The Feasibility of Assessing Teenagers’ Oral English Language Performance with a Rubric

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n1.43203Palabras clave:

Alternative assessment, oral performance, practicality, rubrics, teaching English to teenagers (en)Descargas

This article reports the experience of a study group in a public university in Colombia, formed mostly by academic coordinators who worked in the design of assessment rubrics. Its focus is on the experience of the academic coordinator of the English program for teenagers, who concentrated on implementing the rubric to assess the students’ oral performance. The data collection instruments used were the rubric and interviews with the teachers and students. The results are related to the impact of the assessment rubrics on the program’s teachers regarding practicality.

En este artículo se presenta la experiencia de un grupo de estudio en una universidad pública colombiana, conformado principalmente por coordinadores académicos que trabajaron en el diseño de rúbricas para la evaluación. El presente trabajo se centra en la experiencia de la coordinadora del programa de inglés para jóvenes, quien usa las rúbricas para evaluar el desempeño oral de los estudiantes. Los instrumentos de recolección de datos fueron la rúbrica y entrevistas a los profesores y estudiantes. Los resultados están relacionados con la viabilidad y utilidad de la rúbrica.

PROFILE

Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

Vol. 16, No. 1, April 2014 ISSN 1657-0790 (printed) ISSN 2256-5760 (online)

doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n1.43203

The Feasibility of Assessing Teenagers’ Oral English Language Performance with a Rubric

La viabilidad de evaluar el desempeño oral de los adolescentes en inglés con una rúbrica

Diana Pineda*

Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia

This article was received on March 29, 2013, and accepted on October 18, 2013.

This article reports the experience of a study group in a public university in Colombia, formed mostly by academic coordinators who worked in the design of assessment rubrics. Its focus is on the experience of the academic coordinator of the English program for teenagers, who concentrated on implementing the rubric to assess the students’ oral performance. The data collection instruments used were the rubric and interviews with the teachers and students. The results are related to the impact of the assessment rubrics on the program’s teachers regarding practicality.

Key words: Alternative assessment, oral performance, practicality, rubrics, teaching English to teenagers.

En este artículo se presenta la experiencia de un grupo de estudio en una universidad pública colombiana, conformado principalmente por coordinadores académicos que trabajaron en el diseño de rúbricas para la evaluación. El presente trabajo se centra en la experiencia de la coordinadora del programa de inglés para jóvenes, quien usa las rúbricas para evaluar el desempeño oral de los estudiantes. Los instrumentos de recolección de datos fueron la rúbrica y entrevistas a los profesores y estudiantes. Los resultados están relacionados con la viabilidad y utilidad de la rúbrica.

Palabras clave: desempeño oral, enseñanza de inglés a adolescentes, evaluación alternativa, rúbricas, viabilidad.

Introduction

Language assessment is a complex issue because it implies the great responsibility of teachers to assess what students are able to do with language and also because assessment may be used by the administration to evaluate the effectiveness of the teaching. Nonetheless, the average teacher has to work with a large number of students per class, which makes evaluation a very time-consuming task that results in the application of very traditional assessment instruments that do not favor the students’ learning or let the teachers know what students are really able to do with that learning. Although some of those assessment instruments, such as written exams or multiple-choice quizzes, seem more practical, they may sometimes lack validity and reliability. In the field of English language teaching, this reality can be worse if we take into consideration that English teachers are asked to assess communicative competence in terms of what students are able to do regarding listening, speaking, reading, and writing. At other times, despite the use of alternative instruments, such as interviews or writing tests, the criteria used to assess may be uncertain and students seem to care only about their grades without reflecting on their learning achievements. To face this reality, assessment rubrics seem to be a reliable, practical and formative instrument for both teachers and students.

In this article, I will only refer to practicality as part of my experience carrying out my master thesis within the context of a research project developed by a team of different academic coordinators of programs in the Centro de Extensión (Extension Center) of the Escuela de Idiomas (School of Languages) at the Universidad de Antioquia. My project aimed to examine to what extent the use of oral performance assessment rubrics can be practical and reliable when the criteria are decided by a group of teachers or, as in our case, the members of the study group, which included two of the program’s teachers. At the time the study was carried out, I was the academic coordinator of the Programa de Inglés para Jóvenes (English Program for Teenagers, from now on named PIJ); I assumed the responsibility of becoming part of this study group and conducted research on a topic that could help us improve our assessment practices. The piloting of the rubric to assess students’ oral performance in the program led me to realize the program teachers’ need to be educated in a curriculum innovation related to assessment.

At the end of the work, the reader may draw some conclusions to make decisions regarding how a rubric facilitates the teacher’s work. The results of this research will be useful for English teachers who have to daily accommodate great assessment demands, especially those in Colombia, who are regulated by recent language policies under which competent language learners are expected to reach, by the end of high school, level B1 of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) by the year 2019. In my opinion and based on my experience, although assessment is clearly a key issue in determining what students are able to do with the language, it is by means of the rubric that we can make evaluation something well founded, practical for teachers and formative for students.

