The Impact of Explicit Feedback on EFL High School Students Engaged in

Writing Tasks

El impacto

de la retroalimentación explícita en tareas de escritura en

lengua inglesa de estudiantes de secundaria

Roxanna

Correa Pérez*

Mariela

Martínez Fuentealba**

María

Molina De La Barra***

Jessica

Silva Rojas****

Mirta

Torres Cisternas*****

Universidad

Católica de la Santísima Concepción, Chile

*****gabriela.azulado@gmail.com

This article was received on September 24, 2012, and

accepted on July 20, 2013.

The aim of this article is to examine the impact of

feedback on content and organization in writing tasks developed by learners of

English as a foreign language. The type of study is qualitative and the

research design is a case study. One study involved three students and a female

teacher, and the second consisted of three students and a male teacher.

Research instruments involved were a structured interview, a writing task in

class and document analysis. The findings show that students feel motivated to

re-write a writing task when the teacher provides feedback on content and

organization. Moreover, there was evidence of improvement in the

students’ writing when they incorporated the teacher’s comments.

Key words: Feedback,

motivation, writing, writing tasks.

El objetivo de este

estudio es examinar el impacto de la retroalimentación, orientada a

contenidos y organización, en escritos desarrollados por aprendices de

inglés como lengua extranjera. El tipo de investigación es

cualitativa y el diseño un estudio de casos. Un caso se conformó

con tres estudiantes y una profesora, el segundo quedó compuesto por

tres estudiantes y un profesor. En relación con los instrumentos, se

utilizaron una entrevista estructurada, una tarea de escritura y el

análisis documental. Los resultados muestran que los estudiantes se

sienten motivados a reescribir una tarea de escritura cuando el profesor

comenta las ideas y la organización de esta. Además se

evidenció una mejora en los escritos de los estudiantes al incluir las

sugerencias del profesor.

Palabras clave: escritura,

motivación, retroalimentación, tareas escritas.

Introduction

Many issues may happen with the teacher and learner

interaction during the English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teaching and

learning process. Thus, teachers are always concerned about what is occurring

with their learners during lessons. They want students to learn from their

mistakes; in this case, language teachers expect students to learn a new

language by being aware of the aspects they need to improve. That is why they

provide comments to learners when correcting. Some of the teachers do respond

(in written or oral form) to their students’ tasks without noticing the

effect it may produce on the students. The researchers of this study, during

their pre-service experience, have noticed that language teachers provide these

comments in different ways: some of them mark the text with ticks or crosses,

while others provide the correct answer or just refer to an aspect that needs

to be improved (vocabulary, grammar, or other).

The last five years spent at different schools and in

educational contexts have helped us to notice that learners are not conscious

that receiving feedback gives them the opportunity to be led down the right

path, hence, the potential to learn and improve their writing competence.

Therefore, if students are not involved in understanding the feedback provided,

they will not improve their language competence, regardless of the amount of

time they spent trying to learn it. This reality implies that improving is a

matter of personal commitment and not a matter of time. Learners need to apply those

comments given by their teachers to their learning process in order to avoid

committing the same mistakes over and over. Hence, in order to better

understand the impact of informing the students about their weaknesses or

strengths during the process of learning a foreign language, the researchers

consider it relevant to carry out an in-depth research project. For this

reason, in this study we examined in detail the impact of explicit feedback

provided on content and organization in writing tasks, and whether this

response motivates EFL learners to improve.

In the first part of this article, the reader will

find a review of the principal concepts of this research such as feedback,

writing, feedback on writing and motivation. In the second part, methodological

aspects are described. In the third part, all the data collected are revealed

and then analysed. In the last part, a summary of the

conclusions is presented.

Concept

Framework

In order to define feedback in second language acquisition,

the concept of acquisition will be clarified. Acquisition is considered as the

use and understanding of a language in terms of conveying messages instead of

learning (Krashen, 1981). The concept of feedback on

second language acquisition will be revised.

Feedback

According to Ur (2006), “feedback, in the

context of teaching in general, is the information that is given to the learner

about his or her performance of a learning task, usually with the objective of

improving this performance” (p. 242). The author states that feedback is

the information that explains how well or poorly learners performed. The main

objective is to identify the potential areas where some improvements could be made as well as to foster

students’ autonomy.

In the same context, Aparicio

(2007) adds that feedback is the information given by the teacher to students

about their performance. The author suggests that feedback is the information

an instructor gives to his learners about their performance so they are able to

check themselves and be more successful in fulfilling the goals of a course.

