"Gratitude is Thanking Someone, and Happiness Is Showing It": A Qualitative Study of Colombian Children's Perspectives on Gratitude

“La Gratitud es Agradecer a Alguien, y la Felicidad es Mostrarlo”: Un Estudio Cualitativo de las Perspectivas de Niños Colombianos Sobre la Gratitud

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/rcp.v32n2.100130Keywords:

Benefactors, children's emotions, family, gender, gratitude expression, type of schooling (en)benefactores, emociones infantiles, expresión de gratitud, familia, género, tipo de escolaridad (es)

As a character strength, gratitude is linked with positive emotions and can potentially provide many benefits to children and adolescents. Yet little is known about how and why children typically experience gratitude, and how to promote its development. We conducted 10 focus groups and written exercises with 38 Colombian fifth-graders (19 girls and 19 boys), from one public school and two private schools, to explore different components of their gratitude experiences, namely, the benefactors, benefits, feelings, and behavioral expressions associated with gratitude, using a theoretical/ deductive thematic analysis. There were many commonalities in the themes of the gratitude elements found in both girls’ and boys’ answers, and in both public and private schools. One element of gratitude not anticipated in the analysis was the degree of effort that children saw benefactors (particularly family members) investing in them. These findings can be used to inform educational interventions, making them more relevant to children in Colombian and other Latin American contexts.

La gratitud como fortaleza del carácter está relacionada con las emociones positivas y potencialmente puede brindar muchos beneficios a los niños y adolescentes. Sin embargo, se sabe poco sobre cómo y por qué los niños suelen experimentar la gratitud y cómo promover su desarrollo. Realizamos 10 grupos focales y ejercicios escritos con 38 estudiantes colombianos de quinto grado (19 niñas y 19 niños), de una escuela pública y dos escuelas privadas, para explorar diferentes componentes de sus experiencias de gratitud: los benefactores, los beneficios, los sentimientos y las expresiones comportamentales asociadas a la gratitud, mediante un análisis temático teórico/deductivo. Hubo muchos puntos en común en los temas de los elementos de gratitud que se encuentran en las respuestas de las niñas y los niños, y en las escuelas públicas y privadas. Un elemento de gratitud que no se anticipó en el análisis fue el grado de esfuerzo que los niños vieron que los benefactores (particularmente los miembros de la familia) invertían en ellos. Estos hallazgos pueden usarse para informar intervenciones educativas, haciéndolas más relevantes para los niños en contextos urbanos de Colombia y otros contextos latinoamericanos.

Recibido: 20 de diciembre de 2021; Aceptado: 31 de enero de 2023

Abstract

As a character strength, gratitude is linked with positive emotions and can potentially provide many benefits to children and adolescents. Yet little is known about how and why children typically experience gratitude, and how to promote its development. We conducted 10 focus groups and written exercises with 38 Colombian fifth-graders (19 girls and 19 boys), from one public school and two private schools, to explore different components of their gratitude experiences, namely, the benefactors, benefits, feelings, and behavioral expressions associated with gratitude, using a theoretical/deductive thematic analysis. There were many commonalities in the themes of the gratitude elements found in both girls’ and boys’ answers, and in both public and private schools. One element of gratitude not anticipated in the analysis was the degree of effort that children saw benefactors (particularly family members) investing in them. These findings can be used to inform educational interventions, making them more relevant to children in Colombian and other Latin American contexts.

Keywords

Benefactors, children’s emotions, family, gender, gratitude expression, type of schooling.Resumen

La gratitud como fortaleza del carácter está relacionada con las emociones positivas y potencialmente puede brindar muchos beneficios a los niños y adolescentes. Sin embargo, se sabe poco sobre cómo y por qué los niños suelen experimentar la gratitud y cómo promover su desarrollo. Realizamos 10 grupos focales y ejercicios escritos con 38 estudiantes colombianos de quinto grado (19 niñas y 19 niños), de una escuela pública y dos escuelas privadas, para explorar diferentes componentes de sus experiencias de gratitud: los benefactores, los beneficios, los sentimientos y las expresiones comportamentales asociadas a la gratitud, mediante un análisis temático teórico/deductivo. Hubo muchos puntos en común en los temas de los elementos de gratitud que se encuentran en las respuestas de las niñas y los niños, y en las escuelas públicas y privadas. Un elemento de gratitud que no se anticipó en el análisis fue el grado de esfuerzo que los niños vieron que los benefactores (particularmente los miembros de la familia) invertían en ellos. Estos hallazgos pueden usarse para informar intervenciones educativas, haciéndolas más relevantes para los niños en contextos urbanos de Colombia y otros contextos latinoamericanos.

Palabras clave

benefactores, emociones infantiles, expresión de gratitud, familia, género, tipo de escolaridad.GRATITUDE IN human beings is a complex concept that can be theorized in multiple ways, including as an emotional state, a moral virtue, and a character strength. According to Watkins (2014), gratitude as a positive emotion is experienced when a beneficiary recognizes that something good has happened to them and that another person (the benefactor) is largely responsible for providing this benefit. This definition highlights the social character of gratitude, which promotes positive relationships by motivating individuals who experience it to reciprocate benefits to people who provided them (Algoe et al., 2008). The social and moral functions of gratitude were explored by McCullough et al. (2001), who integrated several theories that conceptualized gratitude as a moral emotion. They argued that since feeling gratitude stimulates behaviors in favor of a benefactor’s wellbeing, it helps us build societies based on the common good. McCullough & Tsang (2004) extended this theory by arguing that gratitude fulfils the function of a “moral barometer” and depends on social-cognitive processing. That is, people are more likely to experience gratitude when they receive a benefit highly valued by them, when they recognize that the benefactor has invested a high effort or cost to provide that benefit, and when they notice that the effort invested by the benefactor was intentional rather than accidental.

In addition to being experienced as a transitory moral emotion based on social cognitive skills, the moral aspect of gratitude has been viewed in positive psychology as a lasting character strength that promotes various virtues (Peterson and Seligman, 2004). These authors linked gratitude with the virtue of “transcendence,” which they related to seeking meaning in life and promoting holistic connections with the universe. More recently, the relationship of gratitude to the concept of virtue has been further elaborated by several other researchers. For example, Merçon-Vargas et al. (2018) proposed a definition of gratitude as a “moral virtue” including, in addition to the beneficiary, a benefit and a benefactor, the positive feelings related to the benefactor’s action, and the desire to freely return the benefit received to the benefactor. Hence, the virtue of gratitude encourages positive emotions by raising our consciousness of a benefit that has been granted to us (McCullough et al., 2001; Ruch et al., 2021).

