Students and Teachers’ Reasons for Using the First Language Within the Foreign Language Classroom (French and English) in Central Mexico

Keywords:

First language use, qualitative research, students and teachers’ points of view. (en)The present study explores the use of the first language in a context of foreign language teaching. This qualitative research presents the classroom practice and points of view of French and English teachers and students within a public educational institute in central Mexico using the techniques of questionnaires and semi-structured interviews. The results show that teachers and the majority of students perceive the use of the first language as positive and part of the teaching and learning process. A small number of students do not like the use of the first language in the classroom and prefer that their teachers use the target language only.

La presente investigación explora el uso de la lengua materna en un contexto de enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras. Esta investigación cualitativa presenta la práctica docente y los puntos de vista de maestros y alumnos de francés e inglés en el contexto de una universidad pública del centro de México, mediante el uso de las técnicas del cuestionario y la entrevista semiestructurada. Los resultados muestran que tanto los maestros como la mayoría de los alumnos perciben el uso de la lengua materna como algo positivo en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje. Un número reducido de estudiantes rechaza el uso de la lengua materna y prefiere que su clase de lengua extranjera sea dirigida exclusivamente en la lengua meta. Palabras clave: investigación cualitativa, puntos de vista de alumnos y maestros, uso de la lengua materna.

Students and Teachers' Reasons for Using the First Language

Within the Foreign Language Classroom (French and English)

in Central Mexico

Razones de alumnos y maestros sobre el uso de la primera lengua en el salón

de lenguas extranjeras (francés e inglés) en el centro de México

Irasema Mora Pablo*

M. Martha Lengeling**

Buenaventura Rubio Zenil***

Troy Crawford****

Douglas Goodwin*****

Universidad de Guanajuato, Mexico

*imora@ugto.mx **lengelin@ugto.mx

***rubiob@ugto.mx ****crawford@ugto.mx

*****goodwin@ugto.mx

This article was received on December 2, 2010, and accepted on May 14, 2011.

The present study explores the use of the first language in a context of foreign language teaching. This qualitative research presents the classroom practice and points of view of French and English teachers and students within a public educational institute in central Mexico using the techniques of questionnaires and semi-structured interviews. The results show that teachers and the majority of students perceive the use of the first language as positive and part of the teaching and learning process. A small number of students do not like the use of the first language in the classroom and prefer that their teachers use the target language only.

Key words: First language use, qualitative research, students and teachers' points of view.

La presente investigación explora el uso de la lengua materna en un contexto de enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras. Esta investigación cualitativa presenta la práctica docente y los puntos de vista de maestros y alumnos de francés e inglés en el contexto de una universidad pública del centro de México, mediante el uso de las técnicas del cuestionario y la entrevista semiestructurada. Los resultados muestran que tanto los maestros como la mayoría de los alumnos perciben el uso de la lengua materna como algo positivo en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje. Un número reducido de estudiantes rechaza el uso de la lengua materna y prefiere que su clase de lengua extranjera sea dirigida exclusivamente en la lengua meta.

Palabras clave: investigación cualitativa, puntos de vista de alumnos y maestros, uso de la lengua materna.

Introduction

Historically the use of students' first language (L1) has been looked upon negatively or even somewhat frowned upon due to Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) or even the Audio-Lingual Method (Stern, 1991). Some teachers would demand students not use the L1 and even at times reprimand its use. Many times these teachers felt that the 'English only' or L2 rule would benefit their students' learning process (Cook, 2001). This is the case being explored here in central Mexico.

Some language methodology books briefly discuss how L1 can be used in the foreign language classroom. These books tend to give friendly advice to the teacher or future teacher as how to handle the use of L1 (Fournier, 1990; Lado, 1990). This information at times seems to be lacking in theoretical backing and could be questioned as to its reasoning (Gower & Walters, 1983; Lewis & Hill, 1993; Swain & Lapkin, 2000). It is more practical information, perhaps, where teachers are often recommended and prescribed to not use L1 or only use L1 sparingly in their instruction. However, the philosophical reasoning behind these ideas is not explored in depth.

One should also consider how the profession and educational institutions have viewed the use of L1 in its history. Likewise, it is necessary to consider the extent of the evolution of our understanding of the use of L1 as well as how to use it throughout the years (Richards & Rodgers, 1986).

This article presents the findings of a research project of French and English language teachers and students' reasons for using the L1 within the context of a public university in central Mexico. The goal of this research is to explore these reasons as to whether they use or do not use L1 and perhaps to what extent this has an impact on the teaching and learning processes. We, five researchers working at the same university for a number of years, are aware that L2 is the goal we have as language teachers and for our teachers, the L1 can be one tool in order to reach this goal of L2.

Research has been carried out to establish what the functions and quantities are for the use of L1 in ESL contexts such as immersion programs. Yet little research has been carried out concerning how teachers and students perceive the use of L1 and why they include or exclude it. We are looking specifically at an EFL context where both participants (teachers and students) in essence share two languages (L1 and L2). It is our belief that it is important to value the use of L1 and understand more fully what teachers and students believe concerning the use of L1. This information will shed light on their points of view regarding its use and the reasons they use or do not use L1 in the teaching/learning processes.

