Management Control in Inter-organizational Relationships: The Case of Franchises

CONTROL DE GESTIÓN EN LAS RELACIONES INTERORGANIZACIONALES: EL CASO DE LAS FRANQUICIAS

CONTROLE DE GESTÃO E RELAÇÕES INTERORGANIZACIONAIS: O CASO DAS FRANQUIAS

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/innovar.v25n58.52357Keywords:

Management control, franchising, business success, inter-organizational relationships, transaction costs, trust (en)Control de gestión, franquicia, éxito financiero, relaciones interorganizacionales, costos de transacción, confianza (es)

Controle de gestão, franquia, sucesso financeiro, relações interorganizacionais, custos de transação, confiança (pt)

Downloads

There is great interest in the role of management control on theoretical and practical developments within the field of Inter-organizational Relations. This research aims to contribute at verifying how relationships between firms affect the management control tools used, as illustrated in a specific case: the relationship between the franchisor and its franchisees, which has not received much attention to date. As indicated by previous research, case studies can be helpful to determine the factors affecting the type of management control tools that should be established to manage inter-firm relationships.

Results have found that the franchisor uses quantitative control mechanisms in order to avoid common types of opportunistic franchise behavior related to royalty payments and other financial requirements, as well as qualitative tools to assure the fulfilment of agreement-related conditions regarding knowhow, to resolve unexpected non-economic problems and to encourage personal relationship and trust. This study also provides an outline on franchisor-franchisee relationships in the model proposed by Van der Meer-Kooistra and Vosselman (2000). To test this model, the franchisor's perspective (outsourcer) has been taken into account as performed when building the model. Findings indicate that this relationship shows many similarities to the pattern based on bureaucracy and a few similarities to patterns based on trust.

En la actualidad existe un gran interés en torno a la influencia del control de gestión en el desarrollo teórico y práctico de las relaciones interorganizacionales. El presente estudio busca analizar el impacto de las relaciones entre firmas sobre las herramientas de control de gestión, tomando como ejemplo un caso específico: la relación entre el franquiciador y sus franquiciados, la cual, hasta la fecha, no ha recibido la debida atención (Van der Meer-Kooistra y Vosselman, 2006). Contribuciones anteriores señalan que los estudios de caso pueden ser útiles para determinar los factores que influyen en el tipo de herramientas de control de gestión que deben establecerse para un buen manejo de las relaciones entre firmas.

Estrategia y Organizaciones

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/innovar.v25n58.52357.

Management Control in Inter-organizational Relationships: The Case of Franchises1

CONTROL DE GESTIÓN EN LAS RELACIONES INTERORGANIZACIONALES: EL CASO DE LAS FRANQUICIAS

CONTROLE DE GESTÃO E RELAÇÕES INTERORGANIZACIONAIS: O CASO DAS FRANQUIAS

LE CONTRÔLE DE GESTION ET LES RELATIONS INTERORGANISATIONNELLES: LE CAS DES FRANCHISES

Magdalena Cordobés Madueño*, Pilar Soldevila García**

* Ph.D. en Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales, Universidad Loyola Andalucía, Córdoba, España. Correo electrónico: cordobes@uloyola.es

** Ph.D. en Dirección y Administración de Empresas, Universidad Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, España. Correo electrónico: psoldevila@bcn.cat

1 A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the First Catalan Accounting and Management Congress organized by ACCID.

Citación: Cordobés Madueño, M., & Soldevila García, P. (2015). Management Control in Inter-organizational Relationships: The Case of Franchises. Innovar, 25(58), 23-36. doi: 10.15446/innovar.v25n58.52357.

Clasificación JEL: M10, L25, D22.

Recibido: Junio 2012, Aprobado: Septiembre 2014.

ABSTRACT: There is great interest in the role of management control on theoretical and practical developments within the field of Inter-organizational Relations. This research aims to contribute at verifying how relationships between firms affect the management control tools used, as illustrated in a specific case: the relationship between the franchisor and its franchisees, which has not received much attention to date. As indicated by previous research, case studies can be helpful to determine the factors affecting the type of management control tools that should be established to manage inter-firm relationships.

Results have found that the franchisor uses quantitative control mechanisms in order to avoid common types of opportunistic franchise behavior related to royalty payments and other financial requirements, as well as qualitative tools to assure the fulfilment of agreement-related conditions regarding knowhow, to resolve unexpected non-economic problems and to encourage personal relationship and trust. This study also provides an outline on franchisor-franchisee relationships in the model proposed by Van der Meer-Kooistra and Vosselman (2000). To test this model, the franchisor's perspective (outsourcer) has been taken into account as performed when building the model. Findings indicate that this relationship shows many similarities to the pattern based on bureaucracy and a few similarities to patterns based on trust.

KEYWORDS: Management control, franchising, business success, inter-organizational relationships, transaction costs, trust.

RESUMEN: En la actualidad existe un gran interés en torno a la influencia del control de gestión en el desarrollo teórico y práctico de las relaciones interorganizacionales. El presente estudio busca analizar el impacto de las relaciones entre firmas sobre las herramientas de control de gestión, tomando como ejemplo un caso específico: la relación entre el franquiciador y sus franquiciados, la cual, hasta la fecha, no ha recibido la debida atención (Van der Meer-Kooistra y Vosselman, 2006). Contribuciones anteriores señalan que los estudios de caso pueden ser útiles para determinar los factores que influyen en el tipo de herramientas de control de gestión que deben establecerse para un buen manejo de las relaciones entre firmas.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Control de gestión, franquicia, éxito financiero, relaciones interorganizacionales, costos de transacción, confianza.

RESUMO: Na atualidade, existe um grande interesse na influência do controle de gestão no desenvolvimento teórico e prático das relações interorganizacionais. Este estudo busca analisar o impacto do relacionamento entre firmas sobre as ferramentas de controle de gestão e toma como exemplo o caso: o relacionamento entre o franqueador e seus franqueados, o qual, até o momento, não tem recebido a devida atenção (Van der Meer-Kooistra & Vosselman, 2006). Contribuições anteriores indicam que os estudos de caso podem ser úteis para determinar os fatores que influenciam no tipo de ferramentas de controle que devem ser estabelecidas para uma boa gestão das relações entre firmas.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Controle de gestão, franquia, sucesso financeiro, relações interorganizacionais, custos de transação, confiança.

RÉSUMÉ: Actuellement, il existe un vif intérêt sur l'influence du contrôle de gestion dans le développement théorique et pratique des relations interorganisationnelles. Cette étude vise à analyser l'impact des relations entre les entreprises sur les outils de contrôle de gestion, comme l'illustre un cas spécifique: la relation entre le franchiseur et ses franchisés, qui, à ce jour, n'a pas reçu l'attention qu'elle mérite (Van der Meer-Kooistra & Vosselman, 2006). Des contributions précédentes indiquent que les études de cas peuvent être utiles pour déterminer les facteurs qui influencent le type d'outils de contrôle de gestion qui doit être établi pour une bonne gestion des relations entre les entreprises.

MOTS-CLÉ: Contrôle de gestion, franchise, réussite financière, relations interorganisationnelles, coûts de transaction, confiance.

Introduction

The interest in analyzing the role played by management control in the relationship between firms stems from the observation of a reality: these companies maintain a relationship with other economic players in their environment (suppliers, distributors, competitors, complementary companies, public firms, etc.). Some of these relationships are crucial to the smooth operation, success, and the survival of the organizations involved (Williamson, 1975, 1981; Zaheer & Vankatraman, 1995; Borch & Arthur, 1991; Oliver, 1990). The more complex the relationships developed around key aspects of the business, the more necessary the need for control. Dekker (2004), states that the main purpose of control could be described as the creation of conditions to motivate the members of Inter-organizational Relations (to be known hereafter as IR) to achieve the desired or forecast results. The need for control rises as it becomes evident that individuals do not tend to act on behalf of others, but instead do so in their own interests. When two or more companies form a network where part of the company is shared, control gets involved in individualistic behavior to enhance itself in favor of IR and thus avoid undesirable actions.

