Biological inoculation and organic amendments as strategies to improve ebony (Caesalpinia ebano) tree-seedling growth at the nursery

Inoculación biológica y enmiendas orgánicas como estrategia para mejorar el crecimiento de plántulas de ébano (Caesalpinia ebano) en etapa de vivero

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/rfna.v71n2.67392Keywords:

Compost, Nutrition availability, Organic amendments, Plant waste, Sludge sewage, Urban forestry (en)Compost, Disponibilidad de nutrientes, Enmiendas orgánicas, Residuos vegetales, Biosólido, Silvicultura urbana (es)

Recibido: 22 de septiembre de 2017; Aceptado: 7 de noviembre de 2017

ABSTRACT

An experiment was established with the aim of evaluating the effects of individual and combined addition of organic amendments and microbial inoculation on ebony (Caesalpilinia ebano) plant growth at nursery. A soil surface sample (0-20 cm) from the city of Medellín, Colombia, was transferred into plastic bags (2 kg/bag) and received three types of previously composted organic amendments (manure from domestic animals -dogs and cats (P)-, plant wastes obtained from tree felling and pruning, and grass cutting (RV) and sewage sludge from the city (B)) in two volumetric proportions (20 and 33%) and inoculum composed by the mycorrhizal fungus Rhizoglomus fasciculatum and the mineral solubilizing fungus Mortierella sp. As a reference an uninoculated-and-unamended control was included in this study. The experimental design was completely random, each treatment had 12 replicates. The results indicated that the addition of organic amendments promoted plant growth significantly. However, these effects depended on the type and dose in favor of RV. On the other hand, the inoculation with microorganisms did not have effect on plant growth. The effects were explained as a function of nutrient availability improvement in the substrate with organic amendments and apparently due to a low mycorrhizal dependence of ebony. This paper supports the alternative use of organic amendment generated in the city for improving plant nutrition and growth in urban silviculture.

Keywords:

Compost, Nutrition availability, Organic amendments, Plant waste, Sludge sewage, Urban forestry.RESUMEN

Se estableció un experimento con el objetivo de evaluar el efecto de la adición individual y combinada de enmiendas orgánicas e inoculantes microbianos sobre el crecimiento en vivero de la especie forestal ébano (Caesalpilinia ebano). Se utilizó un suelo superficial (0-20 cm) como soporte de crecimiento, este se transfirió a bolsas plásticas (2 kg/bolsa) y se adicionaron tres tipos de enmiendas orgánicas compostadas (estiércol de animales domésticos -perros y gatos (P)-, residuos vegetales generados en la ciudad a partir de talas, podas y rocerías (RV) y biosólidos de la planta de tratamientos de aguas residuales (B)) en dos proporciones volumétricas (20 y 33%) y la inoculación conjunta del hongo micorrizal Rhizoglomus fasciculatum y el hongo solubilizador de minerales Mortierella sp. Se utilizó un control no fertilizado. El diseño fue completamente al azar y cada tratamiento tuvo 12 repeticiones. Los resultados indican que las enmiendas orgánicas promovieron significativamente el crecimiento vegetal. Sin embargo, los efectos dependieron del tipo y la dosis empleada, a favor de los RV. Por otro lado, la inoculación con los microorganismos no tuvo efecto sobre el crecimiento de las plantas. Los efectos se explican en función del mejoramiento de la disponibilidad de nutrientes con las enmiendas y de la presumible baja dependencia micorrizal del ébano. Este trabajo soporta el uso alternativo de enmiendas orgánicas generadas en la ciudad para promover la nutrición y el crecimiento de plantas de silvicultura urbana.

Palabras clave:

Compost, Disponibilidad de nutrientes, Enmiendas orgánicas, Residuos vegetales, Biosólido, Silvicultura urbana.Urban forestry has become a key element for development of cities (Morales and Varón, 2006). Trees, shrubs, and garden plants provide valuable environmental services such as reducing wind speed and creating noise barriers; they also give beauty to the environment and contribute to society with biodiversity and property enhancement .They regulate as well the temperature creating microclimatic effects, reduce air pollutants and contribute to reduce crime and violence (Garvin et al., 2013), and to improve physical and mental health (Ulrich, 1984), among many other benefits.

