https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n1.61075

Inclusive Education and ELT Policies in Colombia: Views From Some PROFILE Journal Authors

Educación inclusiva y políticas para la enseñanza del inglés en Colombia: perspectivas de algunos autores de la revista PROFILE

Lina María Robayo Acuña*

Melba Libia Cárdenas**

Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

*lmrobayoa@unal.edu.co

**mlcardenasb@unal.edu.co

This article was received on February 19, 2016, and accepted on September 26, 2016.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Robayo Acuña, L. M., & Cárdenas, M. L. (2017). Inclusive education and ELT policies in Colombia: Views from some PROFILE journal authors. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 19(1), 121-136. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n1.61075.

Code 20175, Sistema de Información Hermes, Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article reports on a study aimed at exploring inclusive policies in the teaching of English as a foreign language in Colombia, as evidenced in the articles published in the PROFILE Journal by Colombian authors. The use of the documentary research method and critical discourse analysis showed that some policies—mainly The National Program of Bilingualism and the Basic Standards for Competences in English as a Foreign Language—contain issues closely related to the logic of discriminatory and segregation attitudes in English language teaching. We hope that the results of our analysis will generate more interest in scholars to examine language policies and work further to eradicate inequalities in education.

Key words: Bilingualism, foreign language teaching, inclusion, inclusive education, language policies.

Este artículo presenta un estudio que exploró las políticas de inclusión en la enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera en Colombia desde el punto de vista de algunos autores colombianos que han publicado en la revista PROFILE. El uso del método de investigación documental y el análisis crítico del discurso mostró que algunas políticas —principalmente el Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo y los Estándares básicos de competencias en inglés como lengua extranjera— contienen elementos estrechamente relacionados con la lógica de actitudes discriminatorias y segregativas en la enseñanza del inglés. Esperamos que los resultados de nuestro análisis generen mayor interés en los académicos por estudiar las políticas lingüísticas y trabajar aún más para erradicar las desigualdades en la educación.

Palabras clave: bilingüismo, enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras, educación inclusiva, inclusión, políticas lingüísticas.

Introduction

In 1994, the representatives of ninety-two governments and twenty-five international organizations met in Spain, for the World Conference on Special Needs Education to reaffirm their commitment to Education for All, to provide quality basic education for everybody and urge a changeover from exclusion in which a person’s disability was a synonym of personal tragedy. They argued in favor of a move from integrated to inclusive education, the model of education that encompasses such diversity.

It is policies that can either facilitate or prevent the development of inclusive educative systems and practices (Ainscow & Miles, 2009). According to Ainscow (2003), the achievement of better and more inclusive policies and practices must be grounded in research. In Colombia, inclusive education (IE) faces challenges such as the poor financial resources of schools and the ideology socialization, that is, the in-favor-of and against postures (Parra Dussan, 2011).

In the field of foreign languages in Colombia and IE, de Mejía (2006) refers to The National Program of Bilingualism (NPB) and points to a need for implementing language policies which allow the inclusion of all the languages and cultures present in the country. Conversely, Medina Salazar and Huertas Sánchez (2008) give an account of English as a foreign language (EFL) teaching experiences with blind students and Rondón Cárdenas (2012) analyzes “some significant moments which evidence the way lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) . . . EFL students draw on different discourses to adapt, negotiate, resist, emancipate, and reproduce heteronormativity” (p. 77).

Cárdenas (2013) started an investigation to portray the viewpoints, research, teaching practices, and policies concerning IE in Colombia, evidenced in the articles published in the PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development Journal (PROFILE henceforth). We report on the study conducted by the research-assistant (Lina) and her mentor (Melba), regarding the policies that guided the authors. First, we present the theoretical and the research frameworks; then, we gather the results and report the conclusions of the study.

Theoretical Framework

Three core concepts guided this study: inclusion, inclusive education, and inclusive education in Colombia.

Inclusion

In order to define inclusion, we should look at four key elements (Ainscow, 2003). First, inclusion is a process; a never-ending search for adequate forms to respond to diversity, to learn to live with differences, to take advantage of them and to comprehend them to achieve sustainable changes. Second, it is centered in the identification and elimination of barriers, which embrace the personal, social, and cultural conditions of determined students or groups of students, policies, and educative resources that produce exclusion. Third, inclusion means assistance and good school performances. In this regard, inclusion looks for the presence (appropriate places), the participation (necessity of listening to the learners to achieve a better quality of their scholar experiences), and the success of all students (in respect not only to the exams results, but also to the curriculum itself) (Echeita Sarrionandia & Ainscow, 2011).

