Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma. A case report

Leiomiosarcoma hepático primario. Reporte de un caso

Palabras clave:

Leiomyosarcoma, Sarcoma, Hepatic neoplasms, Hepatectomy, Smooth muscle actin. (en)Leiomiosarcoma, Sarcoma, Neoplasias hepáticas, Hepatectomía, Actina de músculo liso. (es)

Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma is extremely rare among cases of liver tumors in adults, with an incidence of 0.1 and 1%. This paper describes the case of a 55 year-old man with a clinical evolution of five months consisting of abdominal pain, a large hard lump, weight loss, shortness of breath and fever.

A three-phase computed tomography (CT) showed a hypercaptive mass at its periphery during hypodense arterial phase at its center, located in segments VI and VI, without a plane of separation of the liver. Due to the symptoms, the patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy, finding a cerebroid mass of 40 x 40 cm; a lumpectomy without hepatectomy was performed, leaving free surgical margins.

The diagnosis was largely made through a histopathological assessment, finding stromal multinucleated pleomorphic forms, desmin (+), SMA (smooth muscle actin) and MSA (muscle specific actin) (+), Ki67 (+) and negative for S100 (protein S100) and CD117 antibody, which confirmed the high grade pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma diagnosis. The patient was discharged 16 days after admission once his condition improved, and was referred to the oncology department for adjuvant chemotherapy.

Given the size of the mass, the prognosis was bleak, which left surgery as the only option to offer survival expectations through regulated or "atypical" hepatectomies along with safety margins and liver transplantation. With this in mind, the first option was chosen; six months after surgery, with clinical improvement and adjuvant therapy, the patient, still with unfavorable prognosis, remained stable attending multidisciplinary medical management controls.

El leiomiosarcoma hepático primario es un tumor extremadamente raro entre los casos de tumores hepáticos en adultos, presentan-do una incidencia de 0.1 y 1%. En este artículo se presenta el caso de un hombre de 55 años con cuadro clínico de cinco meses de evolución que consiste en dolor abdominal, presencia de masa dura, no móvil, de gran tamaño, pérdida de peso, disnea y fiebre.

La tomografía axial computarizada (TAC) trifásica mostró masa hipercaptante en su periferia durante fase arterial hipodensa en su centro, localizada en segmentos VII y VIII, sin plano de separación del hígado. Debido a su sintomatología, el paciente fue intervenido quirúrgicamente por laparatomía exploratoria, hallándose masa cerebroide de 40 x 40cm, razón por la cual se practicó una tumorectomía sin hepatectomía, dejando bordes quirúrgicos libres. El diagnóstico se realizó, en gran parte, mediante evaluación histopatológica, observándose estroma con formas multinucleadas pleomórficas, desmina (+), SMA (actina de musculo liso) y MSA (actina músculo específica) (+), Ki67 (+) y negativo para S100 (proteína S100) y anticuerpo CD117, lo que confirmó el diagnóstico de leiomiosarcoma pleomórfico de alto grado. Una vez presentó una notoria mejoría, el paciente fue dado de alta a los 16 días de su ingreso y fue derivado al servicio de oncología para su adyuvancia con quimioterapia. Dado el tamaño de la masa encontrada, el pronóstico fue poco alentador, lo que hizo que el tratamiento quirúrgico fuera la única opción que ofreciera expectativas de supervivencia mediante hepatectomías regladas o “atípicas” con márgenes de seguridad e incluso trasplante hepático. Teniendo en cuenta lo anterior, se optó por la primera opción; tras seis meses de la cirugía, observándose mejoría clínica, además del tratamiento adyuvante, el paciente, aún con pronóstico desfavorable, permanecía estable, asistiendo a controles bajo manejo médico multidisciplinario

Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma.

A case report

Palabras clave: Leiomiosarcoma; Sarcoma; Neoplasias hepáticas; Hepatectomía; Actina de músculo liso.

Keywords: Leiomyosarcoma; Sarcoma; Hepatic neoplasms; Hepatectomy; Smooth muscle actin.

Jhon Mauricio Coronel Ruilova

Resident, General Surgeon

Hospital Luis Vernaza

Guayaquil – Ecuador

José Enrique Zúñiga Bohórquez

Physician, Sala San Miguel – Hospital Luis Vernaza.

Head, Hepatic transplant service – Hospital Luis Vernaza

Professor, Universidad de Especialidades Espíritu Santo

Guayaquil – Ecuador

Lincoln Alexander Cabezas Barragán

Head, Hepatic transplant service – Hospital Luis Vernaza

Profesor, Universidad de Especialidades Espíritu Santo

Physician, Sala San Aurelio – Hospital Luis Vernaza

Guayaquil – Ecuador

Correspondig author

Coronel JM. Hospital Luis Vernaza,

General Surgery departament. Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Phone number: +593 098-4677261.

Email: jo97coronel@hotmail.es

ABSTRACT

Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma is extremely rare among cases of liver tumors in adults, with an incidence of 0.1 and 1%. This paper describes the case of a 55 year-old man with a clinical evolution of five months consisting of abdominal pain, a large hard lump, weight loss, shortness of breath and fever.

A three-phase computed tomography (CT) showed a hypercaptive mass at its periphery during hypodense arterial phase at its center, located in segments V and VI, without a plane of separation of the liver. Due to the symptoms, the patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy, finding a cerebroid mass of 40 x 40 cm; a lumpectomy without hepatectomy was performed, leaving free surgical margins.

The diagnosis was largely made through a histopathological assessment, finding stromal multinucleated pleomorphic forms, desmin (+), SMA (smooth muscle actin) and MSA (muscle specific actin) (+), Ki67 (+) and negative for S100 (protein S100) and CD117 antibody, which confirmed the high grade pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma diagnosis. The patient was discharged 16 days after admission once his condition improved, and was referred to the oncology department for adjuvant chemotherapy.

Given the size of the mass, the prognosis was bleak, which left surgery as the only option to offer survival expectations through regulated or “atypical” hepatectomies along with safety margins and liver transplantation. With this in mind, the first option was chosen; six months after surgery, with clinical improvement and adjuvant therapy, the patient, still with unfavorable prognosis, remained stable attending multidisciplinary medical management controls.

IntroducTIOn

Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma (PHL) is an extremely rare tumor. In 2011, the English literature reported less than 50 patients with this type of tumor (1,2). To date, in the context of this study, there are no reports of similar cases in Ecuador, and by 2014, there were very few cases reported in Latin America (3).

In adults, primary liver sarcomas are a group of rare tumors, representing between 0.1 and 1% of all existing malignant liver tumors in this population (4). Usually, they develop in the uterus, the retroperitoneum, genital organs, lungs, liver and large vessels (5); on the other hand, PHL generate in the smooth muscle cells of intrahepatic, bile ducts or round ligament vascular structures (6).

