How Do EFL Student Teachers Face the Challenge of Using L2 in Public School Classrooms?

Palabras clave:

Communication strategies, EFL student teachers, L2 in the classroom, student teachers’ challenges. (en)Descargas

As an EFL Student teachers’ advisor, I had constantly perceived that they regarded using the target language with their pupils inside their classroom as a challenge. That is why I became interested in investigating how thirteen student teachers in Tunja public schools faced this issue. While participants were involved in a reflective teaching preparation model, I used field notes, interviews and their portfolios to explore their attitudes and strategies. Findings revealed that their history as learners, their teaching context and preparation influenced their decisions. Moreover, it was possible to identify the strategies they implemented to interact in English with their students.

En mi labor como tutor de estudiantes practicantes del inglés como lengua extranjera, he percibido constantemente que, para ellos, la utilización del inglés como medio de comunicación con sus estudiantes dentro de la clase es un reto. Por esta razón, me interesé por investigar cómo trece estudiantes practicantes en colegios públicos de Tunja afrontaban esta circunstancia. Mientras los participantes se involucraban en un modelo reflexivo de preparación docente, utilicé notas de campo, entrevistas y sus portafolios para explorar sus actitudes y estrategias. Los hallazgos revelan que sus decisiones fueron influenciadas por su trayectoria como estudiantes, su contexto de enseñanza y su preparación. Además, se pudieron identificar las estrategias que utilizaron para interactuar por medio del inglés con sus estudiantes.

How Do EFL Student Teachers Face the Challenge of Using L2

in Public School Classrooms?

¿Cómo enfrentan los docentes practicantes de inglés como lengua extranjera

el reto de usar una segunda lengua en las aulas de clase de la escuela pública?

John Jairo Viáfara

Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia

jviafara25@gmail.com

This article was received on June 8, 2010, and accepted on December 6, 2010.

As an EFL Student teachers' advisor, I had constantly perceived that they regarded using the target language with their pupils inside their classroom as a challenge. That is why I became interested in investigating how thirteen student teachers in Tunja public schools faced this issue. While participants were involved in a reflective teaching preparation model, I used field notes, interviews and their portfolios to explore their attitudes and strategies. Findings revealed that their history as learners, their teaching context and preparation influenced their decisions. Moreover, it was possible to identify the strategies they implemented to interact in English with their students.

Key words: Communication strategies, EFL student teachers, L2 in the classroom, student teachers' challenges.

En mi labor como tutor de estudiantes practicantes del inglés como lengua extranjera, he percibido constantemente que, para ellos, la utilización del inglés como medio de comunicación con sus estudiantes dentro de la clase es un reto. Por esta razón, me interesé por investigar cómo trece estudiantes practicantes en colegios públicos de Tunja afrontaban esta circunstancia. Mientras los participantes se involucraban en un modelo reflexivo de preparación docente, utilicé notas de campo, entrevistas y sus portafolios para explorar sus actitudes y estrategias. Los hallazgos revelan que sus decisiones fueron influenciadas por su trayectoria como estudiantes, su contexto de enseñanza y su preparación.Además, se pudieron identificar las estrategias que utilizaron para interactuar por medio del inglés con sus estudiantes.

Palabras clave: estrategias de comunicación, estudiantes practicantes de inglés como lengua extranjera, retos de estudiantes practicantes, uso de segunda lengua en el salón.

Introduction

In regard to the teaching and learning of language skills, students' exposure to constant practice is clearly a paramount condition for their mastery of these abilities. We might think that in EFL settings, where practice opportunities can be limited, teachers' use of the foreign language in classrooms is common; however, several experiences have shown me that interacting in English inside the classroom continues to be a challenge for many educators or future educators in our country.

During the EFL practicum in secondary public schools,I have often observed that most cooperating teachers do not communicate with their students in English.Other secondary and primary public school colleagues have honestly said they act similarly. Moreover, along the semester in which this study took place, I noticed that student teachers spoke mostly in Spanish or they translated almost every word they said to their students. The last situation led me to express my surprise to these prospective teachers. In turn, they revealed their reluctance to speak mostly in English to their pupils.

Student teachers thought that using more English in their classrooms could help their pupils' English learning; nonetheless, they felt unable to achieve this aim and believed their students would understand only if the English class was conducted in Spanish. They claimed pupils seemed to be lost, did not follow instructions and, as a result, their interest in lessons vanished. Many expressed their impression that most of their pupils did not want them to speak in English because of the students' lack of motivation to study the foreign language.

Using a reflective approach while guiding student teachers, I sought to explore how EFL student teachers face the challenge of using English to communicate with their pupils in class. This endeavor involved an examination of both the factors that shape participants' intentions to speak English in the classroom and the strategies they employ to communicate with their students in the target language.

This study emerged as an opportunity to contribute to the preparation of in-service and future EFL teachers. This is especially significant considering that practicum experiences were conducted in public schools where teaching can be relatively challenging. Public schools classes generally contain 40 or more students and teachers struggle with limited resources for language teaching. In addition, students' social and economic conditions pose difficulties; their need for basic conditions to live properly can cause their interest in learning to be less than a priority.

Firstly, I will contextualize my investigation in relation to EFL education theory. Secondly, I will describe the teaching practicum that relates to student teachers' preparation to face the challenge of using English in the classroom. Thirdly, I will explain the research design of the study. Finally, conclusions and pedagogical implications drawn from the data analysis will be shared.

Literature Review

Two main areas will be included in the next section: the practicum as an experience to prepare student teachers and communication in the English classroom as a vehicle to enhance language learning.

The Practicum as an Experience to Prepare Student Teachers

Along the teaching practicum, student teachers are expected to integrate their previous university education to real school contexts. However, as Capel (2001) and Velez (2003) comment in their studies,very often the practicum becomes a complex experience in which student teachers might reveal concerns about their teaching strategies.

