PROFILE

Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

Vol. 16, No. 1, April 2014 ISSN 1657-0790 (printed) ISSN 2256-5760 (online)

doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n1.37232

The Design of a Rubric to Evaluate Laboratory Reports in Astronomy: Academic Literacy in the Disciplines

El diseño de una rúbrica para evaluar informes de laboratorio en Astronomía: la alfabetización académica en las disciplinas

María Cristina Arancibia Aguilera*

Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

This article was received on February 21, 2013, and accepted on October 18, 2013.

A rubric was developed to evaluate laboratory reports written by undergraduate students of astronomy and astrophysics from Universidad Católica de Chile. The process of elaboration, peer validation, and application of the rubric to the evaluation of written tasks extended from August 2011 to August 2012. The instrument proved to be effective as an assessment tool that guides teachers towards the fundamental criteria that must be considered when evaluating their students’ writing. Moreover, the instrument provides useful guidelines to direct students’ attention towards the critical components of the laboratory report genre.

Key words: Academic genre, academic literacy, assessment, laboratory report, rubric.

Se elaboró una rúbrica para evaluar informes de laboratorio escritos por estudiantes de pregrado de la carrera de Astronomía y Astrofísica de la Universidad Católica de Chile. El proceso de elaboración, aplicación y posterior validación de la rúbrica por expertos abarcó desde agosto del 2011 hasta el mismo mes del 2012. El instrumento mostró efectividad como una herramienta que guía a los profesores hacia los criterios fundamentales que deben considerarse cuando se evalúan informes de laboratorio. Además, la rúbrica propuesta establece parámetros que enfocan la atención del estudiante hacia las características fundamentales del género informe de laboratorio.

Palabras clave: alfabetización académica, evaluación, género académico, informe de laboratorio, rúbrica.

Introduction

At the turn of the twenty-first century, Fairclough (2000) announced the birth of a new rhetoric of reconciliation that advocates for economic progress and social justice. This alignment, however, has not been the only new development. In the last ten years, as Rose (2005) claims, the discourse of economic production has colonized education as well as social and scientific research. The demands imposed by capitalist economic models to improve and increase production have extended to academic life. This philosophy is embodied in the aggressive emphasis that many universities place on the evaluation of the academic performance of their scholars, which is based almost exclusively on the production and publication of papers in widely known indexed journals. This emphasis on publication has posed a challenge to the high school and tertiary education curriculum to develop writing competences that prepare students for professional and academic life.

Successful writing programs in Australia (Christie & Martin, 2007) seek to re-contextualize science into the school curriculum. That is, these writing programs translate the scientific discourse produced at the research level into a pedagogic discourse to develop in their high school students the writing competences that will prepare them to write in the fields of science and technology in tertiary education. Similar efforts have been made in numerous countries, which have years of experience in the implementation of writing laboratories in schools and universities.

Unlike developed countries, Latin America has been struggling for decades to raise the population’s literacy level in its mother tongue. Most public schools focus on the development of general literacy skills in primary and secondary schools, to the detriment of the implementation of a curriculum focused on the formation of academic skills that would train students in the abilities necessary to meet the demands of tertiary education.

Studies conducted in a number of nations in South America (Arnoux, Di Stefano, & Pereyra, 2002; Bazerman, 2000; Carlino, 2003, 2004, 2006; Rosales & Vásquez, 1999) confirm that academic failure in the region during the freshman year of college is largely due to difficulties in the completion of reading and writing tasks that constitute the core of most college courses. This situation remained unaltered until the early twenty-first century, when the tentative implementation of writing courses in universities in Argentina, Chile, and other South American countries began.

A decade later, the experience in Chile has proven successful; however, the courses currently offered are not open to the entire community of students but, rather, have been tailored to serve the needs of a few schools in the university. In the meantime, professors have also expressed their concern as to the urgent need for the development of reading and writing skills in English, as this is the lingua franca of scientific publication. This problem adds to the fact that academic literacy in the native language (L1) does not automatically transfer to a foreign language (L2). In most cases, having to work in both languages may be the cause of strong sources of interference that affect the writer/speaker’s performance in the mother tongue and in the target language.

