Diary Insights of an EFL Reading

Teacher

Apreciaciones de un profesor de lectura en lengua inglesa

escritas en un diario de clase

Sergio Lopera Medina*

Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia

This article

was received on December 3, 2012, and accepted on February 10, 2013.

It is often

argued that classroom diaries are subjective. This article explores the diary

insights of a foreign language reading teacher. The inquiry was based on the

following research question: What do the diary insights really evidence about

the teaching practices of a foreign language reading teacher? As a research

method, a case study was implemented. Five instruments were used to collect

data: diary of the teacher, observations, questionnaires, tests, and focus groups.

Given that motivation, interaction, reading improvement, and the application of

reading strategies were supported by the research instruments, it would seem

that a diary can be objective.

Key words: Diaries,

diary insights, reading in English, support.

A menudo se argumenta que los diarios de clase son

subjetivos. En este artículo se exploran las apreciaciones que un

profesor de lectura en inglés como lengua extranjera registra en su

diario. La indagación se basó en la siguiente pregunta de investigación:

¿Qué apoya realmente las anotaciones de diario acerca de las

prácticas de enseñanza de un profesor de lectura en lengua

extranjera? Como método de estudio se implementó el estudio de

caso. Se utilizaron cinco instrumentos para recolectar la información:

diario del profesor, observaciones de clase, cuestionarios, exámenes y

grupos focales. Dado que estos instrumentos de investigación incidieron

en la motivación, la interacción, la mejoría en lectura y

en la aplicación de las estrategias de lecturas, se podría

concluir que un diario puede ser objetivo.

Palabras

clave: apoyo, apreciaciones de diarios,

diarios, lectura.

Introduction

Researchers

debate the usefulness of diary studies in learning or teaching languages

(Bailey, 1991; Bailey & Ochsner, 1983; Brown,

1985; Long, 1980; Schmidt & Frota, 1986).

Concerns involve the diarist’s subjectivity in keeping a diary, the amount of time the diarist devotes

(time-consuming), the inconsistent way to track ideas, and the lack of general

conclusions.

The purpose

of this article is to explore and support some diary insights made upon

reflection by a foreign language teacher in a reading course for graduate

students. This article begins with the literature review and examines the

characteristics of diaries, reading, motivation, and interaction. Then, the

methodology, the context, the course, participants, and the research

instruments are presented. Finally, findings are described and the conclusions,

implications, and limitations are given.

Review of Literature

Diary

In the

academic context, a diary is an academic instrument that is used to record

introspective reflection in first person about someone’s learning or

teaching (Bailey, 1990). The teacher or student reports issues such as

affective factors, perceptions, and language learning strategies (Bailey & Ochsner, 1983). Diaries are useful to obtain classroom

issues and constitute a valuable tool in order to discover teaching or learning

realities that are not possible to be discovered through direct research

observation (Nunan, 1992; Bailey, 1990; Numrich, 1996). Goodson and Sikes (2001) state the

importance of a diary:

Not only is a document of this kind useful for

providing factual information, it can also help with analysis and

interpretation, in that it can jog memory and indicate patterns and trends

which might have been lost if confined to the mind. (p. 32)

McDonough

and McDonough (1997) argue that diary studies are helpful in language contexts

as they support qualitative and quantitative information. Diarists can also

have an introspective and retrospective view of their teaching or learning process.

Russell and Munby (1991), and Palmer (1992) argue

that diaries may provide a rich source of data in order to understand teachers’

practices. When teachers read their diaries they become conscious of what they

know and really do and they reflect on their role as teachers. As a result,

they may become critical (Bailey, 1990). There are two types of processes for

reading the diary: primary (also called direct or introspective) and secondary

(also called indirect or non-introspective). In the first type the diarist is

the person who reads and reflects about the learning or teaching process. In

the second type, an outsider reads and interprets the diarist’s entries

about his/her learning or teaching process (Curtis & Bailey, 2009).

Characteristics of Diaries

Curtis and

Bailey (2009) state that teachers or learners usually keep hand-written

diaries; however, they can also be audio-taped. The authors argue that this

technical form could be time-consuming due the transcription it may need.

