Introduction

The concepts of evidence-based medicine, which are based on the critical appraisal of individual studies, gave rise to systematic reviews, and these, in turn, to clinical practice guidelines (CPG).1 CPGs are documents in which, after following a predetermined process, recommendations are included for their users, who are usually health professionals, but can also be patients or their caregivers.2 Such recommendations are the structural units of the CPGs and the product of the methodological process. They usually derive from a systematic review of the evidence, carried out with the aim of obtaining answers to the questions of interest formulated in the CPG.3

Moreover, besides the assessment of the specific evidence for each clinical question, recommendations should integrate the assessment of other contextual aspects that also influence clinical decisions (e.g., availability, risk-benefit balance, and acceptability).4 Based on these elements, the CPG development groups choose to recommend a health decision.5

Evidence-based recommendations (EBRs) are statements that seek to guide users of CPGs to make informed decisions about the most appropriate course of action to prevent, diagnose, or treat a specific clinical condition.6 In this sense, the recommendations are intended to optimize patient care, avoiding unjustified variability in clinical practice. If adherence to the recommendations is adequate, an improvement in patient health indicators is expected (by incorporating decisions of proven usefulness), as well as greater efficiency in health systems (by discouraging decisions that do not add value), a reduction in the financial impact of the disease, and greater equity in healthcare decisions.7

While there are several approaches to EBR development, such as those of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)8 and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN),9 the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system, since its development in 2000, is frequently used for this purpose as it has addressed limitations identified in other approaches and has received input from several international organizations that now consider it the standard methodology for EBR development.10 One of the main characteristics of the GRADE system is that it allows structuring and making explicit the process of grading the quality of evidence, thus supporting the recommendations made in the CPGs.11

GRADE allows the user of the EBR to be informed about the certainty of the evidence that supports it based on explicit criteria (risk of bias, consistency, precision, disagreement between the evidence and the field of application of the recommendation [indirectness], and publication bias). This assessment leads to a four lever ordinal rating of evidence (high, moderate, low, or very low). This assessment is usually presented by methodologists to the other members of the CPG development group, who establish the strength of the recommendation.12,13 The relationship between the level of certainty of the evidence and the strength of the recommendation may be discordant (e.g., when a strong recommendation is generated based on low-quality evidence) when considering additional situations (e.g., a possible risk of a catastrophic event, or a possibly beneficial low-cost and relatively harmless intervention).14,15

Once an EBR has been formulated, it should be written in such a way that the user can clearly identify the recommended course of action (its direction) and the strength of the recommendation.13-17 In this sense, recommendations can be classified into four categories according to their direction and strength: recommendations for or against the decision and strong or weak (or conditional) recommendations.7,12,15

In Colombia, a CPG production process has undertaken in recent years with the aim of guiding the management of priority health conditions. In 2010, the Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection (CMHSP), together with the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, published a methodological guide for the preparation of comprehensive care guidelines in the general social security system, which was updated in 2014. This guide is intended to standardize the CPG development process, including the use of the GRADE approach for the drafting and presentation of the recommendations to be included in the CPGs.16 In accordance with the guidelines established in this guide, the CMHSP commissioned various development groups to produce three versions of CPGs (a comprehensive guideline with methodological support and two versions aimed at end users: one for health professionals and the other for patients/caregivers).6

In the case of the version addressed to professionals, the CMHSP methodological guide defined the elements that should be included to create a structure for the recommendations section and facilitate its use, namely: clinical question, short summary of evidence with a rating of its certainty, and the recommendation, always stating its strength.6 The document also includes guidelines for the wording of recommendations, such as the use of appropriate terms to reflect the strength of the recommendation and facilitate its understanding and implementation: “we recommend...” or “clinicians should...” for strong recommendations and “we suggest...” or “clinicians might...” for weak recommendations.

Currently, there is a Colombian CMHSP repository with more than 50 CPGs on different health conditions.17 However, even though the CPG development process began over a decade ago and that there is a methodological reference guide for its development,6 there is no overall assessment of the outcomes of this process. Particularly, the development patterns of the EBRs contained in such CPGs remain unknown. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to explore the characteristics of the recommendations included in the CPGs commissioned by the CMHSP between 2013 and 2021 to establish a starting point for approaching the editorial process and to identify areas for improvement.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

A systematic search of CPGs published by the CMHSP between 2013 and 2021 was performed. The identification of eligible CPGs was based on three official reporting sources: the CMHSP digital repository of CPGs,17 the Colombian national open data platform,18 and a request addressed to the CMHSP. CPGs that used the GRADE system for their comprehensive development and explicitly provided a rating for the certainty of the evidence and the strength of the recommendation in at least 70% of their recommendations were considered eligible. Adopted CPGs, CPGs in their patient-directed version, and previous versions of CPGs for which an updated version was already available were excluded. Two reviewers (AMB and AM) independently confirmed the eligibility of the documents based on a review of the titles and full text of the identified CPGs. Duplicates were excluded and disagreements between these two reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer (JCV).

Data extraction

Two reviewers (AMB and AM) extracted information on the general characteristics of the CPGs and the recommendations included in them; this process was carried out using the full versions of each guideline. Then, another two reviewers (DQ and FA) independently compared these data using the practitioner versions to identify differences between the information reported by the development groups and the information delivered to the end users. Disagreements were resolved by consensus between the pairs of reviewers based on what was reported in their respective sources of information, without the need for a third reviewer. Data were extracted in predesigned formats. The aspects reviewed and the variables included based on the methodological guide6 were:

- CPG identification information: year of publication, development group, number of recommendations, and thematic group.

- Characteristics of the recommendations according to the GRADE system: rating of the certainty of the evidence (high-moderate, low-very low, expert consensus), direction (for, against) and strength (weak/conditional, strong). Other comments made by the development groups, e.g., good clinical practice points, were not considered.

Additionally, based on the criteria suggested in the CMHSP methodological guides for the development of CPGs,6 the following elements of the wording of recommendations were reviewed: verbs used depending on the strength of the recommendation (e.g., the words “suggested” or “might” for weak recommendations and “recommended” or “should” for strong recommendations), explicit clinical question, summary of accompanying evidence (approximately two paragraphs), certainty of the body of evidence, recommendation, and associated strength. The latter criteria were reviewed in a stratified random sample of approximately 20% of the recommendations of each of the CPGs included (n=324); it should be noted that in this case the recommendations available in the versions of the CPGs aimed at healthcare professionals were reviewed.

