Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs about Language Teaching and Learning: A Longitudinal Study

Creencias de profesores principiantes acerca de la enseñanza y aprendizaje de lengua: un estudio longitudinal

Keywords:

Learning beliefs, pre-service teachers, teaching beliefs (en)Creencias sobre el aprendizaje, creencias sobre la enseñanza, profesores principiantes (es)

This paper contains the description of a research project that was carried out in the Bachelor of Arts in English Language Teaching program at a Mexican university. The study was longitudinal and it tracked fourteen students for four semesters of the eight semester program. The aim was to identify pre-service teachers’ beliefs about English language teaching and learning at different stages of instruction while they were taking the teaching practice courses in the program. The instruments employed were questionnaires and semi-structured interviews. The results demonstrated that students made links between theory and practice creating some changes in previous beliefs. The study revealed an increase of awareness and a better understanding of the complex processes involved in teaching and learning.

En este artículo se describe una investigación que se llevó a cabo en el programa de Licenciatura en Enseñanza del Inglés de una universidad mexicana. El estudio fue longitudinal, el cual siguió la trayectoria de catorce estudiantes de la licenciatura durante cuatro de los ocho semestres del programa académico. El propósito fue identificar las creencias de estos maestros principiantes, quienes cursaban sus clases de práctica docente del programa, acerca de la enseñanza y el aprendizaje del inglés en diferentes etapas de sus estudios. Los instrumentos utilizados fueron cuestionarios y entrevistas semiestructuradas. Los resultados demostraron que los estudiantes articularon la teoría con la práctica, lo cual incidió en sus creencias anteriores. El estudio también reveló que comprendieron mejor los complejos procesos involucrados en la enseñanza y el aprendizaje.

Pre-Service

Teachers’ Beliefs about Language Teaching and Learning: A Longitudinal

Study*

Creencias de profesores principiantes acerca de la enseñanza y aprendizaje de lengua: un estudio longitudinal

Sofía D. Cota Grijalva*

Elizabeth Ruiz-Esparza Barajas**

Universidad

de Sonora, Mexico

*scota@lenext.uson.mx

**elruiz@guaymas.uson.mx

This article

was received on June 22, 2012, and accepted on November 28, 2012.

This paper contains the description

of a research project that was carried out in the Bachelor of Arts in English

Language Teaching program at a Mexican university. The study was longitudinal

and it tracked fourteen students for four semesters of the eight semester

program. The aim was to identify pre-service teachers’ beliefs about

English language teaching and learning at different stages of instruction while

they were taking the teaching practice courses in the program. The instruments

employed were questionnaires and semi-structured interviews. The results

demonstrated that students made links between theory and practice creating some

changes in previous beliefs. The study revealed an increase of awareness and a

better understanding of the complex processes involved in teaching and

learning.

Key words: Learning beliefs, pre-service teachers, teaching

beliefs.

En

este artículo se describe una investigación que se llevó a

cabo en el programa de Licenciatura en Enseñanza del Inglés de

una universidad mexicana. El estudio fue longitudinal, el cual siguió la

trayectoria de catorce estudiantes de la licenciatura durante cuatro de los

ocho semestres del programa académico. El propósito fue

identificar las creencias de estos maestros principiantes, quienes cursaban sus

clases de práctica docente del programa, acerca de la enseñanza y

el aprendizaje del inglés en diferentes etapas de sus estudios. Los

instrumentos utilizados fueron cuestionarios y entrevistas semiestructuradas.

Los resultados demostraron que los estudiantes articularon la teoría con

la práctica, lo cual incidió en sus creencias anteriores. El

estudio también reveló que comprendieron mejor los complejos

procesos involucrados en la enseñanza y el aprendizaje.

Palabras clave: creencias sobre el aprendizaje, creencias

sobre la enseñanza, profesores principiantes.

Introduction

It is often assumed

that teaching in higher education is the result of the subject-matter knowledge

and intuitive decisions based on teachers’ experiences and beliefs about

how the subject-matter should be taught (Turner-Bisset, 2001; Shulman, 2005).

However, beliefs are such powerful influences that affect the way teachers

carry out every aspect of their work because they act as lenses which filter

every interpretation and decision teachers make (Johnson, 1999). Teacher

education programs are many times unsuccessful in helping pre-service teachers

to develop modern approaches to pedagogy because these programs do not consider

their beliefs (Wideen, Mayer-Smith, & Moon, 1998). Deng (2004) argues that

pre-service teacher beliefs need to be transformed for pre-service teachers to

teach in new ways. However, transforming beliefs is not an easy endeavor.

Williams (1999) suggests that a socio-constructivist view of learning where

teacher educators mediate between theory and practice through reflection will

help learners reshape or construct new beliefs. Therefore, identifying

pre-service teacher beliefs and making these future teachers aware of their own

beliefs seem crucial for teacher education programs.

