Exploring EFL Pre-Service Teachers’

Experience with Cultural Content and Intercultural Communicative Competence at

Three Colombian Universities

Indagación sobre la experiencia con el contenido

cultural y la competencia comunicativa intercultural de docentes de

inglés en formación, en tres universidades colombianas

Alba Olaya*

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas,

Colombia

Luis Fernando Gómez

Rodríguez**

Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, Colombia

This article

was received on September 24, 2012, and accepted on May 15, 2013.

This article

reports the findings of a qualitative research project that explored

pre-service English teachers’ perceptions of and attitudes toward the

aspects of culture and intercultural competence addressed in their English

classes in the undergraduate programs at three Colombian universities. Findings

reveal that pre-service teachers are mainly taught elements of surface culture

and lack full understanding of intercultural competence. They also see culture as a separate aspect of their future teaching

career. We provide alternatives so that pre-service teachers might overcome

limitations of the teaching of culture as preparation for their future teaching

career in the foreign language classroom.

Key words: Cultural content, deep culture,

intercultural communicative competence, pre-service teachers, surface culture.

Este artículo reporta los hallazgos de una

investigación cualitativa que indagó sobre las percepciones y las

actitudes de los profesores en formación en el área de

inglés respecto a los contenidos culturales y la competencia cultural

que se abordan en las clases de inglés, en tres universidades

colombianas. Los hallazgos revelan que los docentes en formación

primordialmente tratan aspectos de la cultura superficial y no tienen total

claridad de qué es la competencia comunicativa intercultural.

También conciben la cultura como un aspecto desligado de su futura

profesión docente. Se sugieren algunas alternativas para que los profesores

en formación puedan superar las limitaciones de la enseñanza de

la cultura y se preparen para su futura carrera docente en el salón de

inglés como lengua extranjera.

Palabras

clave: competencia comunicativa

intercultural, contenido cultural, cultura profunda, cultura superficial,

docentes en formación.

Introduction

The

development of intercultural communicative competence (ICC) in the English as a

foreign language (EFL) context has become a necessity rather than an option in

our contemporary society. The ongoing process of globalization and the

amalgamation of diverse communities worldwide demand second language learners

and teachers to develop cultural awareness. Hinojosa (2000), Kramsch (2001), Hernández and Samacá

(2006), and Barletta (2009) argue that one of the main missions of foreign

language teaching is not only to prepare students and teacher educators to

learn linguistic structures and to speak another language fluently, but to

instruct them to become aware of cultural boundaries, misunderstandings, and

the way of life of a foreign culture. Genc and Bada (2005) state that language teaching has begun to

recognize that there is an intricate relationship between culture and language,

because teaching language structures without considering the aspects of the

target culture is inadequate. Despite these salient ideas about the inclusion

of culture in the EFL classroom, the teaching of culture and the development of

ICC still require more attention and research, more concretely, in Colombian

EFL education. Therefore, this article explores how EFL pre-service teachers

deal with the fusion of language and culture.

Statement of the Problem

Authors such

as Byram (1997), Lázár

(2003), and Chlopek (2008) assert that one of the

main problems in EFL classrooms is that language teachers often restrict the

inclusion of cultural content in the language classroom. The study of grammar

forms and communicative functions has dominated language syllabi and restricted

learners’ ability to become culturally competent. Taking into account

that the study of the target culture remains an unripe topic in the educational

setting, including Colombia, we, as teacher-researchers, wanted to conduct a

diagnostic research by exploring and identifying what actual perceptions,

knowledge, and attitudes EFL pre-service teachers at three universities in

Bogotá had in regard to the insertion of culture in the English class

and, in this way, detect the level of understanding of ICC they had.

Furthermore, we wanted to inquire about the teaching practices they were given

to develop ICC at the language programs they belonged to. We think that this

diagnostic study, which focuses on EFL pre-service teachers’ actual

voices and opinions, will allow us to determine to what extent culture and ICC

are part of their preparation in the classroom and what methodological

alternatives they should embrace to foster intercultural awareness in a more

conscientious way.

Theoretical Framework

Culture and

intercultural communicative competence are the main theoretical constructs that

guided this exploratory study.

Culture

Sihui (1996) and Prieto (1998) claim that the development of culture is

facilitated through the process of social communication because any set of

behaviors, beliefs, and ideologies are necessarily embraced by the members of a

particular community through language. The inseparable bond between language

and culture leads to observe that English learners must essentially learn

meanings of the target culture, rather than simply studying grammar forms and

communicative functions. The Common European Framework of Reference to

Languages (Council of Europe, 2001) indicates that learners do not simply

communicate, but develop interculturality,

and that linguistic and cultural contents in the classroom contribute to

enhance ICC and create positive attitudes to new cultural experiences.

Robinson (as

cited in Castro, 2007) indicates that many teachers highlight the importance of

“practicing culture” in the classroom rather than trying to define it.

Robinson claims that culture should be viewed from four definitions: the behavioral definition (set of patterns

that are shared and that may be observed in terms of actions and events), the functionalist definition (social rules

governing and explaining events), the cognitive

definition (the knowledge shared by a cultural actor and other actors, and

that helps them to interpret the world), and the symbolic definition (system of symbols used by the individual to

assign meanings to different elements and events).

Despite EFL

teachers’ attempts to incorporate cultural content in their teaching

practices, culture continues being seen from the behavioral definition.

Therefore, it is conceived as a static, accumulated, and classifiable concept

that can be taught and learned with no effort (Paige, Jorstad,

Siaya, Klein, & Colby, 2003). Aspects of culture

such as celebrations, food, tourist places, and important people, which are

classified as elements of surface or observable culture (Hinkel,

1999), seem to be the most common contents discussed in the EFL context. In

this sense, there is a need to address significant aspects of deep culture from

the functionalist, cognitivist, and symbolic levels (as proposed by Robinson,

1988) that are very often omitted, including, for instance, attitudes to life,

personal and collective ideologies, beliefs, and customs that constantly change

through generations. In fact, Trujillo (2002) suggests that culture changes

through time and this endless transformation must be the main object of

interest in the language classroom.

