Potentially harmful cyanobacteria in oyster banks of Términos lagoon, southeastern Gulf of Mexico

Cianobacterias potencialmente nocivas en los bancos ostrícolas de la laguna de Términos, sureste del Golfo de México

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/abc.v23n1.65809Palabras clave:

annual cycle, cyanobacteria, eutrophication, Gulf of Mexico, harmful algal blooms. (en)cianobacterias, ciclo anual, eutrofización, florecimientos algales nocivos, Golfo de México. (es)

Descargas

Cyanobacteria inhabit hypersaline, marine and freshwater environments. Some toxic and non-toxic species can form harmful blooms. The aim of this study was to identify potentially harmful cyanobacterial species in the oyster banks of Términos Lagoon, the southeastern Gulf of Mexico. Six sample sites (up to 2-m depth) were monitored monthly from August 2012 to September 2013. Water temperature, salinity, pH, dissolved oxygen saturation (% DO), inorganic nutrients and abundance of cyanobacteria were determined. Temperature and salinity were characterized by marked seasonal differences (26.8 to 30.6 °C and 6.1 to 19.5, respectively). The pH values (ranging from 7.1 to 8.4) and the % DO (88.4 to 118.2 %) suggest a predominance of photosynthetic activity in the windy season (October-February). Elevated nutrient contents are associated with the period of increased river discharge, determined by water circulation and biogeochemical processes. Fourteen taxa were identified, of which Anabaena sp., Merismopedia sp., Oscillatoria sp. and Cylindrospermopsis cuspis produced blooms. Cyanobacterial abundances were on the order of magnitude of 106 cells L-1 in October 2012 at stations S1-S6, with an average value of 3.2x105 cells L-1 and a range of 2000 to 3.1x106 cells L-1 throughout the study period; however, they showed a remarkable absence during the windy season (October to January). Anabaena sp. and C. cuspis reached abundances of 1.9x106 and 1.3x106 cells L-1, respectively. The latter caused the temporary closure of oyster Crassostrea virginica harvesting for 15 days in October 2012.

Las cianobacterias habitan en ambientes hipersalinos, marinos y de agua dulce. Algunas especies tóxicas y no tóxicas pueden formar florecimientos nocivos. El objetivo de este estudio fue identificar las especies de cianobacterias potencialmente nocivas en los bancos ostrícolas de laguna de Términos, sureste del Golfo de México. Seis sitios de muestreo (hasta 2 m de profundidad) fueron monitoreados mensualmente de agosto de 2012 a septiembre de 2013. Se midió la temperatura del agua, salinidad, pH, saturación de oxígeno, nutrientes inorgánicos y abundancia de cianobacterias. La temperatura y la salinidad se caracterizaron por marcadas diferencias estacionales (26,8 a 30,6 °C y 6,1 a 19,5, respectivamente). Los valores de pH (de 7,1 a 8,4) y la saturación de oxígeno disuelto (de 88,4 a 118,2 %) sugieren un predominio de la actividad fotosintética en la temporada de nortes (octubre-enero). Las concentraciones elevadas de los nutrientes están asociados al periodo de mayor descarga de los ríos, determinados por la circulación y los procesos biogeoquímicos. Se identificaron 14 taxa, de los cuales Anabaena sp., Merismopedia sp., Oscillatoria sp. y Cylindrospermopsis cuspis formaron florecimientos. Las abundancias de cianobacterias fueron del orden de magnitud de 106 células L-1 en octubre de 2012 en las estaciones S1-S6, con un valor promedio de 3.2x105 células L-1 y un rango de 2000 a 3.1x106 células L-1 a lo largo del periodo de estudio. Sin embargo, mostraron una ausencia notable durante la temporada de nortes (octubre a enero). Anabaena sp. y C. cuspis alcanzaron abundancias de 1.9x106 y 1.3x106 células L-1, respectivamente. Este último causó el cierre temporal de la colecta del ostión Crassostrea virginica durante 15 días en octubre de 2012.

Recibido: 27 de junio de 2017; Revisión recibida: 13 de septiembre de 2017; Aceptado: 4 de noviembre de 2017

ABSTRACT

Cyanobacteria inhabit hypersaline, marine and freshwater environments. Some toxic and non-toxic species can form harmful blooms. The aim of this study was to identify potentially harmful cyanobacterial species in the oyster banks of Términos Lagoon, the southeastern Gulf of Mexico. Six sample sites (up to 2-m depth) were monitored monthly from August 2012 to September 2013. Water temperature, salinity, pH, dissolved oxygen saturation (% DO), inorganic nutrients and abundance of cyanobacteria were determined. Temperature and salinity were characterized by marked seasonal differences (26.8 to 30.6 °C and 6.1 to 19.5, respectively). The pH values (ranging from 7.1 to 8.4) and the % DO (88.4 to 118.2 %) suggest a predominance of photosynthetic activity in the windy season (October-February). Elevated nutrient contents are associated with the period of increased river discharge, determined by water circulation and biogeochemical processes. Fourteen taxa were identified, of which Anabaena sp., Merismopedia sp., Oscillatoria sp. and Cylindrospermopsis cuspis produced blooms. Cyanobacterial abundances were on the order of magnitude of 106 cells L-1 in October 2012 at stations S1-S6, with an average value of 3.2x105 cells L-1 and a range of 2000 to 3.1x106 cells L-1 throughout the study period; however, they showed a remarkable absence during the windy season (October to January). Anabaena sp. and C. cuspis reached abundances of 1.9x106 and 1.3x106 cells L1, respectively. The latter caused the temporary closure of oyster Crassostrea virginica harvesting for 15 days in October 2012.

