Health, mental health, music and music therapy in a Colombian indigenous community from Cota, 2012-2014

Salud, salud mental, música y musicoterapia en una comunidad indígena colombiana. Cota, 2012-2014

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v65n3.56413Palabras clave:

Indigenous Population, Health, Mental Health, Music Therapy, Public Health, Colonialism (en)Población indígena, Salud, Salud mental, Musicoterapia, Salud Pública, Colonialismo (es)

Descargas

Introduction: The intercultural approach to indigenous peoples in the American continent requires knowledge of the concepts and cultural practices that favor or impair health, considering their own perspective.

Objective: To understand the meaning of health and mental health in the context of a Muisca community from Cota, Colombia, as well as the potential of music therapy to promote health.

Materials and methods: Case study with a qualitative approach —social research of second order. Data collection included social cartography, in-depth interviews, focus groups, participant observation, and music therapy sessions.

Results: This community has a different conception of health in relation to the beliefs of the dominant society, since health and mental health are not separate ideas. Music is integrated to community activities and health practice.

Conclusions: The re-indigenization process is a political decision with cultural, health and organizational consequences. This type of communities cannot be equated with the dominant society or other indigenous groups in terms of health decisions. Public health requires an intercultural dialogue to work adequately with these communities.

Introducción. El enfoque intercultural hacia las comunidades nativas americanas requiere el conocimiento de los conceptos y las prácticas que favorecen o perjudican la salud de estas poblaciones desde su propia perspectiva.

Objetivo. Comprender el significado de salud y salud mental que circula en las narrativas de la comunidad reetnizada indígena muisca de Cota y el potencial de la musicoterapia comunitaria para promoverlas.

Materiales y métodos. Estudio de caso con enfoque cualitativo tipo investigación social de segundo orden. Para la recolección de datos se utilizó cartografía social, entrevistas a profundidad, grupos focales, observación participante y proceso musicoterapéutico.

Resultados. La comunidad maneja un concepto de salud diferente al de la sociedad mayoritaria. No hay división entre los conceptos de salud y salud mental. La música está integrada a las actividades comunitarias y de sanación.

Conclusiones. La reetnización es una decisión política con implicaciones culturales, organizativas y de salud. Las comunidades reetnizadas no pueden ser equiparadas con la sociedad dominante ni con otros grupos indígenas en cuanto a decisiones en salud. La salud pública requiere un diálogo intercultural que permita el trabajo adecuado con estas comunidades.

Original research

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v65n3.56413

Health, mental health, music and music therapy in a Colombian

indigenous community from Cota, 2012-2014

Salud, salud mental, música y musicoterapia en una comunidad

indígena colombiana. Cota, 2012-2014

Received: 23/03/2016. Accepted: 19/05/2016.

Leonardo Alfonso Morales-Hernández1,2 • Zulma Consuelo Urrego-Mendoza1,3,4,5

1 Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Bogotá Campus - Faculty of Medicine - Medical Rationalities and Health and Illness Practices Research Group - Bogotá D.C. - Colombia.

2 Hospital Centro Oriente Empresa Social del Estado - Ricaurte Welfare Office - Bogotá D.C. - Colombia.

3 Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Bogotá Campus - Faculty of Medicine - Violence and Health Research Group - Bogotá D.C. - Colombia.

4 Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Bogotá Campus - Faculty of Medicine - Department of Psychiatry - Bogotá D.C. - Colombia.

5 Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Bogotá Campus - Faculty of Medicine - Public Health Interfaculty Doctoral Program -

Bogotá D.C. - Colombia.

Corresponding author: Leonardo Alfonso Morales. Public Health Interfaculty Doctoral Program, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Carrera 9 No. 48-51, office 406. Phone number: +57 1 3165000, ext.: 10908. Bogotá D.C. Colombia. Email: leoaph2007@gmail.com.

| Abstract |

Introduction: The intercultural approach to indigenous peoples in the American continent requires knowledge of the concepts and cultural practices that favor or impair health, considering their own perspective.

Objective: To understand the meaning of health and mental health in the context of a Muisca community from Cota, Colombia, as well as the potential of music therapy to promote health.

Materials and methods: Case study with a qualitative approach —social research of second order. Data collection included social cartography, in-depth interviews, focus groups, participant observation, and music therapy sessions.

Results: This community has a different conception of health in relation to the beliefs of the dominant society, since health and mental health are not separate ideas. Music is integrated to community activities and health practice.

Conclusions: The re-indigenization process is a political decision with cultural, health and organizational consequences. This type of communities cannot be equated with the dominant society or other indigenous groups in terms of health decisions. Public health requires an intercultural dialogue to work adequately with these communities.

Keywords: Indigenous Population; Health; Mental Health; Music Therapy; Public Health; Colonialism (MeSH).

Morales-Hernández LA, Urrego-Mendoza ZC. Health, mental health, music and music therapy in a Colombian indigenous community from Cota, 2012-2014. Rev. Fac. Med. 2017;65(3):461-5. English. doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v65n3.56413.

| Resumen |

Introducción. El enfoque intercultural hacia las comunidades nativas americanas requiere el conocimiento de los conceptos y las prácticas que favorecen o perjudican la salud de estas poblaciones desde su propia perspectiva.

Objetivo. Comprender el significado de salud y salud mental que circula en las narrativas de la comunidad reetnizada indígena muisca de Cota y el potencial de la musicoterapia comunitaria para promoverlas.

Materiales y métodos. Estudio de caso con enfoque cualitativo tipo investigación social de segundo orden. Para la recolección de datos se utilizó cartografía social, entrevistas a profundidad, grupos focales, observación participante y proceso musicoterapéutico.

Resultados. La comunidad maneja un concepto de salud diferente al de la sociedad mayoritaria. No hay división entre los conceptos de salud y salud mental. La música está integrada a las actividades comunitarias y de sanación.

Conclusiones. La reetnización es una decisión política con implicaciones culturales, organizativas y de salud. Las comunidades reetnizadas no pueden ser equiparadas con la sociedad dominante ni con otros grupos indígenas en cuanto a decisiones en salud. La salud pública requiere un diálogo intercultural que permita el trabajo adecuado con estas comunidades.

Palabras clave: Población indígena; Salud; Salud mental; Musicoterapia; Salud Pública; Colonialismo (DeCS).

Morales-Hernández LA, Urrego-Mendoza ZC. [Salud, salud mental, música y musicoterapia en una comunidad indígena colombiana. Cota, 2012-2014]. Rev. Fac. Med. 2017;65(3):461-5. Ennglish. doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v65n3.56413.

