Vocational Choice: A Narrative Identity Approach Conceived from Cultural Psychology

La Elección Vocacional: Una Aproximación Desde la Identidad Narrativa Concebida a Partir de la Psicología Cultural

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/rcp.v32n2.96358Keywords:

cultural psychology, narrative identity, possible vocational world, vocation, vocational identity, vocational psychology (en)identidad narrativa, identidad vocacional, psicología cultural, mundo vocacional posible, psicología vocacional, vocación (es)

Vocation has been studied from perspectives such as trait-factor, differential psychology, and psychometrics. These perspectives have assumed it to be the precursor of a unique and definitive career choice, resulting from matching personal characteristics with the requirements of a job. Vocation has also been conceptualized as the product of evolutionary stages, dependent on maturational processes. However, the changing conditions of the contemporary world of work make it necessary to reconsider vocationality from a dynamic perspective that transcends the exclusively psychometric view. This article proposes an alternative approach to vocation, based on the processes of identity construction propose by cultural psychology. Thus, vocation is assumed as a process of a narrative nature, in constant formation, based on the symbolic resources with which people interact. Vocationality emerges as a historical, situated, and distributed phenomenon, marked by occupational and educational experiences, as well as by interactive experiences with significant others.

La vocación ha sido estudiada desde perspectivas como las de rasgo-factor, la psicología diferencial y la psicometría. Estas perspectivas la han asumido como el precursor de una elección de carrera única y definitiva, resultante de alinear características personales con los requerimientos propios de un puesto de trabajo; o como el producto de etapas evolutivas, dependientes de procesos madurativos. No obstante, las condiciones cambiantes del mundo laboral contemporáneo obligan a reconsiderar la vocacionalidad desde una perspectiva dinámica que transcienda la mirada exclusivamente psicométrica. El presente artículo propone una aproximación alternativa de la vocación, sustentada en los procesos de construcción identitaria planteados desde la psicología cultural. Así, la vocación se asume como un proceso de naturaleza narrativa, en constante formación, fundado en los recursos simbólicos con los que interactúan las personas. La vocacionalidad emerge como un fenómeno histórico, situado y distribuido, marcado tanto por experiencias ocupacionales y educativas, como por vivencias interactivas con otros significativos.

Recibido: 3 de junio de 2022; Aceptado: 25 de enero de 2023

Abstract

Vocation has been studied from perspectives such as trait-factor, differential psychology, and psychometrics. These perspectives have assumed it to be the precursor of a unique and definitive career choice, resulting from matching personal characteristics with the requirements of a job. Vocation has also been conceptualized as the product of evolutionary stages, dependent on maturational processes. However, the changing conditions of the contemporary world of work make it necessary to reconsider vocationality from a dynamic perspective that transcends the exclusively psychometric view. This article proposes an alternative approach to vocation, based on the processes of identity construction proposed by cultural psychology. Thus, vocation is assumed as a process of a narrative nature, in constant formation, based on the symbolic resources with which people interact. Vocationality emerges as a historical, situated, and distributed phenomenon, marked by occupational and educational experiences, as well as by interactive experiences with significant others.

Keywords

cultural psychology, narrative identity, possible vocational world, vocation, vocational identity, vocational psychology.Resumen

La vocación ha sido estudiada desde perspectivas como las de rasgo-factor, la psicología diferencial y la psicometría. Estas perspectivas la han asumido como el precursor de una elección de carrera única y definitiva, resultante de alinear características personales con los requerimientos propios de un puesto de trabajo; o como el producto de etapas evolutivas, dependientes de procesos madurativos. No obstante, las condiciones cambiantes del mundo laboral contemporáneo obligan a reconsiderar la vocacionalidad desde una perspectiva dinámica que transcienda la mirada exclusivamente psicométrica. El presente artículo propone una aproximación alternativa de la vocación, sustentada en los procesos de construcción identitaria planteados desde la psicología cultural. Así, la vocación se asume como un proceso de naturaleza narrativa, en constante formación, fundado en los recursos simbólicos con los que interactúan las personas. La vocacionalidad emerge como un fenómeno histórico, situado y distribuido, marcado tanto por experiencias ocupacionales y educativas, como por vivencias interactivas con otros significativos.

Palabras clave

identidad narrativa, identidad vocacional, psicología cultural, mundo vocacional posible, psicología vocacional, vocación.THIS ARTICLE offers an approach to the vocational phenomenon from cultural psychology. From this perspective, the vocational phenomenon is understood as an identity process of a narrative nature in continuous progression supported for its operation on the symbolic resources available in the socio-cultural contexts within which people interact. Based on these resources, individuals build stories about themselves in the occupational realm.

The thesis that gave rise to this reflection, as well as to the empirical research that accompanied it 1 , starts from an important premise, namely. That the conventional approaches adopted to understand and intervene vocationality within the framework of career choice have turned out to be insufficient to achieve its mission. Two reasons support this statement. On the one hand, the dynamic nature of vocation is unknown. Vocationality must be understood as a permanent process of construction of meaning. A process, present in those who are preparing to make decisions of an occupational nature, as part of their transition to working life. On the other hand, the changing conditions of a world of work marked by many uncertainties are not considered. For example, the new ways of organizing work, the short-term nature of labor relations, and the blurring of the boundaries recognized between different professions. Concerning this, the legitimate performance roles that can be assumed in each of the professions, among many others.

For the development of this analysis we did a brief review of the main approaches taken in vocational psychology throughout its existence as a field of reflection and intervention. Subsequently, we introduced theoretical elements to clarify the notion of self and identity, delving into the latter concept from a socio-cultural perspective. Next, we retaken the dominant perspectives in the study of vocational identity to finally integrate conceptual elements of cultural psychology that serve to rethink this construct. Finally, we redefined vocational identity as a set of meanings in which people link self-referential information with occupational experiences.

Vocational Psychology as a Starting Point

Today, vocational psychology is recognized as an applied specialty, focused on deepening the understanding of vocational behavior to improve career interventions (any treatment or effort aimed at enhancing an individual’s professional development or enabling them to make better career-related decisions) and inform public employment policies (Jackson & Verdino, 2012). From this conceptual horizon, it has been assumed that vocational behavior emerges when individuals pursue goals of an occupational nature. These objectives include the development of values, interests, and aspirations that will shape a person’s working life (Vondracek et al., 2014). In other words, vocational psychologists would seek to understand the way in which some characteristics of individuals contribute to make favorable occupational options visible. Its function is to assist individuals in the process of choosing and preparing for a job that suits their personal goals and competencies.

However, it should be noted that vocational psychology in its development has also been nourished by different theoretical perspectives on human behavior. These perspectives have heterogeneously informed the way in how both the phenomena under study and the methods used to approach them are conceived, as detailed below.

