A Concrete Psychological Investigation of Ifá Divination

Una Investigación Psicológica Concreta de la Adivinación de Ifá

Uma Pesquisa Psicológica Concreta da Adivinhação de Ifá

MARTIN J. PACKER

Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia

and Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, United States

SILVIA TIBADUIZA SIERRA

Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Martin J. Packer, e-mail: mpacker@uniandes.edu.co.

Department of Psychology, Universidad de los Andes.

SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH ARTICLE

RECEIVED: 2 FEBRUARY 2012 - ACCEPTED: 20 AUGUST 2012

Abstract

Divination -the consultation of an oracle in order to determine a course for future action- has long been considered a practice characteristic of "primitive mentality." We describe research with the babalawo of Santería, who are expert in the divinatory system of Ifá. Our first goal is to offer an example of what Vygotsky called "concrete psychology": the study of particular systems of psychological functions in the concrete circumstances of specific professional complexes. Our second goal is to explore the character of divination as psychological and social process, given the somewhat negative views of divination expressed by many social scientists, including Lévy-Bruhl and Vygotsky himself. Analysis of a recorded consultation identified features characteristic of institutional discourse. We argue that the institutional facts of divination may constitute an unfamiliar ontology, but the epistemology -the

appeal to logic and to empirical evidence- is a familiar one.Keywords: cultural psychology, higher psychological functions, Lev Vygotsky, divination, concrete psychology, argumentation.

Resumen

La adivinación -consulta de un oráculo con el fin de determinar acciones futuras- se ha considerado una práctica característica de la "mentalidad primitiva". A continuación se presenta una investigación con los babalawos de la santería: los expertos en el sistema de adivinación de Ifá. El primer objetivo fue dar un ejemplo de lo que Vygotsky llamó "psicología concreta": el estudio de sistemas de funciones psicológicas particulares dentro de las circunstancias concretas de complejos profesionales específicos. El segundo objetivo fue explorar la adivinación como proceso psicológico y social, examinando las nociones, un tanto negativas, que han expresado algunos científicos sociales sobre este concepto, incluyendo a Lévy-Bruhl y al mismo Vygotsky. Algunos rasgos característicos del discurso institucional se identificaron a través del análisis de registros de audio de consultas al oráculo por parte de los autores. En este trabajo se argumentó que los aspectos institucionales de la adivinación pueden constituir una ontología poco común, pero una epistemología familiar.

Palabras clave: psicología cultural, funciones psicológicas superiores, Lev Vygotsky, adivinación, psicología concreta, argumentación.

Resumo

A adivinhação -consulta de um oráculo com o fim de determinar ações futuras- tem sido considerada uma prática característica da "mentalidade primitiva". A continuação, apresenta-se uma pesquisa com os babalawos da santería: os especialistas no sistema de adivinhação de Ifá. O primeiro objetivo foi dar um exemplo do que Vygotsky chamou "psicologia concreta": o estudo de sistemas de funções psicológicas particulares dentro das circunstâncias concretas de complexos profissionais específicos. O segundo objetivo foi explorar a adivinhação como processo psicológico e social, examinando as noções, um tanto negativas, que têm expressado alguns científicos sociais sobre esse conceito, incluindo Lévy-Bruhl e o próprio Vygotsky. Alguns traços característicos do discurso institucional se identificaram por meio da análise de registros de áudio de consultas ao oráculo por parte dos autores. Neste trabalho, argumentou-se que os aspectos institucionais da adivinhação podem constituir uma ontologia pouco comum, mas uma epistemologia familiar.

Palavras-chave: psicologia cultural, funções psicológicas superiores, Lev Vygotsky, adivinhação, psicologia concreta, argumentação.

"My history of cultural development is an abstract treatment of concrete psychology." (Vygotsky, 1986, p. 68)

THE WRITING of Lev Vygotsky has become increasing influential in many countries around the world. It is now well-known that Vygotsky proposed a revolutionary psychology that would overcome dualism, in the study of consciousness as a material process. He viewed consciousness as our relationship to the world, and argued that the various psychological functions work together as a dynamic system. He insisted that this system ought to be studied as a whole, rather than divided into separate components as is typically done in psychological research. Psychology should study the "real personality" as a unity, rather than traits or characteristics, a unity always located in what Vygotsky called "the social situation of development."

What is less well-known is that in his notebooks, unpublished until recently, Vygotsky anticipated a "concrete psychology" which would move beyond the abstract conceptualization of human psychological functioning to undertake detailed investigations of specific ways of being human (Vygotsky, 1986). He complained, or confessed, to himself that his psychology remained abstract in its treatment. One might say, though he didn't use these words himself, that his psychology was still at a phase of development where it simply described the generic person. He wrote that "My history of cultural development is an abstract treatment of concrete psychology" (Vygotsky, 1986, p. 68). In a concrete psychology, in contrast, the holistic model of personality would be related to the real life of specific persons, or specific kinds of person, in specific circumstances. Vygotsky proposed that considered concretely the higher psychological functions can continually "change their role," so that "there is no permanent hierarchy" among them but rather "a sphere of possible roles" that each function can play, varying in "different spheres of social life." The task, then, would be to study how the professional complex of a Moscow worker is structured, for example. Vygotsky (1986) proposed that such investigation would explore "the different spheres of behavior (professional complex, etc.), the structure and the hierarchy of functions where they relate to and clash with one another" (p. 70). Evidently this would be the study of specific individuals in their particular practices, but in his short notes Vygotsky merely sketched the outline of a concrete psychology. It is necessary to fill in many of the details.

In this article we will describe our own efforts to study personality in this sense of a fluid configuration of higher psychological functions in a social environment. We will describe our empirical exploration of the "living, specific psychology" (Bozhovich, 2009, p. 37) of a particular professional complex -that of a babalawo, the priest of Ifá divination in the syncretic religion of Santería. We have two goals. The first is to clarify the character of a concrete psychology, and to contribute to the various lines of work that in recent years have taken psychology into the "wild" (cf. Cole, 1995; Hutchins, 1995; Lave, 1991). The second is to explore the nature of the verbal reasoning that occurs in divination, given the somewhat negative views expressed by Vygotsky himself on this relationship, and the equally negative views of other social scientists. We shall describe the practice of divination in the context of a session of consultation. Our analysis of this consultation demonstrates features characteristic of institutional discourse, frequent reported speech, and "reading" of the client, with assertions and questions that presume prior knowledge. Much of the interaction is oriented to predictions, prophesies, and the giving of advice, and the latter takes the form of what we argue is reasoned argument, with clearly stated claims, warrants and grounding.