Intercultural Communicative Competence (ICC)

ICC is

defined as the “ability to ensure a shared understanding by people of

different social identities, and [the] ability to interact with people as

complex human beings with multiple identities and their own

individuality”(Byram, Gribkova,

& Starkey, 2002, p. 10). Byram (1997) proposes a

model of ICC composed of three main factors or savoirs: The first factor is knowledge of “social groups and

their products and practices . . . and of the general processes of societal and

individual interaction” (p. 51). The second factor consists of skills: the skill of interpreting, the

skill of relating, and the skill of discovering, which all together help

individuals to learn, explain, and compare the meaning of a given situation or

documents from another culture. The third factor of ICC involves having

positive attitudes such as openness,

empathy, readiness, and curiosity about cultural expressions that may be

similar or quite different from one’s own.

With

knowledge, skills, and attitudes, learners can develop, as proposed by Byram (1997), another savoir

that he calls critical cultural awareness which is the ability to analyze

critically that our own and the target cultures are different and dynamic

because all human beings do not behave and think homogeneously, but act and see

life in varied ways. Byram (1997) claims that critical cultural awareness is “an

ability to evaluate critically and on the basis of explicit criteria perspectives

practices and products in one’s own and other cultures and

countries” (p. 53). In this sense, the intercultural speaker becomes

critical when he/ she “brings to the experiences

of their own and other cultures a rational and explicit standpoint from which

to evaluate” (p. 54).

Similarly,

Banks (2004) argues that the citizens of this globalized society need to

acquire knowledge, skills, and attitudes in order to coexist with other

cultural communities and cultural borders. Banks also affirms that critical

cultural awareness means to support human rights and equality, as well as to

accept the inclusion of minority groups into the mainstream society. This

competence reduces the proliferation of stereotypes, prejudices, and

misrepresentations of others, and allows learners to see the deeper aspects of

culture. These views of ICC become a relevant epistemological notion for those

EFL learners who are preparing to become EFL teachers.

Research Methodology

Research Questions:

Supported by

the previous theoretical framework, our research was led by the following

questions:

What

perceptions, knowledge, and attitudes do EFL pre-service teachers have in

regard to the incorporation of the cultural component in the EFL class?

How might

EFL pre-service teachers foster ICC through the cultural contents studied in

their English class?

Context of the Study

This

research was carried out at three universities in Bogota. Two are state founded

universities while the other one is private. The three universities offer an

undergraduate teaching program—in English or Languages—which

provides teaching and training for those who want to teach English in the EFL

context. Their programs consist of ten semesters and are completed by credit

hours. The programs are composed of different areas of knowledge of which the

field of foreign languages is the most important one in terms of time

distribution, credit hours, and number of subjects. Advanced levels, with which

our study was conducted, took English lessons 6 to 10 hours a week.

Participants

In order to

select the students to participate, we asked the directors of the Language

Departments of each institution to let us develop this study with a group of

fifth semester learners. A total of 51 upper-intermediate EFL students, aged 18

to 22, from the three institutions participated, including both females and

males: 16 students from U11 15 students from

U2, and 20 students from U3. The reason for choosing upper-intermediate

students was that, at this point of their career, they already had enough

background knowledge and experience to give account for the cultural

experiences in their English classes. One of the main features of the

participants is that they are EFL pre-service teachers. Therefore, they are

given professional training to become English teachers. As part of their

preparation, they not only need to have a good English level to teach future

generations, but be knowledgeable about teaching methods and theories related

to culture and ICC, since they need to be qualified to teach in the on-going

era of globalization.

Instruments

For the

study, we selected three data collection instruments: (a) Questionnaires

focused on three core aspects: knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes toward

culture (see Appendix A). Participants answered the

questionnaires individually when we visited each institution. (b) During our

visits, we also used an individual semi-structured interview, which was

recorded on tape, transcribed later and saved in a file. The interview was

conducted in English because we were aware that we were interviewing teacher-educators

and we wanted to expose them to speaking in the target language about their

preparation in terms of the cultural aspects they had been instructed in. The

interviews consisted mainly of four questions: The cultural topics approached

in the English class, students’ preferences for any cultures, opinions

about the importance of culture, and the cultures existing in the classroom.

The questionnaire and the interviews contained open-ended questions because we

wanted to observe participants’ broad range of feelings, thoughts, and

opinions about their experiences with contents of culture; in other words, to

have data from their varied perspectives. (c) We also made a documentary

analysis of the study plans of the programs in which participants were

enrolled. The purpose was to observe whether or not study plans included any

explicit cultural contents in English courses.

Data Analysis

In order to

analyze the data, we followed the grounded approach principles because, instead

of basing our study on a prior hypothesis, we interpreted and found similar

patterns and themes that emerged from the data collected. We did an in-depth

exploration of the data in order to find EFL pre-service teachers’

knowledge, perceptions of, and attitudes toward culture through a color coding

system. Color coding allowed us to establish the frequency and to identify the

similar opinions students had given. After that, we decided to, as Freeman

(1998) suggests, name, group, find relationships, and display data contained in

the questionnaires. Data were displayed in the order participants had answered

each question so that we could identify patterns and relationships (see

Appendix B). We also did the same process separately with

the other two instruments (interviews and study plans).

Later,

through a process of triangulation which consists of analyzing multiple sources

of information or points of view on the phenomenon that is being investigated

(Freeman, 1998), we established relationships with the data collected in the

questionnaires, interviews, and study plans in order to see if salient patterns

appeared among all of them. This triangulation made possible verification that

the data were reliable and consistent since we realized that the same opinions

and patterns were present in the other instruments. We recognize, obviously,

that the study plans did not show evidence of students’ voices, but were

useful to establish relationships as to what extent they incorporated cultural

content and if students knew the information described in them. In the findings

section, we will use the following codes to analyze and interpret data:

questionnaires (Q), interviews (I), participants (P), and University (U). It is

important to say that the units of analysis taken from students’ answers

are verbatim. That is why some of them have grammar mistakes or are in Spanish.

