Language Testing in Colombia: A Call for More Teacher Education and Teacher Training in Language Assessment

Palabras clave:

Teachers’ perceptions about classroom assessment, assessment use, assessment training (en)Descargas

Language Testing in Colombia: A Call for More Teacher

Education and Teacher Training in Language Assessment

Evaluación de idiomas en Colombia: un llamado a mejorar la formación

y capacitación de profesores

Alexis A. López Mendoza*

Ricardo Bernal Arandia**

*Universidad de los Andes, Colombia

higareda87@hotmail.com

Address: Calle 18A No. 0-19, Casita Rosada Piso 2. Bogotá, Colombia.

**Universidad Piloto de Colombia, Colombia

ginamandarina@live.com

Address: Carrera 9 No. 45A-44, Área Común de inglés. Bogotá, Colombia.

This article was received on April 30, 2009 and accepted on June 19, 2009.

Classroom assessment is an integral part of the language learning process and a powerful informed

decision-making tool. Unfortunately, not many language teachers in Colombia are trained to make

assessment decisions that will engage and motivate students and, as a result, enhance learning. In

this article, we present the results of a study that examines teachers' perceptions about language

assessment and the way they use language assessments in their classroom. The findings suggest that

there is a significant difference in the perceptions that teachers have depending on the level of training

they have in language assessment. Thus, we highlight the importance of providing adequate training in language assessment for all prospective language teachers in Colombia. Key words: Teachers' perceptions about classroom assessment, assessment use, assessment training La evaluación en el aula es parte integral del proceso de aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera y

una herramienta poderosa para la toma de decisiones informadas. Infortunadamente, no muchos

profesores de lenguas en Colombia tienen formación para tomar decisiones que permitan que el

estudiante participe y esté motivado y, como resultado, promuevan el aprendizaje. En este artículo

presentamos los resultados de un estudio que examina las percepciones de los profesores de

lenguas sobre la evaluación y la forma en que la usan en el aula. Los resultados sugieren que existe

una diferencia significativa en la percepción que tienen los profesores, dependiendo del nivel de

formación que tienen en evaluación en lenguas. Por lo tanto, resaltamos la importancia de formar

adecuadamente en evaluación a los futuros profesores de lenguas extranjeras en Colombia. Palabras clave: Percepciones de los docentes sobre la evaluación en el aula, uso de evaluaciones, formación en evaluación Introduction Reynolds, Livingston, & Willson (2006) argue

that while many teachers love teaching, many

are not very interested in assessing students. As

a result, teachers tend to have a negative view of

assessment. More often than not, this negative

view stems from personal experiences. Terms

such as assessment, testing and evaluation usually

have a negative connotation as they are associated

with anxiety, stress, pressure or failure. Moreover,

tests play a powerful role in the lives of language

learners (Hamp-Lyons, 2000; Shohamy, 2001).

They provide information about both student

achievement and growth, but tests are also used to

provide rewards or sanctions for schools, teachers,

and students. For instance, tests are used to

determine who passes or fails a course, to control

discipline, to threaten students, among other

things (López, 2008a). This is in part why so many

people have a negative view of assessment. Something that could help minimize this negative

perception is to understand the differences

found in assessment, testing and evaluation. Assessment

is "a term often used interchangeably

with testing; but also used more broadly to encompass

the gathering of language data" (Davies

et al., 1999, p. 11). In other words, an assessment

is any systematic procedure to collect information

about students. This information is then interpreted

and used to make decisions and judgments

about the teaching-learning process. Testing, on

the other hand, is simply one way to assess, so

it can be described as a procedure to collect and

interpret information using standardized procedures

(American Educational Research Association

[AERA], American Psychological Association

[APA], & National Council on Measurement in

Education [NCME], 1999). Finally, evaluation can

be described as a "systematic gathering of information

in order to make a decision" (Davies et al.,

1999, p. 56). All these terms combined describe the

classroom assessment process. Teachers gather information

about what students know and can do;

they interpret this information and make decisions

about what to do next. Sometimes they quantify

this data to assign grades and then make judgements

based on them (e.g. pass/fail). What we, the

authors, have learned from our experiences is that

some teachers usually collect information at the

end of the process and therefore the assessment

cannot be used to enhance learning. Furthermore,

what some teachers lack the most is the ability to

use and interpret this information to guide the

decision-making process. Another aspect that needs to be mentioned here

is that the assessment component is recognized

as an essential part of the curriculum, but it is

the area in which many teachers express a lack of

confidence and claim the least knowledge (Nunan,

1988). Moreover, teachers commonly conceive

assessment as an isolated activity (separate from

teaching); equate assessment to simply giving a

grade or score, and view assessment as a summative

process rather than an ongoing process (Pérez,

Guerra, & Ladrón, 2004).

