ESCALA DE PRÁCTICAS PARENTALES PARA NIÑOS

PARENTAL PRACTICES SCALE FOR CHILDREN

Palabras clave:

Acceptance, cross-validation, childrearing, psychopathology, negative affect, aceptación, validación cruzada, crianza, psicopatología, afecto negativo, aceitação, validação cruzada, criação, afeto negativo (es)Confirmatory factor analysis conducted in a sample of 706 children 7 to 16 years of age, 354 girls and 352 boys, revealed a 5-factor solution (Rejection, Corporal Punishment, Support, Responsiveness, Warmth). Results supported the measurement model of the Parental Practices Scale for Children, which evaluates children's perception of parental practices associated to offspring emotional adjustment. This finding was replicated in a second study (N=233, 126 girls and 107 boys). The measure demonstrated good internal consistency, and was further supported by convergent validity with an instrument built with a similar objective. The measurement model supported by results of both studies is consistent with previous findings.

Parental Practices Scale for Children*

Escala de Prácticas Parentales para Niños

Escala de Práticas Parentais para Crianças

Laura Hernández-Guzmán

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México, D.F.

Manuel González Montesinos

Universidad de Sonora, Sonora, México

Graciela Bermúdez-Ornelas

Miguel-Ángel Freyre

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México, D.F.

Raúl Alcázar Olán

Universidad Iberoamericana, Puebla, México

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Laura Hernández-Guzmán, e-mail: lher@unam.mx.

Department of Psychology, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, C.P. 04510, México, D.F.

Artículo de investigación científica

Recibido: 7 de mayo de 2012 - Aceptado: 19 marzo de 2013

Abstract

Confirmatory factor analysis conducted in a sample of 706 children 7 to 16 years of age, 354 girls and 352 boys, revealed a 5-factor solution (Rejection, Corporal Punishment, Support, Responsiveness, Warmth). Results supported the measurement model of the Parental Practices Scale for Children, which evaluates children's perception of parental practices associated to offspring emotional adjustment. This finding was replicated in a second study (N=233, 126 girls and 107 boys). The measure demonstrated good internal consistency, and was further supported by convergent validity with an instrument built with a similar objective. The measurement model supported by results of both studies is consistent with previous findings.

Keywords: acceptance, cross-validation, childrearing, psychopathology, negative affect

Resumen

El análisis factorial confirmatorio realizado en una muestra de 706 niños entre 7 y 16 años, 354 niñas y 352 niños, reveló una solución de 5 factores (Rechazo, Castigo Corporal, Apoyo, Receptividad y Calidez). Los resultados apoyaron el modelo de medida de la Escala de Prácticas Parentales para Niños que evalúa su percepción respecto a dichas prácticas asociadas con el ajuste emocional infantil. Este hallazgo se repitió en un segundo estudio (N=233, 126 niñas y 107 niños). La medida mostró buena coherencia interna, así como validez convergente con un instrumento construido para un objetivo similar. El modelo de medida, apoyado por los resultados de ambos estudios, es coherente con hallazgos previos.

Palabras clave: aceptación, validación cruzada, crianza, psicopatología, afecto negativo.

Resumo

A análise fatorial confirmatória realizada em uma amostra de 706 crianças entre 7 e 16 anos (354 meninas e 352 meninos) revelou uma solução de 5 fatores (Recusa, Castigo Corporal, Apoio, Receptividade e Calidez). Os resultados apoiaram o modelo de medida da Escala de Práticas Parentais para Crianças que avalia sua percepção a respeito dessas práticas associadas ao ajuste emocional infantil. Esta descoberta se repetiu em um segundo estudo (N=233, 126 meninas e 107 meninos). A medida mostrou boa coerência interna, assim como validade convergente com um instrumento construído para um objetivo similar. O modelo de medida, apoiado pelos resultados de ambos os estudos é coerente com descobertas prévias.

Palavras-chave: aceitação, validação cruzada, criação, psicopatologia, afeto negativo.

Traditionally, the most accepted perspective used to understand the effects of parenting on children's outcomes has been Baumrind´s typology (1971), which mainly deals with parents´ style to discipline their children. However, Darling and Steinberg (1993) have questioned it on the basis of the contradictory effects of some parenting styles across cultures. They put forward an important distinction between parenting styles and parenting practices. Whereas a parenting style is considered a general constellation of attitudes representing the context in which parental behaviors are expressed, parenting practices are the specific behaviors.

