Identification of Components Associated with the Operation of Mutual Aid Groups: A Scoping Review

Identificación de Componentes Asociados al Funcionamiento de los Grupos de Ayuda Mutua: Una Revisión Panorámica.

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/rcp.v32n2.103633Keywords:

community participation, implementation sciences, mental health, self-help group, psychosocial support systems (en)ciencias de la implementación, grupos de autoayuda, sistemas de apoyo psicosocial, salud mental, participación de la comunidad (es)

This research aims to identify the components associated with the benefits of Mutual Aid Groups (mags). Although they have been singled out by the evidence, specific information on their nuclear components is lacking. Based on the methodological approach of Arksey and O’Malley and the Joanna Briggs Institute, all research studies (Pubmed, Scopus, Scielo, Embase, and Redalyc) and gray literature examining these groups were included. The search was carried out throughout 2022 with the following codes: mutual aid groups; self-help groups. We reviewed 62 papers and 37 were included from a total of 2064 articles. The study shows that the components associated with beneficial results are: active agency, coping strategies, recognition, management of emotions, problem-solving strategies, supportive interaction, trust, self-identity construction, and strengthening of social networks. Thus, it reaffirms that mags are an effective option to address health problems. The application of these components could also contribute to achieve these benefits.

El objetivo de esta investigación es identificar los componentes asociados a beneficios de Grupos de Ayuda Mutua (gam). Aunque han sido recomendados por la evidencia, se carece de información concreta sobre sus componentes nucleares. Con base en el enfoque metodológico de Arksey y O`Malley y del Instituto Joanna Briggs, se incluyeron todos los estudios de investigación (Pubmed, Scopus, Scielo, Embase y Redalyc) y literatura gris, que examinan estos grupos. La búsqueda se realizó en 2022, con el siguiente código: Mutual Aid Groups / grupos de ayuda mutua; Self-Help Groups/ grupos de autoayuda. Se revisaron 62 estudios, aunque se incluyeron 37 de un total de 2064. Entre los componentes asociados a beneficios, se encuentran la agencia activa, estrategias de afrontamiento, reconocimiento y gestión de emociones, resolución de problemas, interacción de apoyo, confianza, construcción de identidad y fortalecimiento de redes sociales. Los gam son una opción efectiva para abordar problemas de salud y aplicar estos componentes podría contribuir a sus beneficios.

Recibido: 13 de julio de 2022; Aceptado: 11 de noviembre de 2022

Abstract

This research aims to identify the components associated with the benefits of Mutual Aid Groups (MAGs). Although they have been singled out by the evidence, specific information on their nuclear components is lacking. Based on the methodological approach of Arksey and O’Malley and the Joanna Briggs Institute, all research studies (Pubmed, Scopus, Scielo, Embase, and Redalyc) and gray literature examining these groups were included. The search was carried out throughout 2022 with the following codes: mutual aid groups; self-help groups. We reviewed 62 papers and 37 were included from a total of 2064 articles. The study shows that the components associated with beneficial results are: active agency, coping strategies, recognition, management of emotions, problem-solving strategies, supportive interaction, trust, self-identity construction, and strengthening of social networks. Thus, it reaffirms that MAGs are an effective option to address health problems. The application of these components could also contribute to achieve these benefits.

Keywords

community participation, implementation sciences, mental health, self-help group, psychosocial support systems.Resumen

El objetivo de esta investigación es identificar los componentes asociados a beneficios de Grupos de Ayuda Mutua (GAM). Aunque han sido recomendados por la evidencia, se carece de información concreta sobre sus componentes nucleares. Con base en el enfoque metodológico de Arksey y O`Malley y del Instituto Joanna Briggs, se incluyeron todos los estudios de investigación (Pubmed, Scopus, Scielo, Embase y Redalyc) y literatura gris, que examinan estos grupos. La búsqueda se realizó en 2022, con el siguiente código: Mutual Aid Groups / grupos de ayuda mutua; Self-Help Groups / grupos de autoayuda. Se revisaron 62 estudios, aunque se incluyeron 37 de un total de 2064. Entre los componentes asociados a beneficios, se encuentran la agencia activa, estrategias de afrontamiento, reconocimiento y gestión de emociones, resolución de problemas, interacción de apoyo, confianza, construcción de identidad y fortalecimiento de redes sociales. Los GAM son una opción efectiva para abordar problemas de salud y aplicar estos componentes podría contribuir a sus beneficios.

Palabras clave

ciencias de la implementación, grupos de autoayuda, sistemas de apoyo psicosocial, salud mental, participación de la comunidad.Introduction

STARTING IN 1970, an interdisciplinary collaboration process began that validated both the biomedical, community, and psychological approaches that generated the denominated “new intercultural psychiatry” (Kleinman, 1987). Regarding clinical care processes, other approaches were considered beyond the biomedical perspective. The social environment and community care have become more relevant in the care of people facing mental health problems. This panorama implies some challenges at an ethical, social, administrative, and even epistemological level (Patel et al., 2018).

Especially since 1990, with the Declaration of Caracas, mental health care aims to move from psychiatric clinics with asylum characteristics, and create psychiatric wards in general hospitals. In addition to integrating mental health into primary health care, it is proposed the individual and the community as the axis of recovery (World Health Organization-WHO- & Pan American Health Organization - PAHO-, 1990). The latter concept is articulated in the expression nothing about us without us. Explained as: those who suffer from mental health problems affirm their empowerment and invite them to defend their participation in the structuring of care services and research in the field.

This recovery approach centers the desires of people with mental health disorders as the main focus of the goals of care. Beyond the observable reduction in the manifestation of the disorder, it aims to restoration of cognitive abilities, as well as community and occupational performance. It emphasizes the efforts of the person to live by their own meaning, consistent with the role that each person wishes to carry out in their various contexts. This ultimately will lead to fulfillment (Davidson et al., 2005). Between 75 and 90% of those who need treatment for mental problems do not obtain it in their contexts (WHO, 2016). Hence, so low-cost interventions, as Mutual Help Groups (MAG) in mental health, could be beneficial (Cohen et al., 2012; Nickels et al., 2016).

On the other hand, MAG could be a complementary tool to clinical care itself. This is supported by studies that mention that up to 70% of patients remain depressed after treatment and 50% will not continue with the drugs due to side effects (Connolly & Thase, 2012 ; Rosenblat et al., 2019 ; Kelly et al., 2019). In some cases, it has been proposed as a mechanism to improve the financial pressure associated with psychosocial disability (Russo et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2019).

Although it has been mentioned that there is a lack of agreement on definitions of MAGs (Chaudhary et al., 2013), multiple definitions agree in groups where mutual peer support is provided. These face-to-face or virtual meetings are designed, in response to mental health problems or situations. The control of the group remains with its members rather than with an external agency (Chaudhary et al., 2013; Wilson, 1994 ; Borkman, 1999; Steinke, 2000; Baldacchino & Rassool, 2006). Self-help groups are described as “groups composed of people who meet regularly to help each other cope with a life problem” by the American Psychological Association (APA, 2019). MAGs have also been described as mutual aid and mutual support groups, as well as the broader terms self-help groups and mutual aid groups, or peer support groups (Pistrang et al., 2008).

On the other hand, core components are denominators in empirically proven treatments that serve as a reference point for the understanding, implementations, and evaluation of an intervention. These may be techniques, contents, or discrete skills (Chorpita et al. 2005; Garland et al., 2008). Consequently, this core component approach to evidence-based practice improves better decision-making when implementing health strategies or plans (Chorpita et al., 2007).