Gattegno (as cited in Nunan, 1995) suggests that

feedback is a fundamental element during the teaching and learning process of

each individual learner since it allows not only the correction of errors during

a written assignment, but also the establishment of rapport and a consistent

relationship between the learners and the teacher. Students react to feedback

looking for teachers’ approval.

However, Ur (2006) emphasises

the idea that when giving feedback it cannot be possible to avoid the idea of

giving judgement. Ur explains that teachers have

feelings and different point of views, and it is difficult not to get involved

when they assess. For this reason Ur states that “Teachers are sometimes

urged to be ‘non-judgmental’ when giving feedback; in my opinion

this is unrealistic. Any meaningful feedback is going to

involve some kind of judgment” (p. 242).

Furthermore, Ur (2006) identifies as one component of

feedback correction the student’s own explanation about his/her

performance in a particular task. As a second component the author identifies

assessment, which allows students to know how good or bad their performance

was.

Sometimes teachers and learners think that correction

is just related to mistakes instead of giving positive comments to the

students. Indeed, according to the researchers of this study, it might be said

that some teachers tend to relate correction with error-correction instead of

providing positive comments.

Types of Feedback

Nunan (1995),

Brown (2000), and Ur (2006) agree that, at least, there are two levels of

feedback: positive feedback and negative feedback. Furthermore, feedback can be

classified into two types: explicit feedback and implicit feedback. Explicit

feedback is that which is extremely clear and evident and is perceived by the

students. Conversely, implicit feedback is not evident; the student has to

notice it and know how to use it to foster his/her learning.

Sheen (2004) has brought to light an inclusive concept,

which is corrective feedback (CF). According to this author,

“the term ‘corrective feedback’ is used as an umbrella term

to cover implicit and explicit negative feedback occurring in both natural

conversational and instructional settings” (p. 264).

A matter for debate has been the role of CF in second

language acquisition. Some authors like Schmidt (1990, 1992) and Long (1996) claim that negative feedback plays a

facilitative and crucial role in acquisition. Furthermore, Long

believes that from the interaction between the teacher and learners, implicit

negative feedback can give students a chance to pay attention to linguistic

form. This focus, of the learner, on the linguistic forms may foster the

student’s acquisition of the language.

Schmidt (1990, 1992) adds that students should notice

by themselves the space between the interlanguage,

understood by Selinker and Gass

(2008) as “interlanguage transfer is the

influence of one L2 over another” (p. 152), and the target language since

it allows the improvement of the acquisition of the language. However, Krashen (1981), Schwartz (1993), and Truscott (1996) differ

from Long (1996) and Schmidt’s (1990, 1992) beliefs by pointing out that

just positive feedback is enough for students to acquire a second language.

Moreover, they add that there is no sense in using negative feedback and it may

cause damaging effects on the language development.

Ur (2006) compares the role of positive and negative

feedback and states that “It is true that positive feedback tends to

encourage, but this can be overstated [whereas] negative feedback, if given

supportively and warmly, will be recognized as constructive, and will not

necessarily discourage” (p. 257). It is interesting to notice the positive

aspect of negative feedback and the negative side of positive feedback. Indeed,

providing only positive feedback is not advisable because students can think

that they are doing well when they are not. However, negative feedback should

be given in a constructive and warm way.

Writing

Based on Harmer (2003), Musumeci

(1998), Nunan (1995), Olshtain

(2001), and Ur (2006), we point out that writing is the expression and the

association of ideas which can be either in people’s mother tongue or

another language, being the association of ideas the most difficult to

students. The principle idea of any writer is that their piece of work may be

read but, as the reader’s feedback (i.e. comments, opinions) is not

received immediately any piece of writing should include conventions and

mechanical devices to make the reader’s understanding effortless. In

fact, any a piece of writing should have two components: coherence and

cohesion. The first one means that all the ideas in a paragraph flow smoothly

from one sentence to the next, and cohesion refers to the use of transitional

expressions or words to guide readers and show how the parts of writing relate

to one other.

Feedback on Writing

Feedback on writing is the information or comments

given by a reader to a writer in relation to organization, ideas, and writing

mechanics. It is also a useful tool for writers in order to achieve their

purpose, which is to let the readers understand what the writers want to

convey. Furthermore, Ur (2006) notices that content is

the most relevant aspect in a piece of writing because it includes the ideas

and events the writer wants to express.

