The Role of Songs in First-Graders’ Oral Communication Development in English

El papel de las canciones en el desarrollo de la comunicación oral en inglés de niños de primero de primaria

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n1.37178Palabras clave:

Speaking skills, teaching English in primary school, using songs (en)enseñanza del inglés en la escuela primaria, expresión oral, uso de canciones (es)

Descargas

PROFILE

Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

Vol. 16, No. 1, April 2014 ISSN 1657-0790 (printed) ISSN 2256-5760 (online)

doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n1.37178

The Role of Songs in First-Graders’ Oral Communication Development in English

El papel de las canciones en el desarrollo de la comunicación oral en inglés de niños de primero de primaria

Ivon Aleida Castro Huertas*

Colegio Tenerife—Granada sur IED, Bogotá, Colombia

Lina Jazmín Navarro Parra**

Colegio Nuevo Horizonte, Bogotá, Colombia

*ivoncastro09@yahoo.es

**lijazminnav@yahoo.com

This article was received on February 17, 2013, and accepted on October 19, 2013.

We report on an action research project aimed at developing oral communication in first-graders, using songs as a strategy for young learners to use and enjoy English. It was developed at a Colombian public school over three months. The teacher-researchers attempted to encourage students using simple and amusing songs to help them learn new vocabulary in English and develop oral skills from the very moment they began their literacy process. In this article, we attempt to share our findings obtained from data collected through direct observation, field notes, video recordings, and interviews that show the process followed by very young learners to acquire vocabulary by singing.

Key words: Speaking skills, teaching English in primary school, using songs.

Reportamos un proyecto de investigación cuyo objetivo era desarrollar habilidades en la comunicación oral en niños de primero de primaria, a partir del empleo de canciones como estrategia para usar y disfrutar el inglés. El estudio se llevó a cabo en un colegio público colombiano, durante tres meses. Las docentes-investigadoras trataron de motivar a los estudiantes con canciones sencillas y divertidas para ayudarlos a aprender nuevo vocabulario en inglés, a la vez que desarrollaban destrezas orales en la lengua inglesa desde el inicio de su proceso de alfabetización. En este artículo compartimos los hallazgos provenientes de los datos recogidos a través de observación directa, notas de campo, grabaciones de vídeo y entrevistas, que muestran el proceso seguido por los jóvenes estudiantes al adquirir vocabulario cantando.

Palabras clave: enseñanza del inglés en la escuela primaria, expresión oral, uso de canciones.

Introduction

As the document of standards in English (Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN], 2006) affirms, childhood has many advantages: from the morphological-biological aspects to children’s motivation, interest in learning new things, desire and need to communicate and understand the world, curiosity, spontaneity, and lack of fear of making mistakes. However, learning can be more effective if it is accompanied with funny and significant activities that involve movements, repetitions, and expressions that are engaging for children. Even given this, however, children can manage some skills of the foreign language they are learning, but they cannot express themselves orally in the foreign language because they do not have sufficient knowledge. With this project, we intended for first-graders at Nuevo Horizonte School to develop their speaking skills through songs in English because these kinds of activities are a way to enjoy learning English; in addition, because songs have natural and genuine language, they are a helpful resource for new vocabulary and cultural aspects that can also be introduced.

The Nuevo Horizonte School—where the project was applied—is located in Zone 1, in Usaquén (Bogotá, Colombia). It has a School Institutional Project (Proyecto Educativo Institucional = PEI)1 focused on developing communication skills and values for life. The students’ English levels are low because of the lack of specialists in that second language in the elementary school grades. At the secondary level, English teachers have made a number of efforts to expand the English level with the support of the City Secretary of Education, but the students are not interested in learning English because they have other needs and their lives do not demand the use of a second language.

In this context, and supported through an institutional project based in communication, we decided to carry out this teaching experience. From the full group, we chose an intentional sampling (Moreno Bayardo, 2000). Our intentional sampling consisted of 18 students whose parents signed the consent to participate in the research; they were in the first grade of the elementary school of groups 1A and 1B and studied in the afternoon shift.

Conceptual Framework

People typically think that learning a foreign language is better and faster if it starts from the moment children can use at least speaking and listening skills in their own mother tongues. However, it is necessary to keep in mind where English as a foreign language is going to be learned to eliminate certain misconceptions and to clarify the scopes of teaching English to young learners. The first aspect to take into account is how policies in education set teaching practices, the possible results depending on the conception of education, and the reasons to teach a foreign language. Cameron (2001) asserts that the classroom learning and teaching of foreign languages to young learners in their early ages are influenced by complex foreign language teaching policies created from the social, cultural, and political issues of any specified population.