Conceptual Approaches in Vocational Psychology

Throughout its history, vocational psychology has always faced the challenge of solving different questions posed by the existing society. For this, it has developed different theoretical models and intervention methods in which it sought to link the personal objectives of individuals with the dominant economic activities in each era (Savickas, 2011). It is along this path that the first vocation theory arises at the beginning of the 20th century. It sought to respond to the needs and demands linked to the growing processes of industrialization, urbanization, and massive migration that characterized this era (Xu et al., 2018). All these phenomena led to organizational concerns about how workers could be efficiently placed in the right occupation. In the scenario described, it is that Frank Parsons published his work entitled “Choosing a Vocation” in 1909. In this book, he will present a frame of reference that formulates occupational guidance as a process aimed at facilitating the successful choice of a vocation as the logical result of combining three factors: a) a clear understanding and knowledge of the subject’s self (aptitudes, abilities, interests, ambitions, resources, limitations); b) a broad knowledge of the occupational world, and finally; c) a set of appropriate reasoning that articulates the two previous elements. It is within this conceptual horizon that the so-called theoretical model of person-environment fit emerges, that, as Holland (1959) proposed half a century later, seeks to link the individual to some work role according to his or her personal characteristics. In practical terms, the purpose of this conceptual perspective is to promote a career choice that, after following the prescribed methodological requirements, would be definitive. This conception of vocational psychology will be consolidated as the dominant one during most of the 20th century and so far this century (Watts & Sultana, 2004).

Nevertheless, and continuing with the historical journey, it is important to point out that as the 20th century progressed and as the world underwent geopolitical, social, cultural, and economic transformations, the need for a new type of labor force emerged. Therefore, the profile of workers employed in highly hierarchical organizations began to stand out (Savickas, 2011). This led to a new social question as to how people could develop careers within these organizations.

In this context, the so-called vocational development approach emerges (Super, 1953). This approach will propose career choice as the result of the progress of individuals through a series of predictable evolutionary stages (progress guided by maturational processes). In turn, each of the stages would be made up of tasks that should be fulfilled to ensure congruent alignment with an occupational role.

It is clear that both approaches are grounded in differential psychology and trait-and-factor theories (McIlveen & Patton, 2006), a conceptual scheme that is supported by psychometric methods. Both perspectives will start from common premises that understand vocational development as a cognitive process in which individuals use reasoning to make career decisions. They also assume that occupational choice represents a single event where there is only one alternative that would be the right one for those who are faced with a vocational decision (McIlveen & Patton, 2006). The starting point of the above conception is that psychological characteristics during development adhere to normative criteria and that once adulthood is reached, these traits will remain relatively the same in different contexts and over time (Young & Collin, 2004). In fact, these premises have been present in the local context since the middle of the last century (Bernal de Sierra, 1999; Giraldo Angel, 1960; González Y. et al., 1969). The need to identify dispositional traits and occupational requirements to ensure an objective, efficient and logical fit between individuals and their educational and occupational choices has also been dominant on the national scene (Gomez Hincapie, 1963). Approaches based on psychometric instruments that allow transcending subjectivity in the identification of individual differences (Carrillo V. et al., 1966). These approaches even offer the possibility of relating personality attributes to academic performance and job satisfaction (Salessi & Omar, 2017).

However, although theories of vocational choice and development have been and will continue to be relevant to psychology, their assumptions seem to miss the complexity of contemporary vocational behavior (Blustein et al., 2019; Bujold, 2004; McMahon & Watson, 2020). Complexity because of the social reordering of work that has been taking place, particularly and more rapidly in the last three decades (Canzittu, 2022).

Thus, and following Savickas (2012), the world of work that distinguishes the 21st century contrasts drastically with the one that existed during the immediately preceding century. In the 20th century work was characterized by secure employment conditions in stable organizations. The organizations offered a firm foundation to build a life project, allowing employees to visualize a long-term future. Instead, today’s employment landscape is largely shaped by the digital revolution and the globalization of the economy and culture. This has led to a restructuring of work bringing with it a new psychological contract between organizations and workers (Rousseau, 1995). This new contract is characterized by temporary assignments and fixed-term contractual projects that lead to new forms of employability (Canzittu, 2022; McMahon & Watson, 2020 ; Wen et al., 2022). In organizations, workers have become mere peripheral or contingent components, destined for a recurrent sale of their skills to employers who require them with an expiration date.

Consequently, the contemporary reality of the workplace compels workers to be perpetual apprentices, to commit themselves to organizations to which they render their services for predetermined periods. In addition, workers must exhibit a type of professionalism that allows them to adapt quickly to the volatile needs of their employers (Canzittu, 2022; Savickas, 2012; Wen et al., 2022). In other words, the responsibility for building a career has been transferred from organizations to individuals, a situation that demands greater effort, knowledge, and self-confidence from them.

Against this backdrop, the assumptions underlying the person-environment fit and vocational development perspectives have become obsolete, given the socio-labor conditions now in force have sharpened the complexity of the vocational phenomenon (Blustein et al., 2019; McMahon & Watson, 2020). This complexity demands visions that must be permanently contextualized in the horizon of a search that transcends diagnostic processes based exclusively on the measurement of behavioral traits. Complementarily, this renewed vision needs to explore the phenomenological life of individuals. In this sense, it is essential to learn more about the subjective and changing construction of motivations, interests, and skills of individuals. The goal now is to empower people from the realities they experience, linked to their individual world and the development environments that serve as their context (McIlveen & Patton, 2006; Sultana, 2020).

This contextualist approach will be based on a narrative perspective congruent with cultural psychology (Bruner, 2005, 2008; Hartung, 2013; McMahon, 2018). Thus stated, the aim is to answer the question that contemporary society addresses to vocational psychology. The contemporary question is how workers will be able to cope with the reorganization of work and employment in multicultural information societies (Canzittu, 2022 ; McMahon & Watson, 2020; Savickas, 2011). The question will demand a profound reordering of both theory and practice underlying vocational intervention. A conceptual renovation that will find its support in premises taken from both narrative and social constructivism. The abovementioned will lead to the conception of a self that is built and unfolds as a personal history that must be reconstructed repeatedly according to changing occupational and educational circumstances, of course, without the individual losing his or her sense of completeness, continuity, and identity because of the continuous process of reconstruction.

Derived from the above, the need arises to reformulate the constructs that have traditionally shaped the dominant approaches in vocational psychology. To this end, it is necessary to give greater relevance to theoretical categories that have been relatively marginal when analyzing vocational processes, as identity (McMahon & Patton, 2018), and to displace others as personality. This implies giving more weight to adaptation than to the maturation of internal structures; to intentionality rather than any decision; and to stories rather than psychometric test scores (Savickas, 2012). From this refocus, contextual possibilities, dynamic processes, non-linear progression, multiple perspectives, and personal patterns of career development will be highlighted. Thus, the term career is no longer understood as a sequence of occupations and jobs exercised during person lifetime. Instead, career is assumed to be a subjective construction through which individuals give meaning to their vocational behavior following their life circumstances (Gülşen et al., 2021; Savickas & Pouyaud, 2016 ; Wen et al., 2022 ).

In the new occupational scenario that characterizes the contemporary world, the concept of identity acquires preponderance. The notion of identity will facilitate the study of the process of construction of the self as a function of the social contexts surrounding individuals. Even more so, if its theoretical and comprehensive approach is carried out from the perspectives and premises of both narrative and social constructivism, in a development as the one proposed below.

Social Constructivism in Vocational Psychology

Social constructivism is a perspective that emphasizes the link between psychological phenomena and the social environment, giving primacy to the social sphere over the individual. This is because it contemplates that human functioning is the result of social interaction and relationships that precede the individual (Gergen, 2007; Kang et al., 2017; McMahon & Watson, 2020). Social constructivism is related to the cognitive processes through which people elaborate and experience their social and psychological worlds, through mental products generated from symbolic resources that are the mediators to know reality (Young & Collin, 2004). The epistemological approach underlying this theoretical position emphasizes the way in how individuals elaborate knowledge and assign meaning to their experiences within the framework of a social and personal context. Social constructivism, then, is interested in the way that external and collective reality relates to internal and individual reality, and thus orients its research interest towards those psychological processes closely linked to social processes. The contribution that this perspective makes to vocational psychology is outlined below.