A consequence of the conceptualization of gratitude as a character strength linked to the promotion of virtues is the recognition that such strengths can (and should) be cultivated during childhood, adolescence, and youth, leading to interest in the development of educational interventions for this purpose. Research has shown positive effects of gratitude on young people’s wellbeing. For example, Froh et al. (2011) observed that expressing gratitude improved the social interactions of US adolescents, their emotional functioning, and wellbeing. Gratitude has also been shown to promote prosocial behavior and generosity in US undergraduates and high school students (Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006; Bono et al., 2019); the latter study also found that it was important for the maintenance and strengthening of close social relationships. Other authors linked higher levels of gratitude with better academic and psychosocial adjustment, and hence with the emotional wellbeing of school-aged children (Furlong et al., 2013; Tian et al., 2015). Likewise, in general, it has been shown that social skills training in fifth graders is maintained over time and has an impact on the reduction of behavioral problems and improvement in academic performance (De Souza et al., 2022).

Given these demonstrated benefits of gratitude for young people, the developmental prerequisites for experiencing gratitude in childhood have been an important puzzle for researchers to solve. As early as the 1960s, Tesser et al. (1968) indicated that gratitude depends on three specific aspects of the beneficiary’s perceptions: the perceived intentions of the benefactor, the perceived costs accruing to the benefactor, and the perceived value to the beneficiary. Poelker & Kuebli (2014) examined the development of US elementary schoolchildren’s abilities to appreciate the intentions and efforts of benefactors in giving them a desirable or an undesirable gift. Their results indicated that fourth and fifth graders could recognize a benefactor’s effort independently of the value they placed on the benefit received. On the other hand, while children’s gratitude may still be influenced by a representation of the costs as perceived by the beneficiary, Australian and British adolescents tended to accurately identify the benefactor’s intentions in providing a benefit (Morgan & Gulliford, 2017). In a longitudinal study with Chinese elementary schoolchildren, Wu et al. (2020) found an upward trajectory in the development of gratitude: that is, older children were better able to recognize good acts that other people performed for them and to value such acts as positive influences in their lives.

Another important development takes place in the ability to recognize the value of benefits received. Tudge et al. (2015) review the tendency in younger children (7-10 years old) to focus on more immediate material benefits and to express their appreciation through tangible objects. However, as they mature into adolescence (11-14 years old), children display a greater capacity to consider the context of the benefactor’s situation when expressing their gratitude for benefits of low material value. Along these lines, several studies carried out in Latin America have reported differences in the type of benefits that children from different sociocultural contexts identify, in Brazil (Freitas et al., 2011; Palhares et al., 2018), Argentina (Cuello & Oros, 2016; Oros et al., 2015), and Guatemala (Poelker & Gibbons, 2018). A common finding was that participants from low-income families tended to be grateful for more material benefits than their peers from better-off families, who expressed gratitude for more abstract benefits, such as feelings or social connections. This represents a potential target for educational interventions, as in that of Froh et al. (2011), who showed that promoting gratitude in an educational setting decreased the levels of materialism in North American adolescents.

Increasing understanding of the emotions associated with gratitude has been another focus for interventions in young people. Such emotions, including joy, pride, enjoyment, and hope, have also been linked with educational achievement in Filipino children (Magno & Orillosa, 2012). According to these authors, a corollary of the links with positive emotions is that when young people experience more gratitude, they tend to feel lower levels of negative emotions such as anger, grief, or boredom. Similarly, Poelker et al. (2019) reported that promoting perspective-taking in Guatemalan children increased their feelings of gratitude and decreased feelings of envy.

Additionally, emotion comprehension can be linked to gratitude, in the sense that children develop an ability to recognize that expressing gratitude can foster positive emotions in their benefactors and others. Freitas et al. (2011) established that expressions of gratitude differ substantially according to age (see also Freitas et al., 2021; Oros et al., 2015; Palhares et al., 2018). Children first express gratitude verbally (saying thank-you), a form of expression that was present across the entire age range of Freitas et al.’s (2011) study with US children aged 7 to 14 years. On the other hand, concrete expressions of gratitude (giving a gift of one’s own preference to a benefactor) occurred more often in 8-year-olds than in younger children. Likewise, from the age of 12, as they got better at understanding a benefactor’s point of view, children began to express gratitude in connective ways, which implied being useful and kind to someone who helped them or showed generosity. Finalistic expression of gratitude (which means trying to improve permanently as a person in response to a benefactor’s good deed) did not appear until adolescence.

Research on gratitude in young people indicates that both the expression and the experience of gratitude can vary according to gender, but not always in systematic ways. In Argentina, Oros et al. (2015) encountered differences in the reasons for which middle-income girls and boys experienced gratitude. Boys felt more gratitude for material goods and prosocial behavior (favors and help given), while girls experienced it more for friendship, school, and affection. These differences were not found between girls and boys in more vulnerable socioeconomic conditions. Guse et al. (2019) found that adolescent South African girls experienced gratitude more frequently than boys, and showed higher levels of satisfaction with school, friends, and self. Froh et al. (2009) likewise showed that 11–13-year-old girls in the US tended to report slightly more gratitude than boys. In line with these results, Tian et al. (2015) found that 4th-to-6th-grade Chinese girls reported significantly greater gratitude than boys. On the other hand, Freitas et al. (2011) did not identify gender differences in 7–14-year-old Brazilian boys’ and girls’ expressions of gratitude. It is also worth noting that many of the above authors who did find gender differences explicitly recognized that their results were exploratory and inconclusive.

As this literature review has shown, there is an academic consensus that gratitude is a character strength whose development can bring about many positive effects in young people’s lives. However, there is still much uncertainty on how and why experiences of gratefulness vary between individuals and cultural contexts. The current study addresses this uncertainty by defining gratitude as a character strength marked by certain necessary elements, including both a benefit (an object, favor or experience positively valued by a person) and a benefactor (the person or entity who provides the benefit). To gain a greater understanding of Colombian children’s experience of these different elements of gratitude, our study was guided by the following research questions:

RQ1. To whom are Colombian girls and boys grateful?

RQ2. For what kinds of benefits do they experience gratitude?

RQ3. Which emotions do they associate with experiences of gratitude?

