Autobiographies: A Way to Explore Student-Teachers’ Beliefs in a Teacher Education Program

Palabras clave:

Autobiographical narratives, qualitative research, students’ beliefs, teacher education (en)Descargas

Autobiographies depict with words life stories, personal experiences, and perceptions that allow researchers to deeply understand the way people see life, reflect, and construct meaning out of experiences. This article aims at describing the contributions of autobiographies as valuable resources in qualitative research when exploring people’s beliefs, personal knowledge, and changes as a result of experience and learning. This is all based on a research project carried out at a Colombian public university, where students from the undergraduate English teaching program wrote their language learning stories which were used as an instrument to garner data. The project also aims at demonstrating how these narratives exhibit human activity and diverse events that may have a significant effect on the epistemologies and methodologies of teacher education.

Las autobiografías perfilan con palabras las historias de vida, experiencias personales y percepciones que brindan a los investigadores una profunda comprensión de la manera como las personas ven la vida, reflexionan y construyen significado a partir de esas experiencias. Este artículo tiene como objetivo describir las contribuciones de las autobiografías como recursos valiosos en la investigación cualitativa por cuanto son un medio para explorar las creencias, el conocimiento personal y los cambios en los individuos como resultado de la experiencia y el aprendizaje. El presente trabajo se basa en una investigación realizada en una universidad pública colombiana, en la que estudiantes de la Licenciatura en Inglés narraron sus historias sobre el aprendizaje de la lengua; narraciones que fueron usadas como instrumentos para la recolección de información. Adicionalmente, se busca demostrar cómo dichas narrativas describen la actividad humana y diversos eventos que pudiesen tener un efecto significativo en la construcción epistemológica y metodológica en la formación de docentes.

Autobiographies: A Way to Explore

Student-Teachers’ Beliefs in a Teacher Education Program

Autobiografías:

una forma de explorar las creencias de docentes en formación en un

programa de Licenciatura en Inglés

Norma Constanza Durán

Narváez*

Sandra Patricia Lastra

Ramírez**

Adriana María Morales

Vasco***

Universidad del Tolima, Colombia

This article was received on

December 28, 2012, and accepted on June 30, 2013.

Autobiographies depict with words life stories,

personal experiences, and perceptions that allow researchers to deeply understand

the way people see life, reflect, and construct meaning out of experiences.

This article aims at describing the contributions of autobiographies as

valuable resources in qualitative research when exploring people’s

beliefs, personal knowledge, and changes as a result of experience and

learning. This is all based on a research project carried out at a Colombian

public university, where students from the undergraduate English teaching

program wrote their language learning stories which were used as an instrument

to garner data. The project also aims at demonstrating how these narratives

exhibit human activity and diverse events that may have a significant effect on

the epistemologies and methodologies of teacher education.

Key words: Autobiographical narratives,

qualitative research, students’ beliefs, teacher education.

Las

autobiografías perfilan con palabras las historias de vida, experiencias

personales y percepciones que brindan a los investigadores una profunda

comprensión de la manera como las personas ven la vida, reflexionan y

construyen significado a partir de esas experiencias. Este artículo

tiene como objetivo describir las contribuciones de las autobiografías

como recursos valiosos en la investigación cualitativa por cuanto son un

medio para explorar las creencias, el conocimiento personal y los cambios en

los individuos como resultado de la experiencia y el aprendizaje. El presente

trabajo se basa en una investigación realizada en una universidad

pública colombiana, en la que estudiantes de la Licenciatura en

Inglés narraron sus historias sobre el aprendizaje de la lengua;

narraciones que fueron usadas como instrumentos para la recolección de

información. Adicionalmente, se busca demostrar cómo dichas narrativas

describen la actividad humana y diversos eventos que pudiesen tener un efecto

significativo en la construcción epistemológica y

metodológica en la formación de docentes.

Palabras

clave: autobiografías, creencias de

los estudiantes, formación docente, investigación cualitativa.

Introduction

This paper aims at showing the significance of

studying autobiographies as a source for examining student-teachers’

beliefs, the way they are analyzed and the answers they provide regarding how

students start framing their understanding about teaching by looking at their

learning histories. The accounts also revealed the concomitant influence of

teacher education subjects on their renewed or in-construction pedagogical

conceptions. To understand the student-teachers’ conceptions and the role

they play in their education may make a great contribution in two directions.