The present study

took place in a Bachelor of Arts in English Language Teaching (BA in ELT)

program which has as its main purpose to offer professional preparation for

future teachers of English. Students in their last two semesters of the BA

program are placed in institutions where they can practice teaching. Therefore,

this context offers a great opportunity to find out these students’

beliefs before and after the teaching stage to try to understand how their

teaching beliefs work. For the purpose of this paper and, considering that the

students of the program are first pre-service teachers and in the last years of

instruction become in-service teachers, the students will be referred to as

pre-service teachers or participants because they will not receive the degree

until the fulfillment of the program.

This research aims

to find out the pre-service teachers’ beliefs about English language

teaching and learning. It also focuses on whether those current beliefs were

influenced by their teaching courses and the experience gained throughout the

time spent during their academic preparation as English teachers. This research

highlights the importance of not only raising the teacher educators’

awareness of the pre-service students’ beliefs about language learning

and teaching but of making the participants aware of their own beliefs. It also

stresses the crucial need for English language teacher educators and program

designers to identify the pre-service students’ beliefs at initial stages

of instruction so that they can develop strategies to modify and understand

those beliefs which hinder the efficacy of teacher instruction. This

longitudinal study also aims to contribute to the theory about pre-service

teacher beliefs and hopes to add to the literature

that informs the practices of teacher education. Moreover, it also presents

information about a context that has been scarcely explored, that of

pre-service teachers of English in Mexico.

This paper is

organized in the following way: First, some key aspects of the literature are

presented followed by the context of the study. Then, the methodology and the

data collection are explained, concluding with the presentation of results and

discussion of the findings.

Teacher Beliefs

Teacher

effectiveness depends on the conceptualization of all of the elements involved

in teaching, although the personality and beliefs also influence their teaching

practice. Theories have stressed the idea that most teachers guide their

actions and decisions by a set of organized personal beliefs and that these

often affect their performance, consciously or unconsciously (Johnson, 1999).

It has also been discussed in the literature that teachers usually teach the

same way they were taught since they tend to follow the same rules and routines

making reference to their learning experience (Bailey, Curtis, & Nunan,

2001). Therefore, teachers’ beliefs shape the world in which they and

their students operate and these mental models of “reality” are

highly individualistic since no two classrooms are, or can be, the same. In

addition, Abraham and Vann (1987) explain that learners’ philosophy of

language refer to “beliefs about how language operates, and,

consequently, how it is learned” (p. 95). This philosophy guides the

learners approach to language learning. Ferreira (2006)

claims that beliefs about second language acquisition will directly impact

learners’ attitudes, motivation and learning strategies. Thus, the

authors state that beliefs are usually shaped by students’ and

teachers’ backgrounds since they are formed through interactions with

others, own experiences and the impact of the environment around them.

It has been

difficult to establish a single definition for the concept of belief since

different authors understand it from a personal perspective. Some authors refer

to beliefs as cognition, knowledge, conceptions of teaching, pedagogical

knowledge, practical knowledge, practical theories, theoretical orientations,

images, attitudes, assumptions, conceptions, perspectives or lay theories to

name some definitions (Borg, 2006). One of the authors who focused his

attention on trying to explain the meaning of beliefs and search for a clear

definition of the concept was Pajares (1992), who concluded that “The

construct of educational beliefs is itself broad and encompassing” (p.

316). Therefore, as there is no clear cut definition about beliefs, for the

purpose of this paper they will be defined as interactive networks of

assumptions and knowledge about educational processes.

Finally, in the

literature, Pajares (1992) says that “the earlier a belief is

incorporated into the belief structure the more difficult it is to alter”

(p. 317). Many studies have shown that beliefs are deeply rooted and are

resistant to change (Richards, Gallo, & Renandya, 2001). However, Williams

(1999) states that providing teachers with the link between theory and

practice, which should be mediated by reflection in a socio-constructivist

approach, change can be brought about. Therefore, because of the importance of

beliefs about language learning and teaching for teacher educator programs,

this study aimed to know more about the future teachers’ beliefs. In

addition, this research tried to find out whether the BA in ELT program is

providing positive orientation and instruction as well as being successful in

helping students to become better teachers of English.

Research Questions

The research questions for this study were:

- What

are the pre-service teachers’ beliefs about language learning and

teaching in the 4th, 6th and 8th

semesters?

- To what

extent did the pre-service teachers’ beliefs change?

- How did

pre-service teachers’ beliefs evolve?

- To what

extent does the Teaching Practice strand influence pre-service

teachers’ beliefs?

Research Method

As the questions

for this study are concerned with finding out pre-service teachers’

beliefs about teaching and learning, as well as understanding whether these

beliefs changed and influenced their role as future teachers, its framework

falls within a mixed mode approach to research. Creswell and Plano Clark (2011)

state that “Mixed methods research provides more evidence for studying a

research problem than either quantitative or qualitative research alone”

(p. 12). Relevant to the purpose of using a mixed mode approach in this study

is that, among its benefits, qualitative data can help explain quantitative

results (Cumming, 2004; Lazaraton, 2000). In this case, the research design

used quantitative and qualitative approaches aiming to support each other. The

methodology and the approach to data collection warranted or called for

questionnaires and interviews that provided a strong support for the study. As

the questionnaire was applied at different times during the students’

professional preparation, the study was a longitudinal one.