Findings and Discussion

In this

section we will describe and discuss the findings of our research. First, we

will refer to pre-service teachers’ knowledge and perceptions about

culture and ICC. Then, we will explain their perceptions towards cultural

contents, methodologies, and resources used in their classes. Finally, we will

report about their attitude as to what extent they consider culture and ICC

important for their professional teaching career.

Perceptions of Theories on Culture and ICC

Since

participants were pre-service teachers, we wanted to inquire about their

knowledge of culture in the EFL context, involving theories and definitions of

culture and ICC, and the dynamic nature of culture as useful information for

their teaching careers. Data showed that most of them gave a general definition

of culture based on traditional views. They defined it as a set of customs,

habits, identity, beliefs, traditions, and values of a particular community, as

can be seen in the following examples.

Culture...are the several

characteristics that set or define a society. (P4, Q, U3)

Culture is the main characteristics of, of a town, of

a country, of a city [sic]. (P1, I,

U1)

A set of beliefs, behaviors,

thoughts, customs, that are learned and transmitted in a group of people. (P1, Q, U2)

Participants’

answers demonstrated that they seemed to have a static view of culture. Words

like “main characteristics” and “learned and

transmitted” suggest that they think that culture is unquestionably

transmitted without suffering any possible alteration or transformation. None

of the pre-service teachers recognized culture as relative and changeable. This

finding supports Trujillo’s view (2002) that EFL learners and, in

particular, EFL pre-service teachers need to become aware that elements of

surface culture should not be the only contents to study in the classroom.

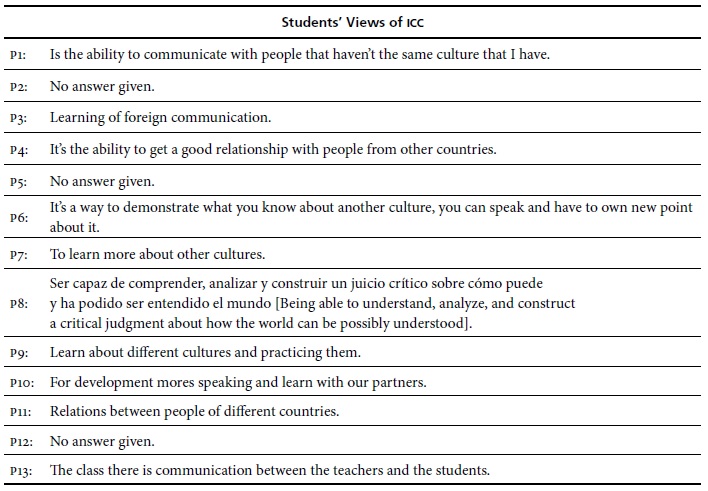

When students

were asked about what ICC was, most of them gave partial definitions. This

supports the fact that students lack knowledge of this competence. For

instance, at U1 only four pre-service teachers defined ICC as ability, others

had a partial or vague view of it, and some others did not provide any answer.

At U2, six participants, out of fifteen, answered that ICC was an ability or

skill, while the other seven did not define the term. Similarly, a few students

from U3 defined ICC better when compared with U1 and U2 students, but most of

them gave an incomplete definition:

Is the ability to interact with other cultures. (P3, Q, U2)

Competence to talk with people from

other places and with other culture. (P15, Q, U3)

Moreover,

students seemed to confuse communicative competence with ICC since they believe

that being able to communicate appropriately with speakers from the target

language is the main priority, as shown in these data samples:

Learning a [sic] foreign communication. (P3, Q, U1)

Yes, I think is important because is the language

which I want to learn. (P1, I, U3)

I can learn English more, I can

learn English easier. (P4, I, U2)

Thus, they

need to be guided to acknowledge the significant role culture and intercultural

awareness play in the process of communication and as part of their training to

become teachers in the future. This finding strongly relates to Byram’s (1997) claim that individuals must attain

certain levels of intercultural understanding in order to develop critical

intercultural awareness with respect to their own country and others since,

according to the participants’ answers; they are more concerned about how

to communicate with speakers of the target culture than to deal appropriately

with their cultural differences.

Figure 1 shows participants’ level of understanding of

ICC at the three universities. Perceptions of ICC show that only a limited

number of pre-service teachers had some general idea about the concept, but

none of them referred concretely to knowledge, skills, or attitudes as

essential components of ICC.

Cultural Contents Reviewed in and Outside of the

English Classroom

Another

aspect we wanted to explore referred to cultural topics they discussed in their

English classroom. All of them mentioned aspects of surface culture, including

history, tourism, arts, entertainment, and food; being history and tourism the

most salient aspects. It is important to note that only 8 participants out of

51 answered that they had discussed “social and historical

aspects.” However, they did not report which social and historical facts

they had studied, and this may imply that they had not internalized or

critically learned those particular facts. Surprisingly, these pre-service

teachers never referred to aspects of deep culture such as relationships,

culture shock, cultural misunderstanding, relations of power, social class,

politeness, discrimination, otherness, attitudes to life, and identity. Data

showed that they are often trained to teach observable and surface elements of

culture. This finding indicates that they still need their teachers’ help

to become aware of the dynamism and transformation of deep elements of culture

because, as data suggest, they learn culture at an informative and superficial

level, rather than from a critical and reflective perspective. As pre-service teachers

they need to be more critically prepared on concepts of culture so that they do

not replicate a superficial approach to culture when assuming a teaching

position in an EFL classroom in the future. As Hernández and Samacá (2006) highlight, learning about culture goes

beyond studying a list of facts about history, music, arts, or geography.