Keywords:

annual cycle, cyanobacteria, eutrophication, Gulf of Mexico, harmful algal blooms.RESUMEN

Las cianobacterias habitan en ambientes hipersalinos, marinos y de agua dulce. Algunas especies tóxicas y no tóxicas pueden formar florecimientos nocivos. El objetivo de este estudio fue identificar las especies de cianobacterias potencialmente nocivas en los bancos ostrícolas de laguna de Términos, sureste del Golfo de México. Seis sitios de muestreo (hasta 2 m de profundidad) fueron monitoreados mensualmente de agosto de 2012 a septiembre de 2013. Se midió la temperatura del agua, salinidad, pH, saturación de oxígeno, nutrientes inorgánicos y abundancia de cianobacterias. La temperatura y la salinidad se caracterizaron por marcadas diferencias estacionales (26,8 a 30,6 °C y 6,1 a 19,5, respectivamente). Los valores de pH (de 7,1 a 8,4) y la saturación de oxígeno disuelto (de 88,4 a 118,2 %) sugieren un predominio de la actividad fotosintética en la temporada de nortes (octubre-enero). Las concentraciones elevadas de los nutrientes están asociados al periodo de mayor descarga de los ríos, determinados por la circulación y los procesos biogeoquímicos. Se identificaron 14 taxa, de los cuales Anabaena sp., Merismopedia sp., Oscillatoria sp. y Cylindrospermopsis cuspis formaron florecimientos. Las abundancias de cianobacterias fueron del orden de magnitud de 106 células L-1 en octubre de 2012 en las estaciones S1-S6, con un valor promedio de 3.2x105 células L-1 y un rango de 2000 a 3.1x106 células L-1 a lo largo del periodo de estudio. Sin embargo, mostraron una ausencia notable durante la temporada de nortes (octubre a enero).

Anabaena sp. y C. cuspis alcanzaron abundancias de 1.9x106 y 1.3x106 células L-1, respectivamente. Este último causó el cierre temporal de la colecta del ostión Crassostrea virginica durante 15 días en octubre de 2012.

Palabras clave:

cianobacterias, ciclo anual, eutrofización, florecimientos algales nocivos, Golfo de México.INTRODUCTION

Cyanobacteria are a diverse group of photosynthetic microorganisms with specific physiological and morphological characteristics that allow them to adapt to a wide range of habitats including pelagic and benthic environments where they are highly competitive (Liotenberg et al., 1996; Morvan et al., 1997; Oren, 2000). Some species can survive under extreme environmental conditions such as deserts, hot springs and alkaline lakes (Oren, 2000).

The growth of cyanobacteria in aquatic environments is controlled by a variety of environmental factors, and adequate nutrient conditions, temperature, hydrogen potential (pH) and illumination are required for their cultivation (Kebede and Ahlgren, 1996). Cyanobacteria can grow in both saline and non-saline environments, as well as showing a greater probability of colonizing various aquatic environments, compared to those that are strictly freshwater or halophilic (Rosales-Loaiza et al., 2004). In particular, planktonic cyanobacteria frequently proliferate in eutrophic freshwater environments; however, little is known about their role in tropical coastal environments with a certain degree of eutrophication.

Harmful algal blooms (HAB) caused by cyanobacteria affect water quality, fish resources, animals and human beings (Muciño-Márquez et al., 2015). Due to the production of excessive biomass, they can cloud the water, thereby inhibiting phytoplankton photosynthesis, and they also produce toxins, causing unpleasant odors in water, decrease the dissolved oxygen concentration and therefore its availability to consumers, and inhibit the growth of other phytoplankton species that serve as food for consumers (Echenique and Aguilera, 2009).

According to the National Fisheries Charter (Diario Oficial de la Federación, 2012), oysters are the most important resource because of their volume in the Gulf of Mexico (around 40 tons in 2012). The Gulf of Mexico contributes more than 93 % of the national oyster production. This production is mainly based on the exploitation of natural banks. Furthermore, it is one of the products with a lower price and wide acceptance because of its sanitary quality. The oyster banks in Términos Lagoon supply the local market and the areas adjacent to Ciudad del Carmen in the state of Campeche, Mexico, in the southeastern Gulf of Mexico.

The aim of this study was to identify potentially harmful cyanobacterial species in these oyster banks.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The present study was conducted in the areas of extraction of bivalve molluscs in the Lagoon of San Carlos and Puerto Rico subsystem in Términos Lagoon (Figs. 1a, 1b), located 30 km west of Ciudad del Carmen, state of Campeche (18°33-38'N, 92°01'-14'W). The area is characterized by three meteorological seasons: a dry season from February to May, a rainy season from June to September and a windy season from October to January (Yáñez-Arancibia and Day, 1982). Monthly sampling was performed in six oyster banks at up to 2-m depth, from August 2012 through September 2013 (Figs. 1a, 1b).

Figure 1: Study area: (a) the state of Campeche (shadowed), Mexico, and (a, b) location of sampling stations in oyster banks (square).

At each site surface seawater samples were collected with a plastic 500-ml bottle; an aliquot of 100 ml was used to analyze cell abundances of phytoplankton taxa (Lindahl, 1986). Samples were fixed in situ with an alkaline solution of iodine (Utermõhl, 1958) and subsequently preserved by adding 4 % neutralized formalin (Throndsen, 1978). Additionally, circular horizontal tows were performed for five minutes with a conical hand net, with a 20-μιτι mesh size, at each sampling site. The collected material was placed into glass vials and fixed using the same procedure as for the quantitative analysis to identify the cyanobacterial taxa. In situ water temperature (°C), salinity, pH and oxygen saturation (%) were measured on-board using a HANNA multiparameter probe, model HI9828, with HI769828 sensor and a HACH multiparameter probe, model HQ40d (HANNA Instruments Inc., Woonsocket, Rhode Island, USA). Orthophosphate (P-PO4 3-), ammonium (N-NH4+), nitrite (N-NO2 -) and nitrate (N-NO3 -) analyses were performed according to Strickland and Parsons (1972).

