New Educational Environments Aimed at Developing Intercultural

Understanding While Reinforcing the Use of English in Experience-Based Learning

Nuevos

entornos educativos destinados a desarrollar la comprensión

intercultural y a reforzar el uso del inglés mediante el aprendizaje

basado en experiencias

Leonard R. Bruguier*

University of South Dakota, USA

Louise

M. Greathouse Amador**

Benemérita

Universidad Autonóma de Puebla, Mexico

*Retired and deceased since March 23, 2009.

This article was received on October 16, 2011, and accepted on April 12,

2012.

New learning environments with communication and

information tools are increasingly accessible with technology playing a crucial

role in expanding and reconceptualizing student learning experiences. This

paper reviews the outcome of an innovative course offered by four universities

in three countries: Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Course objectives

focused on broadening the understanding of indigenous and non-indigenous

peoples primarily in relation to identity as it encouraged students to reflect

on their own identity while improving their English skills in an interactive

and experiential manner and thus enhancing their intercultural competence.

Key words: Communication technologies, experiential learning, identity,

indigenous peoples, intercultural understanding.

Cada vez es

más fácil tener acceso a nuevos entornos de aprendizaje que

utilizan herramientas de comunicación e información en las que la

tecnología desempeña un papel crucial en la expansión y la

reconceptualización de las experiencias de aprendizaje del estudiante.

En este artículo se revisa el resultado de un curso innovador que se

ofreció en cuatro universidades de tres países: Canadá,

Estados Unidos y México. Los objetivos del curso se centraron en ampliar

la comprensión de los pueblos indígenas y no indígenas, en

particular en relación con la identidad. Esto alentó a los

estudiantes a reflexionar sobre su propia identidad, a la vez que mejoraban sus

habilidades del inglés de una manera interactiva y experimental,

logrando así mejorar su competencia intercultural.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje experiencial,

comprensión intercultural, identidad, pueblos indígenas, tecnologías

de la comunicación.

Introduction

Daily interaction with people having different values,

gestures, social mores, and ways of perceiving reality seems to have become

without a doubt the norm rather than the exception in a world where we seem to

be living in each other’s backyards (Finger & Kathoefer, 2005;

Friedman & Berthoin, 2005). In an increasingly more globalized and

consequently more culturally diverse world, finding effective ways to help

students acquire meaningful intercultural competence has become an important

goal.

This paper reports on a project that involved

undergraduate students from four universities in three neighboring countries;

the United States, Canada and Mexico, who used technological resources to

create an intercultural community of mutual learning. With the aid of technology

and telecommunications, the opportunity to create an intercultural classroom

where learning networks were constructed became a reality. The overall aim of

this project was to encourage students to reflect on their own identity,

interactively and experientially, and thus enhance their intercultural

competence, improve their skills in English as a foreign language, and cross

cultural borders, all through the use of computer technology, which enabled

them to communicate actively in a virtual environment. Helping our students

communicate with other students of different nationalities and cultures

required aiding them in developing themselves “as intercultural speakers

or mediators who are able to engage with complexity and multiple identities and

to avoid the stereotyping which accompanies perceiving someone through a single

identity” (Byram, Gribkova & Starkey, 2002, p. 10).

Recent advances in information and communication

technologies, particularly the effective use of virtual classrooms and the

Internet, have given new meaning to geographical boundaries as distance becomes

increasingly irrelevant. This paper demonstrates how a mediated collaborative

educational endeavor using communication technology can help students acquire

experience and skills in intercultural communication, foreign language learning

and computer-mediated communication, thus fulfilling several important

educational objectives. According to Grosse (2002, pp. 22-23) “learning

how to handle the technology and dealing with different cultures can pose the

biggest challenges”. The project described in this article gave our

students the opportunity to experience some of these challenges first-hand

through an approach to ‘using’ experience for learning. The results

and implications of this project will be discussed.

Background

of the Closing the Distance Education Project

In late 2002 the Closing the Distance Education

Partnership Project (CDEPP) was first conceived by a group of university

professors who were interested in providing their students with the opportunity

to learn and work with students of different cultural, ethnic and racial

backgrounds without having to rely on their physical presence in the classroom.

In the summer of 2003 a partnership was formed among four institutions of higher

education: the University of Wisconsin-Stout, USA (UW-S), University of South

Dakota-Vermillion, USA (USD), First Nations University of Regina, Saskatchewan,

Canada (FNU) and the Benemérita Universidad Autonóma de Puebla,

Mexico (BUAP). Representatives of these four universities—in three

neighboring countries with very different historical experiences and cultural

heritages—met together in a virtual class experience over a period of 18

months, communicating via Internet and phone calls. They then came together in

Puebla, Mexico, in the summer of 2003 to sit down and develop a

multi-disciplinary course that would satisfy the general and specific interests

of each.

After considerable discussion of the different

interests involved, the participating professors and authorities from the four

universities named the course: The

Peoples of North America: Identity, Change and Relationships, which

reflected the main themes to be studied in the course. The primary goal of this

cybernetic course was to provide students of diverse cultural backgrounds

opportunities to enhance their learning by bringing the diversity of the larger

world into the classroom. The objective was to use experiential learning

methodology applied in a nontraditional way to create a sense of community

within the virtual classroom, despite the distance and variations in culture

and language among the students. Central to accomplishing this task was the

understanding that increasing intercultural awareness among students

contributes to the overall education of all students, whatever their cultural,

racial or ethnic background. In today’s pluralistic world, which is

becoming closer and smaller through technology, it is believed that those whose

education has prepared them to work effectively and respectfully in a diverse

global community will be more successful.