Statistical analysis

The initial step in analyzing the information was to categorize the CPGs into thematic groups (cancer, genetic diseases, infectious diseases, ophthalmologic diseases, rheumatologic diseases, newborn, trauma, and cardiovascular and metabolic diseases), while the recommendations were categorized based on the healthcare process they addressed (prevention, screening, diagnosis, treatment, follow-up/complications, rehabilitation, prognosis, and others).

The information entered in the predesigned formats was then exported to data sheets created in Microsoft Excel for analysis. Data are described using absolute frequencies, percentages, medians, and interquartile ranges.

Results

Selection of CPGs

Fifty-nine eligible CPGs were identified, of which 23 were excluded for the following reasons: being CPGs adopted/adapted from international CPGs (n=9; 15.25%), not using the GRADE system (n=3; 5.08%), employing several systems besides GRADE for the formulation of EBRs (n=2; 3.39%), or not explicitly presenting the certainty of evidence in 70% or more of the recommendations (n=9; 15.25%). Consequently, 36 CPGs were included for full-text analysis (1 609 recommendations in total). The process of identifying and selecting guidelines based on the results of the systematic search is described in Figure 1.

|

Identification of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs)

|

|

|

Identification

|

|

CPGs identified from:

CMHSP repository (n=56)

Datos.gov platform (n=41)

CMHSP reports (n=3)

|

|

CPGs excluded prior to screening:

Due to duplication (n= 41)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Screening

|

|

Reviewed CPGs (n=59)

|

|

Excluded CPGs (n=14):

Adoption guidelines (n=9)

No GRADE (n=3)

GRADE and other systems (n=2)

|

|

|

|

|

|

CPGs evaluated for eligibility

(n=45)

|

|

Excluded CPGs:

Certainty of evidence rating for less than 70% of the recommendations (n=9)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Included

|

|

CPGs included in the review

(n=36; 1 609 recommendations)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Additional analysis

|

|

Sample of recommendations for review of characteristics and wording of recommendations section (20% of recommendations included) (n=324)

|

|

|

CPG: Clinical Practice Guidelines; CMHSP: Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection.Figure 1. Flowchart of the CPG selection process.

Source: Own elaboration.

Characteristics of the CPGs

In most of the CPGs, the development process was led by universities (n=26), followed by healthcare institutions (n=5) and the Instituto de Evaluación de Tecnologías en Salud (Institute for Health Technology Assessment) (n=3). The remaining two CPGs were prepared by an independent research institute and a scientific society. For analysis, the CPGs were classified into 8 thematic groups. The main characteristics of the CPGs included in the analysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of clinical practice guidelines commissioned by the Colombian Ministry of Health between 2013 and 2021 and included for analysis in the present study.

|

CPG

|

Development group

|

Type of institution in charge of developing the CPG

|

Year of publication

|

Edition

|

Thematic group

|

# of Recommendations

|

|

Healthy newborn 19

|

PUJ

|

University

|

2013

|

First

|

Newborn

|

40

|

|

Preterm newborn20

|

PUJ

|

University

|

2013

|

First

|

Newborn

|

62

|

|

Newborn with respiratory disorder21

|

PUJ

|

University

|

2013

|

First

|

Newborn

|

56

|

|

Newborn with early neonatal sepsis22

|

PUJ

|

University

|

2013

|

First

|

Newborn

|

41

|

|

Newborn with perinatal asphyxia23

|

PUJ

|

University

|

2013

|

First

|

Newborn

|

16

|

|

Sexually transmitted infections and other infections of the genital tract 24

|

UNAL

|

University

|

2013

|

First

|

Infectious diseases

|

132

|

|

Early detection, treatment, follow-up and rehabilitation of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis25

|

UNAL

|

University

|

2014

|

First

|

Rheumatic diseases

|

55

|

|

Early detection, treatment, follow-up and rehabilitation of patients with rheumatoid arthritis26

|

UNAL

|

University

|

2014

|

First

|

Rheumatic diseases

|

88

|

|

Prevention and early detection, treatment and follow-up of dyslipidemias in the population over 18 years of age27

|

PUJ

|

University

|

2014

|

First

|

Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases

|

46

|

|

Prevention, diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation and follow-up of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)28

|

PUJ

|

University

|

2014

|

First

|

Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases

|

49

|

|

Diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation of patients with cranioencephalic trauma29

|

Fundación Meditech

|

Research institute

|

2014

|

First

|

Trauma

|

25

|

|

Diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of skin cancer: actinic keratosis30

|

FUCS

|

University

|

2014

|

First

|

Cancer

|

27

|

|

Diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of skin cancer: squamous cell cancer31

|

FUCS

|

University

|

2014

|

First

|

Cancer

|

35

|

|

Diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of skin cancer: basal cell cancer32

|

FUCS

|

University

|

2014

|

First

|

Cancer

|

52

|

|

Lung cancer prevention, detection, treatment and rehabilitation33

|

INC

|

Healthcare provider institution

|

2014

|

First

|

Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases

|

47

|

|

Early detection, comprehensive care, follow-up and rehabilitation of patients diagnosed with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Becker muscular dystrophy, and myotonic dystrophy34

|

UdeA

|

University

|

2014

|

First

|

Genetic diseases

|

76

|

|

Cystic fibrosis prevention, diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation35

|

ACN

|

Scientific society

|

2014

|

First

|

Genetic diseases

|

36

|

|

Comprehensive care of gestational and congenital syphilis36

|

UNAL

|

University

|

2014

|

First

|

Infectious diseases

|

19

|

|

Risk assessment and initial treatment of pneumonia in children under 5 years of age and bronchiolitis in children under 2 years of age37

|

UdeA

|

University

|

2014

|

First

|

Infectious diseases

|

21

|

|

Identification and clinical management of pertussis in children under 18 years of age38

