Using the Dictionary for Improving Adolescents’ Reading Comprehension of Short Scientific Texts

Uso del diccionario para mejorar la comprensión lectora de textos científicos cortos en inglés con adolescentes

Keywords:

Dictionary use, prior knowledge, reading comprehension, scientific texts (en)Comprensión de lectura, conocimiento previo, textos científicos, uso del diccionario (es)

This paper reports on an innovative and action research project which focused on the use of the dictionary and the prior knowledge of Colombian high school students to improve their reading comprehension of short scientific texts. Data collection instruments included students’ work gathered during two workshops, field notes, and a questionnaire. Findings showed that searching in the dictionary and activating prior knowledge seem to facilitate the use of the text to answer reading comprehension questions. Students experienced less difficulty answering questions that required literal information than those that required establishing relationships among elements of the text. They equally valued the prior knowledge of the subject and the use of the dictionary in the resolution of science workshops in English.

En este artículo se reporta un proyecto de innovación y de investigación-acción centrado en el uso del diccionario y el conocimiento previo adquirido de estudiantes colombianos de secundaria para mejorar la comprensión lectora de textos científicos cortos. Los instrumentos de recolección de datos incluyen el trabajo realizado por los estudiantes durante dos talleres, notas de campo y un cuestionario. Los resultados mostraron que la consulta del diccionario y la activación de conocimientos previos parecen facilitar el uso del texto para responder preguntas de comprensión de lectura. Los estudiantes encontraron menor dificultad en la resolución de preguntas que requerían información literal que en aquellas que implicaban el establecimiento de relaciones entre los elementos del texto.

Using the Dictionary for Improving Adolescents’

Reading Comprehension of Short Scientific Texts

Uso del

diccionario para mejorar la comprensión lectora de textos

científicos cortos en inglés con adolescentes

Ximena Becerra Cortés*

Colegio Saludcoop Norte, Colombia

This article was received on February 1, 2013, and

accepted on July 25, 2013.1

This paper reports on an

innovative and action research project which focused on the use of the

dictionary and the prior knowledge of Colombian high school students to improve

their reading comprehension of short scientific texts. Data collection

instruments included students’ work gathered during two workshops, field

notes, and a questionnaire. Findings showed that searching in the dictionary and

activating prior knowledge seem to facilitate the use of the text to answer

reading comprehension questions. Students experienced less difficulty answering

questions that required literal information than those that required

establishing relationships among elements of the text. They equally valued the

prior knowledge of the subject and the use of the dictionary in the resolution

of science workshops in English.

Key words: Dictionary use, prior

knowledge, reading comprehension, scientific texts.

En este artículo se reporta un proyecto de

innovación y de investigación acción centrado en el uso

del diccionario y el conocimiento previo adquirido de estudiantes colombianos

de secundaria para mejorar la comprensión lectora de textos

científicos cortos. Los instrumentos de recolección de datos

incluyen el trabajo realizado por los estudiantes durante dos

talleres, notas de campo y un cuestionario. Los resultados mostraron que

la consulta del diccionario y la activación de conocimientos previos

parecen facilitar el uso del texto para responder preguntas de

comprensión de lectura. Los estudiantes encontraron menor dificultad en

la resolución de preguntas que requerían información

literal que en aquellas que implicaban el establecimiento de relaciones entre

los elementos del texto. Ellos valoran por igual el conocimiento previo y el uso

del diccionario en la resolución de talleres de Ciencias en

inglés.

Palabras clave:

comprensión de lectura, conocimiento previo, textos científicos,

uso del diccionario.

Introduction

Saludcoop Norte

School is part of the pilot public schools selected by the Secretary of

Education of Bogotá, Colombia, for the implementation of a bilingual

program (Spanish and English). Educational policies argue that in times of

globalization, Colombia needs to develop the capacity of its people to handle

at least one foreign language. Hence, the National Ministry of Education has

formulated the National Bilingual Program 2004-2019. Command

of a second language means, among other things, understanding other contexts

and appropriating knowledge as to generate new knowledge and have access to

more opportunities (Ministerio de Educación

Nacional, 2005).

Taking into

account the previous statement, I as a science teacher have been designing and

applying some workshops in the foreign language related to the science issues

that I have been teaching in Spanish—my students’ mother tongue.

Workshops include the presentation of short scientific texts in English and activities

that involve their reading comprehension, encouraging ninth graders to engage

in the exploration of data, searching for specific information, and the

establishment of general ideas.

However,

despite the belief that scientific vocabulary is easily understood because many

words are very similar in the mother tongue, students have difficulties

understanding the text so they easily stop paying attention to the rest of the

task. Students have difficulties in finding the information needed to carry out

these tasks due to their lack of proficiency in the foreign language as well as

lack of accuracy in scientific vocabulary. Therefore, it is important to guide

students in using strategies to improve their reading comprehension. Among the

strategies recommended to achieve this goal we have the search for meaning of

words within the text and the use of a dictionary for scientific vocabulary (Díaz de León, 1988).

In order to

fulfill the goals of a teacher development program I took in 2010—the

PFPD Red PROFILE2—I decided to dig into

the said problematic situation by engaging in an innovation and action research

project. I opted for encouraging ninth graders at Saludcoop

Norte School, in Bogotá, to work on the decoding of unfamiliar words

using the dictionary as well as their prior knowledge. This strategy aims to

improve reading comprehension of short scientific texts through the

establishment of relations within the knowledge acquired in the mother tongue.

Context

Although the

implementation of the bilingual program at the school is just beginning, there

are many language and cultural difficulties that are very hard to overcome,

especially due to social and economic characteristics surrounding the student

population. However, students’ interest in bilingual education exists.

The School

is located in the Usaquén neighborhood, in the

north of the city. Ninth grade students range from 14 to 17 years of age and

live mostly in extended families (parents, siblings, uncles, grandparents,

cousins). A good number of students reported the absence of either their

fathers or mothers mainly because of abandonment, disappearance, or death. Most

of their families belong to the second and third socioeconomic strata.3 Many of the students are left alone at home and have

to take care of their siblings and do the housework; hence, reading does not

play an important role within their daily routine.

These

students are therefore commonly immersed in the following situations:

1. Students

lack a cultural and academic environment at home that enables parents to

support their academic work.