The general description of this course leaned heavily

upon exploring relationships among both indigenous and non-indigenous peoples

of North America (see Appendix). One variation in the title

and course description on the part of First Nations University by instructor

William Asikinack was: Systems of

Indigenous Identity, Culture and Society, with the following course

description: This course will examine concepts central to Indigenous identity,

including those categorized as cultural, social and psychological. The holism

of Indian perspectives will be demonstrated.

In the UW-S syllabi the following details about the

course were given:

This is an

experimental course and for most of you unlike any other course you have taken.

Perhaps the best skill you can bring to the course is a sense of adventure and

a sincere desire to learn. Because of the experimental nature of the course,

we, your instructors, cannot predict exactly where we will go or where we will

end, except to say that we will most certainly have a profound learning

experience. No one else in North America has been enrolled in a course of this

nature. You are the first.

At the BUAP information was sent to students in

different career areas of social science and the humanities, who, having shown

a good command of the English language, might be interested in participating in

the course. The invitation stated:

Come and take part

in a new, experimental, multicultural course where you will have the

opportunity to interact with students from Canada, and the USA and actively

practice your English. This course aims to foster intercultural understanding

and appreciation of native and non-native cultures through unique experiential

learning experiences available through the “magic” of technology in

a virtual e-learning classroom.

Our interest as educators was to establish a dialogue

among students coming from these three North American countries with 3

different official languages and many differences in their diverse

socio-economic, racial, ethnic, geographic and political backgrounds. By

creating an uncommon experiential learning environment through the use of the

latest technology and telecommunications tools, we hoped to provide our

students a creative, rewarding educational experience that would ultimately

succeed in preparing them to live and work successfully in a global society.

Our hope was that the experiential learning

experiences offered by this course would supplement overall classroom-based

learning experiences and give students the opportunity to cross cultural

borders and put the theories they were learning in class into practice.

Although students participating in the CDEPP were not engaging in an

experiential learning experience in the classic sense (e.g. a study-abroad

experience), they in fact coming face to face with experiential learning every

time they entered the classroom and met with their classmates and teachers from

different cultural, ethnic and racial backgrounds. While learning theory is

important, real-life experience offers students opportunities to encounter the

complexities of intercultural communication, to connect what they learn in

class to what occurs in the real world, and to question their own beliefs and

assumptions when dealing with behavior and practices that may not fit their

pre-existing ideas. According to Cheney (2001, p. 91), “experiential

methods are ideal for intercultural communication precisely because culture is experienced” (emphasis

was given in the original). “Ultimately, the intercultural journey seems

to be one of facing ourselves as we become aware of and responsible for the

meanings we create and through which we then interpret our experiences”

(Seelye, 1996, p. 12).

In this article, we shall first assess the relevant

pedagogical uses of communication technology in the creation of a non-typical

experiential educational experience and review the important role that

experiential learning plays in a long-distance intercultural classroom setting.

Next, we will present the course objectives and describe the way the course was

organized. We shall conclude by discussing the outcomes of the project, hence

exploring the overall implications with respect to learner interaction

throughout its duration.

Literature

Review

Computer

Technology—A Pedagogical Tool

It is increasingly obvious that information and

communication technologies (cellular telephones, iPod Touch, iPads, etc.) have

become an essential part of life—at home, at work, or in almost any

setting—for a great number of people in the world today. The Nielsen

Company, a market research group, affirm in their

Social Media Report (2010) that social networking is the number one activity

online, and it has increased by 43 per cent since 2009. Accordingly, Americans

spend one third of their time online, networking and communicating through

social networking sites (over 906 million hours a month).

It has been found that using technology as a teaching

tool promotes student participation and interaction (Absalom & Marden,

2004; Boles, 1999; Campbell, 2004). Absalom and Marden (2004, p. 421) found

that having their students engage in e-mail exchange “encourages the most

reticent students to participate”. Computer-mediated technology and live

online interaction can open up and create educational spaces that entice

students to communicate in different, creative ways, and to explore and learn

about other cultures. Through computer technology collaborative learning is

enhanced (Eastman & Swift, 2002; Li, 2002) and it has acquired a new

meaning. In addition, “collaborative learning promotes higher achievement

as well as personal and social development” (Li, 2002, p. 504).

Reich and Daccord (2008) point out that the best use

of technology comes when “teachers are doing less of the teaching and

students do more of the learning” (p. xvii). Activities that require

students to work in groups with one another via computer technologies are being

used more and more to encourage peer collaboration. Student-centered activities

with a technological component foster creativity and empower students to take

charge of their own learning. In the e-learning model students not only work

individually, but also engage in collaborative learning for gathering

information, examining issues and resolving problems.

Communication technology has added a new dimension to

intercultural education, offering students and teachers the opportunity to step

out of the classroom and transcend geographical boundaries without need of a

passport or visa. It is clear from the literature reviewed that the influence

of communication technologies on teaching and learning goes beyond the

classroom. E-mail, chat rooms, Facebook, computer conferencing and so on are

tools that can “offer contemporary students and faculty truly

extraordinary potential for re-designing and expanding the learning

environment” (Bazzoni, 2000, p. 101). Computer-mediated communication

provides a framework for teaching and learning from a distance.