For the past 20 years, government policies have aggressively tackled the teaching of English in Chilean schools; however, results from international exams evaluating the implementation of numerous measures to improve the level of English proficiency in students show only modest progress. Universidad Católica de Chile acknowledges that this problem affects foreign language teaching at the elementary and high school levels and requires every student to certify they have reached an intermediate level of proficiency in English before the completion of their undergraduate studies. Freshmen who fail an exam that is given to all students upon entrance to university must take English courses and obtain certification before they finish their studies. However, such courses aim to develop general communicative skills that favor the development of oral production skills.

This paper describes and discusses the inter-disciplinary process of elaborating a rubric (see Appendix) that helps professors from the Department of Astronomy from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile to evaluate laboratory reports written by sophomore students of Licenciatura en Astronomía (teaching of astronomy major). The paper provides an overview of academic literacy in tertiary education in South America, specifically in the Chilean context. Then, it focuses on a brief description of the conditions for the production of a laboratory report in the field of astronomy. Finally, the paper tackles the use of rubrics to guide the process of producing and assessing written discourse in the field of astronomy.

Academic Literacy in South American Universities

The epistemic nature of reading and writing places both processes at the core of the debate over the critical role that the comprehension and production of academic texts has in highly literate contexts. It is well known that reading and writing in academic environments in many South American countries is mostly addressed in tertiary education, quite late considering the cognitive complexity that encompasses the development of receptive and productive skills in disciplinary areas. In addition to a late start in the development of academic literacy skills, obsolete teaching practices in high schools value the rote reproduction of content taught in class over the development of an enquiry-based approach to learning.

Writing instruction in most Latin American high schools is disregarded as an epistemic tool, as its use has been reduced to the reporting of facts discussed in textbooks. In countries such as Chile, writing is not considered part of the national selection system to enter university. This mode of selection was eliminated from the national admission examination in 1966, and its inclusion has not been a matter of concern since then. The consequence of Chile’s long-standing exclusion policy has been the creation of a gap between the literacy abilities that freshmen have developed over the course of twelve years of schooling and the high demand of the writing tasks faced by students in their first year at university.

The context of university freshman classes is dominated by the significant number of individuals who exhibit only a modest development of academic literacy skills, aggravated by little experience in the performance of research tasks. Looking for and finding information in libraries and electronic sources often become insurmountable obstacles to first year students. In addition, freshmen see themselves forced to overcome academic shortcomings in a trial and error fashion, as there is no one to assist them in the process of becoming active apprentices in the academic community (Arnoux et al., 2002; Bazerman, 2000, 2012; Carlino, 2003, 2004, 2006).

As we have asserted earlier, writing in academic settings implies the construction of an identity, a process that begins with individuals stepping into a disciplinary arena and observing from a peripheral standpoint how knowledge is processed, negotiated, and communicated between experts. This period is then followed by a training stage in which apprentices apply particular disciplinary discourse traditions not only to transmit information but also to exchange ideas and evaluate and validate their own perspectives in strict adherence to the norms and conventions of the community (Harvey, 2005; Harvey & Muñoz, 2006; Moyano, 2007).

The Laboratory Report Genre in Astronomy

Genre studies conducted in Chile (Harvey, 2005; Harvey & Muñoz, 2006; Núñez & Espejo, 2005; Oyanedel, 2005; Parodi, 2005) argue for the importance of establishing conceptual differences between a discourse community (Swales, 1990) and a community of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991). According to Harvey and Muñoz (2006), the former refers to what Swales calls a socio-rhetorical group, that is, a circle with the purpose of maintaining and extending knowledge. A community of practice refers to the development of a master-apprentice relationship as a result of group interaction between members of a community who hold different levels of knowledge and skill development.

The foundations of academic literacy lie in the master-apprentice bond constructed as a result of interaction and discourse negotiation, which is not limited to communication between experts and apprentices but also including interaction between apprentices holding different skills and proficiency levels in writing (Rose & Martin, 2012). As Wenger (1998) postulates, communities of practice, unlike discourse communities, are open to new members and provide them with opportunities to participate and continuously acquire and contribute knowledge. This research is in accord with the notion of the community of practice, as its definition best supports the principles of academic literacy in the university context.