One of the preoccupations EFL prospective teachers show refers to their communication with pupils by means of the foreign language. Melnick and Meister (2008) found out that providing efficient classroom communication along with classroom management and preparation for the course were the most notable concerns of a group of beginning teachers. Likewise, Prada and Zuleta (2005) found that a group of pre-service teachers' difficulties were connected with,among other issues, a code-switching dilemma; they doubted whether to employ English or Spanish to communicate with their students. Pre-service teachers claimed they used L1 more than the target language to prevent confusion and comprehension problems as well as to help students to feel relaxed.

In order to support student teachers as they face their concerns during the practicum, I have generally followed a reflective approach (Richards & Lockhart, 1994; Wallace, 1991). Guiding student teachers is not based on prescription but on supporting their engagement in a critical thinking process to analyze their own practices in search for solutions to difficulties and doubts (Barlett, 1990; Pollard & Tann, 1993; Rodgers, 2002).

Farrell (2007) reports a case study in which a student teacher, using such a reflective approach, realized which maxims were governing her teaching practice and adopted new and more enriching principles to support her teaching. Likewise, Viáfara (2005; 2007) noticed that by means of this approach prospective teachers evaluated their own work, constantly keeping in mind how the particularities of their situations affected their plans.As a result, the student teachers often adapted or experimented with pedagogical strategies based on their own particular teaching situation and the previous knowledge built from theory or other sources.

The EFL Classroom: Principles and Opportunities to Support Students' Language Learning

The constant use of English in the classroom is widely considered an opportunity to enhance students' foreign language learning. From a social perspective to second language learning, interactionist theories claim that"verbal interaction is of crucial importance for language learning as it helps to make the facts of the L2 salient to the learner" (Ellis, 1997, p. 244). Taking part in conversations or oral exchanges benefits learners because they realize how the second language functions and thus this realization eventually leads them to participate in these interactions successfully.

However, according to (Krashen, 1981), learning the language by means of interaction depends on to what extent the input students are exposed to is comprehensible. Additionally, scholars as Littlewood (1984, p. 59) have remarked on the relevance of that input in regard to students' immediate interests and its complexity. Achieving comprehensible input also implies, as Lightbown and Spada (1993) assert, the modification of interaction by means of conversational adjustments such as slower speech, comprehension checks or self-repetition; hence, more proficient speakers and less skilful ones can keep their verbal communication.

Studies by Seliger and Slimani (in Tsui, 1995, p. 149) evidenced that input produced spontaneously by students in conversations generated situations which implied more contact with the language and higher achievements in their learning. On the other hand,the previous assumption might be true only in some cases since other individuals seem to benefit just from listening and not actually engaging in the conversation. Interaction in the classroom can also be influenced by individual personalities as well as the actions and attitudes of their teachers and classmates, among other issues.

Likewise, the use of communication strategies can encourage or limit opportunities for interaction (Ellis,1985).Based on Tarone (1981),communication strategies are classified as paraphrasing, borrowing, employing non-linguistic signals and avoiding interaction. Of particular importance to this study is the "borrowing" strategy, which entails switching to the mother tongue. Muñoz and Mora (2006, p. 32) concluded in an investigation that such "code-switching gave learners the possibility to use their L1 with communicative purposes" since pupils could find more resources to express their feelings and clarify information. As teachers and students code-switched from English to Spanish, they developed discourse functions that involved topic switch, interjections and repetition.

To close, language learning strategies such as code-switching support students' development of linguistic and sociolinguistic competence (Tarone, 1981); they are behaviors or actions that learners employ to make language learning more successful, self-directed and enjoyable (Oxford, 1990). Among Oxford's classification of these strategies, the compensation and the social ones are closely involved in the issue addressed in this study. Part of the success learners can have when trying to interact using L1 in the classrooms depends on, as the next section discusses, how teachers guide them in this process.

The Role of Teachers in Supporting the Use of English in the EFL Classroom

The language used by educators in the classroom becomes a major source of input for foreign language learners. Teachers lead, organize and monitor activities in the classroom providing ample occasions for students to listen to or engage in dialogues with them. Since they are regarded as expert users of the target language, teachers become models to show how the language works.

Haycraft (1986, p. 11) gives relevance to the communication established in the EFL classroom between student and teacher as follows: "Students from the beginning must accustom themselves to normally spoken English". Likewise, Sánchez (2001, p. 87) explains that "the main task for teachers should be to provide learners with opportunities to communicate in all possible contexts and to avoid overwhelming them with dialogues which are not found in students' contexts"). Scholars such as Harmer (2007) explain that the way teachers talk to students resembles how parents talk to kids: adapting their speech to learners at lower levels, using physical movements and gestures, and trying to gain reassurance about the efficiency of pupils' communicative efforts by becoming sensitive to the signs of comprehension. These are skills that new teachers need to acquire.

Similarly, the emotional climate of learning situations can also affect teachers' efforts to interact with students by means of the foreign language: "In an environment where learners feel anxious or insecure, there are likely to be psychological barriers for communication" (Littlewood, 1984, p. 58). Teachers need to be sure pupils understand their speech and feel confident enough to attempt communication with their peers.

In connection with the previous issue, Bell (2005) determined that several of the most acceptable behaviors of effective foreign language teachers are related to their competent use of the target language, their use of it as the predominant means of classroom communication, their provision of opportunities for students to use the target language (both within as well as beyond the school), and their encouragement of foreign language learners to speak in the target language from the first day of class.

Hernández and Faustino (2006, pp. 217-250) found that a group of EFL teachers in Colombia considered the constant practice of English important in class; however, it was hard for them to carry out oral activities in lessons. Students' apathy, laziness,indiscipline,fear of being ridiculed and lack of commitment were all factors that compromised teachers' intentions. Furthermore, large and heterogeneous groups, low numbers of instruction hours per week as well as the lack of resources worsened the problem. In addition, pupils did not regard learning the foreign language as a valuable tool for their lives. A common characteristic in this classroom was that L1 was used in class more often than L2. Spanish was used to explain, clarify, translate and provide examples. On the other hand, English was used in short interactions: to say goodbye and hello, instructions, commands, short dialogues and questions.