Introduction

The cultural capital of a community (ancestral knowledge, music, community practices, stories and accounts) is part of its legacy, defines its identity and supports its functioning. The concepts of a community, the related aspects, and the cultural practices that have an influence on health define the approach, in general and from a public health perspective.

The Muisca community that participated in this study lives in Cota, Cundinamarca, near Bogotá. It is an indigenous community, currently undergoing a re-indigenization process, for which the reconstruction of its cultural elements has been fundamental. Music, in a broad sense (body-sound-musical narrative), was used as the main means of contact with this community and as a therapeutic tool (music therapy) (1,2).

Culture and health

The colonialism imposed by Europe 500 years ago, and perpetuated by hegemonic science, is an epistemic obstacle to learn about the concepts of the indigenous communities and to define approaches suitable for each context. An intercultural understanding is necessary (3) to make proposals closer to local cultures, especially indigenous cultures. Interculturality facilitates describing and understanding ontologies, epistemologies and practices from different perspectives of reality, and appreciating their uniqueness.

The dominant concepts of health and mental health are based on models alien to indigenous cultures, which must be re-dimensioned to understand their knowledge, customs and strategies, and to avoid authoritarian and colonialist perspectives. Only in this way, a closer approach to the contexts and interests of these communities can be achieved.

Health, mental health and interculturality

The concept of health for indigenous peoples is different from the hegemonic concept of European medicine, even in its paradigmatic foundations. Usually, some native peoples have an idea of unity between body, mind, actions, community, health (4,5) and the onset of a disease. Others conceive disease as the product of an alteration of the mind, which occurs when such unity, or balance, is lost (6). This is not an individual phenomenon, but the manifestation of a disorder within the community itself.

In this context, the concept of mental health is meaningless for the indigenous peoples, because there is no fragmentation of the individual-community unit. The recipients of healing include the individual, the territory and the community, who are healed by sacred plants (7), music (in a ritualistic performance), words, pagamentos1, among others, in a period and territory established by the law of each community.

Intercultural understanding requires a dialogue between different strands of knowledge, that is, a participatory process between the authors and the addressed peoples. Interculturality can be observed at interpersonal, group and structural levels, and it will be achieved when we become equal while being different (8). Furthermore, interculturality represents the relationship and the attitude of the members of one culture towards the elements of another. In the case of the indigenous peoples, interculturality regarding health implies equally incorporating their perspective on rights, understandings and epistemologies (9).

Decolonization, hybridization and re-indigenization processes

European colonization brought along a model for the valuation of people, knowledge and cultures that became hegemonic. According to this model, white men are the center of history, and their patterns and values are ethnically focused on Europe; likewise, in their epistemological model, the observer transcends the object (10). This object, in turn, is fragmented in different pieces —reality is reduced to a mechanical level—, which are analyzed (11) based on a numerical rationality (12). Results, knowledge and production are more valued, if they stick to this model.

Since the end of the XX century, a hybridization process begun to take place. Hybridization is an epistemological operation in which different structures, objects and practices (with different origins) are combined to generate new structures, new objects and new practices (13). In this way, culture and identity are no longer a set of fixed traits in a fluid and interconnected world, and different definitions emerge in each of their expressions. The understanding of indigenous and Latin American cultures requires open and plural readings to construct coexistence projects.

The need to decolonize the Latin American society in all its structures, forms and purposes is perceived in the academy and in other cultures. It is sought that the “subalterns” tell their own story, to decolonize beings and knowledge, in the framework of a transformational project through critical praxis. Thus, a Latin American model based on ancestral knowledge is proposed, in which the epistemological dialogue allows positioning a different idea of interculturality and the emergence of frontier thinking (14).

The re-indigenization processes help turning cultural diversity into heritage to consolidate a pluralist image of the nation. In accordance with the political environment, rights are claimed. In the case of the indigenous community of Cota, a generic identity (being indigenous) and a particular way of identifying themselves (member of the Muisca community) have been sought (15).

Faced with such situations, communities take cultural elements with which they identify, and build a pattern that is later staged (performative development). Thus, they validate cultural singularities —for example, cultural reconstruction— and neutralize racial traces, thereby strengthening language, clothing, customs and continuity in time and space.

In indigenous cultures, performance is clearer in music or healing rituals, since they follow steps and methods that are visible to the spectator, who also takes part. During community practices, the youngest perform rituals accompanied by music and clothing, create spaces for social communication and inclusion, and become camouflaged. In consequence, the community rebuilds its political spaces in a counter-hegemonic way, establishing itself as the center and source of its own transformation. Mimesis involves taking the cultural traces, making them visible, and experiencing them, so that they can be used to establish and lead the way (16). With this in mind, all the elements of the Muisca re-indigenization (revitalization) are valid.

The indigenous Muisca community of Cota has undergone a re-indigenization process and has reconstructed its memory based on the muysqubum language, their ancestral community practices, and the knowledge of other Colombian and American indigenous peoples. All these peoples have created a relationship network and have incorporated musical, bromatological, medicinal and organizational elements, among others.

Indigenous cultural practices and music

According to the principles of each indigenous community, cultural practices obey the legacy of their ancestors, that is to say, their origins. These practices, in a ritual context, give meaning and sense to the existence of the community and to each of its members. Rituals keep the contact with the origin law alive, articulate the culture of the community with the cosmos, and give coherence to daily life. Cultural practices (music, dance) are mechanisms for communication between the communities and, in a broader sense, are ways to commemorate, contact and provide unity with the cosmos, based on the concept that each indigenous group has. The spoken word should be full of meaning and sense. In community life, words are used in different practices, and are given different categories: word of life, word of advice, word of work, word of abundance and word of community or government. Each one has an organizational power.

The expression of the shamanic song (amensural chants) is full of meaning, because the shaman is the holder of the worldview and the mythology of the group, which are transmitted through his songs. The songs are learned from communications with the beyond using entheogenic weeds, and are transmitted from generation to generation, often in a secret language. Chants and music have the power to invoke powerful spirits (17).

Music and music therapy in public health

The knowledge of cultural referents is a particular universe of languages with its own meaning —in the same fabric or narrative— that unifies words, stories, movement, mimics and music, among other elements.