We have argued elsewhere that there are parallels between Vygotsky's project and Foucault's notion of a "historical ontology of ourselves" (Foucault, 1993; Packer, 2008), and it is relevant to sketch these parallels briefly. For both Vygotsky and Foucault, thought is not individual mental representation, because human cognition is grounded in embodied practical activity, historically constituted and socially distributed. For both, ontogenesis involves ontological change: the person is a product of the social, and (in Foucault's terms) power is folded to form the self or (in Vygotsky's terms) self-mastery is necessary for the personality to become a system of higher psychological functions. Both conducted studies of "constitution": the relation of mutual formation between person and form of life (Packer, 2010). We can see these parallels in operation in the overlaps between research on occupational personalities such as waitress (Rose, 2001), bartender (Beach, 1993), and factory worker (Scribner, 1985) within the framework of cultural psychology, and studies of, for example, Indian ascetics the Jain (Laidlaw, 2005) within a Foucauldian framework. We shall argue that Ifá divination is an occasion of constitution, though of the client as much as the babalawo.

Divination and "Primitive Mentality"

Divination has long been viewed as a key component of primitive mentality. Lévy-Bruhl's analysis of La Mentalité Primitive (1922/1923) led him to the conclusion that:

"The mind of the 'primitive' has hardly any room for such questions as 'how' or 'why?'" "Myths, funeral rites, agrarian practices, and the exercise of magic do not appear to originate in the desire for a rational explanation; they are the primitives' response to collective needs and sentiments which are profound and mighty and of compulsion" (Levy-Bruhl, 1910/1925, p. 25).

In Lévy-Bruhl's account, one of the "most important components of the primitive's mental experience" (1910/1926, p. 122), and one of the central aspects of mythical mentality, was the use of dreams for divination. He described how for "the South African races" dreams assisted in contact with the dead. He recounted not one but three dreams of Kaffirs1. Here is the second, the most straightforward of the three:

A man dreams that an attempt has been made to take his life by one whom he has always regarded as his true friend. On awakening he says: "This is strange; a man who never stoops to meanness wishes to destroy me. I cannot understand it, but it must be true, for 'dreams never lie.'" Although the suspected friend protests his innocence, he immediately cuts his acquaintance (p. 108)

Lévy-Bruhl explained that this unmasking of wizards and revealing of danger stemmed from the contact which dreams provide with the dead: "The dream is a revelation coming from the unseen world" (p. 109). He went on to describe how when dreams and omens do not appear spontaneously, the "primitive" will employ more active forms of divination. "To calculate the chances carefully and systematically, and try to think out what will happen, and make plans accordingly, is hardly the way in which primitive mentality proceeds" (p. 159). Instead, divination is their tool of choice.

After concluding that primitive people have no concepts, no true ideas, no sense of self or society, no definite conception of reality, and fail to recognize the basic laws of logic, Lévy-Bruhl did at least acknowledge that difficulties face any researcher trying to grasp another way of living in the world:

In spite of the most careful effort, our thought cannot assimilate them [the paths of primitive thought] with what it knows as its "ordinary" objects. It therefore despoils them of what there is in them that is elementally concrete, emotional, and vital. This it is which renders so difficult, and so frequently uncertain, the comprehension of institutions wherein is expressed the mentality, mystic rather than logical, or primitive people (p. 447).

Lévy-Bruhl genuinely seemed to want to explore primitive mentality objectively, without presumptions, especially avoiding the presumption that such people ought to think the way Westerners do. Primitive mentality was not to be considered an early form of Occidental, reasonable, mentality; it was fundamentally distinct, essentially other. He concluded (1910/1925) that such people did not lack the capacity to think abstractly and logically, they simply lacked the custom and habit to do so.

Much anthropological research since Lévy-Bruhl's time has continued to presume that divination is inherently irrational. For example, in a much-cited article, Moore argued that the function of divination is merely to introduce what is essentially a randomization mechanism to disrupt customary practices that have become ineffective (as a result of failure-due-to-success effects, such as hunting out an area, or hunting to the point that the remaining animals become wary and hard to catch). This is to say that divination functions precisely because it cannot predict the future (Moore, 1957).

Similarly, Evans-Pritchard (1937) famously asserted that Azande divination involves a self-limiting system for explaining away its failures. Zeitlyn (1990) drew a parallel between the questioning in a session of divination and an early experiment by Garfinkel in which the researcher responded to a participant's questions by throwing a dice. Garfinkel's conclusion was that people can always find meaning in random events, and Zeitlyn argued that this is precisely what happens in divination.

Anthropologists have often complained that the diviner fails to "go behind" his beliefs and recognize them as symbols of psychological or social forces: "He treats as self-evident truths what social anthropologists and depth psychologists would try to reduce to rational terms" (Turner, 1961, p. 231). Divination is assumed to symbolize some deeper rationality, which it is the job of the anthropologist to uncover. The diviner confuses appearance and reality; the anthropologist can, and must, set these straight.

However, in making such claims it would appear that the anthropologist is just as guilty as the diviner of failing to permit any falsification of their own worldview. If the diviner does not allow any test of the existence of spirits, neither does the anthropologist. The former simply accepts that they exist; the latter simply accepts that they do not. The diviner interprets the signs of the oracle as evidence for a deeper, hidden organization. The anthropologist does the same! Both are guilty of what Garfinkel has called the "documentary method of interpretation," where an everyday phenomenon is taken to document some kind of hidden structure, for which the phenomenon is taken to be evidence, and the structure is then appealed to as an "explanation" of the phenomenon. Instead, Garfinkel (1996) recommends, we should be looking at the ways the organization of everyday phenomena is achieved. What is needed is a method of investigation which does not try to replace the local, vernacular, indigenous ontology with either a Western or an academic conception of social reality.

The crux of the matter is that the diviners' claims are incommensurate with those of anthropologists. The anthropological response to this problem often consists of reducing the diviners' statements to phenomena that the diviners make no pretension to address. This strategy has the advantage of neutralizing the diviners' truth-claims whilst making them meaningful in terms of scientific criteria. The posited underlying "essence" provides the vocabulary for translating one set of representations into another in accordance with classic epistemology... To justify this, anthropologists proclaim diviners, clients, and themselves as "imputing meanings" in order to make sense of behaviour that "is assumed to be connected to a hidden state of affairs"... Crucially, these different actors do not disclose and relate to the same underlying reality (Myhre, 2006, p. 314).

In the analysis we report here, we have tried to avoid replacing the local ontology of the consultation with our own conception of reality. However, the fact that a babalawo can live and practice divination successfully in the heart of a modern city such as Bogotá suggests that incommensurability is not the correct way to characterize the relationship between Santería and the reality of modern anthropology. We shall return to this point later.