Interest in parenting styles and parental practices lies mainly in child outcome, in which emotional expression is an important element bearing responsibility for offspring emotional stability. It stands to reason that research findings have suggested that parenting practices, rather than parenting styles, better predict children outcomes (Carlo, McGinley, Hayes, Batenhorst, & Wilkinson, 2007).

Indeed, parental practices account for research findings on the influence of the emotions expressed during parent-child relationships on offspring's emotional adjustment. When typical authoritarian parents show love and warmth, instead of communicating negative emotions, the outcomes associated with the authoritarian parenting style do not occur (Rudy & Grusec, 2006) or decrease (Gunnoe, Hetherington, & Reiss, 2006).

These findings draw attention to research exploring the role played by parental practices on emotional self-regulation of children, which has been understood as children's capacity to understand their emotions and those of others, and adapt their behavior to environmental demands. According to Kring and Sloan (2009), emotional self-regulation also involves the strategies used by the person to change the occurrence, experience, intensity and expression of emotions. According to Dennis (2006) and Frost, Wortham, and Reifel (2008), the quality of emotions involved in parent-child interactions influences the capacity of children to regulate their own emotions.

Concerning children's inability to process emotions, findings suggest that exposure to adverse parent-child transactions is closely aligned with a general affective dispositional dimension reflecting aversive mood states, such as anxiety, depression, sadness, nervousness, and anger, called negative affect (Clark & Watson, 1991). Negative affect apparently plays an important role in the development of psychopathology, as some parental behaviors expressing it, such as rejection and corporal punishment and the absence of warmth and support, have been systematically associated to emotion processing deficits and psychological maladjustment (Baker & Hoerger, 2012; Barber, Stolz, & Olsen, 2005; Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Eggum, 2010), inability to adaptively respond to life challenges and adversities (Appleyard, Egeland, & Sroufe, 2007; Brown & Whiteside, 2008; Dietz, et al., 2008), and even to medical conditions (Rogosch, Cicchetti, & Toth, 2004). In fact, 75% of diagnostic categories described by DSM-IV involve problematic emotional regulation (Campbell-Sills & Barlow, 2007; Werner & Gross, 2010).

Expressed criticism, disapproval and negative affect involving anger, neglect, hostility and verbal abuse are parental practices used to define rejection (Gar & Hudson, 2009; Johnson, Cohen, Chen, Kasen, & Brook, 2006). Also affecting self-regulation of children, rejection predicts adjustment problems and psychopathology (Baker & Hoerger, 2012), and low self-concept (Cournoyer, Sethi, & Cordero, 2005). Negative affect involved in parental rejection has been shown as mediator of the parent personality – externalizing problems relationship (Latzman, Elkovitch, & Clark, 2009; Oliver, Guerin, & Coffman, 2009) and of the association between parental depression and offspring depression (Wilson & Durbin, 2009).

Corporal punishment as a means of expressing negative affect has generated its own voluminous literature. Punishment has been directly associated to children's emotional dysfunction (Amato & Fowler, 2002; Gámez-Guadix, Straus, Carrobles, Muñoz-Rivas, & Almendros, 2010). These findings are well in line with research on the mediating role of emotional self-regulation between punishment and some outcomes, such as child aggression (Chang, Schwartz, Dodge, & McBride-Chang, 2003) or adolescent anxiety and depression (Tortella-Feliu, Balle, & Sesé, 2010). Parental punishment elicits negative affect in children, damaging their emotional health (Buckholdt, Parra, & Jobe-Shields, 2009). Aggression, peer rejection, delinquency, anxiety, depression and suicide ideation are listed among its long-term, consistent and devastating repercussions (Smith, 2006).

