Formal Grammar Instruction: Theoretical Aspects to Contemplate Its

Teaching

Instrucción

formal de la gramática: aspectos teóricos para considerar su

enseñanza

Carolina

Cruz Corzo*

Universidad de La

Sabana, Colombia

*carolina.cruz@unisabana.edu.co

This article was received on July 1, 2012, and

accepted on April 14, 2013.

With the rise of new tendencies and methodologies in

the English as a foreign language field, formal grammar instruction has become

unnecessary during the last few years. Institutions and educators have made

serious decisions in order to promote a language production which is fluent and

coherent. Thus, grammar instruction has been partially relegated and new trends

have occupied its place. However, based on personal teaching practices, I have

realized that some learners are producing the foreign language in a fluid, but

sometimes inaccurate form. The present reflection is aimed at presenting some

insights for educators that may help them consider the possibility of teaching

formal grammar as part of the curriculum.

Key words: Explicit grammar

instruction, grammar instruction, implicit grammar instruction.

Con el crecimiento

de nuevas tendencias y metodologías en la enseñanza del

inglés, la instrucción formal de la gramática se ha vuelto

innecesaria durante las últimas décadas. Instituciones y

educadores han tomado serias decisiones con el fin de promover una

producción fluida y coherente de la lengua extranjera, lo que ha

generado que la enseñanza formal de la gramática sea relegada de

manera parcial y nuevas tendencias ocupen su lugar. Con base en mis propias

experiencias dentro del aula de clase, he observado que algunos de mis

estudiantes se comunican fluidamente en la lengua extranjera, pero en

ocasiones, de manera incorrecta. En este artículo de reflexión se

presentan algunos elementos teóricos que podrían ayudar a

educadores de lengua extranjera a considerar la posibilidad de incluir la

enseñanza formal de la gramática en el currículo.

Palabras clave: enseñanza

de la gramática, enseñanza explícita de la

gramática, enseñanza implícita de la gramática.

Introduction

The teaching of explicit grammar as part of the

foreign language learning process is an aspect that has been debated for so

many years. Schulz (2001) affirms that “foreign language educators and

applied linguists examining the effectiveness of various approaches for FL

teaching are not all in agreement about whether explicit grammar instruction .

. . is essential or even helpful in learning a new language” (p. 245). In

addition, authors like Terrell (1991), Norris and Ortega (2002), and Ellis

(2006), to mention some, have considered and supported the idea of Explicit

Grammar Instruction (EGI) in the foreign language class, whereas theoreticians

such as Krashen (2003) have defended the idea of avoiding EGI since it may

interfere with a natural acquisition process.

Thus, the approaches implemented in the language class

have varied throughout the years and educators are still looking for the best

option to guarantee an optimal learning process. In the United States for

example, educators have applied current teaching tendencies to achieve the

previously mentioned goal. Terrell (1991) explains this language teaching

evolution by stating:

The role of English

Grammar Instruction in a second/foreign language class in the United States has

changed drastically in the last forty years as the favored methodology changed

from grammar-translation to audio-lingual, then from audio-lingual to

cognitive, and finally from cognitive to communicative approaches. (p. 53)

However, this phenomenon has not only occurred in developed

countries such as the United States. Colombian education has also changed in

the last few years and English Foreign Language (EFL) teaching has not been the

exception to this phenomenon. Language teachers and researchers have been

looking for the specific criteria, methodology, and appropriate approaches that

would help them enhance English teaching. Some decades ago, Colombian teachers

used to place emphasis on the teaching of grammatical forms but, interestingly,

some educators have recently claimed that this methodology was not helpful for

producing spontaneous and authentic language since its main focus was related

to the production of accurate linguistic forms where communication or

interactional situations did not play a primary role. Nassaji

and Fotos (2004) support the previous statement by explaining that “with

the rise of communicative methodology in the late 1970s, the role of grammar

instruction in second language learning was downplayed, and it was even

suggested that teaching grammar was not only unhelpful but might actually be

detrimental” (p. 126). Nonetheless, it is relevant to bear in mind that

the teaching of explicit grammar forms has not been completely relegated and is

still taking place in many EFL settings. Nowadays, some educators still believe

that the formal teaching of linguistic forms is significant in the development

of a foreign language and they also may implement this practice as a complement

to teaching the language as a whole.

