Systematic review: An approach to identifying health inequalities through case studies

Revisión sistemática: un enfoque para identificar desigualdades en salud a través de estudios de casos

Keywords:

Health Equity, Healthcare Disparities, Case reports (en)equidad en salud, Disparidades en Atención de Salud, Reportes de caso. (es)

Introduction: Health inequalities, among other factors, reflect the wellbeing level of a population. Interventions aimed at eliminating or preventing such inequalities require an understanding of their origins.

Objective: To perform a systematic review to identify case studies reporting health inequalities worldwide.

Methodology: Case reports, case studies and case series written in English, Spanish and Portuguese reporting health inequalities were included. Databases like Medline and EMBASE, and grey literature sources such as LILACS, OpenGrey, Google, and others were included.

Results: Initially, the search produced 1272 articles. 139 articles were selected by their title, while, based on their abstract, 28 articles were chosen for full text reading. Finally, 23 articles were included. Gender difference was the most frequent factor in terms of health inequalities (23.2%), followed by socio economic condition (20%), belonging to a migrant population (13.3%), ethnic origin (13.3%), age (10%), geographic origin (3.3%), and others (16.6%).

Discussion: This approach, which is based on reviewing case reports to study health inequalities, contrasts with the majority of the studies carried out in this field. This research proposes to study inequalities specific to population groups that suffer such inequalities within communities in a particular geographic area and are not able to access to optimal health services.

Introducción: las desigualdades en salud, entre otros factores, reflejan el nivel de bienestar de una población. Para realizar intervenciones dirigidas a eliminar o prevenir estas desigualdades es necesario comprender su origen.

Objetivo: realizar una revisión sistemática para identificar estudios de casos en los que se reportan desigualdades en salud en todo el mundo.

Metodología: en este estudio se incluyeron reportes de caso, estudios de casos y series de casos, escritos en inglés, español y portugués, en los que se informan desigualdades en salud. Se utilizaron bases de datos como Medline y EMBASE, así como fuentes de literatura gris como LILACS, OpenGrey, Google, entre otras.

Resultados: la búsqueda inicial arrojó 1272 artículos; de los cuales se seleccionaron 139 por su título; luego, basándose en su resumen, se escogieron 28 para realizar una lectura completa. Finalmente se incluyeron 23 artículos. En términos de inequidad en salud, la diferencia de género fue el factor más frecuente (23.2%), seguido por condición socioeconómica (20%), pertenecer a una población migrante (13.3%), origen étnico (13.3%), edad (10%), origen geográfico (3.3%) y otros (16,6%).

Discusión: este enfoque, que se basa en la revisión de reportes de caso para estudiar las desigualdades en salud, contrasta con la mayoría de estudios que se han realizado al respecto. En esta investigación se propone analizar las desigualdades en salud que son específicas a poblaciones que viven dentro de comunidades en un área geográfica en particular y que no tienen acceso a servicios óptimos de salud.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW: AN APPROACH TO IDENTIFYING HEALTH INEQUALITIES THROUGH CASE STUDIES

Palabras clave: Equidad en salud; Desigualdades en la atención en salud; Reportes de caso.

Keywords: Health Equity; Healthcare Disparities; Case reports.

Rafael Adrián Gómez Suárez • Angélica Milena Tarquino Bojacá

Anderson Aparicio Mejía • María Carolina Nossa Ramos

Camilo Andrés Alarcón González • Lizeth Andrea Prieto Puerto

Juan Pablo ALzate • Adriana C. Villada Ramirez

Equity-in-Health Research Group Seedbed

Hospital Universitario Nacional de Colombia,

Faculty of Medicine – Universidad Nacional de Colombia

Bogotá, D.C. – Colombia

Javier Eslava-Schmalbach

Equity-in-Health Research Group Seedbed

Hospital Universitario Nacional de Colombia,

Faculty of Medicine

Universidad Nacional de Colombia,

Technology Development Center

Sociedad Colombiana de Anestesiología y Reanimación

Bogotá, D.C. – Colombia

Corresponding author:

Javier Eslava–Schmalbach

Hospital Universitario Nacional de Colombia,

Universidad Nacional de Colombia

– Bogota Campus –

Bogota, D.C. – Colombia.

Email: jheslavas@unal.edu.co

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Health inequalities, among other factors, reflect the wellbeing level of a population. Interventions aimed at eliminating or preventing such inequalities require an understanding of their origins.

Objective: To perform a systematic review to identify case studies reporting health inequalities worldwide.

Methodology: Case reports, case studies and case series written in English, Spanish and Portuguese reporting health inequalities were included. Databases like Medline and EMBASE, and grey literature sources such as LILACS, OpenGrey, Google, and others were included.

Results: Initially, the search produced 1272 articles. 139 articles were selected by their title, while, based on their abstract, 28 articles were chosen for full text reading. Finally, 23 articles were included. Gender difference was the most frequent factor in terms of health inequalities (23.2%), followed by socio economic condition (20%), belonging to a migrant population (13.3%), ethnic origin (13.3%), age (10%), geographic origin (3.3%), and others (16.6%).

Discussion: This approach, which is based on reviewing case reports to study health inequalities, contrasts with the majority of the studies carried out in this field. This research proposes to study inequalities specific to population groups that suffer such inequalities within communities in a particular geographic area and are not able to access to optimal health services.

Rev Case Rep. 2016; 2(1): 37–52

INTRODUCTION

Health inequities are differences in health that are “avoidable, unfair, and unjust”. The latter occur when systematic differences in social, economic, demographic or geographic scenarios are present in one or more aspects of health across populations or population groups (1). However, other authors have defined equity in health on the basis that “resource allocation and access [to health] are determined by health needs” (2).

Inequalities in health, among other things, show people’s wellbeing level and the resources available to them (3), which means that the greater the inequality in health in a group, the greater the probability of having a low level of wellbeing, high rates of morbidity and mortality, and insufficient or inequitably distributed resources (4,5). This topic has been studied both in Latin America (6,7,8) and around the world (9,10,11), with the objective of modifying public policies regarding interventions in health determinants and proposing “Health in All Policies” (12).

Although mortality rates in the 20th century notably decreased in all countries (especially First World countries), inequalities in mortality by social class between countries and between social classes have increased (13). Even in countries with high revenues, inequalities can be found depending on geographic location (14). Society changes, diseases vary, and health services expand and improve, but the gradient of unfairness and avoidable health differences constantly increases (15). Frequently, the so-called “inverse care law” comes into play, that is, often the quality of health care is inversely related to the needs of the population (16).

Case reports have become a valuable tool when describing, evaluating and comparing certain populations. Case reports have also been and continue to be a rich and constant source of learning, research problems and questions, which makes them the “first level of evidence” for later research and interventions on a larger scale (17).

A conceptual definition of health inequalities is insufficient when attempting to understand issues in health that derive from these inequalities. Thus, a deeper understanding on how they are generated and the type of events that may lead to their appearance is necessary (18, 19). Additionally, they can be presented from an access to services perspective: horizontal inequalities —when the problem lies in the lack of access to equal resources in a population with given needs— or, on the contrary, vertical inequalities —whey they show up among individuals who, due to having greater needs, in theory, should receive more resources, something that never happens— (20).

There are many indexes that measure inequalities. One of them is the Gini coefficient, which measures to what extent an economy is inconsistent with a perfectly equitable distribution. Another important index is the Gender Inequality Index, which reflects inequality between genders in three dimensions: reproductive health, empowerment and labor market. For example, the result obtained from the Gender Inequality Index for the world was 0.451 in 2014, while in Colombia it was 0.460 (21). This index shows a higher inequality between genders in Colombia when compared to the rest of the world. The inequity-in-health index was developed with the intention of measuring this kind of inequities based on the Millennium Development Goals, established in September 2000 (22).

Although, the study of inequalities and inequities in health has been focused on conceptual frameworks, the analysis of indexes and indicators is a way to measure them, as well as to understand the role of determinants in health. Furthermore, it is not well known how much information on inequities in health has been reported through case studies or case reports. Therefore, the objective of this study is to perform a systematic review that identifies case studies reporting health inequalities worldwide.

METHODOLOGY

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In this study a qualitative systematic review was performed, presenting the evidence descriptively in accordance with the guidelines established in PRISMA (23). As a unit of study, individuals in a situation of inequality in terms of health were considered. Case reports, case studies and case series reporting inequalities or inequities in health were included.

Among excluded articles are those that were not case reports, case series or case studies; those that reported health inequalities in non-human populations; papers written in languages other than English, Spanish, or Portuguese; articles with no relation to the objective of this review, and articles with incomplete information (title or abstract).