Nevertheless, for these authors the definition of inclusion and therefore of inclusive education is still confusing. In some countries, IE is seen as a way to integrate children with disabilities in the general education system while in others it is perceived as a transformation of the education systems to respond to the students’ diversity. In either case, the concept of “inclusion” seems utopian and idealistic in comparison to what really happens in the classrooms.

Valcarce Fernández (2011) differentiates between integration and inclusion. While the former aims at the normalization of students’ lives and their integration into regular schools, the second has no specific goal; it is a human right. Integration promotes adaptation processes in curriculums, while inclusion pursues the creation of curriculums as an opportunity to learn in several ways.

Inclusion is both a human right and a process. As a human right, it advocates the development, maintenance, and reproduction of the sense of brother- and sisterhood through diversity, whose purpose is to go beyond beliefs about whether or not education is for all and the assistance of people according to their necessities and characteristics. As a process, inclusion involves the cessation of putting minority groups in the midst of those educative systems that claimed themselves as regular educative centers. It also restores the dignity of social, political, and cultural practices in the academic environment as well as in the core of families, communities, and, as a result, in societies.

Inclusive Education

Parra Dussan (2011) distinguishes among the terms education, inclusion, and inclusive education. Education embraces the construction of individual knowledge from the incorporation and internalization of cultural patterns, while inclusion entails making effective human rights. Consequently, IE encloses the transformations of education in general and the educative institutions, so that they can provide equitable and high quality responses to diversity. In this respect, Arnaiz Sánchez (2012) defends the civil and political rights of all citizens and the equality of opportunities and participation in our society, which implies the reduction of cultural, curricular, and community exclusion.

For Arnaiz Sánchez (2012), the construction of IE demands reforms on the conception of education, its curricular organization and methodology, among others. Thus, she proposes that centers of education must, firstly, recognize the educative practices and the existent knowledge on the dynamics of the school. Then, they must adopt an attentive attitude of analysis of the elements that obstruct student participation. This involves a reflective point of view of the school’s own educative practices, the organization of the school and the classroom. Furthermore, educative centers have to make effective use of their support assets, especially human resources. This is a call to work with the students’ and teachers’ bodies, administrative and political authorities, and society in general.

Inclusive schools should be: (1) flexible, (2) informal, (3) horizontal, (4) participative, and (5) competent (Valcarce Fernández, 2011). This can help tailor education to the diversity of the students and promote their participation in the further development of their identity so it can be reflected in, firstly, their schools, then in their community, and finally, in their society.

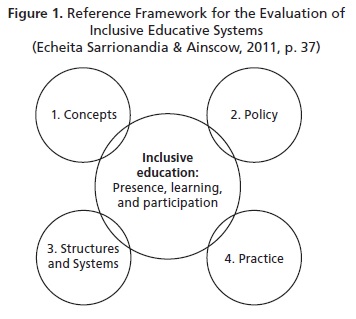

Based on the international research on the characteristics of successful inclusive educative systems, Echeita Sarrionandia and Ainscow (2011) postulate a framework to evaluate them. Three variables of IE (presence, learning, and participation) interact with the constituents shown in Figure 1.

We can note that IE is determined by the context and calls for processes which guarantee the learning and participation of those who may be facing any type of segregation. An education of this type allows the participation and learning of people with disabilities or “additional abilities”, indigenous communities, afro-descendants, the terminally ill, pregnant girls and women, and more recently, young people demobilized from subversive groups and displaced.

Inclusive Education in Colombia

The General Law of Education (MEN, 1994) established that the right to education and equality must be guaranteed to all Colombian citizens and that the State has the obligation to prevent their being victims of discrimination of any kind. The Ministry of Education in Colombia (MEN, n.d.) states that it is required to develop organizational strategies that offer effective responses to address diversity, to develop ethical considerations of inclusion as a matter of rights and values, and to implement flexible and innovative teaching practices that allow a personalized education.

The MEN established policies to regulate pedagogical support for students with disabilities and exceptional aptitudes or talent (Decree 366) (Secretaría General de la Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá, 2009) and guidelines for higher IE (MEN, 2013). These are based on six principles: participation (having a voice in the educative center), diversity (an innate characteristic of human beings), interculturality (the recognition of and dialogue with other cultures), equity (to generate accessibility conditions), quality (optimal conditions), and appropriateness (concrete responses to particular environments).

