Motivation Conditions in a Foreign Language Reading Comprehension Course Offering Both a Web-Based Modality and a Face-to-Face Modality

Las condiciones de motivación en un curso de comprensión de lectura en lengua extranjera (LE) ofrecido tanto en la modalidad presencial como en la modalidad a distancia en la web

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n1.36939Keywords:

Comparison, face-to-face modality, foreign language reading, motivation, web-based modality (en)Comparación, lectura en lengua extranjera, modalidad a distancia en la web, modalidad presencial, motivación (es)

Motivation plays an important in role in education. Based on the ten macro-strategies proposed by Dörnyei and Csizér (1998), this article analyzes the motivation conditions in a foreign language reading comprehension course using both a web-based modality and a face-to-face modality. A case study was implemented as the primary research method, and five instruments were used to gather data: observations, a teacher’s diary, focus groups, questionnaires, and in-depth interviews. The use of teaching aids, mastery gains in reading, proper presentation of tasks, and lack of humor were among the similarities found in the courses. In contrast, constant motivation, technical support, interactions among students, anxiety, and a high number of exercises constituted some of the differences between the modalities.

Basados en las diez macro-estrategias propuestas por Dörnyei y Csizér, este artículo analiza las condiciones de motivación en un curso de comprensión de lectura en lengua extranjera ofrecido en las modalidades a distancia en la web y presencial. Se implementó un estudio de caso como método de investigación y se utilizaron cinco instrumentos para recoger la información: observaciones, diario del profesor, grupos focales, cuestionarios y entrevistas a profundidad. El uso de ayudas de enseñanza, la mejora en la lectura, la presentación adecuada de las actividades y la carencia de humor son algunas de las similitudes encontradas en estos dos cursos. En contraste, una motivación más individual y positiva, la interacción entre los estudiantes, la ansiedad y la cantidad de ejercicios se constituyen en algunas diferencias entre las dos modalidades.

PROFILE

Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

Vol. 16, No. 1, April 2014 ISSN 1657-0790 (printed) ISSN 2256-5760 (online)

doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n1.36939

Motivation Conditions in a Foreign Language Reading Comprehension Course Offering Both a Web-Based Modality and a Face-to-Face Modality

Las condiciones de motivación en un curso de comprensión de lectura en lengua extranjera (LE) ofrecido tanto en la modalidad presencial como en la modalidad a distancia en la web

Sergio Lopera Medina*

Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia

This article was received on June 26, 2013, and accepted on October 18, 2013.

Motivation plays an important in role in education. Based on the ten macro-strategies proposed by Dörnyei and Csizér (1998), this article analyzes the motivation conditions in a foreign language reading comprehension course using both a web-based modality and a face-to-face modality. A case study was implemented as the primary research method, and five instruments were used to gather data: observations, a teacher’s diary, focus groups, questionnaires, and in-depth interviews. The use of teaching aids, mastery gains in reading, proper presentation of tasks, and lack of humor were among the similarities found in the courses. In contrast, constant motivation, technical support, interactions among students, anxiety, and a high number of exercises constituted some of the differences between the modalities.

Key words: Comparison, face-to-face modality, foreign language reading, motivation, web-based modality.

La motivación juega un papel importante en la educación. Basados en las diez macro-estrategias propuestas por Dörnyei y Csizér, este artículo analiza las condiciones de motivación en un curso de comprensión de lectura en lengua extranjera ofrecido en las modalidades a distancia en la web y presencial. Se implementó un estudio de caso como método de investigación y se utilizaron cinco instrumentos para recoger la información: observaciones, diario del profesor, grupos focales, cuestionarios y entrevistas a profundidad. El uso de ayudas de enseñanza, la mejora en la lectura, la presentación adecuada de las actividades y la carencia de humor son algunas de las similitudes encontradas en estos dos cursos. En contraste, una motivación más individual y positiva, la interacción entre los estudiantes, la ansiedad y la cantidad de ejercicios se constituyen en algunas diferencias entre las dos modalidades.

Palabras clave: comparación, lectura en lengua extranjera, modalidad a distancia en la web, modalidad presencial, motivación.

Introduction

The prevalence of web-based learning is increasing considerably at the university level due to its greater flexibility and opportunity (Stern, 2004). This increase might be the result of options provided by the advancement of technology and the Internet and mounting pressures caused by an individual’s community, government, and globalization. Thus, faculty members are faced with offering web-based courses and programs to university students.

Some universities have even offered students two options to take web-based courses in order to satisfy the community and government: either a web-based modality or a face-to-face modality. The need to assess the benefits of each modality has become an important task, and the outcomes of a single course offered in these two modalities should be compared and contrasted (Arismendi, Colorado, & Grajales, 2011). The results might guide faculty members to adapt or restructure programs in their educational settings in order to benefit students.

This article aims to compare these motivational conditions based on the ten macro-strategies proposed by Dörnyei and Csizér (1998) in a graduate course called comprensión de lectura para postgrado (reading comprehension for graduate students). This course was offered both in a web-based modality and in a face-to-face modality for foreign language readers at the Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia.

This article begins with a literature review and examines language teaching, motivation, and reading. Then, the context, course, and characteristics of each modality are described, and the methodology is outlined. Finally, findings, conclusions, and limitations are presented at the end of the article.

Review of Literature

Reading

Reading is an interactive process between the writer and the reader. Alyousef (2005) defines reading as “an interactive process between a reader and a text. The reader should interact dynamically with the text with the intention to understand its message” (p. 144). This author also states that the reader must possess two important elements in order to interact with the text: linguistic knowledge and background knowledge. The former involves awareness about the language, including vocabulary, grammatical structures, and tenses. The latter is linked to the familiarity the reader has with the text.

Other authors also support that reading involves a cognitive process (Cassany, 2006; González, 2000; Grabe & Stoller, 2002; Weir, 1993). Students must predict, memorize information for, interpret, pay attention to, and make hypotheses when they decode a written message. Cassany (2006) argues that reading processes are more complex in a foreign language because students may face difficulties with syntax, grammar, vocabulary, or culture; additionally, they usually have to make a greater effort when they are trying to interact with the reading. As a result, it is very important to guide students with reading strategies. Thus, developing a set of reading strategies is very important for learners.