Music is a cultural expression that is part of the knowledge of a community and, therefore, is transmitted in their educational systems. Music creates imaginary spaces, offers social cohesion, opens up possibilities for subjectivation and is involved in communicative strategies —at the market level. It also fulfills other social functions such as aesthetic enjoyment, entertainment, communication, symbolic representation, physical response and reinforcement, in accordance with norms, social institutions and religious rites. It also contributes to the continuity and establishment of culture and the integration of society (18). A narrative space of great symbolic content is created through music, which offers identity from and for the group that constructs and uses it.

An important concept to understand the role of music in health is “musicing”, which refers to any activity related to the musical act. In general, it refers to the relation of humans with music during a performance, and to the power that this mutual relation has on the experiences, feelings, thoughts, images and interactions, in other words, the influence music has on the lives of the people around it (19).

The spectrum of “musicing” involves the entire network of relationships involved in a performance. Stige (20) states that “musicing” refers to both music and a particular activity that involves multiple people and social relationships when it is staged. The meaning of “musicing” (an action that has an effect) is difficult to express in simple words. It is easier to experience it in a sensory way; it resembles the grooving (atmosphere) that a musical rhythm generates or the description of a flavor for who has not tried it yet. This is a key concept in the development of music therapy as a performance, to understand how the music therapist and the consultant correlate —whether it is a person, a family or a community—, and how they experience its effect in practice.

In music therapy, a qualified therapist uses music or its elements (sound, rhythm, melody and harmony) on a person or group to facilitate and promote communication, relationships, learning, mobilization, expression and organization, in order to solve physical, emotional, mental, social and cognitive needs.

The objective of music therapy is to develop potential skills or to restore the individual’s functions through prevention, rehabilitation or treatment, with the intention of achieving a better intra or interpersonal integration (21). Its focus is to strengthen social representations (22), consolidate cultural capital (23), and promote social welfare in, through and with the community.

Regarding music therapy and its effect on mental health in indigenous communities, specific works that directly answered the question raised in this research were not found. In consequence, this work intends to understand the meaning of health and mental health in the narratives of the inhabitants of the Muisca community from Cota, and the potential of community music therapy to promote them.

Materials and methods

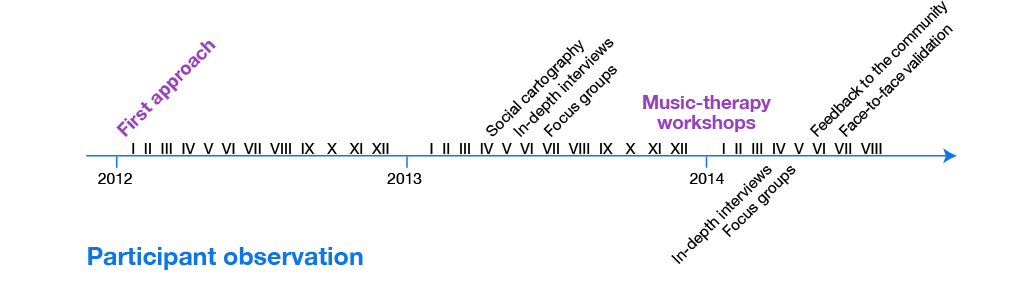

A case study (community being the case) was conducted with a qualitative approach based on a second order social research for a period of 32 months (Figure 1). In addition to music therapy, social cartography, in-depth interviews, focus groups and participant observation were used as data collection techniques. A snowball sampling (25) was used to select the subjects. The systemic constructivist-constructionist approach was used as a theoretical and epistemological resource.

Figure 1. Study timeline.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

A narrative and a paradigmatic analysis were performed on the narratives obtained from participant observation, interviews and focus groups (26). The programs NVivo (QSR International, Australia) and CmapTools (Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition, USA) were used to assist the organization and analysis of information.

Results

Description of the Community

Culture and traditional medicine are of great importance to the community. Medical practice is built together with other town councils and indigenous reservations, and involves health, music, culture, territory and networks. Consciousness of territory as a spiritual and wisdom source was a constant variable for the analysis, since, for the inhabitants, “the body is our territory” and there is continuity between the mother earth and the individual body. Some problems regarding internal communication within the community (inadequate, confusing or incoherent messages) were found. Likewise, discrimination, especially sexism, was observed, as well as conflicts of power among leaders, and resolution mechanisms for such problems in community spaces.

Health and mental health

There is not a clear differentiation between health and mental health. Health is understood as “integrity”, “community” and “it emerges from us.” It is related to balance and here, just like in other vitalist medicine models, symptoms are manifestations of real diseases such as predominance of individualism, loss of connection with the mother earth and the spiritual father, lack of awareness of the law of origin, corruption and lack of integrity, coherence and communication. This contrasts with the conception that the traditional medicine has on the same topic, that is, that symptoms are the disease.

Mother earth and music are equally considered as intrinsic elements of health. Music is expressed as a factor that promotes health and a component of healing activities. The narrative analysis mentions the vibrational and energetic links that it generates.

Some constitutive elements of healing are plants and music (or chants). The relationship between healing and the awareness of the “gardener” role —being responsible for the mother earth and members of a community— is evident. Healing also relates to the coherence between heart, thought, word and action.

Health and mental health appear as a continuum in both analysis; the understanding of this concept includes the individual, and transforms into completeness connecting the collective, the spiritual and the relationship with other living beings.

Cultural components associated with music

In general, music (dance, sound, singing, cooing, etc.) makes up more than half of the cultural activities and expressions of the community. The construction of musical instruments occurs in a smaller proportion.

Dances have a repetitive circular and spiral movement, which closes and opens the spaces and has a direct relation with territory awareness. The Andean music, used with symbolic meaning, is linked to the experience of traditional medicine, and its meaning seeks to be cosmic.

Music is connected with community healing practices, territory-body relationship, recovery of ancestral memory, balance and energy, and holistically approaches the concept of health. Music has different uses: recreational and educational, integration of the community, and ceremonial and ancestral aspects associated with spirituality and health.

Connections between music and health

There is evidence of a direct connection between dance and health, which integrates vibration and culture. Dance has a special effect on the sense of community (the conjugation of the subject we), as it links its members to each other and to mother earth.

Conscience music integrates the system and provides health to people and the community; it is a community practice related to ancestral heritage, territory, medicine and healing. This healing occurs between the members of the community (people) and nature. More than being a ludic musical activity, it establishes contact with consciousness at the different levels of the system: vibrations, memory, molecules, medicine, people, community and culture.

Music and dance connect with health and have the ability to transform the state of things, people and relationships. For this community, music and health have several connections, some at the molecular level, and others in the internal structures of a person or the community.