The basis of our proposal is rooted in the genre-based approach to writing that emerged in the mid-1980s in Australia and New Zealand, among other countries. The principle that justifies this approach is that human beings process and understand meaningful pieces of information; therefore, texts are processed as social events that occur in situational contexts in which writers use language to meet rhetorical purposes. According to Callaghan and Rothery (1988), Martin and Rothery (1993), and Rose and Martin (2012), teaching writing entails the creation of awareness of how different texts are structured to satisfy a given communicative goal. The implication here is that teachers must emphasize not only linguistic resources authors use to convey meaning but also discourse structure, register, and concept use and control.

The genre-based approach takes a top-down perspective, as it emphasizes the social functions of a text, defined by the interweaving of three essential components: field, tenor, and mode. The field lays the grounds for the events to be narrated, discussed, described, and so forth. The tenor refers to the social roles enacted by the readers and writers of the laboratory report. Finally, the mode, in the specific case of the laboratory report, denotes a densely written task (Rose & Martin, 2012).

We conducted a semi-structured interview prior to the analysis of the two hundred laboratory reports written by undergraduate students of Licenciatura en Astronomía from Instituto de Astrofísica (Institute of Astrophysics) of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile that comprise the corpus of this study. The interview consisted of four questions, the purpose of which was to help the researchers visualize the purpose of the laboratory report, the stages that comprise its structure, and the purpose each stage serves in the overall process of knowledge construction entailed in this type of writing in the discipline. The interviewee was the professor teaching Taller de Astronomía (Astronomy Workshop) I and II at the time this study was conducted.

The answers provided by the teacher show that an adequate laboratory report aims to communicate the results of an experiment and includes an abstract, objectives, introduction, a reference to the experiment performed and the procedure carried out, results and analysis, and, finally, conclusions. In all, the representation of a laboratory report that faculty members seem to agree upon defines the genre as the synthesis of an experience, including the procedure used in the performance of the experiment. However, they also consider a laboratory report to be bibliographic research that integrates different perspectives on a single topic. This definition forms the basis of the process of developing a rubric to evaluate laboratory reports.

Rubrics to Guide the Process of Producing and Assessing Written Tasks in EFL

The extensive use of rubrics for evaluative purposes has become a new trend in education. In 2001, the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) produced a complete description of linguistic, sociolinguistic, and pragmatic competences that learners of foreign languages must demonstrate at different levels of proficiency in the performance of written and oral tasks. The rubrics presented by the CEFR show a detailed account of elements that play a critical role in oral presentations, face to face interactions, letter writing, and other communicative tasks that are fulfilled in either the oral or written modes of language.

The production of texts in a foreign language entails a strategic organization of linguistic, sociolinguistic, and pragmatic resources and the combination of different competences involved in writing in L2. Flower and Hayes (1981) and Hayes (1996) suggested that written production can be conceived as a three-stage process, which mainly consists of planning, translating, and revising. Each stage in the cognitive model postulated by Flower and Hayes is subdivided into sub-stages that involve cognitive processing in which L2 learners engage while composing. In most cases, English as a foreign language (EFL) learners tend to divide planning into a stage of rehearsal in which individuals analyze the purpose of a given writing task to consider the type of audience they are addressing and mobilize the necessary language resources to adjust their writing to the objective of the task. During the translation stage, L2 learners display compensation strategies to counterbalance the lack of linguistic, sociolinguistic, and/or pragmatic resources while writing. Another strategy commonly used by individuals is called “trying out,” the mechanism by which learners test the appropriateness of using certain language resources in specific contexts. The evaluation stage is characterized by two sub-stages, monitoring and self-correction or repair, metacognitive strategies usually used by foreign language learners to reflect upon their own writing.

In the late 1990s and early twenty-first century, Hayes (1996) and Deane, Sabatini, and Fowles (2012), respectively, suggest that writing is a social activity, the learning of which involves developing strategies to accomplish the array of purposes that underlie negotiations of discourse in every culture. Deane et al. (2012) expand what had been claimed by Bereiter and Scardamalia (1987), Flower and Hayes (1981), and Hayes (1996) in an updated model of writing that synthesize these earliest models.

