EFL Students’ Perceptions about a Web-Based English Reading

Comprehension Course

Percepciones

de estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera acerca de un curso de

comprensión lectora apoyado en la red

Érica

Gómez Flórez*

Jorge

Eduardo Pineda**

Natalia

Marín García***

Universidad de

Antioquia, Colombia

**jorgeeduardopineda@gmail.com

This article was received on January 2, 2012, and

accepted on April 30, 2012.

Web-based distance education is an innovative modality

of instruction in Colombia. It is characterized by the separation of the

teacher and learners, the use of technological tools and the students’

autonomy development. This paper reports the findings of a case study that

explores students’ perceptions about an English reading comprehension

course in a web-based modality. Findings show that students have different

opinions about the course, its content and objectives, its level of difficulty,

the time students invested in the course, adults’ learning, and the role

of the teacher. We perceived that this course represents an academic challenge;

it is conducive to learning, and favors students’ autonomous use of time.

Key words: Perceptions, reading comprehension, web-based distance education.

La educación

virtual es una modalidad de instrucción innovadora en Colombia. Se

caracteriza por la separación del profesor y los estudiantes, el uso de

recursos tecnológicos y el desarrollo de su autonomía. Este

artículo muestra los hallazgos de un estudio de caso que explora las

opiniones de los estudiantes acerca de la educación virtual. Se revelan

las diferentes creencias sobre el curso, su contenido, objetivos y nivel de

dificultad, el tiempo invertido por los estudiantes y el papel del profesor.

Encontramos que este curso puede ser considerado como un desafío

académico en el que se facilita el aprendizaje y el uso autónomo

del tiempo.

Palabras clave: comprensión

de lectura, creencias, educación a distancia apoyada en la web.

Introduction

This research study was carried out at the school of

languages, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín,

Colombia. The study took place in a reading comprehension course in English

offered to graduate students of the school of law. We used a case study

methodology to explore the different perceptions students had about web-based

distance courses. We found six main perceptions concerning the course: its

content and objectives; its level of difficulty, the time invested in the

course, adults’ learning, and the role of the teacher.

Literature

Review

In this section of the paper, we will discuss some key

concepts for our study which aimed at exploring the students’ perceptions

while enrolled in a web-based distance reading comprehension course in English.

We will define 4 main concepts: distance education, e-learning, online learning

and web-based education and we will refer to their characteristics, benefits

and drawbacks. Additionally, we will briefly mention the current situation of

distance education in Colombia. Then, we will provide a description of the

Moodle platform. Finally we will explore what reading in a foreign language

entails.

Distance Learning,

E-Learning and Web-Based Learning

Distance learning, e-learning, online learning, and web-based

learning are terms that are sometimes used interchangeably. They are used as

synonyms because of their multiple commonalities referring to the way the

instruction is carried out. In this kind of instruction, two agents are

involved (a learner and an instructor), it occurs at different times and/or

places, and it uses multiple instructional materials (Moore, Dickson-Deane,

& Galyen, 2011).

UNESCO’s Distance Learning Resources Network

defines distance education as an instructional delivery that does not obligate

or require the student to be physically present at the same location as the

instructor. Audio, video and computer technologies are now used as delivery

modes (as cited in Marcelo, Puente, Ballesteros & Palazon,

2002, p. 21). In addition, King (2002) states that in distance education

synchronous and direct interaction are not required during normal day-to-day

activities and that communication is available through discussion using e-mail

or electronic bulletin boards.

Similarly, Keegan (1996) refers to distance education

as an umbrella term for correspondence education, e-learning, online learning,

web-based and virtual learning (as cited by Moore et al., 2011, p. 130).

Distance learning is one of the most known terms; it refers to the access students

have to learn in distant places. These terms are different due to the evolution

distance learning has undergone. This evolution makes reference to the valuable

role technology has taken on in this kind of instruction (Moore et al., 2011).

Ellis (2004, as cited in Moore et al., 2011, p. 130)

mentions that e-learning not only bases instruction on internet, intranet,

web-sites and CD-ROM, but also on audio, video, and TV. It is evident that

technological tools characterized this modality of instruction, but Tavangarian, Leypold, Nölting, Röser, and

Voigt (2004, cited in Moore et al., 2011, p. 130) mention that e-learning

cannot be characterized as only procedural but that there is also evidence of

the transformation of the individual’s experience due to the process the

individuals follow constructing knowledge.

