Promoting Learner Autonomy Through

Teacher-Student Partnership Assessment in an American High School: A Cycle of

Action Research

El papel

de la evaluación negociada en el desarrollo de la autonomía del

estudiante en la escuela secundaria norteamericana: un ciclo de

investigación-acción

Édgar

Picón Jácome*

Universidad de

Antioquia, Colombia

*edgar.picon@idiomas.udea.edu.co

This article was received on October 15, 2011, and

accepted on May 30, 2012.

In this article I present some findings of an action

research study intended to find out to what extent a teacher-student

partnership in writing assessment could promote high school students’

autonomy. The study was conducted in a U.S. school. Two main action strategies

in the assessment process were the use of symbols as the form of feedback and the

design of a rubric containing criteria negotiated with the students as the

scoring method. Results showed that the students developed some autonomy

reflected in three dimensions: ownership of their learning process,

metacognition, and critical thinking, which positively influenced an

enhancement of their writing skills in both English and Spanish. Likewise, the

role of the teacher was found to be paramount to set appropriate conditions for

the students’ development of autonomy.

Key words: Action research, assessment for learning, learner autonomy, rubrics,

summative assessment.

En este

artículo presento hallazgos de una investigación-acción

cuyo objetivo era averiguar en qué medida una forma alternativa de

evaluación negociada promovería la autonomía de los

estudiantes. El estudio se realizó en una escuela secundaria

norteamericana. Las principales estrategias de acción fueron el uso de

símbolos en la retroalimentación y la inclusión de

criterios negociados con los estudiantes en el diseño de una

rúbrica que se utilizó como instrumento de evaluación y

calificación. Los resultados mostraron que los estudiantes desarrollaron

su autonomía en tres dimensiones: apropiación de su proceso de

aprendizaje, metacognición y pensamiento

crítico, lo que influenció positivamente el desarrollo de sus

habilidades de escritura tanto en inglés como en español.

Asimismo se encontró que el papel del profesor es de vital importancia

para establecer condiciones propicias en el desarrollo de la autonomía

de los estudiantes.

Palabras clave: autonomía

del estudiante, evaluación formativa, evaluación sumativa, investigación-acción,

rúbricas.

Introduction

In his work, Assessment

of autonomy or assessment for autonomy?, Lamb (2010) elaborates on the

notion of assessment that is designed to foster learner autonomy. Supporting

his arguments with the work of Black and Williams (1998, 2005, cited in Lamb,

2010) and Black and Jones (2006, cited in Lamb, 2010), Lamb comes to the

conclusion that “assessment for learning is designed to develop the

necessary capacities for becoming an autonomous learner with a view to

improving learning through better self-monitoring and self-evaluation leading

to better planning” (p. 100). The author defines assessment for autonomy

as “any assessment for which the first priority in its design and

practice is to serve the purpose of promoting pupils’ autonomy” (p.

101).

This article presents my effort within that same

spirit: designing assessment procedures with the objective of enhancing

students’ autonomy. I highlight three aspects of the study that I

consider especially significant: (1) the foreign language setting in which it

took place that might provide valuable insight for schoolteachers to try out

similar actions; (2) the usefulness of rubrics to help teachers make grading

practices formative and provide space for them to share their power with the

students; and (3) the fact of the study being inserted in a cycle of action

research, which places research practices within the reach of teachers.

The Assessment

System

The assessment system in this project corresponds to a

teacher-student partnership type1 in which

students participated in the creation of the scoring instrument and as active

co-evaluators.

Assessment had both a formative and a summative

purpose within a conscious intention on my part to promote students’

autonomy. In the following paragraphs, I expand the key concepts that support

this assessment procedure.

Key Terms that

Define Teacher-Student Partnership Assessment

Assessment and evaluation are terms sometimes used

indistinctly referring to the same processes. Consequently, I find it necessary

to clarify what those terms mean within the framework of my project. In doing

so, I take the ideas of Williams (2003) for whom assessment designates the following four related processes:

deciding what to measure, selecting or constructing appropriate measurement

instruments, administering the instruments, and collecting information. Evaluation, on the other hand,

designates the judgments we make about students and their progress toward

achieving learning outcomes on the basis of assessment information (p. 297).

Brown (2004) expands assessment definition asserting that it is a continuous

process that takes place either on a formal or an informal basis.

Assessment and evaluation can be classified according

to the focus of power. For instance, teacher-student partnership, a concept

developed by Bratcher and Ryan (2004), is a type of evaluation in which both

teachers and students work together. Some key words that describe this approach

to grading are input (from both sides), negotiation, and flexibility. Power is

not concentrated on the teacher but shared with the students and there is a

continuous combination of different student and teacher roles in every step of

the process. Bratcher and Ryan assert that this type of evaluation has the

advantages of students “investing in grades in which they feel they have

had input” (p. 102).

Assessment can also be classified according to its

purpose—when it is administered and how its results are used—as

either formative or summative. Formative assessment aims at measuring

achievement within the process and helping students to improve their skills.

Contrariwise, summative assessment measures results at the end of a process

mostly in order to make decisions (Angulo-Delgado,

2002; Arias, Estrada, Areiza & Restrepo, 2009; Bachman & Palmer, 1996; Brown, 2004; Ekbatani, 2000; Himmel-Köning,

Olivares-Zamorano, & Zabalza-Noaim,

2000; and Lippman, 2003). This study takes place

within a context in which grading plays an important role and therefore

assessment has a summative purpose. However, the action strategies applied had

the intention to make it formative by providing space for feedback—among

other strategies—which is expanded in the following section.

