Virna Velázquez*

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, Toluca, Mexico

Edgar Emmanuell García-Ponce**

Universidad de Guanajuato, Guanajuato, Mexico

*virnalenguas@hotmail.com

**ee.garcia@ugto.mx

This article was received on June 12, 2017 and accepted on March 9, 2018.

How to cite this article (APA, 6th ed.):

Velázquez, V., & García-Ponce, E. E. (2018). Foreign language planning: The case of a teacher/translator training programme at a Mexican university. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 20(2), 79-94. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.65609.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

The present article reports on a study that set out to investigate the effectiveness of strategies and decisions formulated in foreign language planning to ensure learners’ language achievement in a higher education context which trains learners to become English or French teachers or translators. By drawing on data collected from simulated proficiency tests and interviews with students, teachers, and administrators, the findings show that the foreign language goals have not been met as stipulated in the curriculum, and that there are several shortcomings in the foreign language planning that need the educational community’s consideration. This article also discusses some factors that should be considered in foreign language planning in order to meet language goals in educational contexts.

Key words: Curriculum, English as a foreign language, language planning, low proficiency level, teacher training.

El presente estudio se realizó con el objetivo de explorar la efectividad de estrategias y decisiones como parte de una planificación de lenguas extranjeras. Esta planificación lingüística se ha implementado para promover la competencia lingüística como parte de una licenciatura que prepara estudiantes para ser maestros o traductores de inglés o francés. Al explorar datos estadísticos y de entrevistas con estudiantes, maestros y administrativos, los resultados muestran que los objetivos de las lenguas extranjeras no se han logrado y hay varias limitantes con respecto a su planificación. Estos resultados son de gran relevancia para entender algunos factores que deberían ser considerados en una planificación lingüística con objetivos concernientes a las lenguas extranjeras en contextos de enseñanza y aprendizaje.

Palabras clave: bajo nivel de lengua, curriculum, formación docente, inglés como lengua extranjera, planificación lingüística.

Language planning (LP) is defined as the search for and formulation of strategies to cover linguistic needs of target people who learn languages for educational, political, and employment purposes (Tollefson, 1994). The strategies in LP can be formulated following two broad perspectives: (a) LP in communities or societies involving sociolinguistic factors (i.e., corpus and status planning) and (b) LP for language education purposes (i.e., language acquisition planning) (Baldauf & Kaplan, 2007; Cooper, 1989). In the latter planning category, decisions are strategically planned in order to set and achieve linguistic goals in teaching and learning contexts. In order to ensure LP’s effectiveness, a number of measures are used to evaluate its processes and thus effectiveness. The aim of this article is to evaluate the effectiveness of foreign language planning (FLP) that has been implemented at a university in Mexico which trains learners to become English or French teachers or translators during a five-year training programme. Three research questions were thus formulated to guide the study:

For Gadelii (1999), LP involves decisions that a group of people (i.e., linguists or government) makes, plans, and applies to solve issues related to a language or languages, in cases of bilingualism or multilingualism. Haugen (1996) alludes to Weinrich as the first scholar who first used the term LP during a seminar given at Columbia University in 1957. Regardless of the fact that LP is nowadays considered a legitimate field of study, the different angles which are used to approach LP processes have not been exempt from controversy. In particular, the need for adequate frameworks or theory through which the processes involved in LP are explained and evaluated has been highlighted:

We are particularly limited with respect to any systematic social theory-guided approach to why certain selective, elaborative, and codification attempts succeed (i.e., why they are accepted by the desired target populations), whereas others fail. (Fishman, Das Gupta, Jernudd, & Rubin, 1971, p. 304)

Despite Fishman et al.’s (1971) call for a theory-based approach for LP, recent research literature has still put forward the need for such an approach which facilitates the formulation of strategies and evaluation of processes as part of LP (see Amorós, 2008). However, there are indeed agreed processes which can be followed in LP. These processes involve:

Firstly, descriptions are elaborated regarding the influence of agents on (a) which behaviours, (b) of whom, (c) by which means, and (d) with which results. Secondly, after the influence is described, the facts that are perceived to be involved in the language learning process are predicted. Thirdly, the facts alongside their processes are explained. Finally, generalisations are formulated, and results are suggested. In order to obtain effective outcomes, Mesthrie, Swann, Deumert, and Leap (2009) suggest that LP should go through the following stages:

However, it is not always possible for strategies formulated in LP to yield expected outcomes. Therefore, Baldauf (2004) argues that in order to ensure effective outcomes, LP should include:

In line with Fierman (1991), Baldauf (2004) and Payne (2007) we agree that LP should include decisions strategically planned to alter or change a linguistic situation or aspects of (a) language(s). However, he goes further to emphasise the need to formulate alternative strategies in order to ensure the effectiveness of LP. Baldauf’s suggestion is of particular relevance for LP in educational settings which have not been exempt from shortcomings. These shortcomings are claimed to be largely motivated by the educational system and characteristics of the linguistic community and curriculum, among others, as well as having an impact on learners’ language achievement, attitudes, and motivation (Tergborg, Lastra & Moore, 2006). However, as we shall discuss later in this article, LP in educational contexts should take into account not only instructional (i.e., teaching- and learning-related practices) but also perceptual (i.e., speakers’ perceptions and attitudes) factors in order to ensure its effectiveness. Regarding the former factors, González, Vivaldo, and Castillo (2004) suggest the following strategies:

These strategies are of great importance for the purpose of exploring the effectiveness of the FLP decisions and strategies in the teaching and learning context in which the study took place. As we will see, it also seems important that alternative actions are formulated, implemented, and evaluated to ensure the effectiveness of teaching and learning practices and thus language achievement.

So far, we have seen that research literature has long put forward the call for a theoretical and methodological approach which facilitates the processes and effectiveness of LP. The lack of such an approach may be due to the diverse objectives, languages, contexts, speakers, and communities that planners have sought to investigate, making it almost impossible to converge on effectively common LP strategies. As a consequence, research literature has yielded different strategies or methods to approach a linguistic situation in a speech community. The absence of this approach has been extrapolated to language educational settings, where linguistic competence goals have not been fully met as expected. This is the case of the research context of this study where learners have been seen not to develop a foreign language competence as stipulated in the official curriculum. With the aim of understanding the factors that may be motivating the shortcomings of the current FLP in this context, this study firstly examines the attainment of language proficiency goals as stipulated in the curriculum. It secondly explores the learners’, teachers’, and administrators’ perceptions concerning the decisions and strategies that have been formulated and implemented in order to achieve these linguistic goals. As we shall see, some of these decisions and strategies mirror Fierman’s (1991), Baldauf’s (2004), and Payne’s (2007) suggestions for planning languages, but others need the language community’s consideration in order to ensure the effectiveness of the FLP and thus learner achievement in this teaching and learning context.

The present study was motivated by perceptual evidence that a high number of learners in this context was unable to meet the language goals stipulated in the curriculum. As we shall see, this evidence was corroborated by the results of diagnostic exams (García Ponce, 2011), which are known in this context as mock exams (see below). The learners’ low language proficiency raised the need to explore and evaluate the current FLP strategies with a view to understanding how learners in this teaching and learning context may develop more effective linguistic and interactional skills. This research interest was reinforced by the fact that these learners are being trained to become language teachers or translators and will rely on their language skills to effectively teach or translate the foreign languages. Moreover, it is known in this faculty that due to their low proficiency level, these learners sometimes compete for jobs with individuals whose profession is not related to language teaching or translation studies, but whose language competence is higher than theirs (García Ponce, 2011).

The study took place in the Faculty of Languages at the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México (UAEM). This university is a higher education institution whose language faculty currently offers a five-year programme aimed at training learners to become English or French teachers or translators. This institution was established in the early 1990s in the City of Toluca, Mexico. It initially began offering the BA in English and, in subsequent years, the BA in French Language and Culture. In 2003, the administration decided to merge both programmes, and the teacher/translator training programme (i.e., BA in Languages) was then created. As stipulated in the curriculum (UAEM, 2010), learners are expected to develop abilities which promote knowledge of and reflection on the foreign language, teaching practices, and translation skills. Due to practical constraints, the present paper is unable to encompass all the strategies that are planned and implemented for each major (i.e., language teaching or translation). However, the paper is a starting point to understand the strategies and decisions that converge during the FLP for both English and French. Concerning these two target languages, the goals in this institution are the following:

Specifically, learners are expected to develop a minimum linguistic competence of B2 according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFRL), and an intermediate proficiency level in the FL in which they are not majoring. In order to facilitate the achievement of these objectives, learners are given an active responsibility for their academic progress at their convenience (UAEM, 2010). This active responsibility involves not only making decisions as to the selection of subjects and hours of study per semester, but also finding opportunities which promote language learning autonomy (UAEM, 2010).