The

Importance of Experiential Learning in Acquiring Intercultural Competence

Intercultural competence is essential for good

communication with people from a different culture. In a

broad sense, being interculturally competent means being open to trying to

understand and respect people from other cultures when communicating with them

in any form. All the participants of the CDEPP considered exploration of

the intercultural dimension of people from different cultures as something of

utmost importance since that was the driving force that brought us together to

design and teach The Peoples of North

America: Identity, Change and Relationships.

The intercultural

dimension is concerned with -helping learners to understand how intercultural interaction

takes place, -how social identities are part of all interaction, -how their

perceptions of other people and others people’s perceptions of them

influence the success of communication -how they can find out for themselves

more about the people with whom they are communicating. (Byram et al., 2002, p.

15)

Helping students develop skills for discovery and

interaction, behaviors that constructively express feelings e.g. tolerance,

respect, empathy, compassion, and flexibility, which will ultimately lead them

to understanding the “other” (Seelye, 1996, p. 14), clearly

expresses the fundamental views that the CDEPP were founded upon:

In such work, we

are leading and supporting people to explore new views of reality and to

develop new frames of reference for categorizing and explaining behavior. We

are suggesting that one can adjust to new ways of being and doing and that life

will be richer and deeper for having encountered differences. We call attention

to strategies for encountering change, unfamiliarity, and ambiguity in creative

ways. Our work demonstrates that it is both possible and positive to realize

that what is taken as “common sense” is indeed “cultural

sense”. It becomes possible to see that the consensual reality in which

one lives is only real to the extent that one believes and accepts the power of

that consensus. And we suggest that such realization is partner to the

development of consciousness, that is, the capability to become self-reflective

about habits of heart and mind and the ways these are expressed in daily life.

The importance of introducing students to new

perspectives beyond those of their particular community is fundamental to

successful learning. Experiential learning requires reflection and critical

analysis of experiences in order to make the experiences educational (Mintz

& Hesser, 1996; Silcox, 1993; Welch, 1999). In preparing them for living

and working together in global communities it is important that students are

given the opportunity to search other points of view and ways of thinking. When

dealing with problem-based education it is clear that this is crucial, for it

is impossible to solve a problem without first analyzing and understanding the

nature of it. The initial analysis leads to the development of a hypothesis,

which must be tested on some kind of action. This then requires further

analysis and reflection, as it is in this reflection that learners come to make

sense out of the new information and experiences (Silcox, 1993).

Much of the literature that revolves around

intercultural learning strongly emphasizes problem-posing education. This kind

of learning involves the whole student on both the affective and cognitive

levels because it engages the learner in the learning process by connecting the

subject matter to the student’s life or way of thinking, which is strongly

influenced by his/her cultural, ethnic and racial background. Consequently,

Shor (1993, p. 26) notes that, “Through problem-posing, students learn to

question answers rather than merely to answer questions. In this pedagogy,

students experience education as something they do, not as something done to

them”.

Philosophies of experiential education built upon Jean

Piaget’s model of learning and cognitive development take into account

learning in different contexts. Learning takes place as people test concepts

and theories based on experiences they have lived, and from these experiences

develop new concepts and theories. As denoted by Piaget, there must be a

balance between these two processes. Citron and Kline (2001) place learning

“in the mutual interaction of the process of accommodation of concepts or

schemas to experience in the world and the process of assimilation of events

and experiences from the world into existing concepts and schemas”.

Similarly, organizational theorist Kurt Lewin (1952) argued in the 1940s that

personal and organizational development results from a process in which people

set goals, theorize about prior experience, then test their theories through

new experiences, and finally revise their goals and theories after evaluating

the results of the new experiences.

It is important to remember that experiential

education is embedded in constructivist theories of teaching and collective or

cooperative learning.

Constructivist theory proposes that knowledge is

constructed individually and collectively as people reflect upon their

experiences, thereby converting experience into knowledge (Geary, 1995).

According to this theory, meaning is not intrinsic in experience. Rather,

knowledge is socially constructed as people observe and interpret it (McNamee

& Faulkner, 2001; Searle, 1995). Kolb (1984, p. 41) agrees when he states

that “learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the

transformation of experience”.

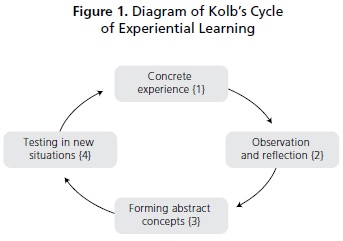

Kolb (1984) illustrated a “simple description of

the learning cycle” based on the above-mentioned work of Kurt Lewin

(1952), which is still relevant today. As can be seen in Figure

1, the cycle begins with a concrete experience, followed by observation and

reflection, which are assimilated into the formation of abstract concepts and

generalizations from which suggestions, ideas or implications for action are

realized. Lastly, these lead to testing the idea or implications of concepts in

new situations, followed by another concrete experience, which starts the cycle

anew.

According to this model of experiential learning, in

order to transform experience into knowledge, learners must begin with their

own concrete experience. They then engage in reflective observation and move to

a stage of abstract conceptualization, during which they begin to comprehend

the experience, which finally brings them to active experimentation of the

concepts. In this model, observation and reflection IS an essential component

of experiential education.

The cycle is implied as a continuing spiral, where the

learning achieved from new knowledge acquired is formulated into a prediction

for the next concrete experience. Within the CDEPP we found that as students

approached a new intercultural experience, the first part of the cycle was a

type of absorption or immersion in the actual “doing” of the

readings, questioning or direct interaction. The reflection stage was stepping

back from the experience and noticing differences, comparing and contrasting

the familiar with the new.