2. Many

of their homes do not offer the conditions that ensure stability in the

emotional aspect and provide the educational resources necessary for optimal

performance in school.

3. The

surrounding area is primarily an environment of degradation (drugs, thefts, and

assaults are local situations affecting their welfare permanently), which has

an impact on their motivation for schoolwork and their development of a life

plan.

It is

therefore a great challenge faced by teachers to foster an appropriate learning

environment that allows motivating students for academic work. In this case,

providing them with opportunities for effective interaction with texts and

guiding the use of resources to enable them to take advantage of reading and to

acquire language for the appropriate interpretation of information both become

real challenges.

Literature

Review

This section

is intended to provide theoretical support on reading comprehension, reading

scientific texts, vocabulary enrichment, and the use of the dictionary. Here we

concentrate on the meaning of reading comprehension, the characteristics of

scientific texts, the possible types of reading, as well as some

recommendations to improve understanding and deal with the lack of vocabulary

by using the dictionary.

Reading Comprehension

I based my

work on Grellet (1981), who states that

“understanding a written text means extracting the required information

from it as efficiently as possible” (p. 3). Therefore, Grellet mentions that it is essential to take the following

elements into consideration: What do we

read? In this case, we are referring to science text books; Why do we read? We are reading for

information (in order to find out something or in order to do something with

the information); and How do we read?

We are doing intensive reading: reading shorter texts, to extract specific

information.

Scientific Texts

Most of the

information provided in schools has a documentary source: books, articles,

scientific journals, notes, among others. Therefore, it is very important that

students know how to handle these documentary sources and how to make their

reading profit them because academic work is largely based on written

communication. Thus, the acquisition of skills related to reading comprehension

and management of scientific and technical texts allows the scope of better

academic achievements (Díaz de León, 1988).

Given that

some limitations are present for handling documentary information that is used

to inform students of the various advances in science and technology, this

innovation and action research project was intended to develop exercises

through which students could acquire skills that would enable them to achieve a

better text understanding. The scientific literature provides data about

reality. These data have to be judged to be accepted. Also, in science the

documentary sources serve as methodological, practical, and experimental

guidelines, therefore, those who read them should know how to use them for

those purposes (Díaz de León, 1988).

Starting

from an appropriate source material the students can carry out various types of

reading according to their needs: browsing, data search, and reading for

general ideas. Reading comprehension requires bringing into play those skills (Díaz de León, 1988). To do it properly, it is

necessary that the confrontation with the text is done through a constant

awareness of their own capabilities and limitations.

This reading process also requires the use of the elements that the text

provides as clues. The student facing a scientific reading must know what prior

knowledge he or she possesses about the terminology contained in it; if s/he

does not understand it, s/he has to use the same text or a different one to

learn it. The texts can be used in many ways:

• To

follow a sequence of content that progressively becomes more complex.

• To

obtain specific information.

Understanding

a scientific text may be difficult because of the lack of sufficient knowledge

of the subject. Hence, the importance of choosing texts that have an

appropriate level according to what is known about the issue (Díaz de León, 1988).

According to

Alderson and Urguhart (as cited in Calderón, Carvajal, &

Guerrero, 2007), the reading comprehension process focuses on three elements:

the text being read, the background knowledge possessed by the reader, and

contextual aspects.

In everyday

language a word differs from a scientific word, because the first appears in

phrases that can be replaced by different words with the same meaning

(synonyms). The phrase made up of scientific terms cannot admit synonymous

substitutions (Díaz de León, 1988).

Given a new text the reader may discover that language is unknown to him/her

due to vocabulary or terminological difficulties. Vocabulary difficulties

concern the fact s/he does not know the meaning of the word in everyday

language. The terminological difficulties are related to the lack of special

significance that a term in a scientific discipline has (Díaz

de León, 1988). However, if the reader does not understand a word of

ordinary language, s/he can continue to read and extract meaning from the

general context of the sentence and, although there are times in which the

context does not help him, s/he will need to go to the dictionary. The most

common situation is that the meaning of new words from everyday language is

made apparent in the same course of reading. When there are unknown scientific

terms the reader must necessarily find the corresponding definition.

Enrichment of Vocabulary and Use of

the Dictionary

The

dictionary is used when the context does not permit extracting the meaning. So

it is very important to insist that students get used to infer from context the

meaning of the vocabulary as much as possible. They should be advised to resort

to the dictionary, but only in cases where it is really necessary (Fernández de Bobadilla, 1999).

The

acquisition of scientific terms is achieved through the study of the subject

area itself. Introductory texts as well as dictionaries of technical terms can

provide definitions when the context is not enough to get the meaning of

scientific terms. In relation to these terms, students do not usually need to

find them in the dictionary, since they are mostly from Latin or Greek roots

and therefore very similar to those used in their native language (e.g. polychloroprene-policloropreno,

butadiene-butadieno,

spectroscopy-espectroscopía).

The failure to understand the content of the term because of its specificity is

not necessarily a foreign language problem, but a problem of understanding in their own language (Fernández

de Bobadilla, 1999).

In relation

to the information provided by the dictionary, Fernández

de Bobadilla (1999) states that the student must know how to use it, especially

in relation to two main aspects which tend to cause major difficulties in

reading comprehension: the division of entries for meaning and grammatical

category.

Division of Entries by Meaning

A lexical

unit has several meanings. Students tend to associate each lexical unit with a

single meaning. That would not be a problem because the scientific terms often

have a single, precise, and definite meaning. But in some cases we find more

than one entry for a scientific term.

Division of Entries per Grammar

Category

A formal

unit can belong to several grammar categories. Students tend to associate each

word with a single grammatical category. The formal unit belonging to various

categories is not appropriate for scientific terms, but those belonging to

general language.

In data

search reading, the dictionary review is aimed at seeking a term. It is not

necessary to read whole paragraphs; students should be explained that we can

just take a general look at the page of the book to see if the term we want to

find appears there. At this point we have to stop and start with other reading

comprehension strategies (Díaz de León,

1988). Díaz de León adds that the

techniques of speed reading (skimming and scanning) should be applied to the

search for entries, so that the search is carried out quickly.