Following a literature review, we found a gap in the contributions on management control within the framework of IR in the field of franchising, corroborating the findings by Van der Meer-Kooistra and Vosselman (2006).

The relationship between the franchisor and its franchisees is the establishment of relationships between different companies that are legally independent but join to develop a business together. According to the criteria established by the European Franchising Code of Ethics (in its most recent version that came into effect January 1, 1991), a franchising company is considered to be:

Any domestic or foreign entity that corresponds to a business concept tested through pilot experiences; it possesses its own transmissible and distinct know-how; it holds the license or ownership rights of brands or hallmarks and is capable of providing training and technical assistance to its franchisees.

The relationship between the franchise and its franchisee should become formal by the franchise agreement, which is the contract by virtue of which a company, the franchisor, grants to the other part, the franchisee, the right to hold a franchise to market certain types of products and/or services in exchange for direct or indirect financial remuneration.

As in other types of business relationships, the system of franchises requires the application of supervisory measures and the enforcement of the contractual relationship and any others related to the pursuit of common objectives.

This paper contributes to the existing literature on management control of inter-firm relationships. First, the literature gap about a rather singular business relationship in the field of franchises has been covered, showing the mechanisms used by a franchisor to reach short and long-term business goals. The franchisor, used quantitative and qualitative tools: the former (mainly accounting) to avoid common opportunistic franchise behavior related to the royalty payments, which are the principal income source for the franchisor; the latter, internal and external qualitative tools that assure the fulfilment of agreed conditions, know-how, services and products offered to customers, and resolving unexpected non-financial problems, as well as encouraging personal relationships and trust. Second, this study shows that the franchise system is consistent with the Van der Meer-Kooistra and Vosselman model (2000), as shown in parallel conclusions about the factors that play an explanatory role for selecting from different possibilities of management control tools, being the influence of risk factor the most significant issue.

This paper is divided into the following parts. First, the research goals and the specific aspects to be studied are introduced. Second, there is a brief reference to the methodological framework of the study. Third, the characteristics of this study are approached. Fourth, the specific details about the particular study in question -a franchise in the Spanish restaurant sector- are presented. Fifth, the control mechanisms used by the franchise under study are reviewed. Sixth, a description of the behavior of the franchise system from the perspective of the Van der Meer-Kooistra and Vosselman model (2000) is done. Finally, the conclusions that outline limitations of the study and future research possibilities are discussed.

Objectives and Research Questions

Following the methodology suggested by Dul and Hak (2008), the objective proposed aims at contributing to the development of the model created by these authors to structure inter-firm relationaships. Additionally, this paper will try to overcome the little attention paid in the literature about franchising control tools, by analyzing the systems of management control used by the franchisor to ensure that the network of franchised establishments achieves the objectives established, using the conceptual framework of the existing IR. In order to achieve this, this study intends to test whether the system of franchises presents one of the patterns they have proposed: the market-based pattern, the bureaucracy-based pattern or the trust-based pattern.

The specific points raised in this research are i) an in-depth examination of the relationship between the franchisor and franchisees; ii) an analysis of the behavior of the franchise as IR from the standpoint of the theoretical model proposed by Van der Meer-Kooistra and Vosselman (2000); and iii) a comparison of their findings in two companies which contracted a task considered critical for the core business: maintenance, since the franchisor then externalizes not only one critical task but actually its core business, that is, the whole production process. Our main goal is to determine if the conclusions provided by these authors fit into the franchise relationship. Thus, our research will contribute to the strengthening and generalization of the model.

Since patterns are identified through the features of the management control mechanisms used, we have analyzed such mechanisms in the franchise under study, that is, determining if they are based on a) competitive bidding, b) specific and standard norms and rules, and c) friendship, confidence and fairness. Those features are well determined and explained in the model and are considered necessary conditions to lead to specific conclusions.

Theoretical Framework

Interorganizational Relationships and Management Control

Analyses of the relationships between organizations are no longer a novelty since they have been performed for the last 40 years from different points of view: the Theory of Organization, Strategic Management, Marketing or Organizational Economics. In the last one, the development of the Transaction Cost Theory and the Agency Theory were of a decisive influence.

Studies on the function of accounting and management control in these relationships are less developed (Gulati & Singh, 1998; Sobrero & Schrader, 1998; Jarillo, 1988) and occurred later than those related to other disciplines occur. Although, most of the studies were about the supplier-client relationship (Otley, 1994; Hopwood, 1996) where management accounting initially contributed to the study of the cost-transaction theory; as time passed, certain companies were observed to have a close relationship that went far beyond the objective of saving costs. Although these organizations had independent legal profiles, their dependence on their business activity led them to collaborate so closely that decision-making, in some respects, was shared in a way that has been denominated as hybrid (Hopwood, 1996). Subsequently, it has been shown that successfully maintaining long term relationships like these is a question of resolving difficulties as they arise; thus management accounting and control can have an important role in the management and development of these interrelations (Dekker, 2004).

Within the literature on business organization, there are three aspects to consider in IR: motivations to create these relationships, the choice of how to conduct them, and their overall efficiency and development. The control of IR is closely related to the governing structure established (Kale, Singh & Perlmutter, 2000).

The accounting and control aspects of these relationships have been studied by different authors, as in the joint-ventures agreements by Groot and Merchant (2000); subcontracting by Langfield and Smith (2003). Gietzmann (1996); Van der Meer-Kooistra and Vosselman (2000); and integration agreements between supplier and client by Frances and Garnsey (1996), among others. However, as far as we have been able to verify, little or no attention has been paid to the franchising system, even though its hybrid structure is very well known and wide-spread, especially in the retail sector (Van der Meer-Kooistra & Vosselman, 2006).

Most relationships between independent companies are originally aimed at reducing transaction costs (decisions to make versus buy), which is why accounting management systems have been directed towards offering information regarding cost. However, as IR advance and become more complex and long lasting, problems arising in the relationship must be resolved. For doing this, the systems of accounting and control management (to be hereafter referred to as SACM) can offer useful tools that have also recently appeared in research, including the conflict of goals (Van der Meer-Kooistra & Vosselman, 2000), breach of contract (Baiman & Rajan, 2002), or the use of shared information (Cooper & Slagmulder, 2004), among others. In addition to the studies that approach each of these objectives separately, there are others directed at analyzing the relationships between the two objectives (Tomkins, 2001; Dekker, 2004; Sánchez, Ramírez & Vélez, 2006).

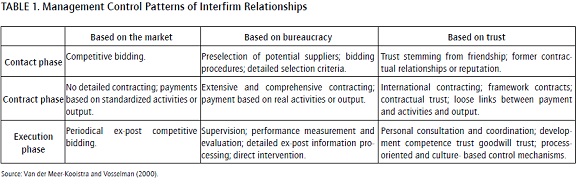

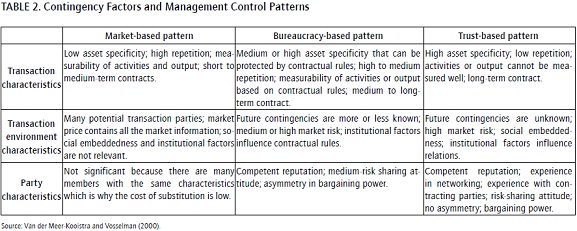

The model proposed by Van der Meer-Kooistra and Vosselman (2000) establishes three management control patterns that rise from the relationship among three models governing IOR (two derived from the transaction cost theory: market and bureaucracy, and a third when including trust in the analysis); and two different perspectives of the relationship between companies. Although they do recognize that these patterns are ideals, normally elements of all three are found in the IOR. The two perspectives are: i) the phase where IOR is found (contact phase, contract phase and execution phase and ii) the characteristics of the three adjacent factors (of the transaction, of the surroundings of the transaction and of the parts of the transaction). For each case, researchers identify the most adequate control mechanisms.