|

IETS

|

Health Technology Assessment Agency

|

2014

|

First

|

Infectious diseases

|

19

|

|

Cervical cancer (pcl)39

|

INC

|

Healthcare provider institution

|

2014

|

First

|

Cancer

|

19

|

|

Invasive cervical cancer 40

|

INC

|

Healthcare provider institution

|

2014

|

First

|

Cancer

|

22

|

|

Diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of gestational diabetes41

|

PUJ

|

University

|

2016

|

First

|

Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases

|

21

|

|

Diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of type I diabetes42

|

PUJ

|

University

|

2015

|

First

|

Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases

|

17

|

|

Diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of type II diabetes in the population over 18 years of age43

|

PUJ

|

University

|

2016

|

First

|

Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases

|

32

|

|

Diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation of acute episode of ischemic stroke in population over 18 years of age44

|

UNAL

|

University

|

2015

|

First

|

Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases

|

92

|

|

Preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative diagnosis and treatment of the amputee, prosthesis prescription, and comprehensive rehabilitation45

|

UdeA

|

University

|

2015

|

First

|

Trauma

|

43

|

|

Prevention, early detection, diagnosis and treatment of refractive errors in children under 18 years of age46

|

FUCS

|

University

|

2016

|

First

|

Eye Diseases

|

29

|

|

Prevention, early detection, diagnosis and treatment of amblyopia in children under 18 years of age47

|

FUCS

|

University

|

2016

|

First

|

Eye Diseases

|

28

|

|

Prevention, diagnosis, treatment of obesity in adults48

|

FUCS

|

University

|

2016

|

First

|

Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases

|

36

|

|

Prevention, diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation of heart failure in the population over 18 years of age49

|

UdeA

|

University

|

2016

|

First

|

Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases

|

69

|

|

Acute coronary syndrome50

|

UdeA

|

University

|

2017

|

Third

|

Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases

|

78

|

|

Detection, treatment and follow-up of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas in population over 18 years of age51

|

INC

|

Healthcare provider institution

|

2017

|

First

|

Cancer

|

36

|

|

Detection, treatment and follow-up of lymphoid and myeloid leukemias in the population over 18 years of age52

|

INC

|

Healthcare provider institution

|

2018

|

First

|

Cancer

|

44

|

|

HIV/AIDS infection in children and adolescents53

|

IETS

|

Health Technology Assessment Agency

|

2021

|

Second

|

Infectious diseases

|

49

|

|

HIV/AIDS infection in adults, pregnant women, and adolescents54

|

IETS

|

Health Technology Assessment Agency

|

2021

|

Second

|

Infectious diseases

|

52

|

ACN: Asociación Colombiana de Neurología; FUCS: Fundación Universitaria de Ciencias de la Salud; CPG: clinical practice guideline; INC: Instituto Nacional de Cancerología; PUJ: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana; UdeA: Universidad de Antioquia; UNAL: Universidad Nacional de Colombia; PCL: precancerous lesions; IETS: Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud.

Source: Own elaboration.

The median number of recommendations per CPG was 41 (IQR: 28) (Table 2). When analyzing the distribution of the CPGs by year of publication, it was observed that the majority were published in 2014 (n=16) and that they contained 39.53% of the recommendations. On the other hand, the median number of recommendations per guideline varied between 28.5 and 71.5 in the 8 thematic groups, where the highest median was observed in the “rheumatic diseases” thematic group and the lowest in “trauma” (Table 3). It was also found that “cardiovascular and metabolic diseases” was the thematic group with the highest number of CPGs (n=9) and recommendations (27.35%), followed by “cancer” and “infectious diseases”.

Table 2. Distribution of clinical practice guidelines and recommendations by year of publication.

|

Year of publication

|

CPGn

|

Recommendations

n (%)

|

Median number of recommendations per CPG

|

IQR

|

|

2013

|

6

|

347 (21.57)

|

48.5

|

45.5

|

|

2014

|

16

|

636 (39.53)

|

35.5

|

30

|

|

2015

|

3

|

152 (9.45)

|

43

|

75

|

|

2016

|

6

|

215 (13.36)

|

30.5

|

18

|

|

2017

|

3

|

158 (9.82)

|

44

|

42

|

|

2021

|

2

|

101 (6.28)

|

50.5

|

-

|

|

Total

|

36

|

1 609 (100)

|

41

|

28

|

CPG: clinical practice guideline; IQR: interquartile range.

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 3. Distribution of clinical practice guidelines and recommendations by thematic group.

|

Topic

|

CPG

n

|

Recommendations

n (%)

|

Median number of recommendations per

CPG

|

IQR

|

|

Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases

|

9

|

440 (27.35)

|

46

|

47

|

|

Cancer

|

8

|

282 (17.53)

|

35.5

|

23

|

|

Infectious diseases

|

6

|

292 (18.15)

|

35

|

53

|

|

Newborn

|

5

|

215 (13.36)

|

41

|

31

|

|

Genetic diseases

|

2

|

112 (6.96)

|

56

|

-

|

|

Eye diseases

|

2

|

57 (3.54)

|

28.5

|

-

|

|

Rheumatic diseases

|

2

|

143 (8.89)

|

71.5

|

-

|

|

Trauma

|

2

|

68 (4.23)

|

34

|

-

|

|

Total

|

36

|

1609 (100)

|

41

|

28

|

CPG: clinical practice guideline; IQR: interquartile range.

Source: Own elaboration.