Vygotsky on Divination

Rather surprisingly, in his notes on concrete psychology Vygotsky also wrote of the Kaffir. Writing just a few years after the publication of Lévy-Bruhl's work, he discussed the case of a judge who is also a husband as an example of how psychological "functions change the hierarchy in different spheres of social life" (Vygotsky, 1986, p. 69) but then he also wrote of the psychological functions of the Kaffir, which, he argued, were not examples of "primitive" functioning:

In him (the leader of the Kaffirs) sleep acquired a regulatory junction through the social significance of dreams (unexplainable difficulty, etc., the beginnings of magic, cause and effect, animism, etc.): what he sees in his dreams, he will do. This is a reaction of a person, and not a primitive reaction (p. 65).

The divinatory dreaming of a Kaffir, then, far from being an illustration of the limitations of primitive mentality, as Lévy-Bruhl had seen it, was for Vygotsky an example of the "higher psychological functions," because the Kaffir was dreaming deliberately, with control of his own abilities. The Kaffir's dream was, then, an illustration of a true personality.

However, Vygotsky (1997) considered the Kaffir to still be primitive in another sense. He argued that although divination -tossing bones, for example- might be "the beginning of conscious self-control of one's own actions," (pp. 46-47) it is only the beginning. Although "once an exceptionally important and significant moment in the system of behavior" (p. 47) it is, and was, nonetheless "rudimentary" (p. 47). He wrote:

[I]t is a fact that the man who first cast lots took an important and decisive step towards the development of cultured behavior. This does not contradict the fact that such an operation kills any serious attempt to use reflection or experience in real life: Why bother to think and learn, when you can simply see what you dream, or roll the dice? Such is the fate of all forms of magical "BodyInglsTEXTO">Vygotsky's position here resembles that of Moore, who, as we noted earlier, argued that divination works precisely because it cannot predict the future. For Vygotsky, the Kaffir was a personality, employing higher psychological functions, but his divination through dreaming was still a long way from modern reasoning. It was merely a way of deciding what to do when there is no obvious basis for choice, a way of deciding which precluded the use of reflection or experience.

The question we shall focus on in our analysis, then, is whether divination necessarily "kills any serious attempt to use reflection or experience in real life" and whether it indeed stands opposed to any effort to "try to think out what will happen, and make plans accordingly." Is "the mystical" inevitably opposed to "the logical"? Is divination just "magical behavior," perhaps an "embryo" of the historical development of thinking but also an "obstacle" to such development? Or is it the case that, as Scribner (1977) noted, "We know very little about the social conditions which give rise to the logical genre, how cultures define the occasions for its use, [or] through what experiences individuals acquire its schema" (p. 499).

Method

We have suggested that Vygotsky's concrete psychology, like Foucault's ontology of ourselves, calls for an investigation of constitution, and we have proposed elsewhere that such an investigation requires that the traditional tools of ethnographic fieldwork, interviews, and the detailed study of practical activity, are appropriately reforged (for details, cf. Packer, 2010, 2011). Our study of the babalawo involved all three of these tools (Tibaduiza, 2010a, 2010b). The investigation was conducted by the second author, supervised by the first author, in the city of Bogotá over a period of six months. Ethnographic fieldwork was carried out, primarily in the houses of three babalawo, where they saw their clients. These houses were located in three different neighborhoods. A Cajon al Muerto (a spiritual ceremony to honor the dead) which took place in one of the houses was also attended. A consultation was arranged with the first babalawo, then introductory interviews were scheduled with the others. A total of five interviews were conducted with the babalawo with whom the consultation was conducted, and two interviews with each of the others. All interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed, as was the consultation. Interviews were also conducted with three clients, two male, one female, in their places of work. The interviews focused on people's motives for seeking a consultation.

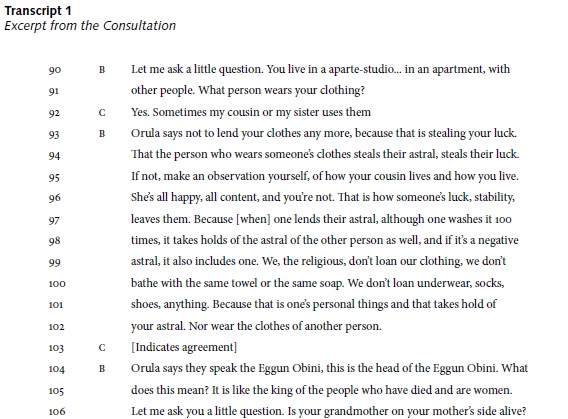

The following section describes what we learned about Santería and Ifá divination from the interviews, fieldwork, and background reading. The subsequent section presents an analysis of the details of the consultation session. Our analytic approach here is that of conversation analysis (Goodwin & Heritage, 1990; Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson, 1974; Schegloff, 1995). Conversation analysis focuses on the pragmatics of conversation, and the practical and interactive construction of conversational interchanges. It pays attention not so much to what people say as to what they do by saying. It also attends to the way participants in an interaction display their understanding of what they and others are doing, with sensitivity to the concrete setting of the interaction. We selected for detailed analysis one short excerpt (Transcript 1) from the consultation, an excerpt that deals with a particularly mundane matter, in part to avoid disclosing personal details, for much of the consultation dealt with very personal considerations. The features we will identify in this excerpt occurred throughout the consultation, however.

Santería

Santería is an Afro-Cuban religion whose formation began in the 16th century with the transportation of Yoruba slaves to Cuba. These people brought with them a set of beliefs based on the worship of the orishas (divinities in the Regla de Ocha, a Yoruba religion) (Clarke, 1939). The resemblance -at least superficially- of this tradition to the Catholicism which had also arrived in the Americas facilitated a syncretic relationship between these two religions, and this was reinforced by the restrictions that Catholic masters placed in their slaves (Bastide, 1969). Over time, a correspondence, part resignification and part concealment, became established between Yoruba orishas and Catholic saints (Wedel, 2004). As a result, in Santería today the terms santo and orisha are used interchangeably. However, key differences remain, for example in rituals and in the conceptions of relationship with ancestors, including the importance attributed to direct and two-way communication with the spiritual dimension, established in practices of trance-possession.

Santería practitioners believe in the existence of a supreme god along with a large number of subordinate deities to whom people can go to solve their problems and ask for help (Barnet, 2000; Wedel, 2004). This supreme divinity, which founded and governs the entire universe, consists of a trinity of Oloddumare, Olorun and Olofi. This has been compared to the Catholic trinity, however different interpretations exist. One of these is that Olofi is the supreme being, placed above all other creatures of creation, while Oloddumare is the sacred place where this divinity dwells, and where the spirits go when they have abandoned an earthly body. Olorun, the third aspect of the trinity, is the sun.