Their unusualness, image manifestations and non-specific clinical presentation make early diagnosis difficult (7). Currently, diagnosis can be made before surgery through cytology or image-guided percutaneous biopsy or after surgery (8-12). However, the differential diagnosis between primitive or metastatic liver sarcoma may present difficulties sometimes (9), reason why the anatomopathological study is fundamental. The histopathological diagnosis is characterized by the presence of diffuse infiltrates and uniform spindle-shaped cells with hyperchromatic nuclei (8,9), while a positive reaction for desmin, SMA, MSA, Ki67 and a negative reaction for S100 and CD117 are observed in immunohistochemistry.

Resective surgery is the best treatment option for this condition; the same surgical principles of soft tissue sarcoma surgery should be kept, with margin cancer liver resection as the most appropriate choice or gold standard. Nevertheless, due to the advanced stage of the disease at diagnosis, lumpectomy or enucleation, followed by treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy, may be another therapeutic approach to consider, even in cases with metastases (10), leaving liver transplant as the last resort.

Clinical case

Male patient, 55 years old, professional working at an office with no relevant medical history, who denied using or consuming alcohol and tobacco, and reported a family history of diabetes mellitus, esophageal cancer and ocular melanoma. The clinical picture of the patient presented five months of evolution characterized by oppressive abdominal pain of moderate intensity, located in the right upper quadrant and umbilical region, accompanied by a rigid, hard abdominal mass of about 20 cm in diameter, painful on palpation (Figure 1), hyporexia and weight loss of about 45 pounds in 100 days, dyspnea on moderate efforts, afternoon fever one month prior to hospitalization, and stable vital signs.

Fig 1. Patient’s morphology. Large tumor mass in the right abdomen.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

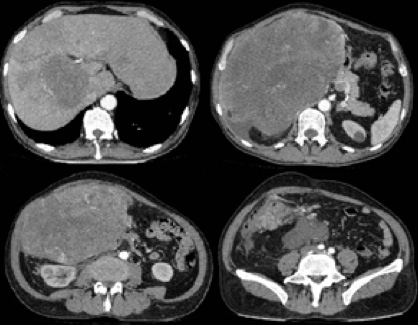

Mild normocytic hypochromic anemia (hemoglobin: 10.1mg / dl), normal hepatic and cholestatic function, normal coagulation times and acute phase reactants without alterations were observed through tests. Also, normal results of tumor markers such as CEA, alpha-fetoprotein, CA 125, CA 15-3, CA 19-9 and CA 72-4 were obtained. Abdominal ultrasound showed a hypoechoic and vascularized tumor mass in the liver bottom of approximately 30 x 20 cm (Figure 2). Moreover, plain abdominal radiograph showed a radiopaque image in the hypochondria and right flank. Three-phase computed tomography angiography of the abdomen showed a hypercaptive mass on its periphery, hypodense center in heterogeneous portal and late arterial phase, located in liver segments V and VI, without a plane of separation of the liver, in addition to retroperitoneal adenomegaly (Figure 3).

Fig 2. 2D abdominal ultrasound. Large, hypoechoic liver mass with vascularization.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

Fig 3. Three-phase tomography angiography. Large tumor mass in the right hepatic lobe, segments V and VI, which moves intra-abdominal organs.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

Finally, colonoscopy revealed normal-looking mucosa and decreased light at the ascending colon due to an apparent extrinsic compression. Exploratory laparotomy was performed to improve the clinical condition of the patient, finding a large, encapsulated, cerebroid tumor in liver bed, segments V and VI, of about 40x40 cm, displacing the right diaphragm and surrounding abdominal structures. A lumpectomy without hepatectomy was performed, with free surgical margins in sample freeze; also, neighboring structures were released and no masses, lymph nodes or metastatic seeding were identified with the naked eye. No intraoperative surgical complications occurred (Figure 4).

Fig 4. Visualization during exploratory laparotomy of primary, multilobulated, cerebroid, encapsulated hepatic leiomyosarcoma located in the right hepatic lobe.

Figure 4a. Tumoration dependent on hepatic segments V and VI.

Figure 4b. Tumor exposed once extracted from the liver.

Figure 4c. Longitudinal section of the tumor showing the macroscopic structure.

Figure 4d. Extended subcostal wound closure used in this surgical procedure.

Anatomopathological study (Figure 5) reported a malignant multilobulated tumor with the following characteristics: weight 4341 g; size 38 x 35 x 20cm; encapsulated, with irregular edges and cavitated; mesenchymal strain composed of spindle cells; with elongated core and numerous mitoses. Meanwhile, the immunohistochemical study showed positive desmin, positive SMA and MSA, positive Ki67 in 80% of cells and negative for S100 and CD117, confirming the diagnosis of high-grade pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma.

Fig 5. Histological and immunohistochemical study.

5.a. Fusiform muscle malignant cells with elongated core and necrosis areas, typical in this kind of tumor, are observed (staining with hematoxylin-eosin x100).

5.b. Presence of numerous mitosis, interwoven fascicles and pink cytoplasm with numerous pleomorphic multinucleated forms (staining with H&E x400).

5.c Immunohistochemistry reveals positive desmin sample with presence of typical smooth muscle cells (original magnification: x50).

The patient was hospitalized for 16 days; after showing a favorable evolution, he was discharged and ordered monthly outpatient follow-up. He was also referred to the oncology department to initiate adjuvant chemotherapy every 25 days in three cycles, observing the clinical course and conforming to the requirements, with the possibility of subsequent radiotherapy to control clinical, imaging and laboratory parameters, which is currently pending. Six months after surgery, still with unfavorable prognosis, the patient was stable and attending multidisciplinary medical controls.

Discussion

Clinical manifestations of PHL are not specific and, usually, tumors are asymptomatic before enlargement (11,12). The average age of onset is between 40 and 50, with extreme ages of 22 and 77 (13). The most common symptom is mild to severe pain in the upper abdomen, accompanied by weight loss, afternoon fever and asthenia (14). Clinical examination allows identifying palpable abdominal mass or hepatomegaly in right-epigastric hypochondriac region. In general, non-specific increases in some biochemical function/liver damage parameters can be observed (bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase or transaminases) unlike specific tumor markers, as in this case, which does occur in sarcomas in other parts of the body.

On the other hand, imaging does not provide specific data (16,17), because ultrasound shows a hypoechoic liver tumor, while three-phase CT shows a well-defined, heterogeneous, hypodense or isodense mass through central necrosis areas and peripheral enhancement, or as a thick wall cystic mass (18), with an angiographic pattern of peripheral avascular mass or important pathological neovascularization (19), superimposed on any liver tumor. Finally, through nuclear magnetic resonance, a heterogeneous area with hypointense lesion on T1 and hyperintense lesion on T2, with possible encapsulation, is observed (2).