Problem

In our experience we have found that in some language classrooms, assessment is not a continuous process and it tends to be more summative than formative, in the sense that the only feedback students get is their grades (López, 2008b). When we observe foreign language classrooms, more often than not we notice that assessment is generally not used appropriately. Likewise, we find that language testing is not given the importance it should have. An example of this is that some teacher education and teacher-training programs in Colombia do not offer extensive training in language assessment. As a result of this lack, tests and testing systems are often subject to abuse because test scores and test interpretations are put to a host of different uses (Hamp-Lyons, 1997). Thus, tests are frequently used unethically for purposes other than those they were intended for originally and do not facilitate the language learning process. Previous studies about language testing in Colombia have highlighted the need for more research as regards the use of assessment practices in the Colombian context (e.g. Arias & Maturana, 2005; Rodríguez, 2007).

During the 2009 Language Testing Research Colloquium (LTRC), the President of the International Language Testing Association (ILTA) made a public call for more work (research, publications, conferences, workshops) on language assessment in Africa and Latin America. We believe this applies specifically to Colombia. For instance, there are very few presentations about language testing in national conferences. In last year's ASOCOPI conference there was only one presentation out of 57 (1.8%) about language testing, and in this year's ELT Conference there were only three presentations out of 75 (4%). The number of publications on language testing is not very high either. In the last four volumes of the PROFILE journal, only one article about language testing has been published (Muñoz & Álvarez, 2008). In the last six volumes of the Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, only four articles have been published (López, 2002; Muñoz et al., 2003; Quintero, 2003; Rodríguez, 2007). In the last 10 volumes of Íkala, only five articles have been published (Arias & Maturana, 2005; Barletta & May, 2006; Frodden, Restrepo & Maturana, 2004; Muñoz et al., 2006; Murphy, 2002).

Therefore, we feel we need to begin a conversation about the role of language testing in the classroom and in the language learning process. This is why it is critical to examine the perceptions that English language teachers have about the purpose of assessment, the use and interpretation of assessments and the impact that these have on the educational system and individuals. Research about teachers' perceptions of assessment is important because teachers' conceptions of teaching, learning, and curricula have a strong impact on how teachers teach and what students learn or achieve (Brown, 2002). The main goal of this article is to create awareness among the language teaching community in Colombia about the importance of adequately and effectively using assessments in the classroom to promote language learning. In particular, we want to focus on these two research questions:

- What perceptions do Colombian English language teachers have about classroom assessment?

- How are Colombian English teachers currently using language assessment in the classroom?

Literature Review

Classroom Assessment

Classroom assessment refers to a wide variety of strategies employed by teachers to get feedback from students about how they are experiencing the learning process (McMillan, 2003). Classroom assessments are also known as teacher-made assessments or alternative assessments (Hughes, 2003). As the name implies, teacher-made assessments are assessments made by a teacher or group of teachers for a specific set of instructional outcomes for a particular group of students. Alternative assessments, on the other hand, are broadly defined as any assessment method that is an alternative to traditional paper-and-pencil tests and requires students to demonstrate the skills and knowledge that cannot be assessed using a multiple-choice or true-false test (McNamara, 1997). Classroom assessment seeks to reveal students' critical-thinking and evaluation skills by asking them to complete open-ended tasks that often take more than one class period to complete. Some examples include portfolios, experiments, interviews, oral presentations, demonstrations, projects or exhibitions.

Assessment practices are currently undergoing a major paradigm shift mainly because of the emphasis on standardized testing and its perceived shortcomings (Hamayan, 1995). Alternative assessments were proposed as a response to large-scale assessment instruments with the idea that they would enable educators to attend to differences in learners, address learning over a period of time, and include communicative performances in a variety of ways. Some of the most commonly used alternative assessment instruments or procedures are writing samples, journals, portfolios, classroom projects, and interviews (Brown & Hudson, 1998).

Wiggins (1992) advocated for building higher order thinking skills in both instruction and assessment to measure students' ability to solve real problems. Chamot & O'Malley (1994) developed an approach that combines assessing thinking skills with language learning skills and content learning, so students would learn how to learn in an academic environment through English. Similarly, Short (1993) discusses the need for better assessment models for instruction where content and language instruction are integrated. She describes examples of the implementation of a number of alternative assessment or approaches such as checklists, portfolios, interviews and performance tasks.