Similarly, it is our understanding that pre-service teachers should address

issues of deep culture as identity, social clash, attitudes, and conflicting

values and beliefs that might differ from their own, but that will empower them

to deal with otherness and complex interaction among individuals from the

target culture. A way to promote this discussion of the foreign culture is

suggested by Álvarez and Bonilla (2009), who

state that learners should be engaged in interactions through a collaborative

and a dialogical process because students should take a critical position about

the target culture, departing from the understanding and analysis of their

culture.

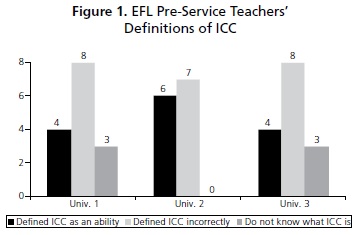

Besides

these topics of surface culture studied in class, pre-service teachers admitted

that they had done research on cultural contents outside the classroom. As they

were asked if they did research on culture, 38 students reported that they had

researched on their own initiative while 12 had not. Figure 2

shows this aspect more specifically at each university.

Additionally,

most students recognized that they had done more research on the Anglophone

cultures than on their own culture, while just a few students had done more

research on their own culture than the target culture. Sixteen participants

from the three universities acknowledged that they had investigated other

cultures different from the Anglophone and their own. Over all, data revealed

that more learners had initiative to do research on the Anglophone cultures

without their teachers’ request. However, most of the topics students

acknowledged having researched included history, beliefs, music, science, art,

literature, and food. These topics confirm the finding that pre-service

teachers mainly focus on aspects of surface culture, since they seem to be

probably influenced by the topics addressed in their language classes. This

fact was clearly evidenced in the data as only few students reported having

researched deep aspects of culture such as impolite behaviors and slang. In

short, the positive finding is that they acknowledged being autonomous when

learning elements of the Anglophone cultures outside the classroom. The

limitation that we identified as analysts of the data is that students need to

be encouraged to research cultures different from the Anglophone ones in order

to create more diverse and inclusive intercultural awareness, since interculturality implies the discussion of different

nations around the world that do not necessarily have to belong to the Anglo-Saxon

civilization. This will allow EFL pre-service teachers in their future teaching

positions to promote an open environment of inclusion and diversity, since they

will surely teach learners from different cultural backgrounds within Colombia.

From the data,

only one pre-service teacher acknowledged that he had researched some elements

of deep culture, such as behaviors, expressions, and accents. On the other

hand, those participants who answered they had never done research on their own

initiative argued that they were not interested in culture, had no time to

investigate, and were not motivated to study that topic. Others did not answer

why they lacked interest. They only said they had never done any type of

research. Some comments related to the question are:

I think I have too many homeworks [sic]

to do and I don’t have time. (P3, Q, U1)

Because I am

not interested on that. (P2, Q, U2)

I think that it’s a lack of self-work and

initiative, a lack of motivation. (P4, Q, U3)

The fact

that several EFL pre-service teachers are not concerned about learning cultural

content on their own indicates that they are not totally aware of the real need

of becoming intercultural in our current society and that they need more

guidance to understand that ICC is not an innate ability, but one that is

acquired and taught through conscious instruction. In this sense, those

teachers who instruct pre-service teachers need to address the study of

cultural content more purposely in their classes so that pre-service teachers

do more research and discuss this topic more often in order to become better

intercultural English speakers and more qualified EFL teachers.

One

interesting perception articulated by one pre-service teacher regarding the

reasons for doing research on his own is:

I think is important to know how the others had acted

and why they had done know and understand the other can help us growing like

people and as teachers we would need it [sic].

(P8, Q, U1)

This

participant and another from U2 recognized that their interest in learning

cultural content is because they think it is an important aspect for their

future teaching career. The other 49 participants at the three universities

said that they had initiative to learn about culture because they were planning

to travel abroad and because they were just interested in learning this kind of

information. Some of their opinions are:

I think it’s important because maybe we will

travel. (P2, I, U2)

Because if I want to travel to some other

place, I have to know about that culture. (P12, Q, U1)

Because I like to learn more about countries I’m

studying. (P4, Q, U3)

What people do there and what we do here and maybe the

places where we can go. (P6, I, U2)

Participants’

answers indicate that they still need to be instructed by their teachers to see

culture not only as a tool to meet their traveling and tourists’

interests, but to be prepared to become English teachers in the future, since

the language programs in which they are enrolled aim at preparing qualified

teachers in the Colombian context. At this point we were able to establish a

significant correlation: since most participants see culture as informative and

at a surface level, which will allow them to travel as tourists and to

communicate when traveling, they still need to become more aware of culture at

a deeper level.

As a

conclusion, participants seem not to be familiar with the distinction of

surface and deep levels of culture because they have not been trained to

recognize those levels. As a consequence, with their teachers’

assistance, pre-service teachers are called upon to become more aware of ICC

and consider more mindful reasons to see the study of culture in the EFL

classroom, not only for traveling plans, but also for their role as future

English teachers and citizens of a multicultural world. This finding leads us

to reflect on what Quintero (2006) points out: that an intercultural person is

one rooted in his/her own culture but, at the same time, open to the world; a

person who observes the unknown from the known, and who interacts with

otherness from his/her own affirmation and self-assessment, that is to say, one

who becomes critical of the globalized world around him/her.