Thus, music can be a healing or distorting element, depending on how it is used. It can be used, for example, to share and socialize, to accompany the rite, to heal directly as a part of the dance, with a meaning different to the healing ritual that emphasizes on the cosmic, communitarian and territorial dimensions. In other words, “you are what you listen to”, how aware you are, how you perform, and your intention during the act as a whole.

Contribution of music therapy to health processes

Music therapy, as a tool, has the power to give order to the body, the territory and the environment. It contributes to the expansion of awareness of the harmony between the body and the environment, as well as of internal-external communication, the ancestral memory, the harmonization of community relations, and the connection with cosmic principles (law of origin) ruling this community.

Discussion

Decolonized and re-indigenized knowledge is different from traditional knowledge in Western cultures (15). For example, while white peoples see only a plant, indigenous peoples perceive the cosmos, the people and the powers. In this scenario, there is a difference between the myth of nature and the reality of the myth. In order to approach the meaning of this knowledge, it is necessary to “demythologize history and re-enchant it in a reified representation (7, p39).”

Today, re-indigenization (revitalization of the indigenous) identifies the Muisca community of Cota as a private, independent community with its own (rebuilt) cultural elements, knowledge and alliances with other ethnic groups that recognize them as indigenous in their cultural, organizational and political structure. This community reached a symbolic status with a transforming effect of the reality that characterized its Muisca identity.

It is worth mentioning that the community prefers the expression “resignification of the indigenous” over the term “ re-indigenization.” Its members shared the conclusions, participated in the discussion and were motivated to continue with music and music therapy activities for community strengthening. The relationships that this community establishes with music generate bonds between its members and with the self in its entirety, from a molecule to Mother Nature, passing through the community in its cosmic sense.

Future research on mental health and public health with indigenous peoples should be directed towards a truly transformative intercultural dialogue between public health and the communities, in order to contribute in a relevant way to the good life of the ethnic group, respecting their ancestry and their methodologies to build knowledge.

Conclusions

The concept of health found in the community narrative encompasses individuals, mind, body, territory, and mother earth. In this concept, both the spiritual and the ecological elements are involved. There is no difference between health and mental health, because the latter only emphasizes the first. Disease is related to the supremacy of individual interests over community interests.

For the re-indigenized Muiscas from Cota, health and healing are holistic phenomena that surpass an individualist approach, and are connected to the universe —it is better to say multiverse— of relationships (27,28), in which performance includes consciousness, plants, sound, music, thought, spirit, territory and their connections in a syncretic web woven with ancestral and contemporary elements.

Music is a cultural element evident in most of the community’s activities; it is a tool that helps strengthen and heal the community. In such context, music therapy is a transformative act when conditions are given to experience the performance. The “musicing” act allowed the emergence of special states of consciousness and the contact with the ancestral memory. In addition, it allowed the Muiscas to verify the manifestation of knowledge related to health and mental health. This knowledge could be incorporated into their new law of origin (neomuisca), which is memory and code for these people.

Conflict of interests

None stated by the authors.

Funding

None stated by the authors.

Acknowledgment

None stated by the authors.

1 Translator’s note: Pagamento refers to actions done based on a principle of reciprocity, giving always something in return, whether it is material or in species.

References

1.Benenzon R. Aplicaciones clínicas de la musicoterapia. Buenos Aires: Lumen; 2000.

2.Benenzon R. La nueva musicoterapia. Buenos Aires: Lumen; 1998.

3.Colombia. Congreso de la República. Ley Estatutaria 1751 de 2015 (febrero 16): Por medio de la cual se regula el derecho fundamental a la salud y se dictan otras disposiciones. Bogotá D.C.: Diario Oficial 49427; febrero 16 de 2015 [cited 2016 Apr 13] Available from: https://goo.gl/1iVdjT.

4.Lacaze D. Proyecto de construcción de la circunscripción territorial de la nacionalidad kichwa de Pastaza. In: Cruz MP, Vargas-Clavijo M, Talero GM, Sarmiento I, editors. IV Congreso Colombiano de Etnobiología: Diversidad de Saberes y Memoria Biocultural en Colombia. Bogotá D.C.: Sociedad Colombiana de Etnobiología; 2013.

5.Quevedo E, editor. Historia de la medicina en Colombia. Tomo I: Prácticas médicas en conflicto (1492-1782). Bogotá D.C.: Norma; 2007.

6.Pedraza H. Ambiente, cultura y espíritu, una mirada intencional a lo invisible. Bogotá D.C.: CAR; 2004.

7.Taussig M. Chamanismo, colonialismo y el hombre salvaje. Un estudio sobre el terror y la curación. 2nd ed. Popayán: Universidad del Cauca; 2012.

8.Albó X. Interculturalidad y salud. In: Fernández G, coordinator. Salud e interculturalidad en América Latina. Perspectivas antropológicas. Quito: Ediciones Abya Yala; 2004. p. 65-72.

9.Hernández C. Estado del arte en investigación sobre la salud mental y enfermedades transmisibles en los pueblos indígenas de América. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia; 2005.

10.Amaral de Sousa E, Luz M. Bases socioculturais das práticas terapêuticas alternativas. Hist. cienc. saude-Manguinhos. 2009;16(2):393-405.

11.Andrade LE. Los demonios de Darwin. Semiótica y termodinámica de la evolución biológica. Bogotá D.C.: Universidad Nacional de Colombia; 2003.

12.Méndez-Reyes J. Universidad, decolonización e interculturalidad otra. Más allá de la “hybris de punto cero”. Revista de Filosofía. 2013;75(3):66-86.

13.García-Canclini N. Interculturalidad e hibridación latino. México D.F.: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana de Iztapalapa; 1999 [cited 2016 Apr 13] Available from: https://goo.gl/1TWViT.

14.Walsh C. ¿Qué conocimiento(s)? Reflexiones sobre políticas de conocimientos, el campo académico y el movimiento indígena ecuatoriano. Boletín ICCI. 2001 [cited 2016 Apr 12];3(25). Available from: https://goo.gl/wEo4Tf.

15.Morales L. Reflexiones sobre multiculturalidad, grupos étnicos, prácticas terapéuticas y movimientos de reindigenización en Colombia. Revista de Investigaciones en Seguridad Social y Salud. 2015;17(1):77-92.

16.Martínez S. Poderes de la mimesis: Identidad y curación en la comunidad indígena muisca de Bosa. Bogotá D.C.: Ediciones Uniandes; 2009.