However, Colombia faces several challenges in the achievement of true IE systems (Parra Dussan, 2011). For instance, according to the National Department of Statistics (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística [DANE], 2010), 43.2% of a total of 146,247 people from 5 to 20 years of age with disabilities did not study at any educational level. The DANE projections indicate that

there are currently 2.9 million people with disabilities, who represent 6.4% of the population. However, the National Demographic and Health Survey (ENDS)1 mentions that this figure actually approaches 7%, that is to say, more than three million Colombians live in this condition. At least 33% of these people from 5 to 14 years old and 58.3% from 15 to 19 years old do not attend school, and only 5.4% of those studying graduated from high school. (par. 1-2)

These figures exemplify what may be similar to other minorities regarding access to education in Colombia. They also show that education policies differ greatly from reality.

Research Framework

Method

We used the documentary research method (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2011) and the critical discourse analysis (CDA) (Fairclough, 2003). In documentary research the main source of data is a written document and, in this study, the unit of analysis (articles dealing with IE and published in the PROFILE journal). Those articles are documents, that is, compilations of meanings given to events, phenomena, and so on, by authors. As noted by the same authors, documentary research is useful when there is little or no reactivity on the part of the writer because the document has not been written to address the research intentions, as in this study. Although that can be a shortcoming, documents themselves (articles, in our case), may be interpretations of events (IE, in our study).

We now explain what is meant by critical, discourse, and analysis. Critical is primarily applied to reveal the hidden relations of power, discrimination, control, and so on, constructed through language. CDA investigates “critically social inequality as it is expressed, signaled, constituted, legitimized . . . by language use (or in discourse). Most critical discourse analysts would thus endorse Habermas’s claim that ‘language is also a medium of domination and social force’” (Wodak, 2001, p. 2).

Discourse, with a small d, signals language in use or the way language is used to “enact” activities and identities (Gee, 1990). Discourses (with a big D) are

ways of talking and writing about, as well as acting with and toward, people and things (ways that are circulated and sustained within various texts, artifacts, images, social practices, and institutions, as well as in moment-to-moment social interactions) such that certain perspectives and states of affairs come to be taken as “normal” or “natural” and others come to be taken as “deviant” or “marginal”. (Gee, 2000, p. 197)

Fairclough (2003) explains discourse in three ways:

Firstly, as “part of the action”. We can distinguish different genres as different ways of (inter) acting discursively. . . . Secondly, discourse figures in the representation of the material world, of other social practices, reflexive self-representations of the practice in question. . . . Thirdly and finally, discourse figures alongside bodily behavior in constituting particular ways of being, particular or social or personal identities. (p. 27)

Discourse is referred to as any form of human expression that accounts for the cultural, ideological, historical identities of humans constructed through social practices and communicative events in a particular time and space. Now, we should define analysis and CDA.

Analysis focuses on the text or discourse as a unit base that has to be considered in terms of what it includes and what it omits (Rogers, 2004). Likewise, CDA embraces a critical perspective “on doing scholarship...‘with an attitude’” (van Dijk, 2001, p. 96) that must focus on pressing social issues for a better understanding of them and to exert social action.

We followed Fairclough’s (2003) levels of text analysis: internal and external relations of texts. The first level includes the analysis of relationships (1) between the elements of clauses and meaning (semantic relations); (2) between the lexical elements of the text and its syntactic disposition (paratactic or hypotatic grammatical relations); (3) between items of vocabulary, words or expressions, that is, collocation patterns (vocabulary relations), and (4) phonological relations (not present in this study).

The external level analyzes “relations of texts to other elements of social events, and more abstractly, social practices and social structures” (Fairclough, 2003, p. 36). Thus, we can study the connections between texts and other voices or texts that have been incorporated into the text. That can happen through quoting, reported speech, and assumptions, which are core aspects for our study.

CDA and text analysis were useful in revealing themes, concepts, categories, and/or patterns. Nevertheless, there is no such thing as a complete discourse analysis. A text can be analyzed in any or in several of its discourse structures. In this regard, van Dijk (2001) suggests selecting for closer analysis those structures that are relevant for the study of a social issue within them: the semantic macrostructures (topics); the local meanings (explicit, implicit, and senses attributed to texts or discourses); the “subtle” forms structures (e.g., propositional structures, rhetorical figures); the context models; and the event models.

