Beliefs of Chilean University English Teachers: Uncovering Their Role in

the Teaching and Learning Process1

Creencias

de profesores universitarios de inglés: descubriendo su papel en el

proceso de enseñanza y aprendizaje

Claudio

Díaz Larenas*

Paola

Alarcón Hernández**

Andrea

Vásquez Neira***

Boris

Pradel Suárez****

Universidad de

Concepción, Chile

Mabel

Ortiz Navarrete*****

Universidad

Católica de la Santísima Concepción, Chile

****bpradel@udec.cl

*****mortiz@ucsc.cl

This article was received on August 16, 2012, and

accepted on March 1, 2013.

Beliefs continue to be an important source to get to

know teachers’ thinking processes and pedagogical decisions. Research in

teachers’ beliefs has traditionally come from English-speaking contexts;

however, a great deal of scientific work has been written lately in Brazil,

Mexico, Colombia, and Argentina. This study elicits 30 Chilean university

teachers’ beliefs about their own role in the teaching and learning of

English in university environments. Through a qualitative research design, the

data collected from interviews and journals were analyzed, triangulated, and

categorized based on semantic content analysis. Results of the study indicate

that university teachers reveal challenging and complex views about what it is

like to teach English as a foreign language in a university context in Chile.

The article concludes with a call to reflect on the importance of beliefs unravelling in teacher education programmes.

Key words: Learning,

teachers’ beliefs, teaching of English, university level.

Las creencias

continúan siendo una fuente de importancia para conocer los procesos de

pensamiento y los estilos pedagógicos de los docentes. Los estudios

sobre las creencias docentes provienen en su mayoría de contextos

angloparlantes; sin embargo, en los últimos años se ha escrito

una gran cantidad de trabajos científicos en Brasil, México,

Colombia y Argentina. Este estudio recoge las creencias de treinta docentes

universitarios chilenos sobre su papel en la enseñanza y aprendizaje del

inglés en ambientes universitarios. A partir de un diseño de

investigación cualitativo, los datos recolectados por medio de

entrevistas y diarios personales fueron analizados, triangulados y

categorizados según el análisis de contenido semántico.

Los resultados indicaron que los docentes de educación superior tienen

visiones desafiantes y complejas sobre lo que significa enseñar

inglés como lengua extranjera en un contexto universitario en Chile. El

artículo concluye con una invitación a reflexionar sobre la importancia

de transparentar las creencias en los programas de formación inicial

docente.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje,

creencias de docentes, enseñanza del inglés, universidad.

Introduction

This research is based on the assumption that beliefs

directly affect the teaching practice and the potential success or failure of

the teaching and learning process (Borg, 2003; Kalaja

& Barcelos, 2003; Pajares,

1992; Woods, 1996). In particular, it considers factors that, both directly and

indirectly, influence the process of teaching a foreign language, besides the

fact that the teaching practice itself can rightfully be addressed from the

perspective of the cognition of a university teacher. In this context, the

concept of “beliefs” includes all mental, emotional, and reflexive

constructs that derive from personal experiences, prejudices, judgments, ideas,

and intentions (Barcelos & Kalaja,

2011). This study aims at identifying university teachers’ beliefs about

their own role in the teaching and learning of English in university

environments.

Conceptual

Framework

Although there are various international

bibliographical references regarding general pedagogical beliefs about the

teaching and learning process of teachers (Borg, 2003), there is little

research in this area in Chile, despite the several contributions from other

Latin American countries. Consequently, this study addresses the beliefs of a

group of 30 university English teachers about their own role in the teaching

and learning process at a university level.

In general, beliefs are defined as understandings,

premises, or psychological propositions an individual has about the world

(Kane, Sandretto, & Heath, 2002). Beliefs consist

of sets of integrated and generally contradictory and messy ideas that are

generated from everyday experiences. According to Díaz

and Solar (2011), beliefs are incomplete and simplified versions of reality

that have some level of internal organization, structure and consistency.