Context

The PIJ was created in 2000 at the Extension Center of the School of Languages at the Universidad de Antioquia in Medellin. The program had 33 teachers and 450 students at the time this project was carried out. Teachers should ideally hold a bachelor’s degree in teaching English, but very frequently the program hires advanced students from the university translation and teaching undergraduate programs. Students belong to the medium-low and medium-high social strata. Students’ ages were between 10 and 18. Classes are four hours each weekend, and the courses last 64 hours. Parents have high academic and professional expectations for their children when they enroll them in the program. English in the program is taught for communication and, to some extent, for academic purposes.

The teaching methodology the program proposes embraces the communicative language teaching approach, whole language and project work, a component of autonomy, and a content-based syllabus. Included in the registration fee, the program offers students a tutorial service for those who need to work on specific needs outside of class, a two-hour read-aloud session every semester and a chat session to discuss in English about a topic of students’ interest.

Assessment in the program claims to be formative, summative, and alternative. It is formative because we evaluate students in different ways and give them feedback to contribute to their learning processes. It is summative because administratively, we have to choose certain moments to check whether students have accomplished the goals proposed and have passed or failed an assessment task or the course. The assessment is also alternative because we encourage self- and peer-assessment to help students reflect on their learning processes and achievements and make goals. The grading system in the program is numerical, from 0.0 to 5.0, and the passing score is 3.0. The assessment includes a section for follow-up where teachers typically include four-skill quizzes, oral presentations, homework and class participation, among others. Each teacher is free to decide how many grades they will include in this section, except for the first oral assessment tasks, which are mandatory for all of the courses.

Participants

The participants in this study were 39 out of the 41 students enrolled in the four level-one English courses of the PIJ during the second semester of 2009. They were 16 boys and 25 girls, and their ages ranged from 10 to 15. The teachers who participated in the project were four, two with little experience in teaching (both students of the translation and teaching program at the Universidad de Antioquia) and two already graduated from the same teaching program and with some teaching experience. A number of other experienced teachers from the program participated voluntarily in a survey after a year of the rubric’s implementation to assess the students’ oral performance. The academic coordinator of the PIJ holds a bachelor’s degree from the same university; she has been an English teacher for 12 years in public and private institutions of the city and has some experience in research.

Data Collection Techniques and Data Analysis

To focus my attention on the feasibility of assessing with a rubric, I analyzed the data following Burns’s (1999) steps. I collected the information used to identify the use of the rubric: An interview with one of the teachers and the questionnaire the teachers completed (see Appendices A and B). The decision to collect these data was made based on the research question. Once the data were assembled, I began to read them and underlined what caught my attention in relation to the research question. At the same time, I wrote out key words that helped me identify the information selected. After that, I reread the information with a focus on what I had already underlined, and I defined the categories and subcategories for which I had written key words. Sometimes, I also wrote insights that could later help me to interpret the analyzed data.

Once I had coded the data, I began to establish relationships between the categories obtained from the different data sources. I organized the codes in a way that would make sense when presenting and explaining what had happened with the information in relation to the research question. During the analysis, I kept track of the recurrences and then took them into account to explain the reasons for the most and the least recurrent categories. To establish relationships among the categories identified in the data, I put together all the evidence of the categories.

After I had analyzed and organized the information, I attempted to understand what the data were telling me and compared my conclusions with the theory I had previously read about evaluation. Sometimes I revised the evidence under the categories to determine whether my evidence truly fit the category and to identify the connections with the theory. During this stage, I also shared what I was finding with some of my colleagues in the study group on rubrics and with other teachers in the program. Finally, I organized my ideas, describing the data analysis and its interpretation and connecting them with the context and the theory to understand the reality of what had happened during the rubric implementation. I also presented the findings to the research participants and shared the results at the study group meeting to validate my findings.

Procedure

When I became the academic coordinator of the English Program for Teenagers, in July 2007, I noticed that the program was not exempt from the same problems that Arias and Maturana (2005) had found in the local context of the foreign language teaching programs they had investigated. In March 2008, I invited the teachers of the PIJ to join a study group to work together and learn about a topic of our interest. To my surprise, assessment was the most recurrent topic, and teachers stated that it was the area in which more training and reflection were needed. The problem with assessment became even more salient when teachers switched their groups to assess students’ oral performance, which happened twice every semester for levels four to seven. Some teachers complained that the teachers evaluating their group over- or underestimated the students’ performances, resulting in incoherence or lack of reliability in the scores. At that time, the program offered the teachers a grid with five criteria: listening, content, pronunciation, accuracy, and fluency, but the teachers frequently misinterpreted the meaning of each criterion. When I realized this, I asked senior teachers and previous coordinators what they meant exactly with those criterion labels and prepared definitions to share with all of the teachers. Nevertheless, not all of the teachers read the information they were given, or they sometimes made their own interpretations of it. With that problem in mind, I came up with the following research question: To what extent can a rubric be a practical and reliable assessment instrument for teachers when assessing their students’ oral performance? This article will only reflect what happened with practicality.