A second aspect to take into account is the target population: children between six and seven years old are beginning the process of acquiring the Spanish linguistic code. According to Cameron (2001), learning a foreign language at the age of five involves the development of pronunciation and listening comprehension but no progress in the grammatical aspects; this is because learning a language goes hand in hand with cognitive development. Therefore, a project to be implemented with young learners must be clear about what types of skills the children are able to develop and what to expect in other aspects of the English learning process. This clarity is important because it also defines the pedagogical course of action.

Limitations in the English Teaching Task

Cameron (2001) proposes breaking with the pattern of four macro skills, based on the fact that young learners between five and seven years old are able to develop two main oral abilities: vocabulary and discourse, the first one understood as lexical acquisition, the appropriation of meaning, and the formation of meaning webs and the second conceptualized as efficiency in interaction. In first-graders’ language development, these two oral abilities prevail over the other language functions, and teachers must take into account basic principles to improve foreign language learning:

1. Children cannot learn if they do not understand; the words and activities themselves must make sense to children. Children under eight years old do not ask for further explanations; they proceed as though they understand and continue doing the activity, but there is not true learning.2. Teachers must consider children’s cognitive ages, using strategies to reinforce the foreign language learning; most of the time, repetition is necessary.

3. During the time that young learners cannot understand grammar rules, language acquisition takes place through games and activities based on their ages.

4. To develop discourse skills, it is imperative that the children participate and interact to use the language, and the first stage is to give children the tools to interact and develop them until they are pragmatically and sociolinguistically competent.

5. Children learn through experiences, and thus classroom activities are an opportunity for language acquisition in a meaningful context.

According to Cameron (2001), children must acquire listening habits as well to participate in discourse. Hence, it is imperative that children be good listeners, learning to respect speaking in turns and identifying stress, rhythm, and intonation depending on the intention of the communication. Later, teachers must focus on vocabulary acquisition and its use in discursive performances. As Nunan (1990) states, “we should encourage learners to take part in discourse, and through discourse, help them to master sentences” (p. 32).

The Use of Songs in the Learning Process

Games are activities that children take more seriously and devote more time to, which makes them the best strategy to use in the learning process with elementary school children. Classroom activities involving music “provide a link with home and school life and are often lively and fun” (Brewster, Ellis, & Girard, 1992, p. 174). The first stages of language acquisition take place through a pleasurable process with the support of physical interaction accompanied by visual, vocal, and facial expressions and gestures—all of which stimulate responses in the children—and repetition by the adults, and this is the moment when a child learns about his/her culture.

According to Brewster et al. (1992), some of the advantages of using songs in class can be perceived in the process and in the learners, as follows:

Process:• Variety is added to the range of learning situations.

• The pace of a lesson can be changed, thus maintaining learners’ motivation.

• More formal teaching can be “lightened,” thus renewing learners’ energy.

• “Hidden” practices of specific language patterns, vocabulary, and pronunciation can be provided.

• Any distance between teacher and learners can be reduced by the use of more light-hearted and “fun” activities.

• Areas of weakness and the need for further language work can be revealed.

• The classroom environment becomes more fun.

• Songs contain words and expressions of high-frequency use, and they offer repetition.

• Songs facilitate memorizing when they are associated with linguistic items.

Learners:

• Listening skills, attention span, and concentration are improved.

• Learner participation is encouraged, thereby giving confidence to shy learners.

• Learner-learner communication is increased, which provides fluency practice and reduces the domination of the class by the teacher.

• Vocabulary is continuously reviewed and improved.

• Pronunciation continuously improves with practice.

• Learners have fun while they are learning.

“A song is a very strong means of triggering emotions that contributes to socialization (a song is collective); appeals to the ear (one listens to himself while singing); engenders pleasure (reproduction of a sound, enjoyment of the rhythm) and helps to develop an aesthetic taste (expressing feelings and sentiments)” (Cakir, 1999, para. 2).

Method

According to Markee (1997) and Salcedo (2003), the project we developed is not only an implementation of a strategy but an opportunity for teachers to reflect about our classroom practices and to conduct research in situ and based on our own experience. We implemented the stages of action research based on Burns (1999), who quotes Kemmis and McTaggart as follows: “Action research occurs through a dynamic and complementary process, which consists of four essential ‘moments’” (p. 32):

1. Reflection: Based on our experience as language teachers, and observing the needs of our institutions, we identified one of the issues of interest to improve language processes. This first step entailed the analysis of a possible problem to solve or an issue to be improved. In our project, the main issue was developing oral skills in first-grade children between six and seven years old, taking into account that in these ages children are starting to develop their first language written skills.2. Planning: In this stage, we designed possible activities to develop oral skills, taking into account the participants’ ages and literacy levels and our intended objective. We chose songs as a teaching strategy and a source to motivate these young learners to develop oral skills. This stage also included the selection of data collection techniques, also taking into account the participants’ characteristics. Hence, we selected video recordings and field notes, which were recorded during the development of three lessons.