In terms of academic assessment, the most important

stage is conceptualization, where students generalize and interpret events by

asking: What does this mean?

Understanding general principles and theories is central for explaining the

experience. In the last step testing the new theory or principle in new

situations is essential to the learning experience. At this stage, the student

has an opportunity to change behaviors or thinking and apply these changes to a

new set of circumstances. Specific actions can then be made from direct or

inferred reflections that have been refined based on the initial concrete

experience. This process involves intentional preparation and the transfer of

new knowledge to concrete actions (Montrose, 2002).

Experiential learning is being taken into account more

and more by many educational institutions since the relationship between

experience and reflection in the experiential learning process insures

significant long-term learning. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and

Cultural Organization (UNESCO) endorses this fundamental approach to

student-centered learning for a sustainable future claiming that experiential

learning engages students in a concrete experience that involves the learner to

make a critical analysis of the situation and enables them to shape new

knowledge so that it can be used at a later time when a similar situation is

encountered. What makes this an educational endeavor is not so much the

activity in and of itself, but it is the analysis of the activity that is made

through personal reflection, discussion, writing, or projects that assist the

learner to make the transition from experience to integrated meaning and

consequently to understanding (Cox, Calder & Fien, 2010; Montrose, 2002).

According to Montrose (2002), experiential learning

methodology is intended to promote and encourage a solid academic agenda, where

justifiable grades, academic course credit, and concrete experiences can all be

integrated, not only in terms of the curriculum and the syllabus, but in daily

activities as well. This learning model of obtaining educational results from

direct experience can be and is structured, allowing academic credit to be

awarded. The experiential learning that takes place in the CDEPP stems from

pedagogy that actively engages the student in the phenomena that they are

studying. When students develop their own research agenda, engage in critical

thinking and test their interpersonal skills, they directly encounter an

alternative world view, learning through analysis and reflection, including the

consequences of the larger social and ethical implications of this knowledge.

This learning approach engages students in an intentional process of critical

thinking and hands-on problem-solving. It often develops with the smallest

amount of the common institutional structure being presented to the student

before the actual learning experience. Students in an experiential learning

situation do not memorize and parrot back information: They create and produce

their own ideas and work through possible solutions to complex problems. This

integration of concrete action, analysis and reflective thought makes possible

the evaluation of the overall learning experience through intentional,

measurable learning goals and objectives (Montrose, 2002). As Itin (1999, p.

93) points out: Experiential education engages “carefully chosen

experiences supported by reflection, critical analysis, and synthesis”,

which are “structured to require the learner to take initiative, make

decisions, and be accountable for the results”.

The Project

Described in this section are the participants of the

CDEPP project and how the course was set up and carried out.

Participants and

Class Composition

The students and the two professors participating from

UW-S were non-indigenous Caucasians, who primarily came from families that had

immigrated to the USA from a Scandinavian country at least 2 generations before

(the class at UW-S started with 24 students and ended with 18). The

participants of FNU were indigenous and included 6 students. Two of the

students and the teacher were from the Anishinaabe indigenous group, and the

other 4 students were Cree. Of the six students enrolled in the course from

USD, 2 were Dakota (Sioux) and 3 Lakota (Sioux) and one Caucasian,

non-indigenous; the instructor was mestizo, indigenous-American. The students

participating at the BUAP were a mixed group: 7 native Mexicans (mestizo:

Spanish-indigenous), 1 exchange student from California who considered herself

“Chicana” (daughter of Mexican-born parents who moved to the USA,

where she was born), 1 Russian-Ukrainian, and 1 Nicaraguan student. The two

participating professors (authors of this article) at the BUAP were

Cuban-American, and Native American-Lakota, Sioux from the Yankton Sioux

Reservation in South Dakota.

At the end of the course, a total of 40

students—17 men and 23 women—had participated from beginning to

end. The majority of the students were in their 3rd year of undergraduate

studies and there was one Master’s level student. The youngest student

was 20 and the oldest 47. The majority of the students were in their

mid-twenties. Four men and 2 women professors participated in the course along

with 1 special guest speaker, Joseph Marshall III, a Lakota scholar and writer from

Rosebud Sioux Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

Class Procedures

The class was held every Tuesday morning from 9 A.M.

to 12:00 P.M. (in Canada an hour earlier) for 13 weeks and was structured in

the following manner:

• Segment

one - Live television lecture led by instructor(s) at one of the universities:

30 minutes.

• Ten

minute break.

• Segment

two - In-class discussion at each site with video and audio turned off: 30

minutes.

• Segment

three - Interactive live television session with all students and professors

participating for 45 minutes.

• Five

minute break.

• Segment

four - online chat/email exchange for 30 minutes, arranged in six groups

consisting of students from UW-S and students from USD, FNU, and BUAP.

Total: 180 minutes.

All class sessions were taught in English with all the

professors participating in the course. Facilitation alternated among the

participating professors (see the course outline at the end of this work with

the list of topics presented in this course) in each of the universities.

Joseph Marshall III, a visiting professor at the University of South Dakota

during the semester in which the course was given, gave the opening class. His

presentation was important in several aspects. Conceivably, however, his most

valuable contribution to the course was the precedent he set for all the

classes to follow, which was one of total respect, collaboration, and wonder,

which invited us all to join in and explore this new unfamiliar territory.