For this research project, feedback on writing will be

considered as the comments given by the teacher to the students about their

writings/writing tasks. Moreover, it can be concluded that feedback on writing

is an essential element as part of the process approach to writing. The main

purpose of feedback is to provide important information to the writers so they

can use it to modify their mistakes (Ferreira, 2006). Indeed the most important

element in a writing task is content. For that reason, feedback should be given

principally on content and organization instead of on language forms. However,

teachers should correct some language mistakes if and when they really affect

the meaning of the message or if they are basic (Celce-Murcia,

2001; Harmer, 2003; Ur, 2006).

Motivation

Giving explicit feedback is a way that some teachers

use to motivate students to improve; in fact, the research question of this

study (Does explicit feedback, provided in content and organization in writing

tasks, motivate EFL learners?) is related to the motivation that explicit

feedback may cause in EFL learners. Dörnyei

(2001) defines motivation as that which “concerns the direction and

magnitude of human behaviour, that is: the choice of

a particular action, the persistence with it, the effort expended on it”

(p. 8). The author states that motivation is what guides people’s behaviour. Likewise, motivation occurs when the reason or

the will to improve and constant effort are present. In addition, it influences

how people deal with different situations.

In addition, according to Ur (2006), motivation is

classified into two types: extrinsic and global intrinsic motivation.

“Extrinsic motivation is that which derives from the influence of some

kind of external incentive, as distinct from the wish to learn for its own sake

or interest in tasks” (p. 277). Therefore, extrinsic motivation can be

understood as the external stimulus that students receive in order to learn.

This kind of motivation should be provided first by teachers, second by

parents, then by classmates, trying to enhance learners’ performances in

writing, to go beyond the task. In the case of intrinsic motivation, Miller, Benefield, and Tonigan (1993) as

well as Perry (1998) mention that writing tasks that require high levels of

cognitive engagement are related to higher levels of intrinsic motivation and

self-monitoring activities.

Moreover, Brown (2000) agrees with Ur (2006) in the

sense that motivation is a relevant aspect in the learning process. Brown

(2000) thinks that “motivation is a key to learning” (p. 160). In

addition, Brown classifies motivation into three different perspectives: behaviouristic, cognitive, constructivist. The first one is

related to the desire to receive positive reward. The second one deals with the

basic human needs. And the third one has to do with the social context (the

community). Likewise, motivation can be classified as Gardner and Lambert

suggest.

Gardner and Lambert

(1982) distinguish “instrumental motivation,” which occurs when the

learner’s goal is functional (e.g. to get a job or pass an examination),

and “integrative motivation,” which occurs when the learner wishes

to identify the culture of the L2 group. Another kind of motivation is

“task motivation”—the interest felt by the learner in

performing different learning tasks. (Gardner & Lambert as cited in Ellis,

1995, p. 300)

The concept of task motivation, suggested by Gardner

and Lambert, was considered in this research because the motivation towards the

task facilitates its accomplishment.

Finally, Celce-Murcia

(2001), Harmer (2003), and Ur (2006) agree that the essential element in

writing tasks is content, and furthermore, feedback on writing is a vital

constituent inside the process approach. For this reason, although teachers

should correct language mistakes, they should give feedback on content and

organization principally; that is, global errors instead of local errors.

According to Ferris (2002), global errors “are errors concerning overall

content, ideas, and organization of the writer’s argument [and] local

errors refer to minor errors such as grammar, spelling, or punctuation

‘that do not impede understanding’ of a text” (p. 22).

Nevertheless, no matter the kind of feedback provided, students should know how

to use it.

Method

This study is an exploratory qualitative investigation

and the type of research is a descriptive-interpretative one because, from the

description of the phenomenon, some concurrent ideas were identified among the

different sources of information. This research study has action research

characteristics because the participant teachers took part in it actively

during the research with the purpose of gathering information about the

teaching and learning of the writing process of their own classes.

The main objective of this study was to find out how

explicit feedback, focused on content and organization of written messages,

motivates students to carry out writing tasks. The specific objectives

established were to identify the kind of feedback provided by teachers in

writing tasks, to study how important it is for learners to receive explicit

feedback on writing tasks, to analyze students’ motivation to rewrite and

improve a task after receiving explicit feedback and to compare students’

opinions about the importance of receiving feedback and the second written

task.1

Participants

For this research, two groups of participants were

chosen, one of students and another of teachers. The selection criteria were

the following:

(a) Third and fourth year students from a subsidised high school from Concepción, Chile, who

had had English lessons since fifth grade and a regular attendance of 90%.