RQ4. How do they express gratitude?

RQ5. What are the particularities and commonalities in gratitude experiences by gender and socioeconomic conditions?

Answering these questions can help identify differences and similarities in how the elements of gratitude are understood and characterized in preadolescence, enabling us to design culturally and individually sensitive interventions that can harness the power of gratitude to enhance children’s positive social development. We addressed our research questions through a deductive thematic qualitative analysis of focus group discussions between fifth-grade children at public and private schools in Bogotá, Colombia. Fifth-grade children were targeted because this age group (around 10-12 years) stands on the cusp of important social and emotional changes between childhood and adolescence (Ingram, 2019), making them, in theory, particularly receptive to interventions that can enhance their social and emotional development in positive ways. In Colombia, fifth grade is also the last grade of elementary education before the transition to secondary education, which confronts children with new situations and academic and social challenges that will require the use of various socio-emotional skills. On the one hand, using focus groups, we hoped to identify discussion elements of a shared culture surrounding gratitude practices that could be used to create interventions that would have a broad appeal for many Colombian children, as well as points of disagreement on the nature of gratitude. On the other hand, the use of “gratitude books” (described below) served to concretize and particularize individual children’s gratitude experiences. The results of the focus group and gratitude book analysis helped inform the design and evaluation of an educational program to strengthen and promote gratitude in school contexts, a process that will be reported in later publications.

Method

Participants

The sample comprised 38 fifth-grade students (19 girls and 19 boys), aged 9-14 years (M = 10.53, SD = 0.91), from two private schools and one public school in inner Bogotá, Colombia. Of these, 32 participants were Colombian, 2 Venezuelan and 1 from the USA, while nationality information was not provided for the remaining 3 participants. The public school provides education for families of low socioeconomic status, while the two private schools are mainly attended by students of intermediate socioeconomic status.

Procedure

Data was collected in two sessions in May 2019. In the first session, that lasted about half an hour, children were introduced to the concept of gratitude. The research team gave the participants a notebook called The Gratitude Book and asked them to draw people, things, places, and moments that made them feel grateful, and record their reasons for feeling gratitude in these contexts. Gratitude books were given to all members of the classes in which we worked and were filled in as part of their normal class activities. (Further analysis of all the children’s books, rather than only those belonging to the subset of children who participated in the focus groups, will be the subject of a future publication.)

In the second session, focus groups with 3-6 children each, lasting 30-40 minutes, were implemented in each school, with a subset of participants chosen by their class teachers as likely to give rich responses. Ten focus groups were carried out: four in private schools (two with boys and two with girls) and six in the public school (three with boys and three with girls, one separately for each gender in each campus of the school). These were conducted by two teams of 2-3 principal investigators (PIs) and research assistants (RAs; an all-female team for the girls’ groups and an all-male team for the boys’). The PIs were mainly responsible for delivering and following up on the questions, while the RAs helped maintain all the children’s attention and recorded their answers.

At the start of each focus group, participants were given a few minutes to review their own Gratitude Book, to remind them of what they had recorded in it. The conversation script followed in all focus groups included the following issues to be discussed:

-

Someone whom children had named in their Gratitude Book, what made them feel grateful towards them, and why.

-

An experience of gratitude described in the book, including to whom they felt grateful in the situation, and what they were thinking and feeling at the time.

-

Someone whom the participant could think of at that moment, to whom they felt grateful but had not included in the book.

-

How they typically expressed gratitude to the people they had named.

All focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed by one of four undergraduate RAs. In addition to the transcripts of the 10 focus group discussions, 22 of the focus group participants gave permission for their gratitude books to be included in the study, for a total of 32 items forming the data set on which the analysis was performed to answer the five research questions. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad de los Andes, Colombia. All parents or guardians signed a consent form authorizing the participation of their children, the recording of the sessions, and the use of the information collected for research purposes.

Analysis

The transcripts and gratitude books were analyzed using NVivo 12. A theoretical-deductive thematic analysis was used to identify themes across the data set (Boyatzis, 1998 ; Braun & Clarke, 2006). Four analytical categories (benefactors, benefits, feelings associated with gratitude, and expressions of gratitude) were previously established based on the theoretical framework of gratitude elements that guided the research questions. Analysis was conducted independently by two RAs (postdoctoral assistants who joined the project after data was collected) in three moments of analysis. In the first moment the RAs reviewed the 32 items included in the analysis to familiarize themselves with the data, since they had not participated in data collection. In the second moment, initial codes were generated with three one-to-one discussions between RAs, to reach consensus on coding (Boyatzis, 1998). In a third moment, three meetings were held with a PI, who had participated in data collection, to reach consensus on the themes.

The second analytical moment (the generation of initial codes) consisted of three rounds. In the first round of analysis, the transcripts of the public school’s focus groups for both girls and boys were independently coded by the two RAs. In this round, the main codes were identified for each of the four pre-established theoretical categories of gratitude. Later, there was a meeting to discuss the coding of the material and reach consensus on the content and definition of the codes identified. In this first round, the percentage of agreement was 93.3% across 393 elements. In the second round, the researchers independently analyzed the private schools’ focus groups for both girls and boys, and met again to discuss the coding and adjust the codes identified. In this round, the proportion of agreement was 99.2% across a further 217 elements. In the third and final round of analysis, the researchers independently analyzed the content of all the gratitude books and met to discuss the coding and readjust the codes with the additional information provided by the books. In this round, the proportion of agreement was 99.7% across a further 823 additional elements, for a total of 1433 elements spread over 32 primary sources. In this third meeting round, the first proposal for themes within the pre-established theoretical scheme of gratitude was discussed with the PI. All codes were considered regardless of their frequency, with the intention of capturing the presence of the wider spectrum of issues mentioned by the children regarding the elements of gratitude that could be identified in the data. Two subsequent meetings were held to review and define the themes based on the theoretical framework until consensus was reached on the identification of the themes, whereupon NVivo 12’s coding outputs were used to build the thematic tree.

