Publicado

Struggling Authorial Identity of Second Language University Academic Writers in Mexico

La lucha de identidad de escritores académicos universitarios de segunda lengua en México

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.48000Palabras clave:

Identity, narrative, second language academic writing, writer struggles (en)identidad, lucha del escritor, narrativa, redacción en segunda lengua (es)

Descargas

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.48000

Struggling Authorial Identity of Second Language University Academic Writers in Mexico*

La lucha de identidad de escritores académicos universitarios de segunda lengua en México

Troy Crawford**

Irasema Mora Pablo***

M. Martha Lengeling****

Universidad de Guanajuato, Guanajuato, Mexico

**crawford@ugto.mx

***imora@ugto.mx

****lengelin@ugto.mx

This article was received on December 22, 2014, and accepted on July 24, 2015.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Crawford, T., Mora Pablo, I., & Lengeling, M. M. (2016). Struggling authorial identity of second language university academic writers in Mexico. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 18(1), 115-127. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.48000.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This paper explores the different factors that appear to affect the on-going construction of second language authorial identity in a professional academic environment in Mexico. Through narrative research methodology from a qualitative paradigm, the everyday struggles of two university professors to maintain their professional status in second language writing are explored. The areas of study for these two are chemistry and penal law. With data the learning processes of entering into a community of second language writers are studied as well as the problems they faced and how they resolved them. Finally, the process of negotiating an authorial identity in a second language seems to be a constant underlying struggle composed of a variety of psychological factors.

Key words: Identity, narrative, second language academic writing, writer struggles.

En este artículo se exploran los diferentes factores que parecen impactar la construcción de identidad de autor permanente en un medio académico profesional en México. Esta búsqueda se da a través de la metodología narrativa desde un enfoque cualitativo de la lucha cotidiana de dos profesores por mantener su status profesional en la redacción en segunda lengua. Sus áreas de trabajo son química y derecho penal. Los datos recopilados permitieron explorar los procesos y problemáticas del ingreso a una comunidad de autores de segunda lengua. Finalmente, se ilustra cómo este proceso de la creación de una identidad de autor es una continua batalla que está compuesto de una gama de factores psicológicos.

Palabras clave: identidad, lucha del escritor, narrativa, redacción en segunda lengua.

Introduction

Self-concept (or self-schema) is the organized structure of cognitions or thoughts that we have about ourselves. It includes the perceptions we have of our social identities and personal qualities, as well as our generalizations about the self based on experience. (Michener, DeLamater, & Myers, 2004, p. 79)

The theme of identity has been researched extensively in the past twenty years and continues to be a significant topic to be researched (Burr, 2003; Charon, 1998; Hall, 2002; Norton, 1997, 2000, 2013). Charon (1998) outlines the complex relationships involved in identity, which he describes as:

an important part of self-concept. It is who the individual thinks he or she is and who is announced to the world in word and action. It arises in interaction, it is reaffirmed in interaction, and it is changed in interaction. It is important to what we do. (p. 5)

Several important points appear in the excerpt above. When referring to “self-concept,” Charon assigns a projection, persona, or wish fulfillment part to identity. Charon also suggests that we reveal our identities via motivated actions in interacting with others. Identity might be figuratively represented by a mirror that reflects who we are, how we see ourselves, how we perceive others, and how other people perceive us.

Norton (2000) also mentions the implication of language and how language command ascertains identity:

It is through language that a person negotiates a sense of self within and across different sites at different points in time, and it is through language that a person gains access to—or is denied access to—powerful social networks that give learners the opportunity to speak. (p. 5)

The use of language, whether it is spoken or written, is how a person can enter into a group. Identity is to a significant extent established, negotiated, and developed through discourse. From this we can see that identity is fluid, and ever-changing depending on what someone wants to achieve. Taking into consideration the aspects of fluidity and language, we will look at the complexities of bilingual writers whose professional writing identity is expressed in another language, not their native language, and in essence whose writing identity straddles two cultures (Barron, 2003; Moreno, 2002). Furthermore, the work of Cintron (1997), Guerra (1998), and Kells, Balester, and Villanueva (2004) propose rhetoric as an element that is deeply connected to identity. This in turn leads directly to Baca (2008), who confirms “rhetoric as a mediating, identity-forming activity” (p. 8).

Therefore, the present research explores the continuous second language writing practices and learning processes of two academic professors in a large public university in Mexico (Universidad de Guanajuato). The research uses narrative inquiry and examines how the two professors confront diverse elements that influence and/or play a strong role in the creation of their authorial identity based upon their opinions and lived experiences. Additionally, the participants’ approaches and strategies used for academic writing in a second language (English and German) is studied and their relationship to sustain and develop the participants’ academic identity and position. At the same time, this research goes beyond the basic issue of first language writing identity. Although the issue of writing identity is a strong element of this research, the internal language and identity struggles to find a voice emerge as a key issue in this research. This issue of bilingual voice and its relationship to writer identity is an area that needs to be researched more in order to understand second language writing and, more specifically, academic writing.

