PROFILE

Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

Vol. 16, No. 1, April 2014 ISSN 1657-0790 (printed) ISSN 2256-5760 (online)

doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n1.37843

From Drills to CLIL: The Paradigmatic and Methodological Evolution Towards the Integration of Content and Foreign Language

Desde las repeticiones en el aula hasta AICLE: la evolución paradigmática y metodológica hacia el aprendizaje integrado de contenido y lengua extranjera

Rosa Muñoz-Luna*

Universidad de Málaga, Málaga, Spain

This article was received on April 18, 2013, and accepted on October 18, 2013.

Content and language integrated learning has become a common practice in European higher education. In this paper, I aim to describe how this integrated teaching practice comes as a result of a paradigmatic and pedagogical evolution. For this purpose, the main linguistic paradigms will be revisited diachronically, followed by a revision of the main pedagogical trends in teaching English as a second language. This theoretical overview culminates in a predominantly constructivist practice that is more pragmatic and contextualized than ever before. From a language teacher’s standpoint and in language university classrooms, content and language integrated learning comes to solve the forever present decontextualization.

Key words: Content and language integrated learning, constructivism, contextualization, paradigm, pragmatics, English teaching techniques.

El aprendizaje integrado de contenidos y lengua extranjera se ha convertido en práctica común en la educación superior europea. En este artículo se describe cómo esta práctica de enseñanza integrada surge como resultado de una evolución paradigmática y pedagógica. Con ese fin, se revisan diacrónicamente los distintos paradigmas lingüísticos, seguidos de una descripción de los métodos pedagógicos en la enseñanza del inglés como segunda lengua. Este recorrido teórico culmina en una práctica constructivista predominante que es más pragmática y contextualizada que ninguna otra usada con anterioridad. Desde la perspectiva del profesorado de idiomas y dentro de un aula de idiomas universitaria, el aprendizaje integrado de contenidos y lengua extranjera ofrece la solución al problema constante de la descontextualización.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje integrado de contenidos y lengua extranjera, constructivismo, contextualización, paradigma, pragmática, técnicas de enseñanza del inglés.

Introduction

The term CLIL (content and language integrated learning) was adopted in 1994 to describe those school contexts in which children’s learning was taking place in a language other than their native language, or L1 (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010). Originally, CLIL came out of immersion and bilingual programmes in primary schools during the 1960s-1980s, when learners were asked to practise foreign language (L2) skills to learn a discipline (Brinton, Snow, & Wesche, 2011). However, it has now spread to all socioeconomic backgrounds, not only to the elite schools that previous programmes were designed for. CLIL is the consequence of recent European policies committed to the learning of other languages within natural environments. In this shared European context, every EU country has undergone different historical factors that have shaped their present language teaching situations. In the case of Spain and other Western European countries, CLIL is an innovative measure that needs some time and training to be fully implemented (Lasagabaster & Ruiz de Zarobe, 2010).

This gradual carrying out of bilingual programmes is still in its early stages even after 15 years of continuous political pressure (Salaberri, 2010). To understand this development, the present paper aims to theoretically describe the paradigmatic and pedagogical evolution that L2 teaching has undergone in some Spanish universities. I first describe the continuing changes in the linguistic paradigms: from initial structuralist approaches to language teaching, we have moved to pragmatic assumptions under which the context is crucial for learning. Because these linguistic paradigms evolved, pedagogical techniques have also undergone radical changes from drills to specific genre approaches. Pragmatic contexts require certain methodological and constructivist actions, which then merge into CLIL courses.1

A Preliminary Note on Terminological Scope: Clearing the Terrain

The debate between languages for specific purposes (LSP) and CLIL becomes especially stronger in interdisciplinary fields such as those taught at the university level (e.g., English applied linguistics, French for tourism or pharmacology, among others). CLIL is not LSP, although it is debatable which is a category of which. They are similar in that they simultaneously use content and language, but whereas language is central to LSP (Kennedy, 2012), it is often secondary to CLIL. The issue of content over form is essential to CLIL, whereas in LSP, there is much overlapping of content and language: LSP allows for a form focus where CLIL does not. However, a sharp distinction between CLIL and LSP courses might be problematic if we use radical content-based or formbased methodologies.

CLIL is also a commitment to a combination of language fluency and content accuracy. A CLIL approach shapes syllabus contents and methodologies in the same way that LSP does, influencing the way things are taught in class. As Coyle et al. (2010) define it, CLIL “is a dual-focused educational approach in which an additional language is used for the learning and teaching of both content and language” (p. 1); therefore, CLIL combines disciplinary and language contents to create more meaningful contexts. From a linguistic perspective, CLIL is the natural consequence of true contextualisation in L2 classrooms, coming as a result of a necessary evolution in foreign language teaching.