Some previous studies as the one by Rettie et al. (2021) sought to determine the core components in support groups led by peers, that are very similar to MAGs. It highlighted the following components concerning problematic substance use: linkage to community support, structured environment, healthy lifestyle, expectations of positive and negative consequences, involvement in protective activities, adequate reward system. Also, there were found as components regarding the problematic: management of high-risk situations, trust-building activities, developing assertive communication style, and presence of people who support their recovery. The most important considered core component was the ability of the group members to improve their self-confidence and the less important component was the provision of group rewards. Although self-help groups have some evidence supporting their effectiveness, there is still no clarity on the appropriate way to document their effect. Qualitative and quantitative methodologies have been used to document their positive consequences and the processes that lie beneath.

Qualitative approaches have shown beneficial outcomes in MAGs, while quantitative studies that, for the most part, examine outcomes in psychiatric symptoms, show mixed effects, especially on symptoms and social functioning (Pistrang et al., 2010). However, some authors as Humphreys & Rappaport (1994), propose that quantitative methods may not be the most suitable to evaluate MAGs in their entirety. This due to the aspects mentioned in its definition (characteristics difficult to control and randomize). Some meta-analyses that have included randomized studies mention the little impact on clinical manifestations (Lloyd-Evans et al., 2014). But it is mentioned that these studies are largely randomized and the causal mechanisms remain unspecified (Markowitz, 2015).

Qualitative studies focus on variables as empowerment, social cohesion, and life skills. While quantitative studies focus on psychiatric symptoms’ outcomes, most often without integrating both aspects into a single model. Making the ability to specify the core components by which these MAGs achieve certain benefits, particularly challenging (Markowitz, 2015). Specifying these components could be very useful in the implementation of the groups, especially in countries facing difficulties accessing mental health care and recovery strategies.

Although these strategies for the recovery of mental health are widely recommended by scientific studies and public policy documents, some methodological elements have not been described or explored. This impacts their correct application and the achievement of the objectives that are proposed. Based on the above, this article aims to identify the components associated with mutual aid benefits.

Materials and Methods

This scoping review is based on the methodological framework introduced by Arksey and O’Malley (Tricco et al., 2018) and the methodology manual published by the Joanna Briggs Institute for scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2015 ).

Sample, Inclusion, and Exclusion Criteria

To perform the scope search, Crochrane, Pubmed, Scopus, Scielo, and Redalyc databases were taken as well as grey literature searches (similar search terms aimed at providers, agencies, care support services). The boolean code was selected from MESH descriptors and definitions widely accepted in the literature, this in the case of the term mutual aid groups. The investigation was carried out from the following keywords (MESH and DESC): mutual aid groups / grupos de ayuda mutua; Self-Help Groups / grupos de autoayuda, in the mentioned databases. Likewise, manual searches were carried out in the reference lists of the relevant articles to identify the articles and documents that were not generated in the database search.

The search was carried out between January and May 2022, studies from 1990 to 2021 were included. This as the starting year was considered by the recent Declaration of Caracas for that moment. The selected studies had to meet the following inclusion criteria: experimental, quasi-experimental, observational studies, guides, narrative reviews, and policy or program documents, that examined health mutual aid groups were included. Those articles that did not have group activities, in most cases were excluded. As well as studies that did not meet the definition of a mutual aid group, and that did not mention core components, were also excluded.

Study Protocol

The steps recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute were followed (Tricco et al., 2018), in addition to those proposed by Arksey and O`Malley (Peters et al., 2015). PCC strategy [Population, Concept, and Context] for formulating the review question, where P: People with any disease, C: Core components of Mutual Aid Groups, and C: Community Psychosocial Recovery Interventions. The review question was “What are the components associated with Mutual Aid Groups outcomes?”.

After the search was conducted, the bibliographic citations were identified in the EndNote X9/2018 program, duplicate studies were eliminated. For the selection of studies, titles and abstracts were initially reviewed according to the inclusion criteria by two researchers. The researchers performed the verification of the eligibility criteria using a random sample of 25 articles. Using Cohen’s coefficient K, the agreement between observers was determined, that was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.66-1.00), considered a good agreement. The selection of studies was made by consensus of the reviewer’s panel according to the critical appraisal tools and those that passed the quality assessment were included in the review. They were considered of acceptable quality when the four evaluators agreed on 70% of the elements of the assessment instruments as positive. Two Ph.D.-degree reviewers assessed titles and abstracts according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. The reviewers then independently reviewed each recovered title and summary to determine eligibility using the inclusion criteria. After this, the full text was reviewed to determine its eligibility.

All eligible articles were entered in Microsoft Excel, where the following information was extracted: type of publication, study objectives, the definition of Mutual Aid Group. As well as: the definition of elements related to improvement, description of the elements used in the group, description of the core components, name, and description of the improvement indicator; also, were included: type of indicator (process, result), measurement methods, evidence to support the indicator and results. Data were organized and analyzed using a conventional content analysis approach (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005), referencing research questions as a guide (Levac et al., 2010). Duplicate components or features were removed. If some search results fell into multiple categories, an agreement was sought with the researchers.

