsibility regarding their

students’ and their own opportunities to develop as individuals and

members of society.

This was followed by the first plenary discussion,

which explored the opportunities that might contribute to the professional

development of teachers.

The second plenary discussion aimed at identifying the

role and responsibility of

educational authorities as providers of opportunities for teachers and learners

within the NBP. Notes and recordings of teachers’ answers were made.

Group discussion two focused on standards and

institutional conditions.

Group discussion three addressed human development

issues and personal aspects. Participants were asked to evaluate their

dependability, attitude, responsibility, productivity, and resistance to

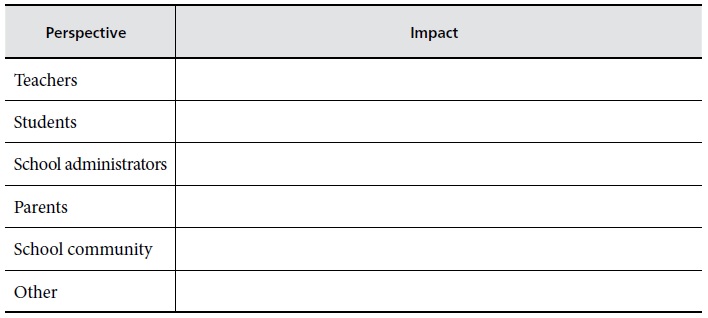

change, among others aspects. Finally, group discussion four asked teachers to

reflect upon the impact that establishing these standards could have on their

institutions.

The Vermont Department of Education (2000) section on

Personal Development Standards provided some of the topics used in this

questionnaire. To this source, we added questions concerning the

teachers’ institutional context and the foreseeable impact of the

implementation of standards in their schools. The information was then analyzed

qualitatively; it was read and re-read, transcribed, organized, color-coded and

categorized; charts were created to visualize it better. Finally, it was

analyzed and relevant examples were selected. The first three major categories

had been pre-established according to the sections in the questionnaire, as

well as some of the sub-categories of the second column. Major category four and

its associated subcategories, in addition to the entire third column of

subcategories, emerged from the data. Because of space limitations in the

discussion, subcategories are not fully expanded and exemplified.

Discussion

of the Findings from the Workshop

Teachers’ contributions in the workshop gave

rise to a great number of subcategories (see Table 1)

which were organized following the structure of the main categories.

Nevertheless, not all subcategories are developed in the analysis; instead, it

focuses on those of higher occurrence in the two plenaries and four group

discussions: general aspects underlying Opportunity to Learn

standards; OTL standards and their relationship with conditions in schools;

human development and impact on students and parents.

In terms of general aspects underlying Opportunity to Learn standards and conditions in the schools teachers work

for, we found that all remarks teachers made are oriented towards themselves

and most of the time giving a very positive view of themselves and of the work

they do. Teachers feel they do well because they need to set an example; as one

of the teachers states: “It’s important that the teacher be a model

for the student, showing values with his attitude and reflecting

professionalism” (T4)2. It is, however,

necessary to state that teachers who participated in this workshop are highly

motivated and many of them have attended Teacher Development Program (TDP)

courses for some years. It is possible that this fact explains their positive

self-image. They see themselves as individuals with high self-esteem and

self-confidence, positive attitudes towards progress and change. They think

they are ready to interact with other school members to pursue their

development with determination and are eager to use self-evaluation. They

realize the importance of interacting with their peers in order to construct

common bases for working together;

they consider interactions with more experienced colleagues as

strategies to face change: “Some colleagues that work in primary are

studying English by themselves and we help them teaching English in their

groups” (T10).

Regarding the idea of teachers as role-models

(subcategory ‘healthy choices’), teachers feel they need to provide

students and their families with all the available information and options for

a healthy life through curricular activities. The idea that schools and

educational communities must take a comprehensive approach to student health

and social service needs is supported by many researchers in the context, as

shown in Schwartz (1995). Unfortunately, at times those goals are very

demanding for schools and, of course, for teachers. Teachers can also lack an

appropriate level of awareness concerning the importance of a healthy lifestyle

because they experience the same limitations their students have; after all,

they are often immersed in the same culture and are a product of it.

