Quality of rocoto pepper (Capsicum pubescens Ruiz & Pav.) seeds in relation to extraction timing

Calidad de semillas del ají rocoto (Capsicum pubescens Ruiz & Pav.) en relación con el momento de extracción

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/acag.v67n2.59057Keywords:

Agri-food, Andean region, seed characteristics, seed emergence, seed size, seed viability, seed vigour, sexual propagation. (en)Agroalimentaria, características de semilla, emergencia de semilla, propagación sexual, región Andina, tamaño de semilla, viabilidad de semilla, vigor de semilla. (es)

El ají rocoto (C. pubescens) es una de las especies domesticadas del género Capsicum en Suramérica. Actualmente, su oferta y demanda están en aumento tanto en el mercado nacional como global. El objetivo del estudio fue determinar el momento óptimo de extracción de las semillas de C. pubescens en función de su calidad física y fisiológica. Las mediciones de calidad incluyeron el peso de semillas, número de semillas por fruto, emergencia total, taza de emergencia, tiempo medio de emergencia, emergencia media diaria, porcentaje de sobrevivencia, valor pico y valor de emergencia. Los tratamientos fueron evaluados por comparación como sigue: (T1), extracción de semillas de 0 a 3 días después de cosecha y (T2), extracción después de 14 a 17 días, respectivamente. T1 presentó semillas con mayor calidad fisiológica y un valor de emergencia total de 84.2 %, en contraste con 74.8 % obtenido en T2. Se encontró una correlación positiva entre el tamaño y el número de semillas y la calidad de las mismas. Con base en los resultados de este estudio, se sugiere usar y conservar las semillas extraídas inmediatamente después de la cosecha, así como semillas de mayor tamaño provenientes de frutos más grandes.

Recibido: 14 de julio de 2016; Aceptado: 31 de mayo de 2017

Abstract

Rocoto pepper (C. pubescens), is one of the domesticated species of the genus Capsicum in South America. Currently, its supply and demand are arising in national and global market. The aim of this study was to determine the optimal extraction timing of the seeds of C. pubescens according to physiological and physical seed qualities. Seed qualities measurement include seed weight, number of seeds per fruit, total emergence, emergence rate, mean emergence time, mean daily emergence, survival percentage, peak value and emergence value. Treatments were evaluated for comparison as follows: seed extraction ranged from 0 to 3 days after harvest (T1), and seed extraction ranged from 14 to 17 days after harvest (T2). T1 presented seeds with the best physiological qualities and a total emergence value of 84.2%, in contrast to 74.8% obtained in T2. A positive correlation was found between seed size, number of seeds per fruit and overall quality, respectively. Based on the results of this study, is recommended to use and conserve the seeds extracted immediately after harvest, as well as larger seeds from biggest fruits.

Key words:

Agri-food, Andean region, seed characteristics, seed emergence, seed size, seed viability, seed vigour, sexual propagation.Resumen

El ají rocoto (C. pubescens) es una de las especies domesticadas del género Capsicum en Suramérica. Actualmente, su oferta y demanda están en aumento tanto en el mercado nacional como global. El objetivo del estudio fue determinar el momento óptimo de extracción de las semillas de C. pubescens en función de su calidad física y fisiológica. Las mediciones de calidad incluyeron el peso de semillas, número de semillas por fruto, emergencia total, taza de emergencia, tiempo medio de emergencia, emergencia media diaria, porcentaje de sobrevivencia, valor pico y valor de emergencia. Los tratamientos fueron evaluados por comparación como sigue: (T1), extracción de semillas de 0 a 3 días después de cosecha y (T2), extracción después de 14 a 17 días, respectivamente. T1 presentó semillas con mayor calidad fisiológica y un valor de emergencia total de 84.2 %, en contraste con 74.8 % obtenido en T2. Se encontró una correlación positiva entre el tamaño y el número de semillas y la calidad de las mismas. Con base en los resultados de este estudio, se sugiere usar y conservar las semillas extraídas inmediatamente después de la cosecha, así como semillas de mayor tamaño provenientes de frutos más grandes.

