PROFILE

Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

Vol. 16, No. 2, October 2014 ISSN 1657-0790 (printed) ISSN 2256-5760 (online)

doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n2.46144

Publishing and Academic Writing: Experiences of Authors Who Have Published in PROFILE*

Publicación y escritura académica: experiencias de autores que han publicado en PROFILE

Melba L. Cárdenas**

Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

This article was received on January 24, 2014, and accepted on June 23, 2014.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

The increase in the publication of academic journals is closely related to the growing interest of research communities as well as of institutional policies that demand visibility of the work done by their staff through publications in highly-ranked journals. The purpose of this paper is to portray the experiences of some authors who published their articles in the PROFILE journal, which is edited in Colombia, South America. Data were gathered using a survey carried out through the use of a questionnaire. The results indicate the reasons the authors submitted their manuscripts, their experiences along the process of publication, and what the publication of their articles in the journal has meant to them. The authors’ responses and the reflections derived from them also show that despite the difficulties faced, there were achievements and lessons learned as well as challenges ahead to ensure the sustainability of the journal and teachers’ empowerment.

Key words: Academic journals, getting published, PROFILE Journal, publishing articles, teachers as writers.

El aumento de la publicación de artículos en revistas académicas está relacionado con el creciente interés en ello por parte de los grupos de investigación, así como con las políticas institucionales que buscan dar mayor visibilidad a sus trabajos. El objetivo de este artículo es recoger las experiencias de algunos autores que publicaron en la revista PROFILE, editada en Colombia, Sur América. La recolección de datos se hizo con el uso de una encuesta en forma de cuestionario. Los resultados muestran las razones que llevaron a los autores a presentar sus manuscritos, sus experiencias durante el proceso de publicación y lo que ha significado para ellos la publicación de sus artículos en la revista. Las respuestas de los autores y las reflexiones derivadas indican que, a pesar de las dificultades, hubo logros y lecciones aprendidas. Se plantean, asimismo, futuros retos para asegurar la sostenibilidad de la revista y el empoderamiento de los profesores.

Palabras clave: lograr publicar, profesores como escritores, publicación de artículos, revistas académicas, revista PROFILE.

Introduction

It is important for university professors, pre-service teachers, and schoolteachers in Colombia to share their research, contribute towards local knowledge, learn from each other and value [their] work. Also, I am sure that professionals in other countries appreciate these contributions, as I do theirs. (Maria)

The opinion of this teacher-educator reflects the importance of research and publishing. For most university teachers, the “publish or perish” pressure to sustain a position in our career has had an impact on the field of teaching as researchers and writers and has, in turn, fostered debates regarding teacher preparation and the possibilities we have to get published in academic or scientific journals (Adnan, 2009; Cárdenas, 2003; Lillis & Curry, 2010; Rainey, 2005; Smiles & Short, 2006; Whitney, 2009). This reality is closely related to teachers’ professional development which, from a critical perspective, positions professional learning as a continuous process that acknowledges the theories, personal practical knowledge teachers possess (Golombek, 2009), and their personal interpretations (Johnson & Golombek, 2011). This vision of professional development gives value to teachers’ experience and creativity to face diverse teaching scenarios in which reflection and inquiry allow continuous growth (Johnson & Golombek, 2011; Sharkey, 2009). It also motivates them to make their work public as an approach to professional learning and development (Johnson & Golombek, 2011), to empower classroom practices and improve the quality of education (Kincheloe, 2003). Similarly, the increasing participation of teachers from different educational levels in doing and publishing their research and teacher-based works evidences their commitment toward developing their own expertise through critical inquiry into their own practice and toward the sharing of their experiences. This can be observed, for example, in the ELT (English Language Teaching) journals edited all over the world. Nonetheless, it is necessary to document and study authors’ experiences so that we can foresee actions in the field of teacher-researchers as writers. In this article, we portray the experiences of some authors who have published in a journal edited in the Latin American context.