Among the factors that teachers reported and

emphasized as hindering learning are the cultural, social and economic

limitations encountered in the social environment they and their students are

immersed in. Navarro’s analysis of the Chilean situation calls attention

on this issue (2004):

At school, the

complexity of the children’s life demands competences teachers do not

have: drug addict parents, unstable parents with variable composition, poverty

and delinquency are new variables which demand new conditions for teaching. To

face this situation, teachers need to assume roles considered to be

parents’ roles: dialogue with children about their everyday experiences,

puberty changes, health and eating habits. The school starts to be more like

home. (p. 128)

The social and economic limitations teachers mentioned

in this section about ‘healthy choices’ are definitely connected to

the absence of equal conditions and social differences. Rawls (1999, in Navarro

2004), also, stresses the role of these aspects in the presence or absence of

equity and quality in education. For him, income and riches as well as the

social bases for self-respect and dignity are part of the ‘bienes primarios’

all individuals are entitled to. For Raczynsky

(2002), also cited in Navarro, the improvement of ‘material

conditions’ are important elements for the quality of the life we live;

however, he argues that poverty is the product of intangible elements such as

attitudes, values and behaviors, all of which are cultural elements. Working only

on material conditions without taking into account cultural and environmental

factors will not yield lasting improvement in people’s conditions and

their handling of opportunities.

Paes de Barros,

Ferreira, Molinas and Vega (2008) in their study on

the inequality of opportunities in Latin America and the Caribbean, stress that

the circumstances people face early in life, including race, gender, place of

residence and, especially their parents’ income, account for the inequality of

opportunities they face in adulthood. Concerning education, Darling-Hammond

(2007) extensively discusses the role of socio-cultural and economic

limitations of minorities in the type of education they get and the results

they obtain. This feeds a ‘catch twenty-two’ situation, a vicious

circle that feeds poverty, lack of accomplishment, neglect and rejection. In

order to determine limitations of any kind Darling-Hammond finds it necessary

to evaluate whether or not schools have adequate resources, deploy them

effectively, or if they provide equal educational access for all students.

It is clear that inclusion and equality are important

aspects which should be taken into account in the formulation of language

policies such as the National Bilingual Program. In reality what usually

happens is that policies and government programs usually make claims of equity,

democracy and inclusion, but often ignore or overlook realities, probably in

their desire to show results. González (2009, p. 186), discussing Shohamy’s views on language policies (2006, p. 143),

claims that “language policies often ignore their connection to actual

language learning because they do not have a basis in reality, and thus, remain

as good intentions on paper.” This seems to be the case with the NBP.

Along the same lines, Fernández

(2003) asserts that inclusive education is a human right and that the

conception of inclusive education, as an effective means for improving

efficiency in educational processes, involves the need to revise the concept of

educational needs. Here is a summary of what this author considers are the

advantages of inclusive education: It offers equal opportunities for all;

personalizes education; fosters participation, solidarity, and cooperation

within students; improves quality in teaching and promotes efficiency in the

whole educational system; values individualities; maximizes resources for the

benefit of general educational, individual and special needs.

On the issue of inclusion, Machin

(2006) carried out a study which explored how social disadvantage affects the

learning experiences of learners with fewer economic resources. Much of the

work draws upon longitudinal data sources that follow children as they grow up.

It also includes information on their parents and the area where they were raised.

The results of the study show that:

Education and

social disadvantage are closely connected and that people from less advantaged

family backgrounds acquire significantly less education than their more

advantaged counterparts. This translates into significantly reduced life

chances…This includes poorer labor market outcomes, significantly worse

health, higher crime levels and lower levels of social capital. (p. 27)

Concerning the relationship between opportunity to learn

standards and the conditions in the institutions they work at, teachers are, in

general, less positive; they focused their contributions on the aspects that would need to be

changed in order to foster OTL, such as the full integration of the elementary

level in ELT; the introduction of changes in ELT in order to make it an area

with interdisciplinary links and not a one- or two-hour a week course, and the

need for an institutional policy designed to improve the proficiency level of

teachers. They consider it important to have a positive attitude and be ready

to change practices. On the negative side, or factors that affect OTL, teachers

mention the reluctance of some of them to change. Teachers insist on

methodologically ‘safe’ practices and do not use the English

language in class because they are probably afraid of revealing deficiencies in

their competence. This is not a new situation: Cárdenas (2001, p. 2)

surveyed primary English teachers six years after this language was introduced

at the elementary level and found a very similar situation to the one found

today.