Instead, a word processed diary is a good option because having electronic

information facilitates the data analysis. The authors also argue that diarists

can use figures in order to represent ideas pictorially and such figures guide

to identify issues such as interaction, motivation, and participation, among

others. In the same vein, diarists can use their mother tongue or second

language to record their ideas. When learners have a low proficiency level they

face difficulties in making entries. A good option is to combine the mother

tongue and target language to lessen students’ difficulties. Conversely,

keeping a diary becomes a very good option with which to practice the target language

when learners have an intermediate or advanced level.

On the other

hand, there are drawbacks to diaries. Schmidt and Frota

(1986), and Seliger (1983) support that the nature of

diaries is to keep a subjective perception of the diarist’s experiences

leading to subjectivity. Moreover, it could be difficult to categorize and

reduce data when diarists do not have a consistent way of keeping a diary. Nunan (1992) even questions if the conclusions made by a

single subject can be extrapolated to other settings. However, Curtis and

Bailey (2009) suggest the idea to keep diaries with subjective and objective

issues. Diarists may have entries that describe feelings or ideas that they had

in a specific moment of the class, or they can also have facts of a specific

issue that support their entries. As a result, it would be useful to have

factual records as well as subjective ones in order to obtain a precise picture

of the teaching or learning process. The authors suggest the following elements

to consider when keeping a journal:

• Keep

a detailed chronological record of the entries

• Include

the day, date, and time of each entry

• Include also information about

number of students and their seating arrangements

• Write

a summary of the lesson

• Include

handouts and assignments in the diary

• Write thoughts or

questions to be considered later (p. 71)

Other

elements can also be included: The objective of the diary is to record or

develop ideas instead of correcting or crafting; the language could be personal

rather than academic or formal; the writing style has to make sense primary to

the diarist, not to the outsider.

Diaries can

be used as an assessment tool. Brenneman and Louro (2008) argue that diaries provide teachers a critical

view of how individuals conceptualize and apply an issue in the process of

learning. Diaries tell teachers about insights into individual student’s

language processes when teachers keep track of each student. In fact, diaries

support anecdotal evidence of what learners do, understand, and misunderstand

in a language class. Thus, the teacher can use it to verify and give an account

of the learning process.

Reading

Reading is a

complex process in which the reader has to comprehend the text. Alyousef (2005)

states that reading is an “interactive process between a reader and a

text which leads to automacity or (reading fluency).

In this process, the reader interacts dynamically with the text as he/she tries

to elicit the meaning” (p. 144). However, there are two important

elements that the reader needs to possess: linguistic knowledge and background

knowledge. The former refers to the awareness about the language, such as

grammar or vocabulary structure. The latter involves the familiarity the reader

has with the reading content. Cassany (2006),

González (2000), Grabe and Stoller

(2002), and Weir (1993) support that the reader also needs a cognition process

because she/he has to predict, interpret and memorize information in order to

decode the message.

Foreign

language readers have to make a bigger effort to interact with texts because

they might face grammar or vocabulary difficulties (Cassany,

2006). Thus, the role of the teacher becomes crucial, as foreign language

readers need to be guided to overcome those difficulties.

Reading Models

Aebersold and Field

(1997) state that there are two essential models in reading: bottom-up

processes and top-down processes. Bottom-up processes involve readers building

the text beginning from small units (letters to words) to complex ones

(sentences to paragraphs). In the top-down processes readers have to integrate

the text into their existing knowledge (background knowledge). Grabe and Stoller (2002) ask

language teachers to use both processes with students in order to have

successful readers.

Reading Strategies

Reading

strategies help learners interact with the readings and different authors

highlight the importance of applying them in language learning settings (Chamot, Barnhardt, El-Dinary, & Robbins, 1999; Hosenfeld,

1979; Janzen, 2001; Lopera, 2012; Mikulecky

& Jeffries, 2004; Osorno & Lopera, 2012). When students are trained to use reading

strategies they know what to do when facing troubles with readings (Block, 1986).

Language teachers can use simple reading strategies such as previewing,

predicting, guessing word meanings; or complex ones such as inference and

summarizing. Janzen (2001) proposes five classroom activities to work with the

reading strategies:

• Explicit discussion of the

reading strategies and when to use them

• Demonstration of how to

apply a reading strategy (modeling)

• Involvement with the

reading in terms of reading aloud and sharing the process while applying the

strategies

• Discussion

of the activities in the classroom

• Practice with the reading

material of the course (p. 369)

Arismendi, Colorado,

and Grajales (2011); Block (1986); Carrell (1998); Lopera (2012); Mikulecky and Jeffries (2004); and Poole (2009) have

explored the application of reading strategies with students and their findings

support their usefulness for learners.