The model is summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

The Perspective of Transaction Cost Economics

The perspective of transaction cost (TCE, Transaction Cost Economic perspective) identifies three basic operation-governing structures: the market, the power hierarchy or a hybrid (Williamson, 1981). Following this philosophy, one or another will be used depending on its cost. The cost includes such items as the assets involved, the uncertainty implied in operations taking place, their frequency, and other elements whose cost is more difficult to measure, like the rationale of the human team, and the possibly opportunistic behavior of any of the parties involved who might try to exploit the situation to their advantage.

From the standpoint of IR, the application of this perspective could present some difficulties from the moment that related organizations become independent, and both the government based on the market as well as that based on the hierarchy, are found to be inefficient. The third option offers a hybrid system, which also gives rise to certain complications. The emergence of opportunistic behavior in some IR has compelled the relationship to be reinforced by the signing of a contract in which both parties are obliged to comply with certain conditions, in the form of performance standards, to avoid or prevent such behavior. For these and other reasons, in the last few years the TEC has been criticized for not being able to efficiently explain or understand IR forms of government (Larson, 1992). Likewise, Dekker (2004) identifies three reasons why this perspective is too weak to be applied on relationships between organizations: it pays little attention to different IR goals and formats; its static vision is inadequate to explain governing mechanisms since it ignores social influence as a control mechanism. Nevertheless, in the relationships within one company, its potential has been thoroughly demonstrated. Based on the contractual aspect of IR, as shown in certain research (Gulati & Singh, 1998; García, 1996), it is impossible to regulate every single aspect that can lead one of the parties to benefit unilaterally from the IR. This is the reason why other mechanisms should also be considered to control relationship, like incentives and a supervision that is formally imposed, and it is so much the better if accepted by both parties. This situation occurs in the franchise system as will be seen below.

On the other hand, according to the ideas of Van der Meer-Kooistra and Vosselman (2006) in their analysis of the study made by Speklé (2001), with reference to the relationships found within one company, three of the control mechanisms defined by Speklé could be applied to IR: those that use a combination of contractual methods and institutional agreements as forms of control.

Trust in Inter-organizational Relationships

As a result of the application of the transaction-cost perspective, formal mechanisms of control usually evolve, typically developing from a contract or some other performance standards. However, as the relationship between companies becomes more durable and their shared operations or activities become more relevant for the success of the shared business, these formal measures begin to slip away, that is, they no longer respond to the needs of the relationship. IR require different mechanisms to help resolve other issues that, by nature, elude the scope of the formal control mechanisms provided by the TCE.

In these cases, the mechanisms based on trust have been found to be the most efficient, as demonstrated in the research of such authors as Van der Meer-Kooistra and Vosselman (2000), Tomkins (2001), Langfield and Smith (2003), Dekker (2004), Cooper and Slagmulder (2004), Ouchi (1979), among others.

These mechanisms based on trust have been especially useful in relationships where the assets involved are significant, either due to their worth or for the value of the roles they play in the company and in environments of high uncertainty. At the same time, in the same way as uncertainty, another situation mentioned that should be taken into consideration occurs when companies have a strong and close dependence relationship due to investments (Van der Meer-Kooistra & Vosselman, 2000). In this regard, the franchise system is unique in the special relationship between its two agents and the way investments are made; considering that trust could be of potential value to improve joint management, because both the franchisor and franchisee can profit from the positive consequences described by researchers when trust is achieved between them, as detailed below.

Trust, in the IR field, is complex to define. Maybe for that reason it is difficult to find its definition in the literature related to SCAG. It is more frequent to find the effects that it can achieve. To focus on its meaning, two examples could be mentioned. One is a definition offered by Sabel (1993): “trust is a mutual security in the fact that none of the parties involved will exploit the weaknesses of the others”. The other, found in Dekker (2004) and attributed to Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt and Camerer (1998), defines trust as “a psychological study that consists of the intention of accepting the vulnerability derived from being at the mercy of the intentions or behavior of another, in exchange for some positive expectations”. “Trust is not a behavior (coordination) or a choice (adoption of a risk), but instead is an underlying psychological condition that can cause or result in such actions” (p. 395).

Some consequences described by researchers when trust is reached between parties in IR are: i) trust makes it easier to reach agreements, ii) it allows the parties involved to focus on core aspects of their business, iii) it reduces the risk of opportunistic behaviors, iv) when trust exists, there are more expectations to acquire benefits from the relationship (Tomkins, 2001), v) it reinforces the relationship on all sides, making for a more lasting relationship, indicating if some part of the relationship must change, activating the interaction between the parties so that they can share knowledge and it promotes the consideration of each other's interests (Johanson & Mattson, 1987). However, as highlighted by Vosselman and Van der Meer-Kooistra (2009), among others, there is a connection between control and trust in that: “Trust, therefore, helps both produce control and add control” (p. 280). Thus, control and trust have a reciprocal effect and both mean to maintain positive expectations for the future of the relationship.

According to several studies, trust has been classified using different criteria. Sako (1992) identifies three types of trust: contractual trust, competent trust and goodwill trust. The contractual type is based on accepting that people trust more in the morals and honesty of the other party, both through verbal expression rather than in written forms of commitment. The more contractual the trust is, the less risk of opportunistic behavior. Competent trust refers to the expectations that other parties will be able to carry out their tasks satisfactorily, since they have the technology, knowledge and skills to do so. Goodwill trust is based on the belief that each of the parts is going to act on behalf of all without the need for supervision; under this type of trust the vulnerability of one of the parties increases with respect to that of another. This latter way of trust would be the most complex and difficult to achieve.

In spite of the different studies analyzing the significance of trust in this framework, and of the fact that trust is described as the least expensive form of control, there remains much research to be done (Van der Meer-Kooistra & Vosselman, 2006). The main contribution of our research is to study the function of trust in the relationships between companies within a franchising system.

Nevertheless, it does not seem that formal control mechanisms could be totally replaced by trust, as stated by Dekker (2004). On the one hand, it is indicated that formal mechanisms could be substituted when a certain level of formal control has already been carried out to guarantee the relationship; on the other, trust moderately affects the relationship between control problems and the use of control mechanisms; at the end, it is necessary to identify the various purposes of control.

In conclusion, both control and trust are mechanisms to reduce risk within the relationship, as indicated by Das and Teng (2001), and control is a better technique to minimize the risk through a specific and formalized system, specifically in non-equity alliances, whereas trust is related to the perception of risk and is desirable and effective in all sorts of relationships (Das & Teng, 2001).

Research Method

With the purpose of carrying out an empirical study, different methods or research strategies can be employed (surveys, data analysis, experiments, historical analysis or a case study). The choice of one method over another depends on the issue to be researched, as assumed from the conclusions drawn by Tamarit (2002); on the need that the researcher has to control what occurs; and on the moment in time that the event under analysis might take place.

In the empirical study being presented, and continuing in the path of Yin (1989, 1994, 1998, 2003), and Eisenhardt (1989), we have selected a Case Study for three reasons: i) the research is going to focus on a contemporary issue; ii) we try to respond to the question how?; and iii) the conduct of events will not require supervision by the researchers. Furthermore, as Hamel, Dufour and Fortin indicate (1993), one of the objectives is “an in-depth study of one case in particular”, as is the study at hand. According to Yin (1989), a case study is particularly appropriate when the activity under study is rather intricate, as it has to explain and describe this activity in a specific manner.