One of them is to rethink the teacher education programs content and

student-teachers’ own conceptions behind the theories presented in such

programs. The second one is to enhance student-teachers’ knowledge growth

providing them with opportunities to make their preexisting knowledge explicit

to be examined and challenged (Calderhead &

Robson, 1991). This study also attempts to provide insights that may serve to

guide similar studies and conceive autobiographies as a way to promote

pedagogical practice understanding and teacher development in teacher education

programs, as it has been a major discovery in this research. It simultaneously

attempts to lead to new considerations of our role as teacher educators who

particularly guide teaching practicum processes. Unfortunately, based on the

related literature, both this issue and the contribution that personal accounts

may make to teacher education programs tend to be overlooked in our context, as

stated by Woods (as cited in Mendieta, 2011):

Research has addressed extensively

what happens to second language learners from a host of perspectives but has

failed somehow to examine the processes by which language teachers plan and

make decisions about teaching, as well as what they bring to the second

language classroom such as knowledge base, beliefs and experiences. (p. 90)

To arrive at the findings in this study, it was also

important to explore ways of analyzing narratives as a path of learning and

growing as learners of teaching and teacher educators. For this purpose it was

crucial to follow a systematic process in order to interpret the

participants’ stories. The implicit timelines of the students’

learning and teaching histories helped identify the critical incidents, salient

factors, and trends likely to influence student teachers’ teaching

theories and classroom practices, issues which will be expanded upon in the

research design segment.

The oncoming sections of this article will discuss the

concepts of autobiographies as a narrative mode and their role in the

exploration of beliefs in pre-service teachers, as well as their contribution to

teacher education programs. Furthermore, the methodology followed is described

and the results and conclusions presented.

Theoretical

Framework

Autobiographies

in Teacher Education

Autobiographies as a way of narrative have become

paramount in the teacher education field and, indeed, have become a lens to

explore and facilitate understanding of teaching practices and to delve into

the what, the how, and the why of pedagogical actions. In some local studies

connected to the use of narrations to explore beliefs and practices, Clavijo (2000) draws attention to autobiographies as a way

to bring together who the teachers are as people, their sense of self, their

knowledge base, and understanding of their practices and social, historical,

and cultural values as well as how they permeate practice. The latter were also

evident in the present study as a decisive dimension in approaching the

interpretation of autobiographies. Regarding the approaches followed in order

to uncover what autobiographies contain, Mendieta

(2011) describes the construction of narratives around teachers’

experiences and beliefs with respect to curriculum. Those experiences and beliefs

are reflected in the past and present language learning and language teaching

practice. The final integration of the former items into a story after the

analysis reflects commonalities and differences of the participants’

knowledge base, beliefs and experiences. Moreover, some of the outcomes brought

to surface when exploring autobiographies have to do with the rediscovery of

memories, the development of new perspectives on teaching, the discovery of

reasons behind personal beliefs systems or the enunciation of new ones (Bailey

et al., 1996). This has been an observable fact in this study which will be

later illustrated. Furthermore, great emphasis has also been placed on

teachers’ identity as a need that teachers make sense of themselves by

stressing the importance of relating the personal with the professional realm,

as well as teaching and learning in the everlasting quest of self-understanding

(Serna, 2005). Other local studies in the area have explored the topic of

beliefs in relation to assessment and have made visible the dissonance between

beliefs and practices (Muñoz, Palacio, & Escobar, 2012). In fact,

this is a matter we highly anticipate to be undertaken near the end of the

whole project through class observation.

Autobiographies as a mode of narrative have

demonstrated that pre-service teachers, particularly, may also come to make

sense of their pedagogical practices. In this vein, Stenberg (2011) states that

focusing on teachers’ own life experiences can help to access the inner

beliefs, values, and understandings that fundamentally guide teaching practice.

As underlined by this author, autobiographies appear as a valuable instrument

to look at teachers’ beliefs, conceptualizations, thoughts, and actions

in the present. Besides, they are influenced by experiences from the past,

expectations for the future and shape teachers’ practices (Kelchtermans, 2009). According to Johnson (1999),

autobiographies are a way to capture the richness of prior experiences and to

get into the critical analysis of those experiences and beliefs in order to

come to comprehend the complexity of the understandings of teachers, teaching,

and learning.

For this study, the exploration of the autobiographies

as narratives has been grounded in two current and broad correlated theoretical

trends: sociocultural perspective (Johnson, 2009) and teachers’ cognition

(Borg, 2009).