Context

This longitudinal

study was carried out at the University of Sonora, which is in the Northwestern

part of Mexico, in a BA in ELT program that offers professional preparation for

students who want to become teachers of English. The program, organized in

eight semesters, provides not only English language courses, but stresses a

theoretical and pedagogical background for language teachers. It also places

great importance on the relationship between theory and practice by helping

students to develop their teaching techniques and skills in real teaching

contexts.

The series of the

teaching practice courses in the program provides the link between theory and

practice and a strong theoretical teaching background where students are

familiarized with the elements, theories and methodologies for teaching a

foreign language. These courses also provide a link with the other courses in

the program since the practice they offer help students to make sense of the

pedagogical, linguistic and cultural knowledge. It is during the third semester

that students are introduced to the first teaching practice course where they

learn and develop classroom management skills and become familiar with the

basic elements of a classroom. The second course is Teaching Practice I in the

fourth semester where they learn about lesson and unit planning and how to deal

with the teaching of the four skills. In this course, the students carry out

observations, but it is during the sixth and eight semesters when they take

Practice II and III that students practice in real contexts, that is, they are

sent to different educational institutions where they have the opportunity to

practice teaching and learn from this experience. These opportunities provide

them with the experience needed and help them gain more insights as to what

this profession is about. Furthermore, by this time, many students also start

working as teachers in different local institutions and start benefiting from

this teaching experience.

Participants

The participants

involved in this project were all Mexican students of this BA in ELT program;

they were thirteen females and one male and all were non-native English

speakers. It is important to say that seven of the fourteen students of this

project started working while the project was in progress and the rest were

full time students. They were all contacted when they registered for their

second Teaching Practice course in the fourth semester and they all agreed to

participate in this project until the conclusion of their studies.

Instruments for Data Collection

Two instruments

were used: a questionnaire and an interview. The questionnaire was adapted from

the Beliefs about Language Learning Inventory (BALLI) developed by Horwitz

(1988), who gave the researchers permission to adapt it. Seven out of the

twenty questions were taken from it and the rest were adapted and developed by

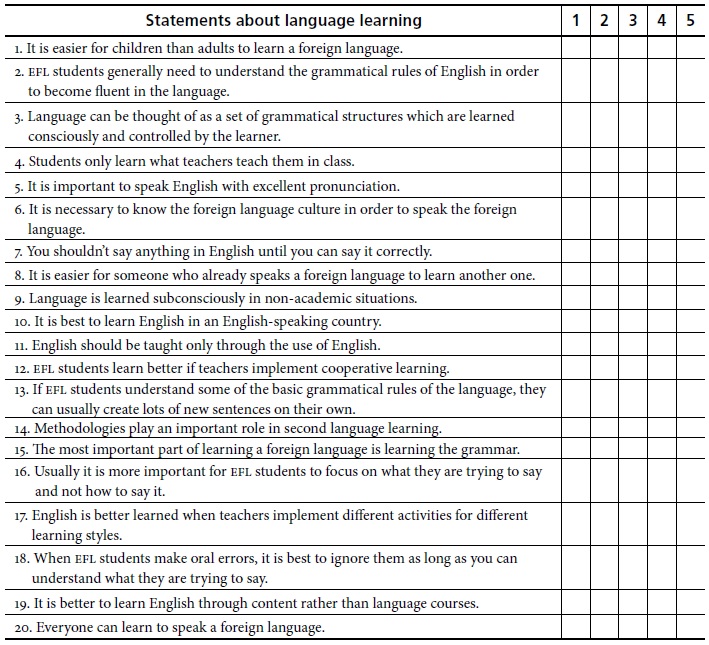

the researchers based on the context and the research needs (see Appendix A).

To answer the

questionnaire, students had to choose from the five options presented following

the Likert scale. The options ranged from those which (1) strongly agree, (2)

agree, to the ones which they (4) disagree, and (5) strongly disagree. There is

a neutral (3) element which provides the option to consider the belief in

process of definition. That is, those responses which were not yet defined by

the student. They were categorized as a position where the student was not

certain of the belief in question and he/she was in the process of agreeing or

disagreeing with the statement. There was no right or wrong answer to the

statements since they were designed to actually bring students’ opinions

about teaching and learning to the surface and to see if those ideas changed

over a period of two years.

The interviews were

semi-structured and were carried out just before the participants exited the

program with the aim of verifying information and finding reasons for their

responses. The interview consisted of six open-ended questions (see Appendix B).

Data Collection

The questionnaire

was applied the first time to the students when they started the fourth

semester of the BA in ELT program while they were taking the Teaching Practice

I course. The students were tracked throughout the rest of their studies and

the questionnaire was applied to them again when they were in the sixth and

eighth semesters. Just before they exited the program, the interviews took

place with the purpose of confirming and/or expanding the data collected from

the written questionnaires. These interviews were recorded and transcribed

following Jefferson’s transcription conventions (in Ellis &

Barkhuizen, 2005).

Data Analysis

Once the data were

collected, the questionnaires were analyzed. The first step, the qualitative

part, was to find out the students’ beliefs about language learning and

teaching. The statements which dealt with the same topic were grouped in order

to verify if the participants contradicted or verified their own information.