Similarly, Wilkerson (2008) explored instructors' use of their L1 (English) when teaching L2 (Spanish). The researcher found that two instructors did not use or used L1 very little in class to communicate with students. Two of them usually used code-switching and one of them spoke entirely in L1 to students in the classroom. L1 was used to save time, reduce ambiguity and demonstrate authority. Instructors' use of L2 was based on their beliefs about students' skills to tolerate, solve and learn from the possible ambiguity generated as they interacted in the foreign language. Finally, the author highlighted that teachers' willingness to use the target language in the lessons might be influenced by their urgency to organize and manage their classroom.

Research Design

Qualitative research guided this study. Based on Nunan (1992),I sought to describe the phenomenon of my interest within natural conditions. I followed a process-oriented approach and my intention was to comprehend student teachers' attitudes from their perspective. I adopted the methodology of a descriptive case study. I sought to understand a phenomenon within a specific context, a unit, by revealing and interpreting its characteristics and the interrelated factors among them (Merriam, 1988). Finally, participants produced language naturalistically in classrooms, which was studied by means of interactional analysis (Nunan, 1992).

The Context and Participants in the Study

Student teachers belonged to the Modern Languages (Spanish-English) Program in a public university.They enrolled in their teaching practicum, "Práctica Pedagógica y Social," in the tenth semester of their studies and spent sixteen weeks in schools. Each one taught English for eight hours in two different classes. Their previous pedagogical preparation included, in addition to five general pedagogical research courses, lessons on Applied Linguistics, ELT Methodology I and II and Teaching Practice I. Furthermore, seven levels of five-hour, weekly "Communicative Projects" courses, English Phonetics and Grammar helped pre-service teachers to develop their proficiency in English.

The teaching practicum took place in public schools. These institutions had large classes, from 40 to 50 students in each classroom. Most courses include boys and girls. English was taught for two to three hours per week. Equipment and printed material for instructing students, in at least one school, were limited.

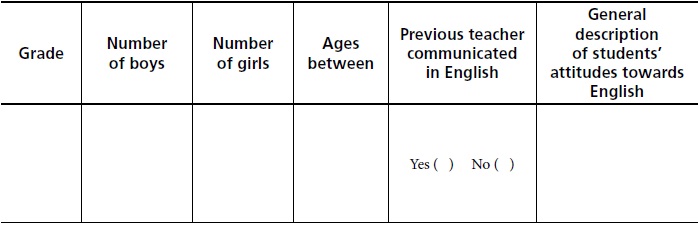

Students from social strata one to three attended these secondary schools. Some of the students lived in Tunja and others came from rural settings near the city. Their economical conditions in many cases were precarious. These students' English level was very low. The research asked participants to fill in a small form to elicit information about their classes and pupils' motivation (see Appendix 1). This source indicates that the youngest students, 6th to 8th grade, were apparently more enthusiastic to learn and, in particular, to learn English.

Student teachers counted on the support of university advisors and the school's cooperating teachers. The six cooperating teachers in these institutions were between 45 and 55 years old. They were two men and four women who to date had worked in these institutions from 15 to 25 years. Two of them had masters in English teaching while the others had specializations in various pedagogical fields. They taught English exclusively in the two institutions. The four teachers at Institution B had an intermediate English level. The two teachers at Institution A had a pre-intermediate English level. In general, these educators'methodologies included emphasis on the teaching of grammar, reading and writing skills. Four of them communicated constantly in Spanish with their pupils while two of them alternated their use of L1 and L2.

I worked with thirteen student teachers during the practicum. They were five male and eight female students. They were between 22 and 25 years of age. Most of them were originally from cities in Boyacá and one of them was from Santander. Seven of them were at School A and six at School B. Judith, Hermes, Yina and Jahir were at school A working with the same cooperating teacher. Nury, Rene and Angelina also taught at school A, but their cooperating teacher was different. The student teachers at institution B were Marlon, Lina and Ana who shared the same mentor while Camilo, Dina and Nemesis were guided by another cooperating teacher. Participants' EFL learning history was similar to the panorama described by Viáfara (2008): as secondary students, they had had a little exposure to English in EFL lessons. Likewise, teachers did not speak in English and when English was used, translation was a common practice.

Participants' English level varied. In this group,Hermes was close to a high-intermediate profi- ciency level. Marlon, Rene and Camilo were at an intermediate stage. Lina, Nemesis, Dina and Ana were in a pre-intermediate stage and Angelina, Yina, Nury, Judith and Jahir had a low-intermediate level. In general, most of them revealed problems of interference with Spanish; translation was common and excessively employed as an attempt to build their ideas to communicate in the foreign language.

Data Collection Instruments and Techniques

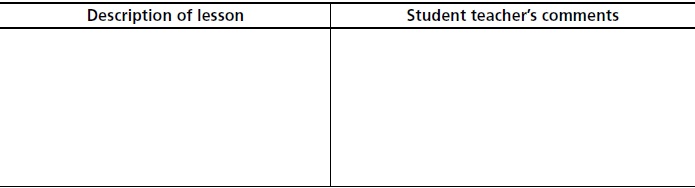

I observed each student teacher's 90-minute lessons twice during the semester and collected 26 observation forms totaling 84 pages filled with notes (see Appendix 2). Generally, participants did not know when they were going to be observed. In order to record my observation, I took ethnographic field notes (Pentimalli,2005) and paid special attention to students' use of English to communicate with their students. When I had the opportunity, I supported these notes with audio-recordings.

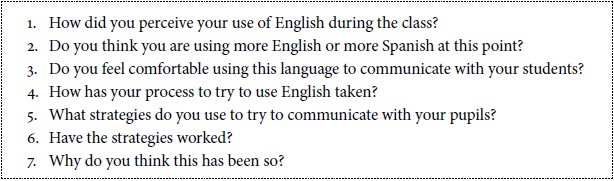

The audio-recordings of my conferences with student teachers comprised another instrument I used (Appendix 3 includes examples of the questions asked). This took place one or two days after the observed class session. I recorded participants' perceptions about their use of English in the lesson. Two talks with each participant were recorded for a total of twenty-six audio recordings.