3. Action: We developed three lessons intended to exploit three songs with the students. The lessons consisted of using songs and consequently implementing complementary activities, with the aim of determining how much vocabulary students had learned from the activities and whether they were using what they had learned in other contexts or recognizing words in different types of exercises. The three songs that we chose were: Hello, What’s Your Name, Ten Little Indian Boys, and The Colors. The lessons were developed around these songs.

4. Observation and reflection: After collecting the data, we analyzed the results and designed new activities to adapt our actions to the findings.

Context

We conducted this action research with children between six and seven years old who were in first grade at a public school in Usaquén, a neighborhood located in the north of Bogotá. It is a neighborhood with many social and economic problems such as the immigration of many people from other parts of the country because of the displacement phenomenon that has led groups of families to move constantly from place to place. As a consequence, children do not have an educational sequence; the presence of gangs and children who grow without parents are common phenomena.

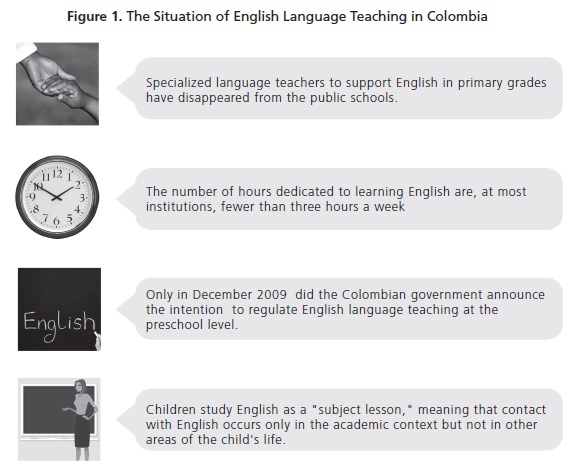

The children all came from poor families with low education levels; nearly all students had illiterate parents, and those parents who had some educational preparation did not have an approach to assisting their children in learning the English language. Additionally, most of the children did not have exposure to English. Finally, and as shown in Figure 1, in their very early steps of the educational system (kindergarten and preschool), students do not have a deep relationship with a second language. This is because of policies that do not promote teaching and learning second languages. In a small number of cases, the children’s previous knowledge of English was limited to only a few words.

Data Collection Procedures

Two factors were taken into account to define the techniques for data collection: First, this action research study entailed implementing an innovative proposal, and second, the students we worked with were the youngest at the elementary school.

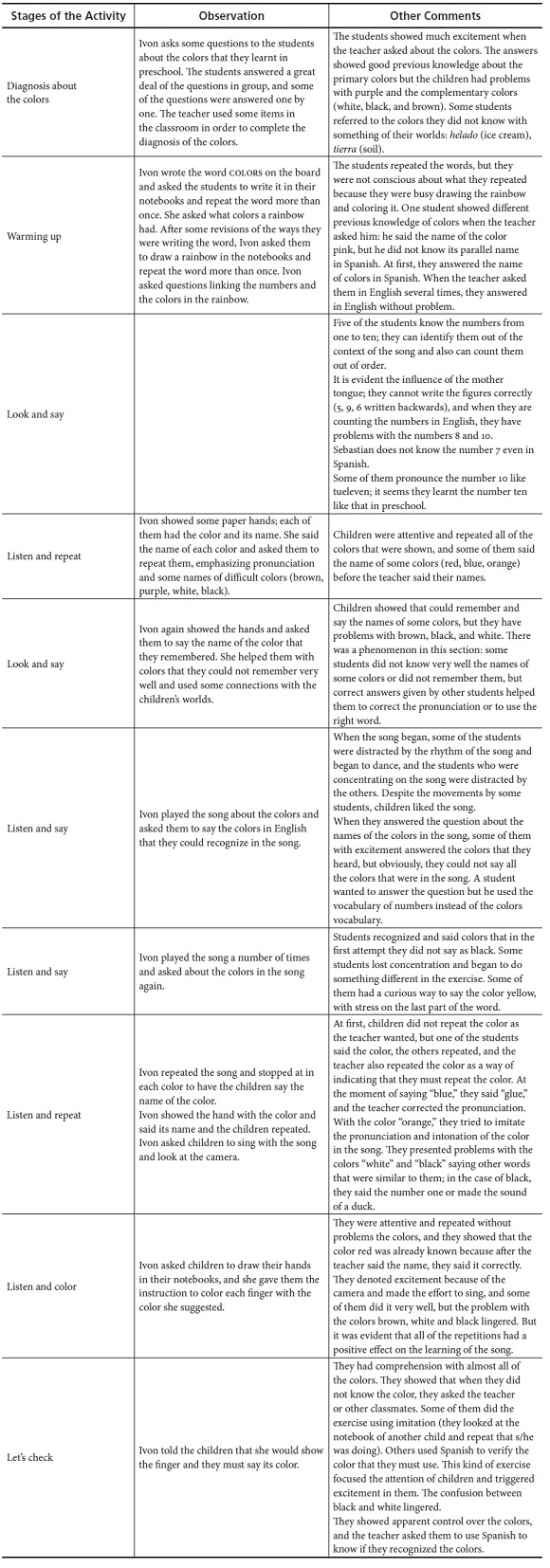

(1) Field notes: Through this technique, we attempted to take objective notes about the context of the classes, kept track of one of the objectives of the project—to make English learning enjoyable and fun for first-graders using songs—and recognized the variables that influenced learning. One example of this is given in Appendix A.