Then, the frequencies of their responses were analyzed. The data presented

considered those students who started working while the project was in progress

and those who did not work while they were studying. Although the responses ranged

from those who strongly agree to strongly disagree, to make the results more

transparent, the agreement responses were collated as in the case of the

disagreement responses. Therefore, data responses could be grouped into three

categories –agree, neutral and disagree. The second step was to analyze

whether the beliefs had changed. The researchers concentrated on finding out

whether the original beliefs had changed and to see whether a pattern could be

observed. The third and final step, the qualitative part, was analyzing the

transcripts of the interviews to verify the information given in the

questionnaires, to discover reasons for their responses and to interpret ways

in which their beliefs, whether changed or maintained, influenced their

practice when teaching.

Findings

There were two

kinds of findings, one derived from the questionnaires and the other one from

the interviews. For the questionnaires, the response frequencies of the beliefs

are presented in tables and the most relevant findings are highlighted. The

results of the interviews intended to clarify and expand the students’

responses on the questionnaires and are explained following the questionnaire

findings.

Findings from the Questionnaires

The information

that is presented below shows the beliefs which emerged from the questionnaires

applied to the students involved in this project. Each belief was organized and

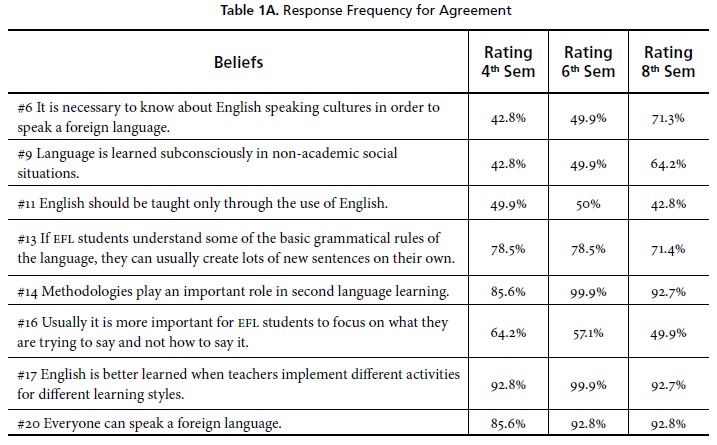

placed under the category response which showed the highest rating. Table 1A presents those beliefs participants agreed on most

and that were maintained throughout the years of instruction, although the

degrees for agreement for this category varied in the different semesters.

As can be observed

in Table 1A, belief number 14 is related to the role of

methodology and shows that the rating of agreement is higher for the sixth

semester. It is interesting to note that it is precisely in that semester where

students have just finished taking the methodology courses and have been

practicing using the variety of methodologies in the Teaching Practice course.

Therefore, it is suggested that the students from the sixth semester were

influenced by the courses taught in the program. In addition, belief number 6

shows the highest increase of responses. It is important to mention that the

students take two courses on the culture of English speaking countries and two

other courses for the learning of American literature. Hence, this might also

suggest that there is an influence of the teaching preparation received from

the program in these two students’ beliefs.

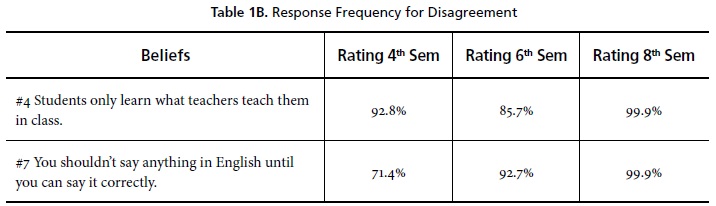

Table

1B represents those beliefs which students disagree on most. Students seem

to see learning as a more flexible and personal process.

It is clearly seen

by the end of the eight semesters that students strongly believe it is the

learners’ responsibility to take control of their learning. They seem to

have reinforced these beliefs since the rating is higher. These beliefs reflect

the emphasis on promoting learner responsibility carried out by the teachers of

the program. This situation recalls Ruiz-Esparza’s (2009) findings in which

she was investigating teacher beliefs about assessment in this same context and

found out that the teachers had one main goal: to make students more autonomous

and responsible of their own learning.

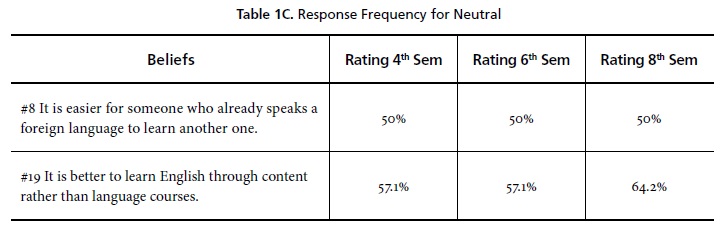

Table

1C presents beliefs that were kept neutral throughout the years of

instruction. It is interesting to note that the rating for belief number eight

was kept the same.

As some of the

students in the program come from bilingual schools and others have done part

of their schooling in the United States, the beliefs in Table

1C could reflect what was stated in the literature section of this paper.