The orishas are divinities who overlook mankind; they once lived in the world and experienced the trials of daily life. Sacrifices are not made directly to the supreme being; it is through ceremonies, offerings and rituals to the orishas that humans discover what we need, and are taught how to live healthy, spiritual lives.

In Santería, communication with the dead and the orishas is essential. Believers establish relations of guidance and reciprocity with them, and seek to know their wishes, advice, and warnings. Consequently, an important form of interaction between the santos and practitioners of Santería is the consultation of oracles. There are three systems of divination and interpretation: obi, diloggún and Ifá. Our research focused on the oracle of Ifá, which is greatly respected and regarded by practitioners of Santería and by connoisseurs of the Yoruba tradition as the most comprehensive of the three, due to its great literary and symbolic content. Ifá is consultation with Orula, one of the most important orishas.

Ifá divination is based on a corpus of poetic narratives, comprised of many oddun, sets of proverbs, poems and stories that are the basis for interpreting the situation of the person who attends a consultation (García, 2000). These verses summarize thousands of years of accumulated wisdom, and contain predictions and mundane and spiritual prescriptions (De Souza, 2007). The Ifá divination system was in 2008 inscribed by UNESCO on its list of "Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity" (UNESCO, 2008).

The experts who make use of this system of divination and interpretation are the babalawos. "The word babalawo in its etymological sense is derived from the Yoruba words: baba -father, la -have, awo -secrets, or the father who has the secrets" (Betancourt, 2007, p. 2). The babalawos play a highly important role in Santería, since they embody the collective spirit of the community and are guardians of the secrets of the universe (Betancourt, 2007). The messages revealed through divination are the exclusive communication between Orula and the earthly world. It was Olofi, Oloddumare and Olorun who created the earth, but Orula is the only orisha who permits direct communication between this earthly world and these figures of creation. As a result, he has, or is, the knowledge and intelligence that govern human beings and triumph over all evil. He is the divine and wise figure who knows the future of everyone and everything. It is Orula who is consulted through Ifá divination, and the babalawos are the managers of this connection (Wedel, 2004).

As a consequence, babalawos have a privileged place in the religious hierarchy. A babalawo will be consulted in cases of ill-health, impotence or sterility, and also before a child is born and again shortly after the birth, to ascertain the child's guardian spirit. Traditionally, when the newborn is a boy, it is the babalawo who determines whether circumcision should be carried out immediately or at the age of eighteen, as is traditional. The babalawo also officiates "when a house is to be built, a field planted, a journey begun, a project undertaken, a marriage considered" (Wyllie, 1970, p. 53). Today, the motives for a consultation are more likely to be money troubles, relationship problems, and so on.

Learning to perform Ifá divination requires a long process of preparation and learning (De Souza, 2007). This begins once the individual has been consecrated as a babalawo. Unlike the education that takes place in schools and universities, in Santería the title is awarded first, and only then does the process of learning begin (Lorenzo, personal communication, March 20, 2010). The babalawo is guided by their padrino (godfather), and learns in the company of other ahijados (godchildren). His path (all babalawos are male) is also guided by the book of Ifá, the secret text that contains knowledge about the universe, which he must commit to memory. Through participating in the various ceremonies and consultations organized by the padrinos together with other ahijados, using the book of Ifá, the expertize of a babalawo grows.

A babalawo will draw on this expertize in the registro, the activity of consulting the Ifá system of divination. During consultation with a client, the babalawo has the task of obtaining an odu, the sign which provides the basis for appropriate advice and instruction, by throwing the ékuele, the tool of divination, which is made of colored seeds threaded on a chain. The patterns formed when the chain is thrown define sixteen different signs, so that two throws generate 256 combinations. This system of divination has attracted scholarly attention in large part due to its binary organization, which reflects a cosmovision based on a metaphysical dualism. Each sign has its own teaching, recorded in the sacred text. The babalawo must apply this teaching to the client's specific case, taking into account the particularities of their situation. He offers the client a recital of the relevant portions of the text, including instructions for sacrifice, poetic incantations, and illustrative narratives.

All this suggests that a babalawo is a person of skill and responsibility, one who has mastered a body of traditional learning and also the practical skills of consultation and divination. Consequently, it is of great interest to explore the psychological capabilities that such a person has developed and acquired in the course of their professional training, and this is what we set out to do. Of central interest to us was the particular and specific constellations of psychological capabilities that are needed to successfully use the system of Ifá divination.

The Practice of Divination

"[T]here is a paucity of case-studies of Ifa in use" (Zeitlyn, 2001, p. 238)

Our focus in this paper is on the practice of divination, that is, the consultation itself: "The way in which adepts make a bridge between their own knowledge or intuitions about the client and the meanings of the [oracle]" (Zeitlyn, 2001, p. 230). This, if anywhere, is where the babalawo makes evident his skills and expertize. It is also where he makes evident the good life of Ifá, as he gives advice to the client.

The day of the consultation, Lorenzo2 was waiting in the area of Bogotá known as Galerías. Lorenzo was 27 years old, born in Cuba, where he was consecrated as a babalawo seven years earlier. He had studied at college, though his education was interrupted when he moved to Colombia four years previously. He obtained his income from his work as a babalawo, and he was now the padrino of several members of the Santería community in Bogotá. After introductions and an explanation of the research, Lorenzo led the way to a small room in his house, used exclusively for consultations, where his instruments were laid out, among small altars to the orishas. There he sat at a desk and, making use of the instruments, began a series of prayers or moyubas in Yoruba to start receiving messages or oddun. He permitted recording only of that part of the consulation which consisted of the delivery of messages from the orishas, his interpretation of their relevance, and occasional questions that helped him in this objective. It is this phase of the consultation on which we base our observations in this paper.

Analysis and Results

"The relationship of client and diviner makes dialogue central to any adequate account of divination." (Zeitlyn, 2001, p. 237).

We have selected for detailed analysis here one short excerpt from the session of divination (Transcript 1), which lasted a total of 90 minutes. Our discussion of this excerpt is organized in terms of a series of discursive features which are evident in it. We will describe the character of the turn organization, the presence and pragmatics of reported speech, the way the babalawo (B) "reads" his client (C), and the orientation of their interaction towards the offering and receipt of advice. We then discuss in some detail the organization of argumentation behind the specific advice that is offered in this excerpt.