The most common site of tumor is the right lobe and metastases of about 40% at the time of diagnosis are common (6), which is consistent with data reported here. Therefore, the differential diagnosis must be made between various types of benign and malignant hepatic solid tumors (20,21) such as hepatocarcinomas of different strain (22), primitive or metastatic sarcoma (8), and even sarcomas of the retrohepatic vena cava (23).

Today, and in most case series (20,24,25), the diagnosis of hepatic sarcoma can be established preoperatively, through image-guided percutaneous biopsy or cytology; however, if the liver damage appears to be malignant and is considered resectable, diagnosis is made postoperatively, as in this case. Histopathological diagnosis shows four types of leiomyosarcomas: well differentiated, moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated and myxoid leiomyosarcoma (26). In this case, the patient was classified as type 1, since immunohistochemical study showed positive desmin and SMA, but negative S-100, CD117 and NSE (18,19), which is consistent with the parameters of this type of tumor and confirms PHL diagnosis.

As this was a large liver mass that generated large compression of neighboring structures and dyspnea, as well as peripheral vascularization, the possibility of image-guided percutaneous biopsy was discarded due to high risk of bleeding. Regulated or atypical hepatectomy with safety margins was the selected treatment. However, and due to the advanced evolutionary stage of the disease at diagnosis, enucleation followed by chemotherapy was an alternative treatment, which can also be used in metastases cases (8); for this patient, this was the best option a priori, thus constituting an exceptional case with apparent absence of metastasis and free surgical margins.

Since this is the only treatment that allows prolonged survival expectations, its analysis reveals the main favorable prognostic factors: being younger than 50 years of age, early diagnosis with a size below 5 cm, tumor location, radical surgery with safety margins, adjuvant treatment with chemotherapy and, as a last resort, liver transplantation (9). King et al. (27) describe cases with large tumors, which after five years had a survival rate of 18%, as well as cases with about 80% of survival at five years in the presence smaller tumors with clear margins. Also, Gates et al. (28) indicate that the combination of surgery with chemotherapy offers a median survival of 3.3 years.

PHL can present hematogenous metastases, mainly in the lung, followed by lymphatic and peritoneal paths. In this regard, Shivathirthan et al. (29) describe that the intermediate range in the identification of metastases between primary leiomyosarcoma and PHL was 29 months (range: 6-58 months). They also note that inoperability criteria may include extrahepatic spread of tumor, diffuse intrahepatic tumor and impaired liver function (29).

The patient in this case has received three cycles of chemotherapy with ifosfamide and doxorubicin; he has also attended monthly clinical, laboratory and imaging follow-ups. However, the role of adjuvant therapy with chemotherapy/radiotherapy is not well defined yet because, despite the fact that chemotherapy with doxorubicin and ifosfamide shows a slow course of the disease and may prolong survival in resections with R1 stage, there is not sufficient evidence in unresectable tumors and metastases by PHL (30).

The role of liver transplantation is still controversial, since it has low rates of survival and recurrence 95% before six months (31).

ConclusionS

PHL is an extremely rare tumor that, in most cases, is diagnosed in advanced stages, delaying treatment and worsening prognosis. Its finding should be suspected in patients with large tumor masses. However, despite having many advanced imaging studies, diagnosis is completely histopathological, whereas treatment is surgical, in most cases, depending on several factors. This case highlights surgical therapy and the rare diagnosis of this tumor.

Funding

None declared by the authors.

Conflicts of interest

None stated by the authors.

References

1.Ferrozzi F, Bova D, Zangrandi A, Garlaschi G. Primary liver leiomyosarcoma: CT appearance. Abdom Imaging. 1996;21(2):157-60. http://doi.org/cbnmww.

2.Soyer P, Blanc F, Vissuzaine C, Marmuse JP, Menu Y. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the liver MR findings. Clin Imaging. 1996;20(4):273-5. http://doi.org/d59c7d.

3.Del Carmen Binda M. Editorial de contenido. Rev Argent Radiol. 2014;78(1):3-4. http://doi.org/bt9z.

4.Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. Primary liver cancer in Japan: Sixth report. Cancer. 1987;60(6):1400-11. http://doi.org/cvxkns.

5.Cioffi U, Quattrone P, De Simone M, Bonavina L, Segalin A, Masini T, et al. Primary multiple epithelioid leiomyosarcoma of the liver. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43(12):1603-5.

6.Civardi G, Cavanna L, Iovine E, Buscarini E, Vallisa D, Buscarini L. Diagnostic imaging of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: a case report. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1996;28(2):98–101.

7.Chi M, Dudek AZ, Wind KP. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in adults: analysis of prognostic factors. Onkologie. 2012;35(4):210-4. http://doi.org/bt92.

8.Smith MB, Silverman JF, Raab SS, Towell BD, Geisinger KR. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of hepatic leiomyosarcoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;11(4):321-7. http://doi.org/dx4gk9.

9.Sprogøe-Jakobsen S, Hølund B. Immunohistochemistry (Ki-67 and p53) as a tool in determining malignancy in smooth muscle neoplasms (exemplified by a myxoid leiomyosarcoma of the uterus). APMIS. 1996;104(10):705-8. http://doi.org/dgvwjf.

10.Reichel C, Fehske W, Fischer HP, Hartlapp JH. Undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver in an adult patient with metastasis of the heart and brain. Clin Investig. 1994;72(3):209-12. http://doi.org/bqtws7.

11.Holloway H, Walsh CB, Thomas R, Fielding J. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma. J Clin Gastroenterol.1996;23(2):131-3. http://doi.org/b4277c.

12.Brichard B, Smets F, Sokal E, Clapuyt P, Vermylen C, Cornu G, et al. Unusual evolution of an Epstein-Barr virus-associated leiomyosarcoma occurring after liver transplantation. Pediatr Trasplant. 2001;5(5):365-9. doi:. http://doi.org/cphh9w.

13.Jyh-Wei C, Gin-Ho L, Kwok-Hung L, Hung-Tai C, Huay-Ben P, Hui-Hwa T. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the liver: report of a case. Gastroenterol-Taiwan. 1995;12:316-21.

14.Forbes A, Portmann B, Johnson P, Williams R. Hepatic sarcomas in adults: a review of 25 cases. Gut. 1987;28(6):668-74. http://doi.org/c55rhc.

15.Zornig C, Kremer B, Henne-Bruns D, Weh HJ, Schröder S, Brölsch CE. Primary sarcoma of the liver in the adult. Report of five surgically treated patients. Hepatogastroenteroly. 1992;39(4):319-21.

16.Moreno A, Vicente M, Del Pozo M, Sola J, Jiménez A. Sarcoma indiferenciado de hígado: a propósito de un caso con diagnóstico preoperatorio. Cir Esp. 1995;58:68-70.

17.Miettinen M, Kahlos T. Undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver. Epithelial features as shown by inmunohistochemical analysis and electron microscopic examination. Cancer. 1989;64(10):2096-103. http://doi.org/fbtcnz.