Sources of information

The searching sources that were used include OVID, EMBASE and other sources for finding scholarly articles such as Google Scholar, LILACS, and OpenGrey. Searches were performed using a series of terms under the PICOT model for research questions. The terms used include health, inequity, inequality, marginalization, primary health care, public policy, justice, coverage, exclusion, service, access, difference, disability and quality of life. These terms were used in relation to population, intervention, results, and treatment (Annex 1).

Boolean operators were used together with controlled (Emtree, MeSH) and uncontrolled terms. Truncators were also used to include synonyms, acronyms and spelling variations of each term.

Medline database was only accessed through the OVID search engine. Searches in EMBASE were restricted to only those studies contained in this database. The search of grey literature was performed with LILACS, Open- Grey, and the Google search engine by using Spanish-language terms.

Search strategies

Searches in electronic databases and grey literature were performed in July 2015. The work was distributed as follows:

• Two researchers (CAA and AAM) performed searches in grey literature.

• One researcher (RAG) searched in Medline.

• Three researchers (AMT, MCN, LAP) searched in EMBASE.

Articles deriving from the initial search at Google were obtained by combining search terms randomly while respecting the PICOT question. No filters were applied.

Study selection

Independently, and taking the inclusion and exclusion criteria into account, each researcher, based on the title and abstract of each paper, made a selection of the articles consulted in the search source assigned to them. A table was made in order to list the articles selected, thus eliminating repeated titles.

Later, the researchers were paired up randomly to review the articles that were selected by performing a full reading of these texts while considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Disagreements were solved through a consensus decision and, in cases where a consensus was not reached, a third reviewer decided if the article should be included or not.

Data collection and analysis

An Excel table was created with an established format in order to show the main characteristics of each study. Each pair of researchers filled out the table independently. Once finished, the tables were compared in order to solve disagreements and unify the results through the participation of a third researcher (ACV). These disagreements were resolved through a consensus.

Bias was measured in relation to the selection, procedures performed during the research and evident conflicts related to financing or resource sources. The bias was classified into high risk, low risk and unclear risk categories. High risk category was chosen when the article presented problems in terms of providing the same guarantees among the different cases studied. Low risk was chosen when the article clearly showed its financing, and its methodology did not favor one result from a case report over the obtained in another report. Unclear risk was selected when methodology and financing were not included in the paper and therefore the guarantees with respect to its writing were not clarified.

Quality of the systematic review

The AMSTAR criteria (24) were used as a tool for measuring this systematic review. Scores in the AMSTAR from 7 and higher obtained in the evaluation of the quality of systematic reviews are considered as good quality. These criteria provided a favorable score, which proves this review as a valid study. In general terms, it is necessary to point out that the research question and the inclusion criteria were established before starting the review. Also, two independent individuals were involved in the study selection and data extraction, while disagreements were solved afterwards.

RESULTS

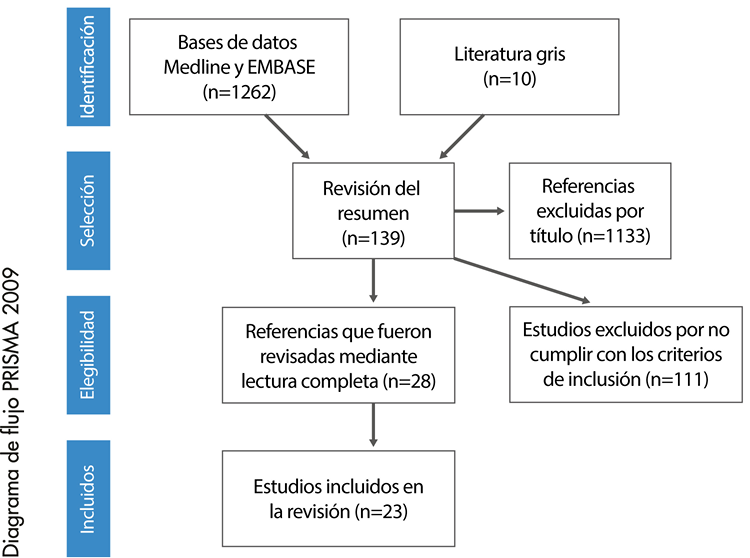

A total of 23 articles were selected since they complied with the abovementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. Below (Figure 1) it is presented a flow diagram in which the selection process of the studies in different databases is described in detail.

Fig 1. Flow diagram of the studies included in the review.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study

1272 articles were found in the initial search. The inclusion and exclusion criteria previously described were applied to them. 139 articles were selected based on their titles. Then, based on their abstracts, 28 articles were chosen for a complete reading. Finally, 23 of 28 were included in the review.

Description of the studies

Through this review it was possible to demonstrate different types of inequalities in health both in developed and developing countries, as it can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Main characteristics of the studies included.

|

Authors and year of publication |

Title |

Studied countries |

Type of study |

Population in condition of inequality |

Inequality reported |

Qualitative evaluation of bias |

|

Chatty D, Mansour N, Yassin N. 2013 (25) |

Bedouin in Lebanon: Social discrimination, political exclusion, and compromised health care |

Lebanon |

Case study |

Nationalized population |

Unequal access to health systems experienced by the non-nationalized population. |

Low risk of bias |

|

Abadia CE, Oviedo DG. 2009 (26) |

Bureaucratic Itineraries in Colombia. A theoretical and methodological tool to assess managed-care health care systems |

Colombia |

Case study |

Population with socio-economic differences |

Differences in health care based on health insurance plan. |

Unclear risk of bias |

|

Brimacombe MB, Heller DS, Zamudio S. 2007 (27) |

Comparison of fetal demise case series drawn from socioeconomically distinct counties in New Jersey |

USA |

Case series |

Gestating women |

Socio-economic inequalities between two counties and their implications on the number of stillbirths. |

High risk of bias |

|

Yang JS. 2008 (28) |

Contextualizing immigrant access to health resources |

USA |

Case study |

Immigrant population |

Unequal access to health systems experienced by the Chinese immigrant population in San Francisco, USA |

Unclear risk of bias |

|

Sypek S, Clugston G, Phillips C. 2008 (29) |

Critical health infrastructure for refugee resettlement in rural Australia: case study of four rural towns |

Australia |

Case study |

Immigrant population |

Access to health services among the refugee population in rural Australia. |

Low risk of bias |

|

Karam- Calderón MA, Bustamante- Montes P, Campuzano- González M, Camarena Pliego A. 2007 (30) |

Social aspects of maternal mortality. A case study in the State of Mexico, Mexico |

Mexico |

Case study |

Gestating women |

Socio-economic inequalities with an effect on maternal mortality. |

Unclear risk of bias |

|

Bogenschutz M. 2014 (31) |

“We Find a Way”: Challenges and facilitators for health care access among immigrants and refugees with intellectual and developmental disabilities |

USA |

Case study |

Migrant population with disabilities |

Challenges that immigrants with disabilities face in order to access health services. |

Unclear risk of bias |

|

Källander K, Hildenwall H, Waiswa P, Galwango E, Peterson S, Pariyo G. 2008 (32) |

Delayed care seeking for fatal pneumonia in children aged under five years in Uganda: a caseseries study |

Uganda |

Case series |

Children between 1 and 59 months old |

Delay in access to health services leading to infant mortality due to pneumonia. |

Low risk of bias |

|

Hacker J, Stanistreet D. 2004 (33) |

Equity in waiting times for two surgical specialties: a case study at a hospital in the North West of England |

England |

Case study |

Women, elderly adults and persons with a low socioeconomic level. |

Women, the elderly and those with a low socio-economic level experience longer waiting times for procedures in areas such as orthopedics and ophthalmology. Non-conclusive results with respect to ethnicity are provided. |

Low risk of bias |

|

Harrington BE, Smith KE, Hunter DJ, Marks L, Blackman TJ, McKee L et al. 2009 (34) |

Health inequalities in England, Scotland and Wales: stakeholders´ accounts and policy compared |

England, Wales and Scotland |

Case series |

General population. |

Starting in 2003- 2005, the three countries needed to consider lifestyle and individual responsibility when assigning clinical priority. Access to health services was an important factor in health inequalities. |

Unclear risk of bias |

|

Furler J, Harris E, Harris M, Naccarella L, Young D, Snowdon T. 2007 (35) |

Health inequalities, physician citizens and professional medical associations: an Australian case study |

Australia |

Case study |

Medical students and physicians |

Results indicate that even in areas of professional obligation there was a tendency to overcome financial barriers to improve access to health care. |

Unclear risk of bias |

|

Oosterhoff P, Anh NT, Yen PN, Wright P, Hardon A. 2008 (36) |

HIV-positive mothers in Viet Nam: using their status to build support groups and access essential services. |

Vietnam |

Case study |

HIV-positive mothers and their children |

Access to on-time care for both the mother and her child. |

Unclear risk of bias |

|

Campbell J, Buchan J, Cometto G, David B, Dussault G, Fogstad H et al. 2013 (37) |