17.Aretz I. Síntesis de la etnomúsica en América Latina. Caracas: Monte Ávila Editores; 1981.

18.Zapata G, Goubert B, Maldonado J. Universidad, músicas urbanas, pedagogía y cotidianidad. Bogotá D.C.: Universidad Pedagógica Nacional; 2005.

19.Small C. Musicing: The meanings of performing and listening (music/culture). Middletown: Wesleyan University Press; 1998.

20.Stige B. Ethnography and ethnographically informed research. In: Wheeler B, editor. Music therapy research. New Braunfels: Barcelona Publishers; 2005. p. 392-403.

21.Wigram T, Nygaard I, Ole-Blonde L. A comprehensive guide to music therapy. Theory, clinical practice, research and training. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2002.

22.Pellizzari P, Rodríguez R. Salud, escucha y creatividad. Musicoterapia preventiva psicosocial. Buenos Aires: Universidad del Salvador; 2005.

23.Procter S. Playing politics: community music therapy and the therapeutic redistribution of musical capital for mental health. In: Pavlicevic M, Ansdell G, editors. Community music therapy. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2004. p. 214-230.

24.Stige B. Community music therapy: culture, care and welfare. In: Pavlicevic M, Ansdell G, editors. Community music therapy. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2004. p. 91-113.

25.Salamanca A, Martín-Crespo M. El muestreo en la investigación cualitativa. Nure Investigación. 2007 [cited 2016 Apr 13];27(7). Available from: https://goo.gl/uWNW36.

26.Bolívar A. “¿De nobis ipsis silemus?”: Epistemología de la investigación biográfico-narrativa en educación. REDIE. 2002 [cited 2016 Apr 12];4(1). Available from: https://goo.gl/EhGxgX.

27.Mazorco G. La descolonización en tiempos del Pachakutik. Polis. 2010;9(27):219-242.

28.Maturana H. La objetividad. Un argumento para obligar. Santiago de Chile: Dolmen; 1997.

Iván “Ivanquio” Benavides

“El niño vacío” – 006

Técnica: tinta, color digital

Recibido: 23 de marzo de 2016; Aceptado: 19 de mayo de 2016

Abstract

Introduction:

The intercultural approach to indigenous peoples in the American continent requires knowledge of the concepts and cultural practices that favor or impair health, considering their own perspective.

Objective:

To understand the meaning of health and mental health in the context of a Muisca community from Cota, Colombia, as well as the potential of music therapy to promote health.

Materials and methods:

Case study with a qualitative approach -social research of second order. Data collection included social cartography, in-depth interviews, focus groups, participant observation, and music therapy sessions.

Results:

This community has a different conception of health in relation to the beliefs of the dominant society, since health and mental health are not separate ideas. Music is integrated to community activities and health practice.

Conclusions:

The re-indigenization process is a political decision with cultural, health and organizational consequences. This type of communities cannot be equated with the dominant society or other indigenous groups in terms of health decisions. Public health requires an intercultural dialogue to work adequately with these communities.

Keywords:

Indigenous Population, Health, Mental Health, Music Therapy, Public Health, Colonialism (MeSH).Resumen

Introducción.

El enfoque intercultural hacia las comunidades nativas americanas requiere el conocimiento de los conceptos y las prácticas que favorecen o perjudican la salud de estas poblaciones desde su propia perspectiva.

Objetivo.

Comprender el significado de salud y salud mental que circula en las narrativas de la comunidad reetnizada indígena muisca de Cota y el potencial de la musicoterapia comunitaria para promoverlas.

Materiales y métodos.

Estudio de caso con enfoque cualitativo tipo investigación social de segundo orden. Para la recolección de datos se utilizó cartografía social, entrevistas a profundidad, grupos focales, observación participante y proceso musicoterapéutico.

Resultados.

La comunidad maneja un concepto de salud diferente al de la sociedad mayoritaria. No hay división entre los conceptos de salud y salud mental. La música está integrada a las actividades comunitarias y de sanación.

Conclusiones.

La reetnización es una decisión política con implicaciones culturales, organizativas y de salud. Las comunidades reetnizadas no pueden ser equiparadas con la sociedad dominante ni con otros grupos indígenas en cuanto a decisiones en salud. La salud pública requiere un diálogo intercultural que permita el trabajo adecuado con estas comunidades.

Palabras clave:

Población indígena, Salud, Salud mental, Musicoterapia, Salud Pública, Colonialismo (DeCS).Introduction

The cultural capital of a community (ancestral knowledge, music, community practices, stories and accounts) is part of its legacy, defines its identity and supports its functioning. The concepts of a community, the related aspects, and the cultural practices that have an influence on health define the approach, in general and from a public health perspective.

The Muisca community that participated in this study lives in Cota, Cundinamarca, near Bogotá. It is an indigenous community, currently undergoing a re-indigenization process, for which the reconstruction of its cultural elements has been fundamental. Music, in a broad sense (body-sound-musical narrative), was used as the main means of contact with this community and as a therapeutic tool (music therapy) 1,2.

Culture and health

The colonialism imposed by Europe 500 years ago, and perpetuated by hegemonic science, is an epistemic obstacle to learn about the concepts of the indigenous communities and to define approaches suitable for each context. An intercultural understanding is necessary 3 to make proposals closer to local cultures, especially indigenous cultures. Interculturality facilitates describing and understanding ontologies, epistemologies and practices from different perspectives of reality, and appreciating their uniqueness.

The dominant concepts of health and mental health are based on models alien to indigenous cultures, which must be re-dimensioned to understand their knowledge, customs and strategies, and to avoid authoritarian and colonialist perspectives. Only in this way, a closer approach to the contexts and interests of these communities can be achieved.

Health, mental health and interculturality

The concept of health for indigenous peoples is different from the hegemonic concept of European medicine, even in its paradigmatic foundations. Usually, some native peoples have an idea of unity between body, mind, actions, community, health 4,5 and the onset of a disease. Others conceive disease as the product of an alteration of the mind, which occurs when such unity, or balance, is lost 6. This is not an individual phenomenon, but the manifestation of a disorder within the community itself.

In this context, the concept of mental health is meaningless for the indigenous peoples, because there is no fragmentation of the individual-community unit. The recipients of healing include the individual, the territory and the community, who are healed by sacred plants 7, music (in a ritualistic performance), words, pagamentos , among others, in a period and territory established by the law of each community.