(2) Video recordings: It was important for the project to record the reactions and participation of the students during the listening and complementary activities. This gave us evidence of their progress and/or weaknesses.

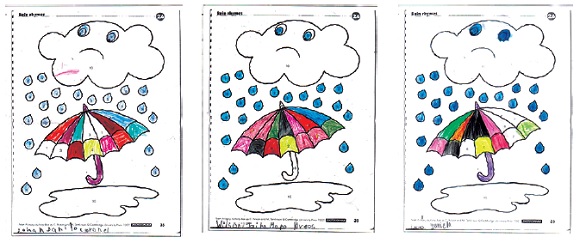

(3)Artifacts: Students’ production was part of the evidence to analyze whether the investigation objectives were achieved as well as the process of vocabulary acquisition. See examples of artifacts in Appendix B.

As already mentioned, the main objective of the present action research was to develop oral communication in first-graders at Nuevo Horizonte School using songs as a strategy for enjoying English. We carried out a series of activities planned to exploit three songs (see example in Appendix C) with a group of 18 students from first grade whose parents signed an authorization form to use the information about their children in the present work.

The project was conducted over a period of three months. During these sessions, field notes were taken and videos recorded. Both teacher-researchers were responsible for developing the activities, and whenever one of us was doing the activity with the children, the other took the notes and recorded the video. Additionally, at the end of each activity, we discussed the implementation and the results we were obtaining—the children’s reactions and performance—which helped us rethink how we were applying the lesson plans and their effectiveness compared with the objectives of this project.

Data Analysis and Results

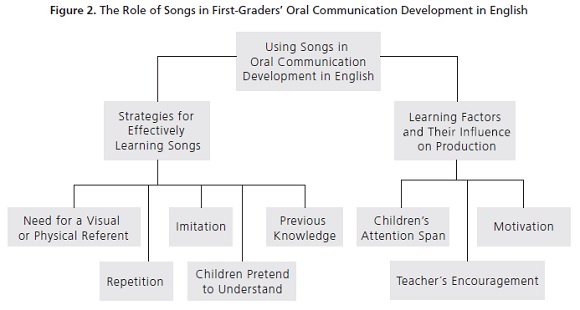

In the analysis of all of the collected data, we followed triangulation processes, which led us to identify main categories and certain subcategories. These are shown in Figure 2 and explained below.

The first category, strategies for effectively learning songs, showed us how children attempted to offset their limited knowledge of English and the strategies they used to obtain good scores or positive reinforcement as well as the strategies used by the teacher to obtain better results in class. From a different angle, the second category refers to all of the factors, whether internal or external, that could influence the children’s English production.

Strategies for Effectively Learning Songs

In this category, we examine some of the features that informed us about the strategies that help children to learn songs. The strategies found were: Need for a Visual or Physical Referent; Repetition; Imitation; how Children Pretend to Understand songs; and their Previous Knowledge.

Need for a Visual or a Physical Referent

Through the application of the three lessons, we noted that children could better understand each song’s vocabulary and meaning when we used a visual or a physical referent. That was the case with the lesson about colors. When Ivon was doing her warm-up and preparation for the song, she showed some paper hands and she said the corresponding names of the colors of each. The following samples from our field notes illustrate our findings:

Ivon again showed the hands and asked them to say the name of the color that they remembered. (Field notes, Session 5)

Ivon showed the hand with the color and said its name, and the children repeated. (Field notes)

The use of the previous strategies helped Ivon to ensure that students understood the name of the color, its meaning, and its pronunciation. We noticed that when students forgot the vocabulary, the visual or physical referent was sufficient to refresh the words and to thus increase their use of the English language.

For significant learning to take place, it is necessary to connect the concept to the learner’s previous knowledge and experience or to a real context. These kinds of connections are important for young learners because the visual and physical referents build meaning webs. In connection to this, Anglin, Vaez, and Cunningham (2004) state that “pictures used in conjunction with related verbal material can aid recall of a combination of verbal and pictorial information; . . . pictures will facilitate learning if they relate to relevant criterion test items” (p. 73). In our study, we saw that students understood the main words more quickly when we used visual or physical referents. In this way, they showed better understanding and learning of the concepts, and they could also use them properly outside of the context of the song.