Marshall, a very gifted story-teller, used his talents as such in giving this

first class. At the end of his presentation, imparted with calmness and

clarity, he answered questions. He was very willing to clarify words and

concepts not understood by the Spanish-speaking participants and he expanded on

many of these to help the non-indigenous students, especially those from UW-S,

who, not wanting to offend their indigenous class- mates at this first

encounter, were unsure of the appropriate terms to use. An important discussion

opened on this first day of class, which revolved around the best way to refer

to indigenous people of Canada and the USA and from this discussion many

misconceptions were aired, reviewed and changed.

The different ideas concerning appropriate vocabulary

reflected the cultural differences and stereotypes that students possessed.

Examples of these came up often throughout the course. Such pre-assumptions

were discussed repeatedly, appearing as important themes in long threads of

comments made in e-mail interactions. While the Spanish-speaking students had a

good grasp of the English language and were able to receive clarification when

needed, the class as a whole seemed to be constantly immersed in an ongoing

negotiation of meanings commonly encountered in intercultural situations. And

although English was the language of the class, many words and meanings in

Spanish and of the 4 indigenous languages spoken by the students in the class were also brought into the virtual classroom, into

e-mails and chat session interactions. This opened windows of opportunity for

participants to explore and understand each other more fully.

Course Evaluation

Students’ overall grade for the semester was

based on the aggregate of three portfolios and was determined by the professor

in charge of their class in their home university. Basic rules and requirements

for all students participating in this course were the following:

Students were required to keep a weekly process

journal that included thoughtful and critical reactions to the following parts

of the course:

• readings

• live television lecture

• in-class discussion at Stout

• interactive live television session involving all four

universities and three countries

• online e-mail exchanges and chats

Three times during the semester students were required

to turn in a formal portfolio in which they organized the ideas and

observations from their weekly process journal into a cohesive narrative

showing what they were learning and how their understanding changed. Students

were expected to include in these journals quotes from the readings in support

of their ideas. Each of these portfolios received a grade.

• Portfolios 75%

• Classroom

Citizenship & Attendance 25%

Analysis

Qualitative data from approximately 700+ online chats

generated in segment 4 of the class, responses to open-ended questions, and

information from students’ portfolios were all collected and categorized

according to themes. These were reviewed and analyzed using the thematic analysis

technique. Thematic analysis allowed us to identify themes based on three

criteria: recurrence, repetition, and forcefulness (Owen, 1984). Recurrence

refers to the same thread of meaning, in different words, coming up in

different parts of the text being analyzed. Repetition refers to the same word,

phrase, or sentence, representing an idea or concept, occurring in multiple

places. Forcefulness refers to the emphasis given to a particular idea to show

its importance or the intensity of the speaker/writer’s feelings.

Thematic analysis was very helpful in discerning not only themes that emerged

within each of the participant’s data, but also themes that we found

common among all of our students who participated so actively in this course

(Zorn & Ruccio, 1998).

Initially to help them

interact outside the virtual classroom setting with other students and

teachers, students were organized into 6 groups of 6 students each: two

students from the UW-S and one student from each of the other universities.

Teachers were involved with all the groups. After 2 sessions, this format began

to change. Without any teacher intervention, the groups opened up to each

other, creating a “free-for-all” where all students eagerly

participated. From this point on, all e-mails were sent to everyone in the

class and anyone from the class was free to reply to any of the letters and/or

all e-mails.

E-mails were answered in different ways and from

contrasting perspectives e.g. according to the student, her/his cultural

background, language and form of expression. These online discussions were

almost all written informally, consisting of a question being posed or an

answer to a question already posed. Often the great amount of feedback about

comments regarding an email would open to other topics, some related to the

class and some not, but all clearly demonstrating a healthy curiosity about

what others in the group thought about a topic. Some students became messenger

buddies with other students, engaging in online chat sessions, which were usually

carried out in a written form, though there were also verbal exchanges. The

Mexican students especially enjoyed the verbal exchange although they commented

that they inevitably summed up what had been said in writing.

The following is an excerpt of a chain of e-mail

exchanges demonstrating how they were conducted, the type of themes that were

discussed, how these were started, and how they opened to other related topics

dealing with students’ interests and concerns. Students’ names have

been changed to protect their identity. Their enthusiasm and interest in

sharing their thoughts on the different class themes can be traced in the

following email exchange that begins with comments about the class, thoughts

about multicultural metaphors and a bit of family background and interrelated

reflections:

Hey ya’ll...

Just like everyone

else, I’d first like to say that this class is taking off quite well.

About the comment from Carl (maybe the wrong spelling, sorry sir): I silently

disagreed with your statement that the United States of America is still a

“melting pot”. I have come to the conclusion that differences in

cultures should be celebrated… I apologize for the generalization, white

people were the ones that wrote the books, and coined the term “melting

pot”. For them, this “melting pot” was a way for the United

States to justify our apparent lack of understanding other cultures. For

example, try to imagine what this shows America as saying: “I don’t

care about my culture, so why should you?” I for one/do/care about my

culture, and I want to learn more about it. Thanks guys ;)

Hey everyone,

My name is Andy

Wilson. I am currently enrolled into the Telecommunications program here at University

of Wisconsin-Stout… The main point I would like to address is how most of

us from UW-S feel we do not have very strong cultural beliefs. Although, this

may not be obvious to us, of course we have all gained some culture from our

past. I think we are more susceptible to look past what we have gained from the

past and look at what we have gained from our own lives and beliefs we feel we

have decided on. For example with me, I feel work ethic has been a quality and

belief that has been engrained in me. This type of quality seems to be part of

most of Wisconsin and the Midwest, since we have been acknowledge for our hard

work. For instance people within the south and some amongst the east coast have

acknowledged Wisconsin for their ideals and hard work. Thanks, Jake

Hey- its Janet and Ginger from Stout. We found today’s discussion

really interesting because there were many points of view expressed.