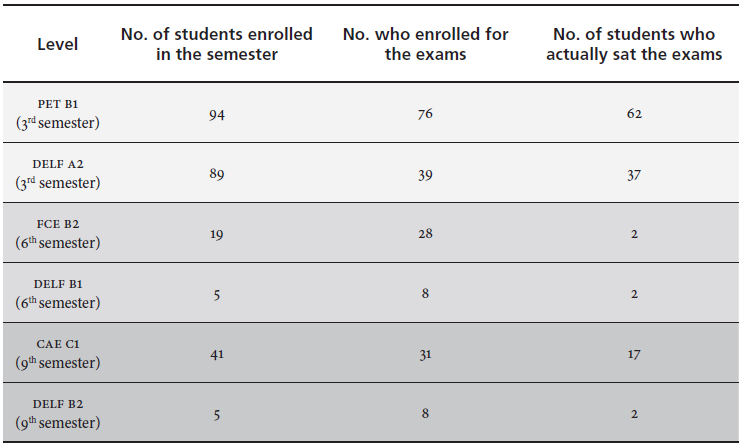

As previously stated, the purpose of this study is twofold. Firstly, it aims to determine the effectiveness of the strategies and decisions in FLP. In order to attain this, we used the results of mock exams of 122 learners (81 majoring in English, and 41 majoring in French) enrolled in semesters III, VI, and IX (see Simulated Proficiency Tests section). Secondly, it explores learners’, teachers,’ and administrators’ perceptions regarding the strategies and decision-making involved in the FLP work carried out by the institution. For this, in order to understand the strategies, interviews were conducted with 18 learners, 12 teachers, and 14 administrators. The 18 participant learners (three learners of English and three learners of French taking semesters III, VI, and IX, respectively) were chosen randomly from attendance lists, contacted in their classrooms, and invited to participate in this study under no obligation. The participant teachers, of English and French, were also teaching in those semesters and were invited to participate in the interviews. In the case of the administrators, only those that actively participate in the design of the FLP were chosen and invited to participate. In total, 44 informants participated in the interviews which were held at their convenience over a period of three months.

Mock exams in this context are administered every semester following two broad aims: (a) to promote learners’ awareness of their foreign language competence, and (b) to evaluate learners’ language achievement in relation to the curriculum’s linguistic goals. It should be noted that these exams follow the same structure and sections of international language certifications in order to train learners in passing these tests and thus obtain language certificates which they will need in order to work in the Mexican labour market.

The analysis of the results of these exams (122) followed a quantitative approach, involving simple total numbers, averages, and percentages (please refer to Appendices A, B, and C for more information).

The interviews with the three groups of this educational community (i.e., learners, language teachers, and administrators) were recorded in order to facilitate the explorations of the FLP. Three interview guides were designed, one for each group, consisting of 25 to 34 items. Face validity of the interview guides was ensured by three scholars who (a) were familiar with LP strategies and language teaching, (b) participated as pilot informants; and (c) gave feedback as to the structure of the items and guides. The recorded interviews were conducted in Spanish in order to avoid the participants’ concerns about the correctness of their responses, and to promote a rapport between the interviewer and participants. The recorded interviews were transcribed completely in order to explore from micro and macro lenses the informants’ perceptions concerning the decisions and strategies in the FLP. The transcribed data were then analysed through a meaning categorisation which is believed to facilitate the identification of patterns, themes, and meaning (Berg, 2009). This involved identifying extracts manually, and attributing them to theme categories and sub-categories which emerged from the data. In order to protect the participants’ identity, the words “Learner”, “Teacher”, or “Administrator” and an identification number (e.g., Teacher 5) were used in the results and discussions.

In order to address the first two research questions (i.e., how effective is the current FLP in the Faculty of Languages? And what can we learn from the learners’, teachers’, and administrators’ perceptions concerning the FLP as a process to ensure learner achievement?), this section discusses the results concerning the explorations of the FLP in this higher education context. The discussions revolve around five macro themes: (a) foreign language planning, (b) learners’ foreign language proficiency, (c) language teaching and learning practices, (d) foreign language classes and learner motivation, and (e) language resources and learner autonomy. Overall, the evidence corroborates that the learners’ language proficiency was low and suggests that there is a number of shortcomings in the FLP which needs alternative actions in order to ensure learner achievement progressively.

Overall, the elicited data indicated various perceptions concerning the FLP carried out by the Faculty of Languages. Twenty-five percent of the administrators’ responses suggested an endorsement for continuous planning and evaluation of the foreign languages: English and French, as suggested in Extract 1.