Given that writing is a social activity that results from the negotiation of genre in every culture, our enquiry into the assessment of writing tasks applies a psycho-sociolinguistic approach to this public activity. Writing as a psycholinguistic activity entails myriad complex cognitive abilities that writers must mobilize and apply during the process of composing. Deane (2010) and Deane et al. (2012) suggest grouping the complex skills involved in the writing process under the sets of abilities that would globalize the essence of every skill activated while composing. The authors argue that, in the process of writing, there is a set of reflective, expressive, and receptive skills involved, which matches the planning, translation, and revision skills in classical models. The activation of skills across the process of writing is closely connected to the multiple cognitive representations of pragmatic, sociolinguistic, and linguistic competences in play during composing. These competences have a critical role in the successful completion of the written task and become fundamental in the design of a rubric that may assist professors and students in the process of teaching and learning to write. The authors distinguish three fundamental skills in what they postulate as a competency model, that is, a representation of the competences at play in writing.

The model proposed by Deane (2010) distinguishes a first skill, language and literacy, which operates at a sentence level and comprises conventions underlying the use of standard language, clarity and variety of sentence structure, and command of vocabulary. The second skill is writing strategies, and its main focus is document level skills, or the competences of organizing, placing emphasis, and developing a topic in writing tasks. The third and last skill is critical thinking for writing, which involves content-related and socially defined background skills, that is, abilities pertaining to the mastery of argumentation and evaluation beyond the adjustment to standards for writing in academic settings, such as those related to the social role that a writer has in the academia.

