The Role of Genre-Based Activities in the Writing of Argumentative

Essays in EFL

El papel

de actividades basadas en géneros en la escritura de ensayos

argumentativos en inglés como lengua extranjera

Pedro

Antonio Chala Bejarano*

Pontificia

Universidad Javeriana, Colombia

Claudia

Marcela Chapetón**

Universidad

Pedagógica Nacional, Colombia

This article was received on February 1, 2013, and

accepted on July 27, 2013.

This article presents the findings of an action

research project conducted with a group of pre-service teachers of a program in

modern languages at a Colombian university. The study intended to go beyond an

emphasis on linguistic and textual features in English as a

foreign language argumentative essays by using a set of genre-based

activities and the understanding of writing as a situated social practice. Data

were gathered through questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, class

recordings, and students’ artifacts. The results showed that genre-based

activities supported the participants throughout the experience and boosted

their confidence, resulting in a positive attitude towards essay writing. The

study highlights the importance of dialogic interaction to provide scaffolding

opportunities, of understanding writing as a process, and of the use of samples

and explicit instruction to facilitate writing.

Key words: Argumentative

essay writing, genre-based teaching, scaffolding, situated social practice.

Este

artículo presenta los hallazgos de una

investigación-acción realizada con un grupo de estudiantes de la licenciatura

en Lenguas Modernas de una universidad colombiana. El estudio buscaba ir

más allá del énfasis en las características

lingüísticas y textuales en la escritura de ensayos argumentativos

en inglés como lengua extranjera, mediante un conjunto de actividades

basadas en géneros y comprendiendo la escritura como una práctica

social situada. Los datos se obtuvieron a través de cuestionarios,

entrevistas semiestructuradas, grabaciones de clase y

artefactos de los estudiantes. Los resultados muestran que las actividades

basadas en la enseñanza de géneros proporcionan apoyo a los

participantes durante la experiencia investigativa y aumentan su confianza y

actitud positiva hacia la escritura de ensayos. El estudio resalta la

importancia de la interacción dialógica para ofrecer

oportunidades de andamiaje, la escritura como proceso y el uso de muestras e

instrucción explícita para facilitar la escritura.

Palabras clave: andamiaje,

enseñanza basada en géneros, escritura de ensayos argumentativos,

práctica social situada.

Introduction

Today, due to its importance as an international

language, the presence of English in educational settings is paramount.

Institutions, then, encourage the development of students’ abilities to

communicate in the foreign language and writing is, of course, a skill to be

included. However, writing is not always approached from a communicative

perspective, and linguistic and textual emphases are fostered instead. On the

other hand, essay production is widely used (Lillis, 2001) but not very often

seen from a social and situated perspective that makes writing a meaningful and

purposeful activity.

This research project emerged from a necessity to

foster transformation in writing practices, which privileged a product over a

process view of writing and allowed little opportunity for students to express

their voices in a meaningful way. The study attempted to approach EFL

argumentative essay writing from a perspective that influenced literacy

practices worldwide: writing as a situated social practice. To complement this

understanding of writing, a genre-based perspective was adopted as the

pedagogical approach to frame the experience. Although these two perspectives

have been central in research, they have not been openly used together to

approach student writing of argumentative essays. The main objective of this

study was to explore and describe the role that a set of genre-based activities

may have on argumentative essay writing with a group of high intermediate

students of English in the Bachelor of Arts in Modern Languages program at a

private university in Bogotá.

The research question guiding this study was: What is

the role of a set of genre-based activities in the creation of argumentative

essays by high intermediate students of English in the BEd

in Modern Languages program when writing is understood as a situated social

practice?

Literature

Review

Keeping in mind the importance of dialogic interaction and scaffolding

(Bruner & Sherwood, 1975; Vygotsky, 1978), we

feel this study conceives students as subjects of their learning and fosters

their individualities and deliberation

processes (Grundy, 1987). Language is understood here as a situated action that

embeds and manifests different forms of knowledge, beliefs, and ways to refer

to the world. The three main constructs that support this study are Genre-Based

Writing, Argumentative Essay Writing, and Writing as a Situated Social

Practice. These are explained in the following sections.1

Genre-Based Writing

This study considers Hyland’s (2004) view that

“genre-based teaching is concerned with what learners do when they

write” (p. 5), which emphasises the importance

of the situated context where writing occurs and further considers this

practice as communication. Two characteristics of genre-based writing activities

are considered: First is Hyland’s (2004) concept of modelling, which aids students to

explore the genre and understand features such as rhetorical structures or

frames (Hyland, 2004) and formulaic

sequences (Morrison, 2010). Second is Bastian’s (2010) explicit teaching of genre, which

promotes awareness of genre conventions as well as reflection on its purposes

and uses. Genre is considered as situated

social action; this perspective accounts for a social dimension of

communication and acknowledges the relationship between the genres and their

social context, students’ voice-as-experience

(Lillis, 2001), and the collaboration and scaffolding (Bruner & Sherwood,

1975) provided by skilled writers to struggling peers (Lin, Monroe, & Troia, 2007).

Two research studies on genre-based teaching can be

mentioned. Morrison (2010) designed and implemented a short distance writing

course at an organisation in Tokyo. It was an effort

to improve the students’ writing skills by preparing them for the

International English Language Testing System (IELTS) exam through the use of a

genre-based pedagogy to second language writing. The study provides interesting

information regarding multiple drafting and feedback to provide scaffolding and

to foster a transformative writing process. Finally, Chaisiri

(2010) conducted a study in different universities in Thailand. It consisted of

two phases: The first one investigated how teachers perceived their approaches

to teaching writing and the second phase was an action research study,

intending to find the role of genre-based activities in a writing classroom.

This study provides significant theoretical and practical insights on how to

use a genre-based perspective in an action research study.

Argumentative Essay

Writing

Argumentative essay writing is understood here as a

dynamic literacy practice where the author establishes a dialogic relationship

with an audience defending a point of view and looking to convince, get an

adhesion, or persuade (Álvarez, 2001). As

dialogue between interlocutors (Ramírez, 2007)

emerges through argumentative essay writing, this practice goes beyond a

linguistic perspective to become social action. In this dialogue, the writer

communicates with a reader and shapes his/her discourse according to the

relationship that is established between them: power, contact, and emotion (Goatly, 2000).