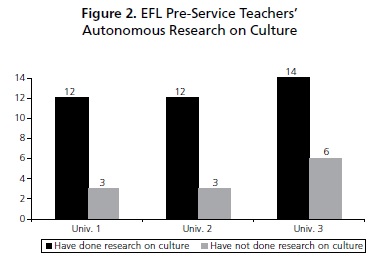

Additionally,

data gave us interesting insights as to which topics participants would like to

study regarding culture. Some of them said that they would like to study features

of deep culture (without being aware that those aspects belonged to deep

culture), including behaviors, accents, the culture of U.S. Native-American

Indians, body language, educational systems, and politeness. However, the

majority stated that they would like to study aspects such as historical facts,

food, landmarks, “special days,” the arts, important people, and traditions

in general. These responses support once more the fact that pre-service

teachers’ perceptions about culture rely on the surface level of culture,

and that they have not become aware of deeper aspects. History seems to be the

most required aspect they would like to study, but they see history as an

opportunity to learn factual information from the past, but do not reflect how

historical events have caused cultural conflicts, resistance, and social

differences. Figure 3 presents the level of surface and

deep culture that students would like to learn in the English classroom.

Consequently,

data revealed that students need to apply different manifestations and

expressions of deep culture (attitudes to life, gender, race, social classes,

prejudices, how people act in certain circumstances, ideologies, individuality,

etc.) so that they will be able to foster ICC more appropriately. This can be

connected to Nieto’s (2002) concern that these deep cultural aspects are

manifestations of economic, political, and social power that should be

discussed to promote critical intercultural awareness in the classroom.

Importance of Incorporating Culture in the EFL

Classroom

According to

the participants, it is important to incorporate culture in the English

classroom because it is related to language. Twenty students, out of 51, established

a relationship between culture and language:

Because the English Language is part of the culture

and it is important to know cultural aspects! (P3, Q, U2)

It is important, every language [is part of a]

culture, so if we study about [culture] we can understand the language much

better. (P7, Q, U1)

Because learning a foreign language

implies learning the culture, too. (P10, I, U3)

These

opinions reveal that almost half of the participants from the three

universities think that language is a medium through which to acquire culture.

They perceived culture as an essential element to negotiate meaning in real

social situations of life. This finding contrasts with the notion of surface culture

that most of them have. At least half of the participants identified the link

between language and culture as dynamic in actual cross-cultural interaction,

but it does not mean that they are aware of this cultural feature as dynamic.

Also, because only less than half made this connection, the other half needs to

see culture as a powerful agent when speakers from diverse backgrounds engage

in the process of communication. Some of their answers indicate that including

culture in the ELF classroom is just for the sake of learning language and

gaining general knowledge of a culture, but they do not see it as determinant

component in authentic communicative practices, as these samples suggest:

Is very important because of this

why I can know about other cultures and other aspect from other countries in

the world [sic]. (P2, Q, U1)

I think it is quite important because, because the

cultural component improves the process of learning languages. (P7, I, U2)

Because it is a good way to improve

our knowledge. (P4, Q, U3)

These views

emphasize that English teachers should become foreign culture teachers, having

the ability to teach learners to experience and analyze the home and target

cultures through communicative language practices in the classroom, rather than

in informative terms.

Another

important finding in the data was that only five out of 51 participants thought

culture would help them to become more qualified English teachers in the

future:

Because it is important knowing other

cultures for our self-development like teachers. (P5, Q, U3)

Because first, I’m going to be a teacher,

I’m going to teach this. (P6, Q, U1)

As a teacher we have to know different cultures to

teach the other, to teach to the kids. (P3, I, U2)

We might

observe, then, that teacher educators need to instruct pre-service teachers to

consider cautiously to what extent the aspect of culture is a crucial element

to qualify their teaching career, since they have not thought about this point

yet.

Pre-Service Teachers’ Preferences About Cultures to Be Studied

When

students were asked if they were more inclined to learn about a specific English

culture over another, most of them said they were. Twenty-four participants

tend to study one Anglophone culture over the other:

Yes, I studied the cultures and the food. The United States and British. (P7, I, U2)

I would like to know more about British culture than

American culture. (P12, Q, U3)

Inglaterra ya que es

un idioma, más limpio que el norteamericano [I prefer

British English because it is a cleaner language than the American one]. (P2,

Q, U3)

Opinions

show that EFL pre-service teachers are sometimes biased about cultural groups

as they did not explain why they preferred one culture over another.

Learners’ predisposed and simplified views seem to be the result of their

lack of solid ICC. In this sense, English teachers are called upon to help

students to become more critical in regard to preconceptions of certain

cultural groups. Pre-service teachers need more guidelines to understand that,

for instance, there is not a “better” and “cleaner”

English accent. On the contrary, all cultures and languages are different and

unique, and English variations, from the perspective of lingua franca,2

can never be categorized as “cleaner” or “better,”

because English is a universal language that not only functions as a means for

individuals to communicate worldwide, but has different variations and accents.

English is one of the most popular languages that has

facilitated intercultural encounters regardless of notions of language purity

and appropriate use. Over all, this finding from data suggests that pre-service

teachers still need to create more positive attitudes to respect and value

differences, rather than excluding them just because they have stereotypes and

reductionist labels on them.

Another

relevant finding from data is that pre-service teachers do not have clear

opinions about the people and lifestyles of other cultures. Most of them only

made generalizations and stated ambiguous opinions of foreign people. Views

such as: “American people are more businessmen than Colombian

people” (P4, Q, U1) and “I know that they have a lot of different

aspects of us but I do not know any specific point” (P7, I, U2)

demonstrate that their opinions are hedged on general stereotypes or that they

simply do not know about deep attitudes, particular characteristics, or

cultural behavior of the foreign culture. This information is significant in this

study because it shows again that students have mostly focused on the study of

language forms and on the surface level of cultural aspects and have not

completely envisioned, with their teachers’ help, deep aspects in regard

to complex social relationships. Stereotypes and unawareness of the people of

the target culture lead us to conclude that EFL pre-service teachers still

require developing more conscientious ICC. They must become critical thinkers

who are able to interpret, compare, and discover—skills proposed by Byram (1997)—intricate meanings of the target and

their own culture.