Reading Models

Because reading is an interactive process, readers must use both bottom-up processes and top-down processes. The former are linked to vocabulary and sentences in which readers construct the text from small units (from letters to words, then from words to sentences) (Aebersold & Field, 1997). The latter refer to the application of the text to existing knowledge (historical, cultural, or linguistic). Grabe and Stoller (2002) argue that students need to apply both processes in order to be successful readers.

Reading Strategy Approach

Chamot, Barnhardt, El-Dinary, and Robbins (1999) and Janzen (2001) highlight the importance of teaching explicit reading strategies to students in order to improve their interactions with the text. Reading strategies help learners pay attention to textual cues, overcome difficult situations while reading, and integrate information from the text (Block, 1986). These reading strategies may range from basic (e.g., previewing or scanning) to complex (e.g., inference or summarizing). Janzen (2001) proposed five issues related to the reading strategy approach:

• Explicit discussion of the reading strategies and when to use them.• Demonstration of how to apply a reading strategy (modeling).

• Involvement with the reading in terms of reading aloud and sharing the process while applying the strategies.

• Discussion of the activities in the classroom.

• Practice with the reading material of the course. (p. 369)

Some researchers have used reading strategies in classrooms and concluded that they are useful for learners (Arismendi et al., 2011; Block, 1986; Carrell, 1998; Lopera, 2012; Mikulecky & Jeffries, 2004; Poole, 2009).

Researchers have also compared face-to-face courses to web-based courses in foreign or second language contexts, concentrating on learning styles, reading strategies, beliefs, and forms of assessment (Arismendi et al., 2011; Imel, 1998; National Education Association, 2000; O’Malley, 1999; Paskey, 2001; Smith, Ferguson, & Caris, 2001; Topper, 2007). Regarding motivation, we found only one study that compared and contrasted a face-to-face course to a web-based course in an undergraduate English for academic purposes (EAP) writing course. Rubesch and McNeil (2010) found four major differences in these two modalities: social/interaction, convenience and flexibility, the new/fun/interesting/easy expectation, and the frustration factor.

In Colombia, research in teaching reading as a foreign language has been conducted mainly in face-to-face contexts (Lopera, 2012; López & Giraldo, 2011; Mahecha; Urrego, & Lozano, 2011; Poole, 2009; Quiroga, 2010). Some characteristics have been considered that are related to classroom environments, such as verbal communication in which the teacher leads the learning process, instances in which the teacher changes her/his agenda according to the students’ needs, and variations in her/his use of group techniques (Mejía & Villegas, 2002). In contrast, the role of the students is seen as that of a “recipient” because they are attempting to internalize knowledge, following the instructions and guidance given by the teacher.

On the other hand, web-based education also involves some of the following characteristics. Although the students and teacher do not have any physical contact, their interaction occurs through tools from the course. Students can log in any time they want, and the role of the students is seen to be autonomous. In fact, students are expected to follow the academic instructions given by the teacher, such as reading the instructions, watching a video, surfing the web to find information related to a topic, answering a questionnaire, and adding discussion to a forum, among others. Regarding research on web-based education in Colombia, there are no studies on reading in a foreign language. In other countries, researchers including Anderson (2003), Dreyer and Nel (2003), Murphy (2007), White (1995) have explored the use metacognitive reading strategies in web-based education.

Motivation

Motivation is an essential factor to engage students in being actively involved in foreign or second language learning (Oxford & Shearin, 1994). There are two types of motivation: intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation (Brown, 2001). The former refers to internal rewards, and the main objective is to learn. The latter deals with external rewards in terms of money, prizes, or grades.

Cheng and Dörnyei (2007) argue that motivation “serves as the initial engine to generate learning and later functions as an ongoing driving force that helps to sustain the long and usually laborious journey of acquiring a foreign language” (p. 153). The authors also state that a motivated learner may achieve her/his goals when she/he persists in attaining proficiency, even if that person does not have much of an aptitude for learning a language.

Strategies for Motivation

Crookes and Schmidt (1991), Dörnyei (1994), and Oxford and Shearin (1994) began to analyze motivation from its cognitive aspects and situational factors regarding classroom application in learning language contexts. Dörnyei and Csizér (1998) carried out a research project in which they asked two hundred English teachers in Hungary to rank certain motivational teaching strategies in classrooms. As a result, they gathered ten macro-strategies for motivation, which they called “ten commandments for motivating language learners” (see Table 1).

Motivation in Web-Based Courses

Motivation has mainly been explored in face-to-face contexts (Gregianin & Mezzomo, 2011), whereas in web-based education, researchers have focused on the permanence of students in these courses.

Dutton, Dutton, and Perry (2002), Muilenburg and Berge (2005), and Roblyer (1999) found that many students drop out of on-line courses due to poor motivation. The absence of a learning atmosphere, distant contact among students, self-discipline, isolation, anxiety, and confusion are some of the reasons students are not motivated (Hara & Kling, 2003; Marcus, 2003). However, Cvitkovik and Sakamoto (2009) emphasize that web-based learners need to have certain special features related to their learning strategies and autonomy: strategic competence, self-reflection and involvement in the learning process, activity within the learning environment, and application of a specific technique to a particular task. If learners do not possess all of these features, they become unmotivated.

Hurd, Beaven, and Ortega (2001) list some principles for consideration when teachers are designing web-based courses to encourage motivation and autonomy:

• Students have the option for self-assessment and self-evaluation.

• Students have the opportunity to relate what they already know to what they are learning.

• Students have the possibility to reflect on how they learn.

• Students have the option to experiment with suggested learning strategies.

• Learners have the possibility to transfer what they have learned to other contexts relevant to their needs or interests.

• Students have the option to complete extra practice.

• Learners clearly understand the objectives and feel they have ownership of the course materials.