Students’ responses may be influenced by their own experience as second

language learners since students tend to agree on ideas based on what has

worked for them and believe that the same way will work for other people

(Bailey et al., 2001). The program did not seem to exert any influence on those

beliefs.

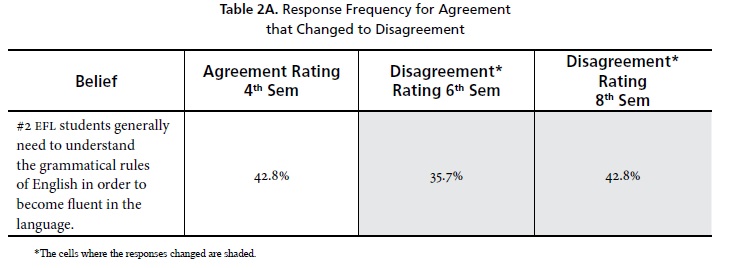

Table

2A shows one belief which students changed from agreement to disagreement

keeping the same percentage. This is belief number two, which although the

percentage is not the highest, students began to disagree on it in the sixth

semester.

Belief 2 in Table 2A is related to theories of language learning and

modern pedagogy which are studied in the program and practiced in the Teaching

Practice courses. Therefore, the change in this belief might be a direct

influence of the program.

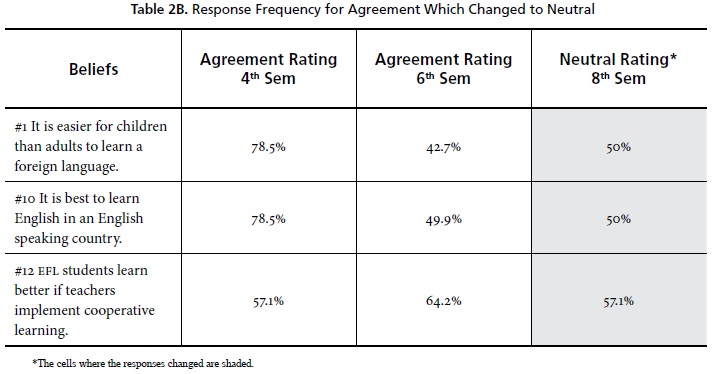

Table

2B presents three beliefs that during the fourth semester were ranked high

by most of the students. However, by the end of the eight semesters, students

did not consider them to be in the same category.

Beliefs number one

and ten had a strong position of agreement at the beginning of the study, but

students began to change by the sixth semester as can be deducted by the

decrease in their degree of agreement. The reason for the change in belief 1 is

clarified in the interview section of this paper and concerns their experience

in learning. The result for belief number 12 might have its roots in the

students’ knowledge of the different methodologies seen in class and

experienced in their Teaching Practice courses where they need to teach using

different methodologies and to reflect on the results.

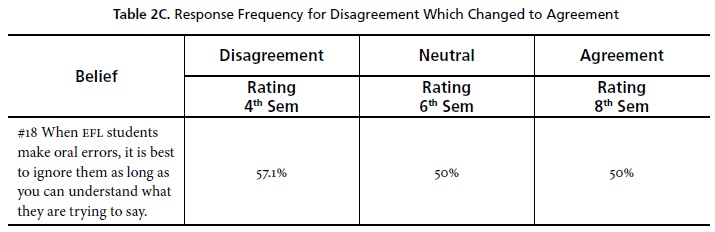

Table

2C evidences the evolution of a belief which drastically changed from

disagreement to agreement. It can be observed that students disagreed in the

fourth semester with belief 18; they then changed to neutral in the sixth to

finally agree in the last semester of the program.

It could be

hypothesized that as the students were receiving information about the role of

mistakes in language learning, they started doubting their belief by the middle

of the program and then changed their belief after experiencing teaching.

Although the percentages are not very high, they were the highest rankings for

the sixth and eighth semester. This result evidences that not all of the

students have a strong conviction that oral errors are part of learning, and as

Table 2D seems to suggest, students seem to be more

flexible in seeing mistakes as part of the learning process. This also suggests

that the students are more aware of the importance of meaning instead of form.

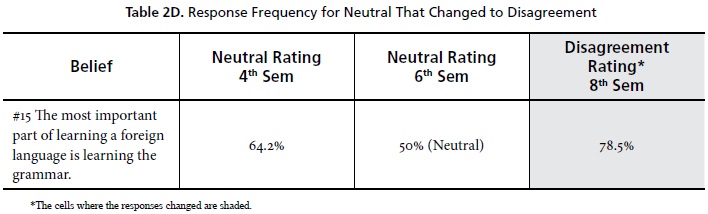

Table

2D corresponds to a belief that changed from neutral to disagreement and it

is related to the importance of grammar. The reason for the change in this

belief is clarified in the interview section.

Belief 15 seems to

contradict the students’ response in the fourth semester about the role

of mistakes observed in Table 2C for belief 18. Although

they had disagreed that it is best to ignore students’ oral errors when

they speak, they were neutral to the importance of grammar in their responses

for the 4th semester. Moreover, there is not much difference in the

degree of response for belief 15 which is neutral in the 4th and 6th

semesters but by the end of the 8th semester, this belief changed.