Instrument and Unit of Analysis

The core source of information was the articles related to inclusion in English language teaching (ELT) published in the PROFILE journal from 2000 to 2015.2 PROFILE stands for PROFesores de Inglés como Lengua Extranjera (Teachers of English as a foreign language). This biannual publication disseminates research findings, innovations, and reflections in ELT by teachers, teacher educators, and pre-service teachers. To date twenty-three issues have been published. They have gathered 282 articles by 445 worldwide authors.

We first considered the whole range of articles. Then, through systematic review, we filtered the initial corpus to six articles as units of analysis (see Table 1).

The articles were written by Colombian authors in a period of time between 2008 and 2011. Articles 1 and 2 report in-progress and final investigations. The authors of Articles 3 and 4 were at the time new researchers who conducted projects as a requirement to get their bed degrees. Lastly, Articles 5 and 6 gather reflections on bilingual contexts and educative and linguistic policies. The authors’ backgrounds can be read in their corresponding articles.

Research Process

We conducted a meta-analysis (see Table 2) which “is, simply, the analysis of other analyses. It involves aggregating and combining the results of comparable studies into coherent accounts to discover main effects” (Cohen et al., 2011, p. 336).

Results and Discussion

We constantly compared the individual analyses to reach a global interpretation of data. Then, we defined a metaphor as core category (Challenging the “Molds” in ELT), two categories and three sub-categories (see Table 3).

Challenging the “Molds” in ELT

A mold is defined as a hollow container for giving shape to molten or hot liquid material. When a liquid hardens or sets inside the mold, it adopts its shape. Molds are designed in an infinite range of shapes; however, each mold is a unique shape. From this perspective, the logic behind molds is the moldability of a liquid into an immutable solid which is consistent with its specific shape.

The Mold: Linguistic Policies

The linguistic policies in Colombia that the authors are concerned with the most—The NPB and the Basic Standards for Competences in Foreign Languages: English (MEN, 2006) (Standards hereafter)—correlate closely with the logic of molds. The shape is established by the mold these linguistic policies offer for regulating ELT and defining bilingualism in Colombia. However, policies do not conceive, construct, implement, and regulate on their own; the mold’s manufacturers in charge of this are the National Government through the MEN and local educational authorities.

These molds have a noteworthy brand: Advertising Bilingualism. We know that a brand distinguishes one product from others; for the authors, the instrumentalization of language learning, its standardization, and the exclusion of national knowledge, expertise, and minority groups make the product unique. Nevertheless, they consider that these features may be advantageous for a few parties—the British Council (BC), Instituto Colombiano para el Fomento de la Educación Superior (ICFES), and English language institutes—while representing drawbacks for the rest of the clients—parents, teachers, students with minor resources, students from rural areas, children and adolescents displaced from their hometowns, and students from minority groups—because their teaching realities do not fit the mold. Next, we discuss and illustrate each subcategory.

The mold’s brand: Advertising Bilingualism. Every mold has a brand and slogan. For the NPB and Standards, the brand seems to be Advertising Bilingualism. This brand has three main features: The instrumentalization of English language learning (ELLE), its standardization, and the exclusion of national knowledge, expertise, and minority groups.

The instrumentalization of English language learning. Instrumentalization has become an outstanding point of view to set the purposes of ELLE and ELT in the NPB and Standards, even above other purposes such as intellectual, cultural, and language development. From this perspective, ELLE and ELT carry with them positive meanings related to economic advancement, as emphasized in these excerpts:

In Excerpt 1, the verb becomes is a relational process of the type intensive of time, that is, “a process of attribution [that] unfolds through time” (Halliday, 2004, p. 222). The process of attribution is made by something which carries the attribute. In this case, the carrier is foreign language and the attribute a tool that serves economic, practical, industrial, and military purposes. The nominal group: “functioning as attribute construes a class of thing” (Halliday, 2004, p. 219). In Excerpt 2, foreign language (the thing) is grouped into the class of tools to the service of capitalism and globalization.

Excerpt 2 also reveals that speaking English integrates you in Globalization, that is, students learn English to be admitted into the “modern” world and achieve the so-called economic benefits it offers. This indicates that ELLE and ELT, as conceived in the NPB and Standards, are still moving towards integrated education rather than inclusive education to promote dynamics of merchandizing that corresponds to globalization.