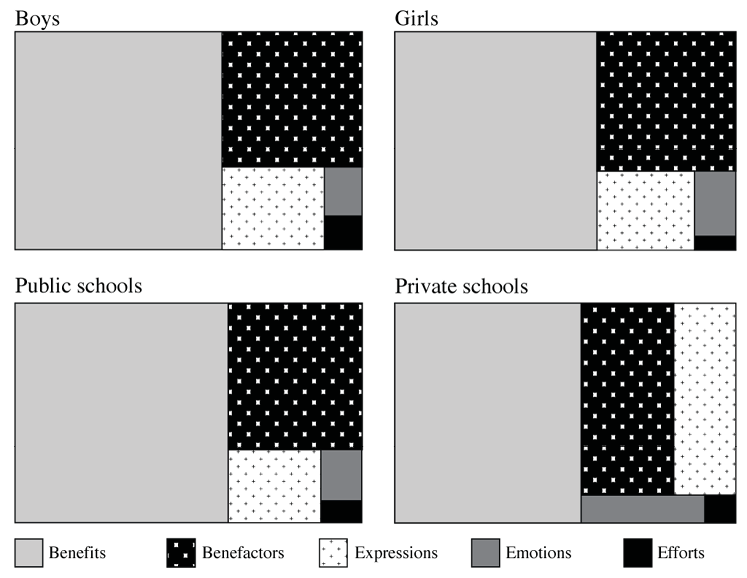

Once the themes had been defined, two types of differences were explored to identify possible particularities and commonalities by creating cases with the NVivo tool for each condition and comparing them as follows: 1) girls and boys, to identify the characteristics of the coded material disaggregated by gender; 2) public and private schools, to identify the characteristics of the material disaggregated by a proxy for socioeconomic status. Then, using the data reporting tools of NVivo 12, diagrams were constructed to represent commonalities and particularities in the distribution of the extracts in the dataset by gender and type of school. Finally, the results of all these analyses and the process of producing the report were discussed and prepared jointly with the entire research team (including all the authors of the current article).

Results

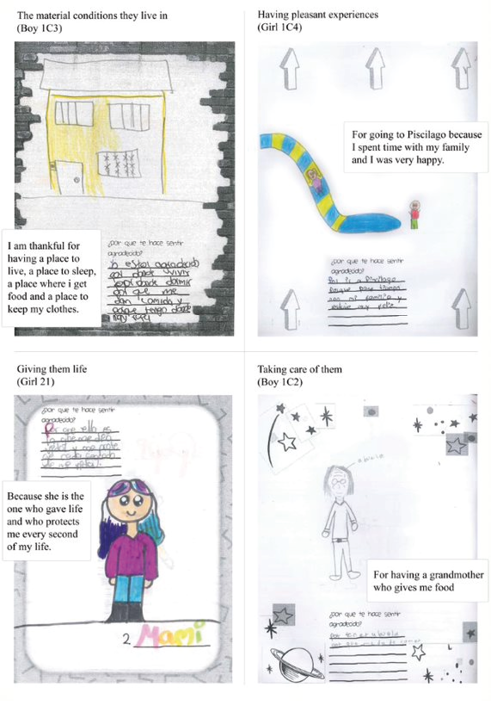

We first report the various themes and subthemes belonging to the pre-established, theoretically derived elements of our gratitude analysis: benefactors, benefits, feelings, and expressions of gratitude. During analysis, a fifth category not included in the pre-designed list was identified: the effort that children recognized in their benefactors. In parentheses we give the percentage of extracts for each element that belonged to each theme, followed by examples of the most prevalent themes. Examples of textual extracts from the focus group discussions are presented in tables, while illustrations and writing from the participants’ gratitude books for the most salient themes relating to the Benefits element are shown in Figure 1. Finally, we present the results of the comparative analysis by gender and type of school.

Benefactors to Whom Children Were Grateful

For the analytical element of benefactors, two themes were identified: interpersonal (six sub-themes) and personifications (three sub-themes), for a total of nine types of identified benefactors. In the interpersonal theme, members of the nuclear family predominated (48.8% of all benefactors mentioned). Different nuclear family members were mentioned: mother, siblings, and father or stepfather. This theme also included members of the extended family (17.1%), namely grandparents, cousins, and aunts and uncles, as well as deceased family members (1.5%). At the interpersonal level outside the family, some participants identified peers as benefactors (7.5%), especially those with whom they interacted in the school context, including both personal friends and fellow students in general. They also recognized their teachers (7.5%). Children only occasionally recognized other adults who were part of their community as a source of benefits (2.09%): specifically, service providers such as shopkeepers, security personnel, and health workers.

The second theme corresponded to children’s personification of animals, institutions, and abstract entities as sources of benefits (and therefore targets of gratitude). Subthemes included God, life, and nature (15.33%); as well as the institutions that children belonged to (4.19%), such as the church, community organizations and their school; and their pets (3.89%). See Table 1 for example quotes from some of the subthemes.

Table 1:

Example Quotations for Salient Themes of Benefactors

Theme: Interpersonal

Example extracts

Nuclear family

“I

am grateful to my mother because she supports me and

also makes my life happy, and she gave me my sisters,

whom I play with and have fun.” (GF1Aa)

Peers

Researcher:

“A, you said ‘friends’: what makes you feel grateful

towards your friends?”Boy A: “Because they accompany me

at recess, because I play games with them.”Boy B: “They

are always with us, so we don’t feel alone.” (GF1Ao)

Teachers

Boy

C: “My teachers.”Researcher: “C, why would you feel

grateful to the teachers?”Children: “Because they teach

us!” [Everyone laughs]Researcher: “But why is it good to

be taught?” ...C: “They teach us things we must learn to

get ahead, to be someone in life.”D: “To be a

professional.” (GF1Ao).

Theme: Personification

God, life and nature

Boy:

“Thanks to life we can be where we are, at school and

studying, we can continue with our life, we can grow

old, we can have fun.” (GF1Ca)

Benefits for Which Children Experienced Gratitude

The element of benefits showed the most richness in terms of the different themes (13) that were identified in children’s gratitude experiences. Thirteen different reasons for which children felt gratitude were identified. The most common themes included material living conditions (24.45%)—having a house, a room to sleep in, and food to eat; the opportunity to have pleasant experiences (21.26%) such as going for a walk, going on a trip, or celebrating special moments; and receiving life (10.68%) associated with their mother and father, God, or health workers. Children also recognized as a benefit other people’s caring behaviors towards them (9.80%), e.g., taking them to the doctor or cooking for them (see Figure 1 for examples of these four benefits).