Lack of time is also a common hindrance: Teachers do

not have time for meetings, for planning, revising, delivering contents, or

participating in institutional activities and they consider team-work and

planning to be important elements in their professional growth. Teamwork is an

element also considered important by researchers (Tochon,

2009) when researching teacher education. Participatory Action Science (PAS)

used by Tochon as methodological orientation is

characterized by being respectful of the positioning of different partners;

promoting dialogue and the capacity to learn from others’ experiences

while influencing the ability of teachers to shape social outcomes with the aim

of building a more just society. In any case, teachers in the workshop

expressed their disappointment for not being able to rely on sustained spaces

for pedagogical discussion, and for not having been listened to about the

importance of assigning a better status to the English area. Besides, teachers

consider that in order to reach standards in ELT, it is essential to offer this

area as a fundamental one; they said that it is necessary to make an impact on

general teaching and learning conditions and, as a result, improve

students’ achievements. In this respect Denbo,

Grant, and Jackson, (1994) argue that:

It is time for

schools, local education agencies, and state and federal governments to ensure

that no system of testing or student assessment be used except in the context

of educational approaches that are based on standards for equity in educational

resources and processes. (p. 47)

Although this reflection stems from a different

context, it is similar in nature to our national context: Learners from all

regional, geographical, cultural, economic and social contexts are being

evaluated on the same bases although they are learning under different

circumstances and unequal possibilities.

Furthermore, in relation to time for the area,

teachers manifested that the number of weekly instructional hours is 1 at the

elementary level and two (exceptionally 3) in high school. With so little time,

little access to resources, crowded classrooms and high standards to achieve,

the situation is difficult to handle. Teachers express that even with good

resources and all the Development Programs they have access to, it is extremely

difficult to meet the standards because of poor conditions. Based on research

findings it can be said that time is one of the most influential factors in school

and student success. In Chile, for example, as part of the implementation of El inglés abre puertas (English Opens

Doors), the curriculum was modified to strengthen all areas, especially those

that develop “habilidades de orden superior.”

To establish such a curriculum, the school day was expanded, and ELT weekly

instructional time went from 11% to 27% of the time. Most schools

went into jornadas completas

(full-time) (UNESCO report, 2004).

Indeed, Gillies and Jester-Quijada in the USAID document (2008) consider time the most

influential factor in school and student success. They mention the experiences

of Ghana and Peru and their efforts to improve their educational systems; the

two experiences are relatively successful stories in terms of access to the

English language, but both have shown poor outcomes in terms of learning. The

phenomenon is explained in the document arguing that the basic elements for

creating opportunities to learn are overlooked, and that time is one of the

elements which marks the difference between accessing a language and learning a

language.

These authors also stress that a longer school day,

more hours of instructional time a year (they propose a minimum of 850 to 1,000

a year), a more effective use of time at schools, which means fewer

interruptions, less absenteeism, less tardiness, and more time-on-task are the

key elements in OTL. If we analyze the situation in our schools we find that

there are striking differences in the way time is assigned and used in

different types of institutions. Besides, public institutions are affected by

the need to maximize the use of facilities, which makes the school hours very

short. There are also more interruptions to deal with due to social and

economic factors; there is usually more absenteeism and tardiness. The document

also mentions a study carried out in six developing countries (Bangladesh,

Ecuador, India, Indonesia, Peru, and Uganda) which shows teachers’

absenteeism is at an average of 19%. In Colombia there are very few studies about

absenteeism and they do not focus on teacher absenteeism; however, in our

experience as researchers who visited urban schools in Santiago de Cali, we

recognized this as an issue of common occurrence. As a result of absenteeism

and of low assignment to ELT, sometimes weeks elapse without the students

having a single lesson.