Similarly, online learning is defined by different

authors as “access to learning experiences via the use of some

technology” (Benson, 2002; Carliner, 2004;

Conrad, 2002, as cited in Moore et al., 2011, p. 130). Moreover, Hiltz and Turoff (2005) and

Conrad (2002) argue that online learning is a more recent or improved version

of distance education.

Web-Based Education

According to Sampson (2003), web-based education is a

mode of delivery which includes learning independently by using self-study

texts and asynchronous communication. Keegan (1996, cited in Sampson, 2003, p.

104) states that distance learning is characterized by the following aspects:

(1) the separation of teacher and learners, (2) the influence of an education

organization, (3) the use of technical media, (4) the provision of two way

communication, (5) and occasional face-to-face meetings. Our distance learning

course has all the characteristics stated above except for the occasional face-to-face

meeting that never took place; therefore, we chose the term web-based education

to refer to this modality of instruction along this paper.

King (2002) and Hannay and Newvine (2006) establish a series of benefits and drawbacks

regarding web-based distance education. They state that the main reason that

people choose these courses is the personal convenience they offer and that

participation in the course can take place anytime/anywhere. Distance courses

fit the students’ busy schedules and the students can access the course

from anywhere. However, King (2002) identifies that one of the biggest problems

of these courses is their low completion and high dropout rate. He argues that

the lack of feedback, feelings of isolation, frustration with technology,

anxiety and confusion contribute to an unsuccessful completion of the course.

Similarly Carr-Chellman, Dyer and Breman

(2000, cited in King, 2002, p. 160) state that slow connections, browser or

software interfaces incompatibility and servers going down can generate

frustration related with technology. They also argue that frustration with

technology will continue to be a factor that will generate problems in the

future, although technology related factors are the main determinants of

success or failure in web-based distance education.

Stepp-Greany (2002) also mentions other benefits of web-based distance education in

a study that aimed at determining students’ perceptions of (a) the role

and importance of the instructor in technology-enhanced language learning, (b)

the accessibility and relevance of the lab and the individual technological

components in student learning, and (c) the effects of technology on foreign

language learning experiences. In this study, she found that the role of the

instructor was perceived as very important by the participants since the

students believed that the instructor provided assistance with language and

fostered interaction with them. She also found that the participants’

cultural knowledge, their listening and reading skills as well as their

independent learning skills were enhanced as a result of the exposition to the

technological tools implemented in the program. However, she states that the

participants’ perceptions of the individual technological components were

divided. The participants in her study were first and second semester students

of Spanish enrolled in a technology enhanced learning program which included

internet activities, CD-ROM, electronic pen pals, and threaded discussions.

Distance Education

in Colombia

Facundo (2002) states that e-learning is most popular at the post graduate

level in Colombia. However, until 2002 there were no online programs offered at

the master’s and doctorate level. He also argues that typically, it is

professionals who are unwilling to submit themselves to the limitations of a

traditional classroom who turn to e-learning alternatives because they offer

more flexibility and take less time. Some of the obstacles faced by e-learning

proponents in Colombia are as follows: limited internet access, underdeveloped

tech culture, a shortage of confidence in e-learning, not enough promotion and

training for teachers in challenging economic or geographic circumstances. In

Colombia the most popular fields where e-learning has been used are education

engineering and the health sciences.

Facundo (2002) elicits some recommendations regarding the implementation of

web-based education. He states that e-learning can be promoted through

institutional agreements, more concern over the spread of pirated material, the

creation of open access courses, broader net coverage so that service is

cheaper and more accessible, marketing campaigns, and promotion of usefulness

of virtual tools in the areas of research and e-learning.

Moodle Platform

Another concept that we want to discuss is the Moodle

platform on which the web-based course of the study operates. Moodle stands for

Modular Object-Oriented Dynamic Learning

Environment. Moodle is an intuitive, template-based, open-source system. It

allows teachers to manage lessons, assignments and quizzes and also keeps

automatic log reports of each student (Brandl, 2005).

Moodle allows the integration of many resources in

web-based distance courses. Among the resources that Moodle offers are

text-based or html-formatted documents, audio, video, PowerPoint presentations

and flash-based applications (Ardila & Bedoya, 2006; Brandl, 2005).

Among the testing and assessment strategies, Moodle has the following question

types: multi-choice, true/false, matching, short answer, fill-ins and

open-ended questions.

Ardila and Bedoya (2006) and Brandl (2005)

state that one of the advantages of Moodle as a learning management system is

that the teacher can design lessons that take the

learner step-by-step in the course and the advancement from one lesson to the

other is allowed only if the learner demonstrates mastery in the topic of the

lesson.