Motivation

Motivation

plays an important role in foreign language as it engages students in an active

involvement to learn (Oxford & Shearin, 1994).

Chen and Dörnyei (2007, p. 153) state that the

function of motivation is to serve “as the initial engine to generate

learning and later functions as an ongoing driving force that helps to sustain

the long and usually laborious journey of acquiring a foreign language.”

Brown (2001) divides motivation into intrinsic and extrinsic. The former helps

students engage in the activities for their own sake in order to satisfy

internal rewarding such as learning, curiosity, or personal fulfillment. On the

other hand, extrinsic motivation goes externally in order to avoid punishment

or to satisfy reward such as good scores, prizes, or money.

Interaction

Brown (1994)

states that interaction is the main part of

communication in which people send, receive, interpret, and negotiate messages.

The author suggests that language learning classrooms should be interactive

even from the very beginning. The role of the teacher is crucial in order to

prompt interaction in the classroom as she/he has to be a guide, a moderator,

or a coordinator in the classroom. In the same vein, students also have to

participate individually or in groups when the teacher asks them to do it. When

these two agents give their parts, the results are more positive in the process

of learning.

Finally,

when teachers observe and record issues such as interaction, motivation, and

application of reading strategies in their diary, they are better equipped to

analyze, assess, and reflect upon their students’ processes. For the

purpose of this paper, all these elements were taken into account.

Method

This study

followed the principles methodology of a multiple case study (Creswell, 2007;

Merriam, 1998; Tellis, 1997; Yin, 2003) as the team

of researchers1 wanted to support the

teacher’s diary insights in a foreign language reading comprehension

course. Researchers used the grounded approach when they categorized the data

(Freeman, 1998). The following research question guided their inquiry: What do

the diary insights really evidence about the teaching practices of a foreign

language reading teacher?

Context

Universidad

de Antioquia (Medellín, Colombia) asks

graduate students to certify reading proficiency in a foreign language when

getting specializations.2 Students have two

options: to certify by either attending a classroom course or by taking a

proficiency test. Students were given a third option in 2007 when the EALE (Enseñanza y Aprendizaje de

las Lenguas Extranjeras = Teaching and Learning Foreign Languages)

research group designed a reading course in English in a web-based distance

format. In 2009, EALE decided to carry out a research project3 in order to compare the effects of a web-based course

to a face-to-face course. The study of the teacher’s diary is derived

from this research project.

Participants

The Teacher

The teacher

was part of the research team and as well as a full-time professor at Sección Servicios, Escuela de Idiomas

(School of Languages). He had ten years of experience teaching foreign language

reading comprehension courses for both graduate and undergraduate students.

The Students

There were

27 students (17 women and 10 men); they were between 20 and 51 years old.

Students were in the first semester of different specializations in Law:

Process Law, Constitutional Law, Family Law, Administrative Law, and Social

Security Law. Only one student dropped the course.

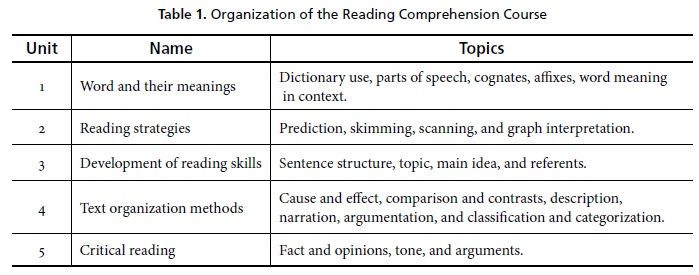

The Reading Comprehension Course

The name of

the course was English reading comprehension for graduate programs (Competencia lectora en inglés para posgrados) and its main goal was to guide students in

the use of different types of reading strategies in different types of

readings. Students attended the course Tuesdays and Thursdays from 6 to 9 p.m.

The course lasted 120 hours and was divided and organized into five different

units as shown in Table 1.

Data Collection and Analysis

Other

research instruments accompanied the diary in order to triangulate data (Ellis,

1989). The different sources of information helped researchers compare and

validate the data issues encountered in the diary. There were a total of five

instruments used to gather data: diary of the teacher, questionnaires,

observations, tests, and focus groups. Each instrument is explained below.