Three articles illustrate previous research connected

to argumentative essay writing. Nanwani (2009) analysed the linguistic challenges lived by a group of

students at a private university in Bogotá in the development of

academic literacy. In his study, the author provides insights to reflect on the

challenges of writing academic texts. He also hints at a transformative view of

this practice and suggests that students’ backgrounds should be

considered. Zúñiga and Macías (2006) conducted a study to help advanced

English students of the undergraduate Foreign Language Teaching Program at

Universidad Surcolombiana to refine their academic

writing skills. This study draws attention to the importance of instruction,

peer feedback, inclusion of sample papers, and the possibility to publish

students’ texts to foster their motivation. Finally, Street (2003)

explored where writing attitudes originate and how they influence practice.

Participants of this study were undergraduate students in a teacher education programme in Texas. The study sheds light on the positive

and negative experiences in the process of writing, and it highlights the

importance of the writing process and the product in the development of

students’ attitudes, as well as the consideration of their identity.

Writing as a

Situated Social Practice

Writing practices are situated and social as they

occur within specific contexts, at specific moments, and ser

ve the specific needs of communication, learning, and

expression (Ramírez, 2007). In this sense,

writing and the writer participate in discourses (Gee, 2008), ideologies, and

institutional practices, as well as establish a dialogic connection with the

world and the powers that surround them. At the same time, writers not only

imbue their texts with their inherent characteristics such as gender or race,

but also include their voice as

experience: their beliefs, experiences, and feelings that have been built

and moulded through social contact (Lillis, 2001). It

is then understood that writing implies more than the development of a

technical skill. According to Baynham (1995), writing

can be approached via considering the subjectivity of the writer, the writing

process, the purpose and audience, the text as a product, the power of the

genre, and the source or legitimacy of that power.

Although little research has been conducted which

considers writing as a situated social practice, two research studies related

to this construct are worth mentioning here. One was conducted by Correa (2010)

in a general studies programme in a public school in

Massachusetts. It examined the challenges that a mature ESL student and her

teachers faced with regard to the construction of literacy and voice in

writing. This study is important as Correa seems to call for a need to go

beyond a technical view of writing and to stop considering that writing is

“applicable across context, purpose, and audience” (p. 92). On the

other hand, Ariza (2005) conducted action research

with a group of ninth-graders in a public school in Bogotá. She

investigated how teachers of English can guide their students to develop their

written communicative competence based on White and Arndt’s (1991)

process-oriented approach to writing. Even though Ariza’s

study does not explicitly take writing as a situated social practice, it does

show the implementation of a project where writing was approached as a process,

not as a product.

Research Design

This qualitative action research study looked to

gather holistic insights by analysing what happened

in the classroom setting (Johnson & Christensen, 2004). Action research was

valuable to reflect on the pedagogical practice and find insights that contributed

to its improvement (Sagor, 2000; Sandin,

2003). The action-research process followed in the study was composed of four

stages, as proposed by Sagor (2005). However, keeping

in mind Burns’ (2003) claim for flexibility in action research, the stages

were dynamic, allowing for changes within our own interpretation of the

research process.

The stages were developed in each cycle of the

pedagogical intervention that was designed. The first stage was clarifying vision and targets. Careful

thinking about the classes, the activities, and the outcomes of teaching and

learning were important to come up with insights to approach writing in a

different way. Research questions associated with the main goal of the study

were raised here. In the second stage, articulating

theory, an informed rationale was built to back up pedagogical

intervention. Important outcomes of this phase were an instructional design to

be implemented and a data collection plan in order to gather insights related

to the research question. The third stage was implementing action and collecting data. Following Sagor (2005), this was the moment in which the

instructional design was put into practice and data were collected to get

insights about the pedagogical intervention. The final stage was reflecting and planning informed action.

Data collected in each cycle of the instructional design were used in order to

reflect upon the implementation of the activities and to plan further action

for the subsequent cycle.

Context and

Participants of the Study

This study was conducted at Pontificia

Universidad Javeriana, in Bogotá, specifically

in the BEd in the Teaching of Modern Languages programme. The participants (aged 17 to 23) included two

male and thirteen female students. They were enrolled in the high intermediate

level, a course taken in sixth semester. At the time this study was conducted,

the course was divided into two modules: International

Relations and Current Issues.

This study was conducted in the latter, dealing with topics like technology,

global and local culture, education, and work. Both the institution and the

students were informed about the study and signed consent forms accepting

participation in it.

Data

Collection Instruments

Four data collection instruments were used. First, the

classes were recorded for sixteen weeks; recordings were important to collect

the teacher’s and students’ actual words in their interactions

throughout the development of the activities. Second, there were two

questionnaires. One was applied at the beginning of the semester to build a

profile of the participants and collect their beliefs and ideas about writing

(see Appendix A); the other was used at the end of the

process to gather the students’ opinions about the experience of essay

writing throughout the study (see Appendix B). Third, there

were artifacts that included the evaluation of each cycle and the argumentative

essays written by the participants. This represented important evidence of the

role that genre-based activities played when students approached writing from a

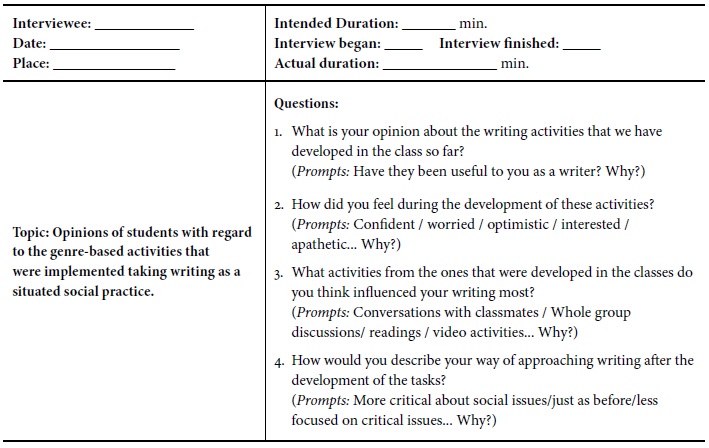

situated social perspective. Finally, three semi-structured interviews were

conducted, one at the end of each cycle (see one sample in Appendix C). They were useful in order to gather students’

reactions, thoughts, and ways they approached writing in the study.

Pedagogical

Procedure

A central element of the action research process was

the creation and implementation of an instructional design which integrated the

three constructs of the study. It emerged after a process of deliberation

(Grundy, 1987) upon the way in which writing was being approached in the

classes.