When

pre-service teachers were asked which characteristics a person should have in

order to become aware of cultural aspects, they recognized that an

intercultural person requires having tolerance, openness, respect, patience,

and curiosity. Nonetheless, 16 participants from the three universities did not

answer this question. Similarly, when being asked if they thought they had the

characteristics they had mentioned in the previous question, 44 students were

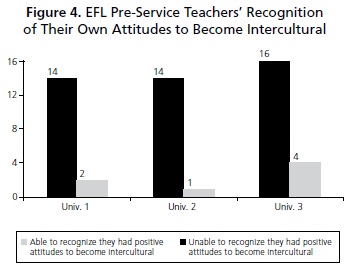

unable to answer this question (see Figure 4).

Data showed

that although participants listed positive attitudes, they found it difficult

to recognize they held them. It seems to be that pre-service teachers need to

build those positive attitudes, as suggested by Byram

(1997), in order to develop ICC and to be more convinced that they can be

capable of adopting them as part of their qualification to become EFL teachers.

In fact, Byram has stated that any person can become

intercultural, but it requires effort, preparation, and awareness.

Methodologies and Resources Used to Teach and Learn

Culture

The most

common methodology used at both U1 and U3 when discussing culture is

students’ presentations, while at U2 teachers’ presentations are a

salient method. This might indicate that U2 follows a more teacher-centered

approach than U1 and U3, where teachers’ presentations are less frequent.

In this direction, U1 implements teachers’ presentations in a lesser

degree, while U3 students reported that teachers’ presentations are

sporadic, since pre-service teacher education students have to do research on

cultural issues and give their own presentations as part of their preparation

to become English teachers.

In regard to

home videos, U3 participants acknowledged that they often used this kind of

methodology. U1 students sometimes use home videos, while U2 students rarely

use them to learn culture. Role-plays are more used at U2 than in the other two

universities, but the students at the three universities said that they have

sometimes role-played situations related to cultural content. In conclusion, the

most common instructional activity to study culture is through students’

oral presentations.

Students at

the three universities (33 participants out of 51) reported that videos and

movies are the most used resources to study culture in class. However, they did

not give concrete examples of those visual materials. Listening activities rank

the second place. Contrary to what many might think, the Internet was not

recognized as a significant resource in the language classroom. Only seven EFL

education students, out of the 51 mentioned, said they used the Internet as an

effective way to learn culture. Nonetheless, they did not say if they often

used the Internet as an extra class resource to research content for their

presentations. It seems to be that they use the Internet to prepare their presentations

outside the classroom, but it is not often used as a class activity to learn

cultural content.

A third

resource that participants valued is reading materials, including books,

articles, and magazines. Data showed that U2 students have more access to

reading material than U1 and U3 students. This information may be consistent

with the methodologies used at U1 and U3 where teaching culture is mainly based

on students’ presentations. Results indicate that U1 and U3 teachers

still need to encourage learners to read books, documents, and stories as ideal

resources to acquire cultural content in order to complement the oral

presentations they already have as a methodology.

Moreover,

EFL students of pre-service education were very critical about how culture

should be taught in the English class. Essentially, they would like to have

more involvement and more experiential learning. Their answers mostly depended

on the methodology used at each university. U2 students would like to have more

presentations and discussions through which they can compare and contrast

cultural groups. Since U2 students reported that teachers mostly give

presentations, they would like to participate more in class discussions. U1

students asserted that they would like to have a “more reflective,”

“deeper,” and “critical” analysis of cultural content.

They would also like to do research and read books, and if possible, to talk to

and meet native speakers. Some U3 students recognized that the current ways

through which they learn culture are good. However, they would like to have

options different from oral presentations. They suggested the use of real life

situations, reading short stories, and chatting with native people online.

In brief,

participants’ answers from the three universities still demand more

significant methodologies which could involve them in a more critical and

experiential way focused on more meaningful student-centered approaches.

Interestingly enough, students also mentioned that classes should reduce the

great emphasis on grammar and include more cultural content.

Students’

opinions seem to relate to what we observed in the study plans from the three

universities. At U1, the study plan includes six semesters of English courses

in which the cultural component is not evident. It is the teacher’s

decision whether he/she includes any cultural issues to be discussed. However, there

are three courses that address “society” of the foreign language.

Similarly, at U2, all the English courses from first to ninth semesters focus

on the development of language proficiency, but there are four courses that

include cultural components: Language and Communication (fourth sem.);

Language, Society, and Culture (sixth sem.); and Literature in English 1 and 2

(eighth and ninth sem.). By contrast, U3 devotes six courses named

“Anglophone Languages and Cultures.” However, the courses focus on

elements of the surface culture, and this superficiality supports the fact that

the teaching of culture in the EFL context, as claimed by Byram

(1997) and Hinkel (1999), lacks a deeper perspective.

In addition, there are two courses oriented towards one aspect of culture:

English literature in seventh and eighth semesters in which the study of

literary works and authors is addressed. There are four more courses called

Emphasis and Competences Development which in some cases may be oriented

towards the study of culture, but it also depends on the teacher’s

decision when he/she is assigned the course. The description of the study plans

may indicate, when relating them to students’ answers, that teacher and

students are making a great effort to include culture, but, in general, it is

mainly oriented to language study because the study plans neither describe nor

contain cultural aspects to be studied. They only stress the importance of

developing communicative competence through language forms and communicative functions.

The findings

summarized in this section invite us to reflect upon the importance of

including this core component in the teaching of English. In order to reach this

aim, there is a need to re-shape the fundamentals of the EFL context: the institution’s

study plans, the teacher’s conceptions of culture and ICC, the syllabus,

the methodologies, the resources and activities. For instance, institutions can

make the ICC component more visible in their study plans and programs so that

its inclusion does not depend on a teacher’s decision. Similarly,

teachers can replicate effective ICC experiences from their colleagues such as

the one presented by Agudelo (2007) where he

encouraged his students to explore and analyze the relationship between language

and culture and its role in the field of language teaching through the use of

critical pedagogy, and by addressing issues of cultural and linguistic

diversity and intercultural communication.