Diary of the Teacher

The teacher

recorded all his reflections and observation about the teaching process of each

class session in order to construct a critical view (Bailey, 1990; Jeffrey

& Hadley, 2002). The teacher kept the diary in English and took about two

hours for each class to write each entry electronically. It took him about five

months to finish the diary. It is worth stating that he was aware of and had

experience writing the diary for research purposes.

Questionnaires

Students

completed three questionnaires: evaluation of the course and the teacher,

reading strategies and motivation, and self-evaluation. There were multiple

choice questions and open questions for completing each questionnaire.

Tests

Two types of

tests were used on students: before and after the pedagogical intervention (2

tests—pretest and posttest), and different tests for each unit of the

course. Regarding pretest and posttest, each test contained two readings texts,

each with 13 multiple choice questions (the readings and questions simulated

standardized tests like the Test of English as a Foreign Language, TOEFL).

Students had to interact with reading topics such as inference, scanning,

analyzing topics and main ideas. In the different tests of each unit, the

teacher designed short readings that aimed at evaluating the topics of the

unit. There were multiple choice questions as well as open questions on the

tests.

Observations

Researchers

observed ten class sessions. They examined issues such as teaching, behaviors,

learning strategies, interaction, and participation in the classroom (Brown,

2001).

Focus group

Students had

a focus group session (Dendinger, 2000) at the end of

the course in order to discuss their learning experience. Researchers prepared

some open questions regarding interaction, application of reading strategies,

vocabulary improvement, and positive and negative aspects of this course. The

session was audio-taped.

Findings

Researchers

mixed both primary processes and secondary processes to read the diary (Curtis &

Bailey, 2009). All the data were transcribed and researchers read and labeled

the data individually. They then shared and discussed some important ideas in

groups and coded the data in order to have categories. Finally, consensus was

obtained through data triangulation (Freeman, 1998). Researchers translated

some excerpts from Spanish to English in order to use them as support.

Researchers

validated some diary entries made by the teacher in order to support

objectivity. Four main topics emerged from the diary: motivation, interaction,

improvement, and the application of reading strategies. The findings are

explained below.

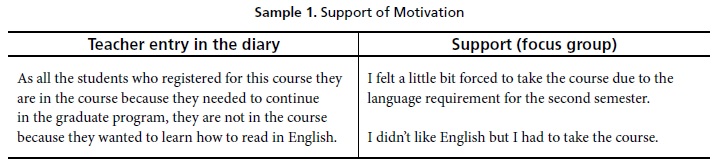

Motivation

The teacher

reported that students’ motivation was mainly extrinsic, as they needed

to fulfill the reading requirement in order to register for the second semester

of their law specializations. Researchers could support this reflection in the

focus group, as some students commented on the need to fulfill the requirement

(see Sample 1).

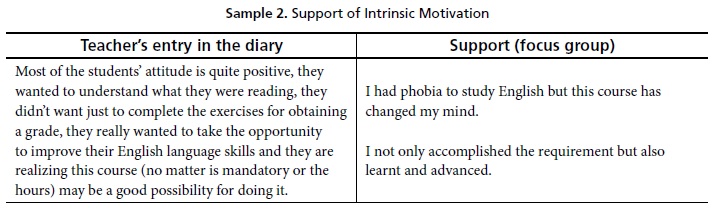

Although

students’ motivation was mainly extrinsic, researchers noted that

students gained intrinsic motivation during the course. Students’

perceptions changed positively toward the course and satisfaction was

perceived. This issue is supported by the students’ comments in the focus

group (see Sample 2).

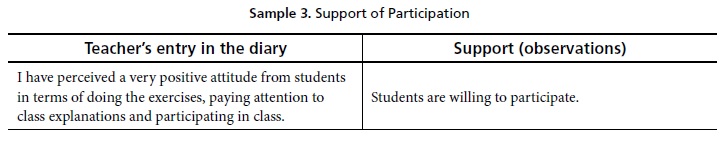

Another

motivational factor was participation. Students’ participation was a

constant in the course leading to a positive attitude. Learners were willing to

participate in the exercises suggested by the teacher. The teacher and

observers noted this motivational issue, as shown in Sample

3.