Recent municipal administrations of Medellin have realized the importance of maintaining woodland and gardens of the city, and have allocated financial resources for its establishment and care (AMVA, 2006). One alternative for this maintenance is the use of organic waste in the city as fertilizer and plant substrate (Medina, 1997), which represents a viable option not only for the disposal of these materials, but also to prolong landfills useful life.

Unfortunately, despite their importance, there is little forestry management in the city and most of urban soil nutrients that are essential for plant growth are not found in sufficient concentrations to meet their needs (Pedrol et al., 2010). In the last three years in the city of Medellin more than 10,000 trees and shrubs, and about 15,000 garden plants have been planted; it is considered that mortality rate was approximately 20% and an estimated 10% is due to nutritional deficiencies (SMA, 2013).

Cities generate various types of organic waste such as pruning, tree felling, grass cutting, bio solids from sewage treatment plants and various types of manure as the ones generated in animal welfare centers and livestock markets, if they are not properly managed they will end up in landfills. For example, 72,900 t of waste were generated per month in 2005 in the Metropolitan Area of the Aburra Valley, 76% out of these were to the landfill of La Pradera, only about 13% were recycled; 59% of this is organic matter that is lost without being exploited (AMVA, 2006). It is expected that, as of today, organic waste generation has increased by 30%. All this without counting the 2300 t of biosolids per month from San Fernando residual water treatment plant (EPM, 2016). In addition, it is expected that another 3600 t per month are generated when the new plant in Bello comes into operations (Gualdron, 2014).

Disposing these materials prevents their use, and thus generate large volumes for final disposal that are improperly deposited in different sites, increasing pollution in cities (Cofie and Veenhuizen, 2010). An alternative is the use of these materials as fertilizer or substrate for plants Meléndez, 2003; Hernández et al., 2010). It is worth to mention that all organic amendment should be stabilized or composted in order to reduce potential risks of pathogen populations (e.g., Salmonella, Enterobacteria, etc.) (Droffner and Brinton, 1995). These kind of microorganisms can be replaced by decomposers (Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Streptomyces, Aspergillus, and Penicillum) that help to release nutrients into the soil solution for plant roots. Escobar et al., 2012).

Fertilization is one of the most important aspects in early stages of plant growth, and that is why guidelines are needed for tree seedling production, so they contribute to the reduction of mortality of planted individuals and improve the process of adaptation in planting sites (Oliet et al., 2013). This could also result in a satisfactory plant growth and increased resistance to pests and diseases (Veresoglou et al., 2013). Organic waste could be used alternatively to synthetic fertilizers traditionally used for the production of forest species in nurseries (Ostos et al., 2008). These could represent, through previous conditioning processes, environment friendly bio inputs that benefit the plant nutrition management of species used in urban forestry activities, and also prevent its disposal in landfills (Veijalainen et al., 2007). Ebony (Caesalpilinia ebano) is one of the tree species with a high potential in urban silviculture given its rapid growth, urban environment adaptability, an esthetical appeal (Arroyave et al., 2015). On the other hand, the use of microorganisms capable of solubilizing minerals and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to promote plant growth of forestry species has been recently studied with promissing results (Diez et al., 2008; Sierra et al., 2009, 2012; Moreno et al., 2016). These microorganisms act in consortium, the former help to dissolve native or applied minerals (phosphate rock, magnesium silicate, among others) improving the availability of nutrients; while mycorrhizal fungi are an extension of the root system that improves the plant's ability to extract water and nutrients from the soil (Osorio, 2018). Although the results in other tree species used in silviculture have been possitive and in some there is not responses, it is not clear if these microorganisms can promote the growth of ebony.

The hypothesis in this study was that the effect of the organic waste addition and biological inoculation with soil fungi (an arbucular mycorrhizal fungus and a mineral-solubilizing fungus) in nursery plants may be controlled by the material type and dosage. Thus, in this work the objective was to evaluate the effect of individual and combined addition of organic amendments (various types and doses) and a microbial inoculant (R. fasciculatum and Mortierella sp.) on growth of ebony (C. ebano) in the nursery, which is of interest in urban forestry programs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental location

This study was conducted at Medellin Botanical Garden (MBG) facilities (6°16'21"N and 75°33'50"W) at an altitude of 1450 m, temperature ranges between 19 and 28 oC, and mean annual precipitation is 1436 mm. Rainfall pattern is bimodal with two dry and two wet periods during the annual cycle.