Among some of the advantages we find in the use of alternative assessments are that they are more integrative than traditional tests, are more easily integrated into the classroom, provide easily understood information, are more responsive to each individual learner, promote learning and enhance access and equity in education (McNamara, 1997). Hamayan (1995) also points out that alternative assessments usually are low-stakes in terms of the consequences and supposedly have beneficial washback effects. Alderson & Wall (1993) define washback as the effects that tests have on teaching and learning. And unlike scores on large-scale assessments, alternative assessments are useful with English language learners because they can provide a multidimensional perspective of student progress and growth over time (O'Malley & Valdez Pierce, 1996). Alternative assessments also help make assessment an important component of the teaching-learning process (Cárdenas, 1997). Among some of the disadvantages we find in the use of alternative forms of assessments are that they are not easy to administer and score, are time consuming, and lack consistency in scoring (Hamayan, 1995). So, their use does not guarantee that these assessment procedures are necessarily valid and reliable. By valid we mean that the interpretations we make based on test scores are appropriate and by reliable we mean that tests are scored consistently (Bachman & Palmer, 1996).

Brown & Hudson (1998) present a critical overview of alternative assessment approaches. They point out that most of the research on alternative assessments are simply descriptive and persuasive in nature and are based on research on empirical studies examining the advantages and disadvantages of the alternative approaches to assessment. They claim that many studies, which advocate for the use of alternative assessments, present their value and validity without providing any evidence to support their claims. Their main point is that these alternative assessment instruments need to also be reliable and valid. Therefore, there is also a need for more research examining how these alternative assessment instruments are used and interpreted. More research is also needed to examine how alternative assessment procedures can be used more consistently and how we can use them to enhance teaching and learning.

Uses and Consequences of Tests

According to Shohamy (2001), tests are very powerful instruments Tests are powerful because they have the power to inform and the power to influence (Li, 1990). They have the power to inform because they provide feedback and they also have the power to influence because they often force teachers and students to do things they would not otherwise do. But tests are even more powerful when they are used as the only indicator for determining the future of English language learners (Spolsky, 1997).

Tests also serve a number of functions in society (Wall, 2000). For instance, Shohamy (1998) explains that tests are used, among other things, to define membership; to classify people; for developing curricula and textbooks, to determine criteria for success and failure; for power and control; and to influence teaching and learning. Now there is a widespread use of language assessment as an instrument in government policy (Davies, 1997; Shohamy, 2001). Assessment reform is sometimes used as a means for external control of schools and stems from a distrust of teachers (Darling-Hammond, 1994). Language tests are also used as gatekeeping instruments (Spolsky, 1997). That is, tests are often used as a means of political and social control. Potentially, tests can provide valuable data for gatekeeping decisions, but they should not be used as the only instrument to achieve these decisions (Spolsky, 1997). Spolsky urges that "we must make sure that gatekeeping processes are under human and not automatic control" (p. 6).

There has also been, in the language testing community, an increase in recognizing the social and political context of testing. Hawthorne (1997) claims that the main purpose of many tests is largely political. In fact, many of the testing systems in the world are mostly political activities and show that there is a close relation between testing and politics and that there are often political reasons behind education reform initiatives. Messick (1989) claims that tests are closely connected to a whole set of political and social values that affect the teaching, learning, curriculum, materials, politics, social classes and knowledge. But these political reasons are often in conflict with using tests to provide feedback about the learning process (Brindley, 1998). Messick (1989) argues that politicians need to consult with educators about such initiatives. This means that policy makers need to collect information about schools' needs and realities directly from teachers before they impose new educational policies.

Unfortunately, tests and testing systems are subject to abuse because test scores and test interpretations are put to a host of different uses (Hamp-Lyons, 1997). For this reason, Shohamy (2001) has developed a notion of critical language testing (CLT) which "implies the need to develop critical strategies to examine the uses and consequences of tests, to monitor their power, minimize their detrimental force, reveal the misuses, and empower the test takers" (p. 131). Shohamy (2001) uses the term 'test takers' to refer to any stakeholder group that is directly affected by the outcome of a test (e.g. schools, teachers, students, parents). Critical language assessment looks at the social, cultural and political context of assessment and challenges the fairness of language assessment (Pennycook, 2001).

Therefore, it is very important to examine how teachers use and interpret language tests in their classrooms and the consequences that they have. We believe that the lack of adequate training in language testing is one of the reasons some Colombian English language teachers are not able to monitor the consequences (intended or unintended) of their tests. Thus, it becomes particularly important in understanding how classroom assessments are going to be used (or misused) and interpreted (or misinterpreted).

Methodology

Participants

Eighty-two English teachers participated in this study. We used two sampling techniques to select our participants. First, we used purposeful sampling to select key participants. According to Patton (1990), "the purpose of purposeful sampling is to select information-rich cases whose study will illuminate the questions under study" (p. 169). We established the following criteria to select key participants: 1) teachers currently teaching English in a Colombian institution, and 2) teachers who were willing to participate in the study.