Characteristics of the recommendations

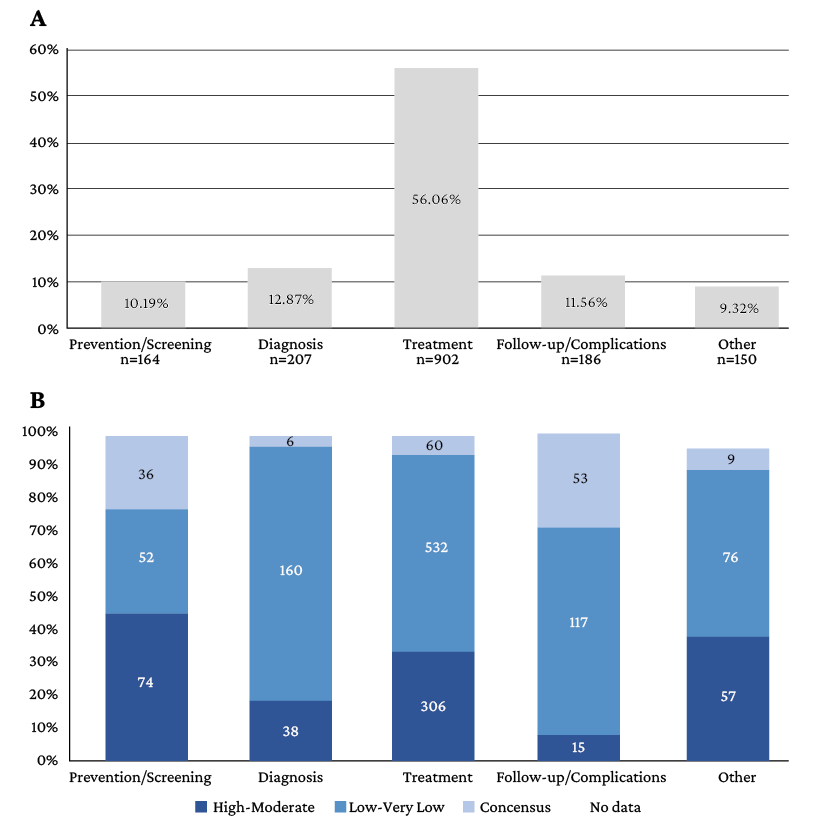

The majority of recommendations refer to treatment (56.06%) (Figure 2A). Furthermore, when analyzing the level of certainty of the evidence of the recommendations based on the stage of the healthcare process they addressed, it was found that in the case of recommendations on diagnosis, treatment and follow-up/complications there was a higher proportion of recommendations based on low/very low-quality evidence, while in those on prevention/stimulation, recommendations based on moderate-high quality evidence were more frequent (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. A) Distribution of recommendations by stage of the healthcare process they address; B) Distribution of recommendations on each stage of the care process by level of evidence on which they are based. Recommendations in which no information on the level of evidence was provided: Screening: 2; Diagnosis: 3; Treatment: 4; Follow-up/Complications: 1; Other: 8.

Source: Own elaboration.

Regarding the attributes of the recommendations according to the GRADE system, the following was found: 81.04% of the recommendations are strong for the intervention, 58.23% are based on evidence with low or very low certainty, 30.45% are based on evidence with high or moderate certainty, 10.19% are based on expert consensus, and 1.12% do not provide this information. Moreover, 62.77% of the recommendations were rated as strong, 34.74% as weak/conditional, and 2.49% did not provide this information.

Table 4 shows the distribution of recommendations by strength and certainty of evidence. In the case of strong recommendations, 38.91% are based on evidence with moderate to high certainty, 51.39% on evidence with low to very low certainty, and 9.11% on expert consensus. As for weak/conditional recommendations, 17.35% are based on evidence with moderate to high certainty, 74.60%, on evidence with low to very low certainty, and 6.44%, on expert consensus. Also, 90% of the recommendations for which no information on their strength is reported are based on expert consensus.

Table 4. Certainty of evidence by strength of recommendations.

|

Certainty

|

Strength

|

|

Weak/conditional

n (%)

|

Strong

n (%)

|

No data

n (%)

|

Total

n (%)

|

|

Low - Very low

|

417 (74.60)

|

519 (51.39)

|

1 (2.50)

|

937 (58.23)

|

|

High - Moderate

|

97 (17.35)

|

393 (38.91)

|

0 (0.0)

|

490 (30.45)

|

|

Consensus

|

36 (6.44)

|

92 (9.11)

|

36 (90)

|

164 (10.19)

|

|

No data

|

9 (1.66)

|

6 (0.59)

|

3 (7.50)

|

18 (1.12)

|

|

Total

|

559 (100)

|

1 010 (100)

|

40 (100)

|

1 609 (100)

|

Source: Own elaboration.

Findings from the review of general characteristics of recommendations and review of wording elements

The following are the findings of the review of the wording elements in the 324 randomly selected recommendations:

- Recommendations including clinical question: 295 (91.05%)

- Recommendations with a summary of evidence: 172 (53.25%), of which 104 (60.47%) have 2 or less paragraphs.

- Recommendations in which the terms used to express the strength of the recommendation are appropriate: 297 (91.67%)

- Strong recommendations using terms such as “recommended”, “should” or similar: 206

- Weak recommendations using terms such as “suggest”, “might” or similar: 91

Furthermore, the most frequent finding in the review of general characteristics of the 1 609 recommendations was disagreement between the certainty of the evidence and the strength of the recommendation (38.28%), especially strong recommendations based on evidence with low or very low certainty (32.26%). However, it should be noted that, compared to the recommendations included in CPGs published in 2013, a decrease in the frequency of this disagreement was observed in those included in CPGs published in 2021 (45.24% vs. 35.64%). Similarly, in the analysis by year of publication, it was observed that from 2015 onwards, information on the strength of the recommendation and the certainty of the evidence was included in all recommendations (Table 5).

Regarding the review of the wording elements of the recommendations (n=324), the most common finding was the disagreement between certainty of evidence and language (50.31%), mainly the use of terms such as “should” or “recommended” in recommendations based on evidence with low or very low certainty (n=120, 73.62%). In addition, it is worth mentioning that the proportion of strength/language mismatches (+/-or -/+) and the frequency of certainty/strength/language mismatches (+/-/+ o -/+/-) decreased considerably in the recommendations included in CPGs published in the most recent years.

Table 5 presents the findings identified in the review of the general characteristics of the 1 609 recommendations by year of CPG publication (certainty of evidence, strength, direction, and comparison between CPG versions). In turn, Table 6 summarizes the results of the review of the wording elements (structure and language) of 324 randomly selected recommendations (clinical question, short evidence summary, agreement between the language and the characteristics of the recommendation).

Given that there may have been one or more findings in a single recommendation, it should be pointed out that the percentages were calculated using the number of recommendations reviewed per year of publication of the CPGs as the denominator. Consequently, these percentages should not be added together for interpretation.

