Published

Implementing Task-Based Language Teaching to Integrate Language Skills in an EFL Program at a Colombian University

Implementación de la enseñanza de lenguas mediante tareas para integrar las habilidades lingüísticas de estudiantes en un programa de inglés como lengua extranjera de una universidad colombiana

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n2.49754Keywords:

Integration, language skills, task and communicative competence, task-based language teaching (en)enseñanza de lengua basada en tareas, habilidades del lenguaje, integración, tareas y competencias comunicativas (es)

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n2.49754

Implementing Task-Based Language Teaching to Integrate Language Skills in an EFL Program at a Colombian University

Implementación de la enseñanza de lenguas mediante tareas para integrar las habilidades lingüísticas de estudiantes en un programa de inglés como lengua extranjera de una universidad colombiana

Eulices Córdoba Zúñiga*

Universidad de la Amazonia, Florencia, Colombia

This article was received on March 21, 2015, and accepted on March 12, 2016.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Córdoba Zúñiga, E. (2016). Implementing task-based language teaching to integrate language skills

in an EFL program at a Colombian university. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 18(2), 13-27. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n2.49754.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article reports the findings of a qualitative research study conducted with six first semester students of an English as a foreign language program in a public university in Colombia. The aim of the study was to implement task-based language teaching as a way to integrate language skills and help learners to improve their communicative competence in English. The results suggest that the implementation of task-based language teaching facilitated the integration of the four skills in the English as a foreign language context. Furthermore, tasks were meaningful and integrated different reading, writing, listening, and speaking exercises that enhanced students’ communicative competences and interaction. It can be concluded that task-based language teaching is a good approach to be used in the promotion of skills integration and language competences.

Key words: Integration, language skills, task and communicative competence, task-based language teaching.

Este artículo presenta los resultados de una investigación cualitativa llevada a cabo con seis estudiantes de primer semestre de un programa de enseñanza de inglés como idioma extranjero en una universidad pública colombiana. El objetivo del estudio fue implementar la enseñanza de idiomas basada en tareas como una manera para integrar las habilidades del idioma extranjero y ayudar a los estudiantes a mejorar sus competencias comunicativas. Los resultados sugieren que este enfoque ayudó a integrar las cuatro habilidades de la lengua. Las tareas eran significativas y combinaban diferentes ejercicios en cada habilidad, los cuales mejoraron la comunicación y la interacción entre los estudiantes. En conclusión, la enseñanza de idiomas basadas en tareas facilita la integración de las habilidades lingüísticas.

Palabras clave: enseñanza de lengua basada en tareas, habilidades del lenguaje, integración, tareas y competencias comunicativas.

Introduction

This article reports the findings of a qualitative study conducted in the English as a foreign language (EFL) program of a university in Florencia, Colombia. The research study seeks to implement task-based language teaching (TBLT) as a way to integrate language abilities, taking into account that they are taught in isolation in the majority of English classes. Six different tasks were implemented with students enrolled in the first semester to help them integrate the language skills. In doing so, the participants improved their language competence and were better prepared to learn English as it is used in daily life, for instance, when they spoke, read, listened, and wrote simultaneously.

TBLT was implemented as a response to the way teachers at this university taught English in the first semester, that is, lessons were planned for the mastering of listening, reading, writing, or speaking without proper integration of these four abilities. Second, the students participated in almost all the class activities when they were based on one skill only. However, participation decreased when these exercises integrated reading, writing, listening, and speaking in the same lessons. In addition, some students showed a lack of interest and were reluctant to participate in the classes when these were based on reading or writing. This situation led me to conduct this study in order to enrich the EFL language learning process in the program and help students improve their language learning.

Many researchers and teachers have shown the benefits of integrating language skills in English education. They all state that learning English is more productive when students learn the four skills in a single lesson because it is the way in which learners will probably use the language in their daily lives. According to Baturay and Akar (2007), integrating language skills is fundamental for learners to be competent in the second language (L2) and promote English learning naturally. This integration enhances EFL learning through constant practice and allows students to express their ideas through writing messages, understanding aural and written messages, and holding conversations. Freeman (1996) states that “tasks are always activities where the target language is taught for a communicative purpose (goal) in order to achieve an outcome” (p. 23). Under those considerations expressed above, this study tried to demonstrate that through the implementation of TBLT, language abilities were integrated to promote meaningful language learning.

Theoretical Framework

The field of language teaching has experienced numerous changes in the last few decades. New trends in language teaching and learning try to promote communicative competence instead of mastering grammar, vocabulary, reading, writing, or listening in isolation. At the present, TBLT promotes real practice in the target language and offers different contexts for language study (Izadpanah, 2010). Based on this premise, the theoretical constructs for this study are: Task-Based Language Teaching, Tasks, and Skill Integration.

Task-Based Language Teaching

TBLT provides opportunities to experience spoken, reading, listening, and written language through meaningful class assignments that involve learners in practical and functional use of L2. As a consequence, TBLT promotes and stimulates the integration of skills through completing daily-life activities that improve students’ communicative competence because it offers learners the possibility of practicing the target language constantly. The students see learning as a way to explore active class exercises that bring up genuine communication in which they solve problems and show creativity.

The above-mentioned features of TBLT suggest that this methodology promotes actual language use that facilitates the integration of the abilities successfully. Nunan (1999) supported this idea when stating that TBLT requires listening, speaking, reading, and writing in the same exercise to complete the problem posed by the task. The use of this method in class usually brings real-life work that allows the practice of all the language abilities. This helps students to explore different communicative opportunities inside and outside the classroom, which benefit the practice of language by conducting tasks that are closely or related to the day-to-day life. Furthermore, Kurniasih (2011) highlighted that the objective of TBLT in English is to enhance the use of language as a means to focus on authentic learning. To achieve this objective, it is essential to promote realistic assignments that allow the students to meet their language needs. In order to make this possible, the four language skills should be integrated to increase learners’ competences and language acquisition.