Globalization “does not simply mean the creation of a world-embracing economic system paving the way for cultural homogenization on a world-wide basis, and it is not just a new variant of the so-called cultural imperialism” (Turner & Khondker, 2010, p. 19). This conceptualization of globalization may not be the one considered by the manufacturers of the NPB and Standards as discussed in the next section.

The standardization of English language learning. As long as the formulation of ELT and ELLE purposes come from a utilitarian view of the language, the mold’s manufacturers follow the logic of standardization to homogenize, control, measure, and evaluate. Usma Wilches (2009) asserts:

The author highlights how the logic of standardization works: importation of international products into the local context. The lexical choice for the verb prove takes one to the mental image that manufacturers of these models have: the assumption that there may be a single, more accurate, appropriate and acceptable way for ELT teachers to be, to know, and to know how to do. Additionally, prove nourishes the idea that there are at least two actors involved in the material process to prove: Those who prove (students and teachers) and those to whom the achievements of standards have to be proven. These are some glimpses of to/for whom standards work.

These authors agree with Usma Wilches (2009) and emphasize that manufacturers assume that foreign and external discourses and models to define and evaluate ELT in Colombia are represented as universals, as “meanings which are shared and can be taken as given” (Fairclough, 2003, p. 55). This way, Standards are being proved to an international community, which controls and shapes the molds in ELT and educative policies.

When Usma Wilches (2009) states that CEFR and TOEFL were designed for other contexts, he has an “assumption about what is good or desirable” (Fairclough, 2003, p. 55). The fact that linguistic policies are adopted is seen as undesirable, while adaptation and creation of policies according to the national contexts are seen as desirable. Thus, the adoption of foreign and external models to evaluate ELT and ELLE in Colombia depicts a problem:

For the above-mentioned authors, standardization has as reliable and faithful allies ELT tests and certifications. They maintain the mold in accordance with its brand “Advertising Bilingualism” as well as with the instrumental approach to ELT.

In Excerpt 6, these products constitute a cataphorical reference of tests and certifications, which illustrate the conception of examinations as goods available for sale to the public. With the exception of the ICFES national examination, the other international products charge hefty fees between 350,000 and 500,000 Colombian pesos—approximately 160-250 US dollars.

Accordingly, the notion of tests and examinations in the service of standardization, and therefore, for the instrumental view of ELT and policies, has sparked more questions: Do they actually contribute to the intellectual, cultural, or language development of their clients? Or do they only amplify the notions of competitiveness, human capital, and knowledge economy?

Exclusion of national knowledge, expertise, and minority groups. We have discussed that the mold has an instrumental view of language learning and its standardization. This, in turn, has shaped the NPB and Standards mold and favored the importation of discourses, models, and practices to regulate ELT in Colombia at the expense of national knowledge, expertise, and minority groups.

The externalization and standardization processes have become the lid of the mold. It keeps the raw material within it, permits inserting the country into the economic trends in times of globalization and internationalization, and restrains the entrance of other elements. For instance, the exclusion of teachers and their knowledge is questioned below:

In Excerpt 7, the authors disclose a conflict: There is a marked preference to hire foreign native-speaker teachers, ignoring the experience, qualifications, and even a critical unemployment rate. This suggests a pre-established image of the teachers of English and the assumption that the foreigner speaks English better; thus s/he can teach it better, while the national teacher is underestimated and considered to have fewer capabilities.

In Excerpt 8, Usma Wilches (2009) sums up the logic behind standardization. It reflects a lack of trust in the knowledge and expertise of teachers, which the government tries to diminish through homogenization.

Teachers are not the only absentees in the mold of the NPB and Standards. Ávila Daza and Garavito (2009) claim that parents and their children do not know each other and explore the possibility of involving parents in English homework tasks. They pinpoint:

Excerpt 10 shows that the problem does not only emerge from the lack of interaction between parents and children, but also between parents and schools. Hence, collaborative work is desirable because it brings about improvement in students’ performances. For the authors, “the current world”, in Excerpt 11, may be regarded as a euphemism of the word globalization, which, in turn, may be a euphemistic word of westernization. Thereby, globalization has a negative connotation because it draws the family members’ attention away from the family itself, which boosts more fragmented interactions.