According to

the literature review, it is clear that reading comprehension of scientific

texts requires intensive reading to extract specific information to resolve

academic problems. Consequently, it is important to develop a methodological

process that assures better understanding while taking into account previously

acquired knowledge, use of context to face unfamiliar foreign and scientific

vocabulary, and the proper use of the dictionary.

Method

Markee (1997) states that

“curricular innovation is a managed process of development whose principal

products are teaching (and/or testing) materials, methodological skills, and

pedagogical values that are perceived as new by potential adopters” (p.

46). The project reported here is an innovation because I wanted to improve the

students’ reading process by guiding them in the use of the dictionary.

This involved the implementation of a methodological process that we had not

done before.

Taking into

account the some considerations about investigation expressed by Calderón (2000), another reason to recognize this

project as an innovation is because it is a reflection that takes place on a

real practical problem that becomes known because of the teaching task.

Innovation in this approach not only involves providing new knowledge and

establishing laws and theories; it also allows us to establish relationships,

formulate hypotheses and dilemmas. In this case, it starts from the difficulty

observed in students in the understanding of short scientific texts in English.

This

innovation also involved carrying out a research exercise with a

students’ group in order to take advantage of the results of

investigations that recommend the use of the dictionary to face scientific

texts and discuss their use in the classroom while taking into account scopes and

limitations within a local context. The processes followed in the innovation

matched the ones that characterize action research because they implied

monitoring its development. To this end, Burns (1999) emphasizes that the

reflexive nature of action research means that analysis occurs over the entire

investigation. Burns (2010) also explains that action research “involves

taking a self-reflective, critical, and systematic approach to exploring your

own teaching contexts . . . it means taking an area you feel could be done

better, subjecting it to questioning, and then developing new ideas and

alternatives” (p. 2).

Closely

related to the alternatives we have to engage in with innovation projects are

the stages claimed in the literature about action research. In Burns (2010), in

particular, we find that action research processes “involve many

interwoven aspects—exploring, identifying, planning, collecting

information, analysing and reflecting, hypothesizing

and speculating, intervening, observing, reporting, writing, presenting (Burns,

1999, p. 35)—that don’t necessarily occur in any fixed

sequence” (p. 8). As can be seen, action research provides a framework

for systematic innovation implementation. All these processes were taking into

consideration and experienced by the teachers participating in the teacher

development program within which this project was carried out.

Alfonzo

(2008) claims that understanding educational innovation as a process requires

certain steps for their uptake and application; these stages are: planning,

diffusion, adoption, implementation, and evaluation. Planning of an innovation is a decision-making process whereby

objectives and procedures are set. Diffusion

is one in which an innovation is made known to its users for their adoption and

use. In the adoption phase the teacher and the educational community decide

whether or not to start educational innovation. Implementation is a series of processes to adapt and implement the

innovative plan in specific situations and, evaluation

consists of getting the value of the whole process in order to come to know the

weaknesses and strengths, the resistance and supports.

According to

the previous statements, in this project, planning meant making decisions about

literature recommendations to face reading comprehension of scientific texts

and how to deal with the dictionary, context, and needs of ninth grade students

to implement the innovation. Diffusion involved creating an appropriate

environment at School for the innovation process. Adoption included adjustments

based on the guidance given by the tutors of the PFPD Red PROFILE who advised me along the development of the

project, the School schedule, and the availability of time and resources, among

others. Implementation involved the selection of appropriate short scientific

texts according to the level of the students and the design and application in

the science class of two workshops with activities specially designed for them.

The evaluation included analysis of the applied workshops. The data were

collected—using a questionnaire and field notes—in order to

identify progress and difficulties and to evaluate the process.

Finally, it

should be noted that the students were asked if they wanted to be part of this

innovation and action research project, and their parents were asked to sign a

consent form in a meeting. This helped me decide which students could be

observed and which evidences from them could be collected and analyzed. Hence,

I gathered data collection from 34 students.

Instruments

As has been

said, data were collected from different instruments: two workshops, a

questionnaire, and field notes.

Workshops

In view of

time available, two workshops were designed and developed in class. They

included the same organization: one short scientific text (a text about

evolution for Workshop 1 and another text about taxonomy for Workshop 2)

followed by activities to promote the use of prior knowledge and the

dictionary. The first activity consisted of reading the text carefully to

recognize and classify the unknown words into scientific words and other words.

The second activity included multiple-choice questions that implied

establishing relationships between prior knowledge presented on these issues in

Spanish and the text presented on the workshop. The third activity focused on

the use of the dictionary to ask for the meaning of selected words from the

text using the dictionary or the context. The fourth activity tapped into

students’ prior knowledge to ask for definitions of scientific words promoting

the use of prior knowledge or context. The final activity included true or

false questions that implied that students established relationships between

different elements of the text (see Appendices A and B).

Questionnaire

A

questionnaire was designed and administered at the end of the two workshops.

They inquired about the students’ points of view and feelings regarding

the activities, difficulties found in decoding the unknown vocabulary using

different resources like the context, previous knowledge and dictionary, and

the advantages and disadvantages of using dictionaries (see Appendix C).

Field Notes

Field notes

were kept to register students’ behaviors and participation during the

application of the workshops.

Data

Analysis

Data were

analyzed based on triangulation processes, which involved resorting to the

literature review and the results of the applied workshops, as evidenced in the

questionnaires and field notes. This was done in order to ensure the

reliability and validity of the research.

Findings

Three

categories emerged after examining the information gathered. They are, namely:

Using the Dictionary, Looking for Information to Define Given Issues, and

Reading Comprehension. The categories and their subcategories are shown in Figure 1 and they are described and discussed below.

Using the Dictionary

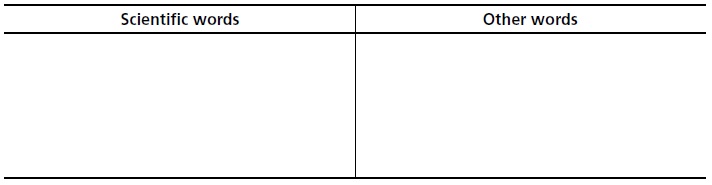

Students were

asked to classify unknown vocabulary from scientific texts into scientific and

nonscientific (Activity 1) terms and to write yes or no if they had used the

dictionary for each word (see Appendixes A and B).