Additionally, Carlo, Crockett, Randall, and Roesch (2007) have criticized the main focus of research on those parental practices aimed at disciplining children's transgressions, they emphasize instead the important role of practices associated with prosocial behaviors. According to Rohner (2001), parental practices can be conceptualized within the context of parental acceptance-rejection theory (PARTheory), which suggests a bipolar dimension of parental warmth, with parental acceptance at the positive end of the continuum, involving love, affection, care, comfort, support, or nurturance, and parental rejection at the negative end, representing their absence or withdrawal. A parent could then present behaviors moving within a single continuum with positive affect at one extreme and negative affect at the other. Extreme cases of parental practices primarily leaning to the negative affect end would have deleterious consequences on offspring's functioning.

The aim of several studies has been to specifically identify parental factors conveying positive affect and its influence on offspring's adjustment. Positive emotions involved in parental warmth, responsiveness and support have been linked to the emotional health of their children (Ciairano, Kliewer, Bonino, & Bosma, 2008; Wilson & Durbin, 2009). Responsive parents promote self-regulation of negative affect in their children (Davidov & Grusec, 2006), which is consistent with Johnson et al.'s (2006) findings that those parents who transmit positive affect and warmth prevent the short and long-term occurrence of serious disorders in their children. A meta-analysis of 50 international research articles found that parental responsiveness benefits children's psychosocial development and their physical and psychological health (Eshel, Daelmans, Cabral, & Martines, 2006).

Also, support provided by parents or other agents has been conceptualized as the emotional and instrumental assistance that promotes well-being (Barber et al., 2005; Thompson & Ontai, 2000), fosters children's self-esteem and cognitive development (Collins & Steinberg, 2006), and predicts proactive social interaction in youth (Carlo, McGinley, et al., 2007). Quite the opposite, deficits in parental support have predicted depressive symptoms (Stice, Ragan, & Randall, 2004).

Parents expressing mainly negative affect and lack of positive affect influence the rate at which their children also express negative affect (Kim, Conger, Lorenz, & Elder, 2001), which jeopardizes their emotional adjustment. One promising model of parenting practices should then involve rejection and corporal punishment, conveying negative affect, as well as those expressing positive affect: warmth, responsiveness and support.

Instruments measuring parenting have been traditionally focused on Baumrind's typology (e.g., Aguilar, Sarmiento, Valencia, & Romero, 2007), dimensions predicting aggressive behavior in children (Elgar, Waschbusch, Dadds, & Sigvaldason, 2007; Essau, Sasagawa, & Frick, 2006; Hawes & Dadds, 2006) or parental selective attention to certain child behavior and its frequency (Mowder & Sanders, 2008). Other instruments measuring parental practices do not cover the five-dimension structure suggested by research literature or are directed to adolescents (Carlo, McGinley, et al., 2007; Castro, Toro, Van der Ende, & Arrindell, 1993; Markus, Lindhout, Boer, Hoogendijk, & Arrindell, 2003; Rohner, 2001; Schaefer, 1965).

EPP-N or Escala de Prácticas Parentales para Niños (Parental Practices Scale for Children) is an instrument in Spanish comprising the five correlated but conceptually distinct factors revealed by research literature: rejection, corporal punishment, warmth, responsiveness and support, associated to children's emotional adjustment. This instrument explores parenting practices from the perspective of the children, as the best way to predict future adjustment is on the basis of children's perception (Barry, Frick, & Grafeman, 2008; Schaefer, 1965). The preliminary pool of 120 items, based on extensive and successive reviews of the literature on parenting, was submitted to content validation and factor analysis, deriving in a decrease in the number of items to 87 (Ortega, 1994). After a number of successive studies, in which items were removed from the measure if they did not have factor loadings that were ≥.40, in 2003 a principal component analysis of the remaining 33-item structure was performed in a sample of 1,681 participants, suggesting a five-factor structure (Rejection, Corporal Punishment, Warmth, Responsiveness and Support; Cronbach's alpha=.90; Hernández-Guzmán et al., 2003). Further exploratory factor analysis found the same five-factor structure (Bentler's c2[df=528, p=.00]=7118.11; KMO=.91) and reduced it to 27 items. Confirmatory factor analysis of its factor structure could provide additional evidence concerning the measurement model of parental practices associated to emotional expression.

It is hypothesized that a conceptually sound measure of parenting should identify those five dimensions revealed by research literature. Furthermore, it is proposed that a second study with an independent sample will replicate the results of the first study. In addition, psychometric data of the instrument, reliability and concurrent validity with an instrument measuring some parental practices (EMBU-C) are explored.