Our Interest in this Research

In our practice as teachers we are aware that L1 is part of our teaching and how perhaps we should re-examine the use of L1 to fully understand the complexities of its use. We have witnessed pedagogical techniques applied at our institution or used by teachers we have heard about to fine students a small amount of money for using L1. Also, a reward system of points or candy has been utilized by teachers for students who only use L2. This may be considered a 'dominate discourse' because they force students to use L2 but perhaps more examination of these practices should be done. While this may seem friendly and harmless advice to teachers, what is evident is the hidden agenda behind such practices and this is what we are trying to explore. One may question these practices and wonder if the consequences are fully understood as to what these practices imply. When one thinks of these small gestures, one may see there is a power relationship between the teacher and students where the teacher holds the power. These are only a few examples as to how the use of L1 may be seen within our profession and the reasons that we want to explore this phenomenon in the classroom practice.

Overview of EFL and ESL studies of L1 Use

For the overview, we will begin to look at how L1 has been seen throughout the years. Brooks-Lewis (2009) describes how different methods and approaches have dealt with the use of L1 in the classroom. The Grammar-Translation Method was formally developed in the 18th century and its main objective was mainly to study grammar in detail and translate texts from the original into the learner's language. The teacher did not have to be able to speak the target language in order to teach (Lindsay & Knight, 2006, p. 15). Then The Direct Method was developed in the early 20th century in order to overcome the problems connected with grammar-translation. It moved away from translation and introduced the idea of lessons being conducted only in the target language (Lindsay & Knight, 2006, p. 16). From the Direct Method to the Natural and Audio-Lingual Approaches to CLT, Brooks-Lewis pedagogically explains how L1 has been viewed with phrases such as "limited use", "interference", "exclusion of the L1" and "L1 is extraneous" (pp. 3-4). Auerbach (1993) also provides information on the history of the 'English-Only Roots' (pp. 12-14) of an ESL context. These key phrases make us realize the importance of looking at the issue from a deeper perspective. Both authors provoke the foreign language teaching profession to rethink the use of L1 regardless of their context.

We shall look specifically at the CLT because it has influenced our context for a number of years. CLT is very widely used in teaching all over the world. It has shifted the focus in language teaching from learning about the language to learning to communicate in the language. However, one of the problems associated with CLT is that the emphasis on pair and group work can create problems in some classes. Some learners, particularly adults, think it is a waste of time talking to other L2 speakers rather than a native-speaker teacher (Lindsay & Knight, 2006, p. 23).

CLT does not make use of L1 but perhaps it is frowned upon and students are encouraged to use only L2 within the classroom. The idea behind this methodology may be that the student should be immersed in the learning of L2 and avoiding L1 is a way to do so. This immersion is thought to be better for the student so the teacher tries to create a classroom environment where L1 is prohibited, hoping the students will use more L2. In retrospect, this type of thinking may carry aspects of control and power on the teacher's part (Brooks-Lewis, 2009; Hedge & Whitney, 1996). The enforced "naturalness" of students speaking English gives the teacher control in many situations where it would otherwise be difficult (Lewis, 1993, p. 10).

This study was carried out in an EFL context which is different from other studies such as those by Cook (2001) and Storch and Wiggleswork (2009), which are based on studies in ESL. Cook (2001) explores how L1 is used in the classroom yet what is evident is that his study refers to the use of L1 in the ESL context. Other studies concerning the use of L1 deal with a Spanish class in Puerto Rico (Schweers, 1999), French immersion program using Task-Based Learning in Toronto (Swain & Lapkin, 2000), the use of Arabic in an elementary English language classroom in the Muscat Region of Oman (Al-Hinai, 2006), a Spanish class at Montclair University (Edstrom, 2006), a Task-Based classroom in Hong Kong (Carless, 2008), and with ESL university learners in Australia (Storch & Wiggleswork, 2009). From the abovementioned studies we can see a variety of contexts and languages such as Arabic, French and Spanish and also a growing interest in the area of the use of L1. Atkinson (1987) makes a point that the use of L1 is somewhat overlooked within the pedagogical and training discussion and suggests a "postcommunicative approach which includes a more positioned and valued use of L1" (p. 241). This shows how the status of L1 use has evolved even more from the beginnings of CLT.

There has been previous research on how teachers use L1. Edstrom (2006) cites the work of Polio and Duff Duff (1994) concerning the use of L1 and provides eight categories:

...classroom administrative vocabulary, grammar instruction, classroom management, empathy/solidarity, practicing English, unknown vocabulary/translation, lack of comprehension and an interactive effect in which students' use of the L1 prompts their instructor to use it. (Edstrom, 2006, p. 278)

Rolin-Ianziti and Varshney (2008) also mention a number of functions such as imparting knowledge concerning the L2 medium, classroom management, anxiety, and motivation (positive and negative).

The reasons that teachers may use L1 vary due to the students' level of language proficiency and the institutional curriculum. It seems that more L1 is accepted at lower levels of proficiency and gradually the use of L1 is reduced according to the higher level of proficiency.

Research Questions

The research questions used in this project were the following:

- What are the reasons why teachers and students use (or do not use) L1?

