Effects of pyrolysis atmosphere on the porous structure and reactivity of chars from middle and high rank coals

Efectos de la atmósfera de pirólisis sobre la estructura porosa y la reactividad de los carbonizados formados desde carbones de alto y mediano rango

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/ing.investig.v38n1.64516Keywords:

Slow pyrolysis, Pore size distribution, large coal particles, Oxy-combustion, Reactivity (en)Pirólisis lenta, distribución de tamaño de poro, grandes partículas de carbón, Oxy-combustión, reactividad (es)

Se estudió la influencia de una atmósfera basada en CO2 o N2 sobre la estructura porosa y la microestructura de carbonizados de carbón obtenidos de la pirólisis lenta no isotérmica desde temperatura ambiente hasta 900 °C de dos carbones de diferente rango (Semi-Antracita (SA) y Bituminosos Alto en Volátiles tipo C (BAVC)), y de diferentes distribuciones de tamaño de partícula. Para todos los carbonizados se realizó la caracterización fisicoquímica (Análisis ultimo y próximo), la caracterización morfológica y estructural por combinación de técnicas como espectroscopia Rama, Microscopia electrónica de barrido por emisión de campo (FE-SEM), área superficial (BET - Brunauer-Emmett-Teller) y volumen y diámetro de microporos por mediciones de adsorción en CO2 (Horvath-Kawazoe (HK) method). Se encontró que los parámetros cinéticos, las propiedades fisicoquímicas y la reactividad de los carbonizados de carbón son diferentes dependiendo de la atmósfera de pirólisis. También se determinó que para el carbonizado de carbón de SA, con un tamaño de partícula mayor de 0,7mm, la superficie BET aumenta cuando la atmósfera se enriquece en CO2. Este efecto parece ser promovido por la interacción de diferentes procesos como las reacciones secundarias intrapartícula (ablandamiento, nucleación y coalescencia de burbujas, entrecruzamiento, entre otros), diferencias en la difusividad térmica de N2 y CO2, y los efectos reactivos de este último. Además, los ensayos de reactividad oxidativa de los sólidos mostraron que el carbonizado formado en una atmósfera de CO2 es más reactivo que el formado en N2. Con los resultados del análisis de Raman y los parámetros cinéticos cuantificados, se concluyó que la atmósfera de reacción determinó el grado de ordenación alcanzado por la estructura carbonosa y que las propiedades termo-difusivas de la atmósfera de reacción promovieron diferencias estructurales en el carbonizado, incluso a bajas velocidades de calentamiento.

Effects of pyrolysis atmosphere on the porous structure and reactivity of chars from middle and high rank coals

Efectos de la atmósfera de pirólisis sobre la estructura porosa

y la reactividad de los carbonizados formados

desde carbones de alto y mediano rango

Carlos F. Valdés 1, Yuli Betancur 2, Diana López 3, Carlos A. Gómez 4, and Farid Chejne 5

1 Chemical Engineer, M.Sc., Ph.D. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Minas, Escuela de Procesos y Energía, TAYEA Group, Carrera 80 No. 65-223, Medellín, Antioquia, Colombia. Email: cfvaldes@unal.edu.co

2 Chemist Ph.D. Química de Recursos Energéticos y Medio Ambiente, Instituto de Química, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Antioquia, UdeA - Colombia, Calle 70 No. 52-21, Medellín, Antioquia, Colombia Email: ybetancurguerrero@gmail.com

3 Chemist, Ph.D. Química de Recursos Energéticos y Medio Ambiente, Instituto de Química, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Antioquia, UdeA - Colombia, Calle 70 No. 52-21, Medellín, Antioquia, Colombia Email: diana.lopez@udea.edu.co

4 Chemical Engineer, M.Sc., Ph.D. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Minas, Escuela de Procesos y Energía, TAYEA Group, Carrera 80 No. 65-223, Medellín, Antioquia, Colombia. Email: cagomez0@unal.edu.co

5 Mechanical Engineer, Physics, Ph.D. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Minas, Escuela de Procesos y Energía, TAYEA Group, Carrera 80 No. 65-223, Medellín (Colombia). Email: fchejne@unal.edu.co

How to cite: Valdés, C. F., Betancur, Y., López, D., Gómez, C. A., and Chejne, F. (2018). Effects of pyrolysis atmosphere on the porous structure and reactivity of chars from middle and high rank coals. Ingeniería e Investigación, 38(1), 31-45. DOI: 10.15446/ ing.investig.v38n1.64516

ABSTRACT

The influence of a CO2 or N2-based atmosphere on the porous structure and microstructure of the chars obtained from the non-isothermal slow devolatilization (10 °C/min), from room temperature to 900 °C, of two coals of different rank (Semi-Anthracite (SA) and High Volatile Bituminous type C (HVBC)) and different particle size distribution was studied. Physicochemical characterization (ultimate and proximate analysis), structural and morphological characterization by Raman spectroscopy, FE-SEM, BET surface area, and volume and diameter microporous by CO2 adsorption measurements were carried out for all the chars. It was found that the kinetic parameters, the physicochemical properties, and reactivity of the chars are different, depending on the pyrolysis atmosphere. It was also determined that for the char from SA coal with particle size greater than 0.7 mm, the BET surface area increases when the atmosphere is enriched with CO2. This effect appears to be promoted by the interaction of different processes such as intraparticle side reactions (softening, nucleation and coalescence of bubbles, crosslinking, among others), differences in the thermal diffusivity of N2 and CO2, and the reactive effects of the latter. Additionally, tests of oxidative reactivity of chars showed that the char formed in a CO2 atmosphere is more reactive than that formed in N2. With the results of Raman analysis and kinetic parameters quantified, it was concluded that the reaction atmosphere determined the degree of ordering achieved by the char structure and that the thermo-diffusive properties of the reaction atmosphere promoted structural differences in the char even at low heating rates.

Keywords: Slow pyrolysis, Pore size distribution, large coal particles, Oxy-combustion, reactivity.

RESUMEN

Se estudió la influencia de una atmósfera basada en CO2 o N2 sobre la estructura porosa y la microestructura de carbonizados de carbón obtenidos de la pirólisis lenta no isotérmica desde temperatura ambiente hasta 900 °C de dos carbones de diferente rango (Semi-Antracita (SA) y Bituminosos Alto en Volátiles tipo C (BAVC)), y de diferentes distribuciones de tamaño de partícula. Para todos los carbonizados se realizó la caracterización fisicoquímica (Análisis ultimo y próximo), la caracterización morfológica y estructural por combinación de técnicas como espectroscopia Rama, Microscopia electrónica de barrido por emisión de campo (FE-SEM), área superficial (BET - Brunauer-Emmett-Teller) y volumen y diámetro de microporos por mediciones de adsorción en CO2 (Horvath-Kawazoe (HK) method). Se encontró que los parámetros cinéticos, las propiedades fisicoquímicas y la reactividad de los carbonizados de carbón son diferentes dependiendo de la atmósfera de pirólisis. También se determinó que para el carbonizado de carbón de SA, con un tamaño de partícula mayor de 0,7 mm, la superficie BET aumenta cuando la atmósfera se enriquece en CO2. Este efecto parece ser promovido por la interacción de diferentes procesos como las reacciones secundarias intrapartícula (ablandamiento, nucleación y coalescencia de burbujas, entrecruzamiento, entre otros), diferencias en la difusividad térmica de N2 y CO2, y los efectos reactivos de este último. Además, los ensayos de reactividad oxidativa de los sólidos mostraron que el carbonizado formado en una atmósfera de CO2 es más reactivo que el formado en N2. Con los resultados del análisis de Raman y los parámetros cinéticos cuantificados, se concluyó que la atmósfera de reacción determinó el grado de ordenación alcanzado por la estructura carbonosa y que las propiedades termo-difusivas de la atmósfera de reacción promovieron diferencias estructurales en el carbonizado, incluso a bajas velocidades de calentamiento.

Palabras clave: Pirólisis lenta, distribución de tamaño de poro, grandes partículas de carbón, Oxy-combustión, reactividad.

Received: April 29th 2017

Accepted: December 18th 2017

Introduction

As a CO2-capturing system, oxy-fuel combustion is one of the most promising processes for burning coal due to the advantages in terms of thermal efficiency, carbon burnout, reactor size-reduction, reduction of pollutants, and easy separation of CO2 from flue gas (Riaza et al., 2014; M. B. Toftegaard, Brix, Jensen, Glarborg, & Jensen, 2010). In this process, oxidation occurs using higher concentrations of O2 than those used in conventional combustion. To reduce the system and flame temperatures, the flue gases – mainly composed of CO2 – are recirculated. Additionally, a substantial reduction in NOx occurs.

The substitution of CO2 for N2 in the environment modifies the combustion characteristics due to the complexity of the system. (Kim, Choi, Shaddix, & Geier, 2014) and (Tolvanen, & Raiko, 2014), found that the temperature at the particle surface decreased when substituting N2 with CO2 even when oxygen participates in the combustion process of char. These differences were also observed in researches of Levendis’ Group (Bejarano & Levendis, 2008; Khatami, Stivers, Joshi, Levendis, & Sarofim, 2012; Maffei et al., 2013), during combustion of coal and char, with variations between 150 - 200 °C; the variations are attributed to the difference in heat capacity and diffusivity between N2 and CO2. Meanwhile, the results estimated by (Heuer et al., 2016), through CFD simulation, concerning the change in temperature were opposite, with a very low difference of only 50 °C, to which it is not possible to attribute the variations between the products obtained under N2 and CO2. Since these investigations were carried out in Drop Tube Reactors (DTR), the discrepancy on the effect of CO2 in the particle temperature could be partly reconciled when differences in the residence times and the methodology used for the measurement and estimation of the variable are considered.