Figure 1

:

Examples of Drawings for Some Benefit Themes

Children also mentioned the benefit of being taught something (7.71%), whether this was academic, playful (such as new video games) or life lessons. This benefit was particularly associated with teachers, family, and friends. Other benefits included behaviors by which affection was expressed to children (7.27%), through loving words and physical contact such as hugs; certain gifts that they received (7.16%), including clothes, toys, or musical instruments; behaviors by which people expressed solidarity (5.40%), by supporting them in difficult times or giving them advice; and opportunities for personal growth (3.41%), through support in the development of academic or recreational activities. Consistent with the personification of abstract benefactors described above, a few participants also expressed gratitude for what nature provided them (2.53%), including water, plants, and oxygen. One boy was grateful for God’s compassion in resolving the pain of a loved one who had died. A girl was grateful for the job opportunities her parents had thanks to wider family support, while a boy was grateful because an unpleasant experience no longer occurred (a classmate who had been bothering him was no longer at that school).

Feelings that Children Associated with Gratitude Experiences

Children identified various feelings associated with their gratitude experiences. Five feelings were coded in the focus groups: joy/happiness (73.33%), a general experience of feeling good (10%), nostalgia (6.67%), desire to return a benefit (6.67%), and love (3.33%). These feelings were divided into two themes: feelings experienced when receiving a benefit, and feelings experienced when expressing gratitude (see Table 2).

Table 2:

Example Extracts for the two Themes of Feelings

Element: Feelings

Theme

Example extracts

Feelings when receiving a benefit

Love

and joy/happiness

Girl:

“I am grateful to my mother because she gave me life and

because she was the one who helped me all this

time...”Researcher: “When you feel that gratitude what

do you feel in your body?”Girl: “Happiness.”Researcher:

“Do you feel anything else?” Girl: “Nerves… and now...

love!” (GF1Ba)

Emotions when expressing gratitude.

Joy/happiness

Girl:

“Gratitude is thanking someone, and happiness is showing

it.” (GF3a)

Children’s Expressions of Gratitude

For this gratitude element, different expressions were coded with pre-established themes according to the theory of increasing complexity of types of gratitude expression, using the classification of Freitas et al. (2021) as a guide. In all groups, four forms of expression of gratitude were identified (see Table 3): concrete (46.46%), verbal (27.78%), connective (17.17%), and finalistic (8.59%).

Table 3:

Example Extracts for Children’s Gratitude Expressions

Theme: Types of gratitude expression

Example extracts

Concrete

Boy

1: “Well, with mothers, for example, I gave her a rose.

She gave me a kiss, gave me a hug, and was happy.”Boy 2:

“I made her a little box and wrote her a letter, and she

was happy and hugged me.” (GF1Bo)

Verbal

Researcher:

“What did you do when they gave you the cellphone? Who

gave it to you: your mommy?”Girl: “I said thank you and

hugged her.” (GF1Aa)

Connective

Boy:

“Well... I give [them] a hug… I also give a thousand

thankyous and then I can do [them] a favor too.” (GF3o)

Finalistic

Girl:

“To my mother. I help her cleaning the house and the

kitchen... I think she will be grateful for having a

daughter who helps her.” (GF1Aa)

Efforts that Children Identified in Benefactors

Effort was an element of gratitude not included in the initial theoretical structure of the analysis. Nevertheless, it was found in extracts from both girls and boys, from both public and private schools. Children were not directly asked about this aspect of gratitude in the focus groups; rather, it was identified in the analysis when children explained the reasons for being grateful for a particular benefit. Five themes were identified in this analytical element, the first being the recognition of the benefactor’s hard work (47,62%), like valuing the energy demanded to make things happen on a daily basis or the struggle they went through to care for the beneficiary. A second theme was the effort the benefactor needed to understand the beneficiary’s needs (23.18%), like being patient, or putting themselves in the beneficiary’s shoes. Time investment by the benefactor was another theme identified (19.05%), including personal time or the time needed to do something. The use of benefactor’s financial resources (4.76%) was mentioned by one boy and putting the beneficiary’s needs above the benefactor’s (4.76%) was also mentioned by another one. See Table 4 for examples.

Table 4:

Example Quotations for the Effort Associated with

Gratitude-Related Situations

Element: Effort

Example quotations

Hard

work by the benefactor

Boy:

“Even if you don’t have money, at least write a letter

to your mother saying thank you... because mothers make

a lot of effort, so you don’t see that your mother is

struggling for you, working to at least give you food,

have bread on the table. She is working for us to go

far.” (GF1Co)

Time

invested by the benefactor

Girl:

“I thank her every day, when my mother hugs me and has

time for me, because she also has time for my sisters

and work, for so many things...” (GF1Ca)

Particularities and Commonalities by Gender and by Type of School

As indicated in the Methods section, once all the material had been processed, four different contexts were analyzed: girls, boys, public school, and private school. The aim was to identify the presence or absence of the themes within the gratitude element in the aforementioned contexts. To this end, coding tables were created for the percentages of themes mentioned across the different contexts (see Table 5).

Table 5:

Proportions of extracts belonging to each theme in every

element, by gender and SES

Element

Theme/Code

1

Gender

SES

Girls

(%)

Boys

(%)

Private

(%)

Public

(%)