A

Socio-Cultural Standpoint to Teacher Education

The socio-cultural perspective is a fairly new one

which entails the theoretical ground to explain and conceptualize teacher

learning, language teaching and teacher education overall. In this line, this

perspective sustains the value of autobiographical accounts in the examination

of what is behind student-teachers’ beliefs and how their practices are

or may be the reflection of their previous experiences as social individuals. A

fundamental principle of a socio-cultural theoretical perspective is that human

cognition is understood as originating from and fundamentally shaped by

engagement in social activity. In this regard, Johnson (2009) points out:

The processes of learning to teach

are socially negotiated. Teacher learning is understood as normative and life-long;

it is built through experiences in multiple social contexts first as learners

in classrooms and schools, then later as participants in professional teacher

education programs, and ultimately in the communities of practice in which

teachers work (Freeman & Johnson, 1998; Grossman, 1990). (p. 10)

Teacher

Cognition and Sense Making in Pre-Service Language Teachers

Complementary to the socio-cultural view, teacher

cognition is defined by B org (2006) as developments in research which have

focused on how teaching as well as teachers’ mental lives have been

conceptualized. Some of the themes tackled when exploring pre-service

teachers’ cognitions are related to beliefs about language teaching,

cognitions in relation to practicum experiences, teachers’ instructional

decision making and practical knowledge. On the same subject, the core of this

study is the examination of prospective teachers’ beliefs about teaching

strategies which, through the use of autobiographies, showed the link between

their previous experiences as language learners and their growing images of

teaching.

Beliefs, considered as changeable and dynamic, do not

occur in a linear fashion, but they comprise social, cultural, and political

forces which causes students’ conceptions and beliefs to be rooted in a

system that seems hard to be altered (Goodson, 2005). In addition, in Lortie’s words (as cited in Bailey et al., 1996),

their apprenticeship of observation and the influence of teacher education programs

dealing with the process of learning to teach become their prior knowledge and

knowledge base for the establishment of new constructs, reorganization of existing

structures until they hopefully turn into stable general and personal theories.

In student-teachers’ autobiographies in this study, the accommodation and

activation of their different sources of beliefs and their interpretation of

learning to teach were extensively evidenced.

In different studies about learning to teach, the

power of prospective teachers’ experiences as learners and how such

experiences help to frame the conceptions, beliefs systems, values, and images

for their future practice, have been recurrent. In the process of searching for

what happens when these students make public their life stories within their

life histories (Goodson, 2005), it has been brought to light the way students

start conceptualizing and shaping or reshaping their decision making and

practical knowledge. In the present study, this was reflected in the

participants’ in-construction philosophies of teaching, identity issues,

the influence of teacher education courses, and student-teachers’ wishes

and future plans, which will be presented and discussed later in the document.

Research

Method and Research Design

This paper is based on a qualitative research project

carried out at University of Tolima, Colombia, where students from the B.A. in

English program wrote about their language learning stories in order to explore

their beliefs concerning English teaching strategies. Through these narratives,

autobiographies rather, students exhibited their experiences, diverse events,

happenings, and actions they had lived in their English learning process and

that had had a significant effect on their epistemologies and methodologies of

teaching as student-teachers (Polkinghorne, 1995).

Since stories provide an open access to the identity

and personality of individuals and reflect their inner reality in the outside

world, autobiographies constitute a fundamental element to explore and analyze,

via the B.A. in English program, students’ beliefs concerning English

teaching strategies.

We all are storytellers by nature and stories provide

consistency and continuity to our experiences and have an important role in our

communication with others (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, & Zilber,

1998). Besides, telling a story is having the opportunity to create an

identity, and a particular self which will fit specific contexts, purposes, and

audiences (Ricoeur, 1980). That

is why autobiographies provide a vast sea of possibilities to explore and

describe students’ beliefs.

The following questions have guided this study and

have yielded the subsequent results:

Questions

How do autobiographies reveal student-teachers’ beliefs

about English language teaching strategies?

How do autobiographies unveil the contribution of the

preparatory subjects of the B.A. in English program to the course of

student-teachers’ beliefs?

Participants

This research was carried out at Universidad del

Tolima, Colombia, the only public university of the region. Nine

student-teachers from the B.A. in English program volunteered to be

participants. Their names have not been used in this study responding to

ethical issues. Instead, we used their initials in order to respect their

identity as agreed in the consent letter they signed. They were doing their

didactics and first teaching practicum course which are part of the pedagogical

preparatory stages. They were also about to start their second teaching

practicum in different public schools in Ibague in 2010.

Each one of the participants wrote an autobiography

about their English learning experiences throughout their school years and it

became one of the instruments used for data collection in the study. With this

instrument, we intended to learn about their prior learning experiences, their

current beliefs about teaching strategies, their reflections and all the

sense-making of their language learning stories in their life histories.

Autobiography

Implementation

Narratives have value in educational studies as tools

to access teachers’ thinking and practical knowledge (Elbaz,

1990). The narratives in this study are autobiographies which are

“self-stories” that narrate a set of language learning experiences

within particular contexts. Denzin (as cited in

Stenberg, 2011) describes a biography as a self-story that positions the teller

in the center of a narrative; it is a story about the individual in relation to

an experience and is built upon the statement that any individual is a

storyteller of personal experiences.