Extract 1

Of course [FLP] is important because our BA programme is in languages. (Administrator 7)

This endorsement reflects Moreau’s (1997) and Cooper’s (1997) suggestions that languages should be continuously planned and evaluated in order to guarantee an effective implementation of strategies. In line with Moreau (1997) and Cooper (1997), Weinstein (1980) highlights that LP needs to be in continuous development and evaluation so that language planners or the community design and implement corrective or alternative actions. Seventy percent of the participant learners’ responses suggested that learners, as well as teachers and administrators, should take part in the FLP processes. For example, Learner 11 (English) mentioned the following:

Extract 2

I think that everybody should participate; the director, sub-director, mostly teachers, but students should also voice their opinions.

Learner 11’s response suggests the idea that the whole community should participate in the decision-making of the FLP. What is interesting in the phrase “but students should also voice their opinions” is that Learner 11 reveals a perceived lack of learner participation in this decision-making. According to Fierman (1991), all the members of a community should participate in the process of planning a language in order to promote effective implementation. As we shall see below, there was a number of perceived shortcomings related to the FLP. These shortcomings were particularly associated with the administration’s emphasis on teaching practices, neglecting learning-related practices as suggested by the informants. These perceived shortcomings in turn reveal the failure of the current FLP to formulate strategies taking into consideration learner voices and perceptions.

When asked about learners’ proficiency level, 50% of the participant learners felt that the proficiency level was generally low. This was also felt by Administrator 8, as suggested in Extract 3.

Extract 3

I think that in general it is considerably low. I have been interviewing language coordinators from other institutions and they do not hire graduates from this faculty. Their reason is that they are perceived [by the coordinators] to have a low language proficiency.

Forty-five percent of the informants (involving learners, teachers, and administrators) were aware that this low learner achievement was against the stipulations of the curriculum. For example, this feeling was suggested by Teacher 2 (French) as follows.

Extract 4

Regarding the curriculum, I believe that [the results from the tests] are low because we are training future English or French language teachers and they should have a higher language proficiency level than the public in general.

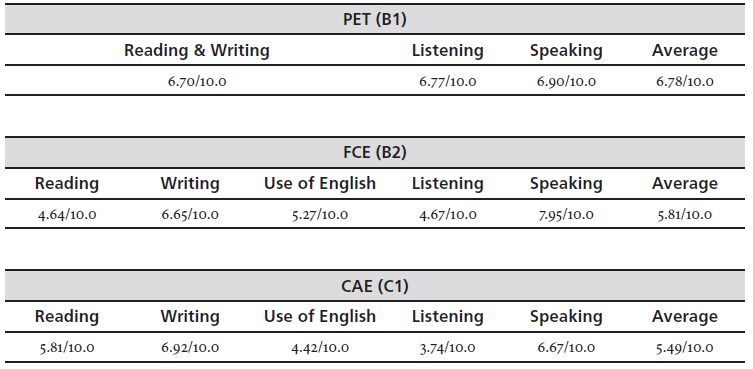

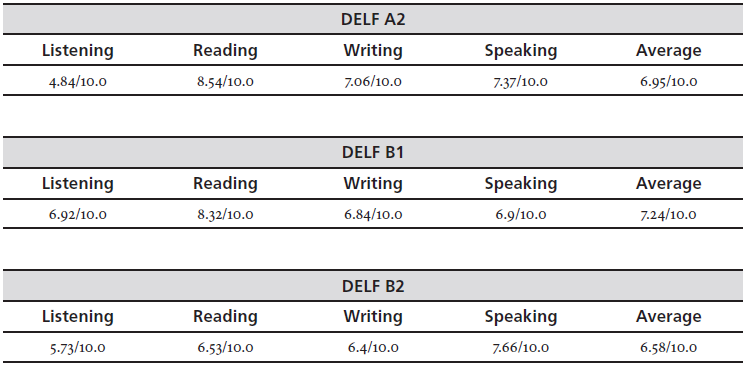

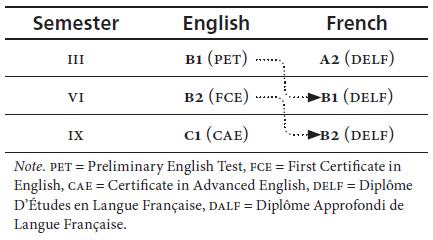

In exploring the mock examinations, the results confirmed a low proficiency level of learners in semesters III, VI, and IX. Moreover, these results indicated higher passing grades of learners majoring in French than learners majoring in English. Table 1 may explain the varied results of English and French examinations:

Table 1. Proficiency Levels of Mock Examinations

As shown in Table 1, there was a mismatch between the proficiency levels of the mock examinations in English and French. Learners in semesters III and VI took English examinations whose proficiency levels were B1 and B2, whereas learners majoring in French took examinations with equal proficiency levels but in semesters VI and IX. The immediate issue that emerges from this evidence is that learners majoring in English or French were set unequal linguistic goals, as indicated in Table 1. It is thus likely that learners after taking the teacher/translator training programme in this context develop different levels of English and French proficiency. It is interesting that some participants were aware of this mismatch, for example:

Extract 5

I think that students are achieving higher proficiency levels in French than in English . . . we have spotted a tiny mistake in placing [students] in a B2 level when their level is B1 and maybe this makes them believe that they have a high level. (Teacher 7, English)

As suggested in Extract 5, it seems that learners majoring in French were obtaining higher results, but from a lower proficiency level than learners majoring in English. The results of the mock examinations also showed low learner participation (see Appendix C). The implication of low learner participation in these exams is that learner achievement in general cannot be determined with accuracy. However, based on the results of the learners that participated in these exams, it is apparent that the linguistic goals stipulated by the curriculum were not met. Mentioned by three administrators, the low learner achievement hinders learners from obtaining an international language certification that demonstrates, at least, a proficiency level of B2, the minimum proficiency level required to work as language teachers in many schools in Mexico, as suggested in Extract 6.

Extract 6

It is a problem that there are students and graduates who cannot work because of their [low] proficiency level and we have to do something. (Administrator 13)

This evidence not only highlights the community’s failure to meet the linguistic goals stipulated in the curriculum, but also raises the need for alternative strategies or actions in FLP, as suggested by Baldauf (2004).

As discussed previously, the evidence shows that the learners’ proficiency was generally low and in contradiction with the stipulations of the curriculum. It is possible that the low proficiency levels are largely influenced by the learners’ failure to carry out actively learning-related practices outside the classroom, as consistent with Baldauf and Kaplan’s (2007) contention. The Faculty of Languages has tried to promote learner autonomy outside the classroom by encouraging learners to carry out a self-study of two hours for each hour in language classes, that is, if learners study the language for six hours in classrooms, they are expected to practise it for 12 hours on an autonomous basis, as suggested in Extract 7.

Extract 7

We reduced the class hours so that students work autonomously because they are required to obtain a certain proficiency level. This decision would motivate them to use the self-access centre or carry out study by themselves. (Teacher 1, English)

However, learners were considerably perceived by the participant teachers and administrators not to carry out these autonomous learning practices. This shortcoming was felt by Teacher 9 (French) as follows.

Extract 8

We are not promoting learner autonomy correctly because the student goes to the self-access centre because his teacher asked him to go; not because he wants to go there and practise.

In Extract 8, Teacher 9’s statement suggests the feeling that learner autonomy inside and outside the language classroom has not been promoted as expected. Moreover, she suggests the feeling that learner autonomy is not effectively encouraged when learning practices are imposed upon learners. The lack of learner autonomy was corroborated by eight participant learners who admitted that they only practised the foreign language in classrooms. In exploring the reasons that motivated the lack of learner autonomy, 60% of the participant learners felt that it was a consequence of a “great amount of workload” that they have every semester, but also their “irresponsible attitudes,” as admitted by Learner 4 (French):

Extract 9

I do not think that there is a lack of promotion. I do believe that students are not interested in using those resources.

In response to the aforementioned limitations, 45% of the informants (18 students, one teacher, and one administrator) suggested an alternative strategy, a foreign language immersion which involves the whole community speaking the foreign languages inside and outside classrooms in order to promote learner involvement and autonomy. For example, Teacher 5 (English) recommends the following:

Extract 10

We need to re-implement that programme called “English Everywhere” and try other activities. And we, as administrators and teachers, need to speak English or French.

The shortcomings of the FLP concerning learners’ low language achievement may also be a consequence of the considerable emphasis placed on strategies for teaching practices, without taking into consideration learning-related practices, attitudes, and perceptions. This suggestion is supported by the participant teachers’ perceptions that agreements and decisions during the official meetings run by the administration mostly centre on language teaching practices, implying a failure to include in the FLP actions associated with learners’ attitudinal, perceptual, and interactional behaviour inside and outside the classroom, as suggested in Extract 11.