During the implementation of the instructional design,2 a number of activities

were developed using a genre-based perspective to teaching writing (Bastian, 2010;

Hyland, 2004) and considering writing as a situated social practice (Baynham, 1995; Gee, 2008; Lillis, 2001).

The instructional design was planned following the

sequence of writing topics in the course programme

and consisted of three cycles. Each cycle corresponded to a term during the

semester and dealt with a specific type of essay: Opinion, For

and Against, and Problem-Solutions. In order to account for a genre-based

perspective to teaching writing, a six-step writing cycle was used based on Widodo’s (2006) proposal of a genre-based lesson

plan.

The first step of the writing cycle was exploring the genre. Students analysed sample essays in small groups and as a whole class

with the guidance of the teacher. It was done in the light of theory and

students’ previous knowledge. In the second step, building knowledge of the field, students chose a topic and an audience

and investigated to gather insights that they could draw upon when writing.

Then, groups of peers shared their ideas to get preliminary feedback. In the

third step, text construction or drafting, students actually engaged in

the act of writing in and outside the class. The fourth step was revising and submitting a final draft;

students self-evaluated their first draft, trying to go beyond the linguistic

and textual features. Peer and teacher feedback was also provided through

comments and prompting questions not only about formal aspects but also about

the ideas themselves. Based on feedback and personal reflection, students

constructed a new draft. Assessment and

evaluation by the teacher in the fifth step provided qualitative feedback

about students’ writing performance. The final step was editing and publishing. Students made

final adjustments to their texts and published them on a blog or on Facebook

thus transcending academic purposes to achieve a more realistic and social

purpose as well as a wider audience. Once the whole cycle finished, the

students evaluated the activities developed, the materials, and the

teacher’s guidance. They did this by writing their impressions about

these three aspects on a piece of paper, which they submitted.

In the following section, the findings of this study

are presented. The data gathered through and transcribed from the different

instruments will show the participants’ original voices as they were

actually produced during the EFL class sessions, thus, errors were not

marked/coded nor corrected.

Findings

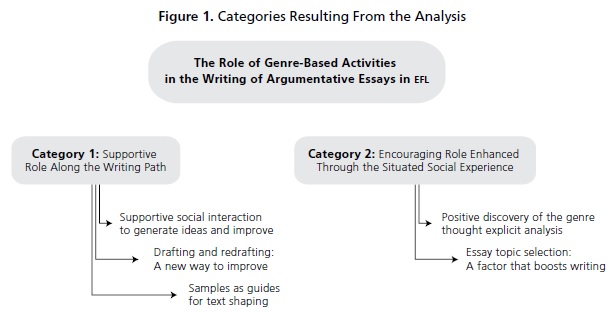

After a process of systematic analysis of the collected

data and having used the grounded approach (Corbin & Strauss, 1990), two

categories emerged: (1) Supportive Role Along the

Writing Path and (2) Encouraging Role Enhanced Through the Situated Social Experience.

These categories describe the main roles that the genre-based activities had in

the students’ construction of argumentative essays during the study.

The data showed that genre-based activities not only

supported the participants throughout the construction of essays but also

boosted their confidence resulting in a positive attitude towards writing

argumentative essays. Support was provided through social interaction among the

participants and between them and the teacher; drafting and redrafting, which

raised awareness of writing as a process; and the sample essays analysed, which helped participants to shape their essays.

Encouragement to write was enhanced through the discovery of generic features

and the possibility to choose the topic of the essays. Figure 1

is a visual representation of the categories and subcategories resulting from

the analysis.

Category 1:

Supportive Role Along the Writing Path

This category refers to the guiding role that the

genre-based activities had in the participants’ essay writing process.

The orientation that was identified in the data relates to the concept of

scaffolding (Bruner & Sherwood, 1975; Vygotsky,

1978) provided through supportive social interaction among participants and by

the samples that were analysed in class; this support

was also enhanced through a process of drafting and redrafting. The data showed

that the activities developed in the study had an important role in guiding

students to diminish the occurrence of linguistic errors in their texts and

acquire the ability to write essays that met the requirements of the genre.

The analysis of the data showed that the support

provided by the genre-based activities came from three sources: (1) Social

interaction with peers and teacher, which helped participants to generate ideas

and improve their texts; (2) drafting and redrafting, regarded by the students

as a new way to improve their essays and their writing skills; and (3) the

essay samples, which were considered by the participants as points of reference

that they could use to shape their own texts. A common pattern that the data

showed in the three sub-categories is related to students’ concern for

mistake identification and correction. Although insights show concern for

aspects that went beyond linguistic and textual aspects, there was still

concern for formal issues.

After presenting a general definition of the category,

we now provide a description of the three sub-categories.

Supportive Social

Interaction to Generate Ideas and Improve

Supportive social interaction refers to the various

ways in which students established dialogic communication with their peers and

teacher and which mediated to enhance text correction and skill improvement.

This activity hints at the supportive nature of genre-based teaching (Hyland,

2004), and the importance of socialisation in the

learning process, as stated by Vygotsky (1978). Data

from the final questionnaire and second interview showed that group work before

writing, during the step of building knowledge

of the field, was an opportunity to get reactions, points of view, and

advice from classmates with regard to the authors’ ideas:

S314: My classmates helped me with some ideas and

sometimes I help them too. (2nd questionnaire)

34. S13: I think it [doing the activities] was useful.

For example, in my particular

35. case, you said: Guys you have to write

another essays, so, I start writing about

36. child labor and then was what you said it was

about cons and

pros, so I told S3

37. …and I said: “Oh my God, what can I do right now?” “Because

I have, so I

38. start.” So, she helped me to think in

the new way that I had to do with my

39. essay, so, I think is useful because you can

compare your ideas with others and do a better essay. (2nd interview)

Sharing thoughts with classmates through dialogic

interaction was shown to be relevant for most of the participants in this

preliminary stage of the writing cycle in order to get ideas and to focus more

on the content that they were going to discuss in their essays. At the same

time, this activity offered participants the possibility to contribute to

aiding their peers in the construction or refinement of their arguments.