The assignment for students was to write some prose

concerning their prior language learning experiences by answering the following

lead questions, which were adapted from some guidelines provided by Johnson

(1999) and Borg (2006):

1. In what

ways has your personality influenced the way you learn? Have your teachers taken

this influence into account when planning and executing their classes?

2. What

language learning experiences have you had and how successful have they been?

3. From the

teaching practices you have been exposed to throughout your language learning

process, describe both the effective and ineffective ones.

4. How has

your experience as a language learner influenced your decision of becoming a

language teacher?

We wanted to identify and analyze trends, critical

incidents, and salient factors influencing their beliefs about English teaching

strategies (Bailey et al., 1996). The students wrote one or two-paged

compositions which were read and analyzed following the systematic process

described below.

Reading to

Hear the Authors’ Voice

Within this process there were three reading moments

which had specific intentions. The first reading had the purpose of just

hearing what participants were saying. The second moment sought to interpret

the information and identify the narrative core, which contained the most

significant aspects of the narration. This reading allowed the researchers to

identify events, meaningful issues or moments which were highlighted with

different colors. The third reading aimed at re-reading the highlighted

sentences or expressions in order to construct understanding of what the teller

was communicating.

The process was complemented the holistic approach of Lieblich et al. (1998) and embraces the stories’

units of analysis, derived from the plot structure and from progression. In

this regard, ascending and descending points, climax, and turning points in the

stories were at the heart of the entire analysis. The whole process helped to

make sense of the stories told and unveiled useful insights and answers for

this study. The ascending, descending, climax and turning points were

identified by the use of descriptive words—adjectives and

adverbs—that portrayed the participants’ experiences and feelings.

Mapping the

Narration

A story map was designed to find the

participants’ voices in a particular time frame and to systematically

organize the learners’ experiences of the past, present, and future. This

map helped us to become aware of the strength of each moment participants

described in their autobiographies; we could see through a line story the whole

language learning process of each one of the participants.

Finding

Patterns and Meaningful Events

The purpose of this moment was to find repeated patter

ns or repeated story lines which became meaningful details to fully understand

the issue we were investigating. These patterns and meaningful events were then

condensed in a narrative core which had the purpose of summarizing and putting

together the most significant issues of the narration. You may not find all the

information you need in one single story, “but each one provides pieces

for a mosaic or total picture of the concept” (Marshall & Rossman, 1995, p. 88). The repetitiveness of patterns and

main events, which were analyzed and described in detail here, yielded the

definition of the categories.

Data

Analysis

We approached the analysis of the autobiographies

following essentials within Clandinin and

Connelly’s model (1995):

• One

of them was content, which helped us

a lot with rising categories related to the objectives of the study. This

process, called Unity of Analysis by

the researchers, showed us new perspectives and different routes as to how to

approach student-teachers’ thoughts, ideas, feelings, and most of all,

beliefs.

• A

second one was form which enlightened

the analysis and paved the way to the evolution in the structure of the

narration. It was of great importance when realizing how ascending and

descending positions were evident, that is, high points or dramatic

turning-points in autobiographies.

By taking these two aspects into account, we analyzed

the story trying to “weave history from the past” aiming at

understanding the narrative in the three historical moments—past,

present, and future—and being able to give meaning to the ascending and

descending tones in history, leading to the important aspects in the

autobiographies we called “narrative cores,” which are precise

reflections of student-teachers’ beliefs about teaching beliefs that are

the product of their own learning experiences.

These narrative cores helped us by giving each

student-teacher an identity, where convergences and divergences among

participants were highlighted. According to Burns and Richards (2009):

Stories are used to organize,

articulate, and communicate what we know about ourselves as teachers, about our

teaching, about our students, bringing together past, present, and future . . .

we cannot properly understand teachers and teaching without understanding the

thoughts, knowledge, and beliefs that influence what teachers do. Similarly, in

teacher education, we cannot make adequate sense of teachers’ experiences

of learning to teach without examining the unobservable mental dimensions of

this learning process. (pp. 158, 163)