- How do these reasons impact the teaching-learning processes?

Methodology

Qualitative research was used within this project in order to explore reasons that teachers and students may or may not use L1 in the foreign language (French and English) classroom and their points of views. Qualitative research "seeks to understand the meanings and significance of actions from the perspective of those involved" (Richards, 2003, p. 10). In this research we are looking at the points of view of teachers and students concerning the use of L1 and the rationale for its use. Denzin and Lincoln (1994) define qualitative research as:

... [a] multi-method in focus, involving and interpretive, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of or interpret phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. (p. 1)

In this study, we wanted to explore the teachers and students reasons for using (or not using) L1 in the classroom. As such we are developing themes for the purpose of analysis under the concept of 'thick description'. Thick description is taken from the philosopher Gilbert Ryle in his parody of the two boys winking; as such, we adhere to the formal definition by Denzin (1994):

A thin description simply reports facts, independent of intentions or circumstances. A thick description, in contrast, gives the context of an experience, states the intentions and meanings that organized the experience, and reveals the experience as a process. (p. 505)

So, we reveal our experiences, the institution's as well as the participants', in showing through the use of thematic thick description this process of the role of L1 emerging and impacting our programs. In this research we explore and survey two social groups (teachers and students) within a shared context in which we, the researchers, also are part of the social group of teachers. Our participation includes the 'insider' perspective, which also is part of the qualitative paradigm (Blaxter, Hughes & Tight, 2006, p. 65). In the following section we will present the participants, the techniques and the data analysis process.

Participants of the Study

The number of participants was eight teachers (three French and five English) and one hundred and twelve university students (50 French and 68 English) between the ages of 18 and 26 years old. The majority of them was pursuing bachelor degrees in a variety of degree programs of the university and were studying in a range of language levels (beginners, intermediate and advanced). Concerning the teachers, two of the French teachers were native speakers and one was a non-native Mexican French teacher with a range of five to fifteen years of experience. The two native speaker French teachers had taught all their teaching years at the university level while the non-native teacher had taught at an international French school and at the university. Regarding the five English teachers, there were two native speaker teachers (twenty years and five years of teaching experience) and three non-native English teachers (two Mexicans and one French Canadian) with a range of five, twenty and twenty two years of teaching at university and primary school levels. All of the teachers taught a variety of levels: beginner, intermediate and advanced. The selection of participants was based upon providing a range of teachers and students. All the participants were explained the research objective and given the opportunity to participate or decline. Consent forms were given to the participants who accepted and pseudonyms were used.

Techniques for Data Collection

The two techniques used to collect the data were interviews and questionnaires. Interviews were chosen as a way to create a space for conversation between the English or French teacher. Specifically, we used semi-structured interviews with a number of questions (see Appendix A ) to guide the dialogue between the interviewer and teacher participant, yet we also tried to let the interview evolve depending on the interviewee's responses. Regarding the student questionnaires, they were used as an efficient way to obtain data from a large number of students to better represent their positions (see Appendix B). We asked permission to give out the student questionnaires near the end of the class while the interviews were held individually in the researchers' offices. Concerning the use of language, the questionnaires were given in the students' native language -Spanish- while the interviews were carried out in French, English or Spanish depending on the teachers' preference of language. For this article the data is presented in English and translation was carried out by the researchers and four BA in TESOL students at our university who received a small scholarship from the university. Both the interviews and questionnaires were collected during the school year 2009.

The following is the process we followed for the data analysis:

- The data were collected from the students and teachers and coded. The coding of these collection techniques used "I" for teacher interviews and "Q" for student questionnaire and also a number to represent the individual.

- Interviews were transcribed and translated.

- All of the five researchers as a group read the data and discussed the data for general interpretation.

- The data were divided into five groups and each researcher was given two groups of data to analyze individually.

- Two researchers of the same data groups shared their analyses and came up with emerging themes.

- All of the researchers then discussed and identified the final emerging themes. Based upon the above description of the data analysis, we shall now present the emerging themes.

Main Findings

The findings shall be divided into two sections: the teachers' points of view and the students' perspectives. These two perspectives are aimed at providing an in-depth analysis of the phenomenon of L1 use in the language classroom by the two major groups of participants. It should be mentioned that the results for French and English were very similar and did not seem to affect the results. In essence, the data of both groups referred to the teaching-learning process.

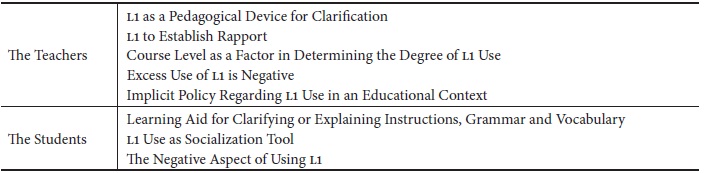

Table 1 presents the findings that will be discussed.

Table 1. Teachers' Points of View and Students' Perspectives

The Teachers

Concerning the teachers, six primary themes emerged from the interview data and provided insight as to how the teachers used L1 in the language classroom. It is worth mentioning that the data collected in this study suggest that all of the participating teachers accept that they use and allow the use of L1 in their classrooms to different degrees, depending upon various factors. The following are their reasons that teachers use L1. Through these themes we will also show the classroom practices and points of view of the teachers.