Table 5. Distribution of the findings identified in the review of the general characteristics of the recommendations by year of publication of the clinical practice guidelines in which they were included (n=1 609).

|

Year

|

|

2013

n (%)

|

2014

n (%)

|

2015

n (%)

|

2016

n (%)

|

2017

n (%)

|

2021

n (%)

|

Total

n (%)

|

|

Reviewed recommendations by year *

|

347 (100)

|

636

(100)

|

205

(100)

|

162

(100)

|

158

(100)

|

101

(100)

|

1 609

(100)

|

|

Disagreement certainty - /strength +

|

157 (45.24)

|

154 (24.21)

|

81 (39.51)

|

40 (24.64)

|

51 (32.28)

|

36 (35.64)

|

519 (32.26)

|

|

Disagreement certainty + / strength -

|

11 (3.17)

|

55 (8.65)

|

2 (0.98)

|

18 (11.11)

|

8 (5.06)

|

3 (2.97)

|

97 (6.03)

|

|

No data on strength

|

1 (0.28)

|

39 (6.13)

|

0 (0)

|

0 (0)

|

0 (0)

|

0 (0)

|

40 (2.49)

|

|

Editorial findings **

|

5 (1.44)

|

7 (1.10)

|

0 (0)

|

2 (1.23)

|

1 (0.63)

|

4 (3.96)

|

19 (1.18)

|

|

No data on certainty

|

11 (3.17)

|

8 (1.26)

|

0 (0)

|

0 (0)

|

0 (0)

|

0 (0)

|

19 (1.18)

|

* There may have been one or more findings in a single recommendation.

** Different certainty of evidence, strength or direction between versions of the CPG (full version and practitioner version) | Omission of recommendation in practitioners’ version | Point of good practice in full version converted to recommendation in practitioners’ version.

Certainty + = High/moderate certainty | Certainty - = Low/very low certainty

Strength - = Weak/conditional | Strength + = StrongSource: Own elaboration.

Table 6. Distribution of the findings identified in the review of the wording of the recommendations by year of publication of the clinical practice guidelines in which they were included (n=324).

|

Year

|

|

2013

n (%)

|

2014

n (%)

|

2015

n (%)

|

2016

n (%)

|

2017

n (%)

|

2021

n (%)

|

Total

n (%)

|

|

Reviewed recommendations by year *

|

70 (100)

|

130 (100)

|

39 (100)

|

33 (100)

|

32 (100)

|

20 (100)

|

324 (100)

|

|

Certainty/language disagreement (+/- o -/+)

|

51 (72.85)

|

50 (38.46)

|

17 (43.59)

|

19 (57.58)

|

9 (28.13)

|

17 (85.00)

|

163 (50.31)

|

|

No evidence summary

|

29 (41.42)

|

40 (30.76)

|

29 (100)

|

37 (86.05)

|

16 (50)

|

1 (5.00)

|

152 (46.91)

|

|

With summary of evidence >2 paragraphs

|

1 (1.42)

|

35 (26.97)

|

0 (0)

|

6 (15.38)

|

16 (50)

|

10 (50)

|

68 (20.99)

|

|

No clinical question

|

27 (38.57)

|

2 (1.54)

|

0 (0)

|

0 (0)

|

0 (0)

|

0 (0)

|

29 (8.95)

|

|

Force/language disagreement (+/- o -/+) **

|

17 (24.29)

|

3 (2.31)

|

0 (0)

|

0 (0)

|

1 (3.13)

|

0 (0)

|

21 (6.48)

|

|

Certainty/strength/language disagreement (+/-/+ o -/+/-)

|

3 (4.28)

|

1 (0.77)

|

0 (0)

|

0 (0)

|

0 (0)

|

0 (0)

|

4 (1.23)

|

* There may have been one or more findings in a single recommendation.

** Six recommendations could not be rated because the strength was not explicitly reported.

Strength - = Weak/conditional | Strength + = Strong

Language + = “should” or similar | Language - = “suggested” or similar

Certainty + = High/moderate certainty | Certainty - = Low/very low certaintySource: Own elaboration.

Discussion

The present study included 36 Colombian CPGs, most of them published between 2013 and 2014 (n=22). During this period, the production of CPGs in the country was promoted by the CMHSP by funding the calls for proposals 509 of 2009 and 563 of 2012 of the Administrative Department of Science, Technology and Innovation - Colciencias (currently Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation) or by allocating resources via agreements or contracts 36 of 2012, 529 of 2013, and 550 of 2013.

Regarding the analysis of the 1 609 recommendations contained in these 36 CPGs, the following were the main findings: there was a wide variation among the number of recommendations per CPG, both by year of publication (median recommendations per CPG between 32 to 50.5) and by topic group (median recommendations per CPG between 28.5 and 71.5); treatment was the most commonly addressed stage of the care process (>50% of recommendations); and the majority were in favor (>80%) and rated as strong (>60%).

In the present, study we found that, although the majority of the recommendations are classified as strong (n=1 010, 62.77%), only 38.91% of them are based on evidence with high or moderate certainty, which can lead to discussions and difficulties in their effective implementation in clinical practice. Likewise, the fact that there is such a high proportion of strong recommendations based on evidence with low or very low certainty or on expert consensus, or even that this information is not reported, suggests the need to review the criteria considered by the CPG development groups to assign the strength of the recommendations and the GRADE system guidelines on this aspect to determine whether or not these disagreements are justified.55

On the other hand, considering the high proportion of evidence-based recommendations with a low or very low level of certainty, further CPGs to be developed in the country should include recommendations for research as in other countries, since the uncertainty about the management of different diseases/health conditions is evident despite their high prevalence.8 There is also a clear need to connect the gaps identified by the CPG development groups with future calls for research in the country. Likewise, there is a need to promote the development of high-quality clinical studies that will provide better evidence for the development of CPGs.

With regard to the review of the elements for drafting the recommendations, different levels of adherence to the criteria suggested in the CMHSP methodological guide were observed.6 For example, regardless of the year of publication, there was a high frequency of disagreement between the certainty of the evidence and the language used, and CPGs published in the later years of the study period showed greater adherence to explicit presentation of the wording characteristics of the recommendation, as well as greater consistency between the strength of the recommendation and the terms (verbs) used. In this sense, it is expected that greater compliance with these criteria in the CPGs published in the country in the last few years will provide a solid tool for clinical decision making and will allow for a better use of these CPGs.