However, this substitution is a source of controversy due to the contradictory results discovered by researchers Angeles G. Borrego, & Alvarez (2007) and Al-Makhadmeh, Maier, Al-Harahsheh, & Scheffknecht (2013) who carried out oxidation and pyrolysis of bituminous coals, respectively. Angeles G. Borrego, & Alvarez, (2007) studied the oxidation of bituminous coals by creating an O2/CO2 and O2/N2 atmosphere at 1300 °C in a drop tube reactor (DTR). Al-Makhadmeh et al., (2013) studied the pyrolysis of bituminous coals using an entrained flow reactor (EFR) at 1000-1150 in the presence of N2 and CO2. The residence times were 0,3s and 1 – 2,5s, respectively. In both cases, CO2-chars developed larger surface areas. On the other hand, each atmosphere produced opposite volatile releases. Such differences in the release of volatiles can be explained by the differences between the thermo-diffusive properties (C. Wang, Zhang, Liu, & Che, 2012) and their effects on pyrolysis and nascent porous structure, which is concordant with the explanation given by Saucedo et al. ( 2015), who attributed a lower oxy-combustion rate than traditional combustion to the low diffusivity of O2 in CO2.

Regarding the reactivity, Q. Li et al. (2010) and X. Li et al.( 2010), working with coals (anthracite, bituminous and subbituminous) in DTR, found differences in reactivity between chars obtained in different reaction atmospheres. While for Brix et al.(2010) in EFR, Rathnam et al. (2009) in DTR, Gil et al. ( 2012) in EFR, these differences were insignificant. Overall, these differences can be explained from the chemical composition of coal, the reaction atmosphere, and the heating rate of the solid, which demonstrates the complexity of the oxy-combustion process and the replacement of N2 with CO2. Therefore, there is permanent interest in the study of the effects of reaction atmosphere on the global process and the carbonaceous structure formed during pyrolysis.

However, despite the large number of publications that have been devoted to oxy-fuel combustion in recent years (Maffei et al., 2013; Molina & Shaddix, 2007; Murphy & Shaddix, 2006; Rathnam et al., 2009; Singer, Chen, & Ghoniem, 2013), the quantitative information about the evolution of char chemical structure in the initial stage of oxy-fuel combustion (i.e. non-pure pyrolysis in CO2) is scarce and limited to particle sizes of a few micrometers (Angeles G. Borrego & Alvarez, 2007; Su et al., 2015; B. Wang et al., 2012; Zeng, Hu, & Sarv, 2008). Therefore, is important to note, that despite the apparent abundance of reports on the effects of devolatilization in oxy-combustion, the fact is that only recently paper’s on the quality of pyrolysis solid products under oxy-fuel conditions, and exclusively for pulverized coal have been published. In this line of research, the works carried out by Senneca and Schiemann groups (Apicella et al., 2016; Heuer et al., 2016; Pielsticker et al., 2016; O. Senneca et al., 2016) are highlighted.

To explain the changes that occur during the coal devolatilization, regardless of reaction atmosphere, it is necessary to understand the structure of the coal and char (Xu et al., 2016). It is also important to note that the chars are more sensitive to intraparticle processes such as thermoplasticity, crosslinking, swelling, and fragmentation, among others, hindering their prediction (Khan & Jenkins, 1985; Speight, 2013). Studies have focused mainly on devolatilization during the oxy-fuel coal combustion in conventional boilers (small particle sizes) (Gil et al., 2012; Pielsticker et al., 2016; Rathnam et al., 2009; Su et al., 2015), but little research has addressed the implications by the change of reaction atmosphere when the particle size increases, either in fluidized bed reactors (with heating rates from 100K/s to 10 000K/s) or in some fixed bed applications (with heating rate of 100K/min) where the behavior of the oxy-combustion changes completely (Bu et al., 2015, 2016). In practical applications, devolatilization of coal is strongly influenced by the operational parameters that are dependent on the equipment and coal properties (Yu, Lucas, & Wall, 2007), making the interpretation of results for oxy-fuel coal combustion complicated.

In this research, two ranks of coal (HVBC and SA) in two reaction environments (N2 and CO2) and three particle size distributions were studied to compare the effects of pyrolysis and pyrolysis-gasification (under CO2) on the carbonaceous structure formed and to identify the effect of particle size. Despite that, research was carried out at low heating rate. To explain these effects, a comparative analysis of mass losses and structural differences for each particle size of chars formed during slow devolatilization was performed. The results confirmed that the reactive effect of CO2 (gasification) leads to higher mass losses in both coals compared to the process under N2. The results also provide evidence for changes in the pore structure of nascent chars as a result of the gasification reaction, intraparticle reactions during the molten phase, and the differences between the thermo-diffusive properties of these two gases. The reactivity to combustion and structural order of different coal ranks were related from the reactivity index and area ratios of the Raman bands (ID1/IG and IG/IALL), It was found that the slight differences between the thermal properties of the evaluated pyrolysis atmospheres are responsible for the structural changes in the char and its reactivity.

Experimental section

Samples preparation

Two Colombian coal rank samples were used in this study: Highly Volatile Bituminous C coal (HVBC) was extracted from the prolific mining region called “Cuenca del Sinifana” located in the Department of Antioquia, while Semi-anthracite coal (SA) was extracted from a mining region located in the Department of Santander. For physicochemical characterization, raw coal samples were crushed and sieved to a particle size less than 0,25 mm.

A 6500 rpm tilt hammer mill was used to reduce the size of the coal samples used in the experiments. Afterwards, they were separated into three homogeneous particle size distributions for testing in the horizontal reactor: 2,36 to 2,00 mm (named HVBCR10 and SAR10), 0,71 to 0,60 mm (named HVBCR35 and SAR35), and 45 to 38 mm (named HVBCR400 and SAR400). The chars of the carbon samples were named in the same way, adding at the end the environment under which they were obtained.

Table 1 presents the results of the physicochemical characterization of raw coal samples which were carried out following the standard methods listed in the bottom row. The error shown here represents the population standard deviation (sd) of different analyses.

Table 1. Physicochemical characterization of coal samples

|

Proximate Analysis, wt.% |

BET Area |

||||

|

m |

vm |

fc |

Ash |

m2/g |

|

|

SAsd |

1,07 |

11,64 |

79,86 |

7,59 |

0,46 |

|

HVBC |

5,29 |

39,72 |

50,71 |

4,52 |

0,03 |

|

Method |

D3173 |

D3173 |

D3173 |

D3173 |

Adsorption in N2 to -196 °C |

|

Ultimate Analysis, wt.% |

|||||

|

C |

H |

N |

O |

S |

|

|

SA |

76,57 |

3,23 |

0,16 |

11,71 |

0,74 |

|

HVBC |

68,71 |

4,88 |

1,95 |

19,21 |

0,73 |

|

Method |

D5373 |

By |

D4238 |

||

Note: vm: volatile matter, m: moisture, fc: fixed carbon, sd: standard deviation. BET Area corresponds to pores between 2 and 100nm.

Source: Authors

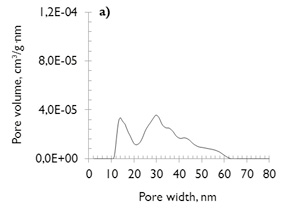

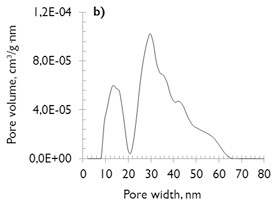

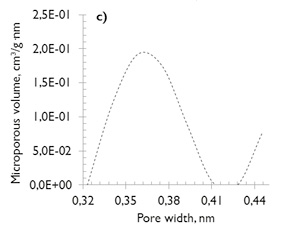

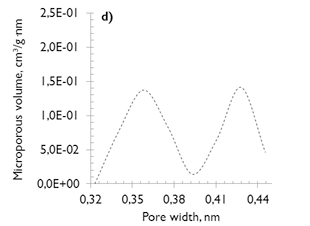

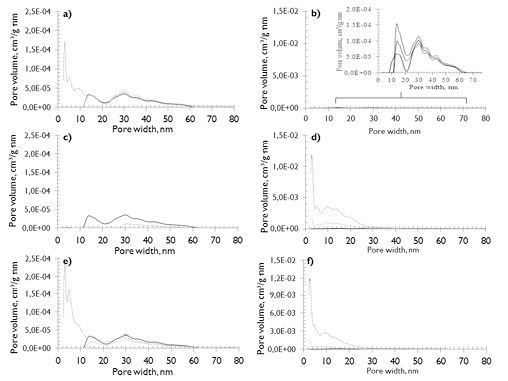

Analyses of the pore structures of the coals and the chars formed under each environment reaction (N2 or CO2) were carried out by N2 adsorption/desorption and CO2 adsorption measurements. The Pore Size Distributions (PSD’s) of mesoporous area was calculated through use of the NLDFT model (Non-Local Density Functional Theory), as it is commonly used to characterize primarily carbonaceous materials (Thommes, 2010). Both coals have similar mesoporous distributions (see Figure 1a and b) and present the bimodal PSD (with slightly higher pore volume for coal of lesser rank). This follows the results of Prinz, Pyckhout-Hintzen, & Littke (2004) and Sakurovs et al. (2012), who determined that the PSD’s are strongly affected by coal rank. In addition, Sakurovs et al., (2012) showed that pores in the size range 2 to 25nm are less common in coals of higher rank.

No major differences exist in the microporosity of the coals, comprised of micropores of diameter less than 0,7nm (also named ultramicroporos (Thommes, 2010)). The microporous volume values are similar (see Figure 1c and d), which justifies the similarity in their behavior under adsorption, despite their differences in coal rank.

Figure 1. Pore size distribution of coal samples (NLDFT model) a) and c) SA; b) and d) HVBC.