Over the past two decades Colombia has witnessed an increase in academic journals. This is due to the interest of research communities and institutions in gaining prominence in highly ranked journals as well as in the credits granted to teachers’ careers and in the increases in universities’ prestige. The lastest report issued by the national research agency shows the existence of a total of 466 indexed journals, 254 of which are classified in the areas of social sciences and humanities (Colciencias, 2012). Among them we have 28 specialized in education and 15 in languages and literature; two of them are published only in the English language: PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development (PROFILE henceforth) is one of them. To trace the life of this journal along its first twelve years of publication, we carried out a case study that included a survey in order to portray the experiences of the authors who have published in it. The purpose was to identify the reasons that motivated authors to send their manuscripts to the journal, the difficulties experienced during the whole process—from submission to approval for publication—and some reflections they could share regarding the meaning they assign to the fact of having had their works published in it. The results of the questionnaire used are reported below.

The Study

A descriptive case study (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2011; Yin, 1984, 2009) was conducted to examine the origins and evolution of the PROFILE Journal along 12 years, and in relation to its vision of disseminating research findings, reflections, and innovations by teachers of English. Data collection included a survey, documentary information concerning editorial processes, and my reflections as the editor from its inception. Within the framework of that study, we followed a survey design in order to accomplish a description of trends and opinions of a sample of the population (Creswell, 2009). A short questionnaire was sent by email to all the authors who had published in PROFILE from 2000 to 2012. The questionnaire was cross-sectional, with the data collected at one point in time. The questions were as follows:

1. What made you decide to submit your article(s) for publication in PROFILE?

2. Think about the experiences along the process of publication (submission, evaluation, adjustments) of your article(s) in PROFILE. Which one(s) in particular can you remember/caught your attention?

3. Did you have any difficulties along the process of publication? Yes __ No __

• If yes, what kind?

• What action(s) helped you overcome the difficulties?

4. What has the publication of your article(s) in PROFILE meant to you?

5. Other comments

Context

PROFILE started as an annual publication in 2000 at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá campus. The initial idea was to contribute to teachers’ professional development by publicizing the results of action-research projects carried out by schoolteachers of English who participated in an in-service programme focused on language development, pedagogical updating and action research. Little by little, the journal captured the interest of the local ELT community and has worked towards meeting international standards such as defined criteria for publishing, editorial committees, a style sheet, editorial processes, exchange with other journals, punctuality in its periodicity, and open access. It should be noted that such standards have helped PROFILE be in tune with other ELT research oriented journals.

After four years, PROFILE opened its doors to contributors from other countries and consolidated its mission and vision. At present the journal shares papers authored by schoolteachers, teacher educators, novice teacher-researchers, and university teachers from different parts of the world who have been engaged in carrying out research and innovations in wide-ranging contexts. This can be seen in the sections that characterize it nowadays, namely, Issues from Teacher Researchers, Issues from Novice Teacher Researchers, and Issues Based on Reflections and Innovations. The journal has worked to achieve more visibility through several international databases and reference systems. Its progress has also been acknowledged; for instance, in 2006, it was ranked in the Colombian national indexing system and in 2008 became a biannual journal; at present, it is classified as the most important publication concerning ELT in Colombia and has gained international readership.

Participants

Sixty-seven authors out of the 312 who had published in the journal up to 2012 responded to the questionnaire. They work in different educational levels: seventy percent of them teach in universities; twenty percent in primary and secondary schools; seven percent have just completed a BEd; and three percent teach at language institutes or are freelancers. Their articles deal with the teaching of English, teacher education, and language policies. As far as their nationalities go, 55 (82 percent) are Colombian: 34 work in universities; nine in primary and secondary schools; four in universities and schools; three in language institutes; and five have just completed a BEd. The other authors (12 = 18 percent) are mostly university teachers. They are from the USA (3), Mexico (3: one of them works at a school), India (2), and one each from the UK, Turkey, Italy, and Ukraine. As can be seen, the vast majority of the participants belong to non-Anglophone-centre contexts.

Data Analysis

The identification of commonalities was carried out using the Atlas.ti programme. Since the survey contained open questions, we followed the principles of the grounded theory because it allowed us to systematically organize, analyze, and interpret the gathered data (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). As the data were analyzed, explanations were constructed according to the questions contained in the survey itself. The analysis was primarily descriptive and once it was completed, we did member checking (Merriam, 1991) by sending this article to all the respondents. We got comments from seven members (participants), who checked (approved) our interpretations. Although the number of responses during the member checking process was not high, we could ensure internal validity and trustworthiness (Merriam, 1991).