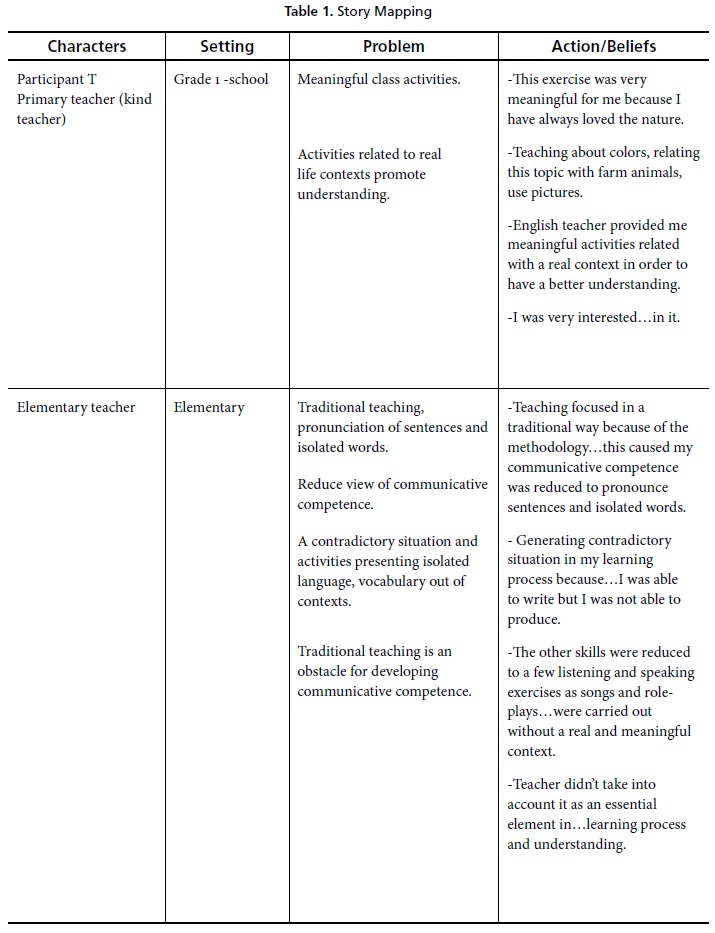

There were two moments in which the analysis was made.

The first moment was called “listening to the authors’

voice.” In it, we categorized information and labeled sub-groups as:

Character (participant’s name), Setting (place and time), Problem, and

Beliefs. As previously exposed, particular issues—expressed in the form

of inquiry—were suggested to student-teachers as a starting point for

autobiography writing. Consequently, analysis in this case focused on those

aspects (Table 1). Setting,

for instance, accounted for the moment in the participants’ language

learning story, either elementary, high-school, or university, that was the

object of narration at a certain moment; we called the next one Problem, since aspects described here

were all awkward to participants throughout their English learning processes;

it clustered aspects such as English teachers, English language teaching

methodology, students’ perceptions, students’ feelings,

students’ opinions about themselves, students’ general perceptions and

opinions about language teaching and their process of becoming future teachers;

English language learning experiences, evaluation, personality features

affecting language learning processes, effective/ineffective teaching

practices, learning strategies involved, and skills development. The Beliefs section, for its part, sometimes

accounted for descriptions of student-teachers’ beliefs about their

learning experiences and, at other times, for actions undertaken by teachers in

schools that were justified or explained by the students according to their own

beliefs system, all of them being related to the aspects listed in the Problem

section.

Then, analysis continued and a second moment emerged

which was “piecing history together.” In this new stage, the same

information was divided again into past, present, and future moments through

which we pretended to identify new sound details deeply intertwined in data. As

asserted by Lortie (as cited in Johnson, 1999, p.

19), “novice teachers need to appreciate how their personal history and

experience of schooling influence their perceptions of classrooms” in

such a way that beliefs continued to be formed. As stated in the introduction,

past, present, and future moments were identified and classified following the

holistic model of analysis by Liebitch et al. (1998).

All this process of analysis allowed us to unravel the

students’ memories that had influenced their conceptions about language

teaching methodologies. This is perfectly supported by Johnson (1999) when she

states that:

For most teachers, the

apprenticeship of observation encompasses two types of memories. The first is our

memories as students: how we as students were expected to talk and act and what

we learned from the experiences of being students. The second is our memories

of our former teachers: What these teachers did and said and how they

approached teaching and learning. Unknowingly these memories become the basis

of our initial conceptions of ourselves as teachers,

of how they influence our views of students, formulate the foundation of our

reasoning, and act as the justifications for our teaching practices.

Interestingly, these memories also seem to have a lasting impact on the kind of

teacher we each aspire to be. (p. 19)

Findings

This section describes the categories that emerged

throughout the analysis of autobiographies which bring to the fore enlightening

answers to the research questions. The first of them was related to how

student-teachers’ beliefs about learning strategies can be uncovered through

the analysis of autobiographies, and the second one had to do with how the

participants’ autobiographies could unveil the contribution of the

preparatory courses of the B.A. in English program to the construction of those

beliefs. The categories will be described and supported by students’

voices that recreated their own language learning experiences in the narrations

and allowed us to see the influence of such events on their former and new

beliefs.

