The Role of Collaborative Work in the Development of Elementary Students’ Writing Skills

El papel del trabajo colaborativo en el desarrollo de las habilidades de escritura de estudiantes de primaria

Keywords:

Collaborative learning, writing in elementary school, writing process (en)Aprendizaje colaborativo, escritura en primaria, proceso de escritura (es)

We report the findings of a two-phase action research study focused on the role of collaborative work in the development of elementary students’ writing skills at a Colombian school. This was decided after having identified the students’ difficulties in the English classes related to word transfer, literal translation, weak connection of ideas and no paragraph structure when communicating their ideas. In the first phase teachers observed, collected, read and analyzed students’ written productions without intervention. In the second one, teachers read about and implemented strategies based on collaborative work, collected information, analyzed students’ productions and field notes in order to finally identify new issues, create and develop strategies to overcome students’ difficulties.

Presentamos los resultados de una investigación-acción sobre el papel del trabajo colaborativo en el desarrollo de habilidades de escritura de estudiantes de primaria en una escuela colombiana. El estudio se realizó tras haber identificado las dificultades de los alumnos en las clases de inglés relacionadas con la transferencia de palabras, la traducción literal, la débil conexión de las ideas y la falta de estructura del párrafo al comunicar sus ideas. En la primera fase los docentes observaron, recogieron, leyeron y analizaron las producciones escritas de los alumnos sin realizar ninguna intervención pedagógica. En la segunda, los profesores leyeron sobre estrategias de trabajo colaborativo y las implementaron.

The Role of

Collaborative Work in the Development of Elementary Students’ Writing

Skills*

El papel del trabajo colaborativo en el desarrollo de las habilidades de escritura de estudiantes de primaria

Yuly Yinneth Yate González*

Luis Fernando Saenz**

Johanna Alejandra Bermeo***

Andrés Fernando Castañeda Chaves****

Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas, Colombia

* yuly.yate@sanboni.edu.co

** luis.saenz@sanboni.edu.co

*** johale238@yahoo.com

**** andres.castaneda@sanboni.edu.co

This article

was received on July 1, 2012 and accepted on January 12, 2013.

In this

article we report the findings of a two-phase action research study focused on

the role of collaborative work in the development of elementary students’

writing skills at a Colombian school. This was decided after having identified

the students’ difficulties in the English classes related to word

transfer, literal translation, weak connection of ideas and no paragraph

structure when communicating their ideas. In the first phase teachers observed,

collected, read and analyzed students’ written productions without

intervention. In the second one, teachers read about and implemented strategies

based on collaborative work, collected information, analyzed students’

productions and field notes in order to finally identify new issues, create and

develop strategies to overcome students’ difficulties. Findings show

students’ roles and reactions as well as task completion and language

construction when motivated to work collaboratively.

Key words: Collaborative learning, writing in elementary school, writing process.

Presentamos

los resultados de una investigación-acción llevada a cabo en dos

fases, centrada en el papel del trabajo colaborativo en el desarrollo de

habilidades de escritura de estudiantes de primaria en una escuela colombiana.

El estudio se realizó tras haber identificado las dificultades de los alumnos

en las clases de inglés relacionadas con la transferencia de palabras,

la traducción literal, la débil conexión de las ideas y la

falta de estructura del párrafo al comunicar sus ideas. En la primera

fase los docentes observaron, recogieron, leyeron y analizaron las producciones

escritas de los alumnos sin realizar ninguna intervención

pedagógica. En la segunda, los profesores leyeron sobre estrategias de

trabajo colaborativo y las implementaron; recopilaron información,

analizaron las producciones textuales de los estudiantes y las notas de campo

tomadas para identificar nuevos problemas, crear y desarrollar estrategias que

ayudaran a los estudiantes a superar sus dificultades. Los hallazgos muestran

cómo reaccionaron los estudiantes ante el trabajo colaborativo, y

asimismo la forma como realizan tareas y construyen su lenguaje cuando

están motivados a trabajar de esta manera.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje colaborativo, escritura en primaria, proceso de escritura.

Introduction

This research project seeks to examine the role of

collaborative work in the development of elementary students’ writing

skills in their English classes at the Corporación

Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas. Taking into account

that elementary school students have not yet started their formal writing

process in English, we assessed students to determine their current standing on

their ability to write and what they implemented when composing written tasks.

Through this, the elementary language teachers would develop the necessary

strategies to help students improve and create solid bases for an accurate

writing process, as well as establish departure points to improve upon in the

years to come.

The authors of this article, who worked in grades 2,

3, 4 and 5, decided to work together in order to find strategies to help

students when writing due to an observation made on the performance of

elementary students for at least a year. We noticed some difficulties when

students wanted to write their ideas in English such as transferring words and

expressions from Spanish (using literal translation), reduced or basic vocabulary,

weak connection of ideas and no paragraph structure. Also, most of the students

showed a lack of interest and were reluctant to compose single sentences (a

simple task) as well as get involved in longer assignments.