On the other hand, peer and teacher interaction and

scaffolding provided in the step of revising

and submitting a final draft were useful for the majority of the students

to identify and correct “mistakes”4

that had been overlooked by themselves and by the teacher. In this respect, one

student states:

S11: Classmates were

a big help because sometimes they show me what the teacher didn’t

realize. (2nd questionnaire)

Interaction was also important for text correction and

improvement, as described by this student:

37. S7: I think it was really important because

sometimes our friends or our

38. classmates realize of some mistakes that the

teacher didn’t realized

39. or sometimes, we express our idea, but it was

wrong and they help

40. us to explain it or sometimes, for example, I

wrote when S1’s

41. essay, she wanted to tell a story and I told her

that it was in that way and

42. she said, Oh, yes, and she explained to you, and

you said, ah, that’s what you wanted to say!

43. That kind of things, I think are important. (2nd

interview)

The above student regards peer work as useful not only

for improving his essays through the correction of mistakes, but also because

it provides the opportunity to become an active agent in assisting others in

their writing process. Also, although there is a concern for mistake

correction, there is an interest for content improvement enhanced through social

interaction. Looking at other students’ essays and having theirs checked

by peers were both useful strategies to get or refine ideas and listen to

points of view that were different from that of the teacher. The social

dimension of writing, evidenced in the interaction that emerged through peer

and teacher supportive action, came also to enhance the development of writing

skills. In other words, social interaction provided scaffolding opportunities:

S3: The most useful

activities were reading other essays and correcting ours. . . . The guidance working

with partners and having the teacher feedback really helped to write better

essay. (Student’s artifact)

In her evaluation of the first cycle, this student

also highlights the relevance of socialisation with

classmates and of the support provided by the teacher in order to render good

results in writing. Writing was assumed as a social action in which guidance

from others was important. The teacher’s support was perceived as useful

to guide the students in writing their essays:

S8: I like the

feedback the teacher gave us for every essay because it makes us to realized

things we should change or take into account for writing an essay. (2nd

questionnaire)

Support provided by the teacher on a dialogic basis was

considered by the participants as relevant and effective for them to correct

their texts and improve their writing skills. Although identifying and

correcting formal mistakes were found to be important contributions of

supportive social interaction, there was also an opportunity for participants

to improve the content of the essays and identify their strengths and

weaknesses in writing, as expressed by this student:

S12: In my case I

agree with [S15], about feedback because in my case I found some problems with grammar,

because I tried to use just let’s say simple grammar structures, so I

realized that I have to use more well structured grammar. (2nd interview)

It is also necessary to mention that not all the

students agreed with the importance of having their essays checked by peers.

Some students did not consider this relevant due to their peers’ lack of

knowledge or inaccuracy to give feedback. This is expressed in the following

piece of data:

S14: I think that

teacher’s feedback is more relevant than peer feedback because, in my

case, I only take into account the teacher’s corrections because the

teacher knows more than a student. (2nd questionnaire)

Drafting and

Redrafting: A New Chance to Improve

The writing and re-writing of essays based on personal

reflection and supportive guidance provided by teacher and peers were found to

be two innovative activities in the writing process; additionally, as the data

from the interviews showed, they were strategies that had not been implemented

in prior courses. The following is an example of this:

22. S11: I think for me the most useful activity was

drafting and re-drafting and

23. also the feedback because what happened normally

is that you just

24. write an essay and you have the feedback at the

end with all

25. the mistakes, so you don’t have actually the

chance to improve

26. and the teacher cannot see the process, the way

you have been

27. improving, they’re just like, Ok, it is

wrong and sorry, 2.0 or

28. 3.0, I don’t know, any grade, but actually when you

start writing

29. and reading again and writing again,

sometimes actually when you

30. receive the feedback, you say, ah! Yes, I have already realized THIS

mistake, because you have the opportunity to read and… proof read, so, I

think that that is what for me, was more useful. (3rd interview)

As this piece of data shows, mistakes were an

important concern for students, and writing used to be viewed mainly as a

product (Grundy, 1987) represented by a grade; however, there is a new interest

in viewing writing as a process, and in this sense, drafting and redrafting

become important because they allow writers to improve during the process.

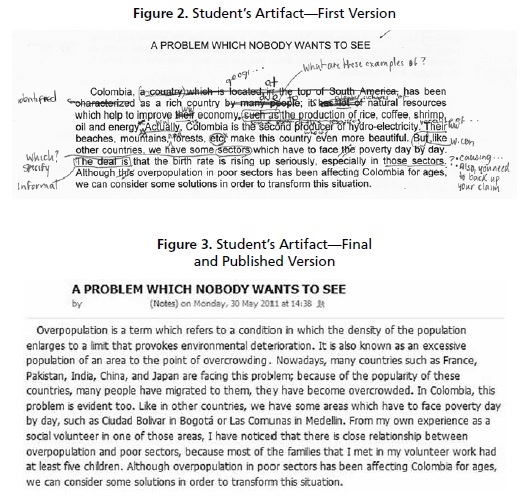

In the participants’ written production it was

possible to find that drafting and redrafting were valuable activities as the

texts showed higher levels of elaboration and correction after scaffolding

activities were done and adjustments were made. Figure 2

and 3 show this of one student.

Certain aspects improved in the second draft with

respect to the first one: To begin with, the topic is narrowed down from

“Colombia” to “Overpopulation in Colombia.” Moreover,

unlike the first draft, the second one presents general information on

overpopulation before focusing on the specific topic.

Furthermore, the ideas in the second version are

supported by the student’s own experience (Lillis, 2001), which is used

to situate the text (Baynham, 1995) in her reality

and gives her the opportunity to write from her own perspective. Changes in

text formality and appropriateness of vocabulary are also more evident.

Drafting and re-drafting were shown; then, as a way to meet generic features

and by elaborating different drafts, the students became aware of how the texts

should be organised, and what other conventions, such

as formulaic expressions, could be used so that their texts came closer to the

genre. The following piece of data, taken from an interview, illustrates this

point:

89. T: And how can you evaluate the final version of

your essay?

90. S10: I think, it’s, you know because of the draft,

you could identify what, I

91. mean, your problems, what were you doing

bad, so, I think at the end

92. when I wrote the final version, I could do it

better and it was, I think it was good. (2nd interview)

Through drafting and redrafting, most of the

participants had the opportunity to identify mistakes and correct them, but

this process in which they engaged also allowed them to reflect on the content

of their essays thus raising their awareness with regard to their writing

skills, enabling them to identify drawbacks and use this information to

improve. This is a remarkable insight as students seemed to go beyond linguistic and textual issues to engage in other dimensions

of writing that were more related to their subjectivity as writers and the

process that they followed when engaged in this literacy practice.