Second Language Writing and Identity

Second language writing has always been at the core of heritage language education, but only recently has it opened up more in the English as a second language (ESL) field (Leeman, Rabin, & Román-Mendoza, 2011). In fact, in recent decades there has been a growing interest in the multifaceted relationship between language and identity. This has made sociocultural concerns more relevant in recent years insofar as they are now being considered as relevant (Block, 2007). Nevertheless, there has been little research on bilingual academic writers in university settings where attention is given to the professional practices of second language writers and, in particular, to writers’ language choices and discourse identities which emerge through individual professional practice (Olinger, 2011; Storch, 2005). There are powerful studies, such as that by Ivanič (1998), that explore in detail the construction of identity in first language users or those by Matsuda (1997, 1999, 2003), who has studied in-depth issues of contrastive rhetoric and the author’s voice using English as the benchmark for evaluation. The issue that seems to be less explored is the voice of the actual user and how it is dealt with on a daily basis in the user’s professional work life. More importantly, the previous work does not locate the second language user as the focus, but the language itself. In fact, if looked at in detail, the only close definition that is given by Ivanič (1998) is the concept of “autobiographical self,” which is the ever evolving complexities of one’s past self and this was not designed for intercultural work because her participants all were native speakers of English. This definition is perhaps too broad for the purpose of our study. As such, it has been reduced in scope to a smaller definition for English as a foreign language (EFL). Our participants deal with multiple literacies and languages to construct their experiences of second language writing. As a result, the definition of identity used in this article attempts to bridge the gap between the native (L1) and the second (L2) languages and relies on the definition that the participants give as a result of using a second language as a means of communication (Yang, 2013).

Therefore, this article provides a space for the two participants to tell their stories, collective or individual, in an ethnographic setting where reflexivity is present to explore the past and present and how they are interrelated. The emphasis of the research is on the participants, rather than their use of language (Olivas, 2009). Here the participants are narrating a personal story which is part of their professional life and focuses on the use of a second language as a tool to maintain their academic status within their respective academic communities.

While there is much evidence of the work in the field of authorial identity construction (Armengol-Castells, 2001; Bell, 2000; Casanave, 2004; Clark & Ivanič, 1997; Clegg, 2008; Connor, 1996; Crawford, Lengeling, Mora Pablo, & Heredia-Ocampo, 2014; Kroll, 1990; Purves, 1988; Russell, 1991; Simmons, 2011; Wodak, 2012), this work has a strong tendency to focus on the English language as a benchmark for evaluation and/or validation. Furthermore, this research tends to reduce or limit the internal influence of the first language and the social patterns that accompany them, making the writing process about English only (Canagarajah, 1993; Crawford, 2007; Holliday, 2005; Kubota, 2002). In fact,

There is indeed a widespread conception that because English is the international language that bridges multiple cultures, learning English enables understanding of the world and cultural diversity, despite its odd fallacy that any English speaker has international understanding. (Kubota, 2002, p. 22)

There seem to have been few attempts to understand the influence of identity inside scholarly engagement from the point of view of the users where priority is given to the processes the users live when writing in a second language (Simmons et al., 2013). Here we are looking at how the second language writers use a second language as a professional tool and its interconnection with the concept of author identity. Specifically, we consider how the two professors deal with the process of creating a working model of writing that works for them and allows them to publish in a second language within their specific disciplines, which are not part of the realm of language studies. In this case, we are looking at two professors that research in the areas of public safety and chemical engineering.

The Study: Participants and Narrative Research

We selected two second language users that are quite successful as researchers in our institution, in the sense that they have demonstrated the ability to publish effectively in a second language. Between them, they have published over 150 articles in international peer reviewed journals within their professional areas of expertise. Both are members of the National Organization of Researchers (Sistema Nacional de Investigadores, SNI) and hold a level two status (three levels in total).

Initially, they were asked to write a narrative frame that described their preparation in second language writing (Barkhuizen, 2014b). The narrative frame served as a tool to create a backdrop for an open-ended interview process. This narrative was an opportunity for the participants to generate their own voice and establish agency at the beginning of the research process. The idea was to let the participants be more participative in the research process. The aforementioned was carried out based upon the theoretical construct of narrative research, which is an open and flexible approach. Barkhuizen (2014a) describes the complexities of narrative research thus:

What stories are, and indeed what narrative research is, however, remains far from agreed upon in Language Teaching Learning [LTL] research. There is no single, all-encompassing definition of narrative (research), probably because the same situation exists in other disciplines from which empirical work in LTL draws its theoretical and methodological assumptions and approaches. (p. 450)

This disagreement shows the problems and also the similarities that are found when defining what constitute narrative research (Stanley & Temple, 2008). We decided to take a position of flexibility in the sense that we allowed our research participants to help shape the narratives by using the open-ended interviews based upon the narrative frames. We also tried to create a thick description by also opening up a discussion of the data with the participants, something which allows for the data to speak more for itself and also shape the result of the study (Denzin & Lincoln, 2000; Holliday, 2002). In order to do so, the two participants analyzed the transcribed data and discussed it with us to see if our written perspectives were a true reflection of their lived experience as second language writers as well as the sociopolitical discourses that made particular meaning-making options available to them (Pavlenko, 2007). This is because our participants are immersed in a writing process that combines their chosen discipline with a possibly forced second language writing option which is part of their professional identity. Therefore, narrative is an ideal approach to examine the participants’ professional practice and their second language writing experiences (Pavlenko, 2007). By constructing narratives, participants were engaged in narrative “knowledging” (Barkhuizen, 2011) by making meaning of certain important issues and experiences in their professional practice, and thereby giving these issues and experiences coherence so that we and the participants were better able to understand and interpret them. This was all done in order to construct the participants’ stories and give light to their identity. This provides the reader with a multifaceted view of bilingual writing identity which was constructed through the lived experience of the participants in the research process. The two participants were given the option to decide on what language they would like to use in this research; we also gave them pseudonyms to protect their identity.