Through the study of beliefs, the frames of reference

by which teachers perceive and process information, analyze, give meaning, and focus

their educational performance are made explicit. Thus, studying the beliefs

teachers have involves exploring the hidden side of teaching (Díaz, Martínez, Roa, & Sanhueza, 2010). In

the scope of this study, beliefs are understood as individual ways a teacher

understands the students, the nature of the learning process, the classroom,

the teacher’s role in the classroom, and the pedagogical objectives (Northcote, 2009).

Freeman (2002) supports the importance of reflecting

on beliefs because this may lead to a number of advantages, such as revealing

the conscious thinking behind certain actions; it may make teachers choose to

teach differently from the way they were taught or want to expand their

techniques and practices; it can confirm the positive things that teachers do

in the classroom or make teachers reflect on their somewhat negative teaching

practices. Borg (2009) and Borg and Al-Busaidi (2012)

affirm that beliefs can certainly influence classroom practices, but classroom

practices can also trigger the shaping of new beliefs.

Stenberg (2011) states that major changes in the

quality of university education will not occur if the beliefs that university

teachers have about teaching itself do not change. Beliefs vary in intensity

and type, and over time, form a system. The ease with which teachers change

their beliefs is related to the intensity of those beliefs. The more intense

the belief is, the greater the resistance to change it. To reinforce this idea,

several authors argue that teachers’ beliefs are rooted in their personal

experiences and are therefore highly resistant to change (Farrell, 2006; Kasoutas & Malamitsa, 2009;

Richards & Lockhart, 1996).

There is no denying the importance beliefs have in

education in general; however, the obvious relationship between beliefs and

teaching practices cannot be ignored. Tudor (2001) highlights the importance of

researching beliefs university teachers have as a way of emphasizing the

important role they play in the teaching practice. Brown and Frazier (2001)

argue that teachers should be treated as active learners who build their own

understandings. Humans are agents that interact in their environment with a

purpose and learn from their actions and use this knowledge to plan future

actions (Levin, 2001). If teachers feel the need to improve their teaching

practice, to reflect on it and to look for alternative teaching strategies, it

indicates an improvement in their teaching practices is near. However, for this

change to be effective and permanent, this process should take place at an

early stage in order to renovate those deep-rooted and ineffective pedagogical

behaviors and criteria.

On the other hand, it is interesting to quote Gross

(2009), who argues that important possibilities exist for change, development,

and enrichment, and even conceptual changes toward epistemological positions

that could be considered more complex and richer in the teaching projection in

a more flexible and multi-perspective way. From this point of view, Brown and

Frazier (2001) raise the importance of researching the thoughts and decision

making of teachers, the nature and content of these thoughts, how these

thoughts are influenced by the organizational and curricular context in which

teachers work, how the thoughts teachers have relate to their classroom behaviour, and ultimately, to students’ thoughts and behaviours. All of this would enhance the level of

understanding of instructional processes that occur within the classroom and

the consequent improvement of the teaching practice.

The beliefs English teachers have are very closely

related to the didactic approach that dominates the discourse of the

participants interviewed for this study. That is to say, either a communicative

or traditional teaching approach greatly influenced the participants’

beliefs about their role as teachers in the classroom (i.e. the role teachers

have can be seen as the person in charge of transmitting knowledge or

facilitating the learning process).

Research

Design

This is a non-experimental and transectional

study based on an analytical and interpretive case study (Bisquerra,

2009), as it explores the beliefs 30 university English teachers have about

their own role and functions in the process of learning and teaching English as

a foreign language in higher education at two Chilean universities. In a case

study, data and analysis are deeply and thoroughly examined, and become

relevant inasmuch as the readers contextualize them to their own

psycho-pedagogical reality.

Participants

The 30 participants of this research make up a

non-probabilistic and intentional sample (Corbetta,

2003) where, taking into account specific characteristics, subjects were

selected one by one. In the case of this current study the participants should

be university teachers who teach English as a foreign language at Chilean

universities and they should have more than five years of work experience.