Samples as Guides

for Text Shaping

The essay samples presented and analysed

in class during the step exploring the

genre were considered by the participants as guides or models to shape

their own texts. These samples were important to get students aware of key

genre features and facilitate their personal writing process. Samples were

shown to have a fundamental supporting role as reliable material to consult and

get ideas from in order to adjust their texts in terms of rhetorical structure

and formulaic sequences (Morrison, 2010). This aided students to gain control

of the genre (Chaisiri, 2010), and thus engage in the

act of writing in a more confident way:

S4: When I started

to write my pros and cons essay I didn’t find it difficult because with

the examples of that kind of essays presented in class was very useful to write

it. (Student’s artifact)

This student highlights the role of samples as facilitators in writing. The data also

showed that having a sample guided students in different degrees depending on

their needs as writers. The following interview excerpt shows how samples were

useful in this respect:

39. S2: I think all of them were pretty useful. For example when we looked at the

40. model text, it

41. was really helpful because it’s like a guide for us, and we can

follow that example, not copy it, but just follow that structure. (2nd

Interview)

It was interesting to find that modelling

did not generate blind text imitation. On the contrary, it enhanced the

writers’ ability to discern and make decisions (Grundy, 1987) about what

elements they could integrate in their own texts to meet the genre conventions.

Although students acknowledged the importance of essay samples as reliable

material to guide their writing, they also showed discernment in deciding how

the samples could help them to improve their texts and learn:

S11: I learnt from

the samples, I could take some elements from them for me to use on my essays. (2nd

questionnaire)

31. T: And another thing about the sample essays that

I presented and that you

32. said that they were useful to you. Did you copy

the same

33. structure? What aspects

did you consider from that? From the

34. texts?

35. S5: The organization of the text? [T: Uh-hum.] For example,

if the text

36. presents an organization from the most

important points to the

37. less important, and also some linking words that I

brought, and also I

38. considered the way to introduce the topic sentence

because the

39. way those developed the idea, to parts of this

points to start writing.

40. T: And why did you take those aspects, those little pieces?

41. S5: Because I think that if I do it, I can develop better my essay or I can

make

42. it more organised and

understandable, because I have to respect

43. sometimes the structure and that’s why I

used it.

44. T: Did you adjust, or did you use some of your own ideas to the structure?

45. S5: Yes, sometimes. For example, I have other problems with the conclusion

and I never take some aspects of the models because I think it doesn’t

adjust to my topic but what I do is to write my own ideas and to develop my own

way. (2nd interview)

Samples helped learners to develop awareness of

argumentative essay writing by allowing them to focus on generic features such

as structure and formulaic sequences. On the other hand, samples were also

useful to acknowledge the subjectivity involved in writing (Baynham,

1995), thus helping the students to make decisions about generic features they

could use. Given the dynamic perspective that was embraced in the study,

participants decided which elements to focus on and use in order to consider

the features of the genre and at the same time make the text theirs. It was

also possible for them to draw upon elements from their sociocultural context

to build their texts and support their ideas.

Category 2:

Encouraging Role Enhanced Through the Situated Social Experience

This category refers to the positive role that the

activities developed had on the students throughout the study to build their

confidence in writing. The analysis of data showed that self-reliance and

positive attitudes towards writing were enhanced due to the implementation of

the genre-based activities when writing was considered as a situated social

practice. Confidence was built through explicit analysis of the genre and

understanding the purpose for writing, among other aspects. On the other hand,

the data revealed that the students showed an improvement in attitude towards

the act of writing itself due to two main aspects: (1) The encouraging

discovery of the particular features of the argumentative genre and (2) the

possibility to choose the topics of the essays.

Positive Discovery

of the Genre through Explicit Analysis

Engaged in genre-based activities when writing, the

students were able to build awareness as to how to write opinions, pros and

cons, and problem-solution, essays, paying close attention to genre conventions

and features. This ability relates to the explicit nature of instruction in a

genre-based pedagogy (Hyland, 2004). Explicit analysis of genre features

allowed students to better understand how texts were structured, how the

audience could be approached, and what language could be used to achieve their

purpose. In connection with this, a student expresses:

S7: I can say it

was an excellent experience. At the beginning it was a little bit difficult

because the structure was not clear but thank to the

explanations and power point presentation I really improved in my essays; now I

try to organize it to make it coherent. Now I feel better writing essays. (2nd

questionnaire)

As a personal endeavour,

writing generated different reactions among the students, including fear.

However, due to the use of samples and their analysis, this feeling changed;

participants thus approached writing in a more confident way, even changing the

perspective they used to have about this practice, as shown below:

109. T: S15, has your conception

of writing academic essays changed in certain

110. way?

111. S15: well, I think it has changed a little bit because before I

thought that

112. writing an essay or writing something for English

class was boring

113. and I didn’t feel excited about writing

only for the teacher, but in this

114. course, I realized that writing is a good thing

to do, and I realized

115. that I could express myself by a piece of paper

and I’m excited when I

116. write, next semester I will be excited because I will show the previous

class, so it’s nice for me to show my improvement to the other teacher.

(3rd interview)

Students got engaged in discovering the particularities

of the genre, and this seems to have encouraged them to change their negative

views of writing. Just as they focused on formal features of texts, they also

acknowledged other important aspects like the social dimension and subjectivity

involved in writing. Being able to discover these aspects and the reasons for

writing made the experience more meaningful to the participants and therefore

encouraged them to become more engaged in writing.

A genre-based perspective to writing was important to

explore what students did when they

wrote, and understanding writing as a situated social practice helped to

discover how they felt.

Students’ attitude was an important factor that influenced the way they

undertook writing. Analysis of the genre features allowed the students to

become aware of textual features, which in turn helped them to become more

self-reliant and develop a more positive attitude to undertake writing. Prior

knowledge was elicited and used in order to support the analysis of

genre features, as can be seen in the following exchange that was transcribed

from a class session:

77. T: There are some pros, and there are some cons.

Good. NOW, do you know

78. any other ways to begin

an introduction? Here we began with a general

79. idea.

80. S3: The other way is we begin with the thesis statement and then we develop

81. the essay.

82. T: Ok. What do you think?...We begin with the thesis

statement and then

83. we go to the general point?