First, it should be noted that constructivism makes it possible to refute the discourse of so-called personal dispositions (any of several enduring characteristics that describe or determine an individual’s behavior in a variety of situations, as personality traits). This concept is based on the assumption that it is possible to match internal traits with occupational characteristics, thanks to the support of sophisticated psychometric processes (Young & Collin, 2004). Constructivism, on the contrary, will highlight the processual nature of the self, sustained by elaborated sociocultural symbolic resources necessary to shape the psychological processes that underlie it (Bujold, 2004; Kang et al., 2017; McMahon & Watson, 2020). Likewise, from the constructivist point of view, emphasis will be placed on the situated character of the actions of individuals and the indispensable contextualization of their interests and occupational concerns in the social, economic, cultural, historical, and temporal scenarios that surround them (Kang et al., 2017; Young & Collin, 2004). In brief, the self and the efforts to build a career in an occupational and educational setting are interwoven into people’s developmental environments.

Then, it is assumed that the career is a subjective construction derived from the interaction between personal and social experience. Its configuration would take place over time and in specific contexts. While the career takes shape, the definition of the self, the development of a sense of agency and purpose also progresses, relying on mediators as narrative, autobiography, and life history (Bujold, 2004; Kang et al., 2017; McMahon & Watson, 2020 ; Young & Collin, 2004 ).

Consequently, it is proposed that the construction of the self through narrative in its various forms will be based on the negotiation of meanings within specific temporal and social contexts. The same contexts where relationships and interactions with others take place. On the other hand, it is recognized that the subjective construction of a career is an active, dynamic, and dialectical process. It is not simply a finished product. In this perspective, it is recognized that individuals act collectively, by given history and culture, in which the construction of the vocational worlds that they are part of takes place (Bujold, 2004; Kang et al., 2017; Young & Collin, 2004 ).

In short, it can be concluded that constructivism allows approaching the vocational phenomenon in an alternative and innovative way, understanding it as a process that is inscribed in socio-historical contexts that are permanently created and recreated. This conception is consistent with Bruner’s (2008) socio-cultural proposals on cognitive development, that guide the conceptualization proposed here (Gergen, 2007; Kang et al., 2017; Young & Collin, 2004). So, after recognizing the place of constructivism in this new conception of vocationality, next, this process will be approached from the notion of identity.

Identity from a Socio-Cultural Perspective

As mentioned, the complexity of the contemporary occupational world demands the adoption of approaches that give greater weight to an understanding of psychosocial dynamics that are sensitive to the contextual realities of individuals. Because of this, it is necessary to emphasize the relevance of reformulating the premises that have historically explained vocational behavior, reorienting them towards constructs as identity, intentionality, and narrative (Gülşen et al., 2021; Savickas & Pouyaud, 2016 ; Wen et al., 2022). It is in this epistemological scenario that the notion of identity takes on special meaning, since, as will be explained below, it would make it possible to link the construction of people’s vocation to their life scenarios (McMahon & Patton, 2018).

In this regard, some authors state that identity represents the link between the self and society (Hammack, 2008 ; Ozer & Schwartz, 2020). In convergence with the above, D. Holland & Lachicotte (2007) defend the socio-genetic formation of identity and assume that individuals construct personal versions of themselves based on the social realities in which they develop, thus configuring their identities. Accordingly, they assert that identity represents a way of organizing relevant and related feelings, understandings, and knowledge with a personally valued and culturally imagined social position. These identities formed on personal grounds would mediate the individual’s ability to organize and carry out the intent of the activity in the settings and occupations of the socio-cultural worlds (D. Holland & Lachicotte, 2007; Lachicotte, 2012). However, the ability for an individual to organize himself or herself in the name of identity would initially develop as an interactive transaction with others. Only then could people apply this cultural resource (identity) to their own actions (D. Holland & Lachicotte, 2007; Lachicotte, 2012).

Consequently, identities are understood as psychosocial processes through which people construct the self in action, learning (through the mediation of cultural resources) to order self-referential meanings and to organize their actions according to their socio-cultural worlds (Vågan, 2011). In short, identities will be personally meaningful and actively internalized. They are formed as a function of broader socio-cultural constructions that allow for the collective production of socially constructed worlds of interpretation and action (Lachicotte, 2012). In other words, identities are constituted as means through which individuals link the self to social roles and assign subjective meaning to these roles (Burke & Reitzes, 1991).

Based on the above, it is possible to appreciate the importance of studying vocation through the notion of identity. Doing so will make it possible to integrate under a psychosocial construct, both the subjective experience of culture and the contextual reality surrounding its configuration. Thus, it will be recognized that both the content and the functioning of the processes underlying identity are eminently socio-cultural and therefore represent a historically delimited, socially transmitted, and culturally regulated phenomenon (Esteban-Guitart et al., 2013).

For all these reasons, identity is a notion that makes it possible to understand career construction as a fluid process, socially configured, culturally derived from language, and adaptable to the interactions inherent to the contexts. Hence the importance of taking up this notion in contemporary conceptualizations of vocational psychology. In this way, this applied specialty departs from the static and essentialist conceptions of personality, that are still dominant (Stead, 2007).

It is necessary to emphasize that, from this comprehensive perspective, identity is seen as interwoven with power relations and ideologies, making it susceptible to ethnic, gender, generational, and social class socio-cultural discourses. Identity, thus assumed, will link the self with behavior, since it constitutes means through which people organize self-defining meanings in relation to the social realities they inhabit. This will make it possible to structure actions based on the self-referential information available (McMahon & Patton, 2018). In this way, the identity will give the behavior an intentional character. To the extent that identity orders the actions of individuals around a set of meanings about themselves (constructed in the daily experiences in each of the interactive scenarios where people participate), it will promote a sense of agency, of responsibility for one’s own life course (Skhirtladze et al., 2019).

Thus, identity should be recognized as having directive functions in the actions and decisions of people in different spheres of life (Vignoles et al., 2011). These competencies are derived from the internalization or appropriation of interactive cultural resources implemented in social exchanges, symbolic instruments that, when mastered by individuals, enable them to exercise control over their actions or intentional behaviors (Lachicotte, 2012). To continue advancing in the proposed conceptualization, it is convenient to specify the reiterated mention of the self to allude to identity, for this reason a brief distinction between these two notions is presented below.

Self and Identity

According to Owens & Samblanet (2013), the notion of self encompasses identity and is defined as an organized and interactive system of thoughts, feelings, identities, and motives that people attribute to themselves to characterize themselves. This system will be born with the support of language and self-reflection. For its part, identity is understood as a component that is subsumed in the broader notion of self (Owens et al., 2010) and is defined as a subset of self-referential descriptions delimited by specific life domains or roles (Sestito et al., 2015; Vondracek & Porfeli, 2011). The central quality that will distinguish the self from identity will be that the former corresponds to a process and an organization originating in self-reflection. The second can be seen as a tool that individuals or groups use to self-categorize and present themselves to the world (Owens & Samblanet, 2013 ).