This guidance can be applied during different stages of the learning process. In fact, Wlodkowski (1978) suggests three different stages for motivational strategies: at the beginning of the learning process, during the learning process, and at the end of the learning process.

• The first stage involves attitudes and needs. Ice-breaking activities, stating clear objectives for the course, and stating what will be required to be successful in the course are examples of motivational strategies for the learning process.

• The second stage involves stimulation and effect. Teachers can use motivational strategies, potentially including learner participation with questionnaires, different styles of presentation, humor, and different forms of class work (in groups, individually, and in class discussion). These strategies should be meaningful to learners.

• The last stage involves competence and reinforcement. Frequent feedback and the communication of progress to learners are important motivational issues for the learning process.

Finally, teachers can guide learners in the use of metacognitive strategies in order to become more autonomous. Planning how to approach a task, monitoring its comprehension, and evaluating progress are some examples of metacognitive activities (Anderson, 2002).

Method

A case study was followed as a research design (Creswell, 2007; Yin, 2003). The research involved the methodology of an exploratory multiple case study, as the researchers wanted to further compare and contrast the motivations of the face-to-face course and of the web-based course using different instruments to gather data (Creswell, 2007; Merriam, 1998; Tellis, 1997; Yin 2003). Participants were asked to sign a consent form stating that their participation was voluntary, and their identities were protected.

Participants

The Teacher

The teacher held a masters degree in teaching foreign languages and had more than ten years of experience teaching face-to-face reading comprehension courses in graduate and undergraduate programs. However, it was his first experience teaching web-based courses, although he was quite motivated to have this experience. The teacher had computer skills and was part of the team who designed the web-course for the research project. For the purpose of this project, the same teacher taught both courses.

The Students

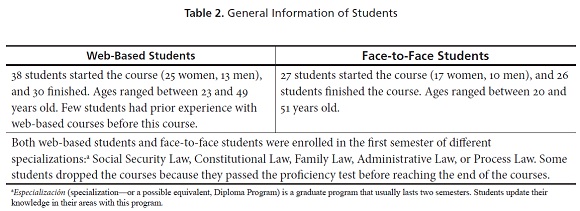

A total of 56 students finished the course in both modalities. Table 2 describes the general information of students.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were gathered using five instruments: questionnaires, observations, in-depth interviews, focus groups, and the diary of the teacher. The purpose of each instrument is explained below.

Questionnaires. Three questionnaires were administered to evaluate the course and teacher, the students’ motivations and reading strategies, and the students themselves. These instruments were analyzed to verify the motivations.

Observations. This technique allows investigators to examine issues, such as behavioral interactions and participation, among others (Brown, 2001). Researchers observed different sessions of classes in the face-to-face course. The chats, forums, e-mails, and exercises of each unit were analyzed in the web-based course.

Focus groups. When the courses finished, the students were invited to participate in focus groups to discuss their academic experiences in a deeper way. Researchers programmed four sessions (two per modality).

Teacher diary. The teacher kept a diary for each modality in English. He recorded all of his observations, thoughts, and reflections about the teaching process. The objective was to build an academic view of the two modalities (Jeffrey & Hadley, 2002).

In-depth interviews. Researchers selected four key respondents (two per modality) in order to validate the information (Berry, 1999). For the selection of students, researchers chose the students who showed the highest and lowest motivations, accordingly.

Context

This study was carried out at Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín-Colombia. Graduate students in specializations are required to certify their reading comprehension in a foreign language in order to be admitted to the second semester of their specializations. Students have two options for this certification: taking a proficiency test or taking a face-face course. A third option was established in 2007 when the EALE (Enseñanza y Aprendizaje de las Lenguas Extranjeras [Teaching and learning of foreign languages]) research group designed a course in order to help web-based graduate students fulfill the foreign language requirement. Two years later, EALE decided to carry out the research project “Effects of Web-Based and Face-to-Face Instruction Modalities in the Reading Comprehension of Graduate Students.” The objective was to compare students’ experiences with the web-based and traditional face-to-face courses.

Description of the Course

Both the face-to-face course and the web-based course followed a reading comprehension program for graduate students that lasted 120 hours. The program was designed to help students apply reading strategies in order to improve the reading comprehension process in foreign language. The course was divided into five units (see Table 3).

The Face-to-Face Course

Students attended the face-to-face course twice a week (Mondays and Wednesdays) from 6 to 9 p.m. The teacher followed the format of a traditional classroom, explaining the topics as the students received the knowledge. He used a video beam, board, examples, demonstrations, and photocopies for his teachings and for the application of reading strategies. He mostly performed the following activities during the classes:

• He told the students the objectives, methodology, evaluation, and the reading topics at the beginning of the course.

• He wrote the agenda and activities for each class.

• He reviewed the topic taught in the previous class.

• He read aloud the readings in English.

• He modeled the reading strategies.

• He asked the students to work in groups in order to apply or practice the reading strategies. Students selected a speaker to share the activities among the groups.

• He gave feed-back on each activity to students.

Finally, in order to clarify instructions or an issue for the students, the teacher used Spanish.

The Web-Based Course

The web-based course was designed using the platform MOODLE (Modular Object-Oriented Dynamic Learning Environment), and the students had to spend 10 hours on it weekly. The course began with an introductory unit, which presented all of the information related to academic issues and to recommendations and sources, including the objectives, evaluation, topics, scheduling of activities, links for reading practice, online dictionaries, and bibliography.

Each unit displayed an introduction of the reading topic, the objective, a mind map, explanations with examples, practice with exercises and workshops, tests, links for extra practice, and bibliography. For the correction and evaluation of the activities, the platform offers two options: automated evaluation and manual evaluation. The former gives the scores and comments instantaneously. The latter takes some time because the teacher has to evaluate the learners’ activities, only then sending a comment and a score. Students may have the option to improve or correct their exercises when the platform is programmed to offer multiple attempts.