Substrate

First soil horizon (A, 0-20 cm) was obtained from a site next to the MBG located in the city of Medellin (6°16'8"N and 75°35'54"W). The soil was air dried and then sterilized using Metalaxyl-M and chlorothalonil at the concentration of 1 g L-1. A subsample was taken for physico-chemical analysis in the Laboratory of Soils at the Faculty of Sciences of Universidad Nacional de Colombia sede Medellin. The results were as follows: loamy sand texture (Bouyoucos); pH 6.2 (water 1: 1), MO 1.2% (Walkley and Black), Ca, Mg and K 2.5, 7.8 y 0.1 cmolc kg-1, respectively (1M ammonium acetate); P 1 mg kg-1 (Bray II), S-SO4 2- 36 mg kg-1 (monocalcium phosphate 0.008 M); Fe, Mn, Cu and Zn 7, 1, 1 and 1 mg kg-1, respectively (Olsen-EDTA); B 0.12 mg kg-1 (hot water), N-NO3 48 mg kg-1 (0.025M aluminum sulfate), N-NH4 8 mg kg-1 (KCl 1M), ECC 10.4 (sum of exchangeable cations), Al 0.0 cmolc kg-1 (1 M KCl). Details of the method are available in Westerman (1990).

One part of sand and another of rice husk were added to every two parts of this soil sample to improve water infiltration and drainage. The substrate (soil + sand + husk) was deposited in plastic bags of 12 cm wide, 25 cm high, with capacity of 2 L.

Organic amendments

Three organic amendments composted from different sources were used: (i) dogs and cats feces (“Perrinaza") from La Perla animal welfare center (P), (ii) vegetable waste from pruning and felling, grasses and flowers cutting residues (RV), and (iii) stabilized biosolids from San Fernando residual water treatment plant (B).

Plant material

Ebony (C. ebano; Fabaceae) was evaluated as indicator plant species of importance for urban silviculture (SMA, 2015). The seeds were supplied by the nursery of the Foundation Botanical Garden of Medellin. Two seeds were planted per bag and when the seedlings reached 10 cm in height, and a month later, one of them was removed.

Inoculum

The inoculum used was a mixture of forming arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Rhizoglomus fasciculatum. Walker and Schübler (200 spores g-1) and the plant growth promoter fungus Mortierella sp. (105 CFU g-1), of recognized ability to dissolve minerals such as phosphate rock, magnesium silicate, potassium feldespate among others (Osorio, 2008; Salazar, 2017) and decompose organic matter (Alvarez et al., 2014; Tamayo, 2016). Both microorganisms were obtained from the Soil Microbiology Research Group Collection at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia sede Medellin. The mycorhizal fungus was multiplied in maize roots grown in a substrate composed by soil and sand (4:1 ratio), while Mortierella sp. was multiplied in sterile (autoclave 120 °C , 0.1 MPa, 20 min) potato-dextrose -agar (PDA) medium.

Treatments and experimental design

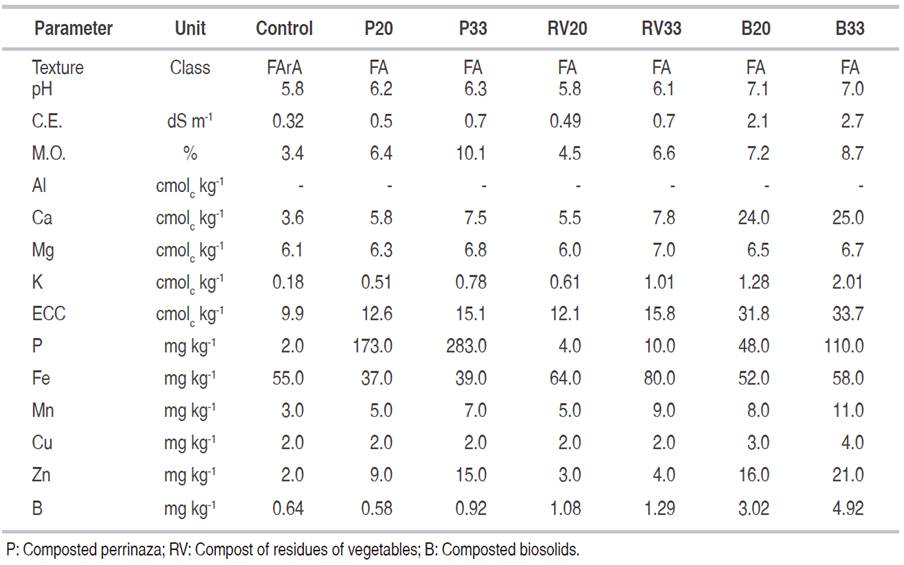

Treatments consisted of a combination of the addition or not of the three organic amendments composted in the substrate (+P, +RV +B) in two volumetric proportions (20 and 33%) and inoculation or not with the mentioned inoculum. Chemical analysis of the substrate, treated or not with organic amendments (Table 1). Furthermore, the inoculum was applied or not (+ or -) 75 g/bag dose.