They were

not sure about differences between these words so they expressed many doubts in

Workshop 1. After Workshop 1, a feedback session was done, which allowed among

other things, the consideration of the classifications made by the students and

to clarify terms differences, including correspondence with one or more

meanings as well as general or restricted Science use. Probably because of

that, they felt more confident in Workshop 2 and, as a result, the successful

classification of terms increased from 50% in Workshop 1 to 69% in Workshop 2.

Students were also asked to find the meanings of different

words—scientific and non-scientific terms—by paying attention to

the context or by using the dictionary (Activity 3).

Given the

characteristics of the scientific and non-scientific terms, they were

considered as two subcategories for the analysis. An additional subcategory was

established to review the opinions and feelings of the students about the

search for meanings process.

Scientific Terms

According to

the results obtained by the students, most of the scientific terms achieved

correct recognition percentages (between 78% and 94%). Terms like theory, hypothesis, fossils, were

easily recognizable because they were similar in the students’ native language

(Fernández de Bobadilla, 1999). Also easy to

recognize, but not similar in the native language were: kingdom (using the

context), fertile offspring (using

the dictionary and prior knowledge), traits,

whales (using the dictionary).

For the

translation of scientific terms they found less difficulty in relation to

grammatical categories and entries because these do not accept synonyms (Díaz de León, 1988), but they could not find

some words in dictionaries, for example, phylogeny

and kingdom. On the other hand, they

found difficulties with the translation of compound words (classification system, bottle-nosed

dolphin).

Non-Scientific Terms

Regarding

this issue, I observed students’ results using the dictionary with

non-scientific terms and students’ opinions about the difficulties faced

during the workshops. Students identified non-scientific terms already known by

them and, as a result, they were easily recognized and adjusted to the context.

For example, survive and changes were recognized properly by 91%

of the students.

On the other

hand, in relation to the unknown terms, students had difficulties with

dictionary use when they were trying to find the most appropriate meaning among

the options presented in it. Furthermore, they did not check that the meaning

selected in the dictionary was in accord with the context of the reading. For

example, the word suited was understood as the noun suit = “colección” (collection) by most of the students

and the correct meaning was the verb in passive voice: adaptado. Only 22% of them found

the correct answer because the translation they found was not checked with the

context.

They

reported many difficulties while searching for non-scientific terms like suited, means, called, gathered, known, commonly (that they

extracted from the text). This was evidenced in expressions observed in

Workshop 1 such as “I cannot find this!”, “There are some

meanings!”, “I cannot find the word!”, “The word is not

here!”.4

Fortunately, in Workshop 2 students were more focused and willing to resolve

the activity in an autonomous way using other resources as context and prior

knowledge.

Likes and Dislikes

I got to

know students’ opinions through the questionnaire and the observation

notes. Most of the students recognized that they had difficulties with unknown

words when facing a scientific text in English. For 41% of them, the use of the

context is a useful strategy to find meanings and 47% of them think that even

though they keep on reading, they do not find meanings so they decide to look

in a dictionary. One student wrote: “It is difficult for me but I try to

understand.”

In addition,

students were asked about the use of the dictionary. All of them consider the

dictionary useful but 23% notice that they cannot always find the word that

best corresponds to the text. In relation to the understanding of scientific

texts in English, the opinions of the students were divided: those who

understand the vocabulary (32%), those who have difficulties with the scientific

vocabulary (even in their mother tongue) (29%), and those who have difficulties

with foreign language vocabulary (29%).

Students’

opinions confirm the difficulties to use the context and to appropriately use

the dictionary to find scientific and non-scientific terms. Another important

point was the quality of the dictionaries that they brought to class. Although

the number of suitable dictionaries for the activities increased in Workshop 2,

which suggests students were more aware of the importance of a good dictionary,

some of them were not good enough to resolve the activities.

Looking for Information to Define

Given Issues

Knowledge

acquired in the mother tongue and contexts are useful sources when facing

scientific readings. In this section the use of prior knowledge and context are

analyzed (Activity 4).

Prior Knowledge

Students

answered multiple choice questions concerning information which we had worked

previously in science class, and in their mother tongue (see Appendices A and B). More than 50% of the students

reached correct answers. For example, they easily recognized that

“Charles Darwin was an English naturalist” and that “Cordata is not a kingdom.”

The use of

prior knowledge was useful in the reporting of specific data such as dates and

events, but not as useful when students were required to establish

relationships with the text. In the case of the question, “Traits best

suited” relates to…, the

answer, “helpful variations,” involved understanding the meaning of

the words according to the context. Only four students answered correctly. In

connection to this, we should remember that

The reading

comprehension process focuses on three elements: the text being read, the

background knowledge possessed by the reader and contextual aspects. [Hence],

to comprehend a reading it is necessary that the reader can extract key words

in order to capture the whole sense of the text. (Calderón

et al., 2007, p. 28)

To define

scientific terms in English, students had two chances: using prior knowledge or

using context provided by the readings. Students wrote the use of one of the

two strategies showing prior knowledge preference in both workshops

(percentages averages were 71% and 48%) despite the fact that in the second

workshop around 25% of the population did not write their preference. In

addition I could notice that students used their notes along the development of

both workshops. Although in their notebooks there were no literal definitions,

most students realized that when they define most of the scientific terms they

can use prior knowledge.

Prior

knowledge seems to be useful and students realize it in concepts like reproduce and evolution, in which they reached higher percentages (66 and 53%) of

correct answers. However, in Workshop 1 they had many difficulties defining the

concept of natural selection and only

three students took it from the text. The answer was literal: “Natural

selection means that organisms with traits best suited to their environment are

more likely to survive and reproduce” (see Appendix A).

There were

the same difficulties when defining scientific terms in Workshop 2. Phylogeny, kingdom, and species as natural selection definitions were taken

literally from the text (see Appendix B), but the

students’ percentages of correct answers decreased compared to Workshop 1

(percentage average 27%). Here we saw the importance of creating awareness

among students of the importance of establishing relations between prior

knowledge and context to create definitions because prior knowledge is not

always enough to resolve the task. Alderson and Urguhart

(as cited in Calderón et al., 2007, p. 28)

emphasize that “background knowledge is a helpful tool,” but the

reader has to take in mind the text, to “reorganize his knowledge and put

it together better.”