Therefore, identities are categories that people use to specify who they are and to position themselves about others. In this context, the construction of the self will be limited by the abstractions of experience and the real daily experiences of individuals. Identity, on the other hand, will be demarcated by a more restricted set of representations and associated schemes of experience aligned with roles. In this sense, it would be a more relational and psychosocial construct (Vondracek & Porfeli, 2011).

Moreover, it is assumed that human beings are immersed in social structures and systems of shared meanings. Consequently, the self, identities, and representations of the world will be configured in interaction with the other people who inhabit the spaces or participate in the socio-cultural activities in which individuals habitually develop. Complementarily, individuals experience the socio-cultural conditions that frame their lives through the representations they have of themselves. Through these representations, they also organize their experiences and actions within the worlds that they are part of.

Given the above, it is worth reiterating that people construct the self and the conceptions derived from it based on the symbolic resources provided by the culture in which they are immersed. In short, there is a link between the self and those socio-cultural representations with which one interacts. Thus, identity will operate as a support for vocationality since it will determine the way individuals think about themselves concerning specific social roles (Savickas, 2012). Having made the above considerations, we now move on to situate the place of cultural psychology in its conceptual approach to the construction of identity and vocationality.

Cultural Psychology and the Construction of Identity as a Basis for Understanding Vocationality

Cultural psychology represents a set of theoretical orientations that converge in highlighting the importance of socio-cultural contexts for the functioning of individuals and the way in how these two components mutually constitute each other (Esteban-Guitart et al., 2013). In this panorama, the shared goal assumed from the different aspects of Cultural Psychology will be to understand the way in how the processes of human development take place in culture (Santamaría et al., 2019).

Accordingly, Shweder (1999) points out that cultural psychology deals with the study of the intentional or symbolic states of individuals, their intentional actions or behaviors. These volitional manifestations would be part of broader socio-cultural conceptions that were acquired through people’s participation in discourses, laws, and collective practices that are common in the communities where they interact. Likewise, Penuel & Wertsch (1995) emphasize that a socio-cultural approach to psychology implies assuming the irreducible tension between the individual functioning of human beings and the historical, social, and cultural components that surround them, accepting them as an inherent aspect of their daily actions.

Among the different conceptions that coexist within cultural psychology, we chose the one represented by the American psychologist Jerome (Bruner, 2005, 2008). This theorist considers that culture constitutes a mediating component of the actions of human beings in the world. Accordingly, he proposes that culture would be a sort of toolkit, techniques, and procedures that would allow people to understand and manage the world through human conventions represented in signs (Bruner, 1996).

Notwithstanding, it is also imperative to point out that, just as culture shapes human functioning and opens some possibilities, it also imposes some limits on the way in how people operate. Thus, it will be understood that the actions of individuals will be defined based on the toolkit of the culture in which they live. Therefore, the sense of reality that people attribute to the worlds they inhabit will always have a construction character and will be the product of the knowledge and experiences gestated from the use of the cultural toolkit that generation after generation inhabited.

Then, it should be noted that one of the most important tools for the construction of reality is narrative. The narrative represents a discursive resource through which individuals have the possibility of creating a version of the world and a place in it. It constructs the lives of those who narrate (Bruner, 1990). Narrative conceived by those means will give rise to a way of thinking and will become an instrument at the service of the creation of meanings, this will facilitate the organization of knowledge coming from daily experiences related to human intentions and actions (Bruner, 1990). The above, within the framework of the vicissitudes and consequences that trace the evolution of the different actions of the person as those related to vocational choice.

Thus, narration constitutes an instrument that will shape the cognitive mode through which the present, past, and possible human condition are built. A sense of self is gestated which, according to Bruner (1997), will be nothing more than a textual construction of how individuals situate themselves about others and to the realities they inhabit. Thus, it can be affirmed that the genesis and formation of the self takes place while human beings enter a given culture. After this, people gain access to narratives or stories linked to an specific tradition composed of a series of orthodox characters, scenarios in which they act, and actions that become comprehensible to them. In other words, these culture-specific stories represent a guide to the roles and possible worlds where action, thought, and definition of the self are permissible and desirable. All this, under a set of deontic rules that will regulate the self-referential construction (Bruner, 1997).

In fact, a vehicle through which culture transmits the epistemological and deontic contents about the self is given by folk psychology. This notion alludes to a set of normative and interdependent descriptions that regulate the functioning of human beings, their cognitions, emotions, and actions prescribe what modes of life are possible and how commits can be made within those modes of life (Bruner, 1990). The appropriation (internalization) of folk psychology by the people will occur to the extent that they master the language and intensify their interpersonal transactions within the framework of community life (Esteban-Guitart, 2012; Penuel & Wertsch, 1995 ).

Following the above, it is assumed that identity is structured through narrativized conceptions of folk psychology. In this way, people experience themselves and others based on categories established as conventional, transmitted through collective conceptions, promulgated by institutions and devices that culture has forged for this purpose. This is the case of laws, education, and the family (Bruner, 1990).

Like cultural reality, identity is a social construction, negotiated, distributed, and situated. A narrative configuration that provides people with a sense of autonomy and volition. But, at the same time, identity places the individual concerning the collective, making explicit his commitments to others and reminding him that his autonomy is limited by the symbolic, historical, and social system to which he belongs. Narrative as a cultural resource for communicating and creating realities facilitates the construction of a fully meaningful and meaningful personal world. The construction of a self, in constant revision, capable of integrating the experiences that people face daily. Similarly, the narrative provides the identity models available in society in an autobiographical format.

Thanks to the narrative a sequential structure emerges where people’s experiences acquire meaning based on a central argument that justifies the underlying intentions of a past action. This structure will also provide a margin in the outcome that allows for the integration of new experiences while facilitating the foreseeing of possible alternatives for action. In this sequential structure, three referents and temporalities are linked in a plausibly, the past world of the individuals, the present they experience, and the future they imagine, maintaining their self-referential meaning throughout the process. In this way, narrative conceptualization will stand out as the means through which individuals can produce a meaningful whole from their life events. The above, after identifying those events as part of a plot or theme under which it brings together and signifies the performances and experiences (Ricoeur, 2006). A history of themselves, that will provide them with unity and personal identity (Polkinghorne, 1991).

In synthesis, identity represents a narrative construction that will depend both on intra-subjective experience, composed of memories, emotions, ideas, beliefs, and external sources, given by social interactions and the expectations that culture delineates on those who appropriate and exercise its conventions. Individuals assume (tacit) identity models that objectify what they should be and offer prescriptions that delimit the configuration of themselves in society (Bruner, 1997). Up to this point, the most relevant conceptual coordinates have been presented to preliminarily delimit the notion of identity in general, but that also apply to the vocational sphere. Next, other details that gave rise to the adoption of vocational identity as the axis of the research carried out will be specified. An overview of the dominant approaches to their study is also presented.

Genesis and Variants of the Vocational Identity Construct

Vocational identity as a construct is the result of the preponderance of the person-environment fit and vocational development models in psychology. This construct made it possible to respond to the need to generate concepts that associate personal characteristics with work environments. Thus, the requirement for notions representing the self in terms of differentiation and consistency of preferences associated with a personality type was satisfied (Skorikov & Vondracek, 2011). This conception is based on implicit assumptions of stability of both occupations and personality traits. Although vocational identity occupied an important place in theoretical models (Hirschi, 2011b), its function was limited to accounting for an evolutionary path by being translated into an indicator of progress within the broader process of career development (Skorikov & Vondracek, 2011). Vocational identity could account for this trajectory, thanks to its timely measurement.