Research Question

What beliefs shape the cognitive dimension of a group

of 30 university English teachers about their own role in the teaching and

learning process of English in higher education?

Research Assumption

Beliefs influence the teaching practice. During the

process of teaching and learning, teachers must take a series of decisions that

are guided by their linguistic and pedagogical beliefs which define their

performance in the classroom.

Instruments

• A

semi-structured interview was used as a specific model of verbal interaction

with the objective of understanding the phenomenon of linguistic and

pedagogical beliefs of the participants about their role as teachers. The

dimensions that were taken into account for the interview were as follows:

theoretical principles of teaching English, theoretical approaches of the

teaching role and functions of teachers, the English teacher as a professional

in education, the role of students, the different learning styles, the

relationship between objectives, contents, methods, activities, context as well

as teaching resources, materials, information and communication technologies

(ICT), and assessment. This article focuses the attention on some of the most

important actors in pedagogical innovation: teachers, their role and functions

in the learning process.

• A

self-reflection interview was applied in which the participants created a time

line with the experiences they considered most relevant to their teaching

practice and then explained the reasons they considered to choose the different

experiences.

• An

autobiographical diary was used as a procedure to find out what teachers

thought about different aspects of their teaching over a period of six months.

Procedure for Data

Analysis

After validating the data generation techniques

mentioned above, we collected from the autobiographical diaries,

semi-structured interview, and self-reflection interview and then performed the

data analysis. The data analysis is a representation of the social phenomenon

and creates a vision of different social contexts and its actors. An analysis

of initial structural content was performed and then the data were submitted to

the ATLASTI qualitative analysis software, which allowed us to find coherence

as well as explicit and implicit meaning of the data through the dialectics

between text comprehension and interpretation of the different actors. The data

analysis was performed following the subsequent steps: transcription,

segmentation, codification, initial categorization, a

systematic search of the different properties of the found

categories, integration of categories, and finally the search for relationships

between the categories to establish sub-categories.

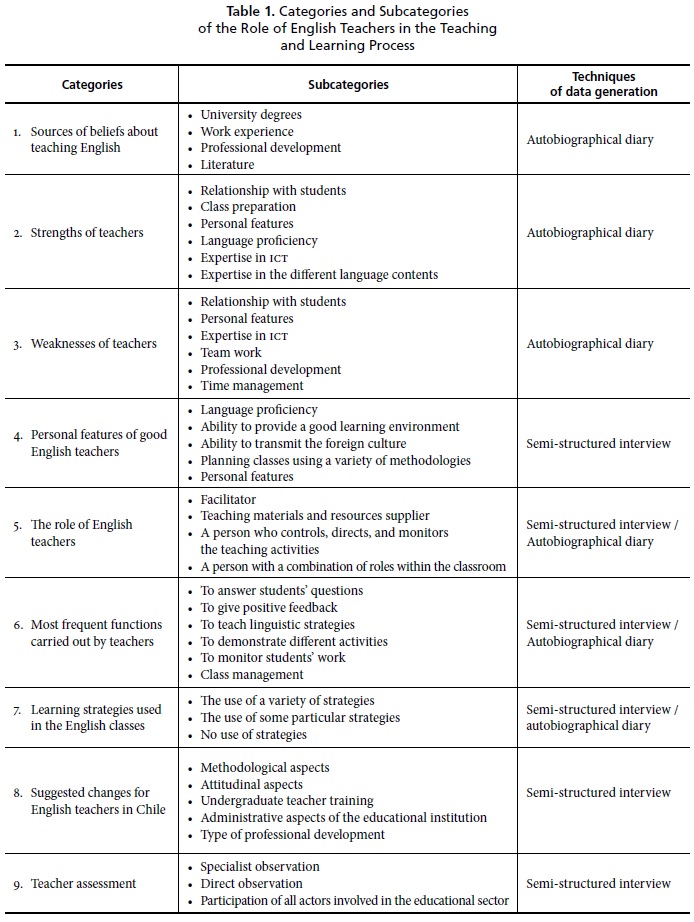

The categories and subcategories obtained were

subjected until saturation occurred, thus ensuring data reliability in

qualitative studies.