Human resources for health and universal health coverage: fostering equity and effective coverage |

Brazil, Ghana, Mexico, and Thailand |

Case study |

General population |

The study demonstrates that with an increase in health personnel, maternal and newborn health numbers improved considerably |

Unclear risk of bias |

|

Mumtaz Z, Salway S, Shanner L, Bhatti A, Laing L. 2011 (38) |

Maternal deaths in Pakistan: intersection of gender, caste and social exclusion |

Pakistan |

Case study |

Women and children |

It assesses the inequality regarding the access to fuel for domestic chores in a rural area. It associates exposure to air pollution with mothers’ health and low weights in newborns. |

Low risk of bias |

|

El Arifeen S, Hill K, Ahsan KZ, Jamil K, Nahar Q, Streatfield PK. 2014 (39) |

Maternal mortality in Bangladesh: a Countdown to 2015 country case study |

Bangladesh |

Case series |

2 gestating women |

Two gestating women that belonged to a low-income caste did not get proper care for complications in childbirth, which in turn caused their deaths. |

Unclear risk of bias |

|

Crawley J, Kane D, Atkinson-Plato L, Hamilton M, Dobson K, Watson J. 2013 (40) |

Needs of the hidden homeless- No longer hidden: a pilot study |

Canada |

Case studies |

Individuals experiencing a socio-economic inequality (drug addicts) |

Inequity in access to health services due to the stigma of having an addiction to psychoactive substances. |

Unclear in the article |

|

Zoidze A, Rukhazde N, Chkhatarashvili K, Gotsadze G. 2013 (41) |

Promoting universal financial protection: health insurance for the poor in Georgia - a case study |

Georgia |

Case studies |

Individuals with socio-economic inequalities |

Total expenses and costs of hospitalizing people and those resulting from ambulatory care when going from private insurance to “medical insurance for the poor” |

Unclear in the article |

|

Mumtaz Z, Levay A , Bhatti A, Salway S. 2013 (42) |

Signalling, status and inequities in maternal healthcare use in Punjab, Pakistan |

Pakistan |

Case studies |

Women with socio-economic differences |

Inequalities in health care in pregnant women residing in a rural area with a strong hierarchy |

Unclear in the article |

|

Harper-Bulman K; McCourt C. 2002 (43) |

Somali refugee women’s experiences of maternity care in west London: a case study |

West London |

Case studies |

Women discriminated because of their ethnicity and their condition as migrants |

Differential access to health services in an ethnic minority of Somali gestating women in London. |

High risk of bias |

|

Y, Xiong X, 1.53 Xue Q, Yao L, Luo F, Xiang L. 2013 (44) |

The impact of medical insurance policies on the hospitalization services utilization of people with schizophrenia: A case study in Changsha, China |

China |

Case studies |

Urban population |

The study reports changes in health care that may occur in a single population treated by different companies that provide medical care in China |

Low risk of bias |

|

E, Lefevbre C, James R. 1991 (45) |

Transferring community-based interventions to new settings: a case study in heart health cholesterol testing from urban USA to rural Australia |

Pawtucket, USA / North Coast, Australia |

Case studies |

Chronic patients coming from a specific geographical origin |

Inequalities in health care for chronic diseases between rural and urban populations are reported. |

High risk of bias |

|

Türkkan A, Aytekin H. 2009 (46) |

Socioeconomic and health inequality in two regions of Turkey |

Bursa, Turkey |

Case studies |

People with socio-economic inequalities |

The study states that in the city of Bursa the health of those who live in areas with a lower socio-economic level is worse than those living in the most prosperous areas. |

Low risk of bias |

|

de Andrade LO, Pellegrini Filho A, Solar O, Rígoli F, de Salazar LM, Serrate PC et al. 2015 (47) |

Social determinants of health, universal health coverage, and sustainable development: case studies from Latin American countries. Universal health coverage in Latin America |

Brasil, Chile, Colombia and Cuba. |

Case studies |

General population |

The article presents differences between countries regarding the implementation of public policies for the control of contagious diseases, the improvement in terms of experience, and the results obtained from early childhood development and conditional monetary transfers aimed at guaranteeing health rights, education and the easing of poverty. |

Low risk of bias |

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

As seen in Table 1, the following inequalities in health stand out: tardiness in the provision of the requested care (33), difficulties in accessing primary health care (37) and difficulties in accessing care with the necessary complexity level to attend to special situations (42). Additionally, differences in the provision of health services for vulnerable populations in both public and private sectors were observed (25). In other studies, different types of approaches to public policies with respect to inequities in health were found, which shows a slight reduction in inequities where there was a larger access to health coverage and quality primary care (27,34). In general, inequities continuity among vulnerable populations was proved.

In developed countries, cases of inequalities were mainly related to the lack of health care access in migrant population (28,29) due to language limitations or their exclusion by health administrators or health providers because of their ethnicity or their condition as illegal immigrants with a lower socio-economic level (43). Among the non-migrant population, inequities in terms of health care were reported as being caused by differences in economic revenues, type of health insurance (41) and public policies that do not adapt to the social differences between the individuals of a population (45). In addition, health inequalities in populations with some sort of disability —such as physical and mental disabilities— or dependency on psychoactive substances were shown (40).

In developing countries, in particular, inequalities related to socio-economic level (26,45) and lower access to health services in populations located in sparsely inhabited areas far from large cities were reported. These factors were linked to cultural conditioners that increase inequity, especially in terms of access to quality services for women and children. The increase in mortality from both treatable and preventable diseases was very worrying (31,36,37). Several articles reported differences in timely access to the health system among pregnant women as an important indicator of inequality (30,42). Others reported favorable changes in maternal mortality through the study of inequities in health as a determining factor (37,39).

Table 2 shows the percentages of the populations that experienced inequities in health according to the articles included in this review. Table 3 includes the criteria used to exclude articles in the last round of exclusions.

Table 2. Populations suffering inequities in health.

|

Population in condition of inequity |

Number of articles where the population was the object of an inequity* |

Percentage |

|

Gender |

7 |

23.20% |

|

Socio-economic level |

6 |

20% |

|

Others |

5 |

16.60% |

|

Ethnic group |

4 |

13.30% |

|

Migrant population |

4 |

13.30% |

|

Age |

3 |

10% |

|

Geographical origin |

1 |

3.30% |

|

Level of education |

0 |

0% |

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

Note: The same article could have been included in more than one condition of inequity. Categories of inequity are not mutually exclusive.

Table 3. Excluded studies.

|

Short reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

De Brouwere V, Richard F, Witter S. 2010 (48) |

The articles were not case studies, case reports, case series or they had incomplete information. |

|

Padhi BK, Padhy PK, Jain VK. 2010 (49) |

|

|

Stolt R, Winblad U. 2009 (50) |

|

|

Maberley D, Hollands H, Chang A, Adilman S, Chakraborti B, Kliever G. 2007 (51) |

|

|

Carmichael A, Williams HE. 1983 (52) |

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

Assessment of risk of bias

Each study classification can be found in Table 1. In general terms, the studies showed an unclear risk of bias since most of them did not include complete information on their financing and the methodologies used by the researchers.

DISCUSSION

The identification of inequalities in health in global population, and the conditions that predispose them, is an object of study in the new millennium given the need of analyzing the countries’ performance in relation to the Millennium Development Goals. Thus, we attempted to include case studies, case reports and case series from all over the world published in different databases. A search criteria that follow the specifications of PRISMA was used and predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. This study shows that there are researchers publishing case studies as a way to point out inequities in health in specific populations worldwide.

23 case studies, case reports and case series reporting inequalities in health were included, while several types of populations that have been exposed to some sort of inequity were identified. After comparing inequalities between developed and developing countries, notable differences in the equitable access to health care became evident. It was observed that inequalities were caused by inadequate public policies and different types of health systems, in addition to difficult cultural and geographical conditions. Populations identified in a situation of inequality can be associated to several factors that include: gender (23.2%), low socio-economic condition (20%), immigrant condition (13.3%), belonging to an ethnic group (13.3%), age (10%), geographical origin (3.3%), and other factors (including health care providers and incapacitating diseases) (16.6%). Several studies around the world, carried out with other methodologies, also have shown that these indicators are related to inequalities in health (52,53,54,55,56).

Other studies, including more case reports, are requested to show the role of inequities in health in the wellbeing of the population, even more when indexes, trends and indicators show persistence or even an increasing tendency in some countries (57), and when equity is in the common language of politicians and decision makers in such countries.

Agreements and disagreements with previous studies

No systematic reviews of case reports, case series and/or studies describing inequalities in health were found, therefore, this study presents a new way to perform searches on inequalities in health researches: through case studies.