Extract 11

Sometimes I think that [FLP] is not working, taking into account that each student is different. Despite the fact it is been carried out, I believe that learners should be considered in the decision-making of those meetings. (Teacher 7, English)

This evidence reveals the need to address these limitations and incorporate them into the FLP since learners, as foreign language speakers, are ultimately the target of the current FLP (Cooper, 1997).

When asked about their perceptions as regards the foreign language classes, 58% of the informants (involving all the teachers and three learners) believed that there were class time constraints which limited the opportunities to integrate the four language skills and thus affected learner achievement, as suggested by Learner 9 (English) in Extract 12.

Extract 12

Maybe [the administrators] should extend the class hours because sometimes we just practise grammar topics. We should also practise the four skills. They should not reduce them; they should increase them.

In this faculty, the class time for the foreign languages ranges from five to six hours per week. The informants mentioned that the class time was reduced by breaks of ten minutes per each hour of class that are given to learners, and extra activities (e.g., conferences, presentations, events, etc.) which require both teachers and learners to attend. As a consequence, 25% of the participant teachers and 25% of the participant administrators suggested that the class time for the foreign languages be increased by eight to 15 hours per week, as suggested by Administrator 11.

Extract 13

We should use the previous schedule. That is to say, we should increase the number of class hours. Six hours are few, in my opinion. I think that the hours for language classes should be eight or ten as in the old schedule.

It is important to note that in the previous programmes, the class time for the foreign languages was about 20 hours per week, but learners were still perceived to develop low proficiency levels.

Besides class time constraints, most of the participant learners felt that the classes were not attractive or dynamic, displaying negative attitudes towards the teaching approaches that were adopted in the classrooms. In line with these perceptions, Watts (as cited in Coupland, Sarangi, & Candlin, 2001) raises the possibility that strategies as part of LP may not yield the expected outcomes if users or speakers do not endorse them as part of their interests. The participant learners felt that the unattractive teaching approaches that were adopted in the classroom resulted in low learner motivation towards learning the foreign language as follows.

Extract 14

[Language teachers] should make their best to keep students motivated regarding learning the language because we all began the semester feeling motivated and then we start feeling demotivated. Then, they should find other strategies for their teaching methods. (Learner 3, English)

In Extract 14, Learner 3 suggests an interplay between learner motivation and language achievement which has long been the focus of language education research. However, this learner’s statement is not clear as to the source of learners’ low motivation concerning teaching practices. Nine of the participant teachers felt that learners’ low motivation was caused by a reliance on textbooks, as cautioned by Terborg, García Landa, and Moore (2006). According to the participant teachers, it is the administration which has imposed the use of textbooks despite the fact that the content of the textbooks is not related to the objectives of the curriculum. In response to this reliance, 66% of the participant learners suggested that too much emphasis should not be placed on textbooks while practising the languages, and that these resources should be used as support materials.

Moreover, 27% of the participant learners felt that low learner motivation was a consequence of the grammar practice that has dominated the practice of the language skills. This idea is supported by Learner 10 (French), as suggested in Extract 15.

Extract 15

Teaching and learning grammar should not be the main objective in our classes because there are other important language areas.

In response to this, the participant learners suggested that an integration of language skills is promoted in language classes without prioritising grammar.

It is apparent from the above evidence that there is a need to evaluate continuously the effectiveness of decisions and strategies in the FLP, and to suggest alternative actions which will ensure the achievement of learners’ foreign language competence. However, in this context, exploring the implementation and effectiveness of strategies inside classrooms may be limited by the teachers’ “teaching freedom”(libertad de cátedra in Spanish) which is promoted across the university. The teaching freedom enables teachers, using their discretion, to adopt the teaching approaches that they consider effective in promoting language learning. This also implies that the teachers’ teaching behaviour inside the classroom cannot be influenced or imposed upon. Administrators and language teachers claimed that the effectiveness of strategies was thus assessed through teachers’ comments on and discussions about the strategies during the official meetings. In order to continuously evaluate the FLP, some administrators and teachers suggested that peer classroom observations are carried out in order to determine the effectiveness of both teacher- and learner-related strategies inside the classroom strategies. This strategy would not restrict teachers’ teaching freedom since it would be carried out as onlooker (non-participant) classroom observations with a view to enhancing teaching and learning practices.

In this higher education context, different resources and spaces are at the learners’ disposal to develop their four language skills, grammar, and vocabulary. For example, there is a self-access centre where a number of materials (aural, visual, and written) are available to learners. Other resources include: Language workshops where learners are encouraged to practise and develop the four language skills; international visiting assistants with whom they can practise the communicative aspect of English and French; and the library where learners have access to research and teaching literature in English and French. The possibility of practising the target languages is acknowledged by Learner 7 (English) in Extract 16.