On this point, Cabrera & Pardo,56 in a study that analyzed the impact of the GRADE system on the development of CPGs in Latin America and the Caribbean, stated that the heterogeneous wording and presentation format of the recommendations make it more difficult for users to read the CPGs. Similarly, according to Delgado-Noguera et al.,57 who evaluated the methodological quality of Colombian CPGs in pediatrics, the wording of these documents should be clear and coherent, as their critical reading is necessary for the adequate implementation of the recommendations contained in them.

Concerning the general characteristics of the recommendations, we found that in the following aspects our findings are similar to those reported by Alexander et al.58 in a study that characterized 456 recommendations from 43 WHO CPGs: proportion of strong recommendations (62.67 vs. 63.4%), total percentage of strong recommendations based on evidence of low or very low certainty (51.39 vs. 55.5%), and percentage of favorable recommendations (81.04 vs. 87.7%). In the case of the proportion of weak recommendations based on low or very low certainty, although it was high in both studies, it was much higher in the study by Alexander et al.58 (74.60% vs. 85%).

The EBR formulation process has several implications. Consequently, recommendations should be formulated appropriately following the GRADE system, and when the evidence is not sufficient to support the development of strong recommendations, cases that have been defined as possible justifications for presenting recommendations with disagreements between their strength and the certainty of the evidence on which they are based should be considered.55

Likewise, it should be kept in mind that presenting strong recommendations supported by evidence with low or very low certainty could lead to a lack of interest on the part of decision-makers. Both clinicians and public policy decision-makers may be less motivated to expand knowledge on certain topics if they perceive that, because they are strong recommendations, there is less uncertainty about benefits and harms.59

It is understandable that the methodological guide for the elaboration of CPGs in Colombia6 does not contain indications on the number of recommendations to be included in a CPG, as this depends on the health condition to be treated in the guideline and the clinical approach to patients. Regardless of the number, the final recommendations should be the result of a rigorous exercise based on prioritization of issues and verification of the existence of supporting evidence (and if so, analysis of that evidence), which is reflected in the assignment of the strength and direction of the recommendations.59 Likewise, it is important to differentiate the use of recommendations from the use of other resources such as good clinical practice guidelines, which do not require supporting evidence, since the desirable effects outweigh the undesirable ones.6 Compliance with these considerations would reduce the complexity of the CPGs and facilitate implementation and adherence to the recommendations contained therein by end users.60

Thus, a CPG development process that rigorously adheres to the established methodological guidelines6 will be a fundamental step in strengthening the Colombian health system,57 because if standards of management based on scientific evidence are established, it will be possible to standardize treatment protocols and optimize the use of resources. This will not only contribute to more effective and safer healthcare delivery but could also help reduce unnecessary variations in medical practice. However, it is also essential to ensure that both the guidelines and their implementation process are adequately adjusted to the local reality, considering the complexity of the health system and the particularities of the Colombian population. Furthermore, key institutions in the country, such as the Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud, should be strengthened and the offer of training programs in the development of CPGs should be improved and expanded, as this will result in a greater number of health professionals duly trained for this purpose.

As for limitations, it should be mentioned that the present study focused on the description of the recommendations contained in the CPGs and, therefore, syntactic, semantic and pragmatic aspects of the recommendations (number of words, readability, and meaning) were not evaluated, nor were the implications of the conformation of the development groups. However, it provides, by means of a systematic review, a comprehensive and broad overview of the CPGs produced in Colombia in recent years.

It should also be mentioned that the CMHSP CPG website was suspended during the course of this study and some of the documents that were available there were versions that had been published prior to the issuance of their ISBN. As of July 2023, the documents are available on the Internet, but not uploaded to a repository, limiting access to their contents by physicians and health institutions that use them as a strategy for implementing and disseminating evidence-based medicine.61

Conclusions

The present review of the characteristics of the CPGs commissioned by the CMHSP between 2013 and 2021 reveals that the CPG development process in Colombia acceptably complies with the universal methodology for the development of this type of document. In addition, the evaluated CPGs have a relatively high number of recommendations, most of them in favor of an intervention and rated as strong but based on low or very low-quality evidence. This situation could promote an excess of decisions with little supporting evidence, resulting in controversy, higher costs, and possible barriers to the implementation of the recommendations.

We also identified areas for methodological improvement and a worrying decline in the development/updating of these documents. However, we believe that as these aspects are improved and the CPG development process is strengthened, Colombia will be in a favorable position to improve the quality of medical care and contribute to the advancement of evidence-based clinical practices for the benefit of patients.

Conflicts of interest

JCV participated as a leader in the process of developing and updating the CPG on primary arterial hypertension, which was not included in this study because it did not explicitly present the certainty of the evidence in the recommendations section. This CPG, like other documents that were also excluded, presents said information in other sections that were not evaluated.

Funding

This study is part of the Estudio de Impacto de Estrategias de Información para Modificar Conocimientos, Actitudes y Prácticas en Enfermedades Crónicas en Bogotá (Impact Study of Information Strategies to Modify Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices in Chronic Diseases in Bogotá), a project funded by the Sistema General de Regalías de Colombia (General System of Royalties of Colombia), BPIN code: 2016000100037.

Acknowledgments

None stated by the authors.

References

1.Djulbegovic B, Guyatt GH. Progress in evidence-based medicine: a quarter century on. Lancet. 2017;390(10092):415-23. https://doi.org/gbq8x8.

2.Fearns N, Kelly J, Callaghan M, Graham K, Loudon K, Harbour R, et al. What do patients and the public know about clinical practice guidelines and what do they want from them? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:74. https://doi.org/mbxm.

3.Browman GP, Levine MN, Mohide EA, Hayward RS, Pritchard KI, Gafni A, et al. The practice guidelines development cycle: a conceptual tool for practice guidelines development and implementation. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(2):502-12. https://doi.org/mfzj.

4.Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, et al. Marcos GRADE de la evidencia a la decisión (EtD): un enfoque sistemático y transparente para tomar decisiones sanitarias bien informadas. 2: Guías de práctica clínica. Gac Sanit. 2018;32(2):167.e1-10.https://doi.org/gmd7nr.