Quantification of planktonic cyanobacterial cells was determined following the Utermõhl technique (Utermõhl, 1958), taking 10 cm3 of each sample and using an inverted Carl Zeiss Axio Observer.A1 microscope equipped with phase contrast 10x/0.25 Ph1 ADL and LD 20x/0.30 Ph1 objectives. Cyanobacterial cells (<20 Mm), due to their small size, were not identified to species level. Abundance values were expressed as cells L-1. Observation and identification of cyanobacteria species were performed on fixed samples with a Motic BA310 compound microscope equipped with the planachromatic objectives 4x/0.10, 10x/0.25, 20x/0.40, 40x/0.65 and 100x/1.25, using specialized taxonomic literature.

The hypothesis of differences between months and between sampling stations was tested by analysis of variance, and Tukey TSD (Truly Significant Difference) was applied with a significance level of 0.05 (Daniel, 2002). The normality of the recorded data was assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and homoscedasticity with the Bartlett's test (Garson, 2012). The calculation routine was performed with Statgraphics Centurion XV program, version 18.2.06.

The presence and intensity of bloom of colonial or filamentous cyanobacteria were analyzed based on the ECOFRAME proposal (as described below) regarding the proportion of cyanobacteria and other major phytoplankton groups (Moss et al., 2003). The classification scheme for its application was modified for Términos Lagoon.

a) no aggregates are observed and there is no dominance (<95 %) of filaments or colonies of cyanobacteria;

b) the same situation as a), but surface formation of cyanobacteria is detected in a punctual or intermittent way;

c) dominance of filaments or colonies of cyanobacteria (>95 %) is evident and/or frequent blooms occur;

d) they do not show aggregates; however, when blooms occur, observed by cell counting and are infrequent in time, there is a dominance of «40 % of filaments or colonies of cyanobacteria.

RESULTS

Physical and chemical factors

Water temperature showed a range of temporal variability of ± 3 °C. Minimum average values (26.8-27.3 °C) were recorded during the windy season and maximum average values (29.7-30.6 °C) during the rainy season (Table 1). Salinity minimum average values were measured in the windy season (6.1-8.7), and maximum average values during the dry season, with a range of 17.4-19.5 (Table 1). Minimum mean pH values were observed during the dry season (6.97.3), while the maximum mean was registered during the windy season, with a range of 7.9-8.4 (Table 1). Minimum average oxygen saturation values were recorded in the rainy season (88.4-96.3 %), while maximum average values (106.2118.2 %) were observed in the dry season (Table 1). All the variables mentioned above showed significant differences between seasons (p< 0.05).

*Significant differences SD (jt>< 0.05, ANOVA nonparametric one-way) between the seasons.Table 1: Summary statistics (by meteorological season) of environmental variables and nutrients at six sampling sites in the oyster banks of Términos Lagoon, Campeche, Mexico, in 2012-2013 (mean, range and standard deviation).

Environmental variables

Nutrients (pmol L-1)

Season

T°C

Salinity

pH

D. O (%)

Nitrite

Nitrate

Ammonium

Phosphate

30.2

13.2

7.6

93.2

0.97

2.20

2.10

0.30

Rainy

29.7-30.6

11.6-14.3

7.4-7.8

88.4-96.3

0.30-3.40

1.31-3.42

1.15-3.79

0.14-0.60

±0.37

±0.15

±0.15

±2.82

±1.26

±0.83

±1.12

±0.18

27.0

7.4

8.2

104.6

0.58

1.09

3.16

0.38

Windy

26.8-27.3

6.1-8.7

7.9-8.4

98.9-111.8

0.04-3.39

0.47-2.26

2.80-3.64

0.20-0.63

±0.19

±1.12

±0.18

±4.73

±1.24

±0.70

±0.31

±0.17

28.0

18.4

7.1

112.2

0.17

0.78

1.80

1.05

Dry

27.8-28.4

17.4-19.5

6.9-7.3

106.2-118.2

0.07-0.35

0.54-1.28

1.62-2.05

0.73-1.52

±0.25

±0.13

±0.13

±5.03

±0.09

±0.28

±0.19

±0.30

SD ^ season

F= 260.1*

F= 225.1*

F= 64.8*

F= 44.5*

F= 53.3*

F= 11.9*

F= 6.5*

F= 15.2*

Nutrients

Variations in the concentrations of the inorganic nutrients were relatively wide (Table 1). Average concentrations of nitrite (N-NO2 -) and nitrate (N-NO3 -) were low throughout the study compared to ammonium. However, nitrite concentrations showed maximum values, ranging from 0.30 to 3.40 Mimol L-1, in the rainy season (Table 1). Nitrate concentrations showed maximum values ranging from 1.31 to 3.42 Mmol L-1 in the rainy season and minimum values (0.54-1.28 Mmol L-1) in the dry season (Table 1). Minimum ammonium (N-NH4+) concentrations were observed in the dry season (1.62-2.05 Mmol L-1), while maximum concentrations (2.80-3.64 Mmol L-1) were observed in the windy season (Table 1). Orthophosphate (P-PO4 3-) concentrations showed minimum average values (0.14-0.60 Mmol L-1) during the rainy season, while maximum average values (0.73-1.52 Mmol L-1) were registered during the dry season (Table 1). All the variables mentioned above showed significant differences between seasons (p< 0.05).

