EFL Teaching Methodological Practices in Cali

Keywords:

English as a foreign language (EFL), teaching methods, teacher profile, teaching practices (en)EFL Teaching

Methodological Practices in Cali

Prácticas metodológicas en la enseñanza de inglés como lengua extranjera en la ciudad de Cali

Orlando Chaves*

Fanny Hernández**

Universidad del Valle, Colombia

*orlando.chavez@correounivalle.edu.co

** fanny.hernandez@correounivalle.edu.co

This article was received on

April 30, 2012, and accepted on July 3, 2012.

In this article we aim at

showing partial results of a study about the profiles of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers in both public and

private primary and secondary strata 1-4 schools in Cali, Colombia.

Teachers’ methodological approaches and practices are described and

analyzed from a sample of 220 teachers. Information was gathered from surveys,

interviews and institutional documents. The quantitative information was

processed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences and Excel while

the qualitative information (from a survey and focal interviews) was analyzed

hermeneutically. An analysis grid was used for the examination of institutional

documents (area planning, syllabi, and didactic materials). Teachers’

methodology (approaches/methods), lessons, activities, objectives, curricula,

syllabi and evaluation are analyzed in the light of literature in the field.

Finally, we discuss the implications of methodological approaches.

Key words: English as a foreign language (EFL), teaching methods, teacher profile, teaching practices.

En este artículo se presentan los resultados

parciales de una investigación sobre los perfiles de los profesores de

inglés como lengua extranjera que enseñan en colegios de

educación básica primaria y secundaria, públicos y

privados, de estratos 1 a 4 en Cali, Colombia. Se describen y analizan sus

enfoques y prácticas metodológicas a partir de una muestra de 220

docentes. Se obtuvo información cualitativa y cuantitativa por medio de

encuestas, entrevistas y documentos institucionales. La in-formación

cuantitativa se procesó con el software Statistical

Package for Social Sciences y Excel, mientras que la información

cualitativa se analizó hermenéuticamente. Se usó una

rejilla de análisis para el examen de los documentos institucionales

(planes de área, programas, y materiales didácticos). La

metodología (enfoques/métodos), clases, actividades, objetivos,

currículo, programas y evaluación se analizan a partir de la

literatura especializada en el campo. Finalmente, se discuten las implicaciones

de estos enfoques metodológicos.

Palabras clave: inglés como lengua extranjera, métodos de enseñanza, perfil docente, prácticas de enseñanza.

Introduction

It

is a fact that English has evolved as an inter-national language with great

importance in economic, political, and cultural contexts. In the educational

field, this importance is reflected in English as a Foreign Language (EFL)

language policies seeking global integration. In Colombia, the National

Bilingual Program (NBP) represents the official policy which aims at

enabling all citizens to communicate in English with internationally comparable

standards (Ministerio de Educación

Nacional [MEN], 2006a, p. 3). The document Estándares básicos

de competencias en lenguas extranjeras: inglés (MEN, 2006) is the most

noticeable component of this program. It states that, by 2019, all students and

teachers will reach predeter-mined levels of English,

according to the Council of Europe’s Common European Framework of

Reference [CEFR] (Council of Europe, 2001) scale1: C1 for teachers of foreign

languages; B2 for professionals in other areas; B2 for English teachers at the

elementary level, B1 for students who finish the secondary level, and A2 for

teachers of other areas at the elementary level.

However, the official announcement of this bilingualism policy is not

enough to guarantee its enactment. More knowledge about the context in which

the policy is to be applied is still required. In regard to this need, a group

of researchers from Universidad del Valle and

Universidad San Buenaventura carried out a macro-project which intended to describe

and analyze critically the conditions of implementation of the NBP in Santiago

de Cali, Colombia. This project comprised ten subprojects addressing school infrastructure,

EFL teachers, students and parents, respectively. One of the subprojects intended

to establish the English teachers’ demographic, socio-economic and

academic profiles. The academic profile considered initial teachers’

education, updating, language proficiency, and methodology. This latter is the

focus of the present paper.

The importance of a study in this field lies in that it shows, on the

one hand, teachers’ conceptions about foreign language, its learning and

its teaching; on the other hand, it allows assessing teachers’ practices

in the light of current tendencies of EFL teaching while it also allows

evaluating the conditions for the implementation of the PNB. This means that

this study casts light not only on the teachers’ practices but also on

their conceptions.

Theoretical Perspectives

Understanding language

teachers’ methodological conceptions and practices requires reviewing conceptual grounds mainly in

relation to methodology, method, approach, curriculum, and syllabus.

English

Teachers’ Methodological Orientations

Since

the notion of “method” was established from the direct method

(Richards & Rodgers, 2001, p. 14), almost a century of methodological

controversy took place. That discussion has currently faded, after its peak

between the 1950s and 1990s. Originally, methodology is knowledge about

methods, the theory about teaching practice. For Brown (1994a, p. 51),

“methodology is the study of pedagogical practices in general. Whatever

considerations are involved in ‘how to teach’ are

methodological.” According to Rodgers (2001, p. 1), “a more or less

classical formulation suggests that methodology links theory and

practice.” In turn, method is a more or less prescriptive set of

ways of doing things: procedures in terms of teaching strategies, techniques

and activities, altogether with stipulations about contents and the functions

of teachers, learners, and materials. Method refers to the practical

side of teaching while methodology is concerned with the comprehension

of methods.

Taking

Anthony’s ideas, Richards and Rodgers (2001, p. 20) refer to approach

as “theories about the nature of language and language learning that

serve as the source of practices and principles in language teaching.”

Thus, approaches are on the theoretical side of the continuum, while methods

are on the practical end. However, it is necessary to tell methods apart from

approaches, which are general in nature and do not refer to specific ways of

doing things in the classroom (Anthony and Mackey, as cited in Richards &

Rodgers, 2001; Pennycook, 1989; Richards, 1990;

Holliday, 1994; Brown, 1994a, 1994b; Richards & Rodgers, 2001). Approaches

contribute to the theoretical support for methods, which are more or less their

realization.