Study 1

Method

Participants

Seven hundred and six children, 354 girls and 352 boys, between 7 and 16 years of age (mean 9.73 years, ±1.53), randomly drawn from five public elementary schools located in four different low to middle socioeconomic level geographical areas of Mexico City, participated in the study.

Instruments

Parental Practices Scale for Children (Escala de Prácticas Parentales para Niños). The EPP-N (Hernández-Guzmán et al., 2003) contains 27 items grouped in five dimensions, answered by children: Rejection composed of 7 items, punishment and responsiveness, each composed of 6 items, and warmth and support, each composed of 4 items. Each item is rated on a five-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Although the scale was designed to report on both father and mother, in the present study, children informed only about their mother.

Procedure

Following signed parental consent, participants completed the EPP-N during school hours in their classrooms supervised by undergraduate psychology students and were ensured confidentiality. After responding to the scale, an undergraduate student made sure that each child had completed all items. The child received a small gift for participating in the study.

Data Analysis

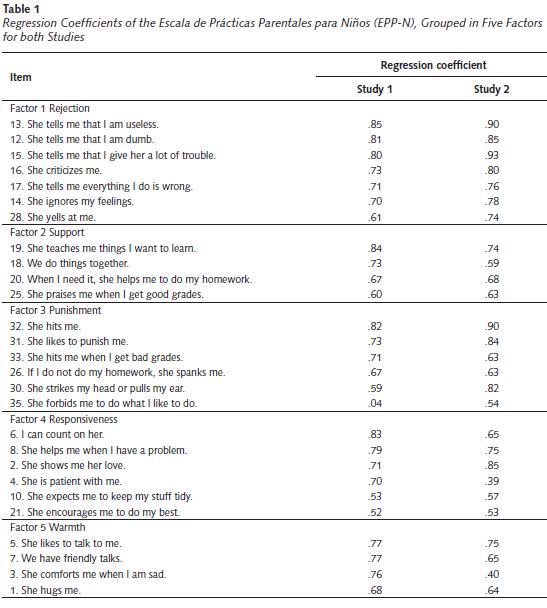

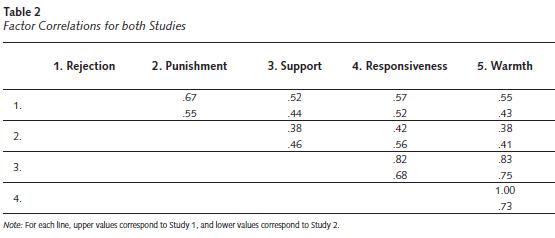

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to examine the goodness of fit of the EPP-N to a five-factor structure consistent with the model derived from research findings (see Tables 1 and 2). The LISREL 8.8 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2006) structural equation modeling was utilized for this purpose.

For model fit evaluation, normed chi-square, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Residual, (SRMR), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Relative Fit Index (RFI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), and Critical N (CN) were reported. According to conventional criteria, a good fit would be indicated by CMIN<5, RMSEA<0.05 (Byrne, 2001), SRMR≤0.08, NFI>.90, NNFI>.90, CFI>.90 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2005), IFI>.90 (Bollen, 1989), RFI>.90, and CN≤ n.

Results

Although CFA of the hypothesized five-factor theoretical model showed a significant standard chi-square (df=314, p=.00)=527.23, a good fit was revealed with all indices falling within acceptable ranges: χ²/df =1.68, RMSEA=0.031 (90% CI[0.026, 0.036], p< .05), SRMR=0.061, NFI=.98, NNFI=.99, CFI=.99, IFI=.99, RFI=.98. GFI, which indicates the proportion of variance explained, was .83. AGFI was .80. In addition, CN was 502.74, indicating that n=708 represents an adequate sample size.

Study 2

With an independent sample of children, Study 2 sought to explore the replicability of the five-factor model obtained in Study 1. A second aim was to further evaluate the internal consistency of the EPP-N and its concurrent validity based on its correlation with the EMBU-C.