Feedback

Feedback is inherent to formative assessment. In fact,

Goodrich-Andrade and Boulay (2003)—citing

Cooper and Odell (1999)—define assessment as “ongoing feedback that

supports learning” and stress the need of providing students time for

reflection upon and self-assessment of their pieces of writing before they

submit a final draft (p. 21). Arias et al. (2009), in addition, assert that

there must be a continuous and systematic process of feedback for formative

assessment to be successful.

One of the forms of feedback that I used in this study

is in agreement with Rutherford’s arguments in favor of the teaching of

grammar rules. Rutherford (as cited in Edlund, 2003,

p. 369) argues that adult learners go into a process of comparison between the

two grammatical systems in which they make and test theories about how L2

works. The process of producing such theories can be facilitated by what he

calls “grammatical conscious raising” or C-R. C-R is the supplement

of data needed during the theory testing occurring in the L2 learner’s

mind. Edlund (2003) thus points out that this theory

justifies the practice of selective marking of errors, which was applied in

this study as part of the action strategies.

The other form of feedback was the use of analytic

rubrics for self-evaluation. Rubrics have been found to be useful to provide

both formative and summative feedback in a systematic and effective manner (see

O’Malley & Valdez-Pierce, 1996; Mertler,

2001; Moskal, 2000; and Stevens & Levi, 2005).

While the use of symbols for self-correction emphasized syntax and vocabulary,

the rubrics included aspects of the discourse component that complemented the

linguistic construct evaluated2. In the

following section, I expand the definition of rubric.

Rubrics

Mansoor and Grant (2002) define a rubric as “a scoring device that

specifies performance expectations and the various levels at which learners can

perform a particular skill” (p. 33). This is the concept of rubric that

applies to the scoring method employed in the study, and the same that authors

such as O’Malley and Valdez-Pierce (1996), Moskal

(2000), Mertler (2001), and Stevens and Levi (2005)

are in concordance with.

Rubrics are pertinent for criterion reference

assessment since they provide the space for assessment criteria to be

explicitly stated (Bachman & Palmer, 1996; Brown, 2004; Genesee &

Upshur, 1996; Himmel-Köning et al., 2000).

Likewise, they are coherent for the scoring of constructed response assessments

(Brown & Hudson, 1998) such as the short compositions that the students

produced for this study. Rubrics need to be closely connected to the task that

they will score and the task should clearly state the specific and detailed

information that the students will need in order to complete it successfully

(see O’Malley & Valdez-Pierce, 1996). Rubrics can be easily accessed

and downloaded from internet sites. However, following the ideas of Hewitt

(1995), I decided to design the rubrics along with my students in order to

facilitate discussion and reflection about the criteria.

In the words of Black and Jones (2006), “an

assessment activity can help learning if it provides information to be used as

feedback” (cited in Lamb, 2010, p. 100). Teacher-student partnership is

consequently assessment for learning. Following Lamb’s (2010) definition

of assessment for autonomy, we can finally assert that the assessment system

applied in this research project had the characteristics of such assessment

practice. Next, I elaborate on the definition of learner autonomy.

Learner

Autonomy

In the words of Benson (2010), when we talk about

autonomy in language learning, we usually “refer more to a certain kind

of relationship between the student and the learning process.” (p. 79).

The author asserts that the term that best describes this relationship is

control. Following this order of ideas, Benson offers a framework to measure

learner autonomy. This framework is represented by three poles of attraction

among which various degrees of control over learning could be determined: those

poles are student control, other control and no control (p. 80). Learner

autonomy could thus, to some extent, be evaluated in relation to a student

level of control, at a certain point in time, over dimensions of the learning

process such as “location, timing, pace, sequencing and content of

learning” (p. 79). From that perspective, evaluation being another

dimension of the learning process, one might establish students’

development of autonomy in terms of the student level of control over it at

different points in time.

Dimensions of

Learner Autonomy

Previously, in his well-known work The Philosophy and Politics of Learner

Autonomy, Benson defines three dimensions of autonomy—technical,

psychological, and political. The technical dimension concerns the techniques and

strategies that help students to become owners of their learning process i.e.

individuals with the capacity to manage their own learning. In order to

facilitate its development, it is paramount to promote self-directed learning,

which includes providing students situations for them to learn how to learn (Benson, 1997).

Concerning the psychological dimension, Benson

considers that it involves the development of traits in the individuals that

leads them to become more responsible, develop critical thinking, and take

control over their learning process. Learners are the ones who construct

knowledge starting from their social interaction and continual self-evaluation

that should lead to self-awareness.

With regard to the political dimension, Benson asserts

that it relates to the learners’ ability to deal with power issues within

the teaching-learning process. Benson highlights that whether the teacher takes

full control of the power within the classroom or whether s/he decides to share

it with the students is a political decision that affects learning completely.

In the same way, Benson and Voller (1997) affirm that

learner autonomy “can be thought of in terms of (…) redistribution

of power among participants in the social process [of education]” (p. 2);

hence, the development of a more political dimension of learner autonomy could

be facilitated by teaching methodologies in which students have the opportunity

to participate in decision making.