Information was obtained during 2006-2007 from one of the two parties that make part of the franchise: the franchisor. This decision was made for different reasons. It is the party whom the formal existence of the franchising company depends on; it is on the part of a unilateral power to accept a new franchisee or withdraw the concession of an existing one; and the franchisor is responsible for a series of fundamental tasks to make a long-lasting relationship possible. The franchisees, although are the ones who bring in the income, have a less active part in franchise management, even so, their opinions are taken into account in different ways.

To obtain information three in-depth interviews were held with the Finance, Expansion and Establishment Directors, in the areas of the franchise that deal directly with franchisees. The information obtained is qualitative and summarizes the opinions of those interviewed, as well as their perceptions and/or observations of dealings with franchisees. There was an initial guideline of questions to be asked, notes were taken and interviews recorded. Afterwards, the information was transcribed and then returned to the respondents to be approved in order to guarantee its reliability, accuracy and precision.

This study has used the conceptual base of IR, especially TEC concepts and those aspects related to trust, as well as the empirical research of various authors related to management control in this field.

The object of study was a Spanish franchise within the restaurant sector, which we will call FDT to keep it confidential. The reasons for choosing this franchise are, first, that we could count on the ample experience of the franchise and the franchise system; second, the evolution achieved with respect to the number of establishments that form this franchise is significant, and shows that the management of their expansion has granted enough experience to offer our research a relevant and dynamic wealth of material. Last, but not least, the ease of access to people and information, and the personal relationship of the researchers with the franchise, has made it possible to research aspects that are not always positive, and round which it is usually difficult to obtain information. All of them have expressed their particular points of view under the condition that they will remain anonymous.

The Case Being Researched

General Aspects

FDT is a Spanish franchise dedicated to the restaurant trade established in 1988. It began to franchise in 1996 and by 2007 already had 144 franchised establishments. In 2001, its economic and financial situation was very fragile but it managed to recover by 2004, to the point of being considered the leader in its sector and evaluated among the top ten in Spain in volume of resources (Ranking Franchisa-30, year 2004, Anuario Español de Franquicias). In 2006, it was considered number one by one of the most prestigious companies offering a wide range of services to franchises in Spain.

With respect to its strength and presence in the sector, FDT has an average of 26 other associated franchisees belonging to its network since 2002, and there were six outlets that closed down in this same period, both figures being higher than those presented by the competitors. The reasons provided by those interviewed for the closing of franchise outlets were the following: expiration of the outlet's rental contract, failure to comply with the terms of the contract, a lack of enthusiasm for the project, the retirement of the franchisee, bad location, problems among partners, bad management, or an insufficient profile for the business.

In the franchise system each franchisor unilaterally defines some initial conditions, necessary but not exhaustive, to admit a new franchisee. In the case of FDT, these conditions are a minimum investment of €157,000, a minimum population size of 15,000 inhabitants, an entry fee of €35,000 and a publicity charge of 2% of the turnover; royalty payments are 6% of turnover; the initial contract duration is 10 years. The site itself must be at least 80 or 100 square meters and should have smoke vents. Finally, no financial aid is provided for the initial franchise investment.

Organizational Structure and its Functions

The interviews with those in charge of the different departments reveal their respective duties and enable us to determine which of them will be in contact with the franchisees, and who will exercise the control measurements of the IR. Thus, FDT is found to be divided into seven areas of operation: Expansion, Construction, Establishment, Purchasing and Sales, R&D, Marketing and Finances. The information obtained is summarized as follows:

Expansion: It is in charge of incorporating new franchisees and analyses the viability of future franchisees keeping in mind: i) the capacity and solvency of the franchisee candidate to manage a business, ii) the size of the population in the location of the new franchise and iii) the specific physical situation of the new locale. This department is also responsible for organizing attendance at specific franchise trade fairs taking place in the country.

This department participates directly in the relationship to be created between the franchisor and the franchisee, since it is the first contact that the franchisee will have with the franchise. In the first contacts the department has to clarify the working framework for the future relationship, which implies specifying the services that the future franchisee will receive from the franchise, as well as the obligations entailed in the franchise system.

Construction: It is responsible for adapting the new locale to the franchise format and image and for controlling and monitoring its construction. The service can be carried out in two formats, i) Key in hand, which means delivering the premises all ready for inauguration, doing the construction work in the locale through agreements with builders with whom the FDT has already signed agreements or with some local builder in the franchisee's vicinity, and the franchisee must repay the amount of this investment; ii) the franchisee can carry out the construction work on his own but under the direction and supervision of the Construction Department. To do this, the FDT has a manual that specifies the format of the company's public image and the measures of security that the new locale must incorporate; in these cases, it is the franchisee who hires the builder.

Establishments: This department is very important in the life of the franchise since it is the one with the closest relationship to the franchisee and is responsible for the image and quality of the service provided. Therefore it is in charge of i) training the new franchisee about how to apply the brand's know-how; ii) controlling and supervising the franchisee in recycling formation, economic stability, and complying with all established quality standards; and iii) selecting the appropriate information technology system to be implemented by all the franchisees, centralized in the parent company that can then monitor and control the reality of the franchise.

In order to perform these responsibilities, this department invests in the elaboration of well-illustrated manuals about the operations that the franchisee must carry out, as well as of the management entailed. The mechanisms used by the FDT for supervising and tracking the performance of the franchisee are of two types: internal, including periodical visits, communication by telephone or internet from franchise personnel who belong to the Establishment Department; and external, the recruiting of independent services or companies to play the role of “a mysterious client”.

Central of Purchasing and Product Sales: To achieve the necessary uniformity so all the franchisees can offer the client the same type of product (tapa or hors-d-oeuvre) that the franchisor is famous for. This dependence is in charge of i) managing for the franchisees the purchases of raw material and other consumable items, bargaining with suppliers for the correct price and quality, and also ensuring a competitive price for the franchisee; ii) the logistics to insure that the raw material arrives to all the franchisees at the right moment; and iii) motivating and enhancing the consumption of the raw materials that the central office provides. This department also invests in the elaboration of permanently available manuals about the purchase and manipulation of the products available to the franchisees.

Research, Innovation and Development: For the FDT this department is responsible for: i) elaborating the recipes for the products (tapas or hors-d-oeuvres) that the franchisee will offer the prospective client, ensuring a competitive and adequate cooking procedure for the type of product and client; ii) periodically renovating recipes; iii) creating and maintaining a centralized cooking plan that illustrates the recipes for the franchisees according to the indications of the specialist who has been in charge of their design; iv) training the franchisee to: a) elaborate products so that the client in all the franchises finds uniform products characteristic of the franchise, although there is a certain margin for each franchisee, under supervision, to offer a product that is typical of that particular zone, and b) to ensure the expiration date and competitive logistics; v) providing the franchisee with price break downs: cost and margin per product. This department has some detailed manuals available concerning the elaboration of recipes, which are constantly up-dated as the offer is modified.

Marketing: This area is responsible for launching campaigns to advertise the brand, ensure the increase in final franchise consumers and promote the franchisees themselves individually. This department has to carry out marketing campaigns, design advertising brochures, and select the media and formats to be used. In this sense, because each franchisee is located in different surroundings, agreements are reached with each one in the use of different local media for conducting campaigns and in other aspects related to the content that best adapts itself to each setting.