Benefactors

Specific

person

88.8

92.8

98.8

87.6

Personification

11.2

7.24

1.18

12.4

Benefits

The

material living conditions un which they live

15.7

26.7

13.0

24.9

The

opportunity to have pleasant experiences

26.0

17.5

23.8

20.6

Receiving

life

7.05

8.08

3.24

9.26

Recognition

of the behaviors that other people carried out to take

care of them

8.33

10.9

10.8

9.26

The

benefit of being taught something

7.05

6.13

9.73

5.35

Behaviors

by which affection was expressed to children

8.33

6.13

8.65

6.58

Gifts

that they received

9.62

5.85

6.49

8.02

Behaviors

by which people expressed solidarity

13.8

10.6

20.0

9.05

Opportunities

for personal growth

1.60

4.74

3.78

3.09

What

nature provided them

2.24

2.79

0.54

3.29

God’s

compassion in resolving the pain of a loved one who had

died

0.00

0.28

0.00

0.21

The

job opportunities her parents had thanks to wider family

support

0.32

0.00

0.00

0.21

Unpleasant

experience no longer occurred

0.00

0.28

0.00

0.21

Feelings

Feelings

experienced when expressing gratitude

28.0

21.1

33.3

19.2

Feelings

experienced when receiving a benefit

72.0

79.0

66.7

80.8

Expressions1

Verbal

9.89

7.78

14.6

5.84

Concrete

80.8

85.6

77.1

86.7

Connective

4.40

2.59

4.86

2.60

Finalistic

4.40

2.59

4.86

2.60

Efforts

Recognition

of benefactor’s hard work

50.0

40.0

57.1

44.4

Benefactor

showing understanding of beneficiary

25.0

20.0

14.3

22.2

Time

investment by benefactor

25.0

20.0

14.3

22.2

Benefactor’s

use of financial resources

0.00

10.0

14.3

0.00

Putting

beneficiary’s needs above benefactor’s

0.00

10.0

0.00

11.1

This analysis yielded two results. Firstly, differences were found in the descriptions of the themes of the unanticipated element of effort between the contexts of girls and boys and private and public schools, due to the different types of effort identified. Secondly, across all 4 contexts (girls, boys, public education, and private education) the 5 elements of gratitude and 26 of the identified themes and subthemes were present. Specifically, in the analyzed material for the girls, 84.6% of the identified subthemes were present, while for the boys 96.2% were present. Grouped by type of educational institution, 96.2% of themes and subthemes were identified in public schools and 84.6% in private schools. In all contexts, a wide diversity of benefits identified by girls and boys was observed, along with an impressive variety in the people and beings recognized as benefactors. All forms of expressing gratitude (verbal, concrete, connective, and finalistic) were also present. Two elements of gratitude showed less variety of examples across contexts: emotions and efforts. As mentioned above, the only differences in the presence of extracts between cases were due to the types of effort mentioned and certain benefits that were only mentioned by a single child. As can be seen in Figure 2, the saturation distribution of each element of gratitude was remarkably similar in each context.

Figure 2

:

Saturation Distribution of Pre-established Gratitude

Elements

Indeed, the elements and themes of gratitude were present in all groups (both girls and boys, from both public and private schools) in rather similar ways. Moreover, the differences between groups were small and, in our analysis, were connected more to particularities of children’s lives than to general differences in gender or social class. For example, students from both public and private schools identified trips away from the city as a fun activity that made them feel grateful; the differences came in the types of places to which they travelled (to the coast by airplane, or to a nearby town by car or bus). Both girls and boys identified the nuclear family as a principal source of benefits. The differences came in the people who were mentioned as family members, relating to differences in the structure of each family. For example, there were several participants who mentioned living with a female head of household, others mentioned the stepfathers as a source of benefits, and still others being raised by their grandparents or living with their uncles or aunts, all of which are quite common forms of family structures in Colombia (Escobar, 2019).

By way of synthesis, Figure 3 illustrates the connections between all these elements of gratitude, for the examples of nuclear family members and teachers.

Figure 3

:

Examples of Elements Identified in Girls’ and Boys’

Gratitude Experiences in Public and Private Schools

Discussion

This study used focus groups to explore to whom and for what benefits Colombian children were grateful, along with the feelings and behaviors they associated with gratitude. A striking level of commonality occurred across all the elements of gratitude (benefactors, benefits, feelings, expressions, and effort) between all the groups. This is encouraging in terms of the potential of this research to inform an educational intervention based on gratitude that could improve the experiences of diverse groups of children across Colombia. Some diversity remained in the verbal responses of the participants, particularly in the element of effort, which may have been influenced by the separation of both girls and boys, and public and private schools, in the composition of the focus groups. This makes the commonalities in children’s responses even more remarkable, leading us to suspect that it may reflect certain characteristics of the Colombian social and cultural environments to which the children belonged. At the same time, a few subtle differences in gender and school type (in terms of recognition of material benefits and benefactor’s efforts, for example), as well as differences in the details of children’s descriptions of what they were grateful for, remind us that these social characteristics play structuring roles in children’s experiences of gratitude. A future publication focusing on the mixed-methods analysis of over 100 Gratitude Books will attempt to clarify these issues using more systematic comparisons of differences by gender and school type.

In discussing benefactors, children in all focus groups mentioned family members (especially mothers) first. This mirrors the results of a recent article reporting a study carried out with Colombian children, which used visual methods to help children construct ‘“gratitude schemas” of the categories of benefactors that mattered most to them, and found that ‘“family” was always placed in the first rank of the schemas (Carrillo et al., 2022). The importance of the family is unsurprising given its centrality in Colombian society: it is the main source of protection and care, the basic structure in which children develop and grow, and a key context in which they learn behaviors and values—a context that changed greatly over the 20th century but has not diminished in importance (Escobar, 2019). Furthermore, as also found by Carrillo et al. (2022), the importance of family in children’s discussions was not limited to members of the nuclear family, such as parents and siblings. They also frequently mentioned members of their extended or reconstituted families, including grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and stepparents, all of whom can be important figures of socialization in the large family structures typical of Latin America (Escobar, 2019).

Although children generally thought of family members first, when asked for other examples of benefactors, they easily identified many other categories of people (friends, teachers, other school personnel, doctors, and other key workers) and even a few non-human categories (God, nature, institutions, and pets). The presence of pets was unexpected, but again converged with the results of the article on gratitude schemas discussed in the previous paragraph (Carrillo et al., 2022). This suggests that pets form an important source of companionship for many children, and that this could be a valuable topic for more focused research on the development of gratitude (and other social emotions) in the future. Additionally, the personification of abstract benefactors, such as God or nature, reflects the wide range of contexts in which preadolescents and young adolescents experience gratitude. This underscores that they experience gratitude in many aspects of their lives, which may help them to maintain different forms of social and even spiritual relationships. The presence of abstract benefactors also helps to support the theoretical conceptualization of gratitude as a character strength linked to the virtue of transcendence (Peterson & Seligman, 2004 ; Steindl-Rast, 2004). As to whether feelings towards such abstract, transcendent benefactors count as gratitude or are more like appreciation (Watkins et al., 2003), we note that children were specifically asked about situations in which they felt “gratitude” to someone for a benefit received. That they did not limit their responses to strictly human benefactors is thus an interesting empirical finding, which can help broaden our understanding of gratitude experiences in this age group.