In addition, I interviewed a group of students who attended participants' classes (Appendix 4 includes examples of the kind of questions asked). I usually asked 2 to 4 pupils of each class about the student teachers' use of English and Spanish, if they liked when their teachers spoke in the foreign language, and how they as students coped when English was used. I applied a non-structured interview (Seliger & Shohamy, 1990) in order to hold a friendly conversation with the kids. I recorded their answers, taking notes immediately after our conversation. I interviewed a total of thirty-six kids in the twenty-six classes I visited.

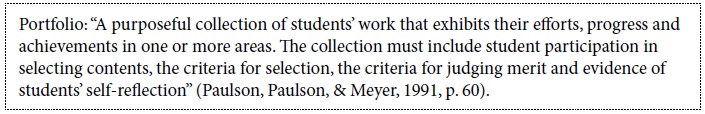

Lastly, I took into account the student teachers' portfolios (Appendix 5 includes the guidelines provided to keep the portfolio). These artifacts included their plans and formats to analyze their progress through lessons, a weekly journal to reflect upon their experiences, and reading logs that contained participants' views about how they employed theory in their practice. Finally, student teachers selected meaningful materials, activities or learning situations to reflect upon their experiences. Portfolios were shared with peers and professors to obtain feedback and exchange views. At the end of the semester, I reviewed pieces that contained participants' thoughts in regard to their use of English in the classroom.

In order to analyze the information collected, I employed techniques from grounded theory. Constantly comparing and questioning the information I collected, I established commonalities which I then labeled (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). After this initial organization and identification of data, I engaged in categorizing the concepts as I put initial commonalties together. Finally, by analyzing the relationship among the categories, I built a meaningful answer for my research questions. Additionally, validity in my findings was one of my concerns. For this reason, methodological triangulation was considered among my various sources of data (Merriam, 1988). In the next lines, the results of this study are revealed. I will use the following abbreviations to refer to the instruments from which specific pieces of evidence were taken: Field notes of classes (FNC), Transcription of a Conference (TCF), Student teachers' portfolios (STPF), Transcription of an audio recorded Class (TAC), and Notes from unstructured interviews of pupils (NPUI).

The Use of the Foreign Language in the Classroom: from Constraints to New Meanings

The first topic reveals the factors that shaped participants' intentions to speak in English to their pupils.As will be shown,at some points participants seemed not to react in relation to these factors; they felt unable to overcome the influence that some of these issues had on them. Conversely, at other times student teachers acted to reduce the effect of these circumstances; they perceived the factors as opportunities to reshape their own learning.

English in the Classroom: Beyond the Burden of an Old Culture

During participants' secondary education, Spanish was the main and almost exclusive means of communication in the EFL classroom. Lina, for example, mentioned that "I was always concerned about what I experienced at school since most of the English classes were in Spanish. I had a different expectation" (TCF). Several student teachers reproduced this same model, using Spanish as the primary means of communication, with their pupils at the beginning of the practicum. Scholars such as Richards and Lockhart (1994) and Farell (2007) have established that pre-service or in-service teachers' practices are influenced by their previous experiences as learners.

However, a few participants did have learning experiences in which their teachers spoke in English. The following extract reveals how Dina's contact with the foreign language in class, as a secondary student, has shaped her views as an initial teacher:

During these weeks, I have understood the importance of using the language inside the classroom. Maybe from my personal experience in my high school as a student... I liked very much that my teacher spoke in English in some parts of the class. It was a challenge for me. (STPF)

In addition, cooperating teachers reinforced this traditional culture of speaking Spanish in the EFL classroom. In fact, many demanded the use of L1 from these prospective teachers, asserting that pupils would not understand if student teachers talked to them in English. Yina explained:

I tried to use a little bit more of English in class, but the [cooperating] teacher asked me not to talk to them in English because they wouldn't understand. I think that creates certain predisposition and you don't explore, you don't look at students' reactions to check if they don't really understand. (TCF)

Communicative Nature of Language as a Real Practice

Student teachers' concept of what language was and how it functioned also seemed to be related to their actions in classrooms. Some of them commented that English was a communication tool for real-life purposes and looking at their lessons, I could see they tried to implement this principle. One of them said, "My purpose is that students use the language to communicate whenever they need it" (TCF, Rene). Similarly, in a study conducted by González (2008) that helped to establish teachers' concept of communicative competence and how this concept was related to their practices as English teachers, one of her participants said that "the development of communicative competence implies thinking about the students themselves as well as the way they interact in the classroom" (p. 87).

However, it seems that because students often regard English as external or irrelevant to their own lives, speaking in English with their pupils usually became a challenge. In order to overcome this challenge some resolved to "speak in English all the time [so that] students feel closer to the language" (TCF, Angelina). Similarly, one student reflected, "I would like my students to apply their grammatical knowledge to achieve communication in real life issues" (TCF, Camilo).

Pupils' Lack of Understanding and Fear of Being Ridiculed

Participants paid a lot of attention to their students' feelings towards the language. Marlon commented that when he spoke in English "some students started to make faces or laughing, which I think means they don't understand"(TCF).Similarly, laughing at their peers who used English lowered the "victims'" self-confidence and discouraged them from using English: "Students feel fear that their peers might laugh at them because of their pronunciation" (TCF, Yina).

It seemed pupils rejected English even though many times they understood what was said. Participants explained that their pupils pretended not to understand or were lazy to make an effort to comprehend or use the language. That was the case of a student teacher who, as shown in the next extract, was about to start her class:

St: OK, we are going to start. I am going to check the list. [I am going to call the roll]

Ss: Ay, profe, no nos hable en inglés... ¿va a llamar a lista? [Please teacher, don't speak to us in English...you will check attendance, right?]. (FNC, Ana)

Another circumstance was that student teachers perceived their pupils as individuals who would only feel comfortable in class if they were taught in Spanish. Thus, it was really difficult for participants to change this ingrained habit. In this regard, Nury commented:"The idea is to talk just a little in English since kids are used to being spoken in Spanish.When I speak in English they get lost" (TCF).

Due to their constant effort, many pupils did become more cognizant of the function of the foreign language as Dina reveals in the following excerpt: "I notice that at the beginning students did not agree when I talked in English, but after some time they tried to understand and it was a way for them to enjoy English" (STPF). In fact, when asked how they felt when student teachers talked to them in English, some learners said "It is good that he speaks in English because we get used to the language"; "I like when she speaks in English. One learns vocabulary and to use clues...to guess" (NPUI).