Actions

By August 2008, a colleague had presented a research proposal to define evaluative tasks and to design rubrics to assess the communicative competence in the Extension Center or Sección Servicios (Services Section) of the School of Languages of the university where we worked. His objective was to invite teachers and coordinators of these two sections to join a study group in which we could develop the proposal while some of the participants learned how to do research. Because this proposal aligned with the issue of assessment that we had been working on in the program study group, I invited teachers from the study group on assessment to join the new study group on rubrics as a way of giving continuity to our work and directing our efforts toward a specific product, namely, the definition of assessment tasks and rubrics in the PIJ. One of the teachers accepted and the others left the group, either for work schedule or personal reasons.

In September 2009, after a long discussion of readings in the study group about the communicative competence concept, the oral task options, the definition of rubric, and the revision and reformulation of the course contents for level 1, the four level-one teachers and I implemented the first oral assessment rubric (see Appendix C). Then, we reflected and analyzed what had happened and what we needed to improve. The main conclusion that we reached was that the teachers needed more training in the use of rubrics. Based on that, the three Extension Center coordinators prepared a lecture and a workshop for teachers during two all-day in-service sessions in 2009 during which teachers received training on the use and design of assessment rubrics.

In 2010, I started a training program on rubrics with PIJ teachers. The aim was to define oral evaluative tasks and rubrics at the same time as they received training on how to prepare these assessment instruments and use them. During the sessions, we negotiated the assessment task based on previous readings that the teachers were required to do, taking into account the course contents, the students’ ages, their cognitive levels, and their linguistic skills. Once the rubric was complete, the teachers were asked to present the evaluative task and the rubric to their students and to negotiate them. In this way, we not only ensured that the teachers received proper training in a new curricular change in assessment, but we also facilitated the construction of assessment instruments that were more formative and democratic. As a result of this training that semester, most of the teachers designed a rubric to assess students’ oral performance in the second part of the course. For the second semester of 2010, this training was only carried out with new teachers, and those who had already received the training during the first semester of the year had to define the two oral assessment tasks and rubrics to be used during the course, send it to the coordinator to be revised, receive feedback and introduce the changes, if necessary.

Literature Review

Evaluation, Assessment, and Testing

Evaluation, assessment, and testing are concepts that should be defined to understand their differences and avoid confusion. According to Arias, Estrada, Areiza, and Restrepo (2009), evaluation refers to collecting information about the factors that affect the teaching and learning processes such as: institutional policy, methods, course programs, teaching, materials, resources, program effectiveness, student performance, and learner satisfaction. This information is collected, analyzed and interpreted for different purposes, for instance, to monitor a teaching proposal, make a decision on a textbook choice, examine teachers’ practices, or determine students’ progress on their communicative competence based on what the program offers. The term evaluation includes assessment, but the latter is more oriented to communicative and strategic competence. The assessment is formal when evidence of students’ performance is maintained systematically. On the contrary, informal assessment comes spontaneously from the teacher to contribute to the student’s improvement, and there is no register of it. Although both methods are valid, Arias et al. (2009) recommend being rigorous and systematic in informal assessment. In this way, it is easier for the teacher to have evidence of the student’s progress. Testing is simply a technique used to revise, measure, or monitor a student’s communicative competence. In this sense, a test is used to measure a learner’s performance or linguistic knowledge. Arias et al. (2009) proposed a combination of assessment and testing to obtain a more integrative and formative view of a student’s performance.

Alternative assessment

Aschbacher, Aschbacher and Winters, and Huerta-Macias (as cited in Brown and Hudson, 1998), established some features of alternative assessment:

• Students are required to do something.

• Real-world contexts are used.

• It is included in day-to-day class activities.

• Students’ assessment is based on what they normally do in class.

• Meaningful tasks are used.

• The focus is on both process and product.

• Higher-level thinking and problem-solving skills are targeted.

• Information about students’ weaknesses and strengths is offered.

• Multiculturalism is sensitive when it is properly administered.

• It is assured that the scoring is done by humans not by machines.

• Standards and rating criteria are transparent.

• Teachers are allowed to perform new roles.

Brown and Hudson (1998) avoided using the term alternative assessment and preferred alternatives in assessment because the former implies three things: (a) that it is a new assessment procedure, (b) that the assessment procedures are completely separate and different, and (c) that they do not follow all the rigor of test construction and decision making. Lynch (as cited in Brown, 2004) highlights the ethical potential of alternatives in assessment because they promote fairness and balanced power relationships between teachers and students. According to Brown and Hudson, alternatives in assessment, include selected-response, constructed-response, and personal-response assessment. Selected-response assessment includes true-false, matching, and multiple choice and will not be explained here because these are not related to oral production, which is the main focus of this paper.

Constructed- and Personal-Response Assessments

Constructed-response assessments are those for which students are required to produce language by speaking, writing, having listening and speaking interactions such as in interviews, or reading two texts to write an essay to contrast them. That is the reason this type of assessment is more appropriate for measuring productive skills. There are three types of constructed-response assessments commonly used in language testing: fill-in, short-answer, and performance assessment; because the focus of this experiment is on oral assessment, I will only refer to the third one. In performance assessments, students are required to carry out authentic, real-life tasks. Some examples of performance assessments are essays, interviews, problem-solving tasks, role-plays, or group discussions. Performance assessments comprehend three characteristics: the performance of a sort of task, the task’s authenticity and the qualification of the rater.