As

our main purpose in this article is to present the findings of our research

regarding the methodological orientations and practices of teachers of English

in Cali, we will not dwell on the historical account of the most important

methods and approaches to language teaching, which constitutes a good deal of

the modern history of language teaching and has occupied a significant part of

applied linguistics literature (Kelly, as cited in Richards & Rodgers,

2001; Stevick, 1980, 1998; Howatt,

as cited in Richards & Rodgers, 2001; Brown, 1994a, 1994b; Richards &

Rodgers, 2001; Celce-Murcia, 1991; Germain, 1993; Larsen-Freeman, 2000; Kumaravadivelu,

1994, 2001, 2003). We will only list and situate methods and approaches

briefly:

• The grammar-translation or classic method: The teaching was carried out through the translation of classic literary excerpts and the explanation of structures of the target language in contrast with the ones from the mother tongue. This pre-scientific methodological orientation prevailed between the 1840s and the 1940s but has still had a widespread survival to date.

• The series method: This method advocated that it is more important to learn sentences to speak than words; that verbs are the key elements in sentences, and that sentences are more easily learned when they form a narration. The idea was to have students memorize sentences in sequence, related to the same ‘theme’, teaching students directly—without translation—and conceptually—without grammatical rules and explanations, a series of connected sentences that are easy to understand.

• The direct or Berlitz method: The first method as such, developed at the end of the 19th century. Its basic principle was that meaning must be conveyed directly in the target language by means of demonstration and visual aids, which means avoiding translation.

• Oral approach or situational language teaching: Originating in the United Kingdom, in the 1920s, it was popular up to the 1960s. This approach to methodology was based on the orderly principles of selection, gradation and presentation of vocabu lary and grammar items.

• The Audio-Lingual Method (ALM), or Army method, or oral approach, or aural-oral approach or structural approach: This was a linguistics-based teaching method that focused on pronunciation and thorough oral drilling of sentence models of the target language. It started in the 1930s and was in vogue in the 1950s in the United States.

• Total Physical Response (TPR): Developed by a professor of psychology at San Jose State University, California, this teaching perspective associated speech and physical action, taking into account that children first respond physically to commands even before being able to speak.

• The silent way: A method resulting from the emphasis on human cognition and the cognitive approach. It was based on learners’ capacity for discovery and awareness, already learnt with their mother tongue. By means of Cuisenaire rods, word charts, and game-like activities, teachers provide feedback to the students about vocabulary, grammar and spelling without modeling or repetition or even speaking. This latter feature expressed the principle of subordination of teaching to learning, minimizing the teacher’s role and maximizing learners’ capacities for learning.

• Suggestopedia or desuggestopedia: Another method developed from psychology in the early 1960s. It based teaching on the power of affection and suggestion by creating a comfortable and suggestive environment that helped eliminate (de-suggest) fear and negative feelings or “psychological barriers” that hinder learning. That environment was accompanied by a positive and authoritative role of the teacher, who should be specially trained in acting and psychology as well.

• Community Language Learning (CLL): A 1970s method to teach languages based on psychological counseling techniques to learning. In this scheme, the relationship between the teacher and the student is that of counselor-client: The role of the teacher is not to tell the student what to do but to help and guide her/him to explore; the role of the learner is then to decide what to explore and to what extent, thus determining content.

• Whole language: This 1960s and 1970s perspective rose as opposed to teaching languages by focusing on the separate components of language, considering it as a complete meaning-making system whose parts are closely related and work as an integrated whole. Thus, they should be taught in an integrated way, not isolated for direct instruction and reinforcement, by using the learners’ own experience and naturally occurring situations that require listening, reading, writing, and communicating with others.

• Multiple Intelligences (MI): This early 1980s learner-based perspective viewed education as aimed at developing the multiple types of intelligence. The implication for teaching is that teaching must accommodate the various ways the learners learn.

• Neurolinguistic Programming (NLP): It consists of a set of training techniques from psychology applied to many learning fields, not only language education. Its origin, in the mid 1970s, blends linguistics, mathematics and psychology. Its bottom line is the close relationship between brain, language and body. The first principle is that we do not perceive reality directly. It is our ‘neurolinguistic’ maps of reality that determine how we behave, not reality itself. It is generally not reality but our perception of reality that limits or em powers us. The second principle is that life and mind are systemic processes. Our bodies, our societies, and our universe form an ecology of complex systems and sub-systems all of which interact with and mutually influence each other. It is not possible to completely isolate any part of the system from the rest of the system. The people who are most effective are those who have a map of the world that allows them to perceive the greatest number of available choices and perspectives.

• Communicative Language Teaching (CLT): In the 1980s, interactive views of language teaching prevailed over the rest of the methods and approaches. CLT originated in the British rejection of situational language teaching and the American refutation of audiolingualism.

• The natural approach: A view in the tradition of language teaching methods based on observation and interpretation of how first and second languages are learnt in informal settings in a grammatically unordered sequence.

• Cooperative Language Learning (part of Collaborative Learning - CL): This approach to teaching is based on pair and small-group activities working together exchanging information in order to learn.

• Content-Based Instruction (CBI): This approach to second language teaching builds its syllabus around contents and not on linguistic items, language being not an end itself but a means to learn a subject.

• Learning strategy training: This learner-centered teaching method rose from research on what successful (and non-successful) learners do.

• The lexical approach: This point of view is based on the belief that what is central to the language is vocabulary.

• Competency-Based Language Teaching (CBLT) or Competency-based Education (CBE): Unlike most methods and approaches emphasizing the importance of input for language learning2, CBE focuses on the outcomes or products of learning, regardless of the way of learning.

• Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) or Task-Based Instruction (TBI): This approach centers language learning on the development of natural or real interactive or communicative tasks.3

When

analyzed, methods and approaches to language teaching can be classified in a

variety of ways:

- According to the discipline(s) they originate/draw from:

linguistics-based (oral approach, audio-lingual, whole language, CLT,

etc.), psychology-based (NLP, MI, suggestopedia,

TPR, etc.), philosophy-based4 (CL, learning strategy training, etc.).