Palabras clave:

Agroalimentaria, características de semilla, emergencia de semilla, propagación sexual, región Andina, tamaño de semilla, viabilidad de semilla, vigor de semilla.Introduction

The genus Capsicum is among the most widely accepted and of global importance as an agricultural crop, which includes five domesticated species grown in Mexico, Central and South America. Fruits from Capsicum genus are used mainly for their pungency in food preparation (Ibiza, Blanca, Canizares & Nuez, 2012). In 2013, world production of this genus was led by China with 13 million tons and a yield of 22 t.ha-1; Mexico ranked second with two million tons and a yield of 17 t.ha-1 (FAOSTAT, 2015). In Colombia, the land area of Capsicum cultivation performed an arising growth in the decade from 2003 to 2013. In fact, in 2003, 3582 hectares were planted with Capsicum, while in 2013 this land area had achieved an increasing in 40000 hectares (FAOSTAT, 2015). However, total domestic production and yield per hectare declined during the same period as follows: from 44530 tons (12.43 t.ha-1) in 2003 to only 29675 tons (0.742 t.ha-1) in 2013 (FAOSTAT, 2015).

One of the South American species of the genus Capsicum is known as rocoto pepper, C. pubescens (Solanaceae). This species is cultivated in Andean ecosystems and is characterized by violet flowers and black seeds (Ibiza, Blanca, Canizares & Nuez, 2012; Espindola & Smiderle, 2014). Fruits of C. pubescens can be considered as nutraceuticals for their content of phenolic compounds, which promote optimal brain cell function by inhibiting oxidation of essential fatty acids (Oboh & Rocha, 2007). In addition, phytotoxic activity of C. pubescens extracts on weeds of the genera Amaranthus, Bidens and Ipomoea are reported (García, Sánchez, Martínez & Pérez, 2013).

One of the major factors to optimize agricultural crop production is the use of high quality seeds; this factor is associated with a higher success rate of plant establishment and improved maintenance of seed viability during seed storage life (Pittcock, 2008; Singh & Bhatia, 2009). Seeds reach its physiological maturity when the accumulation of metabolites ends, corresponding to maximum dry weight, and subsequently, starts the deterioration process (Bewley, Bradford, Hilhorst & Nonogaky, 2013).

It is known that several factors are evaluated in the search for optimal quality of Capsicum seeds. For C. annuum cv. glabriusculum (Dunal) Heiser & Pickersgill, for example; a correlation between seed weight, germination percentage, and mean germination time was found in four Capsicum populations in northwest Mexico (Hernández, López, Porras, Parra, Villareal & Osuna, 2010). In C. annuum, was compared the effect of fruit position on seed germination and seed vigor with no significant differences found for sampled positions (Araiza, Araiza & Martínez, 2011; Vallejo, García & Suárez, 1999). Ayala, Ayala, Aguilar & Corona (2014), found that physical and physiological seed qualities, measured as the weight of 1000 seeds and mean germination rate, respectively, of three seed cultivars of C. annum, have achieved an improvement when seeds were removed 15 days after fruit harvest versus immediate removal.

Empirically is known that seeds of C. annuum and C. annuum cv. glabriusculum can be removed when fruit is dried (Ayala et al., 2014). Physiological potential of C. baccatum L. and C. frutencens L. improves with a latency period of ten days after harvest (Bezerra, Barros, de Lima, Costa & Pereira, 2014; Espíndola & Smiderle, 2014). However, for cold climate, chili or chili apple, C. pubescens has not been studied and not previously conducted to determine the moment of highest physiological seed quality.

Given these concerns, the aim of this study was to determine the optimal extraction timing of the seeds of C. pubescens according to physiological and physical seed qualities based on two protocols: 0 to 3 days and 14 to 17 days after harvest (DAH). Additionally, to evaluate traditional methods of C. pubescens propagation and in turn, generate knowledge of this Andean highlands species to encourage cultivation in rural communities.

Material and methods

Plant material

Five sources of C. pubescens (Capital District and Tena, Cundinamarca, Colombia), were identified in orchards and farms in rural communities that will be integrated as suppliers of plant material into the study development (Table 1). Subsequently, from each source, ten fruits (of good quality) per plant were selected and harvested in physiological maturation stage (intense red color) (Figure 1).

Table 1: Sources of C. pubescens plant material.

Figure 1: The intense red color in rocoto pepper fruits. Evidence of physiological maturation stage.

To guaranteed seed extraction, longitudinal cuts were made on fruits using surgical masks and latex gloves (Pacheco & Zuñiga, 2007). Seed disinfection was performed by seed washing with hypochlorite water solution at concentration of 5% v/v, followed by two washes with deionized water. Subsequently, seeds were dried at room temperature for one day.