Applicability of the results

The results of this review provide a way to approach the gaps that exist in different health systems (26). In the Colombian context, it is possible to identify the inequalities in health described in this review, although studies carried out with different methodologies have also shown inequalities in our country (58, 59, 60). This information may be important to identify the needs of the Colombian population, to propose interventions with positive impacts and to adapt and give place to public policies that aim to mitigate exclusion and to avoid vulnerability in the population.

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review allows to bring visibility to health inequalities in systems around the world, some of which are rarely described in regular research. Likewise, it makes a decisive contribution to health since, in addition to identifying inequalities in health, it highlights the approaches adopted by the main societal actors in emerging and developed countries in terms of inequality, as observed in the results and discussion previously described.

This study emphasizes the fact that in the very 21st century, case reports, case studies and case series show a noteworthy inequality in access to health care related to gender and low socio-economic condition, despite the global policies established to ensure equal treatment.

Most of these studies are sponsored by NGOs or third party countries. Reason why it is possible to infer a probable disinterest of the country or region where the inequities in health care are found. The inequalities in health identified were largely determined by a socio- economic level factor that led to a differential access to health services, both primary and specialized. Special interest should be taken in public policies in order to reduce the existing social and economic gaps through effective interventions that account for the population in a situation of inequity in terms of health care availability. Furthermore, public policies and other sectors apart from the health sector should also be included in the restructuration of the current Colombian health system. However, more studies and strategies for identifying and reducing socio-economic inequalities in a greater proportion are needed. More typification of the shortcomings of current health services is also necessary.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

None stated by the authors.

DECLARATION OF TRANSPARENCY

The lead author* affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study reported; that no important aspects of it have been omitted, and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

*Gómez RA

REFERENCES

1.Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Serv. 1992;22(3):429-45. http://doi.org/fwhz5n.

2.Aday LA, Fleming GV, Anderson RM. An overview of current access issues. In: Access to Medical Care in the U.S.: Who Have It, Who Don’t. 1:1–18. Chicago: Pluribus Press/University of Chicago; 1984. p. 229.

3.Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:167-94. http://doi.org/dv6m6f.

4.Wagstaff A. Poverty and health sector inequalities. Bull World Health Organ. 2002 [cited 2016 Aug 24];80(2):97-105. Available from: http:// goo.gl/GTNmTn.

5.Angell M. Privilege and health -- What is the connection? N Engl J Med. 1993;329(2):126-7. http://doi.org/b6bjwz.

6.Dachs JN, Ferrer M, Florez CE, Barros AJ, Narváez R, Valdivia M. Inequalities in health in Latin America and the Caribbean: descriptive and exploratory results for self-reported health problems and health care in twelve countries. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2002;11(5-6):335- 55. http://doi.org/bqh365.

7.Ruiz-Gómez F, Zapata-Jaramillo T, Garavito- Beltrán L. Colombian health care system: results on equity for five health dimensions, 2003-2008. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2013;33(2):107-15. http://doi.org/bpq4.

8.Soberón Acevedo G, Narro J. Equidad y atención de salud en América Latina. Principios y dilemas. Bol Oficina Sanit Panam. 1985;99(1):1-9.

9.Hattersley L. Trends in life expectancy by social class: an update. Health Statistics Quarterly. 1999;(2):17-24.

10.van Doorslaer E, Masseria C, Koolman X, OECD Health Equity Research Group. Inequalities in access to medical care by income in developed countries. CMAJ. 2006 Jan 17;174(2):177-83. http://doi.org/bn8r3f.

11.Cardona D, Acosta LD, Bertone CL. Inequidades en salud entre países de Latinoamérica y el Caribe (2005-2010). Gac Sanit. 2013;27(4):292-7. http://doi.org/f2f6t3.

12.Jackson SF, Birn AE, Fawcett SB, Poland B, Schultz JA. Synergy for health equity: integrating health promotion and social determinants of health approaches in and beyond the Americas. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2013 [Cited 2016 Aug 24];34(6):473-80. Available from: http://goo.gl/LZ681M.

13.Marmot M, Bobak M, Smith GD. Explanations for social inequalities in health. In: Amick III BC, Levine S, Tarlov AR, Chapman D, Coord. Society & Health. Nueva York: Oxford University Press; 1995. 070 p.

14.Murray CJL, Michaud CM, McKenna MT, Marks JS. U.S. Patterns of Mortality by County and Race: 1965-1994. Cambridge: Harvard Burden of Disease Unit, Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies; Atlanta: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; 1998.

15.Kmietowicz Z. Gap between classes in life expectancy is widening. BMJ. 2003;327(7406):68. http://doi.org/bktfpg.

16.Tudor Hart J. The Inverse Care Law. Lancet. 1971;207(7696):405-412. http://doi.org/ fwq2sv.

17.Romaní-Romaní F. Reporte de caso y serie de casos: una aproximación para el pregrado. CIMEL. 2010 [Cited 2016 Aug 24];15(1):46-51. Available from: goo.gl/x8zlOV.

18.Sen A. ¿Por qué la equidad en salud?. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2002;11(5-6):302-9. http:// doi.org/dbdrnx.

19.Khalid M, editor. Human Development Report 2014. Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience. New York: United Nations Development Programme; 2014.

20.Starfield B. The hidden inequity in health care. |. 2011;10:15. http://doi.org/ fgq68w.

21.Braveman P. Monitoring equity in health: a policy- oriented approach in low-and middle-income countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998 [Cited 2016 Aug 24]. Available from: http://goo.gl/FQ84sP.

22.Eslava-Schmalbach J, Alfonso H, Oliveros H, Gaitan H, Agudelo C. A new Inequity-in-Health Index based on Millenium Development Goals: methodology and validation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(2):142-50. http://doi.org/cwg8v3.

23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264-9. http://doi.org/bpq5.

24.Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10. http://doi. org/dcqvfj.

25.Chatty D, Mansour N, Yassin N. Bedouin in Lebanon: Social discrimination, political exclusion, and compromised health care. Soc Sci Med. 2013; 82:43-50. http://doi.org/bpsq.

26.Abadia CE, Oviedo DG. Bureaucratic Itineraries in Colombia. A theoretical and methodological tool to assess managed-care health care systems. Soc Sci Med. 2009; 68(6):1153-60. http://doi.org/cgvgdc.

27.Brimacombe MB, Heller DS, Zamudio S. Comparison of fetal demise case series drawn from socioeconomically distinct counties in New Jersey. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2007;26(5-6):213- 22. http://doi.org/cv8373.

28.Yang JS. Contextualizing immigrant access to health resources. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(3):340-53. http://doi.org/cj8x2p.

29.Sypek S, Clugston G, Phillips C. Critical health infrastructure for refugee resettlement in rural Australia: case study of four rural towns. Aust J Rural Health. 2008;16(6):349-54. http:// doi.org/dqrfh8.

30.Karam-Calderón MA, Bustamante-Montes P, Campuzano-González M, Camarena Pliego A. Aspectos sociales de la mortalidad materna. Estudio de caso en el Estado de México. Medicina Social. 2007 [cited 2016 Aug 24]; 2(4):205-11. Available from: http://goo.gl/MGEG1R.

31.Bogenschutz M. “We Find a Way”: Challenges and facilitators for health care access among immigrants and refugees with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Med Care. 2014;52(10 Suppl 3):S64-70. http://doi.org/bpsr

32.Källander K, Hildenwall H, Waiswa P, Galwango E, Peterson S, Pariyo G. Delayed care seeking for fatal pneumonia in children aged under five years in Uganda: a case-series study. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(5):332-8. http://doi.org/dh88xd.

33.Hacker J, Stanistreet D. Equity in waiting times for two surgical specialties: a case study at a hospital in the North West of England. J Public Health (Oxf). 2004;26(1):56-60. http://doi.org/ bckjqv.

34.Harrington BE, Smith KE, Hunter DJ, Marks L, Blackman TJ, McKee L, et al. Health inequalities in England, Scotland and Wales: stakeholders ´ accounts and policy compared. Public Health. 2009;123 (1):24-8. http://doi.org/bg844z.

35.Furler J, Harris E, Harris M, Naccarella L, Young D, Snowdon T. Health inequalities, physician citizens and professional medical associations: an Australian case study. BMC Med. 2007;5:23. http://doi.org/fh2trs.

36.Oosterhoff P, Anh NT, Yen PN, Wright P, Hardon A. HIV-positive mothers in Viet Nam: using their status to build support groups and access essential services. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;16(32):162-70. http://doi.org/dt4k8d.

37.Campbell J, Buchan J, Cometto G, David B, Dussault G, Fogstad H, et al. Human resources for health and universal health coverage: fostering equity and effective coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91: 853-63. http://doi.org/bptc.

38.Mumtaz Z, Salway S, Shanner L, Bhatti A, Laing L. Maternal deaths in Pakistan: intersec tion of gender, caste and social exclusion. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2011;11(Suppl 2):S4. http://doi.org/dxpm5d.