Results

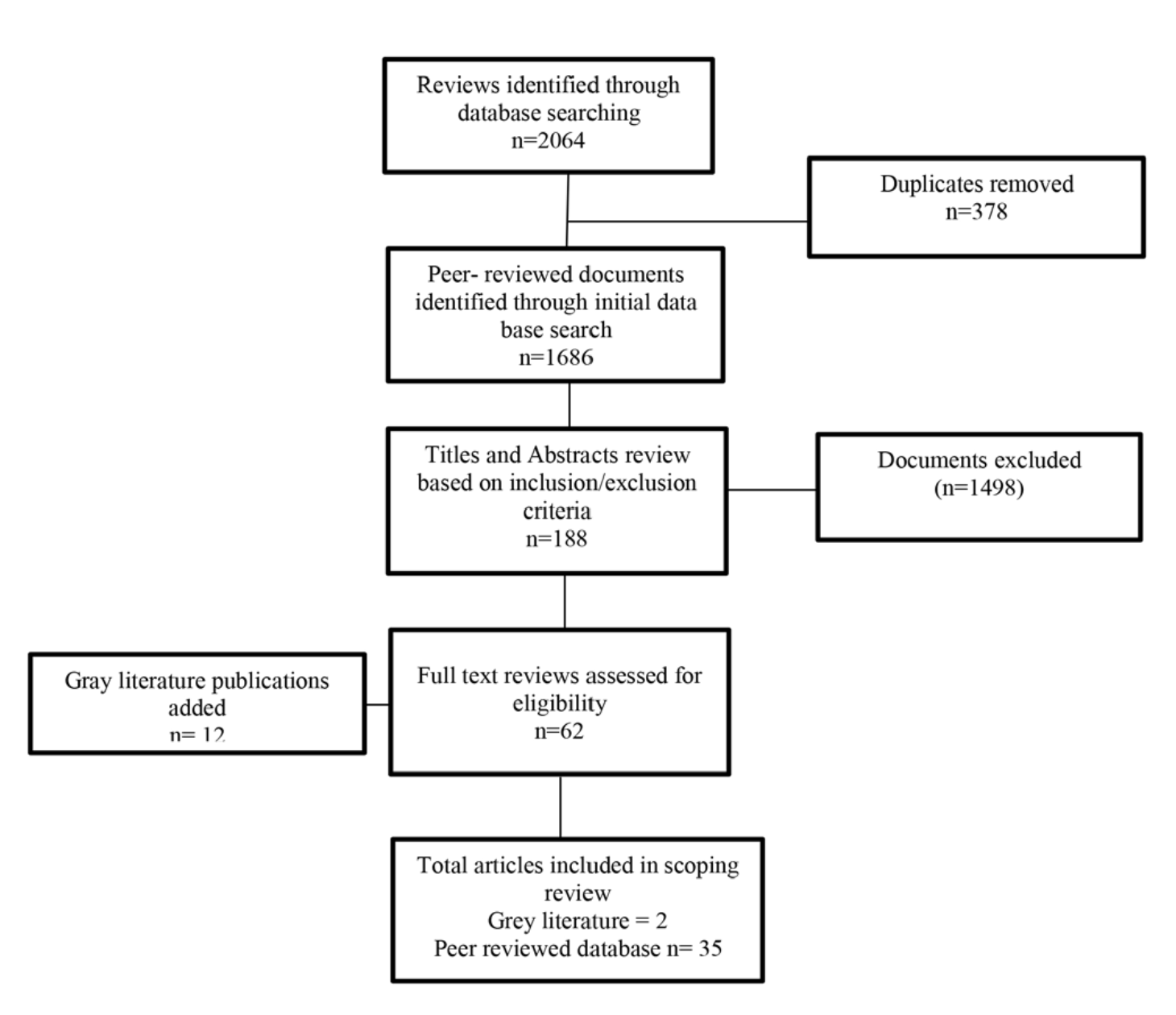

Of the 62 articles included from databases and 12 from gray literature, 37 associated some form of benefit of mutual aid groups with core components (Figure 1). Among the chosen research studies, eight related to chronic diseases were found, as cancer, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, stroke. Of bipolar disorder and psychosis, two articles were found, one of them qualitative. On depression and anxiety, nine articles were selected, from quantitative methodologies, including an implementation protocol. On the consumption of psychoactive substances, six studies were found. Six studies discussed core components in mental health problems without a specific diagnosis.

Figure 1

:

Flowchart of search results

Two more mentioned the components in the framework of behavioral problems in adolescents, also two, one qualitative and the other quantitative, addressed caregivers in their theme (Table 1). Subsequently, the grouping proposed by experts considers the following key elements. To summarize the data, we performed a content analysis of the different articles selected and the information recorded in the Excel table. This procedure was done with the aim of detecting the key categories in each of the elements of interest (core component, and benefit) in each of the included articles.

Table 1:

Description of the findings

Group theme

Number of papers

Country

Type of research

Year

History

of sexual violence

1

USA

Review

2018

Chronic

diseases

8

USA

(2), Australia, United Kingdom (2), Mexico, Guatemala

Qualitative,

descriptive correlational, cases and controls

2016-2020

Bipolar

disorder and psychosis

2

USA,

United Kingdom

Qualitative

and quantitative, descriptive, longitudinal

2014,

2019

Depression

and anxiety

9

USA,

Germany, Chile, UK (2), India, Ghana, Spain

Review,

correlational descriptive, implementation protocol,

qualitative, reflection paper

2016-2021.

Substance

abuse

6

USA

(4), UK, China

Review,

descriptive correlational

1996,

2015-2019

Acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome

1

USA

Qualitative

1993

Behavioral

disorders in adolescents

2

USA,

Canada

descriptive,

cross-sectional Reflection paper

2001,

2016

Generalities

of Mutual Aids Groups and empowerment

6

Ghana,India,

UK, Germany

Review,

longitudinal descriptive, reflection paper

2012

2019 2015 2017

Caregivers

2

USA

Descriptive

Qualitative

2018,

2020

Once the relevant data for each study was identified, the elements of interest found in the articles were consolidated under the consensus of experts into a new category. This category was established as a core component:

Coping strategies understood as techniques learned or enhanced in the group that facilitate the individual approach to adverse personal situations. Emotional recognition and management as the identification of aspects on the group dynamics that have not been considered before and that are important for the emotion’s identification. Problem solving: understood as the perception of some psychological abilities, including specific techniques or individual strategies that do not belong to a proper technique, that allow facing daily difficulties. Supportive interaction: it can be understood as the active exploration of group actions for mental health by the same people. This with the intention of relating to others who can be helped or from whom help can be received. Trust: group’s value that allows group doings in which a person can tell freely what has happened to them without expecting a value judgment that makes them feel wrong. Identity Building: conceptualized as the identification and appropriation in the group of individual aspects that are part of the personality and that are necessary to consider in each recovery process. Social networks: it is perceived as the recognition of the group as a tool that provides the person with constant availability for their difficulties. Active agency: can be understood as the increase of abilities or moving these skills to functions, which has been obtained through the participation in the group (Table 2).

Table 2:

Procedure for consolidating the elements of interest found in

the articles, into a new category that was established as a core

component based on expert judgment

Category

Definition

Conformation of the concept

Authors

Active agency

Increase of capacities or the passage of these

capacities to functions, which have been given from the

participation in the group.

Active

agency

Bernabéu-Álvarez

et al. (2020).

Acquisition

of specific skills

Petrini

et al. (2020) ; Sample et al. (2018)

Empowerment

Stang

& Mittelmark (2009); Markowitz (2015)

Self-determination

Sample

et al. (2018)

Coping strategies

Techniques learned or enhanced in the group

which facilitate the individual approach to adverse personal

situations.

Coping

skills

Landstad,

et al., (2020)

Coping

self-efficacy

O’Dwyer

et al. (2021)

Coping

strategies

Longden

et al. (2018); Sample et al. (2018)

.

Emotion recognition and management

Identification of own difficulties through group

dynamics. Included in this code are all citations that

explicitly or implicitly mention the processes carried out

in the group that made it possible to identify personal

difficulties related to mental health.

Emotion

recognition and management

Anderson

& García (2015)

Social

emotional support

Repper

& Carter (2011)

Ngai et al. (2021b)

Manning

et al. (2020); Juarez-Ramirez et al. (2020

); Nieto

Zermeño (2008).

Emotional

coping

Sample

et al. (2018).

Problem solving

Group

contribution that occurs by identifying individual coping

strategies in group dynamics that had not been considered

before and that are important for recovery.Included in this

code are all citations that explicitly or implicitly mention

the construction of new concepts about the individual

problem. These from the elements found by itself in the

group dynamics.It refers to relationships given in the group

perceived as horizontal and generating trust between

members.

TroubleshootingSelf-efficacy

Bernabéu-Álvarez

et al., (2020); Yip

(2002); Gona et al. (2020);

Wijekoon et al., (2020); Rossi et

al., (

2014) Magura et al. (2007)

; Ahmad

et al. (2021); Carlén & Kylberg

(2021).

Category

Definition

Conformation of the concept

Authors

Supportive interaction

It refers to relationships given in the group

perceived as horizontal and generating trust between

membersActive exploration of the same people of group

actions for mental health with the intention of relating to

other people.Included in this code are all citations that

make explicit or implicit mention of activities that show a

group dynamic referred to by the participants. In which the

possibility of expressing what is thought is shown.

Supportive

Interaction

Ngai,

et al., (2021A)

Feedback

Landstad,

et al., (2020)

Sense

of trust

Fernandez-Jesus,

et al., (2021)

Cohesion

Fernandez-Jesus

et al., (2021) ; Cheung

& Ngai (2016)

Exchange

Bjerke

(2012)

Freedom

of expression

Chaudhary

et al. (2013) ; Akin et al. (2021)

Integration

Trojan

et al. (2016)

Shared

understanding

Carlén

& Kylberg (2021) ; Nieto Zermeño (2008)

Mutual

help

Carlén

& Kylberg (2021) ; Avis et al. (2008)

Active

listening

Carlén

& Kylberg (2021) ; Nieto Zermeño (2008)

Equality

of relationships

Brown

et al. (2008)

Solidarity

Rossi

& Tognetti Bordogna (2014)

Reciprocity

Valencia

Murcia & Correa García (2006)

Social

learning

Gracía

Fuster (1996)

Identity construction

This code includes all citations that make

explicit or implicit mention of a process of identifying

characteristics of one’s own personality. Also in the

behavior or in the thoughts of the other people in the

group. Identification of parental roles, such as father,

mother, brother, etc., are included.