Many authors have written about the benefits of

writing throughout history, remarking on its power and its ability to convey

knowledge and ideas (MacArthur, Graham, & Fitzgerald, 2006). Besides, it

allows people to express their points of views by making their thinking visible

as well as promotes the ability to ask questions, helps others to provide

feedback and demonstrates their intellectual flexibility and maturity, among

others. On the other hand, collaborative authoring or writing can be defined as

the set of activities involved in the production of a document by more than one

author (Dillon, 1993). Taking this information about writing and collaborative

authoring into account, we try to demonstrate with the following research

project the effect of collaborative work as a tool for developing writing

skills in elementary students.

Theoretical Framework

Focusing on the objective of this investigation, we

approached our research with our focus aimed at three key aspects of study:

collaborative learning, the writing process and the development of writing

skills in elementary (primary) school.

Collaborative Learning

As stated by Smith and Macgregor (1992),

Nowadays, Collaborative Learning is seen as a powerful tool that provides meaningful experiences for students and teachers, in which learning as a group is the motor that impulses other learning processes. In this type of techniques, teachers are not the ones that possess all the knowledge, and their only purpose is to transmit and reproduce that knowledge, but teachers are considered as promoters of experiences where students discover functionalities in what they learn, share with other and apply that knowledge to their real life.

From a collaborative sense, the real meaning of this technique is not only the generation of students’ encounters in which they are given a task to develop, but also are given the opportunity to give opinions, self-correction and peer correction as tools to promote tolerance and idea-sharing, planning projects, among other important benefits of Collaborative Learning. (p. 1)

These are some features of collaborative learning that

we would like to highlight, as mentioned by Smith and Macgregor (1992):

- Learning is an active process

in which all of its participants provide meaningful ideas for projects to

be carried out.

- Learning depends on rich

contexts in which students can feel more interested in working as teams

with clear goals to achieve.

- Learners are diverse, meaning

that every participant may have different ideas, opinions and points of

view that can change or improve the project development. (p. 1)

As for education, collaborative learning has developed

certain roles and values that we as teachers have to promote in our students

when working in collaborative environments (Smith & Macgregor, 1992). These

values are later turned into earnings for students. First, collaborative work

involves all the participants and makes them work as a team in which the

direction of the project is unique. Second, learners learn how to cooperate

among themselves, where work is not seen as an individual product, but it is a

process in which the participants’ ideas influence and have a positive

impact on the project, so the participants’ contributions are relevant

and necessary. And finally, civic responsibility is learnt through the

experience on collaborative learning; with this, students comprehend that the

world is an enormous field in which some abilities are required to become a

successful professional, such as cooperation, working with others, sharing

ideas, comparing and contrasting opinions, defining goals, searching for

strategies to achieve those goals, and learning from on-hand experience. These

previous elements of collaborative learning have shown that learning, seen as

an integral process, requires more than knowledge transferred from the teacher;

it also requires experience that is learnt through working with others.

The Writing Process

According to Long and Richards (1990), the writing

process has been an interesting field for educational researchers, linguists, applied

linguists, and teachers since the early 1970s (Long & Richards, 1990),

giving as results, numerous projects done in the field, identifying different

aspects of this skill in L1 and L2 and their relationship. In the United

Kingdom, for example, researchers such as Britton, Burgess, Martin, Macleod,

& Rosen (1975) observed young learners in the process of writing in order

to identify the planning, decision making and heuristics they employed.

Complementary work in the United States by researchers and educators such as Eming, Murray and Graves (cited in Long & Richards,

1990, p. viii) led to the emergence of the “process” school of

writing theory and practice. This view emphasizes that writing is a recursive

rather than a linear process, that writers rarely write to a preconceived plan

or model, that the process of writing creates its own form and meaning

(depending on the writers’ intention, beliefs, culture, etc.), and that

there is a significant degree of individual variation in the composing behaviors

of both first and second language writers (Long & Richards, 1990).

Flower and Hayes, and Bereiter

and Scardamalia (cited in Myles, 2002) proposed some

writing process models that have served as the theoretical basis for using the

process approach in both L1 and L2 writing instruction. By incorporating

pre-writing activities such as collaborative brainstorming, choice of

personally meaningful topics, strategy instruction in the stages of composing,

drafting, revising, and editing, multiple drafts and peer-group editing, the

instruction takes into consideration what writers do as they write. Attention

to the writing process stresses more a workshop approach to instruction, which

fosters classroom interaction, and engages students in analyzing and commenting

on a variety of texts. The L1 theories also seem to support less teacher

intervention and less attention to form.

At the Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas, the L2 writing

process is one of the skills students must develop in their academic performance.

Taking into account the nature of our curriculum, we feel writing is an ongoing

process students must follow according to a variety of stages of prewriting,

drafting, editing and rewriting and finally publishing, varying its levels of

difficulty among the grades.

Writing Skills Among

Elementary Students

Primary school teachers have been evaluating the

importance of writing from the early ages at school throughout many years. Our

main concern as EFL teachers yields on how to initiate students from primary

levels into the second language writing process and how farther they should go

by the end of each school year.