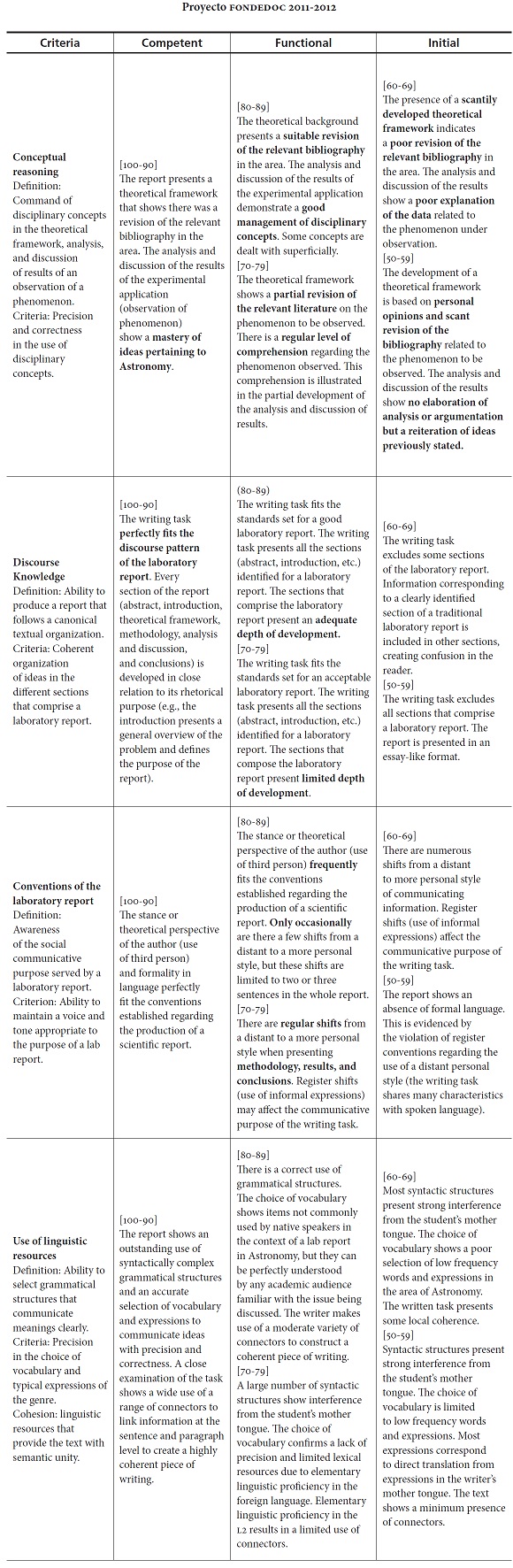

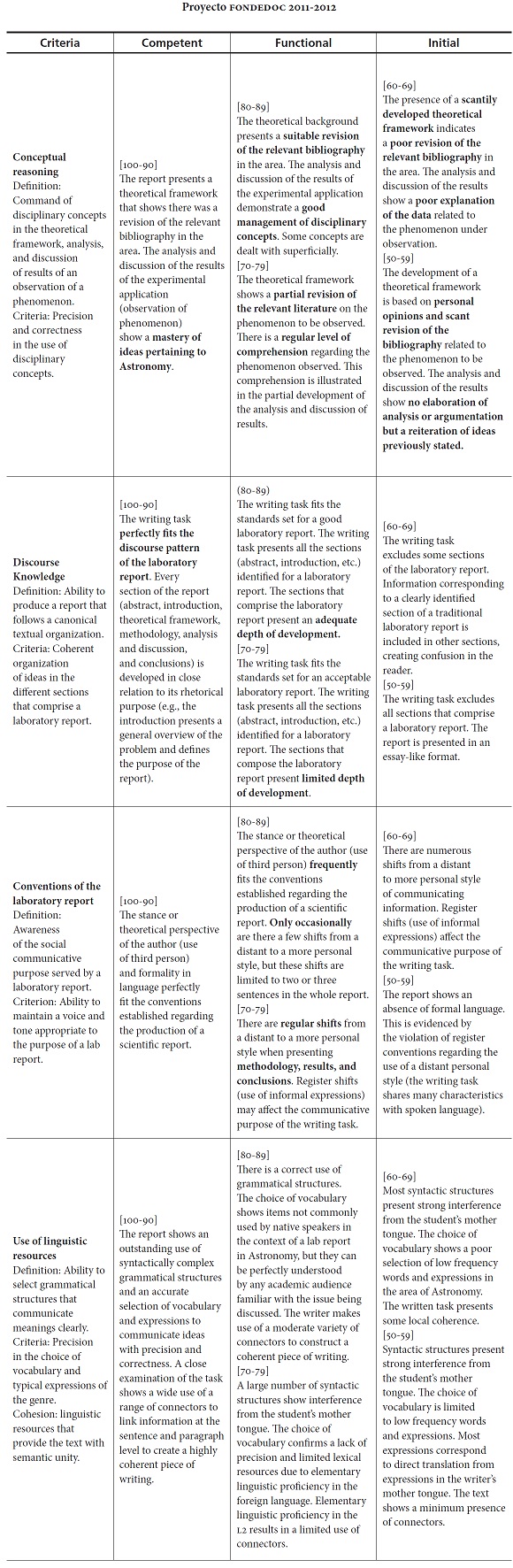

The rubric proposed in this study follows the principles postulated by Deane (2010) and Deane et al. (2012) for assessing writing in academic settings. There are three components to the rubric discussed in this paper. The first are the criteria or conditions that a written task must meet. Next are the descriptors or explanations of the criteria at each level of performance. The third component is the scaling or level of proficiency writers usually show in the performance of a written task.

Criteria and Scaling to Evaluate Writing Performance in Laboratory Reports

Writing as a psycholinguistic activity entails triggering the reflective, expressive, and receptive modes of thought that are at work across the process of writing. Every mode of thought activates cognitive skills connected to the pragmatic, sociolinguistic, and linguistic representation of the writing task during planning, writing, and editing (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1987; Flower & Hayes, 1981; Graham & Perin, 2007; Marinkovich, 2002). The criteria identified for the rubric proposed in this paper conform to several forms of the cognitive representations that derive from the pragmatic, sociolinguistic, and linguistic competences involved in writing.

According to Deane (2010), the first of the varied representations constructed in the writing process is social and rhetorical elements. This representation refers to a mental image of the written task that writers construct in light of the social and institutional context in which the writing task is embedded. The second representation corresponds to what Deane calls conceptual elements, a representation of the subject matter to be dealt with. The third is textual elements and comprises representations of the text structure and coherence. The fourth is verbal elements, which entail the linguistic representation of sentences and propositions. The last corresponds to lexical/orthographic elements, which show how verbal elements are instantiated in written texts.