It could therefore be moot that most students felt that grammar may not be that

important when learning a foreign language because of the change in category

and the high increase of the percentage.

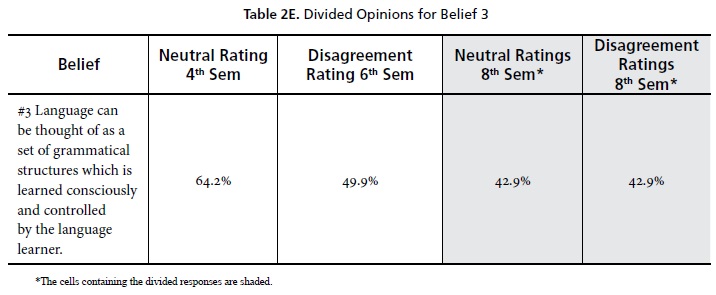

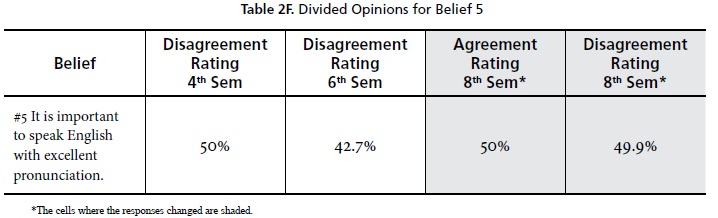

The last two

tables, 2E and 2F, show

interesting results for two beliefs because the pattern of responses was

different to the one analyzed before. Table 2E shows the

ratings for the frequency responses for belief 3.

As can be observed

in Table 2E, 64 percent of the students in the 4th

semester were neutral for belief number 3 and then changed their responses to

disagreement in the sixth semester. Finally in the eighth semester, the

majority of responses were divided between the previous responses of neutral

and disagreement.

Table

2F shows the frequency of responses for belief number 5. This table also

evidences that the eighth semester students were divided in their opinions.

Table

2F indicates that the students did not change their belief in the fourth

and sixth semesters and that in their last semester only half of the

participants changed their belief drastically from disagreement to agreement.

Therefore, half of the participants consider excellent pronunciation important.

Although not all of

the beliefs presented here changed, it is interesting to note the change of

perception, especially in beliefs numbers one, two, ten, twelve, eighteen and

fifteen.

Findings from the Interviews

By the end of the

participants’ academic preparation, the semi-structured interviews were

carried out with the purpose of expanding and finding out more information

about the reasons which influenced their teaching and learning beliefs. The

questions addressed their own English learning process to know about the

different stages they went through when learning English and to contrast them

with their actual view of such process. Most of the pre-service teachers came

to discover their learning beliefs and how some of them have changed with time

and experience.

In relation to the

first question about how English is learned, most of the pre-service teachers

answered that it is learned by practicing the language and carrying out

different learning activities. Participant 1 (P-1) added “motivation”

while Participant 2 (P-2) mentioned the use of “different methods,

strategies and activities.” These two answers are linked to beliefs #14

and #17. The second question about how English should be taught is closely

related to the first question and the same beliefs, although students added

that they “Now need to have different methods and to observe what

students like” (P-2). Another participant stated, “Teaching should

be based on the needs of the students, the different learning styles and the

variety of strategies” (P-5) which supported both points of view.

The third question

about how they learned English gave the information that half of the group

interviewed had close contact with the American culture since they studied in

bilingual schools or lived for a period of time in the United States. It was

interesting to note that although they agreed on the importance of the context,

they were more open to accept that the use of appropriate methodology is as

important as exposure to the language. Participant 1 said, “I had a

private teacher and with practice, I suddenly began to speak.” Therefore,

the student practiced the target language with the teacher. Another student

said, “I don’t know how I learned, but I used to watch TV or movies

in English” (P-5). None of them mentioned that age determined their

learning of English as belief #1 states. They were more concerned with

receiving enough practice than living in an American context as belief #10

suggest, in which case they changed from agreement to neutral as was manifested

in the responses from the questionnaire.

The fourth question

about how they were taught made them reflect on their own learning process.

Some of them said, “I was never taught because I lived in the United

States” (P-6). In contrast others said, “With practice”

(P-10), “Little by little we formed sentences” (P-4) or

“Repeating and repeating sometimes the same things over and over”

(P-9). They reported different approaches and experiences.

The fifth and the

sixth questions related to whether their perspectives on how English is taught

and learned generated many comments considering that, as in-service language

teachers, they were very much aware of the second language learning processes.

As Participant 2 said, “I thought all of the students learned the same,

but now I know they don’t.” Participant 3 stated, “I used to

think everything came from the book, now I know the book is not all”

while Participant 5 added, “I thought that the way we were taught was the

correct one, now I know that we all have different learning styles.” This

last comment reflects the claim of Bailey et al. (2001) that teachers usually

teach the same way they were taught making reference to their own learning

experience. The comments from participants 2, 3 and 5 also indicate that as

they received information from the teaching courses, they modified their

perception as well. All of the participants were conscious of their own

experiences as language learners and understood the importance of such

experience as language teachers. Their perspective of how English should be

taught changed and they affirmed that “There are other factors, such as

the affective one, that it’s very important” (P-1); “It

shouldn’t be a lonely process but a collaborative one where the teacher

and students must interact and learn” (P-3). They seemed to be more open

and receptive to other factors.