Identity

construction

Chambers

et al. (2017) ; Ngai et al. (2021b)

; Wijekoon

et al. (2020) ; Martínez et al. (2021)

Positive

image

Longden

et al. (2018)

Trust

Included in this code are all citations that

explicitly or implicitly mention Mutual Aids Groups dynamics

where the individual characteristics that may be considered

problematic by the person do not constitute a difficulty in

the relationship with the other.Perception of the dynamics

of the group with the freedom to express an opinion or speak

what is thought.Reception of particularities of each person

without criticism or pointing out those that the person

perceives as negative in himself.

Honesty

Chambers

et al. (2017)

Leadership

Landstad,

et al. (2020)

Trust

Fernandez-Jesus

et al., (2021) ; Ahmad et

al., (

2021); Ngai et al., (2021b)

Engagement

Rossi

& Tognetti Bordogna (2014).

Without

hierarchies

Activament

Catalunya Associació (2021)

Social networks

It refers to relationships given in the group

perceived as horizontal and generating trust between

members. Recognition of the group as a tool that provides

the person with constant availability for their

difficulties, beyond specific meetings.

Democracy

Patil

& Kokate (2017)

Decentralization

Patil

& Kokate (2017)

Social

networks

Kelly

et al. (2019)

Mobility

Ahmad

et al. (2021)

Accessibility

Southall

et al. (2019)

From the proposed categories, it can be observed that the most detected core component in the different studies was that of supportive interaction (16 times). Followed by social networks (11 times), and problem solving and active agency (eight times). Emotion recognition and management was the least identified. The authors who most identify components are Rossi and Tognetti Bordogna (2014), Nieto Zermeño (2008), Wijekoon et al. (2020), and Sample et al. (2018) .

After this, the outcomes of the MAGs were synthesized in five categories: Quality of Life, Improvement, Mental Health Learning, Social Functioning, Life Skills, Hope, and the relationship of the components with these outcomes was investigated in the selected studies. The frequency was established for the core component and the benefits, according to the studies that cite it considering the new consolidation. The work of Petrini et al. (2020) is the one that reports the most benefits, being social functioning and health learning the ones that it recognizes. Yip (2002) identifies four benefits where skills for life is the most frequent. Ngai et al. (2021b), Moos (2008), Landstad et al. (2020), and Ahmad et al. (2021) report four benefits in their studies, the most frequently reported being life skills, social functioning, and improvement in quality of life (Table 3).

Table 3:

Benefits identified in each of the included studies

Author/Benefit

A

B

C

D

E

Petrini

et al. (2020)

X

X

Yip

(2002)

X

X

X

Ngai

et al. (2021a)

X

X

Moos

(2008)

X

X

X

Landstad

et al. (2020)

X

X

X

Ahmad

et al. (2021)

X

X

Sample

et al. (2018)

X

X

Kelly

et al. (2019)

X

Seebohm

et al. (2013)

X

X

Fernandes-Jesus

et al. (2021)

X

Author/Benefit

A

B

C

D

E

Matusow

et al. (2013)

X

X

X

Repper

& Carter (2011)

X

X

Southall

et al. (2019)

X

X

Carlén

& Kylberg (2021)

X

X

Ngai

et al. (2021b)

X

X

X

Nieto

Zermeño (2008)

X

X

Wijekoon

et al. (2020)

X

X

Mao et

al. (2021)

X

Stang

et al. (2009)

X

X

Cohen

et al. (2012)

X

X

Gugerty

et al. (2019)

X

Cheung

& Ngai (2016)

X

Bernabéu-Álvarez

et al. (2020)

X

Patil

& Kokate (2017)

X

Gona

et al. (2020)

X

Markowitz

(2015)

X

Trojan

et al. (2016)

X

O’Dwyer

et al. (2021)

X

Nickels

et al. (2016)

X

Longden

et al. (2018)

X

Chen

et al. (2014)

X

Brown

et al. (2008)

X

Gracía

Fuster (1996)

X

Hernández

Zamora et al. (2010)

X

Avis et

al. (2008)

X

Martínez

et al. (2021)

X

Finally, the relationship between the core component and the detected benefit was determined on a heat map (Table 4). It is found that the components that were most related to benefits were active agency, supportive interactions, and problem solving. Those that were moderately related were trust, identity construction, and social networks. Those that were related to improvement in few studies were emotional management and coping skills.

Table 4:

Frequency of relationship between central component and

perceived benefit

Outcomes

A

B

C

D

E

Coping

strategies

Emotional

Recognition and Management

Problem

Solving

Supportive

Interaction

Trust

Identity

Building

Social

Networks

Active

Agency

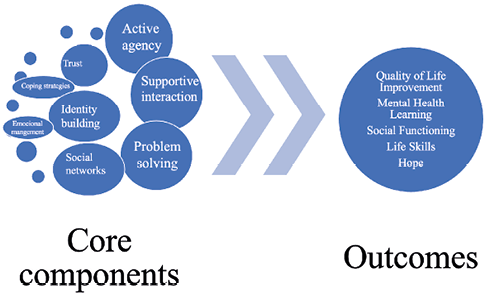

As Figure 2 indicates, there are components that are more relevant to achieve the benefits of MAGs described by the research reviewed. Other components more related to techniques of health services were not so decisive in the outcomes found, especially Emotional Recognition and Management.

Figure 2

:

Core components and outcomes

Discussion

The objective of this scoping review was to determine the core components associated with positive results in the Mutual Aid Groups (MAGs). The above, seeking to overcome the barriers for the implementation of proposed strategies for mental health (Agudelo-Hernández & Rojas-Andrade, 2021). The results identified a total of 37 documents that allowed their detection. Although there a few studies with similar scopes to the current one, the findings are discussed in the light of different theoretical postulates and scientific literature on the subject.

In this review, the following core components were identified: active agency, coping strategies, emotion recognition and management, problem solving, supportive interaction, trust, identity building, and social networks. Some previous studies as the one by Rettie et al. (2021) sought to determine the components in peer-led support groups, which are very similar to MAGs. And showed the following components in relation to the improvement of problematic substance consumption: structuring a life project, healthy life habits, real expectations, involvement in protective activities. As well as the following components: appropriate rewards, detection of risk of relapse, and self-confidence. The most important component considered was the group’s ability to improve self-confidence and the least important component was the provision of group rewards.

The results found in this scoping review differ and agree with some central elements identified in the mentioned studies. However, the different methodologies used to reach their description must be considered. This work generated a new categorization and definition of the central components based on the expert consensus in which the different elements identified in the different studies were consolidated.

For Ngai et al. (2021a), the benefits of the group also have to do with the active role of the facilitators, with their knowledge and skills. The presence of external facilitators has also been analyzed through communicative rationality in the public sphere. This has been considered, in the case of Chaudhary et al. (2013), as fundamental to maintain the independence of powerful structures as the state. Since without this separation, associations would not try to develop according to their own logic or by creating their own definition of needs (Eley, 1992). The mentioned would imply for MAGs the loss of their role as places where people reconceptualize health and social problems with their direct experience (Munn-Giddings, 2003; Chaudhary et al., 2013; Avis et al., 2008).