Source: Authors

Equipment and experimental procedure

Slow pyrolysis was carried out in a horizontal reactor using a heating rate of 10 ºC/min (see Figure 2a). This reactor consisted of a quartz tube, external diameter of 3,5 cm (ID: 3,0 cm) and length of 50 cm, inserted into a horizontal tube furnace that is heated by PID-controlled electric resistance using two type-K thermocouples that measure the reactor and sample temperatures. A sample of 3,0g was placed into the reactor in a quartz sample holder that was 2,0 cm in diameter and 13,5 cm long. The thermal treatment was applied from room temperature and increased at constant rate up to a maximum temperature of 900 °C under N2 or CO2 environments with analytic grade gases (purity = 99,999 %) flowing through at 50 ml/min. Before thermal treatment, the equipment was purged for 40 minutes using purely N2 or CO2 atmosphere for each respective test.

Figure 2. Experimental equipment: (a) horizontal reactor used for thermochemical transformation; (b) thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA) balance used for reactivity studies.

Source: Authors

Char reactivity and pyrolysis tests for coal samples were performed using a TGA balance (see Figure 2b). Then, for chars obtained from the pyrolysis of both coal samples and both reaction environments with particle size distributions between 45 and 38 mm, (Figure 2b) combustibility tests were implemented. The measurements were performed under non-isothermal conditions following the same procedure described by the FWO method (Flynn-Wall-Ozawa) (Ozawa, 1965; Flynn & Wall, 1966) as described by Valdés, Marrugo, Chejne, Román, & Montoya (2016). A particle bed height of less than 2 mm was fixed, which corresponded to 10mg of sample in the crucible placed in the TGA. To dry the char samples, they were heated from room temperature to 110 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C/min and held 30-min under N2 (50 ml/min). Then, coal samples were pyrolyzed in N2 (500 ml/min) and chars samples were heated under the mixing N2/O2 (50/13 ml/min). Pyrolysis tests such as combustibility were carried out from 110 °C to 900 °C at rates of 2, 5, and 10 °C/min until they were held for 60min for complete burnout.

Slow pyrolysis and reactivity tests were performed following a factorial experimental design with 22x3 triplicates. Likewise, the products of each test were characterized in triplicate. The error bars in each figure correspond to the calculation of the standard deviation of the population of tests realized for the same sample. The obtained calculations follow the uncertainty propagation rules for the parameters on DAF basis (Dry Ash Free). In order to compare the reactivity of each char sample, the sample temperature at 35 % conversion was used as the reactivity index, ensuring an index that it is not affected by the residual free moisture in samples.

Coals and chars samples analysis

Coal and char samples were reduced to particle sizes less than 0.25 mm and characterized in an elemental analyzer (EXETER, model CE-440) using the ASTM D5373 standard. Then, the proximate analysis was carried out using a thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA), employing the method described by Shi, Liu, Guo, Wu, & Liu (2013). At the end of each experiment, residual mass was removed from the sample holder and determined using an analytic balance Mettler Toledo brand, XP205 model, with precision ±0,01 mg, with that the mass loss was calculated. This was used to calculate the mass loss percent for each test. The characterization of the carbonaceous microstructure was performed by Raman spectroscopy, on a Horib Jobin Yvon brand, Labram high-resolution model, laser He/Ne 17MW 633nm and 785nm diode laser 80mW. The porous structure of the char particles was characterized through the thermal process: samples were previously dried for 24 hours at 120 °C and raw coal samples were degassed at 150 °C for one hour (for chars samples, the degassing is carried out at 300 °C). Subsequently the samples were characterized with the mean diameter (md) and mean volume (mv) of a pore, using the Horvath-Kawazoe (HK) method and pore size distribution (PSD) through N2 adsorption (BET - Brunauer-Emmett-Teller) and CO2 using a Micromeritics TriStar II Plus with precision ±0,02 m2/g. Finally, the morphological visualization of the carbonaceous structure of coals and chars was performed in a FESEM, brand JEOL JSM 7100F Model.

Results and discussion

Effect of pyrolysis atmosphere by TGA

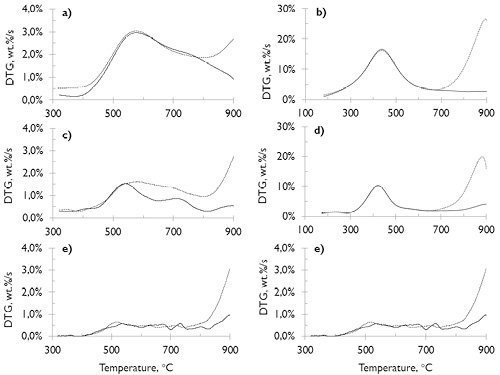

Experiments were carried out in TGA balance (see Figure 2b) to determine the kinetic parameters of the devolatilization of the two coal samples, with particle diameters between 45 and 38 µm, to elucidate the kinetic differences and similarities during pyrolysis in N2 or CO2. Figure 3 shows the DTG curves obtained from the mass loss tests under N2 and CO2 -atmosphere in both coals (See Figure 3a, c and e to SA coal and Figure 3b, d and f to HVBC coal). For both coal rank and independently of the heating rate, it was found that at higher heating rates, there is a greater mass loss rate, as reported by other studies (Niksa, Heyd, Russel, & Saville, 1985; Strezov, Lucas, Evans, & Strezov, 2004; Valdés et al., 2016).

Figure 3. Slow pyrolysis DTG curve at different heating rates ((a) and (b) at 10 °C/min, (c) and (d) at 5 °C/min, and (e) and (f) at 2 °C/min), under ¾ N2 and ---CO2 atmospheres. SA coal (a, c and d) and HVBC coal (b, d and f).

Source: Authors

DTG profiles clearly show the presence of the devolatilization steps in N2 and CO2 for SA and HVBC samples. In the mid-rank coal (HVBC) (see Figure 3b, d and f), the stage of the primary devolatilization represented in the first peak between 400 and 460 °C was clearly observed, which is related to its lower rank, its higher volatiles content and higher reactivity. For SA coal, its lower volatile content, harder structure and lower pore volume (see Figure 1a) leads to a higher primary devolatilization temperature (> 550 °C).

In SA samples, above 650 °C mainly in N2-atmosphere and at the lower heating rate, small peaks were observed, which correspond to secondary reactions and they are more frequent with the increase of the coal rank. This is related to the low volatiles content, the low local permeability and longer duration of the plastic phase of these coals (Gavalas, 1982; Oh, 1985; Perera et al., 2011). This shows that secondary reactions are difficult to prevent in TG experimental equipment. Under CO2-atmosphere above 700 °C, a grand peak was observed, at which point CO2 can oxidize the solid surface (CO2-gasification reaction).

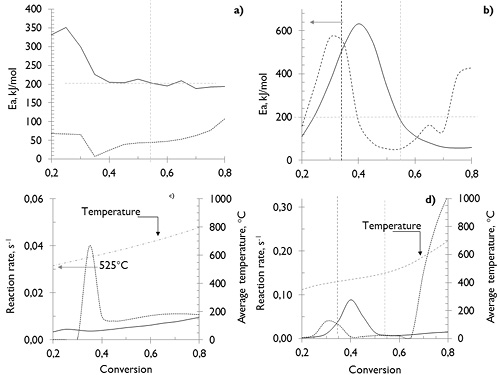

The analyses of mass loss and mass loss rate were used to calculate the activation energy, describing the thermal devolatilization mechanism of both coals during the pyrolysis processes with different conversion rate (a), using a method for various heating rates (more methodological details can be consulted in Valdés et al. (2016)). The results presented in Figure 4 suggest that since the porous structure of both coals is similar (See Figure 1), the physicochemical composition and the reaction environments are responsible for the variations in the devolatilization kinetic rates.

Figure 4. Activation energy (Ea) distribution and reaction rate devolatilization of coals a) SA and b) HVBC: ─ N2; --- CO2; --- Average temperature.

Source: Authors

The Figures 4a and 4b show that for temperatures below 378 °C (where devolatilization of HVBC coal had already started), in HVBC coal the Ea is lower than in SA coal, in which, the devolatilization is still insignificant. In HVBC coal samples at conversions lesser of 0,35 (410 °C), the Ea under N2-atmosphere is minor than under CO2-atmosphere. However, a higher reaction rate was exhibited under CO2-atmosphere, which can be explained through decarbonation reactions (CaCO3 and MgCO3 in the ashes) by thermal decomposition (Johnson, Rostam-Abadi, Mirza, Stephensn, & Kruse, 1986), and degradation of the coal matrix. The latter starts with the CO2 production by decomposition of carboxyl group at lower temperature and then the split of ethers, ketones and oxygen containing heterocycle (S. Li, Ma, Liu, & Guo, 2016; Miao, Wu, Li, Meng, & Zheng, 2012), pyrolysis water and cracking of the few released aliphatic in the narrow porous structure developed up to that moment (Arenillas et al., 2003). Therefore, diffusive type restrictions of volatile matter released in CO2 can be irrelevant to the reaction rate at these temperatures.

At conversions between 0,35 and 0,55 (410 to 472 °C), the Ea and the rate of reaction during the devolatilization of the HVBC is higher in N2 than that in CO2, which is consistent with the intervals in which the primary devolatilization, where the higher mass loss rate was reached. These results can be explained through the greater diffusive type restrictions that volatiles have in the presence of CO2 (Molina & Shaddix, 2007; Valdés et al., 2016), which implies a minor interaction between the CO2-atmosphere and char (less occurrence of secondary processes between CO2 and char at low temperatures). Therefore, a reduction in the values of the Ea and reaction rate can be expected.

Given the lower content of volatile matter for SA coal and that its devolatilization reaction is significant at higher temperatures (greater at 525 °C, see Figure 4a), the Ea and reaction rate for the different stages coexisting during devolatilization (pyrolysis and gasification) of SA samples, were lower than that for HVBC coal until a 55 % conversion is reached (see Figure 4). This implies a larger energy barrier during the primary devolatilization; nevertheless, the higher reaction rate exhibited by the lowest coal rank is determined by the higher content of released volatile material and not because of the reaction atmosphere. This can be explained by the reactive effects of the atmosphere on some of the volatile species which are released and the development of porous structure (Yin & Yan, 2016). Also, the high temperature (above 600 °C) favors the occurrence of the CO2-gasification reaction (Su et al., 2015; Valdés et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2016); which provided a slightly higher reaction rate when the coals were pyrolyzed under a CO2-atmosphere compared to N2 (see Figure 4c and d).