My name is Janet

and I’m from St. Paul MN. I am Dutch, Welsh, Irish and German. I

don’t have that strong of a sense of my cultural background but I was

introduced to the Mexican culture when I was younger. My best friend/ neighbor

since I was 3 wks old is Mexican and we basically grew

up together and I took part in celebrations and meals. I have visited Durango

Mexico 3 times and stayed for about 3 weeks at a time. I am very interested in

either studying abroad or living in Mexico in the future. Although this

isn’t my heritage, I find it to be a very important part of my life.

My name is Ginger

and I’m from Spring Valley, WI. I am German and a little bit Polish. I

don’t know too much about my cultural background. I am however exposed to

different cultures on a regular basis. I work at a hotel so I have the

opportunity to meet different individuals from all over the world and they are

very willing to discuss their culture. I also work with Mexicans and have a

learned a lot about the Mexican culture and their traditions. Please E-mail us

back and tell us a little about yourselves.

Hello everybody,

This is Ana from

Mexico and I would like to say that this is being a great experience for me. I

find this course pretty interesting. I must confess that I wasn’t aware

of many things that have been discussed during these two sessions. And I hope

to keep learning more about them. I’d like to learn more about identity

and all the factors that influence over the acculturation situation. Ana

Hi to everyone,

this is Tere from Mexico I didn’t come last class so I couldn’t

send you a message, so I just want to say that I’m so glad to be in this

class, to know you and to learn more about the different cultures represented

in this big class. I’m so sorry for the mistakes in my grammar if there

is one; you know that I’m still learning. Thank you. bye

I admire you and

our classmates in Mexico for taking a class being conducted in a language that

is not your first language. I have understood everyone very well. My English

isn’t perfect either and I am a terrible typist so I hope you understand

me, too. Professor at USD

Students’

Reflections on Their Learning Experience

At the end of the course all students were asked to

fill out a questionnaire regarding their learning experience. The majority of

students who completed the questionnaire (n=36) found the course very

interesting (96%), valuable, meaningful and/ or worthwhile (98%), and

motivating and fun (95%). They felt that the email and chat exchanges helped

them to further understand themes discussed in class (98%), they enjoyed doing

the final portfolio project (92%), and they reported they were glad they had

participated in the course (98%). 98% said they felt that their opinions about

the groups represented in the class had changed significantly and in a positive

way. The questionnaire results were supported by comments made in their

journals and portfolio reports, but more substantially they came from responses

made in email exchanges during the last segment of the class period.

Other questions asked referred to what the students

had most enjoyed about the class. Many mentioned having the opportunity to see,

hear, talk to and exchange thoughts, questions and ideas with someone from

another part of America and a background different from their own. They enjoyed

learning about history, culture, current events, and life in general from real

people, not simply from a book, a movie, or a talk show. Our conclusion, based

on many of these comments, is that the project indeed fulfilled our objective

as it encouraged our students to examine more closely their own beliefs,

attitudes, values and feelings. As the course developed they became more keenly

aware of any personal ethnocentric feelings they might have or have had, and

they began to understand how this could be an obstacle or wall blocking their

understanding of others (Gudykunst & Kim, 2003). This type of self-reflection

about their own self-awareness is also reported and discussed in a research

project on email discussions between Taiwanese and American students by Ya-Wen

Teng (2005). As noted in the literature related to effective intercultural

communication teaching, it should include reflection on one’s own culture

(Cheney, 2001) to ensure optimal learning.

According to the majority of students’ comments

about the project, they felt that on the whole, the course allowed them to

study, evaluate, and even re-evaluate, different topics and issues from diverse

points of view and compare them to their own. Students voiced opinions about

their increasing awareness of several ethnocentric attitudes they had had

before the course, and how they were able to analyze them with clarity, coming

to an understanding of their origin and an awareness of the influences that had

sustained them. One student commented:

When I was in

Germany in the summer of 2002 I heard the term “towel-heads” in

German used to describe people of Islamic faith (mainly Taliban) also is to

describe the near two million Turks in southern Germany which differs from the

catholic majority. I don’t know about Canada or Mexico but there are

other countries that have used racial/ethnic denigration. This discussion has made

me think about these kinds of attitudes and examine some of my own…surely

not all Arabs are terrorists and not all white males in the Milwaukee area are

Jeffrey Dahmers.

Conclusions

The interaction during class time was very lively and

interesting, and the participants were very motivated. The voices of the

indigenous students were active during the televised parts of class, though in

the part of the class that pertained to exchanging written commentaries via

email they were not as active. Students at the University of South Dakota

seemed slow to engage in the written exchange of comments, but by mid-semester

they became quite active. Students in Canada participated

a bit less, although the professor participated on a more regular basis,

speaking about the situation of the First Nation people of Canada. We suspect

that the lack of Internet involvement could have been attributed to

insufficient computer and Internet connections and to students’ hesitancy

to add to the flow of thoughts and ideas.

Professors participated freely in the class and in

email interaction, sharing information, clarifying doubts that arose and

answering specific questions. There was always plenty of space available for

students to carry on the interactions.

At first, the students at the BUAP were a bit timid

during the televised sessions and in their written messages. These students

felt somewhat apprehensive and shy about speaking and writing in

English—a foreign language for most of them. However, after the first

couple of sessions they felt more comfortable and engaged in making more

comments during the televised part of class as well as in emails.