Reading in a

Foreign Language

Finally, we want to discuss what it means to read in a

foreign language. Grabe and Stoller (2002) state that reading

goes beyond drawing meaning from the printed page and interpreting it

appropriately. They state that reading encompasses several other

aspects. For example when you read, you search for simple information, you skim

quickly, you learn from texts, you integrate information and, if you need to

write, you search for the information needed to write, you critique the texts

you read and finally you can read for general understanding. A proper

definition of reading must take into consideration the fact that reading

implies several processes which make it an active and fluent activity.

Therefore, Alderson (2000) and Grabe (1999, 2000) (as

cited in Grabe & Stoller,

2002, p. 17) define reading as a rapid, efficient, interactive, strategic,

flexible, evaluating, purposeful, learning, and linguistic process that makes

reading a fluent activity.

The Study

This was a descriptive and exploratory case study with

a holistic and interpretative approach as defined by Creswell (2007) and Yin

(2003), which derived from a major study that aimed at exploring the effect of

the modality of instruction, (face-to-face and web-based distance learning) on

a reading comprehension course in English. The objective of this minor study

was to explore the different perceptions students had about an English reading

comprehension course in a web-based modality.

Context

The exchange of knowledge with other universities

around the world has become an issue for the Universidad de Antioquia

(Colombia) and foreign languages play a key role. As a strategy to accomplish

this objective, the university has implemented a certification of foreign

language proficiency. Students can certify linguistic competence either by

taking a proficiency test or by taking face-to-face or web-based distance

courses.

In order to meet the foreign language requirement

established by the institution, a group of teachers from the school of

languages designed an English reading comprehension course for graduate

students in a web-based distance modality. It is a 120 hour completion course.

It has 5 modules, the first three modules last 30 hours each, the fourth module

lasts 20 hours and the fifth lasts 10 hours. The course explores topics such as

words and their meaning, reading strategies, development of reading skills,

methods of text organization and critical reading and includes different tools

such as forums and chats to discuss course content, videos to provide

explanations about the topics and content of the course, questionnaires and

links to other web-sites to provide exercises and practice. At the end of each

module there is an exam to check students’ learning process.

Participants

The students who participated in this study were from

the school of law. We decided to carry out this research study with these

students because they were the next to take the reading comprehension courses

(web-based and face-to-face) offered by the School of Languages to certify

language competence. There were 38 students, 13 men and 25 women registered in

the web-based course. Their ages ranged from 23 to 44. They were enrolled in

different graduate programs such as criminal law, family law, and

administrative law. Their experiences learning English and taking web-based

distance courses were very limited. They reported in the interviews, focus

groups and questionnaires that they had studied English in high school and some

of them had taken basic English courses in language

institutes. Regarding their experience taking web-based distance courses, only

two students said they had taken courses in this modality of instruction

related to other areas different from learning English.

Data

Collection

Through the development of the English reading

comprehension course in the web-based distance modality, we gathered data from

three different instruments: a questionnaire, two in-depth interviews and two

focus groups, in order to carry out triangulation and have saturation of data

(Creswell, 2007; Yin, 2003). Before participating in the study, we used a

consent form in which we informed the students of four aspects: 1) the

participation in the study was optional, 2) they could leave the study whenever

they wanted, 3) the information gathered would be used for research purposes

only, and 4) their participation in the study would not affect their physical,

academic and working well-being.

Although the instruments were designed to learn of the

students’ use of reading strategies, motivation, and perceptions such as

difficulties with the platform, time invested material and the role of the

teacher, we decided to use only the information regarding to the perceptions

the students had about the web-based distance course for the purpose of this

study. The questionnaire, the focus groups sessions and the in-depth interviews

took place in Spanish in order to make sure that students understood and

answered the questions clearly and felt comfortable sharing their perceptions

and feelings towards the course. The students’ opinions and perceptions

were translated into English to be used in this paper as evidence of our research

study.