The role of the

Teacher

Many authors have emphasized the role of teachers in

the promotion of learner autonomy (see Benson, 1997; Ellis, 2000; Lamb, 2010; Little, 1995; O’Malley & Valdez-Pierce, 1996; Voller, 1997; and Wenden, 1991).

In this sense, the teacher is a facilitator, counselor or guide with a

supportive attitude towards the learner and within a learner-centered

environment; a teacher is willing to release some power over the students in

behalf of their development as independent, able learners. Furthermore, they

have pointed out the possibility to help students develop autonomy by teaching

them strategies to learn the language, rather than transmitting the language,

and fostering self-reflection and critical thinking.

Following this rationale, Wenden

(1991) examines the features of autonomous learners, shows how those

characteristics are linked to learning strategies, and proposes activities to

teach those learners. In her analysis, the author uses the typologies of

learning strategies defined by Chamot (1987). Wenden groups learning strategies, according to their

function in the learning process, as cognitive and self-management.

Self-management, which corresponds to O’Malley

and Chamot’s (1990) metacognitive strategies,

include three main functions: planning, monitoring, and evaluating. Planning

has to do with specifying matters such as time, place, individuals, resources,

forms, and reasons to carry out an activity or to state a task leading to

learning the language. Monitoring has to do with constantly identifying

failures in the act of communicating while the communication is taking place.

Finally, evaluating has to do with reflecting on the development of the

strategy planned and its pertinence in terms of learning.

Besides metacognitive strategies, O’Malley and Chamot’s (1990) typology point out two more main

types: cognitive strategies and social/affective strategies. While cognitive

strategies are “more directly related to individual learning tasks and

entail manipulation or transformation of the learning materials” (p. 8),

social/affective strategies are related to cooperative processes of learning

and the control of affective matters that affect the language learning process.

A failure identified in this study is that learning

strategies were not explicitly taught; they were identified in the analysis,

however. In my belief, teachers have a special responsibility to help students

develop autonomy in a more political dimension. Training students to

self-evaluate against clear criteria, and giving them the opportunity to act as

co-evaluators, is a way both to help them foster metacognition in L1 and

L2—English and Spanish in this study—and to develop skills in order

to fight for their rights; a movement of evaluation practices towards fairness

and democracy (Shohamy, 2001).

Method

This study is framed within a cycle of action

research. Action research has been found to be especially appropriate for

educational improvement (see Altrichter, Posch & Someck, 1993; Selener, 1997; Burns, 1999). One of the goals of action

research is to involve teachers in reflection upon and within their practice so

that they (1) become aware of the possible factors that might constitute a

particular question/problem encountered in their day-by-day teaching lives, (2)

better understand those factors, and (3) plan and carry out strategies in order

to find answers to and/or solve that question/problem. Burns (1999) found that

doing action research enabled teachers “to engage more closely with their

classroom practice as well as to explore the realities they faced in the process

of curriculum change” (p. 14). In addition, it produced “personal

and professional growth” and increased teachers’

“self-awareness and personal insight” (p. 15).

The Starting Point

My starting point for this project came from my

experience teaching Spanish as a foreign language in high school in the U.S.

English was the mother tongue for the majority of the students3 and Spanish classes took place two hours daily. High

school students needed to complete at least one year of a foreign language in

order to graduate and Spanish was the favorite one due to the Hispanic

population growth that was turning some environments bilingual in the U.S.

At the time of this proposal, I was teaching eleventh

and twelfth graders, and the group with which I systematized the experience was

composed of 19 students, eight girls and 11 boys, whose ages ranged from 15 to

18. Relating to their placement in the school, there were 10 seniors and nine

juniors. Two of the students dropped the course.

I had found that many of my Spanish students did not

keep track of their notes and then depended on me or other students to choose

the vocabulary needed for their writing tasks and to correct their grammar

errors. Some students seemed not to have learned the mechanics in previous

classes, made mistakes that they did not know how to correct, and felt

unmotivated towards the writing task.

Many students seemed not to care about the whole

process and to lack clear objectives and/or reasons for studying the language;

although speaking Spanish was considered an advantage for potential jobs in the

future, most students expected to learn it without much effort. The majority

relied on English to communicate in class. As a consequence of these

conditions, some students copied from partners and did not even worry about

learning while others translated whole papers using computer software without

knowing what they had written. The writing activity ended up being of little

value for such students. I believed that the previous situation was directly

related to students’ lack of ownership i.e. lack of autonomy.

I had already applied some of the assessment

procedures that I incorporated into the project with the feeling that they

helped me to become more successful in my teaching. Nonetheless, I had not

taken into account my students in the development of evaluation criteria,

neither had I given self-evaluation much importance in their final grades as I

did in this course.

Action Plan

The main action that I applied in order to cope with

the situation described in the previous section was the implementation of a

teacher-student partnership form of assessment. Two main strategies in this

assessment process were (a) the implementation of self-correction of errors by

using symbols as a form of feedback (see Appendix A) and (b) the design of a

rubric containing criteria negotiated with my students in order to

self-evaluate and grade some of their compositions. The plan would be applied

through different steps including training students both to self-correct their

errors, and self-evaluate against the criteria stated on the rubric. The plan was

intended to fit within my normal teaching activities.