MAGs have been specified as spaces where the discomfort that supervision can generate is absent (Akin et al., 2021 ). Seebohm et al. (2013) argue that many groups acted against stigma in their families, friends, and other stages that attracted considerable interest. This also improved the ability to function socially in terms of learning and development.

Likewise, in MAGs, medical problems are both individual and shared by all, and that also helps to de-stigmatize them, something that Magura et al. (2007), specify as a spiritual component. This refers “to the potentially healing power inherent in interpersonal relationships based on reciprocity and equality”. Markowitz (2015) points out that MAGs reduce stigma indirectly. This by contradicting the idea that people with mental health disorders cannot participate in the construction of their own lives, and even of programs. This agrees with Stewart (1990) and Katz (1970). In Yip (2002), among the support strategies provided by other members, those that allowed sharing guidelines for the management of the disease (for example, drug intake) were fundamental. Therefore, supportive interaction, through the communication of feelings and knowledge based on real situations among the members of the group, is related to an understanding of the need for support. Achieving this through the learning of useful strategies for coping with chronic conditions, especially in young people (Ngai et al., 2021b; Magura et al., 2002).

In terms of well-being, Seebohm et al. (2013) found that most groups promoted a healthy lifestyle, exercise, and diet inside of their meetings, including access to complementary therapies, walking groups, and sex education. Thus, generating a perception of MAGs as safe places where members felt cared for. Moos (2008) considers participation in satisfying and rewarding activities as strategies that are present in this core component. In the same way, Corrigan et al. (2005) conceptualizes that participation in MAGs can have some direct and indirect benefits on the quality of life and the symptom reduction. This through strategies to strengthen the self-concept and to improve social networks that provide social support. In addition to the change of role, from someone who receives help, to someone who gives it in a space to share and take care of oneself and others (Markowitz, 2015 ; Weaver & Salem, 2005 ; Repper & Carter, 2011). Other MAGs members specified enthusiasm for being with another, courage and desire to explore as core components of their group (Magura et al., 2007).

On the other hand, income-generating activities allowed the groups to grow. Providing learning opportunities for asset and money management as a precursor to income-generating projects was a critical component of capacity development (Gona et al. 2020). Similarly, for Yip (2002) it is essential in MAGs to carry out processes related to the guidelines to achieve adequate employment. According to empowerment theory, this could correspond to greater control and awareness of the sociopolitical context in which groups operate (Gona et al., 2020; Kieffer, 1984; Zimmerman, 2000; Zimmerman & Rappaport, 1988). Compared to the identity component, Markowitz (2015) mentions that when people with mental illness integrate into significant groups and engage in productive activities. Their self-awareness increases, MAGs assume there is enough power within the group to manage themselves, instead of looking elsewhere for solutions (Carlén & Kylberg, 2021; Southall et al., 2019). So, it can also increase self-confidence (Carlén & Kylberg, 2021 ).

Along the same lines, other authors (Ngai et al., 2021b; James et al., 2020) have mentioned that as people join in MAGs, they understand their own and others’ difficulties. And because of that, they can improve their abilities and turn them into functions. Similarly, the meetings contribute to the development of norms framed in trust and reciprocity, as requirements for strengthening social capital (Putnam & Nanetti, 1993). This could propose the empowerment variable as a mediator in solid behavioral changes (Gugerty et al., 2019; Stewart, 1990; Katz, 1970).

In this sense, cohesion is essential for the sustainability of a MAG (Cheung & Ngai, 2016). For Yip (2002) those elements that made up group cohesion were sharing data, strengthening dialectical spaces, entering taboo areas. What the authors called a feeling of being “all in the same boat”. Within this cohesion, it was mentioned as fundamental to generate conditions in the groups to show “an authentic identity”. Considering honesty as a core component of the correct functioning of a MAG (Chambers et al., 2017), and the promotion of communication mechanisms as a group operating strategy (Moos, 2008). The above was reinforced by the concept of sense of community, knowledge and respect of the other, as a step towards self-knowledge. This occurred through mutual learning strategies, that resulted in, apart from increasing that sense of belonging, a decrease in hospitalizations and an ease of access to health services (Matusow et al., 2013).

The provision of affective support has a facilitating role between group relationships and the perception of well-being. In addition, the reception and provision of emotional support sequentially mediated the relationships between group interaction with the purpose in life, being satisfied with life and individual growth. These are part, in turn, of other components (Ngai et al., 2021a). In Yip (2002), among the strategies of support given by other members, those that allowed sharing guidelines for the management of the disease (for example, drug intake) were fundamental. Martin et al. (2009), mentions the control of symptoms as a result, especially in chronic diseases. In these processes of self-knowledge of the disease itself and of the body itself were mediated.

For the above, core components were emphasized as understanding, emotional support, increased confidence, adequate care in quality, continuity and time in health services. Also, good relationship with primary care physician; clinical competence knowledge of the disease and knowledge of medications. In this sense, MAGs have been described as an ideal place to accumulate knowledge about accessibility to local resources and to express opinions on experiences with health professionals (Southall et al. 2019; Carlén & Kylberg, 2021). In the study carried out by Giarelli & Spina (2014), this was described as ways to provide tools for practical life, beyond medical recommendations that cannot necessarily be applied.

Coping strategies have been defined as ones perceived ability to manage “stressful or threatening environmental demands” (Benight et al., 1999), and has emerged as a MAGs strategy for a variety of physical and mental health problems, including stress, anxiety, and depression (Haslam et al., 2014; O’Dwyer et al., 2021). In this sense, for Moos (2008), the reinforcement of the self-efficacy and coping skills of the members, was considered as a fundamental active ingredient of the improvement mechanisms in the MAGs. The exchange of information and individual experiences in the group spaces make up learning through modeling and communication skills, and also this is made by the presence of leaders to follow and the individual guidance provided to the participants in a time even outside the meetings. This is also reported as a mediator of the impact on the increase in quality of life given by the MAGs (Magura et al., 2007).

The inclusion of articles in Spanish, Portuguese, and English represents a limitation of this review. So, it is recommended for future work to consider other languages that may account for the generation of new knowledge about MAGs. Another limitation includes their scientific rigor because of the type of review in the scoping. Although the conclusions generated must be taken with caution, it must also be recognized that the study of mutual aid and its effectiveness in the recovery processes of mental health. It requires new research methodologies that allow the generation of new elements of evidence to overcome implementation problem.

Conclusions

Despite being recommended in the legislative, scientific, and technical elements of many countries (Patel et al., 2018), community interventions for mental health have had difficulties in their implementation. At this point, the need for methodologies that contribute to biomedical sciences with therapeutic approaches is reaffirmed. This overcome the passive and unilateral role that human beings with mental problems have had in their recovery, to be assumed in an interactive, lateral, and horizontal way (Dell et al., 2021).

In mental health, it is a priority to move from research to practice (Mehta et al., 2021). And to develop methods to ensure that evidence-based strategies and programs are effectively translated and used in the real world (Curran et al., 2012). These practices, methods, and transfers, require specifying nuclear components, in the first place, subsequently, go through an appropriation, to consolidate an effective strategy that achieves positive changes in people’s lives.

In this case, it has been found in this review, as core components of mutual aid groups Coping strategies, Recognition and management of emotions, Problem solving, Supportive interaction. As well as, Construction of identity, Social networks, and Active agency. The application of these components has been associated with greater benefits, that should be considered in the implementation of mental health plans, programs, strategies, or policies.