Further absentees in the mold are minority groups, for instance, deaf people, indigenous communities, and students with minor resources. Ávila Caica (2011) expresses:

In Excerpt 12, the author claims that her goal to conduct the investigation is influenced by an existential assumption3 about the condition of deaf students in regard to ELLE. For her, deaf people are often at a disadvantage in ELLE compared with their hearing peers. This is due to the English language having been conceived in recent years with an instrumental lens, which, at the same time, would ascribe them to globalization, as manifested in Excerpt 13. Thus, the author sees this gap between deaf people and their hearing peers as a social disadvantage that needs to be revised.

The case of indigenous communities is also worrisome. Cuasialpud Canchala (2010) writes:

Cuasialpud Canchala (2010) identifies three main problematic social conditions for English language indigenous students. First, the Colombian education system does not offer coverage for the whole indigenous peoples. Second, indigenous peoples’ school background is precarious. They have gone through a primary and secondary education of low quality, with few human and material resources. Third, indigenous students have to face multilingualism rather than bilingualism. In a first instance, they have to learn Spanish, and usually go to school without a high performance of the language, and then, they have to face a third language, English. Besides, teachers are usually not well prepared to teach Spanish and English from a multicultural approach.

If communities are excluded from the mold, their native languages are also being excluded. Guerrero (2008) explains this in her analysis of the title of Standards:

In Excerpt 17, second languages nourishes the idea that indigenous languages spoken in Colombia are included. Additionally, the author identifies another image: for MEN, foreign language teaching must be oriented towards languages that represent a sort of capital. Therefore, English represents capital, globalization, and internalization and becomes the main reasoning to exclude other languages from the mold of Standards and the NPB.

Reshaping the Mold: Coping With Teaching Realities

Category one shows that linguistic policies such as the NPB and Standards represent a mold being manufactured by MEN and the BC, which wave a flag with its brand Advertising Bilingualism. The mold is characterized by the instrumentalization of language learning, and its standardization, both of which compose the lid of the mold, which allows the exclusion of national knowledge, expertise, and minority groups.

This second category denotes the authors’ attempt to reshape the mold, so that it is malleable, more diverse, and inclusive. To do so, we require teachers’ empowering students to overcome barriers and acting based on guiding principles.

Empowering students to overcome barriers. The empowering of students can be constructed through two strategies: Collaboration and creation of the classroom as a “meeting place”.

Collaboration. Collaboration aims at strengthening the social dimension and building an inclusive society which combats discriminatory and segregating attitudes arising from molds. To do so, students, teachers, and parents work jointly to break down the barriers that may emerge. Thus, collaboration allows for healthy, spontaneous interactions, as expressed by Ávila Caica (2011):

Collaboration can emerge from the relationship between parents and children as well as parents and the educative center of their children. For Ávila Daza and Garavito (2009),

Another type of collaboration may be the interaction between teachers and students in individual tutoring. This can increase students’ confidence and improve ELLE performances while bearing in mind students’ own paces and needs. Cuasialpud Canchala (2010) notes:

Collaboration is also crucial in blended learning (BL). BL is, in general terms, the combination of virtual instruction and face-to-face classes. EFL internet resources play an important role in ELT and ELLE as these allow collaborative work, enhance autonomy, and keep students motivated (Ávila Caica, 2011). As she found,

The classroom as a “meeting place”. For the mold of the NPB and Standards, the classroom is a place for learning how to find a new job and better salaries. By contrast, a classroom in which teachers challenge the mold is a “meeting place”, where diverse cultures, communities, needs, and desires converge.

This inclusion of diversity in the ELT classroom allows the creation of friendly, pressure-free learning environments in which students work collaboratively, value and respect their peers, and are aware of self and others (Ávila Caica, 2011). The author notes:

Conversely, Escobar Alméciga and Gómez Lobatón (2010) advocate for a multicultural approach to ELT. They suggest challenging the mold

A multicultural approach has to be reflected by live and meaningful learning experiences that allow the recognition of the other as an equal individual. Escobar Alméciga and Gómez Lobatón (2010) explain:

Acting based on guiding principles. Empowering students to overcome barriers is not enough for reshaping the mold. We need to act based on guiding principles.

Elimination of barriers. We have examined some barriers which emerge mainly from the mold (The NPB and Standards): the instrumental view of language learning (i.e., ELT and ELLE for economic advancement), the standardization of language learning (i.e., ELT and ELLE as a way to pay for tests and meet scores), and the most worrisome barrier, the exclusion of national knowledge, expertise, and minority groups. Nevertheless, other barriers need attention: those which emerge from social conditions that the manufacturers of the NPB and Standards make invisible because of their elitist conception of bilingualism. To mention some:

As a consequence of the barriers which emerge from both linguistic policies and social conditions in Colombia, we need to challenge and reshape the mold so that these inequalities diminish and students can enjoy successful learning performances. This may be the inclusion brand.