Their level of English, according to the school teacher, corresponds to lower

intermediate.

(b) Teachers: those having five years of language

teaching experience, belonging to a subsidised

educational system and teaching English in secondary education, at the same

school as the participating students.

With the criteria mentioned, six students and two

teachers were selected, and each of them participated voluntarily.

Data Collection

The data were collected with the use of one structured

interview and a document analysis methodology. The document analysis was

carried out examining a collection of participating students’ writing

tasks, carried out before and during the investigation. The purpose of analysing previous and current students’ written

samples was to identify the kind of feedback provided by the teacher in writing

tasks, to get a general idea of teachers’ knowledge of feedback and to

analyze students’ motivation to rewrite the topic after receiving

explicit feedback. In order to do that, a rubric was given to participating

teachers to guide the feedback they provided in the second writing task.

The structured interview was conducted in the

students’ mother tongue, Spanish. Furthermore, the structured interview

focused on the importance of explicit feedback in writing tasks for learners in

order to understand how motivation affects the quality of a written task.

Data Analysis

During the data analysis, the data were tabulated and

for the purpose of this research, the researchers analysed

the data in each case. Case 1 considered three students and the teacher of subsidised School 1; in Case 2, researchers considered

three students and the teacher of the subsidised

school. The information collected was analysed

through content analysis techniques, which includes the following phases: data

to be analysed were selected, units of meaning or

categories were determined, the properties of these categories were defined and

finally the data were classified in each category.

The document analysis carried out by the researchers

intended to observe and take notes about the different codes and

characteristics that teachers used when giving feedback. The analysis was

carried out according to the feedback categories defined below.

Affective feedback: It is the extent to which we value or encourage a

student’s attempt to communicate (Brown, 2000).

Cognitive feedback: It is the extent to which we indicate an

understanding of the message itself (Brown 2000).

Positive feedback: Positive feedback has two principal functions: to let

students know that they have performed correctly and to increase motivation (Nunan, 1995).

Negative feedback: The teacher’s overall attention towards

mistakes (Brown, 2000).

Neutral: It simply informs the speaker that the message has

been received (Nunan, 1995).

Explicit: It is extremely clear and evident and it is perceived

by the students (University of Cambridge, 2005).

Implicit: It is not evident, the students have to notice it and

know how to improve their performance (University of Cambridge, 2005).

Then, the structured interview was tabulated in order

to study how important it is for learners to receive explicit feedback on

writing tasks. Once the whole data were collected, the analysis was carried out

and the answers were analysed applying content

analysis methodology. After the development of the individual analysis, a

comparative analysis was made in order to see what common aspects and

differences might be observed among the participants.

To analyze students’ motivation to rewrite the

task after receiving feedback, through the writing task, a completely new

writing process was undertaken. First, students wrote an autobiography; second,

the teachers gave feedback on content and organization. Third, the students

rewrote the autobiography. Once students returned the tasks, the researchers

compared the two papers and analysed them in order to

notice which the students’ improvements in the writing tasks were.

Finally, a comparison between Specific Objective 2, To

Know How Important It Is For Learners to Receive Explicit Feedback in Writing

Tasks; and Specific Objective 3, To Analyze Students’ Motivation to

Rewrite and Improve a Task After Receiving Explicit Feedback, was carried out

with the purpose of corroborating if they were consistent between what they

manifested in the structured interview and what they produced in the writing

task after receiving explicit feedback.

Findings

Objective 1: To

Identify the Kind of Feedback Provided by the Teacher in Writing Tasks

This analysis was based on the following categories:

affective feedback, cognitive feedback, positive feedback, neutral feedback,

negative feedback, explicit feedback, and implicit feedback. Two teachers were

compared for this analysis.

To analyze each case, the information in Table 1 was used for the purpose of classifying each teacher

in the categories that most represent them.

Both teachers give explicit negative feedback because

they indicate where the mistake is, especially in grammar and spelling. To

support the teachers’ way of giving feedback, Ur (2006) mentions that

giving only positive feedback may not have a positive impact on students

because they can think that they are doing well when they are not. Besides,

this author states that negative feedback can be constructive if it is given in

a supportive and kind manner. However, there is one teacher who provides

positive explicit comments while the other gives the correct answers.