84. Class: No.

85. T: It would depend on your eh, style, but usually

we don’t do that. [S15:

86. Yeah]...Good. Another way.

87. S12: Another is called “dramatic entrance,” but I don’t

know.

88. S7: You tell a story about or an experience that you had… [T: Yes.] Related

89. with the topic

90. T: Yeah. Why (bis) would you bring up an

experience that you had (-) and

91. put it there?

92. S3: Because by giving this makes it more real for the reader…it is

not like

93. an idea, but a real situation.

94. T: Excellent, and so it what?

95. T, Class: It catches the attention of the reader. T: Very good. Another possibility.

S12: Define the topic.

T: Define the topic, yes. Good. You can also use an explanatory question at

the beginning

S4: Or we can use a quote from someone else. (Recorded class transcription)

As seen in these data, dialogic interaction with peers

and teacher allowed the students not only to analyse

generic features, but also to establish dialogic communication; in this

dialogue, the students’ subjectivity (Baynham,

1995) and personal background (Lillis, 2001) were very important because they

were able to resort to their knowledge and become active participants in the

social construction of knowledge (Vygotsky, 1978).

Analysis of the texts contributed to building students’ confidence to

write as it was an opportunity to solve doubts and answer questions.

Essay Topic

Selection: A Factor That Boosts Writing

Another important factor that boosted participants’

engagement and positive attitude towards essay writing was the opportunity to

choose the topics. This allowed participants to express their ideas more fully

and relate to the text in a closer way. The students viewed this opportunity as

innovative in their writing experience because, as found in the questionnaires

and interviews, in previous courses it was the teacher who chose for them, and

as a result they felt restricted as to expressing their feelings and

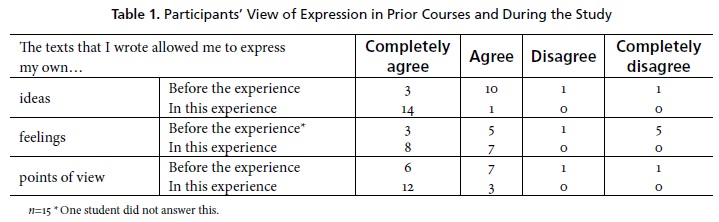

unenthusiastic to write. A comparative quantitative analysis of students’

responses in the first and final questionnaire showed that students felt they

could express their ideas, feelings, and points of view more during this study

than before (see Table 1).

Table 1 shows an important shift

in the participants’ degree of agreement with the question. Although in

the two questionnaires the general opinion remained between “Agree”

and “Completely agree,” there was a higher degree of agreement when

referring to the writing experience they had in the study. The qualitative data

collected through the questionnaires and the interviews showed that the change

in students’ opinion was due to the possibility to choosing the topics of

the essays. Participants felt confident to express their ideas more freely

about topics that they liked, that were interesting to them, and most of all,

which they could choose themselves:

S5: I agree with

the fact that this course let me express my ideas, feelings and points of view

because it was a space where we had this possibility thanks to the chance to

choose our own topics. (2nd questionnaire)

Choosing the topic was revealed to be an opportunity

for self-expression and an encouraging factor for writing. As participants were

able to choose what they would write about, their confidence to write their

essays was improved:

140. T: S12, you said that you felt confident and

comfortable when you

141. wrote. Why was that?

142. S12: Mainly, because of the topic. I think that when we know about

143. something, we can develop it in a well manner, a

well way.

144. T: What do you mean “in a good manner”?

145. S12: That for example we can use some strong arguments or to bring several

146. examples about something that we know well. We

have more elements to enrich the essay. (3rd interview)

Being able to choose the topic helped the students to

gain control of what they said and how they said it. Knowing about the topic

was an important factor that contributed to building up students’ confidence

when writing because it helped them to draw upon ideas and present arguments

that came from their voice-as-experience (Lillis, 2001).

Conclusions

and Pedagogical Implications

The data showed that the genre-based activities had

two main roles in the students’ construction of argumentative essays when

writing was understood as a situated social practice. On the one hand, they

provided support to the participants and on the other,

they fostered encouragement to approach the act of writing.

As to the first role, the data showed that there were

three ways in which the genre-based activities supported the

participants’ undertaking of writing. First, the dialogic interaction

that emerged during the different stages of the writing cycles, among the

students and between them and the teacher, provided scaffolding opportunities

for the students to construct or refine their arguments; given this type of

interaction, the activities allowed the participants to become active subjects

in supporting their peers and enriching their essays at the same time. Second,

the possibility of drafting and redrafting was shown to be an innovative

activity in the study which aided the students to start looking at writing as a

process, not as a product. At the same time, this activity provided them with

the opportunity to meet the generic features of essays and improve their

writing skills. Third, the essay samples analysed in

class were revealed by the data to be facilitators in writing; they were

reliable sources for students to consult and shape their texts with regard to

generic features such as formulaic sequences and text structure. The use of

samples also fostered students’ decision-making in writing by choosing

the elements that helped them meet the genre features and at the same time keep

their texts original and personal; hence, blind imitation of templates was

avoided.

As to the second role, the genre-based activities

generated confidence and positive attitudes towards writing because of two main

factors. First, the discovery of the generic features through explicit analysis

and exploration of the essay samples helped students to become aware of how to

take on the act of writing argumentative essays; this explicit discovery helped

them to improve their perception of writing and undertake this literacy

practice in a more confident way. Second, the possibility of choosing a topic

to write about was a boosting factor for students to engage in writing; the

opportunity to express their points of view with regard to a topic that the

participants themselves chose was an encouraging factor which helped them to

improve their confidence to write as they gained control of what they said and

how they said it.

Carrying out a project in which argumentative writing

is approached as a situated social practice and framed within a genre-based

perspective implies promoting teaching and learning processes that respond to

local needs. Writing essays becomes more meaningful when it is approached from

a situated perspective, and when students can identify with their texts either

because the issues affect them directly as people of the world or because they

feel interested in the topics. By experiencing this, students may be able to

focus on their sociocultural and personal context in a more direct way; they

may be able to name, create and re-create personal experiences which allow

them, as Chapetón (2007) states, to understand

the social nature of the realities that surround them, approach issues from a

critical perspective, and start a meaningful process of transformation of their

reality.