Additionally, Richards and Rodgers (2001) highlighted that TBLT enhances the creation of learning tasks that suit the needs of the learners and help them master all skills successfully by providing different class exercises to complete their work. Ellis (2009) discussed some criteria that distinguish TBLT from regular teaching activities. He explained that this methodology focuses on the integration of language learning where students are expected to conduct creative activities, infer meaning from readings and oral messages, and communicate their ideas well. Finally, Li (1998) argued that TBLT facilitates language learning because learners are the center of the language process and, in that way, it promotes higher proficiency levels in all language skills.

Nunan (2005) also stated that TBLT is an approach that enables skills integration. It lets students understand, produce, manipulate, or interact in the classroom. This approach usually requires real tasks in which students have the main roles and use the four skills constantly. This helps learners to explore the possibilities of communicating orally and in writing and of comprehending texts and oral messages to complete the task. Willis (1996) and Carless (2007) acknowledged the importance of this approach because it emphasizes authenticity and communicative activities. For them, when TBLT is applied in class, learners assume active roles, and learning and reflections are constant.

Tasks in Language Learning

In English language education, tasks are viewed as important components to help develop proficiency and to facilitate the learning of a second or foreign language by increasing learners’ activity in the classroom. Nunan (2004) affirms that “tasks aim at providing occasions for learners to experiment and explore both spoken and written language through learning tasks that are designed to engage students in the authentic, practical, and functional use of language” (p. 41). In this vision, the role of a task is to stimulate a natural desire in learners to improve their language competence by challenging them to complete clear, purposeful, and real-world tasks which enhance the learning of grammar and other features as well as skills. Additionally, Richards et al. (as cited in Nunan, 2004) consider tasks as “an activity or action which is carried out as a result of a process to understand a language. For example, drawing a map, performing a command, buying tickets, paying the bills, and driving a car in a city” (p. 7). These types of tasks normally require the teacher to specify the requirements for successful completion, set the goals of the task, and provide different classroom practices that normally do not take place in an English class.

work undertaken for oneself or for others, freely or for some reward. Examples of a task include painting a fence, dressing a child, filling out a form, buying a pair of shoes, making an airline reservation, borrowing a library book, taking a driving test, typing a letter, weighing a patient, sorting letters, and so on. In this sense, Richards and Rodgers (2001) argue that “tasks are believed to foster a process of negotiation, modification, rephrasing, and experimentation that are at the heart of second language learning” (p. 228). Nunan (1999) points out that tasks activate and promote L2 learning through discussions, cooperation, and adjustment. In general, tasks allow learners to have more exposure in the language learning process by increasing rehearsal opportunities in which they prepare themselves to perform daily-life tasks that help them gain knowledge and experience in the target language.

Task Implementation

The process to implement TBLT in English classes has been highly discussed among various language theorists (e.g., Estaire & Zanon, 1994; Lee, 2000; Prabhu, 1987; Skehan, 1996; Willis, 1996). They highlight that there are three main steps to perform a task. First is the “pre-task stage” in which the teacher introduces the topic and provides the instructions such as the content, the objectives for each one of the steps within the task, and the way to present it. Referring to this stage, Willis and Prabu (as cited in Gatbonton & Gu, 1994) and Littlewood (2004) suggest that this stage creates an overview of what the students need to know to accomplish all the requirements of the assignment. Moreover, Skehan (1998) indicates that this phase is an overview or introduction about all the rules learners need to follow to complete the tasks correctly. Frequently, this period of task development is used to choose the topic of the task, plan how the students will present their work, or to consider the criteria to evaluate the results of the task and to determine actions to be taken regarding the performance of the students.

Ellis (2006) suggests the “during task” phase as the next step; he says that two basic things should be done. First of all, the analysis should be made of how the task is going to be developed, and secondly, the analysis of how the task will possibly be completed. Seedhouse (1999) states that it is necessary to guide the learners while they are doing the work, ask the students to show their progress on what they are reading, writing, what videos they are listening to, or check if they are listening to what has been provided to them, and as a final point, provide meaningful feedback to them. Numrich (1996) and Junker (1960) add that, at this level, learners must be open-minded to make changes to their presentations and reports. Crookes and Gass (1993) support this by saying that learners need to be flexible to revise, repeat, and reorganize their work once they receive support from the teacher. At this stage, the students negotiate among themselves to answer questions from the teacher and members of the group, review content, and reset those areas that need to be improved upon to submit their report.

The final moment would be the “post-task” phase. Lynch (2001) affirms that this moment involves the analysis and edition of the observations, opinions, and recommendations of the group and the teacher about the performance of learners in the task outcomes. In relation to this phase, Ellis (2014) considers that once the learners have conducted the task it is important to review their errors; this can be done by asking the whole group about the performance of their classmates, checking the teacher’s notes, or asking students to selfevaluate their presentations. Another important action to consider is to invite learners to improve the possible mistakes and to assign follow-up activities. In addition, Willis (1996) remarks that this phase encourages learners to automatize their production, make decisions on the results of the task, and evaluate which plan to follow to guarantee progress in the language. Finally, Rahimpour and Magsoudpour (2011) and Long (1985) indicated that this process is necessary for the learners because it is the opportunity to reflect upon what they have done.

Integration of Language Skills

Some current research on teaching English language associates the integration of the four skills with an improvement in the target language. Wallace, Stariha, and Walberg (2004) suggest that the integration of language skills provides natural situations in which listening, speaking, reading, and writing are developed in a single class to enhance English learning. As seen in this view, this way of teaching favors L2 learning because students are trained to use the language effectively, in different contexts, purposes, and cases. Nunan (1999) also supports this idea by saying that the integration of language skills is important to develop a genuine communicative competence and improve learners’ language proficiency by participating in linguistic and communicative activities that promote authentic language usage.