Performance assessments contribute to measuring students’ abilities to respond to real-life language tasks, value students’ true language abilities, and reflect on how students will perform in future real-life language situations. In addition to this, performance assessment counteracts the negative wash-back effect of standardized tests. Nonetheless, this type of assessment can be expensive because of the time needed to develop and administer it and to train raters (Brown & Hudson, 1998). Brown (2004, p. 255) identifies some characteristics of performance assessment:

1. Students make a constructed response.2. They engage in higher-order thinking with open-ended tasks.

3. Tasks are meaningful, engaging, and authentic.

4. Tasks call for the integration of language skills.

5. Both processes and products are assessed.

6. The depth of a student’s mastery is emphasized over breadth.

Brown (2004, p. 255) also recommends some procedures for performance assessments to maintain the rigor of traditional tests:

• state the overall goal of the performance,

• specify the objectives (criteria) of the performance in detail,

• prepare students for performance in stepwise progressions,

• use a reliable evaluation form, checklist, or rating sheet,

• treat performances as opportunities for giving feed-back and provide that feedback systematically, and

• if possible, utilize self- and peer-assessments judiciously

Practicality: An Assessment Quality

Although the most important consideration for Bachman and Palmer (1996) regarding the design and development of a language test is usefulness, here I will refer to practicality as the assessment quality that directed a segment of my thesis work. I will mainly consider four authors: Bachman and Palmer (1996), Brown (2004), the CEFR (Council of Europe, 2001), and Arias et al. (2009). I consider it important to mention that Bachman and Palmer’s concept of usefulness is understood as the sum of six qualities: reliability, construct validity, authenticity, interactivity, impact, and practicality, and the basis for implementing these three principles: (a) the overall usefulness of the test; (b) the individual qualities of the test, evaluated in combination with the overall usefulness of the test rather than independently; and (c) the balance among the test qualities determined for each specific testing situation. These principles highlight the fact that for a test to be truly useful, it should have a specific purpose for particular test takers and be in a specific language use or target language use domain. This last concept is defined by Bachman and Palmer as a situation in which the test taker’s oral production abilities are appraised in a real communicative context or through the spontaneous production of language.

It can be said that a test is practical if it is cheap and easy to administer and has a time-efficient scoring procedure. A test is expensive when it takes more time and money than necessary to accomplish its objective (Brown, 2004). In Bachman and Palmer’s (1996) words, a test is practical when the human, material, or time resources required to implement the assessment task are available. The CEFR (Council of Europe, 2001) uses the term feasibility to refer to this testing quality. Brown (2004) defines formal standardized tests as highly reliable and practical instruments because they are cheap for both the test-taker and the test designer in terms of time and money, in contrast with some alternative assessments that seem more expensive. However, the author remarks that the alternative techniques have a more beneficial wash-back effect, are more formative and authentic, and have greater face validity. Arias et al. (2009) define practicality as the relationship between the resources available and the ones that are required to design, administer, and pilot a test in terms of time, space, materials, and human resources. The degree of practicality is determined by the degree of accomplishment of these conditions.

Oral Performance Assessment

Because this study is mainly devoted to oral performance assessment, it is necessary to consider some specific aspects when assessing this skill, for instance, the context in which the assessment takes place, the students’ ages, their cognitive and linguistic levels, the characteristics and appropriateness of the assessment task and, in general, the entire process that assessing the oral skill implies, from its planning to its implementation.

First, it is important to consider that neither native speakers nor foreign learners produce complete sentences, specific vocabulary or a very structured syntax (Brown & Yule as cited in O’Malley & Valdez, 1996). In spite of this, some pause fillers, phrases and simple sentences are used. Nonetheless, it must be remembered that this also depends on certain features such as age and gender (O’Malley & Valdez, 1996). Understanding what a speaker says is part of oral communication. The proposition or idea is its basic unit of meaning (Richards, as cited in O’Malley & Valdez), and it should be retained to comprehend the message. Listening comprehension is defined by Brown and Yule (as cited in O’Malley & Valdez) as the process of arriving at a reasonable interpretation. According to Murphy (as cited in O’Malley & Valdez), listening and speaking should be taught and assessed in an integrated way because they are two interdependent language processes. Regarding oral assessment O’Malley and Valdez (p. 61) affirm that:

Assessment of oral language should focus on a student’s ability to interpret and convey meaning for authentic purposes in interactive contexts. It should include both fluency and accuracy. Cooperative learning activities that present students with opportunities to use oral language to interact with others—whether for social or academic purposes—are optimal for assessing oral language.

The authors recognize the importance of planning for assessment, and these are the steps they suggest: identifying the purpose, planning the assessment, developing the rubric or scoring procedure, setting the standards, involving students in self- and peer-assessment, selecting the assessment task, and keeping record of the information.