Creating the inclusion brand. Reshaping the mold means, indeed, to create a new mold in ELT, and therefore, a new brand in which teachers take informed decisions and act on guiding principles to challenge the existing one (Escobar Alméciga & Gómez Lobatón, 2010; Guerrero, 2008; Usma Wilches, 2009). The inclusion mold implies that new linguistic and educative policies, teachers, and educative centers adopt an ELT approach that recognizes: (1) the local contexts and necessities, (2) the local expertise and knowledge, (3) the right to be different, and (4) the duty to learn about/from other human beings.

Conclusions

The objective of this research was to examine the topic of inclusion in ELT in Colombia in regard to the policies that guide some authors’ articles published in the PROFILE journal. It became evident that the implementation of the NPB and Standards are the linguistic and educative policies that the authors are concerned with the most. The authors reveal that these policies are characterized by the instrumentalization of language teaching, its standardization and the exclusion of local knowledge, expertise, and minority groups. These features allow concluding that the NPB and Standards do not facilitate the promotion of inclusive practices. Nevertheless, we think the identification of sources of exclusion is a good place to start talking about inclusion.

Inclusion in ELT means to recognize (1) the local contexts and necessities, (2) the local expertise and knowledge, (3) the right to be different and to have access to education of quality and equal opportunities, (4) the duty to learn about others, and (5) the students’ learning paces, desires, and needs. These ideas, plus the identification and elimination of barriers, motivate the authors to study matters concerning policies of inclusion in ELT and to change their practices to an inclusive brand.

The authors remark that inclusion in ELT requires coping with teaching realities, students’ empowerment to overcome barriers, and acting based on guiding principles. Practices that promote collaborative work, individual guidance, blended learning, a multicultural approach to education, and the creation of the ELT classroom as a meeting place are key and enriching elements. Inclusive classrooms should be places where diversity converges, interacts, and constructs to promote students’ successful learning. Finally, acting based on leading principles entails putting into practice the elimination of barriers—those which emerge from linguistic and educative policies as well as those which emerge from the inequality in social conditions. Furthermore, it demonstrates teachers’ attempts to create opportunities for students, to help each other, and to construct meaning and knowledge.

1ENDS stands for Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud [National Survey of Demografic Health].

2For 2015, only Issue 1 was selected.

3Existential assumptions are defined as those “assumptions about what exists” (Fairclough, 2003, p. 55).

References

Ainscow, M. (2003, October). Desarrollo de sistemas educativos inclusivos [Development of inclusive educative systems]. Paper presented at the Congreso Guztientzako Ezkola, San Sebástian, Spain.

Ainscow, M., & Miles, S. (2009). Developing inclusive education systems: How can we move policies forward. In C. Giné, D. Durán, T. Font, & E. Miquel (Eds.), La educación inclusiva: de la exclusión a la plena participación de todo el alumnado (pp. 167-170). Barcelona, ES: HORSORI.

Arnaiz Sánchez, P. (2012). Escuelas eficaces e inclusivas: cómo favorecer su desarrollo. [Effective and inclusive schools: How to promote their development]. Educatio Siglo XXI, 30(1), 25-44.

Ávila Caica, O. (2011). Teacher: Can you see what I’m saying? A research experience with deaf learners. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 13(2), 131-146.

Ávila Daza, N., & Garavito, S. (2009). Parental involvement in English homework tasks: Bridging the gap between school and home. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 11(2), 105-115.

Cárdenas, M. L. (2013). Inclusión y enseñanza del inglés en Colombia: panorama desde una revista. [Inclusion and the teaching of English in Colombia: A viewpoint from a scientific journal]. In B. Vigo & J. Soriano (Coords.), Educación inclusiva: desafíos y respuestas creativas (pp. 434-446). Zaragoza, ES: Universidad de Zaragoza. Retrieved from http://www.grupo-edi.com/documentación/Actas_publicacion.pdf.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education (7th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Cuasialpud Canchala, R. (2010). Indigenous students’ attitudes towards learning English through a virtual program: A study in a Colombian public university. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 12(2), 133-152.

de Mejía, A.-M. (2006). Bilingual education in Colombia: Towards a recognition of languages, cultures, and identities. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 8, 152-168.

Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística, DANE. (2010). Población con registro para la localización y caracterización de las personas con discapacidad: condición de asistencia escolar y grupos de edad entre 5 y 20 años [Population with register for the localization and characterization of people with disabilities: School attendance and groups of people ranged between 5 and 20 years] [Data file]. Retrieved from https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/demografia-y-poblacion/discapacidad.

Echeita Sarrionandia, G., & Ainscow, M. (2011) La educación inclusiva como derecho: marco de referencia y pautas de acción para el desarrollo de una revolución pendiente [Inclusive education as a right: Framework and guidelines for action for the development of a pending revolution]. Tejuelo: Revista de Didáctica de la Lengua y la Literatura, 12, 26-46.

Escobar Alméciga, W., & Gómez Lobatón, J. (2010). Silenced fighters: Identity, language and thought of the Nasa People in bilingual contexts of Colombia. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 12(1), 125-140.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gee, J. P. (1990). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideologies in discourse. London, UK: Falmer.

Gee, J. P. (2000). Discourse and sociocultural studies in reading. In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. III, pp. 195-207). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Guerrero, C. H. (2008). Bilingual Colombia: What does it mean to be bilingual within the framework of the National Plan of Bilingualism? PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 10(1), 27-45.

Halliday, M. A. K. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Medina Salazar, D., & Huertas Sánchez, A. (2008). Aproximaciones a la inclusión del estudiante invidente en el aula de lengua extranjera en la Universidad del Valle. [Approaching the inclusion of blind students in the EFL classroom in the Universidad del Valle]. Lenguaje, 36(1), 301-334.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN. (1994, February 8). Ley General de Educación: Ley 115 [General Law of Education: Law 115]. Bogotá, CO: Author.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN. (2006). Estándares básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras: inglés. Formar en lenguas extranjeras: ¡el reto! Lo que necesitamos saber y saber hacer [Basic standards for competences in foreign languages: English. Teaching in foreign languages: The challenge! What we need to know and do]. Bogotá, CO: Imprenta Nacional.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN. (2013). Lineamientos política de educación superior inclusiva [Higher inclusive education policy guidelines]. Retrieved from http://redes.colombiaaprende.edu.co/ntg/MEN/pdf/Lineamientos.pdf.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN. (n.d). Colombia avanza hacia una educación inclusiva con calidad (I). [Colombia is moving forward towards an inclusive education with quality]. Centro Virtual de Noticias de Educación. Retrieved from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/cvn/1665/article-168443.html.

Parra Dussan, C. (2011) Educación inclusiva: un modelo de diversidad humana [Inclusive education: A model of human diversity]. Revista Educación y Desarrollo Social, 5(1), 139-150.

Rogers, R. (2004). An introduction to critical discourse analysis in education. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Rondón Cárdenas, F. (2012). LGTB students’ short narratives and gender performance in the EFL classroom. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 14(1), 77-99.

Secretaría General de la Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá. (2009, February 9). Decreto 366 [Decree 366]. Retrieved from http://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=35084.

Turner, B. S., & Khondker, H. H. (2010). Globalization east and west. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Usma Wilches, J. (2009). Education and language policy in Colombia: Exploring processes of inclusion, exclusion, and stratification in times of global reform. PROFILE Issues in Teachers Professional Development, 11(1), 123-141.

Valcarce Fernández, M. (2011). De la escuela integradora a la escuela inclusiva [From the integrating schools to inclusive schools]. Innovación Educativa, 21, 119-131.

van Dijk, T. A. (2001). Multidisciplinary CDA: A plea for diversity. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis (pp. 95-119). London, UK: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857028020.n5.

Wodak, R. (2001) What CDA is about: A summary of its history, important concepts and its developments. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis (pp. 1-12). London, UK: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857028020.n1.

About the Authors

Lina Robayo Acuña holds a B.Ed. in Philology and Languages: English from Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá campus. She is currently finishing a B.Ed. in Linguistics from the same university. Her research interests include teaching English as a foreign language, inclusive education, and linguistic policies.

Melba Libia Cárdenas is an associate professor of the Foreign Languages Department at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá campus. She is currently studying for a PhD in Education at Universidad de Zaragoza, Spain, thanks to a scholarship granted by Fundación Carolina. She is the editor of the PROFILE and HOW journals, edited in Colombia.