Furthermore, Hinkel (n.d.) points out that

the teaching of language skills can not be conducted through isolable and discrete structural elements (Corder, 1971, 1978; Kaplan, 1970; Stern, 1992). In reality, it is rare for language skills to be used in isolation; e.g., both speaking and listening comprehension are needed in a conversation and, in some contexts, reading or listening and making notes is likely to be almost as common as having a conversation. (p. 8)

This is shared by Ellis (2014) and Dickinson (2010) who state that integrating language skills facilitates the development of linguistic (including grammatical competence) and communicative abilities. Specifically, TBLT offers English classes an emphasis on the integration of the language skills by providing learners with more exploration and practice in each one of the skills.

Research Question

Based on the theoretical construct of TBLT that suggests that this methodology is fundamental to integrate language skills, this study aims at analyzing the impact of TBLT to integrate language skills in the first semester students in an EFL program at a public Colombian university. Therefore, the study seeks to answer the following research question: To what extent does TBLT promote the integration of the four language skills in the first semester students enrolled in an EFL program at a public Colombian university?

Method

I followed a case study research design due to the characteristic of the context and the specific population. The process involved planning, observing, acting, and reflecting on the data from a small number of participants. According to Baxter and Jack (2008), “a qualitative case study methodology provides the tools for researchers to study complex phenomena within their contexts” (p. 545). This model helped me to deeply analyze the phenomena that were affecting English learning in a particular site and try to seek solutions to the difficulties the students had regarding the integration of the language skills. Based on Yin’s (1984) definition, a case study is a process that examines and describes a particular case thoroughly with the objective of gathering an in-depth understanding of the problem under analysis.

Context of the Study

This study was conducted in an EFL program that is part of a public university in the southern region of Colombia. This institution is the only public university in the region and its students come mainly from hard-toaccess towns and villages in the region. Students at this university are diverse in terms of age, education, culture, and socioeconomic status. The academic emphasis of the university is on ecology and agronomy. The EFL program has about 500 students distributed among 14 groups. The curriculum of the program is divided into nine semesters where English and pedagogy are the emphases. The semesters are organized in levels according to the Common European Framework (Council of Europe, 2008). Consequently, the first and second semesters are Basic English I and II, respectively. The third, fourth, and fifth semesters are organized as Intermediate English I, II, and III correspondingly. The sixth, seventh, and eighth semesters are placed as advanced English I, II, and a conversational course, but in the ninth semester the learners do not study English because they have to choose their graduation option.

The EFL program is composed of 10 full-time teachers, 21 part-time teachers (I am included in this group of teachers), and a coordinator. They all have different academic labors in the development of the university term and they all work under semester contract. Additionally, the program has four tenured-track professors who have to teach vacation courses. The majority of the part-time teachers hold a bachelor degree in English as a foreign language teaching, eight of the 10 full-time teachers hold master degrees in different fields of language teaching and the remaining two are master candidates. Three of the four tenured-track professors hold master’s degrees and one is a master candidate. Finally, the program has a self-access center, an English lab, a specialized room with a TV set, a home theatre, and an audio recorder.

The research study took place in the Basic English Course I. This group was divided into two groups of 25 students each. For the study, only group A was selected; this course had 25 learners and six of them gave consent to participate in the study. The participants were young learners; the age range was from 16 to 22 years. They had an A2 level in English, based on the parameters of the Common European Framework (Council of Europe, 2008). They were chosen as participants because they all had the same challenges and they were in the same semester and group.

Data Collection Instruments

Following Baxter and Jack (2008) qualitative case studies give researchers the opportunity to examine a problem through the use of different data collection tools. A series of six interviews and the same number of observations were conducted to provide validity to the research study.

Observations

According to Jacobson, Pruitt-Chapin, and Rugeley (2009), the use of observation provides direct access to the phenomenon under consideration by proving accurate and complete information from the behavior of the participants. Based on the evidence that observations are fundamental to conduct a research study, the participants were observed as a group and individually along a semester. During the observations, I concentrated on the behavior, performance, and interaction of the students while they developed the tasks. An observation checklist was used to guide the observation process. Referring to this, Belisle (1999) and Wajnryb (1992) indicate the need to follow an observation checklist in qualitative research because it facilitates and assists the observation.

Interviews

According to Laforest (2009), semi-structured interviews are used to gather qualitative information, help to identify needs and priorities, and monitor students’ changes. In my case, they also facilitated discussion and analysis of the data. I used six semistructured interviews to learn the students’ background, to examine the impact of the methodology proposed on solving the difficulty under consideration, and to confirm and triangulate the information from the observations. Each interview lasted 40 minutes approximately and the students were informed that their answers would be used only for the purpose of the study. Sometimes, the students were asked to elaborate further when their answers were not sufficiently clear. All the interviews were audio recorded and transcribed for later analysis. The interviews were conducted at the beginning, during the implementation, and after applying TBLT in class.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

In order to analyze the data, I followed a constant comparison strategy to examine the information of the problem under study. Based on Creswell (2007), the constant comparison strategy is a series of procedures that help researchers to analyze and think about social realities. I followed a systematic plan of action in which I first transcribed the observations and the interviews. Secondly, I read the information several times to identify the recurring themes and recorded the data on the margins. Then, data were segmented with repetitive words and voices from the participants. Data are shown in the case study session that defines the participants in the research study.