MOODLE Platform

MOODLE is the platform used for web-based courses at Universidad de Antioquia. This platform involves a constructivist and social constructionist approach, wherein both the teachers and students participate in and contribute to the interactions in educational settings (Brandl, 2005). The platform offers many advantages for web-based education. It reports each activity completed by students using graphics and details, provides a complete register of user activity, and offers many tools, such as wikis, chats, forums, dialogues, and e-mail integration. Finally, the interface of the platform is simple, efficient, and user-friendly.

Findings

Ten researchers participated in the data analysis (six teachers, three undergraduate students, and an advisor). All researchers examined the data individually in order to find patterns in the different instruments. Then, they labeled and compared some important ideas in order to code and categorize the data. Finally, the researchers used triangulation to validate the data (Freeman, 1998) and translated certain excerpts from Spanish to English.

Based on the macro-strategies proposed by Dörnyei and Csizér (1998), the researchers found several issues concerning motivation.

Proper Teacher Behavior

Both web-based students and face-to-face students stated that the teacher greatly motivated them. A sample of students’ comments about the teachers in the motivation questionnaires can be seen in Table 4.

However, the researchers observed that the teacher was a more constant motivator (Muñoz & González, 2010) in the web-based course than in the face-to-face course. This web-based course was the first experience for most of the students, and they faced difficulties using the tools and submitting the exercises from the platform. This caused demotivation among the students, and the teacher had to stimulate them to participate or give them various opportunities to repeat an exercise.

Recognize Students’ Efforts

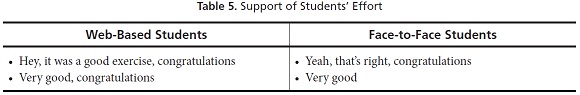

Observers noted that the teacher always monitored the students’ progress and stimulated the students by congratulating them when they completed the exercises in both courses. The teacher typed or used expressions like the ones shown in Table 5.

However, differences emerged regarding grades. Web-based students expressed a high degree of anxiety when they did not receive an automated score from the exercises they had submitted. The teacher had to evaluate some of the exercises manually, and he took some time to do so. Also, the platform did not help by giving students a score of 0.0 while they waited for the teacher’s correction. As a result, the students from the web-based course were quite worried about the results. One of the students expressed in the motivation questionnaire:

Another discouraging situation is that you cannot get the score of an exercise immediately after sending it if it requires review from the teacher; so, you have to wait without knowing if you did it right or wrong.

Promote Learners’ Self-Confidence

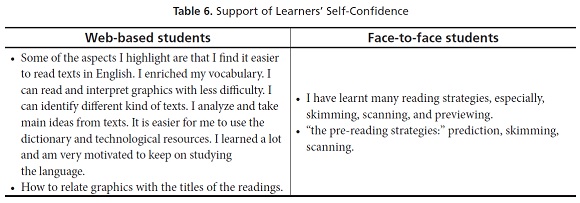

The learning strategies for reading were explicit in both courses. The web-based course offered explanations and examples of each reading strategy. Also, each topic had some links for extra practice with reinforcing explanations and examples. On the other hand, the teacher was observed to introduce, model, and give examples of each reading strategy in the face-to-face course. Students also expressed that they had learned or explored certain learning strategies in their reading. Some of the students’ replies to the self-assessment questionnaire are shown in Table 6.

One of the differences between the modalities was that the web-based course gave more positive individual feedback to students than the face-to-face course. When students submitted each exercise, the platform and the teacher always gave a grade with a positive comment. Comments such as “good job,” “congratulations,” and “it was a good exercise” were given on the platform. In fact, one of the students expressed in the motivation questionnaire:

What motivates me is how direct and personalized the communication is. It is so nice to interact with the teacher; he is always willing to resolve your concerns.

Creating a Pleasant Classroom Climate

Both modalities always followed a traditional format, in which the teacher or the platform presented the topic and gave examples, and then the students were called out to apply or practice the topic being taught. The teacher used a song to reinforce one of the reading topics in the face-to-face course; this was the only different activity for students.

Observers noted that humor was not present in classes but observed that face-to-face students had a more relaxed atmosphere than the web-based students, as the former students smiled among themselves, shared personal issues, and talked about their jobs during some moments of the class. However, this was not the case in the other group, as the web-based learners studied alone and lacked classmates with whom to share personal moments. Hara and Kling (2003) state that web-based students feel a degree of isolation in this modality.

Another difference is the number of the exercises in the web-based course. Students complained about the quantity of exercises designed in the MOODLE platform. One of the students expressed the following in the self-assessment instrument:

There are too many exercises, and we have to do them all. Nevertheless, it is a sacrifice but we have to do them; it is a good idea to have fewer exercises.

However, students had access to the platform at any time of the day, constituting an advantage and a difference compared to the face-to-face course. Osorno and Lopera (2012) reported that the availability of the platform helped learners to “work at any time or place leading to economize time, money, handle family, work, and study at the same time” (p. 50).

Present Tasks Properly

Observers noted that both web-based students and face-to-face students usually followed the provided tasks without any difficulty. Also, they observed that the teacher and the topics presented in the platform were clear and illustrative to students. Students did not usually have questions related to the topic. However, there was a difference in the students from the web-based course, as they encountered questions and difficulties regarding the use of the platform, especially at the beginning of the course. The teacher had to solve some technical questions for the students, such as how to use the tools in the platform, how to log in, how to navigate the platform, and how to submit a task, among others. In his diary, the teacher expressed the following:

I realized that the teacher not only needs to be able to help students through content and grade their activities, but also be able to provide technical support to students on the different issues concerning the platform. (Muñoz & González, 2010, p. 77)

As a consequence, researchers have categorized this new teacher’s role as a technical knowledge expert (Muñoz & González, 2010).

Increase Learners’ Goal-Orientedness

All students had an extrinsic motivation for the course because they had to certify their reading comprehension in a foreign language in order to be admitted to the second semester of their specialization. Few students showed any intrinsic motivation toward the process of learning a foreign language. Some of the students’ answers in the focus group can be seen in Table 7.