Otherwise, both teachers provide cognitive feedback because they understand what

students want to express. Nevertheless, there is one teacher that gives

affective feedback because the teacher praises students to persist in doing the

task.

In Table 2 it can be observed

that the teacher marks in red and uses codes for grammar and spelling.

Moreover, the participating teacher uses criteria such as requirements (name,

author of song, reason), spelling, grammar, and vocabulary. Also, the teacher

writes the correct version of the mistake. However, the teacher neither writes

comments nor gives a mark but indicates the score. Nevertheless, it is

important to mention that the teacher has other ways to mark the mistakes like

underlining, question marks, and parentheses. After observing the feedback

provided by the teacher, one can notice that the teacher gives feedback mainly

based on negative aspects.

In this case, the teacher’s tendency is to

provide explicit negative feedback because the teacher marks all

students’ mistakes and giving the correction of the mistake could be

considered as supportive since the teacher wants to show the students what the correct

answer is. Otherwise, it is important to mention that the teacher marks in red,

which could be interpreted as if the participating teacher were stigmatising mistakes. In this analysis, there is no

evidence of positive and neutral feedback. There is no proof of affective

feedback. Nonetheless, since the teacher responds to the student’s

message, it could be inferred that there is cognitive feedback because the

teacher understand students’ ideas.

In Table 3 below, it can be seen

that the teacher marks in red. Moreover, the participating teacher provides the

correct answer. Also, the teacher gives comments and suggestions about content.

Besides, the teacher provides the final mark but not the points awarded for the

task. It is relevant to realize that the teacher corrects the mistakes in other

ways. For example, the teacher adds punctuation and crosses out extra words.

Also, the teacher circles mistakes and wrongly-used words.

In this case, the teacher provides explicit feedback

and both positive and negative feedback because the teacher gives positive

comments and marks the mistakes. The teacher also provides cognitive and affective

feedback. It is affective as the teacher gives positive comments which

encourage students to continue writing. It is cognitive because the teacher

understands the message and reacts. The teacher reacts with comments and by

correcting the mistakes.

Objective 2: To

Know How Important It Is for Learners to Receive Explicit Feedback in Writing

Tasks

Relating to the importance of receiving explicit

feedback for learners in writing tasks, a structured interview was applied. The

objective of this interview was to learn students’ opinions and

preferences about receiving feedback. For this reason, six questions were

designed. These were in the students’ mother tongue, Spanish, as the

purpose was to learn students’ opinions instead of measuring their level of

English. The analysis is separated into two case studies.

In general, it is important for the students to

receive explicit feedback on writing tasks, because they can improve their

linguistic competence. It is important to mention that students prefer receiving

feedback in Spanish in order to understand better the teacher’s comments.

Moreover, most of them prefer receiving feedback from their classmates because

they trust them. There are three students who prefer receiving feedback from

the teacher too since the teacher’s comments help them to avoid making

the same mistakes. Furthermore, students like oral and direct feedback in

general. However, two of them prefer written feedback because this way they can

avoid speaking to the teacher in English. In addition, another student points

out that since she does not understand feedback in English, she cannot improve

her writing. Table 4 shows some of the evidence commented

on.2

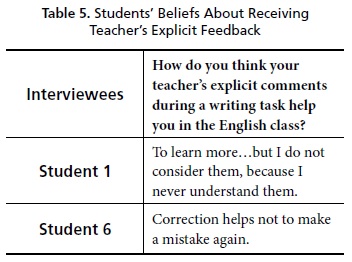

Some students report that the explicit comments made

by the teacher help them. But, in general, students say that they do not

understand comments in English because of their low level of competence. Nevertheless,

one of the interviewees manifests that comments help

her to improve grammar aspects and ideas as can be found in Table

5.

Question 3 was conducted to learn of students’

perception towards how the explicit feedback provided by the teacher helped

them when they did the writing task in the English lesson.

The tendency is that all of the students mention that

receiving feedback from their teachers helps them to avoid making the same

mistakes and helps them feel more confident. There is one student who says

that, in spite of the teachers’ comments being important, s/he does not

pay attention to them.

In relation to the feedback provided by the teacher,

the students said that they do not like receiving feedback since they feel

uncomfortable and because the teacher just explains once. However, one student

did not say anything about the last point. Students’ answers are

illustrated in Table 6.