18.Fujita H, Kiriyama M, Kawamura T, Ii T, Takegawa S, Dohba S, et al. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in a woman after renal transplantation: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32(5):446-9. http://doi.org/dst86c.

19.Pinson CW, Lopez RR, Ivancev K, Ireland K, Sawyers JL. Resection of primary hepatic malignanant fibrous histiocytoma, fibrosarcoma and leiomyosarcoma. South Med J. 1994;87(3):384-91. http://doi.org/dnffr8.

20.Botella MT, Cabrera T, Sebastián JJ, Navarro MJ, Álvarez R, Uribarrena R. Hemangioendotelioma epiteloide hepático: un raro tumor hepático. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1995;87(10):749-51.

21.Marín R, Cabello A, Bondía JA, Moreno FJ, Ribeiro M, Fernández JL, et al. Seudotumor inflamatorio de hígado: presentación de un nuevo caso. Cir Esp. 1997;62:253-4.

22.Martínez Isla A, Ferrara A, Badia JM, Holloway I, Tanaka H, Riaz A, et al. Hepatocarcinoma fibrolamelar: resultados de la resección hepática parcial. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1997;89(9):699-705.

23.Aller R, Moreira V, Bermejo F, Sanromán AL, de Luis DA. Leiomiosarcoma de vena cava inferior: Aproximación diagnóstica y terapéutica. Rev Esp Enf Digest. 1997;89(9):706-10.

24.Das Gupta TK, Patel MK, Chaudhuri PK, Briele HA. The role of chemotherapy as an adjuvant to surgery in the initial treatment of primary soft tissue sarcomas in adults. J Surg Oncol. 1982;19(3):139-44.

25.Alrenga DP. Primary fibrosarcoma of the liver. Case report and review of the literature. Cancer. 1975;36(2):446-9. http://doi.org/b2mng4.

26.Higuchi T, Kikuchi M, Yamada Y. Rapidly growing hepatic leiomyosarcoma: an immunohistochemical evaluation of malignant potential with monoclonal antibody MIB-1. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89(11):2098-9.

27.King ME, Dickersin GR, Scully RE. Myxoid leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. A report of six cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6(7):589–98.

28.Gates LK, Cameron AJ, Nagorney DM, Goellner JR, Farley DR. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the liver mimicking liver abscess. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(4):649-52.

29.Shivathirthan N, Kita J, Iso Y, Hachiya H, Kyunghwa P, Sawada T, et al. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: Case report and literature review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;3(10):148-52. http://doi.org/dzqsj2.

30.Oosten AW, Seynaeve C, Schmitz PI, den Bakker MA, Verweij J, Sleijfer S. Outcomes of first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced or metastatic leiomyosarcoma of uterine and non-uterine origin. Sarcoma. 2009;2009: 348910. http://doi.org/cbmrhh.

31.Husted TL, Neff G, Thomas MJ, Gross TG, Woodle ES, Buell JF. Liver transplantation for primary or metastatic sarcoma to the liver. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(2):392-7.

Leiomiosarcoma hepático primario. Reporte de un caso.

Palabras clave: Leiomiosarcoma; Sarcoma; Neoplasias hepáticas; Hepatectomía; Actina de músculo liso.

Jhon Mauricio Coronel Ruilova

Residente de Cirugía General

Hospital Luis Vernaza

Guayaquil – Ecuador

José Enrique Zúñiga Bohórquez

Médico, Sala San Miguel – Hospital Luis Vernaza.

Jefe, Servicio de Transplante Hepático – Hospital Luis Vernaza

Médico, Sala San Aurelio – Hospital Luis Vernaza

Guayaquil – Ecuador

Lincoln Alexander Cabezas Barragán

Jefe, Servicio de Transporte Hepático – Hospital Luis Vernaza

Profesor, Universidad de Especialidades Espíritu

Santo de Guayaquil

Médico, Sala San Aurelio – Hospital Luis Vernaza

Guayaquil – Ecuador

RESUMEN

El leiomiosarcoma hepático primario es un tumor extremadamente raro entre los casos de tumores hepáticos en adultos, presentando una incidencia de 0.1 y 1%. En este artículo se presenta el caso de un hombre de 55 años con cuadro clínico de cinco meses de evolución que consiste en dolor abdominal, presencia de masa dura, no móvil, de gran tamaño, pérdida de peso, disnea y fiebre.

La tomografía axial computarizada (TAC) trifásica mostró masa hipercaptante en su periferia durante fase arterial hipodensa en su centro, localizada en segmentos VII y VIII, sin plano de separación del hígado. Debido a su sintomatología, el paciente fue intervenido quirúrgicamente por laparatomía exploratoria, hallándose masa cerebroide de 40 x 40cm, razón por la cual se practicó una tumorectomía sin hepatectomía, dejando bordes quirúrgicos libres.

El diagnóstico se realizó, en gran parte, mediante evaluación histopatológica, observándose estroma con formas multinucleadas pleomórficas, desmina (+), SMA (actina de musculo liso) y MSA (actina músculo específica) (+), Ki67 (+) y negativo para S100 (proteína S100) y anticuerpo CD117, lo que confirmó el diagnóstico de leiomiosarcoma pleomórfico de alto grado. Una vez presentó una notoria mejoría, el paciente fue dado de alta a los 16 días de su ingreso y fue derivado al servicio de oncología para su adyuvancia con quimioterapia.

Dado el tamaño de la masa encontrada, el pronóstico fue poco alentador, lo que hizo que el tratamiento quirúrgico fuera la única opción que ofreciera expectativas de supervivencia mediante hepatectomías regladas o “atípicas” con márgenes de seguridad e incluso trasplante hepático. Teniendo en cuenta lo anterior, se optó por la primera opción; tras seis meses de la cirugía, observándose mejoría clínica, además del tratamiento adyuvante, el paciente, aún con pronóstico desfavorable, permanecía estable, asistiendo a controles bajo manejo médico multidisciplinario.

Introducción

El leiomiosarcoma hepático primario (LHP) es un tumor extremadamente raro. Para 2011, se habían reportado en la literatura inglesa menos de 50 pacientes con este tipo de tumor (1,2). En el contexto de este estudio, es importante decir que, a la fecha, no existen reportes de casos similares en Ecuador y que, para 2014, eran muy pocos los casos reportados en América Latina (3).

En población adulta, los sarcomas hepáticos primarios constituyen un grupo de tumores excepcionales, representando entre 0.1 y 1% de todos los tumores hepáticos malignos existentes en esta población (4). Por lo general, estos se desarrollan en el útero, el retroperitoneo, los órganos genitales, los pulmones, en el hígado y en los grandes vasos (5); por su parte, el LHP surge a partir de las células musculares lisas de las estructuras vasculares intrahepáticas, de los conductos biliares o del ligamento redondo (6).