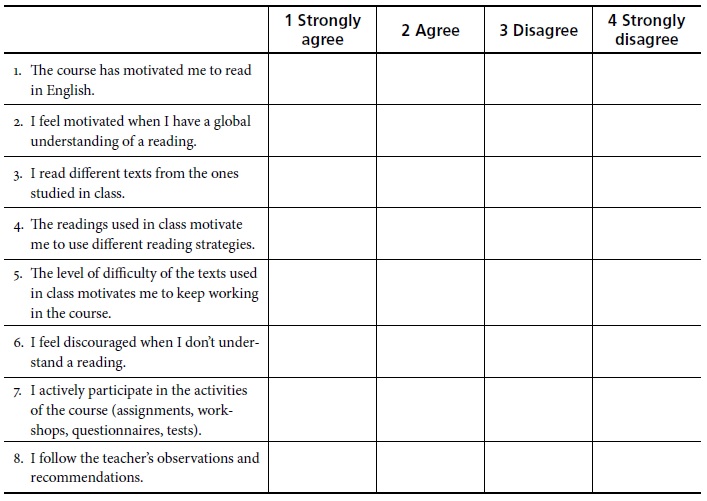

The questionnaire included three types of questions: a

Likert scale from 1 to 4 where 1 was strongly agree

and 4 strongly disagree, open and close ended questions, and multiple choice

questions. The questionnaire was published on the platform of the course, where

the students could download it, fill it in, and upload it again to the

platform. In other cases, the students sent the questionnaire to the

teacher’s e-mail address (see Appendix A).

When the course ended, we carried out two focus group sessions

with approximately 12 students per session in order to obtain information

related to their perceptions of the process: the platform, the teacher, the

contents, their motivation, their reading comprehension process, among others.

These focus group sessions were guided by a moderator who belonged to the

research team. There were also two observers who took notes. These discussions

were tape recorded and each of them lasted around one hour and a half (see Appendix B).

Finally, we conducted two in-depth interviews with two

students we considered as key respondents (see Appendix C).

We selected them as key respondents because the opinions they gave us during

the focus group sessions were neither very positive nor very negative towards

the course. We used in-depth interviews because we wanted to explore deeply the

informants’ opinions about the course (Mertler,

2006). The interviews were also semi-structured because we used a guide with

themes but if new questions emerged during the conversation they were included

freely. The interviews were carried out by one of the members of the research

group and they lasted around 30 minutes. The students participated in the focus

groups and the interviews voluntarily. The sessions were face-to-face and audio

recorded.

Data

Analysis

Focus groups and in-depth interviews were tape

recorded, then transcribed. We read the transcriptions and the answers from the

questionnaire to find patterns. We met once a week with the purpose of

comparing the patterns identified previously. We found recurring themes which

further turned into broad categories based on the saturation of data and the

triangulation of our interpretations (Freeman, 1998; Alttrichter,

Posch & Somekh, 1993).

Findings

As already mentioned, our study focuses on identifying

the perceptions or opinions of the students after participating in a web-based

distance course. For the purpose of this study, we define perception as the

process of attaining under- standing of reality by organizing information

gathered through the senses. This process helps us understand the world and

also helps us recognize objects and events with clear locations in space and

time (Pomerantz, 2006, pp. 50-70).

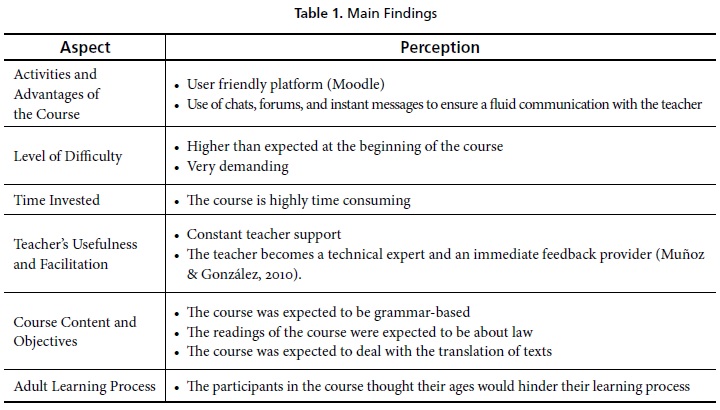

We found six main topics of student perceptions

concerning the course: its content and objectives; its level of difficulty, the

time invested, the role of the teacher and adult learning. We summarized the

findings from our study in Table 1.

Perceptions about

the Tools, Activities and Advantages of the Course

The participants in our study reported several

perceptions about the tools, activities and advantages that the web-based

distance course offered. After taking the course, the students mentioned that

the platform has several positive features: it was user friendly and the

communication with the teacher was fluid. They pointed out the use of the

forum, the chat and the e-mail in order to discuss topics related to the course

content, to share knowledge, to ask questions and to obtain feedback from the

teacher and sometimes from other students. However, some students reported that

sometimes the e-mail was more effective than the chat for communication. They

also highlighted the implementation of tutorial videos to explain the content

of the course. For example, Isabel1, a student

of the course, said in an interview: “The course has useful tools:

forums, the teacher, our classmates, the Internet and the online dictionary

(…)” (In-depth interview, October 2009, p. 4).2

The students pinpointed that the course has several

advantages: They indicated that this modality of instruction allows the

students to manage their own time, they do not have to go to a specific place

to attend a class or any other event, the teaching process is personalized

because it is always available on the internet and there is constant and direct

contact with the teacher or instructor. Similarly, King

(2002) and Hannay and Newvine

(2006) state that one of the primary benefits of web-based distance education

is that the student does not have to go to a university campus which represents

saving travel time.