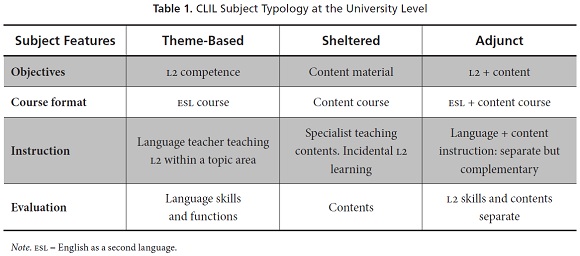

Political and educational bilingual demands have caused CLIL to expand progressively from primary schools to higher education sectors. Moreover, universities are promoting subject teaching in English in all degrees, something that can be done in different ways, as indicated by Brinton et al. (2011), who propose a diagram on CLIL modalities in higher education as shown in Table 1.

Sheltered and adjunct models are the most frequently used, although that will depend on the university degree and syllabus aims: Language becomes secondary in those subjects that are detached from a purely linguistic basis. In some cases, teachers tend to follow a sheltered curriculum in which language and content subjects are coordinated and coexist but in which predominance is given to contents. This sheltered preference is but the consequence of the natural evolution in the field of foreign language teaching: Specific genres and contents come to play a role, as we will see later in this paper.

A Diachronic Revision of the Linguistic Paradigms Regarding Language Teaching

Structuralism

The structuralist paradigm did not take place until the beginnings of the 20th century, but its roots can be found some decades earlier. This philosophical, cultural, and linguistic movement provided new ways of perceiving both language and human existence. Apart from being an inherent language property, structuration is equally inherent to human beings, who need to constantly modulate their realities and everything that surrounds them. This was Piaget’s opinion defending the idea of both human and linguistic structures in his work Structuralism (1970). These structures help to transform and self-regulate everything within their containing whole. Subsequently, the relationship between words’ structural features and their correlations with world entities was used for pedagogical purposes in the teaching of a foreign language.

In this teaching environment, Bloomfield (1983) presented language elements as phonological, morphological, and semantic structures that evolved throughout time, accounting for an integrating aspect of his linguistic theories. These linguistic notions became key references in the field of language teaching, and his classification of the parts of speech would be the basis for future studies. Undoubtedly, however, Bloomfield’s major contribution took place in foreign language teaching. His attention to detail, something typical in a structuralist linguist, helped enumerate the possible causes of failure in the process of second language acquisition. In this way, he revealed data on language skills three decades ago that could be applied to today’s language classrooms: “not one in a hundred (students) attains even a fair reading knowledge” (Bloomfield, 1983, p. 293).

Bloomfield himself, in an eclectic approach to the scientific study of language, linked the linguistic discipline to others such as psychology, ethnology, literature, and history, placing his research in the so-called domain of applied linguistics. In fact, after the 1960s and once structuralism flourished, post-structuralist works and authors appeared, going a step beyond in the study of language structures. This new period can be defined as a “second phase in the French structuralist philosophy . . . which broadens new horizons in structuralist research” (Sturrock, 1979, p. 174). Post-structuralism supports difference and individuality, in opposition to the systematisation of the previous years (Crotty, 2003).

As we can see, structuralist language analyses focus on language structures and forms, leaving meaning and context aside. This structure-centrism is reflected in repetitive learning and drills, where there is no room yet for classroom interaction.

Generativism

In the same way as structuralism, generativism relies on a number of theoretical principles that help in the understanding of language and the human mind; Chomsky (1995) called them “principles-and-parameters theory” (p. 13), which was intended to be not a theoretical framework but a novel way of addressing classical language problems. Originally, the generativist concept of grammar was a finite set of rules generating an infinite number of sentences in any language; for this reason, generativism is also called transformational or transformative grammar (Chomsky, 1988, 1995); syntax, semantics, and phonology are the main three pillars, and although they are interrelated, they maintain some degree of autonomy.

Generativism took into account native speakers’ intuitions because they are naturally predisposed to know what is grammatically correct and what is not. When analysing sentence grammaticality, Chomsky brought up a scale of language adaptation regarding its grammar. This adaptation took place at different levels: from an observational perspective, that is, knowing specific language features in a descriptive way and being able to interrelate them, and also from an explicative level, by accounting for the mental processes that speakers undergo (Chomsky, 1972).

The infinite possibilities of a finite group of language structures were one of Chomsky’s main ideas after he adopted the 19th century maxim that linguistics does not have to be dogmatic or normative. This principle becomes meaningful in a paradigm that opposes all previous forms of language analysis: generativist language analyses would allow for a more general perception of linguistic forms.