Repetition

During the development of the lessons, we found it necessary to repeat the songs’ vocabulary or structures or other vocabulary related to the lesson itself. The teacher had the students repeat the vocabulary to ensure its understanding and their improved retention of it, as well as the structures taught during some of the lessons. The frequency of the required repetition had to be done depended on the students’ ages; this was the case when they were learning the song about the numbers and the colors:

Lina repeats the lyric line by line, emphasizing the pronunciation of “LITTLE” and pointing to the number and the Indian.

Ivon showed the hand with the color and said its name, and the children repeated. (Field notes)

According to Cameron (2001), it is important to keep in mind students’ cognitive ages and to adopt language learning strategies consistent with the skills expected for their stages. Hence, because these children were between six and seven years old, some repetition was necessary. This was the case when they were learning the song about the numbers:

Lina asks them to repeat the numbers forwards at the time that she points to the image. Then she asks them to repeat backwards. (Field notes)

In this way, children could say more vocabulary that at the beginning they did not know or understand.

Similarly, the frequency with which we exposed children to the vocabulary, pronunciation, and structures through repetition allowed us to increase the probability that the children would acquire or learn the content we wanted to teach them. We also noted that learners could make significant connections between form and meaning. In connection to this, Skehan (1998) wrote:

Repetition in what we hear means that the discourse we have to process is less dense; repetition in the language we produce provides more time to engage in micro and macro conversational planning. In acquisitional terms, repetition in conversation can serve to consolidate what is being learned, since the conversation may act as an unobtrusive but effective scaffold for what is causing learning difficulty. (p 33)

Imitation

At the time that we implemented the lesson plans, some children used imitation to learn a word, give a correct answer, or pronounce the words or sentences the ways they were pronounced in the original source. At times, we noticed that this strategy gave them more confidence because they saw our positive reactions to some of their partners and they imitated the same behavior to receive the same reactions from us.

We also noticed that imitation was present in two ways: the first was the children’s copying each other to give correct answers. For example, during the lesson plan about colors, the children did not say the colors as we told them to. One of the children would say one of the colors and receive positive feedback from the teacher. As soon as this happened, the others repeated the same word and used the same strategy with the other difficult vocabulary. Another example is shown below:

Some of them did the exercise using imitation: They looked at another child’s notebook and repeated what she/he was doing. (Field notes)

This kind of imitation could result in the children’s learning certain words or the whole song, but it could also fail:

At first, children did not repeat the color as the teacher wanted, but one of the students said the color and the others repeated. (Field notes)

The second way was a path that students followed to reach the pronunciation or structure given in the song. This was the case with the lesson plan about “your name.” The children listened to the song and realized that the structures previously presented by the teacher were in the song. When the teacher asked “What’s your name?,” they immediately imitated the answer given in the song.

Imitation is the first step and first evidence of progress of the development of the child’s intelligence. Moreover, it is a technique of assimilating and accommodating the external inputs or stimuli that are given to children from their worlds, in our case, songs and vocabulary. With regard to this, Piaget (2003) wrote:

The extent to which the schemas integrate new elements determines how far accommodation to these elements can be continued as imitation when the models presented are identical with the original elements . . . accommodation to new data keeps pace with the ability to recapture them through reproductive assimilation . . . he is capable of reproducing them through circular reactions. (p. 8)

Children Pretend to Understand

Throughout the three lessons, we saw children following the song only for pleasure. Children showed that they liked the rhythm of each song, which made them try to sing whether they knew the song or not. This was the case with the next sample:

Almost all of them seem to know the song and repeat it without music. But not all the children sang; they only repeated some relevant words and simulated that they were singing. When the song was played, they tried to sing and did some movements following the music. (Field notes)

However, we did give the students positive reinforcement each time they sang the song or they had an external motivator (camera) that made them sing. They pretended that they had learned the song quickly, and they moved their lips as if they were singing or sang with sounds or imaginary words that had the same rhythm and were similar to the words in the song. The following example reflects this:

From this part on, Ivon is in charge of recording with the video camera. She moves all over the room and students keep singing. Some like to face the camera, pretending they are really singing!!!! . . . Almost all of them seemed to know the song and repeated it without music. But not all the children sang; they only repeated some relevant words and simulated that they were singing. (Field notes)

Previous Knowledge

The pronunciation and vocabulary acquired in preschool English classes influenced the learning of some of the new words that we sought to teach through the songs. When we were teaching the lesson about numbers, in the diagnosis, some of the children showed that they knew some numbers. When we showed them the number ten (10), some students screamed “tueleven” [sic]. When the teacher said the correct name of the number, the children insisted with the same pronunciation, as shown in the following example:

Some of them pronounce the number 10 like “tueleven”. It seems they learnt number ten like that in preschool. (Field notes)

According to Gass and Selinker (2008), previous knowledge can include knowledge from the native language or a second language or from universal knowledge. Hence, it must be understood as broad knowledge acquired from the child’s entire world. Related to this fact, we noted another interesting aspect of previous knowledge during the lesson about colors. In the warm-up, we showed the children a rainbow and asked them the names of the colors in English. For example, when teacher Lina asked about the complementary colors (pink, gray, brown, black, and white) while pointing at them, a boy answered the color pink, but he was not sure about the translation in Spanish.