What our research project is looking for basically is

how to develop students’ writing skills in a collaborative environment,

so they can build up the bases and structures to reach good results in academic

terms. However, according to Hillocks (1986), we should examine the giving of

instructions rather than the way in which we approach students to work in

writing. Bazerman (2007) states that

We as teachers need to face three dimensions and challenges for the teaching of writing: the first one talks about the continuing of writing, the second mentions the complexity of writing and the third one makes reference to writing as a social activity. (p. 293)

Writing as a social activity implies working on tasks

where all students can surely be involved in imaginative and creative topics in

which writing is seen as a social dialogue (Dyson, 2000) as well as a peer

collaboration in the classroom (McLane, 1990). Additionally, writing is a way

to interact, share and move further into processes at early ages (Kamberelis, 1999). Due to all of the above, we can connect

our collaborative writing research project to a social writing environment,

engaging and encouraging children to link the classroom activities with real

life. Doing so, we can help students to enjoy and become more motivated towards

writing.

Considering the previous issues, we came to be

concerned about the lack of interest students have in writing, and the

difficulties concentrating on main ideas; these difficulties can be identified

as not being concise and precise when expressing opinions, not using the

correct vocabulary for the activity as well as not keeping track of punctuation,

and not having coherence and cohesion when writing.

Context

The population we took into account was the elementary

students from Corporación Colegio

San Bonifacio de las Lanzas, a private bilingual school with an English class

intensity of seven (7) hours per week and a total of 536 students. It is

located in the city of Ibagué (Colombia) and

serves students of the middle-high socioeconomic status.

School Description

With 26 years of experience, the school is one of the

most important educational institutions in the region and it is also known

throughout the whole country because of its high academic performance shown in

the results of national tests and because our eleventh grade students rank in

the highest levels based on the standards of the European Council (Council of

Europe, 2001).

Taking a brief look at the overall framework of the

School Institutional Project (Proyecto Educativo Institucional = PEI)

regarding the use of a foreign language, it states that the mastering of

English as a second language is the main objective of the school. Also, the

school is engaged in the intensive learning of the language of globalization as

a way to promote the school and its student body internationally. Hence, the

School Institutional Project explains that mastering a second language is the

minimum standard to be met for educational institutions (Corporación

Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas, 2011).

The school has about 75 teachers in areas such as

science, social studies, mathematics, English, physical education, arts and

language arts. On the other hand, the student population comprises pre-school,

elementary, junior high and high school students. In addition to the English

class intensity of 7 hours per week, mathematics and science are oriented in

this foreign language as well.

Population Description

There are 2 courses per grade in elementary: two

second, third, fourth and fifth grades, with a minimum of 18 and a maximum of

29 learners in each classroom. Their ages range from 7 to 12 years old, with

varied English language skills due to their previous knowledge learnt from

preschool within the institution. The population taken into account consists of

8 students per level, that is to say, 4 students from grade 2A, 4 students from

grade 2B, 4 students from 3A, 4 students from grade 3B; 4 students from 4A, 4

students from grade 4B; and 4 students from 5A, and 4 students from grade 5B,

all selected at random.

Elementary students start developing their writing and

reading skills in second grade at a basic level, that is to say, reading and

writing very short but structured single sentences. After that, moving to third

grade, they start with the production of simple paragraphs, being encouraged to

give opinions and to start developing independent sentences and short

paragraphs. Teachers always support and help students to improve their

performance including writing skills; this process moves forward and gets more

rigorous along with students’ elementary school life.

The institution’s commitment is to develop a bilingual

education. Likewise, and taking into account that Spanish is the L1 of our

students and that their processes in learning a second language can be

difficult for them to be developed with authenticity in our context (as they

are with learning L1), we find the institution’s commitment is to develop

a step-back process, that is, ensuring that the oral and written linguistic

skills in their native language are developed first, and then move on to the

process of learning a second language.

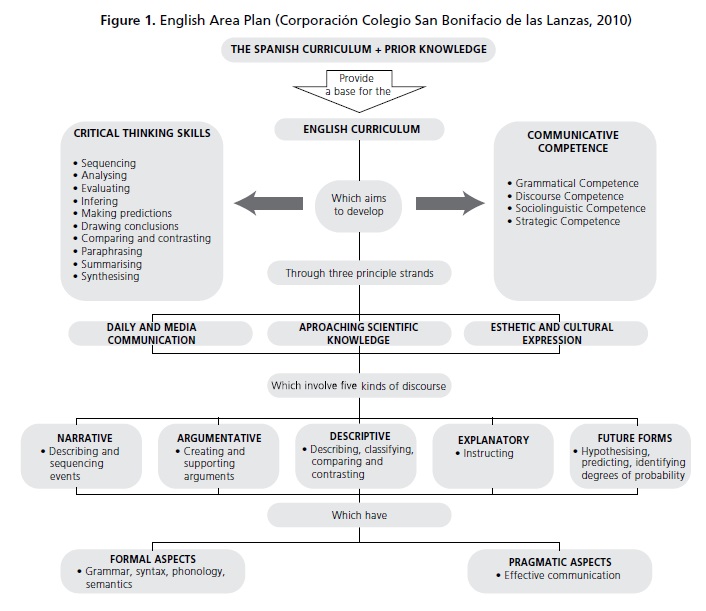

Taking that into account, we know the Spanish

curriculum and the students’ prior knowledge con-tribute to a base for

the English curriculum, which aims to develop critical thinking skills

(sequencing, analyzing, inferring, summarizing, etc.) and communicative competences