Finances: This department deals with the financial management, accounting and management control of the franchisee company and the franchisor. It exchanges information with the rest of the departments in order to be able to follow up closely different key variables in the company, whether quantitative or financial or related to quality, in order to determine the makeup of the managerial team.

Case Results: Management Control Mechanisms Used

FDT's control mechanisms over its franchisees are more related to business performance (qualitative) than to economics (quantitative), which is an important weakness in the franchise management system, according to the Financial Director. In this sense, the Director affirms that an accounting system that will be common to all the franchisees is being installed, though centralized in the franchisor, as in many cases information requested by the franchisees arrives late, does not arrive or arrives erroneously. Moreover, this Director strongly suspects that in some cases the information itself has nothing to do with reality. In this respect, this person points out that the income of the franchise is at threat since the income, royalty payments and publicity fees are lower than what they should be because, being determined by the percentage of sales, some franchisees report a lower volume of sales in order to pay less. This type of opportunistic behavior seems to be more frequent among new franchisees, or at the beginning of the relationship.

On the other hand, these mechanisms can be found in two well-differentiated parts of the relationship: before the signing of the contract, and throughout the development of the franchise relationship.

Quantitative Control Mechanisms

Quantitative mechanisms are in play from the outset of the franchisees' selection process, for example: minimum investment, minimum premises and population size, economic capacity and viability, or the concrete location of the locale.

Subsequently, until now, the control mechanism that has been used during the relationships is the control of revenues. This control is performed indirectly. The method is to contrast and reconcile two different sources of information. On the one hand, the Purchasing Centre provides the bulk of raw materials to the franchisees at a competitive price in order to ensure uniform quality in the products offered to the customers. On a regular basis, it informs the financial department about the deliveries (in amount and price) made to each franchisee (raw material purchase by the franchisee). On the other hand, the Financial Department compares the sales revenues declared by the franchisee, the expenditure in raw material purchases obtained from the Purchasing Centre and the cost and margins of the price break-down given to the franchisee; thus inexact information can be detected and roughly approximated. In the Financial Director's opinion, this task requires an inefficient use of time and resources that ought to be eliminated.

Another method that could be used is to consult the Mercantile Registry, but this is not trustworthy information either because its auditing is not mandatory.

Qualitative Control Mechanisms

These types of mechanisms control the franchise business and are more precise, formal and periodical. FDT, like other franchises, uses two types of mechanisms: internal and external. From each of these it receives a report used to develop such performance measures as further recycling, training in the kitchen, services, or other areas, or else to notify the franchisee, when necessary, of any contract or agreement breaches that have to be corrected.

Qualitative control mechanisms are grouped under four headings according to the aims the franchisor wants to achieve.

To Supervise the Fulfilment of the Conditions Agreed

The control is carried out by what is known as a “mysterious client”. These are independent companies recruited to visit the franchise locale periodically, and are obviously unknown to the franchisee, as they play the role of an ordinary client. In this method (frequently used not only by franchise systems but also by banks and supermarkets), very valuable information is obtained about the products offered and their condition and quality without the personnel being aware of it or of being observed. All franchisees know that they can receive the visit of a “mysterious client” at any time, but obviously do not know exactly when or how often this will occur. The mysterious client makes out a report according to a previously defined format, about the variables that the franchisor wishes to monitor or control.

To Know and Resolve Problems

Internal mechanisms include periodical contacts with personnel belonging to the Establishment Department (responsible for the zone or other areas of the matrix). These contacts can be made by telephone, internet or in face-to-face visits. This in-person visit is a formal procedure on the part of the franchisor, since it is considered the best way to eliminate opportunistic behavior. For example, these interviews claim to permit closer ties between the franchisee and their personnel. Furthermore, the franchisee perceives the total and continuous support of the parent company, both in helping to resolve any type of problem, and freely expressing complaints or grievances about anything deemed necessary.

This visit oversees all aspects of locale, hygiene, kitchen, and price-list conditions. Telephone or internet communication is used preferably for very specific matters or with those franchisees who have reached a level of trust that allows the number of visits to be reduced. Even so, it is necessary to mention that these visits could also be interpreted by franchisees to be a control with negative connotations that is aimed exclusively at discovering errors and penalizing them instead of being a means of assistance.

To Ensure Gastronomic Expertise, Service and Management

Control mechanisms involve three fields: gastronomic, restaurant services and management. The franchisor organizes two types of training courses: initial training courses and recycling ones. These courses are provided in the parent company to a group of franchisees and/or their hired personnel. The subject matter can be the restaurant trade or management.

In the restaurant field, it is a question of training both kitchen personnel in charge of elaborating products (habitual or new ones), as well as personnel that serves in the establishment (waiters/waitresses), either because they have had little training or because they are supposed to provide a special emblematic type of service to the client. In the case under study, for example, the objective is a young, jovial, informal atmosphere that does not overlook the necessary dose of respect for the customer along with quick and professional service. It is customary for the franchisee to form part of the staff that serves in the establishment, either in the kitchen or as a waiter.

In the area of management, the idea is usually to train the franchisee in accounting, the use of software billing programs and cash management, as well as in the importance of sending accurate information on other indicators in the balance score card that are important for both of the parties in the franchise relationship.

To Encourage Personal Relationship and Trust

The training courses, in addition to their immediate objective of training, are also used by franchisor personnel to bring the parent company closer to the franchisee, to generate an atmosphere of camaraderie and friendship, and promote relationships between the people who make up the network. In that way, the franchisee does not regard the parent company merely as a foreign element that controls and supervises, but rather as a group of people and services that can be approached for assistance in resolving problems, as well as for compliance with contractual commitments.

The interviewed personnel coincide in the belief that the longer the franchisee belongs to the network, the closer the relationship becomes, and the franchisee comes to realize and appreciate that the benefits and protective umbrella provided by such an entity fully justify the payments that must be made.

The methods for supervision and monitoring begin to wane or become more sporadic, giving both parties more time to make the business run in collaboration, instead of in competition. This is one of the results of the above-mentioned trust.

Once again, the positive effects of achieving trust are manifested. Thus, the department heads that have been interviewed report that the older the relationship, the more the franchisee complies with conditions voluntarily and not solely due to obligation, since they appreciate how achieving better results also benefits their own business.

Conclusions

Under this system, the franchise is in the hands of the franchisee, being the reason why the risk run by the franchisor is considerable. Another important element is the number of franchised establishments. Currently FDT holds 144 establishments, 23 of which are located abroad. This means the franchise must depend on a great number of businesses. Initially the way to assure fewer problems is a control based on rules and written procedures known and accepted by all parties. Hence, there is a wealth of information to enable efficient management of the company from its core. However, total control (or regulation) is both impossible and impractical (Baiman & Rajan, 2002).

These strict mechanisms are especially necessary at the beginning of the franchise relationship. When this relationship becomes long lasting the knowledge about the franchisee is greater, professional skills can be checked, and mechanisms based on trust are developed. On the other hand, there is also a change, reflected simultaneously in the attitude of the franchisor who begins to consider the relationship more as a symbiotic one than a burden.

This fulfils the first objective that Dekker (2004) explains about control, being “to create conditions that motivate the different participating parties of the IR to achieve desired and expected results”. After achieving this degree of competent trust, controls are less frequent. The time and resources dedicated to analyzing and managing information decrease, and the franchise tends to dedicate more of its resources to improving the company and sharing with the franchisee the experience and knowledge of their market, so that together they can reach the best possible results that derive in mutual benefits (goodwill trust). Trust appears after the controls have been sufficiently exercised and the franchisee has responded favorably. This does not mean that formal controls totally disappear since the circumstances and context can change as the behavior of the franchisee could be modified as well.