The interviews shed

light on where most of their beliefs come from and also provided interesting

information about how they were modified and why. All of the pre-service

teachers were conscious of their own experiences as language learners and

understood the importance of such experience as language teachers. They were

confident in the changes of perceptions, agreeing that the knowledge of grammar

is not the only important element when learning a foreign language (belief

#15).

During the

interviews, the participants often emphasized the importance of the information

received during the Teaching Practice Courses throughout the program. There

were beliefs which were often discussed in class and were very common such as

the popular idea that children learn better than adults (belief #1). Their

responses on the questionnaires were probably neutralized by the fact they

learned that “adults proceed through early stages of syntactic and

morphological development faster than children do” (Collier, 1995, p.

18). Another insight was related to the learning of English through content and

in an English speaking context. Participants reflected on their personal experiences

of English learning (half of the participants interviewed learned English in

American contexts as mentioned earlier) and confirmed the idea that we tend to

believe in learning strategies that are familiar to our experience. What became

evident from the interviews was that the participants were very much aware and

concerned about the language processes and their implications in teaching and

learning. They all agreed that teaching and learning is much more complex than

they thought they were. They agreed that the academic preparation they received

made them learn and know about the implications of becoming good language

teachers.

Conclusion

The main purpose of

this study was to identify the beliefs future teachers hold toward teaching and

learning, how these evolved and to what extent the impact of the Teaching

Practice courses have on them. The results highlight the finding that 40

percent of the beliefs changed while 60 percent remained the same. It can be

hypothesized that the teaching preparation received in the program along with

the Teaching Practice courses where the pre-service teachers experience and

reflect on teaching, may have influenced the changes presented. The methodology

followed in the program recalls Williams’ (1999) claims for teacher educators

to help learners reshape their beliefs by mediating between theory and practice

through reflection and the awareness of learners’ own beliefs. During the

interviews, some of the pre-service teachers said that they were in the process

of changing some of their practices and it can be suggested that such change is

the result of changing beliefs (Richards et al., 2001). It is true that more

research needs to be done because what pre-service teachers say and what

actually happens in the classroom have not been observed. However, this

awareness about their own beliefs may lead to change since it involves trying

to do things differently (Freeman, in Richards et al., 2001).

The results

highlight the pre-service teachers’ concern for becoming good teachers of

English as they expressed a deep comprehension of the teaching/learning

process. The longitudinal study suggests that they gradually became aware of

the complexities involved in teaching and were “more aware of the

elements involved in the process of learning” as one of the students

said. They all agreed that the process of second language acquisition is

complex, takes time and requires a lot of effort to be completed successfully.

They also agreed that the teaching preparation received in the program gave

them the tools and theoretical basis to understand and be aware of their own

teaching and learning beliefs.

It is important to

add that one of the limitations of the research is that it started at the

beginning of the fourth semester and thus, the question arises as to whether

the beliefs of the pre-service teachers were the same as when entering the

program. Another limitation can be that the study is self-reported, thus a new

study is being conducted which includes classroom observation. In spite of the

limitations found, this study was successful in identifying the pre-service

teachers’ beliefs, which is a first step in the process of learning to

teach as Wideen et al. (1998) declare. Moreover, the research was able to track

these beliefs and to recognize how they influence the teaching practice views.

* This article

contains the final results of the project which was sponsored by the Foreign

Language Department at Universidad de Sonora, Mexico (Number of registration:

LE36).

References

Abraham,

R. G., & Vann, R. J. (1987). Strategies of two

language learners: A case study. In A. Wenden, & J. Rubin

(Eds.), Learner strategies in language learning (pp. 85102).

London, UK: Prentice Hall.

Bailey, K., Curtis, A., & Nunan, D. (2001). Pursuing professional

development: The self as source. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Borg, S. (2006). Teacher

cognition and language education. London, UK: Continuum.

Collier, V. (1995). Promoting academic success for ESL students.

Understanding second language acquisition for school. New

Jersey, NJ: Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages-Bilingual

Educators.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research

(2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE

Publications, Inc.

Cumming, A. (2004). Broadening, deepening, and

consolidating. Language Assessment Quarterly, 1(1), 5-18.

Deng, Z. (2004). Beyond teacher training: Singaporean

teacher preparation in the era of new educational initiatives. Teaching Education, 15(2), 159-173.

Ellis, R., & Barkhuizen, G. (2005). Analysing learner language.

Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ferreira, A. M. (2006). Researching

beliefs about SLA: A critical review. In P. Kalaja,

& A. M. Ferreira (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New research approaches

(pp. 7-33). New York, NY: Springer Science Business Media.

Horwitz, E. (1988). The beliefs about language

learning of beginning university Foreign language

students. The Modern Language Journal, 72(3), 283-294.