Analysis and

Discussion of the Data

This section addresses the following dimension:

“the university teacher of English in the teaching and learning process

of a language.” This dimension includes the role of teachers in the

teaching and learning of language. Nine categories were set up,

most of them divided into subcategories that emerged from the

participants’ discourse either in the semi-structured interview,

self-reflection, or autobiographical diary (see Table 1).

Sources of Beliefs About Teaching English

The teachers participating in this research stated

that the sources of their beliefs about teaching English were mostly based on

literature and their own work experience. Additionally, a significant

percentage of the participants affirmed that their professional development had

influenced their views of teaching English. It is interesting to note that a

very small group considered undergraduate university studies as a source for

their beliefs. The main sources of beliefs about teaching English identified by

the participants are shown in Figure 1.

The fact that most teachers’ beliefs come from

literature in the first place and from working experience in the second place poses a real challenge for the kind of professional development

teachers would likely need to reshape those pedagogical practices that could be

in the way of students’ effective learning. In other words, if literature

is strategic for the shaping of beliefs, teachers should be exposed to

publications and reading that can really help them to make appropriate

classroom decisions on behalf of effective language learning.

Strengths of

Teachers

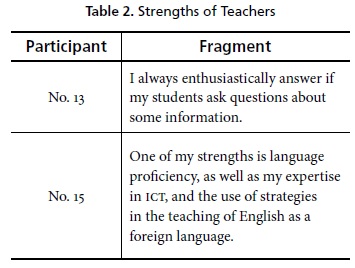

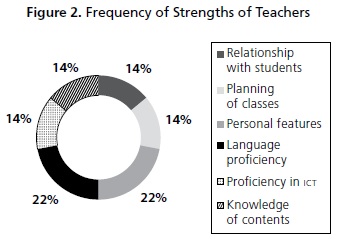

In the category called Strengths of Teachers, the

participants agreed on mentioning aspects such as language proficiency (English),

their ICT expertise and their expertise in the contents of the subject they

teach. They also emphasized the good relationship teachers should have with

their students and the teachers’ planning of their classes. Certain

personal features the participants possess are said to contribute both to

establishing a good classroom environment and to an effective learning process.

In Table 2, some fragments of autobiographical diaries

are shown to support the category mentioned above.

These beliefs reflect that in order to be effective

classroom managers, teachers should possess subject-matter knowledge and

pedagogical content knowledge of conceptual, procedural, and attitudinal natures.

For the research participants, any teacher of English should know English very

well (conceptual knowledge), should be able to use the language effectively

(procedural knowledge) and should be capable of creating the necessary

affective and emotional classroom conditions for learners to learn the

language.

Figure 2 summarizes the strengths

participants considered important in their teaching practice.

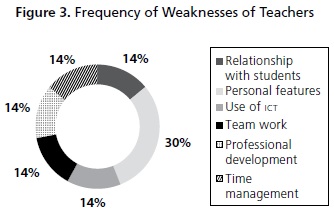

Weaknesses of

Teachers

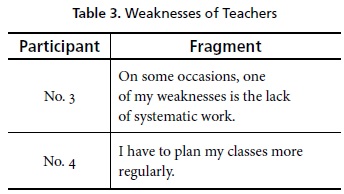

The participants’ own personal features such as

the lack of systematicity in their work, impatience,

and insecurity in some areas, among others, were some of the most referred

weaknesses. Lack of rapport with students, poor expertise of ICT, deficient

continuous professional development, poor time management, and lack of teamwork

were identified in second place. In Table 3 there are

some fragments from autobiographical diaries to support the subcategories

mentioned above.