Contextual Aspects

In general

terms, students improved their performance in Workshop 2 in relation to Workshop

1. According to the percentages of correct answers, students improved in

Activities 1, 2, and 5: in Activity 1: classifying

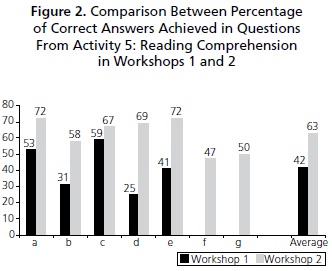

unknown words, from 50% to 69%; in Activity 2: activating prior knowledge, from 52% to 69%; and in Activity 5: reading comprehension, from 42% to 63%.

Activity 3, using the dictionary, was

almost the same (81% and 79%); whereas in Activity 4, defining scientific terms, their performance decreased from 47% to

27%. In this case, the use of prior knowledge proved not to be enough for the

development of appropriate definitions.

Scientific

terms as phylogeny, kingdom, species (present in Workshop 2) and natural selection (in Workshop 1) had in common that they were the

concepts to be defined and with the least number of correct answers. Although

the concepts’ definitions could be taken literally from the text of the

workshop, I could notice that students needed a greater use of the context to

construct definitions.

Reading Comprehension

This section

includes the analysis of the results obtained in the resolution of the last

activity of the two workshops in which students were expected to show their

understanding as well as their likes and dislikes in relation to them.

Decoding the Written Text

For Lopera (2012), “reading is an interactive process in

which the writer and the reader dialog through a text” (p. 85). In my

case, this was enhanced by engaging students in using some reading strategies.

In connection to this, the same author reviews several related studies and

points out that the reading process can be more successful if students receive

strategy instruction. I could observe that activating prior knowledge and

searching in the dictionary seemed to facilitate the use of the text to answer

the questions through which students were expected to signal understanding of

the given texts. In the last activity of the workshops, students were expected

to decode the written text, that is, to extract the underlying meaning from it.

Students’

average of correct answers to the items contained in the last activity was 42%

in Workshop 1, and in two questions they showed percentages above 50%. The

highest percentage was for the item “The Origin of the Species was never

published” (59%). The other item, “When Darwin refers to traits,

this is the same as the individual characteristics,” scored 53% of right

responses. Probably, it could be answered correctly because of the use of the

dictionary. In a previous activity, 72% of the students used the dictionary to

look for the meaning of the word trait,

which proved to be useful, because 84% of the students found the correct

meaning.

Workshop 2

showed the three highest percentages (72%, 72%, and 69%) for three questions

that implied an appropriate use of the context and establishing relations among

different elements of the text as well as taking advantage of the

methodological process of the workshop using dictionary and prior knowledge.

This can be contrasted with Workshop 1, in which the highest percentage reached

59%.

The lowest percentage

found in Workshop 1 was 25% for question 5d. It is likely that this problem is

related to the previous difficulties defining the natural selection concept, because it was literal. In contrast, 47%

was found in Workshop 2, when students answered the question “Man and

bottle-nosed dolphin belong to the same class.” This low percentage was

perhaps due to difficulties in finding the meaning of a compound word.

The above

results confirm that reading scientific texts requires the stakes of skills

that are not restricted to decoding the written text. It is also necessary to

know how to use it to organize the information provided in the resolution of

academic problems (Díaz de León, 1988).

The average

of correct answers increased from 42% in Workshop 1 to 63% in Workshop 2 (see Figure 2). The difference is attributed to a greater use of

context in addition to the prior knowledge in the resolution of questions.

Perhaps this was due to the fact that students took into account the feedback

received in Workshop 1 and that empowered them to improve their results. As can

be seen, the highest number of correct responses was gotten from questions

which required a literal information search within the text, as well as easier

ways to explain why the sentence was true or false. Students were asked to

write arguments, but the frequency of writing was very little. Two questions

presented the highest number of arguments. One of them was the question

“The Origin of the Species was never published,” where five

students wrote not only false but

answers such as “It was published in 1859;” in the other,

“Phylogeny refers to the economical history of

an organism,” six students wrote not only false but explanations such as “It refers to the evolutionary

history.” This question obtained 67% of correct answers (see Figure 2).

Despite the

increase in positive results in Workshop 2, it was observed that most students

were still reluctant to develop arguments in their responses, although in the

feedback provided in Workshop 1, taking this into account was suggested.

Additionally, there were difficulties in establishing relationships between

elements of the text and the true or false sentences, for contrasting ideas or

finding similarities that allowed them to justify their answers or at least

make it explicit in writing. Some students wrote arguments like “I am not

sure,” “I think so,” “It is said in reading,”

“This is in reading.” Although they are not valid arguments, this

could reflect that the requested process is difficult for them and that they

are not aware of its importance because they consider that recognizing the

sentence as true or false is enough.

When

students were asked about their whole understanding, 50% of them considered

that they understood science in Spanish. According to the review of the other

percentages, English understanding reached 12% and science in English

understanding reached 26%. It could be argued that science in English has a

lower degree of difficulty for students than regular English, which would be

contradictory. However, this result could be explained by the satisfaction of

some of the students with the positive results reached in the development of

the workshops, which made them feel empowered to take on challenges.

Likes and Dislikes

A high

percentage of students (86%) expressed they liked having lessons that included

science activities in English. Their responses were as follows: all science

classes (12%), once a week (53%), and once a month (21%). Among the reasons

that justify why they would prefer this once a week, they mentioned the

possibility of improving their English by applying it in different contexts as

well as the enrichment of not only their usual vocabulary but scientific

vocabulary too. They also remarked on the value of the contribution of this

kind of initiatives to science learning which at the same time helps them

improve their English proficiency. Finally, it should be noted that when

students were asked about strategies for improving their understanding to

develop science workshops in English, they recognized and equally valued prior

knowledge of the subjects (44%) and the use of the dictionary (44%).

Limitations

Results of

this innovation are limited and require the implementation of a greater number

of designed and applied workshops to test the significant effectiveness of the

methodological process implemented. Although students showed better performance

in the second workshop and felt comfortable with the methodology, which could

be an indicator of its success, students’ results must be better.

Some

students do not have adequate dictionaries for the development of the

workshops; this difficulty had to be faced through collaborative work with

peers. So, optimized access to resources through checking dictionary

availability for each student before workshops application could have improved

results.