From the participants’ language learning experiences

in elementary and high school, we named a central category Sources of

In-Construction Beliefs since the beliefs explained the “what and

why” of the opinions participants themselves had about English language

teaching strategies. In the source, they described what their elementary and

high school teachers used to do in English classes; the

“traditional” (using participants’ words) methodological

approaches they were exposed to for years in which no place was left for

interaction, active participation, or correction and feedback; the boring

techniques and strategies their former teachers used in classes; and the

participants’ informed and reflective opinions about all those issues.

The following are the different sources of

in-construction beliefs of the students in relation to the language teaching

strategies.

Interaction

of Experiences

Through stories, participants could compare and

contrast the two worlds, being a learner and being a teacher. Thus, they

realized how important it was to become a good language teacher and how

inspiring or detrimental it can be to students. The recognition of these

factors by the student-teachers tend to make visible the redefinition and

reorganization of their views towards the teaching profession; they made this

evident by their clear identification of teaching methodological and

theoretical principles for the fundamental communicative skills development and

language teaching.

The following excerpts demonstrate students’

recognition of effective practices and value of professional knowledge (Shulman, 1986) that have had and may have

an impact on their current role as learners and on their future one as

teachers. These also depict the students’ encounters with their learning

experiences at university and their relationship with their emerging beliefs.

Effective English teaching involves:

the development of all skills, the development of the communicative competence.

It offers different strategies so different kinds of students may have the

possibility to learn. (Learning styles) T

Through my learning process I have

discovered my learning styles and I have understood that teaching and learning

a foreign language is not an easy work. For me is really important to know how

this knowledge can be applied. N

I think that my experience as a

language learner has influenced my decision of becoming a language teacher,

because I am a learner and now I know a teacher can build a good and self-confident

learner or may destroy the desire to learn. L

After further analysis of those origins, we also found

in the student-teachers’ opinions common patterns that evidenced the

influence of the teacher education courses reflected in all the new ideas

student-teachers have about teaching strategies.

Teaching

Education Courses at the University

This subcategory refers to the way students perceived

their teacher education experiences throughout their university studies. From the

students’ view, their classes have been characterized by the

implementation of different methodologies, and their teachers have become

models to follow in their future. They also highlighted those learning

experiences as novel, appropriate, and different from the ones in elementary

and high school. Through their autobiographies, participants show the

university as the “turning point” where things started changing and

although it was difficult at the beginning for most of them, they have learnt

many useful things from teachers and the different courses that have shaped

their budding teaching styles.

I consider effective the subjects at

the beginning because they had a link between theory and practice because they

have shown methods, approaches, theories, authors and the most important part

is that we can apply it. L

I hope using all the concepts that I

have learned through the semesters as mediators between theory and practice, to

take into account the context in a natural way where activities are going to be

used in a real context with the objective that the students understand the

meaning. N

Another effective teaching practice has

been the model the teachers of the B.A. have, because these teachers have shown

us good and several kinds of activities, approaches, methods that we can judge

and in this way to correct, improve and implement in our classroom. L

The teachers had different

methodologies…some were more significant for me than others. F

Regarding the above subcategories and in juxtaposition

to the ideas exposed by the students in the previous excerpts, Johnson (1999)

comments the following:

How they think about their subject

matter content depends on their own experiences as learners of that content,

their understanding of how that content is viewed and organized within the

discipline, theoretical orientation, and instructional importance placed on the

materials they use. How they think about their students depends on their own

experiences as students; their beliefs about how students should act and learn;

the academic, social, and personal expectations they hold for their students

and how their students are viewed within the context of schools and surrounding

communities in which they live. (p. 56)

The already addressed revision of the sources that

intervened in the construction of student-teachers’ beliefs about

language teaching strategies derived into a parallel shaping of their growing philosophy of teaching, thus having a mutual

relation with the building of their self-identity, features that we consider a

noteworthy discovery in this study. “Developing a

personal philosophy involves clarifying educational issues, justifying

educational decisions, interpreting educational data, and integrating that

understanding into the educational process” (Wiseman, Cooner,

& Knight, 1999). This statement supports the preliminary conceptions

student-teachers hold about principles for teaching a foreign language, their

conceptions about what being a good teacher means, what good teaching entails

and the way they project themselves as teachers. They start evidencing the

construction of the philosophy of teaching through new understandings of what

should prevail in the profession and characterize teachers’ practice.

These initial traces of shaping a belief system seem to respond to the

influence of a landscape of personal and language learning experiences. As will

be shown, both successful and unsuccessful experiences have become the basis

for envisioning different pedagogical practices with the purpose of developing

not only language skills on the learners, but also to see them as the center of

the teaching and learning process.