Another case of the use of previous knowledge was during the final activity in the colors lesson. We expected the children to activate the knowledge that they had acquired from the song using drawings of a cloud, rain drops, and an umbrella. Children had to color the numbers into each of the drawings according to given instructions. It was evident that most of the students did not remember some of the mentioned colors so they used the previous knowledge strategy and used the same color they had used for the previous number (see Appendix B).

Learning Factors and Their Influence on Production

The second category that we found was the learning factors and their influence on production, in our case, oral production. In this category, we examined how some of the children’s own internal factors positively or negatively impacted their oral production. These factors were: Children’s Attention Span, Teacher’s Encouragement, and Motivation.

Children’s Attention Span

We found that the children’s attention span was influenced by factors such as their ages, the kind of input, and the simultaneity of activities. First, let us remember that our participants were a group of children from six to seven years old. Because of the students’ ages, the long sequences of the activities and sometimes the number of repetitions to learn a song caused them to lose interest in the song, in the images and in the process that we were carrying out. This was the case with the lesson about numbers. We repeated the song Ten Little Indian Boys, which had a length of one and a half minutes, nearly four times. We recorded: “The song ‘Ten Little Indians’ seems to be too long for them!!!! They are tired and start to yawn” (Field notes). We also observed that the characteristic sound made for Indians distracted them: “They keep doing the sound of Indians” (Field notes).

Relatedly, we noticed that the children’s attention when they were learning vocabulary could be affected by the coincidence between the vocabulary exercise and another attractive activity. In our case, this happened when one of us was doing the warm-up; she wrote the word “COLORS” on the board and asked the students to write it in their notebooks and repeat the word more than once. We asked what colors a rainbow had. After some revisions of the way they were writing the word, we asked the students to draw a rainbow in their notebooks and to repeat the word more than once. The following shows what happened in this exercise:

The students repeated the words, but they were not conscious about what they repeated because they were busy drawing the rainbow and coloring it. (Field notes)

In another activity, the number of repetitions of the song and the fact that the teacher stopped the song constantly to emphasize the names of the colors distracted the children: “Some students lost concentration and began to do something different to the exercise” (Field notes).

Another relevant aspect was the kind of input given to the children, which demonstrated that the children’s enjoyment of the music in the song could distract them. The next sample showed us this case:

When the song began, some of the students were distracted by the rhythm of the song and began to dance, and the students who were concentrating on the song were distracted by the others. (Field notes)

In another case, however, the kind of input or activity helped us capture the children’s concentration. In the lesson about colors, Ivon asked the children to draw their own hands in the notebook and to color the fingers according to her instructions. We observed that activities for which the children had to follow instructions were helpful for gaining their attention. The following extract gave us an example of the last assertion:

Ivon asked the children to draw their hands in their notebooks, and she gave them the instruction to color each finger with the color she suggested. This kind of exercise focused the attention of the children and triggered excitement in them. (Field notes)

Teacher’s Encouragement

Another factor that we found in the data analysis that could affect the children’s oral production was the teacher’s reinforcement of any of the children’s efforts. Often, children do their classroom activities looking for their teacher’s approval, and whether they receive it determines their progress or setbacks in learning. On this, Brewster et al. (1992) remark:

The effort which the pupils put into participating and being attentive must firstly be rewarded by positive encouragement on the part of the teacher, and then followed up by provision of the necessary help to achieve improvement in those areas where inaccuracies occur, whilst at the same time avoiding making any potentially crippling criticism. (p. 13)

We could see this in the lesson plan about numbers. Although some children knew the numbers from one to ten, they had to make some effort to recognize, pronounce, and follow the numbers from six to ten. We congratulated them because of their efforts, and they showed happiness and the desire to improve their next attempts to do these activities as well as other exercises about the same topic. We noticed this in the next example:

The song is repeated line by line. It is ok with the numbers 1, 2, 3 but from four to ten, it is a mess. Lina congratulates them for the first attempt and makes them repeat the lyrics from four to nine. They seem to be ready to sing the whole song; their pronunciation is better. (Field notes)

Motivation

According to Brewster et al. (1992), motivation is directly related to learners’ interest in the learning process and in how and what we teach them. In our case, the novelty and the discovery of another language through the three songs and the corresponding activities were motivating forces for our students. This was noticed from the first time Ivon arrived in the classroom, introduced herself to the children, and explained both the activities and the use of the camera:

Good reactions when the teacher was introduced; students in general show interest. Some asked if Ivon is also a teacher and if she is going to teach them something. [As mentioned at the beginning, Lina was the preschool English teacher and she worked collaboratively with Ivon to develop the project]. Ivon explains that we want them to participate and have fun. Also, she tells them that we will use a video camera in order to make a film of the classes and the videos are important. We also promise to show them the film later on. (Field notes)

In the numbers lesson, the children showed motivation because of the novelty of the presence of a camera in the classroom, and they made their best efforts to do the actions asked by the teacher. As can be read below, they used strategies to do all the activities as best they could:

Good pronunciation. From this part on, Ivon is in charge of recording with the video camera. She moves all over the room and students keep singing. Some seem to enjoy facing the camera, pretending they are really singing!!!! (Field notes)

Another example that demonstrated their motivation was when Ivon asked them the colors that they knew. As acknowledged by Brewster et al. (1992), one of students’ interests is the pleasure they have when they learn or understand meanings, pronunciation, and so forth. Following on this, the children realized that they knew the vocabulary and they could account for the knowledge they had. An example of this finding follows:

Ivon asks some questions to the students about the colors that they learnt in preschool. The students answered a good number of questions in group, and some of the questions were answered one by one. The students showed much excitement when the teacher asked the colors. The answers showed mastery of previous knowledge.

Conclusions

As teachers, we have to know the possibilities and scopes of teaching English to very young learners as well as the cognitive processes of language learning at this stage. It is very likely that the lack of experience with young learners can cause us to lose sight of the ways children learn and communicate. This is evident in the moment of giving children instructions and in the kinds of activities we should plan for them.

The cognitive development of first-graders allows them understand and produce discourse and vocabulary in very basic ways in the English language, although they might not be able to understand complex grammatical structures. In our experience, the children made evident the acquisition of new vocabulary and the creation of meaning webs in their first attempts to communicate orally in English: pointing to the object the teacher referred to in the foreign language, coloring the right number, establishing relationships between colors and referents from the environment, following instructions, and answering basic questions such as: What color is this? What is your name? What is this number?

Finally, we want to note the need to begin the English learning process from early stages, with realistic goals, not pretending that we will manage grammar but teaching that enjoying a second language can be something new and fun. Throughout our action research, we noticed that the use of songs in teaching English enhanced positive feelings such as happiness, self-confidence, and enjoyment.

1The PEI of Nuevo Horizonte School is entitled “Un nuevo horizonte, una esperanza de vida: comunicación y valores” (A new horizon, a new life expectation: Communication and values).

References

Anglin, G. J., Vaez, H., & Cunningham, K. L. (2004). Visual representations and learning: The role of static and animated graphics. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 865-916). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Brewster, J., Ellis, G., & Girard, D. (1992). The primary English teacher’s guide. London, UK: Penguin.

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cakir, A. (1999, noviembre). Musical activities for young learners of EFL. The Internet TESL Journal, 5(11). Retrieved from http://iteslj.org/Lessons/Cakir-MusicalActivities.html

Cameron, L. (2001). Teaching languages to young learners. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gass, S., & Selinker, L. (2008). Second language acquisition: An introductory course. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group.

Markee, N. (1997). Managing curricular innovation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (2006). Estándares básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras: Inglés [Basic standards of competence in foreign languages: English]. Bogotá, CO: Imprenta Nacional.

Moreno Bayardo, M. G. (2000). Introducción a la metodología de la investigación educativa II [Introduction to educational research methodology II] (2nd ed.). Mexico, MX: Editorial Progreso.

Nunan, D. (1990). Designing tasks for the communicative classroom. (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Piaget, J. (2003). Play, dreams, and imitation in childhood. London, UK: International Library of Psychology.

Salcedo, R. A. (2003). Experiencias docentes, calidad y cambio escolar [Teachers’ experiences, quality, and educational change]. Retrieved from http://www.lablaa.org/blaavirtual/educacion/expedocen/expedocen8a.htm

Skehan, P. (1998). A cognitive approach to language learning. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

About the Authors

Ivon Aleida Castro Huertas is an English and Spanish teacher at Colegio Tenerife—Granada sur IED in Bogotá, Colombia. She holds a BA in Languages from Universidad Pedagógica Nacional (Colombia) and she has an MA in Hispano-American Literature from the Instituto Caro y Cuervo (Colombia).

Lina Jazmín Navarro Parra holds a BA in Spanish and Languages (English and French) from Universidad Pedagógica Nacional (Colombia). She is the English teacher at the elementary school Nuevo Horizonte in Bogotá, Colombia.