Based on the numerous mental representations that play a critical role in cognition during writing (Deane, 2010), the rubric we propose in this study identifies as its first criterion the conventions of the laboratory report. This standard defines competent writing as the writer’s demonstrated ability to take an impersonal theoretical approach to the task of addressing the rhetorical problem. A competent writer is able to use language and expressions in a manner appropriate to the conventions of a formal register. In addition, a writer at a competent level presents information synthetically and shows some creativity in the communication of information. Creativity is understood as the ability the writer has to express the product of their findings in his/her own words.

The second criterion corresponds to conceptual reasoning, the substantial mastery of disciplinary concepts that a competent writer demonstrates in the careful selection of ideas that exceed in quality and number the concepts delineated by a reference framework traditionally known to a learner. Under conceptual reasoning, we can also consider the ability to construct coherence, that is, the skill of a proficient writer in controlling the inclusion and exclusion of information on the basis of his/her knowledge of the target audience. Disciplinary writing implies that a task is being addressed to an audience that is familiar with the topic of discussion; therefore, a skilled writer knows what information to omit due to its obviousness.

Another criterion considered essential to the evaluation of academic writing is discourse knowledge. This standard implies that a writer at a proficient level can produce a written task that follows a textual pattern, but it also considers the rhetorical movements or move and step analysis discussed by Swales (1990). Rhetorical movements, according to Swales, are the foundations of genre because these moves give every section of the research paper, journal article, or laboratory report the essence by which we recognize an introduction as such (Swales, 1990).

Finally, the last criterion considered fundamental for writing in a foreign language is use of linguistic resources. This aspect involves the ability to use complex grammatical structures and an accurate selection of vocabulary to communicate ideas with precision and clarity. A proficient writer is capable of selecting a wide variety of connectors to produce a coherent and cohesive piece of writing that fits the demands of a laboratory report in the target field.

The scaling defines three levels of proficiency, namely: competent, functional, and initial. The names chosen for the scales conform to the principle underlying evaluation for learning (East, 2009; Knoch, 2011), that is, observed mistakes identify the challenges learners must tackle to advance to a higher level of performance.

The performance level named competent comprises skills that clearly go beyond core expectations. That is, competent writers show a critical and reflective approach to the issue being discussed, demonstrated in the ability of individuals to integrate and apply new knowledge with some independence from what recognized authors postulate about the topic under study. The next level is called functional and describes the ability of an individual to complete a writing task by meeting the basic requirements. At this level, writers usually engage in the completion of the writing task with very little independence from what authorities assert about the issue being discussed. This level is manifested by the choice of concepts and linguistic resources to paraphrase what other authors assert about the topic. There is little space for interpretation and discussion of the task by the author. The last level, called initial, is intended to describe writers who have not yet reached the basic level of expectations. At this level, readers are most likely to find concepts incorrectly used or defined and the presence of many mistakes in the choice of linguistic resources.

One of the greatest challenges that professors may face when designing a rubric is the complexity that demands the description of abilities according to criteria for every performance level. Such descriptions require a clear assessment of abilities that are involved in writing that are not considered part of the disciplinary content. Most professors ignore the technical names of standards or cannot make a clear distinction between them. Another possible difficulty is the approach the professor takes when describing abilities, as most feedback concentrates on negative aspects of assignments. The design proposed in this paper focuses on abilities that characterize each performance level; therefore, the concepts are positive and indicate the challenges the student must overcome to reach a level of writing that qualifies them to be considered part of a given community of knowledge.

The classical models of writing proposed by Bereiter and Scardamalia (1987) suggest that a way to scaffold students’ advances for a more mature level is to provide them with common phrases or expressions grouped according to their rhetorical functions; for example, introducing a new idea, elaborating the idea previously introduced, etc. Students could then count on the linguistic resources necessary to construct a fluent and well-structured writing task. The idea we propose in this paper consists of developing lists of linguistic resources grouped according to the rhetorical function they serve in the different sections of a laboratory report. These guidelines would awaken students’ awareness of how experts structure an abstract in a laboratory report. An analysis of how information is conveyed linguistically gives students a basis from which to start their own writing tasks.