Procedure

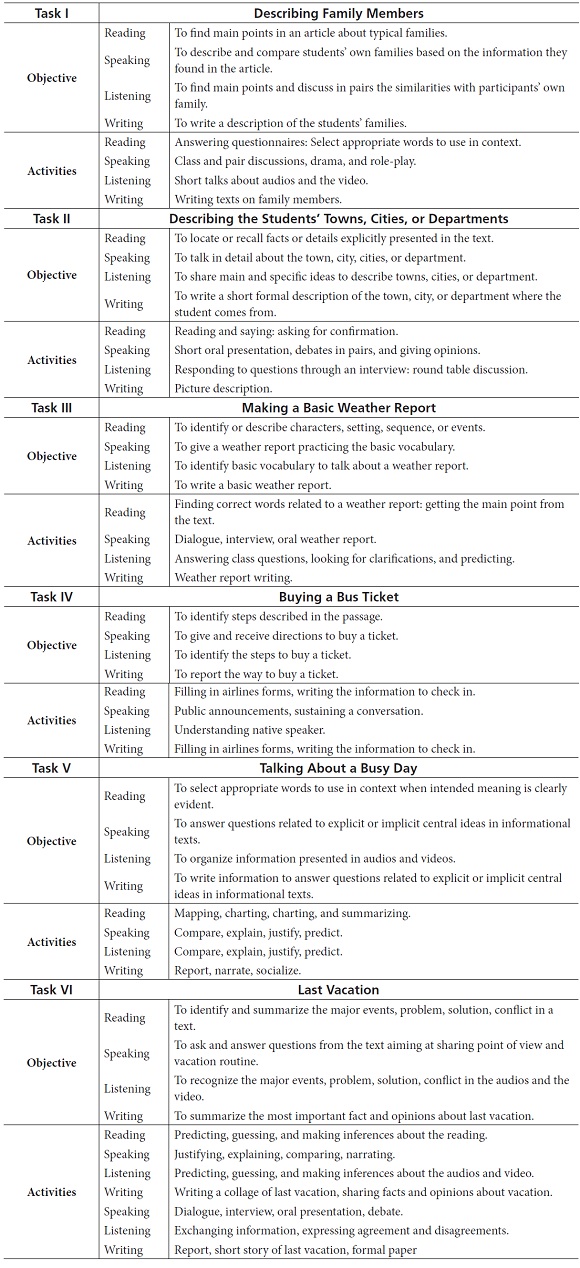

To achieve the research objectives and answer the question of the study I designed and implemented six tasks that included assignments in all skills. This process lasted 20 hours spread across the semester and I took into account the concepts and steps discussed in the literature review. Prior to the application of the tasks, I explained to the participants the methodology to be applied as well as the activities that were going to be completed, so the learners knew in advanced the procedures to be used and the estimated time available for them to fulfill every task. Finally, I shared the decision to work in pairs and I said to them that the topics to be developed were all included in the course program (see Appendix for a description of each of the tasks).

The first stage of the development of the tasks started with the “pre-task phase” in which I illustrated for the students the chronogram-requirements of the task, showed them the topics, set the goals and procedures of the task, and provided additional instructions to develop the activities. Similarly, I asked the students to form pairs, discuss the outcomes and the what, how, when, and where they were going to submit the product for every skill. As soon as the participants understood the goals and introductions, I gave them an article, a video, and some audios about the topic of the task (describing family members). Then, they started by reading the article, watching videos, and listening to the audios. At this stage, the participants listed some characteristics of typical families, generated ideas in pairs, provided answers to the reading and listening questionnaires, and started a short conversation between themselves about their presentation.

Then in the second phase “during task,” while the students were working, I answered and asked questions, checked their work, and provided recommendations for them to prepare the reports on each one of the skills. After they had identified the main characteristics on families from the article, video, and audios, they compared their families to those mentioned in the material I had previously given to them. Subsequently, they had a pair-work discussion about the topic and showed the draft of the description they had already made. Next, I gave them some suggestions based on what I checked from the conversation and read from the initial reports and questionnaires. Once the participants received my comments, they made some changes to their responses and reorganized their presentations without complaining, but the remaining three students asked for more detailed recommendations. At this stage, the students were familiar with working in every skill because they presented reading, listening, speaking, and writing reports.

In the final phase, “post-task,” the students firstly submitted the final record from the audios, the video, and the article and, at the same time, delivered the written description of their families and did an oral presentation about the same topic. After their presentation, I gave them the opportunity to self-evaluate and then suggested that other pairs evaluate their classmates’ performance: this was done by asking questions on how the pairs had performed on the oral presentation. They identified the areas where they needed to work on and self-corrected some of the difficulties they had. Then, I explained the topics that I thought needed major improvements, gave advice on how to improve them, and recommended a follow-up task. At this stage of the process, the participants were able to integrate all language skills in the class activities through a step-by-step process that enabled them to present meaningful outcomes in the four skills.

Findings and Discussion

In this section I describe and discuss the findings of the study. First of all, I show the participants’ perception about TBLT to integrate the four language skills. Later, I present the participants’ view of integrated skills in EFL learning, and finally, I point out the participants’ motivation during the development of the task.

Learners’ Perception About TBLT to Integrate the Four Language Skills

The general findings of this research demonstrated that all the participants see TBLT as a way to encourage the use and integration of the four language skills in their EFL classes. They considered that this methodology could be helpful to incorporate the abilities through performing tasks that included a variety of exercises to help them to develop their capabilities in each of the abilities.

Nicol1 expressed that “they preferred TBLT rather than other ways of language learning because this method offered the opportunity to increase their expertise in all the abilities and not only on one or two” (Interview 2). Andres said that the implementation of an everyday life task such as “describing family members” fostered the integration of the four language skills in an optimistic way (Interview 3). In the same interview, Yasney stated: “Classes are better now because we all practice the four skills at the same time.” These participants had this perception about TBLT because this approach facilitated the development of different class exercises that covered specific assignments in reading, writing, listening, and speaking. This familiarized the participants with integrated classroom tasks and provided more interaction, helping students to become better English learners. This is connected to Cuesta (1995) who affirmed that TBLT assisted learners to develop their skills in the L2.

Linked to the previous benefit of TBLT in EFL, some participants mentioned that the use of this methodology integrated the skills because it was an interesting way to promote the successful development of authentic class activities, in which they were asked to finalize real-world tasks that increased significant practice such as discussions, skimming and scanning articles, and written reports.