Intercultural understanding requires a dialogue between different strands of knowledge, that is, a participatory process between the authors and the addressed peoples. Interculturality can be observed at interpersonal, group and structural levels, and it will be achieved when we become equal while being different 8. Furthermore, interculturality represents the relationship and the attitude of the members of one culture towards the elements of another. In the case of the indigenous peoples, interculturality regarding health implies equally incorporating their perspective on rights, understandings and epistemologies 9.

Decolonization, hybridization and re-indigenization processes

European colonization brought along a model for the valuation of people, knowledge and cultures that became hegemonic. According to this model, white men are the center of history, and their patterns and values are ethnically focused on Europe; likewise, in their epistemological model, the observer transcends the object 10. This object, in turn, is fragmented in different pieces -reality is reduced to a mechanical level-, which are analyzed 11 based on a numerical rationality 12. Results, knowledge and production are more valued, if they stick to this model.

Since the end of the XX century, a hybridization process begun to take place. Hybridization is an epistemological operation in which different structures, objects and practices (with different origins) are combined to generate new structures, new objects and new practices 13. In this way, culture and identity are no longer a set of fixed traits in a fluid and interconnected world, and different definitions emerge in each of their expressions. The understanding of indigenous and Latin American cultures requires open and plural readings to construct coexistence projects.

The need to decolonize the Latin American society in all its structures, forms and purposes is perceived in the academy and in other cultures. It is sought that the "subalterns" tell their own story, to decolonize beings and knowledge, in the framework of a transformational project through critical praxis. Thus, a Latin American model based on ancestral knowledge is proposed, in which the epistemological dialogue allows positioning a different idea of interculturality and the emergence of frontier thinking 14.

The re-indigenization processes help turning cultural diversity into heritage to consolidate a pluralist image of the nation. In accordance with the political environment, rights are claimed. In the case of the indigenous community of Cota, a generic identity (being indigenous) and a particular way of identifying themselves (member of the Muisca community) have been sought 15.

Faced with such situations, communities take cultural elements with which they identify, and build a pattern that is later staged (performative development). Thus, they validate cultural singularities -for example, cultural reconstruction- and neutralize racial traces, thereby strengthening language, clothing, customs and continuity in time and space.

In indigenous cultures, performance is clearer in music or healing rituals, since they follow steps and methods that are visible to the spectator, who also takes part. During community practices, the youngest perform rituals accompanied by music and clothing, create spaces for social communication and inclusion, and become camouflaged. In consequence, the community rebuilds its political spaces in a counter-hegemonic way, establishing itself as the center and source of its own transformation. Mimesis involves taking the cultural traces, making them visible, and experiencing them, so that they can be used to establish and lead the way 16. With this in mind, all the elements of the Muisca re-indigenization (revitalization) are valid.

The indigenous Muisca community of Cota has undergone a re-indigenization process and has reconstructed its memory based on the muysqubum language, their ancestral community practices, and the knowledge of other Colombian and American indigenous peoples. All these peoples have created a relationship network and have incorporated musical, bromatological, medicinal and organizational elements, among others.

Indigenous cultural practices and music

According to the principles of each indigenous community, cultural practices obey the legacy of their ancestors, that is to say, their origins. These practices, in a ritual context, give meaning and sense to the existence of the community and to each of its members. Rituals keep the contact with the origin law alive, articulate the culture of the community with the cosmos, and give coherence to daily life. Cultural practices (music, dance) are mechanisms for communication between the communities and, in a broader sense, are ways to commemorate, contact and provide unity with the cosmos, based on the concept that each indigenous group has. The spoken word should be full of meaning and sense. In community life, words are used in different practices, and are given different categories: word of life, word of advice, word of work, word of abundance and word of community or government. Each one has an organizational power.

The expression of the shamanic song (amensural chants) is full of meaning, because the shaman is the holder of the worldview and the mythology of the group, which are transmitted through his songs. The songs are learned from communications with the beyond using entheogenic weeds, and are transmitted from generation to generation, often in a secret language. Chants and music have the power to invoke powerful spirits 17.

Music and music therapy in public health

The knowledge of cultural referents is a particular universe of languages with its own meaning -in the same fabric or narrative- that unifies words, stories, movement, mimics and music, among other elements.

Music is a cultural expression that is part of the knowledge of a community and, therefore, is transmitted in their educational systems. Music creates imaginary spaces, offers social cohesion, opens up possibilities for subjectivation and is involved in communicative strategies -at the market level. It also fulfills other social functions such as aesthetic enjoyment, entertainment, communication, symbolic representation, physical response and reinforcement, in accordance with norms, social institutions and religious rites. It also contributes to the continuity and establishment ofculture and the integration ofsociety 18. A narrative space of great symbolic content is created through music, which offers identity from and for the group that constructs and uses it.

An important concept to understand the role of music in health is "musicing", which refers to any activity related to the musical act. In general, it refers to the relation of humans with music during a performance, and to the power that this mutual relation has on the experiences, feelings, thoughts, images and interactions, in other words, the influence music has on the lives of the people around it 19.

The spectrum of "musicing" involves the entire network of relationships involved in a performance. Stige 20 states that "musicing" refers to both music and a particular activity that involves multiple people and social relationships when it is staged. The meaning of "musicing" (an action that has an effect) is difficult to express in simple words. It is easier to experience it in a sensory way; it resembles the grooving (atmosphere) that a musical rhythm generates or the description of a flavor for who has not tried it yet. This is a key concept in the development of music therapy as a performance, to understand how the music therapist and the consultant correlate -whether it is a person, a family or a community-, and how they experience its effect in practice.

In music therapy, a qualified therapist uses music or its elements (sound, rhythm, melody and harmony) on a person or group to facilitate and promote communication, relationships, learning, mobilization, expression and organization, in order to solve physical, emotional, mental, social and cognitive needs.

The objective of music therapy is to develop potential skills or to restore the individual's functions through prevention, rehabilitation or treatment, with the intention of achieving a better intra or interpersonal integration 21. Its focus is to strengthen social representations 22, consolidate cultural capital 23, and promote social welfare in, through and with the community.

Regarding music therapy and its effect on mental health in indigenous communities, specific works that directly answered the question raised in this research were not found. In consequence, this work intends to understand the meaning of health and mental health in the narratives of the inhabitants of the Muisca community from Cota, and the potential of community music therapy to promote them.

Materials and methods

A case study (community being the case) was conducted with a qualitative approach based on a second order social research for a period of 32 months (Figure 1). In addition to music therapy, social cartography, in-depth interviews, focus groups and participant observation were used as data collection techniques. A snowball sampling 25 was used to select the subjects. The systemic constructivist-constructionist approach was used as a theoretical and epistemological resource.