- According to their direction: input-, process-, or

output-oriented.

- According to their focal point: learner-, teacher-, content-

or learning-centered.

- According to the pedagogical background involved in them:

hetero-, auto-, inter-structuring (Not, 2000).

- According to the epistemological moment they belong to:

- Pre-scientific—before the XIX

century—and scientific orientations.

- Methods era (1930s-1990s)

- Post-methods

era (eclecticism5).

Despite

classifications, each method or approach can be seen simultaneously from

different perspectives, and they can share traits belonging to different

taxonomies. Table 1 summarizes the three major methodical

stages and their corresponding theoretical views about language and language

learning.

Throughout

the long record of methodical or methodological discussions each method proved

to have its own advantages and disadvantages. Nevertheless, the disapproval to

approaches and methods grew (Prabhu, 1990; Kumaravadivelu, 1994; Brown, 1997; Richards, 1998) mainly

in regard to their prescriptive nature that treated teachers as passive

appliers, and their lack of sufficiency to the ever-changing particular

educational settings teachers face in their everyday practice. A consensus

about the impossibility and inadequacy of finding the panacea method, one that

can be applied universally, was reached. The use of the term

“methodology” spread to refer to teaching practices, as the concept

of “method” was no longer central in teachers’ philosophy

(Brown, 1994a, p. 49). A post methods era was advocated (Kumaravadivelu,

1994; Richards & Rodgers, 2001), an era of informed or enlightened

eclecticism that requires language teachers to know not only methods (in

plural) but also about methods and to teach according to their

particular setting.

As

a wrapping up, regardless of the methodological orientation, methodology,

approach or method, language teaching implies theoretical foundations

(regarding the nature of language, language learning and language teaching),

knowledge about methods, design (curricular or instructional system), and

practical classroom procedures (strategies, techniques, activities). It is the

methodology (methodical integration and curricular design) that mediates

between the theory/approach and the practice/method.

Curricular

Design

In

pedagogic literature, curriculum has been defined in a number of ways: as

a product (Tyler, 1949), as a practice (Stenhouse,

1975), as praxis (Grundy, 1987), and as context impact (Cornbleth,

1990). In language teaching literature, Brown (1994a, p. 51) affirms that the

terms curriculum and syllabus are American and British terms for

the same concept, designs for carrying out a particular language program.

However, these two concepts are often conceived as different: For White (1988),

syllabus denotes the content or subject matter of an individual subject,

while curriculum designates the totality of content to be taught and the aims

to be realized within one school or educational program. For Graves (1996,

2000), curriculum stands in the broadest sense as the philosophy,

purposes, design, and implementation of a whole program, whereas a syllabus

refers narrowly to the specification and ordering in content of a course or

courses.

It

is in this wide-scope sense that we understand curriculum in consonance

with the Colombian Ministry of Education (MEN) definition:

Curriculum is the set of criteria, area plans6, syllabi7, method-ologies8, and processes that contribute to the integral education and to the building of the national, regional, and local cultural identity. It also includes the necessary human, academic, and material resources necessary to carry out the institutional educational project. (MEN - Law 115, 1994, Art. 76)

We

also agree with Fandiño’s (2010) idea of

the 21st century curriculum being understood as

A sociocultural process consisting of a series of pedagogical actions activated when planning, developing, and assessing a critical and transformative educational program aimed at integrating contextually shaped teaching and learning realities, practices, and experiences.

And whose characteristics

are:

- open to critical scrutiny and capable of effective application

- based on informed action and critical reflection

- in favor of a dynamic

interaction of students, teachers, knowledge, and contexts.

On

the other hand, the syllabus has been defined by different authors as

follows:

According

to Candlin (1984, p. 30), the syllabus is

concerned with the specification and planning of what is to be learned, frequently set down in some written form as prescriptions for action by teachers and learners. They have, traditionally, the mark of authority. They are concerned with the achievement of ends, often, though not always, associated with the pursuance of particular means.

Nunan (1988, p. 159) conceptualizes it as:

a specification of what is to be taught in a language program and the order in which it is to be taught. A syllabus may contain all or any of the following: phonology, grammar, functions, notions, topics, themes, tasks.

In

turn, Dubin and Olshtain

(1986, p. 28) see it as “a more detailed and operational statement of

teaching and learning elements which translates the philosophy of the

curriculum into a series of planned steps leading towards more narrowly defined

objectives at each level.”

Then,

the difference between syllabus and curriculum is that the latter

is a wider term when compared with the former: Curriculum covers all the

activities and arrangements made by the institution throughout the academic

year to facilitate the learners and the instructors, whereas syllabus is

limited to a particular subject of a particular class. Beyond the mere

definition, and from a more critical point of view, Hadley (1998, p. 51)

considers a syllabus “represents and endorses the adherence to

some sociolinguistic and philosophical beliefs regarding power, education, and

cognition (…) that guide a teacher to structure his or her class in a

particular way. ”

In this article, we

see the syllabus as the course program, which is a small part of the

wider setting covered by the curriculum. Concordant with this conception, a syllabus

(Ur, 1991; Dubin & Olshtain,

1986; Nunan, 1988) is a public comprehensive document

that specifies the orderly components of a course or series of courses in terms

of contents (vocabulary, grammar/structures, functions, topics) and process

(explicit aims/goals/objectives, teaching and learning tasks,

materials/resources associated with those tasks, evaluation/assessment, and—sometimes—approach/method,

time schedule or pacing guidelines).

At this point, it

should be clear for the reader that we are following a “top-down”

theoretical sequence, from the widest concept of curriculum, linked to

educational principles, to the increasingly narrower ones of syllabus, course,

lesson and task/activity. Between the wide concept of “curriculum”,

concerning the general principles, that guide the whole educational action, and

the particular one of “syllabus” or course program, there is the

concept of “area plan” or “area curriculum”, the one

referring to a particular subject, e.g. the foreign language, social sciences,

mathematics, etc. Foreign language area plans contain the theoretical

principles about language, language learning, and language teaching, as well as

the pedagogical and methodological guidelines for the area, which may vary

according to the subject.