Table 1: Physical-chemical properties of control soil and amended soil with organic material treatments (P, RV, B) at two concentrations (20 and 33%).

The substrate was watered as required to keep it at 50-60% of maximum water holding capacity. All nursery practices were performed in the conventional way that the nursery of the Botanical Garden has in its production.

Measured variables

After a growth period of 150 days it was measured: the plant height, leaf phosphorus content, shoot dry mass and mycorrhizal colonization (Habte and Osorio, 2001).

Data analysis

The experimental design was completely random; the treatments were a factorial arrangement of 7x2. This was, substrate without amendment (control) and three organic amendments in two proportions (+ P20 + P33 + RV20, + RV30, + B20 + B33) and the microbial inoculation with both fungi together levels (-: without and +: with). Each treatment had 12 replicates. Data were subjected to analysis of variance and mean separation (Duncan test), both with a significance level P≤0.05. Analyses were performed in STATGRAPHICS statistical software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

After the organic matter addition to the growth medium of the plants, the resulting increase in the amount of nutrients was remarkable (Table 1). For example, in the unamended control the P content was 2.0 mg kg-1 and become 283 mg kg-1 with adding composted perrinaza at 33%. The addition of these organic amendments rich in nutrients raised pH and electrical conductivity relative to unamended control; comparable increases were detected with Ca, K, and micronutrients, particularly boron.

An additional worth to mention is the corrective effect of the organic amendment on the exchangeable cation ratios in soil used as substrate (see control in Table 1), which affects plant performance (Pedrol et al., 2010). In this particular case the soil had an abundance of exchangeable Mg causing thus an unbalanced Ca/Mg ratio of 0.6. It has been recommended that the Ca/Mg should be ≥ 2.0. As a result of the treatments P20, P33, RV20 and RV33 the Ca/Mg ratio ranged 0.9-1.1, reaching a maximal value of 3.7 with the B20 and B33 treatments. The relative participation of Mg in the cation exchange capacity went from a value as high as 62% in the control to 20% with the biosolid treatments, which is near to 8-15% a range considered as adequated. These effects are comparable to those reported by several authors (Pedrol et al., 2010, Herrera et al., 2014) that found that the addition of organic amendments corrected unbalances of exchangeable cations.

It is clear that the excess of soil exchangeable Mg can inhibit the plant K uptake (Pedrol et al., 2010), even when the level of soil exchangeable K was sufficient (0.2 cmolc kg-1) as observed in the control (0.18 cmolc kg-1). Notice that in this case the Mg/K ratio in the control (34) was 10 times higher than that recommended as adequated for several plant species (Mg/K=3.3; Stover and Simmonds, 1987). In a similar way, the addition of organic amendments modified the Mg/K ratio reaching values close to that is recommended, particularly with biosolid additions (Mg/K ratios: B20=5.1, B33=3.3).

Results indicate that treatments had a significant effect on the variables studied in C. ebano, however, the effects depended on the variable (Table 2). For instance, the addition of amendment to the substrate was highly significant (P<0.0001) in height and shoot dry mass, while mycorrhizal colonization was affected only detected in the treatments with mycorrhizal inoculation. Leaf phosphorus concentration was not significantly affected by treatments. No significant effects were detected with interaction amendment x inoculum.

Table 2: Levels of significance of variance analysis for each of the analyzed variables.