We made a list of teachers who we thought would be willing to participate in this study by completing an online qualitative survey. Once we had identified some key potential participants, we contacted them via e-mail. The rest of the participants were selected through a snowball sampling technique (Patton, 1990). This technique "identifies cases of interest from people who know people who know people who know what cases are information-rich, that is, good examples for study, good interview subjects" (Patton, 1990, p. 182). We asked all the teachers to identify other key potential participants that they felt would be willing to participate in this research study.

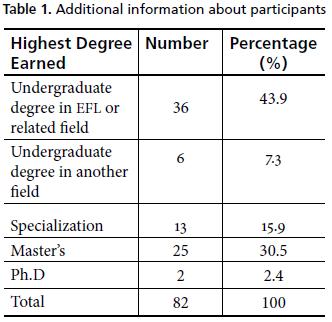

All the participants currently teach English at different levels (primary school, secondary school, university, technical institutes or language institutes). Teachers' experience ranges from 3 to 17 years. Only 32 of the participants have had previous training in language assessment. Twentyseven of them had formal training in graduate programs (specialization, master's or doctoral program). The other five teachers had received training through certificate programs such as ICELT, TKT or IELTS, or through workshops and seminars. More information about teachers is presented in Table 1 below.

Data Collection

Online Survey

This research study adheres to the assumption that "the perspective of others is meaningful, knowable, and able to be made explicit" (Patton, 1990, p. 278). Therefore, we conducted a qualitative online survey to gather information from teachers in Colombia (See Appendix 1). Through the survey we wanted to obtain the participants' perspectives, experiences and concerns (Lincoln & Guba, 1985), in this case about language assessment. This survey consisted of two parts. The first part was designed to elicit background information (e.g. educational background, teaching experience) about the participants and information about the teachers' training (pre-service and in-service) in language testing. The second part was designed to elicit information about how they felt about assessment, how they used assessments, how they scored the assessments and how they provided feedback to their students. All of this information allowed us to answer the two research questions we stated earlier.

University Programs

We downloaded curricula from 27 undergraduate programs and seven graduate programs aimed at training English language teachers in Colombia. We selected public and private institutions all over the country to represent the diversity in programs. Undergraduate programs included programs such as "Licenciaturas" in Modern Languages, English, Spanish and English, English and French, Philology, or Bilingual Education. Graduate programs included both specialization programs and master's programs in areas such as Autonomous Learning in EFL, Applied Linguistics, Didactics in English Teaching or Bilingual Education. These documents provided information about the number of language assessment courses offered in Colombian institutions.

Data Analysis

The responses to the open ended questions were analyzed through a process of coding. These codes were not pre-set and emerged from the data collected as issues and ideas, which were important and relevant to the study. According to Dey (1993), a natural creation of codes occurs with "the process of finding a focus for the analysis, and reading and annotating the data" (p. 99). Consequently, we looked at all the data collected to search for meaningful patterns (Patton, 1990). As part of the data analysis, we examined similarities and differences between perceptions from teachers with training in language assessment and teachers without training. We were also able to find tendencies in language assessment practices. Conversely, the university programs were analyzed using enumeration. That is, we simply read each program and identified courses related to language assessment and counted the number of courses and number of institutions.

Findings and Discussion

Teachers' Perceptions about Language Assessment

In this study, we found that there was a significant difference between the perspective of teachers who have had formal training in language assessment and those who have not. Trained teachers tend to view assessment more as an integral part of instruction and as a powerful tool to guide the learning process. For instance, one of the teachers with training in language assessment stated that he uses assessments "to keep track of the process, to measure achievement and to provide feedback". Likewise, another participant stated that she uses "assessment for learning". These statements suggest that some teachers have a positive view of assessment. In this perception, assessment is used to gather information about what the students know and can do. Then this information is interpreted to make decisions about teaching and learning. But the most important aspect is that this information is shared with the students so that they can all take steps to improve language learning. Among the most important positive views we found about language assessment are the following:

- Assessment as a tool to align learning and instruction – "I also use the assessments to redirect my classroom practice" "I use assessments to evaluate my methodology".

- Assessment as a tool to monitor learning – "to see the process of my students, their strengths and weaknesses".

- Assessment as a tool to aid in communicating with students – "to test students to know if they are improving or not in class and be able to give them better feedback".

- Assessment as a tool to empower students – "to encourage learners to study material covered in the course".

We also found that teachers with no training (pre-service or in-service) in language assessment tend to have a more negative view of language assessments. In this view, assessment is simply used a means to give a grade or to make judgments about the students, but not as a strategy to enhance learning. For example, some of the teachers, who have not had formal training in language assessment, stated that assessments are used "to get grades that I have to submit to the institution". On a similar note, another teacher expressed that assessments are "tools to determine passing or failing". From these statements, we can infer that assessments are simply equated with grades. This implies that grades are the only feedback students get. Also, many teachers do not see the added value of assessment and only assess because they are required to do so. Among the most noticeable negative views we found about language assessment are the following:

- Assessment as a summative process – "to generate a quantitative grade".