This situated perspective of education calls for a

change in the current paradigms of teacher training and practice within the ELT

community in our country. In the first place, professional development programmes that promote teachers’ reflections on

their own sociocultural contexts should be promoted. As Cárdenas,

González, and Álvarez (2010) claim,

these programmes should encompass and value the

particularities of the communities where teachers come from and must be

coherent with their needs and expectations (own translation, p. 62). By

acknowledging this gap, teachers can start to base their practices on their own

realities and needs instead of importing external knowledge from training programmes that may turn out to be meaningless to their

professional and pedagogical situation.

1 For a comprehensive account of the constructs and

literature review, see Chala and Chapetón

(2012) and Chala (2011).

2 See Chala (2011) for a

detailed description of the instructional design.

3 Codes used: S=Student, T=Teacher.

4 “Mistakes” in this study refer to what

the participants understood as flaws in grammar and vocabulary.

References

Álvarez, T. (2001). Textos expositivo-explicativos y argumentativos

[Argumentative and expository-explanatory

texts]. Barcelona,

ES: Octaedro.

Ariza, A. V.

(2005). The process-writing approach: An alternative to guide the

students’ compositions. PROFILE

Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 6(1), 37-46.

Bastian, H. (2010). The genre effect: Exploring the unfamiliar. Composition Studies, 38(1), 29-51.

Baynham, M. (1995). Literacy practices: Investigating

literacy in social contexts. New York, NY: Longman.

Bruner, J., & Sherwood, V. (1975). Peek-a-boo and the learning of rule

structures. In J. Bruner, A. Jolly, & K. Sylva (Eds.), Play: Its role in development and evolution

(pp. 277-285). Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books.

Burns, A. (2003). Collaborative

action research for English language teachers (3rd ed.).

Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cárdenas, M. L., González,

A., & Álvarez, J. A. (2010). El desarrollo profesional de los

docentes de inglés en ejercicio: algunas consideraciones conceptuales

para Colombia [In Service English Teachers’

Professional Development: Some

conceptual considerations for

Colombia]. Folios, 31, 49-68.

Chaisiri, T. (2010). Implementing a genre pedagogy to the teaching

of writing in a university context in Thailand. Language Education in Asia, 1, 181-199.

Chala, P. A.

(2011). Going beyond

the linguistic and the textual in argumentative essay writing: A critical

approach (Unpublished master’s thesis). Universidad

Pedagógica Nacional, Bogotá.

Chala, P. A., & Chapetón, C. M.

(2012). EFL argumentative essay writing as a situated-social

practice: A review of concepts. Folios,

36, 23-36.

Chapetón, C. M. (2007). Literacy as a

resource to build resiliency. Bogotá, CO: Editorial Universidad Pedagógica

Nacional.

Corbin, J., &

Strauss, A. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Grounded

theory procedures and techniques. London, UK: Sage.

Correa, D. (2010). Developing academic literacy and

voice: Challenges faced by a mature ESL student and her instructors. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional

Development, 12(1), 79-94.

Gee, J. (2008). Social

linguistics and literacies. Ideology in discourses.

(3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Goatly, A. (2000). Critical

reading and writing. An introductory coursebook. London, UK: Routledge.

Grundy, S. (1987). Curriculum: Product or praxis?

London, UK: Falmer Press.

Hyland, K. (2004). Genre

and second language writing. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan

Press.

Johnson, B., & Christensen, L. (2004). Educational

research. Quantitative,

qualitative, and mixed approaches.

Boston, MA: Pearson.

Lillis, T. M. (2001). Student writing:

Access, regulation, desire. New York, NY: Routledge.

Lin, S., Monroe, B., & Troia,

G. (2007). Development of writing

knowledge in grades 2-8: A comparison of typically developing writers and their

struggling peers. Reading and Writing

Quarterly, 23(3), 207-230.

Morrison, B. (2010). Developing a culturally-relevant

genre-based writing course for distance learning. Language Education in Asia, 1, 171-180.

Nanwani, S. (2009). Linguistic challenges lived by university students in Bogotá in

the development of academic literacy. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 11, 136-148.

Ramírez, L. A. (2007). Comunicación y discurso. La perspectiva

polifónica de los discursos literarios, cotidianos y científicos

[Communication and discourse.

The polyphonic perspective of

literary, scientific, and daily discourses]. Bogotá, CO: Editorial Magisterio.

Sagor, R. (2000).

Guiding school

improvement with action research. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Sagor, R. (2005).

The action research guidebook: A

four-step process for educators and school teams. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin

Press.

Sandin, M. P. (2003). Investigación cualitativa en educación: fundamentos y tradiciones [Qualitative research in education:

foundations and traditions]. Madrid, ES: McGraw Hill.

Street, C. (2003). Pre-service teachers’ attitudes about writing

and learning to teach writing: Implications for teacher educators. Teacher Education Quarterly, 30(3), 33-50.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind

in society: The development of higher psychological processes.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

White, R., & Arndt, V. (1991). Process

Writing. London, UK: Longman.

Widodo, H. P.

(2006). Designing a genre-based lesson plan for an academic

writing course. English Teaching:

Practice & Critique, 5(3), 173-199.

Zúñiga, G., & Macías,

D. (2006). Refining

students’ academic writing skills in an undergraduate foreign language

teaching. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje

y Cultura, 11(17), 311-336.

About the

Authors

Pedro Antonio Chala Bejarano is a teacher of English at Pontificia

Universidad Javeriana (Colombia). He holds a BA in

Philology and Languages (Universidad Nacional de

Colombia) and an MA in Foreign Language Teaching (Universidad Pedagógica Nacional,

Colombia). His professional interests include EFL writing and materials design.

He has authored school and university EFL teaching materials.

Claudia Marcela Chapetón is an associate professor at Universidad Pedagógica

Nacional (Colombia). She holds a BA in English and

Spanish, an MA in Applied Linguistics (Universidad Distrital

Francisco José de Caldas, Colombia), and a PhD in Applied Linguistics

(University of Barcelona, Spain). Her research interests include literacy,

metaphor, and corpus linguistics. She has authored EFL teaching materials and

textbooks.