L1 as a Pedagogical Device for Clarification

Teachers indicate that they employ L1 as a teaching tool for explaining aspects within the classroom such as instructions, grammar, unfamiliar vocabulary and expressions. According to the data, Spanish is used in the classroom in order to save time and avoid lengthy explanations in the target language and to avoid 'interrupting' the pace of their lessons.

For me it's much easier to return to Spanish. Students were asking me about the 's' ending...and I explain it in Spanish because it would take me hours to explain it in English! (I1)

[L1 is used for]...certain words or expressions in order to keep the moment going of an activity...it really depends on the circumstances of when I use it [L1]. (I2)

I think it is essential in some cases to explain some things in Spanish, because even if you give examples or do pantomime there are certain grammatical points that are very difficult for students to understand in spite of similarities between the languages. (I3)

The above quotes illustrate how in primarily teacher-initiated exchanges the teacher has decided to use L1 in order for the learners to better understand specific aspects of a class. These quotes also show how teachers are conscious of their decision making. On the other hand, some teachers incorporate L1 in their classes in order to provide a comparative analysis of the languages, as the following excerpt shows:

...comparisons between French and Spanish are quite close. I have them reflect, and if I use Spanish, I tell them to look at the phrase and think about how it would be said in Spanish. And from there we proceed and they notice how to say it in French. What matters is that they perceive the similarities between the two languages. (I4)

The above excerpt suggests that the teacher does not necessarily initiate communication with L1, but rather elicits L1 from the students in order for them to use it as a means of comparing aspects of both languages so they may use their own language for their learning experience and cognitive skills to help in the acquisition of the target language. The relevance of this quote rests in the fact that this particular use of L1 encourages the active participation of the students, whereas the teacher takes on the role of facilitator. It also represents a use of contrastive analysis which is used as a noticing activity of notification.

L1 to Establish Rapport

A number of data showed that teachers use L1, or they believe it is necessary to speak in Spanish, in order to establish a connection with students at the outset. This rapport is also a means for establishing empathy with their students, especially since some of the native speaker teachers who participated in this study mentioned having had the same experiences when they learned Spanish. The following data exemplifies this:

kind of bond, make a connection with their students...just like chit chat with them...like about the weekend or something... I want to ask them about what they did on a holiday weekend and I know they can't tell me in English, I'd ask and let them tell me in Spanish like before the class or something. (I3)

There are times when I tell them jokes out of the blue or when class is over and I tell them "Class is over and I am going to tell a joke" and I switch to Spanish...there are silly jokes but most of them laugh and that is how I gain their trust. (I5)

Both teachers coincide in that they use L1 to form a connection with students through the use of chitchat or jokes and they make a choice of language to establish rapport in their classrooms. In doing so they attempt to lower the students' affective filters to create a learning environment where they feel more at ease and have more confidence speaking and participating in class. Also worth noting is that both teachers indicate the use of L1 for establishing rapport usually at the beginning or end of a class, which suggests that they perceive the use of L1 as a tool that can be used for different purposes at different times in the foreign language classroom. As a side issue related to rapport there are data to suggest that teachers use L1 to show empathy. Both empathy and rapport have a connection because they look on the side of the students and a way to promote a better teaching-learning environment.

I explain and I say to students that I know it's not easy, I experienced the same as they did. I always speak of my experience because English wasn't easy for me, no it wasn't, I didn't like it. (I1)

By sharing this non-native teacher's personal experiences in learning the target language, she demonstrates to her students that she knows what challenges and obstacles they are facing in their learning process. This knowledge is not only beneficial in that the teacher is more sensitive to the students' learning needs and struggles, but it is also a positive factor for students to feel more comfortable and motivated in their language class. This might lead to an environment that is more conducive to successful learning. This teacher creates her rapport with her empathy of what students are facing.

Course Level as a Factor in Determining the Degree of L1 Use

While providing reasons as to why teachers used L1, an aspect that came up repeatedly was the level of L2. The students' language level seems to be important in order to determine the amount of L1 in class. Teachers agreed that the frequency of L1 use varied from one level to another, indicating that at lower (beginning) levels there was more acceptance of L1 in the classroom, while at higher levels they tended to prefer less use of L1.

Well, it all depends on the level...for example, with beginners it is different, with beginners when we begin lessons, we speak Spanish to explain how the class will function, but little by little I introduce French. (I4)

...by the third semester I used very little Spanish... Really, it was only so they could understand some tenses and they could know the meaning in Spanish of these tenses in French. But in the advanced levels, basically no [Spanish]...because we have synonyms in both languages. But with the beginners if you do not use their language, they get blocked, you begin to notice they are blocked and they don't improve. (I2)

These two excerpts indicate that the teachers are aware of the language level of their students and they have assessed how much and what type of L1 use should be permitted in their classes based on their students' language level. By consciously distinguishing between levels and the degree of L1 use for each, the teachers demonstrate how they are inserting their beliefs and criterion into the learning environment and thus keeping classroom decisions to themselves. There is a sense of teachercenteredness revealed here in that the students appear to have little or no control over their classroom activity, specifically in the area of L1 use yet it represents teachers who are making decisions.