Long Turns, Short Replies

The first of the features of the interaction in this excerpt that becomes evident is the character of its turn-taking organization (Sacks et al., 1974). The organization of turns in this exchange, as in the consultation as a whole, is such that the client's moves are "preallocated": they take only a few forms, mainly responses to questions, and they are generally short. One might suppose, then, that the babalawo's turns are largely devoted to the asking of questions. But in fact, and in contrast to those of his client, his turns are much less restricted. He does ask questions, certainly, but he also gives advice, tells stories, draws inferences, makes assertions. His turns are much longer than the client's, and they are much less restricted than those of, say, a lawyer questioning a witness in a courtroom (where statements are not permitted).

In these respects the interaction resembles others that are characteristic of "institutional" discourse (such as news interviews, courtrooms, classrooms, doctors' offices) in which one party questions the other, rather than "ordinary talk." Institutional talk will "embody orientations which are specifically institutional or which are, at the least, responsive to constraints which are institutional in character or origin" (Heritage, 1998, p. 6). Such talk generally has the following characteristics: the interaction involves goals tied to institution-relevant identities; it involves special constraints on what is an allowable contribution; it will involve special inferences that are particular to specific contexts (Heritage, 2005).

We see each of these characteristics in the consultation and, indeed, in this excerpt. We have already mentioned the differential constraints on the moves made by the two participants, babalawo and client, which are clearly visible in the different lengths of the turns, and the question-answer alternation. Later we will focus in detail on the "special inferences" that are being made. That leaves the institution-relevant identities: in terms of these we can see the babalawo characterizing his own identity -"we, the religious"- in order to articulate the goal of maintaining ones "astral" in the face of attempts by others to "take hold" of it or "steal" it. He also characterizes his interlocutor as recipient of advice. The interaction as a whole can be seen as one in which the goal of the babalawo is to diagnose and offer advice, while that of the client is to obtain guidance.

Several domains of interactional phenomena are considered relevant to institutional interaction (Drew & Heritage, 1992; Heritage, 1998): turn-taking organization, overall structural organization of the interaction, sequence organization, turn design, lexical choice, and epistemological and other forms of asymmetry. In addition to the strikingly asymmetric turn-taking, topic control in the consultation is managed entirely by the babalawo. Turn design is largely in his hands; it is he who closes the interaction, for example. It is he who shifts the topic from reading the signs, to telling the fortune, to determining the offerings to be made. The terminology is specific to Ifá. And the epistemology is indeed asymmetrical: it is he who knows. Below we explore in more detail how he works to display his knowledge.

Reported Speech

One might assume that the divination is an interaction between two participants, the babalawo and the client, but in actuality there is a three-way conversation. It is indeed the case that "In examining the process of divination, we must consider the multivalent and hence multivocal relationship between divination technique and diviner as well as between diviner and client" (Zeitlyn, 2001, p. 237). This three-way character is evident in the frequent appearance of reported speech. "Reported speech is speech within speech, utterances within utterances, and at the same time also speech about speech, utterances about utterances" (Voloshinov, 1929, p. 115). We observe many utterances in which the babalawo speaks for, or on behalf of, another person, generally one of the oddun. For example, in this excerpt he says, "Orula says not to lend your clothes any more."

The use of reported speech conveys that the babalawo is a relayer of information, not its source. What we generally see, and what we see here, is not quoted speech, but speech that is glossed. The babalawo does not say "Orula said, 'Call your mother'," but "Orule said that you should call your mother." The distinction may seem small, but it is significant. It is what Voloshinov (1929) refers to as a transposition from "the sphere of speech construction to the thematic level" (p. 116). The glossed speech is still detectable as a "foreign" element, as a contribution from a third party, which the babalawo relays. At the same time, in glossing rather than quoting, the babalawo displays himself as actively reporting the source's speech or message.

Reported speech is treated by both speaker and recipient as belonging to a third party. This treatment lends weight to the supposition that the third party actually exists, albeit in a distinct existential modality (fictional, or dead, or transcendental). The reporting of the oddun, and mediatedly of Orula, also demonstrably takes into account the client as third-person recipient. The report is evidently designed for her reception. In the excerpt, what Orula is reported as saying is put in the second person: "not to lend your clothes," not "one should not lend one's clothes."

A distinction has been drawn between two attitudes to the boundary markers between authorial and reported speech, and between two corresponding analytical strategies (Clark & Holquist, 1984). The first attitude is "linear." It attempts to maintain the integrity and authenticity of the reported speech, and places clear, hard-edged boundaries between it and the authorial speech. (This is what we do when we quote from the transcript.) The strategy here is that of emphasizing reference. Meaning is dissected into constituent, ideational referential units, and emphasis is placed on the meaning of the utterance, not matters such as its style.

The second attitude is "pictorial." This approach infiltrates the reported speech with editorial retort and commentary. It dissolves and obliterates the boundaries between the two. The strategy here is that of emphasizing texture; this approach particularizes the reported words, but shades them with the author's attitude. What we see in the case of the babalawo's reported speech is this second strategy. As a consequence, in occasions of reported speech the babalawo generally displays his orientation to the message he is reporting, and his orientation to the oracle.

There is also another kind of reported speech, though it does not occur in the excerpt we have selected here. This is when the babalawo reports -or appears to report- speech by the other participant, the client. For example, at one point he says, "This Gypsy comes in the spiritual cord. What is this? This is part of a ring of astral protection." The "What is this?" serves here as a turn taken on behalf of the client. One consequence is that although, as described above, the client's turns are largely preallocated as replies to questions, with this device the babalawo effectively raises questions on the client's behalf. In doing so, he voices her unspoken doubts and uncertainties. The effect of this "ventriloquism" is to imply, to create the impression, that he can anticipate her queries, her confusion or skepticism -or, to put it another way, that he can read her mind. This kind of reported speech displays the babalawo's reception of his client's concerns. He displays his sensitivity to issues that are unspoken. Indirect speech is "analytical transmission of someone's speech"- "an analysis simultaneous with and inseparable from transmission" (Voloshinov, 1929, p. 128). What was form, the emotive-affective features, must become content.

We see here that divination is not only about anticipating the future, it is also about intuiting, understanding, the past and the present. We witness in this characteristic of the discourse the display to the client of a preternatural -uncommon, even unaccountable- understanding of her thoughts and feelings. This is also evident in the next characteristic feature of the interaction.

Reading the Client

We have noted that many of the client's turns are responses to questions, and it is striking that many of these questions are ones that would more usually follow a presequence. For example, the question "What person wears your clothing?" might be expected to follow a presequence such as "Does someone wear your clothing?" "Yes." In other words, such questions presume a prior acquisition of information that has not in fact taken place. The babalawo's question presumes that someone has indeed been wearing the client's clothes, and proceeds from there to inquire as to the identity of that person. Such questions without presequences appear repeatedly during the consultation.