The students at UW-S were for the most part the quietest of all the

students during the televised part of the class; even when directly asked,

their participation was low-key. This reaction did not change during the

course; however, these students were very active in their Internet

communications. They asked questions, expressed

thoughts, revised thoughts and opened up much more than we saw in the televised

sessions of the class.

When the UW-S students were questioned about their

silence in the classroom sessions they answered via email. Here are a few

examples of what they said:

Hi Everybody! I

just wanted to comment on why Wisconsin, Stout doesn’t comment. For me

this is all a learning experience, we are able to learn so much about other

cultures. The real stories. I feel bad that we

don’t learn more of other cultures throughout high school, before

college. I feel that is part of the ignorance of the US; it’s all about

us. It seems a lot of the things we learned are only the “good”

stories the whites did for the Native Americans. Hopefully through this class

we will be able to take our learning farther and one day we can all be a

“community”. Not so unknowing of each other’s countries. And

hopefully this will encourage better political interactions, one not so

dominant. I love learning about the other cultures; it has definitely broadened

my horizons!

Another student wrote:

I couldn’t

have said it better myself, actually! Most of the time I’m just absorbing

all the new information that is coming in! This class has been great;

I’ve learned so many things. Specifically, I’m very proud that I

was part of this class; I look forward to sharing my knowledge with others.

From Canada one of the students added to the

discussion saying:

I am glad that we

all can learn from this class. We need to be aware of different cultures in

order to understand. There needs to be a willingness to learn by the other

culture before this can happen.

When the course was over, students and teachers alike

participated in the overall evaluation. Many positive comments were made. The

only negative comments were in reference to the occasional technological

difficulties, such as seeing each other but having no sound or vice versa, that

occurred during the course. There was also the occasional difficulty in

receiving the readings with time enough to read, especially for the Mexicans

who needed more time to go through the material. As far as the course itself,

the overall evaluation was that it was a very successful and challenging course

that really propelled everyone to explore both within and beyond themselves,

their communities and their countries. It stimulated thought, challenged old

viewpoints and introduced new and different ways of looking at many issues.

Student participation in the class, both orally in the televised segments and

in the emails was most successful. Students grasped the conceptual framework of

the syllabus and commented succinctly on the subject matter. They found the

class not only informative, but fulfilling and enriching as well.

In closing, we have chosen one comment of the many

that students sent via email or wrote in a final paper relaying their overall

feelings about the course:

From a Mexican student:

Now that the course finished our task was to write

about all the things that we have been through in this course. First of all I

would like to start with some of the topics that were discussed in the course.

The theme that I was interested the most was “identity”. I remember

Mr. Marshall told us that being aware of whom and what we are is very

important. I totally agree with

this idea. I think that in order to be able to identify ourselves from others

first we need to know ourselves better, we need to know where do we come from

and finally taking into account all the process that we have passed through we

will be able to know what we have become. Although some of us may not like the

final product of that process, we still have the opportunity to make some

adjustments in order to improve ourselves. I learned the things that I expected

to learn and much more which makes me more than happy. I realized that I still

need to learn more about my country and others, it was very interesting to know

what other people think about my culture and it was more interesting to tell

them the way we see and think about them. I think that all of us learnt many

things about each other and everybody was interested on knowing more. In

general the course was amazing; I found it more than interesting, helpful and

fun. Also my English has improved A LOT!! I really enjoyed each session and I

would totally recommend other people to take it, during each session I could

learn something new and now I am able to use it in my daily life. This course

fulfilled my expectations and went beyond. Thanks to all in the course for

helping me to open my eyes and for making of this course an unforgettable

experience.

References

Absalom, M., & Marden, M. P. (2004). Email communication and language learning at

university—An Australian case study. Computer

Assisted Language Learning, 17(3-4), 403-440.

Bazzoni, J. O. (2000). The electronic internship advisor: The case for

asynchronous communication. Business

Communication Quarterly, 63(1), 101-110.

Boles, W. (1999). Classroom assessment for improved learning: A case study in using

e-mail and involving students in preparing assignments. Higher Education Research and Development, 18(1), 145-159.

Campbell, N. (2004). Online discussion: A tool for classroom

integration? New Zealand Journal of

Communication, 5(2), 3-24.

Byram, M., Gribkova, B., & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing

the intercultural dimension in language teaching: A practical introduction for

teachers. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Citron, J. L., & Kline, R. (2001). From experience to experiential

education. International Educator,

10(4), 18-26.

Cheney, R. S. (2001). Intercultural business

communication, international students, and experiential learning. Business Communication Quarterly, 64(4),

90-104.

Cox, B., Calder, M., & Fien, J. (2010). Experiential learning. In United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

[UNESCO] (Eds.). Teaching and

learning for a sustainable future. A multimedia teacher

education programme. UNESCO. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/education/tlsf/mods/theme_d/mod20.html

Eastman, J. K., & Swift, C. O. (2002). Enhancing collaborative learning:

Discussion boards and chat rooms as project communication tools. Business Communication Quarterly, 65(3),

29-41.

Finger, A., & Kathoefer, G. (2005). The quest for intercultural competence:

Interdisciplinary collaboration and curricular change in business German. The Journal of Language for International

Business, 16(2), 78-89.

Friedman, V. J., & Berthoin, A. A. (2005). Negotiating reality: Theory of

action approach to intercultural competence. Management

Learning, 36(1),

69-86.