Data Collection

The data collection included my personal journal; a

survey of the students; students’ products, namely two compositions plus

early and late writing samples of theirs and the scoring rubrics used to

evaluate their performance. For the purpose of this article, I took into

account the findings that emerged from the analysis of my journal and the

survey itself in addition to inferences made from the students’ progress

based on the analysis of their scores.

In my personal journal, I described the implementation

of the actions that I had planned and reflected on every step of the process. I

registered in it my interpretations of the outcomes that emerged from the

analysis of the survey and the comparison of self and teacher assessment. I

also recorded my personal opinion in the journal of the students’

performance and progress through the implementation of the strategies, which

gave me the possibility to triangulate my perception with my students’

and to keep track of the chronology of the events.

Twelve students responded to a survey given at the end

of the course. It was a brief survey composed of four multiple choice questions

and an open-ended one aimed to find out the students’ sense of whether

the procedures used had helped them or not in terms of developing strategies

and/ or attitudes towards their process of learning how to write in the foreign

language.

The students wrote, self-corrected, and self-evaluated

two compositions for the purpose of this research: Mi

Escuela and Mi Familia (see Appendix B). In total, thirteen

students’ self-evaluation forms were included in the analysis of the

first composition and eleven in the second one.

Data Analysis

In order to analyze qualitative data, such as

narrative and descriptive events, personal reflections, and open-ended

questions, I carried out inductive-deductive analyses following the steps

suggested by Burns (1999): assembling, coding, comparing and building

interpretations (pp. 156-160).

For the analysis of quantitative data, such as the

comparison between the student’s and the teacher’s evaluation

forms, and the outcomes of the survey, (1) I created charts and tables

comparing the results; (2) I described those results and tried an initial

interpretation through a reflection exercise in which I tried at connecting

them to the main topics of the project; and (3) I carried out inductive

deductive analysis of those descriptions and reflections i.e. I categorized

them too.

I invited my students to participate in the process by

giving me feedback about the different strategies and about the process in

general. At the same time, I asked my students for permission to use their

pieces of writing and signed a compromise letter committing myself to guarding

their anonymity in order to be consistent with the ethical principles of

educational research (Pring, 2004; and Burns, 1999).

Finally, I asked a colleague to act as a critical friend in order to enhance

validity of the data analysis (Altrichter et al.,

1993).

Findings and

Discussion

In this section, I discuss the findings of this study

that intended to analyze to what extent a

teacher-student partnership on writing assessment could promote students’

autonomy. Analysis of the data showed that some development of learner

autonomy resulted from the interaction of the teacher’s role and the

actions taken in this research project. Learner autonomy was thus reflected in

three student features: gaining ownership of their learning process, developing

metacognition, and developing critical thinking.

Gaining Ownership

In the framework of this discussion, gaining ownership refers to

students’ actions, behaviors, or attitudes that showed their movement

towards a more autonomous dimension of learning. Students showed that they had

gained ownership by expressing or showing independence, showing commitment and

responsibility to do the learning activities proposed, participating in

decision making, and expressing their having felt part of the development of

the assessment system.

To start off, some of the students’ responses to

the survey confirmed a positive attitude towards the use of social and

cognitive strategies after having been involved in the project: on the one

hand, 90% of them acknowledged that they were more likely to ask for help

instead of copying their partner’s work; and on the other hand, 60% of

them expressed that they were more likely to use their notes (see Figure 1). I, myself, corroborated such behavior during our

visits to the lab and in other opportunities in class:

…they would

sit next to their partners and ask them for help…I thought that was part

of the plan; they should be willing to ask for help instead of just copying. …Also,

most of the students were using their notes and dictionaries. (Journal, p. 15)

By the same token, 50% of the students agreed that the

activity of self-correcting their own errors helped them to become more

independent and it is particularly significant that one of them expressed that

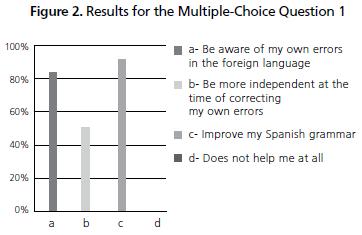

she was more likely to “do better herself”4 after the experience (see Figure 2).

Consequently, since the use of learning strategies implied students’

progress in terms of independence and positive attitudes towards learning, it

also evidenced some development of ownership of their learning process, which

has been associated with learner autonomy (Lamb, 2010; Benson, 1997; Little,

1995; Wenden, 1991).

It seems that the assessment process enhanced most

students’ commitment towards the development of the activities completed

in class. This could be observed in their changing attitudes, keeping on-task,

and expressing pride in their work, as I recorded in my journal.

Generally speaking,

I noticed that most of the students would be concentrated in their

job…With the exception of few students, I felt

that the activity had engaged them. …Another positive aspect I noticed

was that most of them looked proud of their work. They would decorate their

final papers and use fancy font. (Journal, pp. 15 & 16)

Most of the students who showed little motivation and

commitment towards class activities in the beginning of the semester gradually

changed their attitude. Benson (1997) points out that “constructivist

approaches to language learning tend to support ‘psychological’

versions of learner autonomy that focus on the learner’s behavior,

attitudes and personality” (p. 23). He goes on to assert that those

versions “can be seen as promoting qualities in individual language

learners that will be of value in the process of independent language

use” (p. 29).