Results

The data are presented in terms of a description of the patterns or categories (the reasons for submitting articles for publication, experiences along the process of publication, and what the publication of their articles has meant to authors). We also contrast and compare these trends with theoretical concepts underlying them. We illustrate them with some voices from authors, identified with pseudonyms or with the names they chose.

Reasons for Submitting Articles for Publication

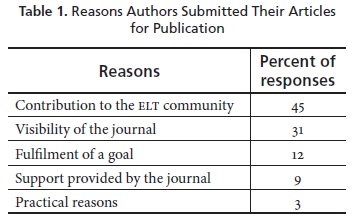

Five main reasons were expressed by the authors. They are displayed in Table 1. Accordingly, several explanations were identified in connection to each one of them.

The main reason authors decide to submit their papers to the journal lies in their conviction in the usefulness of articles published in it. Fifty-five percent of them think that they can collaborate with peers on some serious work and recognize the significance of making their work public, that is, the reaching of teachers through publishing. They are convinced that the papers contained in PROFILE are read by teachers as their contents address common concerns, theories, and issues teachers usually inquire about. As pointed out by one author, “it focuses on topics that foreign language teachers need to debate and it goes beyond presenting games or activities with no theoretical background” (Clara). This evidences that teachers need more than just tips for getting the teaching job done. Thus, publications should comprise thoughtful contents and go beyond the tendency of including guidelines with zero or very little theoretical foundations. In addition, seven percent of the authors expressed their interest in publishing in a Colombian or a local journal because of the importance of “sharing reflections and findings of studies concerning teachers’ development as a way to construct local knowledge” (Adriana). This way authors can contribute to the ELT community and disseminate their work among different scenarios.

Having their work published in a well-known journal is paramount for 31 percent of the authors. As this suggests, an important number of responses showed that the journal recognition, its quality, rigor, ranking, popularity, and “the fact that it is devoted to make different teachers’ voices heard” (Helena) motivated them to submit their works. This testimony advocates the need to position teachers as contributors whose inputs are recognized.

On the other hand and as it is widely known, getting published is a challenge and can be on the list of goals to be achieved in a teacher’s career. Twelve percent of the participants consider that it is a professional and personal challenge; an experience that adds to the pride and the status you gain when you can evidence you have published in a specialized journal.

A schoolteacher decided to send her manuscript to complete the research cycle because “the publication of my article was the second step as a teacher-researcher” (Juanita). Her reflection mirrors a commitment to transcend her teaching job and to develop agency. As in this case, the authors select the journal because it is perceived as a forum that provides opportunities for teachers’ agency work. Agency gives us the power to transform the object of activity; it is understood as the capacity to initiate purposeful action and implies determination, autonomy, independence, and choice (Lipponen & Kumpulainen, 2011). It is not a fixed quality or disposition but something that people do to transform and refine their social and material worlds.

As shown in Table 1, the editorial guidance provided by the journal staff is also crucial in some authors’ resolution to submit their manuscripts. For example, a university teacher asserts: “I know that when I submit an article I receive academic, constructive feedback” (Aleida). Similar to Smiles and Short’s (2006) conclusions, this finding reflects the reality that promoting the circulation of teachers’ works in academic journals requires providing effective support.

Three percent of the authors mentioned three instrumental reasons to explain their choices: course requirements, the teacher-career’s incentives, and their learning as writers. In the first case, a couple of schoolteachers admitted that they fulfilled the writing task because it was a requirement of a teacher development course although they agreed with others on its importance. In the second case, university teachers admitted that they selected the journal because publishing in an indexed journal gives one the possibility of improving her/his salary and adds more points to one’s academic career. Finally, it is worth mentioning that a couple of authors justified their choice in light of an academic exercise in which they could learn from the reviewers’ comments and suggestions, gain awareness about how to write a better paper, and thus be ready to guide others.