The relationship between the generativist paradigm and structuralism comes with the structuralists them- selves, who defined language elements by using certain rules that were crucial for later generativist studies. This is the case with Derrida (1971), who decomposed linguistic elements according to their differences with other elements in the same system. Derrida introduced the term “trace” as the feature that links one element to the rest and, at the same time, differentiates it from them. This author—as later generativists such as himself would do—considered written language more important than its oral form, in opposition to the traditional Western conception of language.

Generative linguistics is a cognitive science, and it explains language knowledge. Generativism aims at describing how we perceive language in our minds beyond its social applications. However, the field has its limitations owing to the complexity of human minds. Relevant scholars in the field have analysed human mental processes and compared them with computer processes, using a symbolic language to describe people’s cognitive behaviour. Cognitive activities are mental representations that are not on a biological or neurological level or on a social or cultural one. Therefore, language studies in generativism account for the ways language elements select forms and meanings in our brain (van Dijk, 2004), something that has limited pedagogical implications because no context or use is being considered here.

In a more recent publication, Chomsky (2000) goes into the study of language use making reference to other external factors: “No structural relations are invoked other than those forced by legibility conditions” (p. 11). In this case, general linguistics suppositions together with Chomsky’s theories are altered and conditioned by emotional and idiosyncratic factors that must be taken into account when analysing language. All of these extratextual factors have a crucial role in the next language paradigm: pragmatics, which deeply marks the course of foreign language teaching and learning.

Pragmatics

At the end of the 20th century, we can find a shift towards more pragmatic analyses in generativism. The structural complexity of minimalism (Chomsky, 1986) moved towards more pragmatic domains when it was split into different logical-semantic levels. These levels of functions made reference to the semantic properties of signs, and they were updated according to their contexts. The analysis of a linguistic sign from this post-generativist perspective took into account both contextual and cotextual issues, which foreshadowed a change in the study and teaching of languages.

Where structuralism examines linguistic signs and the possible changes that take place in them, pragmatics focuses on the causes of such changes, mainly those coming from outside of the linguistic system and those that provoke changes in either the system or its uses: for example, psycholinguistic, sociolinguistic, or environmental factors that influence word change and lexical meanings.

These extralinguistic constituents are clearly present in a language classroom by means of certain variables that are both gestural and situational and that determine and discriminate the meaning of a specific sequence of words. Regarding the cotext or written context, it is the written environment that gives meaning to the text, making it more real or comprehensible. Pragmatic scholars are now aware of the importance of linking language abstraction with more concrete factors such as context, individual variables, and communicative purposes. In fact, language is but a sign system made up of the cultural and extralinguistic variables that condition sign usage.

The pragmatic linguistic paradigm has been specifically linked with the field of foreign language teaching. Roever (2006) associates both pragmatics and teaching with what he calls “interlanguage pragmatics” (p. 230). Although many studies have been published on the acquisition and teaching of foreign languages, only recent analyses have considered pragmatics as the theoretical and multidisciplinary basis for the study of language.

What I have presented here as two opposing forces—theoretical and pragmatic paradigms—are but two representations of the same reality reflected on an abstract level (e.g., sentence-deep structure and lexicon) and on a concrete one (i.e., speech realisations and language use and context). To bridge the gap between theoretical paradigms and the pragmatic one, CLIL provides a multidisciplinary standpoint that combines language analyses from these divergent perspectives. Innovative structural approaches together with the content variables of linguistic signs are given within a communicative context in the classroom. Table 2 aims to merely describe the main differences among the different paradigms addressed in this section.

Every traditional linguistic paradigm has been linked with a specific theoretical teaching framework that best describes the conditions, procedures, and variables of a learning/teaching situation. Table 3—inspired by Guey, Cheng, and Shibata (2010)—notes the different paradigms previously described, together with their corresponding foreign language learning approaches.

As we can see, learning environments have also undergone an evolution in which context has gradually acquired a chief role. The increasing dependence on contextual factors is unavoidable in understanding and fostering the integration of content and foreign language in the classroom. This pragmatic contextualisation invites students to construct their language learning, as will be explained in the following section.

From Linguistic Paradigms to Knowledge Construction

The linguistic paradigm evolution follows a progression from objective linguistic foundations to a more humanized view of the building of L2 academic knowledge. These assumptions have modified teaching notions accordingly. Crotty (2003) defines this new theoretical approach as the fact that all knowledge “is being constructed in and out of interaction between human beings and their world, and developed and transmitted within an essentially social context . . . there is no true or valid interpretation of the world. There are useful interpretations” (pp. 42, 47).