On the other hand, a more observable behavior leading

to the development of ownership was students’ actual participation in

decision making. Benson and Voller (1997) state that

autonomy can be understood as a right of learners to direct their learning

process; hence, active participation in deciding criteria against which they

were going to assess themselves was evidence of students learning how to take

control of that part of their learning that involves evaluating their

achievement.

It was very gratifying to see that most of them

actually discussed the criteria and gave me feedback in order to design the

rubric. As I recorded in my journal, the majority participated with their

comments, which were very valuable in the design of the assessment instrument

(Journal, pp. 6-11). Likewise, the results from the survey showed that, as a

consequence of participating in the design of the rubric, 70% of the students

felt part of the grading process and 48% felt that they had been taken into

account in decisions that affected their performance (see Figure

3).

The act of participating in the establishment of

something as determinant of power as the grading criteria in a language course

implied a movement towards a more political dimension of autonomy in my

students. As Little (1995) warns:

In formal

educational contexts learners do not automatically accept responsibility for

their learning—teachers must help them to do so; and they will not

necessarily find it easy to reflect critically on their learning

process—teachers must first provide them with appropriate tools and with

opportunities to practice using them. (pp. 176-177)

Because it is a determinant factor for students to

become better able to self-direct their learning within the psychological

dimension of autonomy, in the following section I give special emphasis to the

students’ use of metacognitive learning strategies.

Developing

Metacognition

Metacognition, which relates to mental processes that

involve reflecting, comprehending, interpreting, reexamining, planning,

monitoring, self-evaluating, and, generally speaking, expressing self-awareness

of learning, is very important in the development of autonomy because it

enables human beings to self-manage their learning process. The three main

pieces of evidence found in the data analysis as development of metacognition

in the students were their development of metacognitive learning strategies,

namely, planning, self-monitoring, and self-evaluating. It is important to

clarify that these processes were carried out in English, which evidenced the

role of L1 in scaffolding the development of L25.

The evaluation criteria stated in the

rubric—along with the detailed guidelines for the development of the

task—demonstrated to have been helpful for students to have a clearer

idea of what they had to do in order to be successful in the writing

assignment. Hence, the students’ increased awareness about the general

process of the task must have influenced the fact that most of them planned

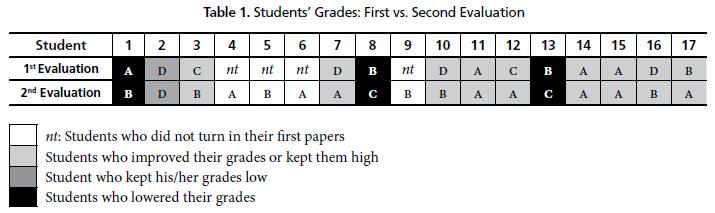

better and thus improved their grades for the second evaluation event. Table 1 shows comparison of the students’ final grades

for the two compositions.

The responses for question 2 of the survey also showed

that 85% of the students found participating in the design of the rubric useful

to better understand what was expected from them (see Figure 3).

According to some of the students’ actual words,

…designing a rubric with the teacher:

Help me understand what I need to include in my

writings

It does make me

know what to expect, what is going to be required and that it is part of the

grading process

I will know what is

expected to be on an assignment that will give me a 100.

An outstanding positive result of students’

participating in the design of the rubric was their awareness of the features

of a composition that would meet the standards for a good grade. It must have

been determinant for their planning since it helped them to organize their

ideas and apply their language knowledge while writing. In our case, most of

the students (85%) identified the development of planning skills in terms of

organization of ideas around a given topic as the second clearest improvement

that resulted from their participation in the rubric design (see Figure

4). Students’ own words picture their point of view:

It did help me

organize on a topic because it gave me ideas what I was going to write about

and it helped me with Spanish grammar… It also helped me in my ability to

write a composition more carefully and it gave me ideas. (Questions 3 & 5,

survey)

In a broader dimension of autonomy, planning would

imply organizing a more complex set of details such as choosing times,

resources, and places most appropriate for learning. However, developing

planning in the restricted sense found in this analysis is surely a valuable

evidence of the development of metacognition that could eventually lead the

students through the path of learning how to learn.

Another self-management strategy (Wenden,

1991), self-monitoring, seems to have been fostered by the use of symbols as

the form chosen to give feedback to the students’ pieces of writing. In their

responses for question 1 of the survey, 85% of the students identified an

increased awareness of grammar errors as a result of this formative assessment

strategy (see Figure 2). Students acknowledged that the

activity actually helped them to better understand their mistakes and correct

them, which is proof of the presence of instances of comparing and making

hypotheses about how the foreign language works in terms of grammar (Edlund, 2003). Some of the students’ responses to the

survey evidence their development of self-monitoring as a result of

self-correcting their errors based on codes provided by the teacher:

It helps you see what you did wrong and not do it

again

Helped me to

understand my own mistakes so I could recognize them later on

By seeing the

errors that I made, it helped me to prevent me from making the same mistake. (Questions

1, 3 and 5; survey)

The key aspect in these pieces of evidence to identify

students’ self-monitoring was the fact that they emphasized

understanding, seeing, correcting, fixing and preventing the making of mistakes

as the result of the activity.