Cyanobacterial abundance

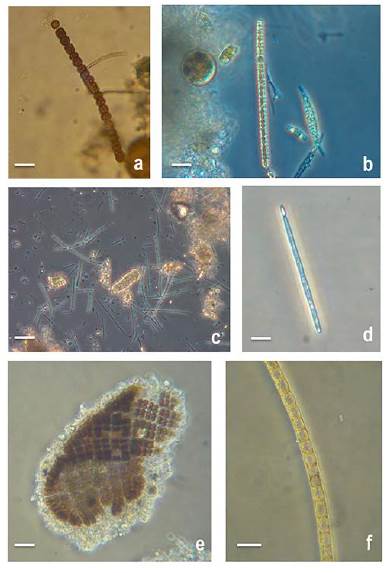

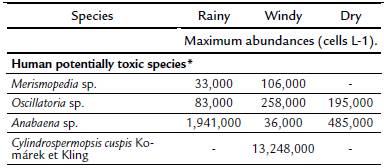

Fourteen taxa were identified, of which Anabaena sp., Merismopedia sp., Oscillatoria sp. and Cylindrospermopsis cuspis formed blooms. Cyanobacterial abundance increased by orders of magnitude to 106 cells L-1 in the windy season (October), and small peaks were also observed in the dry and rainy seasons (Fig. 2). Among cyanobacteria, the genus Anabaena Bory de Saint-Vincent was present throughout the study period, with a maximum abundance of 1.9x106 cells L-1 and a minimum abundance of 3.6x104 cells L-1 (Table 2, Fig. 4g). Merismopedia sp. and Oscillatoria sp. showed maximum abundances of 1.0x105 and 2.5x105 cells L-1, respectively, in the windy season (Table 2, Figs. 4d, 4e). During the windy season, a bloom of Cylindrospermopsis cuspis was recorded with 1.3x106 cells L-1, and it lasted throughout the season with an abundance of up to 2.4x103 cells L-1 (Table 2, Fig. 4a, c).

Figure 2: Temporal variation of cell abundances of cyanobacteria in the oyster banks of Términos Lagoon, Campeche, Mexico, in 20122013.

*Species known as potentially toxic: microcystin LR, lipopolysac-charide (LPS), microcystin, anatoxin-a, anatoxin-a (S), saxitoxin, cylin-drospermopsin, neusaxitoxin and neosaxitoxin (Bonilla, 2009).Table 2: List of potentially harmful cyanobacteria observed at six sampling sites during three seasons in the oyster banks of Términos Lagoon, Campeche, Mexico, in 2012-2013.

Figure 3: Contribution of cyanobacteria (%) to the total microalgae abundance at stations S1-S6 in the oyster banks of Términos Lagoon, Campeche, Mexico, in 2012-2013.

Figure 4: Micrographs of potentially harmful cyanobacteria in the oyster banks of Términos Lagoon, Campeche, Mexico: a, b) Anabaena spp.; c, d) Cylindrospermopsis cuspis; e) Merismopedia sp.; g) Anabaena sp. Scale bar = 10 μm

Percentage of cyanobacteria

The percentages of cyanobacteria with respect to the rest of phytoplankton were based on cell abundances (Fig. 3). At station S6 located at the entrance of the lagoon, a lower percentage of cyanobacteria (28 %) was observed (Fig. 3). Phytoplankton microalgal major groups showed the greatest contribution when cyanobacteria were not abundant. It should be noted that cyanobacteria were more frequent and with high abundances with only 14 species corresponding to 17 % of the total number of phytoplankton species.

DISCUSSION

The water temperature variation during the study period is in accordance with the values reported by Robadue et al. (2004) and Yáñez-Arancibia and Day (2005) for Términos Lagoon during at least 50 years, and, in general, it is characteristic of a subtropical marine environment. The salinity range, which varied seasonally, was highest during the rainy season. According to Ramos-Miranda et al. (2006), this reflects the seasonal change in insolation, which results in greater evaporation and hence in a higher concentration of salts in the dry months. During the rainy season, the high freshwater input from rainfall and/or water discharges inundates the entire lagoon, inducing a marked salinity gradient (Hernández-Guevara et al., 2008). Only the Palizada River discharges approximately 75 % of the total fresh water that reaches the lagoon increasing by 20 % in the elevation of the water surface of the lagoon (Bach et al., 2005; Kuc-Castilla et al., 2015). This behavior was coinciding with that observed during the study period.

The values of pH and oxygen saturation suggested high activity of primary producers in the water column, resulting in changes in water quality (especially in pH and dissolved oxygen) as reported by Martínez-López et al. (2006), Hakspiel-Segura (2009) and Escobedo-Urías (2010) for coastal lagoons of the northwestern Mexican Pacific. The average values of nitrite, nitrate and ammonium recorded in different seasons were well below the values reported by Contreras-Espinoza et al. (1996), Herrera-Silveira et al. (2002) and Ramos-Miranda et al. (2006) for the southern Gulf of Mexico. However, the same pattern of high values in the rainy season, coupled with the proximity of river mouths with strong freshwater influence, can be seen (Yáñez-Arancibia and Day, 2005). High values of orthophosphate and silicate are associated with the period of increased river discharge determined by circulation and biogeochemical processes (Ramos-Miranda et al., 2006).

The tides, the discharge of fresh water and the local winds are linked to the period of high river discharge by rainfall enriching the waters at the entrance with new nutrients and causing high turbidity and low salinity (Yáñez-Arancibia and Day, 2005).