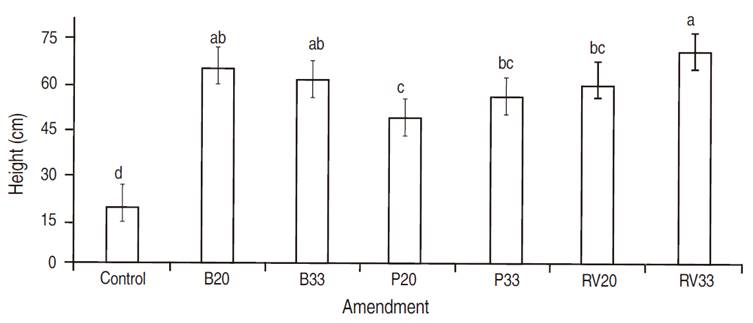

The improvement in the nutrient availability and the nutrient ratios certainly explains why plants grew better when organic amendments were applied. In fact, at the end of growth period, control plants exhibited an average height of 19.7 cm, while amendment treated plants had significantly higher heights (Figure 1). Perrinaza treated plants increased height between 2.5 to 2.8 times more than control plants (P20 and P33, respectively), but no differences between them were presented in relation to the dose. On the other hand, plants grown in substrate with bio solids had even greater heights, with increases ranging between 3.1 and 3.2 times more than the control; again, no significant differences between these values were presented. The addition of composted plant residues also generated significant effects on height, that is, with RV20 the effect was 2.9 times higher than control plants and with RV33 it was 3.5 times. There were significant differences between them.

Figure 1: Ebony plant height (C. ebano) of 150 days of age according to the addition of three composted organic amendments (P: perrinaza; B: bio solids; RV: compost plant residue) at two rates (20 and 33%) in nursery stage. Columns with different letters indicate significant differences according to Duncan test (P<0.05).

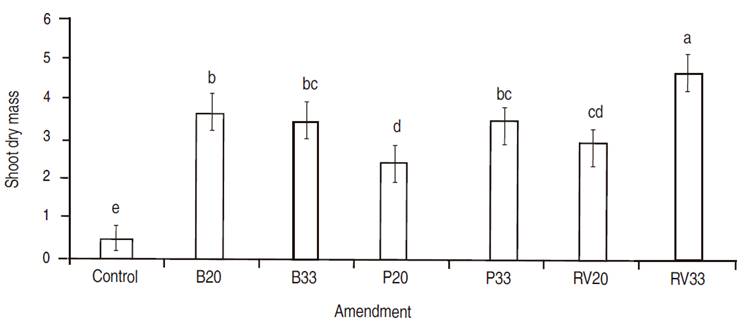

At the end of the 150 days experiment control plants had a shoot dry mass of 0.53 g. As well as height, plants belonging to treatments with amendments had significantly more shoot dry mass than the others (Figure 2). Dry mass of plants with P20 was 4.5 times higher that control plants; with P33 treatment the dry mass of plants was 6.6 times more than control and there was significant difference between them. Adding RV had a similar behavior to the perrinaza (P), but the difference in mass between RV20 and RV33 was even more evident (RV20: 5.3 and RV33: 8.8 times higher than control).

Figure 2: Shoot dry mass of 150 days old ebony plants depending on the addition of three organic composted amendments (P: perrinaza; B: bio solids; RV plant residues compost) in nursery stage. Columns with different letters indicate significant differences according to Duncan test (P<0.05).

Despite the benefits that derive from the improvement of substrate fertility with the evaluated amendments, it is clear that the best growth was not obtained with the amendment that supplied more nutrients (biosolids); perhaps this, in the used dose, generated an excess of nutrients that may have generated nutritional imbalances (see boron with very high values: 3.02-4.92 mg kg-1) (Table 1). Although treatments with bio solid amendment obtained a higher dry mass than control (6.8 and 6.9 with B33 and B20, respectively), there were no significant differences between them.

It is very likely that lower doses increase as good as those obtained with P and RV. In fact, the best results on plant dry matter were detected with 33% RV. At this dose increases in substrate fertility parameters were more moderate, particularly in P and B. In future studies it is recommended to explore the effects that lower doses may have on plant performance.

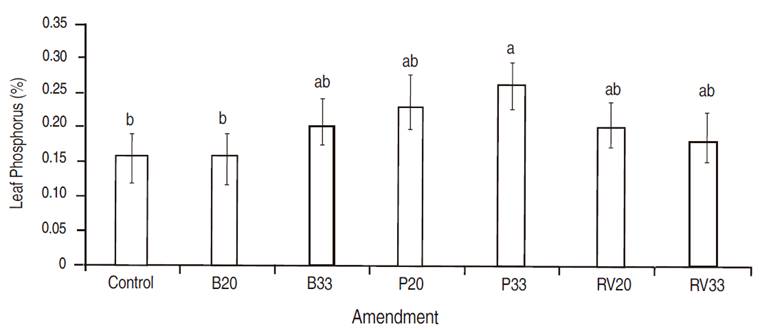

By analyzing leaf phosphorus of C. ebano with Duncan test, it can be noted that only with P33 treatment a significant increase was obtained with respect to control plants (0.17 vs. 0.25%, respectively). With other treatments (B20, B33, RV20, RV33, and P20) no significant differences with respect to control, or among themselves (Figure 3) were exhibited.