- Assessment as a mandate – "to get grades that I have to submit to the institution".

- Assessment as an instrument of power and control – "to force students to study what I teach in class".

We believe that the negative view of assessment that some teachers hold stems from a lack of adequate training in language assessment. For instance, 45 out of 48 teachers (93.8%) who had a negative view of assessment indicated that they had neither taken an assessment course in college nor had received any type of training in assessment (e.g. workshops, conferences, in-service training). On the contrary, 32 out of 34 teachers (94.1%) who had a more positive view of assessment had taken at least a course in assessment, had received language teaching training at work, or had attended a workshop on language testing.

Moreover, from our analysis of the university programs, we found that very few universities with education programs for teachers offered courses on language assessment or assessment in general. In the analysis, we found that out of 27 undergraduate programs only seven offered a course in evaluation (See Table 2). Some institutions have elective courses, but we were unable to determine what types of courses are offered. Still, even if elective courses on language assessment are offered, there is no guarantee that all prospective teachers take these courses. We did find that these training programs for teachers offered several methodology courses. Although it is possible that some of these courses have a segment on language assessment, we feel more training is needed.

From Table 2, we can see that only two public universities with education programs for teachers offer courses on language assessment. This is worrisome because the majority of the English teachers in Colombia are trained in these kinds of institutions. On the other hand, we found that five private universities with education programs for teachers offered a course on language assessment. This is a very promising finding in the sense that they are preparing prospective teachers to design, use and interpret assessments, and could contribute to creating a more positive view of assessment as well as starting a culture of using assessments to improve instruction. But in general, these results highlight the need for more training in language assessment in Colombian education programs for teachers.

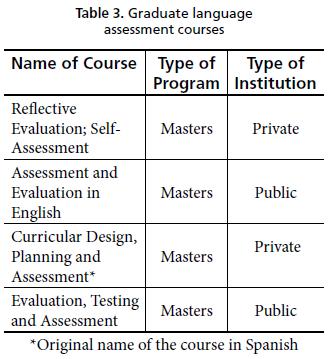

At the graduate level, we found that all the master's programs related to English teaching are offering at least a course in language assessment (See Table 3). This is also promising because all the students taking these courses will have an opportunity to apply this knowledge in their teaching and, hopefully, help their students and fellow colleagues develop a more positive view of assessment. Unfortunately, the number of teachers who actually complete a master's program in Colombia is not very high. So we need to emphasize the importance of offering language assessment courses at the undergraduate level. Language assessment courses are a professional development space for in-service teachers' critical reflection upon their beliefs and practices regarding testing, assessment and evaluation (Quintero, 2003). Moreover, from our analysis of programs, we found three specialization programs related to English teaching in Colombia, but none of them offer a course in language assessment. As specialization programs become more popular, especially for English teachers in primary and secondary public institutions in Colombia, it is imperative that these programs also focus on language assessment.

Using Language Assessments

We were also interested in gathering information about how English teachers in Colombia use language assessments in the classroom. From the online qualitative survey we found that 71 teachers usually assess at the end of a unit or course. The other 11 teachers argued that they tend to assess regularly, at least once a week. Sixty-four teachers reported that they tend to use traditional tests (e.g. paper and pencil, multiple-choice, fill in the blank types of tests). They also tend to use final exams and quizzes. Only a few teachers (18) reported using authentic classroom assessments such as essays, presentations, interviews and others.

In terms of scoring, 59 teachers explained that they scored tests by assigning numbers or letters. The other 23 teachers used qualitative descriptors to score their students' tests. Most of the feedback is provided at the end of the teaching-learning process and is usually given by assigning a grade. The feedback is usually provided by returning the marked exams. Sixty-three teachers reported using mostly objective scoring in the form of scoring keys. A few teachers (19) reported using subjective scoring methods such as scoring rubrics. In general, assessment seems to be more summative than formative. It is important for teachers to learn to provide better feedback to students. In order for classroom assessment to be effective, teachers need to provide immediate, relevant and ongoing feedback in their assessments. The feedback needs to be descriptive and it should focus on students' strengths and limitations and inform them about possible ways to reinforce or enhance learning (López, 2008b).

From the responses we got on the online survey, we feel that teachers also need to empower the students. Students should be the central focus of any assessment process, more so in classroom assessment (López, 2008b). So teachers need to make sure that students take ownership of their learning. But students also need to accept this responsibility and take control of this process. The best way to empower students is to share all the information about assessments with them, including what, how and when they are going to be assessed, how the assessment is going to be used and interpreted, and what decisions are going to be made based on the test. Also, we need to educate students on using self-assessment and peer-assessment as a way to monitor their learning process.