In the study area the presence of cyanobacteria is an anthropogenic pressure indicator. This feature is reinforced where salinity values are low and the relative proportion of cyanobacteria in biomass can be used as an indicator of eutrophication, as shown in Figure 3, where the highest percentages with respect to abundances were found at stations S1, S3 and S4, classified as brackish (salinity «14). This indicator has been reinforced because of the increase in terrestrial temperature, leading to an increase in cyanobacterial proliferations in continental ecosystems (Jõhnk et al., 2008), closely associated with eutrophication (Anderson et al., 2012). In general, cyanobacteria exhibit a cosmopolitan distribution, inhabiting hypersaline, marine and freshwater environments, and therefore have a wider range of habitats than phototrophic eukaryotes (Mur et al., 1999; Graham and Wilcox, 2000; Whitton and Potts, 2002; Ludeña-Hinojosa, 2007). Estuaries produce variations in salinity depending on the quantities of fresh water entering, and these changes give cyanobacteria an advantage over other competitors (Domingues et al., 2005, Lanzarot-Freudenthal, 2007).

In the study area cyanobacteria were present on the order of magnitude of 106 cells L-1, mainly due to Anabaena sp. and Cylindrospermopsis cuspis with abundances of 1.9x106 and 1.3x106 cells L-1, respectively. In October 2012, C. cuspis caused the temporary closure for 15 days of oyster (Crassostrea virginica Gmelin) harvesting (Poot-Delgado et al., 2016), decreed by Mexican governmental agencies based on the number of cells. Both species of cyanobacteria have been recorded in the fluvial-lagoon subsystems Pom-Atasta and Palizada del Este, adjacent to the study area, with abundances of 1.5x103 and 0.5 to 8.2x103 cells L-1, respectively (Muciño-Márquez et al., 2014; Muciño-Márquez et al., 2015). Cylindrospermopsis cuspis was reported in the region of Los Tuxtlas in the southeastern part of the state of Veracruz (Komárek and Komárková-Legnerová, 2002; Komárek, 2003), with no apparent toxic episodes.

Cahuich-Sánchez (2016) performed a prospective study of lipophilic and hydrophilic marine toxins in Crassostrea virginica collected monthly during the period from 2012 to 2015 in the oyster field Playazo (station 6 in this study). He records the presence of diarrheic and other lipophilic toxins known as emerging toxins, due to the clinical signs observed in the mouse bioassay model, probably attributable to cyanobacteria. However, this must be confirmed by an analytical method (e.g., HPLC-UV).

Cyanobacterial blooms have been recurring in various water bodies in the state of Veracruz, such as Catemaco Lake, where the mass proliferation of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (Wotosz.) Seenayya et Subba Raju was recorded, causing a high degree of bioaccumulation of the toxin cylindrospermopsin produced by this species throughout the food chain (Berry and Lind, 2010). In the coastal lagoon of Alvarado, Dolichospermum flos-aquae (Bréb. ex Bornet et Flahault) P. Wacklin, L. Hoffmann et J. Komárek recorded a bloom of 91x106 cells L-1 in October 2013 (Aké-Castillo and Campos-Bautista, 2014).

Another species of cyanobacteria was Merismopedia sp. at the end of the rainy season (June-September) and dry season (February-May), with abundances of approximately 105 cells L-1. According to Moreno-Ruiz (2000) and John et al. (2002), this is a genus indicative of water with moderate pollution. Some species of the genera of Anabaena, Aphanizomenon Morren ex Bornet et Flahault, Lyngbya C. Agardh ex Gomont, Microcystis Lemmerm. , Oscillatoria Vaucher ex Gomont, Phormidium Kütz. ex Gomont and Schizothrix Kütz. ex Gomont produce compounds with an earthy and moldy odor (geosmin), representing a nuisance in the drinking water industry, growing areas and recreational lakes (Chorus and Bartram, 1999; Landsberg, 2002).

In recent decades cyanobacteria proliferations have increased markedly in continental freshwater and coastal marine ecosystems throughout the world, mainly due to increased eutrophication of water bodies (Chorus and Bartram, 1999; Acevedo-Torrano, 2012). However, despite their intrinsic importance, in Mexico the toxins produced by cyanobacteria have been reported during the last 15 years only from freshwater environments (Pica-Granados and Ramírez-Romero, 2012). Studies of cyanobacteria and their toxins in brackish and marine waters are therefore urgently needed.

CONCLUSIONS

Temperature and salinity were characterized by marked seasonal differences. The values and oxygen saturation suggested a predominance of photosynthetic activity in the windy season (October-February). At stations S1-S6 cyanobacteria were present on orders of magnitude of 106 cells L-1 in October 2012; however, they were notably absent in the windy season. Anabaena sp. and Cylindrospermopsis cuspis reached abundances of 1.9x106 and 1.3x106 L-1 cells, respectively. Cylindrospermopsis cuspis caused a 15-day temporary closure of the oyster Crassostrea virginica extraction activity in October 2012.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sergio Poot-Delgado and Juan C. Lira-Hernández for providing support in the field, Martin Memije-Canepa for laboratory analyses of water samples, and Fausto R. Tafoya del Ángel for institutional coordination. We also thank Marcia M. Gowing from the University of California at Santa Cruz, California, USA, who kindly improved the writing style. The financial support given to FOMIX-CONACYT-Campeche State Government project "Determinación del estado sanitario de los complejos ostricolas del municipio del Carmen" (2012-2014) given to JRO is much appreciated. Anonymous reviewers kindly improved the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Referencias

Acevedo-Torrano V. Floraciones de cianobacterias en el Uruguay: niveles guía y descriptores ambientales (tesis profesional). Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de la República; 2012. 49 p.