Method

Participants

Two hundred thirty three children (126 girls and 107 boys), whose ages ranged from 6 to 13 years old (M=8.54; SD=1.75), represented the total population of children enrolled in a public elementary school located in a low to middle socioeconomic level area of Mexico City. Informed consent from parents was previously obtained.

Instruments

Parental Practices Scale for Children (Escala de Prácticas Parentales para Niños). EPP-N was described in Study 1.

EMBU-C. The Castro et al.'s (1993) simplified version of EMBU-C is a 40-item self-report instrument, which measures four types of parenting practices: emotional warmth, rejection, overprotection and favoring subject, as perceived by the child. The original EMBU was comprised of 81 items (Perris, Jacobsson, Lindström, von Knorring, & Perris, 1980). In Castro et al.'s EMBU simplified version, the four-factor structure explained 25% of the total variance of mothers' rearing behaviors. In the present study, the scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=.73).

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Results from the second study also revealed a good fit of the five-factor model. The model of 27 items distributed in five correlated factors was confirmed (see Tables 1 and 2). Standard chi-square (df=314)=357.98 was statistically significant (p=.04), however, the normed chi-square was 1.14. RMSEA showed again a good fit=.025 (90% CI [0.004, 0.036], p<.05). SRMR was 0.064. NFI and RFI were .96. NNFI was .99. CFI was 1.00, as well as IFI. GFI was .80, informing about the proportion of variance explained. AGFI was .76. Finally, CN was 244.17, indicating that n=233 was rather close to the ideal sample size needed to test this model. Table 1 shows regression coefficients for both Studies.

Internal Consistency

Cronbach's alpha of EPP-N was .90. Internal consistency of individual factors was .89 for Rejection, .66 for Support, .84 for Punishment, .71 for Responsiveness and .61 for Warmth.

Concurrent Validity

Concurrent validity can be assessed by comparing scores on the new scale with an established measure of the same or similar construct. Pearson correlation between EPP-N and EMBU-C was .70 (p< .00). Also, correlations between EMBU-C and each of the five factors of EPP-N were statistically significant: .56 in relation to Rejection, .50 to Support, .48 to Punishment, .53 to Responsiveness and .47 to Warmth.

Discussion

Two studies were conducted to test a five-factor structure of parenting practices as perceived by children. In addition, psychometric data of the EPP-N, reliability and concurrent validity with EMBU-C, were assessed.

Results provide evidence for the hypothesis that the EPP-N comprises five correlated but distinct dimensions of parental practices: Punishment and Rejection, which involve negative affect, and Warmth, Support and Responsiveness, expressing positive affect. The five-factor model showed acceptable model fits.

Replication of the model in an independent sample further validates the results of Study 1. The 5-factor structure of the EPP-N was highly consistent across both samples. The structure and contents of the EPP-N items are consistent with the model suggested by research literature, and similar to a 5-factor solution reported earlier (Hernández-Guzmán et al., 2003).

The Rejection factor contained items characterized by criticism, disapproval, yelling, neglect and anger. Items loading in the Punishment factor depicted behaviors such as hitting, ear pulling and suppression of privileges. Research literature has consistently related rejection and punishment to negative affect and emotional dysfunction. A meta-analysis conducted by Repetti, Taylor, and Seeman (2002) concluded that negative emotionally charged, conflictive transactions within the family, such as yelling or corporal punishment, compromise children's ability to process their own emotions. Difficulty to regulate emotional responses to stressful situations has been linked to biological stress disrupting sympathetic-adrenomedullary and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical functioning.

Children whose parents primarily communicate rejection and disapproval will not discern what is expected of them and will not learn positive emotions. From a neuropsychological perspective, while investigating executive attention in infants, Posner and Rothbart (2010) have suggested that the information received by the brain on the value of reward and of pain or punishment, associated to parenting practices, is crucial for children's self-regulation of thoughts and emotions. They point to dopamine as the neuromodulator involved in reward and punishment pathways.

Conversely, the Support factor showed content communicating positive reinforcement and availability. Items in the Responsiveness factor represented expectancies of responsibility, empathy and positive affect. Finally, items loading in the Warmth factor reflected friendship, closeness and warmth. Contrasting with Baumrind's typologies, referred to disciplinary styles, the present findings support those dimensions involved in parental practices relevant to emotional expression and adjustment.