Wenden (1991)

marks the difference between monitoring and evaluating, emphasizing that

“in contrast with monitoring,… hen learners evaluate, they consider

the outcome of a particular attempt

to learn or use a strategy; the focus is on the result and the means by which

it was achieved” (p. 28). Some students’ responses that evidence

self-evaluating pointed at different aspects of the FL learning process. When a

student stated, “If I use my notes, it will help me to understand better

and study,” he evaluated the usefulness of a strategy. Or when another

student stated that the project had been “Helpful in her understanding of the Spanish language and grammer”

[sic], she was referring to one

specific component of her communicative competence. On the other hand, when

this other student wrote, “I think doing all this will improve my English

and Spanish language,” he was reflecting on the usefulness of having been

part of the project in general. Other students’ responses that showed

self-evaluation are

It helped me with my writing completely

Has improved my Spanish skills and knowledge

A good learning

experience, because it really helped me learn how to correct my problems. (Questions

1 and 5, survey)

In the following paragraphs, I will discuss the

appearance of a more political dimension of autonomy found in the analysis:

gaining critical thinking.

Gaining Critical

Thinking

Gaining critical thinking within the framework of this

experience refers to events in which the students make honest judgments about their own language performance in a task

based on previously agreed criteria; they also discuss and/or question

decisions and reach agreements based on arguments as well as make changes

towards a more responsible and successful attitude if needed. Critical thinking

evidences the presence of psychological and political traits of autonomy that

should eventually be transferred to other situations.

The psychological traits involve values such as

responsibility and honesty while the political traits imply learning how to

take a stand and support one’s point of view. In its political dimension

“learner autonomy represents recognition of the rights of learners within

educational systems” (Benson, 1997, p. 29). Consequently, “a

considerably expanded notion of the political… would embrace issues such

as… roles and relationships in the classroom and outside, kinds of

learning tasks, and the content of the language that is learned” (p. 32).

Following, I present evidence of an opportunity for a student to discuss his

grade based on arguments, which reflect his development of critical thinking:

When I returned the

papers to the students, one of them was not happy with his grade. So I discussed

the disagreement with him. It was a student who was very strong, regarding

speaking skills and vocabulary, but had some writing weaknesses…I showed

him that he had had a lot of spelling mistakes and emphasized that I had given

him the opportunity to correct before I graded the final paper. He had refused

to correct his mistakes and now seemed to feel disappointed about the grade. It

was not difficult to convince him; he actually smiled at the fact that I was

right, and told me I could keep the grade like that. (Journal, p. 13)

Besides an opportunity for the students to develop

some critical thinking, this was an example of the usefulness of the rubric for

me: the student could not deny that I was right because the criteria were clear

and he had taken part in their establishment. However, the most significant

evidence of development of autonomy for this kid was his change of attitude for

the rest of the semester; he became more responsible and careful in the

development of the writing tasks. This could thus show that his growth in

self-criticism influenced his gaining ownership.

More evidence for development of critical thinking can

be inferred comparing the number of discrepancies between teacher and

students’ grades during the first and second instances of

self-assessment. The fact that this number decreased significantly in the

second instance proved that students’ abilities to self-evaluate their

work improved with experience and that students must have become more

self-critical as they gained expertise evaluating their work (see Table 2).

The Teacher:

Factors that Determined my Role

Given that this study presents teaching strategies applied

within a conscious effort of the teacher to promote autonomy in his students,

the teacher’s role in the process is important to be discussed.

The main themes that emerged in the data analysis

regarding my role as a teacher in the promotion of learner autonomy were

empowering, fostering critical thinking and guiding.

Empowering was evident in different forms, namely, strengthening

students’ independence by training them to self-correct and self-evaluate

as well as teaching them the use of cognitive strategies such as the use of the

dictionary and memory strategies, and encouraging their participation in

decision taking. My beliefs in regard to assessment as a democratic formative

process in which learners should play a starring role were decisive for the

traits of learner autonomy identified in the analysis to take place. My

teaching methodology might as well have facilitated empowering and thus autonomy:

the analysis of the data showed that I used a learner-centered approach to

teaching characterized by group work, the use of technology, and differentiated

instruction, which promoted the development of social learning strategies,

facilitated students’ independence and added to their technical dimension

of autonomy.

My role in the development of students’ critical thinking was evident in two

main instances: (a) the promotion of discussion among them to select the

criteria for the rubric, and with me to discuss grades based on those criteria;

and (b) the facilitation of students’ self-assessment itself. Part of the

impact of students’ self-assessment could be identified as the appearance

of self-criticism and this was evident in some of them changing negative

attitudes and committing themselves to the writing tasks. Some aspects of my

personality probably facilitated this process. My own self-criticism provided

space for reflection and allowed the benefit of the doubt about me being always

right, which was decisive to acknowledge students’ rights and prevented

me from taking authoritarian decisions. Likewise, my flexibility might have

helped in decreasing students’ anxiety at the time of discussing grades,

making it easier for me to approach them and question their behavior. Both

aspects support Voller’s (1997) statement that

“teachers need to reflect critically not only upon how they act during a

learning event, but also upon their underlying attitudes and beliefs about the

nature of language and the nature of learning” (p. 112).