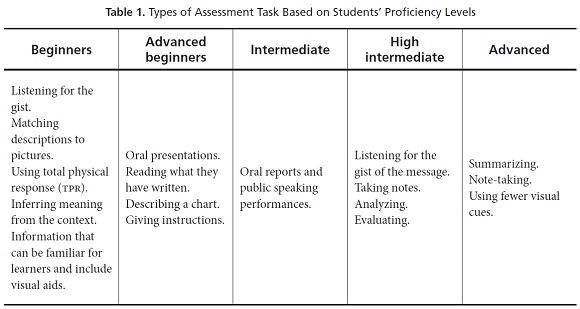

Table 1 summarizes the types of speaking activities and assessment tasks suggested by some authors depending on the learners’ proficiency levels. They recommend the application of different assessment instruments because of the different types of information that can be provided about students’ needs and further instructional goals (The American Council of Teachers of Foreign Languages, Brown & Yule, Murphy, Omaggio Hadley [as cited in O’Malley & Valdez, 1996]).

O’Malley and Valdez (1996) propose the following oral assessment tasks suggested by several authors: oral interviews, picture-cued descriptions of stories, radio broadcasts, video clips, information gaps, story/text retelling, improvisations, role-plays, and simulations, oral reports, and debates. All of these tasks are for different levels of proficiency and target different language functions, as may be seen in Table 1 (Bachman & Palmer, Genishi, González Pino, Hughes, Oscarson, Underhill [as cited in O’Malley & Valdez]).

Oral language assessment in the PIJ targets the students’ ability for communicative and academic purposes. As Cummins (as cited in O’Malley & Valdez, 1996) states, face-to-face interaction and negotiation of meaning with the use of contextual cues, gestures, facial expressions and intonation make up a part of communicative or conversational skills (context embedded), whereas academic language is more context-reduced and more cognitively demanding. Cummins defines communicative language functions as those that express meaning and that are not cognitively demanding. Academic language functions can be used across content areas, for instance, looking for and reporting information, comparing, ordering, classifying, analyzing, inferring, justifying and persuading, solving problems, synthesizing, and evaluating (Chamot & O’Malley, Hamayan & Perlman, O’Malley [as cited in O’Malley & Valdez]).

Assessment Rubrics

As has been shown in the statement of the problem, evaluation in education, although it is necessary, is a thorny issue, and foreign language assessment has not been an exception. Assessment is a time-consuming activity to be accomplished by teachers in addition to all of their other responsibilities, such as planning classes and preparing materials and extracurricular activities. In addition, local research has found difficulties in determining clear assessment criteria among teachers to assess students’ language performance. One of the main repercussions of this has been that students do not reach the minimum knowledge level, which affects the quality of a language program and also indicates a lack of clear criteria among teachers. The rubric appears then as an assessment instrument that can be easy to use and that can establish clear criteria for what to assess.

Mertler (2001) defines a rubric as a rating scale with specific performance criteria defined in advance. Brookhart (as cited in Moskal, 2000) identifies it as a descriptive scoring scheme that can be developed by a teacher to evaluate the process or the product of a student’s work. Taggart and Wood (as cited in Taggart, Phifer, Nixon, & Wood, 1998) explain that rubrics emerged from the need to assess more authentic activities and that they are useful for establishing achievement targets. Finally, Custer (as cited in Taggart et al., 1998, p. 58) states that when rubrics are shared with students, the students “experience more empowerment for their own learning, find learning and assessment less threatening, and become more reflective about their learning.” In my opinion, and based on what some authors have established, rubrics have characteristics that can be connected to some qualities of assessment, such as transparency, reliability and practicality, and without doubt, rubrics positively impact formative assessment and students’ learning and autonomy.

Rubrics are transparent because they explicitly present what the teacher expects. This quality makes the assessment clearer and easy to understand, and it prevents subjectivity when scoring. Evaluation with a rubric can be more objective because the criteria and the weight given to each scale are clearly stated from the beginning. This can prevent an evaluator from giving a higher or lower score to some unspecified aspect. There is a higher probability of obtaining reliable grades when the criteria are clear because different graders can be more objective, so that the score can be validated through different perspectives.

The main reason rubrics are practical is time. According to Stevens and Levi (2005), teachers who are accustomed to working with rubrics can create a new one in less than an hour, perhaps by adapting one they already have or adding changes depending on their specific assessment needs. Creating a new rubric may take more time, but the time invested is worthwhile because the grading time is reduced. Rubrics make grading easier and faster because: (a) What is expected from students is already defined in the rubric, (b) rubrics allow teachers to place the student’s work in a range that gives students an quick idea of what they did well and where they have to improve, (c) the rubric is the format the teacher uses to focus his or her attention on the student’s performance, and this facilitates not only speed in taking additional notes but also the individualized feedback that can be provided through specific comments, and (d) the scoring guide rubrics facilitate grading for the teacher, helping him or her to save time.

Rubrics also promote formative assessment because they offer students feedback about their strengths and weaknesses (Phifer & Nixon as cited in Taggart et al., 1998). Rubrics can also be used as self- and peer-assessment forms. When students are trained to use rubrics for this purpose, they become skillful in identifying and finding solutions for their and other people’s problems. In addition to this, rubrics support individual guidance by helping learners to move from “a dependent level of understanding to a highly independent level of higher order analysis” (Shwery as cited in Taggart et al., 1998, pp. 84-85). This drives students to use rubrics to self-analyze the quality and result of their work. According to Moskal (2000), when students are evaluated with descriptive rubrics, they may become aware of the extent to which their performance complies with the criteria or not. This becomes formative assessment because the description of the criteria lets the students know what they have accomplished and what they have missed, which does not happen, for example, when learners are evaluated with numbers.