Perceptions about

the Level of Difficulty

At the beginning of the course the students had the

perception that the level of difficulty would be low, but after having taken

the course, they realized the level of difficulty was higher than expected.

They reported that the number of questionnaires and activities was high.

Although the students perceived the course as very

demanding, the participants felt highly motivated to take other courses in the

same modality of instruction because of the benefits web-based courses

represent, for example, saving time and money as they did not have to go to a

specific place at a specific moment. Pedro wrote this comment on the

self-evaluation format: “I thought the course was going to be easier or

less demanding and at the end I realized it was not. However, I save time

because I don’t have to go anywhere” (self-assessment format, June

2009, p. 3).

The participants said that the level of English

expected in the course was high and suggested a previous vocabulary unit to

perform well in the reading comprehension course.

Perceptions about

the Time Invested

Generally, the students thought that a web-based

course would be less time consuming than a face-to-face course. The students

reported the importance of working in the course every day; they suggested that

the course should have lasted more than six months. For instance, Claudia

reported the following in a focus group: “The course was very time

consuming. It was necessary to spend a long time [at least two hours daily] in

the activities, exercises, and in the personal activities” (Focus group

1, July 2009, p. 19).

The students pinpointed that they invested more time

in this course than in their graduate program. They also mentioned that they

learned to manage their own time to do the activities and questionnaires and to

participate in forums and chats. They suggested this course should last at

least one year, to be taken during their graduate studies.

Perceptions about

the Teacher’s Usefulness and Facilitation

When facing a web-based course, the students thought

that the teacher’s support was insufficient and that they had to work on

their own and had to be autonomous. In this course the students reported the

constant teacher’s support that motivated them to do all the activities.

For example, Luciana mentioned the following in an interview: “I thought

that I would not have very good support from the teacher, but I realized that

the support was excellent” (Focus group 2, July 2009, p. 14).

They also mentioned that because the teacher is

available to answer the students’ questions, the learning process is

perceived as personalized. For instance, María

said in one of the focus group sessions:

I could ask for

help as many times as I wanted to and the teacher answered as many questions as

I asked. (…) in web-based courses you can develop individuality, in

face-to-face courses you cannot say that you do not understand the texts

because the classmates might get bored… in the web-based course you can

have such communication between the teacher and the student. (Focus group 1,

July 2009, p. 14)

In connection to this, Muñoz and

González (2010) state that teaching in web-based environments represents

new roles for teachers; they have to become technical knowledge experts,

immediate feedback providers, interlocutors between teachers and students, they

have to advise how to manage time and they have to become constant motivators.

They also state that these new roles are a challenge not only for regular EFL

teachers but also for those who have specific training in the use of learning

platforms. Similarly, Zhang and Cui (2010) in a survey study carried out in

China found that participants in web-based courses perceived the

teachers’ role as consisting of helping learners to learn effectively by

offering students help or telling them what to do, discussing their progress

and telling students about their difficulties. The teacher is perceived as a

key aspect in web-based distance courses, the teacher is responsible for

providing feedback.

Perceptions about

the Course Content and Objectives

The participants developed different perceptions of

what the course and its contents would be about. Some students expected: 1) to

learn the verb to be; 2) they believed that the readings of the course were

going to be related to law; and 3) some of them expected a translation course.

Some of these perceptions remained during and after they finished the course

and some of them changed at the end. The students complained because they said

they did not achieve their expected objectives in six months, for example, to

translate texts accurately; to understand a reading word by word, to acquire

listening skills and to learn the language holistically. For example, Martha

expressed the following in a focus group:

I could not achieve

the objective, we could not! I mean, I learned to read a little, but if I have

to do an exam about a text in this moment I can translate it but not quite

accurately, just by parts. (Focus group 1, July 2009, p. 3)

After taking part in this course, the

participants’ perceptions of the course content and objectives changed

because they realized the real focus of the course was reading comprehension,

improving vocabulary and providing students with reading strategies not only in

English but also in Spanish, instead of translation and the study of grammar.

Eduardo expressed in one the focus group sessions the usefulness of the

strategies acquired in the course to read in Spanish: “I must read so

many resolutions, so I decided to use scanning strategy to choose what was

useful and what was not, so I read quicker. (…) these techniques are

helpful for everything you must read” (Focus group 1, July 2009, p. 15).