Findings

The Initial Stages of Writing in a Second Language: The Influence of Another Person

For both participants, the process of beginning to write in a second language started due to their professional lives. Neither one was interested in writing in a second language; it was forced upon them. First when they studied for their respective PhD degrees and then later as a requirement within the institution where they work. One completed his doctoral studies in Penal Law with a specialization in Criminology from a German university and his area of expertise is public security. The other earned his doctorate in Chemical Engineering in Mexico. In the area of chemistry, the participant had to learn English. On the one hand, they needed to enter a new academic world and write in the language which is highly regarded in their profession. For one of the participants it was English and for the other participant it was German. However, both of them had the influence of a tutor or supervisor who helped them at the beginning and corrected their work in their graduate studies. In the next excerpt, a participant describes how his supervisor advised him how to approach academic writing:

My supervisor used to tell us: “write your article in Spanish,” and he would translate it into English. Well, he speaks English perfectly, but he used to say: “do it and I will do the translation”...but then, I think he didn’t do the translation. He wanted us to present the ideas and he used that document as a basis to rephrase it, right? Probably, back in that time, I understood “Oh, I will write it in Spanish and then I will try to translate it”, but after a while I realized that it was not right because the article didn’t fulfill my expectations. I understood that what I had to do was to write in English from the very beginning. (Gerardo)1

For the other participant, who writes in German, he had a similar situation:

One day my supervisor told me “You are going to learn German. I just got you a scholarship”, and honestly, I said “Oh, my God!” So, at nights, I used to go to the Goethe-Institut (Cultural Institute of the German Federal Republic) to learn German. (Jesus)

When he started to write in German, his tutor had an important role as a reviewer and guide of his work:

My article was reviewed by Klaus, my supervisor. So, I wrote it and he said “this is bad...pzazpzaz” and he gave it back to me “correct it,” and I corrected it. (Jesus)

Being a “newcomer” to the second language writing process is far more complex than just knowing the language; the participants’ areas of expertise also played an important role. Most of the material they read and had access to was in the second language. This is where this unique process of having to deal with multiple literacies begins to manifest itself in the writing process. Jesus mentions this in the following:

In my area of law, the biggest and strongest part is in German. The gringos have a very big conceptual issue when writing, even the British, well, the British less than the gringos. So, I don’t read [in English] in my area. I read a little more in British English because the British has fewer conceptual issues [sic].

As seen above, there is a process that begins where the participant classifies academic writing in his area, as well as ideological thinking, that is, the conception the participant has about the three countries: The United States, Britain, and Germany. This implies a sociological process that influences the written language development for this person. He clearly states he has problems with how Americans write. Furthermore, this same participant acknowledges his closeness to German and lets his students know that his area of law is written in German, so that they should perhaps start reading in German. This passes on one of the underlying conflicts to another new group: his students. Now his students are forced to start dealing with multiple literacies in their profession. In the excerpt below, we can appreciate how this participant is connected to German emotionally:

So, emotionally I am closer to German. I acknowledge that in my area. I always tell students that penal law is written in German. It starts in German, so...I try to read the originals. Fortunately, there are many translations, but they are translations. (Jesus)

This displays an emotional tie to the language and its relationship to penal law. It also shows how he uses German in order to understand specifics of his area. This use of German in his content area also has an effect upon his teaching and writing. This in turn implies the possibility that the use of German is occurring at a subconscious level concerning writing and possibly his thinking. This type of dual literacy does not occur in first language writing. It is this issue of two languages or more at play in the process of creating a written voice that becomes more complex for the second language author. This form of complexity does not exist for the monolingual writer; it can only be appreciated by a bilingual or multi-lingual writer. This emotional connection becomes a powerful force within the writing process and needs to be dealt with by the second language user. As he clearly manifests that a translation of an academic work is considered weaker, he wants his students to read the originals. This starts to raise a deeper question. Does he consider his own writing as a translation or a weaker version of knowledge?

The Process of Writing in a Second Language

Entering into a new academic discourse community is a complex task. It involves struggles, conflicts, and differences of writing conventions between L1 and L2. This in turn has emotional impacts on the writer. Having a plan or strategies concerning how to approach this new writing process is needed as well as how to transform the participants’ new writing identities in their L1 identities and negotiate these identities into L2. These two participants seemed to overlap their two writing communities (L1 and L2) simultaneously. At the beginning, they relied on their L1 to start writing in their L2:

At the beginning, the problem I had was that I tried to be very literal. I don’t know, I thought about the idea in Spanish and then I tried to translate it and many times you realize that it doesn’t necessarily work. (Gerardo)

Jesus’ first technique to approach writing in German was to rely on his L1 and directly translate his writing. But with experience, he became aware of the differences between these two languages and the problems of this abovementioned translation technique.