Gillies and Jester-Quijada (2008, p. 17) make

distinctions among several uses or misuses of time and analyze how they affect

students’ OTL: time-on-task, teacher and student punctuality and

absenteeism, official instructional time and number of hours per subject. They

complain about how little is known about time-related issues in schools and

express that “No one is held accountable for a failure to provide the

basic opportunity to learn” as far as time is concerned. Another aspect

teachers in the workshop mentioned was the proportion of students per teacher.

In both public and low and medium strata private schools, teachers usually

manage groups of 38 to 50 students, and this fact reduces considerably the time

they can devote to each student. It has been proven that reduced class size

improves students’ achievement (Heros, 2003, in

Gillies & Jester-Quijada,

2008). He suggests that the appropriate class size for students to benefit is

from 15 to 20, and indicates that class size, as well as other elements, is a

cause for students’ absenteeism:

Student attendance

must start with using attendance as a management tool, and in understanding the

underlying causes of absenteeism. To some degree, there is a circular influence

with other OTL factors—if the teacher does not regularly show up, little

learning is taking place; and if the class size is unmanageable, students may

not be motivated to attend (Heros, 2003, p. 10, in Gillies & Jester-Quijada,

2008).

Darling-Hammond (2007) mentions high student-teacher

ratio as a common feature of underprivileged schools. Also, the USAID document

extensively discusses the incidence of student-teacher ratios in the

performance and satisfaction of teachers and students. “Having fewer

children in class reduces the distractions in the room and gives the teacher

more time to devote to each child.” (Mosteller, 1995, in Gillies &

Jester-Quijada, 2008, p. 11). In our context,

with very few exceptions, classrooms in public schools are over-crowded, which

reduces time for interaction in the language class.

Another element teachers who attended the workshop

mentioned as an impediment for good student OTL is the lack of resources, both

human (not enough teachers, crowded classrooms) and material. Small classrooms

without the minimal conditions of light, ventilation, facilities for using

equipment and which have poor acoustics do not facilitate the task. Finally,

some teachers mentioned the fact that there is little or no monitoring from

school administrators of the results of PD; they are not asked to share,

replicate, or even put new knowledge or ideas into use. In other words, they

are not made accountable for improving teachers’ teaching or

students’ results based on the opportunities they,

as administrators, are given. This element is part of what Aguirre-Muñoz

(2008) calls leadership and supervision, not always present in our schools

because of many reasons that arise from the lack of time of principals who have

to divide their time and attention among four or five institutions, to the lack

of interest in some areas.

In the category ‘Human Development’,

teachers declared that trust from their supervisors in their work because of

their preparation and responsibility is one of the factors that favor the OTL

of their students: “I think that in my school my coordinators, principals

and administrative [personnel] have confidence in me because I try to make an

effort to be better day by day.” (T1). Other elements that show the positive

side of teachers and undoubtedly contribute to their students’ OTL are

that they are proactive and seek and take all opportunities for PD, using every

chance to put into practice what they learn. They take pride in what they do:

“My institution has confidence in what I learn to be shared with my

students and colleagues” (T5).

In revising the theory we find that almost all models

mention teacher capability (preparation and expertise) as a key aspect of

OTL; however, other important

elements concerning teachers such as a positive attitude, a strong sense of

self and a sense of job satisfaction in spite of limitations and problems are

omitted; these factors are mentioned only in Schwartz’ model (1995), but

they are considered basic by this group of teachers; the great majority of

teachers feel satisfied with their career: “This role is the most

important for us because we are helping our students and ourselves grow as

human beings in order to contribute [to] and build a better future.” (T3)

Within the same category, the elements that according

to teachers have a negative impact on OTL are usually related to two areas; one

concerns teachers and includes the difficulty for them to find a balance

between their professional and personal lives, the lack of time to do their job

well, the low salaries they receive and the lack of sustained efforts on the

part of educational authorities to offer continuous PDP, although they

recognize that the offer of PD courses has greatly improved in the last three

years. The other factor that affects students’ OTL depends mostly on

students, and is manifested in their lack of interest and involvement in class

and in other academic activities.