So far, studies on vocational identity have been conducted from two conceptualizations that, with different theoretical logics, have developed instruments for its measurement. First, there is the theory of vocational personality types and work environments, that sought to obtain a clear and stable picture of what a person might have as his or her goals, interests, and talents (J. J. Holland et al., 1980). In this perspective, the Vocational Identity Scale was developed, a test that evaluates the general level of this construct, assuming it as a product, without considering its formation process.

The second theorization of vocational identity (Porfeli et al., 2011) was traced from the lens of states. A perspective initially formulated by (Marcia, 1966), that sought to operationalize the process of identity construction based on two components: a) exploration (period of reflection and testing of various roles and life plans) and b) commitment (degree of personal investment or adherence to a specific set of goals or values, expressed in a course of action or belief). Thus, by assessing exploration and commitment in individuals, four statuses in identity development could be identified: a) achievement identity, b) foreclosure, c) moratorium, and d) diffusion. Subsequently, some refinements were introduced that nuanced or extended the four states originally proposed (Kroger & Marcia, 2011).

It should be noted that the status approach seeks to consider the identity formation process by basing its evaluation on the sub-processes that make it possible. However, the original emphasis of this perspective was more focused on the current conception of these processes (Kroger & Marcia, 2011). This meant that, in the end, this approach omitted the way in how people participate in the exploration and the way in how they acquire the respective commitments (McLean & Pasupathi, 2012).

However, and beyond the mentioned limitations, the two conceptualizations have originated important findings that today strengthen vocational identity as a theoretical construct within psychology. Thus, the two conceptualizations have made possible the statistical association of vocational identity with significant rates of progress in the career development of adolescents and young adults. In this regard, different research can be consulted (Creed et al., 2020; Hirschi, 2011c; Kvasková et al., 2022; B. Lee et al., 2020; Y. Lee et al., 2022; Li et al., 2019; Meijers et al., 2013; Pizzolitto, 2021; Porfeli & Savickas, 2012; Savickas & Porfeli, 2011), whose results show the relevance of the construct in mediating the integration of the self with occupational knowledge and therefore, of influencing vocational behavior (Jara-Castro, 2010; Y. Lee et al., 2022).

Another theoretical and empirical association that has been made of vocational identity is with some constructs as psychological well-being, purpose, satisfaction, and meaning in life (di Palma et al., 2021; Green, 2020; Hirschi, 2011a , 2012a, 2012b; Hirschi & Herrmann, 2012 ; Kvasková et al., 2022 ; Strauser et al., 2008). These constructs constitute manifestations of a protean career orientation (Hall, 2004), a notion to which vocational identity has also been related (Hirschi et al., 2017; Steiner et al., 2019). Protean career orientation refers to the motivation of individuals to take responsibility for their professional development, focusing their careers on continuous learning and the achievement of their values to reach subjective or psychological success. Evidence suggests that protean career orientation is a facilitator of a clear vocational identity.

All the results presented in the research studies consulted provide evidence of the way how vocational identity provides people with a sense of direction and meaning in life. This is to the extent that vocational identity organizes and summarizes self-referential information based on what human beings direct their actions in the occupational sphere (Christiansen, 1999; Meijers, 1998 ; Skorikov & Vondracek, 2011). Identity endows the actions of individuals with intentionality while strengthening their sense of agency by adapting their actions to a set of meanings about themselves.

Having clarified the origin of vocational identity, we will now develop a conceptualization based on the assumptions of social constructivism and cultural psychology, both theoretical coordinates already addressed in a previous part of this text. Based on these conceptual positions, some elements are introduced that seek to overcome the limitations pointed out in the dominant paradigms and allow for a deeper understanding of the vocational phenomenon.

Vocational Identity, Cultural Psychology, and Possible Vocational Worlds

This section presents a conceptual model of vocational identity, proposed as an alternative for approaching the phenomenon of vocationality in psychology. This proposal is mainly based on theoretical approaches (some of them have already been mentioned) and empirical results generated by research carried out by the authors of this proposal (to be published by the authors themselves in another article). Theoretical approaches include Bruner’s cultural psychology (1990, 1996, 1997, 2005, 2008), as previously indicated. Also, the approaches to identity from the socio-cultural perspective worked by D. Holland & Lachicotte (2007; Lachicotte, 2012). The notion of vocation elaborated by Billett (2011), and the notions of vocational identity enunciated by Meijers (1998), and Skorikov & Vondracek (2011), that served as basic notions for the theoretical proposal. The sub-components identified by Porfeli et al., (2011), based on Marcia’s classic approaches (1966), were also taken up as fundamental to operationalize vocational identity as a construct. Finally, the empirical results derived from qualitative research on the construction of vocational identity in young university students in the city of Medellin, Colombia (to be published by the same authors in another article), served as a basis for identifying other components of the model. These components were the two dimensions that make up vocational identity (personal and socio-cultural) and the mechanisms that guarantee the interaction between these two dimensions (practical and interactive experiences). The proposed theoretical model is formulated and explained below.

According to Billett (2011), vocation refers to experiences with satisfactory and meaningful occupational practices for the individual, whose exercise provides him/her with a sense of self, i. e. identity. Vocations would be central to people’s life purposes and would describe activities that have social value and provide lasting personal meaning. Accordingly, from the perspective of cultural psychology, it could be argued that vocational identity constitutes a structure in constant formation, made up of a changing set of meanings through which individuals link their motivations, interests, and competencies with acceptable career roles (Meijers, 1998; Skorikov & Vondracek, 2011). That is, meanings of self that could be related to occupational practices.

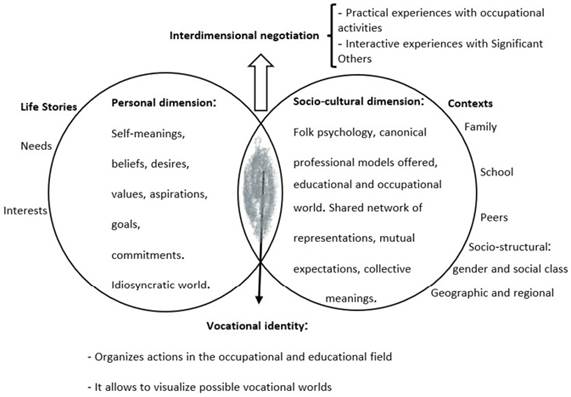

From the above perspective, vocational identity, rather than a product, would constitute a process in which people negotiate and integrate meanings of themselves with the norms and activities related to an occupation. Vocational identity, therefore, represents the synthesis resulting from the interaction between individuals’ perception of the occupational world and their perception of themselves (Klotz et al., 2014). The way these different components and dimensions are integrated is illustrated in Figure 1.

As a structure of meanings in permanent construction, vocational identity will allow organizing in a narrative format, feelings, understandings, and knowledge related to a personally valued and socio-culturally available occupational position (D. Holland & Lachicotte, 2007 ; Lachicotte, 2012). This structure will operate as a mediator of the vocational behavior of individuals, and as such, will order their actions in the occupational sphere, giving them an intentional character according to their vital scenarios and their biographical and socio-cultural worlds.