The outlined reasons might look commonsensical, obvious, or not surprising. However, the authors’ responses evidence that despite the circumstances faced in their teaching contexts, they are all concerned about the importance of contributing to the profession via a well-positioned publication. The case of PROFILE illustrates the issue of local context as a locus of making teacher narratives public “because it is from and for more diverse professional contexts, it is generating new uses by creating alternative systems for making practitioner knowledge public” (Johnson & Golombek, 2011, p. 503). In the same line of thought, Sharkey (2009) depicts the journal as a space that blurs communities’ boundaries; an opportunity for professionals across the career span to present their work in the same venue. This, in turn, draws our attention towards the fact that academic journals are often associated with core or central commu-nities and countries, a reality which makes it difficult to include voices from the periphery.

Significant Experiences Along the Process of Publication

The authors recalled experiences along the process of publication, namely: submission, evaluation, and adjustments. In order of relevance, they remarked on the opportunities to learn, the tensions generated by the editorial processes per se, and the contribution to their self-esteem. First, there was a consensus about the feedback provided by the reviewers for they are considered knowledgeable authors and academic leaders concerned about the quality of work to be published. Most participants (79 percent) perceived the comments as pertinent and valued the fact that they could learn a great deal because “modifications helped me to understand how articles are developed and organized” (Hernán); and “you confront . . . thoughts with different points of view. . . . This interchange usually leads you to learn in terms of content, research, formal writing” (Fanny). Hence, “the evaluators’ comments stimulated a revision process which proved insightful and enriching” (Franca). In this respect, one author felt she had also gained expertise to guide other teachers to become better writers. Once more, the data suggest authors’ agency: they express their capacity to work in collaboration with others and their predisposition to utilize the support given by others as well as their being a resource for others.

Another survey study conducted by Cárdenas (2003) inquired into the views of schoolteachers who had published in PROFILE in its initial stage. The investigation searched for achievements and difficulties and strategies used to overcome those difficulties. It revealed that schoolteachers who had been away from long written tasks had difficulties coping with the demands of article preparation. The results reported here confirm that particular study and coincide with Smiles and Short (2006) in that writing for publishing offers many professional benefits for teacher-researchers and the academic community, but the journey from writing to actual publication is overwhelming. We found that 29 percent of the authors experimented tensions in attempting to follow the format of an article for it is a very demanding task, and even painful, for some of them. Three percent of them affirmed they had had disagreements with reviewers, but understood them after some time; another three percent explained that coping with different requirements was somehow complex because “sometimes evaluators have different criteria and it is difficult to know which route to go” (John). For one teacher, it generated stress because “it is difficult to follow guidelines from two different evaluators, especially when feedback is not consistent. Of course, this kind of situations is not necessarily negative, but it might be stressful’’ (Aleida). Interestingly, another teacher recalled that team writing was not an easy task because “we were a group of four teachers. It’s difficult to agree on ideas and at the end one of us had to make decisions” (Sandra). Table 2 contains a summary of the main struggles faced and the tools used to overcome them.

For thirty-eight percent of the informants, regardless of constraints, the editorial processes had positive effects on their self-esteem. However, those processes require time and disposition:

I was willing to start writing and to polish my paper but it requires a lot of your free time and effort. On the other hand, it was the first time that I wrote an article so I felt a little bit anxious to know if it was good enough or worth reading for others. Once I started writing and receiving feedback I felt more comfortable and positive, I realized I had a lot to say and I had learnt a lot along the whole process. (Deissy)

Deissy’s reflections represent the commona-lities found in six percent of the participants along the line of self-esteem. First, they realized that there are misconceptions regarding who can get published in academic journals. We also found that although there is often a lack of confidence, the disposition to overcome fears, and the implementation of a timely, user-friendly editorial process can help authors build confidence to continue writing and, in the end, lead to personal satisfaction.

What Has the Publication of Their Articles Meant to Authors?

Their responses to this question can be gathered around three axes: personal and professional achievements and the role of academic journals in giving voice to teachers. At the personal level, sixty-eight percent of the authors recognize that it was a challenge, an important achievement that has brought pride, rewards, recognition, and self-assurance. Those feelings are more significant for some authors who got published for the first time. Two of them answered:

It has given me confidence in my professional field. I am working in international education at a university in the US and am glad to have had an article published in an important journal of Colombia. (Gill)

It has meant a great achievement for me, since I was yet an undergraduate student, and now it can be part of my résumé. (Sandy)