The epistemological basis of this paradigmatic evolution is constructivism because it provides clear justifications for the ways students approach foreign language learning today. Constructivism has been always related to post-structuralism and post-modernism, but in fact, it is more related to a subjective epistemology. Both constructivism and post-modernism commit themselves to “ambiguity, relativity . . . fragmentation” (Coll et al., 2007, p. 43, 185), consisting of reality made up of several viewpoints and multiple existences.

Classroom constructivism includes some pragmatic elements that take the learning context into consideration by paying attention to linguistic signs and their communicative purposes (Larochelle & Bednarz, 1998). Features from different linguistic paradigms converge in linguistic constructivism because learners themselves are working with L2 forms, structures, texts, and purposes.

Constructivism is especially relevant in those cases in which nonnative speakers aim to be successful in L2 speaking and writing (Nagowah & Nagowah, 2009). Particular cognitive schemata should be developed in these processes: Not only does the linguistic barrier impede fluent discourse, but the academic genre also rules need to be constructed under foreign frameworks. For this reason, constructivist learning and teaching take place progressively but meaningfully, and they do so at different levels of knowledge; that is, the process is interdisciplinary, and various elements come to play a role. Although constructivist learning and teaching seem to be in different spheres (abstract and concrete), they coherently form the multifaceted construction of knowledge in the classroom (see Table 4).

The inclusion of these layers in the study of language teaching implies a holistic approach in knowledge construction, considering students’ production in different areas such as cognitive contents, learning experiences, and personal explorations. This is the reason a constructivist framework offers such a rich basis for L2 instruction: The entire learning experience (e.g., linguistic and extralinguistic issues alike) is considered here as a practice in which many factors play a role and that results in a complex and compact procedure. Consequently, and in relation to day-to-day classroom implications, practitioners must consider the explicit teaching of other aspects apart from those purely conceptual and linguistic, including procedural and strategic items as well. These strategies will become discipline-specific, and CLIL is the perfect ground where language and discipline meet.

Therefore, constructivist behaviour in teaching a foreign language requires complete involvement from the teacher, who must be the students’ guide and facilitator. At the same time, teachers must supervise learners’ construction processes by means of formative evaluation and assessment. As Kaufman (2004) notes in her analysis of constructivist learning, constructivism justifies not only linguistic development but also academic construction from a critical perspective: “Constructivism is open-ended and allows for ambiguity, flexibility, and innovative thinking” (pp. 310-311).

Pedagogical Implications of Constructivist Concepts: CLIL at the End of the Path

In such a complex educational environment as the one described above, constructivism considers students as active doers in their learning processes, making them competent language users. This idea of competences is the basis of learning in the new European higher education area (EHEA). The new EHEA framework aims to consider the social dimension of learning by promoting competences such as students’ autonomy in the classroom; similarly, constructivism takes these collaborative variables into consideration (Pérez, Soto, Sola, & Serván, 2009).

Today, the constructivism field has abandoned its primary psychological sources in search of more linguistic domains; this theoretical framework has already been considered crucial “in the linguistic investigation of literacy development” (Kaufman, 2004, p. 303). In reality, however, constructivism can be considered both a theory of learning and a theory of knowledge and world perception. The study and learning of a language come as a result of different construction processes that take place in complex environments. From a constructivist standpoint—and to support the most linguistic side of this theory—the development of mental and cognitive processes derives from repeated exposure to language.

Learners’ paths toward meaning construction are based not only upon their social interactions in the classroom but also upon their conceptual knowledge of the discipline they are studying. This academic setting enhances the notion of academic genre that must be present in learners’ outcomes; academic genre features can be taught explicitly, and this genre shift advocates for content specification. Content-focused teaching, without leaving formal aspects aside, is what CLIL can offer.

The most direct outcome of this holistic nature of constructivism is the fact that it does not pursue a single teaching technique. As we will see in the following section, the emergence of constructivism in classroom implementations leads to a post-methodological CLIL in L2 teaching that aims at using eclectic techniques that would significantly depend on learners’ various needs.

An Evolution in L2 Teaching Methods That Mirrors the Linguistic Paradigm Shift

The classical method of foreign language teaching, the so-called grammar-translation method, was eminently mnemonic, with some lexical and grammatical exercises based on repetition and recurrence. These continuous repetitions reinforced a word’s mental image, making its memorization easier but without considering its contextual use. Attention was paid to written over oral language, so that learners never had complete acquisition of Greek and Latin spoken skills because they were already dead languages. The pedagogical tactics in this traditional method were “translation, memorisation of vocabulary lists, and verb conjugation” (Savignon, 2007, p. 208). Therefore, the crucial role of memory in this type of teaching allowed for more mechanical learning rather than deductive or relational.

This traditional focus on forms and recitation continued to be the only foreign language teaching method for centuries. However, a new concept of grammar and grammar teaching was published by monk scholars during the second half of the 17th century, bringing innovative constructivist ideas into the language classroom. Constructivism as a theory of learning is then rooted in the French School of Port Royale, derived from the abbey of the same name (Laborda, 1978).