Figure 3: Leaf phosphorus in 150 days old ebony plants (C. ebano) depending on the addition of three composted organic amendments (P: perrinaza; B biosolids; RV: compost plant waste) in two proportions (20 and 33%) in nursery stage. Columns with different letters indicate significant differences according to Duncan test (P<0.05).

It is worth to mention that the value of organic amendments to improve soil fertility is not only associated to their nutrient composition, but also due to the presence of active microorganisms. They have the ability of solubilize nutrients via enzymes (proteases, phosphatases, sulfatases, etc.) and organic acids (e.g., citric acid, oxalic acid) that can maintain nutrients in available forms. It is clear that when the microorganisms are suppressed in these organic amendment their effectiveness is reduced; this has been observed when the material is treated with fumigants as reported by Osorio et al. (2002) using coffee pulp untreated or treated with Dazomet. Contrarily, the organic amendments can also carry pathogenic microorganisms that have potential hazard on human, animal and plants. However, this may be prevented when these material are treated by composting as occurred in this study with all materials (P, RV, and B).

On the other hand, mycorrhizal colonization had no significant effects between treatments, nor versus control. In addition, all levels of colonization were low. Results did not allow testing positive effects when using the inoculum. It is clear that roots had a very low mycorrhizal colonization. This may be due to at least two factors: (i) large increases in the availability of some nutrients with the addition of amendments (particularly P, and other nutrients Ca, Mg, K and B), which could inhibit the development of mycorrhizal association (Habte and Manjunath, 1987) and (ii) mycorrizal independence on C. ebano.

In the first case, with the addition of organic amendments as biosolids and perrinaza the nutrient availability in the substrate was elevated, especially P, and control treatments exhibited low nutrient content, these two being unfavorable factors for mycorrhizal activity (Osorio, 2014).

In the second case, it is important to clarify that the degree of mycorrhizal dependency of this plant species is not known yet. However, it can be stated that C. ebano is a species that, due to its morphological characteristics, type of roots, and wood density, can be placed in the group of late successional forests plants, which are less likely to form mycorrhizal association, and therefore have little or no mycorrhizal dependency (Siqueira et al., 1998). In this way, Zangaro et al. (2000) and Siqueira and Saggin-Junior (2001) have reported that plants with thick roots, dense wood, and very high capacity of store nutrients in their seeds are less dependent on the mycorrhizal association. Species of this type are common in the later succession stages and the climax species. As the successional proceeds plant species involved have less mycorrhizal dependency or are independent of this association (Siqueira et al., 1998; Zangaro et al., 2000). In contrast, plant species that correspond to initial stages of the succession (called pioneering or early successional plants) have high mycorrhizal dependency; lighter and more porous wood. For example, Acacia mangium, Leucaena leucocephala and Jacaranda mimosifolia are pioneer species and exhibit high mycorrhizal dependency (Habte and Manjunath, 1987; Habte and Soedarjo, 1996). It is worth noting that in some cases mycorrhizal association does not necessarily stimulate the growth of these pioneer species, but favors their survival (Guadarrama et al., 2004).

Regarding this point, it is known that ebony has initially a rapid growth, but then grows slowly; so, even if it has thick roots it may not need this association due to its relatively slow growth (Morales and Varón, 2006).

CONCLUSIONS

Organic amendments used in this work were effective in promoting nutrient availability in the substrate, plant nutrition and growth of C. ebano; however, it is necessary to consider the dose and type of material. Thus, these materials can be exploited and prevent improper disposal in landfills. In this way, it could determine greater efficiency in processes associated with the biogeochemical cycle.

REFERENCES

References

Alvarez C, Osorio NW, Diez MC and Montoya M. 2014. Biochemical characterization of rhizosphere microorganisms from vanilla plants with potential as biofertilizers.. Agrononomia Mesoamericana, 25(29):225-241. doi: 10.15517/am.v25i2.15426

Área Metropolitana. 2006. Plan maestro de espacios públicos verdes urbanos de la región metropolitana del valle de Aburrá. Medellín. 20 p.