By means of the information obtained from FDT personnel, can be concluded that the selection of the franchisee is fundamental to guarantee the strength of the IOR and achieve the desired results, which in turn, coincides with the conclusions of other researchers (Grandori & Soda, 1995; Ireland, Hitt & Vaidyanath, 2002). This is the explanation for franchisors to invest more resources in designing a selection process that permits a reduction in the need for control.

Finally, the interviewed staff coincide in their observations that an increase in the number of franchisees is a way of diversifying risk, building and consolidating the social presence of the trademark, while at the same time the direct and familiar relationship with franchisees begins to suffer. Thus, the expansion policy must be planned without excessively ambitious objectives in order to achieve enough balance between the size of the franchise and a close friendly relationship with franchisees.

Others studies have been performed in the field of franchising and control systems but in spite of them, our research provides the scientific and academic community with other remarkable contributions. Among others, we include the following two: the study carried out by Ramírez, Vélez and Álvarez in 2013 (including data from 240 franchisors), revealing the broad uses in franchising of similar mechanisms based on the TCE perspective. This case study backs them up and is consistent in terms of its findings that are not specifically valid for one case but extrapolated. Nevertheless, our research also includes the trust approach as quite an important factor at improving the symbiotic relationship between franchisor and franchise and the effect of both (TEC and trust) on the type of mechanisms applied. Czakon (2012) studies the franchising system but taking into consideration its advantages as a network to improve business efficiency and success.

In the analysis of forms or patterns that IR presents in the franchise system, and in the analysis of the management control mechanisms developed under the model that Van der Meer-Kooistra and Vosselman (2000) proposed, we have found this model adequate to be applied to this franchise. Conclusions have points in common with their research, in spite of some differences, for the following reasons:

i) The application that these authors make is related to a regime of subcontracting or externalization of a function (maintenance) of a company; this function is important but not the mainstay of the related industry.

ii) Subcontracting is the type of relationship between companies that is most similar to the franchise systems to be found today. Nevertheless, in the case of the franchise, there is one important thing that cannot be forgotten: the franchisee carries out the whole production process and the sale of the product. That means that the franchisor externalizes the fundamental part of the business, its core, into a legally independent company, and it is not simply one of the functions needed in the chain of production.

This circumstance, in our opinion, is relevant and thus conditions the type of relationship as much as the design of the tools used for management control. The companies under study by Van der Meer-Kooistra and Vosselman rely on their great experience in subcontracting, and the relationship is of long-term duration. In the case of FDT, both of these characteristics are also present.

Comparing the form of franchise management control under study with the patterns indicated by Van der Meer-Kooistra and Vosselman, we can conclude that the control of relationship is more similar to the bureaucracy-based control pattern, although it could be a hybrid between this and the trust-based pattern. With respect to contingency factors, we can conclude that the relationship can also be considered to be bureaucracy-based. The reasons for these conclusions are now set forward.

Management Control Patterns in Inter-firm Relationships

The contact phase of the model based on bureaucracy is characterized by the pre-selection of potential suppliers, bidding procedures, and detailed selection criteria, among others.

When seeking new franchisees (contact phase), the franchisor uses two approaches. On the one hand, it presents and organizes trade fairs to make its establishment known, to distribute information to potential franchisees, and to contact with possible candidates that will later be studied. On the other, later on, it carries out a thorough screening process of these candidates, using well defined criteria, including both the initial conditions required (minimum investment, minimum premises and population size, etc.), and other studies carried out by the Expansion Department, such as economic capacity and viability or the concrete location of the locale.

Once the new franchisee has been selected, a common practice in franchise systems is the presence of a type of contract that is an option for the potential franchisee to purchase the franchise, and that permits both parties to advance in the completion of certain operations and analyses prior to the final contract that will seal a definitive agreement. This document (Pre-contract or Reservation Contract) is simply a preferential possibility for the franchisee to join the network. On being granted the preliminary contract, the franchisee pays an entry fee on account. These actions constitute an intermediate step between the first contact and the contract phases.

The contract phase of the Model based on Bureaucracy is defined by extensive and comprehensive contracting; payment is based on real activities or output.

The franchise contract phase regulates the rights and obligations of the franchisor and franchisee for the duration of the relationship. This document reflects the willingness of the signatories to participate in a business relationship through a franchise system. During this stage both parties subject the contract to rigorous study before its signing, so that it will clearly, and unambiguously, regulate the obligations that the franchise system imposes on the franchisor and the franchisee. This contract will necessarily include the transfer of the trademark to the franchisee, the transfer of the know-how, and the provision of continuing assistance to the franchisee for the duration of the contract.

The contract is the best way to avoid unpleasant surprises in the future and thus is intended to regulate all possible contingencies or causes of future conflict. Some of the points covered are the amount and date of individual franchise payments, initial and subsequent training in production, as well as management (if the franchisee needs it), delivery of the manuals and cookbooks necessary for running the business, etc. Payments, as previously indicated, are based on the sales revenue.

The execution phase of the Model based on Bureaucracy includes supervision, performance measurement and evaluation, detailed ex-post information processing and direct intervention.

The execution phase of the franchise contract includes periodical monitoring of the franchisee by the franchisor. Most of the mechanisms (area representatives, “mystery clients”, telephone and internet contacts) deal with the way the franchisee treats the image of the brand or know-how, as, for example, in its supplies, adequate customer service, the correct outfitting of the locale in the required aesthetic and sanitary conditions.

If shortcomings are found during controls, the franchise gets in touch with the franchisee to resolve the causes of the situation (through recycling training, warnings about weak points, etc.).

Contingency Factors and Management Control Patterns

The transaction characteristics of the Model based on Bureaucracy refer to the existence of medium or high asset specificity which can be protected by contractual rules, high to medium repetition, measurability of activities or output based on contractual rules, and medium to long-term contracts.

In that sense, the main contractual rules between franchisor and franchisees are the transfer of the trademark and know-how, which are the principal assets, since without them the relationship cannot exist. The relationship is also intended to be long term; the contract is initially signed for ten years. The quality of products (tapas) and services (customer service) are determined in the manuals available to the franchisee dealing with the elaboration of products and service procedures.

The environmental transaction characteristics of the Model based on Bureaucracy include aspects such as more or less well-known future contingencies, medium or high market risk, which are institutional factors influencing contractual rules.

In the franchise under study, before accepting the franchisee, the franchisor analyses the situation (competition, location, etc.) in an attempt to minimize risk. Throughout the relationship, the surrounding situation remains under observation, since competition has to be taken into account as in any other type of business.

Negative future contingencies are controlled as broad experience in the sector is reflected in the contract and manual, norms or indications, that regulate those aspects that might have caused problems for previous franchisees in the past; other potential problem sources are also dealt with in meetings and congresses related to the sector.

Institutional factors influence the relationship, since the franchise has a legal framework that must be respected and that is subject to changes that must be introduced as soon as they go into effect.

The party characteristics of the Model based on Bureaucracy are, in summary, the following: competent reputation, medium risk sharing attitude and asymmetry in bargaining power.

The competence of the franchisee is guaranteed since the process of selection analyses the experience, training and suitability of the franchisee in the sector of tapas, as well as determining if he/she holds enough experience in management. Even though some requirement may be lacking, if the candidate is considered to be good the franchise will train the franchisee and his personnel in their weaker aspects.

The power relationship is asymmetrical since it is the franchisor who defines the know-how of the franchise and most of the rules in the relationship.

This study is merely an approach toward understanding the mechanisms that allow IR to achieve the desired results, especially in the world of franchises that has some unique characteristics that distinguish it from other IR. In this case, the study is limited to a trademark in the restaurant trade, which presents limitations typical of this sector. It would be interesting to develop further research in order to determine if these conclusions (depending on the industry the franchise is dedicated to) correspond, or not, with the size of the network, its international presence and the length of time the franchise has been in operation, highlighting the role of the binomial trust-risk and its effect on the relationship and its management control mechanisms.