Nowadays, publishing has different meanings for teachers’ careers. As already mentioned, for just a couple of authors it is mainly the fulfillment of a course requirement; for others, it is a personal and professional goal. Professional enrichment has been significant for 93 percent of the respondents for publishing has entailed the possibility of broadening professional background, the satisfaction of sharing one’s work, reaching schools, and leaving a footprint in teacher research. Nevertheless, the boundaries between the personal and the professional meaning the authors assign to the said achievement is not always clear. Instead, we find interesting intricacies: being aware of our capabilities, finding ways to verbalise what we investigate or think, willingness to dialogue with a wide audience, and looking ahead to continue developing professionally. Some authors’ comments include:

[It has been] a great achievement and pride which marks my academic way has to continue in the future and that it is a possibility to share my thoughts with other people in the field. (Ximena)

There is a feeling of professional growth when you see your experiences printed and open to public scrutiny. (Edgar)

Publishing has been an empowering tool . . . as teacher-researcher. (Bertha)

It [publishing] has meant a way to conceptualize about and make sense of language teaching and research as two mandatory activities for critical educators. (Alvaro)

I see the publication of the article as a step to grow personally and professionally. It gave me a platform to voice my choices and experiences which made me more passionate and stronger as a teacher-researcher. (Hernán)

Concerned with the importance of sharing, the authors reflect upon the role of academic journals in sustaining spaces for the dissemination of teachers’ work so that they have the opportunity to participate and contribute via interaction where one is positioned as “an accountable author” (Lipponen & Kumpulainen, 2011, p. 813). In our case, the journal is viewed as “a new platform on which to explore and exchange ideas” (Bernard), which suggests that efforts are being made to reach high standards when carrying out research and writing reports. This last matter implies providing opportunities for continuous learning, for instance, along the publication process and as an extension of it because some authors also advise other teachers in their research. For this reason, some authors advocate that encouragement and support are necessary in helping them to continue developing as publishers of quality research.

It was also noted that the interplay embedded in the publication process is in tune with Bourdieu’s (1986) concept of social capital for it is likely to be created by mutual recognition, receiving respect, and being an author whose ideas are valuable in the eyes of the local and larger community. In this respect, Colombian authors acknowledge the important part the journal can play in the construction of teacher communities, that is, as “a way to have the voices of Colombian researchers heard by teachers, students, and researches in our country ... a contribution to the construction of local knowledge in the field of foreign language teaching and learning” (Isabel).

Conclusions and Implications

The survey was used to bring authors’ experiences to enhance awareness. Their answers reveal five main motives for submitting their manuscripts, to wit: contributing to the profession, the journal recognition, their interest in achieving a goal, the certainty to get support in such endeavor, and some practical motives. But above all, the main driving force has to do with the conviction that as teachers they can and should contribute to the profession. Like Smiles and Short (2006), our participants evidenced that their decision to submit a manuscript was to inform the field by providing a truly emic or insider’s perspective. This finding indicates that teachers not only need to be part of professional communities that support them in their teaching jobs but that they should also feel committed to backing them. One way of doing so is through gaining a voice with other teachers with similar interests and with the ELT community in general by sharing the experiences and the findings of their works. This is perhaps the greatest meaning the authors discover in their publication experience. An author who studied the in-service programme that inspired the creation of the journal and then participated as a tutor remarks:

We are used to do certain things in our everyday classes and we sometimes think it is not worth sharing them in such a formal way. However something I have been learning . . . not only as an author, but as a student-teacher and as a tutor, is that new knowledge does not grow up in genius brains but in real-life-people, informed and reflective perspectives. (Myriam)

In connection to the role of the journal in giving a voice to teachers and although we have not further traced the actual use of the contents of the volumes published to date, the journal seems to be “functioning as a tool for knowledge-building and professional development practices that are working in consort to transform the professional landscape that constitutes the field of SLTE [Second Language Teacher Education]” (Johnson & Golombek, 2011, p. 486). Implicit in most authors’ answers and also explicitly expressed in many of them, we can envision new understandings about publishing and professional development. Publishing is the result of getting involved in a dialogic action by submitting manuscripts intended to reach different audiences. Publishing acts as a mediational tool in fostering teachers’ professional development via recognising teachers’ knowledge as well as their capability to be teacher-researchers and to exercise agency. This way, and despite the demanding process or the difficulties faced, teachers as researchers and writers contribute to strengthening local communities, supporting the circulation of knowledge and good practices in wider contexts, developing professionally through this learning experience, and taking care as regards their self-confidence.