Nevertheless, this innovative teaching practice was not exported to other schools or universities in a time when foreign languages did not have a crucial role in learners’ curricula. Language teaching followed the classical trend until the beginning of the 20th century, when the World Wars demanded modern and quick ways of learning foreign communication. These historical and political circumstances changed the language teaching panorama, and English became the common international language. During the forties and fifties, Skinner’s behaviourist model put an emphasis on conductive processes in learners’ minds, something that affected the learning of English and its uses in the classroom.

Behaviourist practices in language teaching derived from the structuralist roots of language because structuralism was the basis upon which L1 teaching strategies were drawn during the 1950s and 1960s (Mitchell & Myles, 2004; Myles, 2010). Bloomfield (1983) and Skinner (1957) examined measurable behaviour and responses towards an external stimulus; when applying behaviourism to foreign language teaching, this procedure becomes a simple interaction of repetitions followed by their corresponding rewards.

This behaviourist modification of students’ conduct in the classroom was a teaching trend that aimed to redirect learners’ behaviour to improve their learning. By means of repetitions and linguistic stimuli, teachers could focus on specific patterns and then motivate students towards a specific response to these. At this time, contrastive language analyses between L1 and L2 also helped emphasise the structural character of behaviourism.

Other language learning methods that focused on linguistic forms were the reading method and audiolingualism, in which the key was memorising a series of written items to reach native-like patterns (Richards, 2008). These teaching schemes were the first methods used when the teaching of English as a foreign language (TEFL) was consolidated as a professional practice.

From Teaching Structures to Contextualised and Meaningful Teaching

The focus on linguistic forms and structures led the foreign language teaching panorama until the early 1980s. Krashen (1977, 1978) and his monitor model examined the process of language learning through a series of hypotheses that moved from structural theories towards more affective reasoning. By this time, the field of foreign languages was having greater autonomy and was being constituted as a field of research per se.

As a reactionary movement against behaviourism, a more cognitive model appeared. In this case, mental processes and individual intellectual factors measured the different steps and progress learners made in their learning processes. At the beginning of the 1960s, Chomsky began to criticise Skinner’s behaviourist theories, and consequently there was a shift towards more cognitive aspects of learning. These new ideas influenced the development of language teaching in the following decade: Error analysis and interlanguage shed some light on the way L2 learners produced the languages they were learning. This move towards cognitivism in language teaching took place in two phases that Mitchell and Myles (2004) identify as (1) a procession approach and (2) a more constructionist framework.

After behaviourist and generativist TEFL methods, students no longer practised correct patterns and behaviours; instead, teachers began to look for the construction of particular and contextualised knowledge. Consequently, practitioners had to work with learners who were more actively engaged in their individual learning processes. Generativist and pragmatic trends in language teaching can be compared to the contrast between formalism (Chomsky, Saussure, Bloomfield) and functionalism in language research. In this case, there is a shift from form to function in language study and a direct relationship between students’ cognitive stages in L2 and their pragmatic production and purpose; to measure those cognitive stages, students’ interlanguage provided sufficient information to identify them and therefore grade the activities (and not the text) accordingly (Muñoz-Luna, 2010). This pragmatic or functionalist tradition took into account the nonformal acquisition of L2 structures for the first time, considering it “driven by pragmatic communicative needs” in near-natural situations (Mitchell & Myles, 2004, p. 154); however, learning interaction was still not being contemplated in the functionalist trend.

The importance of pragmatics in L2 teaching dates back to the analysis of speech acts and their communicative consequences in the 1960s (Austin, 2004). However, it was not until recently that pragmatic competence became an explicit part of the English language teaching (ELT) curriculum (Gretsch, 2009; Yu, 2011). This pragmatic skill consists of other sub-competences such as:

• pragmatic awareness.

• metapragmatic awareness.

• metalinguistic fluency (Ifantidou, 2011).

These are needed for the correct interpretation and production of genre-specific texts. In this case, there has also been a methodological evolution within these pragmatic teaching techniques: from reproductive learning (by means of repetitive drills) to constructive learning (through comprehension). Therefore, there has been a change:

• from teaching to transmit knowledge

• to teaching that develops and constructs students’ learning capabilities.

Students are transferring what they have learned to new problems and situations, which genuinely enables them to find solutions and interiorise their learning.

These pragmatic issues fall into the latest post-methodological teaching trend, which does not oppose traditional methods of teaching but rather complements them. Method and post-method will provide a holistic and more real perception of the teaching and learning tasks (Kumaravadivelu, 2001).