It is important to mention that the main reason to determine the type of rubric to use depends on the purpose of the evaluation. There are analytic, holistic, task-specific and general scoring rubrics. The main difference between an analytic and a holistic rubric is that the former allows the evaluation of separate factors and the latter permits an overlap in the evaluation criteria, which means that the criteria can be combined in a descriptive single scale. The rubrics can also be utilized to assess specific tasks or for students’ development of a particular skill, oral for instance (Moskal, 2000).

Findings

Practicality was the second-most recurrent category in the data analysis. This may have been the case because practicality was one of the two objectives of this study, so that the collection of data was somehow focused on it. Eleven out of the 14 teachers who completed the questionnaire provided 28 comments in relation to the ease of assessment with the rubric in terms of planning and defining the topics to assess, assessment of contents and students’ oral skills, presenting the rubric to students, managing the grading system, supporting the grade, and giving feedback. One of the teachers mentioned that at the beginning, it was difficult to rank the students’ performance with the rubric. Seven teachers referred to the ease of assessing with the rubric, including its usefulness in assessing students’ oral performance and in connecting the evaluation to the students’ interests and for the transparency the rubric contributed to the assessment process. Two teachers referred to the usefulness of the rubric in relation to planning class activities and homework based on the criteria established in the rubric.

Another teacher mentioned planning as a characteristic required to implement the rubric. Six of the teachers mentioned that the rubric contributed to evaluation in terms of construct definition and clarity, content and performance assessment, the creation of evaluation standards, the formulation of the assessment task and the creation of new material, and it contributed to connecting the teaching with the assessment objectives. In terms of logistics, six teachers considered that it had been easy to present the rubric to the students, to show the results to parents and pupils, to take notes of the students’ performance, to grade more quickly, and to give feedback to the students. Finally, rubric use was also easy according to five teachers because it made their assessments more transparent and fair because students knew what they were going to be evaluated on and how.

Teacher 3: [It has been easy] guiding the questions, creating evaluative standards, creating new material and situations to carry out the evaluation.

Teacher 14: [The rubric] has facilitated me greatly in terms of supporting the grade.

In contrast with this, there were 17 comments related to its limited practicality. Four teachers considered that the rubric was not very practical. One admitted that it required more work, although the evaluation was more transparent; a second one said the process was complex but worthy; a third one acknowledged that assessing with the grid we had used before was less time-consuming, but that with the rubric we had gained reflection on learning; and one last teacher considered that the process of assessing with the rubric implied a change of paradigms that was not easy because we had been accustomed to traditional methods of assessment but that nonetheless, this could be overcome through practice.

Four other teachers complained about the use of the rubric, which proved complex in terms of time management to prepare it, define the task, present it to students, assess student performance including oral skills and course contents, and, especially, take notes of student performance and give feedback. In relation to logistics, four teachers expressed that it was difficult to be clear with the instructions and the assessment of everything that had to be assessed, such as managing paperwork, understanding the format of the rubric, and working with a rubric prepared by another teacher whose students’ learning processes were unknown by the scorer. Finally, three teachers considered the entire process of assessing with the rubric to be difficult.

According to Stevens and Levi (2005), rubrics save teachers grading time and provide timely and meaningful feedback to students. They state that when used properly, the rubric becomes part of the teaching process. These authors estimate that rubric preparation requires approximately one hour’s time, or less if teachers adapt one that already exists. However, they recognize that at the beginning, creating a rubric can be time-consuming but that the time is worth spending in terms of the grading time it saves and the quality of the feedback students receive. They give an example of how a rubric they used to assess students’ oral performance in a thirty-student class took no more time (one hour to add individual comments) to create and use than did the oral presentations and that in addition to that, the students received the feedback almost immediately. In line with Stevens and Levi, the teachers in this study affirmed that rubrics help teachers to be aware of their teaching methods and provide timely feedback to students. Stevens and Levi (2005) established four ways in which rubrics make grading easier.

1. Rubrics help save time because teachers determine what they want their students to achieve from the very beginning.2. Rubrics allow teachers to save time because if the criteria are well defined in advance, they only have to look within the corresponding rating scale instead of writing extensive notes. The time invested in grading is proportionally inverse to the amount of time devoted to defining the criteria. Rubrics with three to five rating scales or levels permit detailed and quick feedback, so that the scoring can also be accomplished more rapidly.

3. Rubrics make grading easier because the explicit criteria express the highest levels expected from students’ performance.