Similar to the language teaching evolution lived in

the United States (Terrell, 1991), new forms to teach

a foreign language started to grow in Colombian classrooms and, apparently,

these started becoming effective. Thus, by moving from audio-lingual and

grammar-based methods to more communicative approaches, language educators have

evidenced that learning a language is a process that requires constant update

in order to achieve the expected goals and necessities of their populations.

Bearing in mind the aforesaid teaching development,

Colombian educators are regularly looking for methods to promote the most

appropriate language teaching methodologies that help educators create

bilingual individuals who may be able to produce an accurate and fluid foreign

language. Consequently, some institutions are attempting to implement new

bilingual methodologies or approaches such as task—or content—based

programs with the purpose of providing learners with a wider range of

opportunities to experience and learn a foreign language in more authentic or

meaningful ways.

In general, I would assert that Colombian education is

moving forward to become an outstanding bilingual model; however, even though

the abovementioned approaches are expected to be successful, I personally

believe that learning a foreign language is a process that not only requires

natural and bilingual models, but also needs the development of linguistic

accuracy that will allow learners to produce the language in a standard and

coherent form.

Even though language teachers and institutions have

made a big effort to move from traditional to more communicative and meaningful

approaches in the EFL field, and although there has been a constant evolution

in the methodologies implemented in this area, some populations are still not

achieving the final aim: producing the language with fluency and accuracy. This

is evidenced by a study carried out by the Ministry of Education in 2005, whose

final results showed that only “6.4% of students finishing high school

performed in English at an intermediate level, whereas an overwhelming 93.6%

did so at a basic. No students were found to perform at an advanced level”

(Macías, 2011). Equally, the results obtained

in ICFES exams in the last seven years not only evidenced low performance from

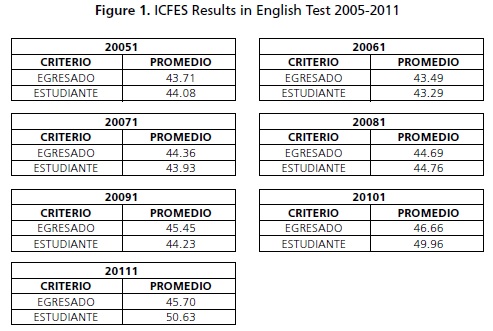

learners but also a minimal increase in this area (see Figure 1).

The data in Figure 1 evidences

that even though a variety of methodological changes have been implemented to

enhance the results obtained in a teaching-language process, Colombian students

are still having difficulty in this area. Thus, a personal question arises: If

new trends and approaches are implemented every day in order to help learners

become bilingual, why are Colombian students still not achieving the expected

goals?

From my personal teaching perspective while working

with young adults, I have realized that sometimes linguistic forms are not

promoted explicitly since they may restrict the production of fluent and real

language (Krashen, 2003). Likewise, I have faced classroom situations in which

learners are able to communicate fluently in the foreign language,

however their accuracy is not without its flaws. Considering language learning

theories, a foreign language is expected to be learned following the same

process of the first language and formal grammar instruction should be kept

away (Krashen, 2003), but is it the best way to help our students, who may need

to use L2 for professional purposes, become bilingual individuals?

The two previous questions made me reflect on the

possibility of including formal grammar instruction in the foreign language

class as part of a process in which language should be seen as whole and used

with fluency and, most importantly, with accuracy. In the following section, I

present a theoretical overview in which not only the teaching of linguistic

forms is suggested, but also presents the most appropriate time and techniques

in which it should be incorporated into the EFL curriculum.