Excess Use of L1 is Negative

Having looked at reasons for using L1, we are now going to look at reasons not to use L1. We are going to show two examples of this:

When I hear students are communicating in Spanish at a table, I point it out to them and criticize them for it. I don't tolerate it, especially when they are working in groups. With me it might work, or I might accept it, but in groups it is more interesting if they have no interaction in Spanish, not even for defining terms. I think it could be more harmful. During the group work I monitor all of the tables saying: "Oh! I can't hear the sweet sound of French here. What's going on? (I6)

In the above excerpt the teacher does not accept the use of L1 in groups, perhaps because he sees this as the only opportunity for students to speak in French. Even though he uses terms such as "don't tolerate" and "more harmful", in the end he thinks it is in the best interest of his students not to use L1. He also believes that the use of French is necessary for them to learn.

Another example of excessive use of L1 is presented by a teacher who believes that his use of L1 will benefit his students' learning, yet later he reflects on this negative overuse:

I just started teaching beginning levels and I found that I dug myself into a hole very quickly with the use of Spanish. They were a beginning level and instead of starting to explain everything in slow or simple terms, what I did automatically was assume that they were a beginning level. You know it's going to make it easier and the activity will be more successful if I start by giving the instructions in Spanish but the problem is now that with these groups I've been with several weeks they understand a lot of the expressions the instructions and everything but because I've depended on using Spanish so much that they expect it of me... (T3)

The teacher explains how he has used L1 and his overuse seems to have become a vicious circle and how the students expect it in the classroom. The students now seem to depend on this continued use of L1 which creates a problem and the use continues to occur in the classroom. He now realizes his problem which was based upon his own assumptions.

Students may depend on the native language if it is used a lot. Again, there is no reference to learning theories or classroom techniques that are valid in both senses. Here the only reference is that the teacher thought it would "make it easier" using Spanish. But we do not know if the teacher is thinking of himself or his students. What is interesting is that the teacher is reflecting on his teacher development, which shows a sensitive, astute and concerned teacher.

If we consider the two previous quotes, we find two underlying ideas that the use of L2 is 'more interesting' and the use of L1 "is easier". In both cases the issue is based upon the teacher's beliefs or assumptions. The conclusion of L1 or L2 is simply a personal teacher decision according to what is happening in the classroom. Learning does not seem to be an explicit issue. Another excerpt exemplifies this point as follows:

...now I have intermediate levels and advanced levels, with them I only use it [L1] when we are looking for the meaning of a word that is in a text and it is difficult for me to explain it with words or I don't feel like explaining it or drawing or mimicking depending on the word and if I need to go faster well I say the word in Spanish. (T4)

In the above quote, we can see that the teacher is making a decision about the use of L1 depending on the level. If it is a higher level, the teacher uses L1 to save time. The level of the language affects the teacher's decision in whether or not to use L1 and the amount of use.

Implicit Policy Regarding L1 Use in the Educational Context

In the following examples we can see how teachers use L1 based upon an implicit policy of the educational institution. These policies may be influential for the teachers' practice and may continue for many years. It is often the case that a teacher is told not to use L1 and this practice continues even when the prescribed methodology is not longer in use in the institution in the educational context.

What I feel is that because of the requirements in the program, up until now we have always been told not to speak Spanish, don't speak Spanish, don't speak Spanish in the classroom as such as French teachers we have always been restricted from using Spanish in the classroom, so we were always trying to use as little Spanish as possible in the classroom. (I3)

Well, first of all it [use of L1] is a problem. The written and unwritten law is: not a word of any language that is not French. (I6)

The use of Spanish, of anything written, nothing I'm familiar with but definitely unwritten, just to keep it limited, just to keep it limited but in terms of a policy that's not really much of a policy. There's nothing that says well that you should use it here or it could be helpful here. Its more no restriction, it should be limited to this...ok they should be using a minimum of their native language, you should be asking them to use English the majority of time instead of saying sort of having consent about you know when it is appropriate...(I2)

The teachers are not clear about an indication of a written document or an authority that has made such a statement concerning the use of Spanish, but it is clearly a dominant discourse of the school. As researchers and teachers who have worked at this institute for many years, we know there is not a document that prohibits the use of L1. Another teacher makes mention of an unwritten norm "but definitely unwritten". Finally, there is perhaps a statement of policy which is implied as: The written and unwritten law is not a word of any language that is not French.

In the above quotes one may think that these implicit policies could be seen as a dominant discourse of a type of methodology prescribed for the teachers. Whether a teacher decides to take on this dominant discourse or reject it could be a problem for the teacher or the institution in the actual teaching practice (Hedge & Whitney, 1996; Howarth, 2000; Mills, 1997). Dominant discourse may continue for many years until it becomes part of the teachers' belief system. By creating a dominant discourse that 'no Spanish' should be used in the classroom, the students are being 'socially depowered' in the sense that they are restricted as to what extent they can express themselves as individuals (Fairclough, 1989; 1992). This means that the teachers' classroom practice has a direct relationship on the use of their classroom language and in turn this affects how the students use or do not use their L1. In a sense, the students may be seen as controlled concerning their use of L1. Fairclough (1989, 1992) makes reference to the language (in this case the classroom language) being a part of a social and linguistic phenomena. Since the language of the classroom has been predetermined, perhaps this forces the student to modify their behavior and take on a new role in a different language and perhaps even a different identity. On the other side of the power balance the teacher is given a powerful tool that can be employed in many ways. Since the teacher is the only person who can fully use the language of the classroom, the teacher is in a position to exercise power.