Results of the present study support Carlo, McGinley, et al.'s (2007) contention that the study of parental practices should include not only disciplinary actions, but also practices associated with prosocial behaviors. It also contributes to a conceptualization of parental practices running along a continuum with positive affect at one extreme and negative affect at the other end. Positive associations among the five dimensions revealed by present results support the notion that a parent can show parental practices conveying negative affect, as well those communicating positive affect as part of parent-child exchanges.

The scale as a whole demonstrated good estimates of internal consistency. According to Hinton (2004), an internal consistency of .90 is considered excellent. Internal consistency of two factors, Warmth (.61) and Support (.66), were not satisfactory (Nunnally, 1978). As number of items increase, Cronbach's alpha also increases. This could explain the low coefficients found for Warmth and Support, composed of 4 items each. Future research should explore the possibility of adding items to those two dimensions.

Concerning concurrent validity, the overall scale and the individual factors correlated with a related construct in the theoretically expected direction, providing evidence of concurrent validity.

This study is not exempt from limitations. Results may not generalize to other populations since the sample was made up of school children from low to middle income geographical areas of Mexico City. The five-factor model should be replicated in rural children and adolescent populations. The temporal stability of EPP-N remains to be determined, since test-retest reliability was not investigated. More research is needed to provide additional psychometric information on the scale. Also, the perfect correlation between Responsiveness and Warmth suggests that both dimensions measure the same construct, which should be investigated in future studies.

The findings of the present study stimulate future research regarding the effects of parenting practices on emotional self-regulation of children and its long-term consequences. The role of negative affect as a construct explaining psychopathology can be further investigated with the use of EPP-N. In spite of the limitations noted, this refined version of EPP-N is useful for research and as a screening measure of risk and protective factors associated to offspring emotional adjustment.

Notas

*This research project was funded with resources allocated to the PAPIIT IN305512 project of the General Directorate for Academic Personnel of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

References

Aguilar, J., Sarmiento, C., Valencia, A., & Romero, P. (2007). La autoestima y sus relaciones con los estilos de crianza, las percepciones parentales y la motivación escolar [Self-esteem and its relationship with rearing styles, parental perceptions and scholar motivation]. In J. Aguilar, A. Valencia, & C. Sarmiento (Dirs.), Relaciones familiares y ajuste personal, escolar y social en la adolescencia. Investigaciones entre estudiantes de escuelas públicas [Familiar relationships and personal, scholar and social adjustment in adolescence. Researches in public school students] (pp. 125-138). México, D.F.: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Amato, P. R. & Fowler, F. (2002). Parenting practices, child adjustment, and family diversity. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 703-716. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00703.x.

Appleyard, K., Egeland, B., & Sroufe, L. A. (2007). Direct social support for young high risk children: Relations with behavioral and emotional outcomes across time. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 443-457. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9102-y.

Baker, C. N. & Hoerger, M. (2012). Parental child rearing strategies influence self-regulation, socio-emotional adjustment and psychopathology in early adulthood: Evidence from a retrospective cohort study. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 800-805.doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.034.

Barber, B. K., Stolz, H. E., & Olsen, J. A. (2005). Parental support, psychological control and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture and method. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 70, 1-37.

Barry, C. T., Frick, P. J. R., & Grafeman, J. (2008). Child versus parent reports of parenting practices. Implication for the conceptualization of child behavior problems. Assessment, 15, 294-303. doi: 10.1177/1073191107312212.

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monographs, 4 (1, pt. 2), 1-103. doi: 10.1037/h0030372.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Brown, A. M. & Whiteside, S. P. (2008). Relations among perceived parental rearing behaviors, attachment style, and worry in anxious children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 263-272. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.002.

Buckholdt, K. E., Parra, G. R., & Jobe-Shields, L. S. (2009). Emotion regulation as a mediator of the relation between emotion socialization and deliberate self-harm. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79, 482-490. doi: 10.1037/a0016735.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Mahwah, N.J.: Laurence Erlbaum Associates.

Campbell-Sills, L. & Barlow, D. H. (2007). Incorporating emotion regulation into conceptualizations and treatments of anxiety and mood disorders. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, N.Y.: Guilford Press.