Área Metropolitana. 2006. Convenio Nº 325 de 2004 Entre Área Metropolitana del Valle de Aburrá (AMVA) – Universidad de Antioquia (U. de A.) – Asociación de Ingenieros Sanitarios y Ambientales de Antioquia (AINSA), Plan de Gestión integral de Residuos Sólidos (PGIRS). Primera edición. Medellín. 66 p.

Cofie O and Veenhuizen R. 2010. Gestión de Residuos para la Recuperación de Nutrientes: Opciones y desafíos para la agricultura urbana. En: Revista Agricultura Urbana. Retrieved from http://www.actaf.co.cu/revistas/revista_au_1-18/AU23/RAU23_1_Editorial.pdf. 5 p; Consulta noviembre 2014

Davidson K, Gilpin L, Hart M, Laurent C and Miller A. 2007. The influence of the balance of inorganic and organic nitrogen on the trophic dynamics of microbial food webs. Limnology and Oceanography 52(5): 2147–2163. doi: 10.4319/lo.2007.52.5.2147

Davidson R, Gagnon D and Mauffette, H Hernandez. 1998. Early survival, growth and foliar nutrients in native Ecuadorian trees planted on degraded volcanic soil. Forest Ecology and Management 105: 1-19. doi : 10.1016/S0378-1127(97)00295-8

EPM. 2016. Plantas de tratamiento de aguas residuales, http://www.epm.com.co/site/Home/Institucional/Nuestrasplantas/Agua.aspx, consulta Noviembre 2016.

Garvin EC, Cannuscio CC and Branas CC. 2013. Greening vacant lots to reduce violent crime: a randomised controlled trial. Injury Prevention: Journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention, 19(3): 198–203. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040439

Meléndez G. 2003. Residuos orgánicos y materia orgánica del suelo. Taller de Abonos Orgánicos. Centro de Investigaciones Agronómicas (CIA), UCR, Sabanilla, 18 p.

González de C. 2002. Beneficios del Arbolado Urbano, ensayo de doctorado. CSIC (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas). España. 2002. 24 p. https://es.scribd.com/document/251891893/Beneficios-Del-Arbolado-Urbano. 24 p; Consulta julio 2014.

Gualdron Y. 2014. La megaobra que busca devolverle la vida al río Medellín, El Tiempo. http://www.eltiempo.com/colombia/medellin/planta-de-aguas-residuales-de-bello/14404423, Consulta Noviembre 2016.

Habte M and Osorio NW. 2001. Arbuscular mycorrhizas: producing and applying arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculum. Honolulu (HI), University of Hawaii. 47 p. doi: 10125/25589

Habte M and Manjunath A. 1987. Soil solution phosphorus status and mycorrhizal dependency in Leucaena leucocephala. Applied and environmental Microbiology 53: 797-801.

Hernández OA, Ojeda D L, López JC and Arras A M. 2010. Abonos orgánicos y su efecto en las propiedades físicas, químicas y biológicas del suelo. Tecnociencia, Chihuahua 4:1-6.

Labrador J, Guiberteau A, López L and Reyes JL. 1993. La materia orgánica en los sistemas agrícolas. Manejo y utilización. Hojas divulgadoras, (3/93). Impriine: IG. SALGEN S.A. - Rufino González, 14- 28027 Madrid, 43 p.

Manjunath A and Habte M. 1991. Root morphological characteristics of host species having distinct mycorrhizal dependency. Canadian Journal of Botany 69: 671-676. doi: 10.1139/b91-089

Medina, M. 1997. Manejo de desechos sólidos y desarrollo sustentable. CCMA, Medellin, 830-837 p.

Morales L and Varon T. 2006. Arboles ornamentales del Valle del Aburra, elementos y manejo, primera edición, Multigráficas, Medellín, 339 p.

Oliet J, Segura M and Dominguez F. 2008. Los fertilizantes de liberación controlada lenta aplicados a la producción de planta forestal de vivero. Efecto de dosis y formulaciones sobre la calidad de Pinus. Forest Systems. Retrieved from http://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/IA/article/viewArticle/2742. Consultado en Agosto de 2014

Osorio NW. 2014. Manejo de Nutrientes en el Suelo del Trópico. Segunda edición. Editorial L Vieco, Medellin, 416 p.