Eunice stated that “every task was the possibility to advance in all my language skills from contextualized exercises that helped me to learn” (Interview 3). Ana supported Eunice by saying that “task[s] involved reading, writing, listening, and speaking assignments that were natural and helpful to learn English” (Interview 4). In Interview 6, Carlos said: “I feel the need to speak English in the classes and to integrate reading, speaking, listening, and writing in a single lesson because I think it is one of my major weaknesses to be fulfilled along with the academic year.” Carlos further affirmed that “the assignments helped them to understand that skills integration provided them with realistic language learning.” In Observations 4, 5, and 6, Carlos and Nicol showed that it was not a problem for them to integrate skills in a class any longer. The participants shared these perceptions because the majority of activities they received were related to contextualized exercises and they had the opportunity to carry out creative tasks where the integration of language skills was kept in mind and demanded active personal involvements to learn how to improve their skills in the target language easily and naturally.

The students also highlighted that the TBLT methodology facilitated the researcher to keep a balance among all four skills. As a consequence, learning how to write, understand written messages, understand oral language, and communicate thoughts were taught simultaneously. In Observations 5 and 6, Nicol, Eunice, and Ana seemed to prefer TBLT rather than other ways of language learning because this method offered the opportunity to increase their expertise in all the abilities and not only in one or two. This finding indicates that this approach caught their attention and promoted rehearsal opportunities by doing different exercises that were based on their interest and covered all the skills. This position is also shared by Andres who stated that “the implementation of tasks encouraged me to work on my weaknesses in the language, especially the unpleasant feelings to read, write, and listen” (Interview 5-6). These findings are supported by prior research targeting the same situation. Hu (2013) concluded that the TBLT method brought real life purposes to the class in which learners are expected to prepare and practice the language constantly.

The participants equally suggested that TBLT created more diverse and inclusive exposures in the target language practice. They had more opportunities to rehearse and interact with their classmates and the teacher-researcher by asking and answering questions from the articles and holding conversations with the classmates about the task. In Interview 5, Yasney expressed that she “liked to work with TBLT in class because [she] prepared well by practicing with [her] classmates.” In Observations 4 and 5, it was evident to see this and other learners (5) participating in all the exercises. In relation to this, Xiongyong and Samuel (2011) affirmed that TBLT is seen by students as a great methodology to enhance language practice opportunities. These results revealed that TBLT integrated and opened students’ possibilities of being part of the class through constant practice.

Additionally, some participants claimed that this approach facilitated the acquisition of L2 through making decisions, learning by doing, and facing different challenges that tasks demand from the students and the teacher. In an informal talk after Observation 5, Yasney supported this claim by saying “the implementation of tasks-based language teaching increased the opportunities to learn English and raised confidence to prepare high quality assignments that were based on classmates’ life.” For them, TBLT fostered a longlife learning process. It means that this methodology promoted exploration, negotiation, and cooperation among the teacher and students to find solutions to problems and complete the task. This is supported by Barnard and Viet (2010) who concluded that TBLT helped to increase cooperation and negotiation among the participants.

To sum up, TBLT may also be a good way to integrate skills by creating a framework that allows the practice of suitable class activities in which learners have to reach specific class aims for every skill. Carlos affirmed that “the assignments helped them to understand that skills integration provided them with realistic language learning” (Interview 5). Additionally, Andrea expressed that she improved her language competences in part because TBLT integrated the language skills and she practiced the language. For these participants the use of task played an important role to learn the target language easily and naturally, and they improved their skills in the language.

Participants’ View of Integrated Skills in EFL Class

With respect to the integration of language skills in EFL classes, there were two positions. First, at the beginning the students were not familiar with the methodology of integrating language skills in class. Then, their perception was that the integration might be a great way to learn a language, but they were not totally sure about the benefits of integrating the skills in classes because they said that it demanded more work and it would be better to master one skill and then the rest. However, this position changed during the development of the tasks in which it was observable that the students did a lot of exercises to finalize the work successfully. In Interview 5, Yasney stated that “the integration of language skills is a useful and a successful mechanism to enhance the students’ English Language.” This position was shared by Andres, who said that “the integration of language skills resulted in a very useful way to keep a balance in the four language skills.” Andres also expressed that “the integration is fundamental to learn the language as it is used in the real life.” In part, the participants had this perception because at the end of the study they got used to performance class work that had specific assignments for every skill.

Despite the fact that their performance in each skill presented some error, the process to complete the task and to learn the language notions and functions was remarkable. The students were committed to not only present a final product of the task, but also to learn from their classmates’ suggestions, share their results of their tasks, and show that they were able to make significant improvement in their learning progress.

Participants’ Motivation During the Development of the Task

Apart from integrating language skills, TBLT helped the participants to be motivated, it raised their selfesteem, and enabled them to praise their own and others’ work. They were motivated by the structure of the tasks (stages), the goals of each phase and the clear purposes, the teacher-researcher willingness to correct meaningfully, and the kind of activities they developed. Nicol said that “the research-teacher and the organization of the task encouraged her to feel good in the class” (Interview 4). Similarly, Yasney expressed that “the steps of the assignments and the teacher made [her] be willing to take part in the class development easily” (Interview 5). Andres also manifested that working with TBLT motivated him to be a better English learner. The positive attitude of these participants about the implementation of tasks in class was in part due to their high performance, the meaningful feedback and positive attitude, and disposition of the teacher-researcher. It means that in order to foster learners’ motivation, it is necessary to plan the class activities well and provide them with correct feedback.

With respect to the perspective of the participants about the role of TBLT to motivate them, they claimed this approach provided them with opportunities to be engaged in the class, to practice and negotiate as to improve their speaking, listening, and writing skills in a comfortable, communicative, and collaborative atmosphere, where they learned to work cooperatively, respect and value other classmates’ points of view. In Observations 4, 5, and 6, it was common to see the participants sharing ideas, clapping their hands to congratulate their classmates for their performance and helping them to find the correct word to express an idea. It was also noteworthy to observe the participants working in groups, listening to other pairs attentively, and paying sincere compliments or giving positive feedback. These findings are shared with Chuan (2010), who concluded in his study that TBLT helped students to be self-confident to practice the language without anxiety. In fact, during the development of tasks learners were encouraged to trust in their capacities and felt confident to take an active role in class because the classes were closely related to their background. Nicol declared in Interview 6 that:

The use of tasks helped me to be a better English student that was able to express her feelings and thoughts in a friendly environment, in which learning, negotiation, discussion was possible. I said I improved a lot in the subject because I felt confident and accepted mistakes as a learning strategy.