A longitudinal case study can complete this view, given that it can be seen whether the long-term relationship affects the trustworthiness between the franchisor and franchises, as is claimed by people interviewed in this case study, and how this could change the type of control tools used and pointed out by other researchers such as by Vosselman and Van der Meer-Kooistra (2009), and Vélez, Sánchez and Álvarez (2008).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the franchise management who participated in the study for the time and data they generously provided.

References

Anderson, S. W., & Dekker, H. C. (2005). Management Control for Market Transaction: The relation between transaction characteristics, incomplete contract design and subsequent performance. Management Science, 51(12), 1734-1753.

Anuario Español del Franchising y Comercio Asociado (2004). Gestión Internacional del Franchising. Barcelona: S. L.

Baiman, S., & Rajan, M. V. (2002). Inceptive uses in Inter-firm relationship. Accounting Organizations and Society, 27(3), 213-238.

Borch, O. J., & Arthur, M. B. (1995). Strategic Network among Small Firms: Implications for Strategy Research Methodology. Journal of Management Studies, 32(4), 419-441.

Czakon, W. (2012). Business format franchise in regional tourism development. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 23(1), 107-117.

Cooper, R., & Slagmulder, R. (2004). Inter-organizational cost management and relational context. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(1), 1-26.

Das, T. K., & Teng, B. S. (2001). Trust, Control, and Risk in Strategic Alliances: An Integrated Framework. Organization studies, 22(2), 251-283.

Dekker, H. C. (2004). Control of inter-organizational relationships: evidence on appropriation concerns and coordination requirements. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29, 27-49.

Dul, H., & Hak, T. (2008). Case study methodology in business research. Oxford, UK: Eselvier.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 532-550.

European Franchise Federations (n.d.). European Code of Ethics for Franchising 1991. Available at: http://www.eff-franchise.com.

García, E. (1996). El estudio de las alianzas y relaciones interorganizativas en la dirección de empresas: tendencias recientes. Revista europea de dirección y economía de la empresa, 5(3), 109-132.

Gietzmann, M. B. (1996). Incomplete contracts and the make or by decision: governance design and attainable flexibility. Accounting Organization and Society, 21(6), 611-626.

Grandori, A., & Soda, G. (1995). Inter-firm Network: Antecedents, Mechanisms and Forms. Organization Studies, 16, 183-214.

Groot, K., & Merchant, K. (2000). Control of international joint-ventures. Accounting, Organization and Society, 25, 579-607.

Gulati, R. (1995). Does Familiarity Bred Trust? The Implications of Repeated Ties for Contractual Choice in Alliances. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 85-112.

Gulati, R., & Singh, H. (1998). The architecture of cooperation: managing coordination costs and appropriation concerns in strategic alliances. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(4), 781-814.

Hamel, J., Dufour, S., & Fortin, D. (Eds.) (1993). Case Study Method. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Hopwood, A. G. (1996). Looking across rather than up and down: on the need to explore the lateral processing of information. Accounting Organization and Society, 21(6), 589-590.

Inzerilli, G., & Rosen, M. (1983). Culture and organizational control. Journal of Business Research, 11(3), 281-292.

Ireland, R. D., Hitt, M. A., & Vaidyanath, D. (2002). Alliance management as a source of competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 28(3), 413-446.

Jarillo, J. C. (1988). On Strategic Networks. Strategic Management Journal, 9, 31-41.

Johanson, J., & Mattsson, L. G. (1987). Inter-organizational relations in industrial systems: A network approach compared with the transaction-cost approach. International Studies of Management and Organization, 17(1), 34-48.

Kale, P., Singh, H., & Perlmutter, H. (2000). Learning and protection of proprietary assets in strategic alliances: Building relational capital. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 217-237.

Langfield, K., & Smith, D. (2003). Management control systems and trust in outsourcing relationship. Management Accounting Research, 14(3), 281-307.

Larson, A. (1992). Network dyads in entrepreneurial settings: a study of the governance of exchange relationship. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(1), 76-104.

Oliver, C. (1990). Determinants of inter-organizational relationships: Integration and future decisions. Academy of Management Review, 15, 241-265.

Otley, D. T. (1994). Management control in contemporary organizations: towards a wider framework. Management Accounting Research, 5(3-4), 289-299.

Ouchi, W. (1979). A conceptual framework for the design of organizational control mechanisms. Management Science, 25(9), 833-848.

Ramírez, C., Vélez, M., & Álvarez, C. (2013). ¿Cómo controlan los franquiciadores españoles a sus franquiciados? Revista de Contabilidad, 16(1), 1-10.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: a cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 3, 393-404.

Sabel, C. F. (1993). Studied trust: building new form of cooperation in a volatile economy. Human Relations, 46(9), 1137-1170.

Sako, M. (1992). Price, Quality and Trust: Inter-firm Relations in Britain and Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Salas, V. (1989). Acuerdos de Cooperación entre Empresas. Bases Teóricas. Economía Industrial, 266, 47-60.

Sánchez, J. M., Ramírez, C., & Vélez, M. L. (2006). Aproximación a un marco de análisis y desarrollo de los sistemas de control de gestión en las relaciones Interorganizativas. Revista Iberoamericana de Contabilidad de Gestión, 8, 155-176.

Sobrero, M., & Schrader, S. (1998). Structuring Inter.-firm relationships: a meta-analysis approach. Organization Studies, 19(4), 585-615.

Speklé, R. (2001). Explaining management control structure variety: a transaction cost economics perspective. Accounting, Organization and Society, 26(4-5), 419-441.

Tamarit, M. C. (2002). Variables que influyen en el diseño, implantación y control del sistema de costes y gestión basado en las actividades. Estudio de un caso. Tesis Doctoral. Universidad de Valencia, España.

Tomkins, C. (2001). Interdependences, trust and information in relationship, alliances and network. Accounting, Organization and Society, 26(2), 161-191.

Van der Meer-Kooistra, J., & Vosselman, E. (2000). Management control of interfirm transactional relationships: the case of industrial renovation and maintenance. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 25, 51-77.

Van der Meer-Kooistra, J., & Vosselman, E. (2006). Research on management control of interfirm transactional relationships: Whence and whither. Management Accounting Research, 17(3), 227-237.

Vosselman, E., & Van der Meer-Kooistra, J. (2009). Accounting for control and trust building in interfirm transactional relationship. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34, 267-283.

Vélez, M. L., Sánchez, J. M., & Álvarez, C. (2008). Management control system as inter-organizational trust builders in evolving relationships: Evidence from a longitudinal case study. Accounting, Organization and Society, 33(7-8), 968-994.

Williamson, O. E. (1975). Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications. New York: Free Press.

Williamson, O. E. (1981). The economics of organization: the transaction cost approach. American Journal of Sociology, 87, 548-577.

Yin, R. K. (1989). Case study research: Design and methods. London: Sage Publication.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case Study Research. Applied Social Research Methods. Third Edition. London: Sage Publications.

Yin, R. K. (1998). The Abridge Version of Case Study Research. In: Bickman, L., & Rog, D. J. (Eds.). Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods. London: Sage. Publications.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: design and methods. Fifth Edition. CA: Sage.

Zaheer, A., & Venkatraman, N. (1995). Relational Governance as an Inter-organizational Strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 16(5), 373-392.

References

Anderson, S. W., & Dekker, H. C. (2005). Management Control for Market Transaction: The relation between transaction characteristics, incomplete contract design and subsequent performance. Management Science, 51(12), 1734-1753.