The time factor has been under discussion and study in

countries where there is worry about poor results in education. Of the first

three elements mentioned by teachers, one considered as a crucial ingredient in

all models is time. Limited time on the part of teachers affects planning,

preparation, exploration, innovation, assessment, and ability to get to know

students and to lead them into learning. Time limitations have several sources:

little time allocation in timetables and curricula, little time-on-task,

holidays, planned and unplanned meetings, special events and celebrations at schools,

strikes, ‘attitudinal slow-downs’, etc.

In several states of the USA there have been studies

that try to determine the effect of Expanded Learning Time (ELT) on student

achievement. Teachers and researchers find 180 school days a year is about the

same amount of time devoted to school in Colombia and they state that it is too

short to guarantee good results. For example, Marcotte

and Hansen (2010) studied the incidence of shortened school time (due to

closings for bad weather) in students’ results in national exams in the

areas of mathematics and reading; they found that students received lower

scores when the number of weeks of the academic year was shorter. Other studies

reviewed by Marcotte and Hansen (2010)—Lee and Barro (2007), Eren and Millimet

(2007), Marcotte (2007), Hansen (2008), and Sims

(2008)—show evidence in the same direction after implementing ELT

programs and studying their results. As Marcotte and

Hansen (2010, p. 1) conclude, “This new body of evidence… suggests

that extending time in school would in fact likely raise student

achievement”, and that “differences in instructional time can and

do affect school performance”. ELT is not only about more school days a

year, but also about longer hours (between 7 and 8 a day), and meaningful and

optimal use of time in school. Silva (2007) recommends that schools analyze the

way time is spent so they can decide the kind of time they need to extend; she

classifies school time into four categories: allocated school time, allocated

class time, instructional time and academic learning time. In Colombia the

school day in private schools usually goes from 7:00 a.m. (sometimes earlier)

to 3:00 p.m. Public schools usually work from 7:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. or from

1:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. because buildings are used by more than one school or

body of students. At present, the government has acknowledged the importance of

time in the improvement of education and the creation of more inclusive

conditions for all; steps have been taken in the country’s capital to

extend the school hours for children who attend public institutions. Some other

major cities are considering implementation of the same action.

Lastly, but not less important, the teachers mentioned

the issue of low salaries: “I feel free to do my job, and I like it. I

studied for being an English teacher, and I’m doing my best. The only

thing I have to complain is the so poor salary.” (T12). Indeed,

teachers’ income do not usually correspond to the time spent studying to

become a professional; the teachers’

salaries are probably among the lowest paid in any profession, and the

contractual conditions that many teachers have assure them a salary only for a

few continuous months, making their

situation even more difficult. In many cases, this factor affects motivation

and the likelihood of putting enough time or extra time into their work.

Darling-Hammond (2007) finds a direct relation between low salaries for

teachers and schools in deprived or difficult areas, where students do not have

many opportunities for success. This may be the case of many of the teachers

involved in this study; most of them work in schools of the public sector, and

some in deprived urban or rural areas.

In closing the discussions in the workshop, teachers

socialized what they thought was the most remarkable impact of the

implementation of standards in their institutions (main category four). They

highlighted the effects of changing the nature of English teaching. According

to their perception, presenting English as an area and not as a course amounts

to assigning it a higher status and, therefore, requires other changes.

According to them, developing English teaching and learning as an area requires

the revision and adaptation of the teaching methodology, as well as the

planning and curricular execution; it also demands the reevaluation of

teachers’ roles and pedagogical knowledge, cooperative work and

opportunities to grow professionally. The importance of improving the area of

English teaching with more contact hours, methodological innovations, student

exchanges, materials and bilingual bibliography is also considered crucial.

All the revised models for OTL standards include

curricular conditions as one of the elements to improve or revise; these

improvements or revisions usually include integration with other courses (also

mentioned by the teachers in the workshop), adaptations in order to meet

standards, as well as contextualizing content in order to deal with real life

problems. The curriculum also needs to be flexible to cater to different groups

of students.