Seed propagation test

Propagation test was established in germoplasm bank at Jardin Botanico de Bogota, Colombia (N4 ° 39 '57.4 W74° 05' 59.3"), in average temperature of 15.43°C and relative humidity of 73.96. Two moments of seed extraction were compared as follows: T1 included seeds extracted from 0 to 3 DAH and T2 included seeds extracted between 14 and 17 days DAH. Seeds were planted in plastic containers at a depth of 1 cm, using as a substrate black soil, rice hull and peat (composition 40:40:20). In the study was use a paired sample test (T- test), where each replicate or pairing, it was composed by the source of plant material, using 100 seeds (sample unit) and five replicates, for a total of 1000 seeds planted.

Experiment management

Preventive management of plant pathogens during the propagation phase was carried out through the application of Trichoderma kongingii (4 g.l-1), Bacillus thuringiensis (3 g.l-1), Neem extract (5 cc.l-1) and agricultural iodine (5 cc.l-1). Nutritional management was carried out via foliar feeding with WUXAL "tapa negra" (3 cc.l1) and Tottal (7.5 cc.l-1), and edaphically with mineralized organic conditioner (10 cc.l-1) and Raizagro (5 g.l-1).

Evaluated variables

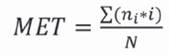

To determine seed weight of 1000 seeds (WS), the total number of seeds of ten fruits was counted and weighed (in grams) on an analytical balance scale OHAUS Galaxy 160. For total emergence (TE), the number of emerged seedlings was counted every third day (Pacheco & Zuñiga, 2007; Espindola & Smiderle, 2014). Mean emergence rate (MER), was defined as the number of seedlings that emerged in the interval i, divided by the number of days in the interval i. Mean emergence time (MET), was defined as the measurement of seed emergence time in relation to seed emergence ability (Equation 1).

Equation 1

Equation 1

Where:

is the number of seeds emerged in time i, and N = is the total number of seeds emerged 90 days after sowing (Enriquez, Suzán & Malda, 2004).

The survival rate 90 days after planting (SP) was calculated as the ratio between the number of seedlings survival and the number of emerged seeds (Cóbar, García, Pauchard & Peña, 2015). Mean daily emergence (MDE), was calculated as the average number of seedlings emerged per day. The number of seeds (NS) was measured as the total number of seeds per fruit. Peak value (PV) was defined as the maximum value calculated by dividing cumulative emergence rates by the corresponding number of days to reach said rates (Ranal & Garcia, 2006).

Seed emergence value (V) was calculated following Equation 2 ((Ranal & Garcia, 2006).

Equation 2

Equation 2

Data analysis

A Pearson correlation analysis was carried out with all the evaluated variables to determine potential interactions. T-test was used to compare the variance between paired samples. Both analyses were made with Infostat(r) 2015 software.