Carlo, G., Crockett, L. J., Randall, B. A., & Roesch, S. C. (2007). A latent growth curve analysis of prosocial behavior among rural adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17 (2), 301-324.

Carlo, G., McGinley, M., Hayes, R., Batenhorst, C., & Wilkinson, J. (2007). Parenting styles or practices? Parenting sympathy, and prosocial behaviors among adolescents. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 168, 147-176. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.168.2.147-176.

Castro, J., Toro, J., Van der Ende, J., & Arrindell, W. A. (1993). Exploring the feasability of assessing perceived parental rearing styles in Spanish children with the EMBU. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 39, 47-57.

Chang, L., Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., & McBride-Chang, K. (2003). Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 598-606. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598.

Ciairano, S., Kliewer, W., Bonino, S., & Bosma, H. A. (2008). Parenting and adolescent well-being in two European countries. Adolescence, 43, 99-117.

Clark, L. A. & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 316-336.

Collins, W. A. & Steinberg, L. (2006). Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In W. Damon & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Socio-emotional process (Vol. 4, pp. 1003-1067). New York: Wiley.

Cournoyer, D. E., Sethi, R., & Cordero, A. (2005). Perceptions of parental acceptance-rejection and self-concepts among Ukrainian university students. Ethos, 33, 335-346. doi: 10.1525/eth.2005.33.3.335.

Darling, N. & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 487-496.

Davidov, M. & Grusec, J. E. (2006). Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Development, 77, 44-58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00855.x.

Dennis, T. (2006). Emotional self-regulation in preschoolers: The interplay of child approach reactivity, parenting, and control capacities. Developmental Psychology, 42, 84-97. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.84.

Dietz, L. J., Birmaher, B., Williamson, D. E., Silk, J. S., Dahl, R. E., Axelson, D. A., ... & Ryan, N. D. (2008). Mother-child interactions in depressed children and children at high risk and low risk for future depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 574-582. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181676595.

Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., & Eggum, N. D. (2010). Emotion related self-regulation and its relationship to children maladjustment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 495-525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131208.

Elgar, F. J., Waschbusch, D. A., Dadds, M. R., & Sigvaldason, N. (2007). Development and validation of the short form of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16, 243-259. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9082-5.

Eshel, N., Daelmans, B., Cabral, M., & Martines, J. (2006). Responsive parenting: Interventions and outcomes. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 84, 992-999.

Essau, C. A., Sasagawa, S., & Frick, P. J. (2006). Psychometric properties of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15, 597-616. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9036-y.

Frost, J. L., Wortham, S. C., & Reifel, S. (2008). Play and child development (pp. 140-141). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall.

Gámez-Guadix, M., Straus, M. A., Carrobles, J. A., Muñoz-Rivas, M. J., & Almendros, C. (2010). Corporal punishment and long-term behavior problems: The moderating role of positive parenting and psychological aggression. Psicothema, 22, 529-536.

Gar, N. S. & Hudson, J. L. (2009). Changes in maternal expressed emotion toward clinically anxious children following cognitive behavioral therapy. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 104, 346-352. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2009.06.001.

Gunnoe, M. L., Hetherington, E. M., & Reiss, D. (2006). Differential impact of fathers´authoritarian parenting on early adolescent adjustment in conservative protestant versus other families. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 589-596. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.589.

Hawes, D. J. & Dadds, M. R. (2006). Assessing parenting practices through parent report and direct observation during parent training. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15, 555-568. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9029-x.

Hernández-Guzmán, L., López-Olivas, M., Bermúdez-Ornelas, G., Gil, B. F., Salazar R. M., Uribe Z. Z., & Zermeño L. M. (2003). Viabilidad psicométrica de la Escala de Prácticas Parentales [Psychometric feasibility of the Parental Practices Scale]. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Psychology, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Hinton, P. R. (2004). Statistics explained. New York: Routledge.

Hu, L. T. & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118.

Johnson, J. G., Cohen, P., Chen, H., Kasen, S., & Brook, J. S. (2006). Parenting behaviors associated with risk for offspring personality disorder during adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 579-587. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.579.

Jöreskog, K. G. & Sörbom, D. (2006). LISREL 8.8 for Windows [Computer software]. Skokie, IL, U.S.A.: Scientific Software International.