The establishment of standards has opened the door for

teachers to get updated as new opportunities for professionalization in the

language and in methodology have emerged. Teachers who have been attending the

courses think they are improving and feel more confident teaching the language.

This feeling of increased capability necessarily involves motivation that

favors the development of the area; this fact is highlighted by Rodrigo Fábrega, leader of the Chilean program “Inglés Abre Puertas” (English

Opens Doors), who expressed in an interview for Palabra Maestra (Fundación

Compartir, 2009, p. 3-4) that “it is not enough

to speak the language; teachers need to feel comfortable using it.” Teachers

confessed that they feel more at ease in their classrooms, while those who have

not gotten involved in these processes or who have just initiated them confess

lacking confidence. That is why most of them stress the importance of permanent

updating in topics related to language proficiency, methodology and

technological advances, which they recognize they have to analyze and adapt

before adopting.

The standards movement has generated motivation not

only among teachers but also among administrators. At the same time, teachers

feel that they are now involved in a new educational dynamic, although some of

them would appreciate principals who show more commitment to the development of

the English area. In general, teachers highlight the importance of having more

support for education not only from their principals, but also from the

government and from other professionals in order to strengthen the teaching and

learning processes. They also state they would benefit from more exchange

programs in order to get a real taste of English speaking cultures.

In relation to the impact of standards on students,

teachers say very little; however, it is clear that their opinions are divided:

On the one side, there is a group of teachers who think students are gaining motivation

for learning English because they understand the importance of speaking a

second language. They believe students are more enthusiastic because learning

is no longer oriented towards developing contents or learning only grammar, but

rather towards developing competences. They also believe that programs are

better organized and, as a result, students are also motivated and demanding.

However, there is another group of teachers who think students are not aware of

the importance of learning a second language and that their attitude hinders

progress in the learning process. This group finds it really difficult to

overcome this barrier. As for parents, they are receiving this piece of news

with great expectations; they consider this knowledge to be a useful and extra

tool for their children to become more competitive in life.

Final

Considerations

In presenting English teachers’ views of the way

they are working, the attitudes they have and the challenges they face in the

process of establishing the NBP, we have found enough evidence to demand the

establishment of OTL standards in order to address the issue of equality of

educational opportunities and as a way to ensure the attainment of the goals

proposed in this national policy.

We are well aware that there are many aspects involved

in the design, formulation and issuance of OTL standards; however, not all of

them belong to the sphere of influence of teachers, teacher educators, students

or their families. There are, nonetheless, two main aspects of OTL standards

that we could concentrate on, and these are, on the one hand, teachers

providing their students with opportunities to learn; and, on the other hand,

educational authorities providing teachers with opportunities to teach and

students with opportunities to learn.

How can teachers provide their students with real

opportunities to learn? By getting to know and understand their present

situation and the situation the policy has created; by initiating and

maintaining actions to continue TDP work, by being aware of their strengths and

deficiencies and autonomously working on them, by creating collaborative groups

in their institutions, by using time responsibly, by showing progress in their

work, by creating pressure groups to pursue the betterment of conditions for

teaching and for facilitating teachers to learn and provide their students with

opportunities to learn. A good number of the teachers participating in the

seminars expressed that they were already undertaking actions of this kind and

exercising responsibility in their work, although they also mentioned a not so

generous or responsible attitude on the part of some of their colleagues or

supervisors.

What do teachers feel needs providing in order to

create opportunities to teach? An analysis of the information shows that

conditions for attaining the goals of the NBP are far from being appropriate or

fair, despite the evident efforts on the part of educational authorities

towards fostering teachers’ improvement through TPD programs. Teachers and

students alike are facing cultural, social and economic challenges which have

multiple local causes and are aggravated by present-day global trends. All over

the world demands are being made for the need to provide educational access

under equal conditions for all; inclusive education is claimed not only as a

human right but also as an effective means of improving efficiency in

educational processes. Unfortunately, Colombia occupies a shameful second place

in Latin America concerning inequality3 and the

implementation of educational policies reflects this situation: Most private

institutions have longer hours, better resources, better conditions and

teachers with the adequate profile to implement the NBP. But, other aspects as

well are highlighted by teachers as elements to be revised in order to achieve

standards: Time allocation and management, that would provide more exposure and

opportunities for skills development among students as well as better chances

for teachers to do a good job and continue to develop professionally;

teacher-student ratio that would allow more teacher-student interaction and

closer attention to individual student needs and difficulties. Finally, other

elements mentioned by teachers and analyzed in the revised models for OTL

standards that would guarantee equity and opportunities for all are as follows:

better resources, both human and material; improved physical conditions of

schools and classrooms (lighting, ventilation, acoustics), and last but not

least, the improvement of teachers’ salaries, which are among the lowest

paid to professionals in the country.