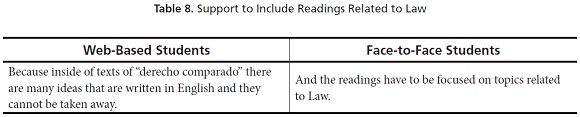

On the other hand, students did express a desire to include readings related to their law field. They argued that it was important to have some contact with materials dealing with the law because some common ideas or expressions are taken from the English language (see Table 8).

Finally, it is worth noting that neither the web-based nor face-to-face students were taken into account when discussing issues such as topics, evaluation, planning, or methodology at the beginning of each modality.

Make the Learning Tasks Stimulating

The presentation of topics was supported by visual or auditory aids in both courses. In the face-to-face modality, the teacher used magazines, images, and video beams to explain the topics. He also read the readings aloud. In the same vein, the topics in the web-based course were accompanied by images and covers of magazines. Most of the readings had audio to be played alongside them. However, there was a difference between the groups. In the face-to-face group, some of the readings dealt with current issues in Colombia, which helped these students better activate their background knowledge than those in the web-based course. One of the face-to-face students expressed the following in the in-depth interview:

Through the readings, we learned about the language and were informed about current issues in Colombia.

Familiarize Learners with L2 Related Values

In both courses, the teacher and students alike noted the benefits of mastering English, in this case, in reading in a foreign language. The students expressed that they had learned how to improve different issues regarding their reading strategies; this issue was constantly found in the diary of the teacher, the focus groups, the questionnaires, and the observations. In fact, some students expressed that they had gained some mastery in reading within the focus groups (see Table 9).

Promote Group Cohesiveness and Group Norms

One of the most important differences dealt with the interactions among students. In the face-to-face group, the students worked together, sharing academic experiences and personal issues. They formed groups to practice and apply the reading strategies they learned, and observers noticed group cohesiveness among the students. Also, the teacher usually asked the students to work in groups in order to practice what he had taught. On the other hand, web-based students always worked individually, and the teacher did not promote interaction among students. Muñoz and González (2010) and Osorno and Lopera (2012) reported that the teacher lacked expertise because it was his first experience in this modality, although he had extensive experience in face-to-face contexts. In some entries of his diary, he expressed that the students did not interact with one another due to their attitudes:

I have the feeling virtual students are not quite willing to participate; they are more concerned on completing the exercises and finishing their activities. (Muñoz & González, 2010, p. 80)

I really believe students could use the forum, the chats, or the e-mails for asking about any doubt they could have; however, the students did not bother.

Still, the researchers took a deeper look at this issue and concluded that the teacher did not ask the students to work in couples or groups. Students only had a few interactions in the chat involving general issues about the course: questions about the platform, feelings on their experience with the modality, deadlines, and evaluation. Collison, Elbaum, Haavind, and Tinker (2000) and Muirhead (2004) suggest that web-based teachers must involve students on an interactional level in order to promote individual, as well as group, work.

Promote Learner Autonomy

There were two important issues related to autonomy: positive self-assessment and lack of self-appropriated learning. The former was supported by the self-assessment questionnaires and focus groups. Students evaluated their learning process in reading positively during the course in both modalities. On the other hand, students did not practice the reading strategies on their own, although they admitted they had learned much. Instead, they did what they were asked to and did not go deeper into the process. This might be a result of the students’ solely extrinsic motivation for taking the course. The following comment taken from one of the observations supports the previous idea:

One of the differences between the groups is that the teacher asked the face-to-face students to peer-assess. He sometimes asked students to evaluate their classmates’ process in a specific reading strategy exercise. However, this did not happen in the web-based course because the teacher never asked students to do it.

Conclusions and Implications

Through the analysis of the ten macro-strategies for motivation proposed by Dörnyei and Csizér (1998), the researchers have identified some similarities and differences between the investigated modalities. Among the similarities were several positive aspects, such as the teacher’s motivation, monitoring, and congratulation of the face-to-face and web-based students. The teacher and the platform also explained, sampled, and used teaching aids for the students. Moreover, the students gained mastery and used reading strategies and techniques when they were engaged with the readings given. However, the researchers also found some negative aspects, including the absence of humor to encourage a more relaxed atmosphere in both modalities. Likewise, most students wanted to pass the courses because their completion was required before registering for the next semester; in other words, most were purely extrinsically motivated. Often, students did not practice reading by themselves, and readings were not related to the field of law. Furthermore, the students were not taken into account when the teachers set up the topics, evaluations, planning, or methodology at the beginning of the courses.

The researchers identified several differences between the modalities. In the web-based course, the teacher was more a constant motivator, provided more positive individual motivation, and gave technical support to the students. However, the teacher did not prompt interactions among the students. Web-based students also showed a high degree of anxiety due to the delays of their evaluations when they were manual. Students also complained about the number of exercises they had to do on the platform. In contrast, the face-to-face students had a more relaxed atmosphere than the web-based students because they had contact with their peers, whereas web-based students worked alone. The teacher used readings related to Colombia, thus drawing upon the students’ background knowledge in this modality. Finally, the face-to-face teachers sometimes asked their students to assess their peers, promoting better group cohesion.

As the use of web-based education in foreign languages is new in Colombia, researchers should offer recommendations based on their experience. First, educational institutions are suggested to provide training programs to prepare foreign language teachers to work in this modality. This measure would help the teachers reflect upon and analyze their roles in education. Second, a third modality in reading as a foreign language teaching could be explored, such as blended learning. This modality would mix some elements of face-to-face education and web-based education (Bartolomé, 2004) in order to take into account the positive and negative aspects of each modality described in this paper. Finally, it would be useful to involve students in topic selection, evaluation procedures, and the evaluation of these courses. It is important to give students the opportunity to define their own personal criteria in order to determine shared group goals.

Limitations

The students showed a high level of extrinsic motivation, as they had to certify their foreign language proficiencies in reading in order to register for the second semester of their graduate program. If the students had not had to certify such a proficiency, the results may have been different. Also, the teacher was a novice in the web-based modality and did not prompt interaction among the students, making analysis of this issue for this modality impossible. Finally, the number of students was limited in this study, and the researchers do not claim that these findings can be generalized to broader contexts.