Classroom Management and Lesson Organization

Data analysis revealed a close relation between pre-service teachers' need to implement discipline and their inability to communicate with pupils in English:"I couldn't speak English more frequently in a grade because it was difficult to control discipline" (STPF, Nemesis). The following interaction in her class supports this issue. She had decided some students would not sit together in her class:

St: [Takes some time in assigning some students other places to sit]. Sit down, attention. [She checks attendance]

SS: [Loud talking as she tries to check attendance] "me van a dejar llamar a lista o no?" [Will you allow me to check attendance or not?]

St: OK silence, silence.

Ss: [Keep talking loudly]

St: Continúan así y los evalúo.[If you keep up this attitude, you will be given an evaluation.]

SS. [Keep talking loudly].

St: Good morning, Good morning...

Ss: [Keep being loud]

St: Buenos días, me recuerdan que vimos la clase pasada... [Good morning, can anybody remind me what we studied last lesson?]. (TAC)

This scenario reflects that classroom management and the use of L1 or L2 in the EFL classroom have an effect on each other since students' lack of understanding of what happens in the lesson seemed to generate disruption (Prada & Zuleta, 2005). Similarly, Hernández and Faustino (2006) and Wilkerson (2008) underlined that teachers consider classroom management an important reason to prefer the use of L1 in the foreign language classroom.

Data collected such as the previous extract from Nemesis' class challenged student teachers' idea that changing from English to Spanish would surely help them to control indiscipline.

Looking at Themselves: Limitations as Chances to Gain Personal Benefits

At the beginning of the teaching practicum, being aware of their limitations to use the language properly made some participants feel insecure. Four of them, Lina, Nemesis, Dina and Ana, had a pre-intermediate English level. Nonetheless, they tried to overcome their fears as Dina reveals it in the following excerpt: "At the beginning I was afraid to talk in English because of my knowledge and fluency, but I realized the problem is my self confidence" (STPF). They considered using English with their students as a way to improve their own proficiency: "I tried to speak in English also because I can keep my level and my students can learn something" (TCF, Angelina).

A Variety of Tactics to Assemble Communication Channels inside the EFL Classroom

After having considered the factors which shaped participants' intentions to use L2 in the classroom, the next paragraphs discuss which strategies pre-service teachers used to try to achieve this purpose.

Raising Awareness about Using English in Class

Several student teachers started their practicum discussing with pupils the role that English should have in the class. They addressed issues such as the benefits of learning English through practice and the possible effects of constant translation between L1 and L2. Dana mentioned: "I got students to reflect about the importance to be involved in an English environment to handle pronunciation and comprehension" (TCF).

By means of this reflection, pre-service teachers sought to reduce students' anxiety about understanding the language. Apparently, this led some pupils to embrace using English in class; however, others continued to be reluctant. When resistance remained, student teachers agreed with their students on using various means to facilitate communication in English. For instance, Camilo expressed that "At the beginning, I prepared a conversation about the importance of using English. They agreed to use 50% of English and 50% Spanish" (TCF). Nonetheless, imposing and not negotiating the use of English was an attitude which, for example, René evidenced: "I demanded from them not to speak in Spanish".

Dosing out the Use of English and Spanish in the Class

As mentioned in the previous section, one group of participants revealed that they started promoting English as a means of communication from the start of the semester. Another group, in contrast, increased their use of English gradually; they constantly monitored how their oral communication with their pupils by means of the foreign language functioned and supported the process by using specific strategies when necessary. In the following situation Hermes is playing a game about answering personal information questions:

St: Pay attention to a new question. [He throws the ball]. How old are you?

Ss: [They remain silent].

St: Pay attention. I am twenty three.

Ss: Oh. ¿Cuántos años tiene? [How old are you] [one of them said; then, they start talking about ages among themselves].

S1: Mi papá tiene 33 años. [My father is 33].Teacher thirty...? [He asks for help from his teacher to continue]

St: yes...thirty three

Ss: [keep talking about the topic]. (TAC)

The student teacher leads the activity in English. He is attentive to help his pupils when they seem to have limitations to continue speaking in the foreign language. As they directly or indirectly express their lack of knowledge, Hermes becomes a bridge to facilitate their communication. In addition to connecting their lessons with real life topics, as Hermes did in the previous exchange, student teachers used English to involve learners in the following classroom situations.

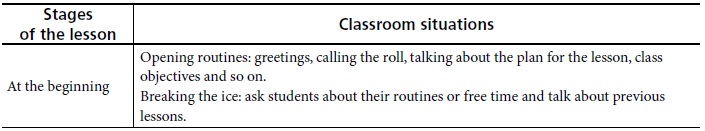

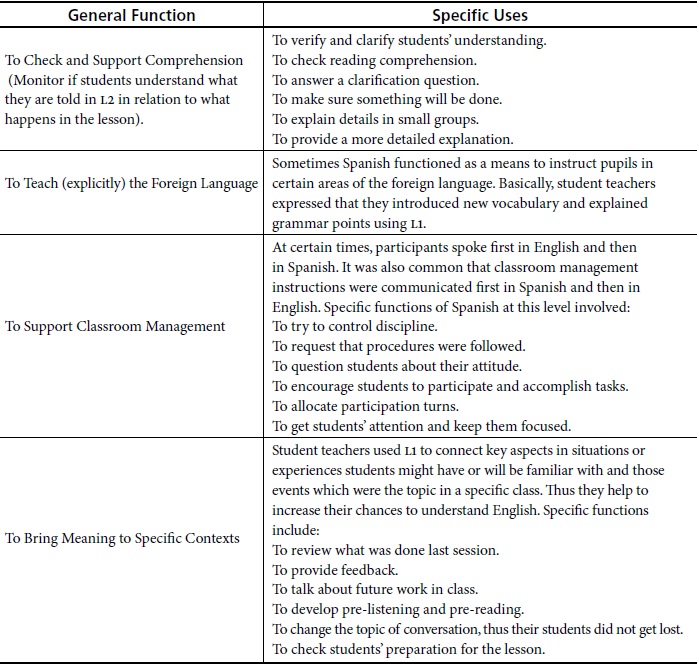

Table 1. Pre-service students' uses of L2 in their EFL classrooms

In contrast, several student teachers who also spoke in English did not sufficiently monitor whether or not their pupils understood what was said. In this case, strategies to support pupils' comprehension were not used. In the extract below, Dina explains an activity students are expected to develop.