The components of this type of interaction assume that people who have similar experiences can relate better and, consequently, can offer more authentic empathy and validation. Where reciprocity appears as an integral part of this process, unlike the support of expert workers. These differences mean that socioemotional support is frequently accompanied by instrumental support to achieve a desired social or personal change (Repper & Carter, 2011). MAGs offer much potential benefits, but their ability to execute will depend on local realities, including a differentiated approach, displacement to groups, and skills in handling technological tools (Edwards & Imrie, 2008 ; Gugerty at al. 2019; Powell & Perron, 2010 ).

These findings represent a contribution to the methodology in the development of the MAG and perhaps other group strategies for mental health. Likewise, it is better oriented towards minimum expected or desirable results, although many of these components may not be differentiated as part of the process or the result. Loreto & Silva (2004) mention:

The question remains: Where do the processes end and the results begin? We think that this happens due to a difficulty in defining what a process and a result are. Because both are not intrinsically or essentially different, but rather constitute part of a future in which the definition of each one is relative. (p.31)

Similarly, this review also reaffirms that implementation in mental health is more successful when the necessary infrastructure to implement, train, monitor, and evaluation of results are provided. The community is involved in the selection and evaluation of programs and practices. There is a political context that facilitates resources, to let the learning and make necessary adjustments in the implementation process (Fixsen et al., 2018 ).

References

References

Activament Catalunya Associació. (2021). Guía para los Grupos de Ayuda Mutua de salud mental en primera persona. https://www.activament.org/es/2021/guia-GAM/

Agudelo-Hernández, F., & Rojas-Andrade, R. (2021). Ciencia de la implementación y salud mental: Un dialogo urgente. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcp.2021.08.001

Ahmad, J., Hazra, A., Aruldas, K., Singh, A., & Saggurti, N. (2021). Potential of organizing unmarried adolescent girls and young women into self-help groups for a better transition to adulthood: Findings from a cross-sectional study in India. PLoS One, 16(3):e0248719. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248719

Akin, T., Baird, S., & Sanders, J. (2021). Mutual aid on WhatsApp: reflections on an online support group for new and pre-tenured faculty, Social Work with Groups. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2021.1990191

American Psychological Association-APA. (2019). Definition of “self-help group”. https://dictionary.apa.org/self-help-groups

Anderson, B. T., & García, A. (2015). Spirituality’ and ‘cultural adaptation’ in a Latino mutual aid group for substance misuse and mental health. BJPsych Bull, 39(4):191-5. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.114.048322

Avis, M., Elkan, R., Patel, S., Walker, B. A., Ankti, N., & Bell, C. (2008). Ethnicity and participation in cancer self-help groups. Psychooncology, 17(9):940-7. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1284

Baldacchino, A., & Rassool, H. (2006). The self help movement in the addiction field – Revisited. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 17(1), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/10884600500505836

Benight, C. C., Swift, E., Sanger, J., Smith, A., & Zeppelin, D. (1999). Coping self-efficacy as a mediator of distress following a natural disaster. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29 (2), 244–2464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00120.x

Bernabéu-Álvarez, C., Faus-Sanoguera, M., Lima-Serrano, M., & Lima-Rodríguez, J. (2020). Revisión sistemática: influencia de los Grupos de Ayuda Mutua sobre cuidadores familiares. Enfermería Global, 19(58), 560-590. https://doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.392181

Bjerke, T. N. (2012). Self-help groups for substance addiction. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 10;132(1), 54-6. https://doi.org/10.4045/tidsskr.11.0800

Borkman, T. (1999). Understanding self help/mutual aid: Experiential learning in the commons. New Jersey: Rutgers.

Brown, L. D., Shepherd, M. D., Wituk, S. A., & Meissen, G. (2008). Introduction to the special issue on mental health self-help. American Journal of Community Psychology, 42(1-2), 105-109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9187-7

Carlén, K., & Kylberg, E. (2021). An intervention of sustainable weight change: Influence of self-help group and expectations. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 24(4), 1498-1503. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13290

Chambers, S. E., Canvin, K., Baldwin, D. S., & Sinclair, J. (2017). Identity in recovery from problematic alcohol use: A qualitative study of online mutual aid. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 174, 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.01.009

Chaudhary, S., Avis, M., & Munn-Giddings, C. (2013). Beyond the therapeutic: A Habermasian view of self-help groups’ place in the public sphere. Social Theory & Health: sth, 11(1), 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1057/sth.2012.14

Chen, A., Smart, Y., Morris-Patterson, A., & Katz, C. L. (2014). Piloting self-help groups for alcohol use disorders in Saint Vincent/Grenadines. Annals of Global Health, 80(2), 83-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2014.04.003

Cheung, C. K., & Ngai, S. S. (2016). Reducing deviance through youths’ Mutual Aid Group dynamics. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 60(1), 82–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X14548024

Chorpita, B. F., Becker, K. D., & Daleiden, E. L. (2007). Understanding the common elements of evidence-based practice: Misconceptions and clinical examples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(5), 647–652. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e318033ff71

Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E. L., & Weisz, J. R. (2005). Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research, 7(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11020-005-1962-6

Cohen, A., Raja, S., Underhill, C., Yaro, B., Dokurugu, A., DeSilva, M., & Patel, V. (2012). Sitting with others: Mental health self-help groups in northern Ghana. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 6(1),1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-6-1

Connolly, K. R., & Thase, M. E. (2012). Emerging drugs for major depressive disorder. Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs, 17, 105–126. https://doi.org/10.1517/14728214.2012.660146

Corrigan, P., Slope, N, Garcia, G., Phelan, S., Keogh, C.,& Lorraine, K. (2005). Some recovery processes in mutual-help groups for persons with mental illness; II: qualitative analysis of participant interviews. Community Mental Health Journal, 41, 721–735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-005-6429-0

Curran, G. M., Bauer, M., Mittman, B., Pyne, J. M., & Stetler, C. (2012). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical care, 50(3), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812

Davidson, L., Lawless, M. S., & Leary, F. (2005). Concepts of recovery: Competing or complementary? Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 18(6), 664-667. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.yco.0000184418.29082.0e

Dell, N. A., Long, C., & Mancini, M. A. (2021). Models of mental health recovery: An overview of systematic reviews and qualitative meta-syntheses. Psychiatric rehabilitation journal, 44(3), 238–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000444

Edwards, C., & Imrie, R. (2008). Disability and the implications of the wellbeing agenda: some reflections from the United Kingdom. Journal of Social Policy, 37 (3), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279408001943

Eley, G. (1992). Habermas Jürgen, the structural transformation of the public sphere. An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society (Cambridge, Mass.: The mit Press, 1989). Comparative Studies in Society and History, 34(1), 189-190. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417500017527

Fernandez-Jesus, M., Mao, G., Ntontis, E., Cocking, C., McTague, M., Schwarz, A., Semlyen, J., & Drury., M. (2021). More than a COVID-19 response: Sustaining Mutual Aid Groups during and beyond the pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 20(12),716202. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.716202

Fixsen, D. L., Ward, C., Blase, K., Naoom, S., Metz, A., & Louison, L. (2018). Assessing drivers’ best practices. Chapel Hill, NC: Active Implementation Research Network, https://www.activeimplementation.org.