As Baker (1986, in Hannay & Newvine,

2006, p. 2) argues, one of the major drawbacks of web-based distance education

is that the separation of the instructor and the students can cause problems

comprehending course information, for example, the content or objectives and

course expectations are often not clear.

Perceptions About the Adult Learning Process

Some students who participated in the web-based course

had strong perceptions about how age affects their successful performance in

this modality of instruction and their learning of English.

They believed their ages were not appropriate to learn

English. They felt sure young students and children are more skilled than

adults in the process of learning a foreign language. They kept this belief

throughout the course.

The students in this course were not comfortable with

the results of the process because they thought their ages implied less memory,

less reading comprehension abilities and more time consumption to understand

something. For example, Gustavo mentioned the following in an interview:

“An adult does not learn the English language as easy as youngsters or

children” (In-depth interview, October 2009, p. 2).

Regarding these perceptions, Tyler-Smith (2006) states

that adult on-line learners have certain advantages and disadvantages over

their younger counterparts for learning. Some of the advantages the author

mentions, based on Knowles (1984, p. 12), are that adult learners’ life

experience “becomes an increasing resource of learning”; they also

apply what they learn and learn on a problem solving approach. In addition,

adults base their internal motivation on “self-development, career

advancement and achievement”, therefore, their

motivation is not based on getting passing grades or qualifications to obtain

specific employment.

However, according to the Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller & Chandler, 1994; Sweller,

1999; and Sweller, Paas

& Renkl, 2003, cited in Tyler-Smith, 2006), adult

learners could be confronted with some limitations regarding e-learning as

“having limited digital literacy experience and being generally far less

adept at decoding the multimedia interfaces involved with e-learning than their

younger counterparts” (Tyler-Smith, 2006, p. 76). This is also supported

by Eshet-Alkalai (2004, cited in Tyler-Smith, 2006),

who explains that:

Digital literacy

involves more than the ability to use software or operate a digital device; it

includes a large variety of complex cognitive, motor, sociological and

emotional skills, which users need in order to function effectively in digital

environments. (p. 78)

Tyler-Smith (2006), based on Whipp

and Chiarelli (2004, p. 6), also highlights that not only

adult learners, but every first time e-learner faces multiple challenges such

as “technical access, asynchronicity,

text-based discussions, multiple conversations, information overload and

isolation” (p. 78).

Similar to these authors’ ideas, the participants

in our study attributed their difficulties with technology to their ages. They

said adults are not accustomed to technology, computers and to web-based

distance courses. They believed that a young person who has more technological

skills performs better in this kind of modality than someone who is a grown up

and is not used to technology at the same level.

We also noticed that students who had negative

perceptions about technology did not trust it at all. Although the learners had

different sources of communication in the Moodle platform such as chats and

forums, some of them continued sending their workshops or their messages to the

teacher by e-mail because they were more accustomed to using it in their jobs

and in their everyday lives.

Conclusions

and Implications

The use of tools such as chats, forums and the use of

e-mail as well as the inclusion of video tutorials built positive perceptions

towards the web-based course. On the one hand, the implementation of different

tools allows the students to communicate with the teacher, increases the sense

of support and decreases the sense of loneliness and abandonment because the

teacher and other students can provide feedback and discuss topics related to

the content of the course. On the other hand, the use of tutorial videos

provides the students with visual, illustrative and graphic explanations of the

course content.

Web-based education entails several benefits such as:

saving time and money because people do not have to travel to attend classes at

a specific time or in a particular place, which motivates them to undertake

studies in this modality of instruction. We noticed that people prefer saving

time and money rather than paying attention to the course level of difficulty.

Similarly, web-based courses are time consuming and they help students develop

time management skills and a big sense of responsibility.

Hannay and Newvine (2006) in a study comparing distance learning and

traditional learning found that the participants in distance learning courses

preferred those courses because they had other commitments that limited their

ability to take classes in the traditional format. They also found that the

participants in distance courses felt highly attracted to these courses because

they save time and money since they do not have to travel to take classes.

Moreover, teacher support is not minimized in

web-based courses as students thought at the beginning of the course. The

students felt that the teacher was available 24/7 because s/he answered the

messages, graded the exercises, and posted messages on the forums to promote

students’ interaction and participation on a daily basis.

Therefore, it is paramount for pre-service and

in-service teachers to be well-prepared to play the role of constant advisors,

to promote the use of each tool and answer students’ doubts to decrease

students’ anxieties and misconceptions about web-based courses.