Results

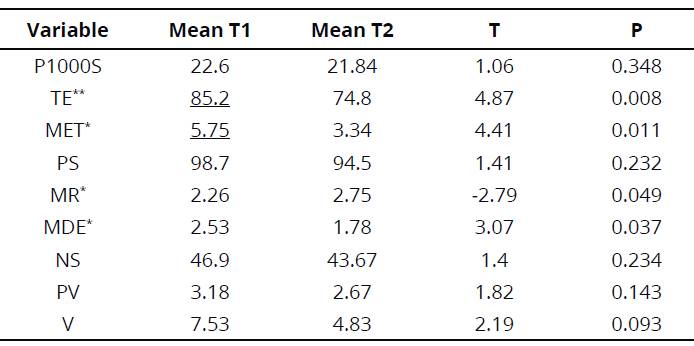

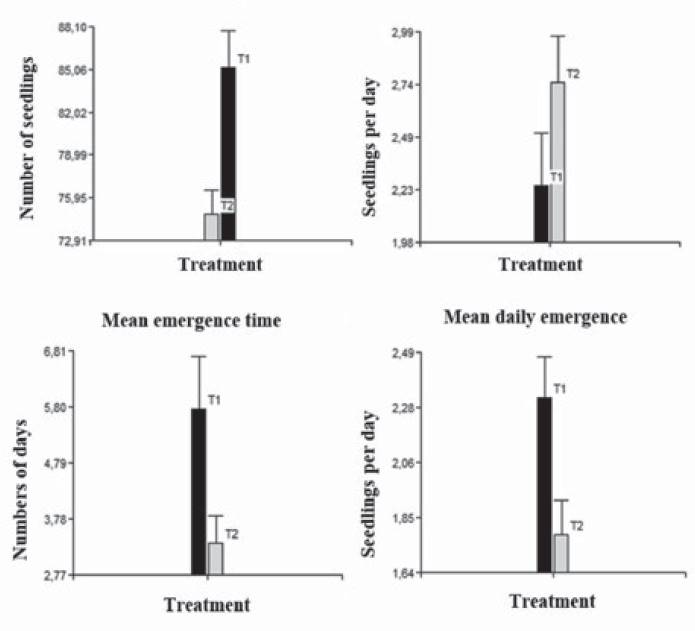

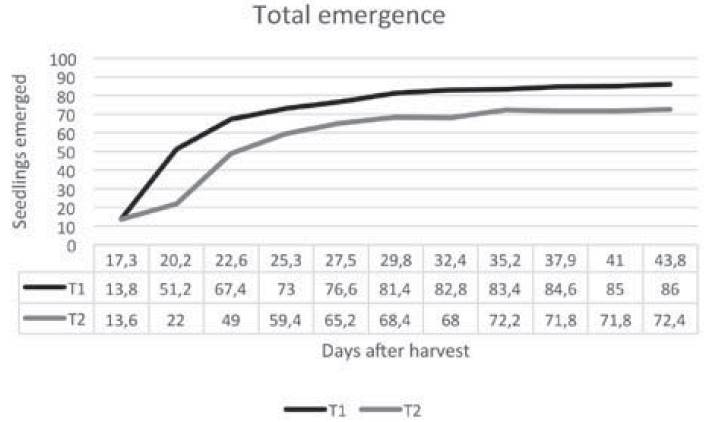

The current study found an average of 46 seeds per fruit and an average seed weight of 0.022 g. The measured variables showed the following significant differences: MET for T1 reached 5.75, while for T2 was 3.34, and MDE for T1 was 2.53, while for T2 was 1.78. TE showed a highly significant difference, which had achieved a decreasing from 85.2 for T1 to 74.8 for T2. However, MER had increased from 2.26 seeds per day for T1 to 2.75 seeds per day for T2. The WS, SP, NS, PV and V variables did not show significant differences (Table 2). Bar graphs clearly show differences among compared treatments (Figure 2); the outer boundary corresponds to the calculated experimental error. Figure 3, corresponds to the germination curves.

Figure 2: Variables that showed significant differences. T1 corresponds to seeds from 0 to 3 days after sowing and T2 to seeds extracted from 14 to 17 days after harvest.

P1000S: weight of 1,000 seeds. TE: total emergence. MET: mean emergence time. PS: survival percentage. MER: mean emergence rate. MDE: mean daily emergence. NS: Number of seeds. PV: Peak value. V: emergence value. T1: treatment 1, seeds extracted from 0 to 3 days after harvest. T2: treatment 2, seeds extracted from 14 to 17 days after harvest. The variables with the (*) sign showed significant differences and those with (**) sign showed highly significant differences.Table 2: T-test analysis for evaluated treatments.

Figure 3: Total emergence of C. pubescens seeds taken from 0 to 3 days after harvest (T1) and 14 to 17 after harvest (T2). Lower values correspond to the average obtained.

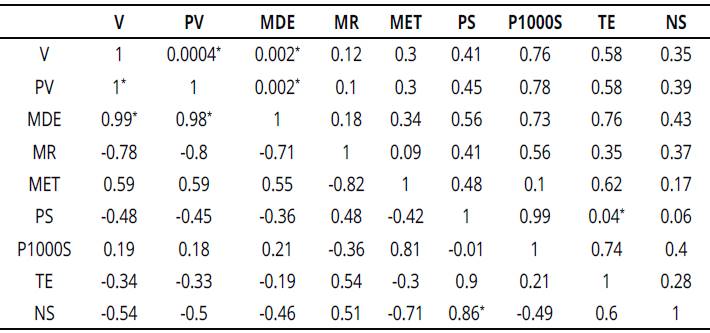

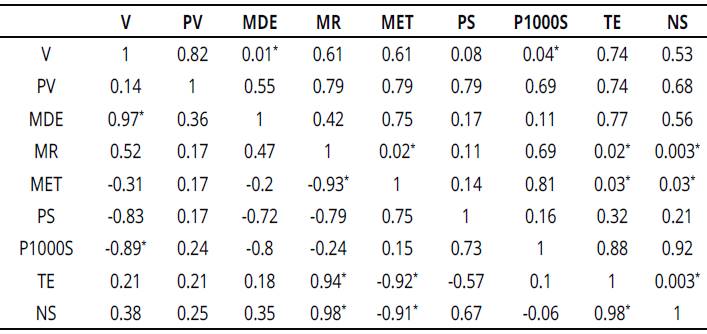

For T1 a correlation was found between V, PV and MDE, and between TE and SP (Table 3). For T2 correlation occurred between V, MDE and WS, and between MER, MET, TE and NS (Table 4).