Although course

and lesson are everyday terms for language teachers and learners,

let’s see some authoritative definitions about them. According to

Hutchinson and Waters (1996, p. 65), a course is an integrated series of

learning and teaching experiences whose ultimate aim is to lead the learners to

a particular state of knowledge. It is a common place to think of a course as

formal education conveyed through a series of lessons or class meetings.

For Ur (1991),

the lesson is a type of organized social event that occurs in virtually all cultures. Lessons in different places may vary in topic, time, place, atmosphere, methodology and materials, but they all, essentially are concerned with learning as their main objective, involve the participation of learner(s) and teacher(s), and are limited and pre-scheduled as regards time, place and membership. (p. 213)

Ur (1991, p. 214)

highlights aspects of the lesson that may be less obvious, but which are

significant: (a) its transactional character; a lesson is a transaction or

series of transactions with the aim of mental or physical changes in the

participants, (i.e. learning); (b) its interactive nature; here what is

important are the social relationships between learners, or between learners

and teacher (see also Prabhu, 1992), and (c)

goal-oriented effort, involving hard work. This implies awareness of a clear,

worthwhile objective, the necessity of effort to attain it and a resulting

sense of satisfaction and triumph if it is achieved, or of failure and

disappointment if it is not. (d) A role-based culture, where teacher roles

involve responsibility and activity, the learners’ responsiveness and

receptivity. (e) A conventional construct, with elements of ritual. Certain set

behaviors occur every time (for example, a certain kind of introduction or

ending), and the other components of the overall event are selected by an

authority from a limited set of possibilities.

To conclude, the design

(methodology) involves, from the macro level to the micro level (i.e. from

school curriculum to area plans to a course or series of courses to a lesson or

a series of lessons to an activity or group of activities), the situated

definition of the objectives, the syllabus (the contents and their

organization), the type of learning tasks and teaching activities, the roles of

learners, teachers and the instructional materials, as well as the

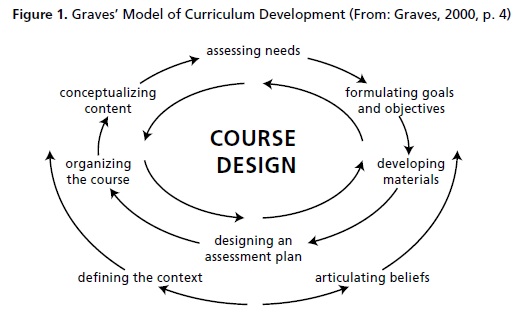

assessment/evaluation plan. Figure 1 shows Graves’

model of curriculum development, which contains the aforementioned curriculum

design components.

Research Method

Context of the

Study

The exploration of

the EFL teaching methodological practices in Cali was part of a macro study

aimed at describing and analyzing the conditions of the implementation of the

Colombian National Bilingualism Project (NBP) in public and private schools in

Cali, Colombia. This macro research project comprised ten sub-projects covering

crucial conditions that might hinder or foster the accomplishment of the NBP

policy: school infrastructure and the profiles, attitudes and expectations of

the administrative staff, EFL teachers, students, and parents. The research

group gathered seven professors from two universities, Universidad del Valle and Universidad San Buenaventura, ten

undergraduate students and four graduate students. The information was

collected in 56 strata one-to-four institutions, 23 private and 33 public, in

the 22 city political districts or comunas.

Research Questions

The sub-project

that studied the teachers’ profiles covered their socio economic,

demographic, and academic features. These latter traits included pre-service

qualifications, in-service updating studies, experience, self-perceived and

tested proficiency, as well as methodological conceptions and practices, among

other aspects. This particular aspect of the research asked about the

methodological views and practices of the English teachers. The specific

questions about the methodological orientations of the EFL teachers in Cali

were these:

- Which are the EFL teaching

approaches and methods English teachers usually adopt?

- Do they consider their teaching

to be traditional or conservative?

- Are they eclectic or do they

adopt any particular method(s)?

- If they are eclectic, which are

the components of their eclecticism?

- If they adopt any particular

method(s), which method(s) do they adopt?

The questions about their methodological practices

were the following:

- What is a usual EFL lesson

like?

- What elements are used in

evaluation?

- Which

are their goals?

Participants

A total of 220

English teachers participated in the study: 131 from the public sector and 89 from

private schools. However, not all teachers provided information gathered with

the different instruments; only 188 of them sent the survey back to us; 56 of

them were interviewed (focal groups plus some individual interviews).

Data Collection and Analysis

Instruments

The information was

gathered through surveys, interviews and institutional documents like

curriculum/area planning, syllabi and class materials. The survey was the

instrument providing most of the information; the teachers submitted few plans,

syllabi and class materials.

The quantitative

information from the survey was processed with the Statistical Package for the

Social Sciences (SPSS) and Excel while the qualitative information, from the

survey, the focal interviews, and the documentary analysis, were analyzed

hermeneutically in the light of the literature about approaches and methods,

curriculum, course design, evaluation, and other pertinent topics. An analysis

grid was used for the examination of institutional documents (area planning,

syllabi, and didactic materials).

Findings and Discussion

Teachers’ Methodological

Orientations

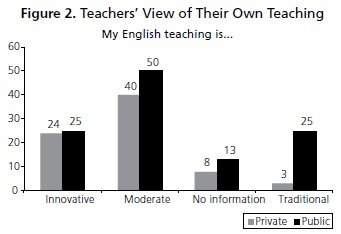

Regarding approaches

and methods teachers were asked whether they considered their teaching

to be traditional, moderate or innovative (see Figure 2).

We used this conceptual reference based on literature about language trends

(Richards & Rodgers, 2001; Larsen-Freeman, 2000; Kumaradivelu,

2001, 2003, 2006, 2012, and other authors like Mackey, Howatt,

and Kelly, as cited in Richards & Rodgers, 2001).