This new teaching pedagogy has derived from principles that are against the traditional teaching style, and it includes:

• Creative teaching beyond the traditional transmission model.

• The pursuit of particular aims depending on particular contexts.

• The importance of a theory vs. practice dialogue.

• Learning via shared experiences.

With these pioneering classroom techniques, we leave traditional morphological structures aside and we move on to dialogical and discursive ones, with conversation being the work-unit in the classroom. Regarding the learning of foreign grammatical rules, constructivist teachers attempt to imitate the L1 acquisition process, allowing the student to discover praxis from theory analogically by taking an active role and using inductive exercises (Nagowah & Nagowah, 2009).

These new learning procedures could be defined as negotiating meaning within interaction. The type of knowledge that constructivism promotes looks for the structuration of information, for the conscious application of specific academic techniques, and for the understanding of relationships to make a coherent and more meaningful whole. With regard to meaningful environments, learners’ academic behaviour is placed within a constructivist methodology by which students restructure content and linguistic information according to their previous knowledge of both.

Results of the constructivist methodology are expected to be optimal because it is characterised by the following features:

• The learning process takes place in a meaningful way.

• That learning process departs from what the learner already knows, and it moves towards new concepts from there.

• There is an active effort from the students, who need to be aware of their own learning stages, as well as from the teachers, who will give the necessary guidelines to each learner.

As we can see, the evolution in the field of language teaching is deeply rooted in a focus on form, which gradually turns into a meaning focal point. In turn, meaningful teaching and language interactions move pedagogical attention towards speakers and communication, which undoubtedly need context and purpose. The CLIL frameworks come at this end to provide that discipline-specific context that language learning demands.

Towards a CLIL Pedagogy: Content and Linguistic Purposes Combined in the Academic Genre

The integration of content and form is but the natural inclusion of the role of context in second language teaching. In strongly disciplinary subjects as university ones, the teaching focus should not be solely grammatical, and CLIL does not happen only in language-specific contexts. L2 must be based on specific contents to be contextualised and meaningful. Current teaching practices in university classrooms show that language and content are inseparable when teaching in a foreign language; both are evaluated and mutually influenced.

According to Bell (2003), no language paradigm or teaching methodology has ever been applied holistically to the entire teaching-learning process but rather, only to parts of it (focusing on e.g., students, teachers, physical environment, materials, or syllabus). In a new integrational approach, context, meaning, and communicative competence are key issues because language contexts are perceived as part of the students’ learning backgrounds.

Consequently, we have shifted towards a constructivist state that is beyond traditional methods. This means that both effort and research towards finding the correct methods need to be redirected towards finding necessary strategies and towards awareness of the linguistic target. Without metho-dological restrictions, teachers feel freer to test their own personal techniques in the classroom and see what works for their specific groups; thus, the figure of the teacher-researcher substitutes the former methodological limits in search of a more holistic approach to ELT.

Disciplinary contents, in relation to the foreign language we are working with, may act as the very necessary context in which language acquires meaning. Constructivist methodologies pursue this contextualised practice, which is present in CLIL frameworks. As mentioned above in this paper, the CLIL model most broadly used at university level in Europe is the so-called adjunct model (Brinton et al., 2011), in which students must use their previous language instruction to approach discipline-specific contents. In this way, form and content are not mutually exclusive but coherently integrated. Both are assessed and, therefore, both need explicit attention in class; students’ intrinsic motivation is also essential.

CLIL is triggered by the urgent need to learn foreign languages more quickly efficiently, and also by the use of English as a lingua franca in all research settings, which turns researchers’ attention towards the cognitive and developmental processes of language acquisition (Coyle et al., 2010). CLIL is therefore very relevant to the teaching profession because it offers a wide and complete teaching and learning frame that goes a step beyond traditional programmes. Nevertheless, CLIL implementation requires specific teacher formation and a certain degree of L2 proficiency in students, both conditions that are as yet unfulfilled in Spanish university classrooms (Dafouz, Núñez, & Sancho, 2007).

CLIL is also a good practical realization of holistic and constructivist principles in teaching:

• “There is neither one preferred CLIL model, nor one CLIL methodology. The CLIL approach is flexible in order to take account of a wide range of contexts” (Coyle et al., 2010, p. 48).

• This CLIL contextual flexibility seems highly suitable for constructivist and post-methodological practices.

• CLIL allows for personalizing teaching sessions, encouraging positive attitudes and active engagement in learners.

• CLIL helps develop linguistic strategies and language awareness by means of awareness-raising activities that would focus on linguistic aspects without leaving aside the content of the subject; the juxtaposition of disciplinary and linguistic activities would develop students’ critical thinking.