This confirmed the idea that TBLT may also be a good way to foster motivation and language learning at the same time due to the fact that learners are led to have social discussions, group interaction, and build social community networks in the class. Nicol stated that “TBLT served as a potential strategy that motivated students to be willing to participate in class discussions” (Interview 5). This was evidenced in the development of the implementation in that each participant wanted to show the results of their tasks in the classroom. In this respect, Andres stated that “the implementation of these assignments brought more complex assignments and placed more responsibility on the students” (Interview 6). This is connected to Hyde (2013) who argues that TBLT is an ideal way to improve motivation and selfefficacy. This may have let participants to perceive TBLT as a way to reinforce, share decision making, and praise their work.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that TBLT is a meaningful approach to integrate language skills in an EFL program. The participants performed class assignments that helped them to develop tasks which included continuing exercises in receptive and productive skills and have more time to practice doing tasks that required the integration of language skills in a lesson through the use of contextualized and meaningful activities that support natural language acquisition. Linked to this benefit, the implementation of these assignments had a positive impact to improve students’ communicative competences, as can be noted by the students’ responses. These tasks increased the students’ experience in the language by providing them with more opportunities to rehearse the language meaningfully. They negotiated among themselves, showed their points of view about the class development, and shared the results with their classmates orally and in writing. Also, they searched information, read articles to get main ideas, and supported their reports.

Finally, the implementation of TBLT was an effective way to develop learners’ self-awareness and class atmosphere where the teacher and the students participated in the lessons. The students became aware of the importance of being responsible in the class activities and took main roles in the learning process by creating meaningful tasks that facilitated the acquisition of new vocabulary, the implementation of real activities that augmented learning, and the change of misconceptions about how to learn each one of the skills.

Recommendations

With respect to the use of TBLT to facilitate skills integration in an EFL context, the results of this study suggest English teachers need to bear in mind that the use of this methodology is meaningful because it promotes language learning naturally and this motivates learners to be involved in the class activities. However, I highly recommend creating clear purposes and discussing the topics of the task with the students beforehand in order to increase practice. When the students are involved in decision making, they participate and perform the tasks easily and feel important in the class. Based on the findings of the study, I also suggest providing learners with positive feedback, reminding them how important it is to reach the goals of the task, assign clear assignments for every skill, check the result of the tasks, and finally, assign follow-up activities if necessary. These recommendations are necessary to increment the possibility of advancing in the task and consequently of improving students’ learning process. However, this study suggests that future review and research need to be conducted to broaden the theoretical framework of TBLT as a skills integration facilitator.

Further analysis of the impact of TBLT to integrate language skills in beginners constitutes another new good field of inquiry. It would be interesting to know to what extent students of basic English become independent learners through the implementation of this methodology. Also, it would be necessary to explore other approaches to integrate language skills and compare them with TBLT to determine the advantages and disadvantages of each one of them for learners of basic English.

1The names used here are pseudonyms.

References

Barnard, R., & Viet, N. G. (2010). Task-based language teaching (TBLT): A Vietnamese case study using narrative frames to elicit teachers’ beliefs. Language Education in Asia, 1(1), 77-86. https://doi.org/10.5746/LEiA/10/V1/A07/Barnard_Nguyen.

Baturay, M. H., & Akar, N. (2007). A new perspective for the integration of skills to reading. Dil Dergisi, 136, 16-27.

Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 544-559.

Belisle, T. (1999). Peer coaching: Partnership for professional practitioners. The ACIE Newsletter, 2(3), 3-5.

Carless, D. (2007). Learning-oriented assessment: Conceptual bases and practical implications. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 44(1), 57-66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703290601081332.

Chuan, Y.-Y. (2010). Implementing task-based approach to teach and assess oral proficiency in the college EFL classroom. Taipei, TW: Cosmos Culture.

Council of Europe (2008). Common European framework of references for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Crookes, G., & Gass, S. M. (Eds.). (1993). Tasks in pedagogical context: Integrating theory and practice. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Cuesta, M. R. (1995). A task-based approach to language teaching: The case for task-based grammar activities. Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses, 8, 91-100.

Dickinson, P. (2010). Implementing TBLT in a Japanese EFL context: An investigation into language methodology (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

Ellis, R. (2006). The methodology of task-based teaching. Kansai Magazine, 5(2), 1-25 Retrieved from https://www.kansai-u.ac.jp/fl/publication/pdf_education/04/5rodellis.pdf.

Ellis, R. (2009). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R. (2014). Taking the critics to task: The case for taskbased teaching. Proceedings of the Sixth CLS International Conference clasic 2014, Singapore, 103-117.

Estaire, S. & Zanon, J. (1994). Planning classwork: A task based approach. Oxford, UK: Heinemann.

Freeman, D. (1996). Doing teacher research: From inquiry to understanding. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Gatbonton, E., & Gu, G. (1994). Preparing and implementing a task-based esl curriculum in an EFL setting: Implications for theory and practice. TESL Canada Journal, 11(2), 9-29.

Hinkel, E. (n.d.). Integrating the four skills: Current and historical perspectives. Retrieved from http://www.elihinkel.org/downloads/Integrating_the_four_skills.pdf.

Hu, R. (2013). Task-based language teaching: Responses from Chinese teachers of English. The Electronic Journal for English as a Second Language, 16(4), 1-21.

Hyde, C. (2013). Task-based language teaching in the business English classroom (Master’s thesis). University of Wisconsin, USA.

Izadpanah, S. (2010). A study on task-based language teaching: From theory to practice. Journal of US-China Foreign Language, 8(3), 47-56. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.463.7099&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Jacobson, M., Pruitt-Chapin, K., & Rugeley, C. (2009). Toward reconstructing poverty knowledge: Addressing food insecurity through grassroots research design and implementation. Journal of Poverty, 13(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875540802623260.