Aké-Castillo JA, Campos-Bautista G. Bloom of Dolichospermum flos-aquae in a coastal lagoon in the southern Gulf of Mexico. HAN. 2014;9,12.

Anderson DM, Cembella AD, Hallegraeff GM. Progress in understanding harmful algal blooms: paradigm shifts and new technologies for research, monitoring, and management. Ann Rev Mar Sci. 2012;4:143-176. Doi:10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-081121

Bach L, Calderón R, Cepeda MF, Oczkowski A, Olsen SB, Robadue D. Resumen del perfil de primer nivel del sitio Laguna de Términos y su cuenca, México. 1 ed. Narragansett: Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island; 2005. 30 p.

Berry JP, Lind O. First evidence of "paralytic shellfish toxins" and cylindrospermopsin in a Mexican freshwater system, Lago Catemaco, and apparent bioaccumulation of the toxins in "tegogolo" snails (Pomacea patula catemacensis). Toxicon. 2010;55:930-938. Doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.07.035

Bonilla S, editor. Cianobacterias planctónicas del Uruguay: Manual para la identificación y medidas de gestión. Documento Técnico PHI-LAC 16. Montevideo, Uruguay: UNESCO; 2009. 96 p.

Cahuich-Sánchez YR. Evaluación de toxinas lipofílicas e hidrofílicas en el “ostión americano” Crassostrea virginica y el pez “torito” Acanthostracion quadricornis de las costas de Campeche (tesis profesional). Champotón, Campeche, México: Instituto Tecnológico Superior de Champotón; 2016. 105 p.

Chorus I, Bartram J, editors. Toxic cyanobacteria in water: A guide to their public health consequences, monitoring and management. London, New York, UK, USA: E y FN Spon; 1999. 400 p.

Contreras-Espinoza F, Castañeda LO, Torres-Alvarado R, Gutiérrez MF. Nutrientes en 39 lagunas costeras mexicanas. Rev Biol Trop. 1996;44(2):417-425.

Daniel WW. Bioestadística. Base para el análisis de las ciencias de la salud. 4 ed. México: Editorial Limusa Wiley; 2002. 915 p.

Diario Oficial de la Federación. Acuerdo por el que se da a conocer la actualización de la Carta Nacional Pesquera. México, D.F., México: Secretaria de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación; 2012. 236 p.

Domingues RB, Barbosa A, Galvão H. Nutrients, light and phytoplankton succession in a temperate estuary (the Guadiana, south-western Iberia). Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2005;64(2-3):249-260. Doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2005.02.017

Echenique RO, Aguilera A. Floraciones de Cyanobacteria toxígenas en la República Argentina: antecedentes. In: Giannuzzi L, Colombi A, Pruyas T, Aun A, Rujana M, Falcione M, Zubieta J, editors. Cianobacterias y cianotoxinas: identificación, toxicología, monitoreo y evaluación de riesgo. Corrientes, Provincia de Corrientes, Argentina: Moglia Impresiones; 2009. p. 37-51.

Escobedo-Urías D. Diagnóstico y descripción del proceso de eutrofización en lagunas costeras del norte de Sinaloa (tesis doctoral). La Paz, Baja California Sur, México: Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas-Instituto Politécnico Nacional; 2010. 298 p.

Garson D. Testing statistical assumptions. 1 ed. Raleigh, North Carolina, USA: Statistical Associates Publishing; 2012; 52 p.

Graham L, Wilcox W. Algae. 1 ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall; 2000; 720 p.

Hakspiel-Segura C. Variación estacional de la trama trófica microbiana en la laguna de Macapule, Sinaloa (tesis de maestría). La Paz, Baja California Sur, México: Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas-Instituto Politécnico Nacional; 2009. 189 p.

Hernández-Guevara NA, Ardisson PL, Pech D. Temporal trends in benthic macrofauna composition in response to seasonal variation in a tropical coastal lagoon, Celestun, Gulf of Mexico. Mar Freshwater Res. 2008;59:772-779. Doi:10.1071/MF07189

Herrera-Silveira JA, Silva-Casarín R, Alfonso de Almeida PS, Villalobos-Zapata GJ, Medina-Gómez I, Espinal-González JC. et al. Análisis de la calidad ambiental usando indicadores hidrobiológicos y modelo hidrodinámico actualizado de laguna de Términos, Campeche. Mérida, Yucatán, México: Informe Técnico. CINVESTAV-Mérida, EPOMEX-Campeche, UNAM-México, D.F., México; 2002. 187 p.

John DM, Whitton BA, Brook AJ. The freshwater algal flora of the British Isles. 1 ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002; 702 p.

Jöhnk KD, Huisman J, Sharples J, Sommeijer B, Visser PM, Stroom JM. Summer heatwaves promote blooms of harmful cyanobacteria. Glob Change Biol. 2008;14:495-512. Doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01510.x

Kebede E, Ahlgren G. Optimum growth conditions and light utilization efficiency of Spirulina platensis (=Arthrospira fusiformis) (Cyanophyta) from Laka Chitu, Ethiopia. Hydrobiologia. 1996;332:99-109. Doi:10.1007/BF00016689

Komárek J. Coccoid and colonial cyanobacteria. In: Wehr JD, Sheath RG, editors. Freshwater algae of North America. Ecology and classification. London, UK: Academic Press; 2003. p. 59-116.

Komárek J, Komárková-Legnerová J. Preparation of the world cyanobacterial database. In: Shimura J, Wilson KL, Gordon D, editors. Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop of Species 2000. Res Rep NIES. Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan; 2002;171:64-69.