Most teachers

consider themselves to be moderate, as their teaching oscillates between

innovative and traditional practices. They support their choice saying that on

the one hand, they can be innovative due to context possibilities like

available tools, new technologies, interactive software, and engaging

activities. On the other hand, they cannot be innovative due to context

restrictions such as students’ low level of motivation, students’

low level of knowledge, lack of resources, large classes, and low number of

teaching or class hours for the area.

What is more

interesting is not that the teachers consider themselves moderate in their

practices as a consequence of the tension between context constraints and

opportunities, but their perception about innovative and traditional practices.

According to them, traditional practices are associated with teacher-centered lessons, work on isolated vocabulary and repetition, grammar

teaching, etc. In turn, innovative practices are associated with the use of new

methodologies (PBL), new technologies (TIC), written production, games, dynamic

activities, working with complete texts and student-centeredness (flexibility

regarding learning rhythms and styles). From this, it can be inferred that

their conception of innovation is rather weak; aspects such as autonomy,

collaborative learning, meta-cognition, and post-method approaches are not

mentioned by them.

The relationship

that teachers establish between traditional teaching, their low English

proficiency level and their deficiency in the use of new technologies (due to

lack of knowledge) is also noteworthy. Teachers feel that their language level

or the students’ level is too low to be innovative; in one

teacher’s words: “As my English level is too low, I can only work

on easy activities with my students” (T1089). This reflection

points at teachers’ awareness. This is consistent with the findings

reported by González and Sierra (2011) regarding teachers’

commitment and motivation despite a lack of teaching resources.

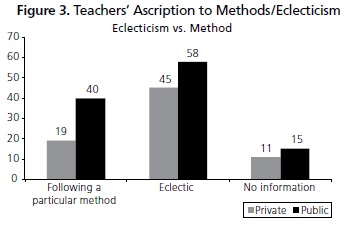

When asked if they

are eclectic or adopt any particular method(s), most teachers ascribe to

eclecticism (see Figure 3). They relate it to the combined

use of repetition, conversation, explanation, grammar exercises and

translation. These components are in fact more activities than methods, and in

that sense they are not true or actual components of an eclectic orientation.

Teachers support

their choice on reasons such as influence from the environment, knowledge

gained through experience, need to get adjusted to institutional requirements

(program, school book, ICFES state exam, etc.), demands of national policies

for primary teachers who are not professional in foreign languages, lack of the

appropriate conditions (resources, time, institutional support, course size,

etc.). “I have groups of 45 – 50 students; with that number of

students and the lack of resources you can do little” (T121). These

reasons put the weight of responsibility mainly on aspects external to the

teachers themselves. This might be interpreted as weakness in teachers’

autonomy.

Furthermore, a

large number of teachers who affirm to be working with a specific

methodological orientation were unable to specify their components. This

indicates that teachers are not clear about what eclecticism implies; nor are

they clear about other possible methodological approaches to be adopted, or

about the particularities of the methods they ascribe to. This finding is

consistent with what Kumaravadivelu (2003, pp. 29-30)

summarized from other authors like Swafer, Arens and Morgan; Nunan; Legutke and Thomas; and Kumaravadivelu:

- Teachers

who are trained in and even swear by a particular method do not conform to

its theoretical principles and classroom procedures,

- teachers

who claim to follow the same method often use different classroom

procedures that are not consistent with the adopted method,

- teachers

who claim to follow different methods often use same classroom procedures,

- and over

time, teachers develop and follow a carefully delineated task-hierarchy, a

weighted sequence of activities not necessarily associated with any

established method.

Up to here, while a

lack of methodological clarity is linked with the need of theoretical support

of teaching practice, moderateness refers to situational constraints. This

strain between weak theoretical support and situational tension constitutes the

background for the EFL teachers’ methodological practices.

Teachers’ Methodological

Practices

Teachers’

practices were inferred from what they say about what they do in the survey (Appendix A), interviews, and from documentary analysis (area and

course planning, samples of class and evaluation materials) (Appendix

B). This construction is approached here on the basis of the design

elements: objectives, activities and learning tasks, contents

and their organization, evaluation, roles of teachers, learners,

and materials.

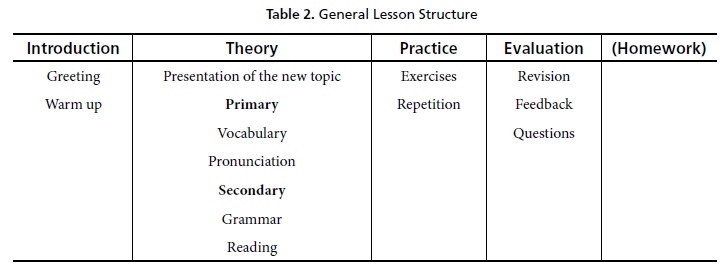

In order to achieve

their goals, teachers were prompted to tell what they usually do in a lesson. Table 2 shows the resulting general structure of a typical

lesson in terms of the usual activities sequence in it.

The usual class

organization is made around activities moving from introduction and

development of the topic (first theory, then practice), evaluation,

and—sometimes—homework. We also found that despite the activity-centered

lesson structure being the most common, a lesson can also be organized

according to axes other than activities. We found lessons structured from class

arrangement (individual, pairs or whole class work), contents (grammar,

vocabulary, skills), and materials (textbooks, written or audio texts, images).

When contrasting

the class organization between primary and secondary schools, some differences

were identified. In primary, the emphasis is placed on vocabulary, speaking

(largely in terms of pronunciation) and writing in terms of copying from the

board. In secondary schools, the emphasis is placed on grammar, listening and

reading. This difference can be explained on the basis of primary

teachers’ reflections regarding their low level of English, which leads

them to work chiefly on vocabulary. Unlike primary teachers, secondary teachers

are subject teachers; it means they have a better knowledge of the area so as

to be able to work with grammar, skills and complete texts.

It is interesting

to see that the primary level is considered as “easy”, associated

with vocabulary (lists of isolated words) and pronunciation (often understood

as “speaking”), something that can be taught without much

preparation. The secondary level is in turn seen as “difficult”,

linked to work around grammar and skills, an area that requires skilled

teachers.