The results presented in Figure 4 also confirm that given the higher content of volatile matter in the lower rank coal under the experimental conditions, the HVBC is ten times more reactive during pyrolysis (reaction rate HVBC >> SA coal), despite requiring a greater activation energy. However, HVBC coal have a higher pre-exponential factor (C. Wang et al., 2012), which, by definition, indicates a higher probability for reaction occurrence. Additionally, it was observed that during the pyrolysis of HVBC coal, the reaction rate is higher in N2 than in CO2 until temperatures around 600 °C. Above this temperature, the CO2 takes the already demonstrated oxidant properties that increase the reaction rate in this atmosphere. The results for temperatures below 600 °C can be explained through the differences between the thermo-diffusive properties of CO2 and N2, see Valdés et al. (2016). In CO2, due to a lower rate of diffusion of volatiles released, intraparticle secondary reactions can be promoted(Molina & Shaddix, 2007; C. Wang et al., 2012). Further, CO2 can react with the carbonaceous structure (Gonzalo-Tirado & Jiménez, 2015; Gonzalo-Tirado, Jiménez, & Ballester, 2013; Hecht, Shaddix, Geier, Molina, & Haynes, 2012). While, when N2 atmosphere is used, its lower volumetric energy density (kJ/ m3) alters the heat transfer between phases, causing the most thermally severe pyrolysis in this environment.

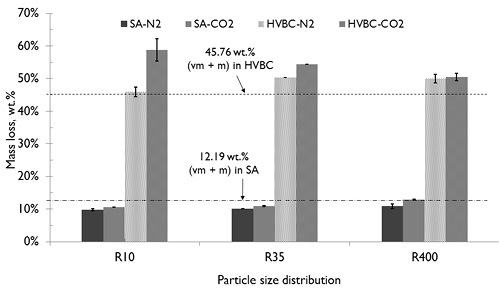

Effect of pyrolysis atmosphere on char structure evolution

The total mass loss of the chars prepared in the N2 and CO2 atmospheres until 900 °C in the horizontal reactor are shown in Figure 5. The mass loss was higher for the coal sample of lower rank (HVBC) than for the higher rank (SA) sample. Additionally, the mass loss was higher in the CO2 atmosphere than in the N2 atmosphere, concordant with the results of other research (Su et al., 2015; B. Wang et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2008). The mass loss in all samples of HVBC coal pyrolyzed in N2 and CO2 atmospheres was greater than the sum of the volatile content and moisture for the proximate analysis reported (see Table 1), similar to that obtained by B. Wang et al., (2012) and Yan, Cao, Cheng, Jin, & Cheng, (2014) at high heating rate.

Additionally, for samples of HVBC coal, mass loss in CO2 atmosphere was marked significantly greater with increases of the particle size, whereas the samples processed under N2 did not show observable differences. This is also attributed to the differences in thermo-diffusive properties between CO2 and N2 (Molina & Shaddix, 2007; C. Wang et al., 2012; Valdés et al., 2016).

For SA coal, overall mass loss was always slightly lower than the sum of the content of volatile matter and moisture. This could be a consequence of the strong influence of the thermodeactivation by thermal annealing or by thermoplastic properties of coal, which were much more relevant for high rank coals. This has been studied by Gavalas (1982), Peter R. Solomon, Serio, & Suuberg (1992), and Perera et al. (2011) who found that pore number and permeability decreases as coal rank increases. The presence of the thermoplastic phase favors the occurrence of intraparticle secondary reactions and encapsulation of volatile matter (Hayhurst & Lawrence, 1995; Larsen, 2004).

Figure 5. Mass loss of the samples pyrolyzed in horizontal reactor under N2 and CO2 atmospheres compared to combined value of volatile matter and moisture.

Source: Authors

The differences in mass loss are not significant for particle sizes between 45 and 38 mm. In the case of samples treated under N2 atmosphere, a possible explanation, despite the large differences between the heating rates used, is thermodeactivation of the char by thermal annealing, as shown by Osvalda Senneca, Salatino, & Masi (2005). This prevents, in the case of the tests under CO2, the gasification reaction of Boudouard from having an impact on the process. The previous explanation does not agree with the results of another research by Osvalda Senneca & Cortese (2012), where they show that for a heating rate and coal of similar range to the one used in the present investigation, the contribution of the gasification reaction is significant; however, such a discrepancy may be due to the large difference between the ash contents of both coals.

Another possible explication for both atmospheres may be due to the smaller particle size: there is increased exposure of volatile material to the surrounding environment, coupled with the low gas velocity (equivalent to 1,2x10-3 m/s). The Biot and Pyrolysis numbers are less than 0,1 and greater than 10, respectively. This means that the process is governed by the release of primary devolatilization products, regardless of the reaction atmosphere since the process is in the kinetically controlled regime. Additionally, this is consistent with studies of scales characteristic times of the phenomena occurring during thermochemical transformations, carried out by Dufour, Ouartassi, Bounaceur, & Zoulalian (2011) and Stark (2015), with biomasses.

With the aim of validating the reactive effects of CO2 and the implications of the change in the particle size on the chemical composition and the porous structure developed during the process of pyrolysis, char samples were characterized through proximate and ultimate analysis, as shown in Table 2 in DAF basis. The mean values of VM, FC and C for the chars reflect CO2-volatile and CO2-char reactions. Regardless of rank and particle size, the FC was always lower under the CO2 atmosphere than under N2. Similar effects of CO2 have been observed by other researchers in gasification studies (Gonzalo-Tirado et al., 2013; Rathnam et al., 2009; Su et al., 2015). The VM content in chars was always higher for those obtained in a CO2 atmosphere. This also can be explained by the lower diffusion of volatiles, occurrence of secondary intraparticle reactions, and changes in the local permeability of the chars due to the atmosphere.

Table 2. Chemical characterization of chars and coals in daf basis

|

Samples |

VM, (wt.%) |

FC, (wt.%) |

C, (wt.%) |

|

SA |

12,74 ± 0,02 |

87,42 ± 0,01 |

82,83 ± 0,02 |

|

R10N2 |

4,70 ± 0,01 |

95, 44 ± 0,02 |

83,32 ± 0,02 |

|

R10CO2 |

6,60 ± 0,00 |

93,96 ± 0,09 |

82,02 ± 0,05 |

|

R35N2 |

4,02 ± 0,02 |

96,18 ± 0,05 |

84,94 ± 0,02 |

|

R35CO2 |

4,35 ± 0,03 |

95,86 ± 0,07 |

82,98 ± 0,06 |

|

R400N2 |

5,32 ± 0,02 |

94,77 ± 0,07 |

94,44 ± 0,02 |

|

R400CO2 |

7,34 ± 0,03 |

92,72 ± 0,03 |

86,66 ± 0,01 |

|

HVBC |

44,04 ± 0,02 |

56,22 ± 0,02 |

76,19 ± 0,02 |

|

R10N2 |

11,89 ± 0,03 |

88,20 ± 0,06 |

91,65 ± 0,02 |

|

R10CO2 |

14,36 ± 0,05 |

85,95 ± 0,12 |

93,86 ± 0,04 |

|

R35N2 |

11,82 ± 0,03 |

86,19 ± 0,07 |

95,45 ± 0,05 |

|

R35CO2 |

13,62 ± 0,05 |

86,98 ± 0,05 |

96,05 ± 0,06 |

|

R400N2 |

12,20 ± 0,03 |

87,92 ± 0,03 |

90,86 ± 0,01 |

|

R400CO2 |

15,29 ± 0,03 |

85,29 ± 0,04 |

97,11 ± 0,04 |

Note: VM: volatile matter, FC: fixed carbon, C: carbon

Source: Authors

It is important to highlight that researchers such as Khan & Jenkins (1985) and Larsen (2004) have provided great evidence of the plasticizing effect of CO2 in carbonaceous materials. It has been shown that under pressurized conditions (Khan & Jenkins, 1985; Larsen, 2004) and/or thermal gasification conditions (Khan & Jenkins, 1985), dissolution of CO2 in coals is possible. This phenomenon manifests itself as slight swelling or shrinkage of the particles by reordering of their physical structure. CO2 also reduces the softening temperature of the coal (Khan & Jenkins, 1985). Therefore, the result of the chemical characterization of chars and coals shown in Table 2 gives evidence that during devolatilization, CO2 enhances thermoplastic behaviors in both coals. Thermoplastic behavior contributes to chars with a higher content of volatile matter due to encapsulation of volatiles in the plastic phase (Hayhurst & Lawrence, 1995; Larsen, 2004). It consequently leads to more intraparticle secondary reactions. This is consistent with many proposed models of devolatilization, including one by P. R. Solomon, Hamblen, Carangelo, Serio, & Deshpande (1988), which shows that the viscosity of coal in its plastic state has an inverse relationship with the diffusion coefficient of the pyrolysis products.

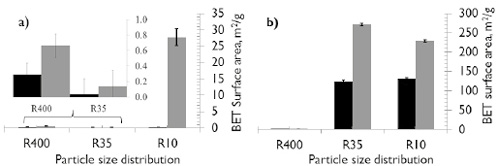

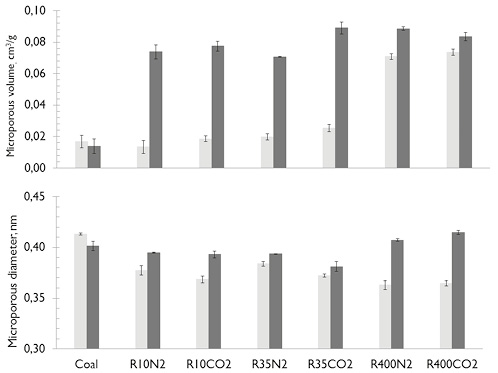

The physical structures of the chars are also affected by the different reaction conditions. Measurement of the porous surface area was performed via adsorption/desorption with N2 (see Figure 6). It is evident that the BET surface area (Figure 6b) increased with particle size for HVBC in both atmospheres compared to the raw samples (Table 1). However, the surface area does not increase for the smaller particle size regardless of the reaction environment. Additionally, a higher development of BET surface area for the HVBC chars obtained under an atmosphere of CO2 versus N2 is reflected in the larger pore volume (see Figure 7d and f) and is consistent with the results found by Zeng et al. (2008), which used particle sizes between 106-125 mm.