My role as a guide

and technical support was evidenced during the development of the key

action strategies of the project. At the time of defining evaluation criteria,

I negotiated with the students, on the one hand, and, on the other, either used

my expertise or linked theory and practice in order to make an informed

decision. Likewise, I guided students to self-correct by using symbols and

using the rubric for self-evaluation. Again, both languages had their role in

this process: English was the one used to lead reflections about

meta-linguistic aspects and Spanish the goal in terms of communicative

competence.

Conclusions

Teacher-student partnership assessment proved to be a

valid strategy to promote learner autonomy. The findings showed that three

dimensions of it developed in the students who took part in this study:

ownership of their learning process, metacognition and critical thinking, which

were found to interrelate producing better conditions for learning. Regarding ownership,

the students showed some independence from the teacher and some sense of

responsibility, both of which were evident during in-class activities that

required the students to be involved and committed. This development of

ownership seems to have been positively affected by a movement observed in some

students towards a more self-critical thinking as evidenced by their

recognition of and effort to cope with negative

attitudes. Alternatively, a more responsible and committed attitude surely

helped to prepare the terrain for more independent learning, supported by the

two main action strategies taken in the project. In that sense, the

students’ development of some planning, self-monitoring, and

self-evaluating skills seems to have positively affected their writing

achievement, and showed an increment on their part of both their technical and

psychological dimensions of autonomy.

Critical thinking was equally reflected in the fact

that students’ self-evaluation was more accurate during the second evaluation

event, which could be explained based on students’ better understanding

of evaluation criteria as they gained experience using the rubric. As a result,

the data showed that some participants were developing the ability to support

their self-evaluation by acting as trained co-evaluators. From this

perspective, students’ development of critical thinking seems to have a

direct correlation with the formulation and discussion of clear evaluation

criteria, which preceded the design of the rubric. By the same token, this

finding evidences a movement of the students towards the development of a more

political dimension of autonomy.

This experience of teacher and students becoming

partners in the process of assessing for learning has equally proved that the

teacher’s role is to some extent a dependent factor of learner autonomy

in the school context. The main features that emerged in the analysis proving

such statement were my role as a guide and technical support, which reflected

my moving towards a more learner-centered teaching approach; and my beliefs in

more democratic forms of assessment, which provided space for students’

participation, fostering their critical thinking and empowering them. Using

Benson’s framework, one could say that, in terms of evaluation, learner

autonomy moved towards the student-control pole with the support of the

teacher.

In spite of these positive results, I am aware that

learner autonomy has a multidimensional nature and needs to be analyzed from

different perspectives. My analysis is thus limited by at least two aspects:

(1) that only one dimension of learning was taken into account i.e. evaluation;

and (2) that learning was only observed inside the classroom within a somehow

teacher-centered environment. I therefore present these conclusions with an

awareness of such limitations. This action research project was implemented

upon a sample of convenience and conclusions are subjected to generalization

only to the extent to which the reader identifies similarities in his/her teaching-learning

context.

Implications

Although teacher-student partnership assessment has

been confirmed to be a significant means to promote learner autonomy, a

political dimension needs to be addressed at a more critical level; promoting

student reflection about social issues that affect them could be an objective

in teachers’ planning that would help the latter to achieve such a goal.

Regarding the assessment construct, teachers must keep

updated with the models that support their teaching approach in order for their

assessment criteria to be clear and valid. Likewise, content and performance

standards need to be established among the language teachers of the school in

order for them to be able to design assessment procedures that could more

accurately evaluate students’ level of proficiency.

This study offers valuable insight for language

teachers in high school about the possibilities of democratic assessment

practices to support language learning. By the same token, it provides a view

of the conditions under which their colleagues teach and allow themselves to

compare and find similarities. EFL/ESL teachers will surely identify challenges

in this article similar to the ones they face in their daily practices. This

case is consequently evidence that it is possible to change things for the

better in such contexts.

Finally, I have realized the benefits of carrying out

action research via my better understanding of the situation and my learning

about the topics that framed the project. Furthermore, I became more conscious

of my role and responsibility in the development of my students’ autonomy

at the time that I developed mine.

1. Although Bratcher and Ryan focus on evaluation and

grading for their classifications, I consider that the whole process in this

study actually corresponds to my definition of assessment; consequently, I have

called it Teacher-Student Partnership

Assessment.

2. The Communicative

Competence was the theoretical construct evaluated.

3. One of the

students had Hispanic roots and there were others with immigrant parents. The

school itself had many students who were Hispano immigrants or had Hispanic

roots.

4. Emphasis mine.

5. Evaluation

criteria and symbols were written in English. Teaching took place in both

languages. Compositions were written in Spanish.

References

Altrichter, H., Posch, P., & Someck, B. (1993). Teachers investigate their work:

An introduction to the methods of action research. London: Routledge.

Angulo-Delgado, F. (2002). Enseñar,

aprender y evaluar: tres procesos inseparables. Tercer Encuentro de Enseñanza de las Ciencias, Universidad de

Antioquia. Medellín, Colombia.

Arias, C., Estrada, L., Areiza,

H., & Restrepo, E. (2009). Sistema de

evaluación en Lenguas Extranjeras. Medellín: Reimpresos,

Universidad de Antioquia.

Bachman, L. F., &

Palmer, A. S. (1996). Language testing in practice. New York, NY:

Oxford University Press.

Benson, P. (1997). The philosophy and politics of

learner autonomy. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy

and independence in language learning (pp. 18-34). London: Addison

Wesley Longman.