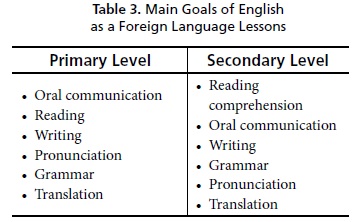

Regarding goals,

it came out that teachers center their

interest in the development of oral communication,

reading and writing skills (see Table 3).

In

the analysis of the importance teachers give to goals, it was found that for

secondary teachers these goals do not correspond with what they express about

their class organization. Teachers accepted their focusing mainly on

grammatical topics (see Table 2); however, when talking

about goals, they do not give grammar a leading position. Likewise, there is a

mismatch between goals and class organization in primary level teachers:

Pronunciation does not have a remarkable position as a goal despite playing a

central role in the class organization. Oral production is focused on

pronunciation of words, as vocabulary is the central content.

A

possible explanation of this mismatch might be, on the one hand, the type of question

used in the survey questionnaire. The options given to the teachers in this

question could have influenced their answer, in opposition to the question

about class organization, which was an open question. On the other hand, it

might be that teachers recognize the importance of changing their practices,

but these changes have not materialized yet. This gap between theory and

practice is an area to be worked with teachers.

The

most common lesson activities were explored on the basis of the elements

that are present in teachers’ answers, as well as the elements not

considered when regarding activities. In primary schools, the results showed

vocabulary again as the center of the work in class. In secondary, what can be

seen is that the “evaluative paradigm” might be influencing the

methodological practices, responding to the improvement of test taking

strategies like multiple-choice, completion with words, matching, etc. Composition, dialogues, research, projects and

presentations were not mentioned by teachers. This confirms what was mentioned

above about a limited perspective of foreign language learning and teaching

(see Table 4).

Contents were deduced from information

provided in relation to objectives and activities for evaluation; also, from

course plans and material provided by some institutions. Three types of

contents were

identified: those related to communicative functions and skills, those built in

terms of topics, and grammar items, which take the lion’s share of

contents. As mentioned before, emphasis on vocabulary and pronunciation is made

at the primary level while at the secondary level the main focus is on grammar

and the development of skills needed for accomplishing evaluative tasks.

These

results point at the still prevailing presence of

“grammar-translation” and at a negative effect of the

accountability paradigm underlying current foreign language national policies.

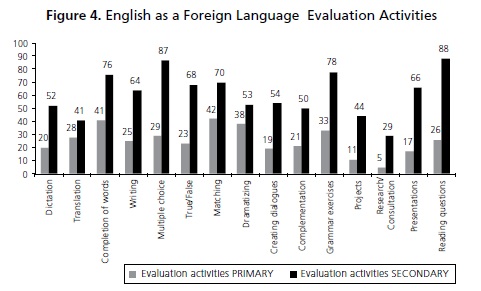

In

regard to evaluation activities, the most common evaluation activities

in primary schools are matching and completion with words. The most common

evaluation activities in secondary schools are reading comprehension questions

and multiple choice questions.

These

most common evaluation activities correspond to the activities teachers

highlighted when talking about common activities in their classes. This

confirms the outcomes about lesson organization, goals and most common class

activities. It also confirms the differences between primary and secondary

schools. Besides their consistency, the results show—again—the

effect of “evaluationism” in foreign

language teaching: ICFES-like exams, exercises, and questions have become

trendy among EFL teachers, both at the primary and the secondary level. It

seems more important to prepare students for passing tests (and show good

achievement indicators for institutions and teachers) than really enabling them

to use the language for communicative purposes (see Figure 4).

The

institutional documents collected for the study were area plan or area

curriculum (plan de area), syllabi, and class and

evaluation materials. The idea was to build knowledge about the

teachers’ methodological practices as they are usually reflected on these

types of documents. Besides, this was an indirect way of approaching what

teachers do in their classes as direct observation was not possible due to the

number of teachers participating in the study. Though not many documents were

provided, some important methodological features were identified. Area plan or

area curriculum is usually a collection of syllabi, not supported by any

theoretical or methodological considerations regarding language, its learning

and teaching, or pedagogical perspectives that should guide the subject. Syllabi

are characterized by their lack of explicit objectives, their focus

on standards, grammar-centered content and activities emphasizing reading,

vocabulary and structures; evaluation is stated in terms of topics and

activities, but not in terms of standards. Not many class materials

were provided by teachers; most of them were evaluation materials; they reflect

the emphasis placed on grammar and the predominant types of questions are

completion with words, multiple choice, and writing. It is noteworthy that no

objectives are formulated with these materials. The absence of

objectives—in contrast to the presence of standards, which are not taken

into account for evaluation–shows the need of working more deeply on the

understanding of current foreign languages methodological perspectives.

Conclusions

We

have presented the findings about the methodological orientations and practices

adopted by primary and secondary English teachers in public and private schools

in Cali, Colombia. The information was analyzed with the understanding that

what is usually known as “methodology” involves considering

approach/method awareness and instructional design whose main components are

objectives, syllabus (contents and their organization), learning tasks and

evaluation activities, among other aspects.

Under

this perspective, it became apparent that teachers’ choices concerning

the methodological orientation for their English classes have more to do with

institutional and class conditions than with their conceptual grounds, which

are rather weak and associated, for instance, with grammar-translation,

pre-communicative views and empiricist actions. This means that the practice

overrules the theoretical principles. EFL teaching in the context studied seems

to be shaped mainly by situational conditions. The immediate implication is

that the implementation of the NBP requires not only teachers’

theoretical-methodological updating but also provision of appropriate

conditions for teaching and educational innovation.

Teachers

are conscious of the existence of different theoretical methodological options,

which could be the support for their practices, but they lack sound knowledge

about them. They are also aware of their own limitations and those generated by

the working conditions in the institution or in the classroom. A good deal of

governmental and policy-enforcing actions addressed to bridge those gaps must

accompany teachers’ efforts in order to fulfill, on their own, the task

they were forcibly assigned and are trying to carry out.