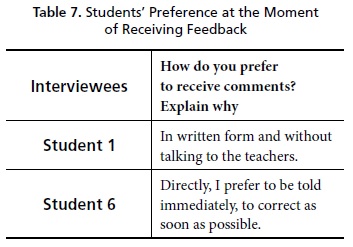

In Table 7 one of the students

manifests that she likes receiving written feedback as that way she avoids

speaking with the teacher. And some other interviewees mention that they like

receiving instant feedback.

Objective 3: To

Analyze Students’ Motivation to Rewrite and Improve a Task After Receiving Explicit Feedback

Two cases were analyzed. The results were analyzed

under three categories related to the writing assessment: emergent categories

(length of message), predetermined categories (content: improvement of ideas

and organization: logical sequence of ideas and structured paragraph), and

predetermined categories by participating teachers (use of linking words,

neatness, and grammar and spelling).

It is important to mention that all the students

re-wrote their task. In general, according to the category of length of message, it might be said that

some students shortened the pieces of writing. However, two students increased

the length of the autobiography. For example, Student 4 had 96 words in the

first piece of writing and then 155 words after receiving feedback from the

teacher.

In terms of content:

improvement of ideas, most of the students kept the same ideas and two

learners improved them. This happened because the students who did not add new

ideas after the feedback provided were those who had well organized ideas in

the first task. However, there was a student who did not write more ideas as

she did not understand the feedback provided by the teacher. The two students

who improved their ideas did so because the teacher suggested it. For example,

Student 1’s original writing (before receiving feedback) was about his

opinion of a famous character; the feedback of the teacher pointed to the title

(If you were Leonardo Da Vinci, How would your days be like), then said:

“You were asked to write your biography and not his, nor

your opinion about him.” In the student’s second writing (after

receiving feedback), he starts: “I’m Leonardo Da Vinci I was boiring [sic] in

1440.”

In the category of organization:

logical sequence of ideas and structured paragraph, the majority of the students

had logical sequences of ideas. These were mainly in chronological order

because the task was to write an autobiography. For instance, Student 5 started

talking about her parents, then about her childhood; after that, about her

career and finally, she talked about the present. Also, students had well

balanced paragraphs; they had almost the same number of lines per paragraph.

However, two students had unequal paragraphs because these did not have a

similar number of lines.

In relation to the use

of linking words, there was evidence that all the students used them

correctly in general, even though they utilised only

a few of them which were the common ones such as so, and, since. To exemplify this, Student 5 used

the following linking words such as so, and, when, which were correctly used.

With regard to the category of neatness, all students wrote neat pieces of writing. They used

legible hand-writing and the writing task was well presented. For example,

Student 6 had a clear piece of writing, with legible hand-writing and a

well-presented writing task as well. It is important to mention that one

student largely improved the neatness of the piece of writing and this

improvement contributed to the understanding of the writing process.

Finally, in the category of grammar and spelling, it was evident that students improved their

grammar and spelling, making fewer mistakes in general. For instance, Student 6

corrected several grammar mistakes which had been indicated by the teacher.

This occurred because the teacher, when giving feedback, provided the correct

version of the mistake. However, only one student did not follow the

teacher’s feedback and kept the same mistakes.

It might be concluded that most of the students

carried out the task correctly. However, two students did not follow the

instructions of the writing task, thus they did not write an autobiography.

Most of the students felt motivated to re-write the task. Furthermore, they

improved their writing after receiving the explicit feedback provided by the

teacher. The students incorporated the comments provided by the teachers,

especially on content and grammar and spelling. Nevertheless, there was one

student who did not improve her writing in any category; this student declared

that she did not understand feedback provided in English.