In addition,

teachers can implement strategies as the ones mentioned by Fleet (2006) in

order to teach culture: Saying in our own words what we have read or heard,

doing research on cultural issues, sharing different culture views,

personalizing cultural contents, discussing cultural misunderstandings, and

giving presentations on lifestyles and different ideologies, among others. We

can use authentic materials as the ones described by Peterson and Bronwyn

(2003): films, news broadcasts, and television shows; websites; photographs,

magazines, newspapers, restaurant menus, travel brochures, and other printed

materials. An example of deep cultural contexts is proposed by Álvarez and Bonilla (2009), who engaged students in

ethnographic work about subcultures (vegetarians, body builders, and gays) in

order to examine and understand diverse groups that deviate from traditional

representations of homogeneous culture.

We

personally suggest discussing literary works, studying history critically

rather than informatively, and addressing conflicting and debatable topics

about discrimination, xenophobia, homophobia, race, gender roles, hatred, human

rights, relations of power, politeness, social differences, consumer societies,

the working class conditions, the world economy, and the growth of

globalization, among others. These topics are not only realistic, but provide

learners with the capacity to become reflective and critical about how people

from other cultures as well as their own see these topics, and how those issues

might favor or affect the relationships among the diverse cultural groups

around the world and within learners’ own cultural backgrounds.

Conclusions and Implications

Based on the

three research questions, findings lead us to address the following

conclusions:

1. The

development of this study helped us envision mainly two assets of English-language

programs so far: (a) Raising students’ awareness on the importance of

cultural topics and their relationship to language. (b) Helping students become

autonomous and interested in learning about cultural topics.

2. Although

cultural content has become part of the language classroom, there must be a significant

change by including both elements of surface and deep culture, since the latter

is poorly studied in the classroom. For the particular professional necessities

of students involved in pre-service teacher education, they need more

instruction on how to teach elements of surface and deep culture in the EFL

context.

3. Pre-service

teachers need further preparation to compare and interpret cultural content.

Rather than just being understanding, they should become more critical about

issues of otherness, power relationships, ideologies, and identity. Since this

kind of learners already possesses an appropriate language level, critical and

interpretative processes might possibly be achieved if teachers incorporate

aspects of deep culture. This change will allow pre-service teachers to become more

critical intercultural learners.

4. Students

involved in teacher education are still influenced by stereotypes and

misconceptions of other cultural groups. This might be caused because the

teaching practices are primarily oriented to the study of superficial culture.

Teachers are called upon to find alternatives so that they help prospective EFL

teachers to reduce false misrepresentations of other people through more

pertinent materials in which cultural conflicts, behaviors, and ideologies can

be discussed.

5. Although

prospective teachers of English in Colombia seem to have a positive attitude

towards culture, there is a great necessity to help them to create stronger

personal attitudes to become intercultural as regards tolerance, curiosity,

readiness, and openness, since they are not totally convinced of having those

attitudes and, in most cases, do not recognize they have them.

6. It

is the responsibility of teacher education programs at the three universities

where the study was conducted to get prospective English teachers aware that

studying culture implies more than just gaining information in a received way

or from a tourist’s perspective. As future educators, they must see

culture as part of their teaching career so that they are able to instruct

their students on ICC and, if possible, contribute to the process of helping

others to face the current process of globalization. Therefore, in regard to

the first research question, pre-service teachers’ perceptions of and

attitude toward cultural content need to be strengthened along their teaching

training so that they might become more prepared EFL teachers.

7. With

respect to the second research question, University teachers should start to

train pre-service teachers in Colombia to become more aware of ICC theories.

ICC can be fostered among pre-service teachers not only through the study of

contents and the development of class activities about culture, but with

theories of what ICC is as they are involved in epistemological discussions

about English teaching methods and theories in order to become better qualified

teachers in the Colombian context and competent intercultural beings in this

globalized world.

It is

important to say that the teaching of culture is best approached by creating an

open and tolerant atmosphere within the school and classroom community itself

(Fleet, 2006), where members surely come from diverse backgrounds of their own

country. Pre-service teachers in particular must value and appreciate their own

national differences to later appreciate foreign groups. Not only celebrating

cultures of all types, but establishing critical views can empower pre-service

teachers to develop critical ICC so that they will be able to accept all

students in the EFL classroom regardless of race, color, social class, age,

sexual orientation, educational level, and ideology. Language should be a means

to learn about all the cultures and subcultures of the world. As found in this

research, pre-service teachers and learners belonging to Language Programs at

several universities in the EFL context still need more preparation,

methodologies, themes, and positive attitudes to become better intercultural

interpreters of diversity and stronger advocators for inclusion and difference.

1 U1, U2, and U3 stand for the three universities where

the study was conducted.

2 A language used to make communication possible among

speakers who do not share a mother tongue, in particular when it is a foreign

language, distinct from speakers’ mother tongues.

References

Agudelo, J. J.

(2007). An intercultural approach for language teaching: Developing critical

cultural awareness. Íkala, Revista de

Lenguaje y Cultura, 12(18),

185-217.

Álvarez,

J. A., & Bonilla, X. (2009). Addressing culture in the EFL

classroom: A dialogic proposal. PROFILE Issues

in Teachers’ Professional Development, 11(2), 151-170.

Banks, J. A. (2004). Introduction:

Democratic citizenship education in multicultural societies. In A. J. Banks

(Ed.), Diversity and citizenship

education: Global perspectives (pp. 3-15). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Barletta, N. (2009). Intercultural

competence: Another challenge. PROFILE

Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 11, 143-158.

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative

competence. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M., Gribkova, B., & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the intercultural

dimension in language teaching: A practical introduction for teachers [PDF

Version]. Retrieved from http://www.lrc.cornell.edu/director/intercultural.pdf

Castro, D. (2007). Inquiring into culture in our foreign-language classrooms. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 9,

200-212.

Chlopek, Z. (2008).

The intercultural approach to EFL teaching and learning.