Garland, A. F., Hawley, K. M., Brookman-Frazee, L., & Hurlburt, M. S. (2008). Identifying common elements of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children’s disruptive behavior problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(5), 505–514. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816765c2

Giarelli, G., & Spina, E. (2014). Self-help/mutual aid as active citizenship associations: A case-study of the chronically ill in Italy. Social Science and Medicine, 123, 242-249. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.034

Gona, J., Newton, C., Hartley, S., & Bunning, K. (2020). Development of self-help groups for caregivers of children with disabilities in Kilifi, Kenya: Process evaluation. African Journal of Disability, 9(1), 1-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v9i0.650

Gracía Fuster, E. (1996). ¿Por qué funcionan los grupos de autoayuda? Información Psicológica, (61), 4–11. https://www.informaciopsicologica.info/revista/article/view/961

Gugerty, M. K., Biscaye, P., & Anderson, C. L. (2019). Delivering development? Evidence on self-help groups as development intermediaries in South Asia and Africa. Development policy review: The journal of the Overseas Development Institute, 37(1), 129-151. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12381

Haslam, C., Cruwys, T., & Haslam, S. A. (2014). “The ‘we’s’ have it”: Evidence for the distinctive benefits of group engagement in enhancing cognitive health in ageing. Social Science and Medicine, 120, 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.037

Hernández Zamora, Z., Hernández Loeza, O., & Rodríguez Viveros, E. (2010). El Grupo de Ayuda como alternativa para mejorar la calidad de vida del adulto mayor. Psicología Iberoamericana, 18(2), 47-55 https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=133915921006 DOI: https://doi.org/10.48102/pi.v18i2.250

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Humphreys, K., & Rappaport, J. (1994). Researching self-help/mutual aid groups and organizations: Many roads, one journey. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 3, 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-1849(05)80096-4

James, E., Kennedy, A., Vassilev, I., Ellis, J., & Rogers, A. (2020). Mediating engagement in a social network intervention for people living with a long-term condition: A qualitative study of the role of facilitation. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 23(3), 681–690. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13048

Juárez-Ramírez, C., Treviño-Siller, S., Ruelas-González, M. G., Théodore, F., & Pelcastre-Villafuerte, B. E. (2020). Los Grupos de Ayuda Mutua como posible estrategia de apoyo emocional para personas indígenas que padecen diabetes. Salud Pública De México, 63(1), 12-20. https://doi.org/10.21149/11580

Katz, A. H. (1970). Self-help organizations and volunteer participation in social welfare. Social Work, 15 (1), 51-60. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/15.1.51

Kelly, J. F., Hoffman, L., Vilsaint, C., Weiss, R., Nierenberg, A., & Hoeppner, B. (2019). Peer support for mood disorder: Characteristics and benefits from attending the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance mutual-help organization. Journal of Affective Disorders, 255, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.05.039

Kieffer, C. H. (1984). Citizen empowerment: A developmental perspective, Prevention in Human Services, 3(1) (2-3), 9-36. https://doi.org/10.1300/J293v03n02_03

Kleinman, A. (1987). Anthropology and psychiatry. The role of culture in cross-cultural research on illness. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 151(1), 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.151.4.447

Landstad, B. J., Hedlund, M., & Kendall, E. (2020). Practicing in a person-centred environment - self-help groups in psycho-social rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1789897

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Lloyd-Evans, B., Mayo-Wilson, E. H., Bronwyn, I., Brown, H. E., Pilling, S., Johnson, S., & Kendall, T. (2014). A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of peer support for people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-39

Longden. E., Read, J., & Dillon, J. (2018). Assessing the impact and effectiveness of hearing voices network Self-help Groups. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(2), 184-188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0148-1

Loreto, M., & Silva, C. (2004). Empoderamiento: Proceso, nivel y contexto. Psykhe, 13(2), 29-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-22282004000200003

Magura, S., Cleland, C., Vogel, H., Knight, E., & Laudet, A. (2007). Effects of “dual focus” mutual aid on self-efficacy for recovery and quality of life. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 34(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-006-0091-x

Manning, V., Kelly, J., & Baker, A. (2020). The role of peer support and mutual aid in reducing harm from alcohol, drugs, and tobacco in 2020. Addictive Behaviors, 109, 106480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106480

Mao, G., Drury, J., Fernandes-Jesus, M., & Ntontis, E. (2021). How participation in COVID-19 mutual aid groups affects subjective well-being and how political identity moderates these effects. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy: ASAP, 21(1), 1082–1112. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12275

Markowitz, F. E. (2015). Involvement in mental health self-help groups and recovery. Health sociology review: the journal of the Health Section of the Australian Sociological Association, 24(2), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2015.1015149

Martin, C., Peterson, C., Robinson. R., & Sturmberg, J. (2009). Care for chronic illness in Australian general practice focus groups of chronic disease self-help groups over 10 years: Implications for chronic care systems reforms. Asia Pacific Family Medicine, 8(1), 1.https://doi.org/10.1186/1447-056X-8-1

Martínez, G., Llombart, M., Malo, E., & Garcia, D. (2021). Antecedentes feministas de los grupos de apoyo mutuo en el movimiento loco: Un análisis histórico-crítico. Salud Colectiva, 17(1),1-16. https://doi.org/10.18294/sc.2021.3274

Matusow, H., Guarino, H., Rosenblum, A., Vogel, H., Uttaro, T., Khabir, S., Rini, M., Moore, T., & Magura, S. (2013). Consumers’ experiences in dual focus mutual aid for co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 7, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.4137/SART.S11006

Mehta, K. M., Irani, L., Chaudhuri, I., Mahapatra, T., Schooley, J., Srikantiah, S., Abdalla, S., Ward, V., Carmichael, S. L., Bentley, J., Creanga, A., Wilhelm, J., Tarigopula, U. K., Bhattacharya, D., Atmavilas, Y., Nanda, P., Weng, Y., Pepper, K. T., Darmstadt, G. L., & Ananya Study Group. (2020). Health layering of self-help groups: Impacts on reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health and nutrition in Bihar, India. Journal of Global Health, 10(2), 021007. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.021007

Moos, R. H. (2008). Active ingredients of substance use-focused self-help groups. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 103(3), 387-96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02111.x

Munn-Giddings, C. (2003). Mutuality and movement: An exploration of the relationship of self help/mutual aid to social policy. Loughborough, UK: Loughborough University. https://hdl.handle.net/2134/6958

Ngai, S. S., Cheung, C. K., Mo, J., Chau, S. Y., Yu, E., Wang, L., & Tang, H. Y. (2021a). Mediating effects of emotional support reception and provision on the relationship between group interaction and psychological well-being: A study of young patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212110

Ngai, S. S., Cheung, C. K., Ng, Y. H., Shang, L., Tang, H. Y., Ngai, H. L., & Wong, K. H. (2021b). Time effects of supportive interaction and facilitator input variety on treatment adherence of young people with chronic health conditions: A dynamic mechanism in Mutual Aid Groups. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063061

Nickels, S.V., Flamenco Arvaiza, N. A., & Rojas Valle, M. S. (2016). A qualitative exploration of a family self-help mental health program in El Salvador. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 10-26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-016-0058-6

Nieto Zermeño, O. (2008). Grupo de Pares de Reflexión y Ayuda Mutua (gpram): Modelo emergente para la intervención comunitaria. Psicología Iberoamericana, 16(1), 36-43. https://doi.org/10.48102/pi.v16i1.298

O’Dwyer, E., Beascoechea-Seguí, N., & Souza, L. (2021). The amplifying effect of perceived group politicization: Effects of group perceptions and identification on anxiety and coping self-efficacy among members of UK COVID-19 mutual aid groups. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 32(3), 423-437. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2582

Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., Chisholm, D., Collins, P. Y., Cooper, J. L., Eaton, J., Herrman, H., Herzallah, M. M., Huang, Y., Jordans, M., Kleinman, A., Medina-Mora, M. E., Morgan, E., Niaz, U., Omigbodun, O., Prince, M., ...UnÜtzer, J. (2018). The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet (London, England), 392(10157), 1553–1598. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X