Teachers’

methodological options are determined—from their perspective—by the

possibilities and constraints they find in their school context. In this

respect, teachers show a great coincidence, evidenced in their conception of

what being innovative, moderate and traditional implies. Teachers’ view

of innovation and tradition reflects gaps dealing, first, with generational

characteristics: while TICs are new for them and they have difficulties with

their use, it is not so for their students, who feel at ease with modern

gadgets and are well ahead of most teachers regarding that area. Second, there

is a deep gap between theory and practice: ludic activities and work with whole

texts and skills in a communicative way are still new/innovative

to many of our EFL teachers in secondary schools, despite having been described

in literature decades ago.

Teachers’

work on language—mainly around vocabulary, pronunciation, and

grammar—reflects not only an outdated conception, but an incomplete one

for secondary teachers (prepared in the EFL teaching field). There is an urgent

need of a deeper comprehension of recent perspectives about language. For

primary school teachers, the situation is worse. Forced by law to play a role

they are not prepared for and in absence of sound support for that burden, they

have resorted to interim measures to teach the foreign language such as crash

courses of language or didactics. However, this is not enough; teaching EFL

requires real proficiency and sound methodological preparation that cannot be

achieved overnight.

The

teachers recognize the importance of changing their practices, but these changes

need to be made real. For these changes to be fulfilled, the gap between theory

and practice must be overcome. It is necessary for teachers to be able to tell

methods (e.g. TBL, PBL, CBLT, etc.) apart from activities (composition,

dialogues, research, projects and presentations) and that they are

able to recognize the fundamental principles of methods and methodological

approaches. This need might be relatively easy to fulfill as teachers from

primary and secondary level feel the need for Teacher Development Programs

(TDP) and are clear about what they need in order to do a better job. A

steadfast TDP national, regional, local and institutional effort seems a

necessary practical counterpart to our foreign language policies. The Ministry

of Education and the departmental and city Secretarías

de Educación, as well as the universities

with foreign/modern language licenciaturas

(B.A. or B.Ed. Programs) must coordinate their role in the fulfillment of the

NBP, bearing in mind that focus on language mastery is just half of the issue,

for the methodological preparation is the other sine qua non condition to teach

any foreign language, altogether with the provision of appropriate conditions

to carry out the kind of foreign language teaching this challenging era requires.

Awareness

should be raised in those who lead the educational processes to provide the conditions

necessary (regarding resources) for the goals of education policies like the

NBP to be met. Miranda and Echeverry (2010) studied

this particular issue and found an evident urgency for considering real needs

in relation to resources for teaching a foreign language in our Colombian

context. Without adequate conditions to turn policy into actual practices, the

challenge represented by the NBP becomes a burden the EFL teachers cannot

carry. The responsibility for the success of the NBP cannot be put only on

teachers’ shoulders. They do need to improve their proficiency level and

to update their methodological views and practice, but that will not be enough;

supportive actions towards the NBP among policy makers, education authorities,

and school administrators must address educators’ needs regarding

conditions to adopt effective methodological orientations and practices to meet

the new goals in the area.

1 The CEFR

scale is the following: A (Basic User), B (Independent User), and C (Proficient

User). Each is subdivided like this: A1 (Breakthrough), A2 (Waystage),

B1 (Threshold), B2 (Vantage), C1 (Effective Operational Proficiency), and C2

(Mastery) (Council of Europe, 2001, p. 23).

2 The standards movement that has

dominated educational discussions since the 1990s is a realization of this

perspective (Richards & Rodgers, 2001, p. 142).

3 Project-based learning (PBL) is

closely associated with TBL; here, we consider the former as part of the

latter.

4 The most influential sciences

have been linguistics and psychology; however, a few methods have been heavily

influenced by social, political or cultural (philosophical) schools of thought.

5 Eclecticism can be seen either

as an approach or as a coherent blend of two or more methods.

6 Planes de estudio.

7 Programas de estudio (course programmes).

8 Understood as teaching procedures that can cover various methods.

9 Teacher 108. Teachers in the sample were given numbers for

their identification in the treatment of the information.

10 The original survey was carried out

in Spanish. The section here corresponds only to the methodological knowledge

and practice.

References

Anthony, E. (1963). Approach, method, and technique. English

Language Teaching Journal, 17, 63-7.

Brown, D. (1994a). Teaching by principles. An

interactive approach to language pedagogy.

New York, NY: Prentice Hall Regents.

Brown, D. (1994b). Principles of language learning and teaching. New

York, NY: Prentice Hall Regents.

Brown, D. (1997). English

language teaching in the “post-method” era: Toward better

diagnosis, treatment, and assessment. PASAA. A Journal of Language Teaching and Learning in Thailand, 27,

1-10.

Candlin, C. N. (1984). Syllabus

design as a critical process. In C. J. Brumfit

(Ed.), General English syllabus design. ELT Documents No. 118

(pp. 29-46). London, UK: Pergamon Press & The British Council.

Celce-Murcia, M. (1991). Language teaching approaches: An

overview. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.),

Teaching English as a second or foreign language (pp. 3-11). New

York, NY: Newbury House.

Colombia. Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN]. (1994). Ley

115, Ley general de Educación. Bogotá, CO: Imprenta Nacional.

Colombia. Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN]. (2006a).

Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo. Retrieved from

http://www.colombiaaprende.edu.co/html/productos/1685/article-158720.html

Colombia. Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN]. (2006b). Estándares

básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras: inglés. Bogotá, CO: Serie Guías N° 22.

Cornbleth, C. (1990). Curriculum

in context. Basingstoke, UK: Falmer Press.

Council

of Europe, (2001).

A Common European Framework or reference for

language, learning, teaching, assessment. A general guide for users. Strasbourg, FR: Council of

Europe.

Dubin, F., & Olshtain, E.

(1986). Course design: Developing

programs and materials for language learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Fandiño, Y. J. (2010, April). Curriculum

development and syllabus design in the postmodern era [PowerPoint slides].