Formal

Grammar Instruction: A Theoretical Overview

The most recent approaches for second and foreign language

teaching have principally been focused on meaning and the way language is

developed naturally and as a whole. Considering my experience as a foreign

language teacher, I have observed educators who have decided to employ more

communicative and authentic approaches in order to help individuals develop

competences in order to be able to use the second or foreign language in real

and spontaneous forms. Interestingly, these approaches have replaced the

teaching of explicit grammar for an implicit method in which accuracy is

learned naturally with no pressure or excluding formal instruction. This idea

is supported by the second language acquisition theory (Krashen, 2003), which

explains that formal instruction of grammatical structures should not be taken

into account in language acquisition considering the fact that human beings

learn to understand and produce their first language through natural and

informal communicative contexts.

Krashen (2003) argues that grammar instruction has no

role in second language acquisition. The author explains that language is

acquired as a subconscious process, and he states that conscious learning can

only be considered as a monitor device to correct sentences when the individual

has already produced them. Krashen’s theory not only places emphasis on

self-correction but also suggests that formal instruction does not contribute

to fluency: “While monitoring can make a small contribution to accuracy,

the research indicates that acquisition makes a major contribution. Thus, acquisition is responsible for both fluency and most of our

accuracy” (Krashen, 2003, p. 2). Clearly, Krashen’s theory

is not in accordance with the teaching of explicit grammar in second language

acquisition, but there are other theoreticians and linguists who have defended

opposite ideas.

Even though I personally am a devoted follower of

communicative approaches and virtual environments due to their innovation and

realistic form to focus on language teaching, I have regularly wondered about a

missing ingredient to help my students use the language not only fluently but

also accurately. As a result of my personal teaching disquiet, I found other

perspectives regarding formal and explicit grammar instruction which provided

me with a positive view and therefore helped me change my viewpoints about grammar

as an antiquated teaching practice.

Ellis (2006), for example, resorts to various

researchers including Long (1983) and Norris and Ortega (2002) to support his

idea of the importance of including explicit grammar in a second language

acquisition process. The author explains that grammatical deficiencies may

cause a breakdown in communication and interfere with an intended message,

therefore, it is understood that language learners need to speak fluently, but

they also need to speak accurately. Similarly, and based on the importance of

speaking a standard language which is clear and coherent to the recipient, it

can be suggested that explicit grammar instruction is essential in second

language acquisition.

Correspondingly, Richards (2002) affirms that

grammar-based methodologies have been replaced by communicative approaches

which give more importance to fluency than to accuracy. Due to this phenomenon,

the teaching of grammar has been isolated from language acquisition and is

causing a major issue. Students who are encouraged to speak for communicative

purposes focus their speech on meaning regardless of grammatical accuracy.

Nevertheless, there are grammatical mistakes that can change meanings and

consequently interfere with communication. Richards (2002) explains that there

is a grammar-gap problem in the development of linguistic competence and he

affirms that “what has been observed in language classrooms during

fluency work is communication marked by low levels of linguistic accuracy”

(p. 38). Considering linguistic competences, some feel that language is

supposed to be used naturally, but natural approaches promote students’

participation in communicative tasks that may have resulted in

“communication that is heavily dependent on vocabulary and memorized

chunks of language” (Richards, 2002, p. 39).

The teaching of linguistic forms is not only supported

by theory but also by studies recently conducted. For instance, Norris and

Ortega (2002) have analyzed different studies in which it is demonstrated that

teaching grammar is appropriate and that it may make a difference in the

results obtained in the language learning process. Based on the study conducted

by these authors, Ellis (2002) explains that “not only did Form Focused

Instruction make a difference but also that it made a very considerable

difference” (p. 223) and concludes that there is “ample evidence to

show that form-focused instruction (FFI) has a positive effect on second language

(SL) acquisition” (p. 223).