The importance and usefulness of CLIL courses have been widely demonstrated: comprehension of contents helps aid full acquisition of the vehicular language. Specific language use is considered to be one of the basic elements in a CLIL teacher training course. Discipline-specific language is the means that teachers will work with and that will also evaluated as part of students’ expected knowledge (Coyle et al., 2010).

This content and genre specificity unveils the current debate between LSP and CLIL subjects, which focus on language- and content-specific methodology, respectively. CLIL is the learning approach that refers to the instruction of syllabus contents that are apparently not related to language learning, although a foreign or second language is the language used in the class (Räisänen, 2009). It is mostly employed in language immersion programmes, in which learning a subject requires integration within the practical use of a second language.

The need for contextualisation is inevitable in such a specialised academic arena as higher education. The explicit teaching of genres and their academic features provides students with the necessary tools to carry out authentic tasks in humanities, sciences, and technology. If learners are aware of academic genre features, their written contributions will be more meaningful and directly focused and of better quality. Lorenzo (2010) defines this as a shift from language contents to genre items. In fact, CLIL should go beyond the mere integration of contents and language (Mungra, 2010). If we teach genres and specific academic schemata, we will improve learners’ input processing abilities, thus favouring cognitive thinking beyond context memorisation.

Concluding Remarks

CLIL is the natural and necessary consequence of paradigmatic and pedagogical evolution in foreign language teaching. Initial structuralist approaches to language analysis developed into cognitive theories (e.g., Chomskian generativism) and, later, into pragmatic assumptions. Language forms and structures gave way to constituent formation and then context, placing communicative purposes at the core of language teaching.

From a pedagogical standpoint, drills and repetitions were gradually substituted by meaningful language interactions in which learners had to find and construct their own messages. In such a constructivist environment, the teachers’ task has inevitably expanded; it is now their responsibility to identify students’ needs and learning strategies to provide them with more contextualised and meaningful input. From the learners’ side, they are autonomous, and that means they make use of metacognitive strategies to be able to modify their own learning rhythms.

As we have seen, traditional methods have been disrupted to give way to a more holistic and inclusive CLIL methodology, something that fits into the framework of constructivism. This inclusive perspective is, by definition, eclectic, including multiple methods and interdisciplinary concepts; constructivist standpoints are reflected in post-methodological techniques in the following ways:

• Learning results from a constructivist perspective have proved to be the most advantageous because of students’ implication in the entire process.

• Students work from what they already know to arrive at new concepts.

• Learners are experiencing a more contextualised learning in which language and subject contents are fully integrated.

Recent research programmes are now analysing the effectiveness of content-based language teaching in some European countries (Brinton et al., 2011). The results so far show a great concern for clearly identifying the different competences in education; moreover, they evidence the need for more attention towards affective and motivational aspects (competences) in the curriculum. The complete acquisition of linguistic communicative competence in the L2 includes the mastery of several domains that cover those extra-linguistic issues mentioned above, and CLIL provides a meaningful environment in which to combine linguistic and discipline-specific contexts.

1Today, both language specialists and nonspecialists are carrying out CLIL practices at the university level. In this paper, I am focusing on the evolution of L2 teaching that derives into CLIL frameworks. CLIL is better understood once we examine the changing role of L2 in the classroom.

References

Austin, J. L. (2004). How to do things with words. In J. Rivkin & M. Ryan (Eds.), Literary theory: An anthology (2nd ed., pp. 162-176). London, UK: Blackwell.

Bell, D. M. (2003). Method and post-method: Are they really so incompatible? TESOL Quarterly, 37(2), 325-336.

Bloomfield, L. (1983). An introduction to the study of language. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins.

Brinton, D. M., Snow, M. A., & Wesche, M. (2011). Content-based second language instruction. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Chomsky, N. (1972). Topics in the theory of generative grammar. The Hague, NL: Mouton.

Chomsky, N. (1986). Barriers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1988). Language and problems of knowledge. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1995). The minimalist program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (2000). New horizons in the study of language and mind. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Coll, C., Martín, E., Mauri, T., Miras, M., Onrubia, J., Solé, I., & Zabala, A. (2007). El constructivismo en el aula [Constructivism in the classroom]. Barcelona, ES: Biblioteca de aula.

Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL: Content and language integrated learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Scholars.

Crotty, M. (2003). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. London, UK: Sage.

Dafouz, E., Núñez, B., & Sancho, C. (2007). Analysing stance in a CLIL university context: Non-native speaker use of personal pronouns and modal verbs. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(5), 647-662.

Derrida, J. (1971). De la gramatología [Of grammatology]. México, MX: Siglo XXI.

Gretsch, C. (2009). Pragmatics and integrational linguistics. Language and Communication, 29(4), 328-342.