Figure 1

:

Conceptualization of Vocational Identity from the Perspective of

Cultural Psychology (Own elaboration)

Accordingly, the sub-processes that are traditionally recognized as constituting vocational identity, namely career exploration and commitment to a career, represent actions derived from the set of emerging meanings that make up this construct (Porfeli et al., 2011). In this way, vocational identity will be expressed and materialized in actions as exploration, choice, and commitment to a particular occupational field; behaviors organized according to a self-referential concept. On the other hand, the immersion of individuals in concrete educational and work experiences, as well as the interaction with significant social references, will promote a constant reformulation of vocational identity.

This reformulation process will be facilitated by a narrative configuration that will shape it. The narrative configuration will make possible the continuous incorporation of new information into the plot of a vocational life that gives meaning to new experiences, without prejudice to previous ones. All this will favor the projection of new lines of action by individuals in the occupational area. Thus, vocational identity will make possible vocational worlds visible. Possible vocational worlds are occupational or educational environments, scenarios for the exercise of activities that individuals recognize as meaningful and satisfactory for their life purposes and goals (Billett, 2011). In this way, access to possible vocational worlds will stimulate career exploration and commitment, giving processual functionality to vocational identity.

In terms of its construction, as illustrated in Figure 1, vocational identity is configured based on two dimensions, one personal and the other sociocultural. The first would be given by the idiosyncratic world of individuals, a component derived from their life stories and constituted by beliefs, desires, values, aspirations, goals, intentions, hopes, and commitments; meanings of self, that express interests and needs, and which require the socio-cultural dimension to be fully manifested. In contrast, the socio-cultural dimension will be determined by the dominant folk psychology in the developmental contexts where people participate. This dimension represents a normative framework that informs individuals about the canonical vocational models to be considered for their identity defined in terms of occupation. That is, the admissible and desirable ways to build a life project based on a profession.

Accordingly, the first dimension will be mediated by the interests and needs of the personal world of individuals that, in turn, will find expression in the socio-cultural worlds of which they are a part. The two components mentioned above, the personal and the sociocultural, will maintain a constant dynamic of negotiation that takes place thanks to two mechanisms. On the one hand, the contact of individuals through direct experiences with occupational and/or educational practices. On the other hand, through interaction with significant social referents who, with their actions, stories, or forms of social support, exemplify, encourage, or empower people to choose or discard possible vocational alternatives. As a result of this negotiation process, the vocational identity would emerge.

People will appropriate the meanings underlying the conventional occupational practices exercised in their daily contexts and based on this, they will begin to configure or reconfigure their vocational identity. In this way, the set of mutual expectations, communal representations, and meanings embodied in the culture end up shaping the vocational identity. The culture embodied in the popular psychology of family, school, or peer contexts, in addition to shaping identity, will also impose limits on the way in how individuals can operate. This is because culture mediates and delimits the scope of the actions of individuals in the different spheres in which they choose to work.

Thus, it is possible to affirm that even though the personal dimension requires the mediation of the socio-cultural dimension for an individual to commit to an occupational or educational alternative and recognize it as his or her vocation, the experiences with that particular option must be personally meaningful and of value to him or her. Commitment implies the choice of an occupational path and a clear identification with this choice. In other words, the establishment of a personal link with the career decision made by the individual is required, allowing the development of a subjective connection or link that reflects the individual’s trust and attachment to the chosen occupational field. The social dimension contextualizes and shapes the configuration of vocational identity, but it is the personal dimension that justifies the commitments that people make to a given career alternative.

It should be noted that even if people engage in a variety of career, occupational or educational practices, not all will be evaluated as fundamental for maintaining and consolidating a sense of self. The recognition of a professional field as a vocation will depend on the one hand, on the meaning that an occupational practice may have for a person in terms of the contribution it makes to his or her identity. On the other hand, the resources in terms of occupational or educational practices and discourses, available in the different development scenarios and which will serve as a basis for constructing possible vocational worlds in different career fields.

Therefore, in its configuration process, the vocational identity will be distributed among the developmental contexts of individuals. That is, among the scenarios of collectively shared meaning where collective scaffolding dynamics take place, materialized in support structures or assistance in the framework of the daily interactions that significant others routinely provide. This scaffolding will facilitate the appropriation of the dominant meanings in the social interactions of each of the socio-cultural environments where people live. From this perspective, the value of the narrative approach to the vocation will be highlighted, as it will allow individuals to integrate different experiences with occupational and educational activities into an autobiographical account. The plot or central argument of these autobiographical stories will be linked to the construction of a possible vocational world based on a career.

Whether or not people can see themselves performing work related to an occupational environment, it will depend on whether it is in harmony with the interests and needs that make up the personal dimension of their lives. In addition, these occupational tasks must be in line with the canonical requirements of the social environments in which individuals act daily. The latter will become the cornerstone for the configuration of possible vocational worlds.

Practical Implications

Implementing the proposed conceptual model of identity as a strategy to address vocational behavior and its manifestation in possible educational and professional choices of individuals, entails differential aspects. These aspects will be highlighted below.

First, a narrative approach to vocation and career choice as the one proposed would give access to the phenomenological world of individuals. This would increase the veracity of the process since the lives of individuals, with all their subjective implications, concerns, and experiences, would be brought to the foreground. This, in turn, makes it possible to maintain the process of constructing a vocational identity in the context of everyone’s life. In this way, the imposition of psychometric realities that in a decontextualized manner seek to align individuals with work environments based on traits that describe dominant aptitudes is transcended. Thus, with a narrative perspective of vocational identity, it is possible to highlight the value for an individual to feel personally linked to an occupational or educational activity. In other words, the subjective meaning of exercising a profession.

In the applied field of educational counseling, implementing narrative methods would allow us to understand the psychosocial dynamics inherent in the construction of identity meanings of young people. This self-referential information is subsequently used by the young people to interpret occupational and educational experiences from which they intentionally orient their actions towards the formulation of a life project. It would also facilitate the identification of barriers that scenarios as gender, socioeconomic level or religion impose on the construction of identity and, of course, the obstacles that these scenarios represent for people to visualize possible vocational worlds. All of which would encourage the consolidation of biographically congruent life projects that is, based on the individual’s own experiences congruent with the economic and political realities in which individuals live to promote their empowerment in the face of an increasingly volatile contemporary labor market.

Conclusion

The historical and conceptual journey made in this article showed that in epistemological terms, vocational psychology transited from a mechanistic paradigm represented by a person-environment fit model (emphasis on traits) to an organicist vision. This organicist vision was based on developmental premises and became a model anchored in evolutionary stages, that later gave rise to what was called vocational development. Currently, a contextualist approach has emerged, based on cultural psychology and the use of narrative as a discursive tool. With its functional characteristics, narrative equips individuals with the reflective skills necessary to take responsibility for their own occupational and educational trajectory. The latter option is positioned as the most pertinent and viable in contemporary times, given the profound changes that have taken place in current labor structures and dynamics. In this new scenario, vocational identity emerges as a key construct to approach the study of vocational behavior. This is because vocational identity considers the socio-cultural dynamics that contextualize it and shape the actions of individuals in a constantly changing work and academic environment.