In an attempt to gather teachers’ thoughts in

relation to OTL standards and with the intention of opening up discussions on the

topic, we can conclude that a serious revision of the elements mentioned above

is necessary. Changes that take into account teachers’ voices are also a

must if Colombia is to achieve these standards. Striving to accomplish these

standards does not mean responding uncritically to a policy that we know has

advantages and drawbacks; above all, in order to reach higher levels of

proficiency in English or in any target language means giving our students

better cultural and academic possibilities. It also means giving language

teaching professional recognition and its due importance.

1. This article is

based on a workshop carried out with teachers from Cali and Jamundí

at Universidad del Valle (Colombia). The purpose of

the workshop was to explore in-service teachers’ thoughts in relation to

an opportunity to teach and learn standards, an idea that became a goal after

visiting schools within the research project about the conditions of

implementation of the National Bilingual Program (NBP).

2. Teachers have

been given a number in order to make reference to their opinions and

viewpoints.

3. http://www.dinero.com/actualidad/economia/articulo/colombia-campeon-desigualdad-america-latina/120728;

http://www.agenciadenoticias.unal.edu.co/detalle/article/aunque-bajo-la-pobreza-en-colombia-hay-mucha-desigualdad.html

References

Aguirre-Muñoz, Z. (2008). Cátedra Bloom: Estándares de

oportunidad de aprendizaje: una estrategia para promover equidad escolar.

Ciudad de Guatemala: Universidad de San Carlos. Retrieved from http://www.proyectodialogo.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=291&Itemid=112

Cárdenas, R. (2001). Teaching English in primary: Are we ready

for it? HOW, A

Colombian Journal for English Teachers, 8, 1-9.

Cárdenas, R., & Hernández, F. (2011). Towards the formulation of a

proposal for Opportunity to learn standards in EFL learning and teaching.

ÍKALA, 16(28), 231-258.

Colombia. Ministerio de Educación

Nacional [MEN]. (2006). Estándares

básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras: inglés. Serie

Guías No. 22. Bogotá:

Author.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common

European framework of reference for languages. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2007). The flat earth and education: How America’s

commitment to equity will determine our future. Educational Researcher, 36(6), 318-334.

Denbo, S., Grant,

C., & Jackson, S. (1994). Educate

America: A call for equity in school reform. Opportunity to

learn standards. American youth policy forum; Mid

Atlantic Equity Consortium & National Educational Association. Retrieved from http://www.maec.org/Old/pdf/edam.pdf

Department of Education State of Vermont. (2000). Vermont’s framework of standards & learning opportunities.

Montpelier,

VT: Vermont Department of Education.

Fernández, A. (2003).

Educación inclusiva: Enseñar y aprender entre la diversidad. Revista Digital UMBRAL 2000, 13, 1-10. Retrieved from http://www.inclusioneducativa.org/content/documents/Generalidades.pdf

Fundación Compartir. (2009,

Septiembre). Maestros de inglés: los alquimistas de la educación

en Chile. Palabra Maestra, 9(22),

3-4. Retrieved from http://www.premiocompartiralmaestro.org/PDFPMaestra/PALABRA_MAESTRA22.pdf

Gillies, J., & Jester-Quijada,

J. (2008). Opportunity

to learn. A high impact strategy for improving

educational outcomes in developing countries. United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Working paper. Retrieved from http://www.equip123.net/docs/e2-OTL_WP.pdf

González, A. (2009). On Alternative and

additional certifications in English language teaching. ÍKALA, 14(22), 183-209.