5.Rosenfeld RM, Shiffman RN, Robertson P; Department of Otolaryngology State University of New York Downstate. Clinical Practice Guideline Development Manual, Third Edition: a quality-driven approach for translating evidence into action. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(1 Suppl):S1-55. https://doi.org/gmbcwf.

6.Carrasquilla G, Pulido A, De La Hoz A, Mieth K, Muñoz O, Guerrero R. Guía Metodológica para la elaboración de Guías de Práctica Clínica con Evaluación Económica en el Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud Colombiano. 2nd ed. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de la Protección Social; 2014.

7.Duarte A, Torres-Amaya A, Vélez C. Manual de Implementación de Guías de Práctica Clínica basadas en evidencia en Instituciones Prestadoras de Servicios de Salud en Colombia. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de la Protección Social; 2014.

8.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Developing NICE Guidelines: The Manual. London: NICE; 2015 [cited 2023 Nov 23]. Available from: http://bit.ly/48BhVUu.

9.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). SIGN 50: a guideline developer’s handbook . SIGN 50: a guideline developer’s handbook. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2019 [cited 2023 Nov 26]. Available from: https://bit.ly/41PySbs.

10.Atkins D, Eccles M, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Henry D, Hill S, et al. Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations I: critical appraisal of existing approaches The GRADE Working Group. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4(1):38. https://doi.org/dg67nj.

11.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ, et al. What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336(7651):995-8. https://doi.org/drtckp.

12.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(12):1308-11. https://doi.org/db6z8t.

13.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924-6. https://doi.org/dqmphq.

14.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383-94. https://doi.org/cdgpns.

15.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401-6. https://doi.org/d49b4h.

16.Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, editors. The GRADE Handbook. 2013 [cited 2023 Jul 5]. Available from: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html.

17.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia. Buscador de guías de práctica clínica. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social; 2015 [cited 2023 Jul 5]. Available from: https://gpc.minsalud.gov.co/gpc/SitePages/buscador_gpc.aspx.

18.Colombia, Ministerio de Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones. Plataforma Nacional de Datos Abiertos de Colombia. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones; [unknown date] [cited 2023 Jul 5]. Available from: https://www.datos.gov.co/.

19.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Centro Nacional de Investigación en Evidencia y Tecnologías en Salud (CINETS). Guía de práctica clínica del recién nacido sano. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2013.

20.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Centro Nacional de Investigación en Evidencia y Tecnologías en Salud (CINETS). Guía de práctica clínica del recién nacido prematuro. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2013.

21.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Centro Nacional de Investigación en Evidencia y Tecnologías en Salud (CINETS). Guía de práctica clínica del recién nacido con trastorno respiratorio. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2013.

22.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Centro Nacional de Investigación en Evidencia y Tecnologías en Salud (CINETS). Guía de práctica clínica Recién nacido: sepsis neonatal temprana. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2013.

23.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Centro Nacional de Investigación en Evidencia y Tecnologías en Salud (CINETS). Guía de práctica clínica del recién nacido con asfixia perinatal. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2013.

24.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Centro Nacional de Investigación en Evidencia y Tecnologías en Salud (CINETS). Guía de Práctica Clínica para el abordaje sindrómico del diagnóstico y tratamiento de los pacientes con infecciones de transmisión sexual y otras infecciones del tracto genital. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2013.

25.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Centro Nacional de Investigación en Evidencia y Tecnologías en Salud (CINETS). Guía de Práctica Clínica para la detección temprana, diagnóstico y tratamiento de la artritis idiopática juvenil. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2014.

26.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Centro Nacional de Investigación en Evidencia y Tecnologías en Salud (CINETS).Guía de Práctica Clínica para la detección temprana, diagnóstico y tratamiento de la artritis reumatoide. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2014.

27.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Centro Nacional de Investigación en Evidencia y Tecnologías en Salud (CINETS). Guía de práctica clínica para la prevención, detección temprana, diagnóstico, tratamiento y seguimiento de las dislipidemias en la población mayor de 18 años. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2014.

28.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Centro Nacional de Investigación en Evidencia y Tecnologías en Salud (CINETS). Guía de práctica clínica basada en la evidencia para la prevención, diagnóstico, tratamiento y seguimiento de la Enfermedad Pulmonar Obstructiva Crónica (EPOC) en población adulta. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2014.

29.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Fundación Meditech. Guía de Práctica Clínica Para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de pacientes adultos con trauma craneoencefálico severo. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2014.

30.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Fundación Universitaria de Ciencias de la Salud (FUCS), Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INC), Instituto Nacional de Dermatología Centro Dermatológico Federico Lleras Acosta. Guía de Práctica Clínica con evaluación económica para la prevención, diagnóstico, tratamiento y seguimiento del cáncer de piel no melanoma: queratosis actínica. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2014.

31.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Fundación Universitaria de Ciencias de la Salud (FUCS), Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INC), Instituto Nacional de Dermatología Centro Dermatológico Federico Lleras Acosta. Guía de Práctica Clínica con evaluación económica para la prevención, diagnóstico, tratamiento y seguimiento del cáncer de piel no melanoma: carcinoma escamocelular de piel. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2014.

32.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Fundación Universitaria de Ciencias de la Salud (FUCS), Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INC), Instituto Nacional de Dermatología Centro Dermatológico Federico Lleras Acosta. Guía de Práctica Clínica con evaluación económica para la prevención, diagnóstico, tratamiento y seguimiento del cáncer de piel no melanoma: carcinoma basocelular. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2014.

33.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INC). Guía de Práctica Clínica para la detección temprana, diagnóstico, estadifcación y tratamiento del cáncer de pulmón. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2014.

34.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Centro Nacional de Investigación en Evidencia y Tecnologías en Salud (CINETS), Universidad de Antioquia. Guía de práctica clínica para la detección temprana, atención integral, seguimiento y rehabilitación de pacientes con diagnóstico de distrofia muscular. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2014.

35.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Asociación Colombiana de Neumología Pediátrica. Guía de Práctica Clínica para la prevención, diagnóstico, tratamiento y rehabilitación de Fibrosis Quística. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2014.