(grammatical, discursive, sociolinguistic and strategic) through three

principal strands which are the daily and media communication, approaching

scientific knowledge and aesthetic and cultural expression. These involve five

kinds of discourse which are the narrative, argumentative, descriptive,

explanatory and future forms; these are composed of the formal aspects of the

language like grammar, syntax, phonology, semantics and the use of language in

order to achieve effective communication (see Figure 1).

As we can see from the last lines, more than learning

a second language, the approach at San Bonifacio

School consists of the effective use of English in real contexts by developing

several skills through elements like authentic performances and learning for

understanding. All the elements mentioned above along with collaborative work

will help students reach their goal, in this case, when writing.

Research Design

This is a study based on the principles of action

research and is carried out in a descriptive-innovating manner in which we

examined the main contributions of collaborative work in primary students in

the development of writing skills.

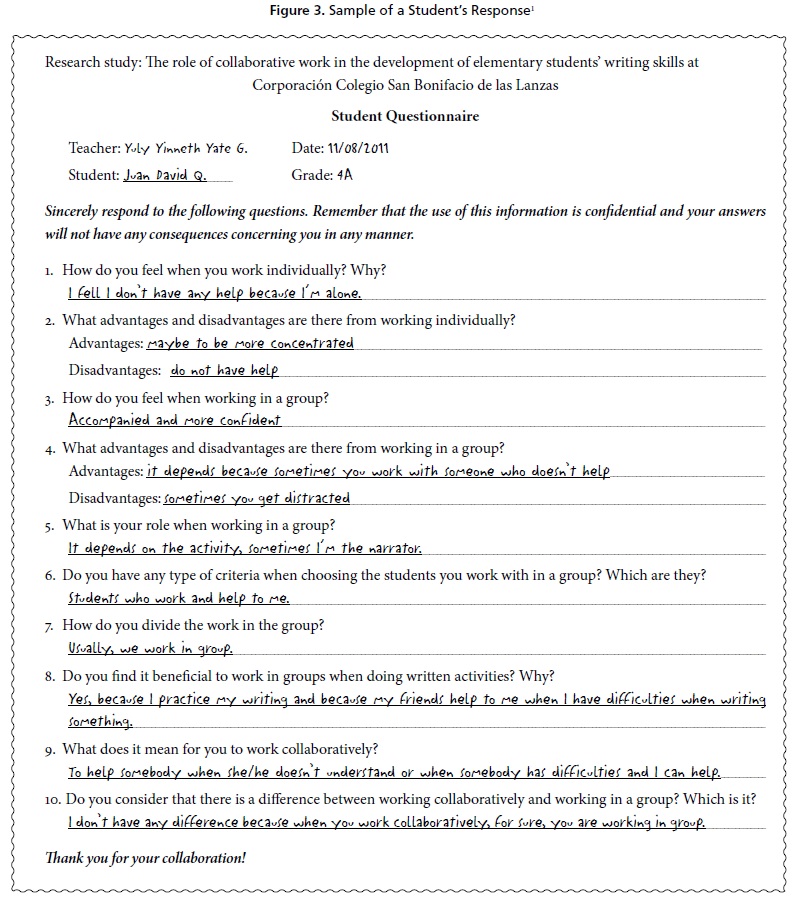

Our research was developed in two stages, following

the action research cycle represented in Figure 2. The

first stage took place during 2011. Teachers observed, collected and read

students’ written productions without their intervention concerning

collaborative work. The intention of such decision was to gather information

about the most common characteristics students have when writing in English.

Teachers applied a survey to students on how they felt in relation to writing

in English, talking about feelings, likes and dislikes when they write during

the English classes (see Figure 31).

In a second stage developed during 2012 and following

the action research cycle represented in Figure 2, teachers

read about strategies based on collaborative work and selected three strategies

that were believed by the teachers to improve students’ writing and at

the same time overcome the difficulties that may arise during the process.

Teachers designed an activity in which they confronted the theory and the

practice of collaborative work with primary students; at the same time,

teachers gathered information from the students’ productions during all

this process. Furthermore, teachers analyzed students’ productions and

teachers’ field notes. Finally, teachers identified new issues in order

to create and develop strategies to help students overcome difficulties.