St:You are going to write the words that you understand from the song. [She plays the song]

St: [Stops the song]. What did you understand?

Ss. [Silence] St: Mr. Alvarado [She asks a student to say what he understood.]

S1: [Silence] St: Bueno ¿qué palabras entendieron? [OK, which words did you understand?] [She plays the song again.]

Ss: [Listen and take notes]

St: OK Words... [She collects a long list of words from students and writes them on the board.] (FNC)

Dina, in contrast to Hermes, did not make sure kids had understood the instructions she had given in English before starting the exercise. She just continued the lesson and asked students for answers. She seemed to assume it was clear for them what they had to do.When a student in Dina's class was asked how he felt as his teacher spoke in English, he said: "I don't understand because the teacher speaks too fast" (NPUI).

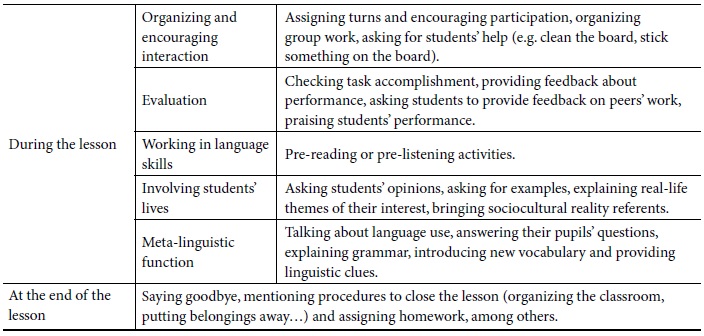

Spanish kept being used in class, even by those participants who generally opted for increasing speaking English.Pre-service teachers perceived the use of L1 as necessary to support communication in the classroom. Conversely, they believed that asking children not to resort to Spanish created a negative feeling since that was a habit they had. Data showed that participants used Spanish for the purposes included in the next chart.

Table 2. Pre-service students' use of L1 in their EFL classrooms

Schweers (2003), Hittotuzi (2006), and Higareda,Lopez,& Mugford (2009) have recently helped to reposition the use of L1 in the L2 classroom taking into account cultural, political, methodological and social factors. Avoiding threatening Ss' identity, providing them security, and facilitating their interaction with peers are some of the benefits of using L1 these authors highlight. They also advise teachers about analyzing carefully how, when, and for what purposes they use and encourage their students to use L1. Finally, their studies incorporate descriptions of the specific uses that L1 has in the L2 classroom. Several of those match the ones included in the chart above.

A Bridge to Understand Each Other: Resources to be Competent Communicatively

Communication strategies contributed to facilitate the interaction in English student teachers tried to establish. Scholars such as Tarone (1981) and Oxford (1990) have widely explained how language learners make use of communication strategies in their attempts to engage in meaningful interaction with others.

Modifying One's Own Speaking in English

Their willingness to interact in English with their pupils led participants to adjust their speech by speaking slowly and simplifying or reducing what they said. This was not always easy since student teachers generally had to be attentive to several aspects of their classes at the same time and eventually they forgot to do it.Camilo expressed:"I try to speak in English as slowly as I can; however, sometimes I realize I am speaking too fast" (CFT).

Including and Emphasizing Meaningful Expressions in order to Ease Interaction

To buttress the communicative process, participants often paraphrased what was said, provided examples, synonyms or clues, emphasized their message by means of cognates and words pupils already knew, recycled language they had taught, repeated what they thought was relevant, and used intonation to support meaning. In order to help a student, Hermes did the following:

S1: Teacher ¿qué es bedroom? [What does bedroom mean?]

ST: It is the place where you find a bed, a lamp...

S1: Humm! La pieza.... [A bedroom]. (FNC)

The student teacher provides a definition of the word and includes several words which might be more common so that his pupil could understand the new word. Pupils developed mechanisms to connect with the strategies student teachers used, even if they did not comprehend what they were told at first. They asked other peers to clarify what the teacher had said, paid attention to other peers' reactions or asked their teacher to explain again. To ask for clarification, they learned key words such as "What?" and "Repeat please", which helped them acquire the information they needed.

Body and Graphic Language

Participants also used non-linguistic elements such as contextual clues based on objects, their body, pictures and writing.

I am trying to use miming. When I mime, translation is not needed for them to understand. If they don't understand, other peers tell them the idea. Miming makes the lesson funnier and they pay attention. (CFT, Dina)

In addition, pre-service teachers usually wrote on the board what they said to support students' comprehension.

Using Translation

Participants translated sometimes by using a kind of interpretation of what was first said in English. In other words, they expressed a general idea in Spanish based on the original English utterance. Others translated word by word or literally.Finally,Spanglish,mixing the two languages in a single sentence, was also a common strategy. In the first sample, Yina is teaching kids how to provide and ask for personal information.

St: [Asks Ss and then write the question on the board] Where do you live?

Ss: [Read aloud from the board word by word] where/do/you/live?

St: si yo les digo [if I tell you]"where do you live?" ¿tú que me dices? [What would you say to me?] [She indicates a specific student].

Ss. [Silence]

St: "Where do you live?" que significa [which means...]: ¿Dónde vives? [Where do you live?] Estoy preguntando [I am asking you]: Where do you live? (TAC)

Yina tried to make students understand the question; she writes the question on the board, says it word by word and repeats it several times, but pupils don't seem to comprehend. Finally, she translates the question into Spanish.