Kuc-Castilla AG, Posada-Vanegas G, Vega-Serratos BE. Evaluación hidrodinámica de la laguna de Términos. In: Ramos-Miranda J, Villalobos-Zapata GJ, editors. Aspectos socioambientales de la región de la laguna de Términos, Campeche. Campeche, Campeche, México: Universidad Autónoma de Campeche; 2015. p. 145-166.

Landsberg JH. The effects of harmful algal blooms on aquatic organisms. Rev Fish Sci. 2002;10(2):113-390. Doi:10.1080/20026491051695

Lanzarot-Freudenthal MP. Cianobacterias tóxicas y mortandades en mesa de fauna salvaje en las marismas de Doñana (tesis de doctorado). Madrid, España: Universidad Complutense de Madrid; 2007. 162 p.

Lindahl O. A dividable hose for phytoplankton sampling. In: Report of the Working Group on Phytoplankton and Management of Their Effects. International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, C.M. 1986/L: 26, Annex 3. 1986; 3 p.

Liotenberg S, Campbell D, Rippka R, Houmard J, de Marsac NT. Effect of the nitrogen source on phycobiliprotein synthesis and cell reserves in a chromatically adapting filamentous cyanobacterium. Microbiology. 1996;142(Pt 3):611-22. Doi:10.1099/13500872-142-3-611

Ludeña-Hinojosa Y. Cianobacterias en la bahía de Mayagüez: abundancia, distribución y su relación con las propiedades bio-ópticas (tesis de Maestría). San Juan, Puerto Rico: Universidad de Puerto Rico; 2007. 130 p.

Martínez-López A, Escobedo-Urías D, Ulloa-Pérez AE, Band-Schmidt C. Bloom of Chattonella subsalsa in a eutrophic coastal lagoon in the Gulf of California. Harmful Algae News. 2006;31:4-5.

Moreno-Ruíz JL. Fitoplancton. In: De la Lanza G, Hernández S, Carbajal JL, editors. Organismos indicadores de la calidad del agua y de la contaminación (bioindicadores). México, D.F., México: SEMARNAP/Plaza y Valdés; 2000. p. 43-108.

Morvan H, Gloaguen V, Verbret L, Joset F, Hoffmann L. Structure-function investigations on capsular polymers as a necessary step for new biotechnological applications: The case of the cyanobacterium Mastigocladus laminosus. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1997;35(9):671-683.

Moss B, Stephen D, Álvarez C, Bécares E, van de Bund W, Collings SE, et al. The determination of ecological status in shallow lakes–a tested system (ECOFRAME) for implementation of the European Water Framework Directive. Aquat Conserv. 2003;13:507-549.

Muciño-Márquez RE, Figueroa-Torres MG, Aguirre-León A. Composición fitoplanctónica en los sistemas fluvio-lagunares Pom-Atasta y Palizada del Este, adyacentes a la Laguna de Términos Campeche, México. Acta biol Colomb. 2014;19(1):63-84. Doi:10.15446/abc.v19n1.38032

Muciño-Márquez RE, Figueroa-Torres MG, Aguirre-León A. Cianofitas de los sistemas fluvio-lagunares Pom-Atasta y Palizada del Este, adyacentes a la Laguna de Términos, Campeche, México. Polibotánica. 2015;39:49-78.

Mur L, Skulberg O, Utkilen H. Cyanobacteria in the environment. In: Chorus I, Bartram J, editors. Toxic cyanobacteria in water: A guide to public health significance, consequences, monitoring and management. London, New York, UK, USA: E y FN Spon; 1999. p. 15-40.

Oren A. Salts and brines. In: Whitton A, Potts M, editors. The ecology of cyanobacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. p. 281-306.

Pica-Granados Y, Ramírez-Romero P, editors. Contribuciones al conocimiento de la ecotoxicología y química ambiental en México. Jiutepec, Morelos, México: Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua; 2012. 508 p.

Poot-Delgado CA, Okolodkov YB, Aké-Castillo JA, Rendón-von Ostén J. Bloom of Cylindrospermopsis cuspis in oyster beds of Términos Lagoon, southeastern Gulf of Mexico. Harmful Algae News. 2016;53:10.

Ramos-Miranda J, Flores-Hernández D, Ayala-Pérez LA, Rendón-von Osten J, Villalobos-Zapata G, Sosa-López A. Atlas hidrológico e ictiológico de la laguna de Términos. Campeche, Campeche, México: Universidad Autónoma de Campeche; 2006. 173 p.

Robadue D, Oczkowski A, Calderon R, Bach L, Cepeda MF. Characterization of the region of the Terminos Lagoon, Campeche, Mexico: Draft for discussion. Narragansett: The nature conservancy coastal resources center. Kingston, Rhode Island, USA: University of Rhode Island; 2004. 51 p.

Rosales-Loaiza N, Loreto C, Bermúdez J, Morales E. Intermediate renewal rates enhance the productivity of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. in semicontinuous cultures. Cryptogamie Algol. 2004;25(2):207-216.

Strickland JD, Parsons TR. A practical handbook for the seawater analysis. J Fish Res Board Can. 1972;167:1-310. Doi:10.1002/iroh.19700550118

Throndsen J. Preservation and storage. In: Sournia A, editor. Phytoplankton manual. Monographs on Oceanographic Methodology 6. Paris, France: UNESCO; 1978. p. 69-74.

Utermöhl H. Zur vervolkommung der quantitative. Phytoplankton-Methodik. Verh. Internat. Verein. Theor Angew Limnol. 1958;9:1-38.

Whitton BA, Potts M, editors. The ecology of cyanobacteria. Their diversity in time and space. London and Moscow: Kluwer Acad. Publ., NY, Boston, Dordrecht; 2002. 669 p.