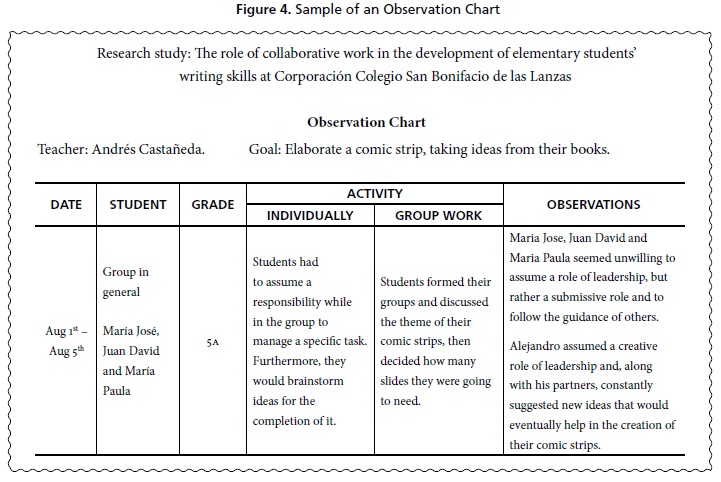

Data Collection

For developing phase number one (observation, data

collection and data analysis - 2011) and phase number two (act on evidence,

strategies implementation, evaluate results, 2012) for the project, teachers

selected students’ written productions done during the second and the

third academic period as sources of information. Teachers created a goal for

students to achieve according to the institutional needs. During the writing

process students had to follow the processes of planning, drafting,

revising and editing, and through these, teachers observed, took

notes (using the observation chart in Figure 4) and

implemented the following strategies:

- The

team plans and outlines the task, then each writer prepares his/her part

and the group compiles the individual parts, then revises the whole

document as needed.

- One

person assigns the tasks, each member completes the individual task, and

one person compiles and revises the document.

- As a

team, students compose the draft, revise it and make necessary changes.

Findings

During the first phase of our research, we analyzed

our findings from the students’ classwork, and then grouped our findings

into four categories of observation: Students’ roles, Task completion,

Language construction and Students’ reactions (see Table

1). As part of an on-going research, we found some interesting information

regarding the differences or rather the fluctuation of responsibilities among

students from different grade levels. Next, we analyzed each aspect and resumed

our findings being specific on the abilities being worked and developed.

Students’ Roles

Elementary students at the San Bonifacio

de las Lanzas School have

clear and marked characteristics regarding their roles while working

collaboratively. During the analysis of the four categories we have done, there

are specific features that let us describe our students’ abilities,

reactions and language situations involved inside a teamwork writing process.

We will describe each of the most relevant factors related to student’s

roles. We want to focus only on the four main roles and behaviors that caught

our attention:

- Students choose their

own roles

- Students vote for a leader

- One student takes

the initiative

- Students’

roles as readers and writers

First, elementary students are able to provide

supported reasons why they choose certain roles inside a group during team

work. For instance, the case in which students choose their own roles,

they do so while considering certain parameters or characteristics they should

have in order to perform that role, such as: the best English in the group, the

best writer, the best reader or the best editor.

In a different case concerning teams in which students

need someone to encourage the team performance, students vote for a leader.

In this case, pretty similar to the one mentioned before, students state their

choice on specific parameters for that leader to carry on and guide the task

completion. Some of the mentioned characteristics are: the best English inside

the group, the most organized person, and students’ reliance on their

abilities to perform different tasks.

Also, on a team in which no one seems to ignite the

labor, there is one student who takes the initiative and, without being

previously chosen, gets people to work. Perhaps this is the most intriguing

case because the one who takes the initiative is not always the student with

the best English inside the group. Contrary to the previous

“Roles”, in which someone is guiding the pro-ject,

this student makes him/herself part of the team and develops part of the task.

As already mentioned, this student may not be the best at English, but his or

her initiative moves the team towards the completion of the task. In this case,

after being motivated, students spontaneously choose a role and perform it.

Students help each other and carry out the project as a whole group. Students

learn about peer-correction and peerwork while

developing the task. We can state that there is meaningful and spontaneous

learning taking place among the students while they help each other.

In the last case, students seem to be more decisive as

to what they want to do while working and being part of a group. In this stage

students know exactly what their abilities are and what they are capable of.

Students then decide to perform the roles of readers and writers.

Students recognize their strength either reading or writing and this helps them

organize the group more quickly.

Task Completion

There exists a great range of characteristics that

label each one of the different grades in terms of task understanding and

completion. However, elementary students have a clear idea of what a task is

and how they have to complete it: students read the instructions, ask for

clarification, divide tasks and compile the results to present a final

production, either orally or written. For this activity, there is a

step-by-step process that nearly all the grades follow, and this process is the

one we want to focus our attention on. The process is organized

as follows:

- Reading and understanding instructions

- Asking

for clarification (does not apply in all the cases)

- Gathering ideas

- Dividing tasks

- Compiling results

- Presenting

final production (orally and/or written)

The groups start developing the task by reading the

instructions; one student reads the task as the other team members listen to

the reader. In some cases, students do not understand what they have to do and

ask for clarification, either the teacher or their peers. It was crucial to

identify that all the groups feel the real need to understand what they have to

do. After reading the

task, students

gather ideas to perform the task. The fact that students always consider their

partners’ ideas was very clear to us. Students collect all the ideas and

then decide upon the best and the most suitable ones for the task. Along with

this, students assigned specific roles inside the groups. These roles are

chosen depending on a member’s abilities to perform different tasks (the

best to do this or that).