In this excerpt we also see assertions which appear to rest upon prior knowledge of the client which has not in fact been provided. The babalawo begins with "You live in a aparte-studio... in an apartment, with other people." The consultation was our first contact with Lorenzo, and he had been told nothing of our living circumstances. Similarly, when he says "She's all happy, all content..." this is also something that had not been talked about.

There are at least two ways of interpreting such questions and assertions that presuppose prior interactional work that has not in fact been done. One is to see them as a strategy of "cold reading" the client. "'Cold reading' is a procedure by which a 'reader' is able to persuade a client, whom he has never before met, that he knows all about the client's personality and problems" (Hyman, 1977, p. 2). Cold reading can take the form of offering highly general assertions that can fit any individual, or of asking questions which appear to presume prior knowledge. On the face of it this is a risky strategy, but if it pays off it provides handsome benefits, because the inference would be that the babalawo has knowledge that only the spiritually-informed could have.

The second way of interpreting these assertions and questions is that the babalawo is reading the client in a different way: reading her demeanor, her attitude, attending carefully to such things as the state of her clothing, her facial expressions, the color of her skin, and so on. This would be to attribute to him a honed intuitive ability to attend to what is not explicitly spoken, and so is not evident in a transcript of the consultation. Certainly, in either case, the effect of such questions and assertions is to display knowledge of the client that has a somewhat mysterious quality; an intuitive understanding of the client's past and present circumstances and concerns.

Oriented towards Advice

Much of the babalawo's talk takes the form of advice, recommendations, and obligations for the future conduct of the client. What she has to do, or ought to do, includes "go to the church and make mass for you deceased relatives," "look after your mother, by phone," "arrange a sacrifice," "pray," "wear your hair loose," and so on. In the excerpt we are focusing on, the advice is to stop lending her clothes.

It is worth considering in detail the way this advice is offered. In the terminology of Toulmin, Rieke and Janik's (1974) analysis of argument, the central claim is "not to lend your clothes any more" (Line 93). Backing is offered in the form of an appeal (through reported speech) to the authority of Orula ("Orula says..." (Line 93)), and immediately a warrant is added: "because that is stealing your luck" (we have translated suerte as "luck," but it could equally be "fate"). This warrant is then clarified in the form of a further claim: "The person who wears someone's clothes steals their astral, steals their luck" (Line 94). The babalawo then recommends to the client that she make her own observation; if she does so, she will see that her cousin who, he asserts, on occasion uses her clothes, is happy, content, while she, the client, is not (Lines 95-96). This is presented as empirical backing that supports the warrant for Orula's claim: due to the fact that her cousin has worn her clothes, the client's astral has been stolen. The consequence of this is that the client is unhappy, while her cousin is happy. It also counters a possible rebuttal: the "If not..." can be glossed as "If you don't believe what I am telling you, consider this...." The babalawo then provides a qualification: "because..." even though one might wash ones clothes a hundred times, the astral of the person who wore them cannot be removed (Lines 97-99). This serves to counter a possible rebuttal that the loss of one's astral might be prevented by the simple expedient of washing the clothes that have been borrowed. Then he adds what could be taken as further backing to the validity of the warrant underlying the central claim, in the form of an appeal to his authority, or a confirmation that he himself lives by the advice he is offering to her (and so a qualification to an anticipated rebuttal that the claim should also apply to him): "We, the religious, don't loan our clothing..." (Line 99). Nor do they do the reciprocal: they don't "wear the clothes of another person" (Line 102), this countering the possible rebuttal that if the effect works one way, it ought to work in the opposite direction. He adds a further qualification; not only clothing should not be shared, but also shoes, towels, soap (Line 100).

Discussion

We have seen that the consultation was an interaction with characteristics of institutional discourse. If the consultation was an institution, we would expect to find in it evidence of "institutional facts," of occasions where "X counts as Y" (Searle, 2006). Every institution defines its own reality, and those who enter have to grasp it. In the excerpt that we have analyzed, one clear example of an institutional fact is the astral. This entity is part of a local ontology, the ontology of Ifá divination, which, not surprisingly, is distinct from that of, for example, Western science. The ontology is established on the basis of evidence that is "documentary" in Garfinkel's sense: The loss of an astral is documented by the unhappiness and ill-health of its owner, for example.

Within this unfamiliar ontology, the epistemology -the reasoning and argument- has features that we can nonetheless recognize: Logical inference; appeal to empirical observation; defeasible claims. Lévy-Bruhl (1922/1923) suggested that the primitive would turn to divination, because "[t]o calculate the chances carefully and systematically, and try to think out what will happen, and make plans accordingly, is hardly the way in which primitive mentality proceeds" (p. 159). He saw divination as an alternative to careful thinking. Yet we have seen that the babalawo incites his client to think carefully about what will happen if she does not change her conduct, and to anticipate what might happen if she does. He invites her to make plans accordingly. Lévy-Bruhl (1910/1925) insisted that there is no place in primitive mentality for reasoning, or even for reasons: "The mind of the 'primitive' has hardly any room for such questions as 'how' or 'why?'" (p. 25). However, we have seen that the babalawo, explaining to his client what she must do, makes detailed and careful use of considerations of how and why. He explains why one must not share one's clothing. He provides a detailed explanation, one that is rational insofar as the claim is clearly stated, it appeals to empirical data, it is grounded in warrants, and it is given backing.

The passage, then, has a complex argumentative organization. The argument is a powerful one, however, not simply in consequence of its form. In addition, and despite its seemingly mundane topic, it deals with powerful and important issues, ones which Vygotsky also recognized. Central to his account of ontogenesis is the claim that the child is not an individual who needs to be socialized, but a thoroughly social being who needs to be individualized (Vygotsky, 1987). The advice to stop sharing one's clothes is, on a small scale, a recommendation to asset one's individuality, to become increasingly differentiated, increasingly "self-ful." Vygotsky also emphasized that human freedom consists in the recognition of necessity, and part of this necessity is the fact that we cannot directly control our behavior or thought -we can do so only through mediation, through indirect means. The person who seeks consultation and divination needs advice regarding some difficult choice or decision in their life. They may face a choice between unpalatable alternatives; they may simply not know what to do in the face of some problem or trouble. They have lost the ability to freely choose. The essence of luck might be said to be having meaningful choices among what are seen to be viable courses of action. In the absence of such choices, a person's luck has been stolen. Once meaningful choices become evident again, the person begins to have new powers and possibilities. If someone close to us is taking advantage of us in a way that reduces our individuality and our ability to make choices, then following Orula's advice may indeed help us get our luck back. Starting to say "no" to those who take advantage of us can enable us to start making more important choices. In his extended turn at this point in the consultation (and elsewhere as well) the babalawo displays his understanding of the truly human nature of luck, of fate. His argument is potent because it is about people empowering themselves through active choices of their own making. This is the kind of inference that appears to characterize the divination as institution.