Before starting to write, the same participant mentions how important it was to have a plan and to know exactly what he wanted to express:

For me it is like writing a diary. I mean, you write the diary at the end of the day when you know what you are going to write, which step to follow. If I don’t know how this is going to start and how it is going to end...I need to know exactly where I am going. The structure is always, always, always in Spanish, the big structure, and then I tried to think about it in another language. In German sometimes it is difficult, but I tried and it gets reduced, because German is very concise. (Jesus)

According to this participant, the structure he followed was Spanish-based and then he tried to follow the same in German, but it is not rhetorically possible to accomplish. This in turn could be linked to the idea that the use of translation is not an appropriate step in the writing process.

As these participants get more and more involved in their second language writing communities, they find their own resources and strategies to approach their writing tasks. For example, Gerardo mentions how reading in the L2 has helped him to approach L2 writing:

Maybe I don’t do it as spontaneous as I would like, sitting and using the keyboard in the computer. My procedure is more like “I’m going to read some articles to get familiar with the topic, how it is structured in English and then I will start to write” and then if I get stuck, I will read again to see how they have a paragraph, to get some ideas and then I continue, and finally I review and then I read it again. But sometimes you never believe you are correct.

This participant is always questioning what he writes in L2, but at the same time, he relies on what he has written and published previously to follow the organization of a text. The next excerpt illustrates this:

Before I start writing, I read one of the articles I have already published, to get familiar with the terminology or the form, how to organize the ideas. I try to read some articles related to the topic. (Gerardo)

To become familiar with the topic he is writing about, it becomes essential for this participant to feel more confident in approaching writing in L2. These strategies give him security and confidence to write in another language. The same participant elaborates on this process:

Well, I have many texts and I know where they are. I know, for example, where the references are and it is faster, I pull all the references I’m going to use. All the texts that I read, I mark them, so I know exactly where they are, or more less, when I write. I don’t have a big space, but I put all the books on the desk, with little papers. (Gerardo)

Both participants acknowledge the use of previously written work in order to produce a new one. For publication purposes, they seem to rely on their own past work before embarking on the task of writing a new article. Perhaps using these successful pieces of work helps the participants understand what they have to do for the next articles they are writing. Reading in L2 also plays an important role in this process and can be seen as a way for them to adapt their writing to L2 academic standards. In essence, what can be seen is a cyclic process of permanent construction of a text, where each new text is built on the previous one. It is almost as if the second language writing process is one of continuous development.

Time is an important element in the progression. One participant mentions how he plans the way he writes in the L2:

When I have time, I dedicate four or five hours, I mean, from 11:00 p.m. to 5 or 6:00 a.m., preferably on vacations. Unless I have many ideas, I write them all, half an hour and ready. I put them in order and then I leave them in standby until I have the time to structure them correctly. (Gerardo)

When the manuscript is submitted to an academic journal and they receive the reviewers’ comments, both participants experience anxiety. The anxiety is not related to their professional knowledge, but it is connected to how these participants may perceive what they have written in another language. The focus seems to be on how they are interpreted as writers and the anxiety is related exclusively to issues of second language conventions. This type of anxiety is much less likely to occur for a native writer:

The corrections the supervisor made for us were...always the same. Every time we were doing better and better, but above all, the way we structured our ideas. Probably in Spanish we tend to write long sentences and in English we need to rephrase them in short sentences, even the most basic things. At the beginning it was “please, have a native speaker review your document because you have many mistakes” but lately, they don’t make those comments. It is more like “careful with the typos.” (Gerardo)

The process of writing in an L2 can be stressful, but with time and more practice, the participants can see how they develop their use of academic language in another language and they seem to be entering into a new discourse community. This entering is a type of socialization that requires public acceptance in an academic community. The following excerpt shows how Gerardo goes about this process:

Maybe there was a moment in which I think you become familiar with the reading, with all the information that we have in our area, all the information we have to review is in English. [When I write now] I think it looks more like the ones seen in journals.

The key is what it looks like in an academic journal. The goal is public acceptance of an academic activity that requires outside validation. This implies that producing a replicate of an existing text is a positive goal in the academic social context. A critical framework is required because it becomes easy to see that a process cannot be separated from a product, and language cannot be divorced from culture. This is due to the consideration that a writer may bring different types of professional knowledge based on lived experiences to the writing activity. As a result, internal tensions may arrive where the focus deals with conforming to linguistic patterns, rather than producing knowledge. This is where the user is forced to shift from L1 to L2.