Paper presented at the XIII National ELT Conference “Challenges for the

ELT Syllabus: Developing Competencies For The 21st Century”. Bogotá,

Universidad de La Salle. Retrieved from

www.britishcouncil.org/colombia-ingles-elt-conference-2010-presentaciones-yamith-fandino-ppt.pdf

Germain, C. (1993). Evolution de l’enseignement des langues:

5000 ans d’histoire.

Paris, FR: Nathan-Clé

International.

González, A., & Sierra, A. M. (2011, October).

Challenges and opportunities for public elementary school teachers in

the National Program of Bilingualism [PowerPoint slides]. Paper presented at the 46th ASOCOPI Annual

Conference, Bogotá, Colombia.

Graves, K. (Ed.). (1996). Teachers as course developers. Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press.

Graves, K. (2000). Designing language courses. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Grundy, S. (1987). Curriculum: Product or praxis.

Lewes, UK: Falmer Press.

Hadley, G. (1998). Returning full circle: A survey of EFL syllabus designs for the new

millennium. RELC Journal, 29(2), 50-71.

Holliday, A. (1994). Appropriate methodology and social context. New York,

NY: Cambridge University Press.

Hutchinson, T., & Waters, A.

(1996). ESP: A learning centred approach. London, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (1994). The

postmethod condition. (E)merging

strategies for second/foreign language teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 28(1),

27-48.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2001). Toward

a postmethod pedagogy. TESOL Quarterly,

35(4), 537-60.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2003). Beyond

methods. Macrostrategies for language teaching.

London, UK: Yale University Press.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2006). Understanding

language teaching. From method to post-method. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2012). Language teacher

education for a global society: A modular model for knowing, analyzing,

recognizing, doing, and seeing. New York, NY: Routledge.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2000). Techniques and principles in language teaching.

Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Miranda, N., & Echeverry, A. P. (2010). Infrastructure and resources of

private schools in Cali and the imple-mentation of

the Bilingual Colombia Program. HOW A Colombian Journal for Teachers of English, 17, 11-30.

Not, L. (2000). Las

pedagogías del conocimiento. Bogotá, CO:

Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Nunan, D. (1988). Syllabus design.

Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Pennycook, A. (1989). The

concept of method, interested knowledge, and the politics of language teaching.

TESOL Quarterly, 23(4), 591-615.

Prabhu, N. S. (1990). There is no best

method - Why? TESOL Quarterly, 24(2), 161-176.

Prabhu, N. S. (1992). The dynamics of a language lesson. TESOL Quarterly, 26(2),

225-241.

Richards, J. C. (1990). The language teaching matrix. Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J. C. (1998). Teachers’ maxims. In J. C. Richards (Ed.) Beyond training (pp. 49-62). New York, NY:

Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers,

T. S. (2001). Approaches and methods in language teaching.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Rodgers, T. (2001). Language

teaching methodology. CALdigest. Issue paper. Online Resources:

Digests, September 2001. Retrieved from

http://www.cal.org/resources/digest/rodgers.html

Stenhouse, L. (1975). An introduction to curriculum research

and development. London, UK: Heineman

Educational Books.

Stevick, E. W. (1980). Teaching

languages: A way and ways. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Stevick, E. W. (1998). Working with

teaching methods: What’s at stake? Boston, MA: Heinle

and Heinle.

Tyler, R. W. (1949). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction.

Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Ur, P. (1991). A course in language teaching. Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press.

White, R. (1988). The ELT curriculum, design, innovation and management.

Oxford, UK: Basil Backwell.

About the Authors

Appendix A: Survey Regarding

Methodological Knowledge and Practice10

4.5. Methodological knowledge

and practice

4.5.1. My teaching of English is:

4.5.1.1. Innovative ___ 4.5.1.2. Moderate ___

4.5.1.3. Traditional ___

4.5.1.4. Why? ______________________________________________________

4.5.2. My teaching is:

4.5.2.1. Adjusted to a specific method ___

4.5.2.2. Eclectic ___

4.5.2.3. If ascribed to a specific method, to which one?

4.5.2.3.1. Audio-oral / audio lingual ___

4.5.2.3.2. Cognitive ___

4.5.2.3.3. Communicative ___

4.5.2.3.4. Natural ___

4.5.2.3.5. Total Physical Response ___

4.5.2.4. Eclecticism components:

4.5.2.4.1. Repetition, conversation, explanation and grammar exercises ___

4.5.2.4.2. Translation, grammar exercises and pronunciation ___

4.5.2.4.3. Reading aloud, translation and conversation in pairs ___

4.5.2.4.4. Translation, writing and grammar explanation ___

4.5.2.4.5. Other ___

4.5.2.4.5.1. Which ones? _____________________________________

4.5.3. My usual lesson in five steps:

4.5.3.1. step 1

4.5.3.2. step 2

4.5.3.3. step 3

4.5.3.4. step 4

4.5.3.5. step 5

4.5.4. Elements I use for evaluation:

4.5.4.1. Dictation ___

4.5.4.2. Translation ___

4.5.4.3. Cloze with words ___

4.5.4.4. Text writing ___

4.5.4.5. Multiple choice ___

4.5.4.6. True-False ___

4.5.4.7. Matching ___

4.5.4.8. Dramatization ___

4.5.4.9. Dialogues ___

4.5.4.10. Completing dialogues ___

4.5.4.11. Grammar exercises ___

4.5.4.12. Projects ___

4.5.4.13. Searches ___

4.5.4.14. Presentations ___

4.5.4.15. Reading comprehension ___

4.5.5. Other evaluation activities:

4.5.5.1. Other 1

4.5.5.2. Other 2

4.5.5.3. Other 3

4.5.5.4. Other 4

4.5.6. Main objectives:

4.5.6.1. Oral communication development ___

4.5.6.2. Writing skills development ___

4.5.6.3. Reading comprehension skills development ___

4.5.6.4. Pronunciation development ___

4.5.6.5. Grammar development ___

4.5.6.6. Translation skills development ___

Appendix B: Elements Resulting from

Documentary Analysis

(Area Planning, Syllabi, and Didactic Materials)

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.