Conclusions

"Wherever a theory of divination has been elicited directly from diviners

in their native language, we find a clear recognition of inductive,

intuitive and interpretative techniques and ways of knowing"

(Tedlock, 2001, p. 193).

In this article we have simply tried to study with some care and attention to detail the practice of divination, in order to see whether or not it suffered from the limitations and inadequacies that both Lévy-Bruhl and Vygotsky attributed to it. Neither of them witnessed divination first hand, as far as we can tell; they relied on others' reports of field work. On the basis of our analysis, we cannot accept the suggestion that divination works because it does not work -that it is no more than tossing an unbiased coin. Ifá divination is more than tossing shells; it is also the whole book of accumulated and condensed wisdom about how to live, plus the babalawo's expertise in seeing what may be amiss in someone's life. Perhaps the selection of a particular portion of the text is random (though an open mind is appropriate here), but whatever piece of wisdom it contains it likely to have some value. Far from determining the client's course of action -making the choice for her- the emphasis in this consultation seems to have been to encourage her to make her own thoughtful choices.

Vygotsky considered the divinatory dreaming of a Kaffir to be an example of the hierarchy among the higher psychological functions, but still a long way from modern reasoning. However, most modern Westerners today still live in a world of the unseen: of God, electrons, nuclear reactions, and much more. A select few -our wise men and women- have the ability to influence these and in a special way to see them. But for the rest of us they are mysterious entities that guide our destinies, or light our houses, or threaten our existence. Lest we assume that those of us in the Occidental world practice only scientific thinking, and that divination is to be found only in premodern societies, in backward, primitive cultures, remember that in May of 2011 a large number of people in the United States were sufficiently convinced by Harold Camping's prophesies of the end of the world that they sold their worldly goods in preparation for their transportation to the hereafter. And how many of us have purchased a lottery ticket based on our favorite number, or our birthdate? Or tried to predict the outcome of games of chance? "What is clear in most reports of North American games of chance is that the activity, even when it had crossed the line and become a pastime, was still heavily related to genuine forms of divination" (Csikszentmihalyi & Bennett, 1971, p. 47). And let us not forget that it was the illustrious Carl Jung (1950/1971) who wrote the introduction to the translation of the I Ching, the ancient Chinese book of divination. Jung believed in what he called synchronicity, or meaningful coincidence, and there are Jungian analysts today who use Tarot cards as part of their clinical practice.

Furthermore, the reasoning that Lévy-Bruhl judged irrational was being demonstrated in the context of interrogations by people who had colonized, oppressed, and often enslaved and killed those they were talking to. Bonfil (1987), writing of the treatment of indigenous peoples in the Americas, has noted how

a system of cultural control was put into effect through which the decision-making capacities of the colonized peoples were limited. Their control over various cultural elements was progressively wrenched away, as it benefited the self-interest of the colonizers in each historical period (pp. 67-68).

In such circumstances it would hardly be surprising if such peoples were to show little interest in the topics that Western researchers tried to get them to reason about. Psychologists sensitive to such effects have abandoned the use of standard tests and tasks for just these reasons (Cole, 1995).

In this article we have focused on an occasion of Ifá divination because of the importance of seeing the capabilities of a babalawo in practice. We have identified several features of the interaction between client and babalawo: an institutional discourse with long turns and short replies; frequent reported speech, glossed rather than quoted, pictorial rather than linear; reading the client, with assertions and questions that presume prior knowledge; predictions, prophesies, and the giving of advice. The turn-taking is that of institutional discourse: The client's turns are preallocated, while the babalawo's turns are less restricted. The goals of the consultation and the institution-relevant identities of the participants are evident here. The reported speech displays the babalawo's reception of his client's concerns and his sensitivity to issues that are as yet unspoken. Questions that appear to presume prior knowledge establish and maintain an atmosphere of mystique and expertize. Finally, advice is offered that is grounded in the specifics of the client's situation and in the accumulated wisdom of the book of Ifá.

We have proposed that this advice is offered in the form of reasoned argument, with clearly stated claims, warrants and grounding. If we are correct in this interpretation, divination appears not to preclude logical reasoning or empirical observation. Psychologists are inclined to view reasoning as a solitary and cognitive process. It can be, but reasoning can also be a social, contextualized activity. A babalawo does not simply consult the oracle and dictate a course of action. He must reason with the client, relating what is in the signs to events in her life, to her concerns and the reasons she chose to consult him in the first place. He must justify the course of action spoken by Orula, anticipate possible objections, and provide both logical and empirical grounding for his claim about its worth. Our analysis suggests that the babalawo is guiding his client in what amounts to a process of constitution, of self-mastery. This divination consultation is an occasion of ontological work, of the social becoming individual, of techniques for care of the self. We have picked only the most mundane episode from this consultation, because much of it dealt with very personal matters. But even here, we can see sophisticated psychological abilities at work. It is difficult, if not impossible, to pick apart the different psychological functions, but surely memory for the text, perception of the client's character, attention to the details of the oracle, are all involved. And, surely, reasoning at a high level. It is impossible to say that this divination takes place with no attention to how or why. The babalawo recommends a new way for his client to see her situation and make new choices. The courses of action he proposes amount to instructions in how to be more healthy, more wise, more spiritual. How to be.

1 "Kaffir" has become a pejorative term in Africa today, especially in South Africa, in large part because it originated in the Arabic term for unbeliever. It is a term used in the Koran in the same way. But until the early 20th century it was used to refer to natives of Southern Africa, often specifically to the Xhosa people. It is the term that Lévy-Bruhl used to refer to the natives of South Africa.

2 A pseudonym.

References

Barnet, M. (2000). La regla de Ocha: The religious system of Santería. In M. Fernández & L. Para-visini-Gebert (Eds.), Sacred possessions: Vodou, Santería, Obeah, and the Carribbean (pp. 79-100). New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Bastide, R. (1969). Las américas negras. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

Beach, K. (1993). Becoming a bartender: The role of external memory cues in a work-directed educational activity. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 7 (3), 191-204.

Betancourt, V. (2007). Ifaísmo y ciencia. Havana: Editorial Ciencias Sociales.