Having understood the task, students move to divide

the task for all the members (equal duties). In some cases, one student assigns

the sub-tasks and in other cases, one student performs or develops the task as

the other team members tell them what to do. After this, the group collects the

previous results for the task, reads each of the pieces and agrees on possible

changes or adjustments. Students become their own supervisor of their written

and oral productions. Some groups tend to make adjustments to their productions

at this point, while some other groups seem to be more tolerant and less

objective towards their partners’ contributions (not to hurt

others’ feelings).

When students finish reading the pieces for the task,

they compile the information and present the product. At this point students

check for organization and presentation of the final paper. In some groups one

student is in charge of collecting, compiling and writing the final production,

but other groups choose one person to write the final paper as the rest of the

team has already accomplished their initial task. It was a surprise for us to

find such process among all the grades. Students have a great management of

time and execution to complete the given tasks. They are very careful about the

duties they have to perform and how they will do it.

Language Construction

At San Bonifacio de las Lanzas students have a clear

sense of the work being implemented in class in order to improve their oral

language and writing; doing so has some aspects that enable us as teachers to

observe, analyze and identify strengths and areas of improvement in

students’ daily productions and performance. Given the nature of our

day-to-day work, we, as an investigation group, have identified collaborative

work as part of an on-going performance to aid us in the construction of a

language base.

The focus of this analysis lies within students’

language construction, from the basics of their phonetic level to fluent

speaking, from simple words to complex sentences. During this phase of

students’ work, we have identified as follows several important aspects

that vary with each level (grade):

- Use of

previous knowledge to conceive knowledge.

- Use of

Spanglish to understand or be understood.

- Tools

used to aid in learning; dictionary, monitors, teacher, etc.

- Notion

of correction of common mistakes.

- Punctuation and grammar.

Students from the lowest level come with a notion of

things and their surroundings; this helps them understand much of what is being

worked in class whether it is visual or conceptual. Students also work together

to make the understanding of a specific topic easier. Although this happens

more often in lower grades, the exercise is present among all grades. Although

the use of a dictionary slowly declines as the grade level increases, students

use a variety of tools or methods to understand; the resource used most often

is the teacher; s/he is asked for help with translation or spelling.

The use of Spanglish (a mixture of Spanish and

English) is noticeable among third to fifth grades; students begin to resort to

code switching to make themselves understood,

often during all the activities in class; students will refer to their first language

to complete sentences being constructed, or even specific words that are

unknown to them. Students often feel comfortable and find it easier to code

switch because it eases the fluency of speech; however, at some point they

realize that knowing the word will help them even more; so during their speech

or conversation, students will often ask “How do you say” in order

to complete their ideas.

Students have adapted a notion about words and

structures that enables them to interact with their writing as it progresses.

Some of the most common mistakes students make at San Bonifacio

de las Lanzas are the lack

of completion of sentences (fragmenting) or the use of run-on sentences. When

it comes down to punctuation and grammar, students have issues identifying when

to rely on them for each context; while conversing with students they

manifested that this was due to a confusion of language context; they assume

that in English, rules derived from Spanish do not apply.

Students’ Reaction

At San Bonifacio de las Lanzas students are committed

to learning through a variety of means implemented in class as part of the

pedagogical method. Part of students’ identity could be defined as the

development of students’ different skills through ample fields of learning

such as debates and round table discussions, among others.

The focus on this analysis lies in the reaction of

each student or students as a whole to identify their functions, based on

previous data collection, taking into consideration peer to peer interactions.

We have identified some key aspects related to this investigation, namely:

- Group interaction

- Life experiences

- Positive reinforcement

- Teacher-student interaction

As part of our research we have identified group interaction

to be essential when students brainstorm for possible writing topics;

appreciating different ideas gives students a broad view of what to come up

with in regard to composing texts. Students enjoy time in class specially when

their ideas are heard and appreciated; giving them the opportunity to interact

with one another empowers them with trust and confidence to participate,

positively contribute and overcome difficulties at the speaking level.

One of the most common difficulties students faced during

group interaction was the difference of ideas between boys and girls among low

grade levels (2nd and 3rd). Students’ ideas differ

at the cohesion level; what this means is that boys’ ideas were somewhat

“out in the open” whilst girls’ ideas were direct and

concise, each relating to the activities planned.

Between the ages of 8-11 years old, students’

life experiences help them relate to activities planned and executed during

their learning period. This gives students an opportunity to take ownership of

whichever activity they are undertaking and feel encouraged to brainstorm,

write and share.

As part of a group interaction during each and every

moment of writing as well as oral and listening activities in class, teachers

and students are always communicating, therefore providing valid information

about performances in all of the different fields. Students rely a lot on

feedback to positively construct their work; hence, teacher collaboration and

involvement during these activities is essential. Some students also feel the

need within their “group” to receive positive comments,

observations and interpretations. This need we have identified to be very

motivating and encouraging for almost all students.