Geary, D. C. (1995). Reflections of evolution and culture in children’s cognition:

Implications for mathematical development and instruction. American Psychologist, 50(1), 24-37.

Grosse, C. U. (2002). Managing communication within

virtual intercultural teams. Business

Communication Quarterly, 65(4), 22-38.

Gudykunst, W. B., & Kim, Y. Y. (2003). Communicating

with strangers: An approach to intercultural communication (4th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Itin, C. M. (1999). Reasserting the philosophy of experiential education

as a vehicle for change in the 21st century. The Journal of Experiential Education, 22(2), 91-98.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning

as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall.

Lewin, K. (1952). Group decisions and social change.

In T. M. Neweomb & E. L. Hartley (Eds.), Readings in social psychology (pp.

39-44). New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Li, Q. (2002). Exploration of collaborative learning

and communication in an educational environment using computer-mediated

communication. Journal of Research

on Technology in Education, 34(4), 503-516.

McNamee, S. J., & Faulkner, G. L. (2001). The international exchange

experience and the social construction of meaning. Journal of Studies in International Education, 5(1), 64-78.

Mintz, S., & Hesser, G. (1996). Principles of good practice in

service learning. In B. Jacoby and Associates. (Eds.), Service-Learning in

higher education (pp. 26-52). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Montrose, L. (2002). International study and experiential learning: The

academic context. FRONTIERS: The

Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad. Retrieved from http://www.frontiersjournal.com/issues/vol8/vol8-08_montrose.htm

The Nielsen Company/Nielsenwire. (2010). What

Americans do online: Social media and games dominate the activity.

Retrieved from http://blog.nielsen.com/nielsenwire/online_mobile/what-americans-do-online-social-media-and-games-dominate-activity/

Owen, E. F. (1984). Interpretive themes in relational

communication. Quarterly Journal

of Speech, 70(3), 274-287.

Reich, J., & Daccord, T. (2008). Best ideas for

teaching with technology: A practical guide for teachers, by teachers.

Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc.

Searle, J. R. (1995). The construction of social reality. New York, NY: Free

Press.

Seelye, N. H. (1996). Experiential activities for intercultural learning.

Yarmouth, ME: Nicholas Brealey Publishing Co.

Silcox, H. (1993). A how to guide

to reflection: Adding cognitive learning to community service programs. Philadelphia:

Brighton Press.

Shor, I. (1993). Education is politics: Paulo Freire’s critical

pedagogy. In P. McLaren & P. Leonard (Eds.), Paulo Freire: A critical encounter (pp. 25-35). New York, NY:

Routledge.

Ya-Weng Teng, L. (2005). A cross-cultural communication

experience at a higher education institution in Taiwan. Journal of Intercultural

Communication, 10. Retrieved from http://www.immi.se/intercultural/

Zorn, T., & Ruccio, S. (1998). The use of communication to

motivate college sales teams. Journal

of Business Communication, 35(4), 486-499.

Welch, M. (1999). The ABCs of reflection: A template

for students and instructors to implement written reflection in service

learning. NSEE Quarterly, 25(2),

23-25.

About the

Authors

Leonard R.

“Horse” Bruguier was born on the

Yankton Sioux Reservation in Wagner, South Dakota. He held a PhD in history and

served as director of the Institute of American Indian Studies and Oral History

Center for 15 years and was History Department professor at the University of

South Dakota when he retired to live in Mexico in 2004.

Louise M. Greathouse Amador is a professor and researcher at the Instituto de

Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades Alfonso Veléz Pliego at the

Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (Mexico) in the

graduate program in Langauge Sciences. She holds a PhD in Sociology, BA and

Masters in Applied Linguistics. Her research focuses on educational

alternatives for constructing a culture of peace based on “Humane

Education”.

Appendix: Description of the Course The Peoples of

North America: Identity, Change and Relationships

The main course objectives and outline for the course

that were agreed upon and later implemented by the four participating

universities in the summer 2003 meeting were:

Main Course

Objectives:

1. Broaden the

understanding and perspective of indigenous and non-indigenous peoples of North

America in areas of identity, change and relationships;

2. Prepare

students for service within their respective communities;

3. Prepare

students for the global society and workplace.

Course Outline:

I. Introduction

a. Course

overview;

b. Instructor

introduction.

II. Identity

Objectives:

a. Provide

students a means and method of understanding the relationship between heritage

and identity;

b. Introduce

students to the debates and discussions of concepts such as race, ethnicity and

multi-culturalism.

III. Ethnocentrism,

Stereotyping and Norming.

Objective:

Pose the question of how we think others perceive us,

and how we perceive others.

IV. Contemporary

Realities—Globalism/Colonialism

Objectives:

a. Expose

students to and discuss the various opportunities and threats presented by

globalization;

b. Ask

students to identify the forces that have contributed to their understanding of

race and ethnicity.

c. Introduce

students to the widening gap between the rich and poor, both intra-nationally

and internationally.

Content Area 1

-

Provide students a

means and method for understanding the relationships between heritage and

identity, and

-

Introduce students

to the debates and discussions surrounding the concepts of “race, ethnicity,

culture and multiculturalism”.

Content Area 2

-

Pose the question

of how we think others perceive us and how we perceive others.

Content Area 3

-

Expose students to

and discuss the various opportunities and threats presented by globalization.

-

Ask students to

identify the forces that have contributed to their understanding of race and

ethnicity.

-

Introduce students

to the widening gap between the rich and the poor, both intra-nationally and internationally.