The following excerpts illustrate their new views

about teaching strategies, approaches to teaching, knowledge of students’

likes and interests, and the importance of rapport and human values:

You grow as you learn from your

students...not only from the academic aspect you learn how to be a person. F

In this

profession you learn patience, perseverance, dedication and respect. D

I would like to teach them from a

meaningful and real perspective…with all the three basic skills. T

I want to be an excellent

teacher…to have the responsibility to help others to develop their

skills. J

Participation

and self-confidence, contributing to the development of communicative competence. N

In this category we also grouped other features that

participants considered prime: contextualized learning of languages,

meaningfulness gotten through real life situations, development of

communicative competence, consideration of students’ learning styles, and

feedback treatment.

Teaching strategies should embrace meaningful

activities related to real life, contextualized language, development of

communicative competence, take into account learning styles and students’

correction. T

The purpose of learning a foreign

language is based on the development of language skills,

be able to establish a conversation, interchange meanings, knowledge and so on,

and you have to express your feelings and mainly talk. C

Take into account the

students’ interests, to create friendly environments, the use of games

and class dynamics, provide real contexts. C

I consider that the way to correct

the learner is key to open the learning door because

you can interact, correct and help learner to do it in the best way. Also

collaborative learning where the students that have a high level help to

others. The interaction where it provides opportunities for

the negotiation of meaning. L

In addition, there was clear support of the innovative

future plans they have for their students and their classes.

Wishes and

Future Plans

This aspect becomes another parallel effect of the

process of the construction of student-teachers’ beliefs. We arrived at

this last category by listening attentively and understanding the voices of the

participants in the study and their desire whether or not to become English

language teachers. Although they likely perceive it as a difficult work, they

encourage themselves and foresee their future students’ successful

learning processes as the most important and rewarding result.

I think that

to teach is not easy. Really I want to be a teacher; I know that it may be

difficult, but I know that I can do it. J

In conclusion, I think that really I

would like to be teacher because of that I am studying this. L

In a future I wouldn’t like to

be a teacher…I never imagine to become a teacher…because I am aware

that is a big responsibility and I am not prepared to face that situation because

of my personality…I have an introverted personality and I am not

confident to speak. D

I think my language learning has not

influenced my decision to become a language teacher. N

I would like to teach them from a

meaningful and real perspective…I would like to give the opportunity to the

students to develop all the things that I could not on my personal learning

process. L

I do not remember an exact moment

when I came to the decision of being a teacher, even now it's something not

clear for me…being a teacher is one option…I would like to be a

teacher who is able to teach important languages…give to my students

tools to be proficient…it would be great. M

Conclusions

The aims of the research questions that have guided

the process of this study are clear enough to account for, first of all, how

the autobiographies reveal the student-teachers’ beliefs about English

language teaching strategies. Regarding this first question, participants in

this study took a stand towards the questions that were suggested as guidelines

for autobiography writing. Evidence collected shows that those beliefs have

been forming since elementary or high school English classes.

Participants’ school teachers, their teaching styles, methodology used,

and personal traits have shaped student-teachers’ beliefs about English

language teaching. They overtly describe how those conditions they have been

exposed to enable them get a clear idea of what teaching should look like or

be, and what a teacher should or should not do. That is, experience has formed

both positive and negative ideas in students of what is and is not worth doing

in a classroom.

Secondly, the other question (How do autobiographies

unveil the contribution of the preparatory courses of the B.A. in English

program to the course of student-teachers’ beliefs?) was addressed at

different moments during autobiography writing. Those beliefs, according to

students’ descriptions, have strengthened as semesters have passed and as

content belonging in the Didactics courses and Teaching practicum have touched

students’ lives, and now underlie their opinions and ideas; in a word,

their beliefs.

On the other hand, as researchers and teaching

practicum counselors, this process of inquiry and analysis has impacted us very

positively. First, it has helped us discover new perspectives on how to go

beyond factual information and discover what underlies students’

opinions. Also, it has trained us on how to newly size up qualitative

information so that it yields tangible results. Lastly, it has lent us a hand in

considering integrative and interdisciplinary solutions at the moment of

solving one’s own or others’ classroom difficulties.

Finally, concerning the B.A. in English Program(s),

this project expands new perspectives as regards curricular integration and

interdisciplinary relationships, an idea that goes hand-in-hand with the

appropriate and necessary restructuring, sequencing, and support of content in

curriculum.

References

Bailey, K., Bergthold, B., Braunstein,

B., Fleischman, N., Holbrook, M., Tuman, J., . . . Zambo, L. (1996). The language

learner autobiography: Examining the “apprenticeship of

observation.” In D. Freeman & J. Richards (Eds.), Teacher learning in language teaching

(pp. 11-27). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Borg, S. (2006). Teacher cognition

and language education: Research and practice. London, UK: Continuum.