36.Fondo de Población de las Naciones Unidas (UNFPA), Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Guía de práctica clínica (GPC) basada en la evidencia para la atención integral de la sífilis gestacional y congénita. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - UNFPA; 2014.

37.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Universidad de Antioquia. Guía de práctica clínica para la evaluación del riesgo y manejo inicial de la neumonía en niños y niñas menores de 5 años y bronquiolitis en niños y niñas menores de 2 años. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social; 2014.

38.Organización Internacional para las Migraciones, Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS). Guía de práctica clínica para la identificación y el manejo clínico de la tos ferina en menores de 18 años de edad Actualización 204. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social; 2014.

39.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología. Guía de Práctica Clínica para la detección y manejo de lesiones precancerosas de cuello uterino. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social; 2014.

40.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología. Guía de Práctica Clínica para el manejo del cáncer de cuello uterino invasivo. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social; 2014.

41.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Universidad de Antioquia, et al. Guía de práctica clínica para el diagnóstico, tratamiento y seguimiento de la diabetes Gestacional. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2016.

42.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Universidad de Antioquia, et al. Guía de práctica clínica para el diagnóstico, tratamiento y seguimiento de los pacientes mayores de 15 años con diabetes mellitus tipo 1. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2015.

43.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Universidad de Antioquia, et al. Guía de práctica clínica para el diagnóstico, tratamiento y seguimiento de la diabetes mellitus tipo 2 en la población mayor de 18 años. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2016.

44.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Guía de Práctica Clínica para el diagnóstico, tratamiento y rehabilitación de los accidentes cerebrovasculares isquémicos en población mayor de 18 años. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2015.

45.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Universidad de Antioquia, et al. Guía de Práctica Clínica para el diagnóstico y tratamiento preoperatorio, intraoperatorio y postoperatorio de la persona amputada, la prescripción de la prótesis y la rehabilitación integral. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2015.

46.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Fundación Universitaria de Ciencias de la Salud (FUCS), Asociación Colombiana de Oftamología (ACOPE), Sociedad Colombia de Pediatría, et al. Guía de Práctica Clínica para la detección temprana, el diagnóstico, el tratamiento y el seguimiento de los defectos refractivos en menores de 18 años. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2016.

47.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Fundación Universitaria de Ciencias de la Salud (FUCS), Asociación Colombiana de Oftamología (ACOPE), Sociedad Colombia de Pediatría, et al. Guía de Práctica Clínica para la prevención, la detección temprana, el diagnóstico, el tratamiento y el seguimiento de la ambliopía en menores de 18 años. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2016.

48.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Fundación Universitaria de Ciencias de la Salud (FUCS), Asociación Colombiana de Nutrición Clínica, Asociación Colombiana de Endocrinología, et al. Guía de Práctica Clínica para la prevención, diagnóstico y tratamiento del sobrepeso y la obesidad en adultos. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2016.

49.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Universidad de Antioquia, et al. Guía de Práctica Clínica para la prevención, diagnóstico, tratamiento y rehabilitación de la falla cardiaca en población mayor de 18 años, clasificación B, C y D. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2016.

50.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Centro Nacional de Investigación en Evidencia y Tecnologías en Salud (CINETS). Guía de práctica clínica para El Síndrome Coronario Agudo. 3rd ed. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2017.

51.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Instituto Nacional de Cancerología. Guía de práctica clínica para la detección, tratamiento y seguimiento de linfomas Hodgkin y No Hodgkin en población mayor de 18 años. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - Colciencias; 2017.

52.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (Colciencias), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS), Instituto Nacional de Cancerología. Guía de Práctica Clínica para la detección, tratamiento y seguimiento de leucemias linfoblástica y mieloide en población mayor de 18 años. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, editor. Bogotá: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social; 2017.

53.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Empresa Nacional Promotora del Desarrollo Territorial (ENTerritorio), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS). Guía de Práctica Clínica (GPC) basada en la evidencia científica para la atención de la infección por VIH/SIDA en niñas, niños y adolescentes. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - ENTerritorio - IETS; 2021.

54.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Empresa Nacional Promotora del Desarrollo Territorial (ENTerritorio), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS). Guía de Práctica Clínica (GPC) basada en la evidencia científica para la atención de la infección por VIH/SIDA en personas adultas, gestantes y adolescentes. Bogotá D.C.: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - ENTerritorio - IETS; 2021.

55.Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Pottie K, Meerpohl JJ, Coello PA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation—determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):726-35. https://doi.org/f43b7d.

56.Cabrera PA, Pardo R. Review of evidence based clinical practice guidelines developed in Latin America and Caribbean during the last decade: an analysis of the methods for grading quality of evidence and topic prioritization. Global Health. 2019;15(1):14. https://doi.org/mb49.

57.Delgado-Noguera MF, Merchán-Galvis ÁM, Mera-Mamián AY, Muñoz-Manquillo DM, Calvache JA. Evaluación de la calidad metodológica de las Guías Colombianas de Práctica Clínica en Pediatría. Pediatr. 2015;48(4):87-93. https://doi.org/bwnn.

58.Alexander PE, Bero L, Montori VM, Brito JP, Stoltzfus R, Djulbegovic B, et al. World Health Organization recommendations are often strong based on low confidence in effect estimates. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(6):629-34. https://doi.org/f52468.

59.Yao L, Guyatt GH, Djulbegovic B. Can we trust strong recommendations based on low quality evidence? BMJ. 2021;375:n2833. https://doi.org/gqmjn8.

60.Qumseya B, Goddard A, Qumseya A, Estores D, Draganov P V., Forsmark C. Barriers to Clinical Practice Guideline Implementation Among Physicians: A Physician Survey. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:7591-8. https://doi.org/mb5b.

61.Suárez-Obando F, Gómez-Restrepo C. Patrones de acceso al Portal Web Guías de Práctica Clínica en Colombia. Rev. Fac. Med. 2016;64(4):687-94. https://doi.org/mb5c.

Ángela Manuela Balcázar-Muñoz1

Ángela Manuela Balcázar-Muñoz1 Juan Carlos Villar1

Juan Carlos Villar1 Felipe Angel Rodríguez1

Felipe Angel Rodríguez1 Daniel Queremel-Milani1

Daniel Queremel-Milani1