In this research, for particle size between 45-38 mm, neither coals (HVBCR400 and SAR400) nor environments (N2 and CO2) showed variation in the BET surface area. This is consistent with the results reported by Brix et al. (2010), who worked with similar ranking coals but with particle sizes between 90 and 105 mm.

Brix et al., found a similar morphology of the residual char and a similar volatile release in both atmospheres. A possible explanation is that with small particle sizes, the volatiles are more exposed to the surrounding atmosphere, favoring their release without causing significant evolution of BET surface area by intraparticle diffusive processes or reaction of the surrounding environment with the carbonaceous structure. However, the volatiles release from the coal microstructure favors the development of small pores (less than 0,7nm).

The PSDs for chars named SAR400 and HVBCR400 (see Figure 7a and b), in both atmospheres, are practically unchanged in comparison to raw coals (the mesoporous distribution continues to be bimodal) particularly for HVBCR400 samples independent of reaction atmosphere. Mesopores with diameters between 2-10 nm appeared in SAR400CO2 char samples (see Figure 7a), evidenced by a slight increase in BET surface area (see zoom in Figure 7a) and an increase of micropore volume with a decrease in the average diameter when the particle size decreased (see Figure 8).

Figure 6. BET surface area of char formed in different atmospheres. a) SA; b) HVBC. ■ N2 ■CO2.

Source: Authors

Figure 7. Pore size distribution (NLDFT method) of coal chars formed under CO2 and N2. a)R400, c)R35 and e)R10 correspond to SA samples; b)R400, d)R35 and f)R10 correspond to HVBC samples; ─ coal samples; ─ char samples under N2; ─ char sample under CO2.

Source: Authors

The authors hypothesized that variations in surface area with different particle sizes are due to the combined effect of the carbonaceous structure and reaction environment on interactions with volatiles and char. This has been explained and demonstrated for devolatilization in N2 (Borah, Ghosh, & Rao, 2008; Ross, 2000), where increased residence times of volatiles in the particle led to more char. In this research, when the volatile matter content was high as in the case of coal HVBC, it was very likely that during transport of the products of primary devolatilization, bubble-explosions generated pore volume. This increased porosity (see Figure 7b), when the devolatilization atmosphere was CO2, it could have occurred because in this environment, the migration of volatiles was more complex. This is due to the lower diffusion coefficient of volatiles in CO2, which causes bubbles to nucleate and subsequently explode, leading to large pore development. Therefore, as observed for char obtained under CO2 atmosphere, there was a greater generation of pore volume and an increase in surface area. This is consistent with the results reported by A.G. Borrego, Garavaglia, & Kalkreuth (2009), who concluded that CO2 promotes cross-linking reactions and the formation of more pore volume.

Figure 8. Microporous volume and diameter from Horvath-Kawazoe method for char and coals. ■ SA ■ HVBC.

Source: Authors

In coal of high rank (SA), having a low content of volatile material and a more organized structure, BET surface area is only developed for the large particle sizes (SAR10, > 2 mm), as shown in Figure 6a. When the coals are pyrolyzed in a CO2 atmosphere, the CO2-char interactions (gasification) produce a slight development of BET surface area. This is also evidenced in the PSD of SAR10CO2 samples (see Figure 7e), where there is considerable evolution of mesoporosity between 2 and 10nm.

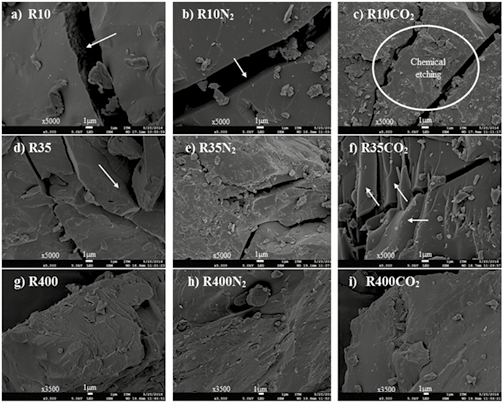

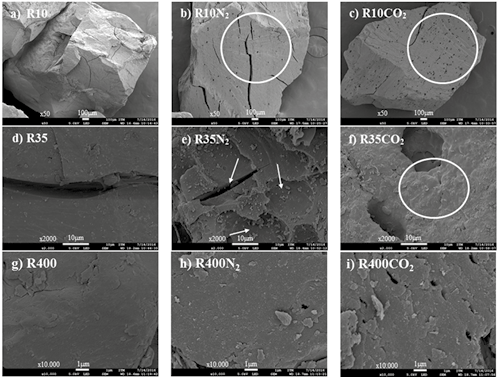

To complement the morphological study, all coal and char samples were visualized using a FE-SEM. The photomicrographs in Figures 9 and 10 illustrate the differences between samples of coal and chars prepared under different atmospheres.

The first column in figures 9 and 10 (a, d and g) shows the unpyrolyzed coals (R10, R35 and R400) for SA and HVBC. For both, the surfaces have irregular edges along fractures and the internal surfaces are rough; this is more apparent in SA than in HVBC. These fractures likely come from the milling process and are sites where volatiles can be released during the thermochemical processing.

SAR10 chars have well defined edges but the internal walls are smoother under N2 than under CO2 (Figures 10b and c; respectively). This could be caused by a more violent release of volatiles and plastic transformation during pyrolysis under N2. The highest heating rate is evidenced in this environment because of lower energy density (r ∙ Cp) in comparison to the energy density of CO2 (Kim et al., 2014; Molina & Shaddix, 2007; Tolvanen & Raiko, 2014). Also, the presence of spongy masses of micronic diameter (1 to 2 micrometers), similar to those found by Heuer et al. (2016), and characterized in detail by Apicella et al. ( 2016) was visible. In agreement with the work of Heuer et al., more of these micronic particles were found in the char obtained under atmosphere of CO2 than under N2. In general, chars obtained under CO2 have a rougher surface and provide evidence of the chemical etching which implies that gasification reactions occurred (Bu et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2016). Gasification is likely responsible for the variation of surface area in these samples (see Figure 6a).

Figure 9. SEM micrographs of SA coal and chars formed in different atmospheres (CO2 and N2).

Source: Authors

Figure 10. SEM micrographs of HVBC coal and chars formed in different atmospheres (CO2 and N2).

Source: Authors

Figures 10b) and c) show char samples obtained under N2 and CO2; respectively. It is observed that due to the thermochemical processing, holes were developed by release of volatiles with more holes present in the char from CO2 atmosphere (Riaza et al., 2014).

In accordance with the effects on the char with reduced particle size, chars from both R35N2 and R400N2 coals (subplots e and h, respectively, Figures 9 and 10) have smooth surfaces with very few holes. However, chars with particle size R35 and R400 (f and i) obtained from both coals under CO2 atmosphere show that for smaller distributions, there was not much superficial exfoliation; this behavior is contrary to R10CO2 (Figures 9c and 10c). The presence of smooth, rounded edges was also common in both atmospheres, but more marked in the N2 atmosphere. These effects are characteristic of a material that passed through a plastic phase. Therefore, it is likely that as the particle size is reduced, the differences between the two environments are not relevant to the primary devolatilization reactions. With the low particle size, the thermal gradients are minimal. However, char produced under CO2 still exhibits softening effects compared to N2.

Impact of pyrolysis atmospheres on char micro-structure evolution

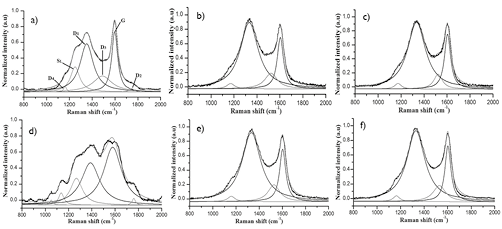

Raman spectroscopy analysis was performed for samples of raw coal and chars obtained under both reaction atmospheres (N2, CO2) and three different particle size distributions. Raman spectra were corrected with the same baseline, then smoothed and normalized with respect to the total area of each Raman analysis. In Figure 10, the spectra of samples of coal (HVBC and SA) and chars are presented for the particle size denoted as R400. In all cases it is possible to observe bands D1 and G, characteristic of carbonaceous materials, positioned around 1350 and 1580 cm-1; respectively (Reich & Thomsen, 2004; Tuinstra, 1970). For more information on the structural characteristics of the tested samples, the deconvolution was performed in 6 bands for raw materials and 4 bands for chars using Lorentzian functions.

It is observed in Figure 11a and 11d that the spectra of the coal samples are different, but characteristic of their respective ranks. Since the intensity of the graphitization band for SA coal is greater than for HVBC coal, greater organization is present in the higher-ranking SA coal. An increased intensity of D2 and D4 bands observed for HVBC coals, which is characteristic of materials with a very poor organization, is consistent with them being lower-ranking coals. Among the chars, independent of coal and devolatilization atmosphere, no major differences were observed. This may be because the low heating rate of thermochemical processing. The slight differences showed the effects of reaction atmosphere on microstructure at a high heating rate.

The differences are expected to be more remarkable with a higher heating rate. In addition, the spectra validate that during the thermochemical transformation of coal to char, migration occurs in long-chain aliphatic structures, alky-aryl ether, C-C and methyl groups associated with aromatic rings denoted sp3, according to Table 3 and grouped in the band SL (1250 cm-1), as described by X Li, Hayashi, & Li (2006).