As always, students follow a very interesting

“emotional” line through their elementary performances, from

motivated to creative, from curious to enthusiastic; these are all remarkable

aspects to keep in mind when viewing each student’s work as an individual

first and then as part of a group, and it allows teachers and evaluators to

monitor, write down and share this very important piece of knowledge.

As a last point of reference, having students’

involvement, eye contact, questioning and answering becomes a progressive

activity because almost every time, students are advancing more and more

through their performances, learning and getting used to new methods to do

things.

Conclusions

The implementation of the three strategies for working

collaboratively showed interesting results. In the first place, when the team

plans and outlines the task, each writer prepares his/her part and then the

group compiles the individual parts and revises the whole document as needed.

Students felt less comfortable when they felt that their ideas might not be

heard or determined, and this prompted them not to speak or interact with the

other members of the team in a natural and harmonic way. Some discussions flew

around the group environment but students finally seemed to understand that the

group task prevails over their own or individual interests (students’

roles).

Also, the teams adequately managed time and the

subdivisions of the task to comprehend the given work. Students still focused

their attention on completing the task and dividing the amount of work so that

everyone had their own part and the team achieved its goal (task completion).

In addition, students seemed to rely more on their partners’ corrections

and contributions than on their teachers’. For this strategy, each one of

the members of the team maintained a close relation with their team colleagues

to the point that language interaction, correction and construction comprised

an essential and innate state of the group (language construction).

In second place, when one person assigns the tasks,

each member completes the individual task e.g. one person compiles and revises

the document in question. Students adopted different roles but a specific

feature that remained was evidenced whereby students seemed to feel more

comfortable when they performed a role for which they had the best talent or

ability (writer, idea proposer, leader, compiler, editor). For this strategy

and, as teams had no leaders, the groups decided to assign roles considering

their members’ abilities for different tasks (students’ roles).

As such, students comprehend the relevance and

importance of their contributions to the initial task. Members of the teams

felt comfortable working on their own with no observer carefully watching what

they had to do; instead, team members preferred to consider their colleagues a

supportive axis concerning the task completion, an axis on which they could

rely and trust in order to understand better the task intention and how to

develop it (task completion). One student of the team was the one who

provided final feedback on the members’ contributions, which made the

rest of the team a bit unsatisfied due to the poor and not so reliable

feedback. As the only voice that was heard at that point was the

editor’s, the team had not much to do in terms of correction and

revision. Language use and function was directly used in terms of oral

feedback. Written language was used only to correct and edit the document (language

construction).

In third place, when the team plans and outlines the

task and writes a draft, the group revises the draft, thus students feel that

their contributions for the task are relevant and considered when developing

either of the task subdivisions. No student performed a specific role so that

everyone could contribute and have his/her own ideas on what to do and what not

to do considered by the others (students’ roles).

Also, working with this strategy, ideas flew around

the team environment providing a much wider view of what the task intended to

achieve and the best methods to do so. Each one of the students assumed one of

the task subdivisions, contributed to the task completion with his/her ideas,

comments or suggestions, and provided feedback, orally and in writing, for

their classmates. Students’ interaction happened in a more natural way and

this allowed the task to be completely achieved (task completion). In

addition, language was freely used by every member of the team. Students used

the language to communicate ideas, correct each other, provide accurate

feedback on the paper’s progress and edit a final version of the paper.

For complete achievement of the task students got a clear idea of how important

it was to help each other and provide accurate and grounded feedback

that help the team reach their initial goal (language construction).

As we could see, at San Bonifacio

de las Lanzas,

collaborative learning is an opportunity for students to help each other to

construct meaning and knowledge, as they work on tasks that demand analyzing,

planning, acting and reflecting on their work as a tool to measure their

capacity to work with others, and their abilities and contributions as regards

common tasks.

Finally, through this research teachers noticed how

relevant and meaningful collaborative learning is in students’ learning

process. So, we can move towards the intention of this type of approach in

Education, and more important, the role of Education around Collaborative

Learning.

* This paper reports on a study conducted by the authors

while participating in a Teacher Development Program led by the PROFILE

Research Group of Universidad Nacional de Colombia. The Program was sponsored

by the Corporación

Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas (Ibagué, Colombia) 2010-2012.

1 The questionnaire

was originally administered in Spanish–the students’ mother

tongue–and translated into English for the purpose of this publication.

References

Bazerman, C. (2007). Handbook of research on writing:

History, society, school, individual, text. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Britton, J., Burgess, A., Martin, N., Macleod, A.,

& Rosen, H. (1975). The development of writing abilities. London, UK: Macmillan.

Corporación

Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas. (2010). Plan de Área

Inglés. English Area. Ibagué, CO: Author.

Corporación

Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas. (2011). Proyecto Educativo

Institucional (PEI). Ibagué, co: Author.