The nature of beliefs is context oriented. Teachers of

similar socioeducational contexts tend to hold

similar beliefs. The participants of this study share a similar educational

context because all of them work in tertiary education and teach English to

students of common social backgrounds under very similar institutional

conditions. Therefore, diagnosing teachers’ beliefs

constitutes a fundamental starting point to later on identify

teachers’ professional development needs.

Figure 3 summarizes the weaknesses

that teachers claim to possess.

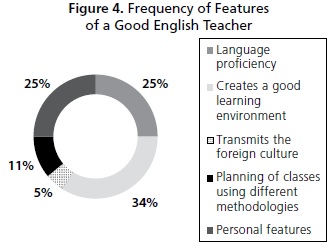

Personal Features

of Good English Teachers

Regarding Personal Features of Good English Teachers, most

of the participants mainly chose those traits that allowed them to create a

relaxed learning atmosphere in classes, some of which were maintaining a good

relationship with students or taking the different types of learning processes

into account. On a second level of importance, participants mentioned both the

importance of feeling confident about their language proficiency and also some

personal features among which they included the use of humour,

patience, and their own motivation. Being able to plan lessons according to new

methodologies and transmitting the foreign culture to the students were

mentioned by a smaller percentage. In Table 4, there is a

fragment selected from the semi-structured interviews to support the

abovementioned ideas.

Beliefs also mirror the kind of classroom practices

teachers declare to be conducting. Hence, the analysis of teachers’

beliefs also represents a strategy to identify effective and ineffective

classroom practices that either foster or hinder students’ language

learning. The beliefs held by these research participants reveal interesting

communication-oriented teaching practices that match with what empirical

research claims to work for the development of communication.

Figure 4 summarizes the opinions

of the participants about the features of a good English teacher.

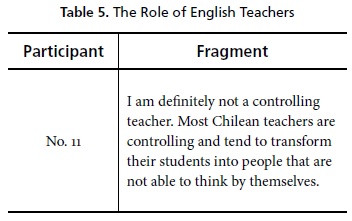

The Role of English

Teachers

To inquire about the role teachers often have in the

classroom, the participants were asked to identify with one or more

alternatives from a list proposed by Brown and Frazier (2001). Most identified

with the premise that teachers should be a source of information, a role in

which they take a back seat to allow students to be in charge of their language

development, but are always available to give suggestions when students ask for

any kind of help.

The second most frequent role mentioned was that of

facilitator of the learning process; teachers help students to overcome

difficulties and find their own paths to communication. The third most stated

opinion was that, depending on the activity or the type of students, the roles

teachers have change or become intertwined. A smaller group of the participants

believe their role is to plan lessons and then allow students to be creative

within the established parameters. Finally, a minority of the participants

mentioned the role of controlling teachers that do not give many opportunities

for the different learning processes to develop. Table 5

contains a fragment selected from the semi-structured inter views to support

the subcategories mentioned above.

These research participants hold beliefs that align

with communicative teaching regarding the different roles teachers assume in

the classroom in order to promote negotiation and communication. This way the

language classroom becomes a dynamic space for learners’ interaction, in

which teachers assume a wide variety of roles based on what they encounter in

the complexity of the teaching and learning process.

Figure 5 illustrates the beliefs

teachers have about their roles within the classroom.

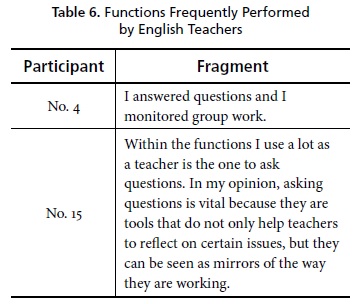

Most Common

Functions Performed by the English Teacher

With reference to the different strategies used by

teachers, the participants claimed not to have a lot of knowledge about this issue

thus they are reluctant to use these strategies overtly in the teaching and

learning process. Regarding classroom management, the participants stated that

teaching university level students does not present any problems requiring this

function. Table 6 shows excerpts taken from the

autobiographical diaries and semi-structured interviews to support the

categories mentioned above.