English Teaching Forum,

4, 10-27.

Council of

Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for

languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Freeman, D. (1998). Doing teacher research: From inquiry to

understanding. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Fleet, M. (2006). The role of culture in second or foreign language

teaching: Moving beyond the classroom experience. Retrieved

from ERIC database. (ED491716)

Genc, B., & Bada, E. (2005). Culture in

language learning and teaching. The

Reading Matrix, 5(1), 73-84. Retrieved from http://www.readingmatrix.com/articles/genc_bada/article.pdf

Hernández,

O., & Samacá, Y. (2006). A study of EFL students’ interpretations of cultural aspects

in foreign language learning. Colombian

Applied Linguistic Journal, 8, 38-52.

Hinkel, E. (Ed.). (1999). Culture in second

language teaching and learning. New York, NY: Cambridge University

Press.

Hinojosa, J. (2000). Culture and

English language teaching: An intercultural approach. Cuadernos de Bilingüismo, 1, 107-114.

Kramsch, C. (2001).

Context and culture in

language teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Lázár, I. (2003).

Incorporating

intercultural communicative competence in language teaching education.

Strasbourg, FR: Council of Europe Publishing.

Nieto, S.

(2002). Language culture and teaching: Critical

perspectives for a new century. London, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Paige, R.

M., Jorstad, H., Siaya, L.,

Klein, F., & Colby, J. (2003). Culture learning in language

education: A review of the literature. In R. M. Paige, D. L. Lange, & Y. A.

Yershova (Eds.), Culture

as the core: Integrating culture into the language curriculum (pp. 47-113).

Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

Peterson,

E., & Bronwyn, C. (2003). Culture in second language

teaching. ERIC Digest. Retrieved

from http://www.cal.org/resources/digest/digest_pdfs/0309

peterson.pdf

Prieto,

F. (1998). Cultura y comunicación

[Culture and communication]. México, MX:

Ediciones Coyoacán.

Quintero,

J. (2006). Contextos culturales en el aula de inglés [Cultural contexts in the English classroom]. Íkala, Revista

de Lenguaje y Cultura, 11(1), 151-177.

Robinson,

G. L. (1988). Cross-cultural understanding. New York, NY: Prentice Hall.

Sihui, M. (1996). Interfacing

language and literature: with special reference to the teaching of British

cultural studies. In R. Carter, & J. McRae (Eds.).

Language, literature, and the learner:

Creative classroom practice (pp. 166-184). London, UK: Longman.

Trujillo, F.

(2002). Towards interculturality through language teaching: Argumentative

discourse. CAUCE, Revista de Filología y su Didáctica, 25,

103-119.

About the Authors

Alba Olaya holds a BA

Degree in Spanish and Modern Languages from Universidad Pedagógica

Nacional (UPN, Colombia), and an MA in Applied

Linguistics from Universidad Distrital Francisco

José de Caldas (Colombia). She is a member of the research group

Hypermedia, Testing, and Teaching English at UPN, and a full time teacher at

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de

Caldas. Her research interests are ICTs and interculturality.

Luis Fernando Gómez Rodríguez holds a BA Degree in

English and Spanish from Universidad Pedagógica

Nacional (Colombia), an MA in Education from Carthage

College, USA, and a PhD in English Studies from Illinois State University, USA.

He is a member of the research group Hypermedia, Testing, and Teaching English,

and a full time teacher at UPN. His research interests are interculturality

and the teaching of literature in EFL.

Answer the

following questions about the incorporation of cultural content in the English

classroom. Feel free to answer in English or Spanish. Be honest with your

answers. They will only be used for academic or research purposes. Your

identity will be confidential.

Section I

1. Do you

consider that the cultural component has been incorporated to the syllabus of

your English class?

Yes:___ No:___

2. Give

a short definition of the following terms:

Culture:_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Intercultural

communicative competence:_____________________________________________________________________________

3. If

your answer to Question 1 is Yes, tick the cultures

that have been discussed in your English class.

a. your own

culture ☐

b. Anglophone

cultures ☐

c. other

cultures ☐

4. If

your answer to Question 1 is Yes, which cultural

aspects have been discussed in your English class? (e.g.,

historical aspects, social aspects, tourism, etc.).

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

5. Have you

done research about cultural aspects of other countries by your own initiative?

Yes:___ No:___

Why___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Why not?_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

6. Which

aspects have you taken into account?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

7. What

kind of cultural knowledge would you like to study in your English class?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Section II

1. Do

you think it is important to incorporate the cultural component in your English

class? Why? Why not?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. Do you feel

more inclined to learn about a specific English-speaking culture over another?

Why?__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Why not?_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Which ones?____________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. What

ideas/opinions do you have about the people and lifestyles of other cultures?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

4. Do

you think you have changed your opinion/ attitude about the cultures based on something

you learned in your English class?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

5. What

qualities should a person have in order to become aware of cultural aspects? Do

you have any of them?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Section III

1. Which

methodology has been implemented in order to get to know the English-speaking/

Anglophone cultures? Tick the one(s) that apply.

a.

Presentations given by students ☐

b.

Presentations given by the teacher ☐

c.

Home-videos made by students ☐

d.

Role-plays ☐

e. Simulated

TV/radio programs/interviews ☐

Other____________________________________

Please, specify:

________________________________________________________

2. What

kind of resources/materials has been used in your English class to study

cultural content?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. How

do you think the cultural component should be approached in your English

classes?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Appendix B:

Sample of Displayed Data from Questionnaires

Students’ Answers from University 2

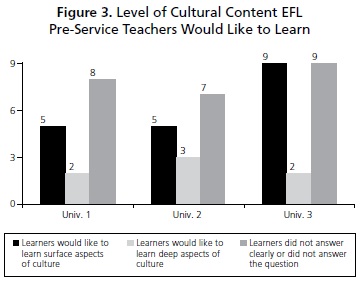

Section I: Question 2