In terms of the benefits that children were grateful for, it should be noted that there was a wide variety of general benefits received from many different types of benefactors, and a slightly smaller set of benefits associated with particular benefactors. This demonstrates the flexibility and sophistication of pre-adolescent children’s understanding of gratitude: they are already capable not only of expressing gratitude for material and mundane things like gifts (Bausert et al., 2018), but also for rather far-reaching reasons (Steindl-Rast, 2004), including natural beauty and life itself. Such far-reaching benefits tended to be associated with the transpersonal subthemes of God, nature, and social institutions (apart from giving life, which was also strongly linked to mothers). On the other hand, children did not always articulate explicitly why they were grateful for many benefits, whether material or immaterial. Some of them, especially those from poorer backgrounds, did identify the amount of effort that their parents and other benefactors had to make to provide them with benefits. However, this was not universal, suggesting that awareness of benefactors’ efforts could be a good target for educational intervention. Future research could attempt to probe more explicitly children’s understanding of the effort behind the benefits they receive.

In contrast to the variety of benefactors and benefits mentioned, children did not identify a wide range of feelings associated with gratitude experiences. Almost all children focused on positive emotions such as happiness, joy, and (to a lesser extent) love. The emphasis on happiness is congruent with the thematic analysis of conversations about gratitude between parents and children recently carried out by Midgette et al. (2022), who found that parents thought being happy was both a sign of gratitude and the goal of their behavior as benefactors towards their children. There are two ways of looking at the lack of diversity in feelings cited and the preponderance of positive emotions such as happiness. On the one hand, these findings support the idea that gratitude is a positive force in the life of children, whose promotion can help improve their wellbeing and sense of achievement due to its association with positive emotions (Magno & Orillosa, 2012). Another possibility is that in the focus groups we did not probe sufficiently for children to reveal the full range of emotions (both positive and negative) that they associated with gratitude, which could have allowed them to connect gratitude more explicitly with less obvious but still relevant feelings, such as relief or hope. Gratitude-related interventions might encourage children to think about concrete situations in which they can (or should) feel gratitude, and how certain negative feelings—such as resentment or obligation—can also be triggered in such situations, since it is important to distinguish such feelings from the emotion of gratitude in adults (Gulliford & Morgan, 2017; Shin et al., 2020).

Although our results encompassed all the distinct types of expression of gratitude identified in our literature review, there were fewer references to more complex ways of expressing gratitude. Developing actions that expand and promote connective and finalistic expressions of gratitude could be another target for educational interventions, enabling children to raise the quality of interactions they have when they are grateful. In this way, it is possible that children can enjoy more of the positive personal and social effects that have been identified in the literature as products of the expression of gratitude to others (Bono et al., 2019; Froh et al., 2011; Furlong et al., 2013).

One important limitation of our study—that urges caution in the interpretation of the small differences between groups—is the different dynamics of the conversations that took place, even though the same question script was used. Our data collection methodology relied on focus groups, designed for children to discuss gratitude collaboratively with peers and researchers. As such, it may have neglected individual differences in young people’s experiences of gratitude (Reckart et al., 2017), while also lacking power and controlled manipulations to uncover systematic differences. Regarding the lack of diversity of the feelings that were mentioned by participants in connection with gratitude, our lack of prompting for specific situations in which complex feelings can be triggered may have led us to under-describe the emotional diversity associated with gratitude by the children in our study. Nevertheless, we consider that the linking of feelings to particular benefactors, benefits, and expressions of gratitude in our rich dataset represents a contribution to the literature in terms of helping to create a model of gratitude development that reflects the rich social and emotional worlds inhabited by Colombian children. Future work could expand on the current research by analyzing dyadic conversations on gratitude between Latin American children and their benefactors (such as parents or teachers) along the lines of Midgette et al. (2022) for American children and parents, to tease out commonalities and differences in these groups’ understanding of the elements of gratitude—especially, perhaps, effort—identified by the present study.

Conclusion

This study examined Colombian pre-adolescents’ identification of the components of gratitude: the benefactors to whom and benefits for which they were grateful. Additionally, it examined the emotions they associated with gratitude and the ways in which they expressed and acknowledged it in others. Although family was identified by the participants as the main group of benefactors, and accompaniment and support were highlighted among the benefits, a great diversity of benefactors and benefits was found in the participants’ experiences. Compared to this diversity, the results showed less richness in the range of emotions and expressions that were mentioned in children’s discussions and gratitude books. Both expressions and emotions could be valuable targets of educational interventions to increase children’s awareness of how gratitude relates to practical actions and affective states. Such interventions could be useful to implement for different target populations in various contexts, since we found striking similarities in understandings of gratitude between boys and girls and between public and private schools. Finally, an unexpected result was that participants talked spontaneously about the efforts made by benefactors to deliver them benefits. In future research, it may be worth exploring the relationship between gratitude and effort more directly, both in studies of the development of gratitude in children and in educational programs that deepen their understanding of these concepts. We have shown that the use of visual methods, such as our Gratitude Books, can be a powerful tool for stimulating discussions around social emotions such as gratitude in children’s focus groups, creating rich datasets that give us a window into children’s worlds. This can be particularly helpful when working with an understudied group such as Colombian children. We also contributed to the literature on this group by showing how many of the children’s gratitude experiences were rooted in important aspects of Colombian culture.

References

References

Algoe, S. B., Haidt, J., & Gable, S. L. (2008). Beyond reciprocity: Gratitude and relationships in everyday life. Emotion, 8(3), 425-429. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.425

Bartlett, M. Y., & DeSteno, D. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychological Science, 17(4), 319-325. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01705.x

Bono, G., Froh, J. J., Disabato, D., Blalock, D., McKnight, P., & Bausert, S. (2019). Gratitude’s role in adolescent antisocial and prosocial behavior: A 4-year longitudinal investigation. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(2), 230-243. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1402078

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706QP063OA

Carrillo, S., Robles, D., Bernal, A., Ingram, G., & Gómez, Y. (2022). What gratitude looks like from Colombian children’s perspectives. Journal of Moral Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2021.2012435

Cuello, M., & Oros, L. B. (2016). Construcción de una escala para medir gratitud en niños y adolescentes. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes, 3(2), 35-41. https://www.revistapcna.com/sites/default/files/16-09.pdf

De Souza, M. S., Soares, A. B., & Pizarro de Freitas, C. P. (2022). Social Emotional Learning (sel) program among fifth graders, three and six months later. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 31(1), 35-48. https://doi.org/10.15446/rcp.v31n1.83042

Escobar, R. A. (2019). La familia como una nueva realidad plural multinetnica y multicultural en la sociedad y en el ordenamiento jurídico colombiano. Prolegómenos, 21(42), 195-218. https://doi.org/10.18359/prole.3366