The assumptions presented above are not the only ones

that contradict Krashen’s view towards grammar instruction. For instance,

Long and Robinson (1998) are certainly in favor of teaching grammar stating

that “formal instruction helps to promote more rapid L2 acquisition and

also contributes to higher levels of ultimate achievement” (p. 18). They

theorize that grammar not only contributes to the development of accuracy, but

it also has a beneficial effect on acquisition of L2. Equally, Ellis and Fotos

(1999) argue that formal grammar instruction can have a positive impact on

acquisition when grammatical structures are shown in context. The authors state: “formal instruction may work best in

promoting acquisition when it is linked with opportunities for natural communication”

(p. 20).

Furthermore, Ellis (2006) has resorted to previous

research in language acquisition in order to find a clear answer related to

grammar teaching. He explains that “some researchers have concluded that

teaching grammar is beneficial, but to be effective it needs to be taught in a

way that is compatible with the natural processes of acquisition” (p.

85). In this way, it is evident that there is sufficient relevant research to

indicate that grammar is worth teaching, but the natural order in which

learners acquire it should be respected.

In brief, and based on the theory previously

presented, it is clear that grammar instruction can be implemented in foreign

language classes but a major recommendation is to bear in mind specific factors

or variables such as students’ age, proficiency level, or needs and goals

they may have (Nassaji & Fotos, 2004).

Accordingly, the following section includes some important aspects to consider

when making the decision of including grammar instruction when planning foreign

language lessons.

Formal

Grammar Instruction: How, Where, and When

In the previous section, the importance and relevance

of including grammar in the foreign language class were discussed and it was

concluded that the teaching of grammar forms are worth teaching. However,

educators might need to make decisions regarding the most effective techniques

and moments to include this aspect in their lessons. Before starting to answer

questions regarding the how, where, and when of incorporating linguistic forms

in the foreign language class, it is relevant to take a closer look at the

definitions or expectations regarding grammar teaching. Ellis (2006) presents

an interesting definition in which he asserts that it “involves any instructional

technique that draws learners’ attention to some specific grammatical

form in such a way that it helps them either to understand it

meta-linguistically and/ or process it in comprehension and/or production so

that they can internalize it” (p. 84). Similarly, Celce-Murcia (1991)

explains that “if learners are presented with many fully illustrated and

well-demonstrated examples and then asked to describe other similar situations,

they have a basis for understanding and practicing the correct use of these

forms” (p. 467).

Bearing in mind the previous characteristics which can

be considered when presenting linguistic forms in a foreign language

environment, one can be state that EGI can be implemented in language classes

by taking into account, as previously suggested, its significance and

usefulness to learners.

How Should Grammar

Be Presented?

Besides the concern about the use of formal grammar

instruction in foreign language learning, it is also relevant to be acquainted

with the most appropriate grammar techniques in order to present grammatical

structures to language learners. Many educators may have been concerned with

the idea of teaching grammar explicitly in their classes since they could

acquire a teacher-centered perspective where students do not have an active

participation. For instance, Blaauw-Hara (2006)

explains that grammar teaching is visualized as a negative technique where

“the teacher lectures on grammatical concepts, diagrams sentences on the

board, or gives a quiz” (p. 166) and unfortunately, many foreign language

educators share this same viewpoint and they may see grammar as a boring and

meaningless process where learners acquire isolated grammar forms that are

rarely produced in authentic conversations.

However, grammar instruction can be presented from

different perspectives in which learners play a more dynamic role and become

active participants of their language learning process. To begin with, using

guessing or discovery techniques is an opportunity for students to identify and

understand linguistic forms on their own that can be used later in context;

secondly, applying practice activities allows participants to put the language

learned into practice; and lastly, using presentational techniques in which

practice is not required but the full attention of learners is necessary

(Ellis, 2006). In addition, Brown (2007, p. 421), who has summarized the

research of various linguists, explains that grammar can be included in the

language class if the appropriate techniques are used. The author summarizes

five important characteristics as follows:

• forms that are embedded in meaningful, communicative contexts,

• forms that contribute positively to communicative goals,

• forms that promote accuracy within fluent, communicative language,

• forms that do not overwhelm students with linguistic terminology,

and

• forms that are as lively and intrinsically motivating as

possible.