Su rareza, sus manifestaciones de imagen y su presentación clínica no específica dificultan un diagnóstico temprano (7). En la actualidad, su diagnóstico puede realizarse antes de operar, mediante citología o biopsia percutánea guiada por imagen, o después de operar (8-12). Sin embargo, algunas veces el diagnóstico diferencial entre sarcoma hepático primitivo o metastásico puede presentar dificultades (9), razón por la que el estudio anatomopatológico es fundamental. El diagnóstico histopatológico se caracteriza por la presencia de infiltrados difusos y uniformes en las células en forma de huso con núcleos hipercromáticos (8,9), mientras que en inmunohistoquímica se observa reacción positiva para desmina, SMA, MSA, Ki67 y negativo para S100 y CD117.

La cirugía resectiva es la mejor opción de tratamiento de esta condición; en esta se deben mantener los mismos principios quirúrgicos preconizados en la cirugía de sarcomas de partes blandas, siendo las resecciones hepáticas con márgenes oncológicos la elección más apropiada o el gold standard. No obstante, y debido al avanzado estado de la enfermedad al momento de su diagnóstico, la tumorectomía o enucleación seguida de tratamiento con quimioterapia coadyuvante puede ser otra opción terapéutica a tenerse en cuenta, incluso en casos con metástasis (10), lo que deja al trasplante hepático como última opción.

Caso clínicO

Paciente masculino de 55 años de edad, profesional con labores de oficina sin antecedentes médicos de importancia, quien niega consumir o haber consumido alcohol y tabaco y reporta antecedentes familiares de diabetes mellitus, cáncer de esófago y melanoma ocular. Presenta cuadro clínico de cinco meses de evolución caracterizado por dolor abdominal, de tipo opresivo y de moderada intensidad, localizado en hipocondrio derecho y mesogastrio, acompañado de masa abdominal dura, no móvil, de aproximadamente 20cm de diámetro, dolorosa a palpación (ver Figura 1), hiporexia y pérdida de peso, aproximadamente 45 libras en 100 días, disnea de medianos esfuerzos y fiebre vespertina de un mes de evolución previo a ingreso hospitalario. Con signos vitales estables.

Fig 1. Morfología del paciente. Masa tumoral de gran tamaño en hemiabdomen derecho.

Fuente: Imagen obtenida durante la realización del estudio.

A través de los exámenes de laboratorio se observa anemia leve normocítica hipocrómica Hb: 10,1mg/dl, pruebas de función hepática y colestásicas normales, tiempos de coagulación normales y reactantes de fase aguda sin alteraciones. También se obtienen resultados normales de marcadores tumorales como CAE, alfafetoproteína, CA 125, CA 15-3, CA 19-9 y CA 72-4. La ecografía de abdomen muestra masa tumoral en parte inferior del hígado de aproximadamente 30 x 20cm, hipoecoica y vascularizada (ver Figura 2). Por otra parte, la radiografía simple de abdomen permite observar imagen radiopaca en hipocondrio y flanco derechos. La angio-tomografía de abdomen trifásica muestra masa hipercaptante en su periferia, centro hipodenso en fase arterial heterogénea en fase portal y tardía, localizada en segmentos hepáticos V y VI, sin plano de separación del hígado más adenomegalias retroperitoneales (ver Figura 3).

Fig 2. Ecografía de abdomen 2D. Masa hepática de gran tamaño, hipoecogénica, con vascularización.

Fuente: Imagen obtenida durante la realización del estudio.

Fig 3. Angio-tomografía trifásica. Masa tumoral de gran tamaño en lóbulo hepático derecho, segmentos V y VI, que desplaza órganos intraabdominales.

Fuente: Imagen obtenida durante la realización del estudio.

Finalmente, mediante colonoscopía se observó mucosa de aspecto normal y disminución de luz a nivel de colon ascendente por aparente compresión extrínseca. Se practicó laparotomía exploratoria para mejorar el cuadro clínico del paciente, encontrando lo siguiente:: tumoración tipo cerebroide de gran tamaño en lecho hepático, segmentos V y VI, de aproximadamente 40x40cm, encapsulada, que desplazaba diafragma derecho y estructuras abdominales vecinas, por lo que se realizó tumorectomía sin hepatectomía, con bordes quirúrgicos libres en muestra por congelación; además, se liberaron estructuras vecinas y no se identificaron masas, ganglios o siembras metastásicas a simple vista. No se presentaron complicaciones quirúrgicas intraoperatorias (ver Figura 4).

Fig 4. Visualización, durante laparotomía exploratoria, de leiomiosarcoma hepático primario, multilobulado, tipo cerebroide, encapsulado, localizado en lóbulo hepático derecho.

Fuente: Imagen obtenida durante la realización del estudio.

El estudio anatomopatológico (ver Figura 5) reportó tumor maligno multilobulado con las siguientes características: peso, 4341 g; tamaño, 38 x 35 x 20cm; encapsulado, con bordes irregulares y cavitados; de estirpe mesenquimal compuesto por células fusiformes; con núcleo alargado; cromatina en grumos, y numerosas mitosis. Por su parte, el estudio inmunohistoquímico evidenció: desmina positivo, SMA y MSA positivos, Ki67 positivo en 80% de las células y negativo para S100 y CD117, lo que confirmó diagnóstico de leiomiosarcoma pleomórfico de alto grado.

Fig 5. Estudio histológico e inmunohistoquímico. 5.a. Se observan células malignas musculares fusiformes de núcleo alargado, con zonas de necrosis, las cuales son típicas en esta clase de tumor. (Tinción con hematoxilina-eosina x100). 5.b. Presencia de: numerosas mitosis, fascículos entrelazados y citoplasma rosado con numerosas formas multinucleadas pleomórficas. (Tinción con H&E x400).

5.c. Inmunohistoquímica muestra desmina positivo con presencia de células típicas de músculo liso. (Magnificación original: x50).

Fuente: Imagen obtenida durante la realización del estudio.

El paciente estuvo hospitalizado 16 días; luego de mostrar una evolución favorable, fue dado de alta y se ordenó control mensual por consulta externa. Asimismo, fue derivado al servicio de oncología para iniciar tratamiento adyuvante con quimioterapia cada 25 días por tres ciclos, observando su evolución clínica y ajustándose a su requerimiento con posibilidad de radioterapia posterior a control de parámetros clínicos, imagenológicos y de laboratorio, al cual se está a la espera en la actualidad. Luego de seis meses de postoperatorio, aún con pronóstico desfavorable, permanece estable, atendiendo a controles bajo manejo médico multidisciplinario.