Freitas, L. B. L., Merçon-Vargas, E. A., Palhares, F., & Tudge, J. R. H. (2021). Assessing variations in the expression of gratitude in youth: A three-cohort replication in southern Brazil. Current Psychology, 40(8), 3868-3878. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00334-6

Freitas, L. B. L., Pieta, M. A. M., & Tudge, J. R. H. (2011). Beyond politeness: The expression of gratitude in children and adolescents. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 24(4), 757-764. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722011000400016

Froh, J. J., Emmons, R. A., Card, N. A., Bono, G., & Wilson, J. A. (2011). Gratitude and the reduced costs of materialism in adolescents. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(2), 289-302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9195-9

Froh, J. J., Yurkewicz, C., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Gratitude and subjective well-being in early adolescence: Examining gender differences. Journal of Adolescence, 32(3), 633-650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.006

Furlong, M. J., Froh, J. J., Muller, M. E., & Gonzalez, V. I. (2013). The role of gratitude in fostering school bonding. In D. J. Shernoff & J. Bempechat (Eds.), National Society for the Study of Education Yearbook: Engaging Youth in Schools: Empirically-Based Model to Guide Future Innovations (pp. 58-79). Teachers College Record. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811411601316

Gulliford, L., & Morgan, B. (2017). The meaning and valence of gratitude in positive psychology. In N. J. L. Brown, T. Lomas, & F. J. Eiroa-Orosa (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of critical positive psychology (pp.53-69). Routledge. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315659794-6

Guse, T., Vescovelli, F., & Croxford, S. A. (2019). Subjective well-being and gratitude among South African adolescents. Youth & Society, 51(5), 591-615. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X17697237

Ingram, G. P. D. (2019). Gossip and reputation in childhood. In F. Giardini & R. Wittek (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of gossip and reputation (pp. 131-151). Oxford University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190494087.013.8

Magno, C. P., & Orillosa, J. F. (2012). Gratitude and achievement emotions. Philippine Journal of Counseling Psychology, 14(1), 29-43. https://ejournals.ph/article.php?id=6809

McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 249-266. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.249

McCullough, M. E., & Tsang, J. A. (2004). Parent of the virtues? In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 123-141). Oxford University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195150100.003.0007

Merçon-Vargas, E. A., Poelker, K. E., & Tudge, J. R. H. (2018). The development of the virtue of gratitude: Theoretical foundations and cross-cultural Issues. Cross-Cultural Research: The Journal of Comparative Social Science, 52(1), 3-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397117736517

Midgette, A. J., Coffman, J. L., & Hussong, A. M. (2022). What parents and children say when talking about children’s gratitude: A Thematic Analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31(5), 1261-1275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02222-9

Morgan, B., & Gulliford, L. (2017). Assessing influences on gratitude experience: Age-related differences in how gratitude is understood and experienced. In J. R. H. Tudge & L. B. Freitas (Eds.), Developing gratitude in children and adolescents (pp. 65-88). Cambridge University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316863121.004

Oros, L. B, Schulz-Begle, A., & Vargas-Rubilar, J. (2015). Children’s gratitude: Implication of contextual and demographic variables in Argentina. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 13(1), 245-262. https://doi.org/10.11600/1692715x.13114130314

Palhares, F., Freitas, L. B. L., Merçon-Vargas, E. A., & Tudge, J. R. H. (2018). The development of gratitude in Brazilian children and adolescents. Cross-Cultural Research, 52(1), 31-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397117736749

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. American Psychological Association.

Poelker, K. E., & Gibbons, J. L. (2018). The development of gratitude in Guatemalan children and adolescents. Cross-Cultural Research, 52(1), 44-57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397117736518

Poelker, K. E., & Kuebli, J. E. (2014). Does the thought count? Gratitude understanding in elementary school students. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 175(5-6), 431-448. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2014.941321

Poelker, K. E., Gibbons, J. L., & Maxwell, C. A. (2019). The relation of perspective-taking to gratitude and envy among Guatemalan adolescents. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 8(1), 20-37. https://doi.org/10.1037/ipp0000103

Reckart, H., Huebner, S. E., Hills, K. J., & Valois, R. F. (2017). A preliminary study of the origins of early adolescents’ gratitude differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 44-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.020

Ruch, W., Gander, F., Wagner, L., & Giuliani, F. (2021). The structure of character: On the relationships between character strengths and virtues. Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(1), 116-128. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1689418

Shin, L. J., Armenta, C. N., Kamble, S. V., Chang, S. L., Wu, H. Y., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2020). Gratitude in collectivist and individualist cultures. Journal of Positive Psychology, 15 (5), 598-604. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1789699

Steindl-Rast, D. (2004). Gratitude as thankfulness and as gratefulness. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 282-289). Oxford University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195150100.003.0014

Tesser, A., Gatewood, R., & Driver, M. (1968). Some determinants of gratitude. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(3), 233-236. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025905

Tian, L., Du, M., & Huebner, E. S. (2015). The effect of gratitude on elementary school students’ subjective well-being in schools: the mediating role of prosocial behavior. Social Indicators Research, 122(3), 887-904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0712-9

Tudge, J. R. H., Freitas, L. B. L., & O’Brien, L. T. (2015). The virtue of gratitude: A developmental and cultural approach. Human Development, 58(4-5), 281-300. https://doi.org/10.1159/000444308

Watkins, P. C. (2014). Gratitude and the good life. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7253-3_11

Watkins, P. C., Woodward, K., Stone, T., & Kolts, R. L. (2003). Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality, 31(5), 431-451. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2003.31.5.431

Wu, R., Huebner, E. S., & Tian, L. (2020). Chinese children’s heterogeneous gratitude trajectories: relations with psychosocial adjustment and academic adjustment. School Psychology, 35(3), 201-214. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000358

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Sonia Carrillo, Yvonne Gómez-Maquet, Gordon Ingram, Juan Pablo Molano Gallardo. (2025). Expedition Gratitude : Evaluation of an Educational Program to Promote Gratitude in Colombian Schools . Research in Human Development, 22(1), p.56. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2025.2524300.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The RCP is published under the Creative Commons license and can be copied and reproduced according to the conditions of this license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5). RCP articles are available online at https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/psicologia/issue/archive. If you would like to subscribe to the RCP as reader, please go to https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/psicologia/information/readers and follow the instructions mentioned in the webpage. Additionally, a limited number of print journals are available upon request. To request print copies, please email revpsico_fchbog@unal.edu.co.