Language Shift: Goodbye L1 and Welcome L2

From a sociolinguistic point of view, the participants’ language shift has been gradual and one participant has shown through the narrative to be more dominant in the second language than in his native language. Becoming a user of the L2 in the academic world might imply the language shift which refers to one language becoming more dominant than the other. In the case of these two participants, Spanish was their native language and English and German were the second languages. Gradually, over time, the language of the wider academic community (English and German) displaces the minority language (Spanish), as in the case of the following participant:

I think that one is forced to begin to be bilingual, in the sense of writing. I think the identity...they force you to...if you want to publish in the important magazines, well, they are in English, and so they force you to do this part of your job in English. So, I think they could even tell you, “forget your Spanish, your native language.” For example, when you go to conferences, you have to write the presentation, the slides of power point presentations in English, the proceedings in English, so technically they force you to lose your identity because of the context where you work. (Gerardo)

Even when he continues to use both languages in different professional contexts, English satisfies his professional needs and Spanish is reserved exclusively for his private life, as he points out:

I think there have been cases that, due to the demands of the profession of chemical engineering, you need to either move in English or not, or you drown in the ocean. But there have been people that they have done it and the evidence is that, for example, they are not in the national researchers’ system, they do not have PROMEP [Programa de Mejoramiento del Profesorado/Program of Professional Development] profile, they do not have collaboration with other colleagues, or they find it difficult to send students on exchange programs to continue with their postgraduate studies. It is almost like...an excess in Spanish is something...like Spanish is exclusively for your private life. (Gerardo)

With being a bilingual person and a competent user of English, the professional doors seem to open easier in his field, not only for publishing but also for establishing contacts in other countries, using English as a lingua franca. This needs to be seen as an underlying conflict because the user is required to use a second language to be professionally accepted.

And at work, English is the most important because they indirectly ask you to use it. If you want to have an important contact in a different country, it doesn’t matter in which country. For example I have a colleague in Denmark but he is Chinese, so we have to speak in English. (Gerardo)

The influence of the L2 in his personal and professional encounters becomes more evident in the following extract. English has gradually infiltrated his L1 writing and this seems to interfere at times. Now the user is also dealing with stress when writing in his native language:

Sometimes, when they ask me to write an article in Spanish, it is more difficult than doing it in English, because I am more used to the structure in English, and in Spanish...it should be simpler but it is not. (Gerardo)

The other participant comments on how he recognizes that he now writes in Spanish as he would write in German. This is interesting because the L2 is moving in and affecting his L1 at a deeper rhetorical level. Jesus’s excerpt shows the internal conflict that can be felt by a bilingual writer as he works out how to separate the languages in his professional writing:

I’m less redundant in German than in Spanish and in English than in Spanish. I think I am more precise due to the language, it forces you to be more...for example, Germans can say “I’m going to explain three things to you” and it means three things, one, two, three. And in Spanish they say “I’m going to tell you some things.” It is not like one, two, three, then when you write it is four, five. So, in Spanish, I do the same. I’m going to express three ideas in three points. The paragraph that is more difficult for me is the first one, because in the first one you need to explain the presentation of the problem, my theoretical framework, and my conclusions, and after that it is simpler. It is the same structure, so it is always the same.

Writing professionally in another language for publication (and specifically in English) has been regarded as a sign of success in the academic world and in particular in the institution where these participants work. However, the dominance this language has on their lives carries over to how they see their L1. They now seem to find it more difficult to write in L1. They initially relied on their L1 to approach L2 writing and now they seem to rely more on L2 writing to approach L1. Here we can observe the conflict of trying to establish a second language writing identity. A shifting identity is present in the sense that these professionals have to deal with two rhetorical patterns, two discourse communities, and two different writing standards. This creates a space for underlying conflict at psychological and social levels that are manifested through language use. This process of moving between languages is present because of the fact that the users are bilingual. The traditional writing processes rarely discuss the aspect of working inside the frame of more than one language.

Conclusion

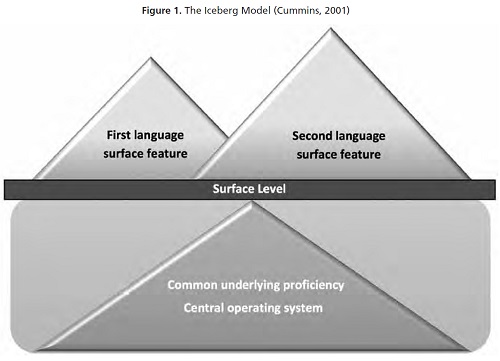

It can be clearly seen that there are multiple conflicts or struggles that occur in the second language writing process for these participants. It is also clear that the issue of dealing with two languages is a factor in relation to the participants’ authorial identity. How this is explained or classified leaves some room for debate. We, as bilingual researchers, have selected the “iceberg model” (see Figure 1) within the conceptual frame as outlined by Cummins (1992, 2001) as a possible way to illustrate what may be happening underneath the surface of the participants in their unique approaches to dealing with second language writing. The basic reasoning is that the participants have made a continuous reference to different types of struggles focused on the use of second language writing. Never was there a reference to a struggle in connection to their professional knowledge as university professors or researchers. This implies that it is possible for an underlying linguistic conflict to be present that is not visible in the participants’ professional writing, but only in their personal narrative of language use.

The users of a second language are engaged in a surface fluency use of the language in the production of their texts for their professional activities, but at the same time they are also engaged in developing an underlying operating system to deal with the use of the second language. These underlying operating systems seem to be comprised of social and psychological issues that tend to fall outside the traditional framework of authorial identity; even though it is evident they influence it. Past focus has been on the surface results rather than looking closer at the underlying issues. Here, what we have done is to draw attention to the hidden battle and struggles that academic writers have in writing in another language. Most of the issues brought forward are centered on personal and social issues that are indirectly related to writing in a second language, but definitely influence it. The result is that we do need to carry out more research on the common underlying proficiency and its impact on not only the individual, but the broader social issues of second language writing in terms of writer identity. In particular as regards how it is interconnected to the construction of professional knowledge and the norms that make this knowledge acceptable for publication.