Guey, C., Cheng, Y., & Shibata, S. (2010). A triarchal instruction model: Integration of principles from behaviourism, cognitivism, and humanism. Procedia: Social and Behavioural Sciences, 9, 105-118.

Ifantidou, E. (2011). Genres and pragmatic competence. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(1), 327-346.

Kaufman, D. (2004). Constructivist issues in language learning and teaching. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 24, 303-319.

Kennedy, C. (2012). ESP projects, English as a global language, and the challenge of change. Ibérica, 24, 43-54.

Krashen, S. (1977). The monitor model of adult second language performance. In M. K. Burt, H. C. Dulay, & M. B. Finocchiaro (Eds.), Viewpoints on English as a second language (pp. 152-161). New York, NY: Regents.

Krashen, S. (1978). Individual variation in the use of the monitor. In W. C. Ritchie (Ed.), Second language acquisition research: Issues and implications (pp. 175-183). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2001). Toward a postmethod pedagogy. TESOL Quarterly, 35(4), 537-560.

Laborda, X. (1978). La gramática de Port-Royal: fuentes, contenido e interpretación. [Grammar of Port-Royal: Sources, contents, and interpretation] (Doctoral dissertation) Universidad de Barcelona, Spain.

Larochelle, M., & Bednarz, N. (1998). Constructivism and education: Beyond epistemological correctness. In M. Larochelle, N. Bednarz, & J. Garrison (Eds.), Constructivism and Education (pp. 3-20). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lasagabaster, D., & Ruiz de Zarobe, Y. (Eds.). (2010). CLIL in Spain: Implementation, results, and teacher training. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Scholars.

Lorenzo, F. (2010). CLIL in Andalusia. In D. Lasagabaster & Y. Ruiz de Zarobe (Eds.), CLIL in Spain: Implementation, results, and teacher training (pp. 2-11). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Scholars.

Mitchell, R., & Myles, F. (2004). Second language learning theories. London, UK: Hodder.

Mungra, P. (2010). Teaching writing of scientific abstracts in English: CLIL methodology in an integrated English and Medicine course. Ibérica, 20, 151-166.

Muñoz-Luna, R. (2010). Interlanguage in undergraduates’ academic English: Preliminary results from written script analysis. Encuentro: Revista de Investigación e Innovación en la Clase de Idiomas, 19, 60-73.

Myles, F. (2010). The development of theories of second language acquisition. Language Teaching, 43(3), 320-332.

Nagowah, L., & Nagowah, S. (2009). A reflection on the dominant learning theories: Behaviourism, cognitivism, and constructivism. International Journal of Learning, 16(2), 279-286.

Pérez, Á., Soto, E., Sola, M., & Serván, M. (2009). Aprender en la universidad. El sentido del cambio en el EEES [Learning at university. Sense of change at the EEES]. Madrid, ES: Akal.

Piaget, J. (1970). Structuralism. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Räisänen, C. (2009). Integrating content and language, in theory in practice: Some reflections. In E. Caridad de Otto & A. F. López de Vergara (Eds.), VIII Congreso Internacional AELFE: Las Lenguas Para Fines Específicos Ante el Reto de la Convergencia Europea (pp. 31-41). La Laguna, ES: Servicio de publicaciones de la Universidad de La Laguna.

Richards, J. C. (2008). Second language teacher education today. RELC, 39(2), 158-177.

Roever, C. (2006). Validation of a web-based test of ESL pragmalinguistics. Language Testing, 23(2), 229-256.

Salaberri, S. (2010). Teacher training programmes for CLIL in Andalusia. In D. Lasagabaster & Y. Ruiz de Zarobe (Eds.), CLIL in Spain: Implementation, results, and teacher training (pp. 140-161). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Scholars.

Savignon, S. J. (2007). Beyond communicative language teaching: What’s ahead? Journal of Pragmatics, 39(1), 207-220.

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Sturrock, J. (1979). Structuralism and since: from Lévi-Strauss to Derrida. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

van Dijk, T. A. (2004). Discourse, ideology, and context. In J. D. Pujante (Ed.), Caminos de la semiótica en la última década del siglo XX [Semiotic ways in the last decade of the 20th century] (pp. 47-77). Valladolid, ES: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Valladolid.

Yu, M. (2011). Learning how to read situations and know what is the right thing to say or do in an L2: A study of socio-cultural competence and language transfer. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(4), 1127-1147.

About the Author

Rosa Muñoz-Luna has a BA in Psychopedagogy (Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca, Spain), an MA in TESOL (University of Exeter, United Kingdom), and a PhD in Applied Linguistics (Universidad de Málaga, Spain) and is a teaching fellow and part of the Applied Languages and Linguistics research group at the Universidad de Málaga. Part of her recent research has focused on the study of teaching methods and their evolution throughout time.