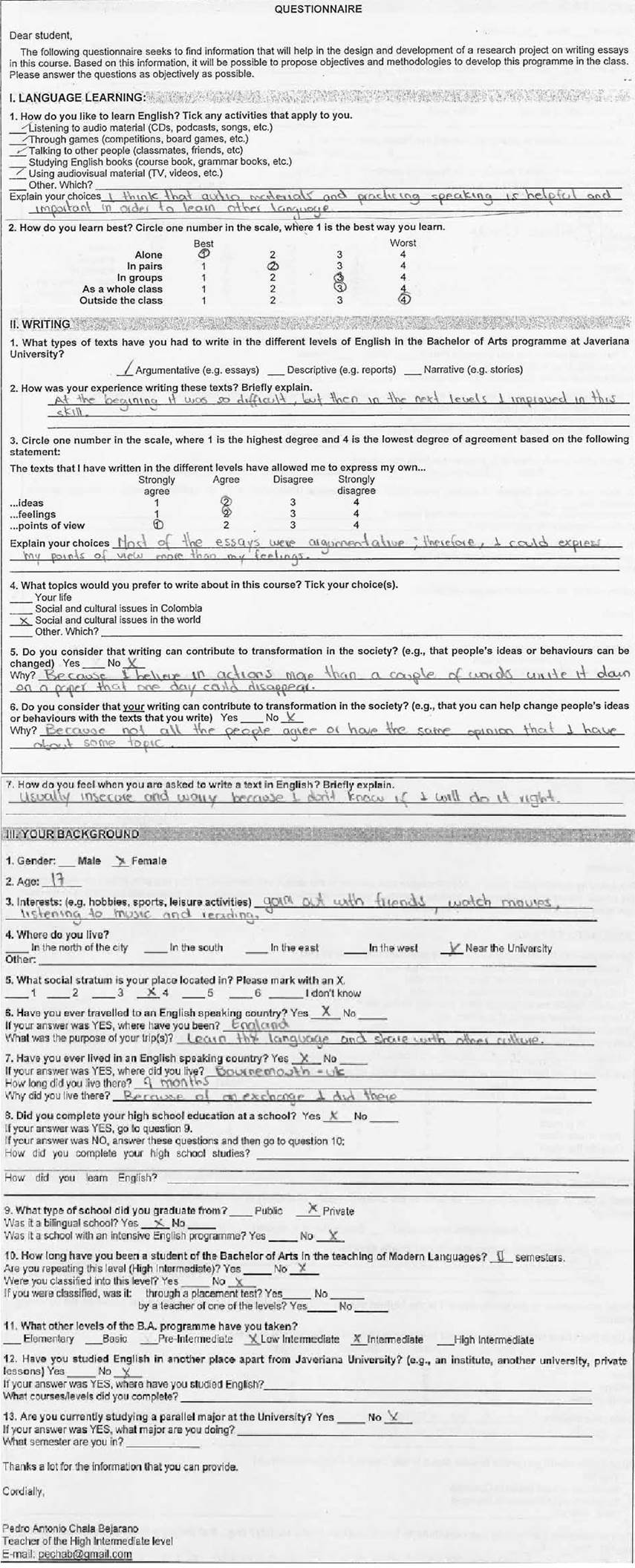

Appendix A: First Questionnaire Sample

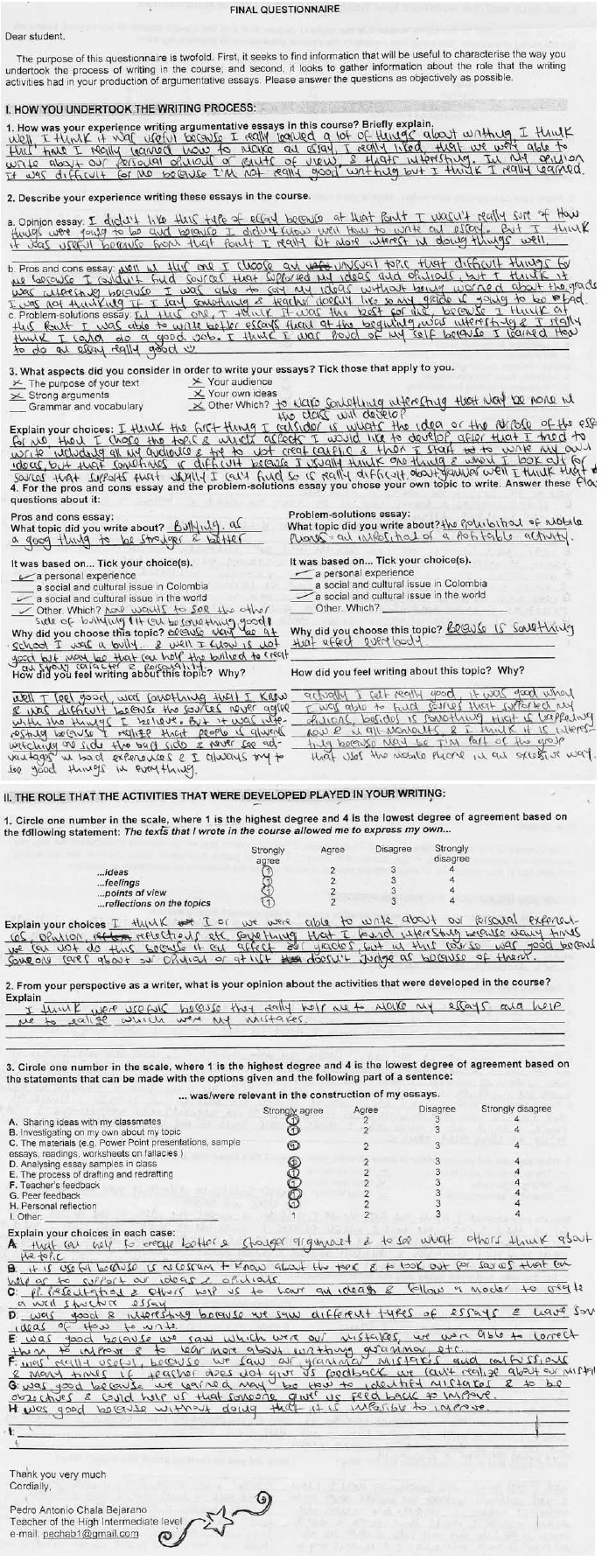

Appendix B: Second Questionnaire Sample

Appendix C: Sample Interview Protocol

First

Semi-Structured Interview

Research Question:

What is the role of a set of writing tasks in the

creation of argumentative texts by high intermediate students in the Bachelor

Degree in Modern Languages programme at Universidad Javeriana when writing is understood as a situated social

practice?

Interview Schedule