4. The quantification of the dimensions or criteria established make grade assignments easier.

Conclusions

For teachers, the experience of assessing with a rubric was positive in general; only one of the teachers in the study admitted that its implementation proved difficult. The teachers identified some of the qualities expected from the rubric: usefulness and practicality, fairness, and equitable and democratic principles in its guidance. In addition to this, teachers discovered in the rubric a tool for obtaining evidence of their students’ performance, helping students become aware of their weaknesses and strengths, and making them responsible for their learning needs. The teachers also acknowledged the importance of planning, being creative, and preparing challenging tasks.

One of the main problems defined in this research and also identified by Arias and Maturana (2005) and Muñoz-Marín (2007) in relation to the construct definition targeted the use of the rubric in assessing students’ oral skills. This finding is of tremendous importance for teachers and institutions who must address this problem daily. If teachers are clear about what they have to assess and make it explicit to students, it will impact their teaching practices and also their students’ learning. In addition to this, assessment becomes fairer and more transparent. Although there were teachers who reported gaining clarity in the construct, others reported difficulties in identifying a clear construct, which clearly shows that there exists a real need for training in assessment issues. This training is needed at the initial stage of a curricular innovation such as this on. Subsequently, the training may be given in terms of accompanying the teachers during the rubric implementation process, observing the assessment activities, and giving them feedback. The teachers’ dispositions and willingness to learn a new assessment procedure, their previous beliefs in assessment, and their labor conditions are three key aspects to take into account for administrators who wish to implement a similar curricular innovation in any program.

Keeping track of how assessment with a rubric facilitates evaluation of students is of great importance for everyday teachers who must grade stacks of papers. With the use of a rubric, not only practicality but also meaningfulness in students’ learning are favored, which is necessary in today’s educational institutions and programs. The use of a rubric for students’ learning is an outcome also found by Stevens and Levi (2005) that can be used in similar school contexts in Colombia that are having difficulties in evaluating students. Despite the time spent on defining assessment tasks and designing rubrics at the beginning, I highly recommend that English teachers attempt this experience and that school administrators provide the conditions—time and space—for teachers to meet together and develop their own evaluation standards. As Stevens and Levi (2005) affirm, the time devoted at the beginning will be made up later when teachers begin to save time evaluating, which is not even to mention the impact of the timely feedback that rubrics generate on students’ learning and motivation.

In addition to the benefits that assessment rubrics may represent for teachers, the learning they gain is priceless for their professional growth. In our case, the program gained the recognition of having a great team of teachers, the satisfaction of having fulfilled the trust parents had placed in us, and the feeling of contributing somehow to the accomplishment of what society expects from education. We started a process in which students’ and teachers’ voices were included that must continue, a process that took into consideration previous local studies and the Colombian reality in the field of assessment. I must also thank the teachers of the program who participated in the study group at different times for allowing me to be present in their classes, for listening to me, and for enriching this work with their perspectives and experience. Many thanks must also be given to the group of coordinators who participated in the study group, for their contributions and feedback and for the critical discussions in the weekly meetings. Finally, great gratitude is also owed to the study group and project coordinator who proposed this idea and who has guided my work with dedication.

1The interview and the questionnaire shown in Appendix B were carried out in Spanish.

References

Arias, C., & Maturana, L. (2005). Evaluación en lenguas extranjeras: discursos y prácticas [Assessment in foreign languages: Discourses and practices]. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 10(16), 63-91.

Arias, C., Estrada, L., Areiza, H., & Restrepo, E. (2009). Sistema de evaluación en lenguas extranjeras [Assessment system in foreign languages]. Medellín, CO: Universidad de Antioquia.

Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. S. (1996). Language testing in practice: Designing and developing useful language tests. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Brown, D. H. (2004). Language assessment: Principles and classroom practices. New York, NY: Longman.

Brown, J. & Hudson, T. (1998). The alternatives in language assessment. TESOL Quaterly, 32(4), 653-675.

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. London, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. Retrieved from http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/Source/Framework_EN.pdf

Mertler, C. A. (2001). Designing scoring rubrics for your classroom. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation. Retrieved from http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=7&n=25

Moskal, B. M. (2000). Scoring rubrics: What, when and how? Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation. Retrieved from http://Pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=7&n=3

Muñoz-Marín, J. (2007). Recognizing institutional guidelines and teachers’ practices and beliefs for assessing foreign language reading comprehension performance (Unpublished master’s thesis). Universidad de Caldas, Manizales, Colombia.

O’Malley, J. M., & Valdez-Pierce, L. (1996). Authentic assessment for English language learners: Practical approaches for teachers. White Plains, NY: Addison-Wesley.

Stevens, D. D., & Levi, A. J. (2005). Introduction to rubrics: An assessment tool to save grading time, convey effective feedback, and promote student learning. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Taggart, G., Phifer, S., Nixon, J., & Wood, M. (Eds.). (1998). Rubrics: A handbook for construction and use. Lancaster, PA: Technomic Publishing Company.

About the Author

Diana Pineda has a B.Ed. in foreign language teaching from the Universidad de Antioquia (Colombia), where she currently is an assistant professor. She holds a master’s degree in applied linguistics in teaching English as a foreign language (Universidad de Jaén, Spain) and belongs to the Grupo de Investigación Acción y Evaluación en Lenguas Extranjeras (GIAE).