On the other

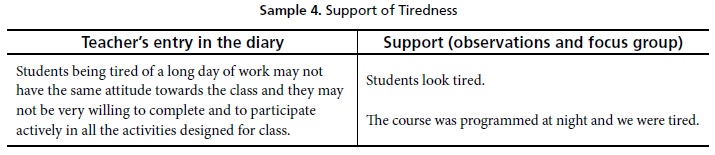

hand, the teacher observed that students looked tired due to

their work load. Students were tired because they worked during the day then finished

up the day attending the course (see Sample 4).

Interaction

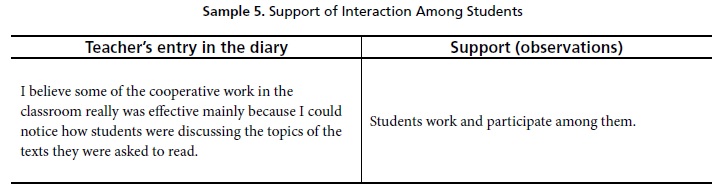

There were

three types of interaction: interaction among students, interaction between the

teacher and students, interaction with the material. In the first interaction a

sign of cooperation was perceived among students. Students worked together in

order to do a reading activity assigned by the teacher. Students interacted

themselves confirming answers, checking understanding, discussing issues and,

usually, working in pairs or groups. Researchers noted that students helped

each other. This was validated by researchers in the observations, as shown in Sample 5.

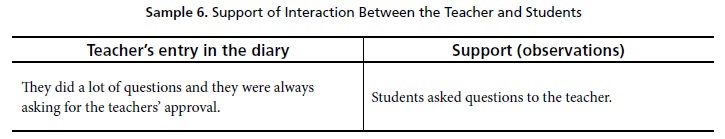

There was

constant interaction between the teacher and students. The teacher asked the

students to answer some questions about an exercise. In the same vein, students

asked the teacher different questions when they had doubts about the exercises

or the readings (see Sample 6).

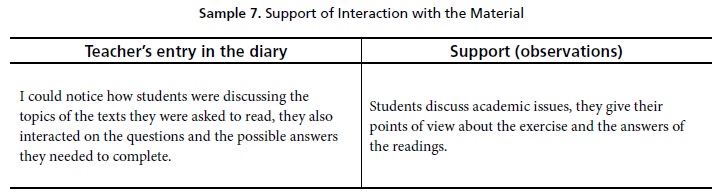

Finally,

students interacted with the materials. The teacher asked the students to read

texts and complete the activities designed by him. Researchers noted that

students interacted with the readings because they discussed the content and

the answers based on the readings (see Sample 7).

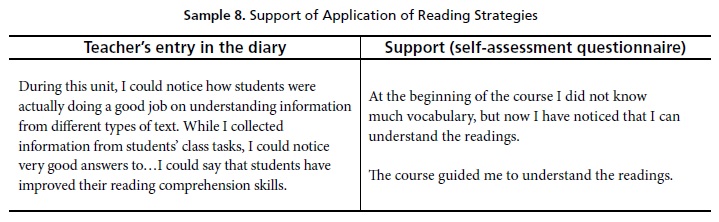

Improvement and Application of Reading Strategies

Researchers

observed that students had learned and applied the reading strategies taught in

the course and this led to reading improvement. Students also evidenced that

they had learnt, as can be read in Sample 8.

Another

source that supports improvement was the assessment of units. The tests of the

units support that students improved and applied the reading strategies. When

the teacher corrected and evaluated the tests, he wrote comments like “it

was a good exercise, congratulations” or “although the answers to

the exercises were ok, you did not provide very precise answers.”

Moreover, the teacher quantitatively reported the scores on the tests (1 to 5,

with 5 being the highest) and researchers validated that most of the scores

ranged from 3.5 to 4.8.

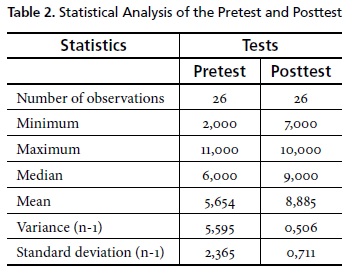

Finally,

another source that supports improvement was the test results. Students

improved considerably when researchers statistically compared the results of

the pretest and posttest administered. Statistics support that students

improved in reading as the mean increased greatly (see Table

2).