Objective 4: To

Compare Students’ Opinions About the Importance of

Receiving Feedback and the Second Written Task

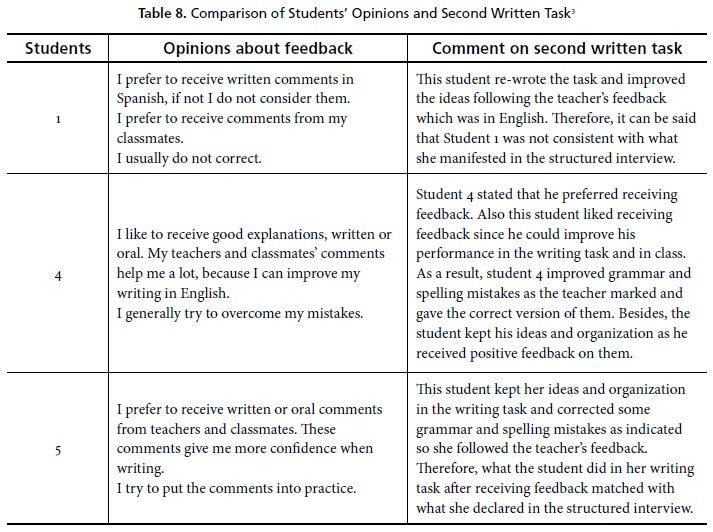

As Table 8 shows, most of the

students were consistent between what they declared in the structured interview

and what they did after receiving feedback. However, there was only one student

who was inconsistent because she said that she did not consider feedback in

English since she did not understand it. However, she incorporated the feedback

provided by the teacher in her writing.3

Conclusions

Throughout the whole process the researchers have

tried to find out whether explicit feedback, provided on content and

organization in writing tasks, motivates EFL learners. In order to have a logical

sequence of conclusions, this section will be organized by the specific

objectives and their corresponding hypotheses.

According to the study of the document analysis of the

two case studies provided by participating teachers, we can conclude in general

that teachers do not give feedback on content and organization systematically

or that they are not aware of it and give it unconsciously. In fact, it can be

interpreted that neither students nor teachers have a culture of feedback.

However, teachers know how to assess error correction in writing tasks as they

specifically pay attention to local errors. Ur (2006) mentions that giving only

positive feedback may not have a positive impact on students because they can

think that they are doing well when it is not so. Besides, this author states

that negative feedback can be constructive if it is given in a supportive and

kind manner. For that reason, it is important to mention what Harmer (2003)

states about the role of feedback which is not only to correct students, but

also offer assessment on their performance.

Through the data analysis the researchers may conclude

that when giving feedback, participating teachers provided feedback that could

be classified in these categories (use of

linking words, neatness, grammar and spelling). Some of them are

considered basic categories in the process of writing by practitioner

researchers, but what was intended was to go one step forward and demand the

students’ best efforts in terms of content,

logical sequence of ideas, and structured paragraphs.

What could be observed in the structured interview, in

terms of students’ opinions, is that in general students like receiving

explicit feedback in order to improve their written tasks. Furthermore,

students said they preferred to receive feedback from their partners. This is emphazised by Gattegno (as cited

in Nunan, 1995), who recognises

the importance of the establishment of a consistent relationship between

teachers and students. In addition, Harmer (2003) states that written feedback

influences students’ final products and also orients students’

writings. The direct relation between students’ opinions about feedback

and their improvement in writing tasks is also evident.

After the document analysis of the writing task, we

can conclude that the kind of feedback provided by teachers does impact on

students’ motivation, in fact, it was demonstrated that students improved

their pieces of writing in the following categories: content: improvement of ideas, grammar

and spelling. Moreover, there is a relation between categories of length of message and grammar and spelling. And in relation to

the category of organisation

students do not have problems.

The relationship between teachers and students also

has an impact. For instance, teachers can create significant learning through

giving the appropriate feedback. On the contrary, Brown (2000) says that

negative cognitive feedback can cause students to perceive that their writings

are totally bad and they will feel frustrated.

In addition, the assumptions proposed by the

researchers were confirmed. The first one, which was related to learners’

improvement in writing tasks after receiving explicit feedback on content and

organization from teachers, was confirmed. This is evidenced in both cases in the

data analysis chapter as students improved their ideas and organization. The

second one, related to positive changes in learners’ attitude towards the

writing task after receiving explicit feedback on content and organization, was

also successfully confirmed. It can be verified since the majority of the

students re-wrote and improved the task incorporating the comments given by the

teachers because they felt motivated.

The comparison between students’ opinions about

the importance of receiving feedback and the re-written task, once they had

received feedback on content and organisation, showed

that most of the students’ opinions were consistent with what they stated

in the structured interview and what they did after receiving feedback on the

writing task.

To sum up, it might be concluded that explicit

feedback motivates EFL learners as they become aware of their writing process

by knowing their strengths and weaknesses. This demonstrates the impact of

providing feedback to EFL students which then leads them to improve their

writing. Nevertheless, if corrections do not happen, learners cannot modify

their mistakes.

1 The re-written task after receiving feedback on

content and organisation.