Figure 1: Study timeline.

A narrative and a paradigmatic analysis were performed on the narratives obtained from participant observation, interviews and focus groups 26. The programs NVivo (QSR International, Australia) and CmapTools (Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition, USA) were used to assist the organization and analysis of information.

Results

Description of the Community

Culture and traditional medicine are of great importance to the community. Medical practice is built together with other town councils and indigenous reservations, and involves health, music, culture, territory and networks. Consciousness of territory as a spiritual and wisdom source was a constant variable for the analysis, since, for the inhabitants, "the body is our territory" and there is continuity between the mother earth and the individual body. Some problems regarding internal communication within the community (inadequate, confusing or incoherent messages) were found. Likewise, discrimination, especially sexism, was observed, as well as conflicts of power among leaders, and resolution mechanisms for such problems in community spaces.

Health and mental health

There is not a clear differentiation between health and mental health. Health is understood as "integrity", "community" and "it emerges from us." It is related to balance and here, just like in other vitalist medicine models, symptoms are manifestations of real diseases such as predominance of individualism, loss of connection with the mother earth and the spiritual father, lack of awareness of the law of origin, corruption and lack of integrity, coherence and communication. This contrasts with the conception that the traditional medicine has on the same topic, that is, that symptoms are the disease.

Mother earth and music are equally considered as intrinsic elements of health. Music is expressed as a factor that promotes health and a component of healing activities. The narrative analysis mentions the vibrational and energetic links that it generates.

Some constitutive elements of healing are plants and music (or chants). The relationship between healing and the awareness of the "gardener" role -being responsible for the mother earth and members of a community- is evident. Healing also relates to the coherence between heart, thought, word and action.

Health and mental health appear as a continuum in both analysis; the understanding of this concept includes the individual, and transforms into completeness connecting the collective, the spiritual and the relationship with other living beings.

Cultural components associated with music

In general, music (dance, sound, singing, cooing, etc.) makes up more than half of the cultural activities and expressions of the community. The construction of musical instruments occurs in a smaller proportion.

Dances have a repetitive circular and spiral movement, which closes and opens the spaces and has a direct relation with territory awareness. The Andean music, used with symbolic meaning, is linked to the experience of traditional medicine, and its meaning seeks to be cosmic.

Music is connected with community healing practices, territory-body relationship, recovery of ancestral memory, balance and energy, and holistically approaches the concept of health. Music has different uses: recreational and educational, integration of the community, and ceremonial and ancestral aspects associated with spirituality and health.

Connections between music and health

There is evidence of a direct connection between dance and health, which integrates vibration and culture. Dance has a special effect on the sense of community (the conjugation of the subject we), as it links its members to each other and to mother earth.

Conscience music integrates the system and provides health to people and the community; it is a community practice related to ancestral heritage, territory, medicine and healing. This healing occurs between the members of the community (people) and nature. More than being a ludic musical activity, it establishes contact with consciousness at the different levels of the system: vibrations, memory, molecules, medicine, people, community and culture.

Music and dance connect with health and have the ability to transform the state of things, people and relationships. For this community, music and health have several connections, some at the molecular level, and others in the internal structures of a person or the community.

Thus, music can be a healing or distorting element, depending on how it is used. It can be used, for example, to share and socialize, to accompany the rite, to heal directly as a part of the dance, with a meaning different to the healing ritual that emphasizes on the cosmic, communitarian and territorial dimensions. In other words, "you are what you listen to", how aware you are, how you perform, and your intention during the act as a whole.

Contribution of music therapy to health processes

Music therapy, as a tool, has the power to give order to the body, the territory and the environment. It contributes to the expansion of awareness of the harmony between the body and the environment, as well as of internal-external communication, the ancestral memory, the harmonization of community relations, and the connection with cosmic principles (law of origin) ruling this community.

Discussion

Decolonized and re-indigenized knowledge is different from traditional knowledge in Western cultures 15. For example, while white peoples see only a plant, indigenous peoples perceive the cosmos, the people and the powers. In this scenario, there is a difference between the myth of nature and the reality of the myth. In order to approach the meaning of this knowledge, it is necessary to "demythologize history and re-enchant it in a reified representation (7, p39)."

Today, re-indigenization (revitalization of the indigenous) identifies the Muisca community of Cota as a private, independent community with its own (rebuilt) cultural elements, knowledge and alliances with other ethnic groups that recognize them as indigenous in their cultural, organizational and political structure. This community reached a symbolic status with a transforming effect of the reality that characterized its Muisca identity.

It is worth mentioning that the community prefers the expression "resignification of the indigenous" over the term " re-indigenization." Its members shared the conclusions, participated in the discussion and were motivated to continue with music and music therapy activities for community strengthening. The relationships that this community establishes with music generate bonds between its members and with the self in its entirety, from a molecule to Mother Nature, passing through the community in its cosmic sense.

Future research on mental health and public health with indigenous peoples should be directed towards a truly transformative intercultural dialogue between public health and the communities, in order to contribute in a relevant way to the good life of the ethnic group, respecting their ancestry and their methodologies to build knowledge.

Conclusions

The concept of health found in the community narrative encompasses individuals, mind, body, territory, and mother earth. In this concept, both the spiritual and the ecological elements are involved. There is no difference between health and mental health, because the latter only emphasizes the first. Disease is related to the supremacy of individual interests over community interests.

For the re-indigenized Muiscas from Cota, health and healing are holistic phenomena that surpass an individualist approach, and are connected to the universe -it is better to say multiverse- of relationships 27,28, in which performance includes consciousness, plants, sound, music, thought, spirit, territory and their connections in a syncretic web woven with ancestral and contemporary elements.

Music is a cultural element evident in most of the community's activities; it is a tool that helps strengthen and heal the community. In such context, music therapy is a transformative act when conditions are given to experience the performance. The "musicing" act allowed the emergence of special states of consciousness and the contact with the ancestral memory. In addition, it allowed the Muiscas to verify the manifestation of knowledge related to health and mental health. This knowledge could be incorporated into their new law of origin (neomuisca), which is memory and code for these people.

Acknowledgment

None stated by the authors.

References

Referencias

Benenzon R. Aplicaciones clínicas de la musicoterapia. Buenos Aires: Lumen; 2000.

Benenzon R. La nueva musicoterapia. Buenos Aires: Lumen; 1998.