Language teachers should also be concerned with issues of ethics (Davies, 1997). Ethical issues deal with how tests are used and how tests results are interpreted. Language tests generally used ethically questionable and unstated political purposes that are often quite distinct from their stated purposes (Shohamy, 2001). For example, tests are sometimes used as gatekeepers or instruments to exercise power and control (Spolsky, 1997).

In the last two decades or so there has been a rise in ethical awareness in language testing. This has resulted in an increased interest in considering all the participants in the testing process. McNamara (1998) explains that the purpose of ethical language testing is to examine the role of language testers, the power they hold, the principles and structures in the use of that power, and the limits of that power. In a way, ethical language testing puts the burden of responsibility onto the tester (Hamp- Lyons, 1997).

Language teachers should set themselves high standards when they assess their students and take every step to ensure that these standards are upheld. By standards we refer to "a code of professional practice or set of professional guidelines which could cover all stages of test development, from initial construction, through trialing and on to operational use" (Davidson, Turner & Huhta, 1997, p. 303). This definition is similar to Stansfield's (1993) suggestion that language testers need to define ethics as a standard of appropriate professional practice and as a set of moral obligations. Similarly, Davies (1997) calls for a professional morality among language testers (i.e. English language teachers) to protect both the individuals from misuse and abuse of tests and to protect the profession's members.

Corson (1997) argues that ethical principles for testing should be concerned with three important issues: That everyone is treated equally; that everyone is respected; and that everyone benefits from the test. As a reaction to all these ethical concerns, the Code of Ethics of the International Language Testing Association (ILTA, 2000), developed nine principles. The last principle states that "language testers shall regularly consider the potential effects, both short and long-term, on all stakeholders of their projects, reserving the right to withhold their professional services on the grounds of conscience" (p. 6). But Davies (1997) argues that language testing professionals "have a hard task to influence other stakeholders, particularly the contracting stakeholders since the only real influences on them are their own prejudices and personal experiences" (p. 338). Language testers should, to some extent, be at least accountable for ensuring that the information they gather is used for ethical purposes. For instance, when people use language tests to exercise control rather than to provide information about the language learning process, they are being unethical (Shohamy, 2001).

Moreover, Shohamy (1997) claims that language tests which contain content or employ methods which are not fair to all test-takers are not ethical, and discusses ways of reducing various sources of unfairness. She also claims that tests should be used to provide information on proficiency levels and not to exercise control and manipulate stakeholders. It is crucial that we examine ethical issues in the assessment of English language learners in Colombia. We need to examine the ways assessment instruments are used and the consequences that are brought about with such uses.

Final Thoughts

In this study, we presented information about teachers' perspectives on language assessment. We found that there seems to be a correlation between language assessment training and perceptions about language assessment. We believe that proper education and training of teachers will help change teachers' perceptions about language assessment. If teachers have a positive view of assessment, they will be able to select or design appropriate assessment procedures for their context and students that will allow the assessments to provide useful information.

We also presented information about how teachers use language assessment in the classroom. We found that there is a tendency to use traditional assessment instead of alternative assessment. Moreover, we found that the majority of the feedback provided is in the form of a grade and is usually done at the end of the process. So from the finding in this study, we can argue that classroom assessment in English teaching in Colombia tends to be more summative than formative.

The findings of this study imply that teachers need to be familiar with different types of language assessments and the type of information they provide (Hughes, 2003). Another concern is for teachers to use assessment procedures that are both valid and reliable. By valid, we mean assessment procedures that provide accurate information about what is being measured. So a test is valid if the inferences we make based on test scores are appropriate (Messick, 1989). And by reliable, we mean assessment procedures that produce consistent scores regardless of the situation or the context in which the assessment procedure is conducted (Bachman & Palmer, 1996). But the literature also shows that there is a lack of appropriate, valid, and reliable assessment measures for English language learners (Valdés & Figueroa, 1996). Since we assess students for many different purposes, we need to examine whether or not the assessment instruments and procedures that are commonly used are valid and used appropriately. Davies (1997) claims that in order for a test to be fair, it needs to involve all stakeholders in the assessment process. It is crucial for test makers to interact with other groups of stakeholders so they can better understand the assessment culture and context in which a test functions. We also need to conduct studies analyzing the real purposes of tests and compare them to the actual purposes they are used for. Moreover, we need to examine how these assessment practices affect the lives of students and their families (López, 2008a). There is also a need for more studies examining the impact tests have on language learning and on language learners.