Acknowledgements

On behalf of the program, I would like to thank the teachers for their commitment, their favorable attitudes toward the change the use of the rubric entailed, their willingness to follow the coordinator’s directives, their courage in reflecting on their assessment practices and their kindness in allowing me to enter their classes.

Appendix A: Questions for the Interview to Teachers1

1. Have you ever used a rubric to assess?

2. How was the experience of assessing with a rubric?

3. How did you feel about assessing your students in the interview with a rubric?

4. What was good? What would you change?

5. What do you think about having assessed the interview with the rubric in relation to the grid used the previous semester?

6. Do you have any additional comment or question?

Appendix B: Questionnaire Used for the Teachers

1. What do you think about the experience of assessing students’ oral performance with a rubric?

2. What has been easy?

3. What has been difficult?

4. Did you have the opportunity to assess in the program with the grid that we used before that only included five general criteria: listening, content, fluency, vocabulary, and pronunciation?

5. How has the experience of assessing with a rubric compared with using the grid that we used before?

6. Use this space if you want to add something else in relation to the use of the rubric to assess students’ oral performance.

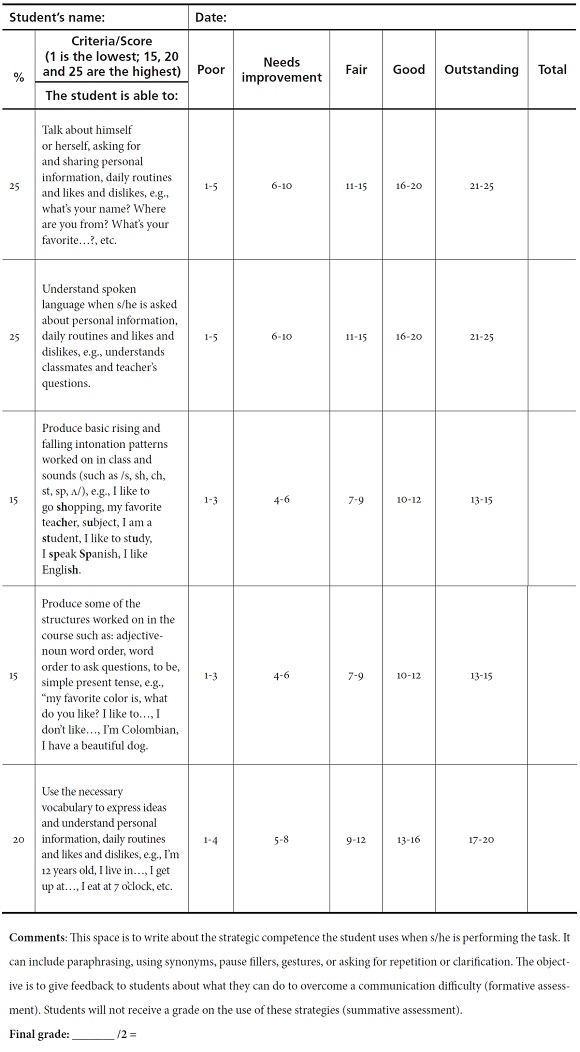

Appendix C: Oral Assessment Task and Rubric

Universidad de Antioquia

Escuela de Idiomas

Centro de Extensión

Programa de Inglés para Jóvenes

Level 1

1st interview: Asking for and giving personal information

Summative assessment

Task: Interview/improvisation for which students have to ask for and give information.

To complete this task successfully you need to:

– Use the simple present tense of the verb to be

– Use the simple present tense of other verbs (live, study, like, etc.)

– Ask and answer questions about personal information: full name, age, phone number, and nationality

– Ask and answer questions about daily routines: chores, bath time, meal times, school duties, free time activities (during the week and on the weekend)

– Ask and answer questions about likes and dislikes: hobbies, sports, music, movies, books, food, colors, actors, singers, and subjects

Instructions: In pairs, you are going to interview each other. Pretend you are on the first English class day and you are getting to know each other. Ask some questions about the information you want to find out about your classmate. Use the simple present of different verbs and the verb to be. Be ready to answer his or her questions, too. You have 10 minutes to do this activity.

Passing score: 3.0

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Sonia Patricia Hernandez-Ocampo. (2022). Colombian Scholars’ Discussion About Language Assessment: A Review of Five Journals. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 24(2), p.231. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v24n2.94468.

2. Laura E. Mendoza. (2023). Improving Learning Through Assessment Rubrics. Advances in Educational Marketing, Administration, and Leadership. , p.1. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-6086-3.ch001.

Dimensions

PlumX

Visitas a la página del resumen del artículo

Descargas

Licencia

Los contenidos de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development son de acceso abierto y los cubre la Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional. Se autoriza copiar, redistribuir el material en cualquier medio o formato, siempre y cuando se conceda el crédito a los autores de los textos y a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development como fuente de primera publicación. No se permite el uso comercial de copia o distribución de contenidos, así como tampoco la adaptación, derivación o transformación alguna de estos sin la autorización previa de los autores y de la Editora de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Los autores conservan la propiedad intelectual de sus manuscritos con la siguiente restricción: el derecho de primera publicación es otorgado a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.