Machin, S. (2006). Social

disadvantage and education experiences. OECD social, employment and migration working papers. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/13/60/36165298.pdf

Marcotte, D., & Hansen, B. (2010). Time for School? When the

snow falls, test scores also drop. Education Next, 10(1). Retrieved from http://educationnext.org/time-for-school/

Navarro, L. (2004). La escuela y las condiciones sociales para aprender y enseñar.

Equidad social y educación en sectores de pobreza urbana. Buenos Aires:

Instituto Internacional de Planeamiento de la Educación UNESCO.

Pabón, C., Wills, E., & Salas, S. (2011). “Colombia es el campeón

de la desigualdad en América Latina” Dinero.com. 2011-06-05. Retrieved

from http://www.dinero.com/actualidad/economia/articulo/colombia-campeon-desigualdad-america-latina/120728

Paes de Barros, R.,

Ferreira, F., Molinas J., & Vega, J. (2008). Midiendo la desigualdad de oportunidades en América Latina y el

Caribe. Washington, D.C.: Banco

Mundial.

Schwartz, W. (1995). Opportunity to learn standards: Their impact on urban students. ERIC/CUE Digest Number 110, 1-9. doi: ED389816. Retrieved from http://iume.tc.columbia.edu/i/a/document/15460_Digest_110.pdf

Silva, E. (2007). On the clock: Rethinking the way

schools use time. Washington D.C.: Education sector reports.

Tochon, F. V.

(2009). The role of language in globalization: Language, culture, gender and

institutional learning. International Journal of Educational Policies, 3(2), 107-124. Retrieved from http://ijep.icpres.org/2009/v3n2/fvtochon.pdf

UCLA’s Institute for Democracy, Education, &

Access. (2003). Opportunity

to Learn (OTL) Does California’s school system measure up? Retrieved

from http://just-schools.gseis.ucla.edu/solution/pdfs/OTL.pdf

UNESCO. (2004). La Educación Chilena en el cambio de siglo: Políticas,

resultados y desafíos. Santiago de Chile: Oficina Internacional de

Educación.

About the Authors

Rosalba Cárdenas Ramos, BA in Philology and languages,

Universidad del Atlántico, Colombia. MA in Linguistics and FL education, University of

Louisville, USA. Research

attachment in testing and evaluation, University of Reading, England. Teacher development, Thames Valley University, England. Professor of FL methodology and applied linguistics, Universidad

del Valle, Colombia. Coordinator of Teacher Development Program at

Universidad del Valle.

Fanny Hernández Gaviria, BA in Modern Languages and MA in Linguistics,

Universidad del Valle, Colombia. Assistant professor. Member of the EILA research

group. Teaches English and Classroom research at Universidad del

Valle. Director of the Licenciatura

Program. Participates in the research project on conditions

of implementation of the PNB in Cali, Colombia, describing English

teachers’ profiles.

Appendix: Workshop on Opportunity to Learn Standards

Universidad

del Valle

Facultad de

Humanidades

Escuela de Ciencias del Lenguaje

Group Discussion 1:

General aspects that underlie opportunities to learn

–

What is, in your

opinion, the role, if any, of these elements in you students’ and your

own opportunities to develop as individuals and members of society?

In groups of four, read the following items and decide

whether or not and to which extent they have an influence on opportunities to

learn. Then, complete the table below.

Plenary Discussion

1

Based on your own experience as an individual and as a

teacher, what kind of opportunities have contributed to your development?

Plenary Discussion

2

In your opinion, what is the responsibility and role

of educational authorities as providers of opportunities for teachers and

learners within the Programa Nacional

de Bilinguismo (National Bilingual

Program—NBP)?

Group Discussion 2

Standards and

conditions in the institution I work for.

In the next chart, list all the factors that would

affect the implementation of standards in your institution. Work, if possible,

in institutional groups.

Discussion 3: Human

development/ Personal aspects

These include emotional factors such as fear,

disappointment; attitudinal aspects (expectations, resistance to change,

willingness to work with standards & personal responsibility)

Group Discussion 4

What impact will the implementation of standards have

in your institution?