This paper reports on a study conducted by the authors while participating in the PROFILE Teacher Development Programme at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá campus, in 2010. The programme was sponsored by Secretaría de Educación de Bogotá, D.C. Code number: 1576, August 24, 2009, and modified on March 23, 2010.

Appendix A: Field Notes Sample

Nuevo Horizonte School

Session: 5

Date: April 19, 2010

Time: 4:30 p.m. (one hour programmed)

Place: First grade classroom

Appendix B: Examples of an Activity in Lesson Five About Colors

Appendix C: Sample of Activities Developed in Lesson 1

Activity 1: Ten Little Indian Boys

Level: First Grade

Age of Group: Between 5 to 7 years old

Time: Two classes of 30 minutes approximately

Aims:

– Learn and recognize the pronunciation of numbers from one to ten.– Develop the general and specific understanding of the contents of a song: main characters, the learned vocabulary, etc.

– Have fun and feel a sense of achievement.

Description: The children learn a song about the numbers from one to ten and use them outside of the song.

Skills: Listening and speaking skills.

Materials:

– A CD with the song– A tape recorder

– A sheet with the image of an Indian

– Ten pieces of cardboard with the numbers from one to ten and their names

– Copies of a “BINGO” game

In class:

Warm-up

– Show the students a picture of an Indian.– Ask them about the name of the picture (T: What’s he? Ss: un indio).

– Say the name in English (T: He’s an Indian).

– Repeat the name again and make the students sometimes repeat after you and sometimes say the word alone.

– Ask them again the name of the picture and emphasize the answer in English.

– Ask them about the sound an Indian makes.

– Explain that you will make the sound and they must say INDIAN. Then, you say INDIAN, and they will make the sound.

Sing

– Prepare pictures with the numbers from 1 to 10.– Play the CD. Sing the song and have the students pay attention what you show them.

– Play the CD several times repeating the previous exercise.

– Play the CD and ask students to sing along with you.

– Display the pictures with the numbers around the classroom.

– Explain that the students will point to the picture of the number when they hear it in the song. Repeat this exercise more than once.

– Invite a volunteer to do the previous exercise in front of the partners. Repeat the exercise with another student.

– Without the song, point to each picture of a number and ask them the name of each one. Do this more than once.

– Play the CD and encourage them to sing alone.

Act out

– Ask students to form groups of ten boys or girls.– Explain that they will sing the song and act as Indians, dancing according to the numbers of Indians in the song.

Play

– Give the students a photocopy with a board divided into eight small boxes.– Ask them to choose eight from the ten numbers they learned and write them in the boxes, putting one number in each box without repeating any.

– Explain that they will play BINGO. You will say a number, and if they have this number on their board, they will draw an X on it. The first student that sings BINGO is the winner. Repeat the game more than once to give many students the chance to win.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Glenn M. Davis. (2017). Songs in the young learner classroom: a critical review of evidence. ELT Journal, , p.ccw097. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccw097.

2. Hyun-Ju Kim, Hyun Ju Chong, Mihye Lee. (2024). Music listening in foreign language learning: perceptions, attitudes, and its impact on language anxiety. Frontiers in Education, 9 https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1372786.

3. Jie Gao. (2024). Designing L2 pronunciation instruction activities for primary school learners. Language Teaching for Young Learners, https://doi.org/10.1075/ltyl.00060.gao.

4. Mei Peng, Yangyang Shi, Ping Zhang. (2023). ELT coursebooks for primary school learners. Language Teaching for Young Learners, 5(1), p.59. https://doi.org/10.1075/ltyl.00031.pen.

5. Hazar Eghbaria-Ghanamah, Rafat Ghanamah, Yasmin Shalhoub-Awwad, Avi Karni. (2021). Recitation as a structured intervention to enhance the long-term verbatim retention and gist recall of complex texts in kindergarteners. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 203, p.105054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2020.105054.

6. Ping Zhou. (2024). Real time feedback and E-learning intelligent entertainment experience in computer English communication based on deep learning. Entertainment Computing, 51, p.100752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2024.100752.

7. Ow Su Sinn, Cheong Ku Wing. (2024). Twenty-first century learning skills and music engagement among young children: a systematic review. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, , p.1. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2024.2385835.

Dimensions

PlumX

Visitas a la página del resumen del artículo

Descargas

Licencia

Los contenidos de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development son de acceso abierto y los cubre la Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional. Se autoriza copiar, redistribuir el material en cualquier medio o formato, siempre y cuando se conceda el crédito a los autores de los textos y a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development como fuente de primera publicación. No se permite el uso comercial de copia o distribución de contenidos, así como tampoco la adaptación, derivación o transformación alguna de estos sin la autorización previa de los autores y de la Editora de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Los autores conservan la propiedad intelectual de sus manuscritos con la siguiente restricción: el derecho de primera publicación es otorgado a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.