For the students to self-assess their performance and

measure the level of achievement of their goals, the course content and

objectives must be explained and discussed from the beginning. It is important

to design an induction unit for web-based courses that can be either

face-to-face or web-based distance to make sure students have a concise idea of

the course content and objectives. The induction unit can also deal with

aspects such as the basic features of the course, the platform and the

evaluation proposal. The possible result of the induction program is to lessen

students’ anxiety and improve their performance in the course.

Although the students thought that certain ages

prevented them from learning English in a web-based environment, the Moodle

platform is user friendly, is intuitive, and offers multiple tools that allow

students to get accustomed to using it very quickly. Besides, the course

objective is to provide students with strategies to comprehend written texts in

English; therefore, the course can be taken by everybody regardless of age and

linguistic background. The main concern was not age, but the fact that it was a

new learning experience, both linguistically and technologically. This kind of

courses are a new option for students to continue their preparation to better

compete in the current global world and to have access to diverse and updated

information.

Limitations

of the Study

During the development of this research study, we

faced different limitations that need to be taken into consideration for

further research. The first limitation deals with the need to research the

perceptions of web-based distance education of a larger number of students,

including students from different academic programs, and taking into account

more than one group. The act of researching only one group from a specific

academic program limits the assertions made in the findings.

The second limitation we faced relates to the fact

that this study emerged from a major study. The objective of that study was to

research the effect of face-to-face and web-based English reading comprehension

courses in graduate students at the Universidad de Antioquia. Accordingly, the

data collection techniques were addressed to explore students’ interaction,

motivation, perceptions and strategies used in these two modalities of

instruction. Although the focus of the major study was not only to search the

students’ perceptions about this modality, we decided to conduct this

minor study because we observed and could infer the different perceptions the

participants had when we collected and analyzed the data. For further research,

we considered it necessary to design data collection instruments that directly

addressed the subject matter and that could deeply explore students’

perceptions about web-based distance courses and how these perceptions change

throughout the course.

Finally, we think the fact that students had to take

this course as a requirement in order to continue their graduate studies

changes their perceptions not only of web-based distance education, but also of

English reading comprehension courses. It would be interesting to explore in

further research the perceptions students have about this kind of courses in

circumstances where they take them voluntarily.

1. We changed the

names of the informants in this paper in order to keep confidentiality.

2. The interviews,

the questionnaires and the focus groups were conducted in Spanish. A

translation into English is provided for the purpose of this publication.

References

Altrichter, H., Posch, P., & Somekh, B. (1993). Professors investigate their

work: An introduction to methods of action research. London: Routledge.

Ardila, M., & Bedoya, J. (2006). La

inclusión de la plataforma de aprendizaje en línea MOODLE en un

curso de gramática contrastiva español, inglés. Íkala, 11(17), 181-205.

Brandl, K. (2005).

Are you ready to ‘MOODLE’? Language

Learning and Technology, 9(2), 16-23.

Conrad, D. (2002). Deep in the hearts of learners: Insights into the

nature of online community. Journal of

Distance Education, 17(1), 1-19.

Creswell, J. (2007). Qualitative

inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Facundo, A. (2002). La educación superior a distancia/virtual en Colombia. Retrieved from http://portales.puj.edu.co/didactica/PDF/Tecnologia/EducacionvirtualenColombia.pdf

Freeman, D. (1998). Doing teacher

research: From inquiry to understanding. Boston, MA: Heinle

& Heinle.

Grabe, W., & Stoller, F. (2002). Teaching and

researching reading. England: Pearson Education.

Hannay, M., & Newvine, T.

(2006). Perceptions of distance learning: A comparison of

online and traditional learning. MERLOT Journal of online learning and teaching, 2(1), 1-11.

Hiltz, S., & Turoff, M.

(2005). Education goes digital: The evolution of online

learning and the revolution in higher education. Communications of the ACM, 48(10), 59-64.

King, F. (2002). A virtual student. Not an

ordinary Joe. The Internet and Higher

Education, 5(2), 157-166.

Marcelo, C., Puente, D., Ballesteros, M.,

& Palazon, A. (2002). E-learning, teleformación:

diseño, desarrollo y evaluación de la formación a

través de internet. Barcelona: Gestión 2000.

Mertler, C. (2006). Action research:

Teachers as researchers in the classroom. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications.

Moore, J., Dickson-Deane, C., & Galyen, K. (2011). E-Learning, online learning and distance learning environments: Are

they the same? The Internet and Higher

Education, 14, 129-135.