DiscusióN

Las manifestaciones clínicas de LHP no son específicas y, por lo general, los tumores son asintomáticos antes de su aumento de tamaño (11,12). La edad promedio de presentación está entre los 40 y 50 años, con edades extremas de 22 y 77 años (13). El síntoma más frecuente es dolor, de pequeña a mediana intensidad, en hemiabdomen superior, acompañado de pérdida ponderal, febrícula vespertina y astenia (14). Mediante exploración clínica es posible identificar hepatomegalia o masa abdominal palpable en hipocondrio derecho-epigastrio. Por lo general, se describen elevaciones inespecíficas de algún parámetro bioquímico de función/daño hepático: bilirrubina, fosfatasa alcalina o transaminasas, mas no de marcadores tumorales específicos, como ocurrió en el caso aquí reportado, algo que sí si sucede en sarcomas presentes en otras partes del cuerpo.

Por su parte, el diagnóstico por imagen no aporta datos específicos (16,17), pues a través de ecografía se evidencia como una tumoración hepática hipoecoica, mientras que en TAC trifásica, como masa heterogénea bien definida, hipodensa o isodensa por áreas centrales de necrosis y con realce periférico, o como masa quística con pared gruesa (18) y con patrón angiográfico de masa avascular o importante neovascularización periférica patológica (19), superponible a cualquier tumor hepático. Finalmente, mediante resonancia magnética nuclear se observa un área heterogénea con lesión hipointensa en T1 e hiperintensa en T2 con posible encapsulación (2).

La localización más frecuente del tumor se da en lóbulo derecho y es común que a la hora de realizar el diagnóstico se encuentre metástasis en alrededor del 40% (6), lo que concuerda con los datos reportados aquí. Por tanto, el diagnóstico diferencial debe establecerse entre diversos tipos de tumores sólidos hepáticos benignos (20,21) y malignos, tales como hepatocarcinomas de diferente estirpe (22), sarcoma primitivo o metastásico (8) e incluso sarcomas de la vena cava retrohepática (23).

En la actualidad y En la mayoría de series de casos (20,24,25), el diagnóstico de sarcoma hepático puede establecerse preoperatoriamente, mediante citología o biopsia percutánea guiada por imagen; sin embargo, si la lesión hepática aparenta malignidad y se considera resecable su diagnóstico se realiza postoperatoriamente, tal como ocurrió en este caso. El diagnóstico histopatológico muestra cuatro tipos de leiomiosarcomas: 1, 2, 3 y 4, los cuales se definen como bien diferenciado, moderadamente diferenciado, pobremente diferenciado y leiomiosarcoma mixoide, respectivamente (26). En el presente caso el paciente fue clasificado en el tipo 1, pues el estudio inmunohistoquímico evidenció desmina y SMA Positivos, pero negativo para S-100, CD117 y NSE (18,19), lo que concuerda con los parámetros de esta tipología y confirmando así así el diagnóstico de LHP.

Al ser una masa hepática de gran tamaño que genera dificultad respiratoria por compresión a estructuras vecinas y que presenta una nutrida vascularización periférica, la posibilidad de toma percutánea guiada por imagen es descartada debido al alto riesgo de sangrado. Las hepatectomías regladas o atípicas con márgenes de seguridad son el tratamiento de elección, no obstante, y debido al avanzado estado evolutivo de la enfermedad al momento de su diagnóstico, la enucleación seguida de tratamiento quimioterapéutico es otra opción terapéutica, incluso en casos con metástasis (8), la cual, en el presente caso, fue a priori la mejor opción, siendo un caso excepcional con aparente ausencia de metástasis y bordes quirúrgicos libres.

Al ser este el único tratamiento que permite expectativas de sobrevivencia prolongada, su análisis revela los principales factores pronósticos favorables: edad inferior a 50 años, diagnóstico precoz con tamaño inferior a 5 cm, localización del tumor, cirugía radical con márgenes de seguridad, tratamiento adyuvante con quimioterapia y, como última opción, trasplante hepático (9). En un estudio, King et al. (27) describen casos con grandes tumores que luego de cinco años presentaban una tasa de supervivencia del 18%, así como casos con cerca de 80% tumores pequeños con márgenes libres. Por su parte, Gates et al. (28) señalan que la combinación de cirugía con quimioterapia ofrece una supervivencia media de 3.3 años.

Los LHP pueden presentar metástasis principalmente vía hematógena hacia el pulmón, seguido de vía linfática y peritoneal. Al respecto, Shivathirthan et al. (29) describen que el rango intermedio en la identificación de metástasis entre leiomiosarcoma primario y LHP fue de 29 meses (rango: 6-58 meses). Además, señalan que los criterios de inoperabilidad pueden incluir: propagación extrahepática del tumor, tumor intrahepático difuso y función hepática deteriorada (29).

El paciente del presente caso ha recibido 3 ciclos de quimioterapia con ifosfamida + doxorubicina; igualmente, ha asistido a controles mensuales clínicos, de laboratorio y de imagenología. Sin embargo, el rol de la adyuvancia con quimioterapia/radioterapia no está bien definido, pues a pesar de que la quimioterapia en forma de doxorubicina e ifosfamida muestra un curso lento de la enfermedad y puede prolongar la supervivencia en resecciones con estadio R1, n hay suficiente evidencia en tumores irresecables y en metástasis por LHP (30).

El rol del trasplante hepático aún es controversial, pues tiene porcentajes bajos de supervivencia y recurrencias del 95% antes de los seis meses (31).

ConclusioneS

El LHP es un tumor extremadamente raro que, en la mayoría de los casos, se diagnostica en estadios avanzados, lo que retrasa su tratamiento y empeora su pronóstico. Su hallazgo debe ser sospechado en pacientes con masas tumorales de gran tamaño. Ahora bien, a pesar de contar con gran cantidad de estudios avanzados de imagen, su diagnóstico es totalmente histopatológico, mientras que su tratamiento, quirúrgico, en la mayoría de los casos y dependiendo de varios factores. Este caso destaca la terapia quirúrgica y el diagnóstico de este tumor tan poco frecuente.

Financiación

Ninguna declarada por los autores.

Conflicto de intereses

Ninguno declarado por los autores.

Referencias

1.Ferrozzi F, Bova D, Zangrandi A, Garlaschi G. Primary liver leiomyosarcoma: CT appearance. Abdom Imaging. 1996;21(2):157-60. http://doi.org/cbnmww.

2.Soyer P, Blanc F, Vissuzaine C, Marmuse JP, Menu Y. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the liver MR findings. Clin Imaging. 1996;20(4):273-5. http://doi.org/d59c7d.

3.Del Carmen Binda M. Editorial de contenido. Rev Argent Radiol. 2014;78(1):3-4. http://doi.org/bt9z.

4.Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. Primary liver cancer in Japan: Sixth report. Cancer. 1987;60(6):1400-11. http://doi.org/cvxkns.

5.Cioffi U, Quattrone P, De Simone M, Bonavina L, Segalin A, Masini T, et al. Primary multiple epithelioid leiomyosarcoma of the liver. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43(12):1603-5.