We have also struggled to try to define exactly what identity is and how it is dealt with in second language writing, even though we have not been able to offer a clear definition of what it is. We have, through this study, come to have a better understanding of how second language users find a place for second language writing in their professional lives. As researchers in the field of applied linguistics, we have tried to let our co-workers from the university take control of their agency in the narrative and present it from their perspective of actual successful users of the language in specific academic disciplines.

These participants have shown how a second language has slowly moved into aspects of their professional life, impacting the participants at different levels. The participants have had to return to their L1 for guidance rather than the L2; this implies a serious shortcoming of the L2 classroom in terms of policy and practice in the teaching of second language writing. On the other hand, it was also explicitly stated that the L2 now, in turn, influences the L1 writing. This is what illustrates this permanent underlying struggle that a second language writer lives with. This struggle, in particular, should be addressed in the EFL/ESL classrooms where language production for evaluation purposes appears to displace production for professional or contextual purposes. These participants have worked over a long time to find a process where in the end the goal of writing is being able to use language for specific purposes in their professional lives. They both have found success, but they found it outside of the social space of second language learning. This should be a cause for concern among EFL/ESL writing professionals e.g., the way in which we have treated aspects of identity in the past and the value that has been placed on the first language knowledge that is brought into the discussion by the user. It would seem to be sensible to re-address much of the past research on second language writing and try to place a stronger focus on the user, rather than on language itself to better understand second language writing. Writing is a socially constructed activity that involves far more than just a simple linear process of production of a different set of linguistic rules. It is a deeper complex struggle that requires more research in particular of bilingual writers.

*This research was funded by the Department of Research and Graduate Studies of the Universidad de Guanajuato (DAIP).

1The data samples were translated from Spanish to English for publication purposes.

References

Armengol-Castells, L. (2001). Text-generating strategies of three multilingual writers: A protocol-based study. Language Awareness, 10(2-3), 91-106.

Baca, D. (2008). Mestiz@ scripts, digital migrations, and the territories of writing. New York, NY: Palgrave.

Barkhuizen, G. (2011). Narrative knowledging in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 45(3), 391-414.

Barkhuizen, G. (2014a). Narrative research in language teaching and learning. Language Teaching, 47(4), 450-466.

Barkhuizen, G. (2014b). Revisiting narrative frames: An instrument for investigating language teaching and learning. System, 47, 12-27.

Barron, N. G. (2003). Dear saints, dear Stella: Letters examining the messy lines of expectations, stereotypes, and identity in higher education. College Composition and Communication, 55(1), 11-37.

Bell, J. (2000). Framing and text interpretation across languages and cultures: A case study. Language Awareness, 9(1), 1-16.

Block, D. (2007). The rise of identity in SLA research, post Firth and Wagner (1997). The Modern Language Journal, 91(Suppl. 1), 863-876.

Burr, V. (2003). Social constructionism. Hove, UK: Routledge.

Canagarajah, A. S. (1993). Critical ethnography of a Sri Lankan classroom: Ambiguities in student opposition to reproduction through ESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 27(4), 601-626.

Casanave, C. (2004). Controversies in second language writing: Dilemmas and decisions in research and instruction. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Charon, J. M. (1998). Symbolic interactionism. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Cintron, R. (1997). Angels’ town: Chero ways, gang life, and rhetorics of the everyday. Boston, MA: Beacon.

Clark, R., & Ivanič, R. (1997). The politics of writing. London, UK: Routledge.

Clegg, S. (2008). Academic identities under threat? British Educational Research Journal, 34(3), 329-345.

Connor, U. (1996). Contrastive rhetoric: Cross-cultural aspects of second language writing. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Crawford, T. (2007). Some historical and academic considerations for the teaching of second language writing in English in Mexico. MEXTESOL Journal, 31(1), 75-90.

Crawford, T., Lengeling, M., Mora Pablo, I., & Heredia-Ocampo, R. (2014). Hybrid identity in academic writing: “Are there two of me?” PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 16(2), 87-100.

Cummins, J. (1992). Language proficiency, bilingualism, and academic achievement. In P. A. Richard-Amato & M. A. Snow (Eds.), Multicultural classroom: Readings for content-area teachers (pp. 16-26). White Plains, NY: Longman Publishing.

Cummins, J. (2001). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: California Association for Bilingual Education.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2000). Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Guerra, J. C. (1998). Close to home: Oral and literate practices in a transnational Mexicano community. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Hall, J. K. (2002). Teaching and researching language and culture. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Holliday, A. (2002). Doing and writing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Holliday, A. (2005). The struggle to teach English as an international language. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ivanič, R. (1998). Writing and identity: The discoursal construction of identity in academic writing (Vol. 5). Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

Kells, M. H., Balester, V., & Villanueva, V. (Eds.). (2004). Latino/a discourses: On language, identity and literacy education. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Kroll, B. (Ed.). (1990). Second language writing: Research insights for the classroom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kubota, R. (2002). The impact of globalization on language teaching in Japan in English language teaching. In D. Block & D. Cameron (Eds.), Globalization and language teaching (pp. 13-29). New York, NY: Routledge.