P1000S: weight of 1000 seeds. TE: total emergence. MET: mean emergence time. PS: survival percentage. MER: mean emergence rate. MDE: mean daily emergence. NS: Number of seeds. PV: Peak value. V: emergence value. T1: treatment 1, seeds extracted from 0 to 3 days after harvest. T2: treatment 2, seeds extracted from 14 to 17 days after harvest.Table 3: Analysis of Pearson correlations between the results of treatment 1.

The results below the main diagonal correspond to the value of Pearson correlation, while the values above of the diagonal correspond to the probability associated with the null hypothesis test correlation between the jth. and the ith. variable.* The marked values highlight accepted correlations (p <0.05).

P1000S: weight of 1000 seeds. TE: total emergence. MET: mean emergence time. PS: survival percentage. MER: mean emergence rate. MDE: mean daily emergence. NS: Number of seeds. PV: Peak value. V: emergence value. T1: treatment 1, seeds extracted from 0 to 3 days after harvest. T2: treatment 2, seeds extracted from 14 to 17 days after harvest.Table 4: Analysis of Pearson correlations between the results of treatment 2.

Discussion

Average seed weight of the collected fruits were 35.1 g at harvest time, which is consistent with Zuñiga & Pacheco (2007), who reported an average weight of 33.6 g for C. pubescens.

The results suggest that C. pubescens seed development occurs at the same time of physiological fruit development and when occurs maturing (intense red color-Figure 1), seed quality starts to deteriorate (Bewley, Bradford, Hilhorst & Nonogaky, 2013; Espindola & Smiderle, 2014). However, the results are diferent for C. annuum, C. frutencens and C. baccatum (Ayala-Villegas et al., 2014; Bezerra et al., 2014; Spindola and Smiderle, 2014). In this case, the variables MET and MDE could be corroborate the synchronized phenomenon between extraction time and seed quality.

In the results of correlation analysis for T1, associations were observed between V, PV and MDE, as expected with seed emergence value, which is the mean daily seed emergence mul tiplied by peak value. In the first treatment, a direct proportionality between TE and PS was also observed, suggesting that seed quality also affects the ability of plants to adapt to environmental conditions; this is consistent with that obtained by Oboh & Rocha (2007). The findings for T2 showed a greater number of variable cor relations than T1: the average time of emergence was directly related to speed seed emergence; these results are comparable in variability to the report by Ranal & Garcia (2006), who reported it as associated variables. Another correlation of interest shows interaction between WS and MER; this can be explained by previous findings carried out by Bewley, Bradford, Hilhorst & Nonogaky (2013), who suggest that when seed has higher physical quality by weight or size, a higher phys iological seed quality occurs. Finally, NS has a positive relationship with TE, MER and MET; this positive correlation suggests that more seeds a fruit presents, higher seed emergence ability. In this sense, Marcelis & Baan Hofman-Eijer (1997), report that in Capsicum annuum L., a higher number of seeds per fruit can be translated into higher ability to compete for nutrients. In fact, an increasing in dry weight resulting from nutri ent accumulation in seeds could also be related to their physiological quality. Vallejo, García & Suárez (1999) and Araiza, Araiza & Martínez (2011), have also previously reported this positive interaction between seed size and seed weight, number of seeds per fruit, seed vigor and full seed emergence in C. annuum.

Differences between T1 and T2 correlations suggest that with higher seed quality, the ma jority could have a high seed emergence ability; however, when seeds begin to deteriorate, other variables, such as seed size and number of seeds, prevail in the overall capacity to germinate and subsequently into seed emergence. Conversely, Reveles, Velásquez, Reveles & Mena (2013), rec ommend disposal of smaller Capsicum seeds, due to their association with lower physiological seed quality. Likewise, Hernández et al. (2010), found a positive relationship between seed size and seed germination in C. annuum cv. glabriusculum. is believed to be an outcome of competition among seeds for resources during ripening, resulting in a considerable difference in seed sizes and, therefore, their seed germination ability (Escriba & Laguna, 2006).