In addition, there is a wide range of possibilities in

which to present grammar. For instance, Brown (2007) proposes charts as a

useful tool for clarification, the use of authentic objects to engage learners,

maps and drawings used as visual aids, dialogues for students to practice

linguistic forms in context, and written texts to process selected forms.

Considering the previously mentioned aspects, teachers

can propose a variety of activities and techniques in order to present explicit

forms which, according to linguists such as Fotos (1994), Celce-Murcia (1991),

and Ellis (2006), if used and presented appropriately, become essential to the

learning process. In general, grammar can be seen as an aspect that can be

included and presented in a variety of forms in which students are expected to

use the language in context and with the intention of developing an accurate

production.

When Should Grammar

Be Presented?

The second question regarding the most appropriate

time to present linguistic forms in the language class is related to the

proficiency level of the learner. Brown (2007), for example, explains that

grammar focus at beginning levels may block acquisition or fluency skills and

asserts that “research agrees that at the intermediate to advanced

levels, a more explicit focus on form is less likely to disturb communicative

fluency, and can assist learners in developing accuracy” (p. 422).

Likewise, Ellis (2006), who has evaluated the most influential theories

concerning the teaching of grammar in second language acquisition, proposes

grammar instruction to those individuals who have already acquired an

intermediate level of English. He explains that it is recommended to

“emphasize meaning-focused instruction to begin with and introduce

grammar teaching later, when learners have already begun to form their interlanguages” (p. 90).

Ellis (2006) bases this assumption on previous

research in immersion programs where students are able to develop both fluent

and proficient communication without formal instruction. The results suggest

that grammar should be presented later in order to develop grammatical

accuracy. In general, the author proposes to teach “explicit grammatical

knowledge as a means of assisting subsequent acquisition of implicit

knowledge” (p. 102). In the same vein, Lightbown (2004) agrees with

Ellis’ suggestion explaining that “some linguistic features are

acquired incidentally without intentional effort, conscious awareness or

teacher’s guidance” (p. 75). This statement refers to the teaching

of grammar as a mechanism to enhance features that need to be developed with

formal instruction. In consideration to the explanations offered before, it can

be concluded that grammar should certainly be incorporated in language

curriculum, but it is advisable to be presented to those individuals who need

or are prepared to receive formal grammatical instruction in the second or

foreign language.

What Kind of

Grammar Instruction?

Thus, the final question regarding EGI is related to

the most appropriate manner for incorporating it into the foreign language

class. First, it is relevant to identify the differences between extensive and

intensive grammar teaching; the former refers to the teaching of a specific

grammatical structure during a continued period of time, whereas the latter

refers to a variety of grammatical structures that are presented in a shorter

term. Once again, Ellis (2006) provides relevant information to compare these

two types of instruction. The main characteristic of intensive grammar

instruction is the opportunity that is given to the learner to put into

practice what s/he has learned. Therefore, this type of instruction is

presented with drills and task opportunities to practice the target structure.

Conversely, extensive grammar teaching should be developed within learning

activities that may be focused either on form or meaning. Finally, the author

provides a definite answer about these types of grammar teaching:

“Learning grammar is best conducted using a mixture of implicit and

explicit feedback types that are both input based and output based” (p.

102).