Leeman, J., Rabin, L., & Román-Mendoza, E. (2011). Identity and activism in heritage language education. The Modern Language Journal, 95(4), 481-495.

Matsuda, P. K. (1997). Contrastive rhetoric in context: A dynamic model of L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 6(1), 45-60.

Matsuda, P. K. (1999). Composition studies and ESL writing: A disciplinary division of labor. College Composition and Communication, 50(4), 699-721.

Matsuda, P. K. (2003). Basic writing and second language writers: Toward an inclusive definition. Journal of Basic Writing, 22(2), 67-89.

Michener, A., DeLamater, J., & Myers, D. (2004). Social psychology (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thompson Learning.

Moreno, R. (2002). The politics of location: Text as opposition. College Composition and Communication, 54(2), 222-242.

Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity, and the ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 409-429.

Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning. Essex, UK: Pearson.

Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning (2nd ed.). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Olinger, A. R. (2011). Constructing identities through “discourse”: Stance and interaction in collaborative college writing. Linguistics and Education, 22(3), 273-286.

Olivas, M. R. (2009). Negotiating identity while scaling the walls of the ivory tower: Too brown to be white and too white to be brown. International Review of Qualitative Research, 2(3), 385-406.

Pavlenko, A. (2007). Autobiographic narratives as data in applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics, 28(2), 163-188.

Purves, A. C. (Ed.). (1988). Writing across languages and cultures: Issues in contrastive rhetoric. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Russell, D. R. (1991). Writing in academic disciplines, 1870-1990: A curricular history. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois UP.

Simmons, N. (2011). Caught with their constructs down? Teaching development in the pre-tenure years. International Journal for Academic Development, 16(3), 229-241.

Simmons, N., Abrahamson, E., Deshler, J., Kensington-Miller, B., Manarin, K., Morón-García, S., Oliver, C., & Renc-Roe, J. (2013). Conflicts and configurations in a liminal space: SoTL scholars’ identity development. Teaching & Learning Inquiry: The ISSOTL Journal, 1(2), 9-21.

Stanley, L., & Temple, B. (2008). Narrative methodologies: Subjects, silences, re-readings and analyses. Qualitative Research, 8(3), 275-281.

Storch, N. (2005). Collaborative writing: Product, process, and students’ reflections. Journal of Second Language Writing, 14(3), 153-173.

Wodak, R. (2012). Language, power, and identity. Language Teaching, 45(2), 215-233.

Yang, S. (2013). Autobiographical writing and identity in EFL education. London, UK: Routledge.

About the Authors

Troy Crawford holds an MS in Labor Psychology from Universidad de Guanajuato, an MA in TESOL from the University of London, and a PhD in Language Studies from the University of Kent. He is a member of the Mexican National Research System focusing his research on identity in second language writing.

Irasema Mora Pablo is a professor at Universidad de Guanajuato, Mexico. She holds a PhD in Applied Linguistics from the University of Kent, UK. She has conducted research on bilingualism, Latinos’ studies, identity formation, and native and non-native teachers and has published chapters and articles in Mexico, the United States, and Colombia.

M. Martha Lengeling works at Universidad de Guanajuato and holds an MA in TESOL (West Virginia University) and a PhD in language studies (University of Kent, UK). She is the Editor of the MEXTESOL Journal and currently is a member of the Mexican National Research System. Her areas of research are teacher training and teacher identity formation.

Referencias

Armengol-Castells, L. (2001). Text-generating strategies of three multilingual writers: A protocol-based study. Language Awareness, 10(2-3), 91-106.

Baca, D. (2008). Mestiz@ scripts, digital migrations, and the territories of writing. New York, NY: Palgrave.

Barkhuizen, G. (2011). Narrative knowledging in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 45(3), 391-414.

Barkhuizen, G. (2014a). Narrative research in language teaching and learning. Language Teaching, 47(4), 450-466.

Barkhuizen, G. (2014b). Revisiting narrative frames: An instrument for investigating language teaching and learning. System, 47, 12-27.

Barron, N. G. (2003). Dear saints, dear Stella: Letters examining the messy lines of expectations, stereotypes, and identity in higher education. College Composition and Communication, 55(1), 11-37.

Bell, J. (2000). Framing and text interpretation across languages and cultures: A case study. Language Awareness, 9(1), 1-16.

Block, D. (2007). The rise of identity in SLA research, post Firth and Wagner (1997). The Modern Language Journal, 91(Suppl. 1), 863-876.

Burr, V. (2003). Social constructionism. Hove, UK: Routledge.

Canagarajah, A. S. (1993). Critical ethnography of a Sri Lankan classroom: Ambiguities in student opposition to reproduction through ESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 27(4), 601-626.

Casanave, C. (2004). Controversies in second language writing: Dilemmas and decisions in research and instruction. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Charon, J. M. (1998). Symbolic interactionism. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Cintron, R. (1997). Angels’ town: Chero ways, gang life, and rhetorics of the everyday. Boston, MA: Beacon.

Clark, R., & Ivanič, R. (1997). The politics of writing. London, UK: Routledge.

Clegg, S. (2008). Academic identities under threat? British Educational Research Journal, 34(3), 329-345.