Conclusion

This study evaluated the effects of optimal extraction timing of the seeds of rocoto pepper (C. pubescens) according to physiological and physical seed qualities. This provides more accurate and reliable estimates of sexual propagation and seed store life of C. pubescens when are immediately extracted after harvest to ensure highest physiological seed quality and taking into account the use of larger seeds from fruits with higher number of seeds.

Acknowledgments

To Jardín Botánico de Bogotá, José Celestino Mutis and Integrated Systems of Propagation team at the Scientific Office for their support in the development of this study. To Colciencias for their contribution in knowledge generation through financing the project "Andean Biodiversity to the Dish of All."

References

References

Araiza, N., Araiza, E. & Martínez, J. G. (2011). Evaluación de la germinación y crecimiento de Plántulas de Chilpetín (Capsicum annuum L. variedad glabriusculum) en invernadero. Rev Colomb Biotecnol, 13(2), 170-175. https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/biotecnologia/article/view/28006/28258.

Ayala-Villegas, M. J., Ayala-Garay, O. J., Aguilar-Rincón, V. H. & Corona-Torres, T. (2014). Evolución de la calidad de la semilla de Capsicum annum L. durante su desarrollo en el fruto. Rev Fitotec Mex, 37(1), 79-87. http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/rfm/v37n1/v37n1a11.pdf.

Bewley, J. D., Bradford, K. J., Hilhorst, W. M. H. & Nonogaky, H. (2013). Seeds. Physiology of development, germination and dormancy. 3rd Edition. Springer (Eds.). New York, USA. 380 p.

Bezerra, F. E. C., Barros, S., de Lima, M. I., Costa, L. & Pereira, C. (2014). Qualidade fisiológica de sementes de pimenta em função da idade e do tempo de repouso pós-colheita dos frutos. Revista Ciência Agronômica, 45(4), 737-744. http://ccarevista.ufc.br/seer/index.php/ccarevista/article/view/2711/1027.

Cóbar, A. J., García, R. A., Pauchard, A. & Peña, E. (2015). Efecto de la alta temperatura en la germinación y supervivencia de la especie invasora Pinus contorta y dos especies nativas del sur de Chile. Bosque, 36(1), 53-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-92002015000100006

Enriquez, E. G., Suzán, H. & Malda, G. (2004). Viabilidad y germinación de semillas de Taxodium mucronatum (Ten.) en el estado de Querétaro, México. Agrociencia, 38, 375-381. https://www.uv.mx/personal/tcarmona/files/2010/08/Enriquez-et-al-2004.pdf.

Escriba, M.C. & Laguna, E. (2006). Estudio de la germinación de Odonis tridentata L. Acta Bot Malacit, 31, 89-95. http://www.biolveg.uma.es/abm/Volumenes/vol31/31-05.ONONIS.pdf.

Espindola, J.M. & Smiderle, O.J. (2014). Qualidade fisiológica de sementes de pimenta obtidas em frutos de diferentes maturações e armazenadas, Ciências Agrárias, 35(1), 251-258. http://dx.doi.org/10.5433/1679-0359.2014v35n1p251

FAOSTAT. (2015). Statistics Division. Roma, Italia. Food and Agriculture Organization. http://faostat3.fao.org/download/Q/QC/E.

García-Mateos, M. del R., Sánchez-Navarro, C., Martínez-Solís, J. & Pérez-Grajales, M. (2013). Actividad fitotóxica de los extractos de chile manzano (Capsicum pubescens R & P). Rev Chapingo Ser Hortic, 19(4), 23-33. http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/rcsh/v19n4/v19n4a2.pdf.

Hernández, S., López, R., Porras, F., Parra, S., Villareal, M. & Osuna, T. (2010). Variación en la germinación entre poblaciones y plantas de chile silvestre. Agrociencia, 44(6), 667-677. http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/agro/v44n6/v44n6a6.pdf.