Kim, K. J., Conger, R. D., Lorenz, F. O., & Elder, G. H. (2001). Parent-adolescent reciprocity in negative affect and its relation to early adult social development. Developmental Psychopathology, 37, 775-790.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York, N.Y.: The Guilford Press.

Kring, A. M. & Sloan, D. S. (Eds.). (2009). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment. New York: Guilford Press.

Latzman, R. D., Elkovitch, N., & Clark, L. A. (2009). Predicting parenting practices from maternal and adolescent sons' personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 847-855. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.05.004.

Markus, M. T., Lindhout, I. E., Boer, F., Hoogendijk, T. H. G., & Arrindell, W. A. (2003). Factors of perceived parental rearing styles: The EMBU-C examined in a sample of Dutch primary school children. Personality & Individual Differences, 34, 503-519. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00090-9.

Mowder, B. A. & Sanders, M. (2008). Parent Behavior Importance and Parent Behavior Frequency Questionnaires: Psychometric characteristics. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 17, 675-688. doi: 10.1007/s10826-007-9181-y.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Oliver, P. H., Guerin, D. W., & Coffman, J. K. (2009). Big five parental personality traits, parenting behaviors, and adolescent behavior problems: A mediation model. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 631-636. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.05.026.

Ortega, R. M. S. (1994). Influencia de los estilos de crianza maternos en el autoconcepto del niño [Influence of maternal rearing styles in children´s self-concept] (Unpublished Master´s Thesis). Department of Psychology, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Perris, C., Jacobsson, L., Lindström, H., von Knorring, L., & Perris, H. (1980). Development of a new inventory for assessing memories of parental rearing behaviour. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 61, 265-274. doi: 1980.10.1111/j.1600-0447.1980.tb00581.x.

Posner, M. I. & Rothbart, M. K. (2010). Origins of executive attention. In P. A. Frensch & R. Schwarzer (Eds.), Cognition and neuropsychology. International perspectives on psychological science (Vol. 1, pp. 3-13). New York: Psychology Press.

Repetti, R. L., Taylor, S. E., & Seeman, T. E. (2002). Risky families: Family social environment and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 330-366. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.128.2.330.

Rogosch, F. A., Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (2004). Expressed emotions in multiple subsystems of the families of toddlers with depressed mothers. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 689-709. doi: 10.1017/S0954579404004730.

Rohner, R. P. (2001). Handbook for the study of parental acceptance and rejection. (Rev. ed.). Storrs, CT: Rohner Research Publications.

Rudy, D. & Grusec, J. E. (2006). Authoritarian parenting in individualist and collectivist groups: Associations with maternal emotion and cognition and children's self-esteem. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 68-78. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.68.

Schaefer, E. S. (1965). A configurational analysis of children's reports of parent behavior. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 29, 552-557. doi: 10.1037/h0022702.

Smith, A. B. (2006). The state of research on the effects of physical punishment. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 27, 114-127.

Stice, E., Ragan, J., & Randall, P. (2004). Prospective relations between social support and depression: Differential directions of effects for parent and peer support? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 155-159. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.155.

Thompson, R. A. & Ontai, L. (2000). Striving to do well what comes naturally: Social support, developmental psychopathology, and social policy. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 657-675.

Tortella-Feliu, M., Balle, M., & Sesé, A. (2010). Relationships between negative affectivity, emotion regulation, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in adolescents as examined through structural equation modeling. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24, 686-693. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.04.012.

Werner, K. & Gross, J. J. (2010). Emotion regulation and psychopathology. A conceptual framework. In A. M. Kring & D. M. Sloan (Eds.), Emotion regulation and psychopathology. A transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment (pp. 13-37). London: The Guilford Press.

Wilson, S. & Durbin, C. E. (2009). Effects of paternal depression on fathers' parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 167-180. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.007.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Visitas a la página del resumen del artículo

Descargas

Licencia

Todo el contenido de esta revista cuenta con una licencia Creative Commons “Reconocimiento, No comercial y Sin obras derivadas” Internacional 4.0. Sin embargo, si el autor desea obtener el permiso de reproducción, se evaluará cualquier solicitud de su parte.