39.El Arifeen S, Hill K, Ahsan KZ, Jamil K, Nahar Q, Streatfield PK. Maternal mortality in Bangladesh: a Countdown to 2015 country case study. Lancet. 2014;384(9951):1366-74. http:// doi.org/f2vkct.

40.Crawley J, Kane D, Atkinson-Plato L, Hamilton M, Dobson K, Watson J. Needs of the hidden homeless -No longer hidden: a pilot study. Public Health. 2013;127(7):674-80. http://doi. org/bptd.

41.Zoidze A, Rukhazde N, Chkhatarashvili K, Gotsadze G. Promoting universal financial protection: health insurance for the poor in Georgia - a case study. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:45. http://doi.org/bptj.

42.Mumtaz Z, Levay A , Bhatti A, Salway S. Signalling, status and inequities in maternal healthcare use in Punjab, Pakistan. Soc Sci Med. 2013;94:98- 105. http://doi.org/bptk.

43.Harper-Bulman K; McCourt C. Somali refugee women’s experiences of maternity care in west London: a case study. Critical Public Health. 2002;12(4):365-80. http://doi.org/d47mcp.

44.Feng Y, Xiong X, Xue Q, Yao L, Luo F, Xiang L. The impact of medical insurance policies on the hospitalization services utilization of people with schizophrenia: A case study in Changsha, China. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29(3):793-8. http:// doi.org/bptm.

45.van Beurden E, Lefevbre C, James R. Transferring community-based interventions to new settings: a case study in heart health cholesterol testing from urban USA to rural Australia. Health Promotion International. 1991;6(3):181-90. http:// doi.org/dtnqzv.

46.Türkkan A, Aytekin H. Socioeconomic and health inequality in two regions of Turkey. J Community Health. 2009;34(4):346-52. http://doi. org/dmfk9w.

47.de Andrade LO, Pellegrini Filho A, Solar O, Rígoli F, de Salazar LM, Serrate PC, et al. Social determinants of health, universal health coverage, and sustainable development: case studies from Latin American countries. Universal health coverage in Latin America. Lancet. 2015;385(9975):1343-51. http://doi.org/ f265fw.

48.De Brouwere V, Richard F, Witter S. Access to maternal and perinatal health services: lessons from successful and less successful examples of improving access to safe delivery and care of the newborn. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(8):901- 9. http://doi.org/djfwf7.

49.Padhi BK, Padhy PK, Jain VK. Impact of indoor air pollution on maternal and child health: A case study in India. Epidemiology. 2011;22(1):s118. http://doi.org/d9dh8c.

50.Stolt R, Winblad U. Mechanisms behind privatization: a case study of private growth in Swedish elderly care. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(5):903-11. http://doi.org/btvrqs.

51.Maberley D, Hollands H, Chang A, Adilman S, Chakraborti B, Kliever G. The prevalence of low vision and blindness in a Canadian inner city. Eye (Lond). 2007;21(4):528-33. http://doi. org/d76brr.

52.Carmichael A, Williams HE. Use of health care services for an infant population in a poor socio- economic status, multi-ethnic municipality in Melbourne. Aust. Paediatr. J. 1983;19(4):225-9. http://doi.org/d2mrr4.

53.Bernal R, Cárdenas M. Race and Ethnic Inequality in Health and Health Care in Colombia. Bogotá: Fedesarrollo; 2005 [Cited 2016 Aug 24]. Available from: http://goo.gl/EYf1jC.

54.Teerawichitchainan B, Phillips JF. Ethnic differentials in parental health seeking for childhood illness in Vietnam. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(5):1118-30. http://doi.org/bch8gf.

55.Macleod MR, Andrews PJ. Effect of deprivation and gender on the incidence and management of acute brain disorders. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(12):1729-34. http://doi.org/cvrf9d.

56.Eslava-Schmalbach JH, Rincón CJ, Guarnizo- Herreño CC. ‘Inequidad’ de la expectativa de vida al nacer por sexo y ‘departamentos’ de Colombia. Biomedica. 2013;33(3):383-92. http://doi.org/bptn.

57.Sandoval-Vargas YG, Eslava-Schmalbach JH. Inequidades en mortalidad materna por departamentos en Colombia para los años (2000- 2001), (2005-2006) y (2008-2009). Rev Salud Publica (Bogota). 2013 [cited 2016 Aug 24];15(4):529-41. Available from: http://goo.gl/ o9UogY.

58.Pinilla A, Cano N, Granados C, Páez-Canro C, Eslava-Schmalbach J. Inequalities in prescription of hydrochlorothiazide for diabetic hypertensive patients in Colombia. Rev Salud Publica (Bogota). 2011 [cited 2016 Aug 24];13(1):27- 40. Available from: http://goo.gl/tmWiXg.

59.Herrera Gómez PJ, Medina PA. Los problemas de la analgesia obstétrica. Rev. colomb. anestesiol. 2014;42(1):37-9. http://doi.org/f2n8tk.

60.Duarte Ortiz G, Navarro-Vargas JR, Eslava- Schmalbach J. Inequidad en el sistema de salud: el panorama de la analgesia obstétrica. Rev colomb. anestesiol. 2013;41(03):215-7. http:// doi.org/f2hmz5.

ANEX 1

LILACS: Salud AND equidad AND inequidad EMBASE:

|

Descriptor number |

Keyword |

|

1 |

‘Social’ |

|

2 |

Social:ab,ti |

|

3 |

Marginalization |

|

4 |

Marginalization:ab,ti |

|

5 |

Inequality |

|

6 |

Inequality.ab,ti |

|

7 |

Inequity |

|

8 |

Inequity:ab,ti |

|

9 |

Health/exp |

|

10 |

Health:ab,ti |

|

11 |

Primary health care / exp |

|

12 |

(Primary health care):ab,ti |

|

13 |

Public policy / exp |

|

14 |

(public policy).ab,ti |

|

15 |

Coverage |

|

16 |

Coverage: ab,ti |

|

17 |

Exclusion |

|

18 |

Exclusion: ab,ti |

|

19 |

Service |

|

20 |

Service.ab,ti |

|

21 |

Justice/exp |

|

22 |

Justice:ab,ti |

|

23 |

Access |

|

24 |

Access:ab,ti |

|

25 |

Difference |

|

26 |

Difference:ab,ti |

|

27 |

Disability/exp |

|

28 |

Disability:ab,ti |

|

29 |

Quality of life/exp |

|

30 |

(quality of life):ab,ti |

|

31 |

Case series /exp |

|

32 |

(case series):ab,ti |

|

33 |

Case:ab,ti |

|

34 |

Series:ab,ti |

|

35 |

Case report /exp |

|

36 |

(case report):ab,ti |

|

37 |

Report.ab,ti |

|

38 |

Or/#1 - #10 |

|

39 |

Or/#11-#22 |

|

40 |

Or/#23 - #28 |

|

41 |

#29 OR #30 |

|

42 |

Or/ #31 - #37 |

|

43 |

AND / #38 - #42 |

Medline

|

Descriptor number |

Keyword |

|

1 |

Exp /health |

|

2 |

Marginalization.tw |

|

3 |

Inequit$.tw |

|

4 |

Inequalit$.tw |

|

5 |

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 |

|

6 |

Coverage.tw |

|

7 |

Exclusión.tw |

|

8 |

Service.tw |

|

9 |

Justice.tw |

|

10 |

Public policy.tw |

|

11 |

Primary health care.tw |

|

12 |

6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 |

|

13 |

Access.tw |

|

14 |

Difference.tw |

|

15 |

13 or 14 |

|

16 |

Disabilit$.tw |

|

17 |

Quality of life.tw |

|

18 |

16 or 17 |

|

19 |

Case report.tw |

|

20 |

(cas$ AND series).tw |

|

21 |

19 or 20 |

|

22 |

5 and 12 and 18 and 21 |

|

23 |

12 and 15 and 18 |

REVISIÓN SISTEMÁTICA: UN ENFOQUE PARA IDENTIFICAR DESIGUALDADES EN SALUD A TRAVÉS DE ESTUDIOS DE CASOS

Palabras clave: Equidad en salud; Disparidades en la atención en salud; Reportes de caso.

Keywords: Health Equity; Healthcare Disparities; Case reports.