Junker, B. H. (1960). Field work: An introduction to the social sciences. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kurniasih, E. (2011). Teaching the four language skills in primary EFL classroom: Some considerations. Journal of English Teaching, 5(2), 24-35.

Laforest, J. (2009). Safety diagnosis tool kit for local communities: Guide to organizing semi-structured interviews with key informants. Québec, CA: Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec.

Lee, J. F. (2000). Tasks and communicating in language classrooms. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Li, M.-S. (1998). English literature teaching in China: Flowers and thorns. The Weaver: A Forum for New Ideas in Education, 2.

Littlewood, W. (2004). The task-based approach: Some questions and suggestions. ELT Journal, 58(4), 319-326. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/58.4.319.

Long, M. H. (1985). A role for instruction in second language acquisition: Task-based language training. In K. Hylstenstam & M. Pienemann (Eds.), Modelling and assessing second language acquisition (pp. 77-99). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Lynch, T. (2001). Seeing what they meant: Transcribing as a route to noticing. ELT Journal, 55(2), 124-132. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.2.124.

Numrich, C. (1996). On becoming a language teacher: Insights from diary studies. TESOL Quarterly, 30(1), 131-153. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587610.

Nunan, D. (1999). Language teaching methodology: A textbook for teachers. Hemel Hempstead, UK: Prentice Hall.

Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667336.

Nunan, D. (2005). Classroom research. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 225-240). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Prabhu, N. S. (1987). Second language pedagogy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Rahimpour, M., & Magsoudpour, M. (2011). Teacher-students’ interactions in task-based vs form-focused instruction. World Journal of Education, 1(1), 171-178. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v1n1p171.

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2001). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667305.

Seedhouse, P. (1999). Task-based interaction. ELT Journal, 53(3), 149-156. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/53.3.149.

Skehan, P. (1996). A framework for the implementation of task based instruction. Applied Linguistic, 17(1), 38-62. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/17.1.38.

Skehan, P. (1998). Task-based instruction. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 18, 268-286. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190500003585.

Wajnryb, R. (1992). Classroom observation tasks: A resource book for language teachers and trainers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wallace, T., Stariha, W. E., & Walberg, H. J. (2004). Teaching speaking, listening and writing. Brussels, BE: International Academy of Education.

Willis, J. (1996). A framework for task-based learning. London, UK: Longman.

Xiongyong, C., & Samuel, M. (2011). Perceptions and implementation of task-based language teaching among secondary school EFL teachers in China. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(24), 292-302.

Yin, R. K. (1984). Case study research: Design and methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

About the Author

Eulices Córdoba Zúñiga is an EFL teacher with diverse teaching experience in universities and institutes. Since 2011, he has been working for Universidad de la Amazonia (Colombia). He holds a Master’s Degree in English Didactics. His research interests include English as a foreign language methodology, didactics, and teachers’ professional development.

Appendix: Description of the Tasks

References

Barnard, R., & Viet, N. G. (2010). Task-based language teaching (TBLT): A Vietnamese case study using narrative frames to elicit teachers’ beliefs. Language Education in Asia, 1(1), 77-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.5746/LEiA/10/V1/A07/Barnard_Nguyen.

Baturay, M. H., & Akar, N. (2007). A new perspective for the integration of skills to reading. Dil Dergisi, 136, 16-27.

Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 544-559.

Belisle, T. (1999). Peer coaching: Partnership for professional practitioners. The ACIE Newsletter, 2(3), 3-5.

Carless, D. (2007). Learning-oriented assessment: Conceptual bases and practical implications. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 44(1), 57-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14703290601081332.

Chuan, Y.-Y. (2010). Implementing task-based approach to teach and assess oral proficiency in the college EFL classroom. Taipei, TW: Cosmos Culture.

Council of Europe (2008). Common European framework of references for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Crookes, G., & Gass, S. M. (Eds.). (1993). Tasks in pedagogical context: Integrating theory and practice. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Cuesta, M. R. (1995). A task-based approach to language teaching: The case for task-based grammar activities. Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses, 8, 91-100.

Dickinson, P. (2010). Implementing TBLT in a Japanese EFL context: An investigation into language methodology (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

Ellis, R. (2006). The methodology of task-based teaching. Kansai Magazine, 5(2), 1-25 Retrieved from https://www.kansai-u.ac.jp/fl/publication/pdf_education/04/5rodellis.pdf.

Ellis, R. (2009). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R. (2014). Taking the critics to task: The case for taskbased teaching. Proceedings of the Sixth CLS International Conference clasic 2014, Singapore, 103-117.

Estaire, S. & Zanon, J. (1994). Planning classwork: A task based approach. Oxford, UK: Heinemann.

Freeman, D. (1996). Doing teacher research: From inquiry to understanding. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Gatbonton, E., & Gu, G. (1994). Preparing and implementing a task-based esl curriculum in an EFL setting: Implications for theory and practice. TESL Canada Journal, 11(2), 9-29.

Hinkel, E. (n.d.). Integrating the four skills: Current and historical perspectives. Retrieved from http://www.elihinkel.org/downloads/Integrating_the_four_skills.pdf.

Hu, R. (2013). Task-based language teaching: Responses from Chinese teachers of English. The Electronic Journal for English as a Second Language, 16(4), 1-21.

Hyde, C. (2013). Task-based language teaching in the business English classroom (Master’s thesis). University of Wisconsin, USA.

Izadpanah, S. (2010). A study on task-based language teaching: From theory to practice. Journal of US-China Foreign Language, 8(3), 47-56. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.463.7099&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Jacobson, M., Pruitt-Chapin, K., & Rugeley, C. (2009). Toward reconstructing poverty knowledge: Addressing food insecurity through grassroots research design and implementation. Journal of Poverty, 13(1), 1-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10875540802623260.