Conclusions

Before this

innovation, when I had applied science workshops in English, students had shown

difficulties decoding information due to a lack of foreign language proficiency

and scientific vocabulary. There had been emphasis on the strategy of the use

of the context to infer missing information but students could not distinguish

the majority of the meanings; therefore, most of the students did not get

involved in the activity and only a few students attempted to perform it. As

far as dictionaries are concerned, they had been requested to develop the workshops;

however, not all the dictionaries were suitable due to factors such as a lack

of appropriate parents’ criteria to buy a dictionary because the lowest

cost is generally decisive in the buying decision. As a consequence,

dictionaries are not always adequate because they handle a small number of

words and limited entries for meanings and grammatical categories. Students

showed difficulties in the use of the dictionary, especially managing the

division of entries: per meaning and per grammatical category. For example,

students tended to consider just the first meaning or they could not find verbs

in the past tense, the passive voice or comparatives.

Along the

development of the project, decoding unknown words presented more difficulties

with non-scientific terms than with scientific terms. This seems to be due to

native language similarities, prior knowledge of terms and difficulties using

dictionaries. Students appreciate the use of the context, the dictionary, and

prior knowledge for the resolution of the science workshops, but strategies

have to be implemented to help or motivate them to improve the use of the

context in reading comprehension in general.

Students

preferred the use of prior knowledge in tasks such as defining scientific

terms. Prior knowledge proves to be useful in the reporting of specific data

such as dates and events and to create some definitions but when this was not

enough to resolve the task; they had difficulties establishing relationships

with it and the context.

The

methodological process of activating prior knowledge and searches in the

dictionary seems to facilitate the use of the text to answer the questions

aimed at checking the students’ understanding. Students’ better

performance in Workshop 2 could be considered an indicator of the success of

the methodology employed by taking in mind feedback given in Workshop 1.

When

students are required to write arguments to support their true or false

responses, they are limited to literal information from the text. There is a

resistance from most of the students to develop arguments regarding their

responses. There are difficulties in establishing relationships between

elements of the text and the true or false sentences and in contrasting ideas

or finding similarities that allow them to justify their answers or at least

make them explicit in writing.

Although we

could implement only two workshops, it was observed that some students had an

optimistic feeling towards the positive results they reached with the

development of the workshops by activating prior knowledge and using the

dictionary. The majority of them assessed the science activities in English in

a positive way due to the fact that they gave them the opportunity to

experience the discovery that English can be applied in different contexts,

enriching not only daily vocabulary but scientific vocabulary and science

learning.

Further

Research

For the

purpose of this study I chose short scientific texts from a science book. But

articles from scientific journals are also documentary sources that are very

important in the science area and so students should know how to handle them.

This is of upmost relevance if we take into account that the academic world is

based largely on written communication (Díaz

de León, 1988).

Considering

that reading requires not only decoding the text also establishing relations

among elements of the text and the activities to be considered, I saw that

students need training in their native language to improve their reasoning

process and, hence, their reading comprehension. In line with this, it is very

important to insist that students get used to inferring the meaning of the

vocabulary from the context as much as possible.

For future

innovations about using the dictionary to improve reading comprehension of short

scientific texts, I recommended exploring not only dictionaries, but also

introductory science texts and technical dictionaries that are recommended in

literature and that could be very useful in familiarizing students with

different sources of information.

1 This paper reports

on a study conducted by the author while participating in the PROFILE Teacher

Development Programme at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá campus, in 2010. The programme was sponsored by Secretaría

de Educación de Bogotá, D. C. Code

number: 1576, August 24, 2009, and modified on March 23, 2010.

2 PFPD stands

for “Programa de Formación

Permanente de Docentes” (Permanent Professional

Development Programme). The Red

PROFILE is a PFPD for schoolteachers. It is run at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, in Bogotá, and motivates

teachers to engage in action research and innovation projects.

3 Colombian

socioeconomic strata are a classification of households from its physical

characteristics and its environment, categorized into six groups with similar social

and economic conditions. Strata 1 and 2 correspond to people with fewer

resources and strata 5 and 6 correspond to people with ample resources.

4

These expressions were translated from Spanish: “¡No

puedo encontrar esto!”; “¡Aquí hay muchos significados!”;

“¡No puedo encontrar la palabra!”; “¡La palabra

no está aquí!”.

5 The original questionnaires were

designed in Spanish and translated into English to comply with the journal

requirements.

References

Alfonzo, F. (2008, November 4). Innovación educativa [Educational innovation.

Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.natureduca.com/blog/?p=237

Biggs, A.,

Daniel, L., Ortleb, E., Rillero,

P., & Zike, D. (2002). Glencoe Science: Life Science. Columbus,

OH: Glencoe/ McGraw-Hill.

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English

language teachers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Burns, A. (2010). Doing action research in English language teaching:

A guide for practitioners. New York, NY: Routledge.

Calderón, J. (2000).

Enseñar a investigar a los profesores: reflexiones y sugerencias didácticas [Teaching teachers to do research:

Didactic reflexions and suggestions. PDF version]. Retrieved from http://publicacionesemv.com.ar/_paginas/archivos_texto/100.pdf

Calderón, S., Carvajal, L. M., & Guerrero, A. Y.

(2007). How to improve sixth graders’

reading comprehension through the skimming technique. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’

Professional Development, 8(1), 25-39. Retrieved from http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/viewFile/10818/11300

Díaz de León, A. E. (1988). Guía de comprensión de

lectura. Textos científicos y técnicos [A guide to reading comprehension.

Scientific and technical texts]. México D.F.,

MX: CONPES. Retrieved from http://www.uamenlinea.uam.mx/materiales/lengua/DIAZ_DE_LEON_ANA_EUGENIA_Guia_de_comprension_de_lectura_Text.pdf

Fernández de

Bobadilla, N. (1999). Hacia un uso

correcto del diccionario en

la lectura de textos científicos en inglés

[Towards a correct use of the dictionary in the reading of scientic

texts in English]. Encuentro: Revista de

Investigación e Innovación en la Clase de Idiomas, 11, 96-105. Retrieved

from http://www.encuentrojournal.org/textos/11.11.pdf

Grellet, F. (1981). Developing reading skills.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lopera, S. (2012). Effects of

strategy instruction in an EFL reading comprehension course: A case study. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’

Professional Development, 14(1), 79-89. Retrieved from http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/view/29057

Markee, N. (1997). Managing curricular

innovation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (2005, October/November). Bases para una

nación bilingüe y competitiva [Foundations

for a competitive and bilingual nation]. Altablero: 37. Retrieved

from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/article-97498.html

About the

Author

Ximena Becerra Cortés has worked

and studied in Colombia. She is a science teacher at Saludcoop

Norte School in Bogotá. She holds a bachelor's degree in teaching

biology from Universidad Pedagógica Nacional and an MS in biology from Universidad de los

Andes.