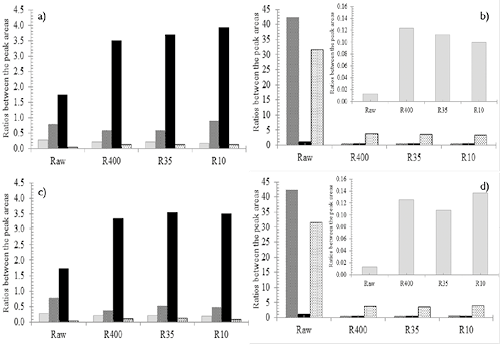

Since the qualitative differences are very small, the area ratios of the bands and all Raman spectra were quantified. This are referred to as ID1/IG, ID3/IG, ID4/IG and IG/IALL. Figure 12 shows the different area ratios for all coals and chars devolatized in both atmospheres. Figures 12a) and 12c) show changes in the relative intensities of the bands ID1 and ID3 with respect to IG. It can be seen that for SA coal, the ratios ID1/IG, ID3/IG are slightly lower for thermal treatment under CO2 atmosphere compared to N2 treatment, while for HVBC coal (see Figures 12c and d) no significant differences were found.

Figure 11. Raman spectra of coal and chars (R400) under N2 and CO2 atmospheres. a) SA; b). CharSA-N2; c). CharSA-CO2; d). HVBC; e). CharHVBC-N2; f). CharHVBC-CO2.

Source: Authors

The lower values for the ID1/IG ratio in SA chars under CO2 atmosphere and three particle sizes can be explained by the increase in the condensation of aromatic rings as was first noted by X Li et al. (2006). While not necessarily leading to the decrease of defects in the structure, the high condensation of amorphous carbon due to random arrangement could generate more defects in the structure.

Table 3. Summary of Raman peak/band assignment

|

Band name |

Band |

Description |

Bond type |

Ref. |

|

D4 |

1150 |

Caromatic-Calkyl; aromatic/aliphatic ethers; C-H on aromatic rings; active sites in carbons. |

sp2, sp3 |

(C. Wang et al., 2012) |

|

D1 |

1350 |

Highly disordered carbonaceous material, C-C between aromatic rings and aromatics with not less than 6 rings. |

sp2 |

(Sheng, 2007) |

|

D2 |

> 1620 |

It is a shoulder on the G band, but its signification is not yet well understood; but this is related to bands induced by the defects in the microcrystalline lattices appear in the first order region around as carbonyl groups |

sp2 |

(Lin-Vien, 1991; Beyssac et al., 2003) |

|

D3 |

1500 |

Methylene or methyl; amorphous carbons structures; smaller aromatics with 3–5 fused rings. |

sp2, sp3 |

(Sheng, 2007; C. Wang et al., 2012) |

|

G |

1580 |

Graphitic band |

sp2 |

(Sheng, 2007) |

|

SL |

1230 |

Aryl-alkyl ether; p-aromatics |

sp2, sp3 |

(X Li et al., 2006) |

Source: Authors

The results also agree with the works reported by Sheng (2007), Zhu & Sheng (2010) and C. Wang et al. (2012). Using lower rank coals, they found that the heat treatment leads to an ordering of the carbonaceous structure with respect to increasing temperature (see Figure 12b and d for HVBC chars). This is corroborated with the decrease of ID3/IG, ID4/IG, and ID1/IG and the increase of IG/IALL for chars, independent of reaction atmosphere and particle size. The decrease of ID3/IG, ID4/IG, and ID1/IG have been confirmed by other researchers (Sheng, 2007; C. Wang et al., 2012; Zhu & Sheng, 2010). The decreasing trend of the ratio ID1/IG suggests an increase in the mean size of graphitic microcrystals during the thermal treatment, while the decrease of the ratios ID4/IG and ID3/IG gives information about release of volatile matter, the removal of active sites, and imperfections of amorphous carbon crystals.

Figure 12. Ratio of band peak areas of different chars prepared in N2 and CO2 atmospheres. a) SA in N2; b) HVBC in N2; c) SA in CO2 and d) HVBC in CO2. ■ IG/IALL; ■ ID3/IG; ■ ID4/IG; ■ ID1/IG

Source: Authors

Regarding the effect of the CO2 atmosphere on the level of structural arrangement achieved by HVBC chars, an increase for IG/IALL was observed, especially for the R10 particle size, (contrary to what occurs in the char obtained under N2). This is related to the greater influence of intraparticle reactions to this size, as evidenced in the BET and visualization FESEM analyses. A more disordered char structure is obtained under pyrolysis in CO2 due to the oxidant effects that favor the concentration of structural defects in various forms in coal, and promote greater influence of plastic processing (Sheng, 2007; Su et al., 2015; C. Wang et al., 2012).

For SA chars evaluated in both environments (see Figure 12a and c), the development of ratios IG/IALL and ID3/IG decreased with the thermochemical treatment, regardless of particle size and reaction atmosphere. This shows that during the thermochemical processing, a disruption of char structure occurs according to the ratio IG/IALL. Therefore, the carbonaceous char microstructure from SA coal exhibited less order than the raw coal. This effect was lower for smaller char particles and also while using the CO2 atmosphere. This is explained by the strong thermo-plastic effects in high-ranking coals, especially with larger particle size (P. R. Solomon et al., 1988). Additionally, given the oxidant effect of CO2 and the low content of volatile matter, the interaction between environment-char is stronger than that in HVBC.

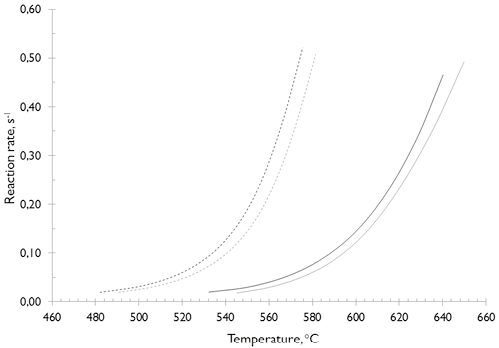

Impact of pyrolysis atmospheres on char reactivity

Since the overall mass losses for both coals with particle sizes between 45 and 38 mm were not strongly affected by the reaction atmosphere and that BET surface area remained unchanged, testing of the oxidation reactivity of chars obtained under different atmospheres was performed to identify the chemical changes. Reactivity was measured by TGA using the FWO method (Valdés et al., 2016), under an oxygen environment (O2/N2 = 21.6/78.4 %v/v). As shown in Figure 13, the reactivity to combustion was greater for chars obtained under CO2 than under N2. This is consistent with the results of intensity of the Raman bands and intensity band analysis explained above. Therefore, it is confirmed again that the chars produced under a CO2 environment are more disordered than those obtained under N2 atmosphere.

Figure 13. Oxidation reactivity both char coals.

---- HVBC in CO2, ---- HVBC in N2, ¾ SA in CO2, ¾ SA in N2.

Source: Authors

Differences in reactivity can also be explained by the surface area and the PSD of the chars obtained in both atmospheres: a greater surface area leads to higher reactivity. This demonstrates that reactivity is dependent on the structure of the coal chars produced under both environments. These results are in agreement with other research on coals of similar rank (Angeles G. Borrego & Alvarez, 2007; C. Wang et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2008) and they disagree with those obtained by Senneca and Schiemann groups (Apicella et al., 2016; Heuer et al., 2016); However, the differences between experimental conditions are the main cause of results divergence.

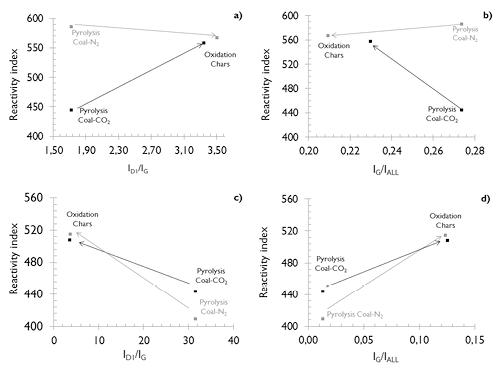

Correlation between structural changes

and char reactivity

A correlation between the reactivity and the area ratio of bands from Raman spectrum characteristics of carbonaceous materials was found. These studies seek to demonstrate the existence of a relationship between the decrease in the reactivity and increase in the order of the microstructure by thermal treatment. This is reflected in the increased value of the area ratio of the bands IG/IALL and decrease in the area ratios of the bands ID1/IG, ID2/IG, ID3/IG, and ID4/IG.

The results are presented in Figure 14 for both coals and chars. The coals were evaluated under reaction atmospheres of CO2 and N2, while for chars the oxidation reactivity to an O2/N2 atmosphere was evaluated. Figures 14c and 14d present the relationship between the reactivity index and Raman ratios (ID1/IG, IG/IALL) for HVBC coal and chars. The results showed an increase in reactivity index of the carbonaceous structures when the ratios ID1/IG and IG/IALL increased, which is consistent with the most ordered structure exhibited by the char obtained under N2.

Figures 14c and 14d also reveal that the reactivity index due to oxidation exhibited by the structure of the char from HVBC coal is greater than that determined for raw coal during devolatilization in either atmosphere. These relationships explain that HVBC coal is more reactive than its respective chars, because of its middle-ranking, less-ordered structure which cause their lower reactivity index under devolatilization. Additionally, the results reveal that HVBC chars obtained under N2 atmosphere are less reactive than those from CO2, which is consistent with the results presented in Figure 13 (dashed lines) and obtained by Zhang et al. (2015), for a similar rank coal. Those researchers attributed this difference to a high concentration of defects in the crystal structure caused by the reaction atmosphere, differences in heating rate, and to the greater energy density of CO2 compared to N2, which leads to a lower value of the IG/IALL relationship in the structure of the char obtained under CO2.

Figure 14. Correlations between the reactivity index and the band area ratios (a and b) SA and (c and d) HVBC ■ under CO2 atmosphere ■ under N2 atmosphere.