In such situations, pupils would attempt to translate into English or they would press pre-service teachers to do so. Student teachers reported that they employed Spanglish to reduce their pupils' anxiety when they seemed not to understand and thus help their students to complete activities more quickly. Conversely, some pre-service teachers would promote translation themselves. Some participants used translation after first trying several times to get their message across in English while others used it simultaneously from the beginning of the lesson. Several of them translated long pieces of speech, whereas others translated only key words.

Translation from L1 to L2 also took place, but it was a strategy that was employed less frequently in comparison to translating from English to Spanish. Participants used it to tell their pupils how an utterance was said in English. For instance:

Ss: Voy a pasear [I am going on a trip] [says a student talking about "future plans"].

St: Oh, you will take a trip. (FNC, Marlon)

Student teachers mentioned that a drawback of this strategy was that it promoted students' laziness in trying to understand. Furthermore, they also remarked it could become a bad habit.

Teaching the Lesson around Topics Which Facilitate the Use of L2

To begin with,student teachers built a framework for comprehension by means of contextualizing the lesson in realistic scenarios. To accomplish this, they used several techniques.For example,student teachers made the language seem relevant to the students' own lives and interests focusing the lessons on games, the sharing of personal information, stories, everyday classroom situations, and local culture references. This was the case in the following situation in which the student teacher checks attendance:

St: Luisa Perez?

Ss: Present.

St: Miguel Camacho.

Ss: Present, teacher.

St: [Asks the previous student] Did you come last class? [He pointed back with his pen as showing something behind] then he repeats the question.

Ss: No, estaba enfermo. [No. I was sick]. (FNC)

The student teacher goes beyond asking students if they are in class or not. He goes further and having this common classroom practice involves a student in a short conversation about his absence in class. Though the student answers the question in Spanish, his answer reveals he could understand. The student teacher employed body language which in the specific context of the conversation seemed to be effective.

In another situation, Rene explains about the homework they have to do:

St: In the 1st part, you are going to look for the meaning of the words and then make a sentence using famous places.

Ss: [Listen to him and some stick some pictures on their notebooks]

St: For instance, Plaza de Donato is a famous place in Tunja.

Ss: Yes

St: In the second point, you are going to describe that famous place in Tunja.

Ss: Describir un lugar famoso de Tunja. [Describe a famous place in Tunja]

St: Like what?

Ss: Plaza de Bolivar, La Casa del Fundador... (TAC)

The previous exchange reveals how student teachers' referencing familiar places for students seems to increase their chances to comprehend the explanation and participate in the conversation.

On the contrary, participants expressed that certain themes influenced the amount of English they produced during the class:

I use less English in this opportunity. I think it was because of the topic. In the previous lesson the topic was "the future" and today "present perfect". Last class it was easier and students gave more examples about their future professions...sentences were shorter. Present perfect is more complex...I think because of that today I used more Spanish...well, I used both. (CFT, Marlon)

For Mario, talking about the "future" implied more possibilities to involve students since they talked about their plans, whereas a complex grammar topic for him, as "present perfect", meant to speak also in the native language to support pupils' comprehension.

Conclusions and Implications

The motivation and knowledge that teachers can inculcate in their students by speaking to them and promoting the use of English in classrooms can be substantial.Thus,this study revealed a series of factors and strategies needing serious consideration to understand what can limit or favor student teachers' attempts to speak in English during EFL lessons. Furthermore, the findings suggest several actions that can be taken to support prospective teachers in facing this communication challenge, increasing their pupils and their own leaning opportunities.

Student teachers' initiative to speak English in the classroom was influenced by several factors. To begin with, participants' history as learners revealed their tendency to create the same kind of environments they experienced when they were secondary school students; using Spanish to communicate in the classroom was the rule and translation was a common practice. Since English was scantily used by pupils and cooperating teachers, such conceptions were reinforced. Likewise, participants were affected by the fact that their students had not been encouraged to communicate in English and those pupils who spoke in English run the risk of being ridiculed by others. Finally, some participants faced serious challenges because of their low English level and their scarce experience in managing classrooms and indiscipline. All the circumstances mentioned above made them hesitant to speak in English.

However, pre-service teachers' conception of the language as a means for real communication and their perception of limitations as obstacles they needed to overcome led them to seek specific means to achieve oral interaction in English with their students. One strategy that student teachers applied was to discuss with their pupils how and why the target language should be spoken inside the classroom. They also tried to control the amount of English they used and made agreements with learners. Furthermore, they altered their normal English speech using verbal and nonverbal language and communication. Moreover, as part of their lesson implementation, they created or focused on meaningful contexts for students to make language more understandable. Combining the previous strategies, participants tried to involve pupils in a friendly English speaking environment inside the classroom.

In general, such strategies worked as long as student teachers monitored how and when they were employed. This implies that the idea is not to achieve communication with pupils in the foreign language at all costs or to impose the constant use of the foreign language while neglecting to monitor how successful communication with pupils is. This can produce not only frustration, but also rejection toward the foreign language by learners.

In contrast, the goal should be to establish an atmosphere in which pupils feel secure and motivated when using the foreign language. Student teachers should show pupils through various means that the foreign language can fulfill real purposes in life. Furthermore, they can help their students to become aware and skilful in using communication strategies as tools to support their oral interaction and their learning of the language.

It is relevant to count on university preparatory programs which provide prospective EFL teachers plenty of opportunities to reflect upon English and to experience this language in its various communicative purposes. Moreover, these programs need to integrate strategies that lead student teachers to become aware of which and how particular factors can affect their decisions as to using or not using the foreign language in the classroom. Reflective practices can guide future teachers in exploring their beliefs about language, identifying how these conceptions originated and how they influence their teaching.

Cooperating teachers and advisors, as people who greatly affect student teachers' pedagogical ideas, need to be tuned into the prospective teachers' intentions to interact with their pupils in English. Collaboration between these two parties might provide student teachers with valuable professional support from varied, but enriching perspectives. Within their EFL teaching practicum structure, universities should establish solid alliances with schools in order to help cooperating teachers keep familiar with the most current EFL issues.

References

Barlett, L. (1990). Teacher development through reflective teaching. In J.C. Richards & D. Nunan (Eds.), Second language teacher education (pp. 202-215). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bell, T. (2005). Behaviors and attitudes of effective foreign language teachers: results of a questionnaire study. Foreign Language Annals, 38(2), 259-270.