Appendix A:

Workshop 1. Finding the Meaning of Unknown Words

Name:____________________________________________________________________________

Course: 901

Objective

To promote prior knowledge and dictionary use to

improve reading comprehension.

Science

theme: Evolution, Natural Selection

Activities:

Pre-reading

activity: Read the text carefully and underline the unknown words.

The theory of evolution suggests why there are

differences among living things!

Darwin

developed the theory of evolution that is accepted by most scientists today. He

described his ideas in a book called On

the Origin of Species, which was published in 1859. After many years,

Darwin’s hypothesis became known as the theory of evolution by natural

selection. Natural selection means

that organisms with traits best suited to their environment are more likely to

survive and reproduce. Their traits are passed on to more offspring. The

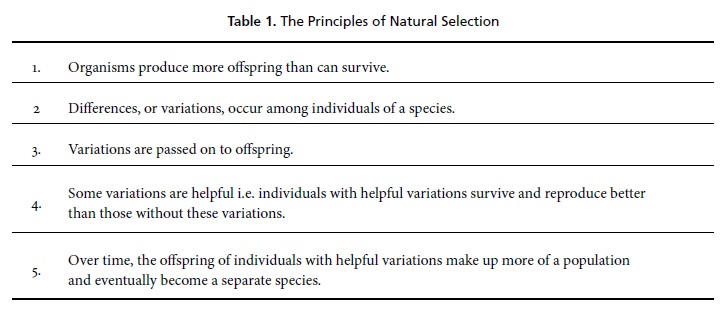

principles that describe how natural selection works are listed in Table 1.

Darwin

developed the theory of evolution that is accepted by most scientists today. He

described his ideas in a book called On

the Origin of Species, which was published in 1859. After many years,

Darwin’s hypothesis became known as the theory of evolution by natural

selection. Natural selection means

that organisms with traits best suited to their environment are more likely to

survive and reproduce. Their traits are passed on to more offspring. The

principles that describe how natural selection works are listed in Table 1.

Over time,

as new data have been gathered and reported, some changes have been made to

Darwin’s original ideas about evolution by natural selection. His theory

remains one of the most important ideas in the study of life science.

English text

adapted from Biggs, Daniel, Ortleb, Rillero, & Zike (2002, p.

157).

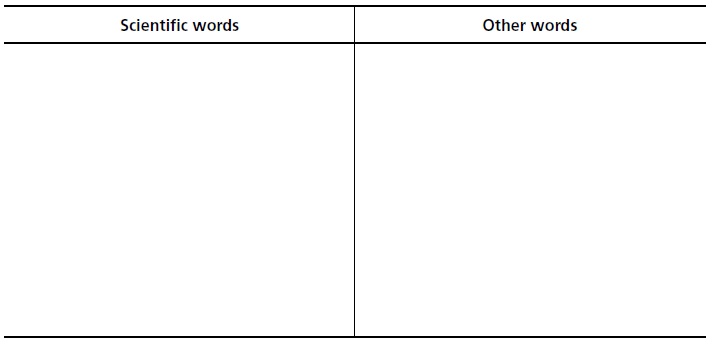

1. Classify

the underlined unknown words into

2. Activating

prior knowledge

Choose the correct option.

a. Charles

Darwin was a(an):

1. French botanist

2. Italian zoologist

3. English naturalist

4. German geologist

b. “Traits

best suited” relates to

1. environment

2. helpful variations

3. organisms

4. offspring

c. Darwin’s

theory has been modified in a modern evolutionary synthesis that is called:

1. neo-Darwinism

2. Darwinism

3. Lamarckism

4. neo-Lamarckism

d. In

2009, in relation to Darwin’s life, a celebration occurred of 200 years

of his

1. birth

2. death

3. publication of On the

Origin of Species

4. beginning of the five year

voyage on the Beagle

3. Using the

dictionary

Find the

meanings of the words (by paying attention to the context or by using the

dictionary).

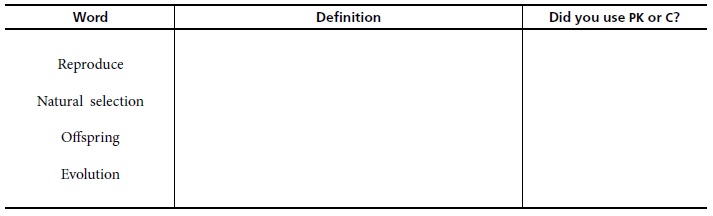

4. Define

the following words using your previous knowledge (PK) or using the context

provided by the reading (C).

5. According

to the text, is the sentence True or False? Why?

a. ______ When

Darwin refers to traits, this is the same as individual characteristics.

b. ______ A hypothesis is the same as a theory.

c. ______ The

Origin of the Species was never published.

d. ______ Natural

selection means that organisms with traits not suited to their environment are

more likely to survive and reproduce.

e. ______ Offspring

of individuals with helpful variations number more than offspring without these

helpful variations.

Appendix B:

Workshop. Understanding Scientific Texts

Name:_____________________________________________________________________________

Course: 901

Objective

To promote prior knowledge and dictionary use to

improve reading comprehension.

Science theme: Taxonomy

Activities:

Pre-reading

activity: Read the text carefully and underline the unknown words.

Modern Classification System

In the late eighteenth century, Carolus Linnaeus, a Swedish naturalist,

developed a new system of grouping organisms. His classification system was

based on looking for organisms with similar structures. Today studies about

fossils, hereditary information and early stages of development are used to

determine an organism’s phylogeny.