Pedrol N, Puig CG, Souza P, Forján R, Vega FA, Asensio V and Andrade L. 2010. Soil fertility and spontaneous revegetation in lignite spoil banks under different amendments. Soil and Tillage Research, 110(1): 134-142. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2010.07.005

Salas E and Ramírez C. 2001. Determinación del N y P en abonos orgánicos mediante la técnica del elemento faltante y un bioensayo microbiano. Agronomía Costarricense 25: 25-34.

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente de Medellín. 2015. Manual de silvicultura urbana para Medellín– Gestión, Planeación y manejo de la infraestructura verde. Fondo Editorial Jardín Botánico de Medellín. Medellín, 395 p.

Siqueira JO and Saggin-Junior OJ. 2001. Dependency on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on responsiveness of some brazilian native woody species. Mycorrhiza 11: 245-255.doi: 10.1007/s005720100129.

Siqueira JO, Carbone MA, Curi N, Da Silva CS, and Davide AC. 1998. Mycorrhizal colonization and mycotropic growth of native woody species as related to successional groups in Southeastern Brazil. Forest Ecology and Management 107: 241-252. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1127(97)00336-8

Tamayo A. 2016. Decomposition de hojarasca y liberación de nutrientes en plantaciones de aguacate cv. Hass en función de la inoculación con un hongo saprofito en tres pisos térmicos. Tesis doctoral, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Medellin. 250 p.

Ulrich R.1984. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 224: 420-423. doi: 10.1126/science.6143402

Westerman RL.1990. Soil testing and plant analysis. Soil Science Society of America, 3rd edition, Madison, WI, USA, doi:10.2136/sssabookser3.3ed.

Zangaro W, Bononi VLR and Trufen SB. 2000. Mycorrizhal dependency, inoculum potential and habitat preference of native woody species in south Brazil, Journal of Tropical Ecology 16:603-622, doi: 10.1017/S0266467400001607.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Auwalu Garba Gashua, Zulkefly Sulaiman, Martini Mohammad Yusoff, Mohd Yusoff Abd Samad, Mohd Fauzi Ramlan, Monsuru Adekunle Salisu, Mohd Shafar Jefri Mokhatar. (2022). Potting media made with bokashi compost to improve the growth and biomass accumulation of rubber seedlings. Journal of Rubber Research, 25(2), p.127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42464-022-00163-6.

2. Gustavo Wyse Abaurre, Jorge Makhlouta Alonso, Orivaldo José Saggin Júnior, Sergio Miana de Faria. (2021). Sewage Sludge Compared with Other Substrates in the Inoculation, Growth, and Tolerance to Water Stress of Samanea saman. Water, 13(9), p.1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13091306.

3. Alessander Lopes Caetano, Maxwell Pereira de Pádua, Marcelo Polo, Moacir Pasqual, Fabricio José Pereira. (2022). Growth, anatomy, and gas exchange of Cenostigma pluviosum cultivated under reduced water levels in iron mining tailings. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 22(1), p.381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-021-03060-4.

4. Leidy Yesenia Cely Vargas, Gloria Lucía Camargo Millán. (2024). Composted Sewage Sludge as Soil Amendment in Colombia: Challenges and Opportunities to Scale Up. European Journal of Theoretical and Applied Sciences, 2(4), p.987. https://doi.org/10.59324/ejtas.2024.2(4).82.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2018 Revista Facultad Nacional de Agronomía Medellín

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The journal allows the author(s) to maintain the exploitation rights (copyright) of their articles without restrictions. The author(s) accept the distribution of their articles on the web and in paper support (25 copies per issue) under open access at local, regional, and international levels. The full paper will be included and disseminated through the Portal of Journals and Institutional Repository of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, and in all the specialized databases that the journal considers pertinent for its indexation, to provide visibility and positioning to the article. All articles must comply with Colombian and international legislation, related to copyright.

Author Commitments

The author(s) undertake to assign the rights of printing and reprinting of the material published to the journal Revista Facultad Nacional de Agronomía Medellín. Any quotation of the articles published in the journal should be made given the respective credits to the journal and its content. In case content duplication of the journal or its partial or total publication in another language, there must be written permission of the Director.

Content Responsibility

The Faculty of Agricultural Sciences and the journal are not necessarily responsible or in solidarity with the concepts issued in the published articles, whose responsibility will be entirely the author or the authors.