Source: Authors

The analysis of the evolution of ID1/IG and IG/IALL ratios for SA coal and chars presented an opposite behavior to that shown by coals of lower rank. The results of Figures 14a and 14b indicate that with the increase of the ratio ID1/IG and decrease of the ratio IG/IALL, the structure of the char obtained under N2 atmosphere is more reactive than the SA coal, decreasing its reactivity index. Meanwhile those obtained under CO2 atmosphere lessen their reactivity index under devolatilization but remain more reactive to oxidation than those obtained under N2. The increase in the ratio ID1/IG and decrease in the ratio IG/IALL agrees with the findings by X Li et al. (2006) and Zhu & Sheng (2010). They explained that these trends are due to the increased concentration of aromatic rings, having 6 or more fused benzene rings as a result of the hydrogenation of aromatics. This behavior is possible due to the occurrence of annealing phenomena under N2 atmosphere, given its lower energy density, which inhibits the evolution of the structure to a more ordered system. The reactive effects of CO2 are so complex that while improving the de-hydrogenation of hydro-aromatics and promoting the growth cluster of aromatic rings, they can also introduce functional groups with oxygen, which reflect in a more disordered structure.

Conclusions

In this study, a higher reactivity was observed for HVBC chars prepared under a CO2 atmosphere in comparison to those prepared in N2. However, the difference in reactivity between SA chars formed under N2 and CO2 was not significant. The dependence of these effects is explained by gasification reactions, thermo-diffusive properties of the volatiles released in surrounding atmosphere, and the grade of influence of thermoplastic properties of coals. The latter is more relevant in high-ranking coals. In the same sense, it is explained that the surface area development is greater for the chars obtained under CO2 atmosphere than those with N2 atmosphere due to bigger residence times for contact between the gases and the carbonaceous structure.

In regards to microstructure, the lower value of ID1/IG ratio, obtained for HVBC chars compared to coal samples and the higher reactivity during coal pyrolysis, is related to highly disordered structures. These structures can be more abundant in the chars obtained under the presence of CO2 than under N2 due to the gasification reactions. Additionally, the increased presence of volatile matter and oxygen in this material led to an increase in porosity during the thermochemical process. Thus, a decrease in the crystalline domain size of the carbonaceous network is favored. Finally, the effects on the nascent char in CO2 atmosphere are more complex, to the point that it is also likely that new structures formed contain a higher concentration of hetero-atoms and oxygen functional groups than could have been introduced by the gasification reaction. This also explains the increase in Raman intensity as oxygen increases the dispersion, confirming that more disordered char structure is formed under CO2.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the “Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia Tecnologia e Innovación” - COLCIENCIAS (Administrative Department of Science, Technology and Innovation from Colombia) through the project “Research on advanced combustion innovation in Industrial use”, code no. 1115-543-31906 contract no. 0852-2012. The authors thank the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and Universidad de Antioquia. To Benjamin H. Hall and Corey M. Beck of Purdue University, to Todd Lang of Noresco Company. Thanks to them, for their invaluable contribution.

References

Al-Makhadmeh, L., Maier, J., Al-Harahsheh, M., & Scheffknecht, G. (2013). Oxy-fuel technology: An experimental investigations into oil shale combustion under oxy-fuel conditions. Fuel, 103, 421–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2012.05.054

Apicella, B., Senneca, O., Russo, C., Heuer, S., Cortese, L., Cerciello, F., … Ciajolo, A. (2016). Separation and characterization of carbonaceous particulate (soot and char) produced from fast pyrolysis of coal in inert and CO2 atmospheres. Fuel. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2016.11.049

Arenillas, A., Rubiera, F., Pis, J. ., Cuesta, M. ., Iglesias, M. ., Jiménez, A., & Suárez-Ruiz, I. (2003). Thermal behaviour during the pyrolysis of low rank perhydrous coals. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 68–69, 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-2370(03)00031-7

Bejarano, P. A., & Levendis, Y. A. (2008). Single-coal-particle combustion in O2/N2 and O2/CO2 environments. Combustion and Flame, 153(1–2), 270–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2007.10.022

Beyssac, O., Goffé, B., Petitet, J.-P., Froigneux, E., Moreau, M., & Rouzaud, J.-N. (2003). On the characterization of disordered and heterogeneous carbonaceous materials by Raman spectroscopy. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 59(10), 2267–2276. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1386-1425(03)00070-2

Borah, R. C., Ghosh, P., & Rao, P. G. (2008). Devolatilization of coals of North-Eastern India under fluidized bed conditions in oxygen-enriched air. Fuel Processing Technology, 89(12), 1470–1478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2008.07.011

Borrego, A. G., & Alvarez, D. (2007). Comparison of Chars Obtained under Oxy-Fuel and Conventional Pulverized Coal Combustion Atmospheres. Energy & Fuels, 21(6), 3171–3179. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef700353n

Borrego, A. G., Garavaglia, L., & Kalkreuth, W. D. (2009). Characteristics of high heating rate biomass chars prepared under N2 and CO2 atmospheres. International Journal of Coal Geology, 77(3–4), 409–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2008.06.004

Brix, J., Jensen, P. A., & Jensen, A. D. (2010). Coal devolatilization and char conversion under suspension fired conditions in O2/N2 and O2/CO2 atmospheres. Fuel, 89(11), 3373–3380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2010.03.019

Bu, C., Leckner, B., Chen, X., Gómez-Barea, A., Liu, D., & Pallarès, D. (2015). Devolatilization of a single fuel particle in a fluidized bed under oxy-combustion conditions. Part B: Modeling and comparison with measurements. Combustion and Flame, 162(3), 809–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2014.08.011

Bu, C., Pallarès, D., Chen, X., Gómez-Barea, A., Liu, D., Leckner, B., & Lu, P. (2016). Oxy-fuel combustion of a single fuel particle in a fluidized bed: Char combustion characteristics, an experimental study. Chemical Engineering Journal, 287, 649–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2015.11.078

Dufour, A., Ouartassi, B., Bounaceur, R., & Zoulalian, A. (2011). Modelling intra-particle phenomena of biomass pyrolysis. Chemical Engineering Research and Design, 89(10), 2136–2146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2011.01.005

Flynn, J. H., & Wall, L. A. (1966). A quick, direct method for the determination of activation energy from thermogravimetric data. Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Letters, 4(5), 323–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/pol.1966.110040504

Gavalas, G. R. (1982). Coal pyrolysis. Amsterdam; New York: New York, N.Y: Elsevier Scientific Pub. Co.: Distributors for the U.S. and Canada, Elsevier Science Pub. Co.

Gil, M. V., Riaza, J., Álvarez, L., Pevida, C., Pis, J. J., & Rubiera, F. (2012). Oxy-fuel combustion kinetics and morphology of coal chars obtained in N2 and CO2 atmospheres in an entrained flow reactor. Applied Energy, 91(1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.09.017

Gonzalo-Tirado, C., & Jiménez, S. (2015). Detailed analysis of the CO oxidation chemistry around a coal char particle under conventional and oxy-fuel combustion conditions. Combustion and Flame, 162(2), 478–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2014.08.002

Gonzalo-Tirado, C., Jiménez, S., & Ballester, J. (2013). Kinetics of CO2 gasification for coals of different ranks under oxy-combustion conditions. Combustion and Flame, 160(2), 411–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2012.10.020

Hayhurst, A. N., & Lawrence, A. D. (1995). The devolatilization of coal and a comparison of chars produced in oxidizing and inert atmospheres in fluidized beds. Combustion and Flame, 100(4), 591–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-2180(94)00109-6

Hecht, E. S., Shaddix, C. R., Geier, M., Molina, A., & Haynes, B. S. (2012). Effect of CO2 and steam gasification reactions on the oxy-combustion of pulverized coal char. Combustion and Flame, 159(11), 3437–3447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2012.06.009

Heuer, S., Senneca, O., Wütscher, A., Düdder, H., Schiemann, M., Muhler, M., & Scherer, V. (2016). Effects of oxy-fuel conditions on the products of pyrolysis in a drop tube reactor. Fuel Processing Technology, 150, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2016.04.034

Ito, O. (1992). Diffuse reflectance spectra of coals in the UV-visible and near-IR regions. Energy & Fuels, 6(5), 662–665. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef00035a019

Johnson, L., Rostam-Abadi, M., Mirza, I., Stephensn, M., & Kruse, C. (1986). Co-pyrolysis of coal and oil shale I: Thermodynamics and kinetics of hydrogen sulfide capture by oil shale. Illinois state geological survey. Retrieved from https://web.anl.gov/PCS/acsfuel/preprint%20archive/Files/30_3_CHICAGO_09-85_0274.pdf

Khan, M. R., & Jenkins, R. G. (1985). Thermoplastic properties of coal at elevated pressures: effects of gas atmospheres. Presented at the International Conference on Coal Science, Sydney.

Khatami, R., Stivers, C., Joshi, K., Levendis, Y. A., & Sarofim, A. F. (2012). Combustion behavior of single particles from three different coal ranks and from sugar cane bagasse in O2/N2 and O2/CO2 atmospheres. Combustion and Flame, 159(3), 1253–1271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2011.09.009

Kim, D., Choi, S., Shaddix, C. R., & Geier, M. (2014). Effect of CO2 gasification reaction on char particle combustion in oxy-fuel conditions. Fuel, 120, 130–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2013.12.004

Larsen, J. W. (2004). The effects of dissolved CO2 on coal structure and properties. International Journal of Coal Geology, 57(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2003.08.001

Li, Q., Zhao, C., Chen, X., Wu, W., & Lin, B. (2010). Properties of char particles obtained under O2/N2 and O2/CO2 combustion environments. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification, 49(5), 449–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cep.2010.03.007

Li, S., Ma, X., Liu, G., & Guo, M. (2016). A TG–FTIR investigation to the co-pyrolysis of oil shale with coal. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 120, 540–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2016.07.009

Li, X., Hayashi, J., & Li, C. (2006). FT-Raman spectroscopic study of the evolution of char structure during the pyrolysis of a Victorian brown coal. Fuel, 85(12–13), 1700–1707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2006.03.008

Li, X., Rathnam, R. K., Yu, J., Wang, Q., Wall, T., & Meesri, C. (2010). Pyrolysis and Combustion Characteristics of an Indonesian Low-Rank Coal under O2/N2 and O2/CO2 Conditions. Energy & Fuels, 24(1), 160–164. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef900533d

Lin-Vien, D. (Ed.). (1991). The Handbook of infrared and raman characteristic frequencies of organic molecules. Boston: Academic Press.