References

Aebersold, J. A., & Field, M. L. (1997). From reader to reading teacher. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Alyousef, H. S. (2005). Teaching reading comprehension to ESL/EFL learners. The Reading Matrix, 5(2), 143-154.

Anderson, N. J. (2002). The role of metacognition in second language teaching and learning. ERIC Digest. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED463659)

Anderson, N. J. (2003). Scrolling, clicking, and reading English: online reading strategies in a second/foreign language. The Reading Matrix, 3(3), 1-31.

Arismendi, F. A., Colorado, D., & Grajales, L. F. (2011). Reading comprehension in face-to-face and web-based modalities: graduate students’ use of reading and language learning strategies in EFL. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 13(2), 11-28.

Bartolomé, A. (2004). Blended learning: conceptos básicos [Blended learning: Basic concepts]. Píxel-Bit, Revista de Medios y Educación, 23, 7-20.

Berry, R. (1999, September). Collecting data by in-depth interviewing. Paper presented at the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, University of Sussex at Brighton.

Block, E. (1986). The comprehension strategies of second language readers. TESOL Quarterly, 20(3), 463-494.

Brandl, K. (2005). Are you ready to “MOODLE”? Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/vol9num2/review1/review1.htm

Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by principles (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Longman.

Carrell, P. (1998). Can reading strategies be successfully taught? Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 21(1), 1-20.

Cassany, D. (2006). Tras las líneas [Following the lines]. Barcelona, ES: Editorial Anagrama.

Chamot, A., Barnhardt, S., El-Dinary, P., & Robbins, J. (1999). The learning strategies handbook. New York, NY: Longman.

Cheng, H., & Dörnyei, Z. (2007). The use of motivational strategies in language instruction: The case of EFL teaching in Taiwan. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 153-174.

Collison, G., Elbaum, B., Haavind, S., & Tinker, R. (2000). Facilitating online learning. Effective strategies for moderators. Madison, WI: Atwood Publishing.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Crookes, G., & Schmidt, R. W. (1991). Motivation: Reopening the research agenda. Language Learning, 41(4), 469-512.

Cvitkovik, R., & Sakamoto, Y. (2009). Autonomy and motivation in distant learning. Retrieved from http://www.cyber-u.ac.jp/bulletin/0001/pdf/0001_12.pdf

Dörnyei, Z. (1994). Motivation and motivating in the foreign language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 78(3), 273-284.

Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (1998). Ten commandments for motivating language learners: Results of an empirical study. Language Teaching Research, 2(3), 203-229.

Dreyer, C., & Nel, C. (2003). Teaching reading strategies and reading comprehension within a technology-enhanced learning environment. System, 31(3), 349-365.

Dutton, J., Dutton, M., & Perry, J. (2002). How do online students differ from lecture students? JALN, 6(1). Retrieved from http://uwf.edu/atc/Guide/PDFs/how_online_students_differ.pdf

Freeman, D. (1998). Doing teacher research: From inquiry to understanding. Boston, MA: Newbury House.

González, M. C. (2000). La habilidad de la lectura: sus implicaciones en la enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera o como segunda lengua [Reading skills: Implications for the teaching of English as a second or foreign language]. Retrieved from http://www.utp.edu.co/~chumanas/revistas/revistas/rev19/gonzalez.htm

Grabe, W., & Stoller, F. L. (2002). Teaching and researching reading. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Gregianin, M., & Mezzomo, E. (2011). Exploring the influence of affiliation motivation in the effectiveness of web-based courses. International Journal of Web-Based Learning and Teaching Technologies, 6(4), 19-38.

Hara, N., & Kling, R. (2003). Students’ distress with a web-based distance education course: An ethnographic study of participants’ experiences. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, TOJDE, 4(2). Retrieved from http://tojde.anadolu.edu.tr/tojde10/articles/hara.htm

Hurd, S., Beaven, T., & Ortega, A. (2001). Developing autonomy in a distance language learning context: issues and dilemmas for course writers. Systems, 29(3), 341-355.

Imel, S. (1998). Distance learning: Myths and realities. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED426213)

Janzen, J. (2001). Strategic reading on a sustained content theme. In J. Murphy & P. Byrd (Eds.), Understanding the courses we teach: Local perspectives on English language teaching (pp. 369-389). Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Jeffrey, D., & Hadley, G. (2002). Balancing intuition with insight: Reflective teaching through diary studies. The Language Teacher Online, 26(5), 209-212.

Lopera, S. (2012). Effects of strategy instruction in an EFL reading comprehension course: A case study. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 14(1), 79-89.

López, A., & Giraldo, M. C. (2011). The English reading strategies of two Colombian English preservice teachers. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 16(28), 45-76.

Mahecha, R., Urrego, S., & Lozano, E. (2011). Improving eleventh graders’ reading comprehension through text coding and double entry organizer reading strategies. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 13(2), 181-199.

Marcus, T. (2003). Communication, technology, and education: The role of the discussion group in asynchronic distance learning courses as a beneficial factor in the learning process (Unpublished master’s thesis). Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel.

Mejía, M., & Villegas, G. (2002). Campus bimodal: experiencia educativa que conjuga la presencialidad y la virtualidad [Bimodal campus: Educational experience that combines face-to-face and online teaching]. Bogotá, CO: ICFES.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mikulecky, B., & Jeffries, L. (2004). Reading power. United States: Pearson, Longman.

Muilenburg, L. Y., & Berge, Z. L. (2005). Student barriers to online learning: A factor analytic study. Distance Education, 26(1), 29-48.

Muirhead, B. (2004). Encouraging interaction in online classes. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 1(6). Retrieved from http://itdl.org/Journal/Jun_04/article07.htm

Muñoz, J. H., & González, A. (2010). Teaching reading comprehension in English in a distance web-based course: new roles for teachers. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 12(2), 69-85.