Colombia. Congreso de la República. Ley Estatutaria 1751 de 2015 (febrero 16): Por medio de la cual se regula el derecho fundamental a la salud y se dictan otras disposiciones. Bogotá D.C.: Diario Oficial 49427; febrero 16 de 2015 [cited 2016 Apr 13] Available from: https://goo.gl/1iVdjT.

Lacaze D. Proyecto de construcción de la circunscripción territorial de la nacionalidad kichwa de Pastaza. In: Cruz MP, Vargas-Clavijo M, Talero GM, Sarmiento I, editors. IV Congreso Colombiano de Etnobiología: Diversidad de Saberes y Memoria Biocultural en Colombia. Bogotá D.C.: Sociedad Colombiana de Etnobiología; 2013.

Quevedo E, editor. Historia de la medicina en Colombia. Tomo I: Prácticas médicas en conflicto (1492-1782). Bogotá D.C.: Norma; 2007.

Pedraza H. Ambiente, cultura y espíritu, una mirada intencional a lo invisible. Bogotá D.C.: CAR; 2004.

Taussig M. Chamanismo, colonialismo y el hombre salvaje. Un estudio sobre el terror y la curación. 2nd ed. Popayán: Universidad del Cauca; 2012.

Albó X. Interculturalidad y salud. In: Fernández G, coordinator. Salud e interculturalidad en América Latina. Perspectivas antropológicas. Quito: Ediciones Abya Yala; 2004. p. 65-72.

Hernández C. Estado del arte en investigación sobre la salud mental y enfermedades transmisibles en los pueblos indígenas de América. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia; 2005.

Amaral de Sousa E, Luz M. Bases socioculturais das práticas terapêuticas alternativas. Hist. cienc. saude-Manguinhos. 2009;16(2):393-405.

Andrade LE. Los demonios de Darwin. Semiótica y termodinámica de la evolución biológica. Bogotá D.C.: Universidad Nacional de Colombia; 2003.

Méndez-Reyes J. Universidad, decolonización e interculturalidad otra. Más allá de la “hybris de punto cero”. Revista de Filosofía. 2013;75(3):66-86.

García-Canclini N. Interculturalidad e hibridación latino. México D.F.: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana de Iztapalapa; 1999 [cited 2016 Apr 13] Available from: https://goo.gl/1TWViT.

Walsh C. ¿Qué conocimiento(s)? Reflexiones sobre políticas de conocimientos, el campo académico y el movimiento indígena ecuatoriano. Boletín ICCI. 2001 [cited 2016 Apr 12];3(25). Available from: https://goo.gl/wEo4Tf.

Morales L. Reflexiones sobre multiculturalidad, grupos étnicos, prácticas terapéuticas y movimientos de reindigenización en Colombia. Revista de Investigaciones en Seguridad Social y Salud. 2015;17(1):77-92.

Martínez S. Poderes de la mimesis: Identidad y curación en la comunidad indígena muisca de Bosa. Bogotá D.C.: Ediciones Uniandes; 2009.

Aretz I. Síntesis de la etnomúsica en América Latina. Caracas: Monte Ávila Editores; 1981.

Zapata G, Goubert B, Maldonado J. Universidad, músicas urbanas, pedagogía y cotidianidad. Bogotá D.C.: Universidad Pedagógica Nacional; 2005.

Small C. Musicing: The meanings of performing and listening (music/culture). Middletown: Wesleyan University Press; 1998.

Stige B. Ethnography and ethnographically informed research. In: Wheeler B, editor. Music therapy research. New Braunfels: Barcelona Publishers; 2005. p. 392-403.

Wigram T, Nygaard I, Ole-Blonde L. A comprehensive guide to music therapy. Theory, clinical practice, research and training. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2002.

Pellizzari P, Rodríguez R. Salud, escucha y creatividad. Musicoterapia preventiva psicosocial. Buenos Aires: Universidad del Salvador; 2005.

Procter S. Playing politics: community music therapy and the therapeutic redistribution of musical capital for mental health. In: Pavlicevic M, Ansdell G, editors. Community music therapy. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2004. p. 214-230.

Stige B. Community music therapy: culture, care and welfare. In: Pavlicevic M, Ansdell G, editors. Community music therapy. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2004. p. 91-113.

Salamanca A, Martín-Crespo M. El muestreo en la investigación cualitativa. Nure Investigación. 2007 [cited 2016 Apr 13];27(7). Available from: https://goo.gl/uWNW36.

Bolívar A. “¿De nobis ipsis silemus?”: Epistemología de la investigación biográfico-narrativa en educación. REDIE. 2002 [cited 2016 Apr 12];4(1). Available from: https://goo.gl/EhGxgX.

Mazorco G. La descolonización en tiempos del Pachakutik. Polis. 2010;9(27):219-242.

Maturana H. La objetividad. Un argumento para obligar. Santiago de Chile: Dolmen; 1997.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Soile Hämäläinen, Anita Salamonsen, Grete Mehus, Henrik Schirmer, Ola Graff, Frauke Musial. (2021). Yoik in Sami elderly and dementia care – a potential for culturally sensitive music therapy?. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 30(5), p.404. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2020.1849364.

2. Juan Pimentel, Camila Kairuz, Claudia Merchán, Daniel Vesga, Camilo Correal, Germán Zuluaga, Iván Sarmiento, Neil Andersson. (2021). The Experience of Colombian Medical Students in a Pilot Cultural Safety Training Program: A Qualitative Study Using the Most Significant Change Technique. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 33(1), p.58. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2020.1805323.

3. David Rodríguez Goyes, Nigel South, Deisy Tatiana Ramos Ñeñetofe, Angie Cuchimba, Pablo Baicué, Mireya Astroina Abaibira. (2023). ‘An incorporeal disease’: COVID-19, social trauma and health injustice in four Colombian Indigenous communities. The Sociological Review, 71(1), p.105. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380261221133673.

4. Ntshengedzeni Evans Netshivhambe. (2023). Indigenous People - Traditional Practices and Modern Development. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.1003226.

5. Carlos Duvan Paez Mora, María Teresa Buitrago Echeverri. (2023). Tecnicidad vs Construcción Participativa, reflexiones a partir de una estrategia de Comunicación en Salud. Revista de Comunicación y Salud, 13, p.16. https://doi.org/10.35669/rcys.2023.13.e309.

Dimensions

PlumX

Visitas a la página del resumen del artículo

Descargas

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2017 Revista de la Facultad de Medicina

Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento 3.0 Unported.

-