Limitations

Guiding and

encouraging the project, the teacher was part of the research group. If the

teacher had not been part of the research group, researchers would probably

have had different findings. The teacher was aware of writing the diary for

research purposes and this could be seen as leading. In fact, he knew the

topics to concentrate on: interaction, motivation, the use of reading

strategies, and improvement. Finally, the number of students was limited and

researchers do not claim that findings could be generalized to broader teaching

or learning contexts.

Conclusions

Some

researchers have argued that people are subjective when they keep a diary (Nunan, 1992; Schmidt & Frota,

1986; Seliger, 1983). However, the findings of the

research suggest that the entries of the diary can be supported by evidence

provided by more objective instruments, such as tests. In fact, motivation,

interaction, reading improvement, and the application of reading strategies

were found in the diary and supported using different research instruments.

Researchers

found that participation, attitude, as well as extrinsic and intrinsic

motivation were motivational factors in the diary. Also, the academic contact

among student-student, student-teacher, and student-material were supported as

interactional issues in the course. Finally, findings support that students

improved and applied the reading strategies. Based on the results, it seems to

be that a diary is objective.

Implication

One of the

findings was related to tiredness. The teacher observed that students were

tired due to the fact that they worked during the day and finished up the day

attending the course. The previous finding implies the need to prepare

interactive classes in order to engage students to be more active in class. It

is suggested that teachers ask students to work in pairs or in groups, bring

topics that deal with students’ interests, bring humor to class, and use

a short and interesting opening activity to start a class (Dörnyei

& Csizér, 1998) as these would be good

options to raise motivation and avoid tiredness in classrooms.

1 It is worth mentioning that the author of this paper

was a member of the team of researchers.

2 Especialización (specialization) is a two-semester

graduate program and the main objective is to update students in their academic

fields.

3 There were six full-time teachers, one advisor, and

three undergraduate students in teaching foreign languages on the research

team.

References

Aebersold, J., &

Field, M. (1997). From

reader to reading teacher. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Alyousef, H. S.

(2005). Teaching reading comprehension to ESL/EFL learners.

The Reading Matrix, 5(2), 143-154.

Arismendi, F.,

Colorado, D., & Grajales, L. (2011). Reading comprehension in face-to-face and web-based modalities:

Graduate students’ use of reading and language learning strategies in

EFL. Colombian Applied Linguistics

Journal, 13(2), 11-28.

Bailey, K. M. (1990). The use of diaries in teacher education programs. In J. Richards, & D. Nunan (Eds.), Second language teacher education (pp.

215-226). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bailey, K. M. (1991). Diary studies

of classroom language teaching: The doubting game and the believing game. In E. Sadono (Ed.), Language acquisition and the second/foreign language classroom (pp.

60-102). Singapore, SG: SEAMEO Regional Language Centre.

Bailey, K.

M., & Ochsner, R. (1983). A

methodological review of the diary studies: Windmill tilting or social science?

In K. M. Bailey, M. H. Long, & S. Peck (Eds.), Second language acquisition studies (pp. 188-198). Rowley, MA:

Newbury House.

Block, E. (1986). The

comprehension strategies of second language readers. TESOL Quarterly, 20(3), 463-494.

Brenneman, K., & Louro, I. (2008). Science journal in

the preschool classroom. Early

Childhood Education Journal, 36(2), 113-119.

Brown, C. (1985). Two windows on the

classroom world: Diary studies and participant observation differences. In P.

E. Larson, E. L. Judd, & D. S. Messerschmitt (Eds.), On TESOL ‘84: Brave New World for TESOL (pp. 121-134).

Washington DC: TESOL.

Brown, D. (1994). Teaching by principles (1st ed.). New York, NY: Longman.

Brown, D. (2001). Teaching by principles (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Longman.

Carrell, P. (1998). Can reading

strategies be successfully taught? ARAL, 21(1), 1-20.

Cassany,

D. (2006). Tras las líneas [Following the lines]. Barcelona, ES: Editorial Anagrama.

Chamot, A., Barnhardt, S., El-Dinary, P.,

& Robbins, J. (1999). The

learning strategies handbook. New York, NY: Longman.

Chen, H.,

& Dörnyei, Z. (2007). The use of

motivational strategies in language instruction: The case of EFL teaching in

Taiwan. Innovation in Language Learning

and Teaching, 1(1), 153-174.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design. Choosing among five approaches.

Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Curtis, A.,

& Bailey, K. (2009). Diary studies. OnCue Journal, 3(1), 67-85.