Murphy, P. (2007). Reading comprehension exercises online: The effects of feedback, proficiency, and interaction. Language Learning & Technology, 11(3), 107-129. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/vol11num3/pdf/murphy.pdf

National Education Association (2000). A survey of traditional and distance learning higher education members. Retrieved from http://www.nea.org/assets/docs/HE/DistanceLearningFacultyPoll.pdf

O’Malley, J. (1999). Students perceptions of distance learning, online learning, and the traditional classroom. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 2(4). Retrieved from http://www.westga.edu/~distance/omalley24.html

Osorno, J. A., & Lopera, S. (2012). Interaction in an EFL reading comprehension distance web-based course. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 17(1), 41-54.

Oxford, R., & Shearin, J. (1994), Language learning motivation: Expanding the theoretical framework. Modern Language Journal, 78(1), 12-28.

Paskey, J. (2001). A survey compares two Canadian MBA programs, one online and one traditional. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/A-Survey-Compares-2-Canadian/108330/

Poole, A. (2009). The reading strategies used by male and females Colombian university students. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 11(1), 29-40.

Quiroga, C. (2010). Promoting tenth graders’ reading comprehension of academic texts in the English class. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 12(2), 11-32.

Roblyer, M. D. (1999). Is choice important in distance learning? A study of student motives for taking internet-based courses at the high school and community college levels. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 32(1), 157-171.

Rubesch, T., & McNeil, M. (2010). Online versus face-to-face: motivating and demotivating factors in an EAP writing course. The Jaltcall Journal, 6(3), 235-250.

Smith, G., Ferguson, D. L., & Caris, M. (2001). Teaching college courses online vs. face-to-face. T.H.E. Journal. Retrieved from http://thejournal.com/Articles/2001/04/01/Teaching-College-Courses-Online-vs-FacetoFace.aspx

Stern, B. (2004). A comparison of online and face-to-face instruction in an undergraduate foundations of American education course. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 4(2), 196-213.

Tellis, W. (1997). Introduction to case study. The Qualitative Report, 3(2). Retrieved from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR3-2/tellis1.html

Topper, A. (2007). Are they the same? Comparing the instructional quality of online and face-to-face graduate education courses. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 32(6), 681-691.

Weir, C. J. (1993). Understanding and developing language tests. Hemel Hempstead, UK: Prentice Hall.

White, C. (1995). Autonomy and strategy use in distance foreign language learning: research findings. System, 23(2), 207-221.

Wlodkowski, R. J. (1978). Motivation and teaching: A practical guide. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED159173)

Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

About the Author

Sergio Lopera Medina, MA, is currently a PhD student in linguistics and; a specialist in teaching foreign languages. He is a full-time teacher and a research member of EALE (Enseñanza y Aprendizaje de las Lenguas Extranjeras) at Universidad de Antioquia (Colombia). His research interests are including teaching EFL reading comprehension and, compliments in pragmatics.

The findings reported in this article correspond to the final results of the research project “effects of web-based and face-to-face instruction modalities in the reading comprehension of graduate students” sponsored by CODI (code 539), Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia.

References

Aebersold, J. A., & Field, M. L. (1997). From reader to reading teacher. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Alyousef, H. S. (2005). Teaching reading comprehension to ESL/EFL learners. The Reading Matrix, 5(2), 143-154.

Anderson, N. J. (2002). The role of metacognition in second language teaching and learning. ERIC Digest. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED463659)

Anderson, N. J. (2003). Scrolling, clicking, and reading English: online reading strategies in a second/foreign language. The Reading Matrix, 3(3), 1-31.

Arismendi, F. A., Colorado, D., & Grajales, L. F. (2011). Reading comprehension in face-to-face and web-based modalities: graduate students’ use of reading and language learning strategies in EFL. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 13(2), 11-28.

Bartolomé, A. (2004). Blended learning: conceptos básicos [Blended learning: Basic concepts]. Píxel-Bit, Revista de Medios y Educación, 23, 7-20.

Berry, R. (1999, September). Collecting data by in-depth interviewing. Paper presented at the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, University of Sussex at Brighton.

Block, E. (1986). The comprehension strategies of second language readers. TESOL Quarterly, 20(3), 463-494.

Brandl, K. (2005). Are you ready to “MOODLE”? Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/vol9num2/review1/review1.htm

Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by principles (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Longman.

Carrell, P. (1998). Can reading strategies be successfully taught? Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 21(1), 1-20.

Cassany, D. (2006). Tras las líneas [Following the lines]. Barcelona, ES: Editorial Anagrama.

Chamot, A., Barnhardt, S., El-Dinary, P., & Robbins, J. (1999). The learning strategies handbook. New York, NY: Longman.

Cheng, H., & Dörnyei, Z. (2007). The use of motivational strategies in language instruction: The case of EFL teaching in Taiwan. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 153-174.

Collison, G., Elbaum, B., Haavind, S., & Tinker, R. (2000). Facilitating online learning. Effective strategies for moderators. Madison, WI: Atwood Publishing.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Crookes, G., & Schmidt, R. W. (1991). Motivation: Reopening the research agenda. Language Learning, 41(4), 469-512.

Cvitkovik, R., & Sakamoto, Y. (2009). Autonomy and motivation in distant learning. Retrieved from http://www.cyber-u.ac.jp/bulletin/0001/pdf/0001_12.pdf

Dörnyei, Z. (1994). Motivation and motivating in the foreign language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 78(3), 273-284.

Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (1998). Ten commandments for motivating language learners: Results of an empirical study. Language Teaching Research, 2(3), 203-229.

Dreyer, C., & Nel, C. (2003). Teaching reading strategies and reading comprehension within a technology-enhanced learning environment. System, 31(3), 349-365.

Dutton, J., Dutton, M., & Perry, J. (2002). How do online students differ from lecture students? JALN, 6(1). Retrieved from http://uwf.edu/atc/Guide/PDFs/how_online_students_differ.pdf

Freeman, D. (1998). Doing teacher research: From inquiry to understanding. Boston, MA: Newbury House.