Yáñez-Arancibia A, Day JW. Ecological characterization of Términos Lagoon, a tropical lagoon-estuarine system in the Southern Gulf of Mexico. Oceanol Acta. 1982;5(4):431-440.

Yáñez-Arancibia A, Day JW. Ecosystem functioning: the basis for sustainable management of Terminos Lagoon, Campeche, México. 1 ed. Jalapa: Institute of Ecology A.C; 2005; 77 p.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Juan Alfredo Gómez-Figueroa, Jaime Rendón-von Osten, Carlos Antonio Poot-Delgado, Ricardo Dzul-Caamal, Yuri B. Okolodkov. (2023). Seasonal Response of Major Phytoplankton Groups to Environmental Variables along the Campeche Coast, Southern Gulf of Mexico. Phycology, 3(2), p.270. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology3020017.

2. Yiqiang Huang, Yucheng Shen, Shouzhi Zhang, Yang Li, Zeyu Sun, Mingming Feng, Rui Li, Jin Zhang, Xue Tian, Wenguang Zhang. (2022). Characteristics of Phytoplankton Community Structure and Indication to Water Quality in the Lake in Agricultural Areas. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10 https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.833409.

3. Carlos Antonio Poot-Delgado, Jaime Rendón-von Osten, Yuri B. Okolodkov, Maurilio Lara-Flores. (2022). Water quality assessment in the coastal zone of Campeche, southeastern Gulf of Mexico. Cymbella Revista de investigación y difusión sobre algas, 7(3), p.79. https://doi.org/10.22201/fc.24488100e.2021.7.3.1.

4. Carlos Antonio Poot Delgado, Jaime Jaime Rendón von Ostén, Yuri B. kolodkov, Erick J. Núñez Vázquez, Alfredo Pérez Morales. (2025). Avances y perspectivas en el estudio del fitoplancton nocivo en el litoral de Campeche, sureste del golfo de Mexico. JAINA Costas y Mares ante el Cambio Climático, 7(1), p.5. https://doi.org/10.26359/52462.0701.

5. Khandakar Zakir Hossain, Israt Jahan, Md Nayeem Hossain, Afshana Ferdous, Md. Ramzan Ali, Md Moshiur Rahman, Mohammad Sadequr Rahman Khan, Md Asaduzzaman. (2025). Feeding selectivity and gametogenic cycle of Crassostrea madrasensis in relation to seasonal plankton and environmental variability in the southeast coast of the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh. Journal of Sea Research, 208, p.102646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seares.2025.102646.

6. Juan Eduardo Sosa-Hernández, Kenya D. Romero-Castillo, Lizeth Parra-Arroyo, Mauricio A. Aguilar-Aguila-Isaías, Isaac E. García-Reyes, Ishtiaq Ahmed, Roberto Parra-Saldivar, Muhammad Bilal, Hafiz M. N. Iqbal. (2019). Mexican Microalgae Biodiversity and State-Of-The-Art Extraction Strategies to Meet Sustainable Circular Economy Challenges: High-Value Compounds and Their Applied Perspectives. Marine Drugs, 17(3), p.174. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17030174.

7. Ernesto Cabrera‐Becerril, Annie May Ek García‐García, María Luisa Núñez Resendiz, Kurt M. Dreckmann, Abel Sentíes. (2025). Taxonomic History and State of Knowledge of the Marine Species in Nostocales (Cyanoprokaryote) From the Mexican Atlantic. Ecology and Evolution, 15(8) https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.71826.

8. Carlos E. Paz-Ríos, Atahualpa Sosa-López, Yassir E. Torres-Rojas. (2024). Spatiotemporal Configuration of Hydrographic Variability in Terminos Lagoon: Implications for Fish Distribution. Estuaries and Coasts, 47(8), p.2554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-023-01250-6.

9. Amin Mahmood Thawabteh, Hani A Naseef, Donia Karaman, Sabino A. Bufo, Laura Scrano, Rafik Karaman. (2023). Understanding the Risks of Diffusion of Cyanobacteria Toxins in Rivers, Lakes, and Potable Water. Toxins, 15(9), p.582. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins15090582.

10. David Alexis Hernández-Ángeles, Alejandra Siliceo-Pacheco, Alejandra Torres-Ariño. (2026). Cianobacterias, sus toxinas, afectaciones y control de florecimientos nocivos. Cymbella Revista de investigación y difusión sobre algas, 11(2), p.121. https://doi.org/10.22201/fc.24488100e.2025.11.2.3.

Dimensions

PlumX

Visitas a la página del resumen del artículo

Descargas

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2017 Acta Biológica Colombiana

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución 4.0.

1. La aceptación de manuscritos por parte de la revista implicará, además de su edición electrónica de acceso abierto bajo licencia Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY NC SA), la inclusión y difusión del texto completo a través del repositorio institucional de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia y en todas aquellas bases de datos especializadas que el editor considere adecuadas para su indización con miras a incrementar la visibilidad de la revista.

2. Acta Biológica Colombiana permite a los autores archivar, descargar y compartir, la versión final publicada, así como las versiones pre-print y post-print incluyendo un encabezado con la referencia bibliográfica del articulo publicado.

3. Los autores/as podrán adoptar otros acuerdos de licencia no exclusiva de distribución de la versión de la obra publicada (p. ej.: depositarla en un archivo telemático institucional o publicarla en un volumen monográfico) siempre que se indique la publicación inicial en esta revista.

4. Se permite y recomienda a los autores/as difundir su obra a través de Internet (p. ej.: en archivos institucionales, en su página web o en redes sociales cientificas como Academia, Researchgate; Mendelay) lo cual puede producir intercambios interesantes y aumentar las citas de la obra publicada. (Véase El efecto del acceso abierto).