Council of Europe. (2001). The Common European framework of reference for languages:

Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, uk: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://assets.cambridge.org/052180/3136/sample/0521803136WS.pdf

Dillon, A. (1993). How collaborative is collaborative

writing? An analysis of the production of two technical

reports. In M. Sharples (Ed.), Computer

supported collaborative writing (pp. 69-86). London, uk: Springer-Verlag.

Dyson, A. (2000). On refraining

children’s words: The perils, promises, and pleasures of writing

children. Research in the teaching of English, 34(3),

352-367.

Ferrance, E. (2000). Action research

cycle. Providence: Northeast and Islands Regional Educational

Laboratory at Brown University. Retrieved from http://www.lab.brown.edu/pubs/themes_ed/act_research.pdf

Hillocks, G. Jr. (1986). Research on written composition: New directions

for teaching. Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Kamberelis, G. (1999). Genre development: Children writing

stories, science reports and poems. Research in the Teaching of English, 33(4),

403-460.

Long, M., & Richards, J. C. (1990). Second language writing. New York, NY: Cambridge

University Press.

MacArthur, C., Graham, S., & Fitzgerald, J.

(2006). Handbook of writing research.

New York, NY: Guilford Press.

McLane, J. B. (1990). Writing as a

social process. In L. C. Moll (Ed.), Vygotsky and education (pp. 304-318).

Cambridge, uk: Cambridge

University Press.

Myles, J. (2002). Second language writing and

research: The writing process and error analysis in student texts. TESL-EJ Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, 6(2).

Retrieved from http://www.cc.kyoto-su.ac.jp/information/tesl-ej/ej22/a1.html

Smith, B. L., & Macgregor, J. T. (1992). What is collaborative learning? Collaborative

Learning: A sourcebook for higher education. Anti essays.

Retrieved from http://www.antiessays.com/free-essays/81887.html

About the Authors

Yuly Yinneth Yate

González is about to obtain a BA

in English from Universidad del Tolima, Colombia. She is currently a full-time

English Teacher at Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas, Ibagué,

Colombia. Her interests include issues related to action research and applied

linguistics.

Luis

Fernando Saenz is a full-time

English teacher at Corporación Colegio San

Bonifacio de las Lanzas, Ibagué, Colombia. He is about to graduate from the undergraduate English teaching program

at Universidad del Tolima (Colombia).

Johanna Alejandra Bermeo holds a BA in English from Universidad del Tolima,

Colombia. She is currently working at Berlitz Istanbul (Turkey) as an ESP and

EFL teacher and native Spanish language instructor.

Andrés

Fernando Castañeda Chaves is a full-time

English teacher at Corporación Colegio San

Bonifacio de las Lanzas, Ibagué, Colombia. He is a student in the undergraduate English teaching program at

Universidad del Tolima (Colombia).

References

Bazerman, C. (2007). Handbook of research on writing: History, society, school, individual, text. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Britton, J., Burgess, A., Martin, N., Macleod, A., & Rosen, H. (1975). The development of writing abilities. London, UK: Macmillan.

Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas. (2010). Plan de Área Inglés. English Area. Ibagué, CO: Author.

Corporación Colegio San Bonifacio de las Lanzas. (2011). Proyecto Educativo Institucional (PEI). Ibagué, co: Author.

Council of Europe. (2001). The Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, uk: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://assets.cambridge.org/052180/3136/sample/0521803136WS.pdf

Dillon, A. (1993). How collaborative is collaborative writing? An analysis of the production of two technical reports. In M. Sharples (Ed.), Computer supported collaborative writing (pp. 69-86). London, uk: Springer-Verlag.

Dyson, A. (2000). On refraining children’s words: The perils, promises, and pleasures of writing children. Research in the teaching of English, 34(3), 352-367.

Ferrance, E. (2000). Action research cycle. Providence: Northeast and Islands Regional Educational Laboratory at Brown University. Retrieved from http://www.lab.brown.edu/pubs/themes_ed/act_research.pdf

Hillocks, G. Jr. (1986). Research on written composition: New directions for teaching. Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Kamberelis, G. (1999). Genre development: Children writing stories, science reports and poems. Research in the Teaching of English, 33(4), 403-460.

Long, M., & Richards, J. C. (1990). Second language writing. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

MacArthur, C., Graham, S., & Fitzgerald, J. (2006). Handbook of writing research. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

McLane, J. B. (1990). Writing as a social process. In L. C. Moll (Ed.), Vygotsky and education (pp. 304-318). Cambridge, uk: Cambridge University Press.

Myles, J. (2002). Second language writing and research: The writing process and error analysis in student texts. TESL-EJ Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, 6(2). Retrieved from http://www.cc.kyoto-su.ac.jp/information/tesl-ej/ej22/a1.html

Smith, B. L., & Macgregor, J. T. (1992). What is collaborative learning? Collaborative Learning: A sourcebook for higher education. Anti essays. Retrieved from http://www.antiessays.com/free-essays/81887.html

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2013 Yuly Yinneth Yate González, Luis Fernando Saenz, Johanna Alejandra Bermeo, Andrés Fernando Castañeda Chaves

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.