Capel, S. (2001). Secondary students' development as teachers over the course of a PGCE year. Educational Research, 43(3), 247-261.

Ellis, R. (1985). Understanding Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R. (1997). Second language acquisition research and language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Farrell, T. (2007). Failing the practicum: narrowing the gap between expectations and realities with reflective practice. TESOL Quarterly, 41(1), 193-201.

González, M. E. (2008). English teachers' beliefs about communicative competence and their relation with their classroom practices. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 10, 75-90.

Harmer, J. (2007). How to teach English. Essex: Pearson-Longman.

Haycraft, J. (1986). An Introduction to English language teaching. London: Longman.

Krashen, S. (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning. Oxford: Pergamon.

Hernández, F., & Faustino, C. C. (2006). Un estudio sobre la enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras en colegios públicos de la ciudad de Cali. Lenguaje, 34, 217-250.

Higareda, S., Lopez, G., & Mugford, G. (2009). ¿Duermes mucho Tony? Interpersonal and transactional uses of L1 in the foreign-language classroom. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 11(2), 43-54.

Hittotuzi, N. (2006). The Learners' mother tongue in the L2 learning-teaching symbiosis. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 7, 161-171.

Lightbown, P., & Spada, N. (1993). How languages are learnt. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Littlewood,W. (1984). Foreign and second language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Merriam, S. B. (1988). Case study research in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publications.

Melnick, S., & Meister, D. (2008). A comparison of beginning and experienced teachers' concerns. Educational Research Quarterly, 31(3), 39-56.

Muñoz, J., & Mora, Y. (2006). Functions of code-switching: tools for learning and communication in English classes. How, 13, 31-45.

Nunan, D. (1992). Research methods in language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies. New York, NY: Newbury House Publishers.

Paulson, L. F., Paulson, P. R., & Meyer, C. (1991). What makes a portfolio a portfolio? Educational Leadership, 48(5), 60-63.

Pentimalli, B. (2005). Observation in situ within ethnographic field research. Retrieved from: //www.irit.fr/ACTIVITES/GRIC/cotcos/pjs/MethodologicalApproaches/datagatheringmethods/gatheringpaperPentimalli.htm

Pollard, A., & Tann, S. (1993). Reflective teaching in the primary classroom. London: Cassell.

Prada, L., & Zuleta, X. (2005). Tasting teaching flavors: a group of student teachers' experience in their practicum. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 5, 157-170.

Richards, J.C., & Lockhart, C. (1994). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rodgers, C. (2002). Voices inside school: seeing student learning: teacher change and the role of reflection. Harvard Educational Review, 72(2), 230-250.

Sánchez, A. (2001). Demystifying and vindicating communicative language teaching. How, 8, 83-87.

Seliger, H., & Shohamy, E. (1990). Second language research methods. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Strauss,A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory, procedures and techniques. London: Sage Publications.

Soares, D. (2007). Discipline problems in the EFL classroom: is there a cure? PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 8, 41-58.

Schweers, C. (2003). Using L1 in the L2 classroom. Forum, 41(4). 34-37.

Tarone, E. (1981). Some thoughts on the notion of communication strategies. TESOL Quarterly, 15, 285-295.

Tsui, A. (1995). Introducing classroom interaction. London: Penguin.

Vélez, G. (2003). Student or teacher: the tension faced by a Spanish language student teacher. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 7-21.

Viáfara, J. J. (2005). The design of reflective tasks for the preparation of student teachers. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal. 7, 53-74.

Viáfara, J. J. (2007). Student teachers' learning: the role of reflection in their development of pedagogical knowledge. Cuadernos de Linguística, 9, 225-242.

Viáfara, J. J. (2008). From pre-school to university: student teachers' characterize their EFL writing development. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 10, 73-92.

Wallace, M. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wilkerson, C. (2008). Instructor use of English in the modern language classroom. Foreign Language Annals, 41(2), 310-320.

About the Author

John Jairo Viáfara is an assistant professor at Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC), in Tunja. He holds a BEd in Education (English) from Universidad Nacional de Colombia, a Masters in Applied Linguistics (Universidad Distrital) and currently is a Fulbright scholar working toward his PhD at The University of Arizona. His interests include pre-service and in-service teacher education, pedagogical research and ELT Methodology.

Appendix 1. Form to Elicit Information about Participants' Classes

Appendix 2. Counselors' Class Observation Form

Appendix 3. Questions Asked Student Teachers about their Use of English during Conferences

Appendix 4. Samples of Questions Asked Student Teachers' Pupils during the Unstructured Interview*

_____________________

* Questions were asked in Spanish and translated into English for the purpose of this publication.

Appendix 5. Guidelines to Keep Portfolios

Guidelines to keep your portfolio

1. How to start:

- Get a folder (spacious enough to store a good amount of material) and decorate.

- File the evidences of your work chronologically (record dates),weekly.

2. The sections of the portfolio.

a.Reflection: include a weekly entry of a journal in which you reflect on your teaching practice: lesson planning, school contexts, interaction with pupils, what you learn, and what is difficult.

b.Keep your lesson plans and corrections when necessary in chronological order.

c.Include your reading logs (analytical summaries of readings: make connections between theory and practice, evaluate theory, and contextualize theory in your experience).

d.Include a collection of samples which reveal the most meaningful work or situations you have developed or experienced. Write a text reflecting upon the meaning of this evidence in your teaching.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Visitas a la página del resumen del artículo

Descargas

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2011 John Jairo Viáfara

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivadas 4.0.

Los contenidos de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development son de acceso abierto y los cubre la Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional. Se autoriza copiar, redistribuir el material en cualquier medio o formato, siempre y cuando se conceda el crédito a los autores de los textos y a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development como fuente de primera publicación. No se permite el uso comercial de copia o distribución de contenidos, así como tampoco la adaptación, derivación o transformación alguna de estos sin la autorización previa de los autores y de la Editora de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Los autores conservan la propiedad intelectual de sus manuscritos con la siguiente restricción: el derecho de primera publicación es otorgado a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.