Anuario Español del Franchising y Comercio Asociado (2004). Gestión Internacional del Franchising. Barcelona: S. L.

Baiman, S., & Rajan, M. V. (2002). Inceptive uses in Inter-firm relationship. Accounting Organizations and Society, 27(3), 213-238.

Borch, O. J., & Arthur, M. B. (1995). Strategic Network among Small Firms: Implications for Strategy Research Methodology. Journal of Management Studies, 32(4), 419-441.

Czakon, W. (2012). Business format franchise in regional tourism development. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 23(1), 107-117.

Cooper, R., & Slagmulder, R. (2004). Inter-organizational cost management and relational context. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(1), 1-26.

Das, T. K., & Teng, B. S. (2001). Trust, Control, and Risk in Strategic Alliances: An Integrated Framework. Organization studies, 22(2), 251-283.

Dekker, H. C. (2004). Control of inter-organizational relationships: evidence on appropriation concerns and coordination requirements. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29, 27-49.

Dul, H., & Hak, T. (2008). Case study methodology in business research. Oxford, UK: Eselvier.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 532-550.

European Franchise Federations (n.d.). European Code of Ethics for Franchising 1991. Available at: http://www.eff-franchise.com.

García, E. (1996). El estudio de las alianzas y relaciones interorganizativas en la dirección de empresas: tendencias recientes. Revista europea de dirección y economía de la empresa, 5(3), 109-132.

Gietzmann, M. B. (1996). Incomplete contracts and the make or by decision: governance design and attainable flexibility. Accounting Organization and Society, 21(6), 611-626.

Grandori, A., & Soda, G. (1995). Inter-firm Network: Antecedents, Mechanisms and Forms. Organization Studies, 16, 183-214.

Groot, K., & Merchant, K. (2000). Control of international joint-ventures. Accounting, Organization and Society, 25, 579-607.

Gulati, R. (1995). Does Familiarity Bred Trust? The Implications of Repeated Ties for Contractual Choice in Alliances. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 85-112.

Gulati, R., & Singh, H. (1998). The architecture of cooperation: managing coordination costs and appropriation concerns in strategic alliances. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(4), 781-814.

Hamel, J., Dufour, S., & Fortin, D. (Eds.) (1993). Case Study Method. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Hopwood, A. G. (1996). Looking across rather than up and down: on the need to explore the lateral processing of information. Accounting Organization and Society, 21(6), 589-590.

Inzerilli, G., & Rosen, M. (1983). Culture and organizational control. Journal of Business Research, 11(3), 281-292.

Ireland, R. D., Hitt, M. A., & Vaidyanath, D. (2002). Alliance management as a source of competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 28(3), 413-446.

Jarillo, J. C. (1988). On Strategic Networks. Strategic Management Journal, 9, 31-41.

Johanson, J., & Mattsson, L. G. (1987). Inter-organizational relations in industrial systems: A network approach compared with the transaction-cost approach. International Studies of Management and Organization, 17(1), 34-48.

Kale, P., Singh, H., & Perlmutter, H. (2000). Learning and protection of proprietary assets in strategic alliances: Building relational capital. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 217-237.

Langfield, K., & Smith, D. (2003). Management control systems and trust in outsourcing relationship. Management Accounting Research, 14(3), 281-307.

Larson, A. (1992). Network dyads in entrepreneurial settings: a study of the governance of exchange relationship. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(1), 76-104.

Oliver, C. (1990). Determinants of inter-organizational relationships: Integration and future decisions. Academy of Management Review, 15, 241-265.

Otley, D. T. (1994). Management control in contemporary organizations: towards a wider framework. Management Accounting Research, 5(3-4), 289-299.

Ouchi, W. (1979). A conceptual framework for the design of organizational control mechanisms. Management Science, 25(9), 833-848.

Ramírez, C., Vélez, M., & Álvarez, C. (2013). ¿Cómo controlan los franquiciadores españoles a sus franquiciados? Revista de Contabilidad, 16(1), 1-10.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: a cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 3, 393-404.

Sabel, C. F. (1993). Studied trust: building new form of cooperation in a volatile economy. Human Relations, 46(9), 1137-1170.

Sako, M. (1992). Price, Quality and Trust: Inter-firm Relations in Britain and Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Salas, V. (1989). Acuerdos de Cooperación entre Empresas. Bases Teóricas. Economía Industrial, 266, 47-60.

Sánchez, J. M., Ramírez, C., & Vélez, M. L. (2006). Aproximación a un marco de análisis y desarrollo de los sistemas de control de gestión en las relaciones Interorganizativas. Revista Iberoamericana de Contabilidad de Gestión, 8, 155-176.

Sobrero, M., & Schrader, S. (1998). Structuring Inter.-firm relationships: a meta-analysis approach. Organization Studies, 19(4), 585-615.

Speklé, R. (2001). Explaining management control structure variety: a transaction cost economics perspective. Accounting, Organization and Society, 26(4-5), 419-441.

Tamarit, M. C. (2002). Variables que influyen en el diseño, implantación y control del sistema de costes y gestión basado en las actividades. Estudio de un caso. Tesis Doctoral. Universidad de Valencia, España.

Tomkins, C. (2001). Interdependences, trust and information in relationship, alliances and network. Accounting, Organization and Society, 26(2), 161-191.

Van der Meer-Kooistra, J., & Vosselman, E. (2000). Management control of interfirm transactional relationships: the case of industrial renovation and maintenance. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 25, 51-77.

Van der Meer-Kooistra, J., & Vosselman, E. (2006). Research on management control of interfirm transactional relationships: Whence and whither. Management Accounting Research, 17(3), 227-237.

Vosselman, E., & Van der Meer-Kooistra, J. (2009). Accounting for control and trust building in interfirm transactional relationship. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34, 267-283.

Vélez, M. L., Sánchez, J. M., & Álvarez, C. (2008). Management control system as inter-organizational trust builders in evolving relationships: Evidence from a longitudinal case study. Accounting, Organization and Society, 33(7-8), 968-994.

Williamson, O. E. (1975). Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications. New York: Free Press.

Williamson, O. E. (1981). The economics of organization: the transaction cost approach. American Journal of Sociology, 87, 548-577.

Yin, R. K. (1989). Case study research: Design and methods. London: Sage Publication.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case Study Research. Applied Social Research Methods. Third Edition. London: Sage Publications.

Yin, R. K. (1998). The Abridge Version of Case Study Research. In: Bickman, L., & Rog, D. J. (Eds.). Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods. London: Sage. Publications.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: design and methods. Fifth Edition. CA: Sage.

Zaheer, A., & Venkatraman, N. (1995). Relational Governance as an Inter-organizational Strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 16(5), 373-392.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Thierry Allègre, François Fulconis, Gilles Paché. (2018). Multidisciplinary Approaches to Service-Oriented Engineering. Advances in Computer and Electrical Engineering. , p.1. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-5951-1.ch001.

2. Pranas Žukauskas, Jolita Vveinhardt, Regina Andriukaitienė. (2018). Management Culture and Corporate Social Responsibility. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.70636.

3. Karen J. Agudelo Cotes, Diana C. Bedoya Gómez. (2021). Riesgos de adaptación en franquicias: herramientas de contabilidad de gestión para mitigarlos. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 26(95), p.832. https://doi.org/10.52080/rvgluz.27.95.24.

4. Larissa Dalla Corte Euzebio, Amanda Manes Koch, Valdirene Gasparetto. (2024). Práticas de Precificação e Desempenho Relacional em Franquias: Estudo no Setor de Alimentos. Contabilidade Gestão e Governança, 27(2), p.221. https://doi.org/10.51341/cgg.v27i2.3233.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2015 Innovar

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.