Extract 16

Here in the faculty, there are different resources. Workshops are carried out to promote each of the language skills in English or French, or conferences during which you receive suggestions on what to do.

These resources are in line with González et al.’s (2004) recommendation that learners should be provided with the resources and spaces where they can develop their language skills.

However, despite the range of materials, activities, and spaces that are available to learners in this context, 52% of the participants claimed that learners’ involvement and use of these resources were generally low, as suggested in Extract 17.

Extract 17

I think that they [students] do not participate as they should. I think that they are not taking advantage of the resources, and it is not the teachers’ fault. (Teacher 3, English)

Some of the participant learners felt that the main reason of learners’ low involvement was again time constraints, as stated by Learner 11 (English).

Extract 18

I sometimes do not use the resources because of time constraints. I have been interested in attending the workshops with the American girls, but I have not had time.

This evidence thus suggests shortcomings of the FLP which caused heavy workloads on learners, hindering them from promoting autonomy, involving abilities, language skills, time management skills, and the like. In response to this, a participant teacher suggested that time frames, namely, between 12:00 and 13:00, are established during which learners are free to practise the language skills that need to be improved. However, it may not be an effective strategy since the participant learners’ responses suggested perceptions that indicated negative attitudes towards the imposition of activities outside the classroom. Rather, their responses suggested an endorsement for language practice outside the classroom on an autonomous basis, as suggested in Extract 19.

Extract 19

I ask my students to do extra activities on something that they like in order not to impose the activities. They practise activities of skills they need to develop. I try to encourage this because I know that if there is something in which they do not like, they are not going to be interested. Then, I try to motivate them. (Teacher 10, French)

The above evidence suggests that the Faculty of Languages provided learners with the resources where they could develop their foreign language competence. However, possibly motivated by heavy workloads on learners, there was a perceived low learner involvement in these resources. This perceived low learner involvement links back to the lack of learner autonomy inside and outside the classroom. Again, it seems possible that learner autonomy and achievement are enhanced if the strategies in FLP take into consideration the learners’ perceptions, and are formulated towards the enhancement of learning practices inside and outside the classroom.

In sum, the evidence indicated that the learners’ proficiency level was low. This evidence appeared to be in contradiction with the objectives of the curriculum. In exploring the learners’, teachers’, and administrators’ perceptions concerning FLP, the evidence suggested that FLP decisions and strategies are implemented to meet the linguistic goals of both the foreign languages. However, as reported by the participant learners and some teachers, it seems that the learners’ voices and perceptions were not being included as part of the FLP processes. This was to some extent based on the learners’ feelings that the decisions and strategies in FLP were centred on teaching practices, suggesting in turn a failure to consider and evaluate learning practices. It is possible that the emphasis on decisions and strategies related to teaching practices resulted in low learner motivation and autonomy. Based on this evidence, we thus call for decisions and strategies involved in FLP work which take into account learners’ perceptions and opinions in order to ensure their endorsement and thus their effectiveness to promote foreign language competence.

The primary aim of this paper was to explore and evaluate the FLP that the Faculty of Languages at the UAEM carried out to meet the linguistic goals stipulated in the curriculum. As a starting point, the explorations of the FLP, firstly, considered the results of English and French simulated proficiency exams that this educational context administered to determine learners’ foreign language competence. The explorations then examined perceptual data in order to develop a better understanding of the FLP strategies and decisions and their effectiveness in promoting learner achievement.

The evidence indicated that learner achievement in three semesters was generally low. Secondly, it showed a mismatch between the proficiency levels that learners majoring in English and French were expected to develop. In exploring the learners’, teachers’, and administrators’ perceptions regarding FLP, the evidence suggested that there were shortcomings in the decisions and strategies concerning teaching and learning practices which, in turn, influenced learner achievement, attitudes, and autonomy.

The above evidence highlights the importance of formulating alternative strategies in order to ensure learners’ language achievement. Thus, in addressing the third research question (“What alternative actions should be taken into account by the community in order to ensure the effectiveness of the FLP and thus language learner achievement?”), this community needs to ensure that alternative strategies are designed to enhance both teaching- and learning-related practices inside, as well as outside, classrooms. In particular, subsequent strategies in the FLP should take into account the teachers’ and learners’ perceptions of the processes involved in teaching and learning the foreign languages. This may, firstly, guarantee that the strategies designed following their voices and perceptions are implemented by teachers and learners inside the classroom. Secondly, the teachers’ and learners’ endorsement for these strategies may in turn result in enhanced learning practices which can be extrapolated to environments outside the classroom with a view to promoting learner autonomy.