References

Notes

References

Bernal de Sierra, F. Á. (1999). La psicología escolar: Cincuenta años. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 105–111. Recuperado a partir de https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/psicologia/article/view/32148

Billett, S. (2011). Vocational education. Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1954-5

Blustein, D. L., Ali, S. R., & Flores, L. Y. (2019). Vocational Psychology: Expanding the vision and enhancing the impact. The Counseling Psychologist, 47(2), 166–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000019861213

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education. Harvard University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674251083

Bruner, J. (1997). A narrative model of Self-Construction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 818(1 Self Across P), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48253.x

Bruner, J. (2005). Cultural Psychology and its functions. Constructivism in the Human Sciences, 10(1/2), 53–63. http://ezproxy.unal.edu.co/scholarly-journals/cultural-psychology-functions/docview/204577695/se-2?accountid=137090

Bruner, J. (2008). Culture and mind: Their fruitful incommensurability. Ethos, 36(1), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1352.2008.00002.x

Bujold, C. (2004). Constructing career through narrative. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(3), 470–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.12.010

Burke, P. J., & Reitzes, D. C. (1991). An identity theory approach to commitment. Social Psychology Quarterly, 54(3), 239. https://doi.org/10.2307/2786653

Canzittu, D. (2022). A framework to think of school and career guidance in a vuca world. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 50(2), 248–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2020.1825619

Carrillo, V. R., Chica, M. E., Urdaneta, B. O., & Olivera, C. M. (1966). Construcción y estandarización de pruebas de aptitud y de conocimientos utilizables en orientación profesional. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 11(1–2), 31–61. https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/psicologia/article/view/33381

Christiansen, C. H. (1999). Defining lives: Occupation as identity: An essay on competence, coherence, and the creation of meaning. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 53(6), 547–558. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.53.6.547

Creed, P. A., Kaya, M., & Hood, M. (2020). Vocational identity and career progress: The intervening variables of career calling and willingness to compromise. Journal of Career Development, 47(2), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845318794902

di Palma, T., Sica, L. S., Sestito, L. A., & Ragozini, G. (2021). Le esperienze lavorative precoci nella promozione dell’identità vocazionale e del benessere nei tardo adolescenti: il caso dell’esperienza di alternanza scuola-lavoro. Psicologia della Salute, 1, 13–31. https://doi.org/10.3280/PDS2021-001003

Esteban-Guitart, M. (2012). An interpretation on cultural psychology: Some theoretical principles and applications; [Una interpretación de la psicología cultural: Aplicaciones prácticas y principios teóricos]. Suma Psicologica, 18(2), 65 – 88. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84863628440&partnerID=40&md5=f1f2176dfad274bf71a57882cf069a9e

Esteban-Guitart, M., Vila, I., & Ratner, C. (2013). El carácter macrocultural de la identidad nacional. Estudios de Psicología, 34(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1174/021093913805403129

Gergen, K. (2007). El construccionismo social y la práctica pedagógica. In A. M. Estrada & S. Diazgranados (Eds.), Construccionismo social. Aportes para el debate y la práctica (pp. 213–244). Uniandes.

Giraldo Angel, J. (1960). Universidad: Artes y ciencias y orientación profesional. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 5(1), 3–5. https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/psicologia/article/view/32475

Gomez Hincapie, B. (1963). Exploración de aptitudes al nivel del quinto año de primaria con miras a una orientación vocacional. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 8(2), 149–162. https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/psicologia/article/view/32709

González Y., J., Echeverry A., H., & Montoya V., R. (1969). Problemas de los estudiantes que buscaron orientación en 1966 y 1967. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 14(1–2), 89–95. https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/psicologia/article/view/34519

Green, Z. A. (2020). The mediating effect of well-being between generalized self-efficacy and vocational identity development. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 20(2), 215–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-019-09401-7

Gülşen, C., Seçim, G., & Savickas, M. (2021). A career construction course for high school students: Development and field test. The Career Development Quarterly, 69(3), 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12268

Hall, D. T. (2004). The protean career: A quarter-century journey. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.006

Hammack, P. L. (2008). Narrative and the Cultural Psychology of Identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(3), 222–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868308316892

Hartung, P. J. (2013). Career as story: Making the narrative turn. In W. B. Walsh, M. L. Savickas, & P. Hartung (Eds.), Handbook of Vocational Psychology: Theory, research, and practice, 4th ed. (pp. 33–52). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203143209

Hirschi, A. (2011a). Effects of orientations to happiness on vocational identity achievement. The Career Development Quarterly, 59(4), 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2011.tb00075.x

Hirschi, A. (2011b). Vocational identity as a mediator of the relationship between core self-evaluations and life and job satisfaction. Applied Psychology, 60(4), 622–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2011.00450.x

Hirschi, A. (2011c). Relation of vocational identity statuses to interest structure among swiss adolescents. Journal of Career Development, 38(5), 390–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845310378665

Hirschi, A. (2012a). Callings and work engagement: Moderated mediation model of work meaningfulness, occupational identity, and occupational self-efficacy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(3), 479–485. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028949

Hirschi, A. (2012b). Vocational identity trajectories: Differences in personality and development of well–being. European Journal of Personality, 26(1), 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.812

Hirschi, A., & Herrmann, A. (2012). Vocational identity achievement as a mediator of presence of calling and life satisfaction. Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 309–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711436158

Hirschi, A., Jaensch, V. K., & Herrmann, A. (2017). Protean career orientation, vocational identity, and self-efficacy: an empirical clarification of their relationship. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(2), 208–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2016.1242481

Holland, D., & Lachicotte, Jr., W. (2007). Vygotsky, Mead, and the new sociocultural studies of identity. In H. Daniels, M. Cole, & J. Wertsch (Eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Vygotsky (pp. 101–135). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL0521831040.005

Holland, J. J., Gottfredson, D. C., & Power, P. G. (1980). Some diagnostic scales for research in decision making and personality: Identity, information, and barriers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6), 1191–1200. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077731

Holland, J. L. (1959). A theory of vocational choice. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 6(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040767

Jackson, M. A., & Verdino, J. R. (2012). Vocational Psychology. In R. W. Rieber (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the History of Psychological Theories (pp. 1157–1170). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0463-8_304

Jara-Castro, L. I. (2010). Identidad vocacional en el tránsito del colegio a la universidad y en los primeros años de vida universitaria. Persona, 0(013), 137. https://doi.org/10.26439/persona2010.n013.269

Kang, Z., Kim, H., & Trusty, J. (2017). Constructivist and social constructionist career counseling: A Delphi study. Career Development Quarterly, 65(1), 72 – 87. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12081

Klotz, V. K., Billett, S., & Winther, E. (2014). Promoting workforce excellence: formation and relevance of vocational identity for vocational educational training. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 6(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-014-0006-0

Kroger, J., & Marcia, J. E. (2011). The identity statuses: Origins, meanings, and interpretations. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of Identity Theory and Research (pp. 31–53). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_2

Kvasková, L., Hlado, P., Palíšek, P., Šašinka, V., Hirschi, A., Ježek, S., & Macek, P. (2022). A longitudinal study of relationships between vocational graduates’ career adaptability, career decision-making self-efficacy, vocational identity clarity, and life satisfaction. Journal of Career Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1177/10690727221084106

Lachicotte, W. (2012). Identity, agency and social practice. In H. Daniels, H. Lauder, & J. Porter (Eds.), Educational Theories, Cultures and Learning: A Critical Perspective (pp. 223 – 236). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203379417

Lee, B., Song, B., & Rhee, E. (2020). Cognitive processes and their associations with vocational identity development during emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 8(6), 530–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818804681