Besides an extensive and intensive focus, explicit and

implicit instruction can be considered. The former refers to a conscious mental

process learners need to overcome in order to internalize grammar rules and later

put into practice. Ellis (2010) explains that through explicit grammar

instruction learners are:

Encouraged to develop metalinguistic awareness of the rule. This can be achieved deductively, as when a rule is

given to the learners or inductively as when the learners are asked to work out

a rule for themselves from an array of data illustrating the rule. (p. 4)

On the contrary, implicit instruction is aimed at

promoting a further thinking process where learners infer and deduce the rules

and accurate use of the language. Thus, Ellis (2010) explains that

“implicit instruction is directed at enabling learners to infer rules

without awareness. Thus it contrasts with explicit instruction in that there is

no intention to develop any understanding of what is being learned” (p.

4).

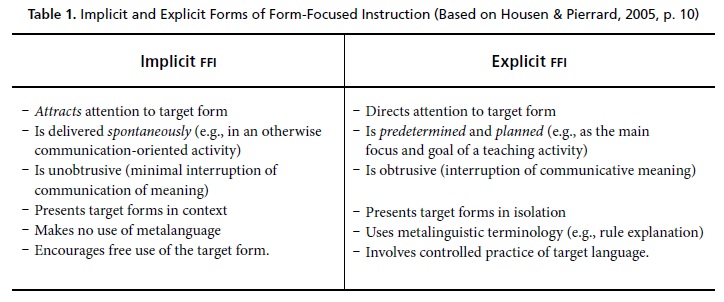

Additionally, Housen and Pierrard (2005) present a clear differentiation between

explicit and implicit instruction (see Table 1).

Table 1 offers an interesting

perspective that can be considered when making decisions regarding the most

appropriate type of instruction to present grammar. However, it is important to

bear in mind that educators need to have a clear focus and intention when

deciding on the type of instruction to be implemented since students respond to

the instructions accordingly (Ellis, 2010).

Decisions on whether to use an implicit or an explicit

focus have also been a controversial issue. Some educators prefer to use an

implicit methodology since it invites students to deduce grammar uses and

structures on their own whereas others prefer the idea of being explicit and

help learners to develop awareness on the uses of linguistic forms. Norris and

Ortega (2002) offer an explicit answer by stating “that focused L2

instruction results in large target-oriented gains, that explicit types of

instruction are more effective than implicit types, and that Focus on Form and Focus

on Forms interventions result in equivalent and large effects” (p. 417).

In addition to the types of instruction discussed

previously, Long and Robinson (1998) present two main options to be considered

in language teaching: focus on forms and focus on meaning. The authors explain

focus on meaning as an incidental or implicit learning that is sufficient for

successful second or foreign language acquisition. Analytic approaches such as

natural, communicative, and immersion are the best representation for this

method. On the contrary, synthetic methods such as audiolingual,

grammar translation, and total physical response give specific emphasis to

grammatical structures that are not usually presented in context; it means

these approaches are mainly focused on forms. The decision about how grammar

should be taught in language teaching should be made based on learners’

needs. However, taking into account previous research, neither fluency nor

accuracy must be separated, but should be integrated and developed

concurrently.

Conclusions

Founded on relevant research and theory, a final

conclusion about the teaching of formal grammar instruction can be provided.

Certainly, language acquisition is a process that requires informal and natural

input (Krashen, 2003), but research has demonstrated the significance of

grammar instruction in foreign language learning and second language

acquisition that serves not only to develop a fluent, but also an accurate use

of language. Consequently, it has been corroborated that explicit grammar

instruction can be presented to learners who have already acquired an

intermediate level of language by integrating extensive and intensive

approaches that can be focused either on form or meaning. Finally, language

should be considered as a vehicle of social and educational communication that

needs to be used in formal and informal settings, but it is relevant to bear in

mind that the decision about where, when, and how to use it is primarily made

by speakers. Thus, language teachers are encouraged to provide students with

the necessary tools to produce not only fluid speech in certain contexts, but

also to produce standard and coherent statements in formal and informal

settings.