Maffei, T., Khatami, R., Pierucci, S., Faravelli, T., Ranzi, E., & Levendis, Y. A. (2013). Experimental and modeling study of single coal particle combustion in O2/N2 and Oxy-fuel (O2/CO2) atmospheres. Combustion and Flame, 160(11), 2559–2572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2013.06.002

Miao, Z., Wu, G., Li, P., Meng, X., & Zheng, Z. (2012). Investigation into co-pyrolysis characteristics of oil shale and coal. International Journal of Mining Science and Technology, 22(2), 245–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2011.09.003

Molina, A., & Shaddix, C. R. (2007). Ignition and devolatilization of pulverized bituminous coal particles during oxygen/carbon dioxide coal combustion. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, 31(2), 1905–1912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proci.2006.08.102

Murphy, J. J., & Shaddix, C. R. (2006). Combustion kinetics of coal chars in oxygen-enriched environments. Combustion and Flame, 144(4), 710–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2005.08.039

Niksa, S., Heyd, L. E., Russel, W. B., & Saville, D. A. (1985). On the role of heating rate in rapid coal devolatilization. Symposium (International) on Combustion, 20(1), 1445–1453. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0082-0784(85)80637-8

Oh, M. S. (1985). Softening coal pyrolysis (Thesis). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved from http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/15245

Ozawa, T. (1965). A New Method of Analyzing Thermogravimetric Data. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan, 38(11), 1881–1886. https://doi.org/10.1246/bcsj.38.1881

Perera, M. S. A., Ranjith, P. G., Choi, S. K., Bouazza, A., Kodikara, J., & Airey, D. (2011). A review of coal properties pertinent to carbon dioxide sequestration in coal seams: with special reference to Victorian brown coals. Environmental Earth Sciences, 64(1), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-010-0841-7

Pielsticker, S., Heuer, S., Senneca, O., Cerciello, F., Salatino, P., Cortese, L., … Kneer, R. (2016). Comparison of pyrolysis test rigs for oxy-fuel conditions. Fuel Processing Technology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2016.10.010

Prinz, D., Pyckhout-Hintzen, W., & Littke, R. (2004). Development of the meso- and macroporous structure of coals with rank as analysed with small angle neutron scattering and adsorption experiments. Fuel, 83(4–5), 547–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2003.09.006

Rathnam, R. K., Elliott, L. K., Wall, T. F., Liu, Y., & Moghtaderi, B. (2009). Differences in reactivity of pulverised coal in air (O2/N2) and oxy-fuel (O2/CO2) conditions. Fuel Processing Technology, 90(6), 797–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2009.02.009

Reich, S., & Thomsen, C. (2004). Raman spectroscopy of graphite. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 362(1824), 2271–2288. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2004.1454

Riaza, J., Khatami, R., Levendis, Y. A., Álvarez, L., Gil, M. V., Pevida, C., … Pis, J. J. (2014). Single particle ignition and combustion of anthracite, semi-anthracite and bituminous coals in air and simulated oxy-fuel conditions. Combustion and Flame, 161(4), 1096–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2013.10.004

Ross, D. (2000). Devolatilisation times of coal particles in a fluidised-bed. Fuel, 79(8), 873–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-2361(99)00227-6

Sakurovs, R., He, L., Melnichenko, Y. B., Radlinski, A. P., Blach, T., Lemmel, H., & Mildner, D. F. R. (2012). Pore size distribution and accessible pore size distribution in bituminous coals. International Journal of Coal Geology, 100, 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2012.06.005

Saucedo, M. A., Butel, M., Scott, S. A., Collings, N., & Dennis, J. S. (2015). Significance of gasification during oxy-fuel combustion of a lignite char in a fluidised bed using a fast UEGO sensor. Fuel, 144, 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2014.10.029

Senneca, O., Apicella, B., Heuer, S., Schiemann, M., Scherer, V., Stanzione, F., … Russo, C. (2016). Effects of CO2 on submicronic carbon particulate (soot) formed during coal pyrolysis in a drop tube reactor. Combustion and Flame, 172, 302–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2016.07.023

Senneca, O., & Cortese, L. (2012). Kinetics of coal oxy-combustion by means of different experimental techniques. Fuel, 102, 751–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2012.05.033

Senneca, O., Salatino, P., & Masi, S. (2005). The influence of char surface oxidation on thermal annealing and loss of combustion reactivity. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, 30(2), 2223–2230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proci.2004.08.156

Sheng, C. (2007). Char structure characterised by Raman spectroscopy and its correlations with combustion reactivity. Fuel, 86(15), 2316–2324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2007.01.029

Shi, L., Liu, Q., Guo, X., Wu, W., & Liu, Z. (2013). Pyrolysis behavior and bonding information of coal — A TGA study. Fuel Processing Technology, 108, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2012.06.023

Singer, S., Chen, L., & Ghoniem, A. F. (2013). The influence of gasification reactions on char consumption under oxy-combustion conditions: Effects of particle trajectory and conversion. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, 34(2), 3471–3478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proci.2012.07.042

Solomon, P. R., Hamblen, D. G., Carangelo, R. M., Serio, M. A., & Deshpande, G. V. (1988). General model of coal devolatilization. Energy & Fuels, 2(4), 405–422. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef00010a006

Solomon, P. R., Serio, M. A., & Suuberg, E. M. (1992). Coal pyrolysis: Experiments, kinetic rates and mechanisms. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, 18(2), 133–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-1285(92)90021-R

Speight, J. G. (2013). The chemistry and technology of coal (3. ed). Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press.

Stark, A. K. (2015, February). Multi-Scale Chemistry Modeling of the Thermochemical Conversion of Biomass in a Fluidized Bed Gasifier (Doctoral Thesis). Massachusetts Institute of Technology, EEUU. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/97774

Strezov, V., Lucas, J. A., Evans, T. J., & Strezov, L. (2004). Effect of heating rate on the thermal properties and devolatilisation of coal. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 78(2), 385–397. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JTAN.0000046105.01273.61

Su, S., Song, Y., Wang, Y., Li, T., Hu, S., Xiang, J., & Li, C.-Z. (2015). Effects of CO2 and heating rate on the characteristics of chars prepared in CO2 and N2 atmospheres. Fuel, 142, 243–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2014.11.025

Thommes, M. (2010). Physical Adsorption Characterization of Nanoporous Materials. Chemie Ingenieur Technik, 82(7), 1059–1073. https://doi.org/10.1002/cite.201000064

Toftegaard, M. B., Brix, J., Jensen, P. A., Glarborg, P., & Jensen, A. D. (2010). Oxy-fuel combustion of solid fuels. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, 36(5), 581–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecs.2010.02.001

Tolvanen, H., & Raiko, R. (2014). An experimental study and numerical modeling of combusting two coal chars in a drop-tube reactor: A comparison between N2/O2, CO2/O2, and N2/CO2/O2 atmospheres. Fuel, 124, 190–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2014.01.103

Tuinstra, F. (1970). Raman Spectrum of Graphite. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 53(3), 1126. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1674108

Valdés, Carlos F., Gloria Marrugo, Farid Chejne, Juan David Román, and Jorge I. Montoya (2016). Effect of Atmosphere Reaction and Heating Rate on the Devolatilization of a Colombian Sub-Bituminous Coal. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 121: 93–101

Wang, B., Sun, L., Su, S., Xiang, J., Hu, S., & Fei, H. (2012). Char Structural Evolution during Pyrolysis and Its Influence on Combustion Reactivity in Air and Oxy-Fuel Conditions. Energy & Fuels, 26(3), 1565–1574. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef201723q

Wang, C., Zhang, X., Liu, Y., & Che, D. (2012). Pyrolysis and combustion characteristics of coals in oxyfuel combustion. Applied Energy, 97, 264–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.02.011

Xu, J., Su, S., Sun, Z., Qing, M., Xiong, Z., Wang, Y., … Xiang, J. (2016). Effects of steam and CO2 on the characteristics of chars during devolatilization in oxy-steam combustion process. Applied Energy, 182, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.08.121

Yan, B.-H., Cao, C.-X., Cheng, Y., Jin, Y., & Cheng, Y. (2014). Experimental investigation on coal devolatilization at high temperatures with different heating rates. Fuel, 117, 1215–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2013.08.016

Yin, C., & Yan, J. (2016). Oxy-fuel combustion of pulverized fuels: Combustion fundamentals and modeling. Applied Energy, 162, 742–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.10.149

Yu, J., Lucas, J. A., & Wall, T. F. (2007). Formation of the structure of chars during devolatilization of pulverized coal and its thermoproperties: A review. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, 33(2), 135–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecs.2006.07.003

Zeng, D., Hu, S., & Sarv, H. (2008). Differences in chars formed from coal pyrolysis under N2 and CO2 atmospheres (p. 12). Presented at the International Pittsburgh Coal Conference 2008, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Zhang, L., Kajitani, S., Umemoto, S., Wang, S., Quyn, D., Song, Y., … Li, C.-Z. (2015). Changes in nascent char structure during the gasification of low-rank coals in CO2. Fuel, 158, 711–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2015.06.014

Zhu, X., & Sheng, C. (2010). Evolution of the Char Structure of Lignite under Heat Treatment and Its Influences on Combustion Reactivity †. Energy & Fuels, 24(1), 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef900531h

Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) Share - Adapt