Connor, U. (1996). Contrastive rhetoric: Cross-cultural aspects of second language writing. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Crawford, T. (2007). Some historical and academic considerations for the teaching of second language writing in English in Mexico. MEXTESOL Journal, 31(1), 75-90.

Crawford, T., Lengeling, M., Mora Pablo, I., & Heredia-Ocampo, R. (2014). Hybrid identity in academic writing: “Are there two of me?” PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 16(2), 87-100.

Cummins, J. (1992). Language proficiency, bilingualism, and academic achievement. In P. A. Richard-Amato & M. A. Snow (Eds.), Multicultural classroom: Readings for content-area teachers (pp. 16-26). White Plains, NY: Longman Publishing.

Cummins, J. (2001). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: California Association for Bilingual Education.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2000). Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Guerra, J. C. (1998). Close to home: Oral and literate practices in a transnational Mexicano community. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Hall, J. K. (2002). Teaching and researching language and culture. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Holliday, A. (2002). Doing and writing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Holliday, A. (2005). The struggle to teach English as an international language. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ivanič, R. (1998). Writing and identity: The discoursal construction of identity in academic writing (Vol. 5). Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

Kells, M. H., Balester, V., & Villanueva, V. (Eds.). (2004). Latino/a discourses: On language, identity and literacy education. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Kroll, B. (Ed.). (1990). Second language writing: Research insights for the classroom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kubota, R. (2002). The impact of globalization on language teaching in Japan in English language teaching. In D. Block & D. Cameron (Eds.), Globalization and language teaching (pp. 13-29). New York, NY: Routledge.

Leeman, J., Rabin, L., & Román-Mendoza, E. (2011). Identity and activism in heritage language education. The Modern Language Journal, 95(4), 481-495.

Matsuda, P. K. (1997). Contrastive rhetoric in context: A dynamic model of L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 6(1), 45-60.

Matsuda, P. K. (1999). Composition studies and ESL writing: A disciplinary division of labor. College Composition and Communication, 50(4), 699-721.

Matsuda, P. K. (2003). Basic writing and second language writers: Toward an inclusive definition. Journal of Basic Writing, 22(2), 67-89.

Michener, A., DeLamater, J., & Myers, D. (2004). Social psychology (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thompson Learning.

Moreno, R. (2002). The politics of location: Text as opposition. College Composition and Communication, 54(2), 222-242.

Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity, and the ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 409-429.

Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning. Essex, UK: Pearson.

Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning (2nd ed.). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Olinger, A. R. (2011). Constructing identities through “discourse”: Stance and interaction in collaborative college writing. Linguistics and Education, 22(3), 273-286.

Olivas, M. R. (2009). Negotiating identity while scaling the walls of the ivory tower: Too brown to be white and too white to be brown. International Review of Qualitative Research, 2(3), 385-406.

Pavlenko, A. (2007). Autobiographic narratives as data in applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics, 28(2), 163-188.

Purves, A. C. (Ed.). (1988). Writing across languages and cultures: Issues in contrastive rhetoric. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Russell, D. R. (1991). Writing in academic disciplines, 1870-1990: A curricular history. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois UP.

Simmons, N. (2011). Caught with their constructs down? Teaching development in the pre-tenure years. International Journal for Academic Development, 16(3), 229-241.

Simmons, N., Abrahamson, E., Deshler, J., Kensington-Miller, B., Manarin, K., Morón-García, S., Oliver, C., & Renc-Roe, J. (2013). Conflicts and configurations in a liminal space: SoTL scholars’ identity development. Teaching & Learning Inquiry: The ISSOTL Journal, 1(2), 9-21.

Stanley, L., & Temple, B. (2008). Narrative methodologies: Subjects, silences, re-readings and analyses. Qualitative Research, 8(3), 275-281.

Storch, N. (2005). Collaborative writing: Product, process, and students’ reflections. Journal of Second Language Writing, 14(3), 153-173.

Wodak, R. (2012). Language, power, and identity. Language Teaching, 45(2), 215-233.

Yang, S. (2013). Autobiographical writing and identity in EFL education. London, UK: Routledge.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Frank Giraldo. (2019). An English for Research Publication Purposes Course: Gains, Challenges, and Perceptions. GiST Education and Learning Research Journal, 18, p.198. https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.454.

2. Jingjing Hu, Sihang Yuan, Xuesong (Andy) Gao. (2022). Students’ Writer Identities and Writing Practice in Tertiary English-Medium Instruction in China. Sustainability, 14(22), p.14890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214890.

3. Shahla Asadolahi, Musa Nushi. (2021). An autobiographical narrative inquiry of academic identity construction of PhD candidates through L2 authorship development. Heliyon, 7(2), p.e06293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06293.

Dimensions

PlumX

Visitas a la página del resumen del artículo

Descargas

Licencia

Los contenidos de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development son de acceso abierto y los cubre la Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional. Se autoriza copiar, redistribuir el material en cualquier medio o formato, siempre y cuando se conceda el crédito a los autores de los textos y a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development como fuente de primera publicación. No se permite el uso comercial de copia o distribución de contenidos, así como tampoco la adaptación, derivación o transformación alguna de estos sin la autorización previa de los autores y de la Editora de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Los autores conservan la propiedad intelectual de sus manuscritos con la siguiente restricción: el derecho de primera publicación es otorgado a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.