6.Civardi G, Cavanna L, Iovine E, Buscarini E, Vallisa D, Buscarini L. Diagnostic imaging of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: a case report. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1996;28(2):98–101.

7.Chi M, Dudek AZ, Wind KP. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in adults: analysis of prognostic factors. Onkologie. 2012;35(4):210-4. http://doi.org/bt92.

8.Smith MB, Silverman JF, Raab SS, Towell BD, Geisinger KR. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of hepatic leiomyosarcoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;11(4):321-7. http://doi.org/dx4gk9.

9.Sprogøe-Jakobsen S, Hølund B. Immunohistochemistry (Ki-67 and p53) as a tool in determining malignancy in smooth muscle neoplasms (exemplified by a myxoid leiomyosarcoma of the uterus). APMIS. 1996;104(10):705-8. http://doi.org/dgvwjf.

10.Reichel C, Fehske W, Fischer HP, Hartlapp JH. Undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver in an adult patient with metastasis of the heart and brain. Clin Investig. 1994;72(3):209-12. http://doi.org/bqtws7.

11.Holloway H, Walsh CB, Thomas R, Fielding J. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma. J Clin Gastroenterol.1996;23(2):131-3. http://doi.org/b4277c.

12.Brichard B, Smets F, Sokal E, Clapuyt P, Vermylen C, Cornu G, et al. Unusual evolution of an Epstein-Barr virus-associated leiomyosarcoma occurring after liver transplantation. Pediatr Trasplant. 2001;5(5):365-9. doi:. http://doi.org/cphh9w.

13.Jyh-Wei C, Gin-Ho L, Kwok-Hung L, Hung-Tai C, Huay-Ben P, Hui-Hwa T. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the liver: report of a case. Gastroenterol-Taiwan. 1995;12:316-21.

14.Forbes A, Portmann B, Johnson P, Williams R. Hepatic sarcomas in adults: a review of 25 cases. Gut. 1987;28(6):668-74. http://doi.org/c55rhc.

15.Zornig C, Kremer B, Henne-Bruns D, Weh HJ, Schröder S, Brölsch CE. Primary sarcoma of the liver in the adult. Report of five surgically treated patients. Hepatogastroenteroly. 1992;39(4):319-21.

16.Moreno A, Vicente M, Del Pozo M, Sola J, Jiménez A. Sarcoma indiferenciado de hígado: a propósito de un caso con diagnóstico preoperatorio. Cir Esp. 1995;58:68-70.

17.Miettinen M, Kahlos T. Undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver. Epithelial features as shown by inmunohistochemical analysis and electron microscopic examination. Cancer. 1989;64(10):2096-103. http://doi.org/fbtcnz.

18.Fujita H, Kiriyama M, Kawamura T, Ii T, Takegawa S, Dohba S, et al. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in a woman after renal transplantation: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32(5):446-9. http://doi.org/dst86c.

19.Pinson CW, Lopez RR, Ivancev K, Ireland K, Sawyers JL. Resection of primary hepatic malignanant fibrous histiocytoma, fibrosarcoma and leiomyosarcoma. South Med J. 1994;87(3):384-91. http://doi.org/dnffr8.

20.Botella MT, Cabrera T, Sebastián JJ, Navarro MJ, Álvarez R, Uribarrena R. Hemangioendotelioma epiteloide hepático: un raro tumor hepático. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1995;87(10):749-51.

21.Marín R, Cabello A, Bondía JA, Moreno FJ, Ribeiro M, Fernández JL, et al. Seudotumor inflamatorio de hígado: presentación de un nuevo caso. Cir Esp. 1997;62:253-4.

22.Martínez Isla A, Ferrara A, Badia JM, Holloway I, Tanaka H, Riaz A, et al. Hepatocarcinoma fibrolamelar: resultados de la resección hepática parcial. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1997;89(9):699-705.

23.Aller R, Moreira V, Bermejo F, Sanromán AL, de Luis DA. Leiomiosarcoma de vena cava inferior: Aproximación diagnóstica y terapéutica. Rev Esp Enf Digest. 1997;89(9):706-10.

24.Das Gupta TK, Patel MK, Chaudhuri PK, Briele HA. The role of chemotherapy as an adjuvant to surgery in the initial treatment of primary soft tissue sarcomas in adults. J Surg Oncol. 1982;19(3):139-44.

25.Alrenga DP. Primary fibrosarcoma of the liver. Case report and review of the literature. Cancer. 1975;36(2):446-9. http://doi.org/b2mng4.

26.Higuchi T, Kikuchi M, Yamada Y. Rapidly growing hepatic leiomyosarcoma: an immunohistochemical evaluation of malignant potential with monoclonal antibody MIB-1. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89(11):2098-9.

27.King ME, Dickersin GR, Scully RE. Myxoid leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. A report of six cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6(7):589–98.

28.Gates LK, Cameron AJ, Nagorney DM, Goellner JR, Farley DR. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the liver mimicking liver abscess. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(4):649-52.

29.Shivathirthan N, Kita J, Iso Y, Hachiya H, Kyunghwa P, Sawada T, et al. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: Case report and literature review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;3(10):148-52. http://doi.org/dzqsj2.

30.Oosten AW, Seynaeve C, Schmitz PI, den Bakker MA, Verweij J, Sleijfer S. Outcomes of first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced or metastatic leiomyosarcoma of uterine and non-uterine origin. Sarcoma. 2009;2009: 348910. http://doi.org/cbmrhh.

31.Husted TL, Neff G, Thomas MJ, Gross TG, Woodle ES, Buell JF. Liver transplantation for primary or metastatic sarcoma to the liver. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(2):392-7.

Referencias

Ferrozzi F, Bova D, Zangrandi A, Garlaschi G. Primary liver leiomyosarcoma: CT appearance. Abdom Imaging. 1996;21(2):157-60. http://doi.org/cbnmww

(2) Soyer P, Blanc F, Vissuzaine C, Marmuse JP, Menu Y. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the liver MR findings. Clin Imaging. 1996;20(4):273-5. http://doi.org/d59c7d

(3) Del Carmen Binda M. Editorial de contenido. Rev Argent Radiol. 2014;78(1):3-4. http://doi.org/bt9z

(4) Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. Primary liver cancer in Japan: Sixth report. Cancer. 1987;60(6):1400-11. http://doi.org/cvxkns

(5) Cioffi U, Quattrone P, De Simone M, Bonavina L, Segalin A, Masini T, et al. Primary multiple epithelioid leiomyosarcoma of the liver. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43(12):1603-5

(6) Civardi G, Cavanna L, Iovine E, Buscarini E, Vallisa D, Buscarini L. Diagnostic imaging of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: a case report. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1996;28(2):98–101