The authors perceive the journal as a forum that provides opportunities for teachers’ professional growth. They also argue that teacher-researchers as writers need to be positioned as contributors whose inputs are recognized. PROFILE is then perceived as a publication containing voices from and for diverse professional contexts; as a publication that has generated spaces for teachers from different educational levels and settings. To this end, the authors participating in our study evidence attempts in crossing boundaries; they have resorted to ways of presenting marked locality in a way that can lead to successful publication and capturing the attention of a wider audience. This is observed in the publication of articles that, although derived from their local teaching contexts, are supported with indigenous and international works, depict courses of action to face given problems, gather conceptual issues that befall most teachers, and match the interests of others working in diverse contexts. Further research would engage us in examining how agency emerges and is constructed through the paths authors follow in this and similar journals.

As far as the tensions experienced, we could identify some of the common problems that obstruct the publishing process. The most notorious, coping with the demands of manuscript revision, calls for the need to keep in mind that for papers published in scientific journals, it is essential to find the appropriate tone to reach first, practitioners, and second, a wider audience. Hence, opening up spaces for teachers to publish their work is not enough; it is mandatory to provide actual support. This could be done through “writing buddies” (Smiles & Short, 2006), that is, those who can accompany authors through careful editorial guidance. In turn, this practice has implications for teacher education programmes, the commitment of stakeholders, editorial boards’ awareness of authors’ profiles, and the establishment of networks of writing activities.

We have a long way to go to ensure the legitimacy of teacher-generated knowledge contained in journals like PROFILE. Yet, we believe that it evidences a space where the local and the global can co-mingle; where new understandings can emerge as a result of that interplay. The challenges ahead to ensure the sustainability of the journal and teachers’ empowerment remain.

*This article reports on the findings of the first stage of an ethnographic research study in progress.

References

Adnan, Z. (2009). Some potential problems for research articles written by Indonesian academics when submitted to international English language journals. Asian EFL Journal, 11(1), 107-125.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241-260). New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

Cárdenas, M. L. (2003). Teacher researchers as writers: A way to sharing findings. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 49-64.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education. London, UK: Routledge.

Colciencias. (2012). Indicadores generales Publindex 2002-2011. Retrieved from http://www.colciencias.gov.co/sites/default/files/ckeditor_files/files/INDICADORES%20GENERALES%20PUBLINDEX%202011.pdf

Creswell, J. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods and approaches (3rd ed.). London, UK: Sage.

Golombek, P. (2009). Personal practical knowledge in L2 teacher education. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), Second language teacher education (pp. 155-162). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, K. E., & Golombek, P. (2011). The transformative power of narrative in second language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 45(3), 486-509.

Kincheloe, J. L. (2003). Teachers as researchers: Qualitative inquiry as a path to empowerment. London, UK: Routledge Falmer.

Lillis, T., & Curry, M. J. (2010). Academic writing in a global context: The politics and practices of publishing in English. New York, NY: Routledge.

Lipponen, L., & Kumpulainen, K. (2011). Acting as accountable authors: Creating interactional spaces for agency work in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 812-819.

Merriam, S. B. (1991). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Rainey, I. (2005). EFL teachers’ research and mainstream TESOL: Ships passing in the night? PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 6(1), 7-22.

Sharkey, J. (2009). Can we praxize second language teacher education? An invitation to join a collective, collaborative challenge. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 14(22), 125-150.

Smiles, T. L., & Short, K. G. (2006). Transforming teacher voice through writing for publication. Teacher Education Quarterly, 33(3), 133-147.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basis of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. London, UK: Sage.

Whitney, A. (2009). NCTE Journals and the teacher-author: Who and what gets published. English Education, 41(2), 101-113.

Yin, R. (1984). Case study research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

About the Author

Melba L. Cárdenas is an associate professor of the Foreign Languages Department at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá campus. She is currently studying for a PhD in Education at Universidad de Zaragoza, Spain, thanks to a scholarship granted by Fundación Carolina. She is the editor of the PROFILE and HOW journals, edited in Colombia.