This could be a potentially dangerous situation if the language is used for purposes other than learning. Unfortunately, the views expressed placing a negative view on the excessive use of L1 implies that the dominant discourse may be employed more as a tool of control rather than to make learning more salient.

The students are being socially forced to cross a linguistic barrier when they enter the classroom. As they cross the barrier they are restricted to the use of tools. But, we do recognize that students naturally use L1 mainly at beginning level.

The Students

The students' perspectives are presented based on three primary themes which emerged from the data. This data provided insight as to how the participating students viewed the use of L1.

Learning Aid for Clarifying or Explaining Instructions, Grammar and Vocabulary

This data seemed to be similar to that of the teachers. Students, for the most part, indicate the reason why they use L1 as a learning strategy during their classes. The first example shows how the use of L1 is employed when a student does not understand a structure in the classroom. In this example we can see that if the learner does not have enough vocabulary, she or he naturally switches to Spanish.

I use Spanish when I do not understand a phrase or structure to learn more. When I have enough vocabulary I do not speak Spanish. (Q3)

Well, we need it (L1) a lot, because there are phrases and sentences that we cannot easily understand. We need to speak a minimum of Spanish to advance in our target language.

I use it (L1) when I have a vocabulary doubt and it is necessary when the teacher is explaining grammar because it is easier to understand. (Q20)

When I use it, it is because I cannot find the right word in the foreign language...that I get the impression I am wasting time. (Q10)

These students mention how L1 is useful when trying to understand unfamiliar vocabulary, grammar or language. The teachers describe basically the same type of use for the same purposes. This particular use of L1 appears to occur spontaneously during the lessons, and there is no evidence to suggest that the practice is discouraged by teachers. Likewise, most students in this study seem to benefit from the use of L1, with a few exceptions which shall be discussed later in this section.

The last quote shows how the learner uses L1 for vocabulary-related purposes, but adds the notion of 'wasting time', which suggests a concern on behalf of the student for better pacing in the classroom. Also, the students and teachers alike place importance on the practicality and flow of their classroom activities. They seek to take advantage and optimize every minute of their one-hour class, trying to avoid unnecessary interruptions or delays with drawn out target language explanations or mimic.

The following data excerpt reveals the use of L1 as a learning aid. When I do not understand it is comforting, because otherwise I get stressed trying to understand what is being said and I don't get it. (Q43)

This student describes L1 as a tool that helps with understanding language components but more importantly as a means to reduce anxiety. However, these data also reveal the student's point of view of L1 as a means of reducing anxiety and stress which result from not understanding aspects of the target language during class.

L1 Use as Socialization Tool

In the questionnaires the majority of the students commented that the reason they use L1 is because it is a way to socialize with their classmates during the lesson. In the three excerpts below one can see how L1 is used to interact:

I try not to use it but it is mostly to talk with my classmates about the day. (Q27)

When I talk with my classmates about other things I mostly use Spanish. Most of the time it is used when the team finishes and other have not, you start speaking in Spanish. (Q58)

I use Spanish in most of the class, talking with my classmates. (Q17)

In the quotes, "talk with my classmates" is repeated three times and this represents a natural use of L1 with students' classmates in their native language, Spanish. This use of L1 when they are socializing in the classroom seems to be a common practice. This type of talk refers to the normal chit chat that one uses which is not related to language learning.

The Negative Aspect of Using L1

Within the data analysis there were a few excerpts concerning the negative aspect of the use of L1. In the four examples that follow we see an array of opinions concerning this:

I think it [use of L1] is illogical and clearly it is wrong because if we are in a foreign language class the last thing we want to do is speak Spanish. We need to learn the other language. (Q33)

When the teacher uses Spanish, well, I think that I do not learn much or that class was useless. (Q42)

Well, it bothers me because you are learning a language by practicing it and if you don't practice, you won't learn it. (Q19)

I think that it is important to not use Spanish in class, because it is a way to become familiar with the language - that way our ears can pick it up and our learning will be enhanced. (Q11)

In the first quote, the student makes a strong judgment on the use of L1 with phrases such as 'illogical', 'clearly it is wrong' and 'the last thing we want to is speak Spanish'. In the second excerpt the student uses the word 'useless', which might refer to an ineffective class. This student has a preference for a teacher who carries out the class in the target language. In the third excerpt the student makes a simple correlation between the use of L2 and learning L2: both go together. One could question this correlation. The last excerpt shows that the use of L2 should be employed in order to optimize the learning process so that the student is able to listen to the language. This seems to represents the probability that they may not have a lot of opportunities outside the EFL classroom. This is important in an EFL context when the target language is not used as much as in an ESL context.