2 Questions and excerpts have been translated from

Spanish.

3 Students’ opinions have been translated from

Spanish.

References

Aparicio, N. (2007). Monitoring, error correction, and giving

feedback [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://www.slideshare.net/jema/monitoring-error-correction-and-givimg-feedback

Brown, H. D. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching. New York, NY:

Addison Wesley Longman.

Celce-Murcia, M. (2001). Teaching

English as a second or foreign language. New York, NY: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Teaching and

researching: Motivation. London, UK: Longman.

Ellis, R. (1995). Understanding

second language acquisition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Ferreira, A. (2006). Estrategias efectivas de feedback positivo y correctivo en el español como lengua

extranjera [Effective positive and corrective

feedback strategies in Spanish as a foreign language]. Signos, 39(62), 379-406.

Ferris, D. (2002). Treatment

of error in second language student writing. Ann Arbor, MI: The

University of Michigan Press.

Harmer, J. (2003). The practice of

English language teaching. London, UK: Longman.

Krashen, S. (1981). Second language

acquisition and second language learning. Los Angeles, CA: Pergamon Press.

Long, M. H. (1996). The role of the linguistic

environment in second language acquisition. In W. C. Ritchie & T. K.

Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of Second

Language Acquisition (pp. 413-468). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Miller, W. R., Benefield, R.

G., & Tonigan, J. S. (1993). Enhancing motivation for change in

problem drinking: a controlled comparison of two therapists’ styles.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology, 61(3), 455-461.

Musumeci, D. (1998). Writing in the

foreign language curriculum: Soup and (fire)crackers.

Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED433725)

Nunan, D. (1995).

Language teaching methodology: A textbook

for teachers. London, UK: Prentice Hall.

Olshtain, E. (2001). Functional tasks for mastering the mechanics of writing and

going just beyond. In CelceMurcia

(Ed.), Teaching English as a second or

foreign language (pp. 207-217). Boston, MA: Heinle

& Heinle.

Perry, C. (1998). A structured approach to presenting theses: Notes for

students and their supervisors. Australasian

Marketing Journal, 6(1), 63-86.

Schmidt, R. (1990). The role of consciousness in

second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 11(2), 129-158.

Schmidt, R. (1992). Awareness and second language

acquisition. Annual Review of

Applied Linguistics, 13, 206-226.

Schwartz, B. (1993). On explicit and negative data

effecting and affecting competence and linguistic behavior. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 15(2),

147-163.

Selinker, L., & Gass, S. (2008). Second language acquisition: An introductory

course. New York, NY: Routledge.

Sheen, Y. (2004). Corrective feedback and learner

uptake in communicative classrooms across instructional settings. Language Teaching Research, 8(3),

263-300.

Truscott, J. (1996). The case against grammar

correction in L2 writing classes. Language

Learning, 46(2), 327-369. University of Cambridge ESOL

Examinations (2005). Teaching knowledge test,

glossary. Cambridge, UK: Author.

Ur, P. (2006). A course in

language teaching: Practice and theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

About the Authors

Roxanna Correa

Pérez, B.A. English Teaching,

University Teaching Diploma, and M.A. in Higher Education, from Universidad Católica de la Santísima

Concepción (Chile) and CertTESOL (Sussex

University, Trinity College of London). She teaches Methodology in the English

Pedagogy Program at Universidad Católica de la

Santísima Concepción, Chile, where she

has also been Head of the English Pedagogy Program and Curriculum Advisor.

Mariela Martínez Fuentealba, EFL Teacher graduated from Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción

in Chile. Nowadays, Mariela is working

at a public high school in a small city where she teaches English and organizes

different activities to encourage students to use the language.

María Molina De La Barra, graduated in Secondary English Education from Universidad

Católica de la Santísima Concepción, Chile, in 2010. Nowadays, María is

working at a public high school in Concepción, Chile, where she teaches

English.

Jessica Silva Rojas, English Teacher

graduated from Universidad

Católica de la Santísima Concepción in Chile. After her graduation, she started to work in different

types of schools and after a year, moved to the USA. There, she worked in the

SPLASH Program in Elon Elementary School. Nowadays,

she is working with an ONG giving English lessons.

Mirta Torres Cisternas, graduated from Universidad

Católica de la Santísima Concepción, Chile, in 2010 as an EFL teacher. After a year of working at the high school level, she

started teaching socially deprived students (from 2011 to the present) at the

elementary level.