Another critical aspect in the design of a teaching/learning instrument of evaluation is the feedback that teachers may derive from its use. An essential feature of a rubric is its focus on competences, that is, the emphasis on skills that characterize the writing process at a competent, functional, and initial level. The focus on competences usually describes what the individual can do at a certain level of proficiency. The strength of a rubric as a teaching/learning instrument of evaluation lies in the positive statement of the skills an individual is capable of displaying during the complex process of planning, composing and revising. Consequently, the feedback generated by the use of rubrics to evaluate written tasks concentrates on the skills the writer exhibits in the completion of a task and also provides the writer with information about how distant/close their writing may be to becoming competent.

Conclusions

This paper reasserts the classical reading-writing connection that makes both activities fundamental to academic literacy in tertiary education. Comprehension is critical, as discourse is the product in which habits of thinking are realized. That is, written production entails the careful selection, evaluation, and integration of information in a discourse to provide a critical view of different perspectives that coexist in the study of a given phenomenon.

Currently, writing is no longer seen as a solipsist cognitive process that begins and ends with the individual. Today, writing entails the performance of a social and political activity that involves the negotiation of identity in close connection with the individual’s social role in a community. The concept of communities of practice, developed in the late 1990s by Wenger (1998), serves as the basis of academic literary. This concept has been found to represent perfectly the apprentice-expert-other apprentice relationship that scaffolds the development of literacy skills in new members.

This apprentice-expert relationship has been, as a matter of fact, almost non-existent in most South American universities. This phenomenon is explained by the dominant belief that the development of academic literacy is a responsibility of high school teachers. Consequently, for a long time, universities did not assume their share in the responsibility of fostering the development of skills to comprehend and produce the discourse at the heart of every academic community. The result of this long-standing belief has certainly affected the academic performance of undergraduates, who frequently struggle to meet the requirements of an academic life that does not provide them with the necessary tools to succeed.

The design of a rubric that serves the purpose of evaluating written tasks and specifying useful guidelines to write laboratory reports has resulted in an arduous but rewarding task because it has enabled the construction of an interdisciplinary dialogue between astronomers and linguists to create an instrument of evaluation that responds to the production conditions of laboratory reports in astronomy in a foreign language.

Inspired by a model of writing suggested by Deane (2010) and encouraged by the proposal of a genre-based pedagogy by Rose and Martin (2012), the rubric described in this paper emphasizes the competences involved in the representation of the rhetorical problem in its social, discursive, linguistic, and disciplinary aspects. The rubric we propose describes skills writers usually demonstrate at an initial, functional, and competent level of performance. The scaling conforms to a view of writers as apprentices who are expected to evolve from a beginner level of proficiency in writing to an advanced performance level that will allow them to become potential members of the community of practice, as defined by astronomers.

References

Arnoux, E., Di Stefano, M., & Pereyra, C. (2002). La lectura y la escritura en la universidad [Reading and writing at university]. Buenos Aires, AR: Eudeba.

Bazerman, C. (2000). Shaping written knowledge: The genre and activity of the experimental article in science. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. Retrieved from http://wac.colostate.edu/books/bazerman_shaping/

Bazerman, C. (2012). Genre as social action. In J. P. Gee & M. Handford (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 226-238). London, UK: Routledge.

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1987). The psychology of written composition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Callaghan, M., & Rothery, J. (1988). Teaching factual writing: A genre based approach. Marrickville, AU: DSP Literacy Project, Metropolitan East Region.

Carlino, P. (2003). Alfabetización académica: un cambio necesario, algunas alternativas posibles [Academic literacy: A necessary change, some posible alternatives]. Educere, 6(20), 409-420.

Carlino, P. (2004). Leer y escribir en la universidad [Reading and writing at university]. Buenos Aires, AR: Asociación Internacional de Lectura.

Carlino, P. (2006). Escribir, leer y aprender en la universidad [Writing, reading, and learning at university]. Buenos Aires, AR: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Christie, C., & J. R., Martin (Eds.). (2007). Knowledge structure: Functional linguistic and sociological perspectives. London, UK: Continuum.