Figure 6 shows the most common

functions performed by English teachers as stated by the participants.

An effective language teacher should be able to

demonstrate a wide array of classroom management strategies that obviously will

be activated by the learners’ language needs and the requirements of the

tasks. Teachers should be able to turn to the appropriate classroom management

strategies based on their position of active and critical classroom

decision-makers.

Learning Strategies

Promoted in English Classes

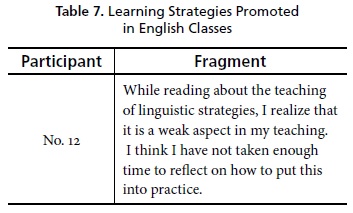

When being asked about the category called Learning

Strategies Promoted in English Classes, most of the participants answered they

did not teach learning strategies either because of their ignorance on the

topic or their lack of knowledge to distinguish the appropriate strategies for

the different skills. Just a small number of participants stated they not only

taught some kind of linguistic strategies but also some other strategies that

were useful in the learning process itself. They also

declared that in order to teach a language, it was essential not only to know

the learning strategies and use them during class, but also to explicitly teach

them so that students are able to apply these strategies in other contexts. Table 7 shows a fragment selected from the semi-structured

interview to illustrate the abovementioned opinions.

The use of the current research instruments helped us

to identify which teaching strategies were at a disadvantage for these research

participants. For learners to be effective language users, they should be

explicitly exposed to the teaching of learning strategies that can help them to

consciously use resources to overcome any language problem that could interfere

with communication. These research participants’ beliefs reveal that

their knowledge and use of strategic teaching is weak; therefore, this is an

area of their teaching that requires reinforcement through reflection and

professional development.

In Figure 7 the learning

strategies that teachers claim to promote are shown.

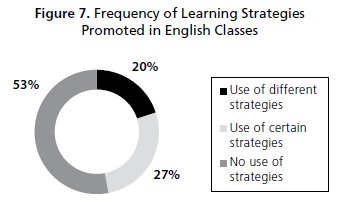

Suggested Changes for

Teachers of English in Chile

This category emerged when participants were asked

whether they considered it necessary to make changes in the way English is taught

in Chile. In first place, issues related to changes in attitude, such as self-development,

teamwork and greater autonomy were mentioned. The second place is shared by

methodological and administrative issues such as reduce the number of hours a

teacher has to be in front of a class, diminish the number of students per

room, and the professional development teachers can obtain within their own

schools. It has to be said that there was only a small number of participants

suggesting changes in the initial training of teachers. Table

8 contains a fragment of semi-structured interviews to illustrate this last

aspect.

Figure 8 illustrates the changes

suggested in the teaching of English in Chile.

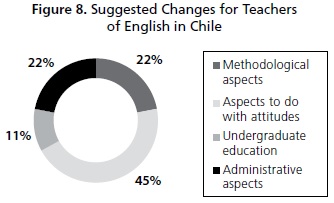

Regarding the type of professional development

suggested for teachers of English in Chile, the participants primarily

manifested the need to update their knowledge on new methods of teaching

languages, ICT and different learning styles, new learning strategies, the

capacity for reflection, and the evaluation process. Secondly, importance was

given to the improvement of language skills and classroom management. Finally,

in the subcategory called Areas of Interest, the following aspects were

mentioned: the neurosciences (set of sciences which researches the nervous

system with particular interest in the way that the brain activity relates to behaviour and learning) and also internships for teachers,

defined as a set of practical activities carried out by teachers that will

allow them to apply knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values in the educational

field in an integrated and selective way (see Table 9).

Figure 9 illustrates the type of

professional development suggested.

Diagnosing the changes and type of professional development

required by teachers of English at a university level through belief

identification is an inductive approach for determining teachers’

professional development needs. Very often organizations and institutions tend

to have a deductive approach as far as professional development is concerned.

Institutions frequently determine in advance what kind of training teachers need, which obviously creates resistance and

reluctance on the teachers’ part to participate in pedagogical change and

innovation. Beliefs strongly reflect what someone truly accepts as truths that

guide their actions.