Rafael Adrián Gómez Suárez • Angélica Milena Tarquino Bojacá

Anderson Aparicio Mejía • María Carolina Nossa Ramos

Camilo Andrés Alarcón González • Lizeth Andrea Prieto Puerto

Adriana C. Villada Ramírez • Juan Pablo Alzate

Médico interno – Universidad Nacional de Colombia

– Sede Bogotá – Semillero de Investigación del Grupo de Equidad en Salud

Hospital Universitario Nacional de Colombia

Bogotá, D.C. – Colombia

Javier Eslava-Schmalbach

Anestesiólogo, MSc en Epidemiología Clínica,

PhD en Salud Pública

Centro de Desarrollo Tecnológico,

Sociedad Colombiana de

Anestesiología y Reanimación

– Sede Bogotá – Bogotá, D.C. – Colombia

Corresponding author:

Javier Eslava–Schmalbach

Hospital Universitario Nacional de Colombia,

Universidad Nacional de Colombia

– Sede Bogotá –

Bogotá, D.C. – Colombia.

Email: jheslavas@unal.edu.co

RESUMEN:

Introducción: las desigualdades en salud, entre otros factores, reflejan el nivel de bienestar de una población. Para realizar intervenciones dirigidas a eliminar o prevenir estas desigualdades es necesario comprender su origen.

Objetivo: realizar una revisión sistemática para identificar estudios de casos en los que se reportan desigualdades en salud en todo el mundo.

Metodología: en este estudio se incluyeron reportes de caso, estudios de casos y series de casos, escritos en inglés, español y portugués, en los que se informan desigualdades en salud. Se utilizaron bases de datos como Medline y EMBASE, así como fuentes de literatura gris como LILACS, OpenGrey, Google, entre otras.

Resultados: la búsqueda inicial arrojó 1272 artículos; de los cuales se seleccionaron 139 por su título; luego, basándose en su resumen, se escogieron 28 para realizar una lectura completa. Finalmente se incluyeron 23 artículos. En términos de inequidad en salud, la diferencia de género fue el factor más frecuente (23.2%), seguido por condición socioeconómica (20%), pertenecer a una población migrante (13.3%), origen étnico (13.3%), edad (10%), origen geográfico (3.3%) y otros (16,6%).

Discusión: este enfoque, que se basa en la revisión de reportes de caso para estudiar las desigualdades en salud, contrasta con la mayoría de estudios que se han realizado al respecto. En esta investigación se propone analizar las desigualdades en salud que son específicas a poblaciones que viven dentro de comunidades en un área geográfica en particular y que no tienen acceso a servicios óptimos de salud.

Palabras clave: equidad en salud; Disparidades en Atención de Salud; Reportes de caso.

INTRODUCCIÓN

Las inequidades en salud son aquellas diferencias “evitables e injustas” que surgen cuando hay diferencias sistemáticas a nivel social, económico, demográfico o geográficos en uno o más aspectos de la salud en diferentes poblaciones o grupos de población (1). Sin embargo, otros autores definen la equidad en salud sobre la base de que “la asignación de recursos y el acceso [a la salud] son determinados por las necesidades de salud” (2).

Las desigualdades en salud, entre otras cosas, evidencian el nivel de bienestar de las personas y los recursos a los que tienen acceso (3), lo que quiere decir que entre más grande la desigualdad en salud en un grupo, mayor la probabilidad de tener un bajo nivel de bienestar, altas tasas de morbilidad y mortalidad, y de que haya una distribución de recursos inequitativa o insuficiente (4,5). Este tema ha sido objeto de estudio tanto en América Latina (6,7,8), como en todo el mundo (9,10,11), con el fin de modificar las políticas públicas en relación con las intervenciones en los determinantes de la salud, así como de proponer la “Salud en Todas las Políticas” (12).

Aunque en el siglo XX las tasas de mortalidad se redujeron notablemente en todos los países (especialmente los del primer mundo), las desigualdades en mortalidad por clase social entre países y, a su vez, entre clases sociales han aumentado (13). Incluso en países con altos ingresos es posible observar inequidades dependiendo de la ubicación geográfica (14). La sociedad cambia, las enfermedades varían y los servicios de salud crecen y mejoran, pero el índice de injusticia y de diferencias en salud que son evitables sigue aumentando (15). Con frecuencia, la llamada “ley de cuidados inversos” entra en juego, es decir, a menudo la calidad de la atención médica es inversamente proporcional a las necesidades de la población (16).

Los reportes de caso son una valiosa herramienta para describir, evaluar y comparar ciertas poblaciones. Igualmente, este tipo de artículos ha sido y continúa siendo una fuente abundante y constante de aprendizaje, de problemas y de preguntas de investigación, lo que los convierte en el “primer nivel de evidencia” para investigaciones futuras e intervenciones a realizarse a mayor escala (17).

Una definición conceptual de las desigualdades en salud es insuficiente cuando se trata de entender los problemas en salud derivados de estas. Por lo tanto, se necesita una mayor comprensión sobre cómo surgen y el tipo de eventos que pueden llevar a su aparición (18, 19). Además, estas desigualdades pueden presentarse desde una perspectiva del acceso a los servicios de salud: desigualdades horizontales —cuando una población con necesidades específicas no tiene acceso a los mismos recursos— o, por el contrario, desigualdades verticales —cuando se presentan entre quienes, debido a que tienen mayor necesidad, deben, en teoría, recibir más recursos, algo que nunca sucede— (20).

Hay muchos índices que miden las desigualdades, por ejemplo, el coeficiente de Gini, que mide hasta qué punto una economía es incompatible con una distribución perfectamente equitativa. Otro índice importante es el Índice de Desigualdad de Género, el cual refleja la desigualdad entre géneros en tres dimensiones: salud reproductiva, empoderamiento y participación en el mercado laboral. Por ejemplo, el resultado obtenido en el Índice de Desigualdad de Género para el mundo fue de 0.451 en 2014, mientras que en Colombia fue de 0.460 (21). Este índice muestra que, en comparación con el resto del mundo, Colombia presenta mayor desigualdad entre géneros. Por su parte, el índice de inequidad en salud fue creado con el objetivo de medir este tipo de desigualdades con base en los Objetivos de Desarrollo del Milenio, establecidos en septiembre del año 2000 (22).

A pesar de que el estudio de las desigualdades e inequidades en salud se ha centrado en los marcos conceptuales, el análisis de índices e indicadores es una forma de medirlas, así como de entender el papel que juegan los determinantes de la salud. Por otra parte, no se sabe con certeza cuánta información sobre desigualdades en salud existe en estudios de casos o reportes de caso. Por lo tanto, el objetivo de este estudio es realizar una revisión sistemática que identifique aquellos estudios de casos que reporten desigualdades en salud en todo el mundo.

METODOLOGÍA

Criterios de inclusión y de exclusión

Se realizó una revisión sistemática cualitativa, presentando la evidencia de forma descriptiva, de conformidad con los lineamientos establecidos por PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses) (23). Igualmente, como unidad de estudio se consideró a aquellos individuos en una situación de desigualdad en términos de salud. De acuerdo a lo anterior, se incluyeron reportes de caso, estudios de casos y series de casos en los que se informan desigualdades o inequidades en salud.

Ente los artículos que fueron excluidos de este estudio se encuentran aquellos que no eran reportes de caso, series de casos o estudios de casos; los que abordaban desigualdades en salud en poblaciones no-humanas; artículos escritos en un idioma diferente al inglés, español o portugués; estudios que no tenían relación alguna con el objetivo de esta revisión, y artículos que presentaban información incompleta (título o resumen).

Fuentes de información

Se utilizaron fuentes de búsqueda como OVID y EMBASE; otras fuentes como Google Académico, LILACS y OpenGrey fueron usadas para encontrar artículos académicos. Por su parte, las búsquedas fueron realizadas empleando una serie de términos bajo el modelo PICOT para la formulación preguntas de investigación. Los términos fueron salud, inequidad, desigualdad, marginación, atención primaria de salud, política pública, justicia, cobertura, exclusión, servicio, acceso, diferencia, discapacidad y calidad de vida, los cuales se usaron, en la búsqueda, en relación con los siguientes factores: población, intervención, resultados y tratamiento (Anexo 1).

Además, se usaron operadores booleanos en conjunto con términos controlados (Emtree, MeSH) y no controlados. Igualmente, se utilizaron truncadores para incluir los sinónimos, los acrónimos y las variaciones ortográficas de cada término.

Con respecto a las bases de datos se debe decir que el único método de acceso a la base de datos Medline fue el buscador OVID, y que las búsquedas realizadas en EMBASE solo se limitaron a los estudios incluidos en esta base de datos. Por último, la búsqueda de literatura gris se llevó a cabo usando términos en español a través de LILACS, OpenGrey y Google.

Estrategias de búsqueda

Las búsquedas en bases de datos electrónicas y fuentes de literatura gris se realizaron en julio de 2015; el proceso se llevó a cabo de la siguiente manera:

• Dos investigadores (CAA y AAM) buscaron literatura gris.

• Un investigador (GAR) buscó en Medline.

• Tres investigadores (AMT, MCN, LAP) buscaron en EMBASE.

Los artículos derivados de la búsqueda inicial en Google se obtuvieron mediante la combinación al azar de términos de búsqueda respetando siempre la pregunta PICOT. No se aplicaron filtros.