When considering the students' points of view in relation to the use of L1, a very different picture emerges. Unlike the teachers that use L1 as a specific learning device or as an aid to bond with, the students use L1 for different reasons. They are summarized in the following three basic points:

- L1 is a specific learning tool exclusively for clarification of meaning.

- There is limited input of L2 in an EFL context compared to an ESL context.

- L1 is used for non-class related issues among the students.

This puts the L1 issue into a different realm. Here the students are taking agency for using their native language and determining its use. At the same time it creates an indirect conflict with the issues voiced by the teachers in the study. The majority of the teachers placed L1 in the area of a teaching tool for a variety of reasons, whereas the students consider it a learning tool, but only in one specific context, which is the classroom.

The students are using L1 mainly for clarification so that they may continue learning, whereas the teachers are saying it can be a learning tool for different functions or strategies. Another interesting aspect that arises is the issue of rapport. The teachers indicated that L1 was good for establishing a relationship; the students in the study indicate that Spanish is used for only their classmates and for social aspects.

Another aspect that is compelling is the students' idea that L1 is exclusively for outside the class conversation. This is interesting in that it falls in line with the unwritten rule of 'no Spanish' in the classroom. It is debatable as to whether this is a product of the students' development or if it is the assimilation of a wider institutional discourse or from their teachers. The comment made expressing that it is illogical to use Spanish in the classroom could imply that this is more the result of student discourse as opposed to an institutional one.

Conclusions and Implications

The reasons both French and English students and teachers in central Mexico use L1 in the teaching and learning processes were similar to the reasons that L1 was used in other studies such as Atkinson (1987), Cook (2001), and Harbord (1992). These uses are of positive value. Having finished with this research and reflecting upon our own teachers and students, we concur with Martin's (2001) call for 'a more comprehensive and flexible view of the role and possible use of L1' (p. 159) for practice and Cook's (2001) opinion that L1 should be viewed in a more positive light. In addition, Edstrom (2006) asks teachers to "reevaluate their moral obligations to their students and their objectives for the language learning process" (p. 289).

The reasons teachers and students use L1 concerning this research are multifaceted decisions that students make while being immersed in the teaching-language processes of the target languages. Both use L1 for reasons based upon their beliefs, assumptions, needs and desires.

Concerning practice, teachers in this study made decisions to use or not use L1 and these decisions were based upon their beliefs as teachers-what they felt was appropriate for the teaching and learning processes. These decisions were made at different parts of their teaching: before the teaching act, during the teaching act and even after something had happened in the class. This shows that teachers are responding to the teaching and learning processes and analyzing the use toward a variety of situations in the processes.

This information is of interest for current and future teachers of any language in either a target language or foreign language context because it shows the decision-making process of teachers and students and their functions. Knowing about this decision-making process has teacher training implications of consciousness-raising in order to promote a positive value toward the use of L1 as mentioned by Cook (2001). This consciousness-raising will allow teachers to question and make their own decisions as to how to use L1 in their classrooms. It will also help teachers understand that students' use of L1 is a natural part of the learning process. This reflective thinking will hopefully permit teachers to respond to their students' needs, to be more flexible and to explore their own belief systems.

More research in other EFL contexts could be carried out to see if the results are similar or even if there are other uses of L1. A comparison between EFL and ESL contexts could also be another aspect to research. EFL contexts usually have limited input of language while ESL contexts provide more input. In addition, EFL contexts for the most part are homogenous groups with one common language such as Spanish in this Mexican context. In ESL contexts teachers may have students who come from a variety of places; hence, their native languages are different. In both the EFL and ESL contexts the use of L1 is probably approached differently by the teachers and the students. Another option for further research could deal with the quantity of the use of L1 in regard to students' level of language proficiency, for example. Do teachers use more L1 in beginning levels compared to intermediate or advanced levels?

What was evident concerning this study was that the use of L1 has a facilitating and natural role within the learning process. It also provides a certain level of safe space for understanding the learning process and empathizing with students' learning needs. However, one must realize that the use of L1 is not a simple formula but a complex decision-making process. Both teachers and students use L1 while in the classroom. Some students like using L1 and others do not. Those that did not like to use L1 had their reasons for only wanting to use the target language. These are some of the complexities.

There is not a perfectly attainable balance between when and how to use L1; rather, there is a dynamic decision-making process that occurs within the two groups of participants: the teachers and the students. Participants are continually weighing their individual beliefs and learning objectives against those of the other participants and with the curriculum, and the result is a decision to use or not to use L1 and, if so, to what extent. What is evident upon completing this research is that L1 does in fact play an important role in the teaching-learning processes in foreign language contexts such as this one.

* This article reports on a study financed by the Division of Social Sciences and Humanities of the Universidad de Guanajuato.

References

Al-Hinai, M. K. (2006). The use of the L1 in the elementary English language classroom. In S. Borg (Ed.), Classroom research in English language teaching in Oman. Muscat: Ministry of Education, Sultanate of Oman. Retrieved from: http://www.moe.gov.om/Portal/sitebuilder/sites/EPS/English/MOE/baproject/Ch2.pdf

Atkinson, D. (1987). The mother tongue in the classroom: A neglected resource? ELT Journal, 41(4), 241-247.