We believe that the outcomes of research studies, such as the one we present here, may stimulate administrators, pre-service and in-service teachers, and the educational community as a whole, to update their professional development and improve their assessment practices to enhance the quality of language education and students' motivation for learning. For now, it is important to remember that assessment is not simply measuring or assigning grades. We feel that it is more motivating and less threatening for language teachers to begin talking about assessment for learning rather than assessment of learning. We also think more research is needed on how tests are developed and how all the stakeholders are involved in this process, especially when this research takes into consideration the uniqueness of the Colombian context. Finally, we want to raise the issue of professionalization of the field of language assessment in Colombia. This implies that both teachers and prospective teachers need more training in language assessment. We feel that the responsibility to train language teachers in how to develop, use, score and interpret language assessments lies in higher education institutions that have education programs for teachers, in the institutions that have language programs and in the language teachers themselves. It is imperative that all prospective teachers take at least a course in language testing before they start teaching, and should strive to better themselves through in-service training, conferences, workshops and so forth to create a language assessment culture for improvement in language education.

References

Alderson, J. C., & Wall, D. (1993). Does washback exist? Applied Linguistics, 14(2), 115-129.

American Educational Research Association [AERA], American Psychological Association [APA], & National Council on Measurement in Education [NCME]. (1999). Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington D.C.: American Educational Research Association.

Arias, C. I., & Maturana, L. M. (2005). Evaluación en lenguas extranjeras: discursos y prácticas. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 10(16), 63-91.

Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. S. (1996). Language testing in practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barletta, N., & May, O. (2006). Washback of the ICFES Exam: A case study of two schools in the Departamento del Atlántico. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 11(17), 235-261.

Brindley, G. (1998). Assessment and reporting in language learning programs: Purposes, problems and pitfalls. Language Testing, 15, 45-85.

Brown, G. (2002). Teachers' conception of assessment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. The University of Auckland, ResearchSpace@Auckland. Retrieved June 15, 2008, from Web site: http://hdl.handle.net/2292/63

Brown, J. D., & Hudson, T. (1998). The alternatives in language assessment. TESOL Quarterly, 32(4), 653-675.

Cárdenas, R. (1997). Exploring possibilities for alternative assessment in foreign language learning. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 2(1-2), 57-73.

Chamot, A. U., & O'Malley, J. M. (1994). The calla handbook: Implementing the cognitive academic language learning approach. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Corson, D. (1997). Critical realism: An emancipatory philosophy for applied linguistics? Applied Linguistics, 18(2), 166-188.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1994). Performance-based assessment and educational equity. Harvard Educational Review, 64(1), 5-30.

Davidson, F., Turner, C. E., & Huhta, A. (1997). Language testing standards. In C. Clapham, & D. Corson (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and Education, Volume 7: Language testing and assessment (pp. 303-311). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer.

Davies, A. (1997). Demands of being professional in language testing. Language Testing, 14(3), 328-339.

Davies, A., Brown, A., Elder, C., Hill, K., Lumley, T., & McNamara, T. (1999). Dictionary of language testing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dey, I. (1993). Qualitative data analysis. London: Routledge.

Frodden, M. C., Restrepo, M. I., & Maturana, L. (2004). Analysis of assessment instruments used in foreign language teaching. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 9(15), 171-201.

Hamayan, E. (1995). Approaches to alternative assessment. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 15, 212-226.

Hamp-Lyons, L. (1997). Washback, impact and validity: Ethical concerns. Language Testing, 14(3), 295-303.

Hamp-Lyons, L. (2000). Social, professional and individual responsibility in language testing. System, 28, 579-591.

Hawthorne, L. (1997). The political dimension of English language testing in Australia. Language Testing, 14(3), 248-260.

Hughes, A. (2003). Testing for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

International Language Testing Association [ILTA] (2000). Code of Ethics. Retrieved on March 9, 2009 from Web site: www.dundee.ac.uk/languagestudies/ ltest/ilta/code.pdf

Li, X. (1990). How powerful can a language test be? The met in China. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 11(5), 393-404.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

López, A. (2002). Washback: The impact of language tests on teaching and learning. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 4, 50-63.

López, A. A. (2008a). Potential impact of language tests: Examining the alignment between testing and instruction. Saarbrucken: VDM Publishing.

López, A. A. (2008b). The role of language testing in the classroom. Invited paper presented at the Fourth Language Forum. Valledupar, Colombia.

McMillan, J. H. (2003). Understanding and improving teachers' classroom assessment decision making: Implications for theory and practice. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 22(4), 34-43.

McNamara, T. F. (1997). Performance testing. In C. Clapham, & D. Carson (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education, Volume 7: Language testing and assessment (pp. 131-139). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

McNamara, T. F. (1998). Policy and social considerations in language assessment. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 18, 304-319.

Messick, S. (1989). Validity. In R. L. Linn. (Ed.), Educational measurement (3rd ed.) (pp. 13-103). New York: Macmillan.