Selección de los estudios

Cada investigador, de forma independiente y teniendo en cuenta los criterios de inclusión y exclusión, hizo un proceso de selección de los artículos consultados en la fuente de búsqueda que le fue asignada, dicho proceso se basó en el título y resumen de cada artículo. Se creó una tabla para enumerar los artículos seleccionados, eliminando así títulos repetidos. Luego, se formaron parejas aleatorias de investigadores para revisar los artículos se leccionados mediante la lectura completa de los mismos y teniendo en cuenta los criterios de inclusión y exclusión.

Los desacuerdos se resolvieron a través de una decisión por consenso, mientras que en los casos en los que no hubo consenso, un tercer revisor decidió si el artículo debía o no incluirse.

Recopilación y análisis de datos

Se creó una tabla en Excel con un formato establecido con el fin de mostrar las principales características de cada estudio, la cual fue completada, de forma independiente, por cada pareja de investigadores. Una vez terminadas, se realizó una comparación entre las tablas para resolver desacuerdos y unificar los resultados mediante la participación de un tercer investigador (ACV). Estos desacuerdos se resolvieron mediante consenso.

Por su parte, el sesgo se midió en relación con la selección, los procedimientos realizados durante la investigación y los conflictos relacionados con la financiación o las fuentes de recursos. Así, el sesgo se clasificó en las siguientes categorías: alto riesgo, bajo riesgo y riesgo incierto. La categoría alto riesgo se escogió cuando un artículo presentaba problemas respecto a brindar las mismas garantías entre los diferentes casos estudiados. Por su parte, la categoría bajo riesgo se asignó a aquellos artículos que informaban su financiación de forma clara y cuya metodología no favorecía el resultado de un reporte de caso sobre el de otro. Finalmente, bajo la categoría riesgo incierto se incluyeron aquellos estudios en los que no se informaban la metodología, ni la financiación y por tanto las garantías en relación con su elaboración no eran claras.

Calidad de la revisión sistemática

Para medir esta revisión sistemática se utilizaron los criterios AMSTAR (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews) (24), donde una puntuación de 7 o mayor en la evaluación de la calidad de las revisiones sistemáticas significa que es de buena calidad. Estos criterios arrojaron una puntuación favorable, lo que demuestra que esta revisión es un estudio válido. En términos generales, se debe señalar que la pregunta de investigación y los criterios de inclusión fueron establecidos antes de iniciar la revisión. Además, dos personas independientes participaron en la selección de los estudios y la extracción de los datos, mientras que los desacuerdos se resolvieron después de realizar dicha selección.

RESULTADOS

En total, se seleccionaron 23 artículos que se ajustaron a los criterios de inclusión y que no se vieron afectados por ningún criterio de exclusión. A continuación se presenta un diagrama de flujo (Figura 1) en el que se describe detalladamente el proceso de selección de los estudios en las diferentes bases de datos.

Fig 1. Diagrama de flujo de los estudios incluidos en la revisión.

Fuente: Elaboración propia con base en los datos obtenidos durante la realización del estudio.

Se encontraron 1272 artículos en la búsqueda inicial. Los criterios de inclusión y exclusión descritos anteriormente se aplicaron a estos 1272 artículos. Luego, se seleccionaron 139 artículos por su título y, de estos, 28, a partir de su resumen, para realizar una lectura total. Por último, la revisión incluyó 23 de los 28 artículos seleccionados.

Descripción de los estudios

En esta revisión fue posible demostrar diferentes tipos de desigualdades en salud tanto en países desarrollados, como en países en vía de desarrollo, tal como se puede observar en la Tabla 1.

Como se ve en la Tabla 1, las siguientes desigualdades en salud se destacan: demoras en la prestación de la atención solicitada (33), dificultades para acceder a la atención primaria de salud (37) y dificultades para acceder a la atención con el nivel de complejidad necesario para hacer frente a situaciones especiales (42). Igualmente, se observaron diferencias en la prestación de servicios de salud a poblaciones vulnerables en los sectores públicos y privados (25). Por otra parte, se encontraron diferentes tipos de enfoques de políticas públicas en relación con las desigualdades en salud, lo que muestra una ligera reducción de las desigualdades en las áreas en las que hay mayor cobertura en salud y mayor acceso a atención primaria de calidad (27,34). En general, se demostró la continuidad de las inequidades entre poblaciones vulnerables.

Tabla 1. Características principales de los estudios incluidos.

|

Autores y año de publicación |

Título |

Países estudiados |

Tipo de estudio |

Población en condición de desigualdad |

Desigualdad informada |

Evaluación cualitativa del sesgo |

|

Chatty D, Mansour N, Yassin N. 2013 (25) |

Bedouin in Lebanon: Social discrimination, political exclusion, and compromised health care |

Líbano |

Estudio de casos |

Población nacionalizada |

Desigualdad en el acceso a los sistemas de salud por parte de población no nacionalizada |

Bajo riesgo de sesgo |

|

Abadia CE, Oviedo DG. 2009 (26) |

Bureaucratic Itineraries in Colombia. A theoretical and methodological tool to assess managed-care health care systems |

Colombia |

Estudio de casos |

Población con diferencias socioeconómicas |

Diferencias en la atención de salud según el plan de seguro médico |

Riesgo incierto de sesgo |

|

Brimacombe MB, Heller DS, Zamudio S. 2007 (27) |

Comparison of fetal demise case series drawn from socioeconomically distinct counties in New Jersey |

EE.UU. |

Serie de casos |

Mujeres gestantes |

Desigualdades socioeconómicas entre dos condados y sus repercusiones en el número de nacimientos de niños muertos |

Alto riesgo de sesgo |

|

Yang JS. 2008 (28) |

Contextualizing immigrant access to health resources |

EE.UU. |

Estudio de casos |

Población inmigrante |

Desigualdad en el acceso a los sistemas de salud por parte de la población china inmigrante en San Francisco, EE.UU. |

Riesgo incierto de sesgo |

|

Sypek S, Clugston G, Phillips C. 2008 (29) |

Critical health infrastructure for refugee resettlement in rural Australia: case study of four rural towns |

Australia |

Estudio de casos |

Población inmigrante |

Acceso a los servicios de salud entre la población refugiada ubicada en zonas rurales de Australia |

Bajo riesgo de sesgo |

|

Karam- Calderón MA, Bustamante- Montes P, Campuzano- González M, Camarena Pliego A. 2007 (30) |

Social aspects of maternal mortality. A case study in the State of Mexico, Mexico |

México |

Estudio de casos |

Mujeres gestantes |

Desigualdades socioeconómicas que tienen efectos en la mortalidad materna |

Riesgo incierto de sesgo |

|

Bogenschutz M. 2014 (31) |

“We Find a Way”: Challenges and facilitators for health care access among immigrants and refugees with intellectual and developmental disabilities |

EE.UU. |

Estudio de casos |

Población emigrante con algún tipo de discapacidad |

Retos a los que se enfrentan los inmigrantes con discapacidad para acceder a los servicios de salud |

Riesgo incierto de sesgo |

|

Källander K, Hildenwall H, Waiswa P, Galwango E, Peterson S, Pariyo G. 2008 (32) |

Delayed care seeking for fatal pneumonia in children aged under five years in Uganda: a caseseries study |

Uganda |

Serie de casos |

Niños con edades entre 1 y 59 meses |

Retrasos en el acceso a los servicios de salud que tienen como consecuencia mortalidad infantil por neumonía |

Bajo riesgo de sesgo |

|

Hacker J, Stanistreet D. 2004 (33) |

Equity in waiting times for two surgical specialties: a case study at a hospital in the North West of England |

Inglaterra, |

Estudio de casos |

Mujeres, adultos mayores y personas de bajo nivel socioeconómico |

Las mujeres, los adultos mayores y las personas de bajo nivel socioeconómico presentan mayores tiempos de espera en cuanto a la realización de procedimientos en áreas como ortopedia y oftalmología. No se proporcionan resultados concluyentes en relación con el origen étnico |

Bajo riesgo de sesgo |

|

Harrington BE, Smith KE, Hunter DJ, Marks L, Blackman TJ, McKee L et al. 2009 (34) |

Health inequalities in England, Scotland and Wales: stakeholders´ accounts and policy compared |

Inglaterra, Gales y Escocia |

Serie de casos |

Población general |

A partir de 2003- 2005, los tres países debieron tener en cuenta el estilo de vida y la responsabilidad individual a la hora de asignar la prioridad clínica en cada caso. El acceso a los servicios de salud fue un factor importante en lo que respecta a las desigualdades en salud |

Riesgo incierto de sesgo |

|

Furler J, Harris E, Harris M, Naccarella L, Young D, Snowdon T. 2007 (35) |

Health inequalities, physician citizens and professional medical associations: an Australian case study |