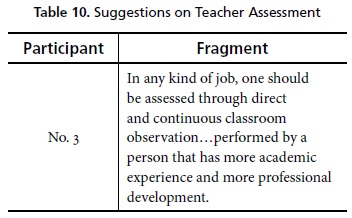

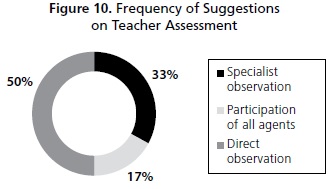

Teacher Assessment

As for Teacher Assessment, all participants were fully

in agreement of this process. In the next category, the best ways to assess

teachers, most of the participants suggested direct classroom observation

because it allows an immediate and accurate view of the various phenomena that

occur within the classroom. The second most noted opinion was the importance of

the teacher assessment process to be carried by a specialist who can provide

specific ways to overcome weak areas observed. A third group suggested that

this process should take into account the participation of different actors in

the educational field, such as area coordinators, fellow teachers, and/or

students (see Table 10).

Teacher assessment is a sensitive and context bound

issue because just the mere suggestion of any kind of assessment or appraisal

generates resistance on the part of teachers. For this matter, belief

identification on teacher assessment before conducting this process constitutes

a key step for the implementation of a robust system of teacher assessment.

Figure 10 summarizes the

suggested format for teacher assessment.

Conclusions

and Implications

Research on beliefs of teachers is becoming important

because there are theoretical and empirical reasons suggesting they affect the

teaching practice. The present study explored the cognitive dimension of a

group of 30 university teachers of English. The number of participants allowed

a snapshot of what teachers think, know, and believe regarding what they do in

the classroom and of the learning process in general. It seems interesting to

note that the participants readily expressed their beliefs about the various

issues raised and recognized that these beliefs are generated mainly from

theory or from their own professional experience.

Revealing the beliefs of a group of university

teachers contributes valuable information to the constant concern about

instances of teacher training designed to meet the needs and interests of

teachers in such a way that it is meaningful for them so it can contribute to

the improvement of their teaching practice and the achievement of effective

learning by students.

The use of an interview and an autobiographical diary

as instruments for collecting qualitative data from the respondents is very

useful for maintaining the richness and necessary subjectivity of

teachers’ discourse. Beliefs anchor themselves in people’s long

term semantic memory and can probably be reshaped when they are confronted

against evidence that does not fit in people’s cognitive framework. The

responses from both the interview and the diary really depict teachers’

inner classroom world; teachers reveal their strengths, weaknesses, personal

characteristics, classroom roles, and views on the teaching and learning of

English.

In brief, belief identification encourages teachers to

self-reflect on their own views and classroom practices and contrast their

views with those of other teachers. Besides, teachers are seen as active

decision-makers and not just as mechanical implementers of the prescribed

language curriculum. The beliefs held by the research participants filter new

information and experiences and are very much influenced by their own

experience as learners.

1 The research

findings are part of a government-funded grant entitled FONDECYT REGULAR (Nº 1120247)

“Investigación del conocimiento profesional, las creencias

implícitas y el desempeño en aula de estudiantes de

Pedagogía en Inglés como estrategia de generación de

indicadores de monitoreo de su proceso formativo.”

References

Barcelos, A., & Kalaja, P. (2011). Introduction to “Beliefs about SLA revisited.” System: An International Journal of

Educational Technology and Applied Linguistics, 39(3), 281-289.

Bisquerra, R. (2009). Metodología de la

investigación educativa [Methodology of educational research] (2nd ed.). Madrid, ES: Editorial La Muralla.

Borg, S. (2003). Teacher cognition in language teaching: A review of

research on what language teachers think, know, believe, and do. Language Teaching, 36(2), 81-109.