Lee, Y., Kim, Y., Im, S., Lee, E., & Yang, E. (2022). Longitudinal associations between vocational identity process and career goals. Journal of Career Development, 49(3), 569–584. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845320955237

Li, M., Fan, W., Cheung, F. M., & Wang, Q. (2019). Reciprocal associations between career self-efficacy and vocational identity: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Career Assessment, 27(4), 645–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072718796035

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(5), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023281

McIlveen, P., & Patton, W. (2006). A critical reflection on career development. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 6(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-006-0005-1

McLean, K. C., & Pasupathi, M. (2012). Processes of identity development: Where I am and how I got there. Identity, 12(1), 8–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2011.632363

McMahon, M. (2018). Narrative career counselling: A tension between potential, appeal, and proof. Introduction to the special issue. Australian Journal of Career Development, 27(2), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038416218785537

McMahon, M., & Patton, W. (2018). Systemic thinking in career development theory: contributions of the Systems Theory Framework. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 46(2), 229 – 240. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2018.1428941

McMahon, M., & Watson, M. (2020). Career counselling and sustainable decent work: Relationships and tensions. South African Journal of Education, 40(Suppl1), S1–S9. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40ns1a1881

Meijers, F. (1998). The development of a career identity. International Journal for the Advance ment of Counselling, 20(3), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005399417256

Meijers, F., Kuijpers, M., & Gundy, C. (2013). The relationship between career competencies, career identity, motivation and quality of choice. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 13(1), 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-012-9237-4

Owens, T. J., Robinson, D. T., & Smith-Lovin, L. (2010). Three faces of identity. Annual Review of Sociology, 36(1), 477–499. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134725

Owens, T. J., & Samblanet, S. (2013). Self and Self-Concept. In J. DeLamater, & A. Ward, (Eds.), Handbook of Social Psychology (pp. 225–249) Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6772-0_8

Ozer, S., & Schwartz, S. (2020). Identity development in the era of globalization: Globalization-based acculturation and personal identity development among Danish emerging adults. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2020.1858405

Parsons, F. (1909). Choosing a vocation. In Choosing a vocation. Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

Penuel, W. R., & Wertsch, J. V. (1995). Vygotsky and identity formation: A sociocultural approach. Educational Psychologist, 30(2), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3002_5

Pizzolitto, E. (2021). Vocational identity and students’ college degree choices: a preliminary study. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2021.1918326

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1991). Narrative and self-concept. Journal of Narrative and Life History, 1(2–3), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.1075/jnlh.1.2-3.04nar

Porfeli, E. J., Lee, B., Vondracek, F. W., & Weigold, I. K. (2011). A multi-dimensional measure of vocational identity status. Journal of Adolescence, 34(5), 853–871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.02.001

Porfeli, E. J., & Savickas, M. L. (2012). Career Adapt-Abilities Scale-USA Form: Psychometric properties and relation to vocational identity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 748–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.009

Ricoeur, P. (2006). La vida: Un relato en busca de narrador. Agora: Papeles de Filosofía, 25(2), 9–22. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2565910

Rousseau, D. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452231594

Salessi, S. M., & Omar, A. (2017). Satisfacción laboral: Un modelo explicativo basado en variables disposicionales. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 26(2), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.15446/rcp.v26n2.60651

Santamaría, A., Cubero, M., & de la Mata, M. L. (2019). Towards a cultural psychology: Meaning and social practice as key elements. Universitas Psychologica, 18(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy18-1.tcpm

Savickas, M. L. (2011). New Questions for vocational psychology: Premises, paradigms, and practices. Journal of Career Assessment, 19(3), 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072710395532

Savickas, M. L. (2012). Life design: A paradigm for career intervention in the 21st century. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-6676.2012.00002.x

Savickas, M. L., & Porfeli, E. J. (2011). Revision of the career maturity inventory. Journal of Career Assessment, 19(4), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711409342

Savickas, M. L., & Pouyaud, J. (2016). Life design: a general model for career intervention in the 21st century. Psychol. Fr. 61, 5–14. Psychol. Fr., 61, 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psfr.2013. 11.003

Sestito, L. A., Sica, L. S., Ragozini, G., Porfeli, E., Weisblat, G., & di Palma, T. (2015). Vocational and overall identity: A person-centered approach in Italian university students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.10.001

Shweder, R. A. (1999). Why cultural psychology? Ethos, 27(1), 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.1999.27.1.62

Skhirtladze, N., van Petegem, S., Javakhishvili, N., Schwartz, S. J., & Luyckx, K. (2019). Motivation and psychological need fulfillment on the pathway to identity resolution. Motivation and Emotion, 43(6), 894 – 905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09795-5

Skorikov, V. B., & Vondracek, F. W. (2011). Occupational identity. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of Identity Theory and Research (pp. 693–714). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_29

Stead, G. B. (2007). Cultural psychology as a transformative agent for vocational psychology. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 7(3), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-007-9125-5

Steiner, R. S., Hirschi, A., & Wang, M. (2019). Predictors of a protean career orientation and vocational training enrollment in the post-school transition. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112, 216–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.03.002

Strauser, D. R., Lustig, D. C., & Çiftçi, A. (2008). Psychological well-being: Its relation to work personality, vocational identity, and career thoughts. The Journal of Psychology, 142(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.3200/JRLP.142.1.21-36

Sultana, R. G. (2020). For a postcolonial turn in career guidance: the dialectic between universalisms and localisms. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2020.1837727

Super, D. E. (1953). A theory of vocational development. American Psychologist, 8(5), 185–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0056046

Vågan, A. (2011). Towards a sociocultural perspective on identity formation in education. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 18(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749031003605839

Vignoles, V. L., Schwartz, S. J., & Luyckx, K. (2011). Introduction: Toward an integrative view of identity. In S. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of Identity Theory and Research (pp. 1–27). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_1

Vondracek, F. W., Ford, D. H., & Porfeli, E. J. (2014). A living systems theory of vocational behavior and development. Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-662-2

Vondracek, F. W., & Porfeli, E. J. (2011). Fostering self-concept and identity constructs in developmental career psychology. In P. J. Hartung & L. M. Subich (Eds.), Developing self in work and career: Concepts, cases, and contexts. (pp. 53–70). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12348-004

Watts, A. G., & Sultana, R. G. (2004). Career guidance policies in 37 countries: Contrasts and common themes. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 4(2–3), 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-005-1025-y

Wen, Y., Li, K., Chen, H., & Liu, F. (2022). Life design counseling: Theory, methodology, challenges, and future trends. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.814458

Xu, M., David, J. M., & Kim, S. H. (2018). The fourth industrial revolution: Opportunities and challenges. International Journal of Financial Research, 9(2), 90. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijfr.v9n2p90

Young, R. A., & Collin, A. (2004). Introduction: Constructivism and social constructionism in the career field. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(3), 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.12.005

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Javier O Beltrán-Jaimes, Moisés Esteban-Guitart. (2025). Narrative construction of vocational identity in university students: The role of influential experiences and significant others in the framework of cultural psychology. Culture & Psychology, 31(3), p.907. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X241285579.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The RCP is published under the Creative Commons license and can be copied and reproduced according to the conditions of this license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5). RCP articles are available online at https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/psicologia/issue/archive. If you would like to subscribe to the RCP as reader, please go to https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/psicologia/information/readers and follow the instructions mentioned in the webpage. Additionally, a limited number of print journals are available upon request. To request print copies, please email revpsico_fchbog@unal.edu.co.