Marcelis, L. F. M. & Baan Hofman-Eijer., L. R. (1997). Effects of Seed Number on Competition and Dominance among Fruits Capsicum annum L. Annals of Botany, 79, 687-693. http://dx.doi.org/0305-7364/97/060687

Ibiza, V.P., Blanca, J., Canizares, J. & Nuez, F. (2012). Taxonomy and genetic diversity of domesticated Capsicum species in the Andean region. Genet Resour Crop Ev, 59(6), 1077-1088. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10722-011-9744-z

Oboh, G. & Rocha, J.B. (2007). Distribution and antioxidant activity of polyphenols in ripe and unripe tree pepper (Capsicum pubescens). J Food Biochem, 31(4), 456-473. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-4514.2007.00123.x

Pittcock, J.K. (2008). Seed production, processing and analysis. In: Plant Propagation. Beyl, C. A. & Trigiano, R. N. (Eds.), Plant Propagation. pp. 401-406. CRC Press Tylor & Francis Group. Boca Raton, USA.

Ranal, M.A. & García, D. (2006). How and why to measure the germination process? Rev Bras Bot, 29(1), 1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-84042006000100002

Reveles, M., Velásquez, R., Reveles, L. & Mena, J. (2013). Selección y conservación de semillas de chile: primer paso para una buena cosecha. Folleto Técnico 51. CIRNOC – INIFAP Campo Experimental Zacatecas, México (Eds.). 51 p. http://zacatecas.inifap.gob.mx/publicaciones/semillaCH.pdf.

Singh, N. & Bhatia, A. K. (2009). Vegetable seed production, Haryana Agricultural University (Eds.). Hisar, India. 43p.

Vallejo, F. A., García, M.A. & Suárez, D. (1999). Efecto de diferentes cultivares y posición del fruto sobre la producción y calidad de la semilla de pimentón, Capsicum annuum L. Acta Agron, 49(1-2), 14-17. https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/acta_agronomica/article/view/47971/49169.

Zúñiga, P.T. & Pacheco, R.A. (2007). Germinación y desarrollo de plántulas de Capsicum pubescens Ruiz & Pav. (Solanaceae) en el Jardín Botánico de Bogotá José Celestino Mutis, Bogotá. D.C. – Colombia. Pérez Arbelaezia, 18(1), 33-46.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Angel David Hernández-Amasifuen, Alexandra Jherina Pineda-Lázaro, Jorge L. Maicelo-Quintana, Juan Carlos Guerrero-Abad. (2024). In Vitro Shoot Regeneration and Multiplication of Peruvian Rocoto Chili Pepper (Capsicum pubescens Ruiz & Pav.). International Journal of Plant Biology, 15(4), p.979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb15040069.

2. Marcelo Martínez-Muñoz, Óscar J. Ayala-Garay, V. Heber Aguilar-Rincón, Víctor Conde-Martínez, Tarsicio Corona-Torres. (2019). Seed Quality and LEA-protein Expression in Relation to Fruit Maturation and Post-harvest Storage of Two Chilies Types. The Horticulture Journal, 88(2), p.245. https://doi.org/10.2503/hortj.UTD-044.

3. Miguel Merino-Valdés, Pablo Andrés-Meza, Otto Raúl Leyva-Ovalle, Higinio López- Sánchez, Joaquín Murguía-González, Rosalía Núñez-Pastrana, Miguel Cebada-Merino, Ricardo Serna- Lagunes, Alejandro Espinosa-Calderón, Margarita Tadeo-Robledo, Mauro Sierra- Macías, José Luis Del Rosario-Arellano. (2018). Influencia de tratamientos pregerminativos en semillas de chile manzano (Capsicum pubescens Ruiz & Pav.). Acta Agronómica, 67(4), p.531. https://doi.org/10.15446/acag.v67n4.73426.

4. Eloy López Medina, Angélica López Zabaleta, Armando Efraín Gil Rivero, José Mostacero León, Anthony J. De La Cruz Castillo, Luigi Villena Zapata. (2020). Morfometría de frutos y semillas del “ají mochero” Capsicum chinense Jacq.. Ciencia & Tecnología Agropecuaria, 21(3), p.1. https://doi.org/10.21930/rcta.vol21_num3_art:1598.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2018 Acta Agronómica

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Política sobre Derechos de autor:Los autores que publican en la revista se acogen al código de licencia creative commons 4.0 de atribución, no comercial, sin derivados.

Es decir, que aún siendo la Revista Acta Agronómica de acceso libre, los usuarios pueden descargar la información contenida en ella, pero deben darle atribución o reconocimiento de propiedad intelectual, deben usarlo tal como está, sin derivación alguna y no debe ser usado con fines comerciales.

>

> >

>