The contribution made by this paper was threefold: Firstly, the evidence showed that in order to ensure the effectiveness of an LP, there is a need for continuous evaluations which explore the implementation of decisions and strategies. Secondly, alternative actions need to be formulated in cases when strategies appear to be rejected by the speech community. Thirdly, all the members’ voices and perceptions of the processes should be taken into consideration in order to formulate (alternative) strategies which may result in a greater endorsement and thus effective implementation in the speech community, in this case, the Faculty of Languages at the UAEM.

Amorós, C. (2008). Diferentes perspectivas en torno a la planificación lingüística. In I. Olza Moreno, M. Casado Velarde, & R. González Ruiz (Eds.), Actas del XXXVII Simposio Internacional de la Sociedad Española de Lingüística (SEL) (pp. 17-29). Pamplona, ES: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Navarra.

Baldauf, R. (2004, May). Language planning and policy: Recent trends, future directions. Paper presented at the American Association of Applied Linguistics Conference, Portland, US. Retrieved from https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:24518.

Baldauf, R. B., & Kaplan, R. B.(2007). Language planning and policy in Latin America: Ecuador, Mexico, and Paraguay (Vol. 1). Clevedon, US: Multilingual Matters.

Berg, B. L. (2009). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (7th ed.). Boston, US: Pearson Education.

Cooper, R. L. (1989). Language planning and social change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cooper, R. L.(1997). La planificación lingüística y el cambio social. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Coupland, N., Sarangi, S., & Candlin, C. N. (2001). Sociolinguistics and social theory. London, UK: Pearson.

Fierman, W. (1991). Language planning and national development: The Uzbek experience. Berlín, DE: Mouton de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110853384.

Fishman, J. A., Das Gupta, J., Jernudd, B. H., & Rubin, J. (1971). Research outline for comparative studies of language planning. In J. Rubin & B. H. Jernudd (Eds.), Can language be planned? (pp. 293-305). Honolulu, US: University of Hawaii.

Gadelii, K. E. (1999). Language planning: Theory and practice. Evaluation of language planning cases world-wide. Paris, FR: UNESCO.

García Ponce, E. E. (2011). Planificación de lenguas extranjeras en la Facultad de Lenguas de la UAEM (Unpublished master’s thesis). Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, Toluca, Estado de México.

González, R. O., Vivaldo J., & Castillo, A. (2004). Competencia lingüística en inglés de estudiantes de primer ingreso a instituciones de educación superior del Área Metropolitana de la Ciudad de México. México, D.F.: Unidad Autónoma Metropolitana.

Haugen, E. (1966). Language conflict and language planning: The case of modern Norwegian. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674498709.

Mesthrie, R., Swann, J., Deumert, A., & Leap, W. (2009). Introducing sociolinguistics (2nd ed.). Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

Moreau, M.-L. (1997). Sociolinguistique: Les concepts de base. Sprimont, BE: Mardaga.

Payne, M. (2007). Foreign language planning: Towards a supporting framework. Language Problems and Language Planning, 31(3), 235-256. https://doi.org/10.1075/lplp.31.3.03pay.

Terborg, R., García Landa, L., & Moore, P. (2006).The language situation in Mexico. Current Issues in Language Planning, 7(4), 415-518. https://doi.org/10.2167/cilp109.0.

Tollefson, J. W. (1994). Planning language, planning inequalities. London, UK: Longman.

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, UAEM. (2010). Curriculum de la licenciatura en lenguas. Toluca: Author.

Weinstein, B. (1980). Language planning in Francophone Africa. Language problems and Language Planning, 4(1), 55-77. https://doi.org/10.1075/lplp.4.1.04wei.

Virna Velázquez is a professor at Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. She holds an MA in applied linguistics (UAEMex) and a PhD in linguistics (UNAM). She has published articles related to the indigenous languages situation in Mexico. Her research interests include sociolinguistics and second language acquisition.

Edgar Emmanuell García-Ponce teaches in the MA in applied linguistics in ELT program in the Departamento de Lenguas, Universidad de Guanajuato. He holds a PhD in ELT and applied linguistics from the University of Birmingham, UK. His research interests are centred on the interplay between classroom interactions and teacher and learner beliefs.