Muñoz, A., & Álvarez, M. (2008). Preliminary evaluation of the impact of a writing assessment system on teaching and learning. PROFILE. Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 9, 89-110.

Muñoz, A., Álvarez, M., Casals, S., Gaviria, S., & Palacio, M. (2003). Validation of an oral assessment tool for classroom use. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 139-157.

Muñoz, A., Mueller, J., Alvarez, M., & Gaviria, S. (2006). Developing a coherent system for the assessment of writing abilities: Tasks and tools. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 11(17), 265-307.

Murphy, D. (2002). El desarrollo de una cultura de la evaluación. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 7(13), 75-85.

Nunan, D. (1988). The learner centred curriculum. A study in second language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O'Malley, J. M., & Valdez Pierce, L. (1996). Authentic assessment for language learners: Practical approaches for language learners. Reading, ma: Addison-Wesley.

Patton, M. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Pennycook, A. (2001). Critical applied linguistics: A critical perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Pérez, M., Guerra, R., & Ladrón, C. (2004). El proceso de evaluación del aprendizaje en la asignatura de inglés I en la uclv. Revista Pedagogía Universitaria, 9(3), 96-104. Cuba. Retrieved on April 5, 2008 from Web site: www.upsp.edu.pe/descargas/Docentes/Antonio/revista/04/3/189404306.pdf

Quintero, A. (2003). Teachers' informed decision-making in evaluation: Corollary of elt curriculum as a human lived experience. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 122-134.

Reynolds, C. R., Livingston, R. B., & Willson, V. (2006). Measurement and assessment in education. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Rodríguez, E. O. (2007). Self-assessment: An empowering tool in the teaching and learning EFL processes. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 9, 229-246.

Shohamy, E. (1997). Testing methods, testing consequences: Are they ethical? Are they fair? Language Testing, 14(3), 340-349.

Shohamy, E. (1998). Critical language testing and beyond. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 24(4), 331-345.

Shohamy, E. (2001). The power of test: A critical perspective on the uses of language tests. London: Longman.

Short, D. (1993). Assessing integrated language and content instruction. TESOL Quarterly, 27(4), 627-656.

Spolsky, B. (1997). The ethics of gatekeeping tests: What have we learned in a hundred years? Language Testing, 14(3), 242-247.

Stansfield, C. W. (1993). Ethics, standards, and professionalism in language testing. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 4(2), 189-206.

Valdés, G., & Figueroa, R. A. (1996). Bilingualism and testing: A special case of bias. Norwood, nj: Ablex.

Wall, D. (2000). The impact of high-stakes testing on teaching and learning: Can this be predicted or controlled? System, 28, 499-509.

Wiggins, G. (1992). Creating tests worth taking. Educational Leadership, 26, 26-33.

About the Authors

Alexis A. López Mendoza holds a Ph.D in Education from the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign. Currently, he is an assistant professor in the Center for Research and Development in Education at Universidad de los Andes (cife). His main research interest is language test development and validation.

Ricardo Bernal Arandia holds an m.b.a. (unab–itesm), a b.a. in Business Management (usta), a Specialization in University Teaching (unab), and a b.a. in Languages Teaching (uis). He has worked in Languages Education for over 18 years and is currently an English Teacher at Universidad Piloto de Colombia.

- Educational Experience. Please complete each box by indicating the degree(s) you have completed or are currently completing. Please write the area of concentration (e.g. Licenciatura en idiomas).

Undergraduate: _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Specialization:__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Master's: ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Ph.D: _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Other: ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________- Employment History. Tell us a little bit about your teaching experience.

Foreign language(s) you teach: ____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Number of years teaching: ________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Indicate grade/language levels you teach: ___________________________________________________________________________________________- Language Testing Education and Training. Please provide information about courses or workshops you have taken in language testing. Write the name of the course(s) or workshop(s) and where you took them.

Courses: _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Workshops: _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________- For what purpose(s) do you use language tests in your classrooms?

- How do you assess your students? What type of tests or instruments do you use?

- How do you score (grade) the tests or assessment instruments?

- What type of feedback do you give to your students?

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Visitas a la página del resumen del artículo

Descargas

Licencia

Los contenidos de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development son de acceso abierto y los cubre la Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional. Se autoriza copiar, redistribuir el material en cualquier medio o formato, siempre y cuando se conceda el crédito a los autores de los textos y a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development como fuente de primera publicación. No se permite el uso comercial de copia o distribución de contenidos, así como tampoco la adaptación, derivación o transformación alguna de estos sin la autorización previa de los autores y de la Editora de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Los autores conservan la propiedad intelectual de sus manuscritos con la siguiente restricción: el derecho de primera publicación es otorgado a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.