Deane, P. (2010). The skills underlying writing expertise: Implications for K-12 writing assessment. Princeton, NJ: ETS.

Deane, P., Sabatini, J., & Fowles, M. (2012). Rethinking K-12 writing assessment to support best instructional practices. In C. Bazerman, C. Dean, J. Early, K. Lunsford, S. Null, P. Rogers, & A. Stansell (Eds.), International advances in writing research: Cultures, places, measures (pp. 83-101). Fort Collins, CO: Parlor Press.

East, M. (2009). Evaluating the reliability of a detailed analytic scoring rubric for foreign language writing. Assessing Writing, 14(2), 88-115.

Fairclough, N. (2000). New labour, new language? London, UK: Routledge.

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College Composition and Communication, 32(4), 365-387.

Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools—A report to the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellence in Education.

Harvey, A. (2005). La evaluación en el discurso de informes escritos por estudiantes universitarios chilenos [Evaluation of discourse in written reports by Chilean university students]. In M. Pilleux (Ed.), Los contextos del discurso (pp. 215-228). Santiago, CL: Frasis.

Harvey, A. M., & Muñoz, D. (2006). El género informe y sus representaciones en el discurso de los académicos [The genre “report” and its representations in the discourse of members of the academia]. Estudios Filológicos, 41, 95-114.

Hayes, J. R. (1996). A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing. In C. M. Levy & S. Randall (Eds.), The science of writing: Theories, methods, individual differences, and applications (pp. 1-27). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Knoch, U. (2011). Rating scales for diagnostic assessment of writing: What should they look like and where should the criteria come from? Assessing Writing, 16(2), 81-96.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Marinkovich, J. (2002). Enfoques de proceso en la producción de textos escritos [Process approach in the production of written texts]. Revista Signos, 35(51-52), 217-230.

Martin, J. R., & Rothery, J. (1993). Grammar: Making meaning in writing. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), The powers of literacy: A genre approach to teaching writing (pp. 137-154). London, UK: The Falmer Press.

Moyano, E. (2007). Enseñanza de habilidades discursivas en español en contexto pre-universitario: una aproximación desde la LSF [Discourse abilities in Spanish in pre-university contexts: An SFL approach]. Revista Signos, 40(65), 573-608.

Núñez, P., & Espejo, C. (2005). Estudio exploratorio acerca de la conceptualización del informe escrito en el ámbito académico [Exploratory study about the conceptualization of the written report in academic contexts]. Harvey, A. (Ed.) En torno al discurso. Contribuciones de América Latina (pp. 135-148). Santiago, CL: Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile.

Oyanedel, M. (2005). Lo descriptivo en informes escritos de estudiantes universitarios [Descriptive strategies in written reports by university students]. Onomázein, 11(1), 9-21.

Parodi, G. (Ed.). (2005). Discurso especializado e instituciones formadoras [Specialized discourse and educational institutions]. Valparaíso, CL: Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso.

Rosales, P., & Vázquez, A. (1999). Escritura de textos académicos y cambio cognitivo en la enseñanza superior [Composition of academic texts and cognitive change at higher education]. Revista del Instituto de Investigaciones en Ciencias de la Educación, 8(15), 66-79.

Rose, D. (2005). Democratising the classroom: A literacy pedagogy for the new generation. Journal of Education, 37, 131-167.

Rose, D., & Martin, J. R. (2012). Learning to write, reading to learn: Genre, knowledge and pedagogy in the Sydney school. Sheffield, UK: Equinox Publishing.

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

About the Author

María Cristina Arancibia Aguilera, Doctorate in Linguistics from Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, works as an assistant professor in the Department of Linguistics at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Her areas of expertise include the evaluation of comprehension and production of discourse in foreign language and critical discourse analysis.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Gaspar Galaz from the Instituto de Astrofísica of the Universidad Católica de Chile for his valuable feedback and continuous support for the undertaking of the research summarized in this paper.

This article is part of the Project FONDEDOC 2011 “La evaluación de informes de laboratorio escritos en inglés por estudiantes de Licenciatura en Astronomía: una mirada interdisciplinaria” funded by the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Appendix: Rubric for the Evaluation of Laboratory Reports