Borg, S. (2009). Introducing language teacher cognition.

Retrieved from http://www.education.leeds.ac.uk/assets/files/staff/borg/Introducing-language-teacher-cognition.pdf

Burns, A., & Richards, J. C. (Eds.). (2009). The Cambridge guide

to second language teacher education. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Calderhead, J., &

Robson, M. (1991). Images of teaching: Student teachers’ early

conceptions of classroom practice. Teaching

and Teacher Education, 7(1), 1-8.

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M.

(1995). Teachers’

professional knowledge landscapes. New York, NY: Teachers College

Press.

Clavijo, A. (2000). Formación de docentes, historia y vida: reflexión y praxis del

maestro colombiano acerca

de la lectura y la escritura

[Teacher training, life and history: Reflection and praxis of the Colombian

teacher about reading and writing]. Bogotá, CO: Plaza y Janés.

Elbaz, F. (1990). Knowledge

and discourse: The evolution of research on teacher thinking. In C. Day, M.

Pope, & P. Denicolo (Eds.), Insights into teachers’ thinking and practice (pp. 15-42). London, UK: The Falmer Press.

Goodson, I. F. (2005). Learning, curriculum, and life politics.

New York, NY: Routledge.

Johnson, K. E. (1999). Understanding

language teaching: Reasoning in action. Boston, MA: Heinle

& Heinle.

Johnson, K. E. (2009). Second

language teacher education: A sociocultural perspective. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kelchtermans, G. (2009). Who I am in how I teach

is the message: Self-understanding, vulnerability, and reflection. Teachers and

Teaching: Theory and Practice, 15(2),

257-272.

Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., & Zilber,

T. (1998). Narrative

research. Reading,

analysis and interpretation. London,

UK: Sage Publications.

Marshall, C., & Rossman,

G. B. (1995). Designing qualitative research

(2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Mendieta, J. A. (2011). Teachers’

knowledge of second language and curriculum: A narrative experience. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’

Professional Development, 13(1), 89-110.

Muñoz, A. P., Palacio, M.,

& Escobar, L. (2012). Teachers’ beliefs about assessment

in an EFL context in Colombia. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development,

14(1), 143-158.

Polkinghorne, D. E.

(1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies

in Education, 8(1), 5-23.

Ricoeur, P. (1980). Narrative

time. Critical Inquiry, 7(1), 169-190.

Serna, H. M. (2005). Teachers’ own identities. Concocting

a potion to treat the syndrome of Doctor Jekyll and Edward Hyde in teachers.

Íkala, Revista

de Lenguaje y Cultura, 10(16),

43-59.

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in

teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2),

4-14.

Stenberg, K. (2011). Working with identities—promoting student-teachers’ professional

development (Doctoral dissertation). University of Helsinki,

Finland.

Wiseman, D. L., Cooner, D. D., & Knight,

S. L. (1999). Becoming

a teacher in a field-base program: An introduction to education and classrooms.

New York, NY: Wadsworth.

About the

Authors

Norma Constanza Durán Narváez holds an MA in Applied Linguistics to TEFL from

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas

and a Specialist in English Language Teaching from Universidad del Tolima (Colombia). Her research interests include

teacher learning and professional development. She is currently a full time

teacher in the B.Ed. in English program at Universidad del Tolima, Colombia.

Sandra

Patricia Lastra Ramírez holds an MA

in Applied Linguistics to TEFL from Universidad Distrital

Francisco José de Caldas (Colombia). She is a full-time EFL teacher at

Universidad del Tolima (Colombia). Her research

interests include teacher learning, professional development, and EFL

methodology and bilingualism.

Adriana María Morales

Vasco holds an MA

in English Didactics. She is a full-time EFL teacher at Universidad del Tolima (Colombia). Her main interests are research in

the field of EFL Methodology, Language Teaching and Learning processes,

Pedagogy and Teacher Education Programmes.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Visitas a la página del resumen del artículo

Descargas

Licencia

Los contenidos de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development son de acceso abierto y los cubre la Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional. Se autoriza copiar, redistribuir el material en cualquier medio o formato, siempre y cuando se conceda el crédito a los autores de los textos y a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development como fuente de primera publicación. No se permite el uso comercial de copia o distribución de contenidos, así como tampoco la adaptación, derivación o transformación alguna de estos sin la autorización previa de los autores y de la Editora de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Los autores conservan la propiedad intelectual de sus manuscritos con la siguiente restricción: el derecho de primera publicación es otorgado a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.