Benson, P. (2010). Measuring autonomy: Should we put our ability to the

test? In A. Paran & L. Sercu

(Eds.), Testing the untestable in language education

(pp. 77-97). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Benson, P., & Voller, P.

(1997). Introduction: Autonomy and independence in language

learning. In P. Benson & P. Voller

(Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language

learning (pp. 1-12). London: Addison Wesley Longman.

Brown, D. H. (2004). Language assessment: Principles

and classroom practices. New York, NY: Longman.

Brown, J. D., & Hudson, T. (1998). The alternatives in language

assessment. TESOL Quarterly, 32(4),

653-675.

Bratcher, S., & Ryan, L. (2004). Evaluating

children’s writing: A handbook of grading choices for classroom teachers.

Mahwah, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum Associates. Retrieved from University of Pittsburg

NETLIBRARY database (98761), http://www.library.pitt.edu/articles/database_info/netlibrary.html

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative

action research for English language teachers. London: Cambridge

University Press.

Ekbatani, G. (2000). Moving toward learner-directed

assessment. In G. Ekbatani

& H. Pierson (Eds.), Learner-directed

assessment in ESL (pp. 1-11). Mahwah, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum

Associates.

Edlund, J. (2003).

Non-native speakers of English. In I. Clark & B.

Bamberg (Eds.), Concepts in composition:

Theory and practice of the teaching of writing (pp. 363-387). Mahwah, NJ:

Erlbaum. Retrieved from University of Pittsburg NETLIBRARY database (79439), http://www.library.pitt.edu/articles/database_info/netlibrary.html

Ellis, G. (2000). Is it worth it? Convincing teachers

of the value of developing metacognitive awareness in children. In B.

Sinclair, I. McGrath & T. Lamb (Eds.), Learner

autonomy, teacher autonomy: Future directions (pp. 75-88). Edinburg:

Longman.

Genesee, F., & Upshur, J. (1996). Classroom-based

evaluation in second language education. New York, NY: Cambridge

University Press.

Goodrich-Andrade, H., & Boulay,

B. (2003). Role of rubric referenced

self-assessment in learning to write. The

Journal of Educational Research, 97, 21-34.

Hewitt, G. (1995). A portfolio

primer: Teaching, collecting, and assessing student writing. Portsmouth,

NH: Heinemann.

Himmel-Köning, E., Olivares-Zamorano, M.

A., & Zabalza-Noaim, J. (2000). Hacia una

evaluación educativa 2000: aprender para evaluar y evaluar para aprender. Santiago de

Chile: Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Lamb, T. (2010). Assessment of autonomy or assessment for autonomy? Evaluating learner autonomy for

formative purposes. In A. Paran

& L. Sercu (Eds.). Testing the untestable in language education

(pp. 98-119). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Lippman, J. (2003). Assessing writing. In I. Clark

& B. Bamberg (Eds.), Concepts in

composition: Theory and practice in the teaching of writing (pp. 199-220).

Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Retrieved from University of Pittsburg NETLIBRARY database

(79439), http://www.library.pitt.edu/articles/database_info/netlibrary.html

Little, D. (1995). Learning as dialog: The dependence of learner autonomy on teacher

autonomy. System, 23(2), 175-181.

Mansoor, I., & Grant, S. (2002). A writing rubric to

assess ESL student performance [Electronic version]. Adventures in Assessment, 14, 33-38. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 482885).

Mertler, C. A. (2001). Designing scoring rubrics for your

classroom. Practical

Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 7(25). Retrieved from http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=7&n=25

Moskal, B. M.

(2000). Scoring rubrics: What, when and how. Practical Assessment, Research &

Evaluation, 7(3). Retrieved from http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=7&n=3

O’Malley, M., & Chamot,

A. (1990). Learning strategies in second language

acquisition. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

O’Malley, J. M., & Valdez-Pierce, L. V.

(1996). Authentic

assessment for English language learners. Boston: Addison Wesley.

Pring, R. (2004).

Philosophy of educational research

(2nd ed.). London: Continuum.

Selener, D. (1997). Participatory

action research and social change. New York, NY: The Cornell

Participatory Action Research Network.

Shohamy, E. (2001). Democratic assessment as an alternative.

Language Testing, 18 (4), 373-391.

Stevens, D., & Levi, A. (2005). Introduction to

rubrics: An assessment tool to save grading time, convey effective feedback and

promote student learning. Sterling, Virginia: Stylus.

Voller, P. (1997).

Does the teacher have a role in autonomous language learning? In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language

learning (pp. 98-133). New York, NY: Longman.

Wenden, A. (1991).

Learning strategies for

learner autonomy. London: Prentice Hall International.

Williams, J. (2003). Preparing to

teach writing: Research, theory and practice (3rd ed.).

Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Retrieved from University of Pittsburg

NETLIBRARY database (83850), http://www.library.pitt.edu/articles/database_info/netlibrary.html.

About the

Author

Édgar Picón Jácome holds an MA

in TESOL from Greensboro College in Greensboro, USA. He is an assistant

professor at the School of Languages of Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia, and

belongs to the GIAE Research Group. His interests in research include teacher

and learner autonomy, and evaluation.

Appendix A: Symbols for Self-Correction

Appendix B: Sample of Students’ Compositions