Junker, B. H. (1960). Field work: An introduction to the social sciences. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kurniasih, E. (2011). Teaching the four language skills in primary EFL classroom: Some considerations. Journal of English Teaching, 5(2), 24-35.

Laforest, J. (2009). Safety diagnosis tool kit for local communities: Guide to organizing semi-structured interviews with key informants. Québec, CA: Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec.

Lee, J. F. (2000). Tasks and communicating in language classrooms. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Li, M.-S. (1998). English literature teaching in China: Flowers and thorns. The Weaver: A Forum for New Ideas in Education, 2.

Littlewood, W. (2004). The task-based approach: Some questions and suggestions. ELT Journal, 58(4), 319-326. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/elt/58.4.319.

Long, M. H. (1985). A role for instruction in second language acquisition: Task-based language training. In K. Hylstenstam & M. Pienemann (Eds.), Modelling and assessing second language acquisition (pp. 77-99). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Lynch, T. (2001). Seeing what they meant: Transcribing as a route to noticing. ELT Journal, 55(2), 124-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.2.124.

Numrich, C. (1996). On becoming a language teacher: Insights from diary studies. TESOL Quarterly, 30(1), 131-153. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3587610.

Nunan, D. (1999). Language teaching methodology: A textbook for teachers. Hemel Hempstead, UK: Prentice Hall.

Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667336.

Nunan, D. (2005). Classroom research. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 225-240). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Prabhu, N. S. (1987). Second language pedagogy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Rahimpour, M., & Magsoudpour, M. (2011). Teacher-students’ interactions in task-based vs form-focused instruction. World Journal of Education, 1(1), 171-178. http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/wje.v1n1p171.

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2001). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667305.

Seedhouse, P. (1999). Task-based interaction. ELT Journal, 53(3), 149-156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/elt/53.3.149.

Skehan, P. (1996). A framework for the implementation of task based instruction. Applied Linguistic, 17(1), 38-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/applin/17.1.38.

Skehan, P. (1998). Task-based instruction. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 18, 268-286. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0267190500003585.

Wajnryb, R. (1992). Classroom observation tasks: A resource book for language teachers and trainers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wallace, T., Stariha, W. E., & Walberg, H. J. (2004). Teaching speaking, listening and writing. Brussels, BE: International Academy of Education.

Willis, J. (1996). A framework for task-based learning. London, UK: Longman.

Xiongyong, C., & Samuel, M. (2011). Perceptions and implementation of task-based language teaching among secondary school EFL teachers in China. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(24), 292-302.

Yin, R. K. (1984). Case study research: Design and methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Filip Pultar. (2022). Výzkum v didaktice cizích jazyků V. , p.37. https://doi.org/10.5817/CZ.MUNI.P280-0310-2022-2.

2. Susana Adjei-Mensah, Naomi Y. Boakye, Andries Masenge. (2023). Improving the reading proficiency of mature students through a task-based language teaching approach. Reading & Writing, 14(1) https://doi.org/10.4102/rw.v14i1.406.

3. Eulices Córdoba Zúñiga, Emerson Rangel Gutiérrez. (2018). Promoting Listening Fluency in Pre-Intermediate EFL Learners Through Meaningful Oral Tasks. Profile: Issues in Teachers´ Professional Development, 20(2), p.161. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.62938.

4. Gökçen GÖÇEN. (2020). Türkçenin yabancı dil olarak öğretiminde yöntem. RumeliDE Dil ve Edebiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi, (18), p.23. https://doi.org/10.29000/rumelide.705499.

5. Angela Patricia Velásquez Hoyos. (2023). English teachers’ perceptions of Task-Based Instruction in Risaralda, Colombia. . Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 25(1), p.71. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.17878.

6. Claudia Camila Coronado-Rodríguez, Luisa Fernanda Aguilar-Peña, María Fernanda Jaime-Osorio. (2022). A Task-based Teacher Development Program in a Rural Public School in Colombia. HOW, 29(1), p.64. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.29.1.640.

7. Fabio Adrian Torres-Rodriguez, Liliana Martínez-Granada. (2002). Speaking in Worlds of Adventure: Tabletop Roleplaying Games within the EFL Classroom. HOW, 29(1), p.105. https://doi.org/10.19183//how.29.1.653.

8. Cinthia M. Chong. (2022). Integrating Reading Aloud, Writing, and Assessment Through Voice Recording With EFL Learning. STEM Journal, 23(4), p.47. https://doi.org/10.16875/stem.2022.23.4.47.

9. Eulices Córdoba Zúñiga, Isabel Cristina Zuleta Vásquez, Uriel Moreno Moreno. (2021). Pair Research Tasks: Promoting Educational Research with Pre-Service Teachers. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 23(2), p.196. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.16347.

10. Elena V. Borzova, Maria A. Shemanaeva. (2020). MULTIFUNCTIONALITY IN UNIVERSITY FOREIGN LANGUAGE EDUCATION: FROM AIMS TO TECHNIQUES. Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 8(4), p.1429. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2020.84132.

11. Addisu B. Shago, Elias W. Bushisso, Taye G. M. Olamo. (2024). Beliefs of EFL University Instructors about Teaching Listening in Integration with Speaking, Ethiopia. Sage Open, 14(4) https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241296581.

12. Carolina Herrera Carvajal, Katherin Pérez Rojas. (2024). Understanding task-based learning and its implementation: a Public University case. Revista Perspectivas, 9(2), p.73. https://doi.org/10.22463/25909215.4028.

13. Ece DİLBER, Şevki KÖMÜR. (2022). The Role of Two-way Information-Gap Tasks on Students’ Motivation in Speaking Lessons in an ESP Context. Language and Technology, 4(1), p.2. https://doi.org/10.55078/lantec.1118527.

14. Susana Adjei-Mensah. (2024). Exploring Mature Students’ Perspectives on Task-Based Language Teaching in a Ghanaian Private University: A Qualitative Study. Pan-African Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 5(2), p.38. https://doi.org/10.56893/pajes2024v05i02.04.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.