Patil, S., & Kokate, K. (2017). Identifying factors governing attitude of rural women towards Self-Help Groups using principal component analysis. Journal of Rural Studies, 55(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.08.003

Peters, M., Godfrey, C. M., McInerney, H., Parker., D., & Baldini Soares, C. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141-146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

Petrini, F., Graziani, E., Caputo, M. A., & Meringolo, P. (2020). Continuum between relational and therapeutic models of self-help in mental health: A qualitative approach. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(3-4), 290-304. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12399

Pistrang, N., Baker, C., & Humphreys, K. (2010). The contributions of mutual help groups for mental health problems to psychological well-being: A systematic review. In: Brown LD, Wituk S, (Eds.), Mental health self-help: Consumer and Family Initiatives (pp.61-86). Springer. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6253-9_4

Pistrang, N., Barker, C., & Humphreys, K. (2008). Mutual help groups for mental health problems: A review of effectiveness studies. American Journal of Community psychology, 42(1-2), 110–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9181-0

Powell, T., & Perron, B. E. (2010). Self-help groups and mental health/substance use agencies: The benefits of organizational exchange. Substance Use & Misuse, 45(3), 315-29. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826080903443594

Putnam, R., & Nanetti, R. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400820740

Repper, J., & Carter, T. (2011). A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 20(4), 392-411. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2011.583947

Rettie, H. C., Hogan, L. M., & Cox, W. M. (2021). Identifying the main components of substance- related addiction recovery groups. Substance Use & Misuse, 56(6), 840–847. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2021.1899228

Rosenblat, J. D., Simon, G. E., Sachs, G. S., Deetz, I., Doederlein, A., DePeralta, D., Dean M. M., & McIntyre, R. S. (2019). Treatment effectiveness and tolerability outcomes that are most important to individuals with bipolar and unipolar depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 243, 116–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.027

Rossi, P., & Tognetti Bordogna, M. (2014). Mutual help without borders? Plurality and heterogeneity of online mutual help practices for people with long-term chronic conditions, European Journal of Social Work, 17(4), 523-538. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2013.802225

Russo, C. A., Hambrick, M. M., & Owens P. L. (2007). Hospital stays related to depression, 2005, In: Project, H. C. a. U. (Ed.), Statistical Brief Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville.

Sample, L. L., Cooley, B. N., & Ten Bensel, T. (2018). Beyond circles of support: “Fearless”-an open peer-to-peer mutual support group for sex offense registrants and their family members. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(13), 4257–4277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X18758895

Seebohm, P., Chaudhary, S., Boyce, M., Elkan, R., Avis, M., & Munn-Giddings, C. (2013). The contribution of self-help/mutual aid groups to mental well-being. Health & Social Care in the Community, 21(4), 391-401. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12021

Southall, K., Jennings, M. B., Gagné, J. P., & Young, J. (2019). Reported benefits of peer support group involvement by adults with hearing loss. International Journal of Audiology, 58(1), 29-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2018.1519604

Stang, I., & Mittelmark, M. B. (2009). Learning as an empowerment process in breast cancer self-help groups. Journal of Clinical Nurse, 18(14), 2049-2057. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02320.x

Steinke, B. (2000). Rehabilitation initiatives by disability self help groups: A comparative study. International Social Security Review, 53(1), 83–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-246X.00064

Stewart, M. J. (1990). Expanding theoretical conceptualizations of self-help groups. Social Science and Medicine, 31(1), 1057-1066. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(90)90119-D

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colqu- houn, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., ... Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Trojan, A., Nickel, S., & Kofahl, C. (2016). Implementing ‘self-help friendliness’ in German hospitals: A longitudinal study. Health Promotion International, 31(2), 303–313. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau103

Valencia Murcia, F., & Correa García, A. (2006). Ayuda mutua e intercambio: hacia una aproximación conceptual. Revista Guillermo de Ockham, 4(2), 71-82. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=105316853006

Weaver, R. K., & Salem, D. A. (2005). Mutual-help groups and recovery: The influence of settings on participants’ experience of recovery. In: Ralph, R. O., Corrigan, P. W. (Eds). Recovery and mental illness: Consumer visions and research paradigms. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2005. p. 173-205

Wijekoon. S., Wilson, W., Gowan, N., Ferreira, L., Phadke, C., Udler, E., & Bontempo, T. (2020). Experiences of occupational performance in survivors of stroke attending peer support groups. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D’ergotherapie, 8. 87(3),173-181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417420905707

Wilson, J. (1994). Self help groups and professionals york: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Social Care Research, 60. World Health Organization. (2016). mhGAP intervention guide. Geneva: who Press. https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/28418/9789275319017_spa.pdf

World Health Organization-who- & Pan American Health Organization - paho-. (1990). Declaración de Caracas. https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2008/Declaracion_de_Caracas.pdf

Yip, K. S. A. (2002). A mutual-aid group for psychiatric rehabilitation of mental ex-patients in Hong Kong. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 48(4), 253-65. https://doi.org/10.1177/002076402128783299

Zimmerman, M. (2000). Empowerment theory. In J. Rappaport & amp; E. Seidman (Eds). Handbook of community psychology (pp. 43-63). New York, NY: Kluwer. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4193-6_2

Zimmerman, M. A., & Rappaport, J. (1988). Citizen participation, perceived control, and psychological empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 16(5), 725-750. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00930023

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Felipe Agudelo-Hernández, Marcela Guapacha-Montoya, Rodrigo Rojas-Andrade. (2024). Mutual Aid Groups for Loneliness, Psychosocial Disability, and Continuity of Care. Community Mental Health Journal, 60(3), p.608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-023-01216-9.

2. Andrés Felipe Agudelo Hernández, Ana Belén Giraldo Alvarez. (2024). Coffee as an axis of recovery: cooperativism and mental health. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 28(5), p.473. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-12-2022-0087.

3. Felipe Agudelo-Hernández, Luisa Fernanda Cardona Porras, Ana Belén Giraldo Álvarez. (2024). Declaration of the Town Square: The Urgency of Speaking as One. Journal of Human Rights Practice, 16(2), p.624. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhuman/huae002.

4. Andrés Camilo Delgado Reyes, Valentina Gonzales Carreño, María Teresa Carreño Bustante. (2023). Atención en salud mental en víctimas del conflicto armado: una reflexión crítica entre lo escrito y lo realizado. Psicoespacios, 17(31), p.1. https://doi.org/10.25057/21452776.1573.

5. Jesús Eduardo Marulanda López, Felipe Agudelo Hernández, Ana Belén Giraldo Alvarez. (2024). Rehabilitación basada en comunidad para la salud mental. Revista Salud Bosque, 13(2) https://doi.org/10.18270/rsb.v13i2.4461.

6. Andrés Felipe Agudelo Hernandez, Rodrigo Rojas Andrade, Marcela Guapacha Montoya, Ana Belén Giraldo Álvarez. (2024). Componentes nucleares y efectividad de los grupos de ayuda mutua: Una revisión sistemática. Tesis Psicológica, 18(2) https://doi.org/10.37511/tesis.v18n2a5.

7. Felipe Agudelo-Hernández, Marcela Guapacha Montoya. (2024). Poetry in youth mutual aid groups for recovery in rural and semi-urban environments. Arts & Health, 16(3), p.340. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2023.2273490.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The RCP is published under the Creative Commons license and can be copied and reproduced according to the conditions of this license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5). RCP articles are available online at https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/psicologia/issue/archive. If you would like to subscribe to the RCP as reader, please go to https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/psicologia/information/readers and follow the instructions mentioned in the webpage. Additionally, a limited number of print journals are available upon request. To request print copies, please email revpsico_fchbog@unal.edu.co.