Australia |

Estudio de casos |

Estudiantes de medicina y médicos |

Los resultados indican que incluso en las áreas de compromiso profesional hubo una tendencia a superar los obstáculos financieros para mejorar el acceso a la atención de salud |

Riesgo incierto de sesgo |

|

Oosterhoff P, Anh NT, Yen PN, Wright P, Hardon A. 2008 (36) |

HIV-positive mothers in Viet Nam: using their status to build support groups and access essential services. |

Vietnam |

Estudio de casos |

Madres seropositivas y sus hijos |

El acceso oportuno a la atención de salud parte de la madre y su hijo |

Riesgo incierto de sesgo |

|

Campbell J, Buchan J, Cometto G, David B, Dussault G, Fogstad H et al. 2013 (37) |

Human resources for health and universal health coverage: fostering equity and effective coverage |

Brasil, Ghana, México y Tailandia |

Estudio de casos |

Población general |

El estudio demuestra que mediante un aumento del personal de salud, los índices de salud de las madres y de los recién nacidos mejoraron considerablemente |

Riesgo incierto de sesgo |

|

Mumtaz Z, Salway S, Shanner L, Bhatti A, Laing L. 2011 (38) |

Maternal deaths in Pakistan: intersection of gender, caste and social exclusion |

Pakistán |

Estudio de casos |

Mujeres y niños |

Se evalúa la desigualdad respecto al acceso al combustible necesario para llevar a cabo los quehaceres domésticos es una zona rural. Igualmente, se asocia la exposición a la contaminación del aire con la salud de las madres y la presencia de bajo peso en los recién nacidos |

Bajo riesgo de sesgo |

|

El Arifeen S, Hill K, Ahsan KZ, Jamil K, Nahar Q, Streatfield PK. 2014 (39) |

Maternal mortality in Bangladesh: a Countdown to 2015 country case study |

Bangladesh |

Serie de casos |

Dos mujeres gestantes |

Dos mujeres gestantes de una casta de bajos ingresos no recibieron la atención médica adecuada para las complicaciones que presentaron en el parto, lo que a su vez causó su muerte |

Riesgo incierto de sesgo |

|

Crawley J, Kane D, Atkinson-Plato L, Hamilton M, Dobson K, Watson J. 2013 (40) |

Needs of the hidden homeless- No longer hidden: a pilot study |

Canadá |

Estudio de casos |

Personas que sufren una desigualdad socioeconómica (drogadictos) |

Acceso desigual a los servicios de salud debido al estigma que representa tener una adicción a sustancias psicoactivas. |

No es claro en el artículo |

|

Zoidze A, Rukhazde N, Chkhatarashvili K, Gotsadze G. 2013 (41) |

Promoting universal financial protection: health insurance for the poor in Georgia - a case study |

Georgia |

Estudio de casos |

Personas con desigualdades socioeconómicas |

Los gastos totales y los costos de hospitalización de las personas y aquellos que se derivan de la atención ambulatoria cuando se pasa de un seguro médico privado a uno “para pobres” |

No es claro en el artículo |

|

Mumtaz Z, Levay A , Bhatti A, Salway S. 2013 (42) |

Signalling, status and inequities in maternal healthcare use in Punjab, Pakistan |

Pakistán |

Estudio de casos |

Mujeres con diferencias socioeconómicas |

Desigualdades en la atención de salud de mujeres embarazadas que residen en un área rural donde se presenta una fuerte jerarquía |

No es claro en el artículo |

|

Harper-Bulman K; McCourt C. 2002 (43) |

Somali refugee women’s experiences of maternity care in west London: a case study |

Londres occidental |

Estudio de casos |

Mujeres discriminadas por su origen étnico y por su condición migrante |

Acceso diferencial a los servicios de salud en una minoría étnica de mujeres gestantes somalíes en Londres |

Alto riesgo de sesgo |

|

Y, Xiong X, 1.53 Xue Q, Yao L, Luo F, Xiang L. 2013 (44) |

The impact of medical insurance policies on the hospitalization services utilization of people with schizophrenia: A case study in Changsha, China |

China |

Estudio de casos |

Población urbana |

El estudio reporta los cambios en la atención en salud que pueden darse en una población que recibe atención médica por parte de diferentes compañías en China |

Bajo riesgo de sesgo |

|

E, Lefevbre C, James R. 1991 (45) |

Transferring community-based interventions to new settings: a case study in heart health cholesterol testing from urban USA to rural Australia |

Pawtucket, EE.UU. / Costa Norte de Australia |

Estudio de casos |

Pacientes crónicos procedentes de un área geográfica en particular |

Se reportan desigualdades en la atención médica de enfermedades crónicas entre poblaciones rurales y urbanas |

Alto riesgo de sesgo |

|

Türkkan A, Aytekin H. 2009 (46) |

Socioeconomic and health inequality in two regions of Turkey |

Bursa, Turquía |

Estudio de casos |

Personas con desigualdades socioeconómicas |

El estudio señala que la salud de quienes viven en las zonas de menor nivel socioeconómico de Bursa es peor que la de aquellos que residen en las zonas más prósperas |

Bajo riesgo de sesgo |

|

de Andrade LO, Pellegrini Filho A, Solar O, Rígoli F, de Salazar LM, Serrate PC et al. 2015 (47) |

Social determinants of health, universal health coverage, and sustainable development: case studies from Latin American countries. Universal health coverage in Latin America |

Brasil, Chile, Colombia y Cuba |

Estudio de casos |

Población general |

En el artículo se presentan diferencias entre estos países en cuanto a la implementación de políticas públicas para el control de enfermedades contagiosas, la mejora en términos de experiencia, y los resultados obtenidos a partir del desarrollo de la primera infancia y las transferencias monetarias condicionales destinadas a garantizar los derechos de salud, la educación y la reducción de la pobreza. |

Bajo riesgo de sesgo |

Fuente: Elaboración propia con base en los datos obtenidos durante la realización del estudio.

En los países desarrollados, los casos de desigualdades se relacionaron principalmente con la falta de acceso a la atención de salud por parte de poblaciones migrantes (28,29), fenómeno que se da por las limitaciones relativas al idioma o porque los administradores o proveedores de atención de salud excluyen a

esta población por su origen étnico o su condición de inmigrantes ilegales con un nivel socioeconómico bajo (43). Por su parte, entre la población no inmigrante se encontró que las desigualdades en salud fueron causadas por aspectos como la diferencia entre los ingresos económicos percibidos, el tipo de seguro médico, (41) y políticas públicas que no se adaptan a las diferencias sociales entre los individuos de una población (45). Además, también se evidenciaron desigualdades en salud en poblaciones con algún tipo de discapacidad —física y mental— o dependencia de sustancias psicoactivas (40).

En los países en desarrollo, se reportaron, en particular, desigualdades relacionadas con el nivel socioeconómico (26,45) y un menor acceso a los servicios de salud por parte de poblaciones ubicadas en zonas poco habitadas y alejadas de las grandes ciudades. Estos factores fueron asociados con condicionantes culturales que aumentan la desigualdad, en especial en términos de acceso a servicios de calidad para mujeres y niños. Asimismo, el aumento de la mortalidad por enfermedades tratables y prevenibles es algo muy preocupante (31,36,37). Varios artículos reportaron las diferencias en el acceso oportuno al sistema de salud entre mujeres embarazadas como un importante indicador de desigualdad (30,42), mientras que otros señalaron cambios favorables en la mortalidad materna a través el estudio de las desigualdades en salud como un factor determinante (37,39).

La Tabla 2 muestra los porcentajes de las poblaciones que han experimentado desigualdades en salud de acuerdo al número de artículos incluidos en esta revisión. En la Tabla 3 se presentan los criterios usados para excluir artículos en la última ronda de exclusión.

Tabla 2. Poblaciones que sufren desigualdades en salud.

|

Población en condición de desigualdad |

Número de artículos en los que la población fue objeto de una desigualdad |

Porcentaje |

|

Género |

7 |

23.20% |

|

Nivel socioeconómico |

6 |

20% |

|

Otros |

5 |

16.60% |

|

Grupo étnico |

4 |

13.30% |

|

Población migrante |

4 |

13.30% |

|

Edad |

3 |

10% |

|

Procedencia geográfica |

1 |

3.30% |

|

Nivel educativo |

0 |

0% |

Fuente: Elaboración propia con base en los datos obtenidos durante la realización del estudio.

Nota: El mismo artículo se pudo haber incluido en más de una condición de desigualdad, pues las categorías de desigualdad no son mutuamente excluyentes.

Tabla 3. Estudios excluidos.

|

Referencia corta |

Motivo de exclusión |

|

De Brouwere V, Richard F, Witter S. 2010 (48) |