(7) Chi M, Dudek AZ, Wind KP. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in adults: analysis of prognostic factors. Onkologie. 2012;35(4):210-4. http://doi.org/bt92

(8) Smith MB, Silverman JF, Raab SS, Towell BD, Geisinger KR. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of hepatic leiomyosarcoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;11(4):321-7. http://doi.org/dx4gk9

(9) Sprogøe-Jakobsen S, Hølund B. Immunohistochemistry (Ki-67 and p53) as a tool in determining malignancy in smooth muscle neoplasms (exemplified by a myxoid leiomyosarcoma of the uterus). APMIS. 1996;104(10):705-8. http://doi.org/dgvwjf

(10) Reichel C, Fehske W, Fischer HP, Hartlapp JH. Undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver in an adult patient with metastasis of the heart and brain. Clin Investig. 1994;72(3):209-12. http://doi.org/bqtws7

(11) Holloway H, Walsh CB, Thomas R, Fielding J. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma. J Clin Gastroenterol.1996;23(2):131-3. http://doi.org/b4277c

(12) Brichard B, Smets F, Sokal E, Clapuyt P, Vermylen C, Cornu G, et al. Unusual evolution of an Epstein-Barr virus-associated leiomyosarcoma occurring after liver transplantation. Pediatr Trasplant. 2001;5(5):365-9. doi:. http://doi.org/cphh9w

(13) Jyh-Wei C, Gin-Ho L, Kwok-Hung L, Hung-Tai C, Huay-Ben P, Hui-Hwa T. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the liver: report of a case. Gastroenterol-Taiwan. 1995;12:316-21

(14) Forbes A, Portmann B, Johnson P, Williams R. Hepatic sarcomas in adults: a review of 25 cases. Gut. 1987;28(6):668-74. http://doi.org/c55rhc

(15) Zornig C, Kremer B, Henne-Bruns D, Weh HJ, Schröder S, Brölsch CE. Primary sarcoma of the liver in the adult. Report of five surgically treated patients. Hepatogastroenteroly. 1992;39(4):319-21

(16) Moreno A, Vicente M, Del Pozo M, Sola J, Jiménez A. Sarcoma indiferenciado de hígado: a propósito de un caso con diagnóstico preoperatorio. Cir Esp. 1995;58:68-70

(17) Miettinen M, Kahlos T. Undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver. Epithelial features as shown by inmunohistochemical analysis and electron microscopic examination. Cancer. 1989;64(10):2096-103. http://doi.org/fbtcnz

(18) Fujita H, Kiriyama M, Kawamura T, Ii T, Takegawa S, Dohba S, et al. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in a woman after renal transplantation: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32(5):446-9. http://doi.org/dst86c

(19) Pinson CW, Lopez RR, Ivancev K, Ireland K, Sawyers JL. Resection of primary hepatic malignanant fibrous histiocytoma, fibrosarcoma and leiomyosarcoma. South Med J. 1994;87(3):384-91. http://doi.org/dnffr8

(20) Botella MT, Cabrera T, Sebastián JJ, Navarro MJ, Álvarez R, Uribarrena R. Hemangioendotelioma epiteloide hepático: un raro tumor hepático. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1995;87(10):749-51

(21) Marín R, Cabello A, Bondía JA, Moreno FJ, Ribeiro M, Fernández JL, et al. Seudotumor inflamatorio de hígado: presentación de un nuevo caso. Cir Esp. 1997;62:253-4

(22) Martínez Isla A, Ferrara A, Badia JM, Holloway I, Tanaka H, Riaz A, et al. Hepatocarcinoma fibrolamelar: resultados de la resección hepática parcial. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1997;89(9):699-705

(23) Aller R, Moreira V, Bermejo F, Sanromán AL, de Luis DA. Leiomiosarcoma de vena cava inferior: Aproximación diagnóstica y terapéutica. Rev Esp Enf Digest. 1997;89(9):706-10

(24) Das Gupta TK, Patel MK, Chaudhuri PK, Briele HA. The role of chemotherapy as an adjuvant to surgery in the initial treatment of primary soft tissue sarcomas in adults. J Surg Oncol. 1982;19(3):139-44

(25) Alrenga DP. Primary fibrosarcoma of the liver. Case report and review of the literature. Cancer. 1975;36(2):446-9. http://doi.org/b2mng4

(26) Higuchi T, Kikuchi M, Yamada Y. Rapidly growing hepatic leiomyosarcoma: an immunohistochemical evaluation of malignant potential with monoclonal antibody MIB-1. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89(11):2098-9

(27) King ME, Dickersin GR, Scully RE. Myxoid leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. A report of six cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6(7):589–98

(28) Gates LK, Cameron AJ, Nagorney DM, Goellner JR, Farley DR. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the liver mimicking liver abscess. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(4):649-52

(29) Shivathirthan N, Kita J, Iso Y, Hachiya H, Kyunghwa P, Sawada T, et al. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: Case report and literature review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;3(10):148-52. http://doi.org/dzqsj2

(30) Oosten AW, Seynaeve C, Schmitz PI, den Bakker MA, Verweij J, Sleijfer S. Outcomes of first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced or metastatic leiomyosarcoma of uterine and non-uterine origin. Sarcoma. 2009;2009: 348910. http://doi.org/cbmrhh

(31) Husted TL, Neff G, Thomas MJ, Gross TG, Woodle ES, Buell JF. Liver transplantation for primary or metastatic sarcoma to the liver. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(2):392-7

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Visitas a la página del resumen del artículo

Descargas

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2016 Case reports

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivadas 4.0.

Los autores al someter sus manuscritos conservarán sus derechos de autor. La revista tiene el derecho del uso, reproducción, transmisión, distribución y publicación en cualquier forma o medio. Los autores no podrán permitir o autorizar el uso de la contribución sin el consentimiento escrito de la revista.

El Formulario de Divulgación Uniforme para posibles Conflictos de Interés y los oficios de cesión de derechos y de responsabilidad deben ser entregados junto con el original.

Aquellos autores/as que tengan publicaciones con esta revista, aceptan los términos siguientes:

Los autores/as conservarán sus derechos de autor y garantizarán a la revista el derecho de primera publicación de su obra, el cual estará simultáneamente sujeto a la Licencia de reconocimiento de Creative Commons 4.0 que permite a terceros compartir la obra siempre que se indique su autor y su primera publicación en esta revista.

Los autores/as podrán adoptar otros acuerdos de licencia no exclusiva de distribución de la versión de la obra publicada (p. ej.: depositarla en un archivo telemático institucional o publicarla en un volumen monográfico) siempre que se indique la publicación inicial en esta revista.

Se permite y recomienda a los autores/as difundir su obra a través de Internet (p. ej.: en archivos telemáticos institucionales o en su página web) antes y durante el proceso de envío, lo cual puede producir intercambios interesantes y aumentar las citas de la obra publicada. (Véase El efecto del acceso abierto).