Muñoz, J., & González, A. (2010). Teaching reading comprehension in English in a

distance web-based course: New roles for teachers. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 12(2),

69-85.

Pomerantz, J. (2006). Perception: Overview. In L. Nadel (Ed.), Encyclopedia

of Cognitive Science (pp. 527-537). London: Nature Publishing Group.

Sampson, N. (2003). Meeting the needs of distance

learners. Language Learning &

Technology, 7(3), 103-118.

Stepp-Greany, J. (2002). Students’ perceptions on language learning in a technological

environment: Implications for the new millennium. Language Learning & Technology, 6(1), 165-180.

Tyler-Smith, K. (2006). Early attrition among first time eLearners: A review of factors that contribute to drop-out,

withdrawal and non-completion rates of adult learners undertaking eLearning

programs. MERLOT

Journal of online learning and teaching, 2(2), 73-85.

Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: Design and

methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Zhang, X., & Cui, G. (2010). Learning perceptions of distance

foreign language learners in China: A survey study. System, 38(1), 30-40.

About the

Authors

Érica Gómez Flórez is a full time teacher at Universidad de Antioquia.

She also holds a master in language teaching from the University of Rouen

(France). She is a member of the EALE research group at Universidad de

Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia.

Jorge Eduardo

Pineda is a full time teacher at Universidad de Antioquia.

He holds a master in language teaching from Universidad de Caldas (Colombia).

He is a member of the EALE research group at Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia.

Natalia Marín García is a foreign language student at Universidad de

Antioquia. She is a member of the EALE research group at Universidad de

Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia.

Appendix A: Motivation

Questionnaire

Universidad de

Antioquia

Escuela de Idiomas

Questionnaire about motivation

The information you provide in this questionnaire will

only be used for the purposes of this study and will not have any effect on the

final result of the course.

Please mark from 1 to 4 whether you agree or disagree

with the following statements.

A. Motivation

9. The teacher has motivated me because

__________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________

10. I feel discouraged about the teacher and about the

course because

__________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________

B. The course

1. Have you had any trouble when using the platform?

__________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________

2. What kind of problems have you experienced?

__________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________

3. How much time do you invest in the course every

week? (choose 1)

a. Less than 5 hours____

b. Between 5 and 10 hours____

c. More than 10 hours____

4. What resources do you use besides the ones offered by the platform to

achieve your objectives

a. Online resources____

b. Help from other people____

c. E-mail the teacher____

d. E-mail to other participants of the course____

e. Dictionary online____

f. Paper-based dictionary____

g. Online translator____

5. When you have a question about the topics studied

in class, you

a. Ask the teacher____

b. Ask another participant in the course____

c. Use the

dictionary or the material available in the platform____

6. When you work in the platform, you

a. Read the

theory, see the explanations first and then you take the questionnaires____

b. Take the

questionnaires without checking the explanations____

c. Follow the order proposed in the course____

d. Follow a

different order from the one proposed by the course____

e. Print the

exercises, answer them and later answer the

questionnaires in the platform____

f. Save them

in a Word document, answer them and later answer the questionnaires in the

platform____

g. Answer the questionnaires in the platform____

C. Reading

strategies

Please mark from 1 to 4 whether you agree or disagree

with the following statements

Universidad de Antioquia

Escuela de Idiomas

Guiding questions

a. How would you

define the experience of taking this Reading comprehension course?

b. What advantages

and disadvantages have you found in this course?

c. How would you

define the role of the teacher in this course?

d. Do you think

your reading comprehension skills have improved after taking this course?

e. Do you feel

motivated to read other English texts different from the ones studied in class?

f. Do you used the reading

strategies studied in class in you graduate program?

g. What is your

opinion of the distribution of the content in the platform?

h. What would you

change about the course if you were going to take it again?

Appendix C: In-Depth Interview Guide

Universidad de

Antioquia

Escuela de Idiomas

Interviewer’s

name:_____________________________________

Interviewee’s

name:_____________________________________

Date:_______ Place:______

Recommendation: Let interviewees speak spontaneously. Help them get

involved in the activity. Foster a relaxed environment.

Guiding questions

1. Tell us

something about your experience learning English before taking this course.

2. What is

your opinion of the learning of English after taking this course?

3. What

difficulties did you experience when taking this course?

4. What is

your opinion of the resources offered by the platform?

5. What would

you change about the course?

6. Tell us

something about the steps you followed when taking the exams at the end of each

unit.

7. How did you

use the communication tools offered by the platform? (chat,

forums, e-mail, instant messages)