Certainly, it is not the intention of this paper to

disapprove teaching approaches which have demonstrated success for years or

acquisition theories that have enhanced the teaching practice of many

educators, but the objective was definitely to learn what theory and research

had to say regarding accuracy in language teaching. I personally believe that

it is unnecessary to qualify or disqualify teaching trends, but identifying the

most significant characteristics of each method might be an interesting

eclectic process to be considered for further teaching practices in which an

accurate, fluent, and communicative-authentic language can be promoted

concurrently.

References

Blaauw-Hara, M. (2006). Why our students need instruction in grammar, and how we should go

about it. Teaching

English in the Two-Year College, 34(2), 165-178.

Brown, D. (2007). Teaching

by principles. An interactive approach to language pedagogy. New York, NY: Pearson Longman.

Celce-Murcia, M. (1991). Grammar pedagogy in second and

foreign language teaching. TESOL

Quarterly, 25(3), 459-480.

Ellis, R. (2002). Does form-focused instruction affect the acquisition

of implicit knowledge? Studies in Second

Language Acquisition, 24(2), 223-236.

Ellis, R. (2006). Current issues in the teaching of grammar: An SLA

perspective. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1),

83-107.

Ellis, R. (2010). Does explicit grammar instruction work? NINJAL Project Review, 1, 3-22.

Ellis, R., & Fotos, S. (1999). Learning a second language through

interaction. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins

Publishing Company.

Fotos, S. (1994). Integrating grammar instruction and

communicative language use through grammar consciousness-raising tasks. TESOL Quarterly, 28(2), 323-351.

Housen, A., & Pierrard, M.

(2005). Investigating instructed second language acquisition.

In A. Housen, & M. Pierrard (Eds.), Investigations

in instructed second language acquisition (pp. 1-27). Germany: Mouton de Gruyter.

Instituto Colombiano para la

Evaluación de la Educación. (2011). [Figure ICFES results in English test 2005-2011]. Retrieved from

http://www.icfesinteractivo.gov.co/historicos/

Krashen, S. (2003). Explorations in

language acquisition and use. Portsmouth, UK: Heinemann.

Lightbown, P. (2004). Commentary: What to teach? How to teach? In V.

Patten (Ed.), Processing instruction:

Theory, research, and commentary (pp. 65-75). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates, Publishers.

Long, M. (1983). Does second language instruction make a difference? A review of the research. TESOL Quarterly, 17(3), 359-382.

Long, M., & Robinson, P. (1998). Focus on form: Theory, research,

and practice. In C. Doughty, & J. Williams (Eds.), Focus on form in classroom second language

acquisition (pp. 15-41). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Macías, D. F. (2011). Towards the use of focus on form instruction in

foreign language learning and teaching in Colombia. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 16(29), 127-143.

Nassaji, H., & Fotos,

S. (2004). Current developments

in research on the teaching of grammar. Annual Review of Applied

Linguistics, 24(1), 126-145.

Norris, J. M., &

Ortega, L. (2002). Effectiveness of L2

instruction: A research synthesis and quantitative meta-analysis. Language Learning, 50(3), 417-528.

Richards, J. (2002). Accuracy and fluency revisited. In E. Hinkel, & S. Fotos (Eds.), New perspectives on grammar teaching in second language classrooms

(pp. 35-50). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Schulz, R. A. (2001). Cultural differences in student and teacher

perceptions concerning the role of grammar instruction and corrective feedback:

USA-Colombia. The Modern Language

Journal, 85(2), 244-258.

Terrell, T. D. (1991). The role of grammar instruction

in a communicative approach. The

Modern Language Journal, 75(1), 52-63.

About the Author

Carolina Cruz Corzo holds a BA in

Modern Languages from Universidad Distrital Francisco

José de Caldas (Colombia), a Specialist Degree in Applied Linguistics

from Universidad La Gran Colombia (Colombia), and an MA in TESOL from

Greensboro College, North Carolina, USA. She currently works as a full time

teacher at Universidad de La Sabana (Colombia).