Dendinger, M. (2000). How to organize a focus

group. Meetings

and conventions. Retrieved

from: http://www.meetings-conventions.com/articles/how-to-organizea-focus-group/c10136.aspx

Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (1998). Ten commandments

for motivating language learners: Results of an empirical study. Language Teaching Research, 2(3),

203-229.

Ellis, R. (1989). Classroom learning

styles and their effect on second language acquisition: A study of two

learners. System, 17(2), 249-262.

Freeman, D. (1998). Doing teacher research: From inquiry to

understanding. Boston, MA: Newbury

House.

González,

M. (2000). La habilidad de la lectura: sus implicaciones en la enseñanza

del inglés como lengua extranjera o como segunda lengua [Reading comprehension: Implications for the teaching

of English as a foreign or second language]. Retrieved

from: http://www.utp.edu.co/~chumanas/revistas/revistas/rev19/gonzalez.htm

Goodson, I.,

& Sikes, P. (2001). Life history

research in educational settings: Learning from lives. London, UK: Oxford

University Press.

Grabe, W., & Stoller, F. (2002). Teaching

and researching reading. London, UK: Pearson Education.

Hosenfeld, C. (1979).

A learning-teaching view of second language instruction.

Foreign Language Annals, 12(1), 51-54.

Janzen, J. (2001). Strategic reading on a sustained content theme. In J.

Murphy, & P. Byrd (Eds.), Understanding

the courses we teach: Local perspectives on English language teaching (pp.

369-389). Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Jeffrey, D.,

& Hadley, G. (2002). Balancing intuition with insight:

Reflective teaching through diary studies. The Language Teacher Online, 26(5), Retrieved

from http://jalt-publications.org/old_tlt/articles/2002/05/jeffrey

Long, M. H. (1980). Inside the “Black

Box”: Methodological issues in classroom research on language learning. Language Learning, 29(1), 1-30.

Lopera, S. (2012). Effects of

strategy instruction in an EFL reading comprehension course: A case study. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional

Development, 14(1), 79-89.

McDonough J., & McDonough, S.

(1997). Research

methods for English language teachers. London, UK: Arnold.

Merriam, S.

(1998). Qualitative research and case study applications

in education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mikulecky, B., &

Jeffries, L. (2004). Reading

power. United States: Pearson, Longman.

Numrich, C. (1996).

On becoming a language teacher: Insights from diary studies.

TESOL Quarterly, 30(1), 131-151.

Nunan, D. (1992).

Research methods in

language learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Osorno, J., & Lopera, S. (2012). Interaction in an EFL

reading comprehension distance web-based course. Íkala, Revista de

Lenguaje y Cultura, 17(1), 41-54.

Oxford,

R., & Shearin, J. (1994). Language

learning motivation: Expanding the theoretical framework. Modern Language Journal, 78(1), 12-28.

Palmer, C. (1992). Diaries for self-assessment and INSET programme

evaluation. European Journal of

Teacher Education, 15(3), 227-238.

Poole, A. (2009). The reading

strategies used by male and female Colombian university students. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’

Professional Development, 11(1), 29-40.

Russell, T.,

& Munby, H. (1991). Reframing: The role of experience in developing teachers’

professional knowledge. In D. Schon (Ed.), The reflective turn: Case studies in and on

educational practice (pp. 164-187). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Schmidt, R.,

& Frota, S. N. (1986). Developing basic conversational ability in a second language: A

case study of an adult learner of Portuguese. In R. Day (Ed.), Talking to learn (pp. 237-326). Rowley,

MA: Newbury House.

Seliger, H. W.

(1983). The language learner as linguist: Of metaphors and realities. Applied Linguistics, 4(3),

179-191.

Tellis, W. (1997). Introduction to case study. The Qualitative Report, 3(2).

Retrieved from: http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR32/tellis1.html

Weir, C.

(1993). Understanding and developing

language tests. Hemel Hempstead, UK:

Prentice Hall.

Yin, R. K.

(2003). Case study research. Design and methods. (3rd edition).

Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

About the Author

Sergio Lopera

Medina, candidate

for the PhD in linguistics, MA in linguistics; specialist in teaching foreign

languages. His research interests are teaching EFL reading comprehension,

compliments in pragmatics. He is a member of the research group EALE (Enseñanza y Aprendizaje en

Lenguas Extranjeras) and a

full time teacher at Universidad de Antioquia (Colombia).