Bonfil, G. (1987). México profundo: una civilización negada. Mexico City: Gribaldo.

Bozhovich, E. D. (2009). Zone of proximal development: The diagnostic capabilities and limitations of indirect collaboration. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 47 (6), 48-69. doi:10.2753/ RPO1061-0405470603

Clark, K. & Holquist, M. (1984). Mikhail Bakhtin. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Clarke, J. D. (1939). Ifa divination. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 69 (2), 235-256.

Cole, M. (1995). Culture and cognitive development: From cross-cultural research to creating systems of cultural mediation. Culture & Psychology, 1 (1), 25-54.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. & Bennett, S. (1971). An exploratory model of play. American Anthropologist, 73 (1), 45-58.

De Souza, A. (2007). Ifá - santa palabra: concepto ético sobre la muerte. Havana: Ediciones Unión.

Drew, P. & Heritage, J. (1992). Analyzing talk at work: An introduction. In P. Drew & J. Heritage (Eds.), Talk at work: Interaction in institutional settings (pp. 3-65). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Evans-Pritchard, E. (1937). Witchcraft, oracles, and magic among the Azande. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Foucault, M. (1993). About the beginning of the hermeneutics of the self: Two lectures at Dartmouth. Political Theory, 21 (2), 198-227.

García, J. (2000). The Osha: Secrets of the YorubaLucumi-Santeria religion in the United States & the Americas. New York: Athelia Henrietta Press.

Garfinkel, H. (1996). Ethnomethodology’s program. Social Psychology Quarterly, 59 (1), 5-21.

Goodwin, C. & Heritage, J. (1990). Conversation analysis. Annual Review of Anthropology, 19, 283-307.

Heritage, J. (1998). Conversation analysis and institutional talk: Analyzing distinctive turn-taking systems. In S. Cmejrková, J. Hoffmannová, O. Müllerová, & J. Svetlá (Eds.), Proceedings of the 6th International Congress of IADA (International Association for Dialog Analysis) (pp. 3-17). Tübingen, Germany: Niemeyer.

Heritage, J. (2005). Conversation analysis and institutional talk. In K. L. Fitch & R. E. Sanders (Eds.), Handbook of language and social interaction (pp. 103-147). New Jersey: Erlbaum.

Hutchins, E. (1995). Cognition in the wild. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hyman, R. (1977). ‘Cold reading’: How to convince strangers that you know all about them. The Zetetic, 1 (2), 18-28.

Jung, C. G. (1971). Foreword to The I Ching or book of changes. In H. Read & G. Adler (Eds.), Psychology and religion: West and east (The collected works of C. G. Jung) (Vol. 11, pp. 589-608). New York: Pantheon. (Original work published 1950).

Laidlaw, J. (2005). A life worth leaving: Fasting to death as telos of a Jain religious life. Economy and Society, 34 (2), 178-199. doi:10.1080/03085140500054545

Lave, J. (1991). Situating learning in communities of practice. In L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, & S. D. Teasely (Eds.), Perspectives on socially shared cognition (pp. 63-82). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Lévy-Bruhl, L. (1923). Primitive mentality. London: Allen & Unwin. (Original work published 1922).

Lévy-Bruhl, L. (1925). How natives think. London: Allen & Unwin. (Original work published 1910).

Moore, O. K. (1957). Divination: A new perspective. American Anthropologist, New Series, 59 (1), 69-74.

Myhre, K. C. (2006). Divination and experience: Explorations of a Chagga epistemology. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 12 (2), 313-330.

Packer, M. J. (2008, September). The ontogenesis of the individual as the meeting place for critical social theories. Paper presented at the Triennial Meetings of the International Society for Culture and Activity Research, San Diego.

Packer, M. J. (2010). Educational research as a reflexive science of constitution. In W. R. Penuel & K. O’Connor (Eds.), Learning Research as a Human Science (pp. 17-33). National Society for the Study of Education Yearbook, 109 (1).

Packer, M. J. (2011). The science of qualitative research. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rose, M. (2001). The working life of a waitress. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 8 (1), 3-27. doi:10.1207/ S15327884MCA0801_02

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turntaking in conversation. Language, 50, 696-735.

Schegloff, E. A. (1995). Discourse as an interactional achievement III: The omnirelevance of action. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 28 (3), 185-211.

Scribner, S. (1977). Modes of thinking and ways of speaking: Culture and logic reconsidered. In P. C. Johnson-Laird & P. C. Wason (Eds.), Thinking: Readings in cognitive science (pp. 483-500). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Scribner, S. (1985). Knowledge at work. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 16 (3), 199-206.

Searle, J. R. (2006). Social ontology: Some basic principles. Anthropological Theory, 6 (1), 12-29. doi:10.1177/1463499606061731

Tedlock, B. (2001). Divination as a way of knowing: Embodiment, visualisation, narrative, and interpretation. Folklore, 112 (2), 189-197.

Tibaduiza, S. (2010a). Itinerarios terapeutico-religiosos en el sistema de adivinación e interpretación de Ifá en la ciudad de Bogotá (Unpublished senior thesis). Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá: Colombia.

Tibaduiza, S. (2010b). Procesos de aprendizaje de los babalawos en la Santería Cubana en Bogotá (Unpublished senior thesis). Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia.

Toulmin, S., Rieke, R., & Janik, A. (1974). An introduction to reasoning. New York: Macmillan.

Turner, V. (1961). Revelation and divination in Ndembu ritual. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

UNESCO. (2008). Ifa divination system: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, Cultural Sector, Intangible Heritage. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/index.php?lg=en&pg=00011&RL=00146

Voloshinov, V. N. (1929). Marxism and the philosophy of language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Concrete human psychology [Written 1929]. Soviet Psychology, 27 (2), 53-77.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). Thinking and speech. In R. W. Rieber & A. S. Carton (Eds.), The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky. Volume 1: Problems of general psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 39-285). New York: Plenum Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1997). The history of the development of higher mental functions. In R. W. Rieber (Ed.), The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky (Vol. 4, whole volume). New York: Plenum Press.

Wedel, J. (2004). Santería healing: A journey into the Afro-Cuban world of divinities, spirits, and sorcery. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Wyllie, R. W. (1970). Divination and face-work. British Journal of Sociology, 21 (1), 52-62.

Zeitlyn, D. (1990). Professor Garfinkel visits the soothsayers: Ethnomethodology and Mambila divination. Man, 25 (4), 654-666.

Zeitlyn, D. (2001). Finding meaning in the text: The process of interpretation in text-based divination. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 7 (2), 225-240.