In the late eighteenth century, Carolus Linnaeus, a Swedish naturalist,

developed a new system of grouping organisms. His classification system was

based on looking for organisms with similar structures. Today studies about

fossils, hereditary information and early stages of development are used to

determine an organism’s phylogeny.

Phylogeny is

the evolutionary history of an organism, or how it has changed over time. Today

it is the basis for the classification of many organisms.

A

classification system commonly used today groups

organisms into five kingdoms. A kingdom is the first and largest category.

Kingdoms can be divided into smaller groups. The smallest classification

category is a species. Organisms that belong to the same species can mate and

produce fertile offspring. To understand how an organism is classified, look at

this classification of the bottle-nosed dolphin:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Mammalia

Order: Cetacea

Family: Delphinidae

Genus: Tursiops

Species: Tursiops truncates

The classification of the bottle-nosed dolphin shows that it falls under

the order Cetacea. This order includes whales and

porpoises.

English text adapted from Biggs et al. (2002, p. 23).

1. Classify

the underlined unknown words into

2. Activating

prior knowledge

Choose the best option.

a. This is not a kingdom

1. Plantae

2. Protists

3. Cordata

4. Bacteria

b. Carolus Linnaeus was born in

1. 1607

2. 1707

3. 1807

4. 1907

c. Carolus Linnaeus is often called the father of

1. Genetics

2. Chemistry

3. Taxonomy

4. Zoology

d. The binomial nomenclature is

used for naming

1. Families

2. Species

3. Kingdom

4. Orders

3. Using

the dictionary

Find the meaning of the words (by paying attention to the context or by

using the dictionary).

4. Define the following words using

your previous knowledge (PK) or using the context provided by the reading (C).

5. According

to the text, is the sentence True or False? Why?

a. _____ Carolus

Linnaeus developed a new classification system based on organisms’

structures.

b. _____ Fossils are helpful to determine

an organism’s phylogeny.

c. _____ Phylogeny refers to the economical history of an organism.

d. _____ The

five kingdoms are bacteria, protista, fungi, plantae, and animalia.

e. _____ A Species is a group of

organisms that can mate and produce fertile offspring.

f. _____ Man and the bottle-nosed dolphin

belong to the same class.

g. _____ Whales, dolphins, and porpoises

belong to the same family.

Objective

To learn students’ opinions about the advantages and disadvantages

of using dictionaries, the quality of the workshops, the difficulties found in

decoding the unknown vocabulary using different resources, and their points of

view about the activities.

Dear Student:5 The purpose of this

questionnaire is to get your feedback on activities in science class related to

decoding unfamiliar words in English and Spanish and using the dictionary to

improve reading comprehension of scientific texts.

Mark with an X the answer that best fits your views. Your sincerity will

be of great help to us.

1. How

often would you like to develop science in English activities in science

classes?

a. All

classes

b. Once

a week

c. Once

a month

d. Never

e. Other,

which one? _______________________________________________________________

Why?__________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

2. Do you

think…

a. You

understand English?

b. You

understand science?

c. You

understand science in English?

d. Other.

Which one? _______________________________________________________________

3. When you

face a scientific text in English:

a. You

understand everything.

b. You

have difficulties with some words, but you keep on reading and you find their

meaning.

c. You

have difficulties with some words and even though you keep on reading you do

not find their meaning, so you decide look them up in a dictionary.

d. You

have difficulty understanding despite implementing the strategies above.

e. Other.

Which one? _______________________________________________________________

4. Understanding

scientific texts in English.

a. It

is easy. I understand scientific words and other words.

b. I

have difficulties with scientific words and although they are similar to

Spanish words, I do not understand their meaning.

c. It

is difficult because I do not understand many words in the text whether or not

they are scientific, since they are in English.

d. Other.

Which one? _______________________________________________________________

5. To use the

dictionary is:

a. Useful,

because I choose the word that best corresponds taking

into account the context.

b. Not

always useful, because I cannot always find the word that best corresponds to

the context.

c. Useless,

because I do not always find the meaning of the words that I look for.

6. Understanding

and developing science workshops in English is easier when:

a. I

have previously worked on the same topic in Spanish.

b. I

have a dictionary.

c. Other?

Comments________________________________________________________________________________

References

Alfonzo, F. (2008, November 4). Innovación educativa [Educational innovation. Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.natureduca.com/blog/?p=237

Biggs, A., Daniel, L., Ortleb, E., Rillero, P., & Zike, D. (2002). Glencoe Science: Life Science. Columbus, OH: Glencoe/ McGraw-Hill.

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Burns, A. (2010). Doing action research in English language teaching: A guide for practitioners. New York, NY: Routledge.

Calderón, J. (2000). Enseñar a investigar a los profesores: reflexiones y sugerencias didácticas [Teaching teachers to do research: Didactic reflexions and suggestions. PDF version]. Retrieved from http://publicacionesemv.com.ar/_paginas/archivos_texto/100.pdf

Calderón, S., Carvajal, L. M., & Guerrero, A. Y. (2007). How to improve sixth graders’ reading comprehension through the skimming technique. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 8(1), 25-39. Retrieved from http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/viewFile/10818/11300

Díaz de León, A. E. (1988). Guía de comprensión de lectura. Textos científicos y técnicos [A guide to reading comprehension. Scientific and technical texts]. México D.F., MX: CONPES. Retrieved from http://www.uamenlinea.uam.mx/materiales/lengua/DIAZ_DE_LEON_ANA_EUGENIA_Guia_de_comprension_de_lectura_Text.pdf

Fernández de Bobadilla, N. (1999). Hacia un uso correcto del diccionario en la lectura de textos científicos en inglés [Towards a correct use of the dictionary in the reading of scientic texts in English]. Encuentro: Revista de Investigación e Innovación en la Clase de Idiomas, 11, 96-105. Retrieved from http://www.encuentrojournal.org/textos/11.11.pdf

Grellet, F. (1981). Developing reading skills. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lopera, S. (2012). Effects of strategy instruction in an EFL reading comprehension course: A case study. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 14(1), 79-89. Retrieved from http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/view/29057

Markee, N. (1997). Managing curricular innovation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (2005, October/November). Bases para una nación bilingüe y competitiva [Foundations for a competitive and bilingual nation]. Altablero: 37. Retrieved from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/article-97498.html

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2013 Ximena Becerra Cortés

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.