González, M. C. (2000). La habilidad de la lectura: sus implicaciones en la enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera o como segunda lengua [Reading skills: Implications for the teaching of English as a second or foreign language]. Retrieved from http://www.utp.edu.co/~chumanas/revistas/revistas/rev19/gonzalez.htm

Grabe, W., & Stoller, F. L. (2002). Teaching and researching reading. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Gregianin, M., & Mezzomo, E. (2011). Exploring the influence of affiliation motivation in the effectiveness of web-based courses. International Journal of Web-Based Learning and Teaching Technologies, 6(4), 19-38.

Hara, N., & Kling, R. (2003). Students’ distress with a web-based distance education course: An ethnographic study of participants’ experiences. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, TOJDE, 4(2). Retrieved from http://tojde.anadolu.edu.tr/tojde10/articles/hara.htm

Hurd, S., Beaven, T., & Ortega, A. (2001). Developing autonomy in a distance language learning context: issues and dilemmas for course writers. Systems, 29(3), 341-355.

Imel, S. (1998). Distance learning: Myths and realities. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED426213)

Janzen, J. (2001). Strategic reading on a sustained content theme. In J. Murphy & P. Byrd (Eds.), Understanding the courses we teach: Local perspectives on English language teaching (pp. 369-389). Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Jeffrey, D., & Hadley, G. (2002). Balancing intuition with insight: Reflective teaching through diary studies. The Language Teacher Online, 26(5), 209-212.

Lopera, S. (2012). Effects of strategy instruction in an EFL reading comprehension course: A case study. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 14(1), 79-89.

López, A., & Giraldo, M. C. (2011). The English reading strategies of two Colombian English preservice teachers. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 16(28), 45-76.

Mahecha, R., Urrego, S., & Lozano, E. (2011). Improving eleventh graders’ reading comprehension through text coding and double entry organizer reading strategies. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 13(2), 181-199.

Marcus, T. (2003). Communication, technology, and education: The role of the discussion group in asynchronic distance learning courses as a beneficial factor in the learning process (Unpublished master’s thesis). Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel.

Mejía, M., & Villegas, G. (2002). Campus bimodal: experiencia educativa que conjuga la presencialidad y la virtualidad [Bimodal campus: Educational experience that combines face-to-face and online teaching]. Bogotá, CO: ICFES.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mikulecky, B., & Jeffries, L. (2004). Reading power. United States: Pearson, Longman.

Muilenburg, L. Y., & Berge, Z. L. (2005). Student barriers to online learning: A factor analytic study. Distance Education, 26(1), 29-48.

Muirhead, B. (2004). Encouraging interaction in online classes. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 1(6). Retrieved from http://itdl.org/Journal/Jun_04/article07.htm

Muñoz, J. H., & González, A. (2010). Teaching reading comprehension in English in a distance web-based course: new roles for teachers. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 12(2), 69-85.

Murphy, P. (2007). Reading comprehension exercises online: The effects of feedback, proficiency, and interaction. Language Learning & Technology, 11(3), 107-129. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/vol11num3/pdf/murphy.pdf

National Education Association (2000). A survey of traditional and distance learning higher education members. Retrieved from http://www.nea.org/assets/docs/HE/DistanceLearningFacultyPoll.pdf

O’Malley, J. (1999). Students perceptions of distance learning, online learning, and the traditional classroom. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 2(4). Retrieved from http://www.westga.edu/~distance/omalley24.html

Osorno, J. A., & Lopera, S. (2012). Interaction in an EFL reading comprehension distance web-based course. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 17(1), 41-54.

Oxford, R., & Shearin, J. (1994), Language learning motivation: Expanding the theoretical framework. Modern Language Journal, 78(1), 12-28.

Paskey, J. (2001). A survey compares two Canadian MBA programs, one online and one traditional. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/A-Survey-Compares-2-Canadian/108330/

Poole, A. (2009). The reading strategies used by male and females Colombian university students. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 11(1), 29-40.

Quiroga, C. (2010). Promoting tenth graders’ reading comprehension of academic texts in the English class. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 12(2), 11-32.

Roblyer, M. D. (1999). Is choice important in distance learning? A study of student motives for taking internet-based courses at the high school and community college levels. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 32(1), 157-171.

Rubesch, T., & McNeil, M. (2010). Online versus face-to-face: motivating and demotivating factors in an EAP writing course. The Jaltcall Journal, 6(3), 235-250.

Smith, G., Ferguson, D. L., & Caris, M. (2001). Teaching college courses online vs. face-to-face. T.H.E. Journal. Retrieved from http://thejournal.com/Articles/2001/04/01/Teaching-College-Courses-Online-vs-FacetoFace.aspx

Stern, B. (2004). A comparison of online and face-to-face instruction in an undergraduate foundations of American education course. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 4(2), 196-213.

Tellis, W. (1997). Introduction to case study. The Qualitative Report, 3(2). Retrieved from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR3-2/tellis1.html

Topper, A. (2007). Are they the same? Comparing the instructional quality of online and face-to-face graduate education courses. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 32(6), 681-691.

Weir, C. J. (1993). Understanding and developing language tests. Hemel Hempstead, UK: Prentice Hall.

White, C. (1995). Autonomy and strategy use in distance foreign language learning: research findings. System, 23(2), 207-221.

Wlodkowski, R. J. (1978). Motivation and teaching: A practical guide. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED159173)

Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Zeynep Ambarkutuk, Brett D. Jones. (2025). Relationships among Students’ Perceptions of Motivational Climate, Course Motivation, and Effort in Undergraduate STEM Courses. Journal for STEM Education Research, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41979-025-00175-y.

2. Melissa Bond, Katja Buntins, Svenja Bedenlier, Olaf Zawacki-Richter, Michael Kerres. (2020). Mapping research in student engagement and educational technology in higher education: a systematic evidence map. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0176-8.

3. DUVAN MOSQUERA. (2023). Teacher-Made Materials Based on Meaningful Learning to Foster Writing Skills.. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 25(1), p.17. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.18825.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2014 Sergio Lopera Medina

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.