Johnson, K. E. (1999). Understanding language

teaching: Reasoning in action. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Lazaraton, A. (2000). Current trends

in research methodology and statistics in applied linguistics. TESOL

Quarterly, 34(1), 175-181.

Pajares, F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy

construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), 307-332.

Richards, J. C., Gallo, P. B., & Renandya, W. A.

(2001). Exploring teachers’ beliefs

and the processes of change. PAC Journal, 1(1), 41-58.

Ruiz-Esparza, E. (2009). The role

of beliefs about assessment in a Bachelor in English Language Teaching program

in Mexico. Doctoral Dissertation, Macquarie

University at Sydney, Australia.

Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature

pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 52-59.

Turner-Bisset, R. (2001). Expert teaching:

Knowledge and pedagogy to lead the profession. London, UK: David Fulton

Publishers.

Wideen, M., Mayer-Smith, J., & Moon, B. (1998). A critical analysis of the research on learning to

teach: Making the case for an ecological perspective on inquiry. Review of

Educational Research, 68(2), 130-178.

Williams, M. (1999). Learning teaching: A social constructivist approach – theory and

practice or theory with practice. In H. Trappes-Lomax & I. McGrath (Eds.), Theory

in language teacher education (pp. 11-20). London, UK: Longman.

About the Authors

Sofía D.

Cota Grijalva holds a BA in British

Literature, specialization in Translation from the Universidad Nacional

Autónoma de México (UNAM), and a Master in Teacher Training in

English Language Teaching from the University of

Exeter, England. Full time Professor at the University of

Sonora, Mexico. Her research areas are teacher training and teacher education.

Elizabeth

Ruiz-Esparza Barajas holds a Doctorate

of Applied Linguistics from Macquarie University at Sydney and an M.A. in

Education from the University of London. She is a professor and researcher at

the University of Sonora in Mexico. She has held different administrative

positions. Her research interests are teacher education and assessment.

Appendix A: Language Learning and Teaching

Questionnaire

Name ___________________________________ Semester _______ Date ________

Are you currently working as a teacher? ________ If yes, which level(s) ________________ Have you had any prior teaching experience? ______________ For how long? ______________ Levels taught ___________________

Read the following statements about language learning. For each statement indicate if you agree or disagree with the statement. 1=strongly agree; 2=agree; 3=neutral; 4=disagree; 5=strongly disagree

Appendix B: Interview Questions

- How is English learned?

- How should English be taught?

- How did you learn English?

- How were you taught?

- Has your perspective about how English is learned changed? How? Why?

- Has your perspective about how English is taught changed? How? Why?

References

Abraham, R. G., & Vann, R. J. (1987). Strategies of two language learners: A case study. In A. Wenden, & J. Rubin (Eds.), Learner strategies in language learning (pp. 85102). London, UK: Prentice Hall.

Bailey, K., Curtis, A., & Nunan, D. (2001). Pursuing professional development: The self as source. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Borg, S. (2006). Teacher cognition and language education. London, UK: Continuum.

Collier, V. (1995). Promoting academic success for ESL students. Understanding second language acquisition for school. New Jersey, NJ: Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages-Bilingual Educators.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Cumming, A. (2004). Broadening, deepening, and consolidating. Language Assessment Quarterly, 1(1), 5-18.

Deng, Z. (2004). Beyond teacher training: Singaporean teacher preparation in the era of new educational initiatives. Teaching Education, 15(2), 159-173.

Ellis, R., & Barkhuizen, G. (2005). Analysing learner language. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ferreira, A. M. (2006). Researching beliefs about SLA: A critical review. In P. Kalaja, & A. M. Ferreira (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New research approaches (pp. 7-33). New York, NY: Springer Science Business Media.

Horwitz, E. (1988). The beliefs about language learning of beginning university Foreign language students. The Modern Language Journal, 72(3), 283-294.

Johnson, K. E. (1999). Understanding language teaching: Reasoning in action. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Lazaraton, A. (2000). Current trends in research methodology and statistics in applied linguistics. TESOL Quarterly, 34(1), 175-181.

Pajares, F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), 307-332.

Richards, J. C., Gallo, P. B., & Renandya, W. A. (2001). Exploring teachers’ beliefs and the processes of change. PAC Journal, 1(1), 41-58.

Ruiz-Esparza, E. (2009). The role of beliefs about assessment in a Bachelor in English Language Teaching program in Mexico. Doctoral Dissertation, Macquarie University at Sydney, Australia.

Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 52-59.

Turner-Bisset, R. (2001). Expert teaching: Knowledge and pedagogy to lead the profession. London, UK: David Fulton Publishers.

Wideen, M., Mayer-Smith, J., & Moon, B. (1998). A critical analysis of the research on learning to teach: Making the case for an ecological perspective on inquiry. Review of Educational Research, 68(2), 130-178.

Williams, M. (1999). Learning teaching: A social constructivist approach – theory and practice or theory with practice. In H. Trappes-Lomax & I. McGrath (Eds.), Theory in language teacher education (pp. 11-20). London, UK: Longman.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2013 Sofía D. Cota Grijalva, Elizabeth Ruiz-Esparza Barajas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.