Borg, S. (2009). Introducing language teacher

cognition. Retrieved from http://www.education.leeds.ac.uk/assets/files/staff/borg/Introducing-language-teacher-cognition.pdf

Borg, S., & Al-Busaidi, S. (2012). Learner autonomy: English language teachers’ beliefs and

practices. ELT Journal, 12(7), 1-45.

Brown, D., & Frazier, S. (2001). [Review of the book Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to

language pedagogy, by H. D. Brown]. TESOL

Quarterly, 35(2), 341-342.

Corbetta, P. (2003). Metodología y técnicas de

investigación social [Methods and techniques of social research]. Madrid,

ES: McGraw-Hill Interamericana de España.

Díaz, C., Martínez, P., Roa,

I., & Sanhueza, M. G. (2010). Una fotografía de las cogniciones de

un grupo de docentes de inglés de secundaria acerca de la

enseñanza y aprendizaje del idioma en establecimientos educacionales

públicos de Chile [A snapshot of a group of English teachers’ conceptions about English teaching and learning in Chilean public education]. Folios,

31, 69-80.

Díaz, C., & Solar, M. I. (2011).

La revelación de las creencias

lingüístico-pedagógicas a partir del discurso del profesor

de inglés universitario [The revelation of pedagogical and linguistic beliefs from EFL university teachers’ discourse]. Revista de Lingüística

Teórica y Aplicada (RLA), 49(2), 57-86.

Farrell, T. (2006). The teacher is

an octopus. Regional Language

Centre Journal (RELC), 37(2), 236-248.

Freeman, D. (2002). The hidden side of the work: Teacher knowledge and

learning to teach. A perspective from North American

educational research on teacher education in English language teaching. Language Teaching, 35(1), 1-13.

Gross, B. (2009). Tools

for teaching. San

Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kalaja, P., & Barcelos, A. (Ed.). (2003). Beliefs about SLA: New

research approaches. Dordrecht, NL: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Kane, R., Sandretto, S.,

& Heath, C. (2002). Telling

half the story: A critical review of research on the teaching beliefs and

practices of university academics. Review

of Educational Research, 72(2), 177-228.

Kasoutas, M., & Malamitsa, K.

(2009). Exploring Greek teachers’

beliefs using metaphors. Australian

Journal of Teacher Education, 34(2), 64-83.

Levin, B. B. (2001). Lives of teachers: Update on a longitudinal case

study. Teacher Education Quarterly, 28(3),

29-47.

Northcote, M. (2009). Educational beliefs of higher education teachers and students:

Implications for teacher education. Australian

Journal of Teacher Education, 34(3), 69-81.

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research:

Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of

Educational Research, 62(3), 307-333.

Richards, J., & Lockhart, C. (1996). Reflective

teaching in second language classrooms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Stenberg, K. (2011). Working with identities.

Promoting student teachers professional development. Helsinki, FI: University of

Helsinki, Faculty of Behavioural Sciences, Department

of Teacher Education.

Tudor, I. (2001). The

dynamics of the language classroom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Woods, D. (1996). Teacher

cognition in language teaching: Beliefs, decision-making and classroom practice.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

About the

Authors

Claudio Díaz Larenas, PhD in Education and Master of Arts in Linguistics. He works at Facultad de Educación and Dirección

de Docencia de la Universidad de Concepción

(Chile), where he teaches English, discourse analysis, and efl

methodology and assessment. He has researched in the field of teacher cognition

and language assessment.

Paola Alarcón Hernández, PhD and Master of Arts in Linguistics. She teaches Spanish grammar and Latin at Universidad

de Concepción (Chile).

Andrea Vásquez Neira, Master of Arts in Linguistics. She teaches English

Language at Universidad de Concepción (Chile).

Boris Pradel Suárez, Master of Arts in Linguistics. He teaches English

Language and Phonetics at Universidad de Concepción (Chile).

Mabel Ortiz Navarrete, PhD candidate in Linguistics and Master of Arts in

Information and Communication Technologies. She teaches English, discourse analysis, and ICT at Universidad Católica de la Santísima

Concepción (Chile).