Auerbach, E. R. (1993). Reexamining English only in the ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 27(1), 9-32.

Blaxter, L, Hughes, C., & Tight, M. (2006). How to research. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

Brooks-Lewis, K. A. (2009). Adult learners' perceptions of the incorporation of their L1 in foreign language teaching and learning. Applied Linguistics, 30(2), 216-235.

Carless, D. (2008). Student use of the mother tongue in the task-based classroom. ELT Journal, 62(4), 331-338.

Cook, V. (2001). Using the first language in the classroom. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 57(3), 402-423.

Denzin, N. K. (1994). The art and politics of interpretation. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 500-515). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2000). Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Edstrom, A. (2006). L1 use in the L2 classroom: One teacher's self-evaluation. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 63(2), 275-292.

Fairclough, N. (1989). Language and power. Harlow: Longman.

Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Fournier, C. (1990). Open for business. Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Gower, R., & Walters, S. (1983). A teaching practice handbook. London: Heinemann.

Harbord, J. (1992). The use of the mother tongue in the classroom. ELT Journal, 46(4), 350-355.

Hedge, T., & Whitney, T. (1996). Power, Pedagogy and Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Howarth, D. (2000). Discourse. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Lado, R. (1990). Lado English series three. New Jersey, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Lewis, M. (1993). The lexical approach. The state of ELT and a way forward. London: Language Teaching Publications.

Lewis, M., & Hill, J. (1993). Source book for teaching English as a foreign language. London: Macmillan Heinemann.

Lindsay, C. & Knight, P. (2006). Learning and teaching English: A course for teachers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Martin, J. M. (2001). Nuevas tendencias en el uso de la L1. ELIA, 2, 159-169.

Mills, S. (1997). Discourse. London: Routledge.

Richards, K. (2003). Qualitative inquiry in TESOL. New York, NY: Palgrave.

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, S. (1986). Approaches and methods in language teaching: A description and analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rolin-Ianziti, J., & Varshney, R. (2008). Students' views regarding the use of the first language: an exploratory study in a tertiary context maximizing target language use. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 65(2), 249-273.

Scheweers, W. (1999). Using L1 in the L2 classroom. English Teaching Forum, 27(2), 6-13.

Storch, N., & Wigglesworth, G. (2009). Is there a role for the use of the L1 in an L2 setting? TESOL Quarterly, 32(4), 760-770.

Stern, H. H. (1991). Fundamental concepts of language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Swain, M., & Lapkin, S. (2000). Task-based second language learning: The uses of the first language. Language Teaching Research, 4(3), 251-274.

About the Authors

Irasema Mora Pablo holds an MA in Applied Linguistics from the Universidad de las Américas-Puebla and is currently a PhD student in the Applied Linguistics program at University of Kent, England. She works in the Language Department, University of Guanajuato. Her areas of interest are bilingualism, second language acquisition and sociolinguistics.

M. Martha Lengeling, former Director of the Language Department, has worked at the University of Guanajuato for 29 years and holds an MA in TESOL from West Virginia University and a PhD in Language Studies from the University of Kent. Her areas of research are teacher training and teacher identity formation.

Buenaventura Rubio Zenil works at University of Guanajuato. She holds an MA in Psychology of the Language from the University in Poitiers, France, and is currently pursuing her doctoral studies in Language Sciences at the University of Paris 1- Sorbonne Nouvelle. Her research areas are language learning autonomy and conversation analysis.

Troy Crawford holds a BA from Southern Oregon University, an MBA from University of Guanajuato, an MA TESOL from the University of London, and a PhD from the University of Kent, Canterbury. He has worked in ESL for 28 years in Mexico focusing his research on second language writing. He has presented his work in France, England, the United States and Mexico.

Douglas Goodwin holds a PhD in Language Studies from the University of Kent, and an MEd from the University of Manchester. He has over 18 years of ELT experience and his research interests include film in ELT, intercultural communication, and educational technology. He is currently the Universidad de Guanajuato Language Department Chair.

Acknowledgements

Gratitude goes to the teachers and students who participated in this research and the financial support received to carry out this project. Without both, we would not be able to understand the complexities of L1 use within the foreign language classroom. This study was financed by the Division of Social Sciences and Humanities of the University of Guanajuato and carried out with members of a research area of Applied Linguistics of the same university.

Appendix A: Questions Used in the Semi-Structured Interview for Teachers

- What do you think of the use of Spanish in your foreign language class?

- Why (or why not) do you use Spanish in your classes? Explain.

- If you use Spanish, when do you use it? Under what circumstances? Are there any particular activities or moments in which you consider the use of Spanish necessary?

- Do you think there are any advantages or disadvantages when using Spanish for teaching or learning?

- What do you think of the use of Spanish in your foreign language class?

___________________________________________________________________________________________ - Do you like it when your teacher uses Spanish? Why or why not?

___________________________________________________________________________________________ - How do you feel when your teacher uses Spanish in the class?

___________________________________________________________________________________________ - How much do you use Spanish in the classroom without the teacher promoting its use? When do you use it? Do you have a particular purpose?

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.